Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

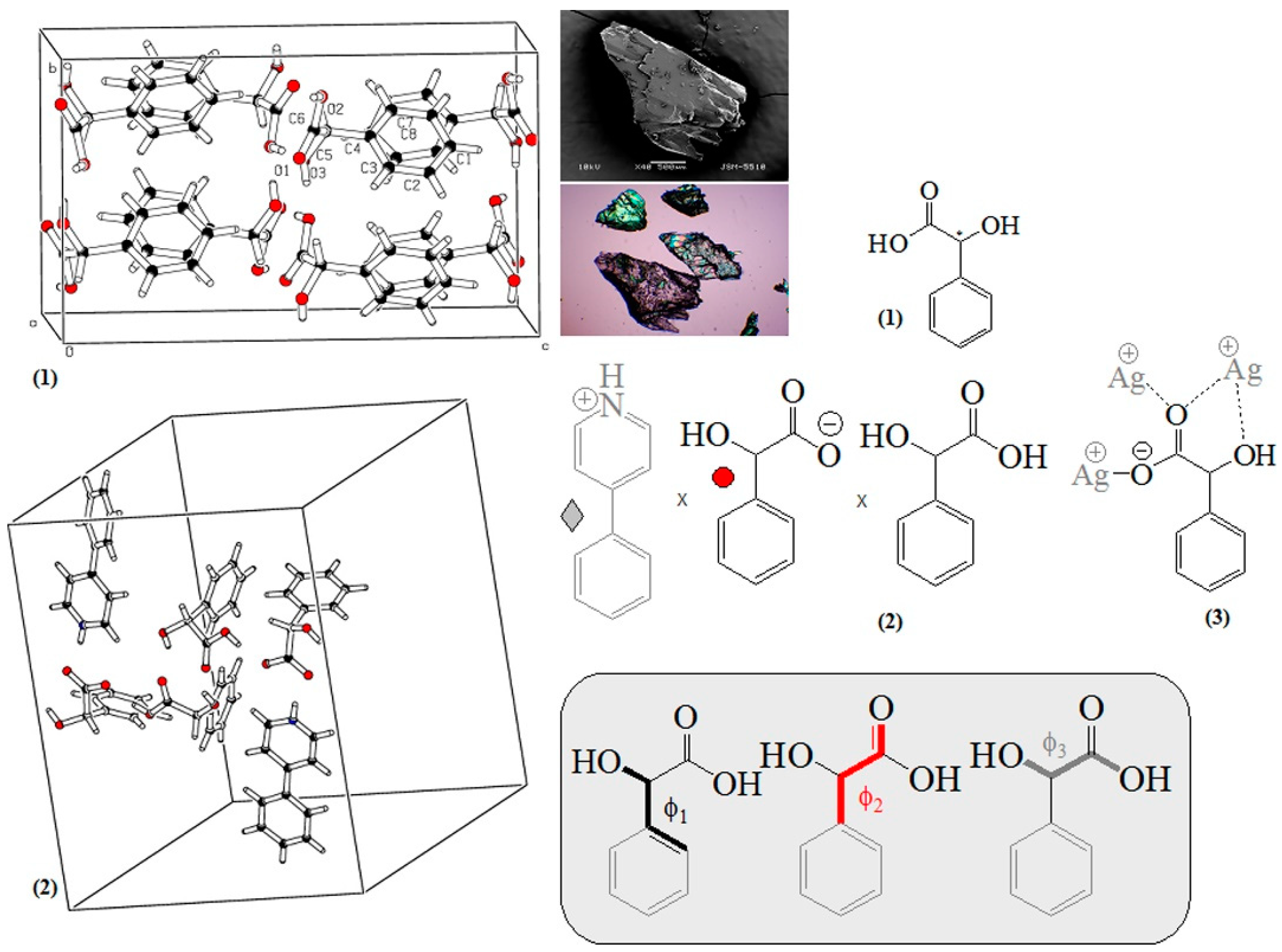

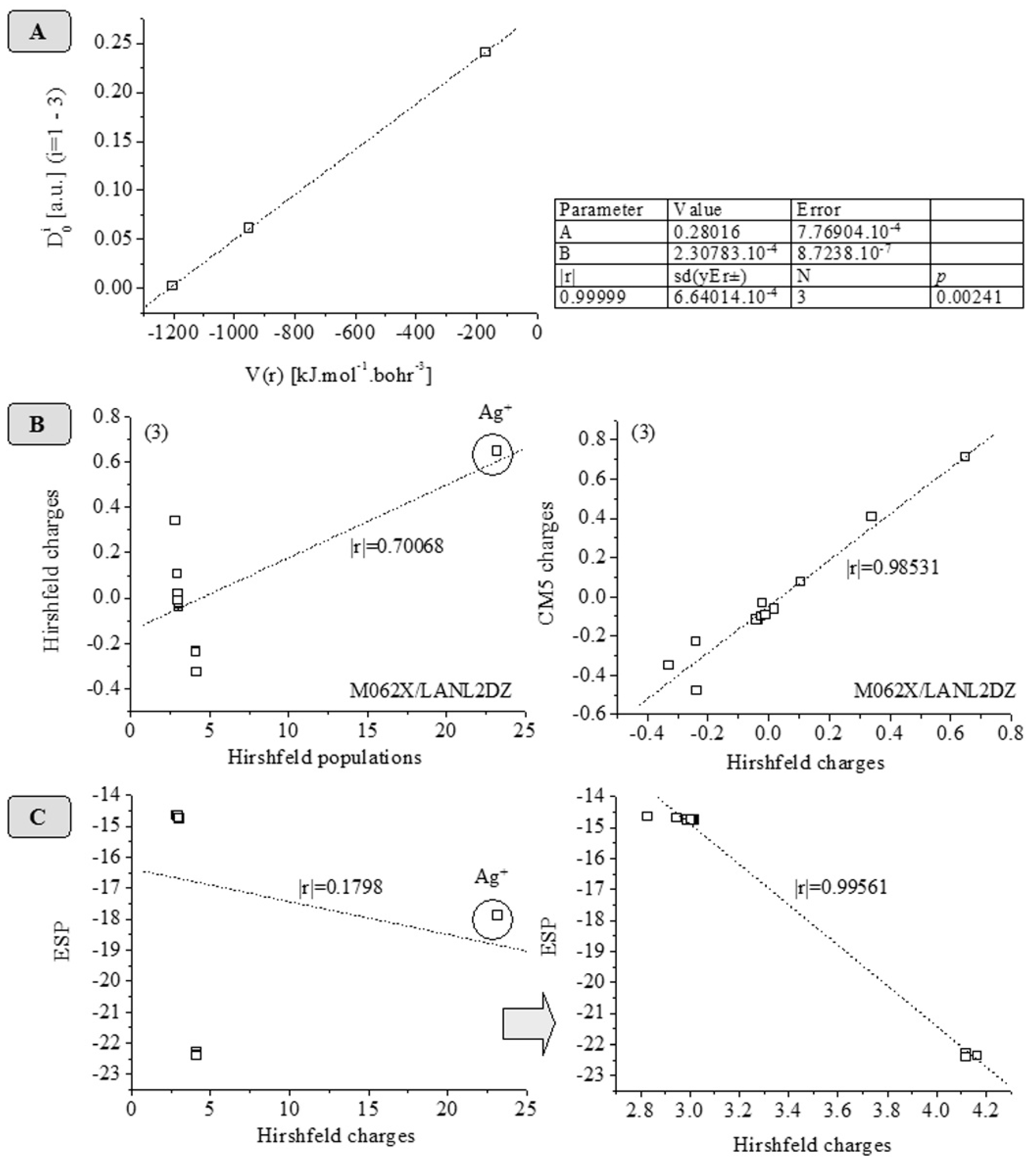

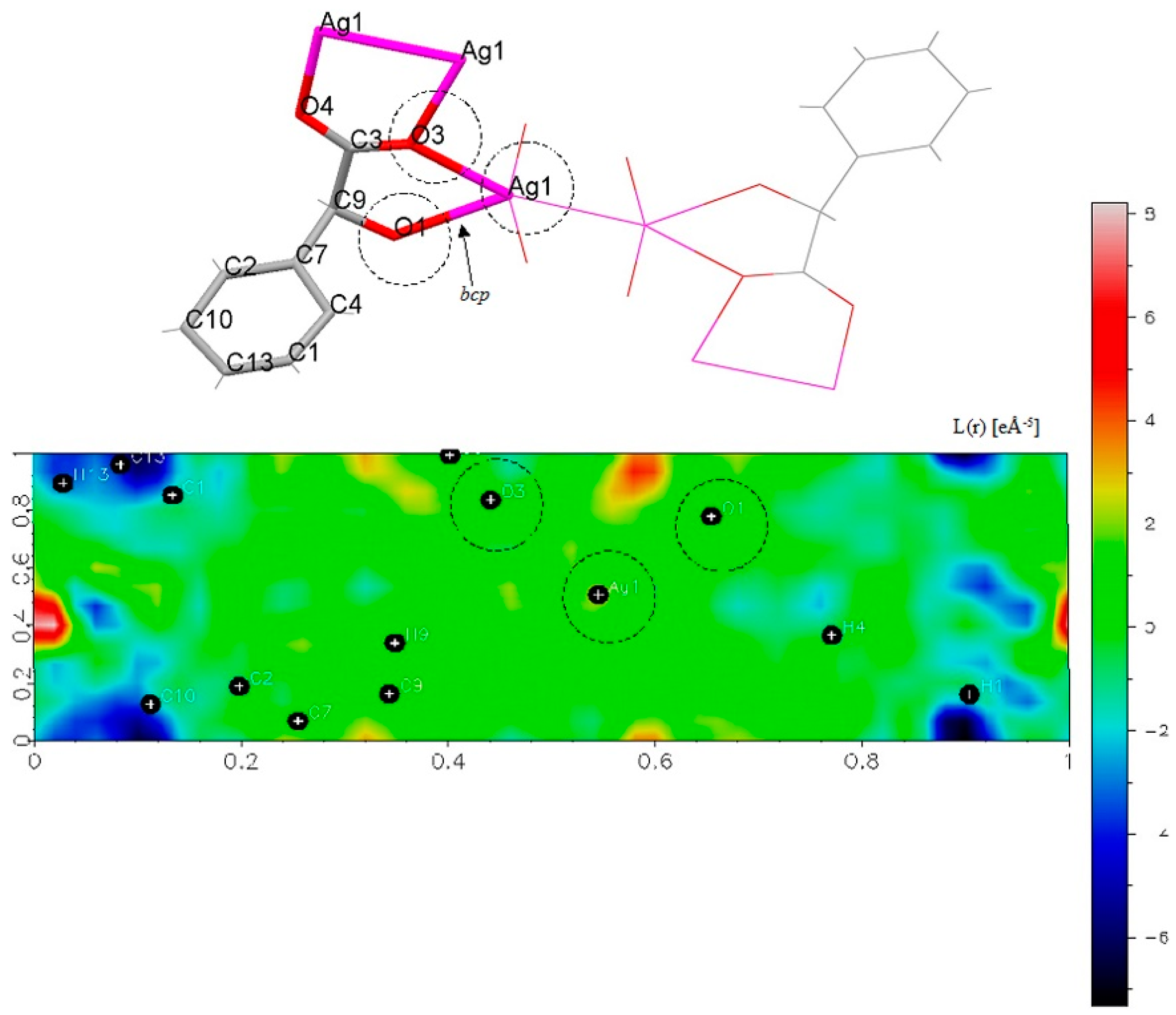

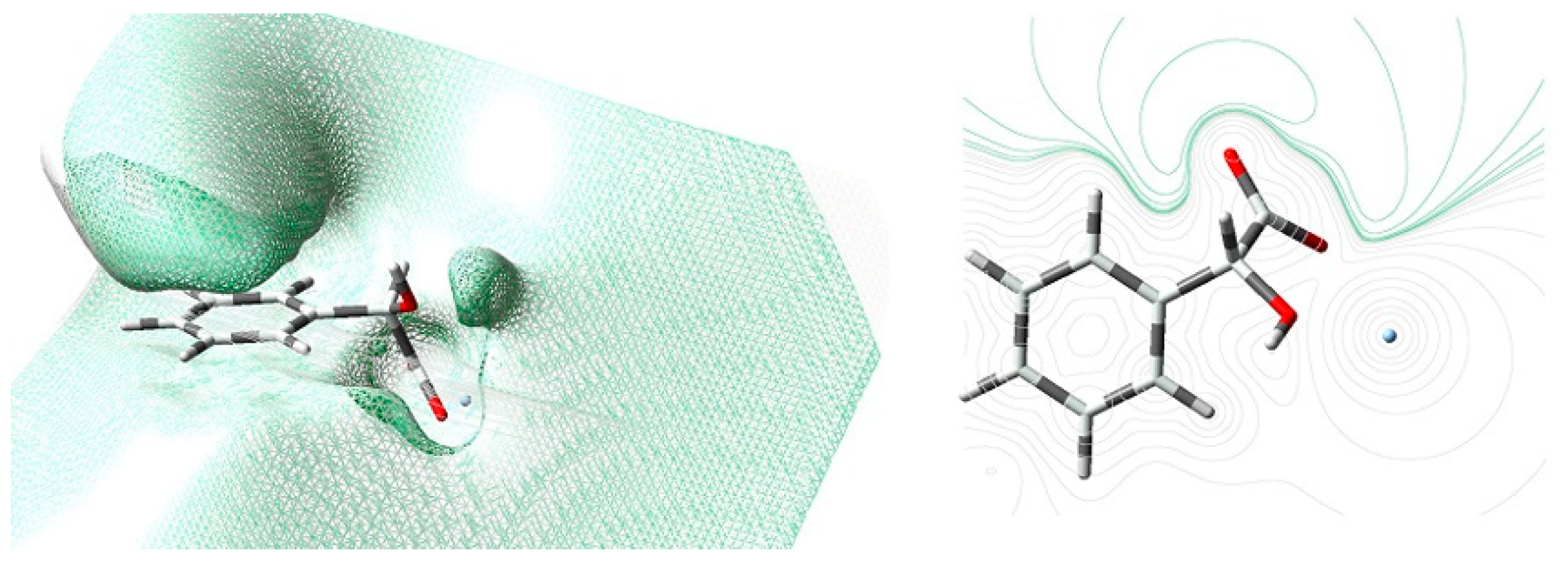

Crystals of mandelic acid are of significant importance. They are commercial pharmaceutics formulations modulating active ingredient solubility and its pharmacological effect. Commercial pharmaceuticals are at about 50 % crystals. Salt formulation is among the most used strategy for improving properties of medications. Salt crystallization screening is routinely implemented into pharmaceutical industry. Via disproportionation there is produced free therapeutics forms. The process is thermodynamically and kinetically driven. It is tackled by crystallographic and quantum chemical methods for salt screening as integral parts of development workflow in pharmaceutical industry. Correlations among crystallographic, Fourier-transform infrared, and electronic spectroscopic data on salts, and theoretical thermochemical approaches are of primary importance for determining relations among molecular structure « crystal structure « properties of crystals. This paper presents novel structural and molecular spectroscopic data on crystals of mandelic acid such as DL-mandelic acid (1), 4-phenyl-pyridinium mandelate mandelic acid (2) ¾ first, reported, herein, ¾ and catena-((μ3-DL-mandelato)-silver(I)) (3). It also utilizes chemometrics. The major conclusion follows from relation between crystallographic potential energy data on bond critical point using Abramov’s formula and theoretical bond dissociation energy showing |r|=0.9999. The approach seems best characterizes experimental crystallographic energetics of chemical bonds of molecules fitted off theoretical data.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Crystallographic Data

| D,L-MA (polymorph I) | D,L-MA (polymorph I) | D,L-MA (polymorph II) | 4-Phenyl-pyridine (bis)mandelate (bis)mandelic acid | catena-((μ3-DL-mandelato)-silver(I)) | |

| Compound | (1) | (2) | (3) | ||

| CCDC | 880481 | 923825 (P=0.05 GPa) |

923830 (P=0.76GPa) |

822753 | 771414 |

| Refs. | [57] | [59] | [59] | This work | [91] |

| Formula | C8H8O3 | C8H8O3 | C8H8O3 | C27H25NO6 | C8H6O3Ag |

| Mr | 152.14 | 152.14 | 152.14 | 459.48 | 258.00 |

| Crystal size | 0.48×0.25×0.16 | 0.44×0.41×0.32 | 0.42×0.32×0.14 | 0.47×0.23×0.14 | 0.53×0.19×0.10 |

| Crystal system | Orthorhombic | Orthorhombic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic | Monoclinic |

| Space group | Pbca | Pbca | P 21/c | P21/n | P21/c |

| T [K] | 198(2) | 296(2) | 296(2) | 200(2) | 300(2) |

| λ [Å] | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| a [Å] | 9.9537(15) | 9.676(2) | 5.825(2) | 17.080(3) | 16.274(3) |

| b [Å] | 9.6632(15) | 16.200(7) | 28.908(11) | 14.395(3) | 4.7421(9) |

| c [Å] | 16.173(3) | 9.8866(19) | 8.224(6) | 19.408(4) | 10.3421(19) |

| α [o] | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| β [o] | 90.00 | 90.00 | 93.03(4) | 96.648(7) | 95.093(5) |

| χ [o] | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| V [Å] | 1555.6(4) | 1549.74 | 1382.9 | 4739.6(16) | 795.0(2) |

| Z | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 4 |

| µ[mm-1] | 0.100 | 0.100 | 0.113 | 0.091 | 2.492 |

| ρcalc [mg.m-3] | 1.299 | 1.304 | 1.462 | 1.288 | 2.156 |

| 2θ [o] | 25.10 | 28.36 | 27.67 | 25.07 | 25.03 |

| Refl. collect. | 8941 | 5614 | 4768 | 5830 | 1401 |

| Unique refl. | 1386 | 535 | 684 | 614 | 1107 |

| Obs. refl. [I>2σ(I)] | 1386 | 386 | 598 | 614 | 1401 |

| GOF on F2 | 0.796 | 1.297 | 1.335 | 1.359 | 0.860 |

| R1 [I > 2σ(I)] | 0.0410 | 0.1421 | 0.2052 | 0.0632 | 0.0408 |

| ωR2 (all data) | 0.0580 | 0.2142 | 0.2242 | 0.1029 | 0.0670 |

| Residuals [e.Å-3] | 0.119/-0.171 | 0.110/-0.142 | 0.281/-0.265 | 0.446/-0.282 | 0.696/-1.417 |

| Atom_1 | Atom_2 | ρ(r) | ∇2ρ(r) | λi, i = 1–3 | Ellipticity (ε) | ||

| λ1 | λ2 | λ3 | |||||

| Ag1 | O1 | 0.2411 | 4.00 | -0.92 | -0.90 | 5.82 | 0.0170 |

| Ag1 | O3 | 0.2068 | 3.34 | -0.74 | -0.74 | 4.81 | 0.0067 |

| O1 | C9 | 1.4501 | 4.42 | -7.60 | -7.59 | 19.61 | 0.0012 |

| O3 | C3 | 1.8884 | -3.23 | -9.74 | -9.59 | 16.09 | 0.0154 |

| O4 | C3 | 2.0915 | 3.83 | -11.08 | -10.91 | 25.82 | 0.0154 |

| C1 | C4 | 1.4311 | -1.35 | -6.71 | -6.44 | 11.80 | 0.0412 |

| C1 | C13 | 1.7817 | -7.35 | -8.55 | -8.27 | 9.47 | 0.0346 |

| C2 | C7 | 1.4228 | -1.34 | -6.67 | -6.41 | 11.74 | 0.0402 |

| C2 | C10 | 1.5170 | -2.72 | -7.18 | -6.93 | 11.40 | 0.0359 |

| C3 | C9 | 1.2828 | 0.39 | -5.79 | -5.78 | 11.95 | 0.0024 |

| C4 | C7 | 1.4939 | -2.39 | -7.05 | -6.80 | 11.47 | 0.0368 |

| C7 | C9 | 1.3293 | -0.10 | -6.07 | -5.95 | 11.92 | 0.0198 |

| C10 | C13 | 1.3169 | 0.07 | -6.09 | -5.83 | 11.99 | 0.0448 |

| Atom_1 | Atom_2 | Gcp | Vcp | Gcp | Vcp |

| [a.u.Bohr-3] | [a.u.Bohr-3] | [kJ.mol-1.Bohr-3] | [kJ.mol-1.Bohr-3] | ||

| Ag1 | O1 | 0.03878 | -0.03608 | 101.82 | -94.73 |

| Ag1 | O3 | 0.03170 | -0.02878 | 83.22 | -75.55 |

| O1 | C9 | 0.25190 | -0.45797 | 661.35 | -1202.40 |

| O3 | C3 | 0.32141 | -0.67633 | 843.87 | -1775.71 |

| O4 | C3 | 0.43401 | -0.82829 | 1139.49 | -2174.68 |

| C1 | C4 | 0.20722 | -0.42842 | 544.05 | -1124.81 |

| C1 | C13 | 0.26115 | -0.59855 | 685.65 | -1571.50 |

| C2 | C7 | 0.20519 | -0.42428 | 538.72 | -1113.94 |

| C2 | C10 | 0.21980 | -0.46783 | 577.08 | -1228.30 |

| C3 | C9 | 0.18313 | -0.36224 | 480.80 | -951.06 |

| C4 | C7 | 0.21610 | -0.45694 | 567.36 | -1199.69 |

| C7 | C9 | 0.19078 | -0.38259 | 500.90 | -1004.48 |

| C10 | C13 | 0.18903 | -0.37729 | 496.30 | -990.57 |

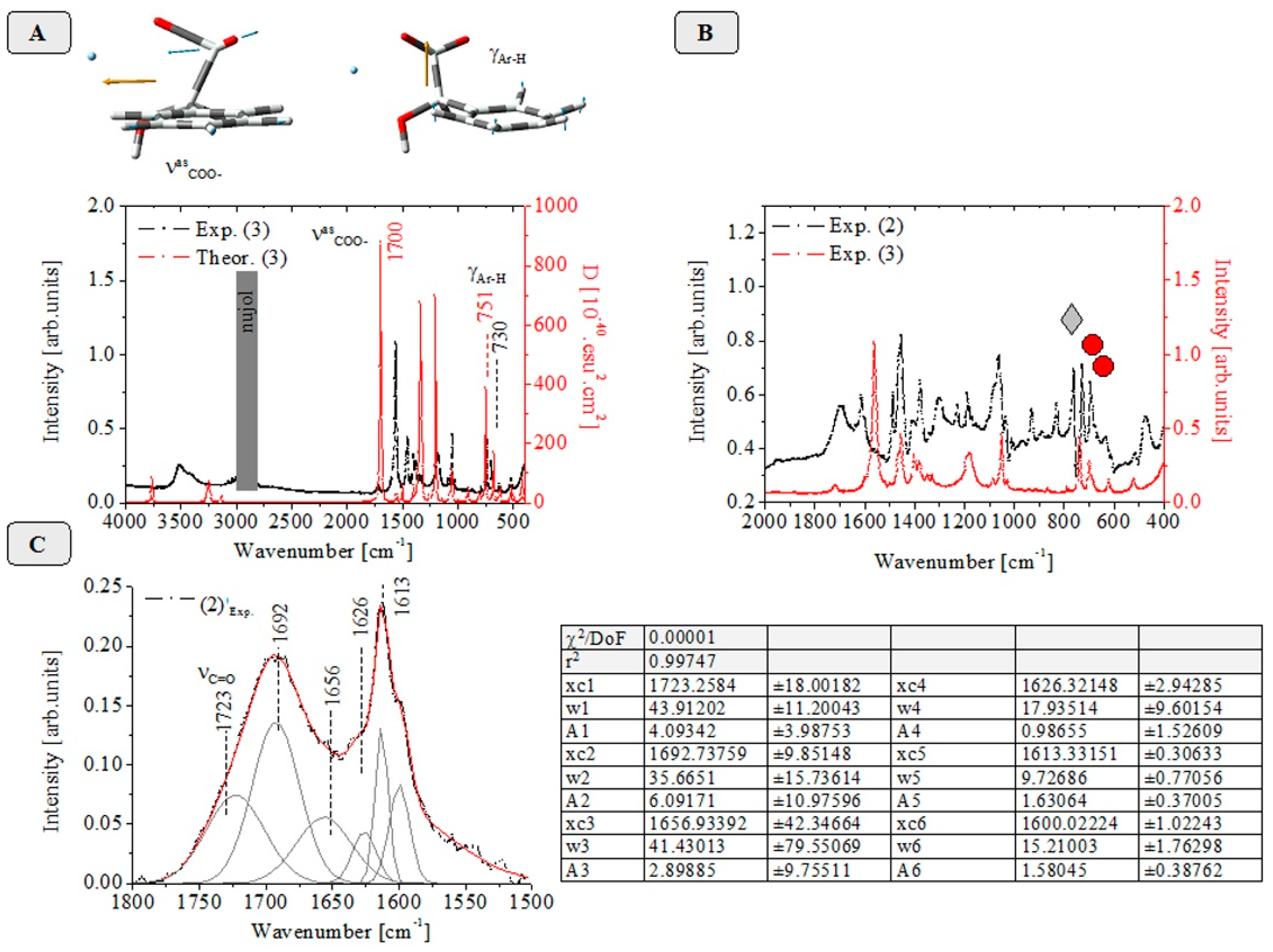

2.2. Vibrational Spectroscopic Data

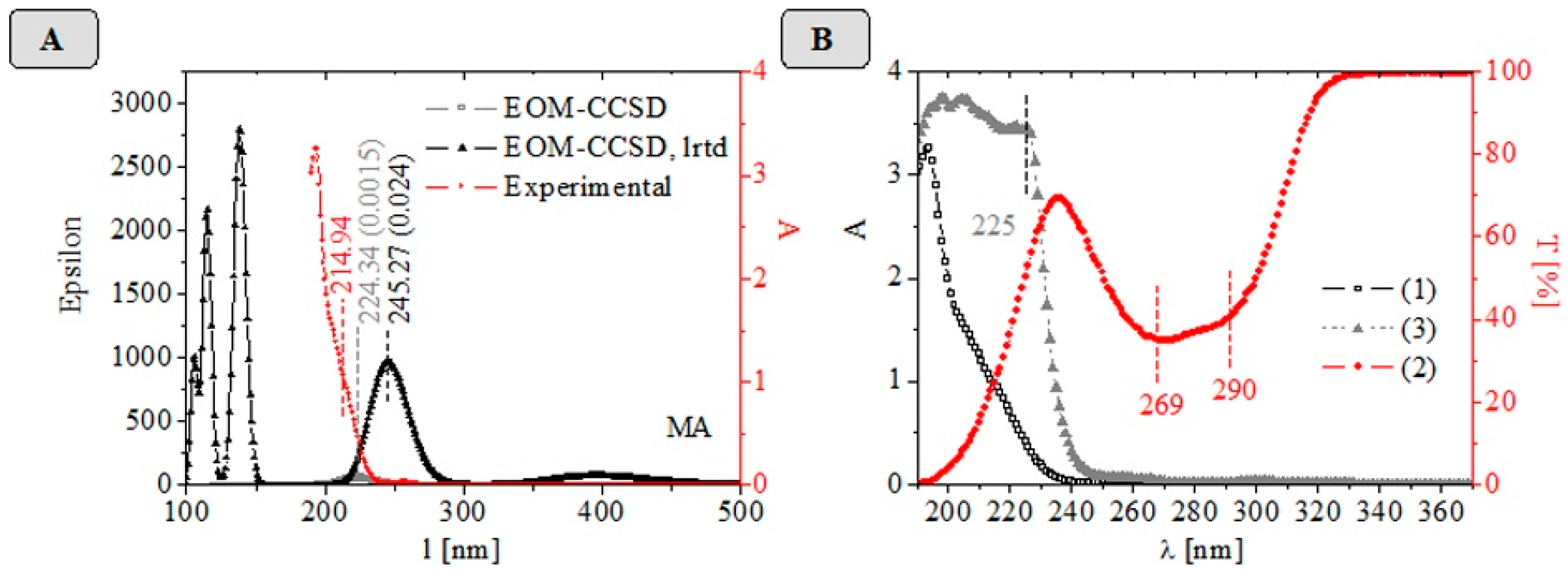

2.3. UV-VIS-NIR Data

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Euldji, I.; Si-Moussa; Hamadache, M.; Benkortbi, O. QSPR modelling of the solubility of drug and drug-like compounds in supercritical carbon dioxide. Mol. Inf. 2022, 41, 2200026.

- Kumari, N.; Ghosh, A. Cocrystallization: Cutting Edge Tool for Physicochemical Modulation of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 4858–4882. [CrossRef]

- Duggirala, N.K.; Perry, M.L.; Almarsson, Ö.; Zaworotko, M.J. Pharmaceutical cocrystals: along the path to improved medicines. Chem. Commun. 2015, 52, 640–655. [CrossRef]

- Almarsson, O.; Zaworotko, M. Crystal engineering of the composition of pharmaceutical phases. Do pharmaceutical co-crystals represent a new path to improved medicines? Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2004, (17), 1889-96.

- Shah, H.S.; Michelle, C.; Xie, T.; Chaturvedi, K.; Kuang, S.; Abramov, Y.A. Computational and Experimental Screening Approaches to Aripiprazole Salt Crystallization. Pharm. Res. 2023, 40, 2779–2789. [CrossRef]

- https://www.future-marketinsights.com/reports/oral-solid-dosage-pharmaceutical-formulation-market].

- Tan, Q., Hosseini, S., Thévenin, D. In Nagel, W., Kröner, D., Resch, M- (Eds.), Chapter: Simulations of crystal growth using lattice Boltzmann formulation, High Performance Computing in ccience and engineering ’22. Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2024, pp. 387-475.

- Tan, Q.; Hosseini, S.; Seidel-Morgenstern, A.; Thévenin, D.; Lorenz, H. Thermal effects connected to crystallization dynamics: A lattice Boltzmann study. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 2023, 171. [CrossRef]

- Nechipadappu, S.K.; Swain, D. New drug–drug and drug–nutraceutical salts of anti-emetic drug domperidone: structural and physicochemical aspects of new salts. CrystEngComm 2024, 26, 926–942. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wei, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, S.; Xu, Z.; Peng, Y. Novel ethylenediamine-β-cyclodextrin grafted membranes for the chiral separation of mandelic acid and its derivatives. Chirality 2024, 36, e23662. [CrossRef]

- Tenorio, J., Alves, D., Carvalho Jr. P. Diastereoisomeric double salts of carvedilol with (L)- and (D)-mandelic acids. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1325, 140909.

- de Meester, J.; Layrisse, P.; Marchivie, M.; Collard, L.; Wery, G.; Brandel, C.; Cartigny, Y.; Subra-Paternault, P.; Leyssens, T.; Harscoat-Schiavo, C. Towards a new approach in chiral resolution: Pressurized-CO2 assisted preferential cocrystallization. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2024, 212. [CrossRef]

- Martínková, L.; Křen, V. Biocatalytic production of mandelic acid and analogues: a review and comparison with chemical processes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 3893–3900. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.M.; Cosler, L.E.; Harausz, E.P.; Myers, C.E.; Kufel, W.D. Methenamine for urinary tract infection prophylaxis: A systematic review. Pharmacother. J. Hum. Pharmacol. Drug Ther. 2023, 44, 197–206. [CrossRef]

- Fitriani, L.; Fadina, H.; Usman, H.; Za, Z. Information and characterization of multicomponent crystal of triamethoprim and mandelic acid by solvent drop griding method. Int. J. Appl. Pharmaceut. 2023, 15, 75-79.

- Songsermsawad, S.; Nalaoh, P.; Promarak, V.; Flood, A. Chiral resolution of RS-baclofen via a novel chiral cocrystal of R-baclofen and L-mandelic acid. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 2441-2451.

- Trawally, M.; Demir-Yazıcı, K.; Dingiş-Birgül, S.İ.; Kaya, K.; Akdemir, A.; Güzel-Akdemir, Ö. Mandelic acid-based spirothiazolidinones targeting M. tuberculosis: Synthesis, in vitro and in silico investigations. Bioorganic Chem. 2022, 121, 105688. [CrossRef]

- Vimalson, D; Parimalakrishnan, S.; Jeganathan, N.; Anbazhagan, S. Techniques to enhance solubility of hydrophobic drugs: An overview. Asian J. Pharm. 2016, 10, S67-75.

- Chen, W.; Qiu, X.; Chen, Y.; Ke, J.; Ji, Y.; Chen, J. Supramolecular Interaction Modulation in Thermosensitive Composites: Enantiomeric Recognition and Chiral Site Regeneration. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 5580–5588. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Su, C.; Lei, J.; Chen, L.; Hu, H.; Zeng, S.; Yu, L. Studies on the L-2-hydroxy-acid oxidase 2 catalyzed metabolism of S-mandelic acid and its analogues. Drug Metab. Pharmacokinet. 2019, 34, 187–193. [CrossRef]

- Tay, H.M.; Hua, C. Chiral Coordination Polymers of Mandelate and its Derivatives: Tuning Crystal Packing by Modulation of Hydrogen Bonding. Aust. J. Chem. 2021, 75, 94–101. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Shemchuk, O.; Charpentier, M.D.; Matheys, C.; Collard, L.; ter Horst, J.H.; Leyssens, T. Simultaneous Chiral Resolution of Two Racemic Compounds by Preferential Cocrystallization**. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60, 20264–20268. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Peng, Y. Resolution of Halogenated Mandelic Acids through Enantiospecific Co-Crystallization with Levetiracetam. Molecules 2021, 26, 5536. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Body, C.; Robeyns, K.; Leyssens, T.; Shemchuk, O. On the pairwise cocrystallization of racemic compounds. CrystEngComm 2023, 25, 3060–3065. [CrossRef]

- Zahoor, M.; Shafiq, S.; Ullah, H.; Sadiq, A.; Ullah, F. Isolation of quercetin and mandelic acid from Aesculus indica fruit and their biological activities. BMC Biochemistry 2018, 19. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Li, Y.; Shi, H.; Yi, A.; Xu, X.; Wang, H.; Deng, X.; Wu, Z.; Cui, Z. Novel mandelic acid derivatives suppress virulence of Ralstonia solanacearum via type III secretion system. Pest Manag. Sci. 2023, 79, 4626–4634. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Ning, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Sun, B.; Jiang, W.; Yang, C.; Yang, S. Metabolic engineering of the L-phenylalanine pathway in Escherichia coli for the production of S- or R-mandelic acid. Microb. Cell Factories 2011, 10, 71–71. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Q.; Wang, X.; Shi, H.; Siddique, F.; Xian, J.; Song, A.; Wang, B.; Wu, Z.; Cui, Z.-N. Design and Synthesis of Mandelic Acid Derivatives for Suppression of Virulence via T3SS against Citrus Canker. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2024, 72, 9611–9620. [CrossRef]

- Sklyarenko, A.V.; Groshkova, I.A.; Gorbunov, N.A.; Vasiliev, A.V.; Kamaev, A.V.; Yarotsky, S.V. Comparative Evaluation of the Effectiveness of Biocatalytic Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity of Known Antibiotics and “Chimeric” Cephalosporin Compounds. Appl. Biochem. Microbiol. 2024, 60, 431–438. [CrossRef]

- Bhavsar, S.; Tadiparthi, R.; Gupta, S.; Pawar, S.; Yeole, R.; Kayastha, A.K.; Deshpande, P.; Bhagwat, S.; Patel, M. Design and development of efficient synthetic strategies for the chiral synthesis of novel ketolide antibiotic, nafithromycin (WCK 4873). Chem. Pap. 2023, 77, 3629–3640. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lv, Q.; Tu, G. Synthesis and Molecular Simulation Studies of Mandelic Acid Peptidomimetic Derivatives as Aminopeptidase N Inhibitors. Curr. Comput. Aided-Drug Des. 2021, 17, 619–626. [CrossRef]

- Aslani, S.; Armstrong, D. Fast, sensitive LC–MS resolution of α-hydroxy acid biomarkers via SPP-teicoplanin and an alternative UV detection approach. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 3007-3017.

- Widgerow, A.D.; Ziegler, M.; Garruto, J.A.; Ionescu, L.; Shafiq, F.; Meckfessel, M.; Lain, E.(.; Ablon, G.; Harper, J.; Chang, A.L.; et al. Novel Strategy for Strengthening Dermatoporotic Skin by Managing Cellular Senescence. J. Drugs Dermatol. 2024, 23, 748–756. [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.; Ye, Z.; Zhou, K.; Wang, F.; Lian, C.; Shang, Y.; Liu, H. An Investigation into the Transdermal Behavior of Active Ingredients by Combination of Experiments and Multiscale Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2024, 128, 6327–6337. [CrossRef]

- Kopple, J.D. Phenylalanine and Tyrosine Metabolism in Chronic Kidney Failure. J. Nutr. 2007, 137, 1586S–1590S. [CrossRef]

- Bocato, M.; Quero, R.; Weil,A.; Cesila, C.; Adeyemi, I.; Barbosa Jr. F. A new adsorptive 3D–printed sampling device for simultaneous determination of 63 urinary organic acids by LC–MS/MS. Anal. Chim. Acta 2024, 1288, 342185.

- Yevglevskis, M.; Bowskill, C.R.; Chan, C.C.Y.; Heng, J.H.-J.; Threadgill, M.D.; Woodman, T.J.; Lloyd, M.D. A study on the chiral inversion of mandelic acid in humans. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2014, 12, 6737–6744. [CrossRef]

- Poláková, M.; Krajčovičová, Z.; Meluš, V.; Štefkovičová, M.; Šulcová, M. Study of Urinary Concentrations of Mandelic Acid in Employees Exposed to Styrene. Central Eur. J. Public Heal. 2012, 20, 226–232. [CrossRef]

- McDougall, I.R. Thyroid Cancer in Clinical Practice; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, GX, Netherlands, 2007; ISBN: .

- Chemie, I.F.U.L.F.A.; Ivanova, B. Structural Analysis of Polylactic Acid in Composite Starch Biopolymers – A Stochastic Dynamics Mass Spectrometric Approach. Innov. Discov. 2024, 1. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B. Stochastic dynamics mass spectrometric and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic structural analyses of composite biodegradable plastics. Pollut. Study 2024, 5, 2741.

- Cheng, Y.; Jiao, Z.; Li, M.; Xia, M.; Zhou, Z.; Song, P.; Xu, Q.; Wei, Z. A new class of nucleating agents for poly(L-lactic acid): Environmentally-friendly metal salts with biomass-derived ligands and advanced nucleation ability. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 225, 1599–1606. [CrossRef]

- Liao, H.; Feng, B.; Song, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Z. Unlocking full potential of bamboo waster: Efficient co-production of xylooligosaccharides, lignin, and glucose through low-dosage mandelic acid hydrolysis with alkaline processing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137165. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, B.; Liang, J.; Wang, F.; Bao, Y.; Qin, C.; Liang, C.; Huang, C.; Yao, S. Rapid and mild fractionation of hemicellulose through recyclable mandelic acid pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 382, 129154. [CrossRef]

- Jeswani, H.K.; Perry, M.R.; Shaver, M.P.; Azapagic, A. Biodegradable and conventional plastic packaging: Comparison of life cycle environmental impacts of poly(mandelic acid) and polystyrene. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023, 903, 166311. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chin, A.L.; Tong, R. Controlled Ring-Opening Polymerization of O-Carboxyanhydrides to Synthesize Functionalized Poly(α-Hydroxy Acids). Org. Mater. 2021, 03, 041–050. [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Simmons, T.L.; Bohnsack, D.A.; Mackay, M.E.; Smith, M.R.; Baker, G.L. Synthesis of Polymandelide: A Degradable Polylactide Derivative with Polystyrene-like Properties. Macromolecules 2007, 40, 6040–6047. [CrossRef]

- Buchard, A.; Carbery, D.R.; Davidson, M.G.; Ivanova, P.K.; Jeffery, B.J.; Kociok-Köhn, G.I.; Lowe, J.P. Preparation of Stereoregular Isotactic Poly(mandelic acid) through Organocatalytic Ring-Opening Polymerization of a Cyclic O-Carboxyanhydride. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 13858–13861. [CrossRef]

- Halder, P.; Chakraborty, B.; Banerjee, P.R.; Zangrando, E.; Paine, T.K. Role of α-hydroxycarboxylic acids in the construction of supramolecular assemblies of nickel(ii) complexes with nitrogen donor coligands. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 2650–2659. [CrossRef]

- lvarez-Vidaurre, A.; Castiñeiras,A.; Frontera, A.; García-Santos, I.; Gil, D.; González-Pérez, Niclós-Gutiérrez, J.; Torres-Iglesias, R. Weak interactions in cocrystals of isoniazid with glycolic and mandelic acids. Crystals 2021, 11, 328.

- Mao, Z.; Xia, K.; Zhang, K.; Chen, H.; Li, M.; Abdukader, A.; Jin, W. Visible light-induced oxidative esterification of mandelic acid with alcohols: a new synthesis of α-ketoesters. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 6046–6050. [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M.; Varma, H.; Mishra, M.; Mukherjee, A. Template-sssisted visible light-induced [2+2] photodimerization in a pseudopolymorphic binary Solid: Topotacbc transformation vs photoinduced crystal melting. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 5193-5199.

- Patent: UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON - WO2020/43866, 2020, A1.

- van Haren, M.J.; Thomas, M.G.; Sartini, D.; Barlow, D.J.; Ramsden, D.B.; Emanuelli, M.; Klamt, F.; Martin, N.I.; Parsons, R.B. The kinetic analysis of the N -methylation of 4-phenylpyridine by nicotinamide N -methyltransferase: Evidence for a novel mechanism of substrate inhibition. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 98, 127–136. [CrossRef]

- Maris, M.; Ferri, D.; Königsmann, L.; Mallat, T.; Baiker, A. Why are α-hydroxycarboxylic acids poor chiral modifiers for Pt in the hydrogenation of ketones? J. Catal. 2006, 237, 230-236.

- Fu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, S. Mandelic acid as an interfacial modifier for high performance NiOx-based inverted perovskite solar cells. ChemNanoMat 2022, 8, e202200091.

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. Matrixes in UV-MALDI mass spectrometry – crystals of organic saltsversus co-crystals of neutral polyfunctional carboxylic acids. Anal. Methods 2012, 4, 2247-2253.

- Marciniak, J.; Andrzejewski, M.; Cai, W.; Katrusiak, A. Wallach’s Rule Enforced by Pressure in Mandelic Acid. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 4309–4313. [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Marciniak, J.; Andrzejewski, M.; Katrusiak, A. Pressure Effect on d,l-Mandelic Acid Racemate Crystallization. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 7279–7285. [CrossRef]

- Rose, H. Crystallographic Data. 61. dl-mandelic acid. Anal. Chem. 1952, 24, 1680-1681.

- Wei, K.T.; Ward, D.L. α-Hydroxyphenylacetic acid: a redetermination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1977, 33, 797–800. [CrossRef]

- Mughal, R.; Gillon, A.; Davey, R. DL-mandelic acid: CCDC 602882, 2006.

- Fischer, A.; Profir, V.M. A metastable modification of (RS)-mandelic acid. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Struct. Rep. Online 2003, 59, o1113–o1116. [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, I.B.; Barrio, M.; Tamarit, J.-L.; Do, B.; Céolin, R. Enantiomer Resolution by Pressure Increase: Inferences from Experimental and Topological Results for the Binary Enantiomer System (R)- and (S)-Mandelic Acid. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 14698–14703. [CrossRef]

- Ellison, R.D.; Johnson, C.K.; Levy, H.A. Glycolic acid: direct neutron diffraction determination of crystal structure and thermal motion analysis. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Crystallogr. Cryst. Chem. 1971, 27, 333–344. [CrossRef]

- Bond, A.; Boese, R.; Desiraju, G. What is a polymorph? Aspirin as a case study. Am. Pharmaceut. Rev. 2007, 2007, 1-4.

- Bond, A.D.; Solanko, K.A.; Parsons, S.; Redder, S.; Boese, R. Single crystals of aspirin form II: crystallisation and stability. CrystEngComm 2010, 13, 399–401. [CrossRef]

- Higashi, K.; Ueda, K.; Moribe, K. Recent progress of structural study of polymorphic pharmaceutical drugs. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2017, 117, 71–85. [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, C. Intralayer Molecular Packing Coefficient as One Packing Characteristic of Planar Layer-Stacked Crystals and Its Dominators. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 9849–9856. [CrossRef]

- Vasconcelos, S.; Tenorio, J.; Gurgel, J.; Benevides, C.; Nazario, C.; Carvalho Jr, P. Polymorphism of racemic (±)-Mefloquine free base: The role of enantiomeric recognition in polymorph assemblies. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1325, 141043.

- Rietveld, I.B.; Barrio, M.; Tamarit, J.-L.; Do, B.; Céolin, R. Enantiomer Resolution by Pressure Increase: Inferences from Experimental and Topological Results for the Binary Enantiomer System (R)- and (S)-Mandelic Acid. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 14698–14703. [CrossRef]

- Hylton, R.; Tizzard, G.; Threlfall, T.; Ellis, A.; Coles, S.; Seaton, C.; Schulze, E.; Lorenz, H.; Seidel-Morgenstern, A.; Stein, M.; Price, S. Are the crystal structures of enantiopure and racemic mandelic acids determined by kinetics or thermodynamics? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11095-11104.

- Ivanova, B. Special Issue with Research Topics on “Recent Analysis and Applications of Mass Spectra on Biochemistry”. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Nervall, M.; Hanspers, P.; Carlsson, J.; Boukharta, L.; Aqvist, J. Predicting binding modes from free energy calculations J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 2657-2667.

- Cheng, Y.; Prusoff, W. Relationship between the inhibition constant (KI) and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50 per cent inhibition (I50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973, 22, 3099-3108.

- Wang, Y.-T.; Su, Z.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-H.; Chen, C.-L. Predictions of Binding for Dopamine D2 Receptor Antagonists by the SIE Method. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009, 49, 2369–2375. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.; Craven, R. Molecular electrostatic potentials from crystal diffraction: The neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid. Biophys. J. 1993, 65, 998-1005.

- Hirshfeld, F. Difference densities by least-squares refinement: fumaric acid. Acta Cryst. 1971, B27, 769-781.

- Stewart, R.F. On the mapping of electrostatic properties from bragg diffraction data. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1979, 65, 335–342. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R. Mapping electrostatic potentials from diffraction data. God. Jugosl. Cent. Kristalogr. 1982, 17, 1-24.

- Spackman, M.A.; McKinnon, J.J.; Jayatilaka, D. Electrostatic potentials mapped on Hirshfeld surfaces provide direct insight into intermolecular interactions in crystals. CrystEngComm 2008, 10, 377–388. [CrossRef]

- Spackman, M. Jayatilaka, D. Hirshfeld surface analysis. CrystEngComm 2009, 11, 19-32.

- Bader, R. Atoms in Molecules - A Quantum Theory, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1990.

- Suda, S.; Tateno, A.; Nakane, D.; Akitsu, T. Hirshfeld Surface Analysis for Investigation of Intermolecular Interaction of Molecular Crystals. Int. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 13, 57–85. [CrossRef]

- Datt, I.; Ozerov, P. Presicion study of the electron density distributed in molecules and crystals from diffraction data. Zhurnal Strukt. Khim. 1975. 16, 509-535.

- Van Damme, S.; Bultinck, P.; Fias, S. Electrostatic Potentials from Self-Consistent Hirshfeld Atomic Charges. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, 5, 334–340. [CrossRef]

- Hirshfeld, F.L. Bonded-atom fragments for describing molecular charge densities. Theor. Chim. Acta 1977, 44, 129–138. [CrossRef]

- Hirshfeld, F.L.; Shmueli, U. Covariances of thermal parameters and their effect on rigid-body calculations. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1972, 28, 648–652. [CrossRef]

- Kuriyan, J.; Petsko, G.A.; Levy, R.M.; Karplus, M. Effect of anisotropy and anharmonicity on protein crystallographic refinement. J. Mol. Biol. 1986, 190, 227–254. [CrossRef]

- Cruickshank, D.W.J. The variation of vibration amplitudes with temperature in some molecular crystals. Acta Crystallogr. 1956, 9, 1005–1009. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. AgI and ZnII complexes with possible application as NLO materials – Crystal structures and properties. Polyhedron 2011, 30, 241–245. [CrossRef]

- Coppens, P.; Csonka, L.; Willoughby, T.V. Electron Population Parameters from Least-Squares Refinement of X-ray Diffraction Data. Science 1970, 167, 1126–1128. [CrossRef]

- Mangaiyarkkarasi, J.; Saravanan, R.; Ismail, M.M. Chemical bonding and charge density distribution analysis of undoped and lanthanum doped barium titanate ceramics. J. Chem. Sci. 2016, 128, 1913–1921. [CrossRef]

- Aubert, E.; Lebègue, S.; Marsman, M.; Bui, T.T.T.; Jelsch, C.; Dahaoui, S.; Espinosa, E.; Ángyán, J.G. Periodic Projector Augmented Wave Density Functional Calculations on the Hexachlorobenzene Crystal and Comparison with the Experimental Multipolar Charge Density Model. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 14484–14494. [CrossRef]

- Hirano, Y.; Takeda, K.; Miki, K. Charge-density analysis of an iron–sulfur protein at an ultra-high resolution of 0.48 Å. Nature 2016, 534, 281-284.

- Thomas, S.; Pavan, M.; Row, T.; Experimental evidence for ‘carbon bonding’ in the solid state from charge density analysis. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 49-51.

- Weinhold, F.; Landis, C.R. Discovering Chemistry with Natural Bond Orbitals; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, United States, 2012; ISBN: .

- Brown, I. The chemical bond in inorganic chemistry, The bond valence model, Oxford science publications, 2002, Oxford.

- Brown, I.D. Recent Developments in the Methods and Applications of the Bond Valence Model. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 6858–6919. [CrossRef]

- http://shelx.uni-ac.gwdg.de/SHELX/bv-method.pdf; http://shelx.uni-ac.gwdg.de/SHELX/complex_eden.pdf].

- Escudero, E.; Bauz, A.; Frontera, A.; Ballester, P. Nature of noncovalent carbon-bonding interactions derived from experimental charge-density analysis. ChemPhysChem 2015, 16, 2530-2533.

- Blanksby, S.J.; Ellison, G.B. Bond Dissociation Energies of Organic Molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 255–263. [CrossRef]

- Stalke, D. (Ed.), Electron density and chemical bonding I, Springer’s series ‘Structure and Bonding’, Springer Verlag, berlin Heidelberg, 2012, 1-212.

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. On the nature of the coordination bonding of metal–organics for ions with the d 10 electronic configuration – Experimental and theoretical analyses. Polyhedron 2017, 137, 256–264. [CrossRef]

- Abramov, Y. On the possibility of kinetic energy density evaluation from the experimental electron-density distribution Acta. Cryst. 1997, A53, 264-272.

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. Crystallographic and theoretical study of the atypical distorted octahedral geometry of the metal chromophore of zinc(II) bis((1R,2R)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane) dinitrate. 2021, 1248, 131488. [CrossRef]

- Marenich, A.V.; Jerome, S.V.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Charge Model 5: An Extension of Hirshfeld Population Analysis for the Accurate Description of Molecular Interactions in Gaseous and Condensed Phases. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 527–541. [CrossRef]

- Badawi, H.M.; Förner, W.; Ali, S.A. A study of the solvent dependence of the structures and the vibrational, 1H and 13C NMR spectra of l- and dl-mandelic acid and l- and dl-3-phenyllactic acid. J. Mol. Struct. 2015, 1093, 150–161. [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.C.; Guimarães, F.F.; Ribeiro, L.; Martins, F.T. Salt or cocrystal of salt? Probing the nature of multicomponent crystal forms with infrared spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2016, 167, 89–95. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Duan, S.; Zhang, R.; Ma, L.; Lin, K. Rapid chiral purity identification of mandelic acid by Raman spectra in the O–H stretching region. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 303, 123251. [CrossRef]

- Barth, G.; Voelter, W.; Mosher, H.; Bunnenberg, E.; Djerassi, C. Optical rotatory dispersion studies. CXVII.1 Absolute configurational assignments of some α-substituted phenylacetic acids by circular dichroism measurements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 875-886.

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. Stochastic dynamic electrospray ionization mass spectrometric diffusion parameters and 3D structural determination of complexes of AgI-ion – Experimental and theoretical treatment. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 292, 111307.

- Blessing, R.H. An empirical correction for absorption anisotropy. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 1995, 51, 33–38. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2008, A64, 112–122. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G. Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E: combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Crystal. 2010, D66, 479-485.

- Sheldrick, G.M. Phase annealing in SHELX-90: direct methods for larger structures. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Crystallogr. 1990, 46, 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Spek, A.L. Single-crystal structure validation with the programPLATON. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003, 36, 7–13. [CrossRef]

- http://www.ccp14.ac.uk/ccp/web-mirrors/mallinson/~paul/xd.html].

- Momma, K.; Ikeda, T.; Belik, A.A.; Izumi, F. Dysnomia, a computer program for maximum-entropy method (MEM) analysis and its performance in the MEM-based pattern fitting. Powder Diffr. 2013, 28, 184–193. [CrossRef]

- Le Page, Y. Computer derivation of the symmetry elements implied in a structure description. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1987, 20, 264–269. [CrossRef]

- Le Page, Y. MISSYM 1.1 - a flexible new release. J. Appl. Cryst. 1988, 21, 983-984.

- Spek, A.L. checkCIF validation ALERTS: what they mean and how to respond. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Crystallogr. Commun. 2020, 76, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Linden, A. Obtaining the best results: aspects of data collection, model finalization and interpretation of results in small-molecule crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Crystallogr. Commun. 2020, 76, 765–775. [CrossRef]

- http://www.crystallography.fr/crm2/fr/services/logiciels/MoPro.htm].

- http://www.chem.gla.ac.uk/~louis/software/wingx/].

- Dunitz, J.D.; Schomaker, V.; Trueblood, K.N. Interpretation of atomic displacement parameters from diffraction studies of crystals. J. Phys. Chem. 1988, 92, 856–867. [CrossRef]

- Dunitz, J.D.; Maverick, E.F.; Trueblood, K.N. Atomic Motions in Molecular Crystals from Diffraction Measurements. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1988, 27, 880–895. [CrossRef]

- Huebschle, C.; Sheldrick, G.; Dittrich, D. ShelXle: a Qt graphical user interface for SHELXL. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2011, 44, 1281-1284.

- Ivanova, B. (2025). Supporting information data. Zenodo. (available at 05.01.2025). [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.; Trucks, G.; Schlegel, H.; Scuseria, G.; Robb, M.; Cheeseman, J.; Fox, D. (1998, 2009), Gaussian 09, 98, Gaussian, Inc., Pittsburgh, Wallingford CT.[www.gaussian.com].

- Helgaker, T.; Jensen, H.; Jrgensen, P. et al. Dalton Program Package; 2011; [http://www.daltonprogram.org/download.html].

- Gordon, M.; Schmidt, M. Advances in electronic structure theory: GAMESS a decade later, in "Theory and Applications of Computational Chemistry: the first forty years" C. Dykstra, G. Frenking, K. Kim, G. Scuseria (Eds.,) Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2005; 1167-1189.

- Nielsen, A.; Holder, A. Gauss View 5.0, User’s Reference. GAUSSIAN Inc., Pittsburgh GausView03 Program Package, 2009; [www.gaussian.com/g_prod/gv5.htm].

- Burkert, U.; Allinger, N. Molecular mechanics in ACS Monograph 177, American Chemical Society, Washington D.C. 1982; pp. 1-339.

- Allinger, L. Conformational analysis. 130. MM2. A hydrocarbon force field utilizing V1 and V2 torsional terms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 8127-8134.

- Macetti, G.; Genoni, A. Quantum mechanics/extremely localized molecular orbital modelling strategy for excited states: Coupling to time-dependent density functional theory and equation-of-motion coupled cluster. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2020, 16, 7490-7506.

- Stanton, J.F.; Bartlett, R.J. The equation of motion coupled-cluster method. A systematic biorthogonal approach to molecular excitation energies, transition probabilities, and excited state properties. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 7029–7039. [CrossRef]

- Krylov, A.I. Equation-of-Motion Coupled-Cluster Methods for Open-Shell and Electronically Excited Species: The Hitchhiker's Guide to Fock Space. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2008, 59, 433–462. [CrossRef]

- Reshetova, E.N. Effect of the ionic strength of a mobile phase on the chromatographic retention and thermodynamic characteristics of the adsorption of enantiomers of α-phenylcarboxylic acids on a chiral adsorbent with grafted antibiotic eremomycin. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 91, 167–174. [CrossRef]

- OpenOffice [http://de.openoffice.org].

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).