1. Introduction

We speak of masked forms when uveitis, i.e. the inflammation of the uvea, presents itself with atypical symptoms or when the inflammation itself is masked by other eye diseases.

In ophthalmology, the term “masquerade syndrome” or uveitis masquerade syndrome (UMS) describes malignant and non-malignant conditions that mimic intraocular inflammatory processes.

It was first used in 1967 by Theodore FH to describe a conjunctival carcinoma presented as a chronic conjunctivitis [

1].

The UMSs are a group of systemic and ocular disorders characterized by the appearance of inflammatory signs, more specifically of intraocular infiltrating cells, and chronic symptoms that are unresponsive to conventional treatment. Conventionally, UMSs is divided into two distinct categories: malignant masquerade syndromes and non-malignant syndromes. The former encompasses both systemic and intraocular neoplasm. At the same time, the latter comprises a wide range of benign non-inflammatory conditions such as intraocular foreign body, retinitis pigmentosa, ocular amyloidosis, ocular ischemic syndrome, and retinal detachment.

The prevalence of UMS resulted lower in the general population, compounded by misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis. Two retrospective epidemiology studies analyzed UMS prevalence.

A study conducted by Rothova et al. at a tertiary center revealed that the prevalence of UMS among patients presenting with inflammatory syndromes is 6%. 1.8% were confirmed as malignant UMS, while the remainder were benign conditions mimicking inflammatory diseases [

2].

The Grange study documented a similar prevalence of UMS, reporting a rate of 2.5%. This finding is supported by the National Eye Institute's data, which indicate that 21 out of 853 patients diagnosed with uveitis between 2004 and 2012 also met the diagnostic criteria for a neoplastic masquerade syndrome.

Patients presenting with uveitis manifestations tend to be older in comparison with those presenting with uveitis for the first time. Furthermore, uveitis is most frequently observed among females. However, this prevalence in gender is not revealed in cases of UMS [

3].

Although UMS are rare, it is imperative to be aware of the clinical conditions and presentations that mimic uveitis and to arrive at an early diagnosis of the masquerade pathology, to preserve visual acuity.

In cases of neoplastic masqueraders, early diagnosis has been proven to be a critical factor in survival outcomes, as it can potentially prevent the progression of cancer and save lives.

2. Systemic Diseases Related Masquerade Syndrome

Primary intraocular lymphoma (PIOL) continues to be the most common neoplasm that can mimic nonspecific uveitis.

Historically known as reticulum cell sarcoma, PIOL is a rare form of non-Hodgkin's high-grade B-cell lymphoma, although rare T-cell variants have also been described. PIOL has a wide range of presentations.

Most commonly, patients present with painless vision blurring. At ophthalmoscopic evaluation cellular inflammation into the vitreous humor can be appreciated, resembling an intermediate uveitis. It can be associated with subretinal creamy yellow infiltrations or deep sub-retinal infiltrations, while it is very rare the involvement of the anterior segment.

Early diagnosis is critical to improve survival chances as up to 80% of PIOL determine a CNS involvement [

4].

Much rarer is ocular secondary involvement in patients with systemic lymphoma, which is usually represented by uveal lesions.

Much more frequent, although always rare in the general population, is ocular involvement in leukemia, which usually presents as direct retinal lymphoblastic infiltration [

5].

The orbit can also be the site, albeit rare, of plasma neoplasms, such as orbital plasmacytoma. Orbital plasmacytoma is a particular plasma cell proliferative condition of monoclonal immunoglobulin chains from differentiated B cells. It is present with non-specific signs as orbital cellulitis, exophthalmos, diplopia, chemosis [

6].

Ocular metastasis and primary uveal melanoma only rarely masquerade as uveitis. The presence of uveitis in the context of a primary or secondary tumor, manifesting in either the anterior chamber or the vitreous as vitritis, has been documented. Pigmented cells from intraocular melanomas may also disperse and be wrongly identified as inflammatory cells [

7,

8].

Additionally, cases of scleritis and choroidal effusion have been reported. They can presented at the first time as UMS. [

9].

Retinoblastoma, the most frequent malignant intraocular tumor in childhood, has been documented to present mimicking different conditions. Orbital cellulitis-like presentations, as well as tumor seeds disseminating in the anterior chamber and mimicking iridocyclitis, have been reported in the literature.

Diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma is also known to closely resemble anterior uveitis as it is more prone to presenting with anterior chamber seeding and pseudohypopyon [

10].

Among non-malignant conditions that present with symptoms like those of uveitis, endophthalmitis is of particular significance. It is imperative to differentiate between these two conditions in a timely manner, as endophthalmitis necessitates prompt treatment to mitigate the risk of visual impairment.

While acute endophthalmitis presents with specific clinical signs, chronic endophthalmitis, post-operative or post-traumatic, and secondary, ophthalmitis have a more insidious onset with an involvement of both the anterior chamber and the vitreous [

11].

Retinal detachment if long-standing, can present accompanied by synechiae, anterior uveitis, and vitritis [

12].

Central serous chorioretinopathy is often misdiagnosed as posterior uveitis, aggravating the visual prognosis of patients [

13].

The presence of metallic foreign bodies in the eye, if not promptly result, can result in mechanical and chemical injuries presenting at a later stage as unilateral steroid-resistant uveitis accompanied by siderotic coloration of the iris and vitreous. Pigment dispersion syndrome is characterized by pigmented deposits on the corneal endothelium and atrophic areas on the iris, which can lead to misdiagnosing it as herpetic uveitis [

14].

Ocular amyloidosis can be misdiagnosed as vitreous as it usually appears with bilateral cobwebs, sheet-like veils, or strings of pearl-like white opacities [

15].

Especially in elderly patients, a dense vitritis from Toxoplasma gondii infection may mask a primary lymphoma of the central nervous system. Therefore, in such cases it is mandatory not only to test for Toxoplasma IgG antibodies, but also cytofluorimetry and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to rule out lymphoma [

16].

Similarly, sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, syphilis, Behçet's disease, birdshot chorioretinitis can also present with vitritis, and it is important to distinguish these forms by means of laboratory tests, chest X-rays and computer tomography (CT) scans [

17].

Some drugs can cause vitritis simulating UMS. Among these, in Literature are reported prostaglandin analogs, metipranolol, corticosteroids, cholinomimetics, brimonidine and certain antibiotics [

18]. Moreover, some intraocular drugs cause uveitis, such as brolucizumab that appears after a few weeks after the intraocular injection [

19].

It is also known certain antineoplastic drugs can mimic uveitis, such as vemurafenib (anti-BRAF), dabrafenib (anti-BRAF), nivolumab (anti-PD-1), ipilimumab (anti-CTLA-4), and Osimertinib (anti- EGFR), trametinib (anti-MEK), rituximab (anti-CD20). (20) (21) Therefore greater care should be observed in cancer patients diagnosed with lymphoma, metastatic cutaneous melanoma, lung adenocarcinoma, metastatic thyroid carcinoma, pleomorphic xanthoastrocytoma [

20,

21].

3. Symptoms

UMSs usually mimic intermediate uveitis, so they manifest with the same symptoms, which are floaters and blurred vision. In addition, they can present at onset with other highly variable symptoms, which make initial diagnosis very difficult. These are signs that are common to uveitis, such as redness, pain, eyelid edema, cellulitis. Diagnostic tests can be indispensable in these cases and get the underlying disease recognized.

4. Therapeutic Strategy

Treatment of masked uveitis syndromes is closely related to the underlying cause. Correctly identifying the underlying pathology is essential to set up effective and targeted therapy. It is common to need the involvement of other physicians, such as oncologists, hematologists, neurologists, infectiologists, rheumatologists, and general surgeons for the therapeutic strategy that takes into consideration the patient's characteristics, the severity of the disease, and the presence of other pathologies. Close follow-up of the patient is mandated to observe the response to therapy, any occurrence of complications or side effects.

In ocular lymphoma, the main treatment is systemic chemotherapy, which may be combined with radiotherapy, and in some cases intravitreal drugs (such as methotrexate) may be indicated: Uveal melanoma with radiotherapy, brachytherapy, transpupillary thermotherapy depending on size and location, while enucleation is reserved for larger melanomas. Retinoblastoma has chemotherapy as main treatment, radiotherapy for smaller neoplasms or as adjuvant treatment after surgery, in some cases enucleation is still needed.

CMV infections are treated with antiviral drugs, such as ganciclovir, valganciclovir, foscarnet. Ocular toxoplasmosis is treated with antiparasitic drugs such as pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and clindamycin, particularly clindamycin, which can be used as intravitreal injection.

The therapeutic approach to amyloidosis depends on the specific type of disease, the severity of symptoms, and the organs involved. Because there are different forms of amyloidosis, an accurate diagnosis is essential to set the most appropriate treatment.

Sarcoidosis is treated with corticosteroids and in some cases with immunosuppressants such as methotrexate and azathioprine. In Behçet's disease, corticosteroids, immunosuppressive and biologic drugs such as infliximab and adalimumab are used to prevent recurrence and reduce disease severity and time to recurrence.

These are some examples of the possible therapeutic approaches depending on the underlying ml disease of masked syndrome.

In cases where the UMS is iatrogenic, it is important to consider discontinuation of the drug that caused it, assessing the risks to which the patient may be exposed.

In case of occurrence of complications such as retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, surgical approach is indicated. For UMS caused by a foreign body, surgical extraction will be performed.

5. Multimodal Imaging and Other Tests

The multimodal imaging can be useful in the diagnosis of UMSs. The choice of multimodal imaging and other diagnostic tests to be used depends on the patient's clinical presentation and the physician's diagnostic suspicion. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the retina and optic nerve is particularly useful in identifying early changes in masked syndromes, such as retinal thickening or the presence of fluid under the retina. The optical coherence tomography angiography (OCT-A), which is a technique that combines OCT with angiography, that can be useful in identifying vascular abnormalities that may be associated with UMS, such as vasculitis. Fluorangiography (FA) which is used to visualize fluid leaks or other abnormalities in the blood vessels that may be associated with UMSs. Fundus Autofluorescence (FAF) can be useful to identify changes in the retina that may be associated with UMS such as macular degeneration and atrophy. Anterior segment imaging (AS-OCT), which can be useful to identify alterations that may be associated with masked syndromes, such as iris inflammation.

However, the multimodal imaging in the UMSs has an unavoidable condition that there should be no opacities that could hinder the examination. Therefore, in forms of UMS the single or combined use of most multimodal imaging is prevented by situations of opacities of intraocular structures. This causes the examination by multimodal imaging to be partial or undefinable in most cases.

In addition to these imaging techniques, other diagnostic tests such as examination at the slit lamp and fundus examination can be used.

These examinations are also affected by the opacities, so the examination is frequently not entirely satisfactory to reach a timely diagnosis.

Next to these, laboratory tests are useful to identify especially infectious forms of UMSs. In addition, neuroimaging forms as MRI and CT-scan are often to be considered to identify the underlying cause by UMS. CT-scan of the globe and the orbit is used to detect metallic foreign bodies.

In this regard, very important in PIOL forms is MRI, the analysis of cerebral spinal fluid, as one third of patients have lymphoma cells and vitreous specimen showing from cytokine analysis a high IL-10 to IL-6 ratio.

6. Role of B-Scan Ocular Ultrasound

Ocular B-scan ultrasound (OBU) is a handy diagnostic tool, especially when other imaging techniques are limited. Frequently, this imaging technique is used whenever the dioptric media are not clear, such as in cases of corneal opacities, Tyndall phenomena in the anterior chamber, hemorrhages into the anterior chamber or vitreous cavity, cataract, pupillary seclusion with synechiae, vitreous haze, satellite retinal detachment. In most of these cases, the other multimodal imaging techniques based on the passing of light do not display the intraocular structures. The opacification of the dioptric media may impair also an accurate fundoscopic examination because if there is an opacification of dioptric media, the posterior ocular structures are not highlighted. Unlike other examinations, ultrasound can overcome media opacities [

22].

OBU studies vitreous, choroidal, and retinal abnormalities, as well as solid bulbar and orbital tumors, allowing a more accurate and earlier diagnosis [

23,

24,

25].

7. Benefits and Limits of B-Scan Ocular Ultrasound

This diagnostic method has some benefits as well as some disadvantages. The advantages include a non-invasive diagnostic technique, safe, no radiation, repeatable several times without risk for patient [

26].

Among the disadvantages are a lower resolution than other techniques, optical coherence tomography (OCT), for example and the operator dependence (the quality of the examination depends partly on the experience of the operator) [

26].

8. Methods

This is a consecutive, retrospective, nonrandomized study. This study was performed in accordance with the current version of the Declaration of Helsinki (52nd WMA General Assembly, Edimburgh, Scotland, October 2000). A total of 186 consecutive patients referred to our Eye Clinic of University Hospital Polyclinic of Bari, Italy, between January 2022 and December 2024 were included. Initially all complained of blurred vision accompanied by visual defect, photophobia, floaters, redness, ocular pain, photophobia, and tearing at hospitalization. All were undergone to B-scan ultrasonography (Quantel Medical ABSolu ® Ocular Ultrasound), by 12 MHz B probe.

Inclusion criteria were comprehensive of all patients with age between 10 to 85 years, visual acuity impairment less of 20/40 (Snellen charts). Patients who had previously undergone cataract surgery, vitrectomy or trabeculectomy for glaucoma were also included. Exclusion criteria were dense cataract, terminal glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, rhegmatogenous retinal detachment in the earlier stages. The written informed consent was obtained from all patients and their parents. The Institutional Review Board/Ethics Committee approval was obtained.

9. Results

During our clinical investigations, by subjecting all patients to OBU, we noticed that patients with a certain diagnosis had overlapping ultrasound pictures, which led us to focus on certain findings. We realized the ultrasound element common to most was the vitreous corpuscles and assessed that in some diagnoses this could be associated with other characteristic ultrasound patterns listed below. Finally, they have got diagnosis: fifteen PIOL, six systemic lymphoma, one orbital plasmacytoma, fourteen uveal melanoma, twelve metastasis, thirty-one endogenous endophthalmitis, six retinal detachment, seven central serous retinopathy, fourteen metallic foreign bodies, two ocular amyloidosis, twenty-eight toxoplasmosis, sixteen sarcoidosis, eight tuberculosis, nine syphilis, four birdshot chorioretinitis, thirteen are drug-induced UMSs.

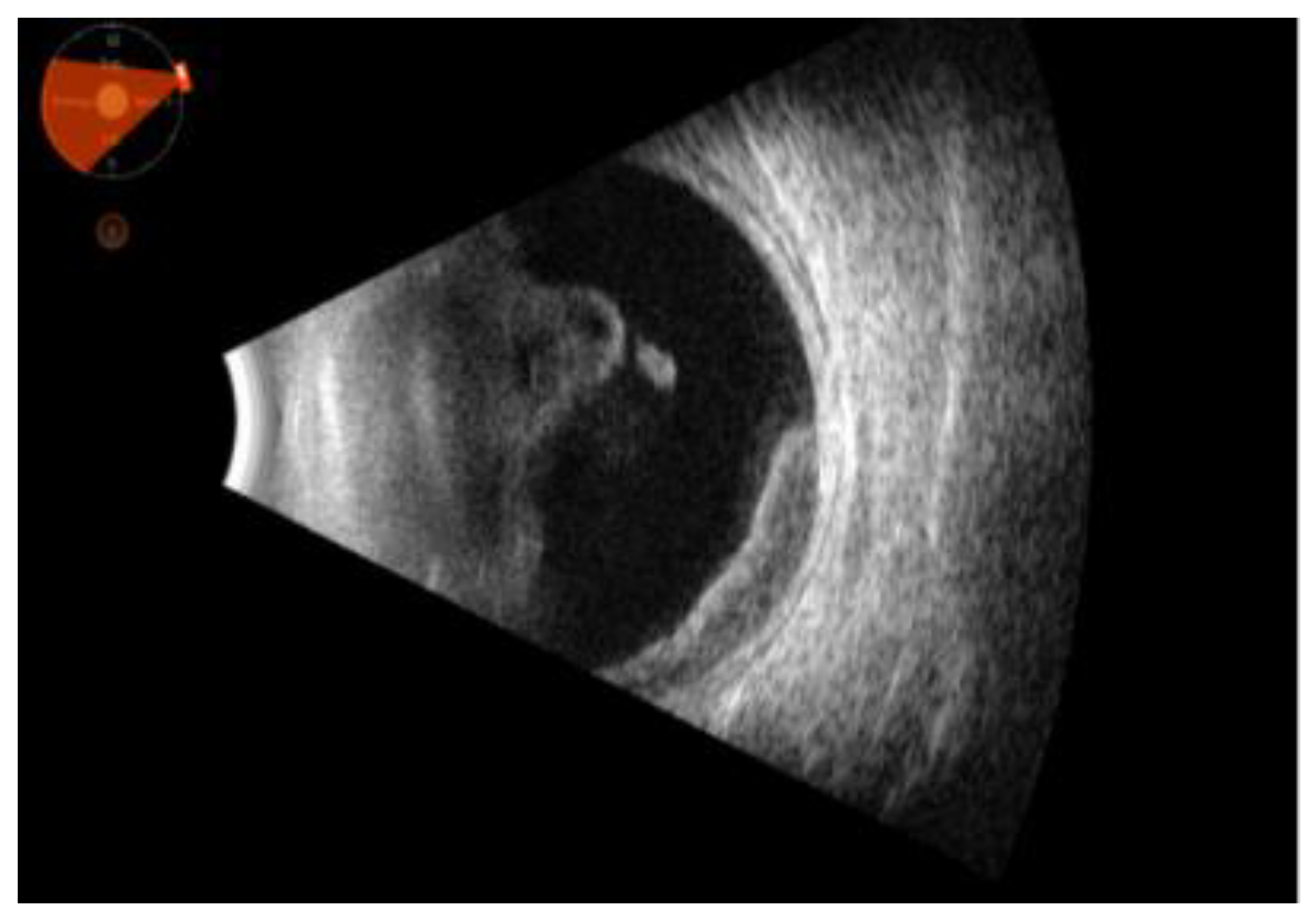

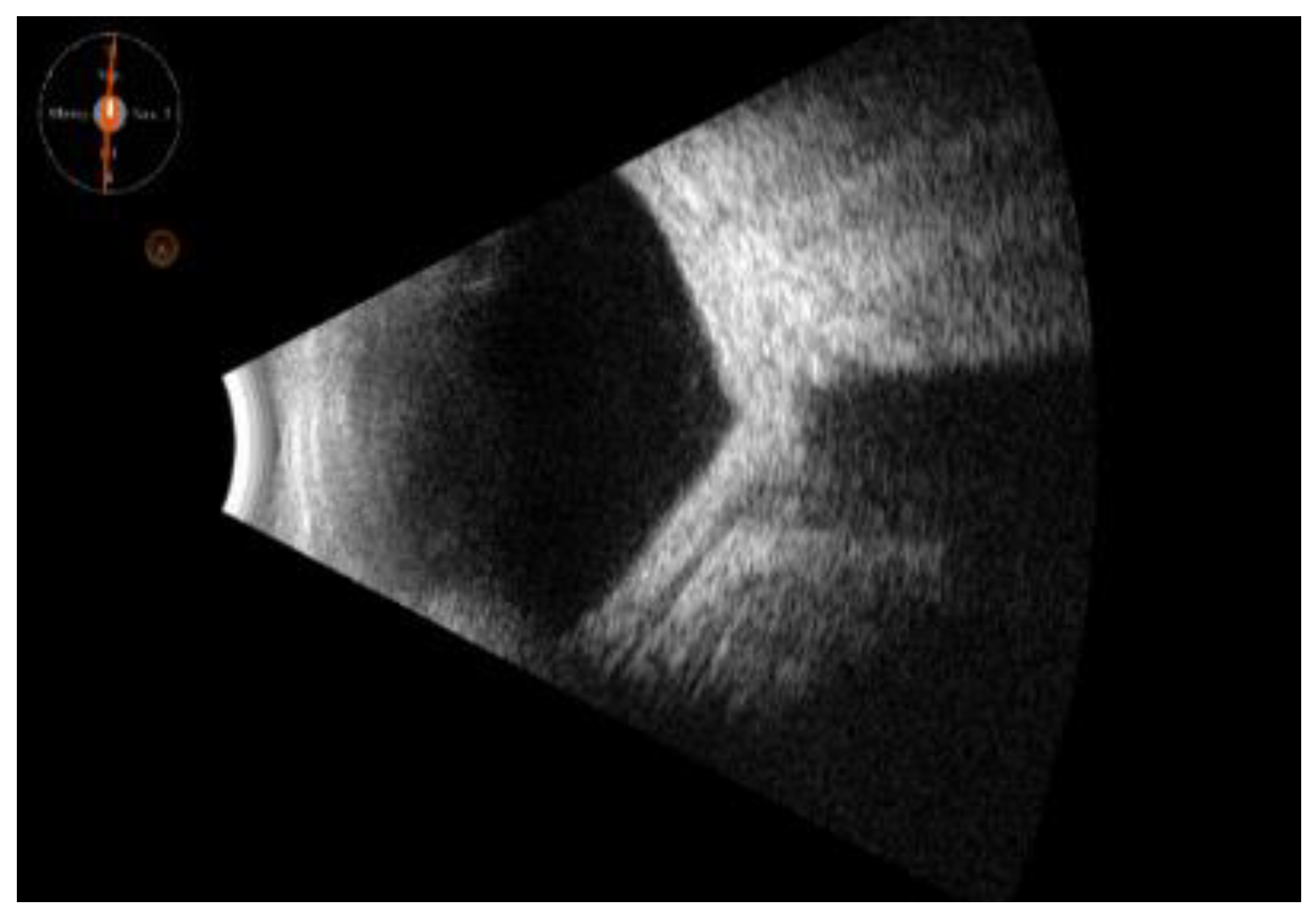

10. B-Scan Sonography Patterns

Vitreous patterns: The vitreous appears with abundant corpuscular movements, and the posterior vitreous seems organized in blocks or clouds, with or without vitreous detachment. Vitreous corpuscles can be classified as: 1. mild (finely dispersed forward the posterior vitreous), 2. moderate (coarsely organized on the posterior vitreous, with or without highly reflective membranes), 3. severe (abundant haze located in the entire vitreous cavity forward the posterior vitreous with or without highly reflective membranes).

In the UMSs, vitreous corpuscles can be inflammatory cells, purulent inflammatory cell, tumor cells, vitreous metastasis. The intensity of the vitreous corpuscles or their mobility alone cannot pinpoint the UMS (inflammatory, infectious, neoplastic, metastatic). Nevertheless, we have noticed that more frequently infectious forms (sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, candidiasis) can give the moderate or severe form, even in association with hyperreflective membranes. Unlike the other infectious forms, however, ocular infection with toxoplasma gondii causes an ultrasound picture of severe vitreous corpuscles but is not associated with hyperreflective membranes and the focus of infection is often not revealed by B-scan ultrasound.

Posterior exudation: in continuity with the retinal profile with vitreous adherences or organized in the vitreous cavity in single or multiple foci. Among these, some forms of intraocular lymphoma or systemic lymphoma, some bacterial or fungi infections, always associated with vitreous corpuscles.

Serous retinal detachment: frequently primitive or secondary to a solid tumor. It is normally associated of neoplasms, primitive o metastasis.

Choroid thickening: typical of sarcoidosis.

Choroidal detachment: usually associated with inflammatory or infection conditions.

Cell infiltration of the vitreous and/or retina and/or choroid and/or extrinsic muscles. It is diffuse sonographic picture of lymphoma and other lymphoproliferative conditions, ocular metastasis.

Solid tumor associated with vitreous and/or retina and/or choroid and/or extrinsic muscles and/or other orbital structures. It is typically of neoplasms, such as intraocular or orbital lymphoma, melanomas (associated with vitreous corpuscles especially in the necrotizing form), metastasis, retinoblastoma, leukemia, and other lymphoproliferative conditions. The solid tumor is also located in the vitreous. For i.e., it is more frequent for metallic foreign body with characterizing sonographic posterior shadowing.

Moreover, this technique led to detect some complications, identifying retinal detachments, neovascularization and other structural changes caused by inflammation.

When we suspected the underlying cause, we also performed serological, radiographic, MRI, CT, tissue biopsy, and vitreous sampling laboratory tests to confirm the diagnosis. For i.e., in suspect of toxoplasmosis we performed IgM and IgG for toxoplasma and/or detection of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on DNA by aqueous or vitreous fluid, for sarcoidosis the serological search of Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) e abdominal and chest CT, for PIOL vitrectomy sample with cytofluorimetry and cytokines levels and brain MRI, etc. Elderly patients with a history of lung or breast cancer or haematological disorders must be closely watched in suspicion of malignant nature of ultrasound findings.

11. Discussion and Conclusions

UMSs encompass a wide spectrum of diseases that can mimic uveitis, presenting clinicians with considerable challenges in diagnosis and management. It should be considered as a differential diagnosis in all patients presenting with undifferentiated or treatment-resistant ocular inflammation.

Despite the extensive use of laboratory and imaging techniques, the accurate diagnosis of these conditions can be delayed, resulting in delayed initiation of appropriate treatment for these patients.

Often this is due to ocular conditions that do not allow eye structures to be examined, such as dense opacities (cataract, corneal leucoma, vitreous haze, etc). The use of B-scan ultrasonography can help physicians distinguish among the different forms of UMSs, being able to allow an earlier diagnosis compared other imaging tools, such as MRI [

27]. Nevertheless, the OBU is not intended to replace other diagnostic tests in UMSs, but it can suggest correct initial discrimination to recognized different forms.

Being a non-invasive tool requiring little or no cooperation from the patient, it has proved very useful for all ages, especially in children where cooperation may be absent or poor [

28].

The use of B-scan ultrasonography in UMSs proved very useful in the first instance in emergency settings and for hospitalized patients, even when they had complicated and difficult systemic conditions, including poor mobility [

29]. In fact, the use of OBU in the emergency room has greatly increased, as reported in American insurance claims in 2018 [

30].

Moreover, it has proved very useful in UMSs caused by drug treatments, and in monitoring various therapy during the follow-ups [

31,

32].

OBU is a powerful diagnostic tool in the evaluation of UMS. Its practical and timely use allows for a prompt and accurate diagnosis, which is crucial in preventing further complications and initiating appropriate treatment. This non-invasive imaging technique provides detailed visualization of the eye's internal structures, enabling the identification of subtle abnormalities that may be missed during a standard clinical examination. However, while OBU is invaluable, it should not be used in isolation. To establish a definitive clinical diagnosis, it is often necessary to complement OBU findings with other diagnostic modalities, such as laboratory tests to assess inflammatory markers, radiological examinations to rule out other potential causes, and in some cases, sampling of the aqueous humor and vitreous for further analysis. This comprehensive approach ensures that all possible contributing factors are considered, leading to a more precise diagnosis and a tailored treatment plan for the patient.

While B-scan ultrasonography has proven valuable in evaluating UMS, we've encountered limitations in its practical application. A significant challenge lies in the substantial operator expertise required for accurate interpretation. Differentiating between various underlying causes, such as tumors, retinal detachments, or infectious processes, demands extensive experience in sonographic pattern recognition. Furthermore, precisely localizing abnormalities within the complex ocular structures affected by masquerade syndrome can be difficult even for seasoned sonographers. Subtle variations in echogenicity and anatomical relationships may be missed by less experienced operators, potentially leading to misdiagnosis or delayed treatment. This reliance on highly specialized skills underscores the need for rigorous training programs and continuous quality assurance measures to maximize the diagnostic yield of B-scan ultrasonography in these challenging cases. Future advancements in automated image analysis and standardized scanning protocols may help mitigate these limitations and improve the accessibility of this valuable diagnostic tool.

Author Contributions

All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for Authorship. Conceptualization, V.A., I.L., and S.G.; Methodology, V.A., R.D., S.G., P.F. and I.L.; Software, V.A., I.L., C.V., M.G.P., E.S., A.M.; Validation, V.A., R.D., P.F., S.G. and G.A.; Formal Analysis, V.A., I.L., C.V., A.M.; Investigation, V.A., I.L., C.V, and E.S.; Resources, V.A, I.L., C.V., M.G.P., E.S., A.M.; Data Curation, V.A., I.L., C.V., M.G.P. ; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, V.A., I.L., R.D., and S.G.; Writing – Review & Editing, V.A., I.L., R.D., and S.G.; Visualization, V.A., E.S. A.M., P.F., F.B., S.G., G.A.; Supervision, V.A., S.G., P.F., F.B., and G.A.; Project Administration, V.A., S.G., P.F., F.B., and G.A.; All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Rothova, A. Uveitis masquerade syndromes. Ophthalmology 2001, 108, 386–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothova, A.; Groen, F.; Ten Berge, J.C.E.M.; Lubbers, S.M.; Vingerling, J.R.; Thiadens, A.A.H.J. CAUSES AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF MASQUERADE SYNDROMES IN INTRAOCULAR INFLAMMATORY DISEASES. Retina 2021, 41, 2318–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grange, L.K.; Kouchouk, A.; Dalal, M.D.; Vitale, S.; Nussenblatt, R.B.; Chan, C.-C.; Sen, H.N. Neoplastic Masquerade Syndromes in Patients With Uveitis. American Journal of Ophthalmology 2014, 157, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupland, S.E.; Chan, C.C.; Smith, J. Pathophysiology of Retinal Lymphoma. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation 2009, 17, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dini, G.; Capolsini, I.; Cerri, C.; Massei, M.S.; Mastrodicasa, E.; Perruccio, K.; Gorello, P.; Caniglia, M.; Verrotti, A.; Arcioni, F. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia relapse presenting with optic nerve infiltration. SAGE Open Medical Case Reports 2023, 11, 2050313X231175020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zloto, O.; Vahdani, K.; Stack, R.; Verity, D.H.; Rose, G.E. Periocular Presentation of Solitary Plasmacytomas and Multiple Myeloma. Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery 2022, 38, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazy, N.; Harbour, J.W.; Dubovy, S.R.; Albini, T.A.; Sridhar, J.; Patel, N.; Hansen, E.D.; Uchiyama, E.; Rubsamen, P.E.; Correa, Z.M. Vitreous metastasis from cutaneous melanoma: diagnosis and management. ABO 2023, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Zhu, J.; Gao, T.; Li, B.; Yang, Y. Uveal Melanoma in the Peripheral Choroid Masquerading as Chronic Uveitis. Optometry and Vision Science 2014, 91, e222–e225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kafkala, C.; Daoud, Y.J.; Paredes, I.; Foster, C.S. Masquerade Scleritis. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation 2005, 13, 479–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blitzer, A.L.; Schechet, S.A.; Shah, H.A.; Blair, M.P. Retinoblastoma presenting as pseudohypopyon and preserved visual acuity. American Journal of Ophthalmology Case Reports 2021, 23, 101141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalouf, F.; Abdulaal, M.; Hamam, R.N. Chronic Postoperative Endophthalmitis: A Review of Clinical Characteristics, Microbiology, Treatment Strategies, and Outcomes. International Journal of Inflammation 2012, 2012, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joye, A.S.; Bhisitkul, R.B.; Pereira, D.D.S.; Gonzales, J.A. Rhegmatogenous retinal detachment masquerading as exudative panuveitis with intense anterior chamber inflammatory reaction. American Journal of Ophthalmology Case Reports 2020, 18, 100618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadia, M.; Jeannin, B.; Herbort, C. Central serous chorioretinopathy misdiagnosed as posterior uveitis and the vicious circle of corticosteroid therapy. J Ophthalmic Vis Res 2015, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, S.; Ralle, M.; Phan, I.T.; Francis, P.J.; Rosenbaum, J.T.; Flaxel, C.J. Occult intraocular foreign body masquerading as panuveitis: inductively coupled mass spectrometry and electrophysiologic analysis. J Ophthal Inflamm Infect 2012, 2, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dammacco, R.; Merlini, G.; Lisch, W.; Kivelä, T.T.; Giancipoli, E.; Vacca, A.; Dammacco, F. Amyloidosis and Ocular Involvement: an Overview. Seminars in Ophthalmology 2020, 35, 7–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalogeropoulos, D.; Afshar, F.; Kalogeropoulos, C.; Vartholomatos, G.; Lotery, A.J. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenges in acute retinal necrosis; an update. Eye 2024, 38, 1816–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta Majumder, P.; Khetan, V.; Biswas, J. Masquerade syndrome: A review of uveitic imposters. Asia-Pacific Journal of Ophthalmology 2024, 13, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, M.; Dutta Majumder, P.; Babu, K.; Konana, V.; Goyal, M.; Touhami, S.; Stanescu-Segall, D.; Bodaghi, B. Drug-induced uveitis: A review. Indian J Ophthalmol 2020, 68, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witkin, A.J.; Hahn, P.; Murray, T.G.; Arevalo, J.F.; Blinder, K.J.; Choudhry, N.; Emerson, G.G.; Goldberg, R.A.; Kim, S.J.; Pearlman, J.; et al. Brolucizumab-Associated Intraocular Inflammation in Eyes Without Retinal Vasculitis. Journal of VitreoRetinal Diseases 2021, 5, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitch-Harel, I.; Raskin, E.; Habot-Wilner, Z.; Friling, R.; Amer, R.; Kramer, M. Uveitis Induced by Biological Agents Used in Cancer Therapy. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation 2021, 29, 1370–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fardeau, C.; Bencheqroun, M.; Levy, A.; Bonnin, S.; Ferchaud, M.-A.; Fardeau, L.; Coscas, F.; Bodaghi, B.; Lebrun-Vignes, B. Uveitis Associated with Cancer Immunotherapy: Long-Term Outcomes. Immunotherapy 2021, 13, 1465–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aironi, V.; Gandage, S. Pictorial essay: B-scan ultrasonography in ocular abnormalities. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2009, 19, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, R.M. Efficacy of High Frequency Ultrasound in Localization and Characterization of Orbital Lesions. JCDR 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanni, V.; Iuliano, A.; Fossataro, F.; Russo, C.; Uccello, G.; Tranfa, F.; et al. The role of ultrasonography in differential diagnosis of orbital lesions. J Ultrasound. marzo 2021, 24, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinar, Z.; Chan, L.; Orlinsky, M. Use of Ocular Ultrasound for the Evaluation of Retinal Detachment. The Journal of Emergency Medicine 2011, 40, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malgotra, S.; Sharma, M.; Sharma, N. Visualizing the Spectrum: B-scan Ultrasonography Across Diverse Ocular Abnormalities: A Pictorial Review. TNOA Journal of Ophthalmic Science and Research 2024, 62, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boricean, N.G.; Scripcă, O.R. Multifocal Choroiditis and Panuveitis - difficulties in diagnosis and treatment. rjo 2017, 61, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seguin, J.; Le, C.-K.; Fischer, J.W.; Tessaro, M.O.; Berant, R. Ocular Point-of-Care Ultrasound in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr Emer Care 2019, 35, e53–e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blaivas, M.; Theodoro, D.; Sierzenski, P.R. A Study of Bedside Ocular Ultrasonography in the Emergency Department. Academic Emergency Medicine 2002, 9, 791–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, K.R.; Reardon, R.F.; Flores, G.; Whitcomb, V.; Christensen, E.W.; Watson, D.; Kharbanda, A. Trends in Medical Claims and Utilization of Limited Ultrasonography Among Emergency Physicians and Radiologists Within a Large Health Plan Provider. J of Ultrasound Medicine 2019, 38, 1279–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Zhang, H.; Chen, B.; Ding, W. A novel application of B-ultrasonography at various head positions in the diagnosis of untypical uveitis-glaucoma-hyphema (UGH) syndrome: A case report. Medicine 2019, 98, e13891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.L.; Elkhunovich, M.; Rankin, J.H. Child With Red Eye and Blurry Vision. Pediatr Emer Care 2017, 33, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).