Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis Activation During Fetal Life

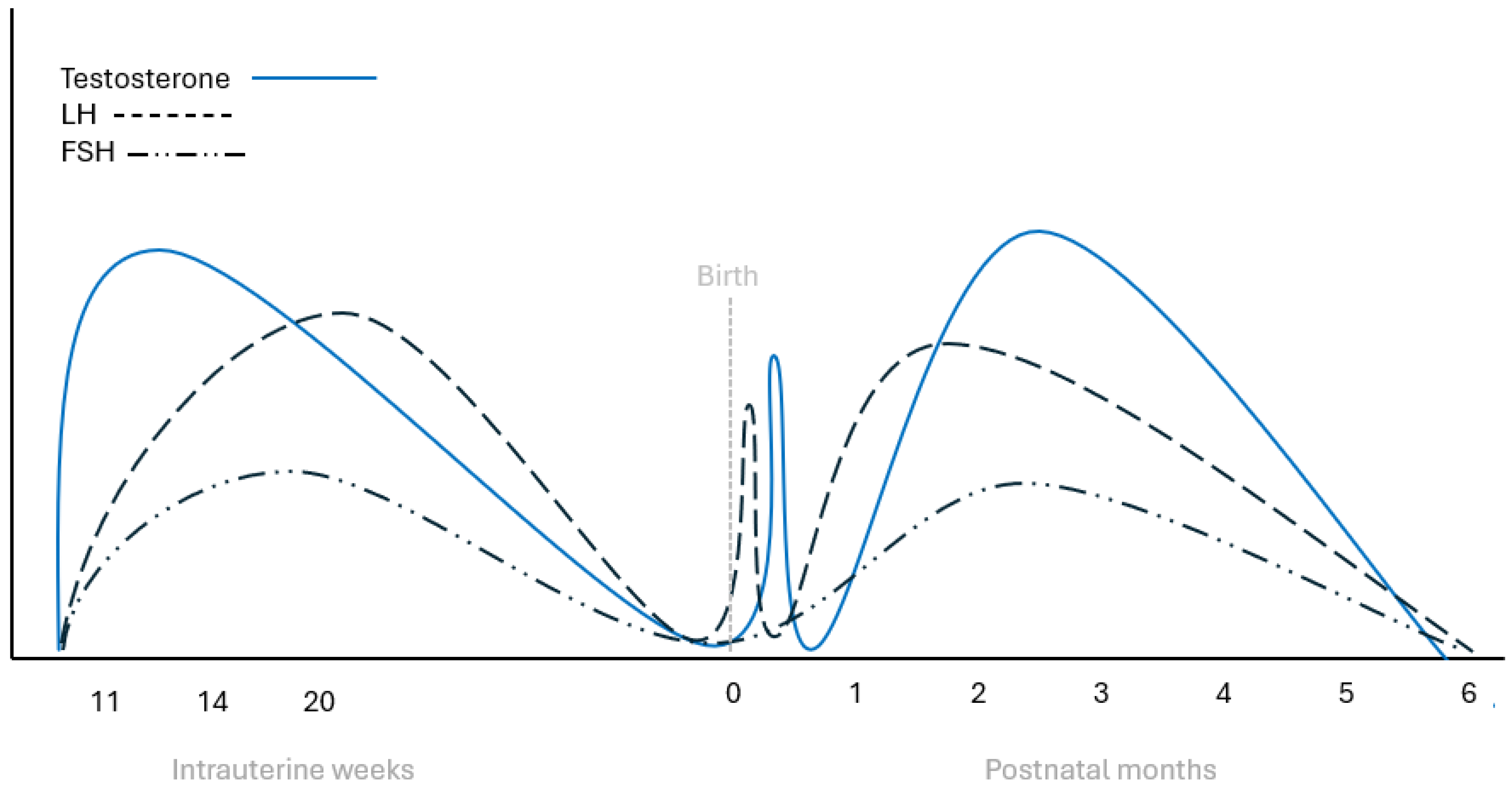

3. Mini Puberty in Males

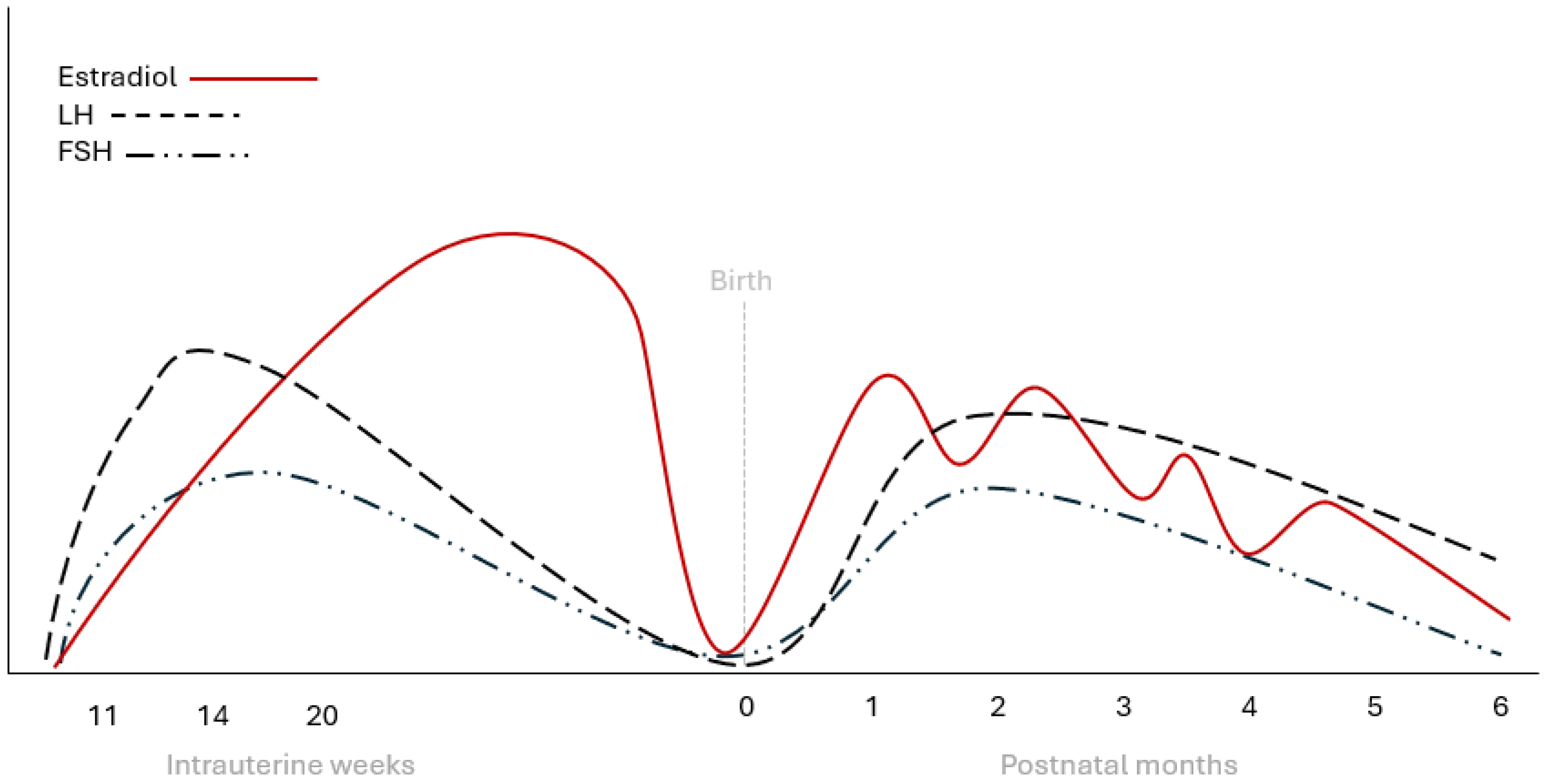

4. Mini Puberty in Females

5. Mini Puberty in Premature and Small-for-Gestational Age Infants

6. Mini-Puberty, Linear Growth and Body Composition

7. Mini-Puberty and Neurodevelopment

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMH | anti-Mullerian hormone |

| HPG | hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal |

| FSH | follicle-stimulating hormone |

| LH | luteinizing hormone |

| SGA | small-for-gestational age |

| GnRH | gonadotropin releasing hormone |

| KNDy | Kisspeptin-Neurokinin B-Dynorphin |

| hCG | Human chorionic gonadotropin |

References

- Grinspon, R.P.; Bergadá, I.; Rey, R.A. Male Hypogonadism and Disorders of Sex Development. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020, 11, 211. [CrossRef]

- Sheng, J.A.; Bales, N.J.; Myers, S.A.; Bautista, A.I.; Roueinfar, M.; Hale, T.M.; Handa, R.J. The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis: Development, Programming Actions of Hormones, and Maternal-Fetal Interactions. Front Behav Neurosci 2020, 14, 601939. [CrossRef]

- Kuiri-Hänninen, T.; Sankilampi, U.; Dunkel, L. Activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in infancy: minipuberty. Horm Res Paediatr 2014, 82, 73-80. [CrossRef]

- Lanciotti, L.; Cofini, M.; Leonardi, A.; Penta, L.; Esposito, S. Up-To-Date Review About Minipuberty and Overview on Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal Axis Activation in Fetal and Neonatal Life. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 410. [CrossRef]

- Kiviranta, P.; Kuiri-Hänninen, T.; Saari, A.; Lamidi, M.L.; Dunkel, L.; Sankilampi, U. Transient Postnatal Gonadal Activation and Growth Velocity in Infancy. Pediatrics 2016, 138. [CrossRef]

- Hines, M.; Spencer, D.; Kung, K.T.; Browne, W.V.; Constantinescu, M.; Noorderhaven, R.M. The early postnatal period, mini-puberty, provides a window on the role of testosterone in human neurobehavioural development. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2016, 38, 69-73. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, R.; Dwyer, A.; Seminara, S.B.; Pitteloud, N.; Kaiser, U.B.; Crowley, W.F., Jr. Human GnRH deficiency: a unique disease model to unravel the ontogeny of GnRH neurons. Neuroendocrinology 2010, 92, 81-99. [CrossRef]

- Schwanzel-Fukuda, M.; Crossin, K.L.; Pfaff, D.W.; Bouloux, P.M.; Hardelin, J.P.; Petit, C. Migration of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) neurons in early human embryos. J Comp Neurol 1996, 366, 547-557. [CrossRef]

- Maeda, K.; Ohkura, S.; Uenoyama, Y.; Wakabayashi, Y.; Oka, Y.; Tsukamura, H.; Okamura, H. Neurobiological mechanisms underlying GnRH pulse generation by the hypothalamus. Brain Res 2010, 1364, 103-115. [CrossRef]

- Uenoyama, Y.; Nagae, M.; Tsuchida, H.; Inoue, N.; Tsukamura, H. Role of KNDy Neurons Expressing Kisspeptin, Neurokinin B, and Dynorphin A as a GnRH Pulse Generator Controlling Mammalian Reproduction. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021, 12, 724632. [CrossRef]

- Velasco, I.; Franssen, D.; Daza-Dueñas, S.; Skrapits, K.; Takács, S.; Torres, E.; Rodríguez-Vazquez, E.; Ruiz-Cruz, M.; León, S.; Kukoricza, K.; et al. Dissecting the KNDy hypothesis: KNDy neuron-derived kisspeptins are dispensable for puberty but essential for preserved female fertility and gonadotropin pulsatility. Metabolism 2023, 144, 155556. [CrossRef]

- Beltramo, M.; Dardente, H.; Cayla, X.; Caraty, A. Cellular mechanisms and integrative timing of neuroendocrine control of GnRH secretion by kisspeptin. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2014, 382, 387-399. [CrossRef]

- Tena-Sempere, M. Hypothalamic KiSS-1: the missing link in gonadotropin feedback control? Endocrinology 2005, 146, 3683-3685. [CrossRef]

- Clements, J.A.; Reyes, F.I.; Winter, J.S.; Faiman, C. Studies on human sexual development. III. Fetal pituitary and serum, and amniotic fluid concentrations of LH, CG, and FSH. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1976, 42, 9-19. [CrossRef]

- Schwanzel-Fukuda, M.; Pfaff, D.W. Origin of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone neurons. Nature 1989, 338, 161-164. [CrossRef]

- Pilavdzic, D.; Kovacs, K.; Asa, S.L. Pituitary morphology in anencephalic human fetuses. Neuroendocrinology 1997, 65, 164-172. [CrossRef]

- Guimiot, F.; Chevrier, L.; Dreux, S.; Chevenne, D.; Caraty, A.; Delezoide, A.L.; de Roux, N. Negative fetal FSH/LH regulation in late pregnancy is associated with declined kisspeptin/KISS1R expression in the tuberal hypothalamus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012, 97, E2221-2229. [CrossRef]

- Massa, G.; de Zegher, F.; Vanderschueren-Lodeweyckx, M. Serum levels of immunoreactive inhibin, FSH, and LH in human infants at preterm and term birth. Biol Neonate 1992, 61, 150-155. [CrossRef]

- Takagi, S.; Yoshida, T.; Tsubata, K.; Ozaki, H.; Fujii, T.K.; Nomura, Y.; Sawada, M. Sex differences in fetal gonadotropins and androgens. J Steroid Biochem 1977, 8, 609-620. [CrossRef]

- Debieve, F.; Beerlandt, S.; Hubinont, C.; Thomas, K. Gonadotropins, prolactin, inhibin A, inhibin B, and activin A in human fetal serum from midpregnancy and term pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000, 85, 270-274. [CrossRef]

- Casarini, L.; Santi, D.; Brigante, G.; Simoni, M. Two Hormones for One Receptor: Evolution, Biochemistry, Actions, and Pathophysiology of LH and hCG. Endocr Rev 2018, 39, 549-592. [CrossRef]

- Pitetti, J.L.; Calvel, P.; Romero, Y.; Conne, B.; Truong, V.; Papaioannou, M.D.; Schaad, O.; Docquier, M.; Herrera, P.L.; Wilhelm, D.; et al. Insulin and IGF1 receptors are essential for XX and XY gonadal differentiation and adrenal development in mice. PLoS Genet 2013, 9, e1003160. [CrossRef]

- O'Rahilly, R. The timing and sequence of events in the development of the human reproductive system during the embryonic period proper. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1983, 166, 247-261. [CrossRef]

- Reyes, F.I.; Boroditsky, R.S.; Winter, J.S.; Faiman, C. Studies on human sexual development. II. Fetal and maternal serum gonadotropin and sex steroid concentrations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1974, 38, 612-617. [CrossRef]

- O'Shaughnessy, P.J.; Baker, P.J.; Monteiro, A.; Cassie, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Fowler, P.A. Developmental changes in human fetal testicular cell numbers and messenger ribonucleic acid levels during the second trimester. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 92, 4792-4801. [CrossRef]

- Kurilo, L.F. Oogenesis in antenatal development in man. Hum Genet 1981, 57, 86-92. [CrossRef]

- Cole, B.; Hensinger, K.; Maciel, G.A.; Chang, R.J.; Erickson, G.F. Human fetal ovary development involves the spatiotemporal expression of p450c17 protein. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006, 91, 3654-3661. [CrossRef]

- Forabosco, A.; Sforza, C. Establishment of ovarian reserve: a quantitative morphometric study of the developing human ovary. Fertil Steril 2007, 88, 675-683. [CrossRef]

- Baker, T.G.; Scrimgeour, J.B. Development of the gonad in normal and anencephalic human fetuses. J Reprod Fertil 1980, 60, 193-199. [CrossRef]

- Rohayem, J.; Alexander, E.C.; Heger, S.; Nordenström, A.; Howard, S.R. Mini-Puberty, Physiological and Disordered: Consequences, and Potential for Therapeutic Replacement. Endocr Rev 2024, 45, 460-492. [CrossRef]

- Forest, M.G.; Cathiard, A.M.; Bertrand, J.A. Evidence of testicular activity in early infancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1973, 37, 148-151. [CrossRef]

- Corbier, P.; Dehennin, L.; Castanier, M.; Mebazaa, A.; Edwards, D.A.; Roffi, J. Sex differences in serum luteinizing hormone and testosterone in the human neonate during the first few hours after birth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1990, 71, 1344-1348. [CrossRef]

- Bergadá, I.; Milani, C.; Bedecarrás, P.; Andreone, L.; Ropelato, M.G.; Gottlieb, S.; Bergadá, C.; Campo, S.; Rey, R.A. Time course of the serum gonadotropin surge, inhibins, and anti-Müllerian hormone in normal newborn males during the first month of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006, 91, 4092-4098. [CrossRef]

- Busch, A.S.; Ljubicic, M.L.; Upners, E.N.; Fischer, M.B.; Raket, L.L.; Frederiksen, H.; Albrethsen, J.; Johannsen, T.H.; Hagen, C.P.; Juul, A. Dynamic Changes of Reproductive Hormones in Male Minipuberty: Temporal Dissociation of Leydig and Sertoli Cell Activity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022, 107, 1560-1568. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, H.; Schwarz, H.P. Serum concentrations of LH and FSH in the healthy newborn. Eur J Endocrinol 2000, 143, 213-215. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, A.M.; Toppari, J.; Haavisto, A.M.; Petersen, J.H.; Simell, T.; Simell, O.; Skakkebaek, N.E. Longitudinal reproductive hormone profiles in infants: peak of inhibin B levels in infant boys exceeds levels in adult men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998, 83, 675-681. [CrossRef]

- Boas, M.; Boisen, K.A.; Virtanen, H.E.; Kaleva, M.; Suomi, A.M.; Schmidt, I.M.; Damgaard, I.N.; Kai, C.M.; Chellakooty, M.; Skakkebaek, N.E.; et al. Postnatal penile length and growth rate correlate to serum testosterone levels: a longitudinal study of 1962 normal boys. Eur J Endocrinol 2006, 154, 125-129. [CrossRef]

- Dhayat, N.A.; Dick, B.; Frey, B.M.; d'Uscio, C.H.; Vogt, B.; Flück, C.E. Androgen biosynthesis during minipuberty favors the backdoor pathway over the classic pathway: Insights into enzyme activities and steroid fluxes in healthy infants during the first year of life from the urinary steroid metabolome. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2017, 165, 312-322. [CrossRef]

- Bay, K.; Virtanen, H.E.; Hartung, S.; Ivell, R.; Main, K.M.; Skakkebaek, N.E.; Andersson, A.M.; Toppari, J. Insulin-like factor 3 levels in cord blood and serum from children: effects of age, postnatal hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis activation, and cryptorchidism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 92, 4020-4027. [CrossRef]

- Burton, E.; Abeydeera, S.A.; Sarila, G.; Cho, H.J.; Wu, S.; Tien, M.Y.; Hutson, J.; Li, R. The role of gonadotrophins in gonocyte transformation during minipuberty. Pediatr Surg Int 2020, 36, 1379-1385. [CrossRef]

- Simorangkir, D.R.; Marshall, G.R.; Plant, T.M. Sertoli cell proliferation during prepubertal development in the rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta) is maximal during infancy when gonadotropin secretion is robust. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003, 88, 4984-4989. [CrossRef]

- Chemes, H.E.; Rey, R.A.; Nistal, M.; Regadera, J.; Musse, M.; González-Peramato, P.; Serrano, A. Physiological androgen insensitivity of the fetal, neonatal, and early infantile testis is explained by the ontogeny of the androgen receptor expression in Sertoli cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008, 93, 4408-4412. [CrossRef]

- Rey, R.A. Mini-puberty and true puberty: differences in testicular function. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2014, 75, 58-63. [CrossRef]

- Aksglaede, L.; Sørensen, K.; Boas, M.; Mouritsen, A.; Hagen, C.P.; Jensen, R.B.; Petersen, J.H.; Linneberg, A.; Andersson, A.M.; Main, K.M.; et al. Changes in anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) throughout the life span: a population-based study of 1027 healthy males from birth (cord blood) to the age of 69 years. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010, 95, 5357-5364. [CrossRef]

- Winter, J.S.; Hughes, I.A.; Reyes, F.I.; Faiman, C. Pituitary-gonadal relations in infancy: 2. Patterns of serum gonadal steroid concentrations in man from birth to two years of age. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1976, 42, 679-686. [CrossRef]

- Kuiri-Hänninen, T.; Kallio, S.; Seuri, R.; Tyrväinen, E.; Liakka, A.; Tapanainen, J.; Sankilampi, U.; Dunkel, L. Postnatal developmental changes in the pituitary-ovarian axis in preterm and term infant girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, 3432-3439. [CrossRef]

- Kuiri-Hänninen, T.; Haanpää, M.; Turpeinen, U.; Hämäläinen, E.; Seuri, R.; Tyrväinen, E.; Sankilampi, U.; Dunkel, L. Postnatal ovarian activation has effects in estrogen target tissues in infant girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013, 98, 4709-4716. [CrossRef]

- Bidlingmaier, F.; Strom, T.M.; Dörr, H.G.; Eisenmenger, W.; Knorr, D. Estrone and estradiol concentrations in human ovaries, testes, and adrenals during the first two years of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1987, 65, 862-867. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, H.L.; Shapiro, M.A.; Mandel, F.S.; Shapiro, M.L. Normal ovaries in neonates and infants: a sonographic study of 77 patients 1 day to 24 months old. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1993, 160, 583-586. [CrossRef]

- Courant, F.; Aksglaede, L.; Antignac, J.P.; Monteau, F.; Sorensen, K.; Andersson, A.M.; Skakkebaek, N.E.; Juul, A.; Bizec, B.L. Assessment of circulating sex steroid levels in prepubertal and pubertal boys and girls by a novel ultrasensitive gas chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010, 95, 82-92. [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, Y.; Cha, R.; Horn-Ommen, J.; O'Brien, P.; Simmons, P.S. Establishment of normative data for the amount of breast tissue present in healthy children up to two years of age. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2010, 23, 305-311. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, I.M.; Chellakooty, M.; Haavisto, A.M.; Boisen, K.A.; Damgaard, I.N.; Steendahl, U.; Toppari, J.; Skakkebaek, N.E.; Main, K.M. Gender difference in breast tissue size in infancy: correlation with serum estradiol. Pediatr Res 2002, 52, 682-686. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, R.H.; Umbach, D.M.; Parad, R.B.; Stroehla, B.; Rogan, W.J.; Estroff, J.A. US assessment of estrogen-responsive organ growth among healthy term infants: piloting methods for assessing estrogenic activity. Pediatr Radiol 2011, 41, 633-642. [CrossRef]

- Devillers, M.M.; Mhaouty-Kodja, S.; Guigon, C.J. Deciphering the Roles & Regulation of Estradiol Signaling during Female Mini-Puberty: Insights from Mouse Models. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Tapanainen, J.; Koivisto, M.; Vihko, R.; Huhtaniemi, I. Enhanced activity of the pituitary-gonadal axis in premature human infants. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1981, 52, 235-238. [CrossRef]

- Shinkawa, O.; Furuhashi, N.; Fukaya, T.; Suzuki, M.; Kono, H.; Tachibana, Y. Changes of serum gonadotropin levels and sex differences in premature and mature infant during neonatal life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1983, 56, 1327-1331. [CrossRef]

- Kuiri-Hänninen, T.; Seuri, R.; Tyrväinen, E.; Turpeinen, U.; Hämäläinen, E.; Stenman, U.H.; Dunkel, L.; Sankilampi, U. Increased activity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis in infancy results in increased androgen action in premature boys. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011, 96, 98-105. [CrossRef]

- Nagai, S.; Kawai, M.; Myowa-Yamakoshi, M.; Morimoto, T.; Matsukura, T.; Heike, T. Gonadotropin levels in urine during early postnatal period in small for gestational age preterm male infants with fetal growth restriction. J Perinatol 2017, 37, 843-847. [CrossRef]

- Pepe, G.; Calafiore, M.; Velletri, M.R.; Corica, D.; Valenzise, M.; Mondello, I.; Alibrandi, A.; Wasniewska, M.; Aversa, T. Minipuberty in born small for gestational age infants: A case control prospective pilot study. Endocrine 2022, 76, 465-473. [CrossRef]

- Kerkhof, G.F.; Leunissen, R.W.; Willemsen, R.H.; de Jong, F.H.; Stijnen, T.; Hokken-Koelega, A.C. Influence of preterm birth and birth size on gonadal function in young men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009, 94, 4243-4250. [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, V.H.; Weber, R.F.; de Jong, F.H.; Hokken-Koelega, A.C. Testis function in prepubertal boys and young men born small for gestational age. Horm Res 2008, 70, 357-363. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, R.B.; Vielwerth, S.; Larsen, T.; Greisen, G.; Veldhuis, J.; Juul, A. Pituitary-gonadal function in adolescent males born appropriate or small for gestational age with or without intrauterine growth restriction. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007, 92, 1353-1357. [CrossRef]

- Sedin, G.; Bergquist, C.; Lindgren, P.G. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in preterm infants. Pediatr Res 1985, 19, 548-552. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.L.; Jamli, F.M. Preterm ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome presenting as clitoromegaly in a premature female infant. Arch Dis Child 2022, 107, 166-167. [CrossRef]

- Mosallanejad, A.; Tabatabai, S.; Shakiba, M.; Alaei, M.R.; Saneifard, H. A Rare Case of Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome in a Preterm Infant. J Clin Diagn Res 2016, 10, Sd07-sd08. [CrossRef]

- Altuntas, N.; Turkyilmaz, C.; Yuce, O.; Kulali, F.; Hirfanoglu, I.M.; Onal, E.; Ergenekon, E.; Koç, E.; Bideci, A.; Atalay, Y. Preterm ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome presented with vaginal bleeding: a case report. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2014, 27, 355-358. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Chen, C.; Di, T.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, R.; Chen, S.; Qian, Y. Clinical characteristics of preterm ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: seven cases from China and 14 cases from the literature. Gynecol Endocrinol 2019, 35, 819-824. [CrossRef]

- Fields, D.A.; Gilchrist, J.M.; Catalano, P.M.; Giannì, M.L.; Roggero, P.M.; Mosca, F. Longitudinal body composition data in exclusively breast-fed infants: a multicenter study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011, 19, 1887-1891. [CrossRef]

- Fomon, S.J.; Nelson, S.E. Body composition of the male and female reference infants. Annu Rev Nutr 2002, 22, 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, G.S.; Girma, T.; Wells, J.C.; Kæstel, P.; Leventi, M.; Hother, A.L.; Michaelsen, K.F.; Friis, H. Body composition from birth to 6 mo of age in Ethiopian infants: reference data obtained by air-displacement plethysmography. Am J Clin Nutr 2013, 98, 885-894. [CrossRef]

- Jain, V.; Kurpad, A.V.; Kumar, B.; Devi, S.; Sreenivas, V.; Paul, V.K. Body composition of term healthy Indian newborns. Eur J Clin Nutr 2016, 70, 488-493. [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.M.; Kaar, J.L.; Ringham, B.M.; Hockett, C.W.; Glueck, D.H.; Dabelea, D. Sex differences in infant body composition emerge in the first 5 months of life. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2019, 32, 1235-1239. [CrossRef]

- Chachlaki, K.; Le Duc, K.; Storme, L.; Prevot, V. Novel insights into minipuberty and GnRH: Implications on neurodevelopment, cognition, and COVID-19 therapeutics. J Neuroendocrinol 2024, 36, e13387. [CrossRef]

- Kung, K.T.; Browne, W.V.; Constantinescu, M.; Noorderhaven, R.M.; Hines, M. Early postnatal testosterone predicts sex-related differences in early expressive vocabulary. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2016, 68, 111-116. [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, M.V.; Ashwin, E.; Auyeung, B.; Chakrabarti, B.; Taylor, K.; Hackett, G.; Bullmore, E.T.; Baron-Cohen, S. Fetal testosterone influences sexually dimorphic gray matter in the human brain. J Neurosci 2012, 32, 674-680. [CrossRef]

- Hines, M.; Constantinescu, M.; Spencer, D. Early androgen exposure and human gender development. Biol Sex Differ 2015, 6, 3. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).