1. Introduction

Chronic non-healing wounds represent an increasing challenge in the aging populations of industrialized nations, often resulting from multifactorial etiologies. Chronic wounds, typically defined as wounds that fail to demonstrate significant healing progress within three months, pose a substantial challenge to modern medicine. According to Körber et al., chronic wounds in the lower extremities frequently arise as complications of venous, arterial, or diabetic diseases [

1]. In Germany, the prevalence of chronic wounds is estimated to be 2–3 million individuals, with leg ulcers affecting 0.7% of the general population and over 3.38% of individuals aged ≥ 80 years [

2]. Chronic venous ulcers alone account for a substantial socio-economic burden, consuming approximately 2% of the national healthcare budget, with an average annual treatment cost of €6,600 per patient [

3,

4,

5]. Effective management of chronic wounds is particularly challenging against the backdrop of increasing healthcare economization and cost containment. Optimal wound care necessitates a multifaceted approach that combines etiological treatments with appropriate local wound management. The selection of therapy is guided by factors such as wound size, location, exudate levels, and microbial colonization. Moist wound healing, the current gold standard, aims to convert chronic wounds into acute wounds to facilitate granulation and re-epithelialization [

6].

However, certain wounds remain unresponsive or develop critical bacterial colonization despite conventional therapies, necessitating alternative treatment modalities. Biological treatment of chronic wounds, particularly biosurgery utilizing live

Lucilia sericata larvae, has garnered renewed attention. Initially described during the European wars of the 19th and 20th centuries, biosurgery declined in popularity with the advent of antibiotics, but was rediscovered in the 1980s due to increasing antibiotic resistance and the rising prevalence of chronic wounds. Larval secretions and excretions have demonstrated the ability to debride necrotic tissue, eliminate bacteria, and stimulate granulation, rendering biosurgery a valuable therapeutic option [

7].

Despite its efficacy, biosurgery presents several limitations. Patients frequently experience aversion or dysesthesia due to the visible movement of larvae on wounds [

8]. The distinctive, unpleasant odor associated with larval excretions can impair compliance, while logistical challenges, such as the production, storage, and timely delivery of live larvae, further complicate its implementation. Biosurgery typically serves as a preparatory step in wound management, necessitating a transition to conventional therapies for complete healing. Contraindications such as coagulopathies, proximity to large vessels or body cavities, and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections limit its applicability [

9].

Given these challenges, research has focused on isolating and examining the individual components of

Lucilia sericata larvae for their therapeutic potential. Studies have demonstrated that larval components exhibit beneficial effects on wound healing, suggesting their potential as an alternative to live larval therapy [

10].

The objective of this study was to test a sterile, storable larval extract with comparable efficacy to live larvae for its effectiveness and safety, but without associated disadvantages. A larval extract can be applied as a conventional topical agent, minimizing odors, mitigating patient discomfort, and enabling treatment to continue until complete wound closure.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Development of a Lyophilized Maggot Extract

In accordance with the EU Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) guidelines for human and veterinary medicinal products, a sterile lyophilized extract of

Lucilia sericata larvae was developed (Larveel

®, Alpha-Biocare GmbH, Düsseldorf) (

Figure 1A). Third-instar larvae produced under GMP conditions for pharmaceutical excipients were utilized for extract preparation. The larvae were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, homogenized with pharmaceutical-grade water to form a uniform emulsion, and subjected to thermal treatment at temperatures exceeding 60°C. Following sedimentation and filtration, a sterile-filtered ultrafine filtrate was obtained. The filtrate was subsequently transferred into glass vials and lyophilized, followed by γ-irradiation for sterilization. Prior to application, the extract was reconstituted in 2 ml of physiological saline. The safety of the extract was evaluated using the HET-CAM test, dermatological skin tests, pyrogen tests (rabbit test, LAL assay, and monocyte activation test), and in vitro toxicity assays, all of which indicated an absence of toxic or allergic reactions.

2.2. Application of Lyophilized Maggot Extract in Patients with Chronic Wounds

The extract was employed in individual therapeutic trials for chronic, therapy-resistant wounds following ethical approval by the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf Medical Faculty. The patients provided informed consent for treatment with Larveel®, wound exudate sampling, and scientific data generation. Ten patients with chronic wounds were included based on the following criteria:

Chronic leg ulcers

Refractory to treatment for at least three months

No underlying consumptive diseases (e.g., malignancies)

A three-week pretreatment phase with stage-appropriate wound care demonstrated no significant improvement

Following informed consent, the patients underwent the following protocol:

Comprehensive clinical and wound-specific history

Standardized photo documentation

Wound exudate collection

Microbiological sampling

Application of L. sericata extract

Dressing with sterile wound coverings

Exudate samples were collected prior to treatment initiation and at weekly intervals thereafter to analyze potential wound-healing mediators. For each 10 cm² wound surface, one vial of extract reconstituted in 0.9% saline was applied. Following a five-minute drying period, sterile dressings comprising nonadhesive gauze, gauze compresses, and elastic wraps were applied. Dressing changes were performed every other day, either independently or with caregiver assistance. Weekly clinical evaluations, including photographic documentation and adverse effect monitoring (e.g., pain), were conducted at the interdisciplinary ulcer clinic of the Dermatology Department, University Hospital Düsseldorf. The treatment regimen was maintained for a maximum duration of eight weeks (

Figure 1B). Fifty percent of the patients received treatment thrice weekly at the clinic. Four patients managed dressing changes twice weekly at home with a weekly clinic visit. One patient independently performed all dressing changes.

2.3. Patient Demographics and Wound Characteristics

The study cohort comprised 10 patients (mean age, 66 years for females and 74 years for males). Ulcer duration ranged from three months to > three years, with a conservative mean duration of 15 months.

Table 1.

Overview of the treated patients. The table shows an overview of age, sex, type of wounds and their duration and duration of treatment with maggot extract. Average age of the patients: ♀ = 66 years, ♂ = 74 years, ♀+♂ = 70 years.

Table 1.

Overview of the treated patients. The table shows an overview of age, sex, type of wounds and their duration and duration of treatment with maggot extract. Average age of the patients: ♀ = 66 years, ♂ = 74 years, ♀+♂ = 70 years.

| Patient |

Sex |

Age (years) |

Wound

Type |

Wound

duration |

Treatment

duration (weeks) |

Treatment |

| 1 |

♀ |

46 |

Venous |

12 months |

8 |

Clinic |

| 2 |

♀ |

72 |

Venous |

12 months |

7 |

Clinic |

| 3 |

♀ |

74 |

Venous |

6 months |

2 |

Clinic |

| 4 |

♂ |

84 |

Venous |

12 months |

2 |

Clinic |

| 5 |

♂ |

78 |

arterial and venous |

18 months |

8 |

Patient/clinic |

| 6 |

♂ |

65 |

Venous |

24 months |

8 |

Patient/clinic |

| 7 |

♀ |

61 |

postoperative |

3 months |

8 |

Clinic |

| 8 |

♀ |

79 |

Venous |

36 months |

8 |

Clinic |

| 9 |

♂ |

73 |

Arterial |

3 months |

7 |

Patient/clinic |

| 10 |

♂ |

72 |

Venous |

24 months |

8 |

Patient/clinic |

2.4. Exudate Collection from Ulcers

Following dressing removal, the wounds were irrigated with sterile saline and dried. Saline was applied for two minutes, then aspirated into syringes. Samples were centrifuged at 500 × g for five minutes at 4°C to remove cells and debris, filtered through 0.45 µm and 0.22 µm syringe filters, and stored in liquid nitrogen.

2.5. Bacterial Colonization Analysis

Swab samples were obtained from the wound edges and center prior to treatment initiation and biweekly thereafter. Bacterial identification and resistance testing were performed at the Institute of Medical Microbiology and Hospital Hygiene, Düsseldorf. The isolates were cultured for subsequent analysis.

2.6. Native Larval Secretions and Extracts

Excretions/secretions (ES) from larvae were prepared according to the protocol described by Barnes et al. [

11]. Briefly, third-instar larvae were incubated in demineralized water at 30°C, ES was centrifuged at 7,826 × g for five minutes, filtered (0.22µm) and stored in liquid nitrogen.

2.7. Effect on Bacterial Biofilms

The extract’s effect on bacterial biofilm formation was evaluated using methods described by van der Plas et al. and O’Toole and Kolter [

12,

13]. Biofilms were formed on microtiter plates containing

S. aureus (MSSA and MRSA),

S. pyogenes, and

P. mirabilis reference strains. Biofilm density was quantified photometrically at 570 nm following crystal violet staining.

2.8. Effect on Bacterial Growth

Bacterial isolates and reference strains were cultured with maggot extract and piperacillin/tazobactam, respectively. Growth inhibition was assessed by measuring the optical density (600 nm) after 24 h of incubation.

3. Results

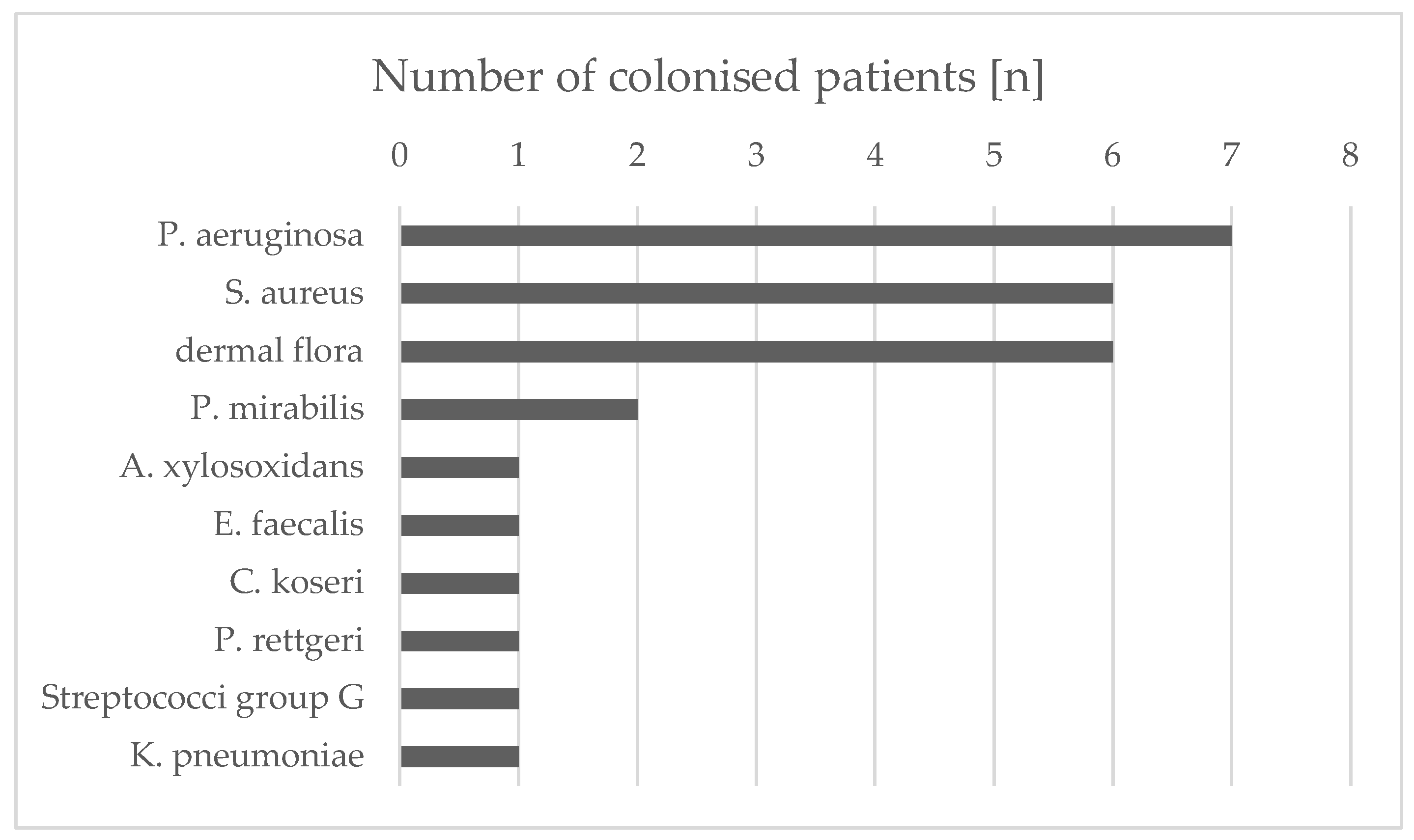

3.1. Isolated Bacterial Species and Effects of Maggot Extracts on Bacterial Colonization In Vivo

The wounds of all patients were permanently or intermittently populated by various bacterial species (

Figure 2). Differentiation of isolates from the same species was based on antibiograms. The most commonly isolated bacterial species were

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (7/10 wounds),

Staphylococcus aureus (6/10 wounds), and

Proteus mirabilis (2/10 wounds) (

Table 2). All

S. aureus isolates were methicillin sensitive (MSSA). The species

Achromobacter xylosoxidans,

Enterococcus faecalis,

Citrobacter koseri,

Providencia rettgeri, Group G streptococci and

Klebsiella pneumoniae were each isolated only from wounds of one patient. In addition to these single and multiple findings, the smears included (in part temporal) other bacterial species that were germs of the normal dermal flora and therefore not used for further analysis and assessment. Essentially, a continuous decrease in the bacteria colonizing the wound could be detected after treatment with maggot extract. After only two weeks of treatment, for example, in patient 1,

A. xylosoxidans and

E. faecalis, could be found neither at the edge of the wound nor in the middle of the wound. This condition persisted until the last sampling after six weeks. Interestingly, no significant differences were found between the bacterial colonization of the wound margin and the wound center (

Table 2). The initial

P. aeruginosa isolate from patient 3 was found to be resistant to three out of four lead antibiotics (acylureidopenicillins, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, and quinolones), but was sensitive to all carbapenems tested and was therefore classified as 3MRGN (multidrug-resistant gram-negative rods). The treatment of the patient with maggot extract was discontinued in week 3 in favor of antibiotic therapy so that no further samples could be taken. At the beginning of treatment in the fourth patient, the treated wound was colonized with

P. aeruginosa. Owing to an increase in colonization, systemic antibiosis was initiated. In all other patients, a decrease in wound colonization by

S. aureus was detected. The decrease in colonization could also be correlated with improved clinical findings. A detailed overview of wound colonization during therapy is presented in

Table 2.

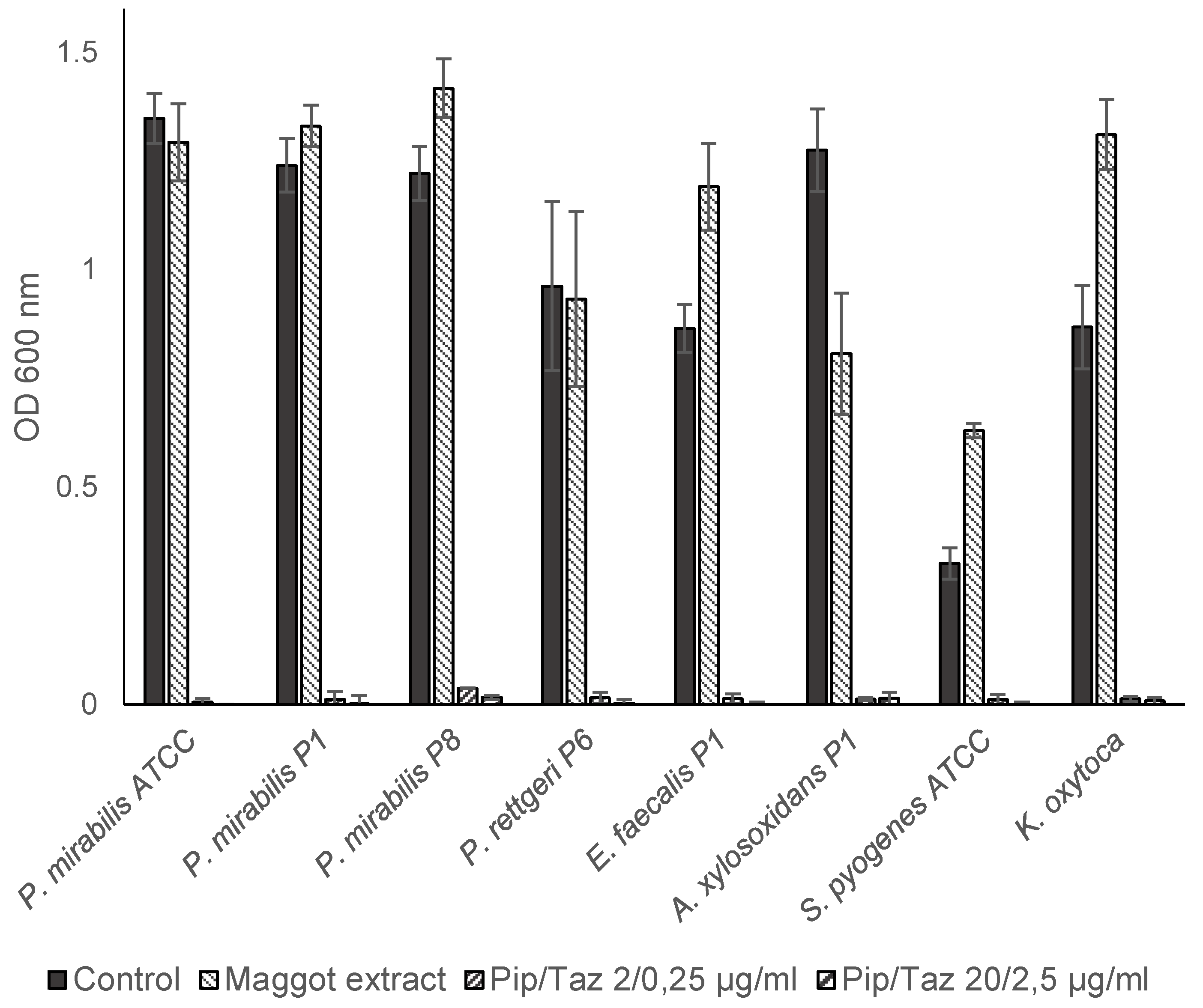

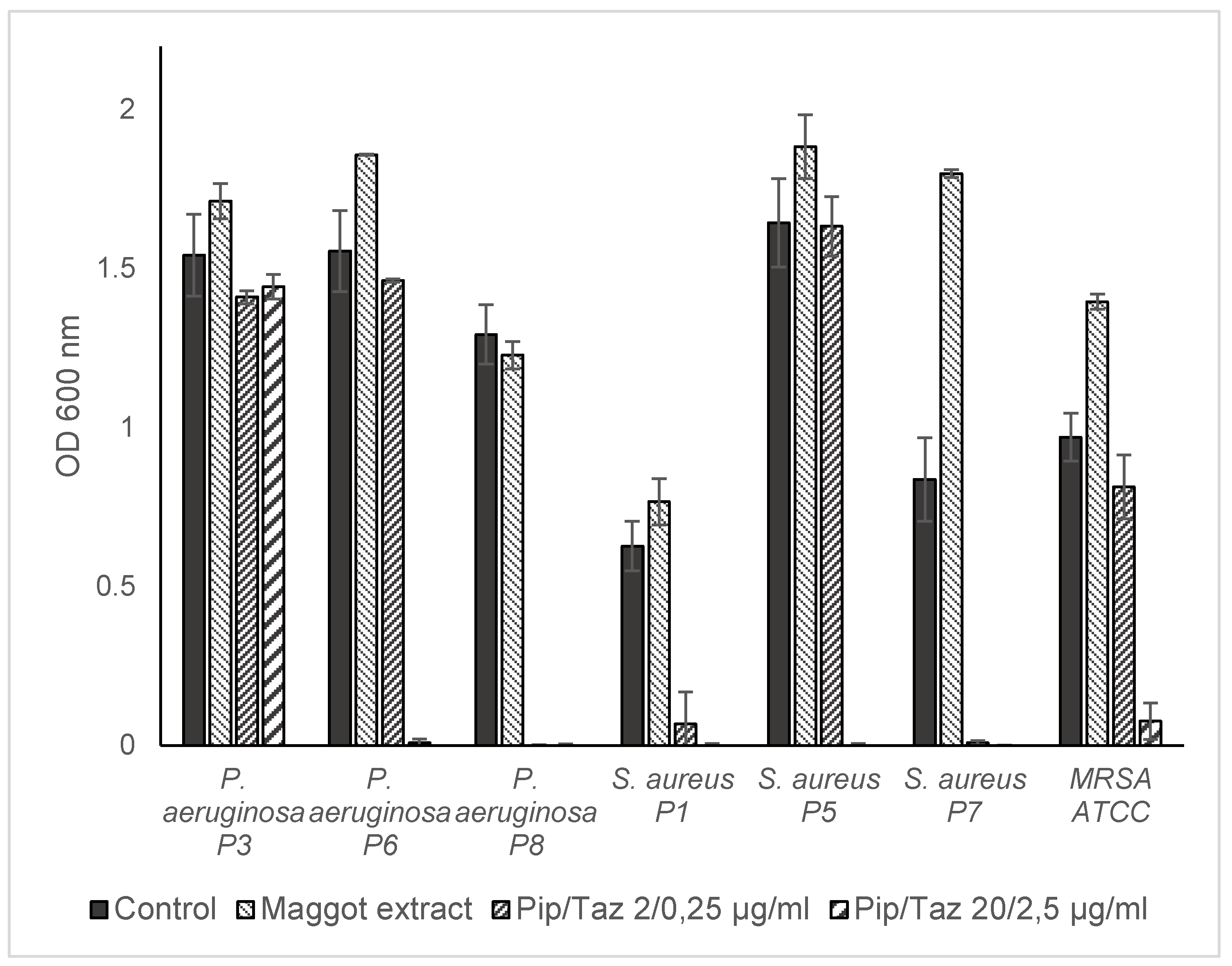

3.2. Effects of Maggot Extracts on Bacterial Growth In Vitro

Studies on growth inhibition in the form of a zone of inhibition assay showed no inhibition with different extract batches and the native ES, neither in the isolated strains nor in the reference strains. In microbroth dilution assays with patient isolates and ATCC strains for the first group of bacteria (

P. mirabilis isolates and an ATCC strain,

P. rettgeri,

E. faecalis,

A. xylosoxidans,

S. pyogenes ATCC and a clinical isolate of

K. oxytoca) no significant growth inhibition was found even in the highest possible/solvable extract concentration. The same applies to the other isolates and strains tested (

P. aeruginosa from wounds of patients 3, 6, and 8;

S. aureus from wounds of patients 1, 5, and 7; and one MRSA ATCC strain). In some isolates, even a slight but not significant increase in growth compared to the control experiments could be observed (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). Total growth inhibition only occurred according to specific antibiograms at high concentrations of piperacillin/tazobactam. All three patient isolates of

S. aureus were sensitive to 20/2.5 μg/ml and in part also to 2/0.25 μg/ml piperacillin/tazobactam, whereas the MRSA strain expectedly did not respond to these concentrations with complete growth inhibition.

3.3. Effects of Maggot Extracts on Bacterial Biofilm Formation In Vitro

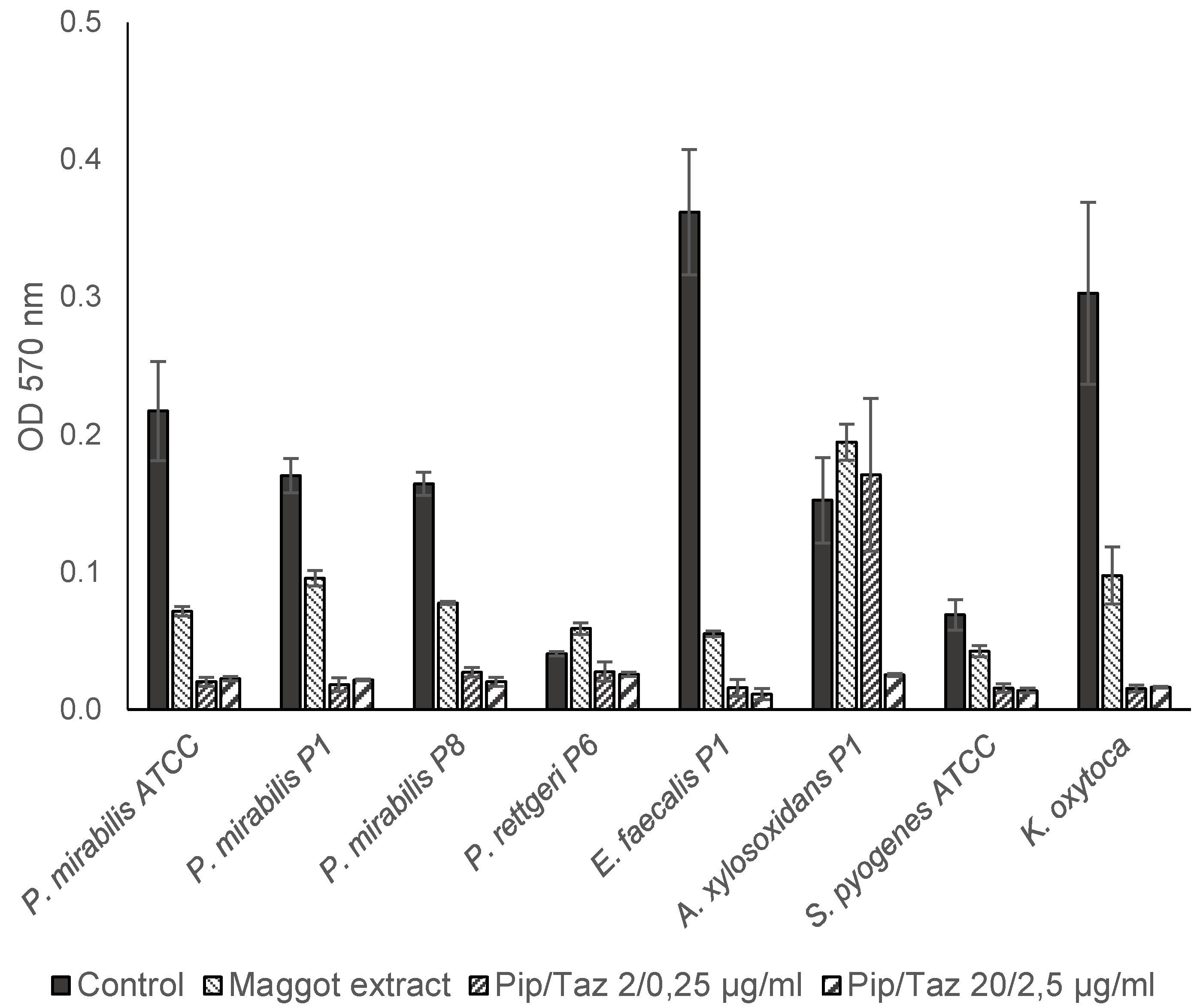

The investigation into the potential influence of a maggot extract on the formation of bacterial biofilms demonstrated, in the first set of bacteria (

P. mirabilis isolates and ATCC strain,

P. rettgeri,

E. faecalis,

A. xylosoxidans,

S. pyogenes ATCC and a clinical

K. oxytoca isolate), that for all

P. mirabilis isolates/strain,

E. faecalis,

S. pyogenes and

K. oxytoca, the formation of biofilms in the presence of the maggot extract was inhibited. In contrast, bacterial growth and biofilm formation were completely inhibited by piperacillin/tazobactam concentrations of 2/0.25 μg/ml. For

A. xylosoxidans, biofilm formation could only be prevented by a piperacillin/tazobactam concentration of 20/2.5 μg/ml. The lower piperacillin/tazobactam concentration (2/0.25 μg/ml) or the maggot extract resulted in approximately equally strong biofilm formation compared to the control (

Figure 5).

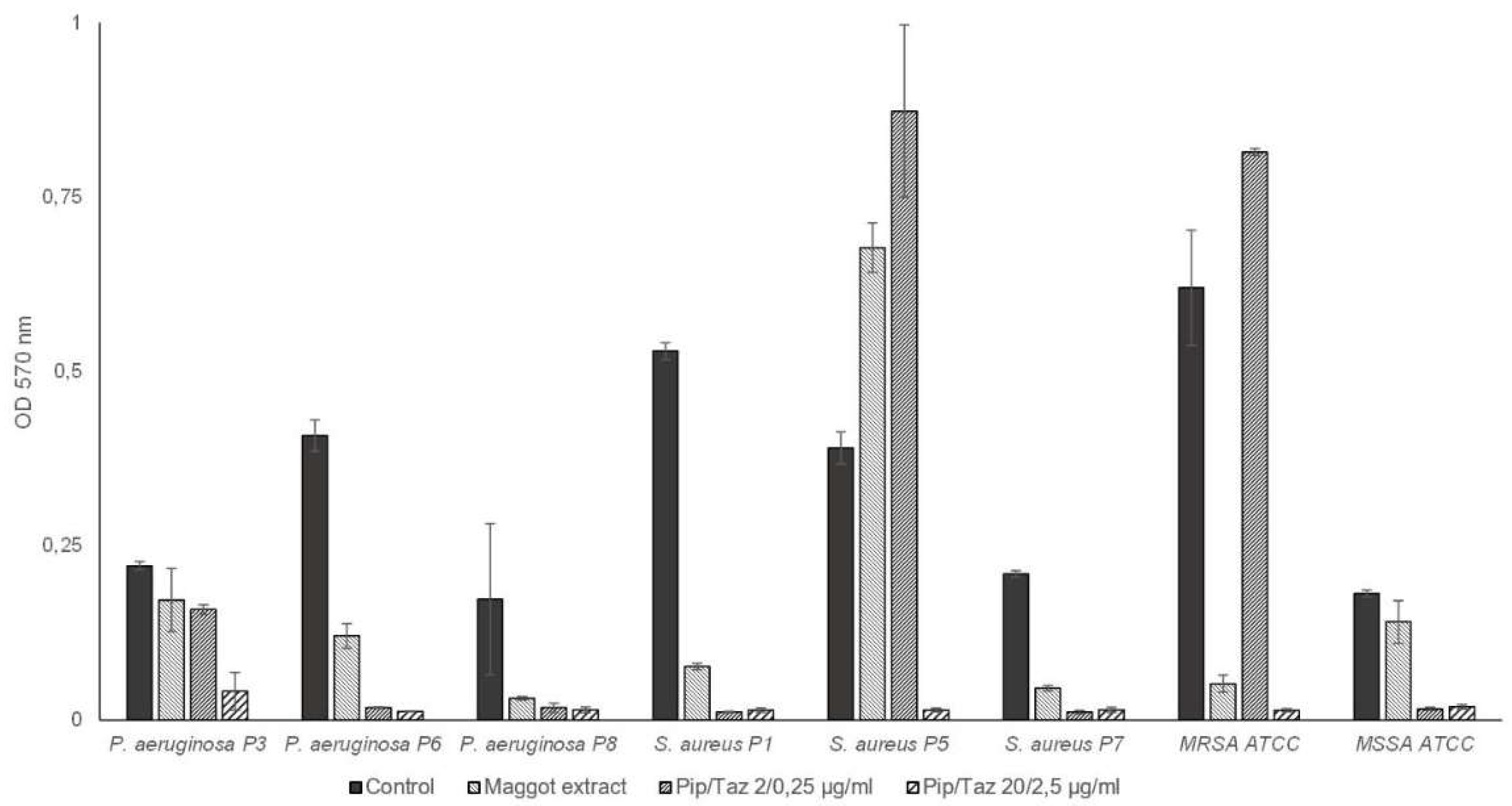

In the second set of bacteria tested (

P. aeruginosa from wounds of patients 3, 6, and 8,

S. aureus from wounds of patients 1, 5, and 7, as well as MRSA and MSSA ATCC strains), maggot extract resulted in a slight increase in biofilm formation in one

S. aureus isolate (

Figure 6). Minimal or no inhibitory effect on biofilm formation was observed for the

P. aeruginosa isolate of patient 3 and the MSSA strain, with a comparable effect of piperacillin/tazobactam 2/0.25 μg/ml for

P. aeruginosa from patient 3. However, higher concentrations of 20/2.5 μg/ml piperacillin/tazobactam resulted in complete prevention of biofilm formation in both strains. The extract demonstrated a significant inhibitory effect on biofilm formation by the

P. aeruginosa isolates from patient 6 as well as the

S. aureus isolate of patient 1, and an almost complete inhibitory effect on biofilm formation by the

P. aeruginosa isolate of patient 8 and the

S. aureus isolate of patient 7, comparable to that of piperacillin/tazobactam at a concentration of 2/0.25 μg/ml. For the strong biofilm-forming MRSA strain, biofilm formation was almost completely prevented with maggot extract, comparable to high-dose piperacillin/tazobactam. Lower doses of piperacillin/tazobactam resulted in enhanced biofilm formation.

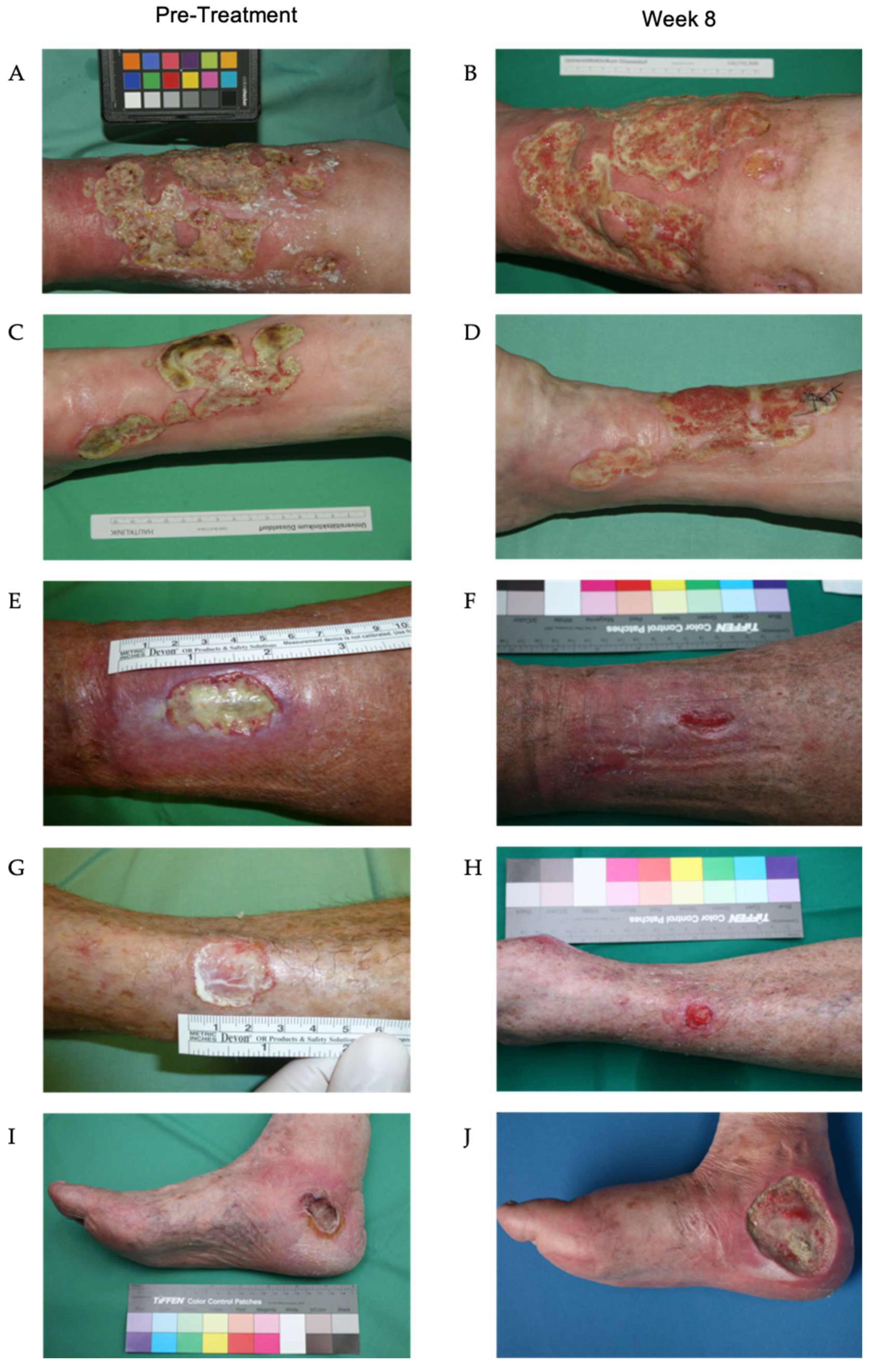

3.4. Clinical Course of Lower Leg Ulcerations During Treatment with Maggot Extract

In two patients, the treatment regimens were discontinued after two weeks due to inadequate therapeutic response or due to the increasing colonization with

P. aeruginosa, necessitating antibiotic therapy. Another patient (patient 9) was transitioned to an alternative therapeutic approach after approximately seven weeks due to critical colonization with

P. aeruginosa. In the remaining seven patients, a significant reduction in fibrin deposits and an increase in granulation tissue were observed after only two weeks. Nearly complete wound closure was achieved in patients 7 and 8 by the conclusion of the treatment period after 8 weeks. The ulcerations of patients 1, 2, 5, 6 and 10 exhibited signs of secondary wound healing, including epithelial islets, re-epithelialization of wound edges, fibrin depletion, and consecutive increases in granulation tissue, which were not attained via treatment prior to this investigation (

Figure 7).

4. Discussion

In a systematic comparison of conventional treatment methods for chronic ulcerations, it has been found that maggot therapy significantly accelerates the healing of wounds, particularly diabetic foot syndrome, but also of other ulcers, and increases the likelihood of healing [

14]. Given this context, the objective of this study was to investigate the possibility of making the beneficial effects of this biosurgical debridement accessible to a patient population by circumventing the adverse effects of the extracts. The extracts from the larvae of

Lucilia sericata significantly differed from the method of biosurgical debridement with living larvae of this species. Locally administered maggots continuously release their excretions/secretions into the wound and thus to the bacteria present there. It has been established that the larvae of

Lucilia sericata possess various proteases and antibacterial peptides (AMP), such as seraticin, and evidence from in vitro experiments indicates that living maggots are capable of affecting their bacterial environment by expressing certain antibacterial peptides, such as putative Lucilia defensin, diptericin, and various proline-rich antibacterial peptides [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

The absence of bactericidal effect in this maggot extract compared to living fly maggots is likely attributable to the production-related denaturation/absence of these peptides and proteases. Examination of the smears of the wounds treated with maggot extract revealed a uniform distribution of bacterial colonization between the wound edge and center. The number of patients treated in this study (n = 10) was relatively small but demonstrated similarities regarding isolated species with a retrospective ten-year study conducted in Germany. The study by Jockenhofer et al., which examined wounds from 100 patients, identified

S. aureus (53%) and

P. aeruginosa (25%) as the most common wound-colonizing species [

20]. In the present study,

S. aureus was found in six of ten patients and

P. aeruginosa in eight of ten patients. Notably,

P. aeruginosa isolates exhibited remarkable intrinsic antibiotic resistance in this study, with one isolate being multi-drug resistant to three out of four antibiotic classes (3MRGN), which can render colonization particularly critical.

During the course of the study, it was observed that patients with a short ulcer persistence (approximately 3 months) exhibited no colonization with

P. aeruginosa. The ulcer with the shortest duration colonized by

P. aeruginosa had existed for six months (patient 3). Given the relatively short six-month duration of the ulcer, along with the increasing green plaque formation and the detection of

P. aeruginosa, this colonization can be postulated as the cause of the ulcer’s persistent nature. A longitudinal study comparable to this investigation has demonstrated that the duration of the ulcer increases the likelihood of colonization by

P. aeruginosa, and this colonization can result in ulcer enlargement and further delayed wound healing [

21]. This phenomenon was also clinically evident in the three patients who had to prematurely discontinue the study due to increased local colonization by

P. aeruginosa. Nevertheless, with consistent application of the maggot extract in a total of seven patients, a clear clinical improvement was observed; therefore, it can be inferred that the positive effects on wound healing are not primarily mediated by a direct antimicrobial effect of the extract. Our analyses also revealed that the extract exhibited a remarkable inhibitory effect on the formation of bacterial biofilms. These biofilms play an essential role in the impaired healing of chronic wounds as they lead to prolonged inflammation and concomitant delayed wound healing by inhibiting local immune reactions [

22]. This result is supported by the results of Becerikli et al. who, in experiments with the same larval extract, found that the stability of biofilms of

P. aeruginosa and

S. aureus is significantly impaired, especially in the presence of antibiotics [

23].

It is important to note that improvement in wound healing is not necessarily measured solely by a reduction in the ulcer area. Additional factors, such as the formation of granulation tissue at the wound base and consequent reduction in wound depth, as well as the status of the proteinases and growth factors present in the wound exudates, reflect alterations in wound status. For instance, a decrease in biofilm could lead to a positive change in the wound environment with regard to improved wound healing [

24,

25]. Specifically, the colonization of biofilm-forming species, some of which exhibit pronounced resistance to antibiotics, are also likely to negatively influence wound healing through various virulence factors. These biofilms, consisting primarily of extracellular polymeric substances, provide bacteria with protection from external influences, such as antibiotics [

26]. The dissolution of such biofilms or the prevention of their formation is demonstrated for almost all isolated species in this study (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6); therefore, it appears to be of essential importance for the healing of chronic wounds. Consequently, it is highly probable that the improved clinical situation of the chronic wound of the patients in this study was attributable to the reduction of biofilm formation, leading to enhanced accessibility of the host immune system and reduced proliferation of colonizing bacteria.

5. Conclusions

In summary, this study demonstrates for the first time that Lucilia sericata extract has a sustained positive effect on wound cleansing and conditioning. This extract can be administered on an outpatient and inpatient basis, at any dressing change, without any time limitation, and can also be readily utilized after brief instruction by non-medical or nursing staff. Based on the observations of our applications, it is anticipated that this extract will expand treatment options for chronic wounds, serving as an alternative to traditional biosurgery. However, given the limited number of cases in this initial study, a larger randomized controlled trial is warranted.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Norman-Philipp Hoff and Falk Gestmann; methodology, Norman-Philipp Hoff and Falk Gestmann; software, Norman-Philipp Hoff, Falk Gestmann, Bernhard Homey, Theresa Jansen; validation, Bernhard Homey, Heinz Mehlhorn and Peter Arne Gerber; formal analysis, Norman-Philipp Hoff and Falk Gestmann; investigation, Norman-Philipp Hoff, Falk Gestmann and Theresa Jansen; writing—original draft preparation, Norman-Philipp Hoff, Falk Gestmann, Theresa Jansen, Sarah Janßen; writing—review and editing, Norman-Philipp Hoff, Falk Gestmann, Heinz Mehlhorn, Bernhard Homey and Peter Arne Gerber; visualization, Norman-Philipp Hoff and Falk Gestmann; supervision, Bernhard Homey, Heinz Mehlhorn and Peter Arne Gerber. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf, Medical Faculty for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Korber, A.; Klode, J.; Al-Benna, S.; Wax, C.; Schadendorf, D.; Steinstraesser, L.; Dissemond, J. Etiology of chronic leg ulcers in 31,619 patients in Germany analyzed by an expert survey. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2011, 9, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannier-Fischer, F.; Rabe, E. [Epidemiology of chronic venous diseases]]. Hautarzt 2003, 54, 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller-Bühl, U.; Leutgeb, R.; Bungartz, J.; Szecsenyi, J.; Laux, G. Expenditure of chronic venous leg ulcer management in German primary care: results from a population-based study. Int Wound J 2013, 10, 52–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nord, D. [Cost-effectiveness in wound care]. Zentralbl Chir 2006, 131, S185–S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinlin, J.; Schreml, S.; Babilas, P.; Landthaler, M.; Karrer, S. [Cutaneous wound healing. Therapeutic interventions]. Hautarzt 2010, 61, 611–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarus, G.; Valle, M.F.; Malas, M.; Qazi, U.; Maruthur, N.M.; Doggett, D.; Fawole, O.A.; Bass, E.B.; Zenilman, J. Chronic venous leg ulcer treatment: future research needs. Wound Repair Regen 2014, 22, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nenoff, P.; Herrmann, A.; Gerlach, C.; Herrmann, J.; Simon, J.C. [Biosurgical débridement using Lucilia sericata-maggots - an update]. Wien Med Wochenschr 2010, 160, 578–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumford, Z.; Nigam, Y. Maggots in Medicine: A Narrative Review Discussing the Barriers to Maggot Debridement Therapy and Its Utilisation in the Treatment of Chronic Wounds. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 6746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steenvoorde, P.; van Doorn, L.P. Maggot debridement therapy: serious bleeding can occur: report of a case. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2008, 35, 412–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.L.; Yang, Z.M.; Dong, H.C.; Zhang, H.; Zheng, X.; Yuan, B.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, P.N. Maggot extract accelerates skin wound healing of diabetic rats via enhancing STAT3 signaling. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0309903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, K.M.; Gennard, D.E.; Dixon, R.A. An assessment of the antibacterial activity in larval excretion/secretion of four species of insects recorded in association with corpses, using Lucilia sericata Meigen as the marker species. Bull Entomol Res 2010, 100, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Plas, M.J.; Jukema, G.N.; Wai, S.W.; Dogterom-Ballering, H.C.; Lagendijk, E.L.; van Gulpen, C.; van Dissel, J.T.; Bloemberg, G.V.; Nibbering, P.H. Maggot excretions/secretions are differentially effective against biofilms of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008, 61, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Toole, G.A.; Kolter, R. Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol Microbiol 1998, 28, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Jiang, K.; Chen, J.; Wu, L.; Lu, H.; Wang, A.; Wang, J. A systematic review of maggot debridement therapy for chronically infected wounds and ulcers. Int J Infect Dis 2014, 25, 32–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altincicek, B.; Vilcinskas, A. Septic injury-inducible genes in medicinal maggots of the green blow fly Lucilia sericata. Insect Mol Biol 2009, 18, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, A.S.; Sandvang, D.; Schnorr, K.M.; Kruse, T.; Neve, S.; Joergensen, B.; Karlsmark, T.; Krogfelt, K.A. A novel approach to the antimicrobial activity of maggot debridement therapy. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010, 65, 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceřovský, V.; Slaninová, J.; Fučík, V.; Monincová, L.; Bednárová, L.; Maloň, P.; Stokrová, J. Lucifensin, a novel insect defensin of medicinal maggots: synthesis and structural study. Chembiochem 2011, 12, 1352–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valachova, I.; Prochazka, E.; Bohova, J.; Novak, P.; Takac, P.; Majtan, J. Antibacterial properties of lucifensin in Lucilia sericata maggots after septic injury. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed 2014, 4, 358–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valachova, I.; Takac, P.; Majtan, J. Midgut lysozymes of Lucilia sericata - new antimicrobials involved in maggot debridement therapy. Insect Mol Biol 2014, 23, 779–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jockenhofer, F.; Gollnick, H.; Herberger, K.; Isbary, G.; Renner, R.; Stucker, M.; Valesky, E.; Wollina, U.; Weichenthal, M.; Karrer, S.; et al. Aetiology, comorbidities and cofactors of chronic leg ulcers: retrospective evaluation of 1 000 patients from 10 specialised dermatological wound care centers in Germany. Int Wound J 2016, 13, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjødsbøl, K.; Christensen, J.J.; Karlsmark, T.; Jørgensen, B.; Klein, B.M.; Krogfelt, K.A. Multiple bacterial species reside in chronic wounds: a longitudinal study. Int Wound J 2006, 3, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fazli, M.; Bjarnsholt, T.; Kirketerp-Moller, K.; Jorgensen, A.; Andersen, C.B.; Givskov, M.; Tolker-Nielsen, T. Quantitative analysis of the cellular inflammatory response against biofilm bacteria in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen 2011, 19, 387–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becerikli, M.; Wallner, C.; Dadras, M.; Wagner, J.M.; Dittfeld, S.; Jettkant, B.; Gestmann, F.; Mehlhorn, H.; Mehlhorn-Diehl, T.; Lehnhardt, M.; et al. Maggot Extract Interrupts Bacterial Biofilm Formation and Maturation in Combination with Antibiotics by Reducing the Expression of Virulence Genes. Life (Basel) 2022, 12, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeffery Marano, R.; Jane Wallace, H.; Wijeratne, D.; William Fear, M.; San Wong, H.; O’Handley, R. Secreted biofilm factors adversely affect cellular wound healing responses in vitro. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 13296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurlow, J.; Wolcott, R.D.; Bowler, P.G. Clinical management of chronic wound infections: The battle against biofilm. Wound Repair Regen 2025, 33, e13241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarty, S.M.; Cochrane, C.A.; Clegg, P.D.; Percival, S.L. The role of endogenous and exogenous enzymes in chronic wounds: a focus on the implications of aberrant levels of both host and bacterial proteases in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen 2012, 20, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

(A) Lyophilized extract of larvae of

Lucilia sericata in 3.5 ml Glass-Vials. (B) Procedure for the Larveel Study. Patients with chronic wounds persisting for ≥3 months undergo a three-week period of stage-appropriate wound management without surgical intervention. If no improvement in wound condition is observed during this time, the patient is included in the study. Microbiological swab samples are collected from both the wound edge and center at predetermined intervals. Wound exudate is obtained using a pipette, and photo documentation is performed alongside the application of Larveel. Created in BioRender. Homey, B. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/i00k077)

.

Figure 1.

(A) Lyophilized extract of larvae of

Lucilia sericata in 3.5 ml Glass-Vials. (B) Procedure for the Larveel Study. Patients with chronic wounds persisting for ≥3 months undergo a three-week period of stage-appropriate wound management without surgical intervention. If no improvement in wound condition is observed during this time, the patient is included in the study. Microbiological swab samples are collected from both the wound edge and center at predetermined intervals. Wound exudate is obtained using a pipette, and photo documentation is performed alongside the application of Larveel. Created in BioRender. Homey, B. (2025)

https://BioRender.com/i00k077)

.

Figure 2.

Frequencies of different bacterial species from patient wounds during the treatment with maggot extract. Swabs were taken from the wound edges and wound centers of the patient’s wounds prior to treatment and every other week of treatment. The characterization as an individual isolate was carried out via antibiograms.

Figure 2.

Frequencies of different bacterial species from patient wounds during the treatment with maggot extract. Swabs were taken from the wound edges and wound centers of the patient’s wounds prior to treatment and every other week of treatment. The characterization as an individual isolate was carried out via antibiograms.

Figure 3.

Microbroth dilution assay for P. mirabilis and other isolates. Isolates were cultivated in TSB (control), maggot extract dissolved in TSB or pip/taz diluted in TSB for 24 h at 37°C. Shown are mean values minus non-inoculated vehicle controls and the standard deviation from each n = 3 measurements. OD = optical density; P = Patient + number; Pip/Taz = Piperacillin/Tazobactam; TSB = tryptic soy broth.

Figure 3.

Microbroth dilution assay for P. mirabilis and other isolates. Isolates were cultivated in TSB (control), maggot extract dissolved in TSB or pip/taz diluted in TSB for 24 h at 37°C. Shown are mean values minus non-inoculated vehicle controls and the standard deviation from each n = 3 measurements. OD = optical density; P = Patient + number; Pip/Taz = Piperacillin/Tazobactam; TSB = tryptic soy broth.

Figure 4.

Microbroth dilution assay for P. aeruginosa and S. aureus isolates. Isolates and ATCC strains were cultivated in TSB (control), maggot extract dissolved in TSB or pip/taz diluted in TSB for 24 h at 37°C. Shown are mean values minus non-inoculated vehicle controls and the standard deviation from each n = 3 measurements. OD = optical density; P = Patient + number; Pip/Taz = Piperacillin/Tazobactam; TSB = tryptic soy broth.

Figure 4.

Microbroth dilution assay for P. aeruginosa and S. aureus isolates. Isolates and ATCC strains were cultivated in TSB (control), maggot extract dissolved in TSB or pip/taz diluted in TSB for 24 h at 37°C. Shown are mean values minus non-inoculated vehicle controls and the standard deviation from each n = 3 measurements. OD = optical density; P = Patient + number; Pip/Taz = Piperacillin/Tazobactam; TSB = tryptic soy broth.

Figure 5.

Biofilm formation by P. mirabilis and other isolates. Isolates and ATCC strains were cultivated in TSB (control), maggot extract dissolved in biofilm-medium or pip/taz diluted in biofilm-medium for 24 h at 37°C. Biofilms were stained with crystal violet. Shown are mean values minus non-inoculated vehicle controls and the standard deviation from each n = 3 measurements. OD = optical density; P = Patient + number; Pip/Taz = Piperacillin/Tazobactam.

Figure 5.

Biofilm formation by P. mirabilis and other isolates. Isolates and ATCC strains were cultivated in TSB (control), maggot extract dissolved in biofilm-medium or pip/taz diluted in biofilm-medium for 24 h at 37°C. Biofilms were stained with crystal violet. Shown are mean values minus non-inoculated vehicle controls and the standard deviation from each n = 3 measurements. OD = optical density; P = Patient + number; Pip/Taz = Piperacillin/Tazobactam.

Figure 6.

Biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. Isolates and ATCC strains were cultivated in TSB (control), maggot extract dissolved in biofilm-medium or pip/taz diluted in biofilm-medium for 24 h at 37°C. Biofilms were stained with crystal violet. Shown are mean values minus non-inoculated vehicle controls and the standard deviation from each n = 3 measurements. OD = optical density; P = Patient + number; Pip/Taz = Piperacillin/Tazobactam.

Figure 6.

Biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. Isolates and ATCC strains were cultivated in TSB (control), maggot extract dissolved in biofilm-medium or pip/taz diluted in biofilm-medium for 24 h at 37°C. Biofilms were stained with crystal violet. Shown are mean values minus non-inoculated vehicle controls and the standard deviation from each n = 3 measurements. OD = optical density; P = Patient + number; Pip/Taz = Piperacillin/Tazobactam.

Figure 7.

Wounds of patients during treatment with maggot extract. The wounds of the patients were treated three times a week. Photographs before treatment (A, C, E, G, I) and after eight weeks (B, D, F, H) of treatment. Treatment with Larveel significantly reduced fibrin deposits and enhanced granulation tissue formation (B, D, F, H). In patients 7 and 8 (E, F, G, H), a marked reduction in wound size was observed after 8 weeks, with near-complete healing and epithelialization progressing from the wound margins (Figures F and H). In contrast, patient 9 (Figures I and J) experienced a critical colonization by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which was associated with an increase in wound size.

Figure 7.

Wounds of patients during treatment with maggot extract. The wounds of the patients were treated three times a week. Photographs before treatment (A, C, E, G, I) and after eight weeks (B, D, F, H) of treatment. Treatment with Larveel significantly reduced fibrin deposits and enhanced granulation tissue formation (B, D, F, H). In patients 7 and 8 (E, F, G, H), a marked reduction in wound size was observed after 8 weeks, with near-complete healing and epithelialization progressing from the wound margins (Figures F and H). In contrast, patient 9 (Figures I and J) experienced a critical colonization by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which was associated with an increase in wound size.

Table 2.

Frequency and localization of isolation of bacterial species during treatment with maggot extract.

Table 2.

Frequency and localization of isolation of bacterial species during treatment with maggot extract.

| |

week 0 |

n=10 |

week 2 |

n=9 |

week 4 |

n=8 |

week 6 |

n=8 |

week 8 |

n=5 |

| |

margin |

center |

margin |

center |

margin |

center |

margin |

center |

margin |

center |

| P. aeruginosa |

7 |

6 |

6 |

5 |

6 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

| S. aureus |

6 |

5 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

1 |

1 |

| P. mirabilis |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

| A. xylosoxidans |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| E. faecalis |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| P. rettgeri |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| C. koseri |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| K. pneumoniae |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

| Gr. G Streptococci |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

| Dermal flora |

4 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).