1. Introduction

Over the past few years, fungal infections have emerged as a concern in the medical field, with several types gaining attention due to their rising prevalence, resistance to treatment, the cost and toxicity associated with most commonly used antifungal agents and impact on vulnerable populations [

1]. These infections, often caused by opportunistic fungi, can lead to serious health complications, particularly in individuals with weakened immune systems [

2].

One such infection is sporotrichosis, caused by fungi belonging to the genus

Sporothrix. This disease typically manifests as skin lesions that may eventually spread to lymph nodes. It is commonly associated with warm-blooded animals, including humans, dogs and, mainly, cats. Sporotrichosis is of particular concern in tropical and subtropical regions [

3].

Candidiasis is an infection resulting from yeast species within the

Candida genus. The most common species responsible for infections is

Candida albicans, even though other species, like

Candida glabrata and

Candida tropicalis, can also cause infections. Normally,

Candida lives in human body without causing harm. However, under certain conditions, such as changes in the body's immune system,

Candida can overgrow and lead to an infection [

4]. Another rising fungal infection is

Candida auris, a yeast resistant to multiple drugs that has emerged as a significant threat to the healthcare system. It can cause severe bloodstream infections, pneumonia, and infections in other parts of the body, often affecting critically ill or immunocompromised patients. The difficulty in diagnosing

Candida auris and its resistance to antifungal drugs have made it a growing challenge for healthcare professionals [

5].

Cryptococcosis is another significant fungal infection resulting from

Cryptococcus neoformans and

Cryptococcus gattii. This infection is most dangerous for people with compromised immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS. It primarily affects the lungs and can spread to the brain, leading to meningitis. The rise of cryptococcosis has been linked to environmental factors and the growing number of individuals living with HIV [

6].

These fungal infections underscore the importance of ongoing research, awareness, and effective treatment strategies, particularly as they continue to pose challenges in healthcare settings. Improved diagnostic techniques, early detection, and the search for novel antifungal agents are crucial in managing these infections and preventing their spread [

7].

Compounds synthesized by the research group, including those containing the thiazolyl hydrazone moiety, have demonstrated antifungal effects, making them promising leads for innovative drug candidates [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The high lipophilicity is one of the main limitations of this type of compounds [

12,

13]. The optimization of their chemical structure by introduction polar and ionizable substituents led to the development of a new series with more favorable pharmacokinetic properties, including a better absorption profile via the oral route. E,Z−Ethyl 2-(2-(2-(4-hydroxybutan-2-ylidene)-hydrazono)thiazol-4-yl)acetate (RJ44) was identified as the most promising compound of this class due to its potent activity against various species of Candida and Cryptococcus, low cytotoxicity and physicochemical properties suitable for clinical application [

14].

Continuing the search for RJ44 analogues aiming to obtain compounds with even better physicochemical properties, we described in this work the synthesis of a more hydrophilic thiazolyl hydrazone, as well as the evaluation of its antifungal activity, irritative potential, and determination of cytotoxicity, solubility and intestinal permeability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis

The analytical reagents were obtained from commercial sources, and used without purification. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using pre-coated 0.5 mm glass plates with a suspension of 8 g of silica gel 60 containing 13% w/w CaSO₄ (Sigma-Aldrich) in 19 mL of distilled water. The melting points (mp) were determined on a Microquimica MQAPF 301 apparatus. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE III HD 400 MHz spectrometer, using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as the internal. Chemical shifts are expressed in δ (ppm) scale and J values are given in Hz, being the multiplicity of signals referred to as singlet (s), triplet (t), and quartet (q). The synthesis and structural elucidation of thiosemicarbazone has been previously described in the literature [

14].

Synthesis of (E)-2-(2-(4-(2-Ethoxy-2-Oxoethyl)Thiazol-2-yl)Hydrazineylidene)-Propanoic Acid (RW3)

The thiazolylhydrazone RW3 was obtained by an equimolar reaction of the (2

E)-2-[2-(aminothioxomethyl)hydrazinylidene]propanoic acid [

14] (0.150 g, 0.93 mmol) and ethyl 4-chloroacetoacetate (126 µL, 0.93 mmol) dissolved in isopropyl alcohol (18 mL). The reaction mixture was kept under magnetic stirring at 80 °C for approximately 3 hours. The reaction was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) (eluent: ethyl acetate and 5 drops of acetic acid; developer: iodine vapor). At the end of the reaction, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and 18 mL of distilled water were added and the contents of the flask were transferred to a separatory funnel. Then, the mixture was extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 30 mL). The organic phase was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, filtered, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure. The resulting product was washed with 7 mL of diethyl ether, yielding RW3 as a light yellow solid (0.134 g, 53%). M.p.: 164.2-167.7 °C;

1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 6.77 (1H, s), 4.08 (2H, q, J = 7.2 Hz), 3.63 (2H, s), 2.05 (3H, s), 1.19 (3H, t, J = 7.2 Hz);

13C NMR (100 MHz, DMSO-d6): δ 169.9, 168.4, 165.6, 138.9, 107.7, 60.37, 36.6, 14.1, 12.7.

2.2. In Vitro Antifungal Assay

Broth microdilution testing was conducted following the guidelines in the CLSI document M27-A3 (2008) with modifications [

15]. Briefly, the following yeast were used in the present study:

Candida albicans SC5314,

Candida tropicalis ATCC 750,

Candidozyma (Candida)

auris COLO 01,

Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019,

Pichia kudravzevii (Candida krusei) ATCC 20298,

Cryptococcus gattii ATCC 24065,

C. neoformans ATCC 24067 and

Sporothrix brasiliensis (189). All fungus strains were stored at a temperature of -80°C. Before conducting the experiments, the strains were cultivated on Sabouraud dextrose agar (HiMedia, Mumbai, India) at 35°C to ensure their purity and viability. Yeast phase of

S. brasiliensis was grown on brain heart infusion agar (BHI; Difco, Detroit, MI, USA) with two successive passages of 7 days at 35 °C and CO

2 5% [

16]. Compounds were tested at concentrations of 0.125–250 µg/mL. For comparative antifungal controls, fluconazole (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), itraconazole (Sigma-Aldrich), and caspofungine (Sigma-Aldrich) were included. The plates were incubated at 35°C for 48 h for yeast and for 7 days for

S. brasiliensis at 35 °C and CO2 5%. The tests were performed in triplicate. The endpoints were determined visually by comparison with the endpoints of the drug-free growth-control well. The value of the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was defined as the lowest extract concentration at which the well was optically clear, and was expressed in µg/mL.

2.3. HET-CAM Assay

Gallus gallus domesticus eggs (n=3) with eighth day of embryonic development were incubated at 37 ± 2 °C and 50% humidity until the test. On the tenth day, the solutions of RW3 (100 µM), 1% DMSO in saline (diluent), 0.1 mol/L NaOH (positive control) and saline solution (negative control) were placed on the chorioallantoic membrane. Following the application of 300 µL of each solution, according to the German protocol [

17], the changes in the membrane were recorded for 300 s, indicating the time of onset of each observed phenomenon (hemorrhage, lysis and coagulation) and using the following formula to calculate the the Irritation Score (IS). Each experiment was repeated two times.

IS= (301- sH)/300 x 5 + (301-sL)/300 x 7 + (301-sC)/300 x 9 (I)

Where: H = hemorrhage, L - lysis, C = coagulation and s = start second

2.4. Saturation Shake-Flask Solubility Method

The equilibrium solubility of RW3 samples was assessed using the shake-flask method. The samples were dispersed in buffers described in the United States Pharmacopeia at pH values of 2.0, 4.5, and 6.8. For each reported solubility result, three independent shake-flask experiments were carried out in parallel. For each experiment, the solid sample was added carefully using a spatula to 2 mL of the aqueous buffer in a glass vial, while stirring until a heterogeneous system (solid sample and liquid) was obtained. The solution containing solid excess of the sample was then capped, and stirred at 37° C, 100 rpm, for 24h in orbital shaker (Tecnal, Campinas, Brazil). An aliquot of 1 mL of the suspension was centrifuged, and the supernatant was then collected and filtered through a 0.2 µm PVDF filter. The resulting solution was then diluted 200x in the mobile phase and the concentration of sample in each aliquot was measured by HPLC method. The RW3 concentrations were determinate by injections of 10 µL of the samples on HPLC a Waters Alliance system (New Castle, DE, USA). Chromatographic separations were obtained using a PhenoSphere-NEXT® 5 µm C18 column (150 mm; 4,6 mm; Phenomenex®) at 40° C. The mobile phase (1 mL/min) was composed of phosphate buffer 20 mM pH 4,0 and acetonitrile (50:50 v/v). The wavelength was set at 308 nm. The HPLC method employed was evaluated for linearity, precision, accuracy, and selectivity.

2.5. In Vitro Caco-2 Cytotoxicity Determinations

In vitro cytotoxicity assays were carried out following the protocol outlined in the ISO 10993-5 guideline (ISO, 2022) [

18]. The human colon carcinoma cell line, Caco-2 cells (from ATCC) were cultured in 96-well plates for 24 h at a seeding density of 2 x 104 cells/well. RW3 compound was dissolved in DMEM without phenol to prepare samples of 10; 25 and 50 µg/mL concentration. Six replicates of each concentration for RW3 were assessed. This range of concentrations was chosen for reasons associated with subsequent permeability tests. The experiments began by replacing the culture medium in each well with 100 µL of sample or control solutions, followed by a 4-hour incubation at 37°C in a CO2 incubator. Afterward, the solutions in each well were aspirated, and the cells were further incubated for 2 hours with 30 µL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL, Sigma–Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO, in DMEM and PBS buffer, 9:1 v/v). Next, formazan crystals were solubilized with 70 µL of isopropyl alcohol acidified with hydrochloric acid and quantified spectrophotometrically at 570 and 690 nm (Spectra Fluor plate reader, Tecan, Austria). Cell viability was calculated based on the measured absorbance relative to the absorbance of the cells exposed to the negative controls (DMEM), which represented 100% cell viability and for positive control was employed DMSO 50% in DMEM, which represented 0% cell viability.

2.6. In Vitro Caco-2 Permeability Assay

The Caco-2 cells (from ATCC) were cultured in 12-well Transwell® (Corning Incorporated, New York, NY) insert filters for 21 days at a seeding density of 5 x 10⁴ cells/cm² to achieve confluence and differentiation. The integrity of the monolayer was examined by measuring the transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) with an epithelial voltammeter Millicell-ERS (Merck SA - German). Only cell monolayers with a TEER above 300xcm2 were used for the transport assays.

Transport experiments were conducted by adding 10 µg/mL RW3 in HBSS buffer at pH 6.8 to the apical compartments of the Transwell® plates, while the basolateral buffer was maintained at pH 7.4. The plates were agitated in an orbital shaker at 37°C (100 rpm). Samples (100 µL) were collected from both the basolateral and apical sides at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 180 minutes. The apparent permeability coefficients (Papp, cm/s) were calculated using the following equation:

Papp= (VR / A x C0)/ (dC/dt)

where VR is the volume of the receiver compartment (basolateral or apical), DQ/Dt is the linear appearance rate of the compound on the receiver chamber (in ng/cm3/s), A is the membrane surface area (cm2) and C0 is the initial concentration in the donor compartment (ng/cm3). This calculation requires that the sink conditions are fulfilled; therefore, only receiver concentrations below 10% of the donor concentration were employed in the calculations.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Design and Synthesis of RW3

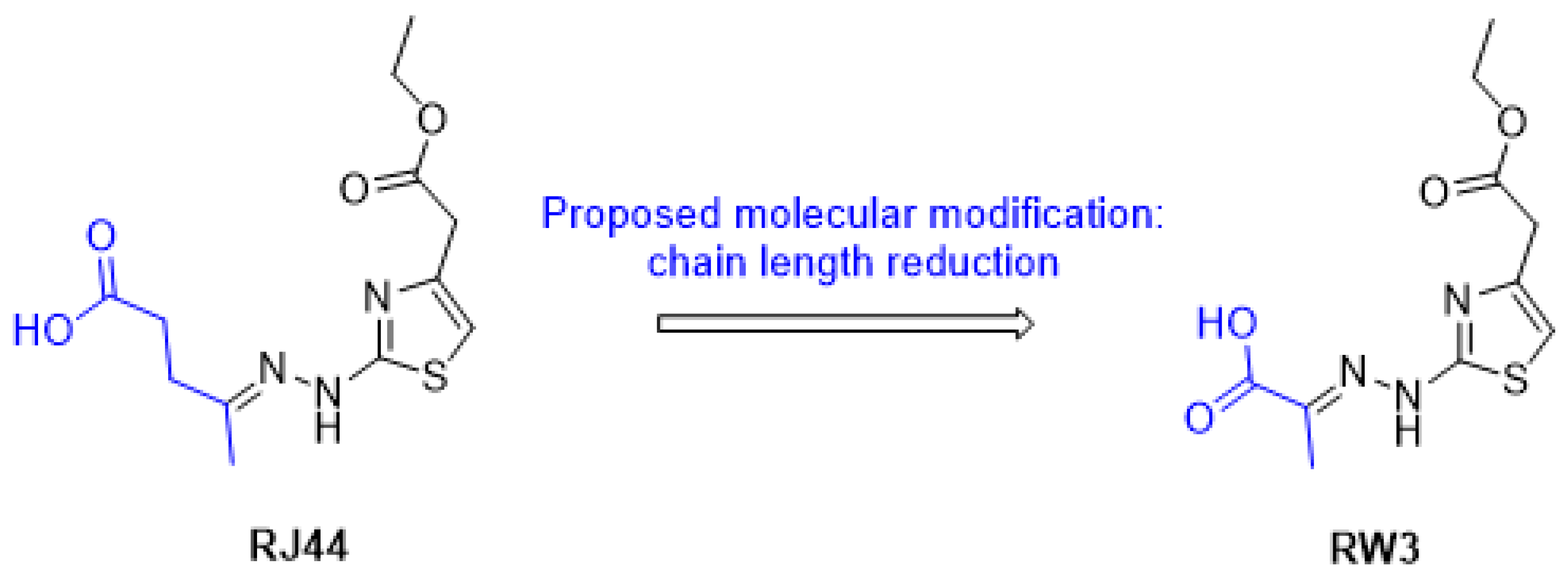

Based on the antifungal activity exhibited by

RJ44 and with the aim of improving its water solubility, we proposed reducing the side chain of the hydrazone portion from five carbons to three carbons, while leaving the rest of the molecule unchanged, as shown in

Figure 1. The reduction of the carbon chain is an efficient strategy for reducing the hydrophobicity of a molecule.

For comparison purposes, the logarithm of n-octanol/water partition coefficient (log Po/w) was predicted using the SwissADME web tool [

19], and, as expected, the logP value calculated for

RW3 (logP = 1.18) was lower than the value calculated for

RJ44 (logP = 1.57), indicating an increase in its hydrophilic character.

Considering the possible pharmacokinetic advantages of

RW3 over

RJ44, this compound was then synthesized in two steps from pyruvic acid and thiosemicarbazide using methodology previously described [

14].

3.2. Evaluation of the Antifungal Activity and Irritant Potential of RW3

In the

Table 1 are shown the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values of

RW3 against various fungal species. MIC is an important indicator of a compound's effectiveness in inhibiting fungal growth, and the results highlight the varying efficacy of

RW3 across different fungal species. The MIC values are expressed in micrograms per milliliter (µg/mL), and comparisons are made with the MIC values of standard antifungal agents like itraconazole, fluconazole, and caspofungin.

The results show that RW3 demonstrates a wide range of activity against different Candida species. Among the Candida strains tested, Candida albicans exhibited an MIC of 31.3 µg/mL, which is moderate when compared to the lower MIC observed for Candida auris (15.6 µg/mL) and Pichia kudravzevii (15.6 µg/mL). In contrast, Candida tropicalis and Candida parapsilosis displayed a higher MIC of 125 µg/mL, indicating a lower sensitivity to RW3. These variations in MIC could be attributed to genetic differences among Candida species, affecting their susceptibility to antifungal agents.

Notably, the Cryptococcus species, Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii, displayed relatively low MIC values of 3.9 µg/mL and 7.8 µg/mL, respectively. These results suggest that RW3 is particularly effective against Cryptococcus species, which is promising considering the clinical significance of Cryptococcus infections, especially in immunocompromised individuals. The lower MIC values for Cryptococcus species suggest a strong potential for RW3 as a therapeutic agent against these fungi.

RW3 showed an MIC of 15.6 µg/mL against Sporothrix brasiliensis, a significant pathogen in the Sporothrix complex, which is known to cause sporotrichosis. Compared to the MIC for itraconazole (0.5 µg/mL), RW3's activity appears weaker against this species. However, it is still noteworthy that RW3 may offer an alternative treatment option, particularly in cases of resistance to conventional antifungal agents.

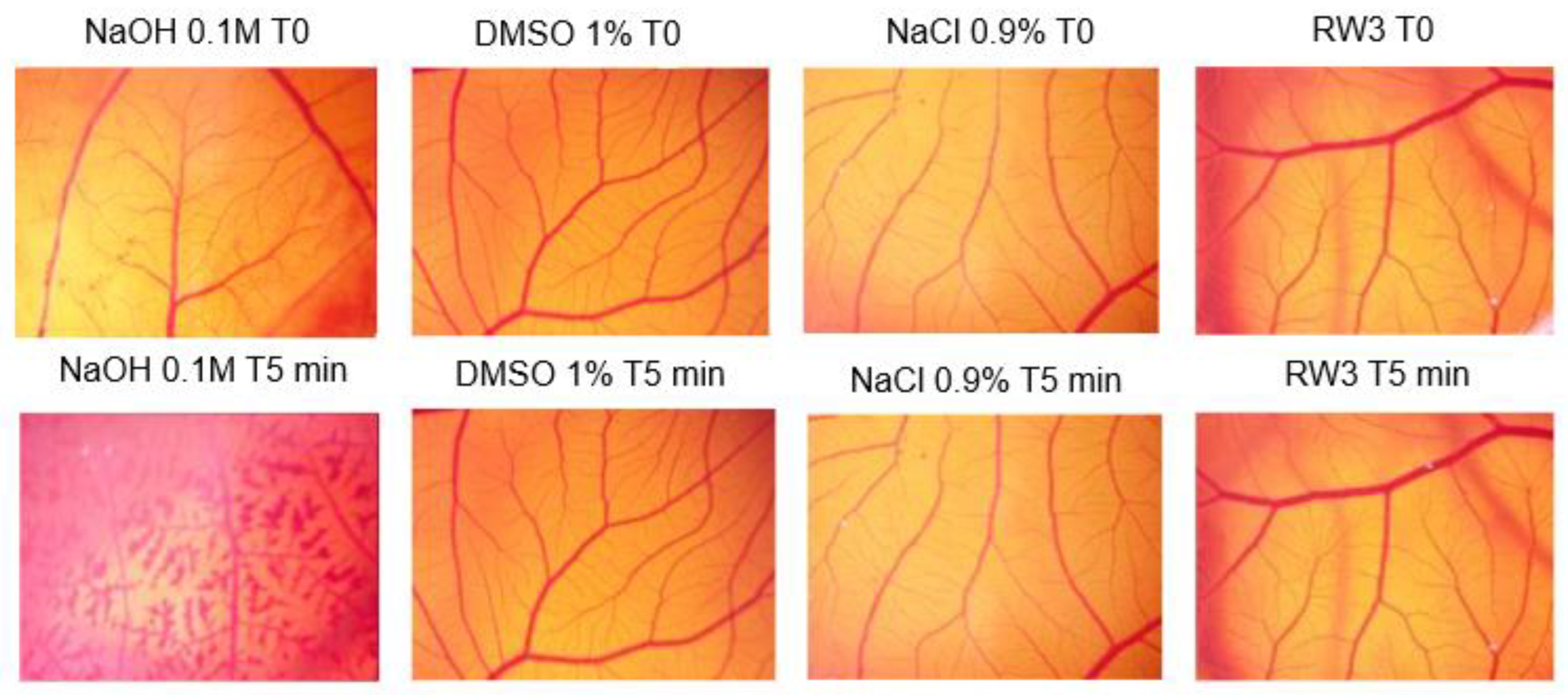

Additionally, to assess the possibility of irritation caused by

RW3, the Hen's Egg Test on the Chorioallantoic Membrane (HET-CAM) was performed. The HET-CAM assay is an in vivo semiquantitative test to evaluate the anti-inflammatory potential, anti-irritant properties as well as ocular toxicity of compounds/formulations. The benefits of this test include its simplicity, rapid execution, ease of use, and relatively low cost [

20,

21]. For the classification of the irritation potential (

Table 2), the arithmetic mean of the six eggs was used, and the score was categorized as: non-irritant (0.0 to 0.9); mildly Irritant (1.0 to 4.9); moderately irritant (5.0 to 8.9) and severely irritant (9.0 to 21.0) [

22].

The CAM images at the beginning and end of the experiment are presented in

Figure 2. It is possible to note the extensive hemorrhage caused by NaOH, the absence of irritation caused by the diluent and negative control (saline) and the little irritation caused by

RW3.

The irritant potential of

RW3 is similar to that presented by the negative control (saline solution), that is, the compound has practically no potential for irritation. The HET-CAM assay is sensitive to evaluate agents and is well established for screening their ability to reduce inflammation [

21,

23].

3.3. Saturation Shake-Flask Solubility Method

The determination of solubility under physiological conditions, particularly considering the different pH levels throughout the gastrointestinal tract, is one of the most important biopharmaceutical parameters that must be generated during the early stages of developing a new drug for oral administration. In this study, the solubility determination of

RW3 was carried out using the miniaturized shake flask test, as only a small amount of the compound under investigation was available. In the literature, there are publications that have successfully employed the miniaturized test [

24,

25].

The solubility results (S0) experimentally obtained for

RW3 in buffers at pH 2.0, 4.5, and 6.8 are presented in

Table 3. It was observed that

RW3 exhibited increasing solubility with rising pH, in the order of 0.67 mg/mL, 1.01 mg/mL, and 2.76 mg/mL at pH 2.0, 4.5, and 6.8, respectively.

According to the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) [

26], a substance is classified as having high solubility when the ratio between the maximum daily administered dose and its intrinsic solubility (S0) under physiological pH conditions results in a value less than 250 mL, meaning that this dose can dissolve in 250 mL of aqueous medium.

The WHO, in its Biowaiver Guidance based on the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS), states that when the solubilities of a substance differ across the three evaluated pH levels, the reference value for solubility classification should be the most critical value, i.e., the lowest solubility. In the case of

RW3, this corresponds to the solubility at pH 2.0 [

27].

Since RW3 is in the preclinical stage of development, nothing definitive can be stated regarding the potential therapeutic dose to classify it as having high or low solubility. However, by extrapolating a possible dose that would meet the criteria for high solubility classification, i.e., Class 1 of the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS), a maximum daily dose of 168 mg can be considered as borderline. In other words, if the effective therapeutic daily dose required is less than 168 mg, the Dose/S0 ratio would be less than 250, thereby classifying it as a high-solubility compound.

3.4. In Vitro Caco-2 Cytotoxicity Determinations

The cytotoxicity of the RW3 in Caco-2 cells in vitro is shown as a percentage of cell viability compared to the negative (100%) and positive controls, as measured by the MTT assay (

Figure 3).

As shown in

Figure 3,

RW3 was tested at concentrations of 10, 25, and 50 µg/mL, resulting in cell viability rates of 100%, 88%, and 86%, respectively. According to the ISO 10993-5 standard, which defines a material as non-cytotoxic if cell viability exceeds 70%,

RW3 demonstrated no cytotoxic effects at any of the tested concentrations.

3.5. In Vitro Caco-2 Permeability Assay

Human intestinal absorption of new drug candidates during the early stages of development is frequently evaluated by assessing the permeation of the drug across a monolayer of Caco-2 cells. Caco-2 cells are a well-established human epithelial colon carcinoma cell line that serves as a reliable in vitro model for studying intestinal drug absorption [

28].

Permeability studies using Caco-2 cells are typically conducted in two primary directions: from the apical side (facing the intestinal lumen) to the basolateral (blood-facing) side, referred to as influx (A-B), and in the reverse direction, from basolateral to apical, termed efflux (B-A). The comparison of the apparent permeability coefficients (Papp) in these two directions provides critical insights into the involvement of active transport mechanisms, whether absorptive or secretory.

Papp for

RW3 evaluated are presented in

Table 4. That value (Papp A-B = 23,08 x 10-6 cm/s) showed that would be characterized as a high permeability compound (Papp > 10 x 10-6 cm/s) according to the Biopharmaceutical Classification System (SCB) [

26,

29,

30].

The net flux ratio, which was lower than 2.0 (0.76) for the compounds, suggested that there was no significant transport in the efflux direction [

28].

Research that correlated the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp) with the percentage of human bioavailability (F%) suggests that compound

RW3 is unlikely to encounter absorption issues in the gastrointestinal tract, provided it achieves adequate solubilization in physiological fluids. Research establishing a strong correlation between Papp values and human bioavailability has been conducted since the initial use of the model for predicting permeability [

31]. Recently, new approaches have been employed to evaluate the predictive power of studies in cellular models and correlate these findings with computational models we believe that the current in silico model is a dependable tool for identifying the most promising compounds with high intestinal permeability in the early stages of drug discovery and could be utilized in the development of provisional BCS classification [

32,

33].

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, RW3 shows promise as an effective antifungal agent, particularly against Cryptococcus species and Candida auris, with potential as an alternative treatment for antifungal-resistant infections. The compound exhibited favorable physicochemical properties, including improved water solubility, high intestinal permeability, and low cytotoxicity, suggesting its potential for oral administration. Additionally, RW3 demonstrated minimal irritant potential, highlighting its safety for further development. These findings indicate that RW3 could serve as a valuable potential treatment for systemic fungal infections, providing an alternative to traditional antifungal agents, particularly in light of increasing resistance. Future studies focusing on the optimization of its structure and clinical testing will be crucial to confirm its therapeutic potential and establish it as a viable treatment option in the fight against resistant fungal pathogens.

Author Contributions

R.B.O. Conceptualization, formal analysis, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition; W.C.M. Investigation, synthesis, writing – original draft preparation; C.P.S.M. Investigation, formal analysis; S.J. Responsible for coordinating, organizing, and analyzing antifungal activity tests; J.V.V.P. Responsible for performing antifungal activity tests; J.E.G. Investigation, cytotoxicity, solubility and permeability studies, writing—original draft preparation; G.H.O.C. Investigation, cytotoxicity and permeability studies; V.L.P. Investigation, solubility studies. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received funding from FAPEMIG (Rede Mineira de Pesquisa e Inovação em Química Medicinal – RMQM, grant REDE-00110-23), R.B.O. holds a CNPq Researcher Scholarship (Bolsa de Produtividade em Pesquisa, grant 302041/2022-2), C.P.S.M holds a FAPEMIG for Research and Technological Development Incentive Scholarship (grant BIP-00029-24).

Data Availability Statement

The data set generated and analyzed during this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable requirements.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES), and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG). The authors would also like to express their gratitude to the Laboratório de Ressonância Magnética Nuclear de Alta Resolução of the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (LAREMAR – UFMG) for their collaboration in obtaining the NMR spectra.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ATCC |

American Type Culture Collection |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium |

| HET-CAM |

Hen's egg test on chorioallantoic membrane |

| MIC |

Minimal Inhibitory Concentration |

| NMR |

Nuclear magnetic resonance |

| TEER |

Transepithelial electrical resistance |

| TLC |

Thin-layer chromatography |

| TMS |

Tetramethylsilane |

| |

|

References

- Kontoyiannis, D.P. Antifungal Resistance: An Emerging Reality and A Global Challenge. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 216, 431–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thambugala, K.M.; Daranagama, D.A.; Tennakoon, D.S.; Jayatunga, D.P.W.; Hongsanan, S.; Xie, N. Humans vs. Fungi: An Overview of Fungal Pathogens against Humans. Pathogens 2024, 13, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orofino-Costa, R.; de Macedo, P.M.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Bernardes-Engemann, A.R. Sporotrichosis: An update on epidemiology, etiopathogenesis, laboratory and clinical therapeutics. An. Bras. De Dermatol. 2017, 92, 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira Santos, G.C.; Vasconcelos, C.C.; Lopes, A.J.O.; et al. Candida Infections and Therapeutic Strategies: Mechanisms of Action for Traditional and Alternative Agents. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sears, D.; Schwartz, B.S. Candida auris: An emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 63, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maziarz, E.K.; Perfect, J.R. Cryptococcosis. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 30, 179–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firacative, C.; Trilles, L.; Meyer, W. Recent Advances in Cryptococcus and Cryptococcosis. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Sá, N.P.; de Barros, P.P.; Junqueira, J.C.; Vaz, J.A.; de Oliveira, R.B.; Rosa, C.A.; Santos, D.A.; Johann, S. Thiazole derivatives act on virulence factors of Cryptococcus spp. Med. Mycol. 2019, 57, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, C.I.; de Souza, I.G.; Borelli, B. M.; Silvério Matos, T. T.; Santos Teixeira, I. N.; Ramos, J.P.; de Souza Fagundes, E.M.; de Oliveira Fernandes, P.; Maltarollo, V.G.; Johann, S.; et al. Synthesis, molecular modeling studies and evaluation of antifungal activity of a novel series of thiazole derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 151, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sá, N.P.; Lino, C.I.; Fonseca, N.C.; Borelli, B.M.; Ramos, J.P.; Souza-Fagundes, E.M.; Rosa, C.A.; Santos, D.A.; de Oliveira, R.B.; Johann, S. Thiazole compounds with activity against Cryptococcus gattii and Cryptococcus neoformans in vitro. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 102, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barreto Cruz, L.I.; Finamore Lopes, L.F.; de Camargo Ribeiro, F.; de Sá, N.P.; Lino, C.I.; Tharmalingam, N.; de Oliveira, R.B.; Rosa, C.A.; Mylonakis, E.; Fuchs, B.B.; Johann, S. Anti-Candida albicans Activity of Thiazolylhydrazone Derivatives in Invertebrate and Murine Models. J. Fungi 2018, 4, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, I.R.; Braga, A.V.; de Abreu Gloria, M.B.; de Resende Machado, R.; César, I.D.C.; de Oliveira, R.B. Preclinical pharmacokinetic study of a new thiazolyl hydrazone derivative with antifungal activity in mice plasma by LC-MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 2020, 1149, 122180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, I.R.; Castro E Souza, M.A.; Machado, R.R.; de Oliveira, R.B.; Leite, E.A.; César, I.D.C. Enhancing oral bioavailability of an antifungal thiazolylhydrazone derivative: Development and characterization of a self-emulsifying drug delivery system. Int. J. Pharm. 2024, 655, 124011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cândido Oliveira, N.J.; Dos Santos Júnior, V. S.; Pierotte, I.C.; Teixeira Leocádio, V.A.; de Andrade Santana, L.F.; de Lima Marques, G.V.; Protti, I.F.; Pinto Braga, S.F.; Kohlhoff, M.; Freitas, T.R.; et al. Discovery of Lead 2-Thiazolylhydrazones with Broad-Spectrum and Potent Antifungal Activity. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 16628–16645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rex, J.H.; Alexander, B.D.; Andes, D.; Arthington-Skaggs, B.; Brown, S.D.; Chaturvedi, V.; Ghannoum, M.A.; Espinel-Ingroff, A.; Knapp, C.C.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; et al. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts; Approved Standard, 3rd ed. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI): Wayne, PA, USA, 2008; ISBN 1-56238-666-2. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchotene, K.O.; Brandolt, T.M.; Klafke, G.B.; Poester, V.R.; Xavier, M.O. In vitro susceptibility of Sporothrix brasiliensis: Comparison of yeast and mycelial phases. Med. Mycol. 2017, 55, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICCVAM. ICCVAM Test Method Evaluation Report: Current Validation Status of In Vitro Test Methods Proposed for Identifying Eye Injury Hazard Potential of Chemicals and Products. NIH Publication No. 10-7553; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences: Research Triangle Park, NC, USA, 2010; Available online: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/iccvam/docs/ocutox_docs/invitro-2010/tmer-vol2.pdf.

- ISO 10993-5: 2022 Biological evaluation of medical devices Part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity.

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinl chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viera, L.M.A.L.; Silva, R.S.; da Silva, C.C.; Presgrave, O.A.F.; Villas Boas, M.H.S. Comparison of the different protocols of the Hen's Egg Test-Chorioallantoic Membrane (HET-CAM) by evaluating the eye irritation potential of surfactants. Toxicol. In Vitro 2022, 78, 105255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Öztürk, A.A.; Çevikelli, T.; Tilki, E.K.; Güven, U.M.; Kıyan, H.T. Ketorolac Tromethamine Loaded Nano-Spray Dried Nanoparticles: Preparation, Characterization, Cell Viability, COL1A1 Gene Simulation and Determination of Anti-inflammatory Activity by In vivo HET-CAM Assay. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2023, 20, 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, I.F.; Gaspar Cordeiro, L.R.; Valadares, M.C. ATLAS DO MÉTODO HET CAM: Protocolo ilustrado aplicado à avaliação de toxicidade ocular. Available online: https://educare.fiocruz.br/ (accessed on 7 December 2024).

- Bender, C.; Partecke, L.I.; Kindel, E.; Döring, F.; Lademann, J.; Heidecke, C.D.; Kramer, A.; Hübner, N.O. The modified HET-CAM as a model for the assessment of the inflammatory response to tissue tolerable plasma. Toxicol. In Vitro 2011, 25, 530–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glomme, A.; März, J.; Dressman, J.B. Comparison of a Miniaturized Shake–Flask Solubility Method with Automated Potentiometric Acid/Base Titrations and Calculated Solubilities. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005, 94, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veseli, A.; Kristl, A.; Akelj, S. Proof-of-concept for a miniaturized shake-flask biopharmaceutical solubility determination by sonic mixing. Pharmazie. 2020, 75, 626–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amidon, G.L.; Lennernas, H.; Shah, V.P.; Crison, J.R. A theoretical basis for a biopharmaceutic drug classification: the correlation of in vitro drug product dissolution and in vivo bioavailability. Pharm. Res. 1995, 12, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Expert Committee on Specifications for Pharmaceutical Preparations- Annex 7 Guideline on Biopharmaceutics Classification System -Based Biowaivers. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 1052, 2024.

- Hubatsch, I.; Ragnarsson, E.G.E.; Artursson, P. Determination of drug permeability and prediction of drug absorption in Caco-2 monolayers. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 2111–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yee, S. In vitro permeability across Caco-2 cells (colonic) can predict in vivo (small intestinal) absorption in man--fact or myth. Pharm. Res. 1997, 14, 763–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kus, M.; Ibragimow, I.; Piotrowska-Kempisty, H. Caco-2 Cell Line Standardization with Pharmaceutical Requirements and In Vitro Model Suitability for Permeability Assays. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarc, T.; Novak, M.; Hevir, N.; Rižner, T.L.; Kreft, M.E.; Kristan, K. Demonstrating suitability of the Caco-2 cell model for BCS-based biowaiver according to the recent FDA and ICH harmonised guidelines. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 71, 1231–1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcón-Cano, G.; Molina, C.; Cabrera-Pérez, M.Á. Reliable Prediction of Caco-2 Permeability by Supervised Recursive Machine Learning Approaches. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X. QSPR Model for Caco-2 Cell Permeability Prediction Using a Combination of HQPSO and Dual-RBF Neural Network. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 42938–4295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).