1. Introduction

Intussusception is the most common cause of bowel obstruction in children aged three months to six years. It is a life-threatening condition that occurs when part of the intestine folds like a telescope, with one part slipping into another. This can cause a blockage that prevents digested food from passing through the intestines. If left untreated, it can lead to severe damage to the intestines, intestinal infections, internal bleeding, and even peritonitis [

1,

2].

Although some cases of intussusception in older children are associated with pathological changes such as lymphoma or polyps, the cause of most cases in infants is unknown. However, many previous studies have observed that intussusception is related to lymphoid tissue hyperplasia, which may be caused by infections such as adenovirus [

3]. Our study, which analyzed intestinal tissue from patients who experienced intussusception, may provide more direct evidence of the relationship between adenovirus infection and intussusception.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Participants

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the pathological tissues of children under 6 years old with intussusception who were admitted to Taipei Cathay Hospital from December 1998 to September 2020 due to failed manual reduction. A total of 35 pathological specimens were recorded in the surgical reports. There were 27 appendix tissues and 8 intestinal tissues in the pathological specimens. Due to the long storage time of most specimens, only 8 appendix specimens were successfully processed into formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue. Adenovirus immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection were performed on these specimens. The control group consisted of 8 children under 6 years of age who underwent incidental appendectomies without intussusception or appendicitis. This study analyzed the positive rate of adenovirus in intussusception from pathological tissues using IHC and PCR. The pathological tissues were processed into FFPE: 4 μm sections for IHC and 10 μm sections for PCR.

2.2. Immunohistochemical Analysis

Serial 4 μm paraffin sections were deparaffinized using EZ Prep (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc., Tucson, AZ, USA). Slides were incubated with anti-adenovirus (Bio SB, Santa Barbara, CA, USA) at a 1:50 titration for 32 min using the automated Ventana Benchmark XT (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.). Markers were detected using the Optiview DAB detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.) according to the manufacturer’s protocol [

4]. All sections were counterstained with hematoxylin using Ventana reagent. Immunohistochemically stained slides were reviewed and analyzed by a pathologist for correlation with histological interpretation.

Deparaffinized FFPE sections (4 µm) were incubated with the diluted anti-adenovirus antibody (1:50) (Bio SB). Labeling was detected using the OptiView DAB detection kit (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.) according to our previous report [

4,

5]. All sections were counterstained with hematoxylin using Ventana reagent. Immunohistochemically stained slides were reviewed and analyzed by a pathologist to determine the correlation with histological interpretation.

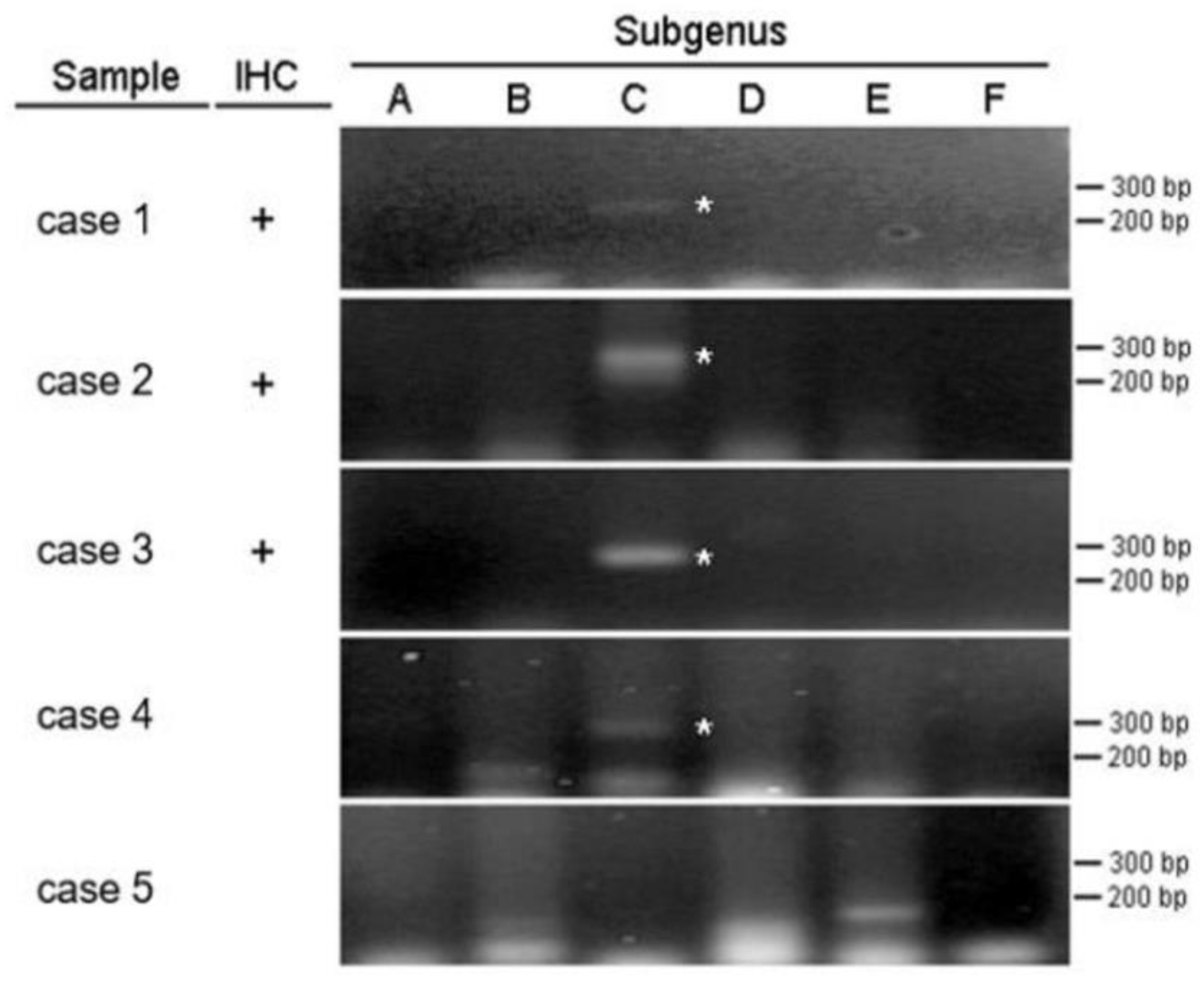

2.3. Nested PCR for Adenovirus Species C Hexon DNA

After sequence comparison, six subgenus-specific primer pairs HsgA1/HsgA2, HsgB1/HsgB2, HsgC1/HsgC2, HsgD1/HsgD2, HsgE1/HsgE2, and HsgF1/HsgF2 were evaluated, and nested PCR was performed. The subgenus-specific primer pairs used in this study were prepared from formalin-fixed paraffin-packed DNA using the GeneRead DNA FFPE kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, as reported by Pring-Akerblom et al [

6]. DNA was extracted from 4 µm thick sections of buried tissue samples.

To amplify viral DNA obtained from FFPE samples, we used a 10 µL reaction mixture containing 2 µL of viral DNA, 0.5 µM of each primer, 1 µL of AmpliTaq Gold® 360 Buffer, 2.0 µM of MgCl2, and each dNTP AmpliTaq Gold® 360 DNA Polymerase prepared at a concentration of 200 µM and 0.25 units. Thermal cycling was performed for a total of 50 cycles. One cycle consisted of denaturation at 95 °C for 60 s, annealing at 40 °C for 60 s, and primer extension at 72 °C for 60 s. In the first cycle, the denaturation step lasted for 600 s at 95 °C; in the last cycle, the extension step lasted for 420 s at 72 °C. Two microliters of the PCR product from the subgenus-specific primer pair was used as a template for the second step of a nested PCR run using the same subgenus-specific primer pair. This PCR amplification was performed following the same protocol as the first reaction. Ten microliters of the final reaction product was analyzed on an ethidium bromide-stained 2% agarose gel.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Adenovirus IHC testing using anti-adenoviral antibodies identified 3 positive cases (37.5%) and PCR testing identified adenovirus type C in 4 cases (50%), compared with 8 non-intussusception controls using chi-square test. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 22.0; IBM Corp.). P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

3. Results

Our study directly demonstrates the relationship between adenovirus infection and intussusception using retrospective pathological evidence in children. Histopathological examination showed inflammation extending into the serosa in some cases.

Adenovirus immunohistochemical staining was observed in the cytoplasm and nuclei of epithelial cells and monocytes in some patients (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

Among the 8 specimens, 3 were positive for adenovirus by IHC (37.5%), and 4 were positive by PCR (50%). None of the control subjects was positive in IHC (

Figure 4) and PCR analyses. We combined IHC and PCR results and showed that the adenovirus detected in this study is serotype C (

Figure 5). Our pathological evidence directly confirms the relationship between adenovirus infection and intussusception. IHC and PCR analyses confirmed evidence of adenovirus infection in patients with intussusception. Compared with the control group, the P-value for IHC was greater than 0.05, showing no statistical difference, while the P-value for PCR was less than 0.05, showing a statistical difference (

Table 1 and

Table 2). For diagnosing adenovirus in intussusception, PCR is as useful and reliable as IHC and is more sensitive.

4. Discussion

Human adenoviruses are the most common pathogens isolated from cases of pediatric intussusception. However, the specific clinical characteristics of pediatric intussusception associated with adenovirus infection are unclear.

Adenoviruses are important human pathogens associated with a wide range of clinical disorders. Fifty-one recognized human adenovirus serotypes are classified into 6 types (A–F) based on common organisms, morphological and genetic characteristics, and serotype composition. A given species also tends to be associated with a specific disease syndrome. For example, serotypes 40 and 41 of type F are most commonly associated with acute gastroenteritis in children and adults. By contrast, serotype species C (1, 2, 5, and 6) are most commonly associated with respiratory diseases and conjunctivitis in young children. Research conducted in the United States shows that adenovirus C causes less than 15% of intussusception cases [

2,

7].

Adenoviruses are an important cause of respiratory infections in infants and young children and are associated with a large proportion of intussusception cases.

Intussusception is a common cause of bowel obstruction in children younger than 3 years old. Although the incidence of intussusception varies among countries and years, a retrospective study based on data from 1995 to 1964 and 1999 to 2001 found that the incidence of intussusception in Taiwan is approximately 0.35–0.77 per 1,000 live births, and the highest incidence is between 12 and 24 months of age [

8,

9]. Most cases of intussusception in children remain idiopathic, and many previous studies have discussed possible causes of intussusception in children. Once a child is infected with adenovirus, swollen lymph nodes and abnormal gastrointestinal motility may develop, leading to intussusception. The most common sites are usually in the small intestine and terminal ileum [

10].

Since the 1960s, there has been an increasing number of studies on adenovirus infection and intussusception. In 1969, Clarke Jr EJ et al. described adenovirus infection in Taiwanese children with intussusception [

11].

They observed that intussusception in infancy is often associated with adenovirus infection, which tends to support the hypothesis that early intestinal spread of adenovirus in Taipei causes intussusception. In 1992, Bhisitkul DM et al. discovered adenovirus infection and intussusception in children [

12]. In 2003, Guana J et al. discovered intussusception associated with adenovirus infection in Mexican children. Using IHC analysis, they found that adenovirus antigen was present in epithelial cells in tissue specimens from 4 of 12 Mexican children (33%) who underwent surgical resection for intussusception. In addition, species C (non-enteric) adenovirus was the most dominant type [

13]. In 2010, Chen SC et al. studied the epidemiology of childhood intussusception and determinants of recurrence and operation: analysis of national health insurance data between 1998 and 2007 in Taiwan [

14]. They observed that the family Adenoviridae has been considered the predominant viral pathogen involved in intussusception in recent decades. In 2011, Okimoto S et al. reported an association of viral isolates from stool samples with intussusception in children [

15]. In 2016, Ukrapol N et al. noted adenovirus infection as a potential risk for intussusception in pediatric patients. They pointed out that molecular analysis of adenovirus genomes showed that the adenoviruses detected in patients with intussusception were all type C adenoviruses [

16]. In 2017, Jang J et al. discovered an epidemiological correlation between fecal adenovirus subgroups and pediatric intussusception in South Korea [

17]. In 2023, Tseng WY et al. noted that adenovirus infection is a risk factor for recurrent intussusception in pediatric patients [

18]. Most of the abovementioned studies have demonstrated an association between adenovirus infection and intussusception in children. However, much of the evidence is indirect, such as throat swab data or stool samples. Our study analyzed intestinal tissue, which may provide more direct evidence of the relationship between adenovirus infection and intussusception. A team at our hospital demonstrated this relationship by analyzing the annual incidence of these two diseases from January 2008 to June 2011, showing similarities in the peak months of both diseases [

19]. Another study demonstrated the co-occurrence of intussusception and adenovirus infection in identical twins [

20].

Histopathological characteristics observed in routine H&E staining studies cannot be used to differentiate adenoviral infection from other causes of appendicitis, but H&E staining is often used to predict treatment response, diagnose cancer, and determine the likely outcome of the disease [

21]. Our study revealed approximately the same proportion of stained cells. Identification of adenoviral inclusions by H&E staining is not very accurate because autolyzed and/or necrotic cells and poorly fixed tissue samples may produce artifacts from similarly stained cells. We found that IHC analysis more easily visualized virus-infected cells than H&E staining. We noted that, in addition to mononuclear inflammatory cells and dendritic cells in follicles beneath the lamina propria, adenoviral antigens were also found in epithelial cells (

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). In addition to being used to detect pathogen antigens in fixed tissue, IHC using monoclonal and multiclonal antibodies can complement fresh tissue PCR and culture for the direct diagnosis of infectious diseases [

22].When diagnosing adenovirus infection, various types of samples can be used, including nasopharyngeal aspirates and swabs. These samples can then be analyzed using a variety of methods, with PCR being considered the “gold standard.” Many commercial PCR kits have been developed by laboratories around the world. These kits can be used to detect adenovirus in a variety of samples [

23]. Different multiplex PCR combinations can target most, if not all, known infectious pathogens affecting the human respiratory system. PCR is also widely used to detect adenovirus infection. Molecular testing detects a wide range of enteric pathogens and has low discriminatory accuracy in distinguishing symptomatic from asymptomatic individuals. Even so, multiplex PCR allows for direct comparisons between different countries and reveals considerable environmental specificity [

24].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report in Taiwan to observe adenovirus infection and intussusception from a pathological perspective. Our study included 29 patients who underwent intussusception surgery, and 35 pathological specimens were recorded in the surgical reports There were 27 appendix tissues and 8 intestinal tissues in the pathological specimens. Nevertheless, since most of the specimens had been preserved for many years, only 8 appendix specimens from incidental appendectomies were successfully processed into FFPE tissue. IHC testing using anti-adenoviral antibodies identified 3 positive cases (37.5%). PCR testing revealed adenovirus type C in 4 cases (50%). The control group consisted of 8 children under 6 years of age who underwent incidental appendectomies without intussusception or appendicitis. None of the control subjects were positive in IHC with anti-adenovirus antibody and qPCR analyses. Compared with the control group, the P-value for IHC was greater than 0.05, showing no statistical difference, while the P-value for PCR was less than 0.05, showing a statistical difference.

5. Conclusions

Although most cases of intussusception are idiopathic, there are some potential causes, such as guidance points near the ileocecal junction, bacterial or viral infection, and familial predisposition. Our study directly confirmed the relationship between adenovirus infection and intussusception through pathological evidence. IHC analysis and PCR testing confirmed evidence of adenoviral infection in patients with intussusception. PCR is as useful and reliable as IHC in diagnosing adenovirus in intussusception and has greater sensitivity than IHC.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.H. L., C.J.H. and C.Y.L.; methodology, L.H. L. and Y.H.L..; software, L.H. L.; validation, L.H. L.; formal analysis, L.H. L.; investigation, L.H. L. and Y.C.C.; resources, L.H. L. and Y.C.C.; data curation, L.H. L. and Y.C.C.; writing—original draft preparation, L.H. L.; writing—review and editing, L.H. L.; visualization, L.H. L.; supervision, L.H. L. and C.J.H.; project administration L.H. L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grant funding from Cathay General Hospital, Taiwan, grant no. CGH-MR-B10910.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Cathay General Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan, approval number CGH-P111059, approved on 27 January 2021.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived given the impossibility of retrospectively retrieving the consent for all the infants included in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Chan-Wei Chen and Miss Li-Ju Chuang for their unremitting efforts.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

FFPE = formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; IHC = immunohistochemistry; PCR = polymerase chain reaction.

References

- Jain, S.; Haydel, M.J. Child Intussusception. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024, Jan–. pmid: 28613732.

- Shieh, W.J. Human adenovirus infections in pediatric population - an update on clinico-pathologic correlation. Biomed J. 2022, 45, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Rippe, J.; Davis, J.C.; Dennis, R.A.; et al. Impact of a 6-12-h delay between ileocolic intussusception diagnostic US and fluoroscopic reduction on patients’ outcomes. Pediatr Radiol. 2024, 54, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niittykoski, M.; von Und Zu Fraunberg, M.; Martikainen, M.; et al. Immunohistochemical characterization and sensitivity to human adenovirus serotypes 3, 5, and 11p of new cell lines derived from human diffuse grade II to IV gliomas. Transl Oncol. 2017, 10, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.H.; Huang, C.J.; Lo, C.Y.; et al. Proof of the association between adenovirus infection and appendicitis in children through pathological evidence. J Clin Pathol. 2024, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Pring-Akerblom, P.; Trijssenaar, F.E.; Adrian, T.; et al. Multiplex polymerase chain reaction for subgenus-specific detection of human adenoviruses in clinical samples. J Med Virol. 1999, 58, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Lee, C.; Lee, J.Y. Genomic evolution and recombination dynamics of human adenovirus D species: insights from comprehensive bioinformatic analysis. J Microbiol. 2024, 62, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.H. Perspectives on intussusception. Pediatr Neonatol. 2013, 54, 143–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, W.L.; Yang, T.W.; Chi, W.C.; et al. Intussusception in Taiwanese children: analysis of incidence, length of hospitalization and hospital costs in different age groups. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005, 104, 398–401. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, M.; Afowork, J.; Pitt, J.B.; et al. Scoring system to evaluate risk of nonoperative management failure in children with intussusception. J Surg Res. 2024, 300, 503–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke Jr, E.J.; Phillips, I.A.; Alexander, E.R. Adenovirus infection in intussusception in children in Taiwan. JAMA. 1969, 208, 1671–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhisitkul, D.M.; Todd, K.M.; Listernick, R. Adenovirus infection and childhood intussusception. Am J Dis Child. 1992, 146, 1331–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guarner, J.; de Leon-Bojorge, B.; Lopez-Corella, E.; et al. Intestinal intussusception associated with adenovirus infection in Mexican children. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003, 120, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.C.; Wang, J.D.; Hsu, H.Y.; et al. Epidemiology of childhood intussusception and determinants of recurrence and operation: analysis of national health insurance data between 1998 and 2007 in Taiwan. Pediatr Neonatol. 2010, 51, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okimoto, S.; Hyodo, S.; Yamamoto, M.; et al. Association of viral isolates from stool samples with intussusception in children. Int J Infect Dis. 2011, 15, e641–e645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukarapol, N.; Khamrin, P.; Khorana, J.; et al. Adenovirus infection: a potential risk for developing intussusception in pediatric patients. J Med Virol. 2016, 88, 1930–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, J.; Lee, Y.J.; Kim, J.S.; et al. Epidemiological correlation between fecal adenovirus subgroups and pediatric intussusception in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2017, 32, 1647–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, W.Y.; Chao, H.C.; Chen, C.C.; et al. Adenovirus infection is a risk factor for recurrent intussusception in pediatric patients. Pediatr Neonatol. 2023, 64, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.Y.; Lin, L.H. The association of intussusception and adenovirus infection in children: a single center study in Taiwan. FJJM. 2013, 11, 297–303. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.H.; Lin, L.H.; Hung, S.P. Simultaneous intussusception associated with adenovirus infection in monozygotic twins: a case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019, 98, e18294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Tao, L.; Qiu, J.; et al. Tumor biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024, 9, 132. [Google Scholar]

- Oumarou Hama, H.; Aboudharam, G.; Barbieri, R.; et al. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of human infectious diseases: a review. Diagn Pathol. 2022, 17, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koryukov, M.A.; Oscorbin, I.P.; Novikova, L.M.; et al. A novel multiplex LAMP assay for the detection of respiratory human adenoviruses. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 7215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jasuja, J.K.; Bub, F.; Veit, J.; et al. Multiplex PCR for bacterial, viral and protozoal pathogens in persistent diarrhoea or persistent abdominal pain in Côte d'Ivoire, Mali and Nepal. Sci Rep. 2024, 14, 10926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).