1. Introduction

Paraproteinemic maculopathy (PM) is characterized by serous retinal detachment (SRD) of macula, and often develops as a result of an increase in a monoclonal antibody in the blood, associated with immunoproliferative diseases [

1]. SRD in PM can mimic central serous chorioretinopathy, polypoidal choroidal vasculopathy, age related macular degeneration, Harada’s disease, retinal macroaneurysm and retinal vein occlusion [

2]. Hyperviscosity retinopathy may also be observed in affected eyes of the paraproteinemic patients. In diabetics, this condition may lead to the misdiagnosis of diabetic retinopathy (DR) and diabetic macular edema (DME) particularly characterized by SRD based on optical coherence tomography (OCT) classification, resulting in unnecessary intravitreal treatments [

3,

4]. In this study, two diabetic patients with maculopathy had no answer to intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) treatment and diagnosed as PM are reported.

2. Case Presentations

2.1. Case 1

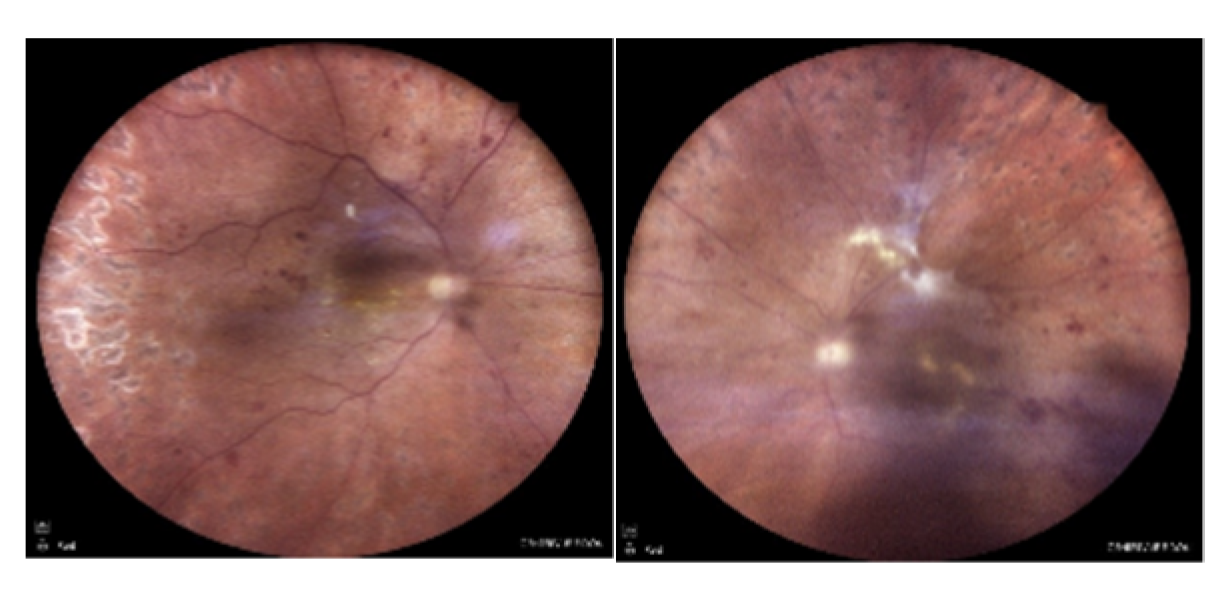

A 52-year-old diabetic male patient applied to a clinic with complaints of visual impairment in both eyes and was referred to our department with the diagnoses of DR and DME. He has been followed up with a diagnosis of diabetes for 12 years and has no other known systemic disease. In the ophthalmological examination, the best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/50 on the right eye and 20/30 on the left one with Snellen charts, bilateral anterior segments were normal, and intraocular pressure (IOP) measurements were within normal limits in both eyes (11/11 mHg). In dilated fundus examination, widespread dot-blot and flame-shaped hemorrhages and microaneurysms were seen in all quadrants of both retinas, consistent with DR and retinal laser spots were present (

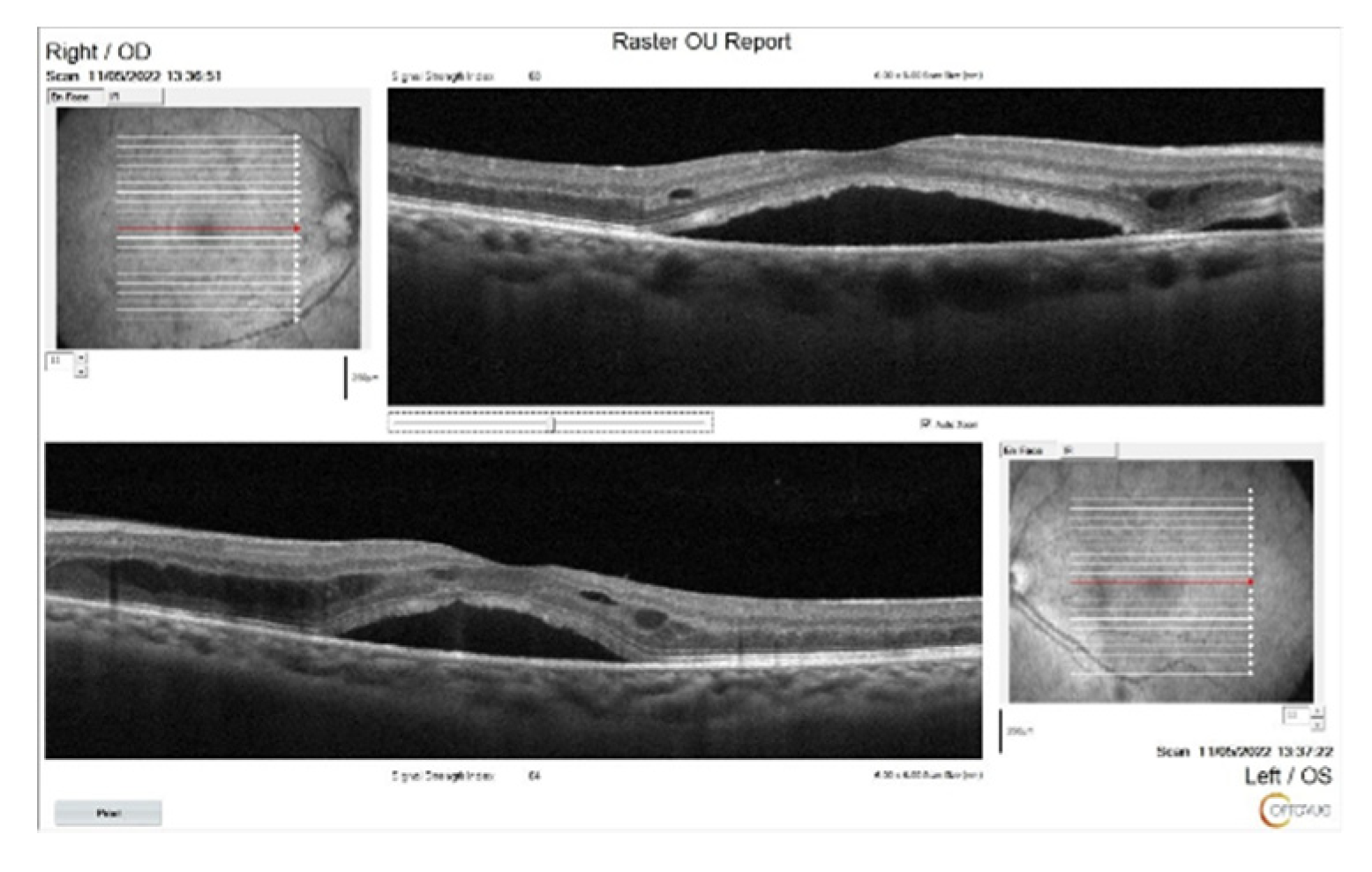

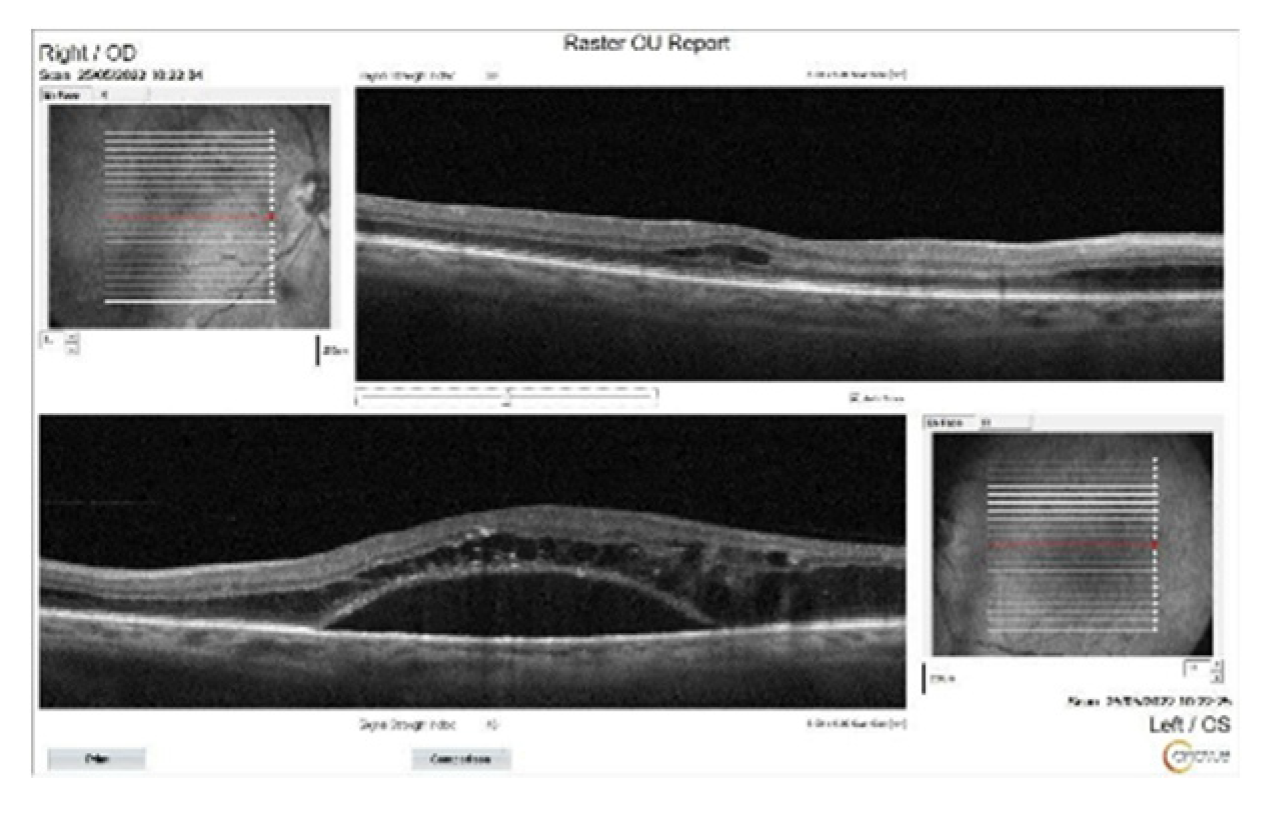

Figure 1). Bilateral SRD and intraretinal fluid accumulation, more prominent on the left eye, were detected on OCT (

Figure 2). The patient was diagnosed with DR and DME, intravitreal bevacizumab injection was recommended.

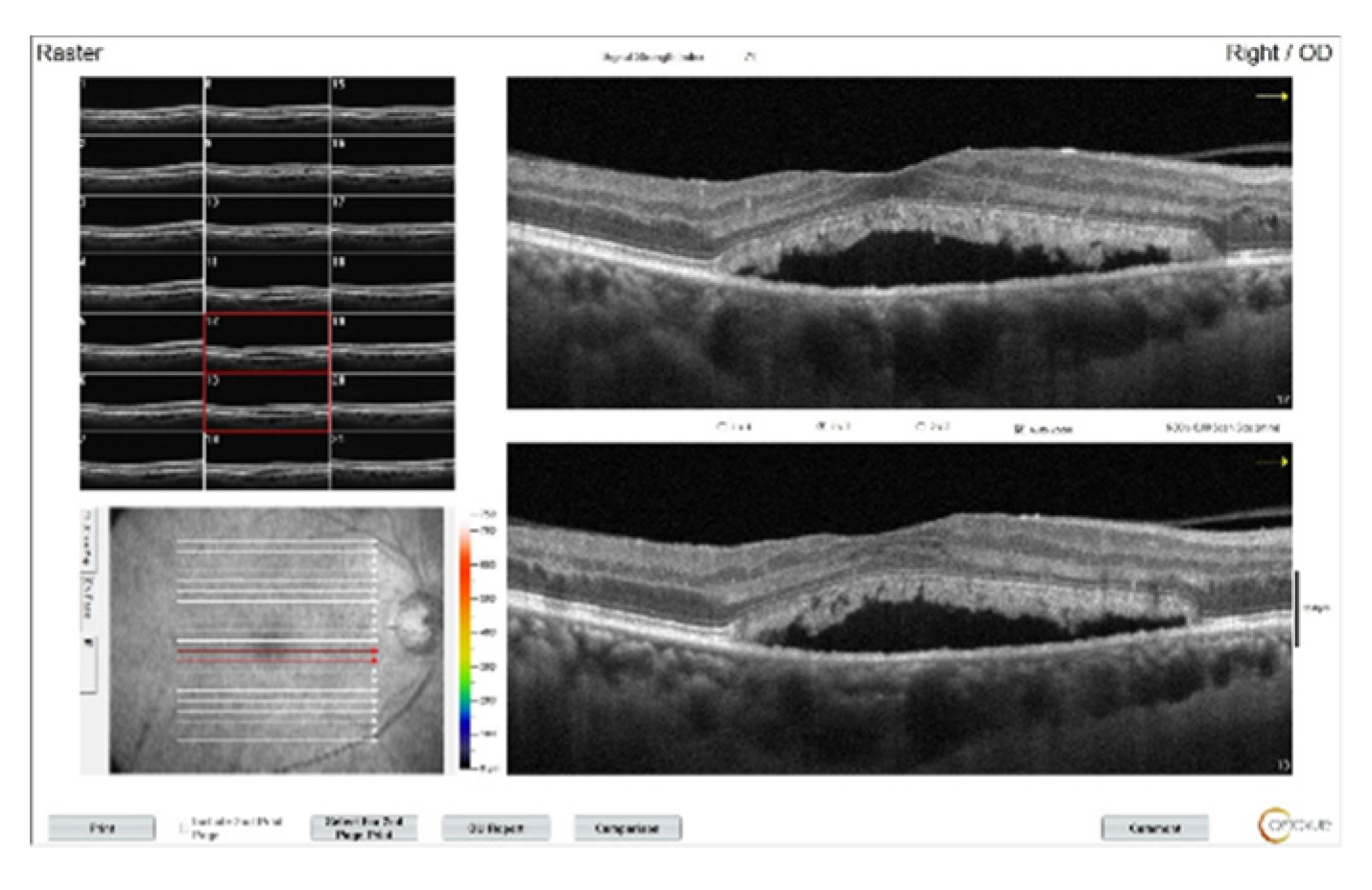

In his examination after 3 intravitreal bevacizumab injections to both eyes, BCVA decreased to 20/100 in the right eye and to 20/60 in the left eye, and OCT images showed a decrease in intraretinal fluid, but there was no regression in SRDs (

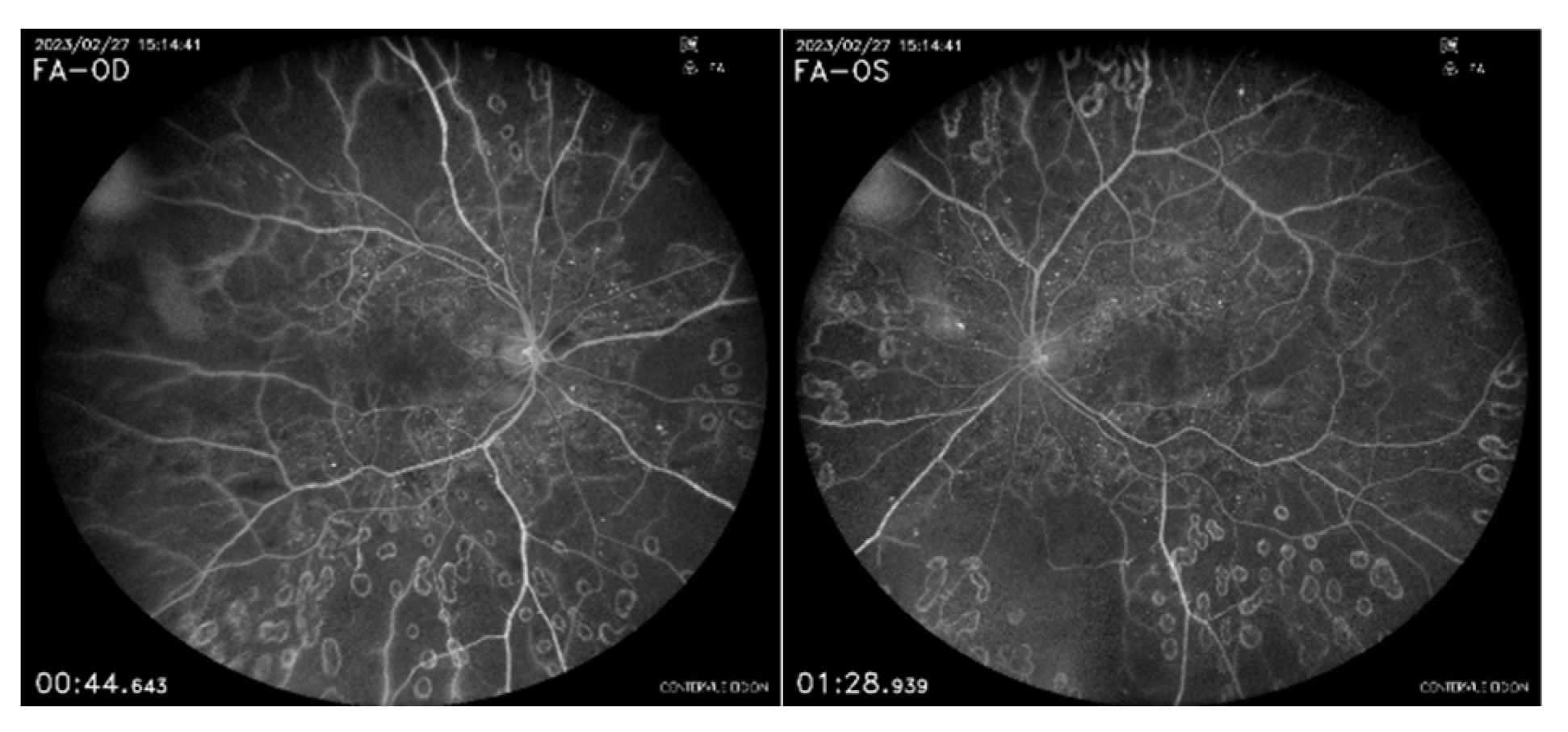

Figure 3). Continuining panretinal photocoagulation was scheduled due to the capillary ischemia in the fundus fluorecein angiography (FFA) (

Figure 4). However, since there was no apparent leakage in the macula on FFA, increased subretinal deposits were noted on OCT (

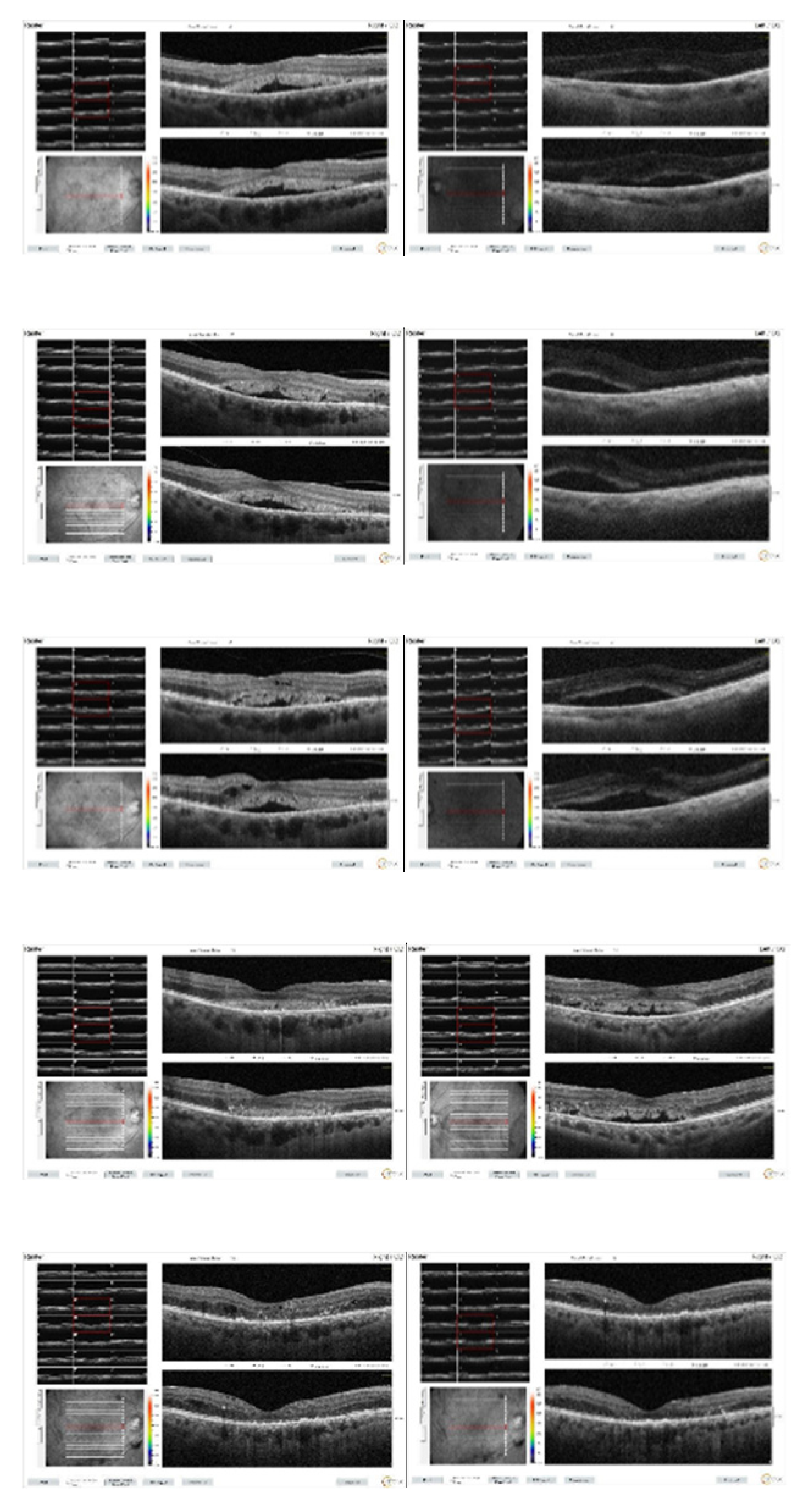

Figure 3), and the patient’s complaints of weakness and fatigue, an internal medicine consultation was requested. Laboratory tests showed hemoglobulin 6.8 g/dl (normal range:13.1-17.2 g/dl), albumin 23 g/l (normal range:35-52 g/dl), erythrocyte sedimentation rate 140 mm/h (normal value:< 15 mm/h), C-reactive protein 14.9 mg/l (normal value:<6 mg/l) and hemoglobin A1c 8.1% (normal range:3.5- 5.7 %) in the blood, and there was +3 proteinuria in the urine. Lymphadenopathy was detected in the left inguinal region. Abdominal computerized tomography was interpreted by radiologist as “Lytic bone lesions in the left iliac wing and right acetebulum, partial involvement in the L3 vertebra and near-total involvement in the L4 vertebra. Metastasis? Multiple myeloma?”. The patient was diagnosed with multiple myeloma (MM) with protein electrophoresis and hematologic examination. The patient was subsequently started on systemic chemotherapy for MM and no additional injections were administered for macular edema. With the beginning of treatment, the macular subretinal fluid gradually decreased and disappeared bilaterally. At the 1st year follow-up, BCVA was 20/80 on the right eye and 20/100 on the left. OCT images of the patient during follow-up can be seen in

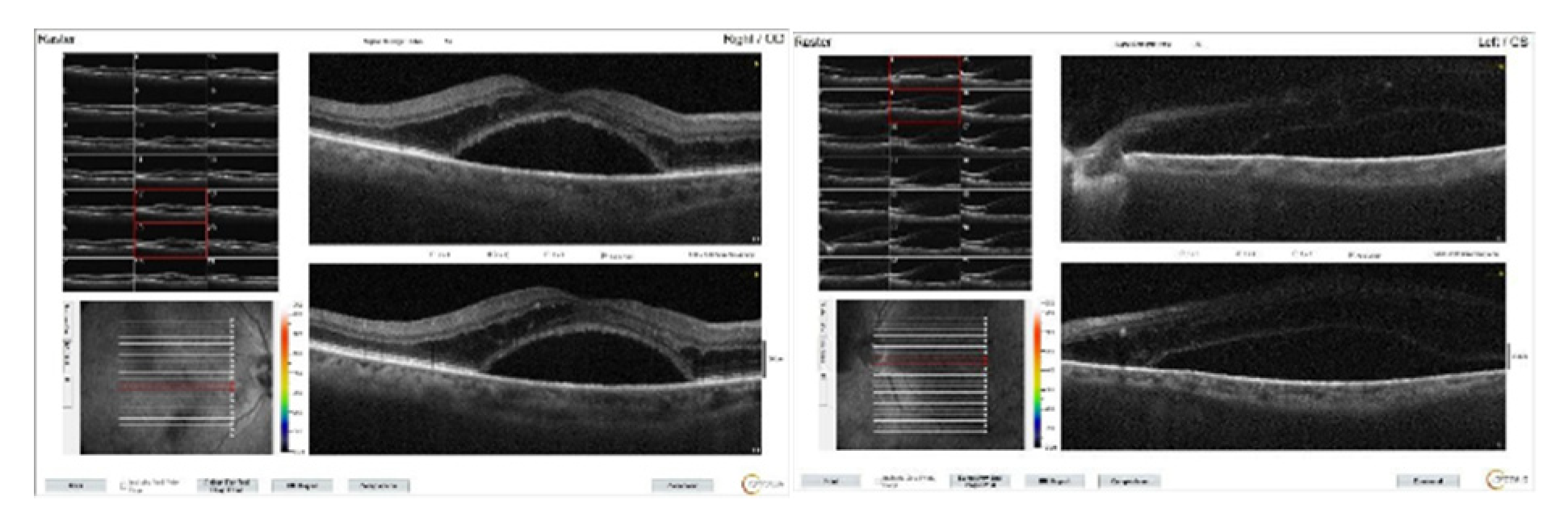

Figure 5.

2.2. Case 2

A 68-year-old male patient was admitted with a complaint of vision loss in his left eye. The patient had been using oral antidiabetic agents for 8 years due to diabetes and had no other known systemic disease. On ophthalmologic examination, BCVA was 20/25 on the right eye with Snellen charts and counting fingers at 50 cm on the left, the right eye was pseudophakic and there was a mature cataract on the left. On dilated fundus examination, there were retinal hemorrhages and cystoid macular edema on the right eye consistent with DR and DME, and the left fundus was very flu due to cataract, but ultrasonographically the retina was attached and the vitreous was normal. Left phacoemulsification surgery was initially recommended to the patient.

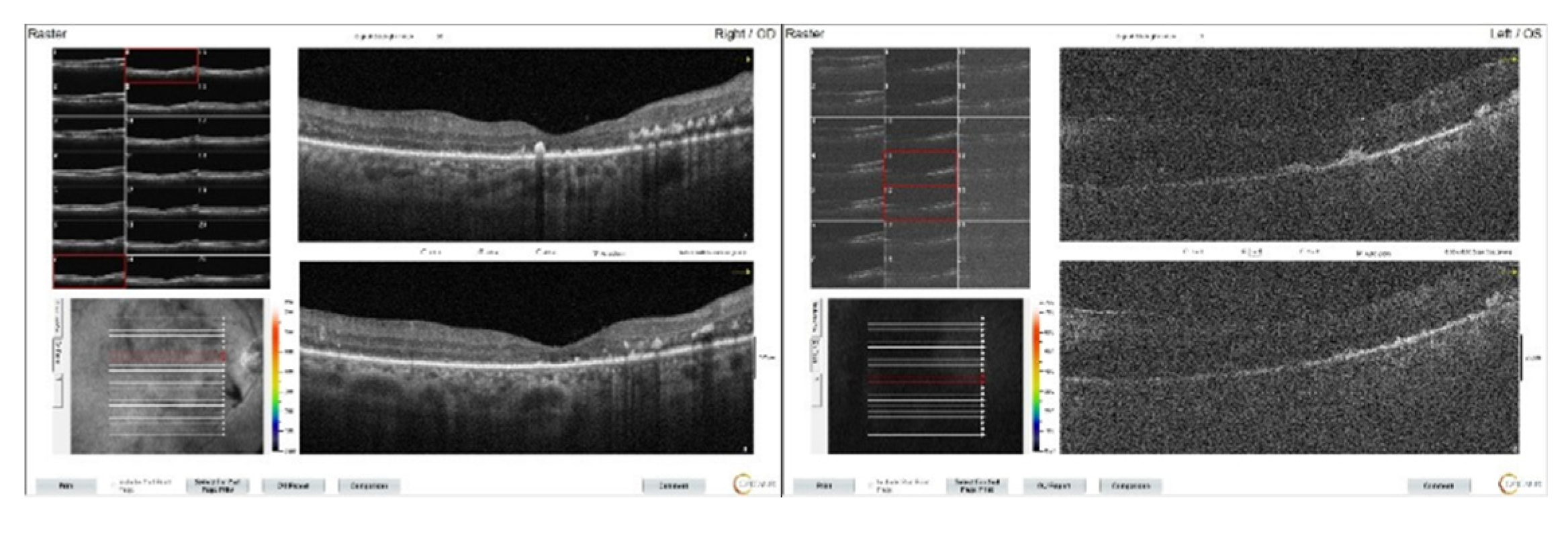

At the patient's first week follow-up after phacoemusification surgery, BCVA of the left eye did not increase and intraretinal fluid and subretinal dense serous fluid accumulation were detected on macular OCT (

Figure 6). At that time, the patient's hemoglobulinA1c was 12.1 % (normal range: 3.5-6.7 %), and hemoglobin level was 13.6 g/dl (normal range:12.6- 17.4 g/dl) and due to DME, the patient is given bilateral monthly bevacizumab injections of 3 doses with a recommendation for diabetes regulation. However, it was observed that the patient’s macular edema does not regress, on the contrary, it increased (

Figure 7). Subsequently, the patient was unable to attend the follow-ups for approximately one year. Upon returning one year later, ophthalmological examination revealed a BCVA of 20/200 in the right eye and finger counting at 2 meters in the left one. Bilateral pseudophakia with mild posterior subcapsular opacification in the left and no signs of rubeosis iridis was observed on biomicroscopy. IOPs in both eyes were within normal limits (16/16 mmHg). Fundus examination of the right eye revealed extensive retinal hemorrhages, hard exudates, microaneurysms, with subretinal and intraretinal edema in the macula. The left eye could not be visualized, and its ultrasonography was consistent with intravitreal hemorrhage. Upon inquiring about the systemic condition of the patient, it was learned that approximately one month ago, he was diagnosed with MM and chemotherapy had started. The patient was advised to remain in a sitting position and continuation of the systemic treatment was recommended. At that time, the patients hemoglobin level was 11.7 g/dL (normal range:13.2 - 16.6 g/dL), and hemoglobin A1c was 6.7% (normal range:3.5 - 5.7%).

Partial clearance of the vitreous hemorrhage was observed two months later. Due to the presence of extensive capillary ischemic areas on the FFA (

Figure 8), panretinal laser treatment was initiated. The patient’s BCVA was 20/200 in the right eye and finger counting at 1 meter in the left eye. OCT showed that macular edema had regressed in the right, but exudates were still prominent, and the ellipsoid zone was disrupted. The left eye was difficult to visualize, but the edema had regressed (

Figure 9). Approximately 8 months after the initiation of systemic treatment, the hemorrhages in the right eye had partially regressed with panretinal laser. The vitreous hemorrhage in the left eye had significantly regressed (

Figure 10).

3. Discussion

Multiple myeloma is one of the severe monoclonal gammopathies with broad-spectrum, known as plasma cell dyscrasias or plasma cell proliferative disorders, caused by pre-malignant or malignant plasma cells that excessively secrete an abnormal monoclonal antibody (or part of an antibody) [

5]. It begins with proliferation of plasma cells in the bone marrow and gradually leads to end-organ damage [

6]. MM accounts for 1% of all cancers and ranks second among hematological malignancies, with a rate of 10-17%, following lymphoma [

7,

8,

9]. In recent years, the clinical significance of MM has increased due to its rise in incidence [

7]. Despite the development of treatment approaches over the years and the improvement in 5-year survival rates, MM remains incurable [

6]. Although fatigue and bone pain are the most common symptoms of the patients, ocular findings have also been reported in the early stages of the disease [

4,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. Ocular involvement can develop through the direct deposition of immunoglobulin light chains in tissues (cornea, conjunctiva, ciliary pigment epithelium, ciliary body, and subretinal pigment epithelium), retinal manifestations of hyperviscosity syndrome, compression by extramedullary plasmacytomas, metastatic infiltration, or paraneoplastic retinal degeneration [

19].

Signs of hyperviscosity retinopathy includes retinal vein engorgement, vessel tortuosity, scattered hemorrhages, microaneurysms, optic disc edema, and venous beading [

20] and may mimic DR. Both patient in this report were diabetic, and no significant increase in venous tortuosity or engorgement was observed in their retinal vessels, with microaneurysms and retinal hemorrhages being more prominent. The presence of intraretinal cysts accompanying the subretinal fluid initially led us the diagnosis of DME. However, the absence of significant macular leakage on FFA and the apprearance of 'silent macula', along with the insufficient response to intravitreal anti-VEGF treatment, raised suspicions of other possible maculopathies. Similarly, Jayadev and colleagues previously reported a case of a diabetic patient who had refractory macular edema despite multiple intravitreal anti-VEGF and steroid treatments. Upon systemic investigation, the patient was diagnosed with MM [

4]. It has been previously reported that subretinal exudation, which can be seen in diabetic maculopathy, may increase the frequency of the rare PM promoting immunoglobulin accumulation to the subretinal pigment epithelium and enhancing the osmotic gradient [

21]. PM can be unilateral and misdiagnosed as DME, adult vitelliform dystrophy, or central serous chorioretinopathy. However, unlike these diseases, its treatment focuses on reducing serum immunoglobulin levels, utilizing treatment methods such as plasmapheresis, chemotherapy and systemic corticosteroids [

1].

4. Conclusions

OCT alone may not be sufficient to evaluate maculopathy in patients with diabetes mellitus. In suspected cases, medical history should be thoroughly reviewed, and FFA should be performed. Particularly in patients with treatment-resistant bilateral serous macular detachment accompanied by a silent macula on FFA, paraproteinemic diseases such as blood dyscrasias, should also be investigated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K.. and D.A.; methodology, E.K.; investigation, Y.G., D.A.; resources, Y.G.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.G., D.A. and E.K.; writing—review and editing, D.A. and E.K.; supervision, Y..G.; funding acquisition, Y.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable, as this is a retrospective case study.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mansour, A.M.; Arevalo, J.F.; Badal, J.; Moorthy, R.S.; Shah, G.K.; Zegarra, H.; Pulido, J.S.; Charbaji, A.; Amselem, L.; Lavaque, A.J.; Casella, A.; Ahmad, B.; Paschall, J.G.; Caimi, A.; Staurenghi, G. Paraproteinemic maculopathy. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1925–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hikichi, T.; Ohtsuka, H.; Higuchi, M.; Matsushita, T.; Ariga, H.; Kosaka, S.; Matsushita, R. Causes of macular serous retinal detachments in Japanese patients 40 years and older. Retina 2009, 29, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otani, T.; Kishi, S.; Maruyama, Y. Patterns of diabetic macular edema with optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999, 127, 688–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayadev, C.; Gupta, I.; Gopi Krishna Gadde, S. Atypical Refractory Macular Edema: Are We Missing Something? J Ophthalmic Vis Res. 2022, 17, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavriatopoulou, M.; Musto, P.; Caers, J.; et al. European myeloma network recommendations on diagnosis and management of patients with rare plasma cell dyscrasias. Leukemia 2018, 32, 1883–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattar, M.; Bazarbachi, A.; Abduljalil, O.; Francis, B.; Alam, A.; Blunk, V. Epidemiology, Treatment Trends, and Outcomes of Multiple Myeloma in the Middle East and Africa: A Systematic Review. Clin Hematol Int. 2024, 6, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yu, Q.; Wei, G.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y.; Hu, K.; Hu, Y.; Huang, H. Measuring the global, regional, and national burden of multiple myeloma from 1990 to 2019. BMC Cancer 2021, 21, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdrabou, A.K.; Sharif, F.A.; Fakih, R.E.; Hashmi, S.; Khafaga, Y.M.; Alhayli, S.; Zahrani, H.A.; Ahmed, S.; Fraih, F.A.; Shaheen, M.; Rasheed, W.; Chaudhri, N.A.; Mohareb, F.A.; Khalil, H.; Aljurf, M.; Hanbali, A. Outcomes of autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. 2021, 41, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazandjian, D. Multiple myeloma epidemiology and survival: A unique malignancy. Semin Oncol. 2016, 43, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyle, R.A.; Gertz, M.A.; Witzig, T.E.; et al. Review of 1027 patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003, 78, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, K.J.; Kempin, S.; Milman, T.; Finger, P.T. Ocular manifestations of multiple myeloma: three cases and a review of the literature. Optometry 2011, 82, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgman, C.J. Concomitant multiple myeloma spectrum diagnosis in a central retinal vein occlusion: a case report and review. Clin Exp Optom. 2016, 99, 309–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mani, M.; Kasturi, N.; Sravya, R.; et al. Orbital plasmacytoma as the presenting feature in multiple myeloma. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2020, 1120672120929959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Madi, H.A.; Bonshek, R.; et al. Cloudy corneas as an initial presentation of multiple myeloma. Clin Ophthalmol (Auckland, NZ) 2014, 8, 813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benjamin, I.; Taylor, H.; Spindler, J. Orbital and conjunctival involvement in multiple myeloma: report of a case. Am J Clin Pathol. 1975, 63, 811–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmas-Alamdari, D.; Sodhi, G.S.; Shenouda, T.A. Bilateral proptosis in a case of recurring multiple myeloma: uncommon orbital presentation of plasmacytoma. Int Med Case Rep J. 2020, 13, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, L.A.; Rodger, D.C. Bilateral macular detachments, venous stasis retinopathy, and retinal hemorrhages as initial presentation of multiple myeloma: a case report. Retin Cases Br Reports 2014, 8, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, A.; Goulart, A.; Ribeiro, A.; et al. Orbital Plasmacytoma, An Uncommon Presentation of Advanced Multiple Myeloma. Eur J case reports Intern Med. 2020, 7, 001149. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, R.B.; Singhal, S.; Sinha, S.; Cho, J.; Nguyen, A.X.; Dhingra, L.S.; Kaur, S.; Sharma, V.; Agarwal, A. Ocular complications of plasma cell dyscrasias. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2023, 33, 1786–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, J.A.; Olson, D.J.; Zhang, A.Y. Hyperviscosity Retinopathy Due to Waldenström Macroglobulinemia: A Case Report and Literature Review. J Vitreoretin Dis. 2021, 5, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, J.M.; Butrus, S.I.; Ashraf, M.F.; et al. Multiple myeloma presenting with bilateral exudative macular detachments. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1995, 73, 81–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Color fundus images of the patient at initial presentation. Extensive retinal hemorrhages and microaneurysms with occasional laser spots are seen in both eyes.

Figure 1.

Color fundus images of the patient at initial presentation. Extensive retinal hemorrhages and microaneurysms with occasional laser spots are seen in both eyes.

Figure 2.

OCT images of the patient at the initial presentation. Significant subretinal fluid and intraretinal edema particularly on the left eye, were seen.

Figure 2.

OCT images of the patient at the initial presentation. Significant subretinal fluid and intraretinal edema particularly on the left eye, were seen.

Figure 3.

OCT images of the right eye after three doses of intravitreal bevacizumab. Intraretinal edema has resolved, but subretinal fluid persists and subretinal deposits are becoming more apparent.

Figure 3.

OCT images of the right eye after three doses of intravitreal bevacizumab. Intraretinal edema has resolved, but subretinal fluid persists and subretinal deposits are becoming more apparent.

Figure 4.

FFA shows bilateral capillary nonperfused ischemic retinal areas.

Figure 4.

FFA shows bilateral capillary nonperfused ischemic retinal areas.

Figure 5.

Macular OCT images of patient taken at 1st (a,b), 2nd (c,d), 3rd (e,f), 5th months (g,h) and 1st year (i,j) after the initiation of systemic chemotherapy.

Figure 5.

Macular OCT images of patient taken at 1st (a,b), 2nd (c,d), 3rd (e,f), 5th months (g,h) and 1st year (i,j) after the initiation of systemic chemotherapy.

Figure 6.

Bilateral macular OCT images of the patient at the first week after left cataract surgery. While mild macular edema continues on the right, numerous intraretinal cysts accompany dense subretinal serous fluid on the left.

Figure 6.

Bilateral macular OCT images of the patient at the first week after left cataract surgery. While mild macular edema continues on the right, numerous intraretinal cysts accompany dense subretinal serous fluid on the left.

Figure 7.

Macular OCT images of the patient after 3 monthly intravitreal bevacizumab injections. Subretinal serous fluid accumulation is clearly visible in both maculas.

Figure 7.

Macular OCT images of the patient after 3 monthly intravitreal bevacizumab injections. Subretinal serous fluid accumulation is clearly visible in both maculas.

Figure 8.

Color fundus imaging (a, b) and FFA (c, d) of both eyes at the second month following systemic chemotherapy. Capillary dropouts can be observed in the right eye and visible areas of the left eye.

Figure 8.

Color fundus imaging (a, b) and FFA (c, d) of both eyes at the second month following systemic chemotherapy. Capillary dropouts can be observed in the right eye and visible areas of the left eye.

Figure 9.

OCT images of both eyes at the 2nd month following systemic chemotherapy. It can be observed that the macular edema has regressed, but the ellipsoid zone is disrupted.

Figure 9.

OCT images of both eyes at the 2nd month following systemic chemotherapy. It can be observed that the macular edema has regressed, but the ellipsoid zone is disrupted.

Figure 10.

The fundus images of the patient at the 8th month following systemic treatment (a, b). On the left, a fibrotic band attached to the retina in the superior arc is observed, similar to DR.

Figure 10.

The fundus images of the patient at the 8th month following systemic treatment (a, b). On the left, a fibrotic band attached to the retina in the superior arc is observed, similar to DR.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).