1. Introduction

Stonebrood is a very rare fungal disease of the Western honey bee

Apis mellifera, caused by various pathogen species from the genus

Aspergillus. Reports of clinically affected colonies are rare and sometimes very old [

3,

4]. As the name stonebrood suggests, the disease is regarded and, therefore, often exclusively described as a brood disease, although it also occurs in adult bees. However, since affected adult bees probably die outside the colony, their disease status is usually not recognized as such [

4,

5,

6].

As a quite rare honey bee disease, stonebrood never attracted much attention, despite the fact that it is the only zoonotic disease of honey bees [

7,

8,

9]. Hence, in the rare case of a stonebrood-diseased colony, the beekeeper is at risk of inhaling spores which might result in severe health problems. There are only very few scientific studies on stonebrood - much of the information on the pathogenesis of this disease is based on a larger study by Burnside from 1930, in which adult honey bees and larvae were experimentally infected (not under standardized conditions) [

4]. Hence, pathogenesis and etiology of stonebrood are still not fully understood [

10,

11].

It is assumed that stonebrood typically breaks out in weak colonies, and an outbreak is related to humid conditions in spring or occurs after warm summer rains [

4]. However, in most cases, the infection does not lead to the death of a colony [

4,

12]. The pathogens have been detected in clinically healthy hives, their surroundings, and the gastrointestinal tract (alimentary tract) of adult bees and bee larvae [

4,

5,

13,

14]. Oral infection by conidia [

1,

4] in pollen [

15,

16,

17,

18] is discussed as the most likely source of entry. In adult bees, entry via the hemolymph, for example, in wounds and sporadic cases via the cuticle, has also been demonstrated experimentally [

4].

Hard, mummified larvae, which give the disease its name, are characteristics of stonebrood [

1,

3,

6,

11]. While the stonebrood mummies initially look white and fluffy, the color changes depending on the

Aspergillus species involved [

1,

4,

11]. In the literature, it is described that infected and dead bee larvae were only partly removed by nurse bees, probably because, in contrast to chalkbrood, the fungal mycelium of the larvae infiltrates the cell wall, making mechanical removal more difficult for the workers [

1,

4].

The genus

Aspergillus sp. belongs to the filamentous fungi. It contains over 250

Aspergillus species currently divided into eight subgenera and 22 sections [

19].

Aspergillus species are ubiquitous in the environment and found worldwide [

5,

11,

19,

20,

21]. They spread asexually via hydrophobic, resistant, airborne spores known as conidia, produced by fruit bodies known as conidiophores (

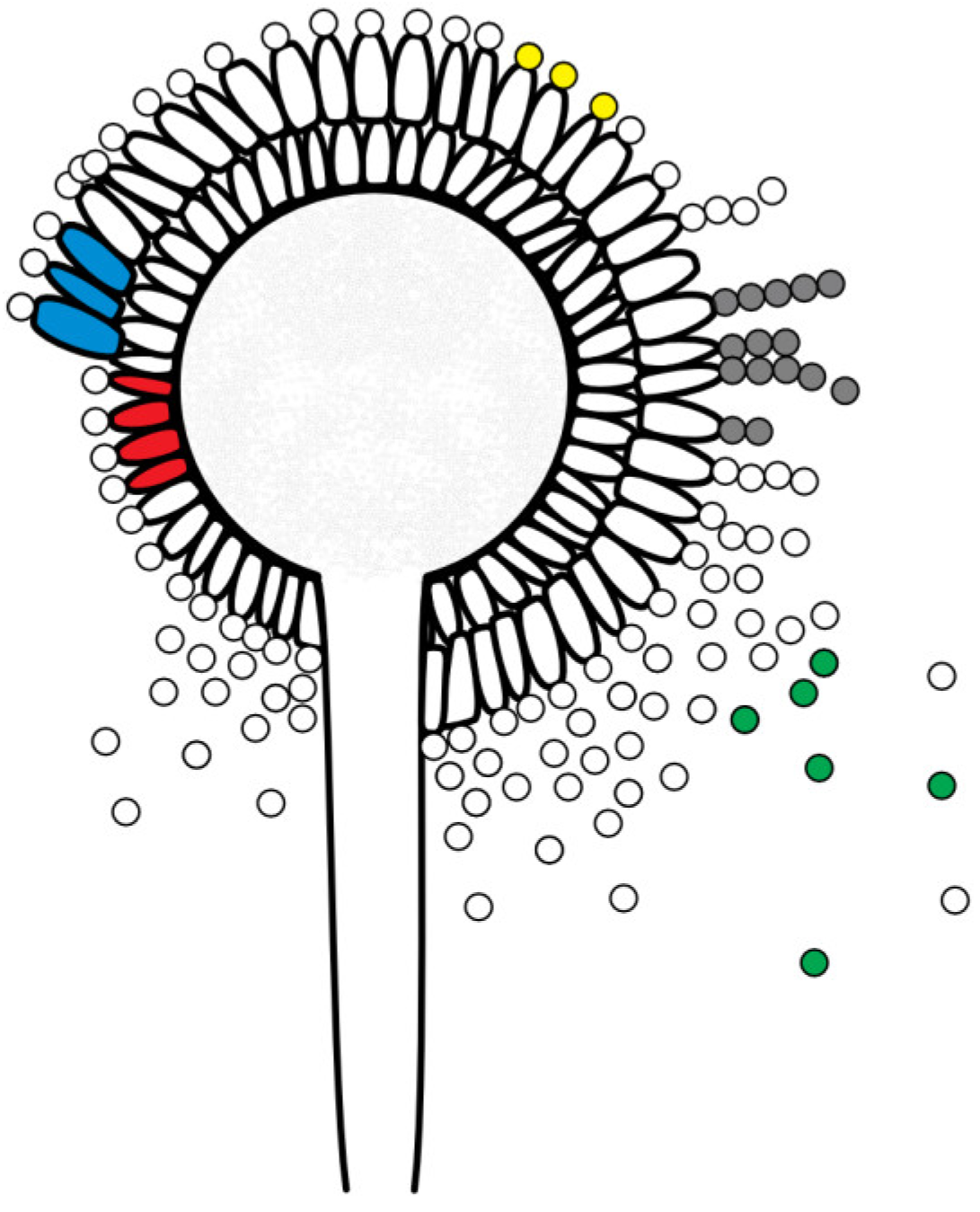

Figure 1) [

4,

5,

11,

20,

21].

Aspergillus sp. is not a bee-specific pathogen and can infect mammals, insects, birds, and plants [

7,

8,

11,

20,

21,

22,

23].

Honey bees are associated with 25

Aspergillus species, independent of the disease stonebrood, although some of their descriptions are old and, therefore, possibly outdated [

24]. Various species from the Fumigati, Flavi, and Nigri sections are responsible for the clinical picture of stonebrood [

3,

4,

5,

6,

10,

25].

Aspergillus flavus (section Flavi) is most frequently described in connection with the disease stonebrood and has the highest virulence [

3,

4,

5,

6,

10]. The two species

Aspergillus fumigatus (section Fumigati) and

Aspergillus niger (section Nigri), whose involvement in stonebrood infections are not clear, are isolated much less frequently [

3,

4,

5,

6,

10,

25]. Foley et al. were also able to isolate

A. phoenicis (section Nigri) and

A. nomius (section Flavi) and described both species as pathogenic for

A. mellifera [

5]. As molecular genetic methods for species differentiation were not available in earlier studies, it is not always clear whether the species mentioned in the literature are the species described. In 2007, for example, the species

A. niger was reclassified so that

A. brasiliensis is now listed as an independent but morphologically identical species based on molecular genetic analyses [

26].

Depending on which species are involved, the stonebrood mummies change color when conidiophores (fruiting bodies) are formed (

Figure 1) to green-yellowish if

A. flavus is the predominant pathogen, grey-greenish if

A. fumigatus is the predominant pathogen, and brown-black if

A. niger is the predominant pathogen [

1,

4,

11].

A. flavus,

A. fumigatus, and

A. niger can produce different mycotoxins [

27]. While most mycotoxins either do not cause any damage to larvae or their effect is unknown, the aflatoxin B1 produced by

A. flavus harms not only

A. mellifera but also humans [

1,

24,

28]. All three pathogens associated with stonebrood are zoonotic and can cause aspergillosis in humans [

7,

8,

9]. In addition, the pathogen

Aspergillus sp. can trigger an Extrinsic Allergic Alveolitis (EAA), also known as Hypersensitivity pneumonitis, through the inhalation of antigens [

29]. Therefore, stonebrood disease represents a health risk to beekeepers and they must be able to recognize the disease in order to take appropriate precautionary measures.

A. flavus is generally a well-described fungus. The pathogen can not only infect Western honey bees (

A. mellifera), but

A. flavus infections have also been detected in larvae of

Bombyx mori (silkworm) [

30,

31] and of the wild bee species

Tetralonia lanuginosa [

32]. In adult insects,

A. flavus infections have been detected in

Schistocerka gregaria (Desert locust) [

33], in

Blattella germanica (German cockroach) [

34], and in

Drosophila melanogaster [

35], among others.

There are large gaps in our understanding of stonebrood infections in

A. mellifera. Our pathohistological study, conducted under controlled and standardized conditions, aims at closing these gaps and providing a better understanding of pathogenesis and host-pathogen interaction. The results will be compared with existing studies, with a similar study about the chalkbrood pathogen

Ascosphaera apis and with studies about

Aspergillus flavus infections in other insect larvae [

30,

31,

32,

36].

3. Results

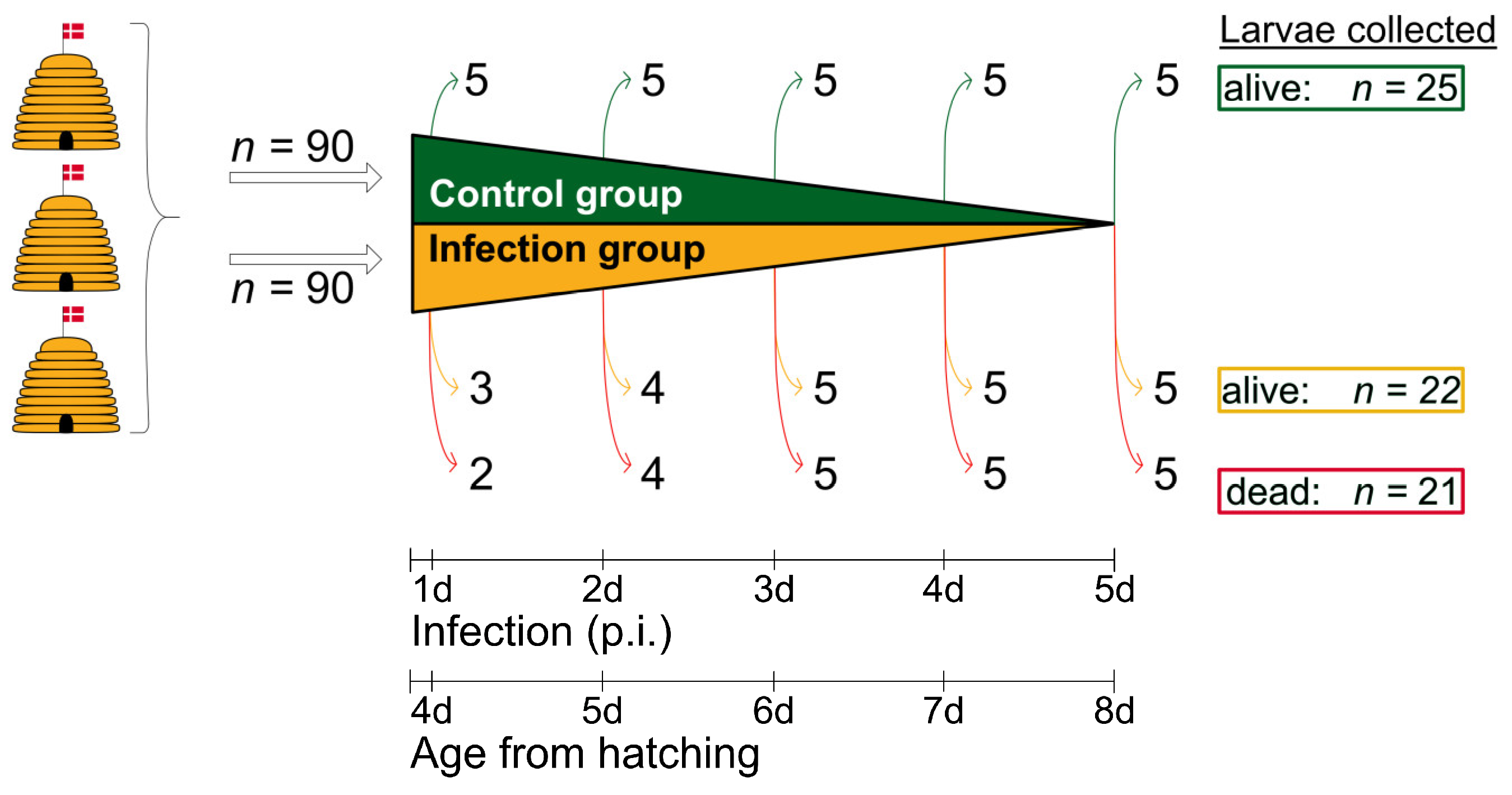

The study comprised a total of 180 larvae randomly assigned to the two experimental groups (control group and infection group). Of those, a total of 68 larvae were collected and examined macroscopically and histologically (

Figure 2). No dead larvae, but 25 live larvae were collected from the control group, all of which did not show any signs of infection, neither macroscopically nor histologically. From the infection group, 43 larvae (alive:

n = 22; dead:

n = 21) were collected (

Figure 2). Histologically, 19 of these collected larvae (live:

n = 5; dead:

n = 14) showed signs of infection with

A. flavus in the form of germinating conidia and/or fungal mycelium. In the following, these larvae are described as infected. The remaining 24 larvae from the infected group (alive:

n = 17; dead:

n = 7) were macroscopically and histologically unobtrusive indistinguishable from the larvae from the control group (see

Appendix A for measurement data), not allowing us to determine the cause of death of the seven dead larvae in the infection group. These larvae were not included in statistical analyses due to their uncertain infection status (there may be signs of infection in deeper sectional levels, or the signs of infection would have appeared later in sampling). They are referred to below as „not reliably infected“.

3.1. Macroscopic Findings in the Control and the Infection Group

The uninfected control larvae (

n = 5 x 5), all collected alive from 4 to 8 days of age, showed a substantial increase in size in the macroscopic examination up to day 5 p.i. (8 days of age) (

Figure 4A). The histological measurements (area and thickness) and statistical tests (Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn-Bonferroni tests) confirmed the increase in the size of the control larvae (

Figure 5, Appendix B). While the larvae were strongly curved initially, the curvature decreased with age (

Figure 4A). The color of the cuticle varied from opaque, dull, and ivory to translucent, shiny, and whitish (

Figure 4A). The increase in size and macroscopic changes in the control larvae correspond to recently described findings for non-infected larvae from an independent study on the pathogenesis of chalkbrood [

36].

Infected larvae (

n = 19) were present daily from day 1 p.i.. Macroscopically, the infected larvae had a very variable appearance with a tendency of being significantly smaller and looking shriveled compared to the control larvae (4 d, 5 d, 7 d p.i.) or being enlarged and bloated (6 d, 8 d p.i.) (

Figure 4B). They were slightly curved or elongated, and the tendency to elongate with increasing age (observed in the control larvae) was missing. The segmentation of the larvae was mostly indistinct. In some cases, the mycelium penetrated the cuticle and formed a sponge-like envelope around the larvae (

Figure 4B: Infection group day 4 p.i., day 5 p.i.). histological measurements (area and thickness) confirmed the macroscopically observation (

Figure 5,

Appendix A): Statistical analysis (Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn-Bonferroni tests) of the infected larvae showed significantly larger larvae only on day 5 p.i. compared to day 2 p.i. (area:

p < 0.01; thickness:

p < 0.01;

Table A2). The statistical comparison with larvae of the same age from the control group showed that infected larvae were significantly smaller on day 2 p.i. (area:

p < 0.01, thickness:

p < 0.001), day 4 p.i. (area:

p < 0.01, thickness:

p < 0.01), and day 5 p.i. (area:

p < 0.01).

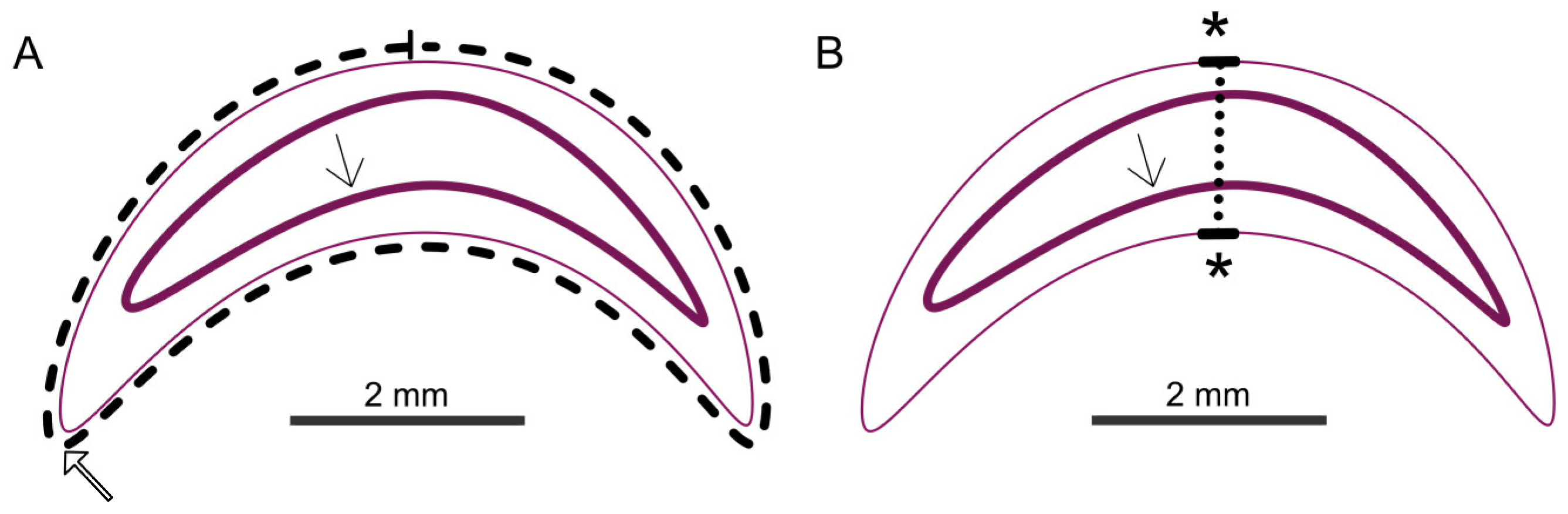

Figure 5.

Boxplots (medians, interquartile range, minimum, maximum, outliers) for the area in mm2 (A) and the thickness of the larvae in mm (B) at the collection times (1 d p.i. to 5 d p.i.). The control group (blue) and the infected larvae (red) are shown. Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney-U test. Statistical significances are represented by asterisks (*, 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05; **, 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01; ***, 0.001 > p)). The number of measurements from the control larvae (nK) and the infected larvae (ni) was specified. © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Figure 5.

Boxplots (medians, interquartile range, minimum, maximum, outliers) for the area in mm2 (A) and the thickness of the larvae in mm (B) at the collection times (1 d p.i. to 5 d p.i.). The control group (blue) and the infected larvae (red) are shown. Statistical analysis was performed using the Mann-Whitney-U test. Statistical significances are represented by asterisks (*, 0.01 < p ≤ 0.05; **, 0.001 < p ≤ 0.01; ***, 0.001 > p)). The number of measurements from the control larvae (nK) and the infected larvae (ni) was specified. © Tammo von Knoblauch.

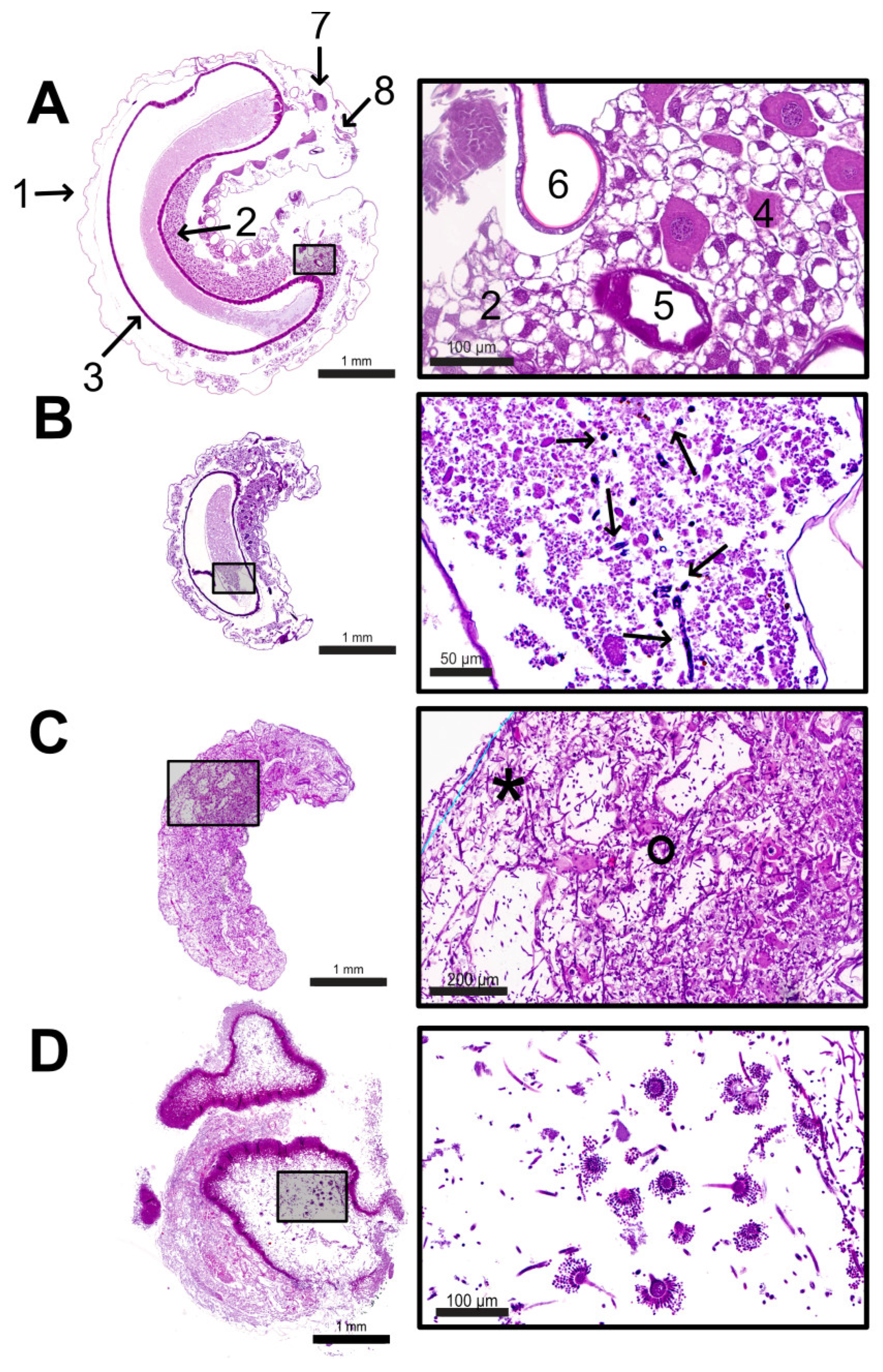

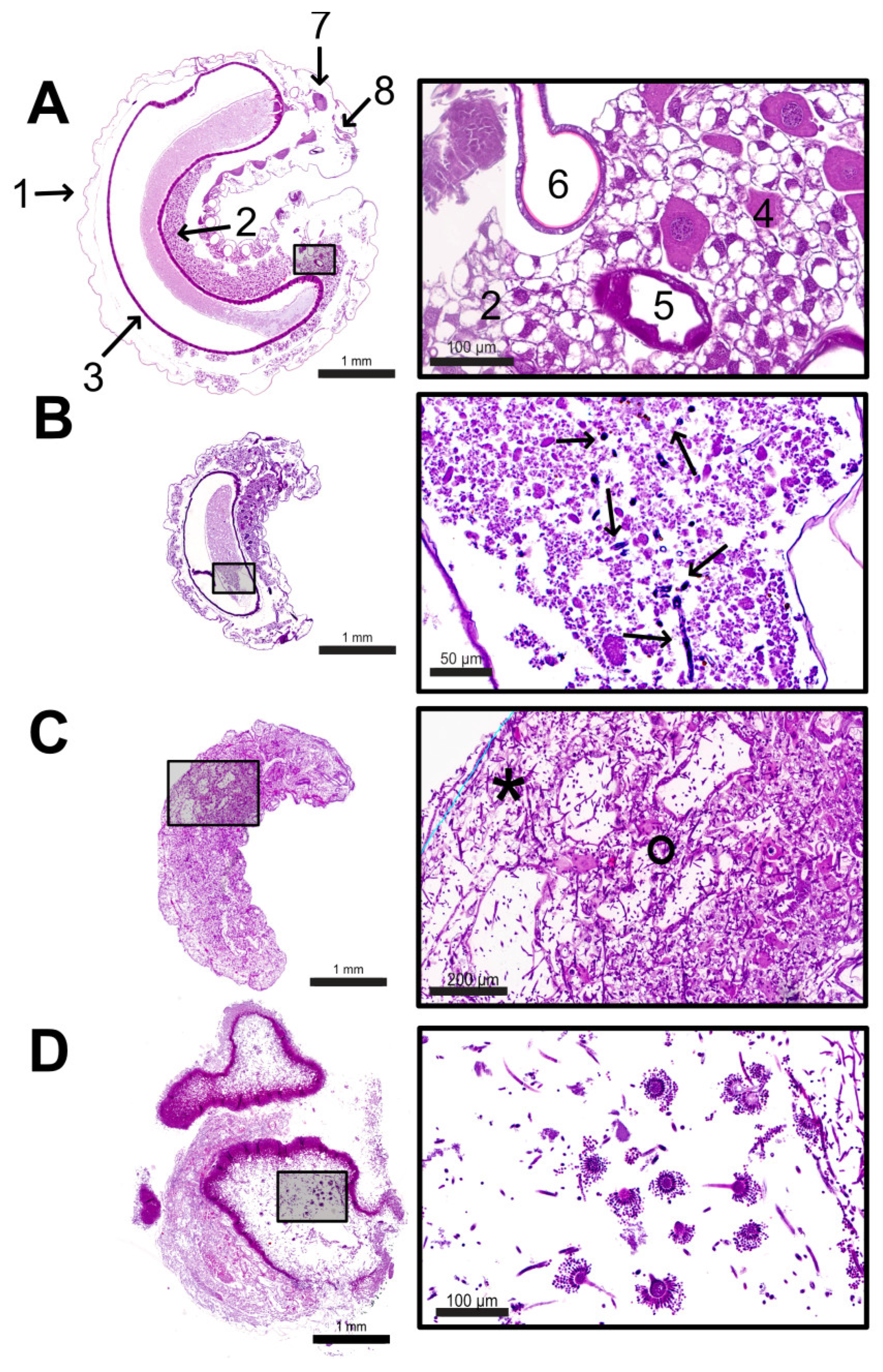

3.2. Histological Findings in the Control and the Infection Group

Our histological results from the control larvae (

n = 25) show the cuticle as the outermost layer of the larval body. Inside, lays the fat body (consisting of fat cells) with oenocytes located between the fat cells, the gut (consisting of foregut, midgut, and hindgut), and ventrally of the gut silk glands and malphigian tubules (

Figure 6A). Depending on the sectional level, the brain and other nerve cell assemblies (ganglia), the gonads, the musculature, and the tracheal system are visible (

Figure 6A). While the foregut opened into the midgut through valves (valvulae cardiacae), the hindgut was not connected to the midgut since the histological examination period ended before the onset of metamorphosis, i.e., the time point when midgut and hindgut fuse and the larvae defecate to empty the gut and prepare for metamorphosis. Due to the resulting impossibility of intestinal emptying, the midgut (depending on the section level) was mainly filled with ingesta, surrounded by the peritrophic matrix lining the midgut epithelium. These histological results correspond to recently described findings for non-infected larvae from an independent study on the pathogenesis of chalkbrood [

36].

The first infected larva was collected alive on day 1 p.i. (alive:

n = 1/3; dead:

n = 0/2,). In the histological picture, there were germinating conidia on a locally minimal area within the caudal half of the midgut, embedded in the ingesta (

Figure 6B). The conidia (purple in HE stain, black in Grocott silvering) had an average diameter of 3.5 µm (2 - 5 µm). The conidia swelled up to 6 µm in diameter at the beginning of germination. The germinating hyphae (purple in HE stain, black in Grocott silvering) were septate, still unbranched, and had an average diameter of 3.3 µm. The mycelium did not perforate the intestinal wall and was not in direct contact with the epithelium. There were no other visible deviations in the organs and tissues compared to larvae of the same age from the control group.

On day 2 p.i., all larvae collected dead (

n = 4/4), but no larvae collected alive (

n = 0/4) showed histological signs of infection. The infected larvae were completely interspersed with fungal mycelium with transverse and longitudinal sections of hyphae (

Figure 6C). The hyphae had a width between 2.5 µm and 4.8 µm. The mycelium was septate and branched. Intense destruction of organs and tissues by

A. flavus had taken place. The effects of autolytic processes were partially visible in the larval body (

Figure 6C). Tissues and organs were difficult to differentiate in these areas. In less affected areas, hyphae were mainly present in the extracellular spaces. The larvae were smaller than the larvae of the control group. The cuticle was not perforated.

On day 3 p.i., one infected living larva (n = 1/5) and two infected dead larvae (n = 2/5) were collected. In the living larva, germinating conidia were present in the cranial midgut, behind the valvulae cardiacae. The germinating conidia were concentrated in a small area. The intestinal wall was not penetrated, and no other alterations were visible compared to control larvae of the same age. In the two larvae collected dead, the mycelium had already broken through the intestinal epithelium and spread in the caudal region of the larva. There was still no mycelium in the cranial third of the two larvae, and the tissue and organs there were inconspicuous. Both larvae were smaller, as previously observed in the dead larvae on day 2 p.i.. In one larva, the highest density of the mycelium was located adjacent to the already destroyed intestinal epithelium of the caudal midgut. In the other larva, the highest density of the mycelium was much more diffusely distributed in the caudal larval body. The tissue, penetrated by the mycelium in the caudal larval body, could no longer be identified due to mechanical destruction and autolytic processes. The cuticle of both larvae was not penetrated.

On day 4 p.i., one infected living larva (

n = 1/5) and five infected dead larvae (

n = 5/5) were collected. The live larva showed germinating spores on a small area in the middle of the midgut within the ingesta. The intestinal wall was not perforated. No further alterations were apparent compared to the larvae of the control group. On the other hand, the 5 dead larvae were completely interspersed with mycelium. The cuticle was already destroyed, and the larvae were almost entirely mechanically and autolytically destroyed. In 3 of the 5 larvae, the larval contour, tissue, and organs could no longer be traced histologically. The larvae showed concentrations of the mycelium in the area of the former cuticle (

n = 4/5;

Figure 6D) or formed ring-shaped formations within the larval body (

n = 1/5). Conidiophores were developed in three of the five larvae and were mainly present ventrally outside the former larval body. The conidiophores had a diameter of 30 to 55 µm and were present with one or two rows of phialides (

Figure 1 and

Figure 6D). Ejected conidia had an average diameter of 3.5 µm (2 - 5 µm).

On day 5 p.i., two infected living (n = 2/5) and three infected dead larvae (n = 3/5) from the infection group were collected. In both living larvae, germinating conidia were present in the midgut, surrounded by ingesta. The intestinal wall of these larvae was not perforated. The germinating conidia were localized in the midgut (n = 1) and the middle of the midgut (n = 1). As previously described, no further abnormalities were observed. All larvae collected dead were completely interspersed with fungal mycelium. One of the dead larvae was smaller than the other. In another larva, only a few tissues or organs were recognizable at the cranial and caudal end of the larva. In the third larva, and only there, the cuticle was penetrated by fungal mycelium. Autolysis and mechanical destruction had already destroyed the larva. As already observed on day 4 p.i., mycelium concentrations in the area of the former cuticle and ring-shaped concentrations were also present in this larva. Conidiophores could not be observed in any larva on day 5 p.i.

The larvae reared beyond the onset of metamorphosis until day 14 p.i. showed no signs of stonebrood or any further undescribed effects suggesting that defecation is cleansing the larvae from remaining non-germinated spores or that germinating of spores is no longer possible in the pupal phase.

In summary, 44% (

n = 19) of the larvae collected from the infection group (

n = 43) showed histological signs of infection from day 1 p.i. onwards (referred to as infected). Of these larvae, 74% (

n = 14) were collected dead. The pathological findings showed an extremely aggressive course of

A. flavus growth (

Table 1): In the infected larvae collected alive, only slight signs of infection in the form of germinating conidia on a small area could be observed. In the infected larvae that were collected dead, the intestinal epithelium and at least 2/3 of the larvae were already penetrated by mycelium. In contrast, all larvae from the control group were collected alive and showed no signs of infection or other histological abnormalities.

4. Discussion

Aspergillus is a large genus of fungi that is of great importance in medicine due to the ubiquitous occurrence of (human) pathogenic species worldwide [

7,

8,

20,

21,

22,

23].

A. flavus, more rarely also

A. fumigatus or

A. niger, can infect both larvae and adults of the Western honey bee

A. mellifera and cause the clinical picture of stonebrood [

1,

4,

5,

6]. In this experimental study, larvae of

A. mellifera were orally infected with

A. flavus in order to obtain infected larvae of different age (four to eight days old bee larvae) which could be examined histopathologically to unravel the pathogenesis of larval stonebrood infection.

All larvae collected for macroscopic and histological examination (

n = 43) from the infection group were infected with a dose of 5 x 10

2 A. flavus conidia three days after egg hatching. However of those, only 19 larvae showed histological signs of infection. A possible explanation is that the conidia dose was simply insufficient to infect all larvae since the LC

100 was not determined before conducting this experiment. It is also possible that conidia or hyphae in deep section levels may have been overlooked, since only median section levels were analyzed histologically. However, several paramedian serial sections were made per larva, which were also analyzed for hyphae or germinating spores in the infection group and which did not show any signs of infection. It is possible that an infection could have developed at a later larval stage in the larvae collected alive and not showing any fungal growth. The individual immunity, genetic resistance, or effects of the microbiome may play a role in the fact that the infection did not break out [

39,

40,

41]. Even though there is no robust statement about the infection rate due to the study design, it can be assumed that the infection rate is at least 44% (

n = 19), possibly even higher.

As expected, the histological measurements of the control group show a steady increase in growth (area: p < 0.001; thickness: p < 0.001). Growth of the infected larvae is only statistically detectable between day 2 p.i. and day 5 p.i. (area: p < 0.01; thickness: p < 0.01). However, infected larvae are statistically significantly smaller than the control group on day 2 p.i. (area: p < 0.01, thickness: p < 0.001), day 4 p.i. (both: p < 0.01), and day 5 p.i. (area: p < 0.01). These results may be due to the effects of A. flavus. As food intake was not controlled in this experimental setup, the reduced growth may also be due to decreased food intake. However, no histological abnormalities associated with reduced feed intake were observed in the larvae from the infection group.

As the first infected larvae could already be collected on day 1 p.i., it is safe to state that the incubation period of

A. flavus is or can be less than 24 hours. The first dead larvae with signs of infection already appeared on day 2 p.i.. This is consistent with the experiments of Burnside, who described the death of the larvae from day 2 p.i. onwards and who wrote about the rapid spread of

A. flavus [

4]. Our study shows that the pathogenesis of

A. flavus can be divided into three phases (

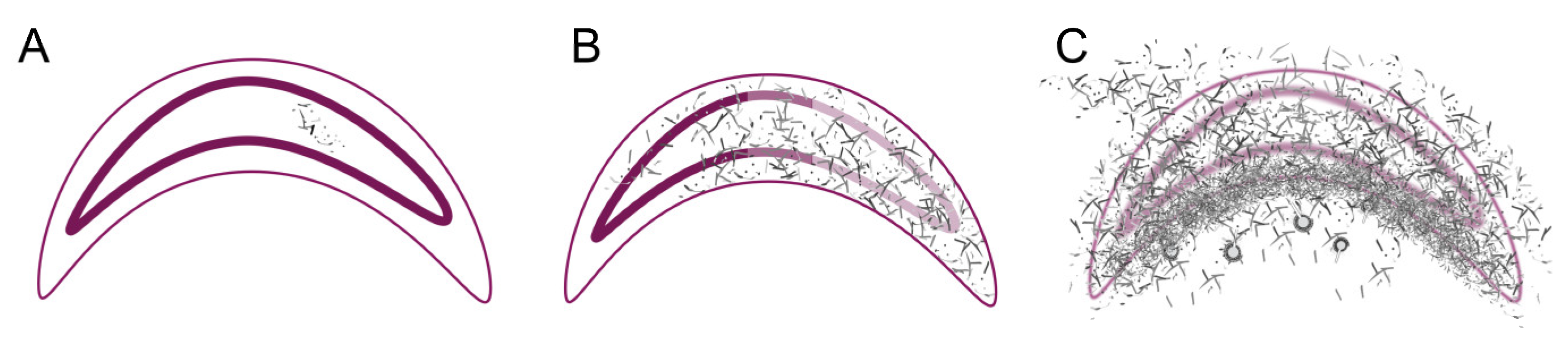

Figure 7). In the first phase (establishment phase;

Figure 7A), the fungus germinated within the intestine and was localized in a small area. All infected larvae collected alive were in this phase. In the second phase (spreading phase;

Figure 7B), the mycelium had penetrated the intestinal epithelium and spread throughout the larval body. The tissue and organs of the larvae were destroyed mainly by mechanical destruction by the mycelium and autolysis; in some cases, only fungal mycelium remained. The cuticle was not perforated. This phase was only observed in larvae that were collected as dead larvae. The last phase (distribution phase;

Figure 7C) was characterized by the penetration of the cuticle with the subsequent formation of conidiophores. All larvae belonging to this phase were already dead at the time of collection. Burnside’s experiments and our study observed that the mycelium only breaks through the cuticle after the death of the larva forming the typical stone brood mummies [

4]. As in the macroscopic changes shown here, Burnside also observed changes in appearance and texture between death and mycelial expansion outside the larval body [

4].

According to our observations, the larva dies between phase 1 and phase 2, possibly even before penetration of the intestinal epithelium, which could not be observed. This makes mechanical damage as the cause of death rather unlikely. Since

A. flavus can produce mycotoxins such as aflatoxin B1 under favorable conditions, we assume that the larvae may have died due to the toxin exposure and that the fungus then spread saprophytically [

4,

24,

28,

42,

43]. Two further studies have shown that aflatoxin can be produced in larvae and may damage bees, which could support our theory [

28,

42]. Toxin presence should be analyzed in further studies to confirm this theory.

In 33% (n = 7) of the dead larvae from the infection group, we did not observe any histological signs of infection. However, we cannot rule out that A. flavus may have developed in deeper sectional levels and produced toxins harming the larva without extensive fungal growth. This again points to the necessity to analyze A. flavus toxin production and activity in further studies.

The absence of transitional stages, the presence of phase 2 already at day 2 p.i. and cases in which the larva is completely interspersed with mycelium, at the same time, autolysis is not yet well advanced, indicated that the course of infection of

A. flavus is very fulminant and aggressive, which was confirmed in the study by Vojvodic et al. [

44].

A. flavus also appears to infect every tissue and every organ. However, it should be noted that the hyphae only spread outside the midgut after death. It was not always possible to distinguish between destruction by fungal mycelium and autolysis with subsequent mycelial growth. Burnside describes in his study that soft tissue in adult bees’ abdomen, thorax, and head is immediately attacked after death [

4]. He describes that malpighian tubules are usually not affected until the death of the bees and that the tracheae are not affected even after death due to the dry conditions and the strong tracheal wall [

4]. In our study, we did not observe any exceptions in larvae. This may also be because the organs of larvae are not yet as mechanically resistant as in adult bees. Our study clearly showed that the cuticle is only penetrated at a late stage, to be more precise, after the entire larval body has been overgrown with fungal mycelium. This step then initiates phase 3, the distribution phase, with the formation of conidiophores. The localization of the conidiophores outside the larval body or, in a few cases and the case of severely damaged larvae, also inside, close to the former cuticle, suggests that

A. flavus seeks exposed sites (exposed to the air) for optimal distribution of the conidia. Bailey has already described this [

11]. The shape of the conidiophores (single or double row with philadia up to the stalk) shows that the infection is indeed an

A. flavus infection. The third phase is, therefore, also responsible for the clinical picture of stonebrood: mummified larvae in different colors, depending on the Aspergillus species.

Aspergillus flavus appears to spread far outside the (former) larval body. This was also seen in the macroscopic images showing larvae with a thick sponge-like coating (

Figure 4: day 4 p.i., day 5 p.i.). The larger surface area and continued growth outside the larval body (without direct nutrient supply) could explain why mummified stonebrood larvae can infiltrate the brood cells and, as often described, are difficult to remove from the cells [

1]. As already observed in Burnside’s study, a pseudocuticle forms in the area of the former cuticle [

4]. The ring-shaped mycelial concentrations within the larval body are possibly responsible for the typically hard stonebrood mummies. Burnside describes that the ventriculus of infested adult bees requires considerably more pressure when pressed under a cover glass and that mycelial concentrations in digestive organs and tissues are responsible for increased firmness [

4]. We assume he described the ring-shaped mycelial concentrations within the larval body here. The third phase also represents a health risk for the beekeeper, as the spreading spores can cause aspergillosis or a hypersensitivity pneumonitis, especially in the respiratory tract [

7,

8,

9,

29]. Therefore, it is advisable to wear respiratory protection in clinically affected colonies.

A comparison with the second mycological brood disease, chalkbrood, reveals fundamental differences in the pathogenesis of the two fungal infections (

Table 2): The incubation period of

Aspergillus flavus with less than 24 h is considerably shorter than that of

Ascosphaera apis (48- 72 h) [

36]. While

Ascosphaera apis-infected larvae can still live when fungal mycelium spreads outside the midgut, this is impossible with

Aspergillus flavus-infected larvae. The death of the larvae, which is induced by mechanical damage to the tissue and organs in an

Ascosphaera apis infection, may be caused by toxin activity in an

A. flavus infection. Both

Ascosphaera apis and

Aspergillus flavus form a pseudocuticle in the area of the former cuticle, and they appear to primarily form fruiting bodies outside the former larval body [

36]. In contrast to

Aspergillus flavus, Ascosphaera apis spread much less outside the (former) larval body [

36].

A comparative analysis of literature shows that

A. flavus infections can also occur in other insect species. In one study, larvae of the wild bee species

Tetralonia lanuginosa showed mortality rates of 48%, which were associated with aflatoxin production [

32]. The silkworm

Bombyx mori can also be infected by

Aspergillus flavus (and other

Aspergillus species) [

30,

31]. In the study by Kumar et al., larvae of the silkworm

Bombyx mori were topically infected with

A. flavus on the cuticle [

30]. Although this is a different type of infection, the germination on the cuticle was observed as early as 6 h, but larval death was only observed 4-5 days after infection [

30]. The later death may be related to the fact that the cuticle is very resistant. There are no other comparable infection studies in other insects.

The results presented here do not allow any conclusions on the pathogenesis of

A. flavus infected adult honey bees and the role of other pathogens associated with stonebrood, such as

A. fumigatus and

A. niger. These must be investigated further to gain an overall understanding of the stonebrood disease. The early death of the larvae - the mycelium has not yet spread outside the midgut - presumably leads to the fact that honey bee workers can still remove the larvae, and the disease, therefore, remains undetected by the beekeeper.

A. flavus continues to spread out in a necrotrophic phase after the death of the larva and primarily forms conidiophores outside the (former) larval body, which are essential for horizontal spread. When a colony is too weak to remove the larvae in an early stage, it is probably much more difficult for the worker bees at this stage to remove the mycelium, as it infiltrates the wall of the brood cell [

1,

4].

Figure 1.

Schematic figure of an A. flavus conidiophore (fruiting body) with phialides (single-layer (uniseriate): red; double-layer (biseriate): blue), conidia (yellow), conidia chains (grey) and released conidia (green); © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Figure 1.

Schematic figure of an A. flavus conidiophore (fruiting body) with phialides (single-layer (uniseriate): red; double-layer (biseriate): blue), conidia (yellow), conidia chains (grey) and released conidia (green); © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of the experimental infection assay. Larvae (n = 180) were taken from three donor colonies headed by naturally-mated, non-sister queens and kept in an apiary near the University of Copenhagen (Denmark). Two groups were formed: one group consisting of uninfected control larvae (n = 90) and one group of infected larvae (n = 90). For macroscopic and histological examination, 25 larvae (5 x 5) were collected from the control group, and 43 larvae (22 live larvae and 21 dead larvae) were collected from the infection group. The collection of live larvae (control group and infection group) was randomized; © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of the experimental infection assay. Larvae (n = 180) were taken from three donor colonies headed by naturally-mated, non-sister queens and kept in an apiary near the University of Copenhagen (Denmark). Two groups were formed: one group consisting of uninfected control larvae (n = 90) and one group of infected larvae (n = 90). For macroscopic and histological examination, 25 larvae (5 x 5) were collected from the control group, and 43 larvae (22 live larvae and 21 dead larvae) were collected from the infection group. The collection of live larvae (control group and infection group) was randomized; © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Figure 3.

Schematic overview of the measurements (Cuticle: thin pink line; cranial mouth opening: thick open arrow in (A); intestinal epithelium: thick pink line with thin arrow). Shown in (A): area measurement (dashed line). Shown in (B): thickness measurement (dotted line); © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Figure 3.

Schematic overview of the measurements (Cuticle: thin pink line; cranial mouth opening: thick open arrow in (A); intestinal epithelium: thick pink line with thin arrow). Shown in (A): area measurement (dashed line). Shown in (B): thickness measurement (dotted line); © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Figure 4.

(A) Representative control larvae with the indication of larval age (Lx). The larvae were highly segmented, white-ivory colored with opaque to slightly translucent cuticles. They showed a loss of curvature with increasing age, reaching the largest expansion at 8 days of age (day 5 p.i.). (B) Larvae from the infection group that were found dead at the specified times (day p.i.) and collected for further analysis. Morphology and phenotype of the larvae that died at different times was highly variable, although they tended to be smaller and shrivelled (1 d, 2 d, 4 d, 5 d p.i.) compared to control larvae of the same age. On day 3 p.i., dead larvae showed the widest size range and even larvae much bigger than normal were observed (3 d p.i.). In some cases, the mycelium had broken through the cuticle and formed a spongy envelope around the larvae (d 4 p.i., d 5 p.i.); © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Figure 4.

(A) Representative control larvae with the indication of larval age (Lx). The larvae were highly segmented, white-ivory colored with opaque to slightly translucent cuticles. They showed a loss of curvature with increasing age, reaching the largest expansion at 8 days of age (day 5 p.i.). (B) Larvae from the infection group that were found dead at the specified times (day p.i.) and collected for further analysis. Morphology and phenotype of the larvae that died at different times was highly variable, although they tended to be smaller and shrivelled (1 d, 2 d, 4 d, 5 d p.i.) compared to control larvae of the same age. On day 3 p.i., dead larvae showed the widest size range and even larvae much bigger than normal were observed (3 d p.i.). In some cases, the mycelium had broken through the cuticle and formed a spongy envelope around the larvae (d 4 p.i., d 5 p.i.); © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Figure 6.

Overview images of larvae with magnifying zooms. (A) Overview and zoom of a median section of a control larva at the age of 2 days p.i.. The larva is surrounded by the cuticle (1). The larval body is filled with fat body cells (2; section A, number 2). Between the fat body cells, the midgut (3) lies centrally, consisting of a single-row intestinal epithelium. Ingesta (*) lies within the midgut. Oenocytes (section A, number 4) lie isolated between the fat body cells. Silk glands are ventral to the intestine (section A, number 5), and parts of the tracheal system are frequently visible (section A, number 6). The brain (7) and the mouth (8) are located cranially. (B) Overview and magnification (HE stain) of an infected larva at 1 d p.i., which was collected alive with signs of A. flavus infection. Germinating spores (arrows) in different stages were found in the midgut, inside the ingesta; (C) Overview and magnification (HE stain) of an infected larva at 2 d p.i collected dead with signs of A. flavus infection. The tissue is interspersed and destroyed by hyphae (°), and some areas show autolysis (*). (D) Overview and magnification (HE stain) of an infected larva at 4 d p.i. The overview image of the larva shows mycelium concentrations, mainly in the area of the destroyed cuticle. Conidiophores (fruiting bodies) of A. flavus are visible; © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Figure 6.

Overview images of larvae with magnifying zooms. (A) Overview and zoom of a median section of a control larva at the age of 2 days p.i.. The larva is surrounded by the cuticle (1). The larval body is filled with fat body cells (2; section A, number 2). Between the fat body cells, the midgut (3) lies centrally, consisting of a single-row intestinal epithelium. Ingesta (*) lies within the midgut. Oenocytes (section A, number 4) lie isolated between the fat body cells. Silk glands are ventral to the intestine (section A, number 5), and parts of the tracheal system are frequently visible (section A, number 6). The brain (7) and the mouth (8) are located cranially. (B) Overview and magnification (HE stain) of an infected larva at 1 d p.i., which was collected alive with signs of A. flavus infection. Germinating spores (arrows) in different stages were found in the midgut, inside the ingesta; (C) Overview and magnification (HE stain) of an infected larva at 2 d p.i collected dead with signs of A. flavus infection. The tissue is interspersed and destroyed by hyphae (°), and some areas show autolysis (*). (D) Overview and magnification (HE stain) of an infected larva at 4 d p.i. The overview image of the larva shows mycelium concentrations, mainly in the area of the destroyed cuticle. Conidiophores (fruiting bodies) of A. flavus are visible; © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Figure 7.

Schematic overview of the different stages of infection (Cuticle: thin pink line; intestinal epithelium: thick pink line). (A) Phase 1 - Germination and spreading of the A. flavus hyphae (grey-black) in the midgut. (B) Phase 2 - Spreading of the A. flavus hyphae (grey-black) within the larval body of the dead larva (C) Phase 3 - Penetration of the cuticle with the formation of conidiophores (balls); © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Figure 7.

Schematic overview of the different stages of infection (Cuticle: thin pink line; intestinal epithelium: thick pink line). (A) Phase 1 - Germination and spreading of the A. flavus hyphae (grey-black) in the midgut. (B) Phase 2 - Spreading of the A. flavus hyphae (grey-black) within the larval body of the dead larva (C) Phase 3 - Penetration of the cuticle with the formation of conidiophores (balls); © Tammo von Knoblauch.

Table 1.

Overview of the most important histological characteristics of infected larvae at the individual time points.

Table 1.

Overview of the most important histological characteristics of infected larvae at the individual time points.

| |

1 d p.i. |

2 d p.i. |

3 d p.i. |

4 d p.i. |

5 d p.i. |

| |

larvae alive (n = 5) |

| mycelium localization |

midgut |

- |

midgut |

midgut |

midgut |

| (n = 1/1) |

|

(n = 1/1) |

(n = 1/1) |

(n = 2/2) |

| |

dead larvae (n = 14) |

| mycelium localization |

- |

complete larval body |

Caudal part of larval body |

complete larval body |

complete larval body |

| |

(n = 4/4) |

(n = 2/2) |

(n = 5/5) |

(n = 3/3) |

| cuticle perforation |

- |

no |

no |

yes |

yes |

| |

|

|

(n = 5/5) |

(n = 1/3) |

| autolysis |

- |

partially |

partially |

complete |

complete |

| |

(n = 2/4) |

(n = 1/2) |

(n = 5/5) |

(n = 3/3) |

| fruiting bodies |

- |

no |

no |

yes |

no |

| |

|

|

(n = 3/5) |

|

Table 2.

Differences in the pathomechanisms of the two mycological brood diseases of A. mellifera.

Table 2.

Differences in the pathomechanisms of the two mycological brood diseases of A. mellifera.

| |

Stonebrood |

Chalkbrood |

| Pathogen |

Aspergillus flavus |

Ascosphaera apis |

| Incubation period |

< 24 h |

48-72 h |

| Localisation Germination |

whole midgut |

caudal part of midgut |

| Time of Death |

from 24 – 48 h p.i. |

from 72 h |