Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

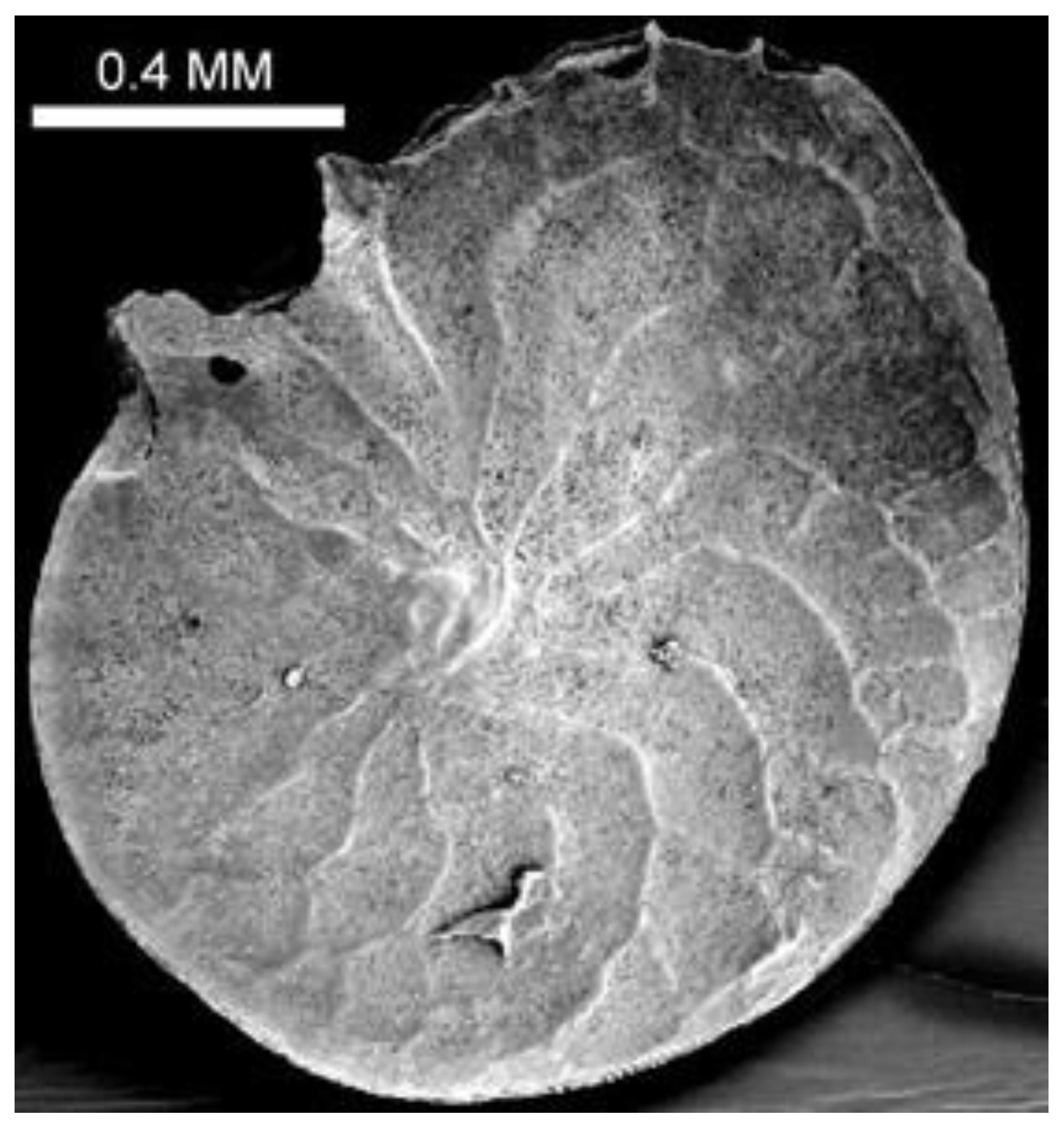

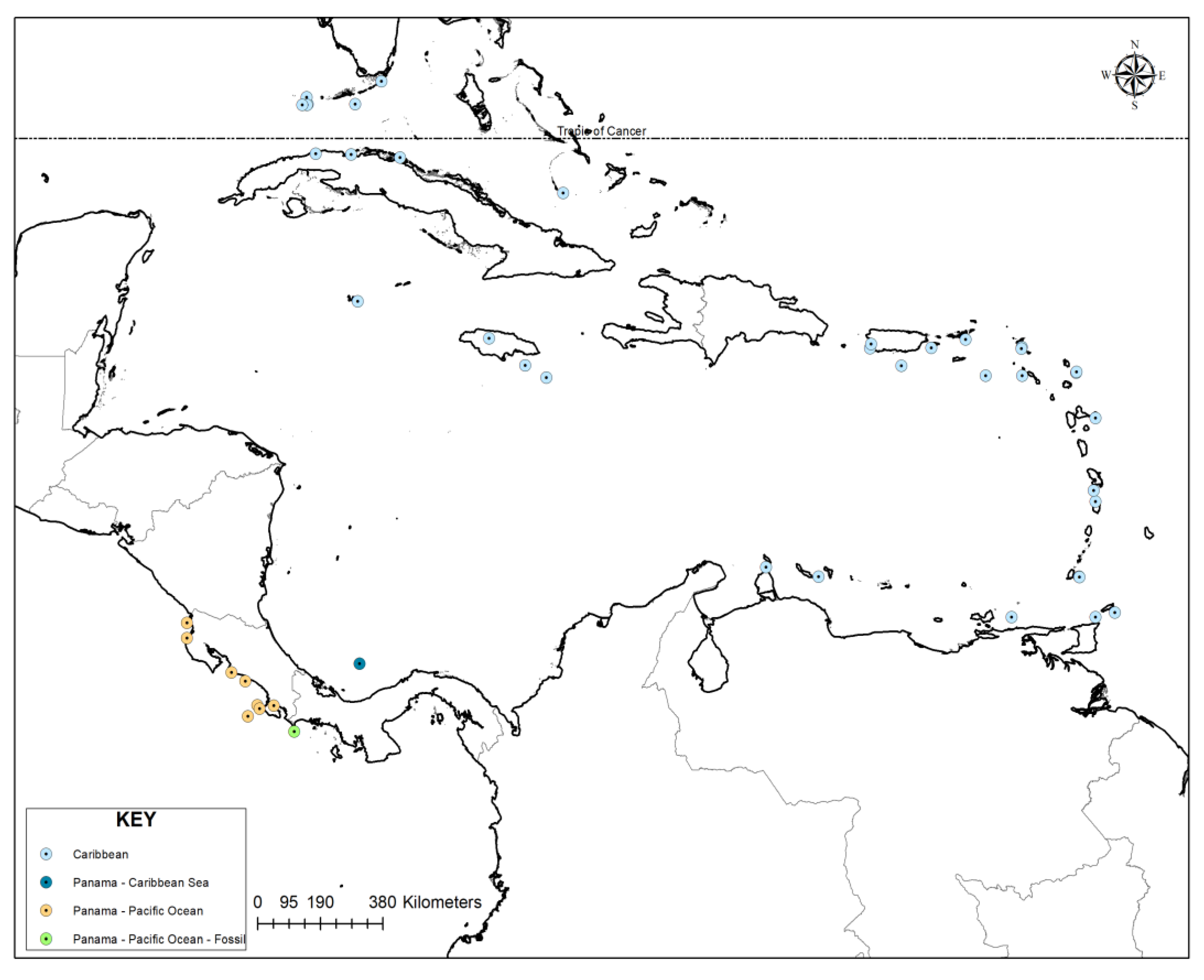

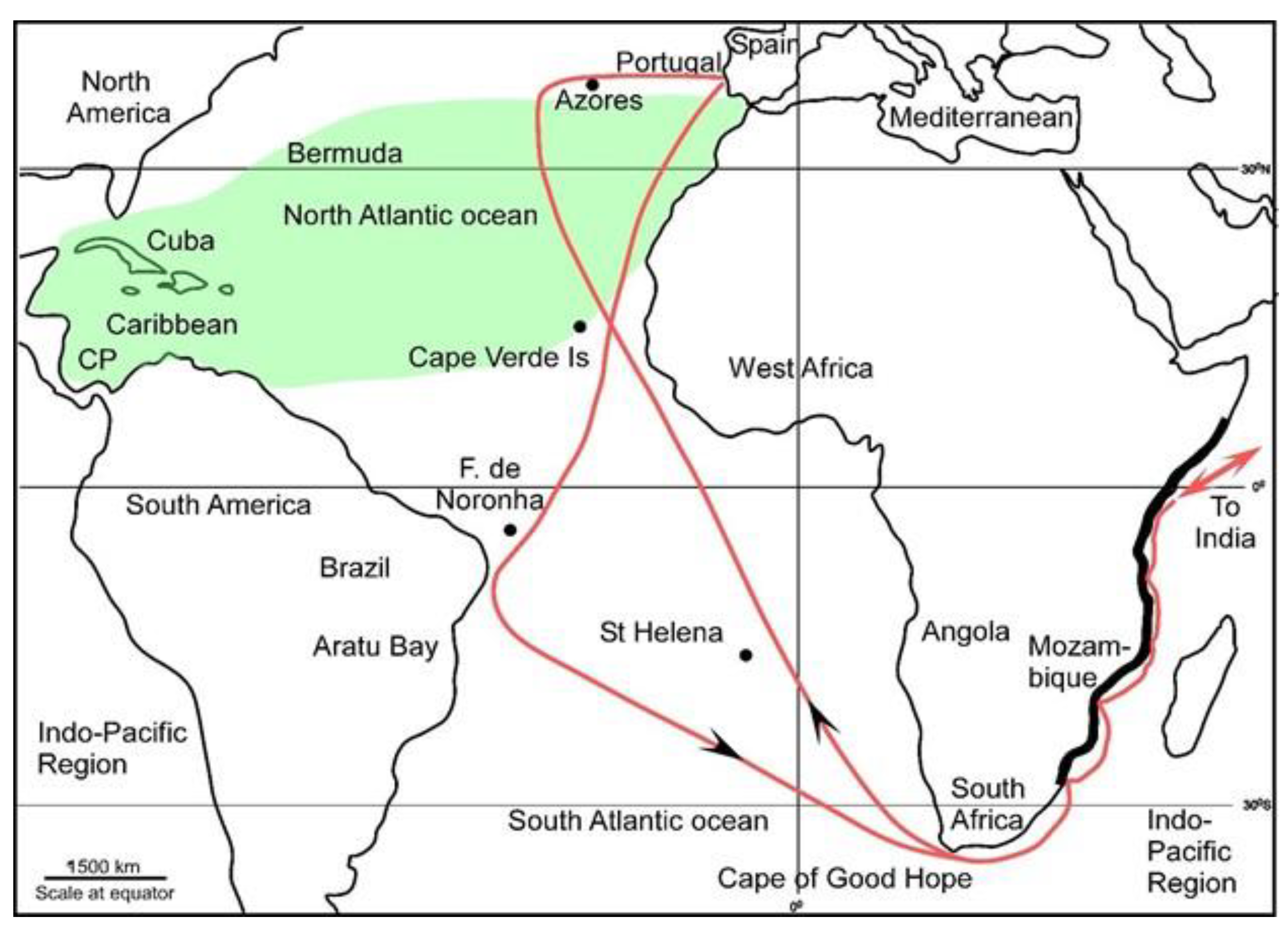

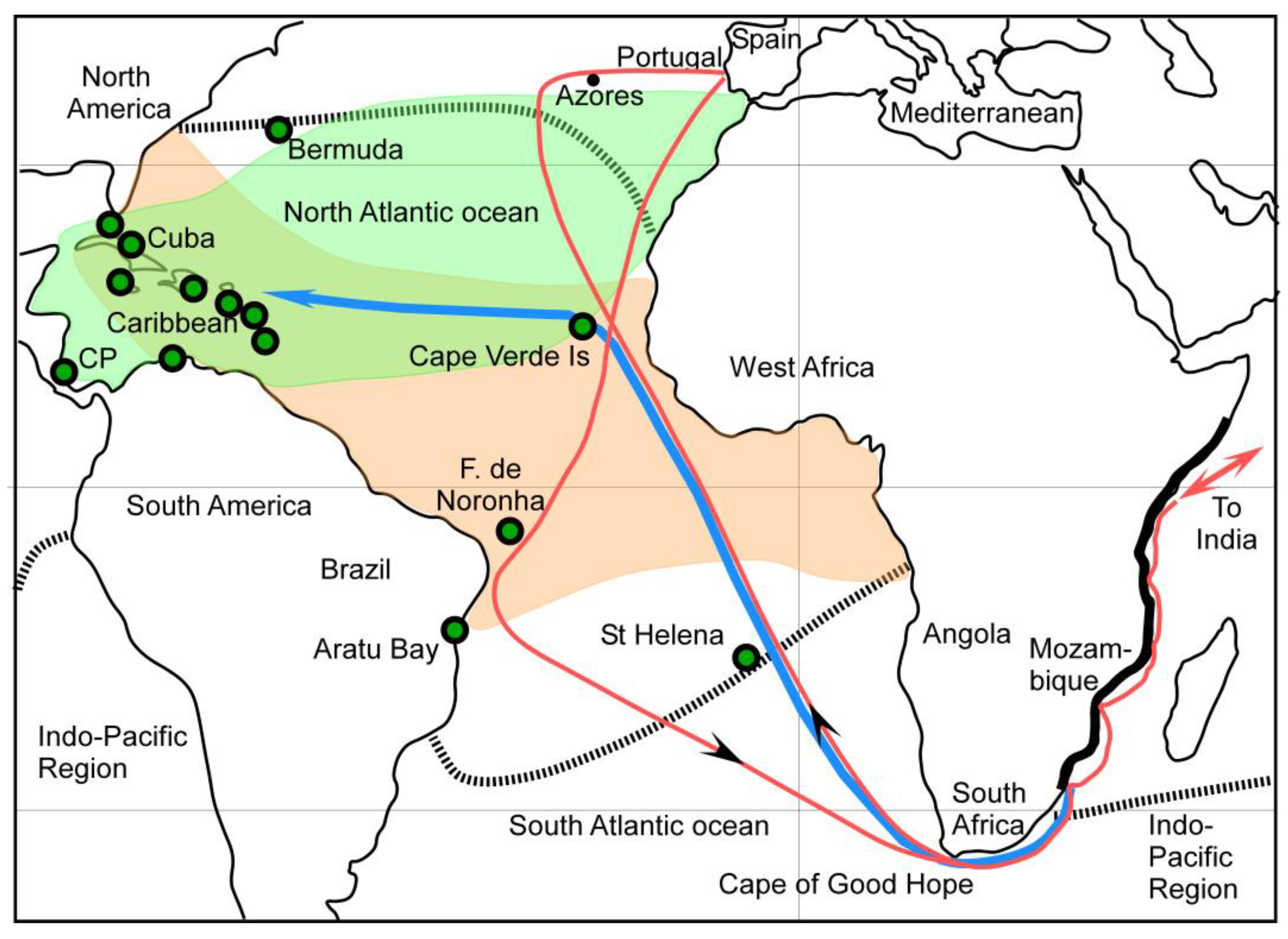

The larger benthic foraminifera are a group of marine protists, harbouring symbiotic algae, that are geographically confined to shallow tropical and subtropical waters, often associated with coral reefs. The resulting controls on availability of habitat and rates of dispersion make these foraminifers, particularly the genus Amphistegina, useful proxies in the study of invasive marine biota, transported through hull fouling and ballast water contamination in modern commercial shipping. However, there is limited information on the importance of these dispersal mechanisms for foraminifers in the Pre-Industrial Era (pre-1850) for the Atlantic and Caribbean region. This paper examines possible constraints and vectors controlling the invasion of warm-water taxa from the Indo-Pacific region to the Atlantic and Caribbean region. Heterostegina depressa, first described from St. Helena, a remote island in the South Atlantic, provides a test case. The paper postulates that invasions through natural range expansion or ocean currents were unlikely along the possible available routes and hypothesize that anthropogenic vectors, particularly sailing ships, were the most likely means of transport. It concludes that the invasion of the Atlantic by H. depressa was accomplished within the Little Ice Age (1350–1850 C.E.), during the period between the start of Portuguese marine trade with east Africa in 1497 and the first description of H. depressa in 1826. The hypothesis is likely applicable to other foraminifera and other biota currently resident in the Atlantic and Caribbean region. The model presented provides well defined parameters that can be tested using methods such as isotopic dating of foraminiferal assemblages in cores and genetic indices of similarity of geographic populations

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Hypothesis

3.1. Heterostegina Depressa Invaded the Atlantic Caribbean Region from the Indo-Pacific Region But Not via the Central American Seaway

3.2. The Only Other Available Invasion Route Was Around South Africa

3.3. South Africa Presents Barriers for LBF Invasion of the ACR Through Natural Vectors

3.4. Anthropogenic Vectors Transported H. depressa to the ACR

3.5. Heterostegina Depressa Invaded the ACR After the Late 15th Century

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACR | Atlantic and Caribbean region |

| BP | Before Present |

| CAS | Central American Seaway |

| CE | Common Era |

| CGH | Cape of Good Hope |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| IPR | Indo-Pacific region |

| LBF | Larger Benthic Foraminifera |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration. |

| SST | Sea Surface Temperature |

| SVS | Scientific Visualization Studio |

Appendix A

| Record No | Publication | Year | Genus | Species | Locality | Lat | Long | Site Desc | Country | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12802 | BROOK S 1973 | 1973 | Heterostegina | antillarum | S PUERTO RICO | 17.56 | -66.31 | Puerto Rico | ||

| 12803 | BERMUD EZ 1935 | 1935 | Heterostegina | antillarum | NORTHERN CUBA | 23.08 | -81.33 | Cuba | ||

| 12804 | 0 'OR Bl GNY 1839 | 1839 | Heterostegina | antillarum | CUBA | 23 | -80 | Cuba | ||

| 12805 | S EIGLIE 1970 A | 1970 | Heterostegina | antillarum | SE PUERTO RICO | 18.03 | -65.49 | Puerto Rico | ||

| 12806 | S E JGLIE 1971 A | 1971 | Heterostegina | antillarum | SW PUERTO RICO | 18.02 | -67.16 | Puerto Rico | ||

| 12807 | S EN GUPT A SC HAFER 1973 | 1973 | Heterostegina | antillarum | NW ST LUCIA | 14.02 | -61 | St Lucia | ||

| 12808 | D 'OR BI GNY 1839 | 1839 | Heterostegina | antillarum | JAMAICA | 17.57 | -76.58 | Jamaica | ||

| 12809 | HOFK ER, SR . 1956 | 1956 | Heterostegina | antillarum | ST. CROIX | 17.3 | -64 | St Croix | ||

| 12810 | D ROOGE R K A ASS CHJE TER 1958 | 1958 | Heterostegina | antillarum | TRINIDAD SHELF | 11 | -61 | Trinidad | ||

| 12811 | HOFK ER, SR. 1964 | 1964 | Heterostegina | antillarum | GRENADA | 12.05 | -61.45 | Aruba | ||

| 12812 | HOFK ER, SR. 1964 | 1964 | Heterostegina | antillarum | ARUBA | 12.3 | -70 | Aruba | ||

| 12813 | R AOF CR O 1976B | 1976 | Heterostegina | antillarum | TOBAGO ISLAND | 11.12 | -60.48 | Tobago | ||

| 12814 | HOFK ER1 SR. 1976 | 1976 | Heterostegina | antillarum | LA DESIRADE | 16.2 | -61 | La Desirade | ||

| 12815 | HOFK ER , SR . 1976 | 1976 | Heterostegina | antillarum | ST. MARTIN | 18.05 | -63.02 | St Martin | ||

| 12816 | HOF K ER, SR. 1976 | 1976 | Heterostegina | antillarum | CURACAO | 12.05 | -68.57 | Curacao | ||

| 12817 | HOFK ER1 SR . 1 976 | 1976 | Heterostegina | antillarum | GRAND CAYMAN | 19.25 | -81.15 | Grand Cayman | ||

| 12818 | HOFK ER1 SR . 1976 | 1976 | Heterostegina | antillarum | HAVANA, CUBA | 23.1 | -82.3 | Cuba | ||

| 12819 | HOFK ER, SR . 1964 | 1964 | Heterostegina | antillarum | ST. MARTIN | 18.01 | -63.03 | St Martin | ||

| 12820 | HOFK ER , SR . 1964 | 1964 | Heterostegina | antillarum | ST. EUSTATIUS | 17.3 | -63.01 | St Eustatius | ||

| 12821 | HOFK ER, SR. 1976 | 1976 | Heterostegina | antillarum | VIRGIN ISLANDS | 18.25 | -64.55 | Aruba | ||

| 12822 | HOFK ER1 SR . 1976 | 1976 | Heterostegina | antillarum | W PUERTO RICO | 18.13 | -67.13 | Puerto Rico | ||

| 12823 | HOFK ER1 SR . 1976 | 1976 | Heterostegina | antillarum | MARTINIQUE | 14.3 | -61.05 | Martinique | ||

| 12824 | HOFK ER, SR . 1976 | 1976 | Heterostegina | antillarum | GRENADA | 12.04 | -61.44 | Grenada | ||

| 12825 | lLL lNG 1952 | 1952 | Heterostegina | antillarum | BAHAMA BANKS | 22.08 | -75.54 | Bahamas | ||

| 12826 | BERMUDEZ 1937 | 1937 | Heterostegina | antillarum | MORANT CAYS, JAMAICA | 17.25 | -76 | Jamaica | ||

| 12827 | B R AS IE R 1975 B | 1975 | Heterostegina | antillarum | BARBUDA | 17.38 | -61.53 | Barbuda | ||

| 12828 | B A S IER 1975 A | 1975 | Heterostegina | antillarum | BARBUDA | 17.4 | -61.52 | Barbuda | ||

| 12829 | CUSHMAN 1921 | 1921 | Heterostegina | antillarum | MONTEGO BAY, JAMAICA | 18.28 | -77.56 | Jamaica | ||

| 12830 | S E IGLIE 1967 | 1967 | Heterostegina | antillea | ARAYA-LOS TESTIGOS SHELF | 11 | -63.3 | Araya Los Testigos | ||

| 19087 | NOR T ON 1930 | 1930 | Heterostegina | antillarum | TORTUGAS, FLA | 24.4 | -82.52 | Tortugas Florida | ||

| 19068 | CUSHMAN 1930 | 1930 | Heterostegina | antillarum | TORTUGAS, FLA | 24.58 | -82.55 | Tortugas Florida | ||

| 19089 | CUSHMAN 1922A | 1922 | Heterostegina | antillarum | TORTUGAS | 24.38 | -82.54 | Tortugas | ||

| 14797 | HOWAR D 1965 | 1965 | Heterostegina | depressa | S. FLORIDA KEYS | 24.4 | -81.22 | Florida Keys | ||

| 14798 | BOCK 1971 | 1971 | Heterostegina | depressa | FLORIDA BAY | 25 | -80.5 | Florida Bay | ||

| MO64322 | Bock. 1971. Miami Geol.Soc.Mem. (n.1): 57, pl.21,f.3. | 1958 | Heterostegina | depressa | GULF OF MEXICO | 24.38 | -82.67 | Gulf of Mexico | ||

| Weinmann &Langer | 2011 | Malindi 1 (Kenya) | -3.2161 | 40.1337 | Outer lagoon (exposed) | Kenya | ||||

| Weinmann &Langer | 2011 | Malindi 2 (Kenya) | -3.2196 | 40.1263 | Inner lagoon | Kenya | ||||

| Weinmann &Langer | 2011 | Kilifi (Kenya) | -3.6425 | 39.8631 | Rock pool, beach | Kenya | ||||

| Weinmann &Langer | 2012 | Coco Beach (Tanzania) | -6.7752 | 39.2843 | Beach (exposed) | Tanzania | ||||

| Weinmann &Langer | 2012 | Kilwa 1 (Tanzania) | -8.8893 | 39.5267 | Outer lagoon (sheltered) | Tanzania | ||||

| Weinmann &Langer | 2012 | Kilwa 2 (Tanzania) | -8.8978 | 39.5191 | Inner lagoon | Tanzania | ||||

| Weinmann &Langer | 2012 | Carrusca (Mozambique) | -15.0049 | 40.773 | Rock pool, beach | Mozambique | ||||

| Weinmann &Langer | 2012 | Mafamete (Mozambique) | -16.3517 | 40.0305 | Beach (exposed) | Mozambique | ||||

References

- Hottinger, L. (1983). Processes determining the distribution of larger foraminifera in space and time. Utrecht Micropaleontological Bulletins(30), 239-253.

- Hallock, P. (1988). Interoceanic differences in foraminifera with symbiotic algae: a result of nutrient supplies?

- Hallock, P. (1999). Symbiont-bearing foraminifera. In B. K. Sen Gupta (Ed.), Modern foraminifera (pp. 123-139). Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht.

- Hallock, P. (2000). Symbiont-bearing foraminifera: harbingers of global change? Micropaleontology, 95-104.

- Geoffrey Adams, C., Lee, D. E., & Rosen, B. R. (1990). Conflicting isotopic and biotic evidence for tropical sea-surface temperatures during the Tertiary. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 77(3), 289-313. [CrossRef]

- Röttger, R., Krüger, R., & de Rijk, S. (1990). Trimorphism in foraminifera (protozoa) - verification of an old hypothesis. Eur J Protistol, 25(3), 226-228. [CrossRef]

- Langer, M. R., & Hottinger, L. (2000). Biogeography of selected" larger" foraminifera. Micropaleontology, 46, 105-126.

- Renema, W. (2007). Fauna Development of Larger Benthic Foramanifera in the Cenozoic of Southeast Asia. In W. Renema (Ed.), Biogeography, time and place: distributions, barriers and islands. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Robbins, L. , Knorr, P., Wynn, J., Hallock, P., & Harries, P. (2016). Interpreting the role of pH on stable isotopes in large benthic foraminifera. ICES Journal of Marine Science: Journal du Conseil, 74, fsw056. [CrossRef]

- Förderer, M., Rödder, D., & Langer, M. R. (2018). Patterns of species richness and the center of diversity in modern Indo-Pacific larger foraminifera. Scientific Reports, 8(1), 8189. [CrossRef]

- Reymond, C. E., Hallock, P., & Westphal, H. (2022). Preface for “Tropical Large Benthic Foraminifera: Adaption, Extinction, and Radiation”. Journal of Earth Science, 33(6), 1339-1347. [CrossRef]

- Lintner, M., Lintner, B., Schagerl, M., Wanek, W., & Heinz, P. (2023). The change in metabolic activity of a large benthic foraminifera as a function of light supply. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 8240.

- Duijser, C. M., van Oostveen, R. S., Girard, E. B., Renema, W., & Wilken, S. (2024). Light and temperature niches of the large benthic foraminifer Heterostegina depressa. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 109075.

- Prazeres, M., & Renema, W. (2019). Evolutionary significance of the microbial assemblages of large benthic Foraminifera. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc, 94(3), 828-848. [CrossRef]

- Hallock, P., Forward, L. B., & Hansen, H. J. (1986). Influence of environment on the test shape of Amphistegina. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 16(3), 224-231. [CrossRef]

- Hallock, P., Koukousioura, O., & BadrElDin, A. M. (2024). Why Amphistegina lobifera, a tropical benthic foraminiferal species, is thriving at temperate latitudes in the Mediterranean Sea. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 54(3), 237-248.

- Hollaus, S., & Hottinger, L. (1997). Temperature dependance of endosymbiontic relationships? Evidence from the depth range of Mediterranean Amphistegina lessonii (Foraminiferida) truncated by the thermocline. Eclogae geologicae Helvetiae, 90(3), 591-598.

- Hyams, O., Almogi-Labin, A., & Benjamini, C. (2002). Larger foraminifera of the southeastern Mediterranean shallow continental shelf off Israel. Israel Journal of Earth Sciences, 51.

- Langer, M. R., Thissen, J. M., Makled, W. A., & Weinmann, A. E. (2013). The foraminifera from the Bazaruto Archipelago (Mozambique). Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie-Abhandlungen, 267(2), 155-170.

- Weinmann, A. E. , Rödder, D., Lötters, S., & Langer, M. R. (2013). Traveling through time: The past, present and future biogeographic range of the invasive foraminifera Amphistegina spp. in the Mediterranean Sea. Marine Micropaleontology 105, 30–39. [CrossRef]

- Ross, B. J., & Hallock, P. (2019). Survival and recovery of the foraminifer Amphistegina gibbosa and associated diatom endosymbionts following up to 20 months in aphotic conditions. Marine Micropaleontology, 149, 35-43. [CrossRef]

- Hallock, P., & Reymond, C. E. (2022). Contributions of Trimorphic Life Cycles to Dispersal and Evolutionary Trends in Large Benthic Foraminifers. Journal of Earth Science, 33(6), 1425-1433. [CrossRef]

- Raposo, D. S., Zufall, R. A., Caruso, A., Titelboim, D., Abramovich, S., Hassenrück, C., Kucera, M., & Morard, R. (2023). Invasion success of a Lessepsian symbiont-bearing foraminifera linked to high dispersal ability, preadaptation and suppression of sexual reproduction. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 12578. [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, C. H., & Ingram, W. M. (1939). Fouling organisms in Hawaii. Bernice P. Bishop Museum.

- Carlton, J. T. (1989). Man's role in changing the face of the ocean: biological invasions and implications for conservation of near-shore environments. Conservation Biology, 3(3), 265-273.

- Gollasch, S. (2002). The Importance of Ship Hull Fouling as a Vector of Species Introductions into the North Sea. Biofouling, 18(2), 105-121. [CrossRef]

- Streftaris, N., Zenetos, A., & Papathanassiou, E. (2005). Globalisation in marine ecosystems: the story of non-indigenous marine species across European seas. Oceanography and Marine Biology, 43, 419-453.

- Balcolm, N. (2006). Hull Fouling's a Drag on Boats and Local Ecosystems. Wrack Lines, 20. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/wracklines/20.

- Betancur-R., R., Hines, A., Acero P., A., Ortí, G., Wilbur, A. E., & Freshwater, D. W. (2011). Reconstructing the lionfish invasion: insights into Greater Caribbean biogeography. Journal of Biogeography, 38(7), 1281-1293. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, I. C., & Simkanin, C. (2012). The biology of ballast water 25 years later. Biological Invasions, 14(1), 9-13. [CrossRef]

- Buddo, D. S. A., Steel, R. D., & Webber, M. K. (2012). Public health risks posed by the invasive Indo-Pacific green mussel, Perna viridis (Linnaeus, 1758) in Kingston Harbour, Jamaica. BioInvasions Record, 1(3).

- Holland, B. S., Dawson, M. N., Crow, G. L., & Hofmann, D. K. (2004). Global phylogeography of Cassiopea (Scyphozoa: Rhizostomeae): molecular evidence for cryptic species and multiple invasions of the Hawaiian Islands. Marine Biology, 145(6), 1119-1128. [CrossRef]

- Prazeres, M., Martínez-Colón, M., & Hallock, P. (2020). Foraminifera as bioindicators of water quality: The FoRAM Index revisited. Environmental Pollution, 257, 113612. [CrossRef]

- Prazeres, M., Roberts, T. E., Ramadhani, S. F., Doo, S. S., Schmidt, C., Stuhr, M., & Renema, W. (2021). Diversity and flexibility of algal symbiont community in globally distributed larger benthic foraminifera of the genus Amphistegina. BMC Microbiology, 21(1), 243. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S., Robinson, E., Jiang, M. M., Robinson, N., & Özcan, E. (2024). A larger benthic foraminiferal zonation for the Cenozoic of the Americas. Carnets Geol., 24, 163-172.

- Kirch, P. V. (1982). The impact of the prehistoric Polynesians on the Hawaiian ecosystem. Pacific Science, 36, 1-14.

- Carlton, J. T. (1996). Biological Invasions and Cryptogenic Species. Ecology, 77(6), 1653-1655. [CrossRef]

- Gollasch, S. (2006). Overview on introduced aquatic species in European navigational and adjacent waters. Helgoland Marine Research, 60(2), 84-89. [CrossRef]

- Holzmann, M., Hohenegger, J., Apothéloz-Perret-Gentil, L., Morard, R., Abramovich, S., Titelboim, D., & Pawlowski, J. (2022). Operculina and Neoassilina: A Revision of Recent Nummulitid Genera Based on Molecular and Morphological Data Reveals a New Genus. Journal of Earth Science, 33(6), 1411-1424. [CrossRef]

- Wanner, H., Beer, J., Bütikofer, J., Crowley, T. J., Cubasch, U., Flückiger, J., Goosse, H., Grosjean, M., Joos, F., Kaplan, J. O., Küttel, M., Müller, S. A., Prentice, I. C., Solomina, O., Stocker, T. F., Tarasov, P., Wagner, M., & Widmann, M. (2008). Mid- to Late Holocene climate change: an overview. Quaternary Science Reviews, 27(19), 1791-1828. [CrossRef]

- Paasche, Ø., & Bakke, J. (2010). Defining the Little Ice Age. Climate of the Past Discussions, 2010, 2159-2175. [CrossRef]

- Gebbie, G. (2019). Atlantic Warming Since the Little Ice Age. Oceanography, 32(1), 220-230. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26604982.

- d'Orbigny, A. D. (1826). Tableau méthodique de la classe des Céphalopodes. Annales des Sciences Naturelles. Series,.

- Banner, F., & Hodgkinson, R. (1991). A revision of the foraminiferalsubfamily Heterostegininae. Revista Espanola de Micropaleontologia, 23(2), 101-140.

- Edwards, T. and Robinson, E. (submitted) Note on the provenance of the neotype of Heterostegina depressa d’Orbigny 1826 (Foraminifera).

- d’Orbigny, A. D. (1839). Foraminiferes, in Ramon de la Sagra. Histoire physique, pand.

- Carman, K. W. (1933). The shallow-water foraminifera of Bermuda. Massachusetts Institute of Technology].

- Rocha, A. T., & Mateu, G. (1971). Contribuição para o conhecimento dos foraminíferos actuais da ilha de Maio (Arquipélago de Cabo Verde). Instituto de Investigação Científica de Angola. https://books.google.com.jm/books?id=fTMJAQAAMAAJ.

- Carboni, M. G., Mandarino, G., & Matteucci, R. (1979). Foraminiferids of the Aratu Bay (Bahia, Brazil). Geologica Romana, 18, 317-330.

- Carboni, M., Mandarino, G., & Matteucci, R. (1981). Foraminiferids of Todos os Santos Bay (Bahia, Brazil). Geologica Romana, 20, 103-124.

- Culver, S. J., & Buzas, M. A. (1982). Distribution of Recent Benthic Foaraminifera in the Caribbean Region. Smithsonian Contributions of the Marine Sciences, 14.

- Levy, A., Mathieu, R., Poignant, A., Rosset-Moulinier, M., & Ambroise, D. (1995). Benthic foraminifera from the Fernando de Noronha Archipelago (northern Brazil). Marine Micropaleontology, 26(1), 89-97. [CrossRef]

- Havach, S. M., & Collins, L. S. (1997). The distribution of Recent benthic Foraminifera across habitats of Bocas del Toro, Caribbean Panama. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 27, 232-249.

- Wilson, B. (2008). Population structures among epiphytal foraminiferal communities, Nevis, West Indies. Journal of Micropalaeontology, 27(1), 63-73.

- Seiglie, G. (1965). Preliminary framework on the stratigraphic distribution of large foraminifera from Cuba. Lagena, 7, 23-30.

- Frost, S. H., & Langenheim, R. L. (1974). Cenozoic reef biofacies; Tertiary larger Foraminifera and scleractinian corals from Chiapas, Mexico. Northern Illinois University Press.

- Robinson, E. (2003). Zoning the White Limestone Group of Jamaica using larger foraminiferal genera: a review and proposal. Cainozoic Research, 3(1/2), 39-75.

- Cole, W. S. (1954). Larger foraminifera and smaller diagnostic foraminifera from the Bikini Drill Holes. US Geological Survey Professional Papers, 260, 569-608.

- Hottinger, L. (1977). Foraminiferes operculiniformes: Mémoires du Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle, Nouvelle Série, Série C. Sciences de la Terre, 40, 159.

- Oron, S., Friedlander, A. M., Sala, E., & Goodman-Tchernov, B. N. (2024). Shallow water foraminifera from Niue and Beveridge Reef(South Pacific): insights into ecologicalsignificance and ecosystem integrity. Royal Society Open Science, 11(230997). [CrossRef]

- Crouch, R. W., & Poag, C. W. (1987). Benthic foraminifera of the Panamanian Province: distribution and origins. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 17(2), 153-176. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, K. J., Wacker, M. A., Robinson, E., Dixon, J. F., & Wingard, G. L. (2006). A cyclostratigraphic and borehole-geophysical approach to development of a three-dimensional conceptual hydrogeologic model of the karstic Biscayne aquifer, southeastern Florida [Report](2005-5235). (Scientific Investigations Report, Issue. U. S. G. Survey. https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/sir20055235.

- Kohl, B., & Robinson, E. (1998). Foraminifera and biostratigraphy of the Bowden shell bed, Jamaica, West Indies. Mededelingen van de Werkgroep voor Tertiaire en Kwartaire Geologie, 35(1/4), 29-46.

- Gudnitz, M. N., Collins, L. S., & O'Dea, A. (2021). Foraminiferal communities of a mid-Holocene reef: Isla Colón, Caribbean Panama. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology, 562, 110042. [CrossRef]

- O'Dea, A., Lessios, H. A., Coates, A. G., Eytan, R. I., Restrepo-Moreno, S. A., Cione, A. L., Collins, L. S., de Queiroz, A., Farris, D. W., Norris, R. D., Stallard, R. F., Woodburne, M. O., Aguilera, O., Aubry, M. P., Berggren, W. A., Budd, A. F., Cozzuol, M. A., Coppard, S. E., Duque-Caro, H., . . . Jackson, J. B. (2016). Formation of the Isthmus of Panama. Sci Adv, 2(8), e1600883. [CrossRef]

- Rögl, V. F. (1997). Palaeogeographic Considerations for Mediterranean and Paratethys Seaways (Oligocene to Miocene). Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien. Serie A für Mineralogie und Petrographie, Geologie und Paläontologie, Anthropologie und Prähistorie, 99, 279-310. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41702129.

- Renema, W., Bellwood, D. R., Braga, J. C., Bromfield, K., Hall, R., Johnson, K. G., Lunt, P., Meyer, C. P., McMonagle, L. B., Morley, R. J., O'Dea, A., Todd, J. A., Wesselingh, F. P., Wilson, M. E., & Pandolfi, J. M. (2008). Hopping hotspots: global shifts in marine biodiversity. Science, 321(5889), 654-657. [CrossRef]

- Adams, C. (1983). Dating the terminal Tethyan event. Reconstruction of marine paleoenvironments, Utrecht Micropal. Bull., 30, 273-298.

- Jones, R. W., Simmons, M. D., & Whittaker, J. E. (2006). On the stratigraphical and palaeobiogeographical significance of Borelis melo melo (Fichtel & Moll, 1798) and B. melo curdica (Reichel, 1937) (Foraminifera, Miliolida, Alveolinidae). Journal of Micropalaeontology, 25, 175 - 185.

- Darling, K. F., & Wade, C. M. (2008). The genetic diversity of planktic foraminifera and the global distribution of ribosomal RNA genotypes. Marine Micropaleontology, 67(3), 216-238. [CrossRef]

- Adams, C. G. (1967). Tertiary foraminifera in the Tethyan, American and Indo-Pacific provinces. Systematics Association Publications, 7, 195-217.

- Bock, W. D. (1969). Thalassia testudinum, a habitat and means of dispersal for shallow water benthonic foraminifera. Transactions of the Gulf-Coast Association of Geological Societies 19, 337-340.

- Lessard, R. H. (1980). Distribution patterns of intertidal and shallow-water foraminifera of the tropical Pacific Ocean. In W. V. Sliter (Ed.), Studies in Marine Micropaleontology and Paleoecology: A Memorial Volume to Orville L. Bandy (Vol. 19, pp. 0). Cushman Foundation for Foraminiferal Research.

- DeVantier, L. (1992). Rafting of tropical marine organisms on buoyant coralla. Marine Ecology - Progess Series, 86, 301-301.

- Tanaka, H., Yasuhara, M., & Carlton, J. T. (2018). Transoceanic transport of living marine Ostracoda (Crustacea) on tsunami debris from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake. Aquatic Invasions, 13(1), 125-135. [CrossRef]

- Li, C., Jones, B., & Blanchon, P. (1997). Lagoon-shelf sediment exchange by storms--evidence from foraminiferal assemblages, east coast of Grand Cayman, British West Indies. Journal of Sedimentary Research, 67(1), 17-25.).

- Censky, E. J., Hodge, K., & Dudley, J. (1998). Over-water dispersal of lizards due to hurricanes. Nature, 395(6702), 556-556. [CrossRef]

- Cedhagen, T., & Middelfart, P. (1998). Attachment to gastropod veliger shells—a possible mechanism of disperal in benthic foraminiferans. Phuket Marine Bilological Center Special Publication, 18, 117-122.

- Brochet, A.-L., Gauthier-Clerc, M., Guillemain, M., Fritz, H., Waterkeyn, A., Baltanás, Á., & Green, A. J. (2010). Field evidence of dispersal of branchiopods, ostracods and bryozoans by teal (Anas crecca) in the Camargue (southern France). Hydrobiologia, 637, 255-261.

- Pignatti, J., Frezza, V., Benedetti, A., Carbone, F., Accordi, G., & Matteucci, R. (2012). Recent foraminiferal assemblages from mixed carbonate-siliciclastic sediments of southern Somalia and eastern Kenya. Bollettino Della Societa Geologica Italiana, 131, 47-66.

- Cohen, A., & Tyson, P. (1995). Sea-surface temperature fluctuations during the Holocene off the south coast of Africa: implications for terrestrial climate and rainfall. The Holocene, 5(3), 304-312.

- Mann, M. E., Zhang, Z., Rutherford, S., Bradley, R. S., Hughes, M. K., Shindell, D., Ammann, C., Faluvegi, G., & Ni, F. (2009). Global Signatures and Dynamical Origins of the Little Ice Age and Medieval Climate Anomaly. Science, 326(5957), 1256-1260. [CrossRef]

- Langer, M. R. , Weinmann, A. E., Lötters, S., Bernhard, J. M., & Rödder, D. (2013). Climate-Driven Range Extension of Amphistegina (Protista, Foraminiferida): Models of Current and Predicted Future Ranges. PLOS ONE, 8(2), e54443. [CrossRef]

- Lessios, H. A., & Robertson, D. R. (2013). Speciation on a round planet: phylogeography of the goatfish genus Mulloidichthys. Journal of Biogeography, 40(12), 2373-2384. [CrossRef]

- Peeters, F. J., Acheson, R., Brummer, G. J., De Ruijter, W. P., Schneider, R. R., Ganssen, G. M., Ufkes, E., & Kroon, D. (2004). Vigorous exchange between the Indian and Atlantic oceans at the end of the past five glacial periods. Nature, 430(7000), 661-665. [CrossRef]

- Beech, N., Rackow, T., Semmler, T., Danilov, S., Wang, Q., & Jung, T. (2022). Long-term evolution of ocean eddy activity in a warming world. Nature Climate Change, 12(10), 910-917. [CrossRef]

- Weinmann, A. E., Rödder, D., Lötters, S., & Langer, M. R. (2013). Heading for New Shores: Projecting Marine Distribution Ranges of Selected Larger Foraminifera. PLOS ONE, 8(4), e62182. [CrossRef]

- McGann, M., Ruiz, G. M., Hines, A. H., & Smith, G. (2019). A Ship's Ballasting History As an Indicator of Foraminiferal Invasion Potential – an Example from Prince William Sound, Alaska, USA. Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 49(4), 434-455. [CrossRef]

- Carlton, J. T., & Hodder, J. (1995). Biogeography and dispersal of coastal marine organisms: experimental studies on a replica of a 16th-century sailing vessel. Marine Biology, 121(4), 721-730. [CrossRef]

- Chilton, C. (1911). Note on the dispersal of marine Crustacea by means of ships. Transactions of the New Zealand Institute, 43, 131-133.

- Carlton, J. T. (1987). Patterns of transoceanic marine biological invasions in the Pacific Ocean. Bulletin of Marine Science, 41(2), 452-465.

- Crowley, R. (2016). Conquerors: how Portugal forged the first global empire. Faber & Fabe.

- Wenzlhuemer, R. (2020). Shipping Rocks and Sand: Ballast in Global History. 34th Annual Lecture of the German Historical Institute. November 11. Washington DC.

- Harris, L., & Richards, N. (2018). Preliminary investigations of two shipwreck sites in Cahuita National Park, Costa Rica. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 47(2), 405-418.

- Carlton, J. T. (1985). Transoceanic and interoceanic dispersal of coastal marine organisms: the biology of ballast water. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev., 23, 313-374.

- Russell-Wood, R. (1998). The Portuguese Empire, 1415-1808: A World on the Move. Johns.

- Mathew, K. M. (1988). History of the Portuguese navigation in India, 1497-1600. Mittal Publications. available online at indianculture.gov.in/flipbook/54143.

- Pearson, M. N. (1998). Port cities and intruders: the Swahili Coast, India, and Portugal in the early modern era. Johns Hopkins University Press. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb.31157.

- Narayan, G. R. , Herrán, N., Reymond, C. E., Shaghude, Y. W., & Westphal, H. (2022). Local Persistence of Large Benthic Foraminifera (LBF) under Increasing Urban Development: A Case Study from Zanzibar (Unguja), East Africa. Journal of Earth Science, 33(6), 1434-1450. [CrossRef]

- van Gorsel, J. H., Lunt, P., & Morley, R. (2014). Introduction to Cenozoic biostratigraphy of Indonesia-SE Asia. Berita Sedimentologi, 29(1), 6-40.

- Egerton, D. R., Games, A., Landers, J., Lane, K. E., & Wright, D. R. (2017). The Atlantic World; A History, 1400-1888. Wiley Blackwell.

- Bruce, I. (1922). The Discovery of St Helena. Wirebird: The Journal of the Friends of St Helena, 51, 26-43.

- Rowlands, B. W. (2004). Ships at St Helena, 1502-1613". Wirebird: The Journal of the Friends of St Helena 28, 5-10.

- Morgan, K. (2007). Slavery and the British empire: from Africa to America. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Drayton, R. H. (2000). Nature's government: science, imperial Britain, and the 'Improvement' of the World. Yale University Press.

- Edwards, T. (2014). Towards an historiography of the Hill Gardens at Cinchona, Jamaica. Caribbean Geography, 19, 69-88.

- Brady, H. B. (1884). Report on the foraminifera dredged by H. M. S. Challenger, during the years 1873-1876. Reports on the Scientific Results of the Voyage of the H. M. S. Challenger during the years 1873-1876. Zoology, 9, 1-814.

- Richardson, B. C. (1992). The Caribbean in the wider world, 1492-1992: A regional geography. Cambridge University Press.

- Sverdrup, H. U., Fleming, R., Howell, J. T., & Johnson, M. W. (1963). The oceans; their physics, chemistry, and general biology. https://archive.org/details/oceanstheirphysi0000sver_w4a6.

- Röttger, R. (1976). Ecological observations of Heterostegina depressa (Foraminifera, Nummulitidae) in the laboratory and in its natural habitat. International symposium of benthic foraminifera of continental margins.

- Schmidt, C., Kucera, M., & Uthicke, S. (2014). Combined effects of warming and ocean acidification on coral reef Foraminifera Marginopora vertebralis and Heterostegina depressa. Coral Reefs, 33(3), 805-818. [CrossRef]

- Hohenegger, J., Yordanova, E., & Hatta, A. (2000). Remarks on West Pacific Nummulitidae (Foraminfera)). Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 30(1), 3-28. [CrossRef]

- Alve, E., & Goldstein, S. T. (2010). Dispersal, survival and delayed growth of benthic foraminiferal propagules. Journal of Sea Research, 63(1), 36-51.

- Ross, B. J. , & Hallock, P. (2016). Dormancy in the Foraminfera: A Review Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 46(4), 358-368. [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K., Okai, T., & Hosono, T. (2014). Oxygen metabolic responses of three species of large benthic foraminifers with algal symbionts to temperature stress. PLOS ONE, 9(3), e90304.

- Deldicq, N., Alve, E., Schweizer, M., Asteman, I. P., Hess, S., Darling, K., & Bouchet, V. M. (2019). History of the introduction of a species resembling the benthic foraminifera Nonionella stella in the Oslofjord (Norway): morphological, molecular and paleo-ecological evidences. Aquatic Invasions, 14(2), 182-205.

- Nobes, K., Uthicke, S., & Henderson, R. (2008). Is light the limiting factor for the distribution of benthic symbiont bearing foraminifera on the Great Barrier Reef? Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 363(1), 48-57. [CrossRef]

- Holzmann, M., Hohenegger, J., & Pawlowski, j. (2003). Molecular data reveal parallel evolution in nummulitid foraminifera. The Journal of Foraminiferal Research, 33(4), 277-284.

- Eder, W., Hohenegger, J., Torres-Silva, A., & Briguglio, A. (2017). Morphometry of the larger foraminifera Heterostegina explaining environmental dependence, evolution and paleogeographic diversification. Proceedings of the 13th International Coral Reefs Symposium. Honolulu, Hawaii. http://coralreefs. org/conferences-and-workshops/proceedings-of-icrs13-2016.

- Kouyoumontzakis, G. (1989). Samples taken off Jamestown, Saint Helena Island (South Atlantic Ocean). Journal of Micropalaeontology, 8(1), 1-7.

- Cushman, J. A. (1919). Fossil foraminifera from the West Indies (Vol. 291). Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- Drooger, C. (1951). Foraminifera from the Tertiary of Anguilla, St. Martin and Tintamarre (Leeward Island, west Indies). Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Proceedings, Ser. B, 54, 53-65.

- Robinson, E. (1977). Larger imperforate foraminiferal zones of the Eocene of central Jamaica. In Memoria Segundo Congreso Latinoamericano de Geologia, Caracas, Venezuela (Vol. 11, pp. 1413-1421).

- Culver, S. J. , & Buzas, M. A. (1999). Biogeography of neritic benthic Foraminifera. In B. S. Gupta (Ed.), Modern foraminifera (pp. 93-102).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).