1. Introduction

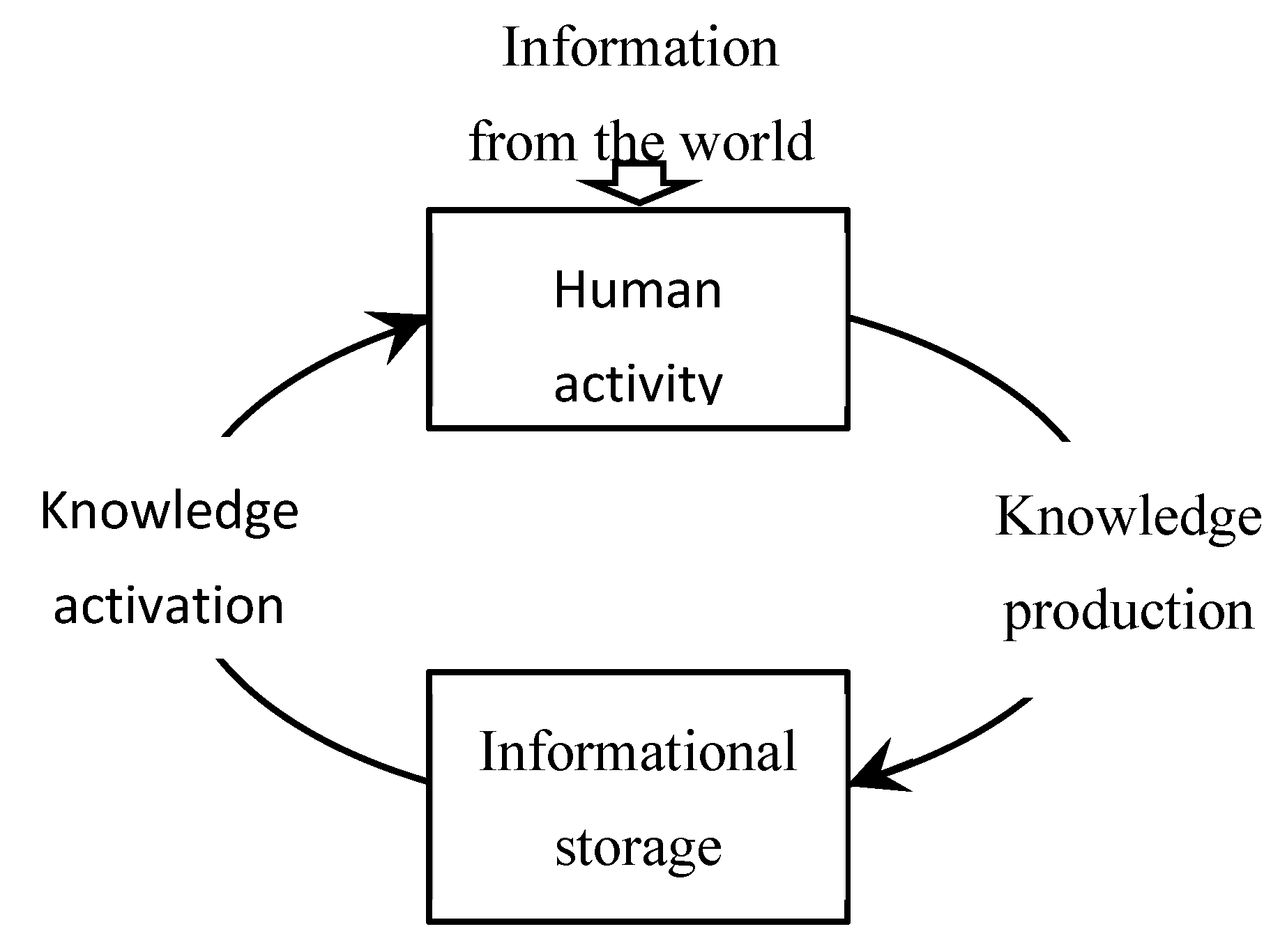

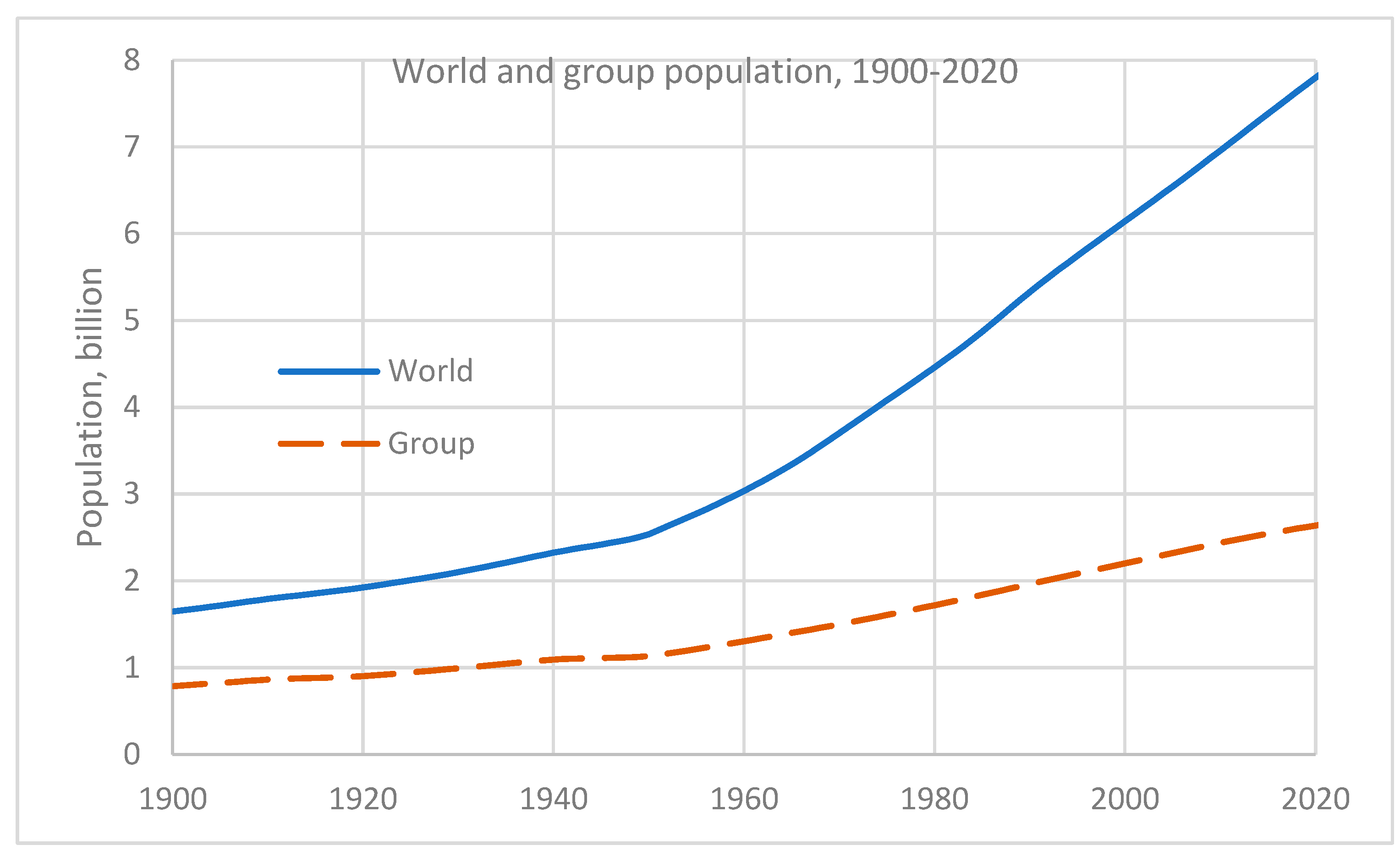

The development of society is directly related to the accumulation of knowledge both in the field of science and technology, and in the cultural and humanitarian sphere. Knowledge is produced at a rate that depends on its amount and population. In turn, knowledge production controls population growth. The corresponding dynamic equations were obtained by

Dolgonosov and Naidenov (2006). In this approach, a crucial factor is per capita productivity of knowledge

, which depends on knowledge amount

and time

. Knowledge production

can be represented in general form as

where

is the population size,

is an external source of knowledge. We assume in

(1) that the number of knowledge producers is proportional to the total

population, as is usually the case in econometric models

(Romer, 1986, 1990; Kremer, 1993; Abdih and Joutz, 2006;

Dong et al., 2016, Kato, 2016). In our previous studies

(Dolgonosov, 2016,

2020) we looked at the problem of

knowledge production by assuming that productivity is constant. This assumption

has reasonable grounds for a pre-information society with its undeveloped

computing capabilities. However, at present, when we have an information

society, the rapid progress of computer technology and artificial intelligence

leads to increased productivity, which should be reflected in the rate of

knowledge accumulation and, as a consequence, in demographic dynamics. The

problem is to figure out what the function

is, how justified the constant productivity

approximation is, and under what conditions it can be applied. We consider the

problem in this work.

Further development of the theory requires

consideration of the general case where productivity depends on accumulated

knowledge. This problem has also been addressed in econometric models

describing the relationship between technological development and population

growth. Unlike technologies, knowledge is understood somewhat more broadly: it

includes all the components of human culture, which undoubtedly influence

population growth to a certain extent. Nevertheless, econometric models capture

the essential features of the phenomenon. First of all, it is worth mentioning

Romer's (1986, 1990) model, which was written for

technology, but we will extend it to knowledge in general. Romer's model can be

presented as

with the only difference that Romer's variable

is the sum of technologies (although this is not

all knowledge),

is the number of only those people who work in

science and technology, and per capita productivity is expressed as

where

,

and

are parameters (everything is in our notation).

Ultimately, Romer accepts

and

equal to 1.

Kato (2016) analyzes

a model similar to (2)-(3), with the only difference that the total population is used instead of . The author expresses the following thought about

the exponent (in the original it is designated as ):

“When , then the growth rate of technological progress

would rise rapidly with increasing level of technology. However, such

situations have not been observed in developed nations through postwar periods,

so Barro and Sala-i-Martin (1992) imposed

the condition .”

We use this remark when constructing the

productivity function.

Kremer's (1993) model

can also be represented as equation (1). Unlike Romer's model (2), Kremer uses

the total population

instead of the number of S&T personnel

, but the parameters

and

are still equal to 1. So, instead of (3) we have

A similar model of technology development was used

by

Collins et al (2013) in their

evolutionary theory of long-run economic growth.

Jones (1995, 1999) modified

Romer's model by setting

in (3), which after a series of transformations

led him to the equation

where

. The meaning of this equation can be clarified

after integrating it, which yields

is a constant. From (6) it follows that the

technologies accumulated to date are only the output of currently working

technology producers. However, this approach does not reflect the influence of

previous generations, whose work also contributed to the development of technology.

Obviously, the equation for

must contain an integral term summing up the

contribution of past generations.

The same problem was noted by Dong et al. (2016), who, based on an analysis of

well-known econometric models and extensive empirical material, showed that

technological growth depends not only on the current generation of people, but

also on the achievements of past generations. The authors found deviations from

the proportionality law between the number of technology producers and the

total population when dealing with the long-term evolution of society over

millennia.

Okuducu

and Aral (2017) suggested that productivity could be a constant, linear,

quadratic, or exponential function of knowledge amount, and used these

representations to compute various hypothetical scenarios of knowledge

dynamics.

There is a difference between the knowledge

approach (1) and the econometric one (2)-(4). Productivity is the per capita knowledge product (different

forms of publication, e.g. patents, articles, books; cf. Abramo et al., 2019) in the first case or the per

capita gross product in the second one. Knowledge is measured in information

units, while technology and gross product in monetary units.

The question arises (Court

and McIsaac, 2020): is the information approach to demographic dynamics

divorced from reality and is it possible to calibrate the corresponding model?

The answer to this question is one of the objectives of this work. As for the

reality and prospects of such an approach, we can refer to the work (Dolgonosov, 2020), in which a general

global-scale model was proposed, including economic, environmental, demographic

and information components, and which was successfully calibrated using

extensive empirical data.

In connection with the development of artificial

intelligence, a dilemma has arisen about how to describe the presence of

intelligent machines, whether to include them among the producers of knowledge,

thereby expanding the number , or to continue to believe that knowledge is

produced by people, and the machine is still only a tool that helps them in the

production of knowledge. Sadovnichy, Akaev and Korotayev (2022) develop the former

approach, believing that intelligent machines can now be considered producers

of knowledge and hence included in the number along with humans. This is a promising direction

of research, especially given the rapid development of AI. But for now,

following the analysis of Akaev and Sadovnichii (2021), we will remain with the

traditional approach, according to which it is people who produce knowledge,

while intelligent machines only help them in this matter. Then the effect of AI

manifests itself through an increase in the amount of knowledge and a

corresponding increase in human productivity.

The above-mentioned productivity functions proposed

by various authors require verification based on empirical material. To this

end, we revisit the issue of productivity as a function of knowledge and verify

the theoretical results using literature data.

Another nontrivial problem is how to determine the

amount of knowledge. The most consistent approach is to estimate memory

capacity that knowledge takes up. However, at the moment such information is

unlikely to exist. Meanwhile, there is evidence that digital memory is rapidly

increasing over time, in what appears to be a global information explosion

during the digitization period (1986-2007 onwards) (Hilbert,

2014).

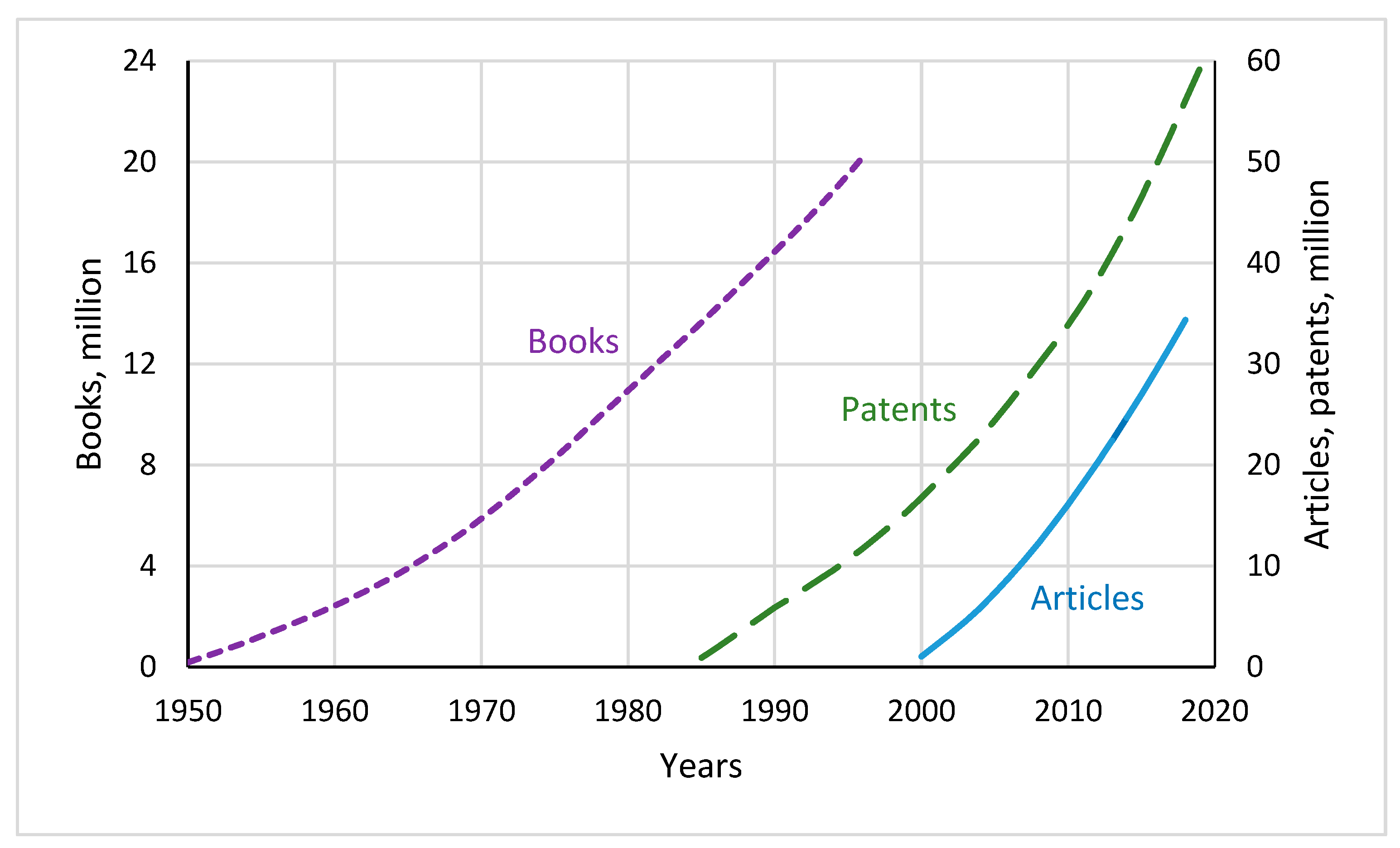

It should be expected that the total memory

capacity far exceeds knowledge capacity due to repeated replication of useful

information, especially in graphic and video formats. In this situation, it is

necessary to use data on different types of knowledge representation, such as

patent applications, original articles and books. These data have been largely

cleared of duplication. Knowledge production should be assessed separately for

each type. Below we use this approach.

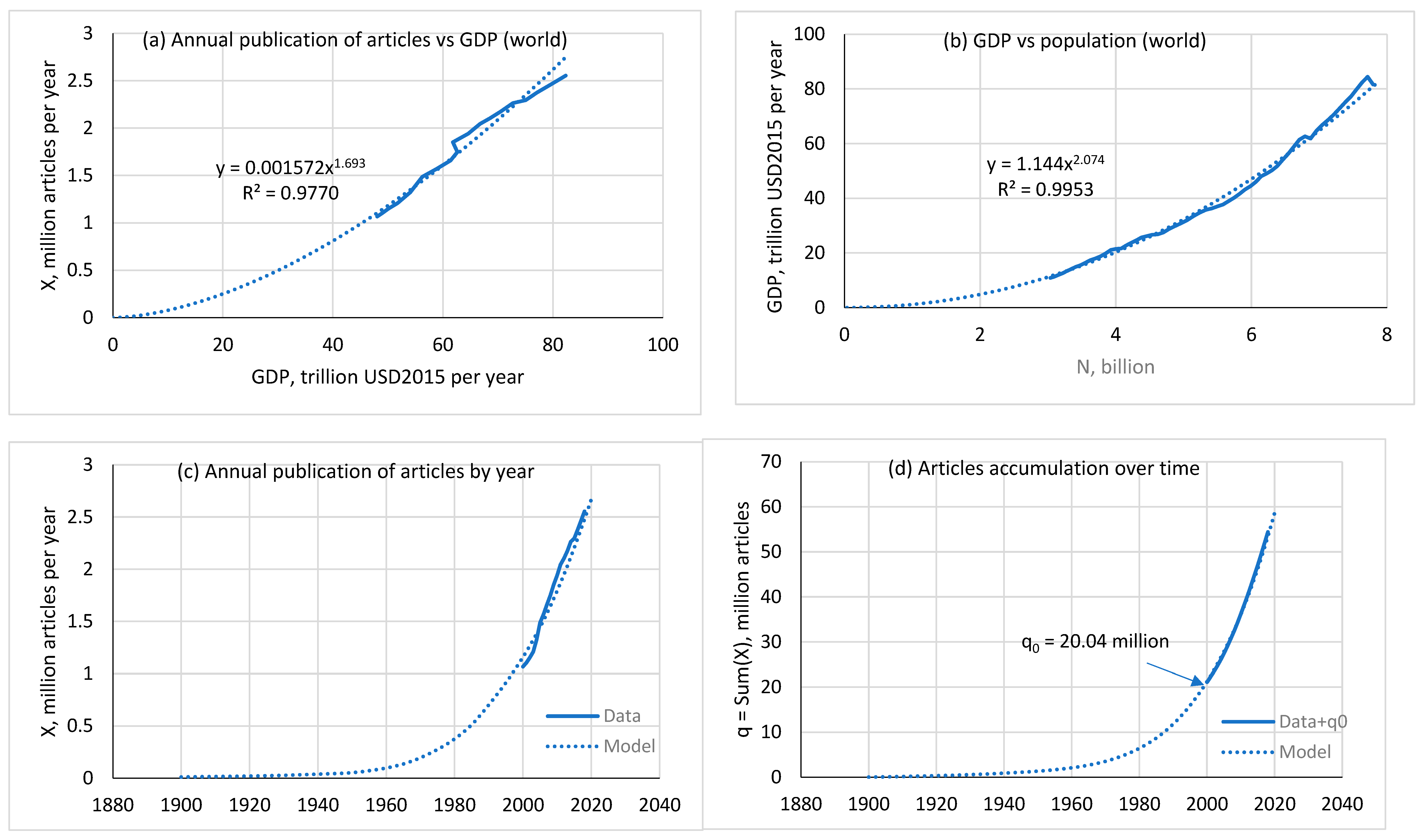

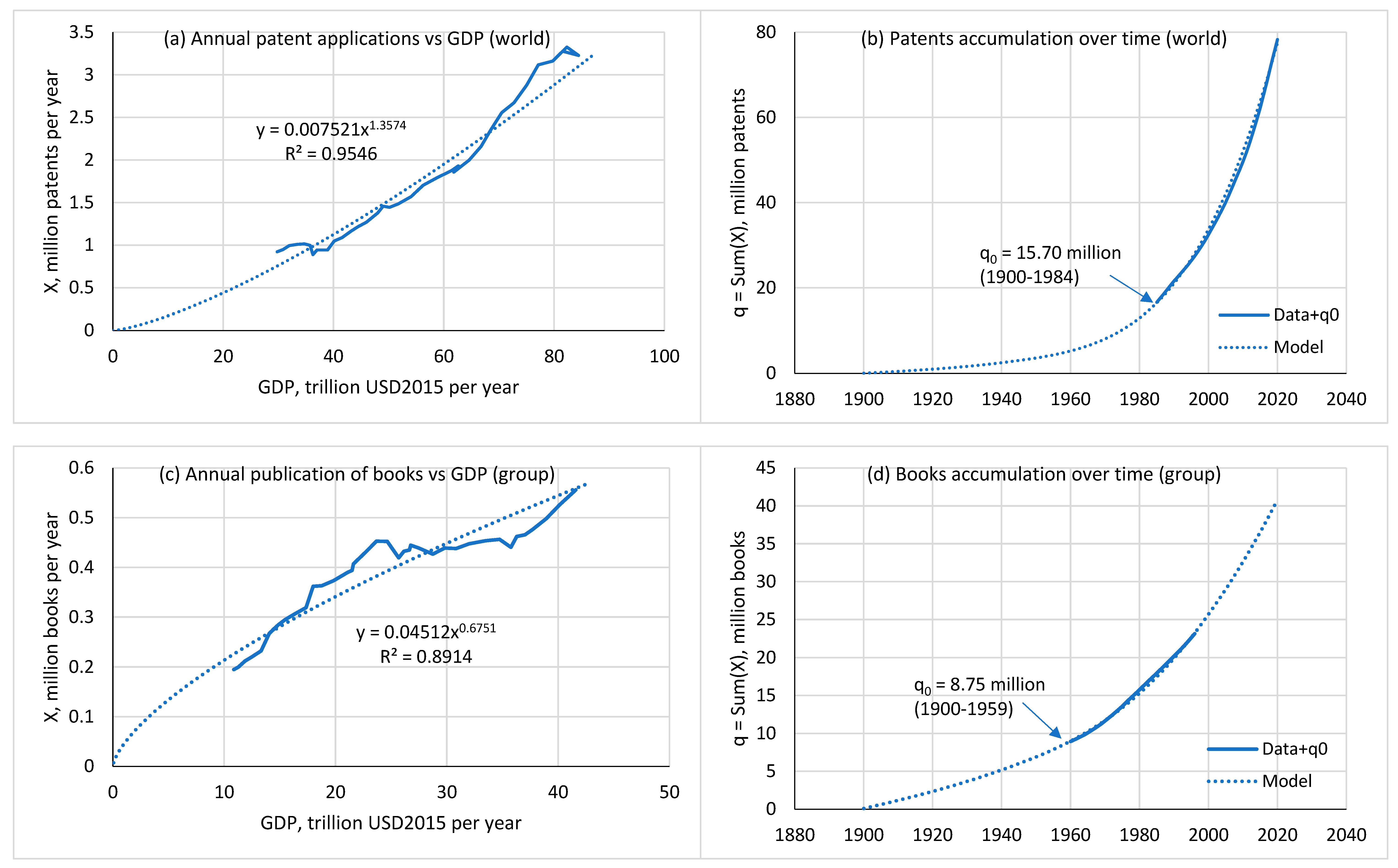

4. Results and Discussion

The parameter values found as a result of model

calibration are presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 6. The accuracy of matching the model

with the data is very high, as evidenced by the determination coefficient

, the values of which are close to 1.

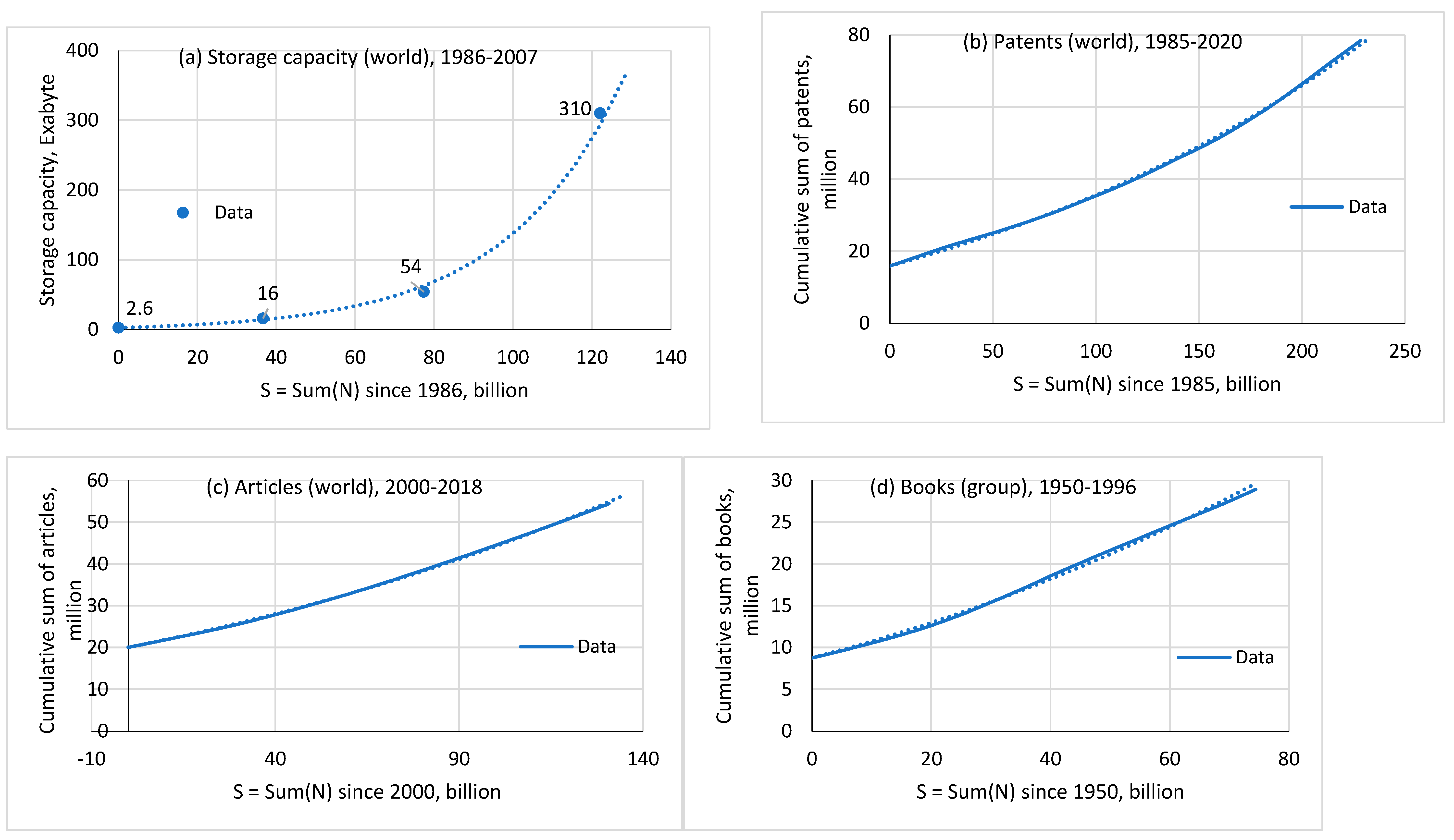

4.1. Storage Capacity

The best fit of equation (16) to the data is

achieved at

, when a linear productivity (21) is the case:

where

is measured in Exabytes (only in this case),

and

are measured in billion people×year.

4.2. Patents

Kong et al. (2023) found that patents created absorb

much more knowledge from patents than from articles. Then we can neglect the

contribution of articles to the production of patents.

The number of patents is also best suited to the

linear case

, see (21), and obeys equation (31) with parameters

(33) having values

here and further in (35)

is measured in million texts.

4.3. Articles

Equation (16) when applied to the number of

articles in scientific and technical journals gives the best result in the

asymptotic limit

, which corresponds to equation (24) at

(

Table 1).

Equation (24) can be rewritten as

where

4.4. Books

For the number of new book titles (in all genres of

literature), the best result corresponds to the same

asymptotic formula (35) as for articles, with

and parameter values

4.5. Memory Capacity Assessment

To estimate the memory capacity (in bytes) occupied

by patents, articles and books, we use estimates of the average sizes of these

texts. Analysis of samples of several hundred patents and articles yields an

average size of approximately 1.5 Megabytes per patent (or article). Similarly

for books, we get an average size of 14 Megabytes per book. The latest storage

capacity value of 310 Exabytes dates back to 2007. Memory capacity estimates

for various types of knowledge representation as of 2007 are shown in

Table 2.

We see that the memory capacity occupied by each

text type is 6 orders of magnitude less than the total storage capacity. The

storage capacity is filled primarily with visual information (photos, films,

archives of TV programs, video surveillance, digitized museum exhibits, etc.).

It is also necessary to consider the repeated duplication of visual and textual

information, copied by almost every interested user to their devices. The need

to store such immense information causes an accelerated growth in the capacity

of storage devices, which is what we are seeing in reality (

Figure 6a).

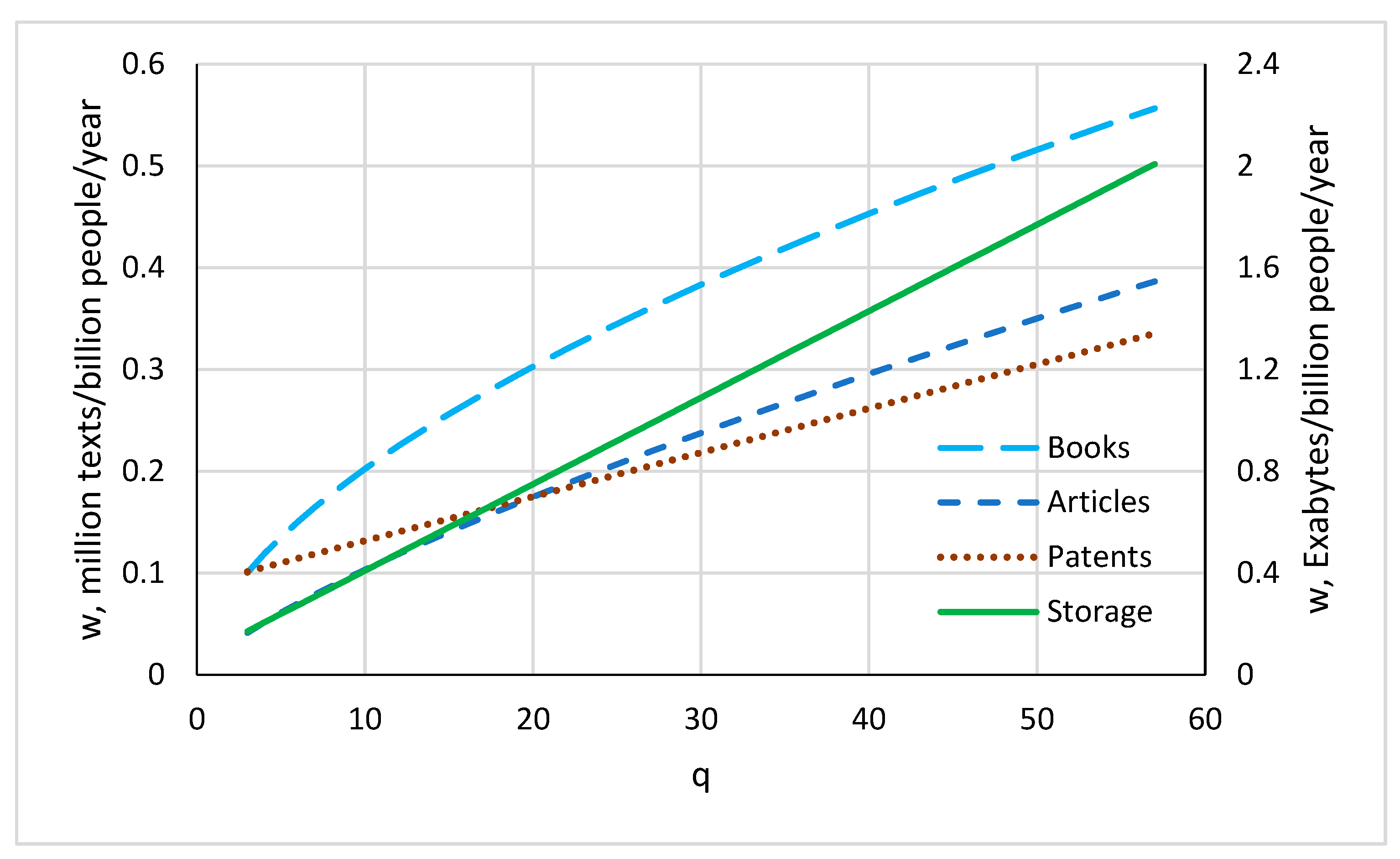

4.6. Productivity Increase

According to the adopted model, productivity increases for all types of texts studied here (patents, articles and books), as depicted in

Figure 7. With an increase in knowledge by 5 times (

from 10 to 50 units), productivity increases by 2.3, 2.5 and 3.4 times for patents, books and articles, respectively. For the same increase in storage capacity, productivity increases by 4.3 times. So, productivity grows more slowly than knowledge.

Table 3 shows that during the observation period productivity increases by 2 – 2.7 times. Unlike knowledge, the information storage stands apart: its capacity

increased over the observation period by 113 times, and its productivity

increased by 63 times. We see that memory is expanding much faster than new texts (patents, articles, books) are created. Apparently, producing storage devices is a simpler process than creating new knowledge.

4.7. Constant Productivity Approximation

Consider the condition under which the constant productivity approximation may be acceptable. According to (13), this condition is

, where

is a threshold value. Referring to

Table 1, we find

for storage and

for patents. The former corresponds to 1983, the latter to 1989.

For articles and books, their productivity and accumulated knowledge obey nonlinear laws (25) and (35). As shown above (see (20)), constant productivity causes a linear increase in knowledge. Equation (35) can be linearized if the condition is satisfied, then . According to (36) and (38), for articles and for books. The threshold value is reached in 2016 for articles and in 1982 for books.

So, we can use the constant productivity approximation (20) as long as we do not get too close to the specified dates, staying in the range of where the condition for storage and patents or for articles and books holds. To summarize, as we approach the 1980s, the constant productivity approximation loses its adequacy (for articles it happens later).

The dependence of knowledge production on population size (7), supplemented by the equation of knowledge dynamics, allows us to obtain the equation of demographic dynamics (Dolgonosov, 2016). The constant productivity approximation leads to the well-known hyperbolic law of world population growth (von Foerster et al., 1960), which operated for over a thousand years. However, deviations from this law become increasingly apparent as we approach the 1980s, which is associated with a significant accumulation of knowledge and an increase in productivity — it can no longer be taken as constant. This fact is usually considered as a demographic and technological phase transition (Korotayev et al., 2015; Grinin et al., 2020a, b), and at the same time it can be interpreted as a transition from a pre-information society, where the constant productivity approximation operates, to a more developed information society with advanced computer technologies and growing human productivity.

After the 1980s, personal computers became widespread and the information society continued to develop. Digital memory grew, reaching the level of analog memory and then surpassing it. The share of digital memory increased as follows: 0.8% in 1986, 3% in 1993, 25% in 2000, 94% in 2007 (Hilbert and López, 2011). The capacities of both types of memory became equal in 2003. Thus, the early 2000s can be considered a milestone in the maturation of digital civilization. Currently, the majority of world's technological memory is organized in the most accessible and fastest digital format.

5. Conclusion

The amount of knowledge correlates with the number of patents, articles and books published in the world over the entire previous period, which allowed us to trace the dynamics of knowledge accumulation. The production of knowledge depends on its amount and population size. This dependence plays a crucial role in knowledge dynamics and related demographic dynamics. The goal of this work was to find out the form of this dependence and check how well it corresponds to real data.

We have proposed a model in which the total rate of knowledge production is expressed as the product of average human productivity and population size. Productivity increases as knowledge accumulates and information technology advances. At the early stage of society development, knowledge is very scarce, but productivity is still not zero, which is a necessary condition for further development.

As knowledge grows, productivity gradually increases, reaching high values in a developed information society. In the asymptotic limit, when knowledge amount becomes large, productivity can be described by a power-law dependence on . To combine the extreme cases of an undeveloped society and a highly developed one, we described productivity by the interpolation dependence representing a linear form of raised to a certain power. This dependence generalizes important special cases where productivity can be a constant, linear, power or exponential function of knowledge.

In a developed society, information is stored primarily in digital format on various types of devices, which, together with analog memory, form the global informational storage. With the development of digital technology, storage capacity is rapidly increasing. To describe this process, we used the proposed model.

The model was calibrated using literature data for the world as a whole (applied to patents, articles and informational storage) and for the group of 30 countries (applied to books, given the lack of data for many countries). Good agreement with the data was achieved. The general dependence of human productivity on knowledge amount was reduced to two special cases: a linear function of for patents and storage capacity, and a power function of for articles and books.

The analysis showed that in a pre-information society, with a relatively small amount of knowledge, the constant productivity approximation can be used. The transition to a developed information society occurred in the 1980s. Productivity can no longer be considered constant: it grows with the accumulation of knowledge according to a linear law in the case of patents, and according to a power law in the case of articles and books.

Digital memory surpassed analog memory after 2003. The population's need for repeated duplication of useful information led to a rapid increase in the number of storage devices and, consequently, to an increase in the total capacity of informational storage, which by 2007 exceeded the memory capacity occupied by patents, articles and books by 6 orders of magnitude.

The results obtained open up an opportunity to advance in describing the dynamics of various forms of knowledge and predicting their development in the future.