1. Introduction

It is possible to harvest so-called salinity gradient energy (SGE) from two salt solutions with different salt concentrations by means of reversible mixing. The amount of this Gibbs energy is small compared to energy contained in fossil fuels. For example, the theoretical potential of 1 m

3 of river water with an equal amount of seawater is approximately 1.5 MJ (0.5 kWh) while the same volume of gasoline represents 32.2 GJ (895 kWh) or approximately 20 000 times as much. It is clear that SGE can only be economically attractive if both feed waters are available close to each other and if pre-treatment and pumping are carried out very efficiently. Worldwide, there is - if all river water is used - a potential of 2.7 TW [

1], which is comparable to the average global electricity consumption of 3 TW [

2] and this huge amount is an incentive to develop methods to exploit this energy source. The main possible sources for SGE are river water, sea water, concentrate from reverse osmosis desalination units as well as brine from salt lakes.

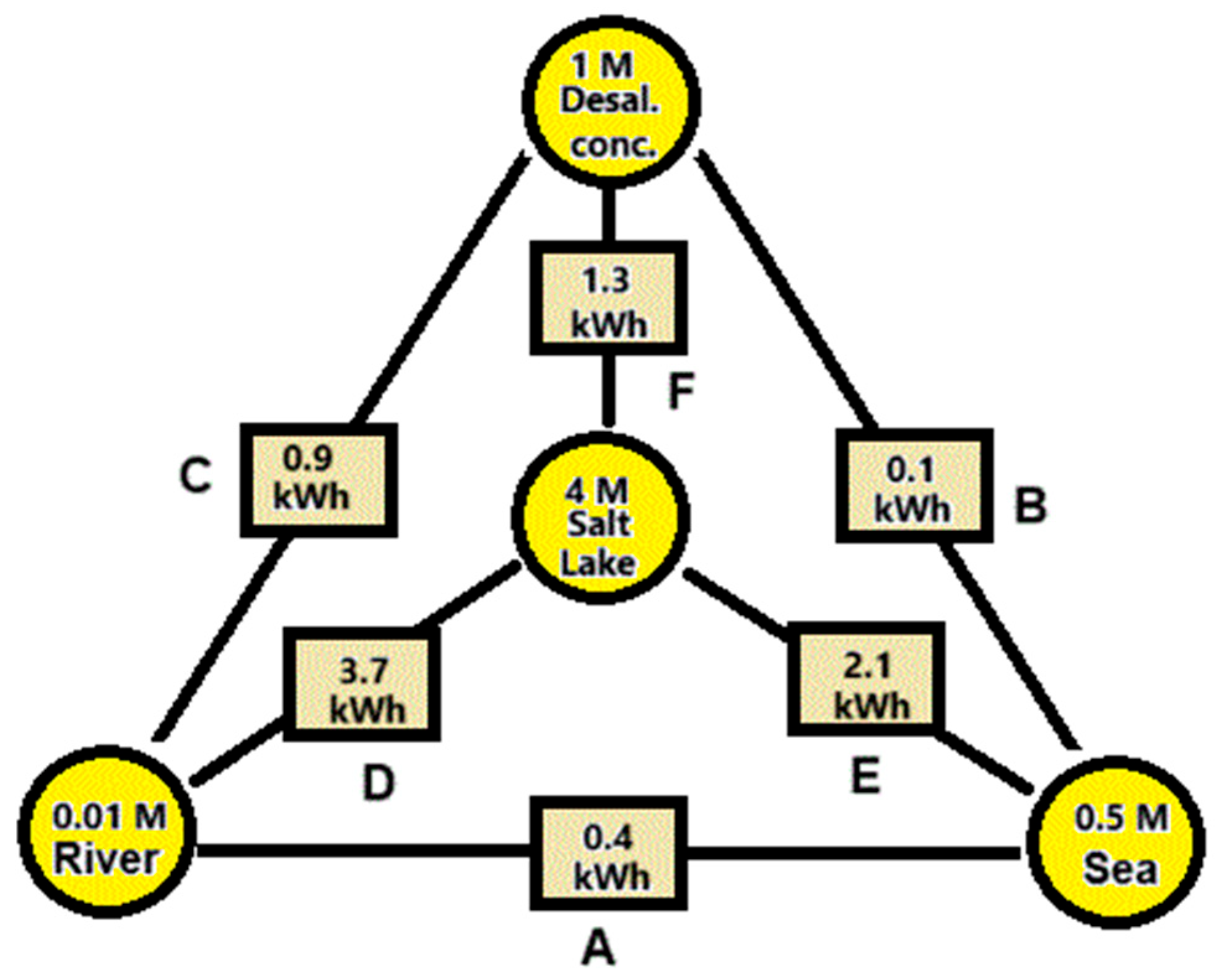

Figure 1. shows how much SGE can be harvested theoretically by reversible mixing of 1 m

3 plus 1 m

3 of these feed waters.

Based on

Figure 1, we arrive at the following feed water combinations:

A. River water + seawater. These feed waters are most abundant. SGE generated with this combination is known as Blue Energy. The Dutch company REDstack is developing SGE using the reverse electrodialysis (RED) technology for economic deployment [

3].

B. Sea water + desalination concentrate. Most reverse osmosis (RO) systems operate with a recovery rate of about 50% which results in a concentrate having twice the salinity of seawater, about 1 M [

4]. The energy content of this combination is 4 times smaller than combination A and is therefore not very attractive. However, in contrast to RO systems, the recovery of thermal desalination plants is much higher and the concentrate may be in the order of 3 M. Moreover, this concentrate is relatively hot and in this case the generation of SGE with seawater is a good option [

5].

C. River water + desalination concentrate. Desalination plants are placed in dry areas where there are usually no rivers. However, municipal waste water from the neighboring city, which also has a low salt content, may be available to generate SGE in combination with desalination concentrate [

6].

D. River water + salt lake. If the water from a salt lake together with the inflow river is used, no net change of the salinity conditions in the lake occur. If the lake has no outflow – known as an endorheic basin – the salinity can be very high. An example is the Great Salt Lake in the USA [

7].

E. Seawater + salt lake. The Dead Sea is drying up and the reason is that more and more water is being extracted from the inflowing Jordan river. Ideas have been put forward to raise the water level again by supplying water from the Mediterranean Sea or from the Red Sea. Because the Dead Sea is 400 meters below the sea level, energy can in principle also be generated with a hydroelectric power station. In addition, there is the possibility of using the difference in salinity for SGE. The latter was first proposed by Sydney Loeb and later further elaborated by others [

8].

F. Salt lake + desalination concentrate. This combination is not very realistic and is included here only for completeness.

2. Methods of SGE, a Brief History and the Ideas That Follow from It

There are three basic methods to generate SGE: diffusion of ions, of liquid water, and of water vapor.

2.1. Diffusion of Ions

When using the diffusion of ions, in most cases ion exchange membranes (IEM)s are applied. There are two types: anion exchange membranes (AEMs) mainly allow anions to pass through and cation exchange membranes (CEMs) mainly cations. In addition, there is also a technique that does not require a membrane, the so-called external charged capacitive mixing.

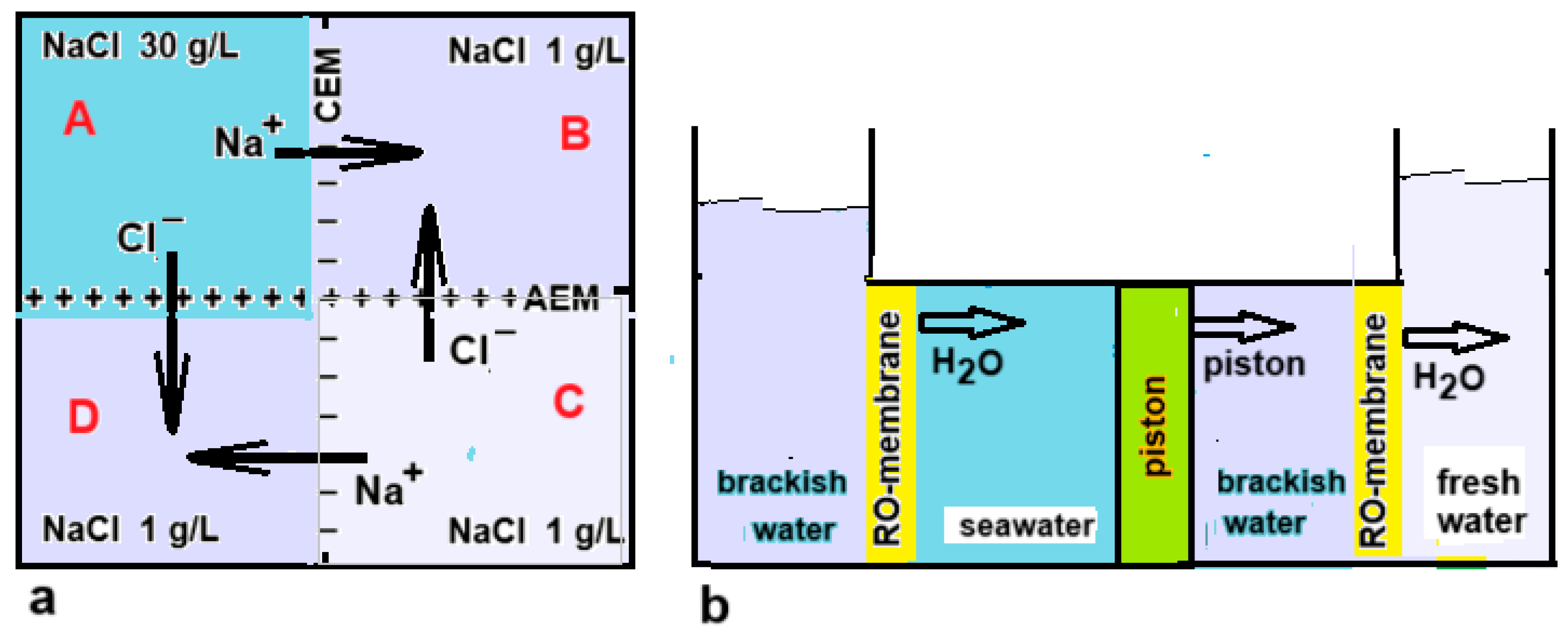

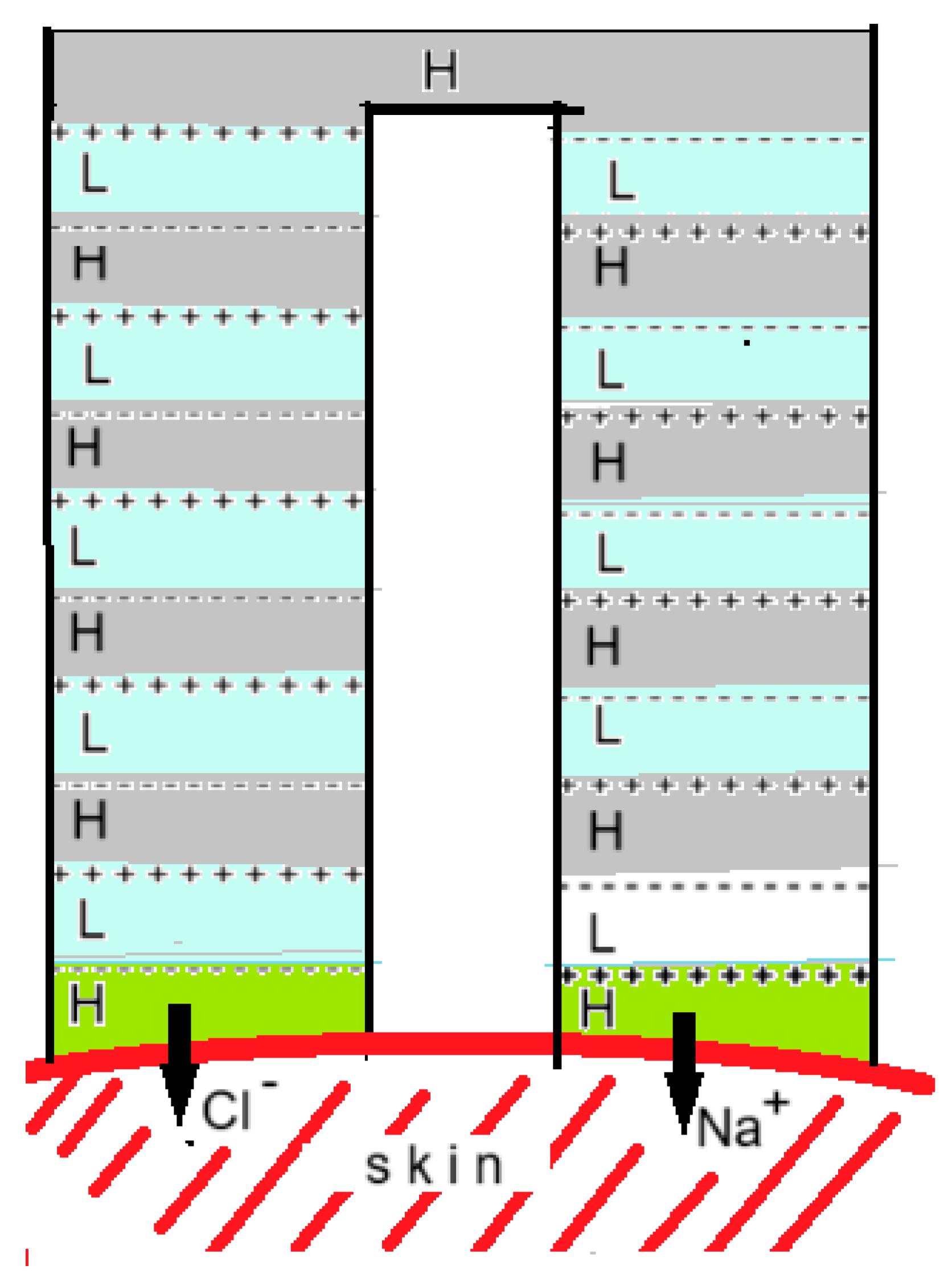

2.1.1. Reverse Electrodialysis (RED)

In 1942 Manecke published an article called Membranakkumulator [

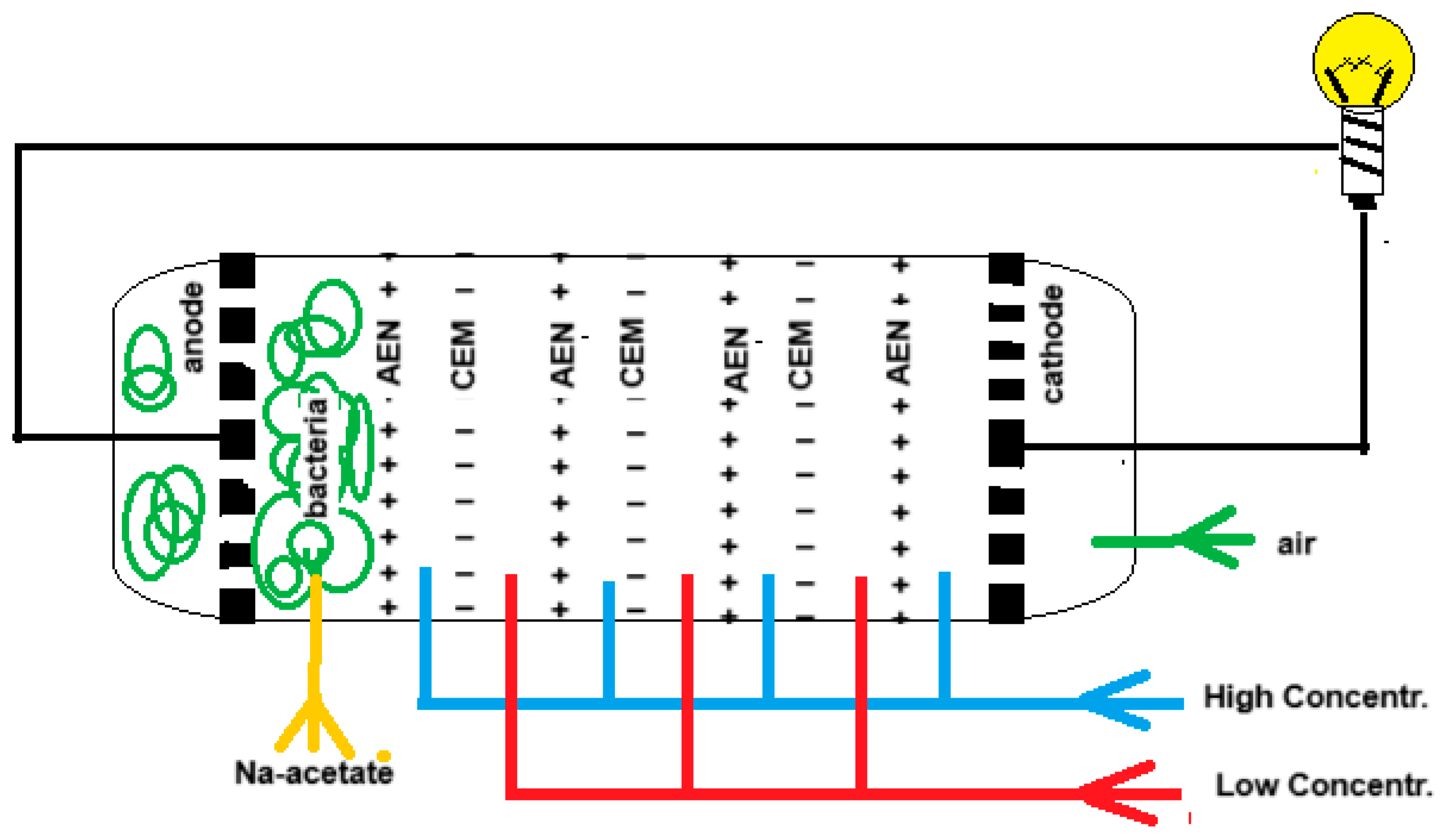

9]. At that time electrodialysis (ED) was already a well-known technique, but Manecke came up with the idea of using ED in a battery. By passing an electric current through a KCl solution, a solution with low concentration (LC) and one with high concentration (HC) were created. After loading the battery in this way, he reversed the ED process and then electricity was generated, a technique that is now known as reverse electrodialysis (RED). In 1954 Pattle picked up this idea again and improved the RED stack. Especially his vision that RED can be an energy source if seawater together with river water are used, was a novelty. The principle of RED is shown in

Figure 2.

RED can be performed with four different electrode systems. These include systems with (i) participating electrodes, (ii) inert electrodes with evolvement of gasses (H

2 and Cl

2 or O

2), (iii) inert electrodes with a redox couple, and (iv) capacitive electrodes [

10]. In addition, there are some applications that do not require electrodes.

(i). Participating electrodes undergo chemical reactions. In 1976, Clampitt and Kiviat suggested to harvest SGE with a so called ‘concentration cell’: a device with two compartments separated by a anion exchange membrane (AEM) and equipped with Ag/AgCl electrodes. The generated EMF is due to the difference of the electrode potentials and the membrane potential; both generate about the same voltage. This principle is still widely used today in the field of nanofluidic membranes where most newly developed membranes are of the CEM type with very promising specifications. However, because there is no AEM counterpart, testing for usability in RED involves very simple systems: a cell with two Ag/AgCl electrodes with only one CEM in between.

A new development are the battery electrodes that are mainly used in Battery Electrode Deionization (BDI), a desalination technique that is closely related to capacitive ionization (CDI) [

11]. The difference is that BDI uses battery electrodes and CDI uses activated carbon (AC). Battery electrodes (often based on the multivalence of transition metals) can specifically accept or release one specific type of ion, in contrast to AC which can exchange both anions and cations. Battery electrodes have been described for use in various forms of energy storage but not yet for RED [

12,

13].

(ii). If the system uses only NaCl solutions in the electrode compartments, gasses are formed such as H2 and Cl2 or O2. For these chemical reactions, a part of the generated energy is used. Moreover H2 is explosive and Cl2 toxic whereas at the cathode, OH¯ ions are formed and can be the cause of scaling on the electrode if calcium or magnesium ions are present.

(iii). Systems with inert electrodes use an electrode rinse solution (ERS) with a redox couple and a bulk salt for good electrical conductivity. Most used are the iron ion couple (Fe2+/Fe3+) and the hexacyanoferrate couple ([Fe(CN)6]3¯/[Fe(CN)6]4¯). There are no net chemical reactions and the power losses are relatively small.

(iv). The fourth possibility is using capacitive electrodes. Vermaas et al. used activated carbon (AC) for this purpose [

14]. In one electrode anions are adsorbed and in the other cations. When the electrodes are saturated, the process can be inverted by switching the feed water inflows. Wu et al. used the CRED technique with a single membrane to study the membrane performance [

15]. Feed water switch always introduces dead times during the feed water changes. A theoretical opportunity (but almost impossible in practice) is changing the solid carbon electrodes periodically. A more practical implementation of this idea is to pump a slurry of AC around the inert electrodes; a method investigated by Simões et al. [

16].

(v). Murphy used a RED system to drive a ED system for desalination and called it Osmotic Demineralization [

17]. Both systems are direct coupled and electrodes are not needed. A similar concept with only four compartments was studied by Veerman as shown in Figure 12a [

18]. Another application of electrodeless RED is powering transdermal drug delivery. Patches loaded with the drug are attached to the skin and the drug is transported through the skin by the generated voltage [

19].

2.1.2. Capacitive Mixing (CapMix)

In 2009 Brogioli published a paper about an SGE generator consisting of a flow cell with only two capacitive electrodes [

20]. The cell is connected to an electrical circuit that can both supply and extract energy. The water inflow is switched regularly; during the passage of seawater the ions are directed to the electrodes by an applied voltage. If these are saturated, the inflow is switched from seawater to river water which causes a reversal of the process and a higher voltage is now generated than during the previous phase. This externally charged capacitive mixing (also known as Capacitive energy extraction based on Double Layer Expansion, CDLE) triggered other researchers to improve this concept. In 2010 Sales connected an AEM to one electrode and a CEM to the other [

21]. An external energy source was no longer needed and Autogenerative Capacitive Mixing (also known as Capacitive energy extraction based on Donnan Potentials, CDP) was born. Later developments were the replacement of the capacitive electrodes by battery electrodes. These provide a larger capacity and therefore a feedwater switch was needed less frequently which is advantageous because during this switch the system is out of operation.

2.1.3. Microbial Reverse Electrodialysis

“Blue energy meets green energy in microbial reverse electrodialysis cells" is the beginning of the title of the recent review by Pandit et al. [

22]. The combination of both techniques in a single device was launched by Younggy Kim and Bruce Logan in 2011 and is known as the ‘microbial reverse electrodialysis cell’ (MRC) [

23].

Figure 3 shows the principle of an MRC. The electrode compartments of a classic RED stack are modified as follows: air is injected into the cathode compartment while the anode is loaded with exoelectrogenic bacteria. The RED part is fed with salt and fresh water while the anode space is rinsed with an acetate solution that is a model for urban waste water.

At the cathode oxygen is reduced:

H2O + ½ O2 + 2e → 2 OH-

At the anode acetate (or other organic material) is oxidized by exoelectrogenic bacteria.

2 H3C-COO- → H3C-CH3 + 2 CO2 + 2e

or total oxidation can occur:

H3C-COO- + 2 H2O → 2 CO2 + 7 H+ + 8e

The MBC can purify wastewater and supply energy. In addition, the problem of charge transfer from the ions to the electrodes is solved.

The success of the MRC has led to a number of new applications. We will mention a few. Cusick et al. showed that the MRC also works well with ammonium bicarbonate instead of NaCl [

25]. This salt is volatile, which means that the feed waters can be regenerated with heat. Due to a closed feed water system, the MRC is independent of fresh and salt water, but derives its energy from waste heat.

Zhu et al. modified the MRC on two points [

26]. They omitted the air supply to the cathode that results in hydrogen generation. Furthermore, a bipolar membrane was incorporated into the cell, which dissociated water into acid and alkali. Sequestration of the CO

2 with serpentine mineral was performed outside the cell with the help of the obtained acid and alkali.

Luo et al. added a biocathode to the MRC, which produced methane [

27]

D’Angelo et al. showed that Cr(VI) ions are reduced to less toxic Cr(III) by a MCR based Fenton process [

28] and Li et al. succeeded in abatement of azo dye polluted wastewater in a MRC [

29].

Using seawater in a RED part of a MCR leads to reduced yield due to divalent cations. This problem was solved by Jwa et al. by treating the seawater in an external microbial electrolysis cell [MEC] where these ions were precipitated as Mg(OH)

2 and CaCO

3 [

30].

2.2. Diffusion of Liquid Water

Most used technique based on diffusion of liquid water is pressure retarded osmosis where water diffuses through a membrane. Other methods are based on swelling of hydrophilic material in water.

2.2.1. Pressure Retarded Osmosis (PRO)

In 1748, Jean Antoine (Abbé) Nollet discovered the phenomenon of osmosis [

31]. Initially, osmosis was made visible using prepared pig bladders. If these are used as a semi-permeable membrane between two vessels containing solutions with different salinities, water will selectively diffuse into the vessel with the higher salt concentration (the real reason is of course that the water diffuses from the compartment with a high water concentration to the compartment with the low water concentration). If this latter vessel is sealed, a high pressure can be built up, namely 27 bar if one vessel contains seawater and the other fresh water.

This process can be reversed to desalinate seawater, but this placed high demands on the membranes. It was not until 1964 that Sidney Loeb and Srinivasa Sourirajan were able to make reverse osmosis (RO) membranes consisting of a porous support layer with a thin skin layer on top [

32]. The development of RO has been rapid and today it is the main desalination technology for the production of drinking water from seawater.

Almost ten years after the RO patent, Loeb came up with another patent: this time a method to reverse that RO process [

33]. In this way, energy can be generated by reversible mixing of fresh and salt water. Loeb called the technique 'Pressure retarded osmosis' (PRO). Almost simultaneously with Loeb's patent, Norman published a hypothetical machine for generating energy by osmosis [

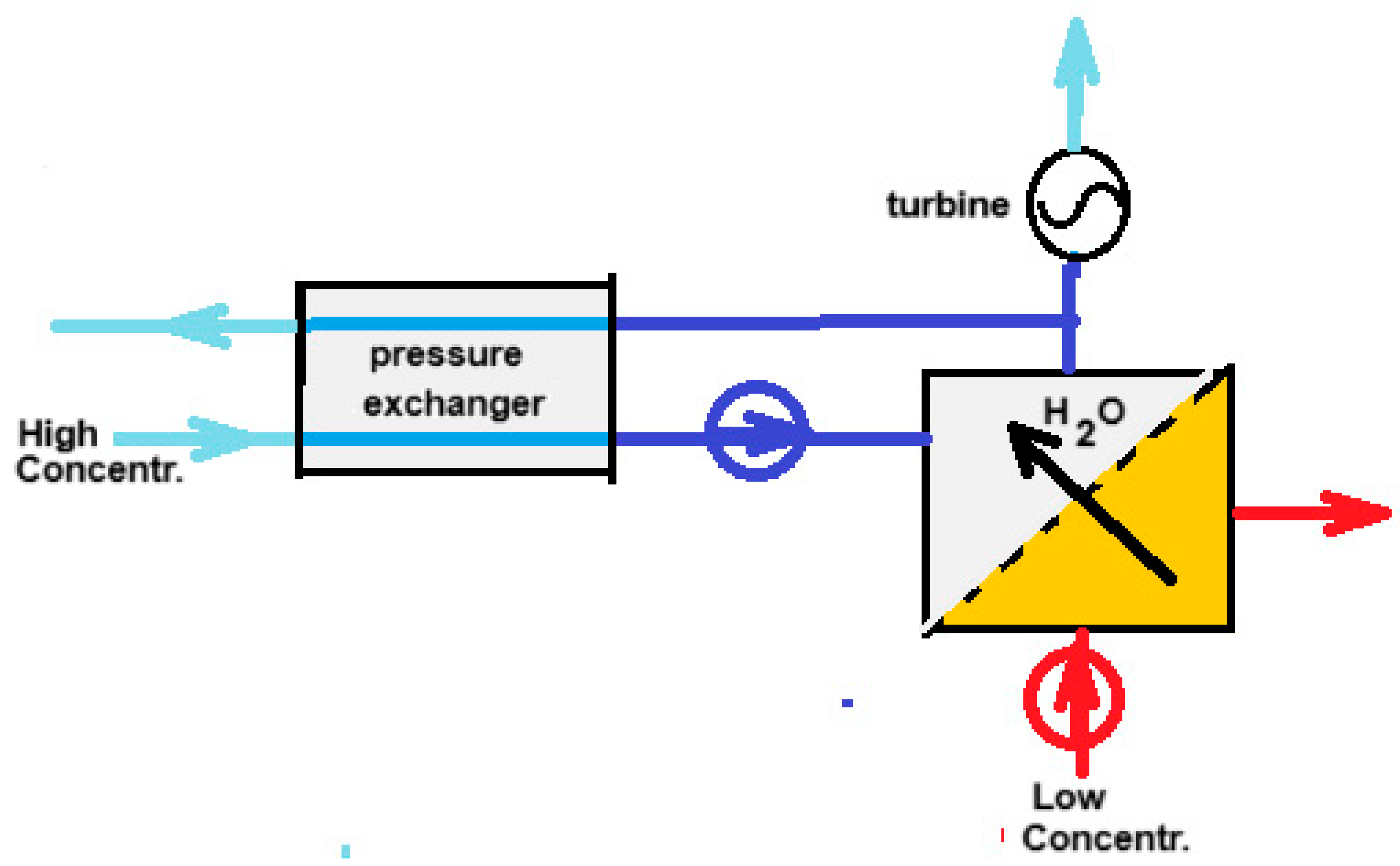

34]. From this time on, PRO took flight that was more or less parallel to the developments of RED. Nowadays PRO, together with RED are the most studied methods for SGE production. On Google Scholar "reverse electrodialysis" yields 8970 hits and "pressure retarded osmosis" 8860 hits (October 2024).The principle of PRO is shown in

Figure 4. The input of salt water to the high-pressure system requires little energy because in the pressure exchanger each liter of input is energetically compensated by each liter of output. Actually, a better name for this apparatus would be ‘volume exchanger’.

2.2.2. Swelling and Shrinking of Hydrophilic Material

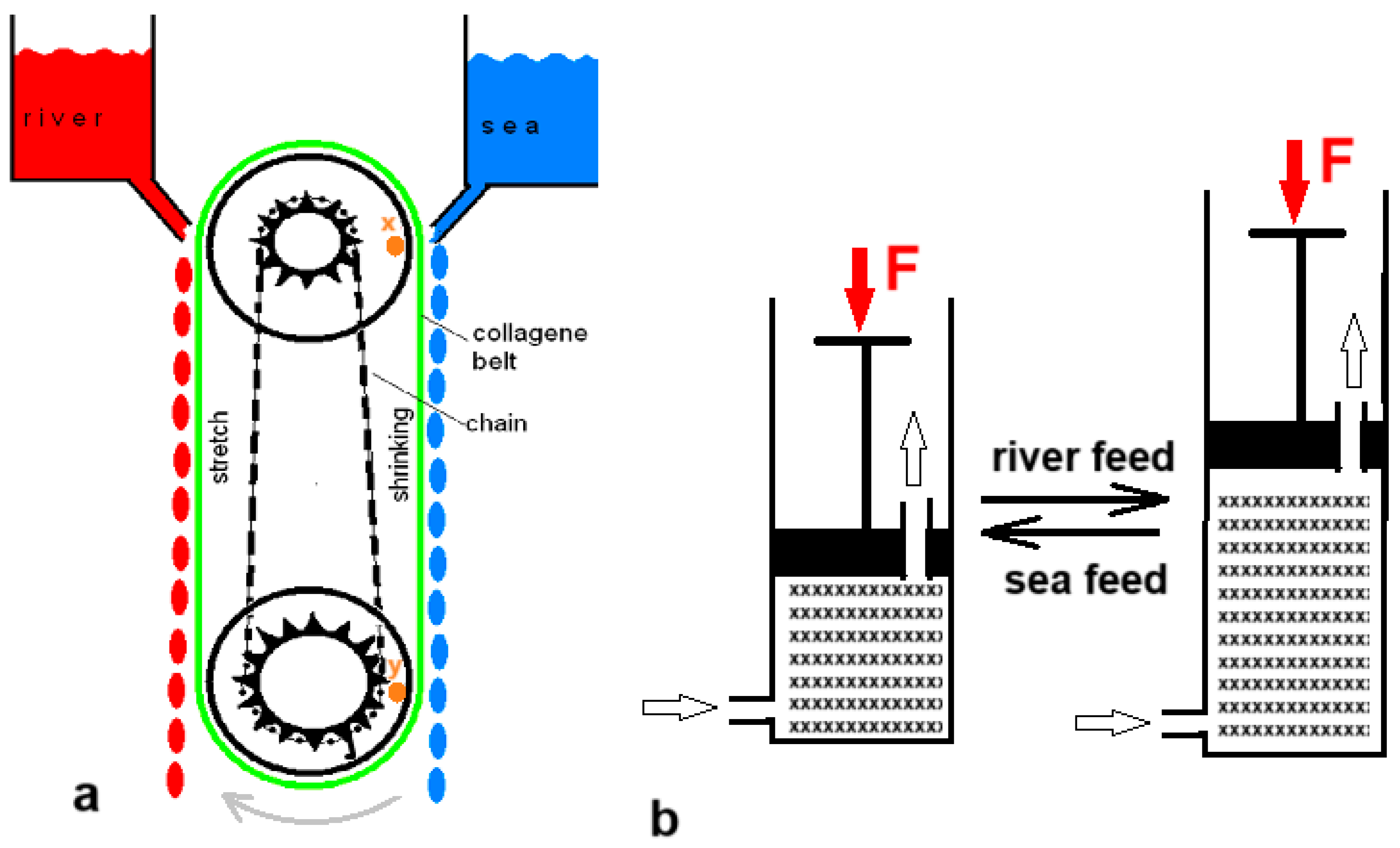

Five years before Loeb’s PRO patent, Sussman and Katchalsky published a paper titled “Mechanochemical Turbine, A new power cycle” [

35]. The authors constructed a working SGE machine based on shrinking of a crosslinked collagen cord in salt water; it returned to its original length in fresh water.

Figure 5a shows a simplified model of their generator. In 2014, Zhu et al. published a paper describing their experiments with a hydrogel in a cylinder that could push a piston away as it swelled upon contact with fresh water and shrank again upon introduction of salt water (

Figure 5b) [

36].

2.3. Diffusion of Water Vapor

In 1979, Olsson et al. published a paper entitled Salinity Gradient Power: Utilizing Vapor Pressure Differences [

37]. The method - known as VPDU - is based on the difference in vapor pressure of fresh and salt water. Water vapor will find its way from the fresh water to the salt water (

Figure 6d). The researchers tested this principle in a vacuum chamber in which a turbine was placed in the vapor stream. The heat of condensation in the salt water was returned to the fresh water via a heat exchanger, largely compensating for the huge heat of evaporation. The method has not been followed up to date.

3. Exergy of Different SGE Processes

Suppose we mix NaCl solutions of equal volume (1 L) and the same temperature (25 °C). One solution, which we will call 'river water', contains 1 g/L and the other (sea water) contains 30 g/L. If these solutions are mixed isothermally, the free enthalpy changes as follows:

If the solutions are supposed to be ideal, the change in enthalpy ∆H is equal to zero. If the solutions are also mixed reversibly, an amount of work can be harvested equal to:

∆S can be calculated as

the individual entropies can then be calculated from

The calculation is presented in

Figure 7. It follows that 1.4485 MJ is available due to the increase of entropy from ions and water. If only water is considered, this amount is a little less (1.4473 MJ). In this approach, ideality of the solutions is assumed. Post et al. corrected these values for nonideal behavior of the solutions and found that 88% of the ideal value is available in reality. [

38]. The same authors performed also batch processes with RED with two types of spacers (0.2 mm and 0.5 mm). In these experiments most of the calculated energy was harvested especially at low current densities where reversibility is best approximated.

Figure 6e shows the results and from the regression lines a recovery at extreme low current density is expected at about 85% of the available energy.

An interesting question is whether there is a difference between the different methods of SGE harvesting, namely by diffusion of ions, of liquid water or of water vapor. For this purpose we have analyzed batch processes for three representatives (RED, PRO and VDU) in which always a combination of 1 m

3 feed waters of 1 and 30 grams per liter was used exhaustively

Figure 6b,c,e. Ideal solutions were always assumed in the calculation. The results for RED (

Figure 8), PRO (

Figure 9) and VPDU (

Figure 10) lead to a great mutual agreement and are in all cases almost the same as the theoretical model that only considered the entropy of the ions (

Table 1). The agreement is surprising because the various derivations are based on very different theories: the theoretical derivation uses the increase of entropy, RED is based on Nernst's law, PRO focuses on Van 't Hoff's law, while VPDU uses Raoult's law.

4. Applications of SGE

As mentioned earlier, it was Manecke who first reported a form of SGE in his "Membrane Accumulator" in 1952, using a RED/ED stack for electricity storage. Nowadays, SGE finds applications in many areas, and in the following overview we will discuss some lesser-known applications in more detail.

4.1. Energy Generation

The largest reservoir of SGE is formed by the rivers in cooperation with the sea and it is therefore not surprising that this aspect has been studied most with regard to both to RED and PRO. However, applications at the level of pilot installations have been limited so far and the actual effort presents so many challenges that some authors consider it as impossible [

39]. We will mention two examples of PRO and two of RED on pilot scale.

- The PRO-installation of Statkraft in Tofte, Norway. The installation, which started in 2009, had a capacity of 2∙4 kW [

40]. However, the performance/price ratio was not high enough to be economically viable and the project was terminated in 2014 [

41].∙

- The use of highly concentrated salt solutions ensures that more energy can be harvested per m

2 of membrane, so that PRO can still be made possible on an industrial scale [

42]. This is the approach of the company Saltpower in Denmark. The brine is extracted by leaching from deep salt layers. The caverns thus created can then serve as storage for natural gas or hydrogen [

43,

44].

- In Trapani (Sicily, Italy) a project ran in which RED power was extracted from brackish water and brine. With artificial solutions 700 W was gained. With natural solutions from the saltworks the output power dropped to 50%, which was ascribed to the influence of multivalent ions] [

45,

46].

- In the Netherlands, a RED pilot was constructed at the closure dam between the Lake IJssel and the Wadden Sea with an infrastructure enabling the installation of 50 kW RED stacks [

3,

47,

48]. The company REDstack BV is developing the whole process technology and also the development and manufacturing of their own innovative cross flow stacks ((

Figure 11).

4.2. Desalination

SGE is based on mixing salt and fresh water and applications for desalination seems counterintuitive. However, there are two applications that can be used for desalination purposes, namely direct coupling and assisted reverse electrodialysis (ARED).

4.2.1. Direct Coupling

As previously reported, Murphy managed to desalinate water with a device based on a direct coupling between RED and ED [

17]. Direct coupling or RED and ED was also studied by Veerman [

18] and by Cheng et al. [

49]. A ring-shaped stack even makes it possible to make such a system without electrodes, as seen in

Figure 12a. Osterle and Feng have also proposed something similar for the coupling between PRO and RO [

50]. In their idea, both techniques work with pistons that are coupled to each other (

Figure 12b).

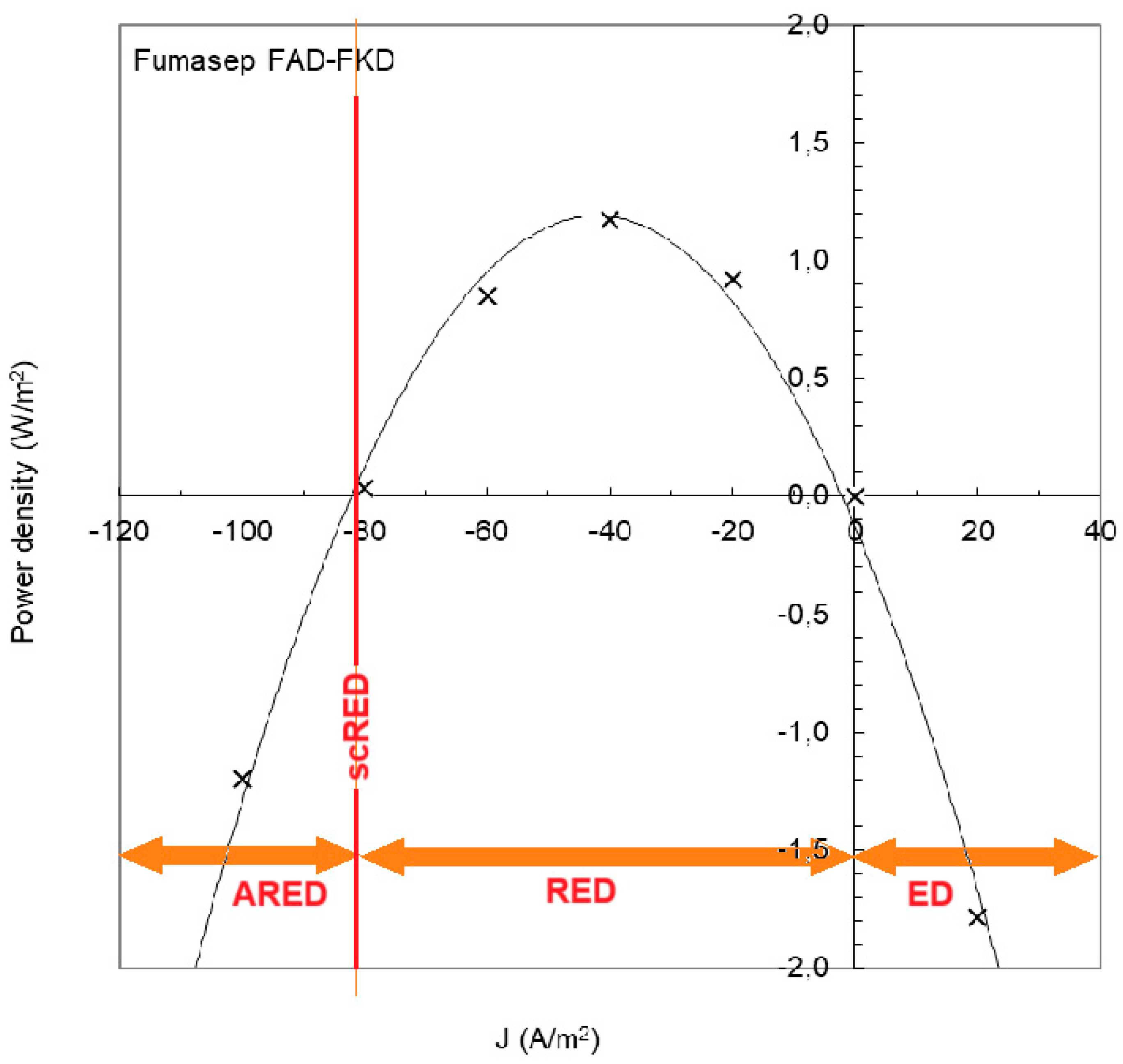

4.2.2. Assisted RED (ARED)

Figure 13 shows an experiment with a RED stack equipped with Fumasep membranes (FAD and FKD) [

51]. If the current density is below -82 A/m

2, the RED process requires the input of energy and is called ‘assisted reverse electrodialysis’ (ARED); above 0 A/m

2 normal electrodialysis (ED) occurs. With ARED, salt transport occurs from high concentration to low concentration, the same direction as in RED. Transport by ARED costs considerably less energy than ED. In the figure it is seen that ARED at -100 A/m

2 costs about the same amount of energy as ED at 20 A/m

2, therefore 5 times more mass transport takes place with ARED than with ED.

A special opportunity is scortcut RED (scRED) whereby the electrodes of the stack are short-circuited. This is the situation at – 82 A/m

2 in

Figure 13. The stack now functions as a regular dialyzer and the advantage is – apart from the energy neutrality – that no external circuitry is required [

52].

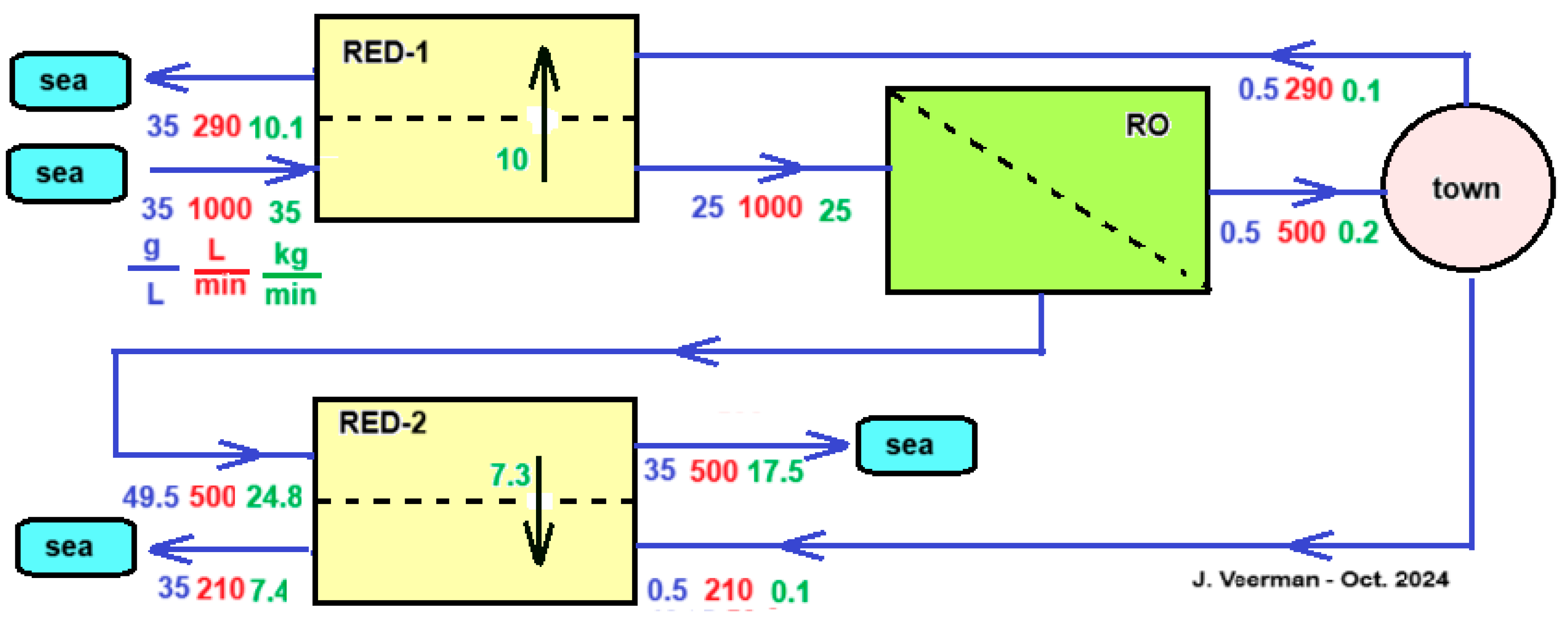

If a city located on the coast depends on a seawater RO desalination unit (SWRO) for its drinking water, then that city will also discharge a quantity of wastewater into the sea that is comparable to the production of the SWRO. This low salinity outflow of the SWRO can be used together with the inflow of the RO to feed a RED unit. This has two advantages: the RO operates with less energy due to the lower inlet concentration and, in addition, the RED unit energy.

Vanoppen et al analyzed this system and came to the conclusion that the profit of the RO part is much greater than the energy supplied by the RED [

53]. It is therefore worth considering assisting the salt transport in the RED part by an imposed voltage that thus helps the ions in the direction from high to low concentration - exactly the opposite of what is the case with ED. Although this assisted RED technology (ARED) costs energy, the profit in the RO part more than compensates for this.

Figure 14 shows a concept of an integrated system of RO, ARED and RED for the production of potable water to a town. It is simplified in some aspects: assumed is that the flow rate of the produced sewage of the town equals the consumed drinking water flow rate and the: treatment of inlet seawater and outlet sewage from the town are omitted.

As mentioned, the main function of the module RED-1 in

Figure 14. is to reduce the salt inflow into the RO section. Other options than the use of RED that are worth investigating further are to place a regular dialyzer here, equipped with an ultrafiltration, nanofiltration or mosaic membrane. Due to the salt gradient, there will be a tendency for a salt flow downwards and a water flow upwards. Both flows influence each other; with mosaic membranes there is even a chance of negative osmosis [

54,

55].

4.3. Production of Gases H2 and O2

If inert electrodes and an electrode rinse with NaCl but without a redox couple are chosen for RED, H

2 will be developed at the cathode and Cl

2 and/or O

2 at the anode [

10]. This H

2 is a marginal by-product in a stack with many cell pairs, but can also be a main product in a modified stack design. A RED stack with approximately 50 cell pairs and fed with solutions of 1 and 30 g/L yields an OCV of about 6 V in practice [

56]. while about 2-3 V is required for the electrolysis of water (1.23 V Nernst voltage and an overvoltage depending on electrode material, temperature and current density). If a similar cell is short-circuited, there will only be gas development without electricity production. Generation of H

2 and O

2 was already described by Weinstein and Leitz in 1976 [

57], however Logan et al. managed to obtain a patent on this in 2014 [

58] and various publications on the subject appeared in the years that followed. Electrolysis can occur in an external electrolyzer [

59] or on the electrodes of the RED stack [

60,

61,

62]. In addition to salinity gradients as a primary exergy source, temperature differences can also be used to drive a RED generator. Sollberg et al. described a combination of such a heat-to-power system in which the RED stack generated hydrogen using waste heat [

63].

4.4. Decomposition and Synthesis of Chemicals

In a classical RED stack (without capacitive electrodes) electrode reactions take place: oxidation at the anode and reduction at the cathode. By passing polluted water through the electrode compartments, chemicals can be rendered harmless. Examples are oxidation of Acid Orange 7 mainly to biodegradable carboxylic acids [

64] and reduction of Chromium(VI) to Cr(III) [

65]. Besides removing unwanted substances, the electrode compartments can also be used for the electrosynthesis of desired chemicals [

66].

4.5. Energy Storage

In order to tackle the climate crisis, a large-scale transition from fossil fuels to renewable sources is being made. However, the two most important ones - solar and wind - are very variable and pose major challenges for energy suppliers. Solutions are dynamic energy contracts, expansion of the network, and energy storage. The latter can be achieved by creating salinity gradients and using them for electricity generation. This can be done electric (ED with RED) or based on pressure (RO with PRO).

4.5.1. Electric Systems

Classical electric batteries have their solid or liquid electrolytes together with the electrodes in the same housing and therefore have a limited storage capacity. This in contrast to flow batteries (FB) which have their liquid electrolytes stored externally and therefore have an arbitrarily large capacity but a lower specific energy (in kWh/kg) which makes them especially suitable for stationary applications. FBs are based on redox reactions, acid-base reactions or salinity gradient energy. The vanadium redox flow battery (VRFB) is reasonably well developed and has a specific energy of approximately 20 Wh/kg.

The concentration battery is in fact the forefather of the salinity gradient energy through the work of Manecke [

9] but received renewed interest about ten years ago. The modern concentration gradient flow battery (CGFB) is essentially a combination of ED (for charging) and RED (for production). Experiments by Van Egmond et al have shown that this is possible, but the specific energy is initially rather low (0.3 Wh/kg) [

67,

68].

The latest addition to the flow battery branch is the acid-base flow battery (ABFB). The heart of this technique is a bipolar membrane in which water is dissociated during charging and the H

+ and OH

- ions recombine into water during discharging, This emerging device has a reported specific energy of 10 Wh/kg [

69] or even 17 Wh/kg [

70] and has also advantages in terms of the environment and cost price [

71]. Given the rapid developments of the ABFB, it is to be expected that the ABFB has more future then the CGFB and will become a formidable competitor for the VRFB.

4.5.2. Pressure Systems

Besides ED/RED, SGE can also be stored with RO/PRO [

72,

73]. In principle, storage and recovery can be done with the same device. To our knowledge, no real experiments have been performed so far in which a complete cycle was tested. As mentioned in section 4.5.1 the energy content of salt gradients is quite small. With electrical methods the step was made to the acid/base battery by using a bipolar membrane, but this is not possible with ED/PRO and it is questionable whether there is a future for an ED/PRO system based on salt gradients.

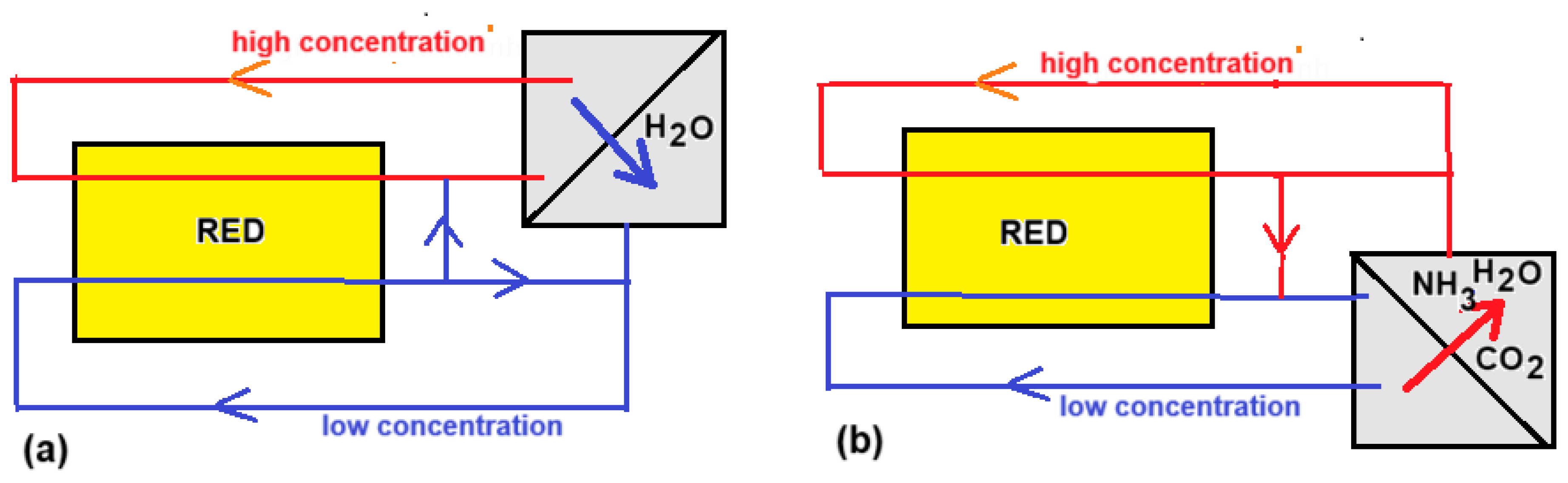

4.6. The RED Heat Engine

There are many methods to produce mechanical or electrical energy using temperature differences, e.g. with Peltier elements or with the Stirling engine. This conversion of heat to power is also possible with RED by using closed loops of feed waters that are regenerated after passing through the stack. The maximum achievable yield of all these techniques is determined by the Carnot efficiency:

where T

h is the temperature of the heat source and T

c of the heat sink (both in K). For waste heat of 100 °C together with a condenser temperature of 20 °C, this results in a Carnot efficiency of 21%. A system efficiency of 50% would be achievable with a good design, resulting in a gross efficiency of about 10% [

74]. Worldwide there is a large supply of hot waste water. Papapetrou et al. arrived at a thermal equivalent of 480 TWh/year (a mean power of 51 GW) of water of approximately 100 °C, mainly of industrial origin [

75].

In the framework of the EU project RED-Heat-to-Power (the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 640667), a consortium of 7 participants worked on the realization of a RED heat engine during the years 2015-2019 [

75]. Tamburini et al described the principle of the RED heat engine from which we summarize the main points below [

76]. The RED heat engine works with closed loops of feed waters: one with high (HC) and the other with low salt concentration (LC). After passing through the RED stack, the concentrations and flow rates are returned to the original values in a regenerator. This can be done in two ways:

(i) A volatile salt is extracted from the LC stream by heating and added to the cold HC stream. Ammonium bicarbonate or ammonium carbonate are suitable salts that decompose at elevated temperature (

Figure 15b):

NH4HCO3 ---> ...NH3 + H2O + CO2

(NH4)2CO3 ---> 2 NH3 + H2O + CO2

(ii) Water is extracted from the HC stream by distillation and added to the LC stream. The choice of salt is fairly free in this case (

Figure 15a).

The final conclusion of the project was that multiple effect distillation is the best option [

75].

4.7. Transdermal Drug Delivery

Transdermal drug delivery is the administration of medicines or other substances through the skin using prepared patches. These substances penetrate the skin through diffusion and enter the bloodstream. The process is relatively slow and the speed is strongly dependent on the molar mass, with a practical limit of 300 Da being used [

77]. By applying a voltage difference across a piece of skin, this process can be greatly accelerated, especially if the molecules have an electrical charge. With this so-called iontophoresis administering drugs with a molar mass of 13 kDa is possible.

A new development is to generate this voltage with an electrodeless RED system that is integrated into a patch. Kwon et al. described such a system in which the RED stack has an inverted U-shape and both ends lie on the skin as shown in

Figure 16 [

78]. Depending on the charge, the drug is applied to the gel layer of one of the ends. The researchers compared the uptake rate of a number of substances in this system with a classic diffusion driven gel patch and found that their RED system was much more active.

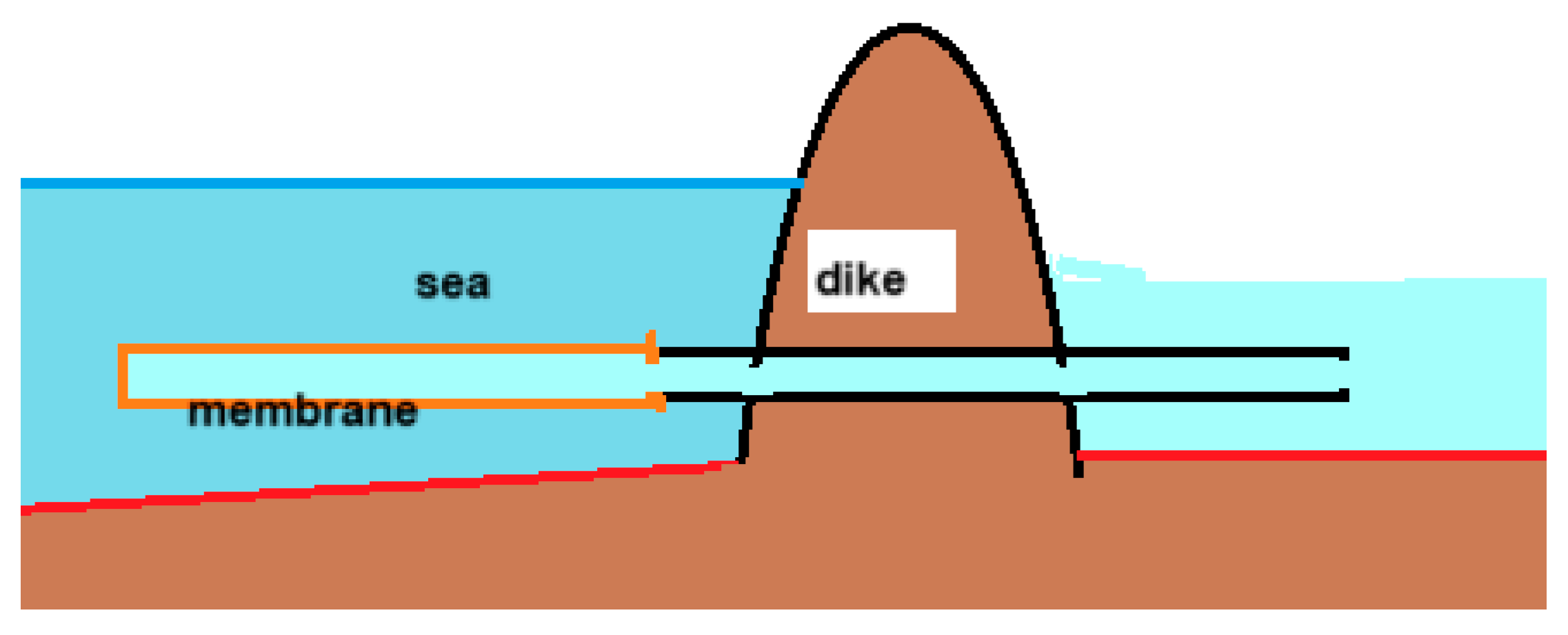

4.8. Drainage of Lowlands Near the Sea

A large part of the Dutch coastal provinces lies below sea level, with the lowest polder water level being up to 7 meters below the average sea level. Pumping stations ensure the discharge of water to the sea and require a lot of energy, which will increase in the future with the rise in sea level. The osmotic pressure of seawater is about 20 bar, which corresponds to a water column of 200 meters. By replacing the dikes with RO membranes in these conditions, dewatering could be done without energy input. Gerrit Oudakker patented this concept where the membrane was placed in the sea as shown in

Figure 17. [

79]. He mentioned also the possibility of extracting also energy from this process with a generator placed near the outlet in the sea. In fact, only a small part of the available exergy is needed to pump the water to the sea, which is why the idea arose to place the PRO generator on land as a more practical place than in the sea [

80]. Such an osmotic power plant was given the name 'osmaal’ a portmanteau of 'osmotic' and 'gemaal', the Dutch word for pumping station.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Techniques that can harvest SGE are based on diffusion of ions (mainly RED), liquid water (mainly PRO) or water vapor (VPDU). Theoretically, the available amount of extractable energy with all these techniques is the same, but in practice only RED and PRO have practical significance until now.

SGE systems can be open or closed. In an open system such as Blue Energy - the energy that is extracted from river- and seawater - the composition of the feed water is fixed and the system should be adjusted accordingly the ionic composition of the feed waters. On the other hand, in closed systems the technique dictates the choice of the salt. For energy storage systems large quantities are needed and cost price and environmental aspects are the most important factors, while the RED heat engine requires salts that are directly linked to the technique in question (salt extraction or water evaporation). In addition to salt, the feed water in open systems can also contain organic substances that can lead to membrane contamination but also offer possibilities as fuel for the microbial reverse electrodialysis cell (MRC).

The energy content of salt gradients is quite low and that means that a lot of water has to be fed through the SGP generators to achieve a reasonable energy production. This places high demands on the design because the power for pumping and pretreatment must of course be less than the delivered power. Scaling up places very high demands on the design of generators, on the entire infrastructure and on the development of affordable membranes. However, the development of RED and PRO has also led to spin-off in terms of the development of new types of membranes and therefore RED and PRO are also of significance for the two predecessors, namely ED and RO [

81].

Interesting are the developments that have led to scaling down. Examples are the RED-based transdermal drug delivery systems. Completely new are the ideas to build RED generators into the human body as an energy source for pacemakers, insulin pumps or other medical devices. Initial experiments have been done on harvesting energy from the difference in salinity of renal vein and renal artery [

82] or from the enormous differences in pH between stomach wall (pH=7.5) and stomach juice (pH=1.5) [

83].

To conclude the outlook in this article, also a look back. Earlier we said that SGE started in 1952 with the experiments of Manecke, but we actually have to adjust this idea. Japanese researchers have recently demonstrated that the process of SGE also plays a role in the walls of the chimneys on deep sea submarine vents [

84]. These contain pores that selectively allow Na

+, K

+, H

+ and Cl

- to pass through. The potential differences generated by this on the outside then ensure the transport of larger divalent ions towards the wall, where they precipitate. Closed nanopores are created inside the walls and these may have played a role in the origin of life 3.7 billion years ago.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work was facilitated by REDstack BV in The Netherlands. REDstack BV aims to develop and market RED and the ED technology. The author would like to thank his colleagues from the REDstack company for fruitful discussions and especially Folkert van Beijma for his linguistic advices.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| ABFB |

acid base flow battery |

| AC |

activated carbon |

| AEM |

anion exchange membrane |

| ARED |

assisted RED |

| BDI |

battery electrode deionization |

| CapMix |

capacitive energy extraction by mixing feedwaters |

| CDLE |

CapMix based on double layer expansion |

| CDP |

CapMix based on Donnan Potentials |

| CGFB |

concentration gradient flow battery |

| CEM |

cation exchange membrane |

| CRED |

capacitive RED |

| CDI |

capacitive Deionization |

| ED |

electrodialysis |

| EMF |

electromotive force |

| ERS |

electrode rinse solution |

| FB |

flow battery |

| HC |

high concentration |

| IEM |

Ion exchange membrane |

| LC |

low concentration |

| MEC |

microbial electrolysis cell |

| MRC |

microbial reverse electrodialysis cell |

| OCV |

open circuit voltage |

| PRO |

pressure retarded osmosis |

| RED |

reverse electrodialysis |

| RO |

reverse osmosis |

| scRED |

shortcut RED |

| SGE |

salinity gradient energy |

| VPDU |

vapor pressure difference utilization |

| VRFB |

vanadium redox flow battery |

References

- G. L. Wick and W. R. Schmitt, "Prospects for renewable energy from sea," Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 1977, 11, 16–21.

- World Energy Outlook 2023, "International Energy Agency 2023," https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energyoutlook; accessed 10 October 2024.

- B. V. REDstack, www.redstack.nl; accessed on 10 October 2024.

- J. Schunke, G. A. Hernandez Herrera, L. Padhye en T.-A. Berry, „Energy recovery in SWRO desalination: current status and new possibilities,” Front. Sustain. Cities 2:9 (2020). [CrossRef]

- J. Li, C. Zhang, Z. Wang, H. Wang, Z. Bai and X. Kong, "Power harvesting from concentrated seawater and seawater by reverse electrodialysis," Journal of Power Sources 530 (2022) 231314. [CrossRef]

- P. Xu, T. Y. Cath, A. P. Robertson, M. Reinhard, J. O. Leckie and J. E. Drewes, "Critical review of desalination concentrate management, treatment and benefical use," Environmental Engineering Sciencce 30-8 (2013) 502-514. [CrossRef]

- S. Loeb, "One hundred and thirty benign and renewable megawatts from Great Salt Lake? The possibilities of hydroelectric power by pressure-retarded osmosis," Desalination 141 (2001) 85-91. [CrossRef]

- S. Loeb, " Energy production at the Dead Sea by pressure-retarded osmosis: challenge or chimera?," Desalination 120 (1998) 247-262. [CrossRef]

- G. Manecke, „Membranakkumulator,” Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie 201 (1952) 1-15.

- J. Veerman, M. Saakes and S. J. J. Metz, "Reverse electrodialysis: evaluation of suitable electrode systems," Journal of Applied Electrochemistry 40: (2010) 1461–1474. [CrossRef]

- Y. Jiang, A. S. I, D. Wei and H. Wang, "A review of battery materials as CDI electrodes for desalination," Water 12 (2020) 3030. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, S. Zheng, H. Tang, X. Guo, H. Xue and H. Pang, "Prussian blue and its derivatives as electrode materials for electrochemical energy storage," Energy Storage Materials. [CrossRef]

- F. Ma, Q. Li, W. T, H. Zhang and G. Wu, "Energy storage materials derived from Prussian blue analogues," Science Bulletin 62-5 (2017) 358-368. [CrossRef]

- D. A. Vermaas, S. Bajracharya, B. B. Sales and M. Saakes, "Clean energy generation using capacitive electrodes in using capacitive electrodes in reverse electrodialysis," Energy Environ. Sci., 6 (2013) 643. [CrossRef]

- N. Wu, M. Levant, Y. Brahmi, C. Tregouet and A. Colin, "Mitigating the influence of multivalent ions on power density performance in a single-membrane capacitive reverse electrodialysis cell," Scientific Reports 14 (2024)16984. [CrossRef]

- Simões, M. Saakes and D. Brilman, "Toward redox-free reverse electrodialysis with carbon-based slurry electrodes," Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 62-3 (2023). [CrossRef]

- G. W. Murphy, "Osmotic demineralization," Ind. Eng. Chem. 50 (1958) 1181-1188. [CrossRef]

- J. Veerman, „Rijnwater ontzouten hoeft geen energie te kosten,” PolyTechnisch Tijdschrift Waterbehandeling 9 (1994) 52-55.

- S.-R. Kwon, S. H. Nam, C. Y. Park, S. Baek, J. Jang, X. Che, K. S. H, Y.-R. Choi, N.-R. Park, J.-Y. Choi, Y. Lee and T. D. Chung, "Electrodeless reverse electrodialysis patches as an ionic power source for active transdermal drug delivery," Advanced Functional Materials, 28-15 (2018)1705952. [CrossRef]

- Brogioli, "Extracting renewable energy from a salinity difference using a capacitor," Physical Review Letters 103 (2009) 058501. [CrossRef]

- B. B. Sales, M. Saakes, J. W. Post, C. J. N. Buisman, M. P. Biesheuvel and H. V. M. Hamelers, "Direct power production from a water salinity difference in a membrane-modified supercapacitor flow cell," Environ. Sci. Technol. 44 (2010) 5661–5665. [CrossRef]

- S. Pandit, C. Pandit, A. S. Mathuriya and J. D. A, "Blue energy meets green energy in microbial reverse electrodialysis cells: Recent advancements and prospective," Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 57 (2023) 103260. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kim and B. E. Logan, "Microbial reverse electrodialysis cells for synergistically enhanced power production," Environ. Sci. Technol. 45 (2011) 5834–5839. [CrossRef]

- V. S. S. Mosali, H. Soucie, X. Peng, E. Faegh, M. Elam, I. Street and W. E. Mustain, "Mechanistic insights into the electrochemical oxidation of acetate at noble metals," Chem Catalysis, (2024) 1011090. [CrossRef]

- R. D. Cusick, Y. Kim and B. E. Logan, "Energy capture from thermolytic solutions in microbial reverse-electrodialysis cells," Science 335 (2012) 1474. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhu, M. C. Hatzell and B. E. Logan, "Microbial reverse electrodialysis electrolysis and chemical production cell for H2 production and CO2 sequestration," Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 1 (2014) 231−235. [CrossRef]

- X. Luo, F. Zhang, J. Liu, X. Zhang, X. Huang and B. E. Logan, "Methane production in microbial reverse-electrodialysis methanogenesis cells (MRMCs) sing thermolytic solutions," Environ. Sci. Technol. 48 (2014) 8911−8918. [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, A. Galia and O. Scialdone, "Cathodic abatement of Cr(VI) in water by microbial reverse-electrodialysis cells," Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 748 (2015) 40-46. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, X. Jin, N. Zhao, I. Angelidaki and Y. N. Zhang, "Novel bio-electro-Fenton technology for azo dye wastewater treatment using microbial reverse-electrodialysis electrolysis cell," Bioresource Technology 228 (2017) 322-329 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Jwa, Y.-M. Yun, H. Kim, N. Jeong, K. S. Hwang, S. Yang en J.-Y. Nam, „Energy-efficient seawater softening and power generation using a microbial electrolysis cell-reverse electrodialysis hybrid system,” Chemical Engineering Journal Volume 391 (2020) 123480. [CrossRef]

- Nollet, J A , "Investigations on the causes for the ebullition of liquids," Journal of Membrane Science 100 (1995) 1-3. [CrossRef]

- S. Loeb and S. Sourirajan, "High flow membrane for separation water from saline solutions," USA patent US3.133.132A (1964).

- S. Loeb, "Method and apparatus for generating power utilizing pressure retarded osmosis," Patent US3906250A (1975).

- R. S. Norman, "Water salination: a source of energy," Sience 186 (1974) 350-352. [CrossRef]

- M. V. Sussman en A. Katchalsky, „Mechanochemical turbine: A new power cycle,” Science, New Series, Vol. 167, No. 3914 (Jan. 2, 1970), pp. 45-47.

- X. Zhu, W. Yang, M. C. Hatzell and B. E. Logan, "Energy recovery from solutions with different salinities based on swelling and shrinking of hydrogels," Environmental Science & Technology 48.12 (2014) 7157-7163. [CrossRef]

- M. Olsson, G. L. Wick and J. D. Isaacs, "Salinity gradient power - Utilizing vapor-pressure-differences," Science 206 (1979) 452-454. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Post, H. V. M. Hamelers and C. J. N. Buisman, "Energy recovery from controlled mixing salt and fresh water with a reverse electrodialysis system," Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5785–5790. [CrossRef]

- S. Lin, Z. Wang, L. Wang and M. Elimelech, "Salinity gradient energy is not a competitive source of renewable energy," Joule (2023). [CrossRef]

- S. Patel, "Statkraft shelves osmotic power project," Power - News & technology for the global energy industry - (2014) ; https://www.powermag.com/statkraft-shelves-osmotic-power-project; accessed 3 December 2024.

- ForwardOsmosisTech, "Statkraft bids farewell to ambitious osmotic power project," https://web.archive.org/web/20170118220928/http://www.forwardosmosistech.com/statkraft-discontinues-investments-in-pressure-retarded-osmosis/ ; accessed 3 December 2024.

- H. T. Madsen, S. Søndergaard Nissen and E. G. Søgaard, "Theoretical framework for energy analysis of hypersaline pressure retarded osmosis," Chemical Engineering Science 139, (2016) 211-220. [CrossRef]

- J. Culmsee, L. S. Pedersen and H. Guo, "Worlds first osmotic energy plant for solution mining in operation," Solution Mining Research Institute Fall 2023 Technical Conference, San Antonio, Texas, USA 2-3 October 2023; https://www.saltpower.net/media/1243/2023-smri-jce.pdf; accessed 3 Dember 2024.

- J. Quintal, M. F. Bindseil, T. Nakao, S. Hirata, M. Overgaard, K. Thorøe, J. Culmsee, L. S. Pedersen and H. Guo, "Full scale demonstration of osmotic power in high salinity," power.net/media/1241/2021-euromembrane-2021-abstract-hgo.pdf; visited 3 December 2024.

- M. Tedesco, A. Cipollina, A. Tamburini and G. Micale, "Towards 1kW power production in a reverse electrodialysis pilot plant with saline waters and concentrated brines," Journal of Membrane Science 522 ((2017) 226-236. [CrossRef]

- M. Tedesco, C. Scalici, D. Vaccari, A. Cipollina, A. Tamburini and G. Micale, "Performance of the first reverse electrodialysis pilot plant for power production from saline waters and concentrated brines," Journal of Membrane Science 500 (2016) 33–45. [CrossRef]

- IRENA, "Salinity gradient energy - Technology brief," https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2014/Jun/Salinity_Energy_v4_WEB.pdf - accessed 2 December 2024.

- J. Veerman, P. Hack, R. Siebers and M. van Oostrom, "Blue energy from salinity gradients," The Journal of Ocean Technology,18-1 (2023) 26-36 .

- Q. Chen, Y.-Y. Liu, C. Xue, Y.-L. Yang and W.-M. Zhang, "Energy self-sufficient desalination stack as a potential fresh water supply on small islands," Desalination 359 (2015) 52058. [CrossRef]

- J. Osterle and W. W. Feng, "Self-energized osmotic desalination," Mechanical Engineering 97-4 (1975) 58.

- J. Veerman, R. M. de Jong, M. Saakes, S. J. Metz and G. J. Harmsen, "Reverse electrodialysis: Comparison of six commercial membrane pairs on the thermodynamic efficiency and power density,," Journal of Membrane Science, 343 (2009) 7-15. [CrossRef]

- L. Gurreri, M. La Cerva, J. Moreno, B. Goossens, A. Trunz and A. Tamburini, Coupling of electromembrane processes with reverse osmosis for seawater desalination: Pilot plant demonstration and testing, Desalination 526 (2022) 115541. [CrossRef]

- M. Vanoppen, E. Criel, G. Walpot, D. A. Vermaas and A. Verliefde, "Assisted reverse electrodialysis—principles, mechanisms, and potential," npj Clean Water (2018) 1:9 . [CrossRef]

- J. N. Weinstein and S. R. Caplan, "Charge-mosaic membranes: Enhanced permeability and negative osmosis with a symmetrical salt," Science, New Series 161-3836 (1968) 70-72. [CrossRef]

- B. H. M. Bolto and T. Tran, "Review of piezodialysis — salt removal with charge mosaic membranes," Desalination 254 (2010) 1–5. [CrossRef]

- J. Veerman, M. Saakes, S. J. Metz en G. J. Harmsen, „Reverse electrodialysis: Performance of a stack with 50 cells on the mixing of sea and river water,” Journal of Membrane Science 327 (2009) 136–144. [CrossRef]

- J. N. Weinstein and F. B. Leitz, "Electric power from differences in salinity: the dialytic battery," Science 191 (1976) 557-559. [CrossRef]

- B. E. Logan, Y. Kim, C. R. D and J. Nam, "Methods for hydrogen production," Patent US2014/0251819A1.

- R. A. Tufa, E. Rugiero, D. Chanda, J. Hnàt, W. van Baak, J. Veerman, E. Fontananova, G. Di Profi, Drioli, E, K. Bouzek and E. Curcio, "Salinity gradient power-reverse electrodialysis and alkaline polymer electrolyte water electrolysis for hydrogen production," Journal of Membrane Science 514 (2016) 155–164. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, C. Jiang, M. A. Shehzad, Y. Wang, H. Feng, Z. Yang and T. Xu, " Water dissociation assisted electrolysis for hydrogen production in a Salinity Power Cell," ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 7-15 (2019) 13023. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, C. Jiang, Y. Zhang, Y. Wang and T. Xu, "Storable hydrogen production by reverse electro-electrodialysis (REED)," Journal of Membrane Science 544 (2017) 397-405. [CrossRef]

- J.-H. Han, H. Kim, K.-S. Hwang, N. Jeong and C.-S. Kim, " Hydrogen Production from Water Electrolysis Driven by High Membrane Voltage of Reverse Electrodialysis," J. Electrochem. Sci. Technol., 2019, 10(3), 302-312. [CrossRef]

- S. B. B. Solberg, P. Zimmermann, Ø. Wilhelmsen, J. J. Lamb, R. Bock and O. S. Burheim, "Heat to hydrogen by reverse electrodialysis—Using a non-equilibrium thermodynamics model to evaluate hydrogen production concepts utilising waste heat," Energies 15 (2022) 6011. [CrossRef]

- Scialdone, A. D’Angelo and A. Galia, "Energy generation and abatement of Acid Orange 7 in reverse electrodialysis cells using salinity gradients," Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 738 (2015) 61-68. [CrossRef]

- Scialdone, A. D’Angelo, E. De Lumè and A. Galia, "Cathodic reduction of hexavalent chromium coupled with electricity generation achieved by reverse-electrodialysis processes using salinity gradients," Electrochimica Acta 137, (2014) 258-265. [CrossRef]

- 66. Scialdone, "Electrochemical synthesis of chemicals and treatment of wastewater promoted by salinity gradients using reverse electrodialysis and assisted reverse electrodialysis," Current Opinion in Electrochemistry 43 (2024): 101421. [CrossRef]

- W. J. van Egmond, M. Saakes, S. Porada, T. Meuwissen and C. J. N. Buisman, "The concentration gradient flow battery as electricity storage system: Technology potential and energy dissipation," Journal of Power Sources 325 (2016) 129-139. [CrossRef]

- W. J. van Egmond, U. K. Starke, M. Saakes, B. C. J and H. H. V. M. N, "Energy efficiency of a concentration gradient flow battery at elevated temperatures," Journal of Power Sources 340 (2017) 71-79. [CrossRef]

- Zaffora, A. Culcasi, L. Gurreri, A. Cosenza, A. Tamburini, M. Santamaria and G. Micale, "Energy harvesting by waste acid-base neutralization via bipolar membrane reverse electrodialysis," Energies 13 (2020) 5510. [CrossRef]

- R. Pärnamäe, L. Gurreri, J. Post, W. J. van Egmond, A. Culcasi, M. Saakes, J. Cen, E. Goosen, D. A. Vermaas and M. Tedesco, "The acid–base flow battery - Sustainable energy storage via reversible water dissociation with bipolar membranes," Membranes 10, (2020) 409. [CrossRef]

- M. C. Díaz-Ramírez, M. Blecua-de-Pedro, A. J. Arnal and J. Post, "Acid-base flow battery environmental and economic performance based on its potential service to renewables support," Journal of Cleaner Production 330 (2022) 129529. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Mo, A. G. Fane and Q. She, "A multifunctional desalination-osmotic energy storage (DOES) system for managing energy and water supply," Desalination 581 (2024) 117608. [CrossRef]

- K. Rao, O. R. Li, L. Wrede, S. M. Coan, G. Elias, S. Cordoba, M. Roggenberg, L. Castillo and D. M. Warsinger, "A framework for blue energy enabled storage in reverse osmosis processis," Desalination, 511 (2021) 115088. [CrossRef]

- RED-Heat-to-Power, "www.red-heat-to-power.eu; accessed 4 December 2024".

- M. Papapetrou, G. Kosmadakis, F. Giacalone, B. Ortega-Delgado, A. Cipollina, A. Tamburini and G. Micale, "Evaluation of the economic and environmental performance of low-temperature heat to power conversion using a reverse electrodialysis –multi-effect distillation system," Energies 2019, 12, 3206. [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, M. Tedesco, A. Cipollina, G. Micale, M. Ciofalo, M. Papapetrou, W. Van Baak and A. Piacentino, "Reverse electrodialysis heat engine for sustainable power production," Appl. Energy 206 (2017) 1334–1353. [CrossRef]

- H. Payne and T. L. Andrew, "Perspective: Materials and electronics gaps in transdermal drug delivery patches," ECS Sensors Plus 2024; https://mc04.manuscriptcentral.com/ecssp-ecs.

- S.-R. Kwon, S. H. Nam, C. Y. Park, S. Baek, J. Jang, X. Che, S. H. Kwak, Y.-R. Choi, N.-R. Park, J.-Y. Choi, Y. Lee and T. D. Chung, "Electrodeless Reverse Electrodialysis Patches as an Ionic Power Source for Active Transdermal Drug Delivery," Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 1705952. [CrossRef]

- Oudakker, „Waterbeheersysteem,” Dutch patent NL1019460 (2002).

- Biesboer, „Het osmaal,” De Ingenieur, 7 April 2006.

- M. N. Z. Abidin, M. M. Nasef and J. Veerman, "Towards the development of new generation of ion exchange mem-branes for reverse electrodialysis: A review," Desalination 537 (2022) 115854. [CrossRef]

- E. Pakkaner, C. Smith, C. Trexler, J. Hestekin and C. Hestekin, "Blood driven biopower cells: Acquiring energy from reverse electrodialysis using sodium concentrations from the flow of human blood.," J. Power Sources 2021, 488, 229440.

- C. Pierucci, L. Paleari, J. Baker, C. Sproncken, C. M, M. Folkesson, J. P. Wesseler, A. Vracar, A. Dodero, F. Nanni, J. A. Berrocal, M. Mayer and A. Ianiro, "Nafion membranes for power generation from physiologic ion gradients," RSC Applied Polymers (2025). [CrossRef]

- H.-E. Lee, T. Okumura, H. Ooka, K. Adachi, T. Y Hikima, K. Hirata, K. Kawano, H. Matsuura, M. Yamamoto, M. Yamamoto, A. Yamaguchi, J. E. Lee, H. Takahashi, K. T. Nam, O. D. D Hashizume, S. E. McGlynn and R. Nakamura, "Osmotic energy conversion in serpentinite-hosted deep-sea hydrothermal vents," Nature Communications (2024) 15:8193. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).