1. Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common malignant tumor diagnosed worldwide, characterized by a high mortality rate despite the recent research and strategies developed for cancer treatment [

1]. According to the Lauren classification, GC has four subtypes: intestinal, diffuse, mixed, and unclassified [

2]. The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network proposed a novel molecular classification of GC: Epstein-Barr virus-positive (EBV), microsatellite instability (MSI), chromosomal instability (CIN), and genomically stable (GS) [

3].

The molecular classification of GC has provided a better understanding of the disease’s heterogeneity and its relationship with the immune system. The immune system interacts differently with different molecular subtypes of GC, affecting the tumor microenvironment (TME), prognosis, and response to treatments, including immunotherapy [

4,

5].

Since immune cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems are part of the TME, immune system reactions can potentially eliminate cancer cells or modify their characteristics and functions [

6]. But to evade immune surveillance, cancer cells have developed various strategies, including weak points in the antigen-presenting cells, the overexpression of negative regulatory pathways, and the chemoattraction of immunosuppressive cells in the TME. This has limited the ability of immune cells to perform their functions and inhibited the immune system’s capacity to fight cancer [

7].

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) form a major component of the immune response and significantly influence tumor progression and patient prognosis. TILs in the TME give evidence of an active immune response, which might be necessary to restrict tumor growth and metastasis. In patients with GC it has been demonstrated that higher densities of TILs are associated with higher survival rates, indicating a protective role of TILs against tumor progression [

8,

9].

Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) interacts with the Programmed Cell Death-Protein-1 (PD-1) receptor on the surface of T cells and reduces the activity of T cells, decreasing their ability to mount an effective attack against the tumor [

10].

Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin 15 (Siglec-15), like PD-L1, can contribute to creating an immunosuppressive TME. By interacting with its receptors on T cells, Siglec-15 can inhibit T cell activation and proliferation, reducing the immune system’s ability to target and destroy tumor cells [

11].

Siglec-15 and PD-L1 function through complementary but distinct pathways [

12]. PD-L1 inhibits T cell function by binding to PD-1; in contrast, Siglec-15 interacts with different receptors, such as sialic acid-binding receptors expressed on T cells to exert its immunosuppressive functions. Interestingly, Siglec-15 expression is often mutually exclusive with PD-L1 expression, suggesting that tumors that do not express PD-L1 may express Siglec-15 instead, thus serving as a potential alternative target for immunotherapy in PD-L1 negative patients [

13,

14].

The aim of the present review article is to provide a better understanding of the relationship between GC, TILs, and immune checkpoint molecules PD-L1 and Siglec-15. All the discussion is integrated in the GC TME, exploring how TILs influence tumor progression and patient outcomes. A particular focus was directed to Siglec-15 and PD-L1 involvement in immune evasion and their potential targeting in immunotherapy.

2. TILs

Traditionally, the population of lymphocytes that infiltrate the tumor microenvironment—especially T cells and B cells—is referred to as “tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)”. But the term “tumor-infiltrating leukocytes” or “tumor-infiltrating immune cells” refers to a wider range of immune cells than merely lymphocytes. This larger category includes various cell types involved in the tumor’s immune response, including macrophages, dendritic cells, mast cells, neutrophils, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [

15,

16].

In this review, the focus is primarily on T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, natural killer (NK) cells, and tumor associated-macrophages (TAMs) and their important roles in modifying the TME, impacting tumor growth, immunological responses, and the efficacy of immunotherapy in GC.

I. T lymphocytes

The immunological landscape of GC is influenced by distinct subsets of lymphocytes, which can lead to significant differences in TILs’ composition. In the setting of EBV-associated GC or MSI, CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) are particularly important because they can directly induce apoptosis in cancer cells, and their presence is associated with better clinical outcomes [

17,

18]. TILs additionally comprise T-helper 17 (Th17) and regulatory T cells (Tregs), the balance between which affects the TME and the immune system as a whole [

19].

T cell receptor (TCR) subunits and the key lineage markers CD8 and CD4 are used to classify T lymphocytes. The αβTCR complex gives T cells the ability to recognize peptides on their cell surface according to the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I (for CD8 T cells) or class II (for CD4 T cells). The γδ TCR component, on the other hand, is believed to function mainly independently of MHC classes I and II [

20,

21].

1. CD8+ T cells

CD8+ T or CTLs are known for their exceptional antiviral and anticancer properties. The capacity of CD8+ T cells to destroy tumor cells makes them a very important component of TILs. Evidence has demonstrated that an increased density of CD8+ TILs is associated with a better prognosis in several types of malignancies [

22].

High concentrations of cytotoxic molecules and antitumor cytokines, including interferon-γ (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), perforin, and granzymes, can be produced by CTLs [

23].

After their primary targets are eliminated, CTLs generate a variety of memory subsets that offer long-term protection against reinfection: stem cell-like memory T cells, central memory T cells, effector memory T cells, effector memory Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)+ T cells and peripheral tissue-resident memory cells (TRM) [

24]. The most notable naive cells are stem cell-like memory T. They are primarily present in lymph nodes, followed by spleen and bone marrow. Stem cell-like memory T cells assure their self-renewal and can divide quickly and generate inflammatory cytokines. Although central memory T cells have naive-like characteristics, they show a reduced ability to self-renew. Effector memory RA+ T cells preferentially travel to peripheral tissues and exhibit proinflammatory effector functions following secondary antigen contact with a cognate antigen [

25,

26].

TRM function in tumor immunity has gained more attention lately. These cells express CD39 and CD103, the latter forming αEβ7 complex with integrin β7, which interacts with E-cadherin. Tumor control was found to be affected by the absence of CD103+ CTLs or E-cadherin in cancer animal models [

27,

28].

In numerous solid tumors, bystander TRM cells have also been found. These cells don’t present selectivity for tumor antigens, and they are different from the group of tumor-specific TRM because they exhibit a variety of phenotypes but do not express CD39. These cells are either predominantly reactive to common human pathogens such as EBV, cytomegalovirus, and influenza or demonstrate ambiguous antigen specificity [

29].

During research of CD8+ T lymphocytes in malignancies, there are two main consequences of tumor infiltration of the bystander TRM cells. Firstly, the presence of bystanders may create confusions regarding the link between CD8+ T cell infiltration and response to immune checkpoint inhibitors since tumor-specific CD8+ T cells are mandatory for effective tumor destruction. The ranging percentage of bystander TRM compared to tumor-specific cells CD8+ T cells across different tumors and individuals may explain this event. An additional possible aspect is the antigen-independent function exerted by bystander cells in the maintenance of the favorable local immunological microenvironment by secreting several cytokines and chemokines. Such infiltration has the potential to greatly complicate investigations examining the number, phenotype, and differentiation of tumor-specific CD8+ lymphocytes unless their antigen specificity is determined [

30,

31,

32,

33].

Tumor specificity of T cells cannot be determined by observing their presence in the TME alone. It is, therefore, important to distinguish between the phenotype and quantity of tumor-specific cells and the quantity and phenotype of tumor-infiltrating cells. The significant variation in antigen specificities within the tumor begs the crucial question of how much of the phenotypic variability of CD8+ TILs that has been observed can be ascribed to different antigen specificities and, thus, to various types of antigenic stimulation versus tumor-specific cell differentiation. [

30,

31,

34]

1. CD4+ T cells

Based on their patterns of cytokine production and functions, Th17 and forkhead box protein P3 (FOXP3+) Tregs cells have been recently identified as two different CD4+ T subsets from Th1 and Th2 cells, with significant roles in GC [

35].

FOXP3+ Treg cells are functionally immunosuppressive and are identified by the expression of FOXP3+ in the nucleus. They have important roles in maintaining tolerance to self-components by releasing anti-inflammatory cytokines like transforming Growth Factor-Beta (TGF-β) and interleukin-10 (IL-10), or using contact-dependent suppression [

36,

37]. Numerous immune cels, including monocytes, macrophages, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells are inhibited by FOXP3+Tregs. The large accumulation of these cells impairs the effector T cells’ ability to create an effective defense [

36,

37,

38]. Also, they can use the metabolites produced by the tumor cells as an energy source, preferring the fatty acid energy supply pathway [

39]. Consequently, the cancer cells multiply in an immune-suppressive environment where FOXP3+Tregs are increased in number, while effector T cells and dendritic cells (DCs) activities become ineffective [

40].

Patients with Helicobacter (H.)

pylori infection express FOXP3+ Tregs at much higher levels than negative patients. Moreover, it has been discovered that H.

pylori can modify the stomach microbiota upregulating FOXP3+ Tregs, TGF-β, and IL-10 expression [

41]. Additional findings showed that GC patients infected with H.

pylori had higher levels of FOXP3+ Tregs cell infiltration in the local mucosa and

the peripheral blood mononuclear cells

(PBMCs), the ratio of Tregs/Th17 and Th1/Th2 being disturbed. As a result, FOXP3+ Tregs play a significant role in the genesis of precancerous lesions and GC [

42,

43]. Th17 cells produce interleukin interleukin-17 (IL-17) which causes stomach epithelial cells to produce interleukin-8 (IL-8), maintaining chronic inflammation. Prolonged inflammation may facilitate the gradual progression from chronic gastritis to premalignant gastric lesions [

44,

45]. Th17 cell’s increased level was linked to advanced clinical stages in GC. Furthermore, patients with GC with high IL-17 concentrations were found to have a bad prognosis [

46,

47]. Through interleukin-6 (IL-6), TGF-β, and interleukin-21 (IL-21), the TME stomach myofibroblasts stimulate Th17 differentiation which by secretion of IL-17 will promote tumor progression [

46,

47].

FOXP3+ Treg cells promote tumor progression by helping neoplastic cells escape from immunosurveillance by secreting TGF-β. At the same time, a high level of TGF-β and IL-6 in the TME stimulates the differentiation and expansion of FOXP3+ Treg cells [

36,

37,

46].

Recent research has highlighted the importance of the disturbed balance between Th17 and FOXP3+ Treg cells in GC. Patients with advanced GC have a greater Th17/FOXP3+ Treg ratio than healthy controls [

36,

48]. Additionally, patients with lymph node metastases have shown a significantly elevated Th17/FOXP3+ Treg cell ratio [

35].

I. B lymphocytes

B cells are becoming more widely recognized as essential parts of TILs. According to recent studies, B cells can constitute a substantial percentage of TILs. Through a variety of processes, such as the production of antibodies, the presentation of antigens, and the development of tertiary lymphoid structures that promote localized immune responses, B cells support the immune response to malignancies [

49,

50].

1. Regulatory B Cells (Bregs)

Bregs with inhibitory phenotypes capable of anti-inflammatory cytokines production, such as IL-10, TGF-β, and interleukin-3 (IL-3) were identified. Nevertheless, these anti-inflammatory cytokines can accelerate the progression of malignancies [

51,

52]. Bregs express inhibitory molecules such as Fas Ligand (FasL) and PDL-1 and can support tumor progression by suppressing anti-tumor immune responses. In GC IL-10 and TGF- β produced by Bregs decreases CD4+ T cell functions and promotes FOXP3+Treg expansion. Inhibiting the differentiation into Th1 and stimulating differentiation into FOXP3+CD4+ Treg and Th2, IL-10 can additionally disrupt the delicate balance between Th1 and Th2 responses [

53].

An analysis of patients with chronic gastritis revealed the number of Bregs in H.

pylori-infected patients was significantly higher than in uninfected patients. This finding suggests that Bregs may be involved in modulating the inflammatory response to H.

pylori infection. Still, when the patient enters the GC phase, these cells can favor the tumor progression [

54].

3. Tertiary Lymphoid Structures (TLSs)

TLSs are ectopic lymphoid structures that resemble secondary lymphoid organs which are formed in non-lymphoid tissues at the site of persistent inflammation. TLSs are composed of B cell aggregates within a follicular dendritic cell (FDC) meshwork. T cells and specialized blood vessels known as high endothelial venules surround the B cells. These structures are linked with increased tumor survival in GC [

55]. TLSs are thought to be formed in the normal gastric mucosa because of chronic inflammation caused by a prolonged H.

pylori infection [

56].

The latest research revealed that the GC tissue contains aggregates of B cells, T cells, and FDC. Antigen-activated B cells often reach the GC tissue where differentiate into GC B cells, which then differentiate into plasmablasts and remain active or become memory B cells within secondary lymphoid organs. TLSs are thought to function on the same basis. GC was found to contain nearly every stage of the B cells, including GC B cells, plasmablasts, and many memory B cells. Most B lymphocytes infiltrating GC are organized in TLSs, are sensitized to antigen, and have the capacity to differentiate into antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and multiply within TLSs, except the lymph nodes. Furthermore, some studies suggest that tumor-infiltrating B cells can predominantly act as APCs and enhance CTLs’ survival and tumor metastasis [

57,

58,

59].

I. NK Cells

TILs also include NK cells, which are a crucial component of the immune system. These cells are necessary for identifying and destroying tumor cells, enabling a prompt immune response because their action is not condition by a previous contact with an antigen [

60].

NK cells can identify and eliminate gastric tumor cells coated in antibodies by attaching to Fc region with their CD16 receptors. This triggers the release of cytotoxic granules containing perforin and granzymes, followed by apoptosis in the target cells [

60,

61]. Also, NK cells may induce apoptosis by releasing tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) or by binding to their death receptors [

60,

62].

The Fas/FasL system plays an important role in the apoptosis of tumor-specific lymphocytes. Recent literature revealed that GC cells have a high proportion of NK cells expressing the Fas receptor, strongly correlated with an increased apoptosis rate of NK cells. As a result, patients with GC have a significantly higher rate of NK cell apoptosis compared to controls and a higher possibility of cancer progression. The apoptosis and Fas expression rate is even higher in NK cells from the gastric tumor tissue itself compared to circulating NK cells in the peripheral blood collected from the same patients [

62,

63,

64].

Decreased NK cell activity was significantly associated with more advanced gastric tumor stages, such as larger size, vascular involvement, and lymph node metastases. Furthermore, the density of NK cells within the tumor was found to be an independent prognostic factor for overall and disease-free survival in GC. Similarly, a higher percentage of NK cells in peripheral blood correlates with longer survival and earlier cancer stages and can serve as an independent prognostic biomarker in GC [

62,

64].

NK Group 2 Member D (NKG2), an important receptor for the activation of NK cells, is significantly expressed in GC. When cancer cells express NKG2D ligands, they are more susceptible to NK cells. A study testing the susceptibility of GC cells to NK cells demonstrated that the samples with GC which expressed NKG2D ligands presented a better prognosis and decreased metastasis rate [

65].

Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), as a major enzymatic result of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) overexpression, is involved in inflammation and tumor progression. Furthermore, according to the latest literature, the levels of NK cells within the tumor were negatively correlated with the expression of COX-2. On the other hand, PGE2 produced by GC cells suppressed the proliferation and increased apoptosis of NK cells [

66].

Advanced combination therapy with adoptive NK cell therapy and immunoglobulin (Ig)G1 monoclonal antibodies was shown to induce a Th1-type immune response and decrease in peripheral Tregs, contributing to good tolerability and preliminary antitumor efficacy in GC. During the last few years, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified NK cells have been studied and demonstrated a promising immunotherapy approach for the cancer management. The ability of CAR-NK cells that are specific for CD19, CD20, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER-2) to kill target cells may be effective for HER-2+ GC [

67,

68]. Therefore, reversing NK cell dysfunction needs further investigation as a potential GC treatment.

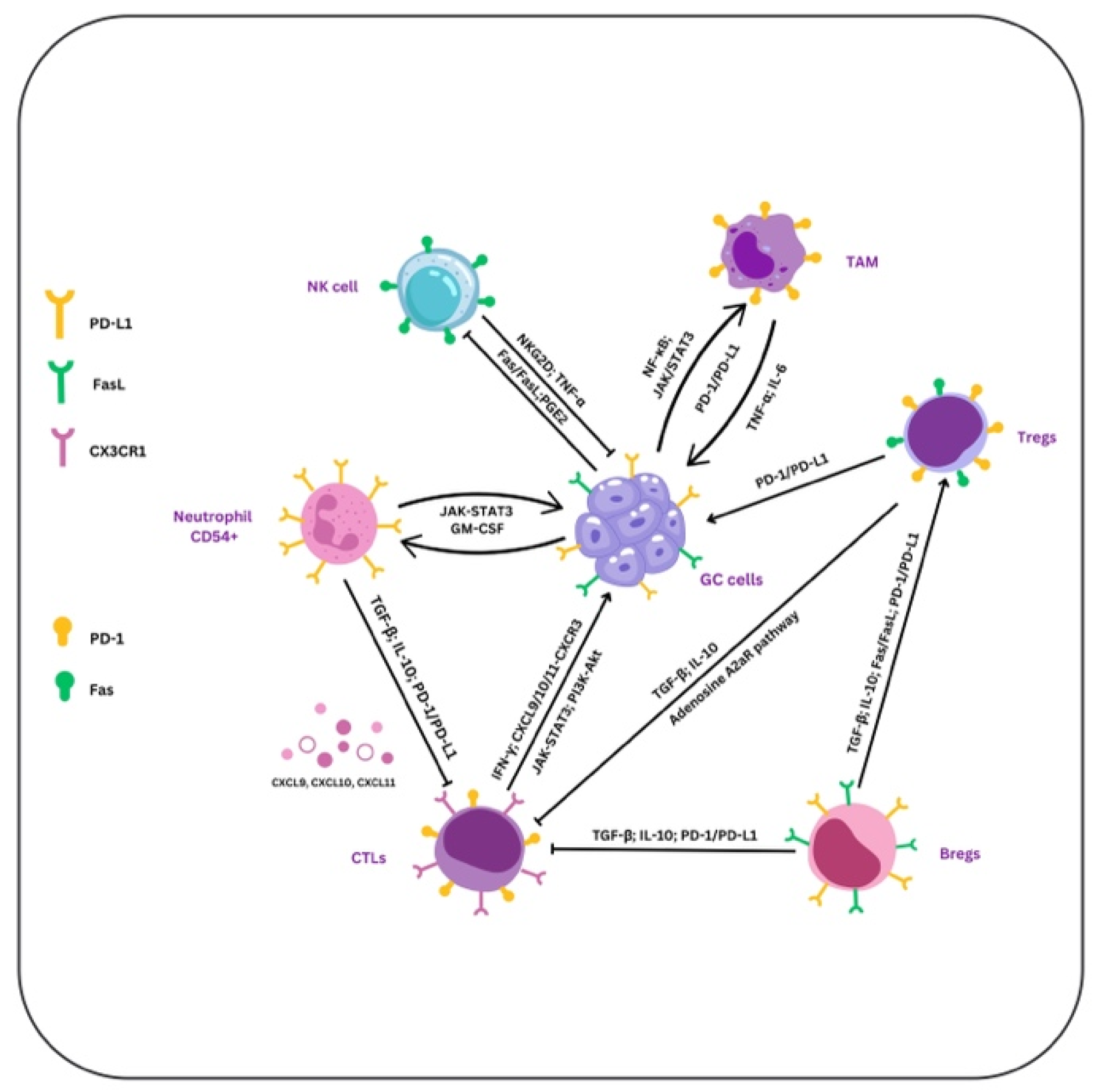

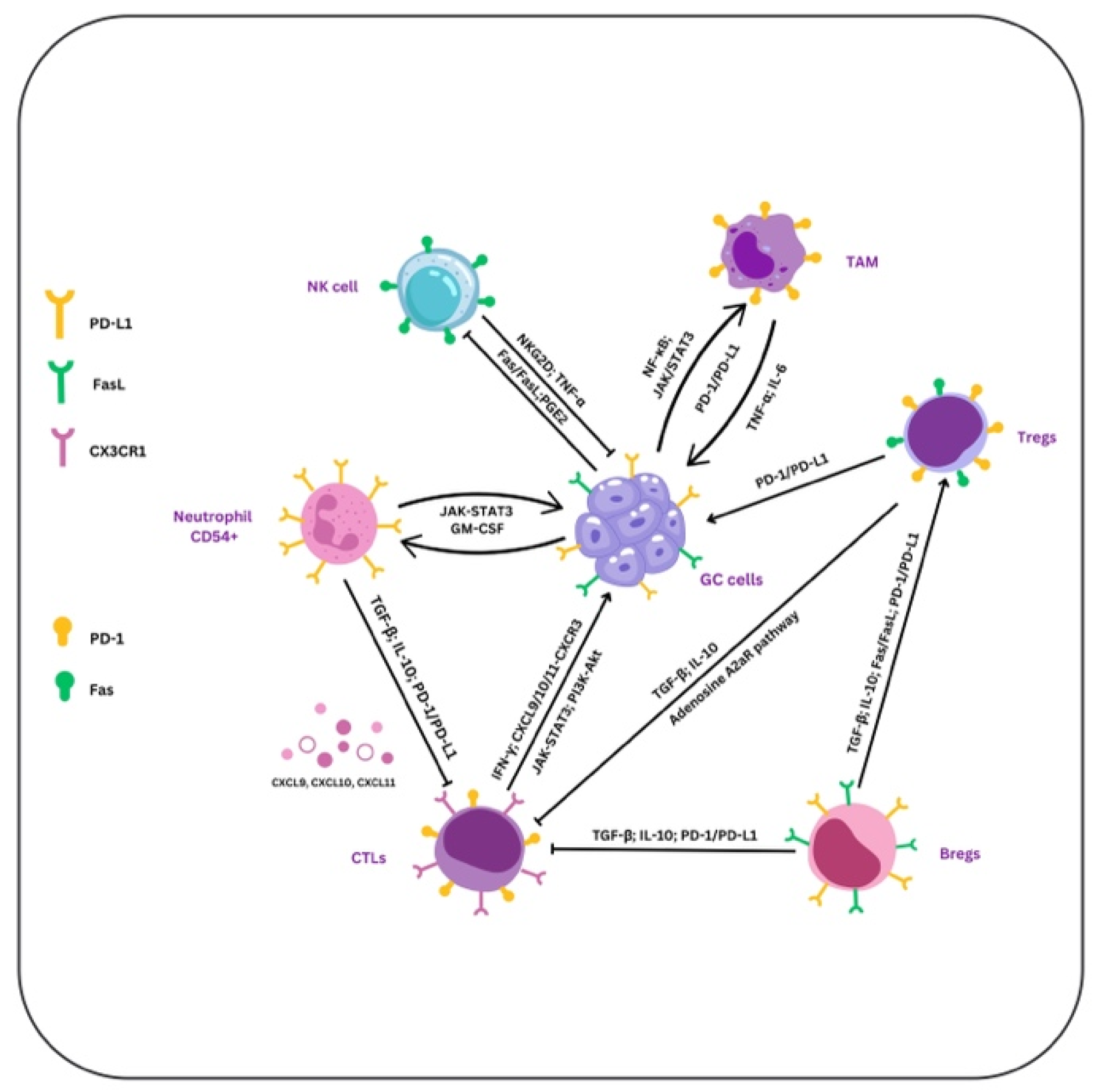

Figure 1.

Immune cell dynamics in GC. TNF-α, IL-6, and signaling pathways (NF-κB and JAK/STAT3) drive the interaction between TAMs, GC, and NK cells, enhancing PD-L1 expression and promoting tumor growth. Through PD-L1 expression and release of IL-10 and TGF-β, Tregs inhibit Bregs and CTLs. They additionally help in immunological suppression activating the A2AR and the Fas/FasL pathways, the last being involved in CTLs’ apoptosis. Using NKG2D and TNF-α release, NK cells induce GC cell apoptosis, whereas PGE2 secreted by the GC cells inhibits NK function. Also, NK cells use FasL to initiate GC cell destruction, whereas GC cells use Fas expression to stop their activity. In neutrophils, JAK/STAT3 signaling improves adhesion and activation, while through PD-1/PD-L1, TGF-β, and IL-10 they reduce CTLs’ function. Through their interaction with GC cells via IFN-γ, CTLs stimulate the synthesis of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, attracting CTLs to the tumor site via CXCR3. Using PD-1/PD-L1 interactions and the release of TGF-β and IL-10, Bregs alter CTLs’ activity.By releasing immunosuppressive substances like TGF-β and VEGF and stimulating CTLs activation, PI3K-AKT signaling amplifies tumor growth and immune suppression. The JAK-STAT3 pathway in CTLs may reduce their cytotoxic effect and promote immunological tolerance.

Figure 1.

Immune cell dynamics in GC. TNF-α, IL-6, and signaling pathways (NF-κB and JAK/STAT3) drive the interaction between TAMs, GC, and NK cells, enhancing PD-L1 expression and promoting tumor growth. Through PD-L1 expression and release of IL-10 and TGF-β, Tregs inhibit Bregs and CTLs. They additionally help in immunological suppression activating the A2AR and the Fas/FasL pathways, the last being involved in CTLs’ apoptosis. Using NKG2D and TNF-α release, NK cells induce GC cell apoptosis, whereas PGE2 secreted by the GC cells inhibits NK function. Also, NK cells use FasL to initiate GC cell destruction, whereas GC cells use Fas expression to stop their activity. In neutrophils, JAK/STAT3 signaling improves adhesion and activation, while through PD-1/PD-L1, TGF-β, and IL-10 they reduce CTLs’ function. Through their interaction with GC cells via IFN-γ, CTLs stimulate the synthesis of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, attracting CTLs to the tumor site via CXCR3. Using PD-1/PD-L1 interactions and the release of TGF-β and IL-10, Bregs alter CTLs’ activity.By releasing immunosuppressive substances like TGF-β and VEGF and stimulating CTLs activation, PI3K-AKT signaling amplifies tumor growth and immune suppression. The JAK-STAT3 pathway in CTLs may reduce their cytotoxic effect and promote immunological tolerance.

4. TAMs

In TME, monocytes in response to growth factors generated by tumors, stromal cells, and chemokines, differentiate into TAMs. In GC, these TAMs may promote genetic instability, support cancer stem cells, accelerate metastasis, and help create an immunosuppressive TME through the inhibition of T-cell activation. [

69].

Usually polarizing into either pro-inflammatory (M1) or anti-inflammatory (M2) phenotypes, TAMs are abundant in the TME. M2-polarized TAMs are predominant in GC and are linked to immunological suppression and tumor growth [

69].

TAMs can contribute to an immunosuppressive milieu in GC that can reduce the CTLs’ function. This mechanism is mediated by PD-1/PD-L1 interaction on T cells, TAMs, and tumor cells, which decreases the cytotoxic activity of CTLs and promotes the tumor growth. High PD-L1 expression in GC is associated with poor outcomes and with higher TAMs levels. This suggests that TAMs might increase the immunosuppressive environment by stimulating tumor cells to produce PD-L1 [

70].

Compared to M1 macrophages, M2-polarized TAMs—which are recognized for their pro-tumoral and immunosuppressive functions—express higher levels of Siglec-15. On TAMs, Siglec-15 expression can be increased by hypoxia, cytokines such as TGF-β, and signals from tumor cells. On TAMs, Siglec-15 inhibits the activity of CTLs. In contrast to PD-L1, which blocks T cells directly, Siglec-15 acts by modulating the immune suppression pathways mediated by TAMs. Siglec-15 increases the M2-like polarization of TAMs, helps in creating an immunosuppressive environment and promotes tumor cell invasion, extracellular matrix remodeling, and angiogenesis. On the other hand, Siglec-15 can create a TME that inhibit the immune system by the synthesis of metabolites such as lactate and arginase. [

69,

71,

72].

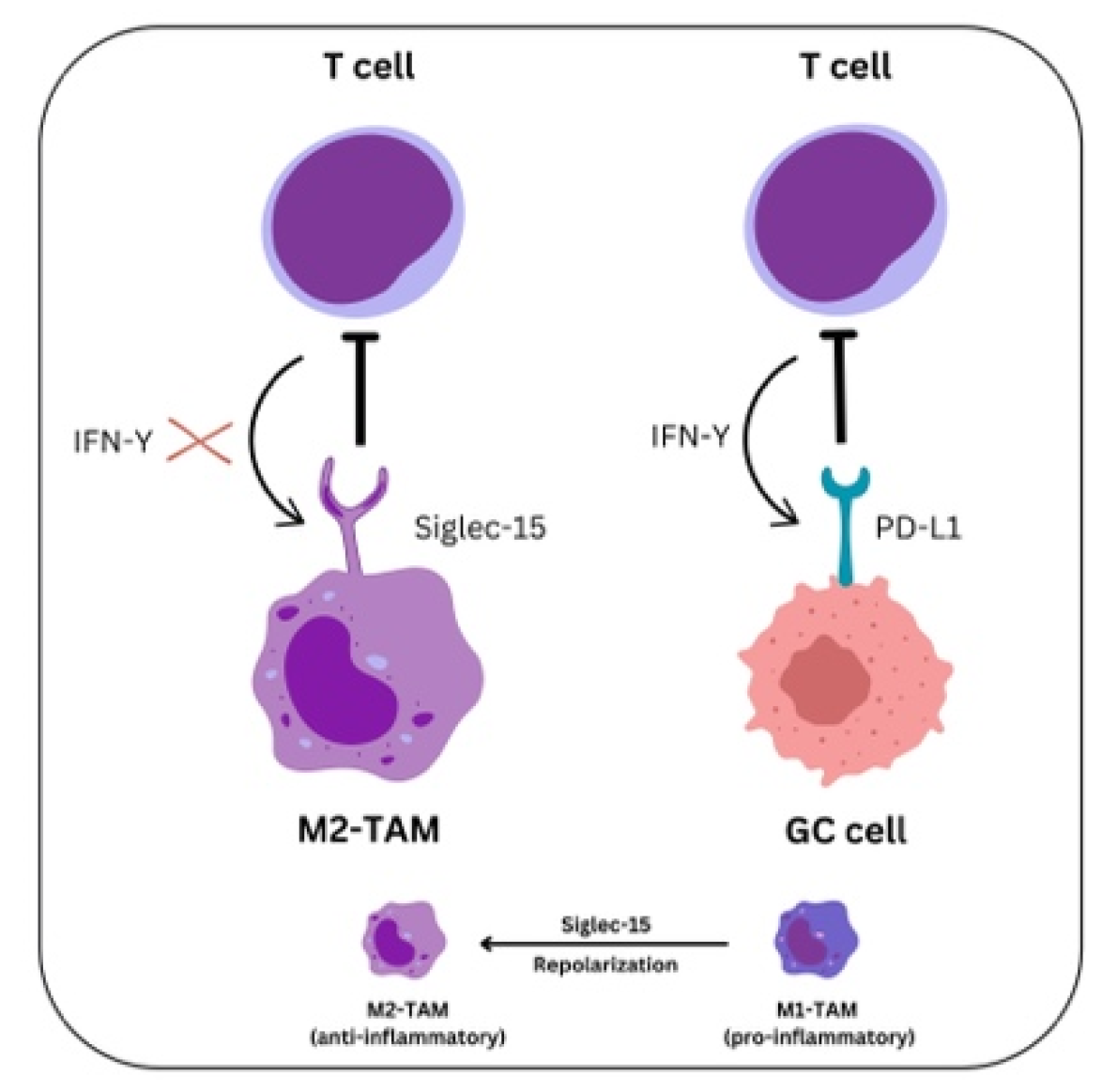

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of PD-L1 and Siglec-15 in modulating T cell functions in the TME The PD-L1 on GC cells and Siglec-15 on TAMs play complementary roles in inhibiting T-cell-mediated immunity. IFNγ from T cells induces upregulation of Siglec-15 expression on macrophages, thereby inhibiting their function. Similarly, tumor cells react to IFNγ by expressing PD-L1, which engages PD-1 on T cells, leading to T cell exhaustion.

Figure 2.

Mechanisms of PD-L1 and Siglec-15 in modulating T cell functions in the TME The PD-L1 on GC cells and Siglec-15 on TAMs play complementary roles in inhibiting T-cell-mediated immunity. IFNγ from T cells induces upregulation of Siglec-15 expression on macrophages, thereby inhibiting their function. Similarly, tumor cells react to IFNγ by expressing PD-L1, which engages PD-1 on T cells, leading to T cell exhaustion.

TAMs may be reprogrammed from an M2-like, immunosuppressive state to an M1-like, pro-inflammatory phenotype by Siglec-15 inhibitors or antibodies, as demonstrated in murine models. T-cell function may be restored, and anti-tumor immune responses may increase. Also, increased CTLs infiltration and tumor growth inhibition were noted [

73,

74,

75].

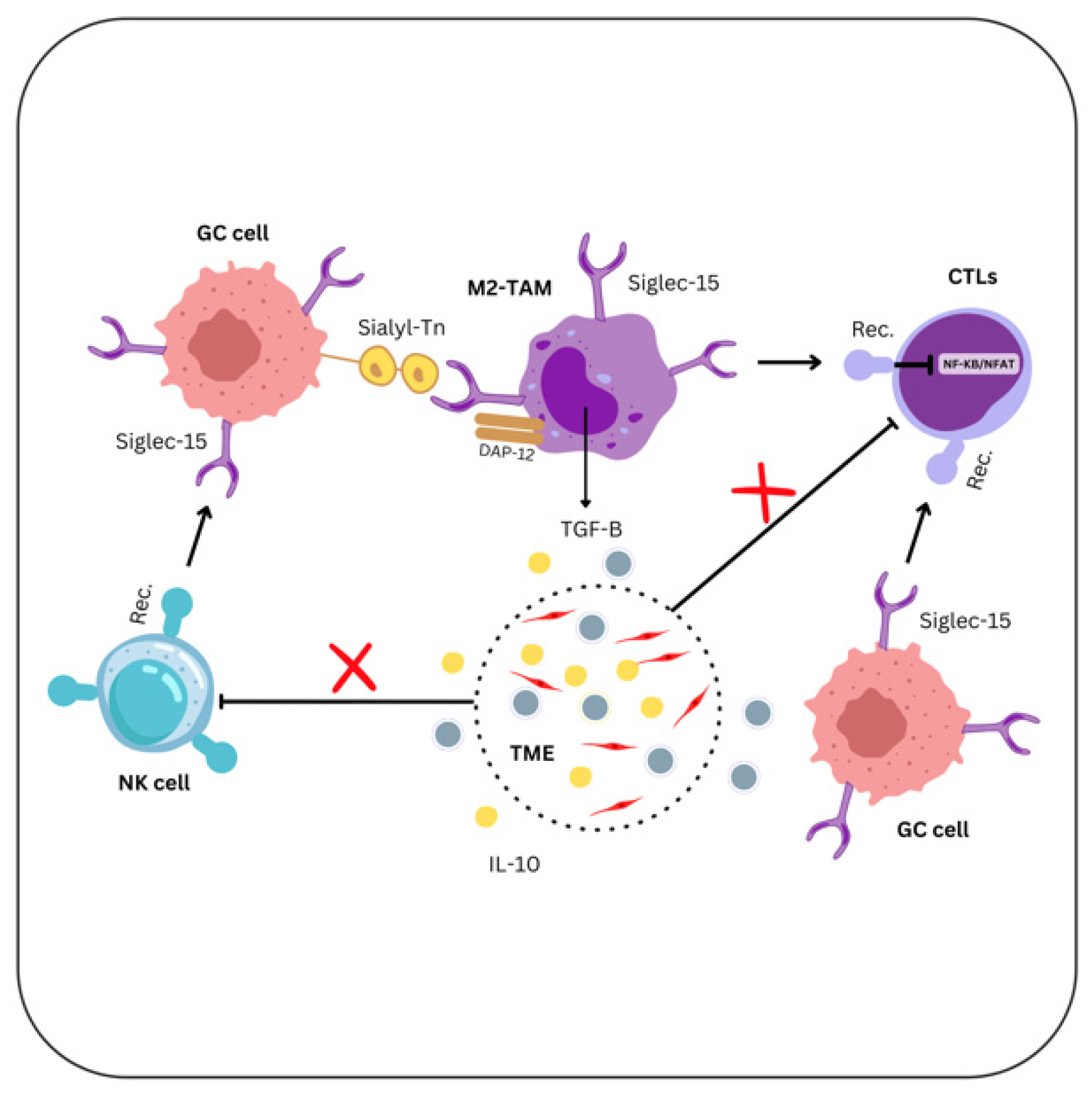

Figure 3.

The influence of Siglec-15-expressing GC cells on TME Sialyl-Tn expressed by tumor cells bind to Siglec-15 on TAMs. Siglec-15 stimulates the release of TGF-β and IL-10 to decrease the T-cell responses and interacts with DAP12 to modify TAMs’ activity. Siglec-15 also inhibits NF-κB/NFAT signaling, therefore reducing T-cell activation.

Figure 3.

The influence of Siglec-15-expressing GC cells on TME Sialyl-Tn expressed by tumor cells bind to Siglec-15 on TAMs. Siglec-15 stimulates the release of TGF-β and IL-10 to decrease the T-cell responses and interacts with DAP12 to modify TAMs’ activity. Siglec-15 also inhibits NF-κB/NFAT signaling, therefore reducing T-cell activation.

Additionally, a direct correlation between TAMs levels in GC tissue and tumor vascularity, invasion capacity, nodal status, and clinical stage was found [

76]. Therefore, GC may also benefit from a novel treatment approach that inhibits/TAMs recruitment and survival in tumors.

5. PD-1, PD-L1 and PD-L2

PD-1 (CD279), PD-L1 and Programmed Death-Ligand-2 (PD-L2) are members of the B7 family of cell-surface immune-regulatory proteins and crucial components of the immune checkpoint pathway, with an important role in anti-tumor immunity [

77].

PD-1 is a T-cell immune checkpoint that suppresses autoimmunity and promotes immune tolerance in cells expressing PD-L1 (B7-H1; CD274) and PD-L2 (B7-DC). PD-1 is preferentially expressed on activated B cells, NK cells, and Tregs, all contributing to the immunosuppressive TME. PD-L1 is expressed on the surface of several different immune cell types and tumor cells. T cells that are activated on the PD-1/PD-L1 receptor develop peripheral immunologic tolerance [

77,

78]. Multiple solid tumors, including GC takeover this immune barrier by expressing PD-L1, which creates an immunosuppressive TME and prevents T-cell cytolysis [

79]. PD-L2, a second ligand for PD-1, has a more restricted expression pattern, predominantly on dendritic cells, macrophages, and mast cells [

77,

78].

Oncogenic signaling can induce PD-L1 expression on solid tumor cells either using the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase-protein kinase B (PI3KAKT) pathway or janus kinase and signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT)3 signaling [

80,

81]. Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), produced by TILs is one of the most potent PD-L inducers. It upregulates PD-L1 expression on tumor cells through the JAK-STAT3 pathway and impairs the cytotoxicity of CTLs against the cancer cells. Furthermore, in GC tissue samples, PD-L1 expression on tumor cells positively correlates with the presence of CTLs in the stroma and IFN-γ expression in the tumor, suggesting that PD-1/PD-L1 antagonists function better in GC patients whose TME contains a significant proportion of CTLs [

82,

83].

TAMs are another important TME component that can induce PD-L1 expression in GC cells by releasing proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-8) which activate the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cell (NF-κB) and STAT3 signaling pathways [

84].

The CXCL9/10/11-CXCR3 signaling axis is induced by IFN-γ and is involved in attracting effector T cells (CTLs and Th1 cells), NK cells, and other immune cells to the TME. Excessive release of these chemokines can produce a pro-inflammatory environment, which can ironically help in tumor growth. When CXCR3 binds to its ligands (CXCL9/10/11), it initiate signaling pathways that promote immune cell migration and differentiation. [

85]. Chen-Lu Zhang et al. demonstrated that CXCL9/10/11-CXCR3 upregulates the expression of PD-L1 by activating the STAT3 and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways in GC cells [

86]. Also, they found a significant positive correlation between the expression of PD-L1 and CXCR3 in GC patient tissues [

86].

Neutrophils represent a large proportion of immune cells found in solid tumors, which exhibit different phenotypes according to the TME. Ting-ting Wang et al. showed that neutrophils with an activated and immunosuppressive phenotype (CD54+) enhance immunological suppression and the progression of GC through the GM-CSF-PD-L1 pathway [

87]. The GC TME promotes the survival and activation of these neutrophils, with tumor-derived GM-CSF playing a key role in inducing PD-L1 expression on neutrophils through the JAK-STAT3 signaling pathway. These activated PD-L1-expressing neutrophils suppress T cell function in a PD-L1-dependent manner and are associated with disease progression and poor patient survival [

87,

88].

AT-rich Interactive Domain-containing protein 1A (ARID1A) acts as a tumor suppressor gene, its mutations being linked to PD-L1 upregulation [

89]. A recent study examined the association between ARID1A loss and higher PD-L1 expression in a larger sample, showing a correlation with MSI-H and EBV status. In MSI-H GC, the degree of PD-L1 expression was even higher in tumors that had lost ARID1A [

90].

PD-L1 expression in GC varied depending on the molecular subtype.

Table 1.

PD-L1 expression in GC according to molecular subtypes.

Table 1.

PD-L1 expression in GC according to molecular subtypes.

| Characteristics |

EBV-positive GC |

MSI GC |

GS GC |

CIN GC |

| Molecular features |

✓ presence of EBV within the tumor cells ✓ high levels of DNA hypermethylation ✓ frequent PD-L1 and PD-L2 overexpression |

|

✓ absence of significant chromosomal alterations ✓ often associated with diffuse-type histology, including the presence of signet ring cells. |

|

| Immune cell infiltration |

|

|

✓ ↓ level of immune cell infiltration ✓ ↑immunosuppressive TME, with ↑ Tregs and MDSCs ⇒ inhibits effective immune responses |

|

| Immunotherapy response |

|

|

|

|

EBV-positive subtype has the highest rate of PD-L1 expression, both in tumor and immune cells in the TME [

91]. Ruri Saito et al. found that PD-L1 was overexpressed in 34% of the cancer cells and 45% of the immune cells in EBV-associated GC. Also, PD-L1 expression in this subtype was associated with diffuse histology and deeper tumor invasion [

92]. A meta-analysis studying the prognostic significance of PD-L1 in GC found that PD-L1 expression is a valuable predictor of prognosis as it is associated with shorter overall survival, higher T stage, and lymph node metastasis [

93]. MSI GC also demonstrates relatively high PD-L1 expression, this subtype being associated with a higher mutational burden activation, with PD-L1 expression particularly in immune cells [

94,

95]. In the GS GC, the PD-L1 expression is lower; some positivity may be seen in immune cells. In the CIN subtype, the expression is variable, usually in immune cells. As a result, EBV-positive and MSI GC patients are prime candidates for PD-1-directed therapy [

95].

6. Siglec-15

Siglec-15 is an immunomodulatory protein that gained interest due to its function in the immune system, especially in cancer therapy [

96]. Like PD-L1, Siglec-15 is a part of immune evasion strategies malignancies employ to decrease the immune response [

97].

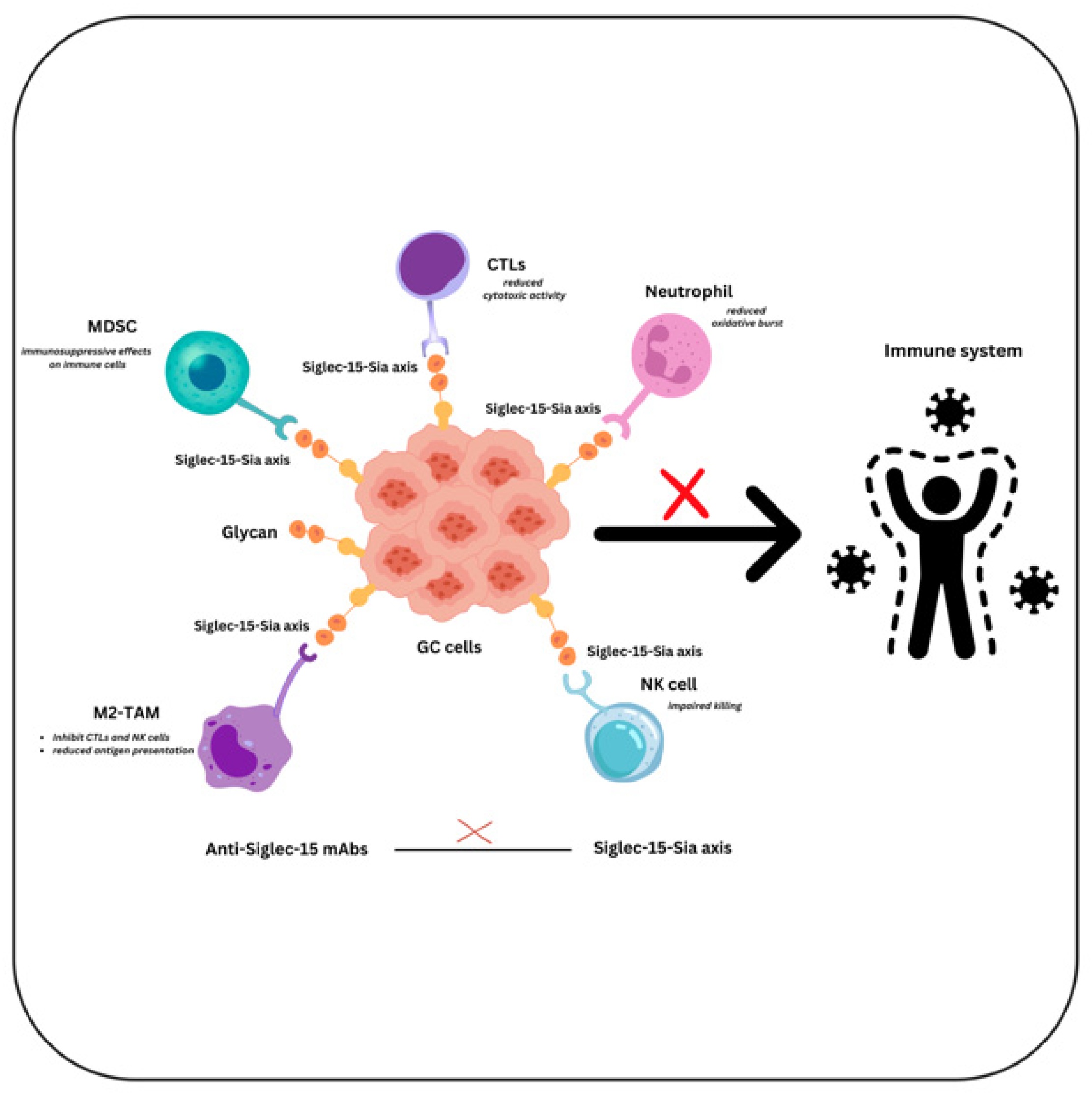

Figure 4.

The role of Siglec-15 in shaping immune responses in GC MDSCs, neutrophils, NK cells, TAMs, and other immune cells have Siglec-15 receptors that are bound by sialylated glycans expressed by gastric tumor cells. By inhibiting T-cell function and promoting tumor growth, these interactions result in immune evasion.

Figure 4.

The role of Siglec-15 in shaping immune responses in GC MDSCs, neutrophils, NK cells, TAMs, and other immune cells have Siglec-15 receptors that are bound by sialylated glycans expressed by gastric tumor cells. By inhibiting T-cell function and promoting tumor growth, these interactions result in immune evasion.

Even though anti-PD-1/PD-L1 is now the most effective immunotherapy for cancer treatment, most patients develop natural or acquired resistance. Other immune inhibitory mechanisms may be operating in conjunction with or alongside PD-1/PD-L1 inhibition in these resistant patients, offering novel immunological targets that could potentially increase the efficacy of cancer immunotherapy [

77].

Siglec-15 is one of the Siglec gene family members with a sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-type lectin structure. It consists of two Ig-like domains, a transmembrane domain with a lysine residue, and a short cytoplasmic tail, binding preferentially sialyl-Tn (sTn) [

73]. Normally, Siglec-15 mRNA is very low in most immune cell types and steady-state normal human tissues, being detected on macrophages and/or dendritic cells of the human spleen and lymph node [

73,

98]. Still, it is widely increased in human cancer cells and/or tumor-infiltrating macrophages/myeloid cells, in contrast to its minimal expression level on macrophages in normal tissues. When compared to the corresponding normal tissues, it is predominantly upregulated in colon, endometrioid, and thyroid tumors and highly expressed in bladder, kidney, lung, and liver malignancies [

99,

100].

Siglec-15 also shows high homology with B7 family members, and it is considered a macrophage-associated T-cell immunosuppressive molecule [

71]. In a recent paper analyzing the role of Siglec-15 in the suppression of T cell activity using various assays in both humans and mice, authors showed the suppressive role of Siglec-15 on antigen-specific T cell response in vivo, which is dependent on IL-10. However, in contrast to PD-L1 expression, Siglec-15 expression was inhibited by IFN-γ in vitro [

73].

Also, it was demonstrated that in human non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), Siglec-15 expression was mutually exclusive with PD-L (B7-H1), partially due to its induction by M-CSF and downregulation by IFN-γ [

11,

73,

101]. Moreover, macrophage-specific knockout of Siglec-15 in mice enhanced T cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity and slowed the tumor’s growth. In the same study, anti-Siglec-15 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) inhibited the growth of tumors and reduced the inhibitory effects of Siglec-15 on T cells [

73].

Several trials targeting Siglec-15 are ongoing. In one of them, the mAbs NC318 is assessed alone or in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC [

102,

103]. PYX-106, another novel blocking mAbs that targets Siglec-15, is being studied in a phase I clinical trial that includes patients with advanced solid tumors [

104].

In GC, Siglec-15 expression was associated with histological classification, angiolymphatic invasion, and surgical staging [

105,

106]. However, the current literature on Siglec-15 expression in GC remains limited and it is unknown if the mutual exclusivity between Siglec-15 and PD-L1 expression observed in NSCLC can be extended to GC. Further research is necessary to determine if similar regulatory mechanisms, immune evasion strategies, and checkpoint inhibition are applied to GC TME.

7. Conclusions

In summary, the complex interactions between Siglec-15, PD-L1, and TILs in the TME of GC reveal a dynamic and complex tumor immune milieu. Anti-tumor immunity and patient outcomes depends significantly on TILs density. On the other hand, the overexpression of immune checkpoints such as PD-L1 and Siglec-15 may compromise immune defense mechanisms resulting in treatment resistance.

The diversity of expression patterns and functions of PD-L1 and Siglec-15, along with the density and activity of TILs indicate that their global assessment may allow a better understanding of the immunological landscape diversity in GC. This may open the door to more individualized and successful immunotherapy approaches.

Future investigations should focus on the underlying processes of co-expression and interaction of these markers and their influence on clinical outcomes. Applying advanced immunohistochemistry with molecular pathology tools like next-generation sequencing and spatial transcriptomics, would allow a better understand these relationships could generate new combination of immunotherapies that favorably impact response and prognosis in GC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-R.C.-S., D.A.C. and O.S.C.; supervision, A.N., O.S.C.; validation, D.A.C., I.-G.C., A.-C.T. and O.S.C.; visualization, A.-H.S. and A.V.; writing—original draft, A.-R.C.-S., R.N., A.N.T. and A.N; writing—review & editing, D.M.C., A.V., A.-R.C.-S. and O.S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science, and Technology of Târgu Mureș Research Grant number 171/11/09.01.2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a PhD thesis from the Doctoral School of Medicine and Pharmacy within the University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Sciences, and Technology “George Emil Palade” of Targu Mures, entitled “The impact of the immunosuppressive molecules PD-L1 and Siglec-15 on TILs associated with gastric oncogenesis”. The thesis will be presented by A.-R.C.-S in 2025 (later this year).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

List of Abbreviations Used in the Main Text, Figures and Table

| A2AR |

Adenosine A2A Receptor |

| ARID1A |

AT-rich Interactive Domain-containing protein 1A |

| Bregs |

B Regulatory Cells |

| CIN |

Chromosomal Instability |

| CTLs |

Cytotoxic T Lymphocytes |

| CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 |

C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 9, 10, and 11 |

| CXCR3 |

C-X-C Motif Chemokine Receptor 3 |

| DAP12 |

DNAX-Activation Protein of 12 kDa |

| DCs |

Dendritic Cells |

| DNA |

Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| EBV |

Epstein-Barr Virus |

| EGFR |

epidermal growth factor receptor |

| Fas/FasL |

Fas/Fas Ligand |

| FDC |

follicular dendritic cell |

| FOXP3 |

Forkhead Box Protein P3 |

| GC |

Gastric Cancer |

| GS |

Genomic Stable |

| H. pylori |

Helicobacter pylori |

| HER-2 |

Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 |

| IFN-γ |

Interferon-gamma |

| Ig |

Immunoglobulin |

| IL-10 |

Interleukin-10 |

| IL-17 |

interleukin-17 |

| IL-21 |

interleukin-21 |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| IL-8 |

Interleukin-8 |

| JAK/STAT3 |

Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 |

| mAbs |

monoclonal antibodies |

| MDSCs |

Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells |

| MHC |

major histocompatibility complex |

| MMR |

Mismatch Repair |

| MSI |

Microsatellite Instability |

| NF-κB/NFAT |

Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells/Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cells |

| NK |

Natural Killer |

| NKG2D |

Natural Killer Group 2 Member D |

| NSCLC |

non-small cell lung cancer |

| PD-1 |

Programmed Cell Death-Protein-1 receptor |

| PD-L1 |

Programmed Cell Death Ligand-1 |

| PD-L2 |

Programmed Cell Death Ligand-2 |

| PGE2 |

Prostaglandin E2 |

| PI3K-AKT |

Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase-Protein Kinase B |

| RA |

Rheumatoid Arthritis |

| Sialyl-Tn |

Sialylated Tn Antigen |

| Siglec-15 |

Sialic Acid-Binding Immunoglobulin-Like Lectin 15 |

| TAMs |

Tumor-Associated Macrophages |

| TCR |

T Cell Receptor |

| TGF-β |

Transforming Growth Factor-beta |

| Th |

T helper |

| TILs |

Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes |

| TLSs |

Tertiary lymphoid structures |

| TME |

Tumor Microenvironment |

| TNF-α |

Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

| Tregs |

Regulatory T Cells |

| TRM |

Tissue-Resident Memory |

| VEGF |

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

References

- Filho, A.M.; Laversanne, M.; Ferlay, J.; Colombet, M.; Piñeros, M.; Znaor, A.; Parkin, D.M.; Soerjomataram, I.; & Bray, F. (2024). The GLOBOCAN 2022 cancer estimates: Data sources, methods, and a snapshot of the cancer burden worldwide. International journal of cancer, 10.1002/ijc.35278. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Cisło, M.; Filip, A.; Anna, Arnold Offerhaus, G.; Johan, Ciseł, B.; Rawicz-Pruszyński, K.; Skierucha, M.; Polkowski, W. Piotr Distinct molecular subtypes of gastric cancer: from Laurén to molecular pathology. Oncotarget. 2018; 9: 19427-19442. Available online: https://www.oncotarget.com/article/24827/text/.

- Kim, M.; & Seo, A.N. (2022). Molecular Pathology of Gastric Cancer. Journal of gastric cancer, 22(4), 273–305. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, W.G.; Kwon, C.H.; et al. Differences in immune contextures among different molecular subtypes of gastric cancer and their prognostic impact. Gastric Cancer 22, 1164–1175 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Hu, R.; Zhang, K.; Guo, T.; Chen, B.; Jiang, X.; & Cui, R. (2022). Characterization of Immune-Related Molecular Subtypes and a Prognostic Signature Correlating With the Response to Immunotherapy in Patients With Gastric Cancer. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 939836. [CrossRef]

- Ma, E.S.; Wang, Z.X.; Zhu, M.Q.; & Zhao, J. (2022). Immune evasion mechanisms and therapeutic strategies in gastric cancer. World journal of gastrointestinal oncology, 14(1), 216–229. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, T.; Huang, T.; Shang, M.; & Wang, X. (2022). The mechanisms on evasion of anti-tumor immune responses in gastric cancer. Frontiers in oncology, 12, 943806. [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Jing, H.; Wang, C.; Wang, W.; Cui, Y.; Chen, J.; & Sha, D. (2021). Prognostic role of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes assessed by H&E-stained section in gastric cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open, 11(1), e044163. [CrossRef]

- Cao, X.; Kang, Y.; Tai, P.; Zhang, P.; Lin, X.; Xu, F.; Nie, Z.; & He, B. (2024). Prognostic role of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinics and research in hepatology and gastroenterology, 49(1), 102510. Ad-vance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.M.; Tsai, C.L.; Kao, J.T.; Hsieh, C.T.; Shieh, D.C.; Lee, Y.J.; Tsay, G.J.; Cheng, K.S.; & Wu, Y.Y. (2018). PD-1 and PD-L1 Up-regulation Promotes T-cell Apoptosis in Gastric Adenocarcinoma. Anticancer research, 38(4), 2069–2078. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Lu, Q.; Sanmamed, M.F.; & Wang, J. (2021). Siglec-15 as an Emerging Target for Next-generation Cancer Immunotherapy. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, 27(3), 680–688. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Guo, Y.; Li, B.; et al. Siglec-15 on macrophages suppress the immune microenvironment in patients with PD-L1 negative non-metastasis lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Gene Ther 31, 427–438 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Ren, X. (2019). Immunosuppressive checkpoint Siglec-15: a vital new piece of the cancer immunotherapy jigsaw puzzle. Cancer biology & medicine, 16(2), 205–210. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Mo, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, H.; Lu, Z.; Yu, S.; & Chen, J. (2022). Analysis of a novel immune checkpoint, Siglec-15, in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. The journal of pathology. Clinical research, 8(3), 268–278. [CrossRef]

- Paijens, S.T.; Vledder, A.; de Bruyn, M.; et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in the immunotherapy era. Cell Mol Immunol 18, 842–859 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Frankowska, K.; Zarobkiewicz, M.; Dąbrowska, I.; et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and radiological picture of the tumor. Med Oncol 40, 176 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Gong, L.P.; Chen, J.N.; Xiao, L.; He, Q.; Feng, Z.Y.; Zhang, Z.G.; Liu, J.P.; Wei, H.B.; & Shao, C.K. (2019). The implication of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma. Human pathology, 85, 82–91. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Li, J.; Hao, Y.; Nie, Y.; Li, Z.; Qian, M.; Liang, Q.; Yu, J.; Zeng, M.; & Wu, K. (2017). Differentiated tumor immune micro-environment of Epstein–Barr virus-associated and negative gastric cancer: implication in prognosis and immunotherapy. On-cotarget, 8, 67094 - 67103.

- Knochelmann, H.M.; Dwyer, C.J.; Bailey, S.R.; et al. When worlds collide: Th17 and Treg cells in cancer and autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol 15, 458–469 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Wegrzyn, A.S.; Kedzierska, A.E.; & Obojski, A. (2023). Identification and classification of distinct surface markers of T regulatory cells. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 1055805. [CrossRef]

- Alcover, A.; Alarcón, B.; & Di Bartolo, V. (2018). Cell Biology of T Cell Receptor Expression and Regulation. Annual review of immunology, 36, 103–125. [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Li, C.; Cai, X.; Xie, Z.; Zhou, L.; Cheng, B.; Zhong, R.; Xiong, S.; Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Yu, Z.; He, J.; & Liang, W. (2021). The association between CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and the clinical outcome of cancer immunotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 41, 101134. [CrossRef]

- Lieberman, J. (2010). Anatomy of a murder: how cytotoxic T cells and NK cells are activated, develop, and eliminate their targets. Immunological reviews, 235(1), 5–9. [CrossRef]

- Jameson, S.C.; & Masopust, D. (2018). Understanding Subset Diversity in T Cell Memory. Immunity, 48(2), 214–226. [CrossRef]

- Golubovskaya, V.; & Wu, L. (2016). Different Subsets of T Cells, Memory, Effector Functions, and CAR-T Immunotherapy. Cancers, 8(3), 36. [CrossRef]

- Kaech, S.M.; Wherry, E.J.; & Ahmed, R. (2002). Effector and memory T-cell differentiation: implications for vaccine development. Nature reviews. Immunology, 2(4), 251–262. [CrossRef]

- Damei, I.; Trickovic, T.; Mami-Chouaib, F.; & Corgnac, S. (2023). Tumor-resident memory T cells as a biomarker of the response to cancer immunotherapy. Frontiers in immunology, 14, 1205984. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Bergsbaken, T.; & Edelblum, K.L. (2022). The multifunctional nature of CD103 (αEβ7 integrin) signaling in tissue-resident lymphocytes. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology, 323(4), C1161–C1167. [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, P.M.; Reed, S.J.; Kalia, V.; & Sarkar, S. (2021). Solid Tumor Microenvironment Can Harbor and Support Functional Properties of Memory T Cells. Frontiers in immunology, 12, 706150. [CrossRef]

- Beumer-Chuwonpad, A.; Taggenbrock, R.L.R.E.; Ngo, T.A.; & van Gisbergen, K.P.J.M. (2021). The Potential of Tissue-Resident Memory T Cells for Adoptive Immunotherapy against Cancer. Cells, 10(9), 2234. [CrossRef]

- Simoni, Y.; Becht, E.; Fehlings, M.; Loh, C.Y.; Koo, S.L.; Teng, K.W.W.; Yeong, J.P.S.; Nahar, R.; Zhang, T.; Kared, H.; Duan, K.; Ang, N.; Poidinger, M.; Lee, Y.Y.; Larbi, A.; Khng, A.J.; Tan, E.; Fu, C.; Mathew, R.; Teo, M.; … Newell, E.W. (2018). Bystander CD8+ T cells are abundant and phenotypically distinct in human tumour infiltrates. Nature, 557(7706), 575–579. [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.; Hu, J.; Ping, Y.; Xu, L.; Liao, G.; Jiang, Z.; Pang, B.; Sun, S.; Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; & Li, X. (2021). Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals a Tumor-Reactive T Cell Signature Associated With Clinical Outcome and Immunotherapy Response In Melanoma. Frontiers in immunology, 12, 758288. [CrossRef]

- Borràs, D.M.; Verbandt, S.; Ausserhofer, M.; Sturm, G.; Lim, J.; Verge, G.A.; Vanmeerbeek, I.; Laureano, R.S.; Govaerts, J.; Sprooten, J.; Hong, Y.; Wall, R.; De Hertogh, G.; Sagaert, X.; Bislenghi, G.; D’Hoore, A.; Wolthuis, A.; Finotello, F.; Park, W.Y.; Naulaerts, S.; … Garg, A.D. (2023). Single cell dynamics of tumor specificity vs. bystander activity in CD8+ T cells define the diverse immune landscapes in colorectal cancer. Cell discovery, 9(1), 114. [CrossRef]

- Martín-Sierra, C.; Martins, R.; Laranjeira, P.; Coucelo, M.; Abrantes, A.M.; Oliveira, R.C.; Tralhão, J.G.; Botelho, M.F.; Furtado, E.; Domingues, M.R.; & Paiva, A. (2019). Functional and Phenotypic Characterization of Tumor-Infiltrating Leukocyte Subsets and Their Contribution to the Pathogenesis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Cholangiocarcinoma. Translational oncology, 12(11), 1468–1479. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Tan, B.; Ai, J.; Zhang, Z.; Song, J.; & Shan, B. (2013). Prevalence of Th17 and Treg cells in gastric cancer patients and its correlation with clinical parameters. Oncology reports, 30(3), 1215–1222. [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhu, S.; Dong, Q.; Zhang, S.; Ma, J.; & Zhou, C. (2018). Expression of Th17/Treg related molecules in gastric cancer tissues. The Turkish journal of gastroenterology : the official journal of Turkish Society of Gastroenterology, 29(1), 45–51. [CrossRef]

- Kindlund, B.; Sjöling, Å.; Yakkala, C.; Adamsson, J.; Janzon, A.; Hansson, L.E.; Hermansson, M.; Janson, P.; Winqvist, O.; & Lundin, S.B. (2017). CD4+ regulatory T cells in gastric cancer mucosa are proliferating and express high levels of IL-10 but little TGF-β. Gastric cancer : official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association, 20(1), 116–125. [CrossRef]

- Ng, T.H.; Britton, G.J.; Hill, E.V.; Verhagen, J.; Burton, B.R.; & Wraith, D.C. (2013). Regulation of adaptive immunity; the role of interleukin-10. Frontiers in immunology, 4, 129. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.A.; Li, X.L.; Mo, Y.Z.; Fan, C.M.; Tang, L.; Xiong, F.; Guo, C.; Xiang, B.; Zhou, M.; Ma, J.; Huang, X.; Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Li, G.Y.; Zeng, Z.Y.; & Xiong, W. (2018). Effects of tumor metabolic microenvironment on regulatory T cells. Molecular cancer, 17(1), 168. [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; He, Y.; Huang, J.; Tao, Y.; & Liu, S. (2021). Metabolism of Dendritic Cells in Tumor Microenvironment: For Immuno-therapy. Frontiers in immunology, 12, 613492. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.S.; Lin, J.T.; Hsu, P.N.; Lin, C.Y.; Hsieh, Y.T.; Chiu, Y.H.; Hsueh, P.R.; & Liao, K.W. (2007). Preferential induction of transforming growth factor-beta production in gastric epithelial cells and monocytes by Helicobacter pylori soluble proteins. The Journal of infectious diseases, 196(9), 1386–1393. [CrossRef]

- Kao, J.Y.; Zhang, M.; Miller, M.J.; Mills, J.C.; Wang, B.; Liu, M.; Eaton, K.A.; Zou, W.; Berndt, B.E.; Cole, T.S.; Takeuchi, T.; Owyang, S.Y.; & Luther, J. (2010). Helicobacter pylori immune escape is mediated by dendritic cell-induced Treg skewing and Th17 suppression in mice. Gastroenterology, 138(3), 1046–1054. [CrossRef]

- Larussa, T.; Leone, I.; Suraci, E.; Imeneo, M.; & Luzza, F. (2015). Helicobacter pylori and T Helper Cells: Mechanisms of Immune Escape and Tolerance. Journal of immunology research, 2015, 981328. [CrossRef]

- Rezalotfi, A.; Ahmadian, E.; Aazami, H.; Solgi, G.; & Ebrahimi, M. (2019). Gastric Cancer Stem Cells Effect on Th17/Treg Balance; A Bench to Beside Perspective. Frontiers in oncology, 9, 226. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Huang, X.; Han, X.; Zhang, J.; Gao, L.; & Chen, H. (2024). IL-17A in gastric carcinogenesis: good or bad?. Frontiers in immunology, 15, 1501293. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Q.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, B.; Lin, J.; Tang, Y.; Li, F.; Yang, C.S.; Wang, T.C.; & Tu, S. (2020). Bone Marrow-Derived Myofibroblasts Promote Gastric Cancer Metastasis by Activating TGF-β1 and IL-6/STAT3 Signalling Loop. OncoTargets and therapy, 13, 10567–10580. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Chen, X.; Herjan, T.; & Li, X. (2020). The role of interleukin-17 in tumor development and progression. The Journal of experimental medicine, 217(1), e20190297. [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, T.; Kono, K.; Mizukami, Y.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Mimura, K.; Watanabe, M.; Izawa, S.; & Fujii, H. (2010). Distribution of Th17 cells and FoxP3(+) regulatory T cells in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, tumor-draining lymph nodes and peripheral blood lymphocytes in patients with gastric cancer. Cancer science, 101(9), 1947–1954. [CrossRef]

- Downs-Canner, S.M.; Meier, J.; Vincent, B.G.; & Serody, J.S. (2022). B Cell Function in the Tumor Microenvironment. Annual review of immunology, 40, 169–193. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, E.; Ding, C.; Li, S.; Zhou, X.; Aikemu, B.; Fan, X.; Sun, J.; Zheng, M.; & Yang, X. (2023). Roles and mechanisms of tu-mour-infiltrating B cells in human cancer: a new force in immunotherapy. Biomarker research, 11(1), 28. [CrossRef]

- Michaud, D.; Steward, C.R.; Mirlekar, B.; & Pylayeva-Gupta, Y. (2021). Regulatory B cells in cancer. Immunological reviews, 299(1), 74–92. [CrossRef]

- Catalán, D.; Mansilla, M.A.; Ferrier, A.; Soto, L.; Oleinika, K.; Aguillón, J.C.; & Aravena, O. (2021). Immunosuppressive Mechanisms of Regulatory B Cells. Frontiers in immunology, 12, 611795. [CrossRef]

- Sarvaria, A.; Madrigal, J.A.; & Saudemont, A. (2017). B cell regulation in cancer and anti-tumor immunity. Cellular & molecular immunology, 14(8), 662–674. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, H.; Dobosz, A.; Cwynar-Zając, Ł.; Nowak, P.; Czyżewski, M.; Barg, M.; Reichert, P.; Królikowska, A.; & Barg, E. (2022). Unraveling the role of Breg cells in digestive tract cancer and infectious immunity. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 981847. [CrossRef]

- Sautès-Fridman, C.; Lawand, M.; Giraldo, N.A.; Kaplon, H.; Germain, C.; Fridman, W.H.; & Dieu-Nosjean, M.C. (2016). Tertiary Lymphoid Structures in Cancers: Prognostic Value, Regulation, and Manipulation for Therapeutic Intervention. Frontiers in immunology, 7, 407. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; & Wu, S. (2023). Tertiary lymphoid structures are critical for cancer prognosis and therapeutic response. Frontiers in immunology, 13, 1063711. [CrossRef]

- Yamakoshi, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Sakimura, C.; Deguchi, S.; Mori, T.; Tamura, T.; Toyokawa, T.; Muguruma, K.; Hirakawa, K.; & Ohira, M. (2020). Immunological potential of tertiary lymphoid structures surrounding the primary tumor in gastric cancer. Interna-tional journal of oncology, 57(1), 171–182. [CrossRef]

- Groen-van Schooten, T.S.; Franco Fernandez, R.; van Grieken, N.C.T.; Bos, E.N.; Seidel, J.; Saris, J.; Martínez-Ciarpaglini, C.; Fleitas, T.C.; Thommen, D.S.; de Gruijl, T.D.; Grootjans, J.; & Derks, S. (2024). Mapping the complexity and diversity of tertiary lymphoid structures in primary and peritoneal metastatic gastric cancer. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer, 12(7), e009243. [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.; Wu, X.; Zhang, C.; Liang, Y.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, H.; Shen, L.; & Chen, Y. (2024). Analyzing the associations between tertiary lymphoid structures and postoperative prognosis, along with immunotherapy response in gastric cancer: findings from pooled cohort studies. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology, 150(3), 153. [CrossRef]

- Wolf, N.K.; Kissiov, D.U.; & Raulet, D.H. (2023). Roles of natural killer cells in immunity to cancer, and applications to im-munotherapy. Nature reviews. Immunology, 23(2), 90–105. [CrossRef]

- Sanseviero, E. (2019). NK Cell-Fc Receptors Advance Tumor Immunotherapy. Journal of clinical medicine, 8(10), 1667. [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; & Wei, Y. (2019). Therapeutic Potential of Natural Killer Cells in Gastric Cancer. Frontiers in immunology, 9, 3095. [CrossRef]

- Yajima, T.; Hoshino, K.; Muranushi, R.; Mogi, A.; Onozato, R.; Yamaki, E.; Kosaka, T.; Tanaka, S.; Shirabe, K.; Yoshikai, Y.; & Kuwano, H. (2019). Fas/FasL signaling is critical for the survival of exhausted antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during tumor immune response. Molecular immunology, 107, 97–105. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.Y.; Feng, Y.; Mao, Q.S.; Ma, P.; Liu, J.Z.; Lu, W.; Liu, Y.F.; Chen, X.; Hu, Y.L.; & Xue, W.J. (2020). Diagnostic and prognostic value of the peripheral natural killer cell levels in gastric cancer. Experimental and therapeutic medicine, 20(4), 3816–3822. [CrossRef]

- Saito, H.; Osaki, T.; & Ikeguchi, M. (2012). Decreased NKG2D expression on NK cells correlates with impaired NK cell function in patients with gastric cancer. Gastric cancer : official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association, 15(1), 27–33. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Yu, J.; Hu, Y.; Mou, T.; Chen, G.; & Li, G. (2015). Gastric cancer cells inhibit natural killer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis via prostaglandin E2. Oncoimmunology, 5(2), e1069936. [CrossRef]

- Rafei, H.; Daher, M.; & Rezvani, K. (2021). Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) natural killer (NK)-cell therapy: leveraging the power of innate immunity. British journal of haematology, 193(2), 216–230. [CrossRef]

- Scheck, M.K.; Hofheinz, R.D.; & Lorenzen, S. (2024). HER2-Positive Gastric Cancer and Antibody Treatment: State of the Art and Future Developments. Cancers, 16(7), 1336. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xu, X.; Wei, S.; Jiang, P.; Xue, L.; Wang, J.; Senior Correspondence. (2021). Tumor-associated macrophages: potential therapeutic strategies and future prospects in cancer. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer, 9(1), e001341. [CrossRef]

- Yerolatsite, M.; Torounidou, N.; Gogadis, A.; Kapoulitsa, F.; Ntellas, P.; Lampri, E.; Tolia, M.; Batistatou, A.; Katsanos, K.; & Mauri, D. (2023). TAMs and PD-1 Networking in Gastric Cancer: A Review of the Literature. Cancers, 16(1), 196. [CrossRef]

- Takamiya, R.; Ohtsubo, K.; Takamatsu, S.; Taniguchi, N.; & Angata, T. (2013). The interaction between Siglec-15 and tu-mor-associated sialyl-Tn antigen enhances TGF-β secretion from monocytes/macrophages through the DAP12-Syk pathway. Glycobiology, 23(2), 178–187. [CrossRef]

- Bai, R.; Li, Y.; Jian, L.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, L.; & Wei, M. (2022). The hypoxia-driven crosstalk between tumor and tumor-associated macrophages: mechanisms and clinical treatment strategies. Molecular cancer, 21(1), 177. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Liu, L.N.; Flies, D.B.; Nie, X.; Toki, M.; Zhang, J.; Song, C.; Zarr, M.; Zhou, X.; Han, X.; Archer, K.A.; O’Neill, T.; Herbst, R.S.; Boto, A.N.; Sanmamed, M.F.; Langermann, S.; Rimm, D.L.; & Chen, L. (2019). Siglec-15 as an immune suppressor and potential target for normalization cancer immunotherapy. Nature medicine, 25(4), 656–666. [CrossRef]

- Kang, F.B.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.; & Zhang, Y.Z. (2020). The diverse functions of Siglec-15 in bone remodeling and antitumor responses. Pharmacological research, 155, 104728. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.Y.; Qi, L.L.; Kang, F.B.; & Wang, L. (2022). The intriguing roles of Siglec family members in the tumor microenvi-ronment. Biomarker research, 10(1), 22. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; & Ju, X. (2021). Research progress on tumour associated macrophages in gastric cancer (Review). Oncology Reports, 45, 35. [CrossRef]

- Parvez, A.; Choudhary, F.; Mudgal, P.; Khan, R.; Qureshi, K.A.; Farooqi, H.; & Aspatwar, A. (2023). PD-1 and PD-L1: architects of immune symphony and immunotherapy breakthroughs in cancer treatment. Frontiers in immunology, 14, 1296341. [CrossRef]

- Keir, M.E.; Butte, M.J.; Freeman, G.J.; & Sharpe, A.H. (2008). PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annual review of immunology, 26, 677–704. [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.W.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yang, H.K.; Dong, J.M.; Xiao, Z.H.; He, X.; Guo, J.H.; Wang, R.Q.; Dai, B.; & Zhou, Z.L. (2024). Tumor immunotherapy resistance: Revealing the mechanism of PD-1/PD-L1-mediated tumor immune escape. Biomedicine & pharma-cotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 171, 116203. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, C.C.; Jin, L.; & Zhang, X.D. (2016). Regulation of PD-L1: a novel role of pro-survival signalling in cancer. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 27(3), 409–416. [CrossRef]

- Song, T.L.; Nairismägi, M.L.; Laurensia, Y.; Lim, J.Q.; Tan, J.; Li, Z.M.; Pang, W.L.; Kizhakeyil, A.; Wijaya, G.C.; Huang, D.C.; Nagarajan, S.; Chia, B.K.; Cheah, D.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, F.; Rao, H.L.; Tang, T.; Wong, E.K.; Bei, J.X.; Iqbal, J.; … Ong, C.K. (2018). Oncogenic activation of the STAT3 pathway drives PD-L1 expression in natural killer/T-cell lymphoma. Blood, 132(11), 1146–1158. [CrossRef]

- Mandai, M.; Hamanishi, J.; Abiko, K.; Matsumura, N.; Baba, T.; & Konishi, I. (2016). Dual Faces of IFNγ in Cancer Progression: A Role of PD-L1 Induction in the Determination of Pro- and Antitumor Immunity. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, 22(10), 2329–2334. [CrossRef]

- Mimura, K.; Teh, J.L.; Okayama, H.; Shiraishi, K.; Kua, L.F.; Koh, V.; Smoot, D.T.; Ashktorab, H.; Oike, T.; Suzuki, Y.; Fazreen, Z.; Asuncion, B.R.; Shabbir, A.; Yong, W.P.; So, J.; Soong, R.; & Kono, K. (2018). PD-L1 expression is mainly regulated by in-terferon gamma associated with JAK-STAT pathway in gastric cancer. Cancer science, 109(1), 43–53. [CrossRef]

- Ju, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, M.; & Wang, Q. (2020). Tumor-associated macrophages induce PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer cells through IL-6 and TNF-ɑ signaling. Experimental cell research, 396(2), 112315. [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, R.; Zhang, W.; Naseem, M.; Puccini, A.; Berger, M.D.; Soni, S.; McSkane, M.; Baba, H.; & Lenz, H.J. (2018). CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11/CXCR3 axis for immune activation - A target for novel cancer therapy. Cancer treatment reviews, 63, 40–47.

- Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Xu, L.; Che, X.; Wen, T.; Fan, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Qu, X.; & Liu, Y. (2018). CXCL9/10/11, a regulator of PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer. BMC cancer, 18(1), 462. [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.T.; Zhao, Y.L.; Peng, L.S.; Chen, N.; Chen, W.; Lv, Y.P.; Mao, F.Y.; Zhang, J.Y.; Cheng, P.; Teng, Y.S.; Fu, X.L.; Yu, P.W.; Guo, G.; Luo, P.; Zhuang, Y.; & Zou, Q.M. (2017). Tumour-activated neutrophils in gastric cancer foster immune suppression and disease progression through GM-CSF-PD-L1 pathway. Gut, 66(11), 1900–1911. [CrossRef]

- Shan, Z.G.; Yan, Z.B.; Peng, L.S.; Cheng, P.; Teng, Y.S.; Mao, F.Y.; Fan, K.; Zhuang, Y.; & Zhao, Y.L. (2021). Granulo-cyte-Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor-Activated Neutrophils Express B7-H4 That Correlates with Gastric Cancer Pro-gression and Poor Patient Survival. Journal of immunology research, 2021, 6613247. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; & Lee, C.S. (2023). The Role of the AT-Rich Interaction Domain 1A Gene (ARID1A) in Human Carcinogenesis. Genes, 15(1), 5. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.B.; Ahn, J.M.; Bae, W.J.; Sung, C.O.; & Lee, D. (2019). Functional loss of ARID1A is tightly associated with high PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer. International journal of cancer, 145(4), 916–926. [CrossRef]

- Nakano, H.; Saito, M.; Nakajima, S.; Saito, K.; Nakayama, Y.; Kase, K.; Yamada, L.; Kanke, Y.; Hanayama, H.; Onozawa, H.; Okayama, H.; Fujita, S.; Sakamoto, W.; Saze, Z.; Momma, T.; Mimura, K.; Ohki, S.; Goto, A.; & Kono, K. (2021). PD-L1 over-expression in EBV-positive gastric cancer is caused by unique genomic or epigenomic mechanisms. Scientific reports, 11(1), 1982. [CrossRef]

- Saito, R.; Abe, H.; Kunita, A.; Yamashita, H.; Seto, Y.; & Fukayama, M. (2017). Overexpression and gene amplification of PD-L1 in cancer cells and PD-L1+ immune cells in Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric cancer: the prognostic implications. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc, 30(3), 427–439. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Dong, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Xuan, Q.; Wang, Y.; & Zhang, Q. (2016). The clinicopathological and prognostic significance of PD-L1 expression in gastric cancer: a meta-analysis of 10 studies with 1,901 patients. Scientific reports, 6, 37933. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Nered, S.; Tryakin, A.; Abgaryan, M.; Artamonova, E.; Stroganova, A.; Stilidi, I. (2024). Microsatellite instability (MSI) in patients with gastric cancer (GC) and correlation with PD-L1 expression. JCO 42, 389-389(2024). [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, W.G.; Kwon, C.H.; & Park, D.Y. (2019). Differences in immune contextures among different molecular subtypes of gastric cancer and their prognostic impact. Gastric cancer : official journal of the International Gastric Cancer Association and the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association, 22(6), 1164–1175. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.Y.; Qi, L.L.; Liu, X.B.; Wang, Y.; & Wang, L. (2023). Prognostic value of Siglec-15 expression in patients with solid tumors: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in oncology, 12, 1073932. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Tian, X.; Yan, L.; Guan, X.; Dong, B.; Zhao, M.; Lv, A.; Liu, D.; Wu, J.; & Hao, C. (2022). Expression and function of Siglec-15 in RLPS and its correlation with PD-L1: Bioinformatics Analysis and Clinicopathological Evidence. International journal of medical sciences, 19(13), 1977–1988. [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Zheng, J.; Shao, Y.; Zhu, L.; & Yang, T. (2023). Siglec-15 as multifunctional molecule involved in osteoclast differen-tiation, cancer immunity and microbial infection. Progress in biophysics and molecular biology, 177, 34–41. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, B.; Wang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wei, F.; Ren, X.; & Yang, L. (2020). Expression signature, prognosis value, and immune characteristics of Siglec-15 identified by pan-cancer analysis. Oncoimmunology, 9(1), 1807291. [CrossRef]

- Shafi, S.; Aung, T.N.; Robbins, C.; Zugazagoitia, J.; Vathiotis, I.; Gavrielatou, N.; Yaghoobi, V.; Fernandez, A.; Niu, S.; Liu, L.N.; Cusumano, Z.T.; Leelatian, N.; Cole, K.; Wang, H.; Homer, R.; Herbst, R.S.; Langermann, S.; & Rimm, D.L. (2022). Development of an immunohistochemical assay for Siglec-15. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology, 102(7), 771–778. [CrossRef]

- Hao, J.Q.; Nong, J.Y.; Zhao, D.; Li, H.Y.; Su, D.; Zhou, L.J.; Dong, Y.J.; Zhang, C.; Che, N.Y.; Zhang, S.C.; Lin, J.Z.; Yang, J.B.; Zhang, H.T.; & Wang, J.H. (2020). The significance of Siglec-15 expression in resectable non-small cell lung cancer. Neoplasma, 67(6), 1214–1222. [CrossRef]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025). The Study of NC318 Alone or in Combination With Pembrolizumab in Patients With Advanced Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04699123. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04699123?cond=NC318&rank=2 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Tolcher, A.; Hamid, O.; Weber, J.; LoRusso, P.; Shantz, K.; Heller, K.; & Gutierrez, M. (2019, November). Single agent anti-tumor activity in PD-1 refractory NSCLC: phase 1 data from the first-in-human trial of NC318, a Siglec-15-targeted antibody. In JOURNAL FOR IMMUNOTHERAPY OF CANCER (Vol. 7). CAMPUS, 4 CRINAN ST, LONDON N1 9XW, ENGLAND: BMC.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025). Study of PYX-106 in Solid Tumors.

- ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05718557. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05718557 (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Quirino, M.W.L.; Pereira, M.C.; Deodato de Souza, M.F.; Pitta, I.D.R.; Da Silva Filho, A.F.; Albuquerque, M.S.S.; Albuquerque, A.P.B.; Martins, M.R.; Pitta, M.G.D.R.; & Rêgo, M.J.B.M. (2021). Immunopositivity for Siglec-15 in gastric cancer and its association with clinical and pathological parameters. European journal of histochemistry : EJH, 65(1), 3174. [CrossRef]

- Moreira, R.S.; da Silva, M.M.; de Melo Vasconcelos, C.F.; da Silva, T.D.; Cordeiro, G.G.; Mattos-Jr, L.A.R.; da Rocha Pitta, M.G.; de Melo Rêgo, M.J.B.; & Pereira, M.C. (2023). Siglec 15 as a biomarker or a druggable molecule for non-small cell lung cancer. Journal of cancer research and clinical oncology, 149(19), 17651–17661. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).