Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Liver's Unique Role in Immune Regulation and the Critical Function of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells (LSECs)

2. Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells: Structure and Function

2.1. Anatomy and Physiology of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells (LSECs)

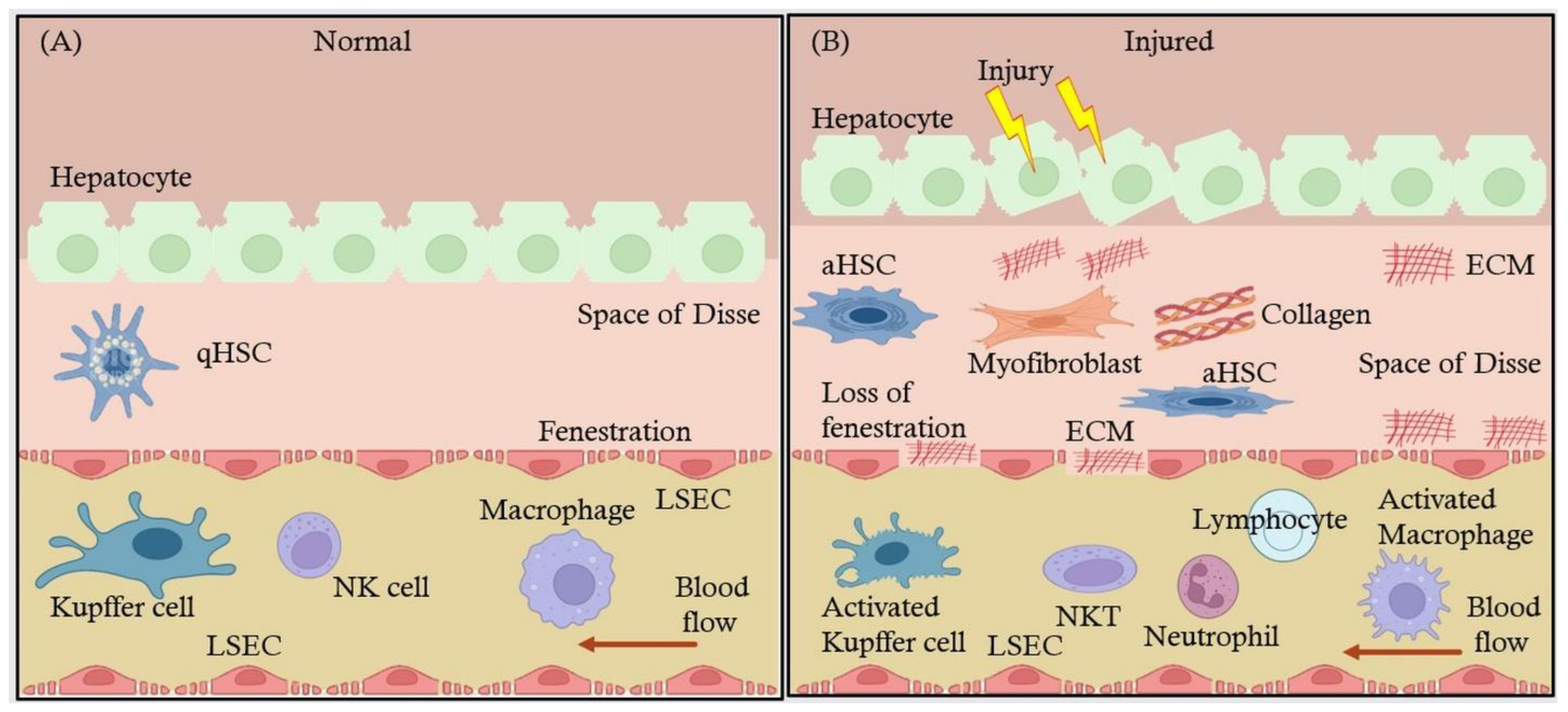

2.2. Interaction of LSECs with Other Hepatic Cells: Kupffer Cells, Hepatic Stellate Cells (HSCs), and Hepatocytes

3. LSECs in Immune Regulation

3.1. Antigen Presentation and Immune Tolerance

3.2. LSECs and Immune Cell Communication

3.2.1. Interaction with T Cells

3.2.2. Interaction with Macrophages and Kupffer Cells

3.3. LSECs in Inflammatory Liver Diseases

3.3.1. Critical Role of LSECs in MASH

3.3.2. Liver Fibrosis and Cirrhosis

4. LSECs in Liver Fibrosis

4.1. LSECs' Influence on Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Collagen Deposition Leading to Fibrosis

4.2. Signaling Pathways Involved in LSEC-Mediated Fibrosis and Endothelial Dysfunction

4.3. Changes in LSEC Phenotype Exacerbate Fibrosis and Liver Scarring

5. LSECs in Liver Disease Progression

5.1. LSECs' Contribution to the Progression of Chronic Liver Diseases (NAFLD, ALD, and Viral Hepatitis)

5.2. Interplay Between LSECs and Other Liver Cells During Liver Disease Progression

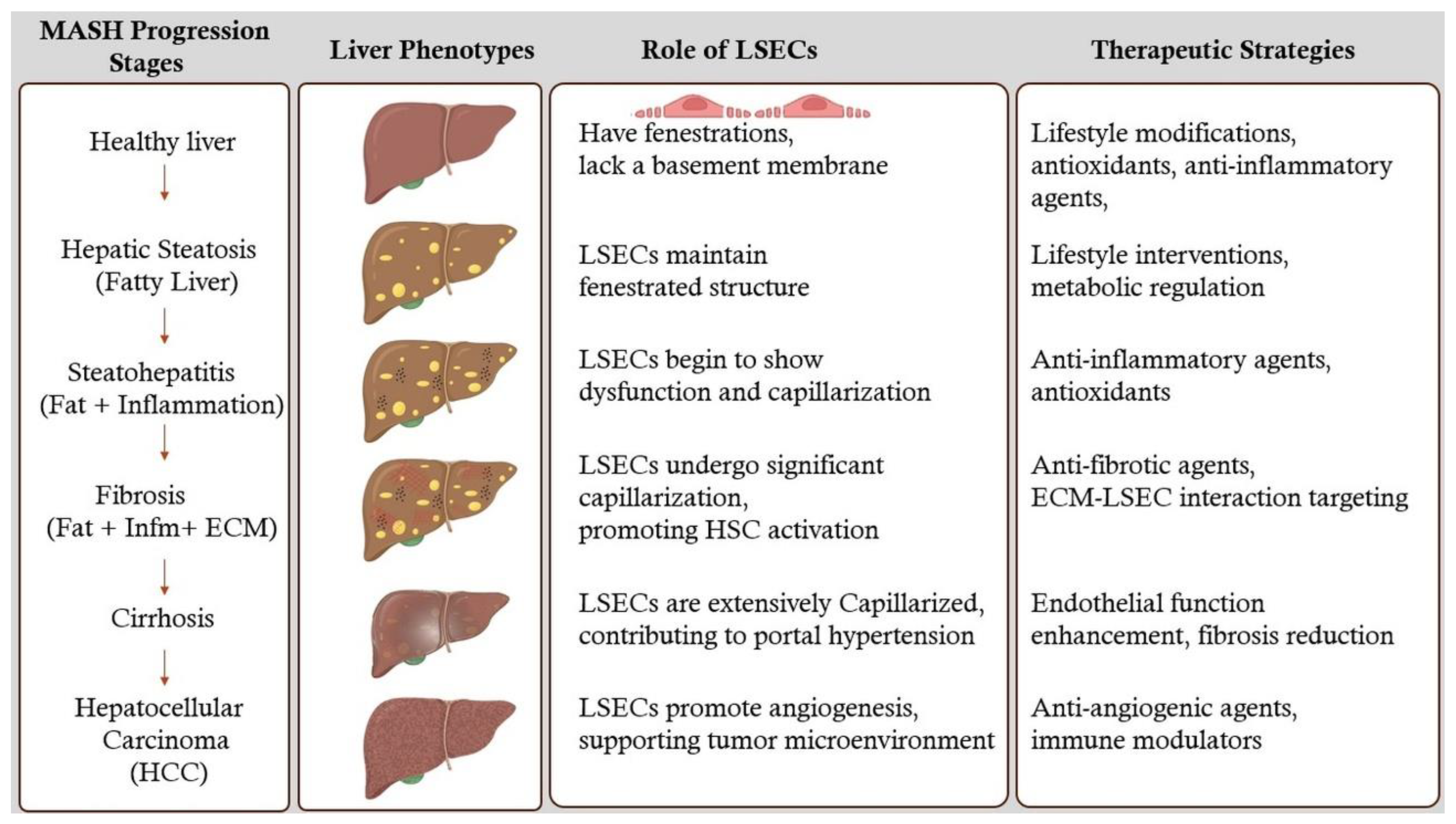

6. Stages of MASH Liver and Therapeutic Strategies

6.1. Hepatic Steatosis (Fatty Liver)

6.2. Hepatic Fibrosis

6.3. Cirrhosis

6.4. Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

7. LSECs as Therapeutic Target

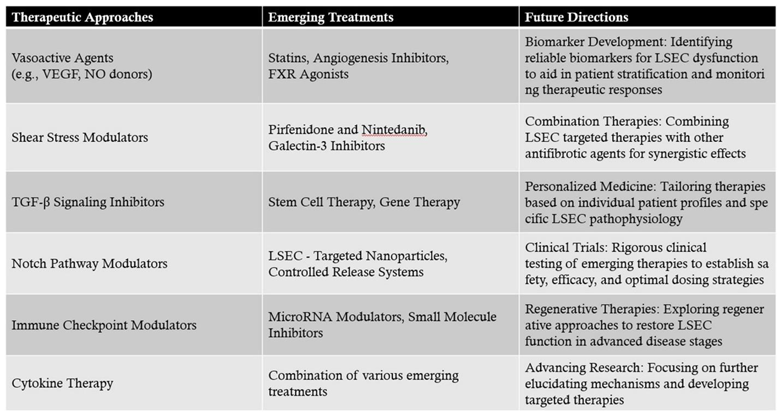

7.1. Therapeutic approaches targeting LSECs to prevent or reverse liver fibrosis and modulate immune responses.

7.1.1. Potential Therapeutic Approaches Targeting LSECs

- Vasoactive Agents: Agents such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and nitric oxide (NO) donors can promote the maintenance of LSEC fenestrations and prevent capillarization. Enhancing VEGF signaling has been shown to sustain LSEC differentiation and function[16].

- Shear Stress Modulators: LSECs respond to shear stress induced by blood flow. Modulating shear stress through mechanical or pharmacological means can influence LSEC phenotype and prevent fibrosis progression[49].

- TGF-β Signaling Inhibitors: Transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) is a key cytokine involved in HSC activation. Inhibiting TGF-β signaling in LSECs can reduce their pro-fibrotic influence on HSCs[50].

- Notch Pathway Modulators: The Notch signaling pathway in LSECs influences vascular remodeling and fibrogenesis. Modulating Notch signaling may attenuate fibrotic responses[51].

- Immune Checkpoint Modulators: Targeting immune checkpoints such as PD-L1 on LSECs can regulate T cell responses, reducing chronic inflammation and fibrogenesis[52].

- Cytokine Therapy: Administering anti-inflammatory cytokines or inhibitors of pro-inflammatory cytokines can rebalance the immune milieu toward fibrosis resolution[53].

7.1.2. Current and Emerging Treatments Targeting LSECs

- Statins: Beyond their lipid-lowering effects, statins have been shown to improve endothelial function. In LSECs, statins can enhance nitric oxide production, maintain fenestrations, and inhibit HSC activation. Clinical studies have suggested that statin therapy may slow fibrosis progression in chronic liver diseases[54].

- Angiogenesis Inhibitors: While angiogenesis is often associated with pathological conditions, controlled inhibition can prevent aberrant vascular remodeling in fibrosis. Agents targeting VEGF receptors may help maintain LSEC structure and function[31].

- FXR Agonists: Farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonists, such as obeticholic acid, have hepatoprotective and anti-fibrotic effects. They modulate bile acid metabolism and exhibit anti-inflammatory properties that indirectly benefit LSEC function[55].

- Pirfenidone and Nintedanib: Approved for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, these agents have shown potential in liver fibrosis by inhibiting fibrogenic pathways, including those mediated by LSECs[56].

- Galectin-3 Inhibitors: Galectin-3 is involved in fibrogenesis and inflammation. Inhibiting galectin-3 can reduce HSC activation and ECM production, with beneficial effects on LSEC function[57].

- Stem Cell Therapy: Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) can differentiate into functional LSECs, promoting vascular repair and reducing fibrosis[58].

- Gene Therapy: Delivery of genes encoding protective factors such as VEGF or anti-fibrotic proteins to LSECs can enhance their regenerative capacity and inhibit fibrogenic signaling[32].

- LSEC-Targeted Nanoparticles: Utilizing ligands that bind to receptors uniquely expressed on LSECs, such as mannose receptors, allows for precise delivery of antifibrotic drugs or siRNA molecules to these cells[59].

- Controlled Release Systems: Nanotechnology-enabled systems can provide sustained release of therapeutic agents, ensuring prolonged LSEC modulation and fibrosis inhibition.

- MicroRNA Modulators: MicroRNAs (miRNAs) regulate gene expression in LSECs. Therapeutics that mimic or inhibit specific miRNAs can alter LSEC behavior to favor antifibrotic outcomes[60].

- Small Molecule Inhibitors: Identifying small molecules that inhibit pro-fibrotic enzymes or signaling molecules in LSECs can provide targeted antifibrotic effects[61].

7.1.3. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

- Biomarker Development: Identifying reliable biomarkers for LSEC dysfunction can aid in patient stratification and monitoring therapeutic responses[63].

- Combination Therapies: Combining LSEC-targeted therapies with other antifibrotic agents may produce synergistic effects, enhancing overall treatment efficacy[64].

- Personalized Medicine: Tailoring therapies based on individual patient profiles and specific LSEC pathophysiology could optimize treatment outcomes.

- Clinical Trials: Rigorous clinical testing of emerging therapies is essential to establish safety, efficacy, and optimal dosing strategies for patients with liver fibrosis[65].

8. Current Challenges and Future Directions:

8.1. Gaps in the Current Understanding of LSECs in Liver Disease.

8.2. Future Research Directions: Role of LSECs in Liver Regeneration and Transplantation

9. Discussion

9.1. LSEC Dysfunction in Liver Disease

9.2. Unifying Hypothesis of LSEC-Mediated Pathology in MASH

9.3. Emerging Research Areas

10. Limitations and Challenges

10.1. Challenges in Studying LSECs

10.2. Translational Challenges

11. Future Directions

11.1. Advancing Biomarker Development

11.2. Regenerative Therapies

12. Conclusions:

|

References

- Shetty, S.; Lalor, P.F.; Adams, D.H. Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells — Gatekeepers of Hepatic Immunity. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knolle, P.A.; Wohlleber, D. Immunological Functions of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymann, F.; Tacke, F. Immunology in the Liver--from Homeostasis to Disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 13, 88–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estes, C.; Razavi, H.; Loomba, R.; Younossi, Z.; Sanyal, A.J. Modeling the Epidemic of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Demonstrates an Exponential Increase in Burden of Disease. Hepatol. Baltim. Md 2018, 67, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskridge, W.; Cryer, D.R.; Schattenberg, J.M.; Gastaldelli, A.; Malhi, H.; Allen, A.M.; Noureddin, M.; Sanyal, A.J. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatohepatitis: The Patient and Physician Perspective. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, S.; Larsen, A.K.; McCourt, P.; Smedsrød, B.; Sørensen, K.K. The Scavenger Function of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells in Health and Disease. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koyama, Y.; Brenner, D.A. Liver Inflammation and Fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2017, 127, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cogliati, B.; Yashaswini, C.N.; Wang, S.; Sia, D.; Friedman, S.L. Friend or Foe? The Elusive Role of Hepatic Stellate Cells in Liver Cancer. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 20, 647–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyao, M.; Kotani, H.; Ishida, T.; Kawai, C.; Manabe, S.; Abiru, H.; Tamaki, K. Pivotal Role of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells in NAFLD/NASH Progression. Lab. Invest. 2015, 95, 1130–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeLeve, L.D. Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells and Liver Regeneration. J. Clin. Invest. 2013, 123, 1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campana, L.; Esser, H.; Huch, M.; Forbes, S. Liver Regeneration and Inflammation: From Fundamental Science to Clinical Applications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 608–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.-K.; Peng, Z.-G. Targeting Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells: An Attractive Therapeutic Strategy to Control Inflammation in Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 655557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poisson, J.; Lemoinne, S.; Boulanger, C.; Durand, F.; Moreau, R.; Valla, D.; Rautou, P.-E. Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells: Physiology and Role in Liver Diseases. J. Hepatol. 2017, 66, 212–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Wang, L. The Crosstalk Between Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells and Hepatic Microenvironment in NASH Related Liver Fibrosis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuta, K.; Guo, Q.; Hirsova, P.; Ibrahim, S.H. Emerging Roles of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells in Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Biology 2020, 9, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, M.J.; Kostallari, E.; Ibrahim, S.H.; Iwakiri, Y. The Evolving Role of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells in Liver Health and Disease. Hepatol. Baltim. Md 2023, 78, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrfeld, C.; Zenner, S.; Kornek, M.; Lukacs-Kornek, V. The Contribution of Non-Professional Antigen-Presenting Cells to Immunity and Tolerance in the Liver. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, A.L.; Qurashi, M.; Shetty, S. The Role of Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells in the Axis of Inflammation and Cancer Within the Liver. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacke, F.; Zimmermann, H.W. Macrophage Heterogeneity in Liver Injury and Fibrosis. J. Hepatol. 2014, 60, 1090–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parthasarathy, G.; Malhi, H. Macrophage Heterogeneity in NASH: More Than Just Nomenclature. Hepatol. Baltim. Md 2021, 74, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLeve, L.D. Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells in Hepatic Fibrosis. Hepatol. Baltim. Md 2015, 61, 1740–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H. Intercellular Crosstalk of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells in Liver Fibrosis, Cirrhosis and Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Dig. Liver Dis. 2022, 54, 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafranska, K.; Kruse, L.D.; Holte, C.F.; McCourt, P.; Zapotoczny, B. The wHole Story About Fenestrations in LSEC. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 735573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; He, W.; Dong, H.; Guo, Y.; Yuan, G.; Shi, X.; Wang, D.; Lu, F. Role of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cell in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Cell Commun. Signal. 2024, 22, 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasa, E.; Hartmann, P.; Schnabl, B. Liver Cirrhosis and Immune Dysfunction. Int. Immunol. 2022, 34, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horst, A.K.; Neumann, K.; Diehl, L.; Tiegs, G. Modulation of Liver Tolerance by Conventional and Nonconventional Antigen-Presenting Cells and Regulatory Immune Cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 277–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limmer, A.; Ohl, J.; Kurts, C.; Ljunggren, H.-G.; Reiss, Y.; Groettrup, M.; Momburg, F.; Arnold, B.; Knolle, P.A. Efficient Presentation of Exogenous Antigen by Liver Endothelial Cells to CD8+ T Cells Results in Antigen-Specific T-Cell Tolerance. Nat. Med. 2000, 6, 1348–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenne, C.N.; Kubes, P. Immune Surveillance by the Liver. Nat. Immunol. 2013, 14, 996–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, E.; Schwabe, R.F. Hepatic Inflammation and Fibrosis: Functional Links and Key Pathways. Hepatol. Baltim. Md 2015, 61, 1066–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, M. Spatial Computational Hepatic Molecular Biomarker Reveals LSEC Role in Midlobular Liver Zonation Fibrosis in DILI and NASH Liver Injury. Int. J. Transl. Med. 2024, 4, 208–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Li, J.-M.; Liu, M.-K.; Zhang, T.-T.; Wang, D.-P.; Zhou, W.-H.; Hu, L.-Z.; Lv, W.-L. Pathological Process of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells in Liver Diseases. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 7666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Li, X. Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cell: An Important yet Often Overlooked Player in the Liver Fibrosis. Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2024, 30, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Zuo, B.; He, Y. Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells as Potential Drivers of Liver Fibrosis (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 2024, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsuda, M.; Seki, E. The Liver Fibrosis Niche: Novel Insights into the Interplay between Fibrosis-Composing Mesenchymal Cells, Immune Cells, Endothelial Cells, and Extracellular Matrix. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2020, 143, 111556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, B.; Duan, J.-L.; Xu, H.; Tao, K.-S.; Han, H.; Dou, G.-R.; Wang, L. Capillarized Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells Undergo Partial Endothelial-Mesenchymal Transition to Actively Deposit Sinusoidal ECM in Liver Fibrosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 671081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkız, H.; Gieseler, R.K.; Canbay, A. Liver Fibrosis: From Basic Science towards Clinical Progress, Focusing on the Central Role of Hepatic Stellate Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elpek, G.Ö. Angiogenesis and Liver Fibrosis. World J. Hepatol. 2015, 7, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allameh, A.; Niayesh-Mehr, R.; Aliarab, A.; Sebastiani, G.; Pantopoulos, K. Oxidative Stress in Liver Pathophysiology and Disease. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, Q.; Yi, Q.; Tang, L. Liver Fibrosis Resolution: From Molecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 9671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLeve, L.D.; Maretti-Mira, A.C. Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cell: An Update. Semin. Liver Dis. 2017, 37, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Li, X.; Slevin, E.; Harrison, K.; Li, T.; Zhang, Y.; Klaunig, J.E.; Wu, C.; Shetty, A.K.; Dong, X.C.; et al. Endothelial Dysfunction in Pathological Processes of Chronic Liver Disease during Aging. FASEB J. 2022, 36, e22125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.-Y.; Yuan, W.-G.; He, P.; Lei, J.-H.; Wang, C.-X. Liver Fibrosis and Hepatic Stellate Cells: Etiology, Pathological Hallmarks and Therapeutic Targets. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 10512–10522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Huang, S.; Jiang, H.; Ma, Q.; Qiu, J.; Luo, Q.; Cao, C.; Xu, Y.; Chen, F.; Chen, Y.; et al. Alcohol-Related Liver Disease (ALD): Current Perspectives on Pathogenesis, Therapeutic Strategies, and Animal Models. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1432480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robinson, M.W.; Harmon, C.; O’Farrelly, C. Liver Immunology and Its Role in Inflammation and Homeostasis. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2016, 13, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-García, C.; Fernández-Iglesias, A.; Gracia-Sancho, J.; Arráez-Aybar, L.A.; Nevzorova, Y.A.; Cubero, F.J. The Space of Disse: The Liver Hub in Health and Disease. Livers 2021, 1, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakiri, Y. Unlocking the Role of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells: Key Players in Liver Fibrosis: Editorial on “Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cell: An Important yet Often Overlooked Player in the Liver Fibrosis. ” Clin. Mol. Hepatol. 2024, 30, 673–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czyzynska-Cichon, I.; Kotlinowski, J.; Blacharczyk, O.; Giergiel, M.; Szymanowski, K.; Metwally, S.; Wojnar-Lason, K.; Dobosz, E.; Koziel, J.; Lekka, M.; et al. Early and Late Phases of Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cell (LSEC) Defenestration in Mouse Model of Systemic Inflammation. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2024, 29, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagy, D.; Maude, H.; Birdsey, G.M.; Randi, A.M.; Cebola, I. RISING STARS: Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Transcription Factors in Metabolic Homeostasis and Disease. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 2023, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soydemir, S.; Comella, O.; Abdelmottaleb, D.; Pritchett, J. Does Mechanocrine Signaling by Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells Offer New Opportunities for the Development of Anti-Fibrotics? Front. Med. 2020, 6, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewidar, B.; Meyer, C.; Dooley, S.; Meindl-Beinker, N. TGF-β in Hepatic Stellate Cell Activation and Liver Fibrogenesis—Updated 2019. Cells 2019, 8, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisler, F.; Strazzabosco, M. Emerging Roles of Notch Signaling in Liver Disease. Hepatol. Baltim. Md 2015, 61, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lurje, I.; Hammerich, L.; Tacke, F. Dendritic Cell and T Cell Crosstalk in Liver Fibrogenesis and Hepatocarcinogenesis: Implications for Prevention and Therapy of Liver Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bignold, R.; Johnson, J.R. Effects of Cytokine Signaling Inhibition on Inflammation-Driven Tissue Remodeling. Curr. Res. Pharmacol. Drug Discov. 2021, 2, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bravo, M.; Raurell, I.; Hide, D.; Fernández-Iglesias, A.; Gil, M.; Barberá, A.; Salcedo, M.T.; Augustin, S.; Genescà, J.; Martell, M. Restoration of Liver Sinusoidal Cell Phenotypes by Statins Improves Portal Hypertension and Histology in Rats with NASH. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 20183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Li, X.; Fan, G.; Liu, R. Targeting Bile Acid Signaling for the Treatment of Liver Diseases: From Bench to Bed. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 152, 113154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Bayliss, G.; Zhuang, S. Application of Nintedanib and Other Potential Anti-Fibrotic Agents in Fibrotic Diseases. Clin. Sci. Lond. Engl. 1979 2019, 133, 1309–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, N.C.; Mackinnon, A.C.; Farnworth, S.L.; Poirier, F.; Russo, F.P.; Iredale, J.P.; Haslett, C.; Simpson, K.J.; Sethi, T. Galectin-3 Regulates Myofibroblast Activation and Hepatic Fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 5060–5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Mao, Y.; Xie, Y.; Wei, J.; Yao, J. Stem Cells for Treatment of Liver Fibrosis/Cirrhosis: Clinical Progress and Therapeutic Potential. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2022, 13, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carambia, A.; Gottwick, C.; Schwinge, D.; Stein, S.; Digigow, R.; Şeleci, M.; Mungalpara, D.; Heine, M.; Schuran, F.A.; Corban, C.; et al. Nanoparticle-Mediated Targeting of Autoantigen Peptide to Cross-Presenting Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells Protects from CD8 T-Cell-Driven Autoimmune Cholangitis. Immunology 2021, 162, 452–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouve, M.; Carpentier, R.; Kraiem, S.; Legrand, N.; Sobolewski, C. MiRNAs in Alcohol-Related Liver Diseases and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Step toward New Therapeutic Approaches? Cancers 2023, 15, 5557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jangra, A.; Kothari, A.; Sarma, P.; Medhi, B.; Omar, B.J.; Kaushal, K. Recent Advancements in Antifibrotic Therapies for Regression of Liver Fibrosis. Cells 2022, 11, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.-P.; Ge, J.-Y.; Song, Y.-M.; Yu, X.-Q.; Chen, W.-H.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Ye, D.; Zheng, Y.-W. A Novel Efficient Strategy to Generate Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortega-Ribera, M.; Gibert-Ramos, A.; Abad-Jordà, L.; Magaz, M.; Téllez, L.; Paule, L.; Castillo, E.; Pastó, R.; de Souza Basso, B.; Olivas, P.; et al. Increased Sinusoidal Pressure Impairs Liver Endothelial Mechanosensing, Uncovering Novel Biomarkers of Portal Hypertension. JHEP Rep. 2023, 5, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Wang, L.; Wang, M.; Zhou, S.; Lu, Y.; Cui, H.; Racanelli, A.C.; Zhang, L.; Ye, T.; Ding, B.; et al. Targeting Fibrosis: Mechanisms and Clinical Trials. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trautwein, C.; Friedman, S.L.; Schuppan, D.; Pinzani, M. Hepatic Fibrosis: Concept to Treatment. J. Hepatol. 2015, 62, S15–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puri, M. Automated Machine Learning Diagnostic Support System as a Computational Biomarker for Detecting Drug-Induced Liver Injury Patterns in Whole Slide Liver Pathology Images. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2020, 18, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwokoye, P.N.; Abilez, O.J. Bioengineering Methods for Vascularizing Organoids. Cell Rep. Methods 2024, 4, 100779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gayathiri, E.; Prakash, P.; Kumaravel, P.; Jayaprakash, J.; Ragunathan, M.G.; Sankar, S.; Pandiaraj, S.; Thirumalaivasan, N.; Thiruvengadam, M.; Govindasamy, R. Computational Approaches for Modeling and Structural Design of Biological Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2023, 185, 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, S.; Kidambi, S.; Ortega-Ribera, M.; Thuy, L.T.T.; Nieto, N.; Cogger, V.C.; Xie, W.-F.; Tacke, F.; Gracia-Sancho, J. In Vitro Models for the Study of Liver Biology and Diseases: Advances and Limitations. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 15, 559–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).