1. Introduction

The intestinal barrier performs several essential functions to maintain the body's homeostasis. These processes include facilitating nutrient, electrolyte, and water absorption, preventing pathogens from crossing the epithelial barrier, and modulation of xenobiotic intake[

1]. Biological models that use epithelial cell cultures grown in monolayers are often employed for applications such as measuring drug permeability and are considered the industry gold standard[

2]. Caco-2 and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cell lines are commonly used immortalized cell lines for

in vitro intestinal barrier models. The Caco-2 cell line was established in 1977 by Fogh et al.[

3] from human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells, and Madin and Darby[

4] isolated MDCK cells from canine renal cells in 1958. Traditionally, these cell lines have been used for permeability assays due to the ability to standardize culture methods. However, there are limitations to using these cell lines, as they only provide a rough estimate of passive drug diffusion and active drug transport through relatively inexpensive culture techniques[

5].

While these cell lines are readily available and affordable, their ability to accurately predict

in vivo results is limited. The usage of novel organoid (3D) technology was proposed to overcome the limitations of traditional 2D cell lines. These 3D structures can be derived from several sources, including embryonic stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, and Lgr5-positive cells representing an adult stem cell population derived from individual organs[

6]. Adult stem cell technology was first developed in 2009 by Sato et al.[

7] and is a novel method of 3D cell culture characterized by self-assembled structures derived from adult stem cells[

7]. Adult stem cells can be isolated from organs or tumors of interest using minimally invasive techniques[

8]. This results in the formation of organoids that have genetic stability over time without immortalization while maintaining microanatomical features and functional properties of the original tissue[

9]. Canine organoids can form 3D structures that replicate the physiological environment and create a cellular monolayer when placed in a dual-chamber permeable support system[

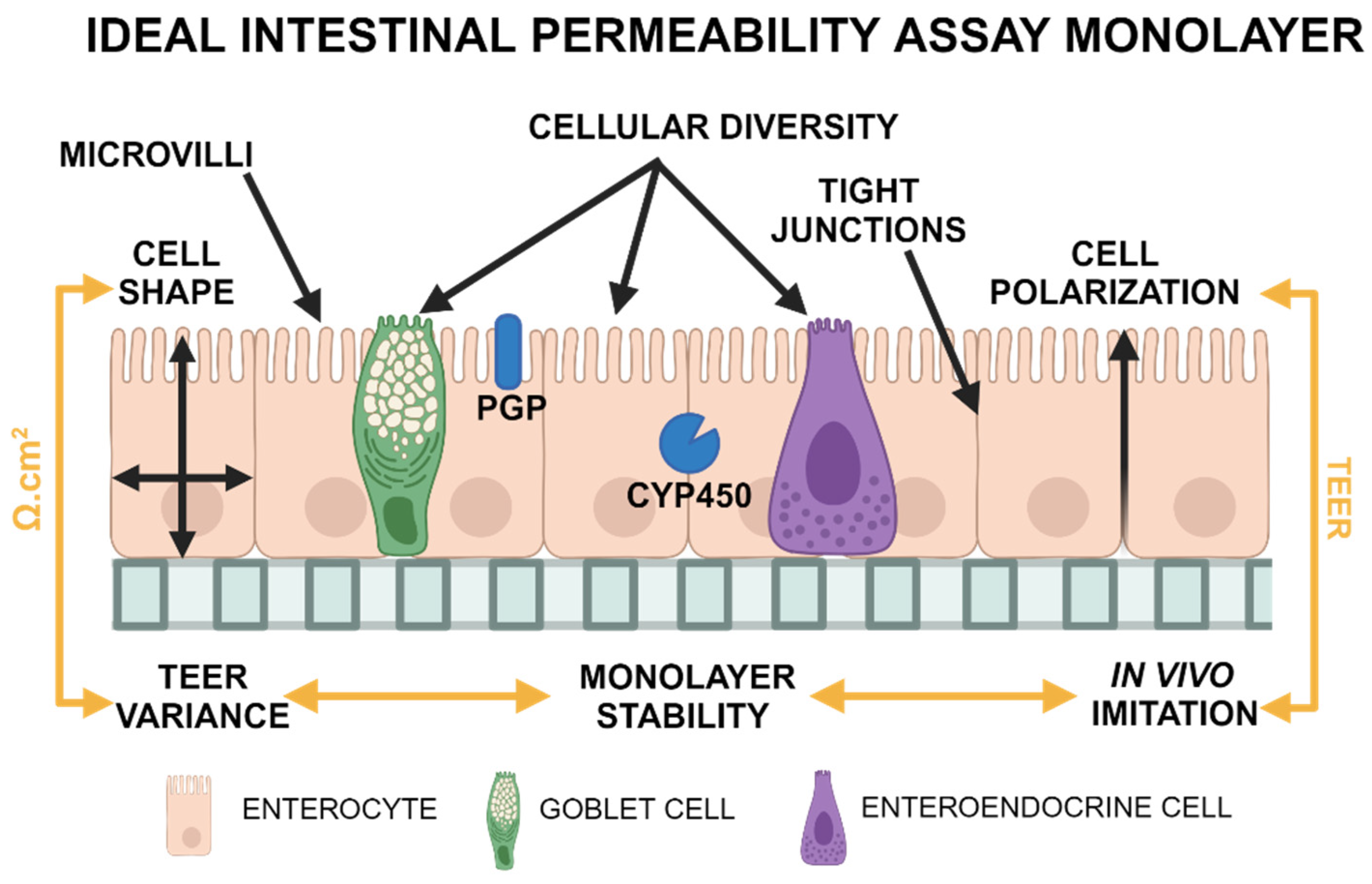

10]. The biological characteristics of an ideal intestinal permeability assay are illustrated in

Figure 1. In brief, the cell culture should be capable of representing the full spectrum of differentiated epithelial cells, with a comparable expression of tight junction proteins observed

in vivo, which is assessed by measuring transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) prior to the start of

in vitro permeability experiments to ensure the integrity of the monolayer. In addition to more accurate microanatomy, organoid technology brings an advantage in P-glycoprotein (P-gp)-related studies when compared to traditional Caco-2 culture, as demonstrated by Zhao et al.[

11].

This figure illustrates desirable properties for a cellular monolayer in a dual chamber permeable support system, including cellular diversity, cell shape, and polarization, the presence of microvilli and tight junctions, stable TEER values with low between-replicates variability, reliable expression of cytochrome P450 (CYP450), P-glycoprotein (P-gp), and other important transport molecules. Image created using biorender.com.

For studies focusing on intestinal permeability, the following features (illustrated in

Figure 1) are considered desirable in permeability assays:

The presence of mucin-producing and secretory cells (1); a polarized (2), columnar (3) cellular monolayer and typical microanatomical features of enterocytes such as microvilli (4);

The presence of tight junctions as evaluated through transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (5) and TEER measurements. TEER values should also replicate those measured in vivo (6), with minimal variations between replicates (7). The focus on TEER values can be justified as this method is the only quantifiable variable obtained in real-time during cell culture.

Cell monolayers must be stable (8) for several days to allow for permeability assay experiments. Stability is defined as a <10% decrease in TEER values in 2 days following the plateau state.

The objective of this study was to characterize canine intestinal organoids using the above criteria and compare them to two immortalized cell lines conventionally used for in vitro permeability assays.

Cell shape is crucial for intestinal permeability, reflecting the evolution from an undifferentiated globoid shape to the traditional columnar enterocyte shape seen in differentiated intestinal epithelia. Height measurements of the cells were used to assess the morphology of enterocytes as described above. TEER value measurements were included to investigate cell monolayer stability and integrity[

10]. TEER values were evaluated compared to previously published values obtained employing the Ussing chamber on human intestinal tissue (duodenum, 50-100 Ω.cm

2; large intestine, 300-400 Ω·cm

2)[

12,

13]. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was used to evaluate cell ultrastructure and cell-to-cell adhesion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Canine 3D Enteroid/Colonoid Culture and Monolayer

All protocols were approved by the Iowa State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Ref. IACUC-18-065).

Eleven healthy adult mix-breed canines (8 neutered males, 3 spayed females, median age 2.5 years with a range of 5.0 years) were sampled, producing fifteen organoid cell lines that were derived from various sections of the intestines (3 from the duodenum, 5 from the ileum, and 7 from the colon). The canine colony was housed at the College of Veterinary Medicine of Iowa State University and operated by Jonathan P. Mochel and Karin Allenspach. Intestinal tissues were harvested through endoscopic, laparoscopic, surgical wedge biopsies, or necropsies. Using other donors, necropsy samples consisted of an additional twelve juvenile donor tissues (7 intact males and 5 intact females) that were harvested after euthanasia for unrelated reasons. These tissue samples produced 12 juvenile organoid cell lines (4 from the duodenum, 3 from the ileum, and 5 from the colon). The median age of this group was 30 days (range = 59 days).

The development and maintenance of canine intestinal organoid cultures for this study followed the standardized methodology established by our group in 2022[

14], with some minor adjustments described below. In summary, 3D canine intestinal organoids from the duodenum, ileum, and colon were isolated and cultured from adult stem cells. The tissues were washed, and organoids were isolated according to a standardized protocol[

14]. The EDTA incubation time was 60 minutes, and isolated crypt cells were then co-plated with the rest of the crypt tissues. The cell cultures were subsequently passaged and expanded at least twice before being cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen. Following thawing, the organoids were cultured from the cryopreserved samples and then passaged twice in a 24-well plate to expand the culture for experimental purposes. The expansion media was replaced with differentiation media for the last 5 days of 3D plate growth.

Organoids were plated on a dual-chamber permeable support system (Transwell; Corning, Ref. 3470) following procedures previously standardized by Gabriel et al.[

10]. Organoid media was removed from the plate, and 500 µL of cold Cell Recovery Solution (Corning, Ref. 354253) was added to each well for Matrigel® Matrix (Corning, Ref. 356231) dissolution. The plate was incubated at 4°C for 30 minutes. The suspension was then collected in 15 mL tubes and centrifugated at 750 g at 4°C for 5 minutes. The supernatant was removed with 500 µL of solution left in the tube. Then, 1 mL of TrypLE™ Express (Gibco, Ref. 12604-021) was added and incubated at 37°C in a water bath for 5 minutes. The tube was subsequently mixed by flicking 10 times and incubated for an additional 5 minutes in the water bath. Then, 7 mL of Advanced DMEM/F12 (Gibco; Ref. 12634-010) was added to the culture media to stop the dissociation. Samples were centrifuged at 750 g at 4°C for 5 minutes, and the supernatant was removed. Organoids were suspended in 100 µL of the organoid media and ROCK inhibitor (Y-27632; EMD Millipore Corp.; Ref: SCM075) suspension per one transwell insert.

The organoids were gently pipetted up and down to release the cells from larger clusters, and the suspension was filtered through a 40 µm cell strainer (Fisherbrand; Ref. 223635547) to remove larger clumps. The viable single cells were counted to seed the cells in a concentration of ~75,000 cells per 1 cm2 of the transwell. The transwells were pretreated with 1% Matrigel® Matrix, 1% Collagen I, Rat Tail 3 mg/ml (Gibco, Ref. A10483-01) in organoid media and ROCK inhibitor solution. Each insert was coated with 100 µL of this solution and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Afterward, the excess pretreatment solution was carefully removed from each insert.

The desired concentration of cells (75,000 cells/mL) was seeded in the transwell inserts and gently swirled around in the hood for a stable dispersion of single cells. A total of 700 µL of organoid media with ROCK inhibitor was added to the wells and incubated for 24 hours. After 24 hours, the excess media was removed from the transwells, and 200 µL of media and ROCK inhibitor solution was added to the transwell. Organoids were cultivated on transwells for 13 days. The culture media in transwells was changed every alternative day except during weekends. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) values were measured with Millicell® ERS-2 (Millipore) every other day until the values reached a plateau phase. The integrity of the monolayer was assessed visually using an inverted microscope (Leica Dmi1).

2.2. D Cell Culture

One cryovial of MDCK cells (ATCC) was transferred from liquid nitrogen to a 37°C heat bath for two minutes to thaw. After thawing, cells were transferred to a centrifuge tube with 6 mL cold EMEM (ATCC; 30-2003). The cells were centrifuged at 100 g for five minutes at 4°C and returned to a sterile hood where the supernatant was removed down to 1 mL. The cell pellet was gently resuspended by pipette mixing and transferred evenly to two 25 cm2 flasks with pre-warmed EMEM+10% Fetal Bovine Serum (Corning; 35-010-CV). Flasks were monitored daily to record the confluence of the cell monolayer. The culture media was refreshed every 2-3 days by gently pooling and aspirating the old media with a pipette and replacing it with new, pre-warmed EMEM+10% FBS to discard detached or non-viable shed cells. When the cell monolayer reached ~80% confluence, the cells were passaged in a 1:3 ratio and seeded at roughly 6.67 × 103 cells/cm2.

The culture media was discarded from the flask, and 4 mL of 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco; 25200-056) was added to rinse the remaining media from the flask by gently rocking the solution for 5-10 seconds, removing with a pipette, and then repeating with another 4 mL of trypsin. After rinsing, a final 4 mL of trypsin was added and incubated at 37°C for 10-12 minutes, checking every ~4 minutes under a microscope set at 10x phase contrast to monitor cells as they detach. Once at least 90% of cells were detached and free-floating in the solution, the flask was returned to the hood, and trypsin was deactivated by adding 10 mL of cold EMEM+ 10% FBS. The suspended cells were passed through a pre-wetted 40 μm cell strainer into a centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 100 g for five minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of media. Viable cells were counted under a microscope using a Trypan Blue staining (Sigma; T8154-100ML) with a hemocytometer, and the sample was diluted to the desired concentration of 2.5 x 10⁵ cells/mL. Once diluted, 100 μL of suspended cells were seeded to each Transwell insert, and the plate was gently rotated and checked under a microscope to ensure an even distribution of cells. Finally, 700 μL of warm culture media was added to the basal well, and the Transwell plate was incubated at 37°C. After 24 hours, the apical media was gently aspirated and replaced with 200 μL of warm culture media. The media was refreshed every 2-3 days, and TEER values were recorded every day after initial seeding.

One cryovial of Caco-2 cells (ATCC) was transferred from liquid nitrogen to a 37°C heat beath for two minutes to thaw. Immediately after thawing, cells were transferred to a centrifuge tube with 6 mL of cold DMEM+10%FBS (Gibco; 12634-010, Corning; 35-010-CV). Cells were centrifuged at 100 g for five minutes at 4°C and returned to a sterile hood where the supernatant was removed down to 1 mL. The cells were resuspended by gentle pipette mixing and transferred to one 75 cm2 flask. The culture media was changed every 2-3 days by gently pooling and aspirating the old media with a pipette and replacing it with new, pre-warmed culture media to discard free cells. When cells reached approximately 80% confluence and had formed large cell islands, they were passaged at a 1:2 ratio and seeded at roughly 1.0 x 10⁴ cells/cm2.

The culture media was discarded from the flask, and 4 mL of 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco; 25200-056) was added to rinse the remaining media from the flask by gently rocking the solution for 5-10 seconds and removing with a pipette. After rinsing with media, another 4 mL of trypsin was added and incubated at 37°C for 10-12 minutes until cell detachment was observed. When at least 90% of cells were detached and free-floating in the solution, the flask was returned to the hood, and trypsin was deactivated by adding 10 mL of cold DMEM+ 10%FBS. The suspended cells were passed through a pre-wetted 40 μm cell strainer into a centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 100 g for five minutes at 4°C. The supernatant was discarded, and the cell pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of media. Viable cells were counted under a microscope using a Trypan Blue staining with a hemocytometer, and the sample was diluted to the desired concentration of 2.5 x 10⁵ cells/mL. Once diluted, 100 μL of suspended cells were seeded to each transwell, and the plate was gently rotated and checked under a microscope to ensure an even distribution of cells. After seeding the apical insert, 700 μL of warm culture media was added to the basal well, and the Transwell plate was incubated at 37°C. After 24 hours, the apical media was gently aspirated and replaced with 200 μL of warm culture media. The media was refreshed every 2-3 days, and TEER values were recorded every day after initial seeding for two weeks.

2.3. Histochemical Staining

Organoids were fixed, processed, and stained as previously described[

14]. In short, organoids were submerged in an FAA solution (Formalin-Acetic Acid-Alcohol) for 24 hours and then changed to 70% ethanol. Samples were paraffin-embedded, sectioned (4 µm) onto slides, and deparaffinized/hydrated for staining with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Alcian Blue pH 2.5 (Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, Ames IA).

2.4. Cell Measurement

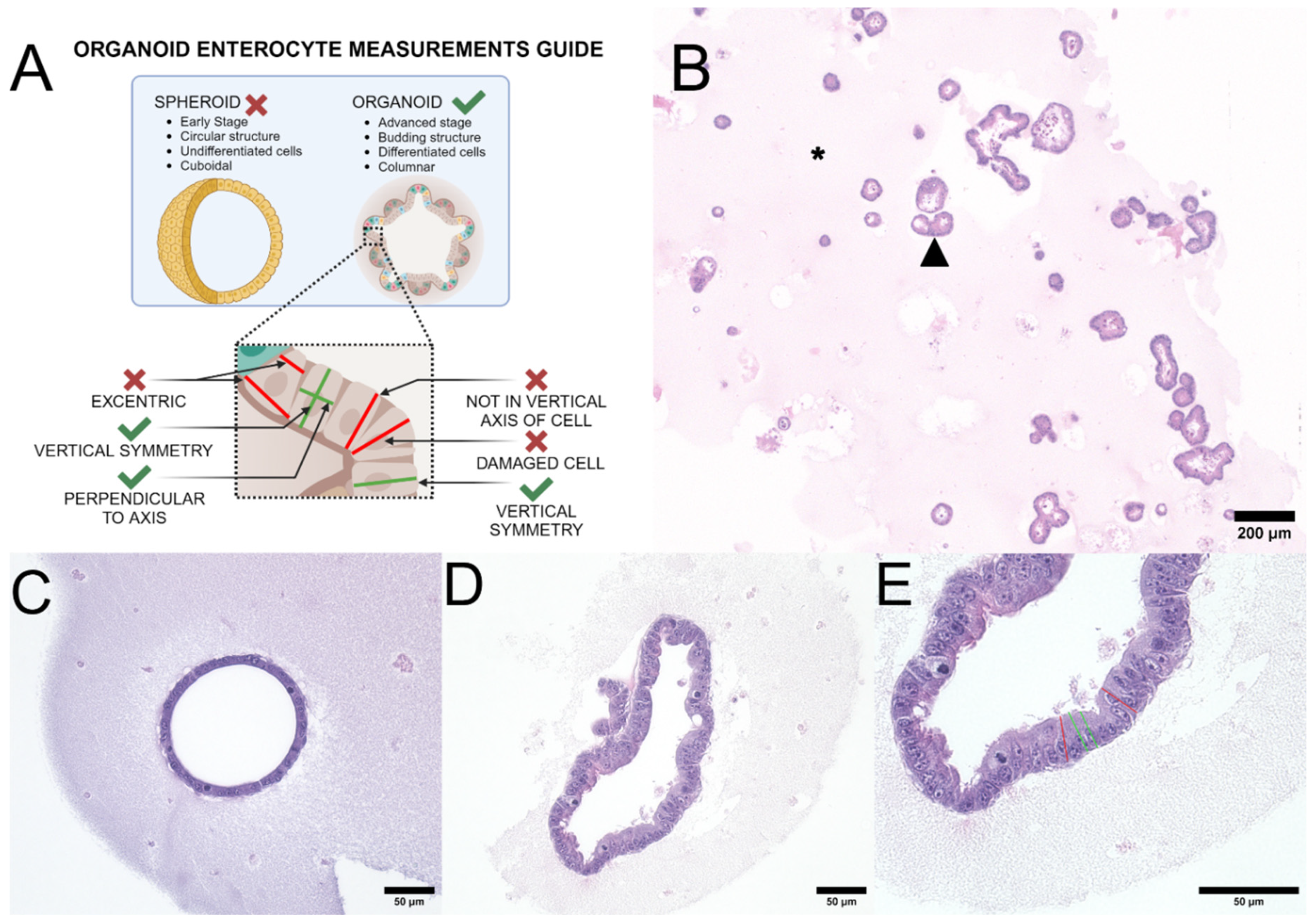

Height measurements were performed on H&E-stained slides in a blinded fashion[

15]. The minimum number of cells required for inclusion in the cohort was set at 100 measurable cells. The guidelines for measuring height are shown in

Figure 2A.

The canine organoid culture included two types: (1) spheroids (at Day 3-5 of culture) and (2) budding organoids (Day 5-7 of culture) (

Figure 2B). Spheroids, which mainly consist of stem cells in the early developmental stage, were not measured at this stage as most cells have not yet undergone terminal differentiation (

Figure 2C). On the other hand, budding organoids, which mainly consist of mature intestinal epithelial cells, were measured for this experiment (

Figure 2D). Any organoids that were damaged after microtome cutting or during the staining process were excluded from the analysis. Additionally, organoids containing cells with smaller nuclei than neighboring cells were also excluded from the cohort to prevent any sectioning plane artifacts or biases (

Figure 2E). Epithelial cells were measured from digital images taken at a 40x objective magnification using an Olympus BX43 microscope. Height measurement parameters were determined in typical budding organoid structures. The height was measured at mid-cell from the apical membrane (at the level of microvilli) to the basal membrane (

Figure 2E). Measurements were performed using ImageJ[

16].

This figure represents the basic rules followed during the study on canine organoid measurements to ensure accurate results.

Figure 2A is a schematic that illustrates the structural differences between early spheroids and late budding organoids, with examples of correct and incorrect enterocyte height measurements in intestinal organoids (

ENT).

Figure 2B is a representative canine colon organoid (

COL) slide, composed of multiple spheroids and organoids in varying states of differentiation, embedded in extracellular matrix. A black arrowhead indicates an individual

COL. The pink material (asterisk) around the organoids is Matrigel, an extracellular membrane matrix. Original objective 4x, H&E stain.

Figure 2C is a representative example of an undifferentiated duodenal spheroid. Spheroids are circular structures composed of undifferentiated cuboidal epithelium, and were excluded from analysis. Original objective 20x, H&E stain.

Figure 2D is an acceptable differentiated budding duodenal organoid. Organoids are budding structures of columnar epithelium morphologically similar to the mucosa of the tissue of origin (in this case duodenum). Original objective 20x, H&E stain.

Figure 2E shows the methods used to measure the 3D organoid cell height; the original objective of 40x (H&E stain). Green lines represent acceptable measurements, while red lines represent cells that were excluded from the analysis as they were not cut along the medial axis. Images were captured using an ECHO Revolution microscope. Illustration and composite created in BioRender.com.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Forty-four canine organoid lines were evaluated. Cell height for each group of organoids (adult duodenum n = 290 cells; juvenile duodenum n = 400 cells; adult ileum n = 459; juvenile ileum n = 300 cells; adult colon n = 687 cells; juvenile colon n = 493 cells) and MDCK (n = 99) and Caco-2 (n = 99) cells were tested for normality using a D’Agostino & Pearson test. All groups except for the MDCK cells were not normally distributed. No outliers were identified using a ROUT method. The cell heights of all groups were compared using a Kruskal-Wallis test with a Benjamini, Krieger, and Yekutieli correction for multiple comparisons (false discovery rate Q = 0.05).

Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) values were measured each day for adult duodenal organoids, MDCK cells, and Caco-2 cells. Means, standard deviation, and coefficient of variance (CV) were calculated from 3 replicate wells per culture type.

All analysis was performed using GraphPad v 10.3.1.

2.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

Sample processing and imaging methods for TEM were performed according to previously described methods[

17].

3. Results

3.1. Canine Organoid Enterocyte Measurements

A Kruskal-Wallis test revealed statistically significant differences in cell height across the 8 groups (P < .001). Measurements of the height of organoid enterocytes derived from different parts of the intestine and different groups (adult

vs. juvenile) are summarized in

Table 1. Mean enterocyte height of adult stem cell-derived organoids from healthy adult dogs differed between intestinal segments: duodenum (14.9 ± 5 µm)

vs. ileum (18.6 ± 5.8 µm),

P < .001; duodenum

vs. colon (20.55 ± 5.0 µm),

P < .001; and ileum

vs. colon,

P < .001. Mean enterocyte height was increased in adult-derived organoid cultures compared to juvenile-derived cultures (duodenum: adult

vs. juvenile, 14.9 ± 4.9 µm

vs. 10.9 ± 3.0 µm,

P < .001; ileum: adult

vs. juvenile, 18.6 ± 5.8 µm

vs. 14.0 ± 4.4 µm,

P < .001; colon: adult

vs. juvenile, 20.55 ± 5.0 µm

vs. 18.3 ± 4.4 µm,

P < .001. MDCK cells were shorter than all other cell types, including Caco-2 cells (

P < .001). Caco-2 cells were shorter than adult ileum organoids and both adult and juvenile colon organoids (

P < .001). Caco-2 cells were the same height as adult duodenum organoids and juvenile ileum organoids (

P > .05), and taller than juvenile duodenum organoids (

P < .001).

Table 1 compares the height measurements of enterocytes in canine organoids derived from adult and juvenile duodenum, ileum, and colon, as well as Caco-2 and MDCK cells. Different letters between median cell heights in each group indicate statistical significance P < .001.

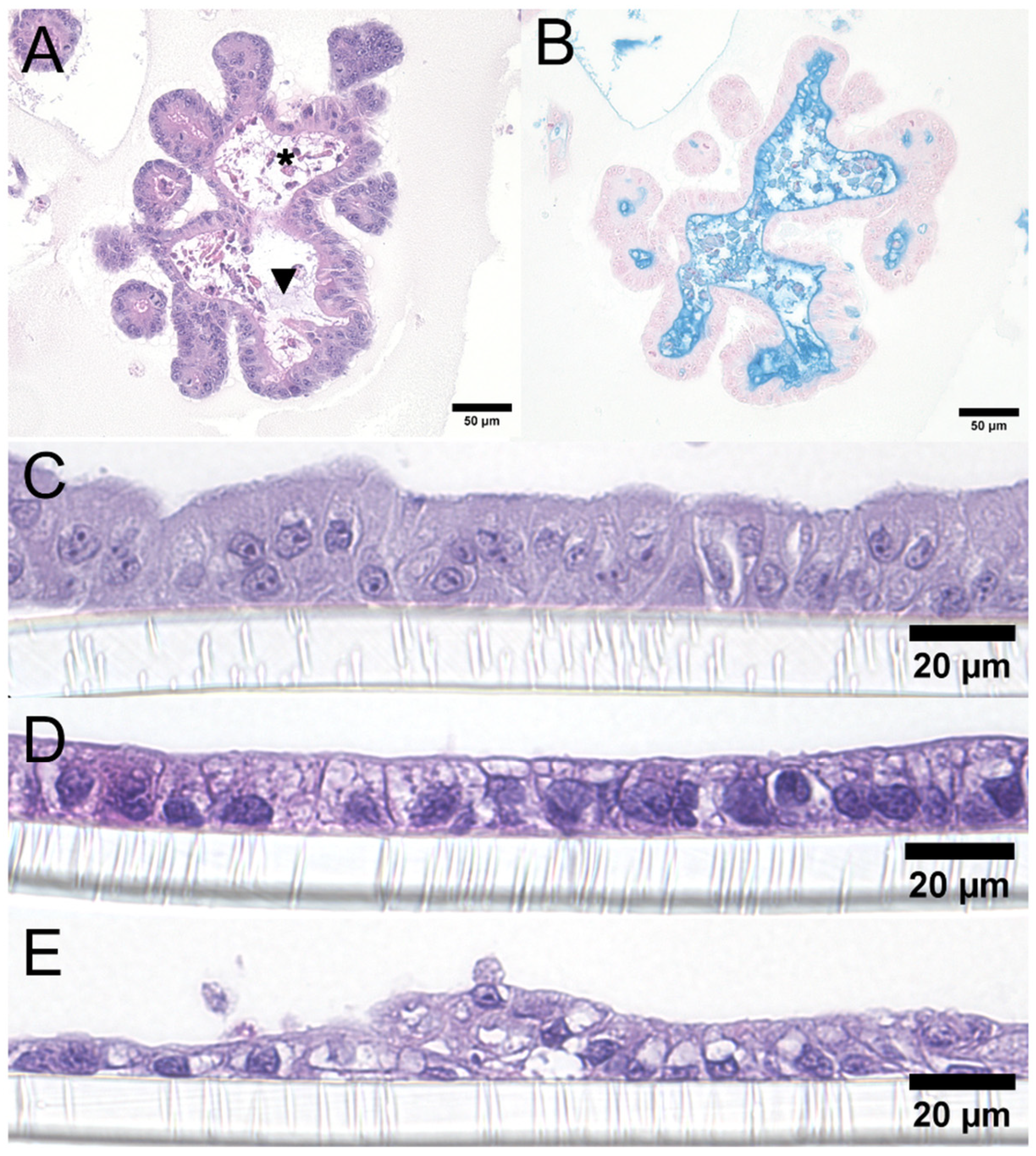

3.2. Cell Morphology and Immunofluorescence

ENT and

COL in 3D culture frequently had luminal mucin production (

Figure 3A), which was demonstrated with an Alcian Blue pH 2.5 histochemical stain (

Figure 3B). The cell shapes after transwell plating were columnar for canine

ENT (

Figure 3C), cuboidal for Caco-2 cells (

Figure 3D), and polygonal to flattened for MDCK cells (

Figure 3E).

Morphology of canine intestinal organoids (A-B). Representative canine COL in 3D culture with mucin production, characterized by wispy, basophilic, intraluminal material (A, black arrowhead). The COL lumen with sloughed cellular debris is indicated by an asterisk. Original objective 20x; H&E. Representative canine COL in 3D culture with intraluminal mucin highlighted in bright blue with an Alcian Blue pH 2.5 histochemical stain (B); original objective 20x. Comparison of 2D transwell-grown monolayers (C-E) between a representative canine duodenal ENT monolayer and conventional 2D cell lines (Caco-2 and MDCK). Strictly columnar shapes can be observed in duodenum organoids (C), while more cuboidal shapes are present in Caco-2 (D), and polygonal shapes creating a flattened to piling arrangement in MDCK cells (E). Original objective 40x, H&E. Images were captured using an ECHO Revolution microscope. Composite created in BioRender.com.

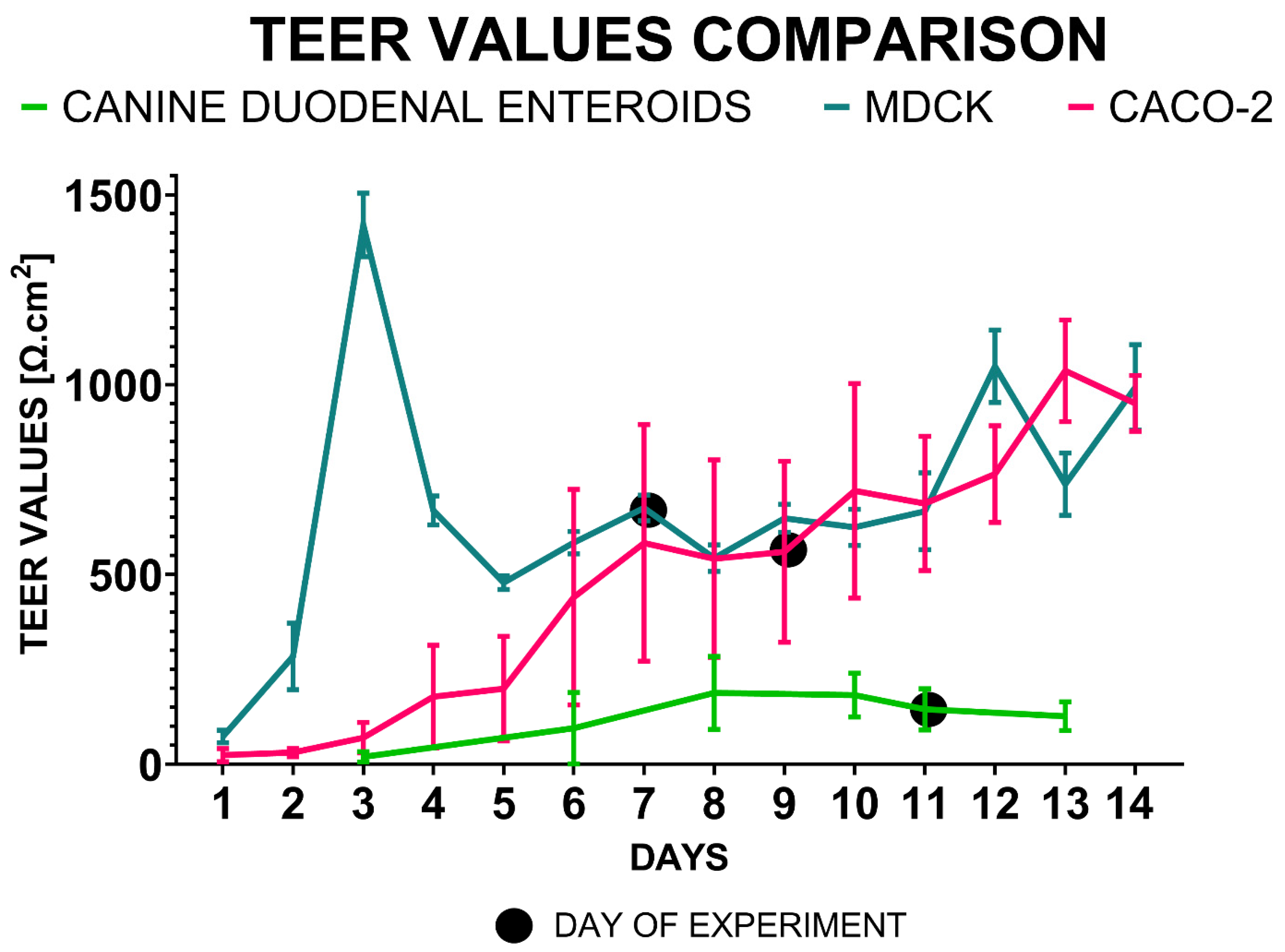

3.3. Transepithelial Electrical Resistance (TEER) Measurements

TEER values measured in the dual chamber system using a volt/ohmmeter were compared in MDCK, Caco-2, and canine duodenal

ENT cultures (

Figure 4).

MDCK TEER values demonstrated relatively low between-replicates variability (CV% = 48.4%), with a peak value on Day 3 (1420 ± 84 Ω.cm2, N=12). The TEER values decreased by 65% to 478 ± 18 Ω.cm2 on Day 5, and the culture was ready for a permeability assay on Day 7 (675 ± 34 Ω.cm2). By Day 8, TEER values had reached 543 ± 35 Ω.cm2, and continued to rise slowly until Day 11 (666 ± 34 Ω.cm2).

The Caco-2 TEER values did not exhibit an initial peak but rather consistently increased for 14 days throughout the experiment. However, there was a relatively high variance observed (CV = 69.7%). The Caco-2 culture was considered ready for use in permeability experiments on Day 9 (559 ± 238 Ω.cm2, N=11). On Day 10, the TEER measurements showed a value of 720 ± 283 Ω.cm2. The highest TEER values for the Caco-2 cultures were observed on Day 13 after seeding (1036 ± 134 Ω.cm2).

During the 13 days of culture, canine duodenal organoid TEER values increased more slowly with a lower variance (CV = 49.8%), similar to the MDCK cultures. The ENT monolayers in the dual-chamber system reached the plateau phase on Day 10 (182 ± 58 Ω.cm2, N=79). Therefore, the experiment was conducted on Day 11 (145 ± 54 Ω.cm2). The peak TEER values for the canine duodenal ENT monolayer were measured on Day 8, with an average of 188 ± 96 Ω.cm2. Monolayer stability was lowest in Caco-2 cells (28.7% change), followed by MDCK (19.6%), while canine ENTs remained most stable (12.8%) 24 hours after experiment initiation.

The TEER value time-course was observed over a period of two weeks as TEER values were measured for monolayer cultures (mean TEER +/- SD) in a dual chamber permeable system derived from canine duodenal ENTs, MDCK, and Caco-2 cells.

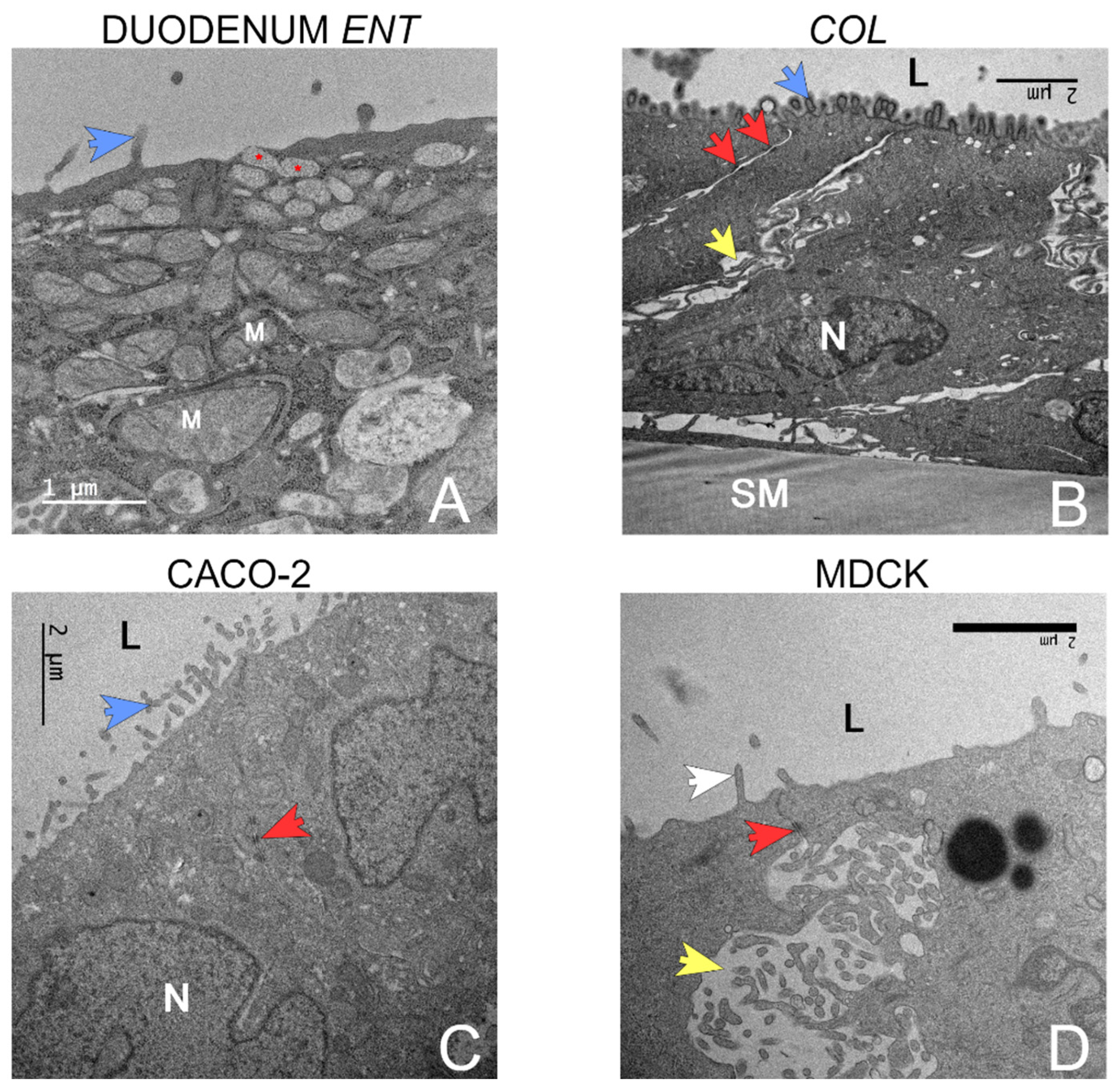

3.4. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

TEM images were captured from the canine organoids (duodenum and colon), Caco-2, and MDCK monolayer samples (

Figure 5). The duodenal

ENT monolayer was composed of columnar cells growing in monolayers on the permeable support membrane with sporadic overgrowth into two layers. Several cells were observed producing vacuoles with mucin-like contents (

Figure 5A), likely representing goblet cell differentiation. Each cell featured microvilli at the apical membrane and exhibited strong attachment to the permeable support with no visible tears in the membrane. The colon organoids displayed similar features, such as polarization, desmosomes, and microvilli brush border formation on the apical membrane (

Figure 5B).

Caco-2 cells (

Figure 5C) were cuboidal, with stronger overgrowth visible in certain regions of the monolayer creating up to five cell layers on top of each other. Tight junctions and intercellular spaces appeared smaller than in the organoid model. Detachments from the permeable support membrane were also noticed in several areas of the transwell. MDCK cells expressed a polygonal shape, and it was difficult to determine their cell borders. The MDCK cells were frequently detached from the permeable support membrane and had larger intercellular spaces (

Figure 5D). Overgrowth into several layers of cells was present in over 50% of the area of the membrane. MDCK cells had fewer microvilli (

Figure 5D).

Representative Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Images. All cultures were imaged on a 2D transwell membrane. A – Duodenal organoids with small vacuoles releasing mucin-like material at the apical surface (red asterisk) near the lumen (L). Mitochondria are indicated by (M). The blue arrow indicates apical microvilli. B – Colon organoids displayed polarization, the basolateral border was defined by a permeable support membrane (SM) and the apical border by the organoid lumen (L). Microvilli (blue arrow) project from the apical membrane into the lumen. The columnar cells contain a centrally to basolaterally located nucleus (N). Cells are separated by paracellular spaces (yellow arrow) anchored by desmosomes (red arrow). C – Caco-2 cells. Note the nucleus (N), brush border microvilli (blue arrow) on the luminal surface (L), and desmosomes (red arrow). D – MDCK cells. The apical membrane brush border has rare microvilli (blue arrow) near the lumen (L). Note the wide paracellular spaces (yellow arrow) and desmosome (red arrow). Composite created in BioRender.com.

4. Discussion

In this study, canine ENT and COL were compared to MDCK and Caco-2 conventional cell cultures. Based on microscopic morphology and TEER as a measurement of monolayer stability, canine ENT and COL more accurately recapitulated in vivo intestinal tissue compared to the immortalized cell lines, suggesting a potential advantage of using canine intestinal organoid cultures in 2D biological model systems.

Both adult and juvenile canine organoid enterocyte cell heights were higher than MDCK cell heights, more accurately recapitulating the

in vivo appearance of intestinal epithelium. Adult canine organoid enterocyte cell heights were higher than both MDCK and Caco-2 cell heights, with the exception of adult duodenal organoids. In 2D culture, the tall cuboidal to columnar morphology of adult organoid enterocytes appeared maintained and were subjectively higher than MDCK cells. MDCK cells had a flattened phenotype observed both with light microscopy and TEM. Adult canine intestinal organoid cell heights were higher than those derived from juvenile individuals for every intestinal segment evaluated (duodenum, ileum, and colon), which is consistent with a previous study that measured these parameters in adult and juvenile canine intestinal tissue samples[

18].. Similar findings were described in a human sample population in 1988 when Thompson et al. reported shorter enterocytes in infants compared to healthy adult intestinal cells[

19]. These findings support the use of healthy adult canine intestinal samples, which can be obtained via endoscopy, for adult stem cell isolation and organoid generation. These results also suggest that adult canines, which are more readily available from established colonies or from clinical patient populations as compared to neonatal or juvenile canines, may be more optimal for organoid production and

in vitro assays. Furthermore, these organoids can then be compared to histologic samples obtained from the matching donor before and after

in vivo treatment.

Cell and organoid histology provided insights into cell shape via measurements of cellular height and morphology, (i.e. mucin production as previously reported[

10]). Representative organoids from each intestinal segment demonstrated luminal mucus. Goblet cell and enteroendocrine cell differentiation have been previously demonstrated in canine

ENT cultures[

8]. TEM also demonstrated apical vacuoles containing mucin-like material in organoid cells, consistent with the observation of mucin production by

ENTs in this experiment. Cell polarization was determined by observing columnar morphology with basally located nuclei on light microscopy, and tight junctions and apical microvilli with basally located nuclei using TEM. Tight junctions, desmosomes, and apical microvilli were present in all three cultures; however, MDCK cells have subjectively fewer apical microvilli and wider intercellular spaces consistent with their polygonal morphology, frequent transwell detachment, and tendency to pile.

To assess monolayer integrity in the 2D culture system, cell monolayers were grown for 13-14 days, with the timing determined based on published criteria for culture readiness[

20,

21,

22]. MDCK cells on a permeable support system are considered ready for permeability assays as early as Day 3 to 4[

20,

21] of culture, following an initial TEER spike and transition to a stationary growth phase[

2]. For our experiments, we deemed the culture ready for evaluation on Day 7, marked by the first positive TEER value increase.

Caco-2 monolayers are typically ready for permeability testing after reaching a plateau phase, with TEER values above 300 Ω·cm

2 indicating acceptable monolayer integrity[

22]. In this study, the evaluation for Caco-2 was conducted on Day 9, one day after the plateau TEER values were achieved. For canine organoid cultures, readiness for permeability experiments was determined by reaching the plateau phase, setting Day 11 for assessment.

Canine

ENTs (145 ± 54 Ω·cm

2) closely approximated reported values for human small and large intestines (50-100 Ω·cm

2 and 300-400 Ω·cm

2, respectively)[

12,

13]. By comparison, the conventional cell lines (Caco-2 and MDCK) did not approximate TEER values reported for human small and large intestines. While these cell lines might not be expected to replicate small intestine, considering Caco-2 cells are derived from human colonic cells and MDCK cells are derived from canine kidney, Caco-2 cells grown in culture often exhibit properties of small intestinal epithelium[

23,

24]. Additionally, the TEER variance was higher in Caco-2 compared to MDCK and canine

ENTs, suggesting that monolayer stability was lowest in Caco-2 cells.

Overall, these findings support the use of canine intestinal organoids cultures in a 2D dual chamber system when compared to conventional 2D cell cultures. However, functional assessments of these cultures are needed to validate and optimize their use in permeability assay evaluations.

4.1. Study Limitations

While canine organoid cultures have potential advantages highlighted in this study, several limitations should be noted. The lack of standardization for canine intestinal organoid cultures in both 3D and 2D systems has been previously mentioned, and our group has made efforts to streamline standardized culture techniques, now published in two manuscripts[

10,

14]. Additionally, organoid culture upkeep is relatively expensive compared to conventional permeability assay cultures. This cost can be partially mitigated by using 2D L-WRN cell cultures that produce essential growth factors for the culture of organoids, thus eliminating the need for expensive recombinant growth factors such as Wnt-3a, R-spondin-3, and Noggin[

25]. A significant limitation of this study is the small number of organoid cell lines used in the experiments. The findings represent a preliminary effort to compare histological and semi-functional features (e.g., TEER) across cell lines used for intestinal permeability assessment, and further validation of this system is required. Additionally, the study does not include a comparison of apparent permeability estimates (Papp) between

in vitro models and

in vivo data, as this was beyond the scope of the current investigation. Further data supporting the use of canine organoid technology in veterinary drug development were published by our group elsewhere[

26].

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, 3D canine ENT and COL were characterized via light microscopy, followed by culture in a 2D dual chamber system to compare the biological relevance of various cell lines used in 2D biological model systems. The enterocytes of adult canine ENT and COL grown in a 2D monolayer maintained their columnar shape. Like Caco-2 and MDCK cells, they also formed tight junctions and desmosomes, which was supported by TEER measurements which more closely approximated the reported in vivo human intestinal values. Duodenal ENTs grown in 2D appeared to have mucus production, which offers an advantage over Caco-2 and MDCK cells. The comparison between organoid 2D monolayers and 2D conventional cell cultures suggests the potential of the organoid model to be used in permeability assays in preclinical studies. Future steps include assessment of functional properties of the canine organoid monolayers, comparison to the in vivo results, and further repeated assessment of other cell lines used for in vitro intestinal modeling.

Supplemental Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org. All original light microscopy and scanning electron microscopy images are provided.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Vojtech Gabriel, Karin Allenspach and Jonathan Mochel; Data curation, Vojtech Gabriel, Abigail Ralston, Christopher Zdyrski, Hannah Wickham, Addison Lincoln, Todd Atherly, Dipak Sahoo and David Meyerholz; Formal analysis, Megan Corbett, Vojtech Gabriel, Vanessa Livania, David Diaz-Regañón and Christopher Zdyrski; Funding acquisition, Karin Allenspach and Jonathan Mochel; Investigation, Vojtech Gabriel, Abigail Ralston, Christopher Zdyrski, Hannah Wickham, Todd Atherly and Dipak Sahoo; Methodology, Vojtech Gabriel, Vanessa Livania, David Diaz-Regañón, Abigail Ralston, Christopher Zdyrski, Dongjie Liu, Sarah Minkler, Sichao Mao, Hannah Wickham, Todd Atherly and David Meyerholz; Resources, Maria Merodio and Karin Allenspach; Supervision, Karin Allenspach and Jonathan Mochel; Validation, Vojtech Gabriel and Christopher Zdyrski; Visualization, Vojtech Gabriel; Writing – original draft, Vojtech Gabriel; Writing – review & editing, Megan Corbett, Christopher Zdyrski, Karel Paukner, David Meyerholz, Karin Allenspach and Jonathan Mochel. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NSF SBIR Phase I 18-550: Improving In Vitro Prediction of Oral Drug Permeability and Metabolism Using a Novel 3D Canine Organoid Model (NSF: award number 1912948) and J.P.M. ISU Startup (FSU_0000022) funds.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional animal care and use committee of Iowa State University (protocol code IACUC-18-065, approved 11-May-2018).

Data Availability Statement

The data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Jodi Smith for the assistance in tissue collection. We are also thankful to the Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory at Iowa State University employees for their relentless work processing our slides. We thank Tracey Stewart, a manager of Light and Electron Microscopy Roy J. Carver High-Resolution Microscopy Facility at Iowa State University, for her help and support through this project.

Conflicts of Interest

K. Allenspach is a co-founder of LifEngine Animal Health and 3D Health Solutions Inc. She is a consultant for Ceva Animal Health, LifeDiagnostics, Antech Diagnostics, and Mars. J.P. Mochel is a co-founder of LifEngine Animal Health and 3D Health Solutions Inc. Dr. Mochel is a consultant for Ceva Santé Animale, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dechra Ltd and Ethos Animal Health.C. Zdyrski is an employee of 3D Health Solutions Inc.A. Ralston was an employee of 3D Health Solutions Inc.Other authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare.

References

- König, J.; Wells, J.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Human Intestinal Barrier Function in Health and Disease. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2016, 7, e196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, D.A. Variability in Caco-2 and MDCK cell-based intestinal permeability assays. J Pharm Sci. 2008, 97, 712–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fogh, J.; Fogh, J.M.; Orfeo, T. One hundred and twenty-seven cultured human tumor cell lines producing tumors in nude mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1977, 59, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaush, C.R.; Hard, W.L.; Smith, T.F.; Read, W.O. Characterization of an established line of canine kidney cells (MDCK). Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1966, 122, 931–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, D.A. Application of method suitability for drug permeability classification. AAPS J. 2010, 12, 670–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mochel, J.P.; Jergens, A.E.; Kingsbury, D.; Kim, H.J.; Martín, M.G.; Allenspach, K. Intestinal Stem Cells to Advance Drug Development, Precision, and Regenerative Medicine: A Paradigm Shift in Translational Research. AAPS Journal. 2018, 20, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T.; Vries, R.G.; Snippert, H.J.; et al. Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche. Nature. 2009, 459, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandra, L.; Borcherding, D.C.; Kingsbury, D.; et al. Derivation of adult canine intestinal organoids for translational research in gastroenterology. BMC Biol. 2019, 17, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drost, J.; Clevers, H. Translational applications of adult stem cell-derived organoids. Development. 2017, 144, 968–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, V.; Zdyrski, C.; Sahoo, D.K.; et al. Canine Intestinal Organoids in a Dual-Chamber Permeable Support System. Journal of Visualized Experiments 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zeng, Z.; Sun, J.; et al. A Novel Model of P-Glycoprotein Inhibitor Screening Using Human Small Intestinal Organoids. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017, 120, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biological Transport Phenomena in the Gastrointestinal Tract: Cellular Mechanisms. In Transport Processes in Pharmaceutical Systems; CRC Press, 1999; pp. 163–200. [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, B.; Kolli, A.R.; Esch, M.B.; Abaci, H.E.; Shuler, M.L.; Hickman, J.J. TEER Measurement Techniques for In Vitro Barrier Model Systems. J Lab Autom. 2015, 20, 107–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, V.; Zdyrski, C.; Sahoo, D.K.; et al. Standardization and Maintenance of 3D Canine Hepatic and Intestinal Organoid Cultures for Use in Biomedical Research. J Vis Exp 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerholz, D.K.; Beck, A.P. Principles and approaches for reproducible scoring of tissue stains in research. Lab Invest. 2018, 98, 844–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C.A.; Rasband, W.S.; Eliceiri, K.W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdyrski, C.; Gabriel, V.; Gessler, T.B.; et al. Establishment and characterization of turtle liver organoids provides a potential model to decode their unique adaptations. Communications Biology 2024, 7, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Regañón, D.; Gabriel, V.; Livania, V.; et al. Changes of Enterocyte Morphology and Enterocyte: Goblet Cell Ratios in Dogs with Protein-Losing and Non-Protein-Losing Chronic Enteropathies. Vet Sci. 2023, 10, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, F.M.; Catto-Smith, A.G.; Moore, D.; Davidson, G.; Cummins, A.G. Epithelial growth of the small intestine in human infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998, 26, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irvine, J.D.; Takahashi, L.; Lockhart, K.; et al. MDCK (Madin-Darby canine kidney) cells: A tool for membrane permeability screening. J Pharm Sci. 1999, 88, 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cereijido, M.; Robbins, E.S.; Dolan, W.J.; Rotunno, C.A.; Sabatini, D.D. Polarized monolayers formed by epithelial cells on a permeable and translucent support. J Cell Biol. 1978, 77, 853–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Breemen, R.B.; Li, Y. Caco-2 cell permeability assays to measure drug absorption. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2005, 1, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artursson, P. Cell cultures as models for drug absorption across the intestinal mucosa. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 1991, 8, 305–330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hilgendorf, C.; Spahn-Langguth, H.; Regårdh, C.G.; Lipka, E.; Amidon, G.L.; Langguth, P. Caco-2 versus Caco-2/HT29-MTX Co-cultured Cell Lines: Permeabilities Via Diffusion, Inside- and Outside-Directed Carrier-Mediated Transport. J Pharm Sci. 2000, 89, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanDussen, K.L.; Sonnek, N.M.; Stappenbeck, T.S. L-WRN conditioned medium for gastrointestinal epithelial stem cell culture shows replicable batch-to-batch activity levels across multiple research teams. Stem Cell Res. 2019, 37, 101430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahoo, D.K.; Martinez, M.N.; Dao, K.; et al. Canine Intestinal Organoids as a Novel In Vitro Model of Intestinal Drug Permeability: A Proof-of-Concept Study. Cells. 2023, 12, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).