Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

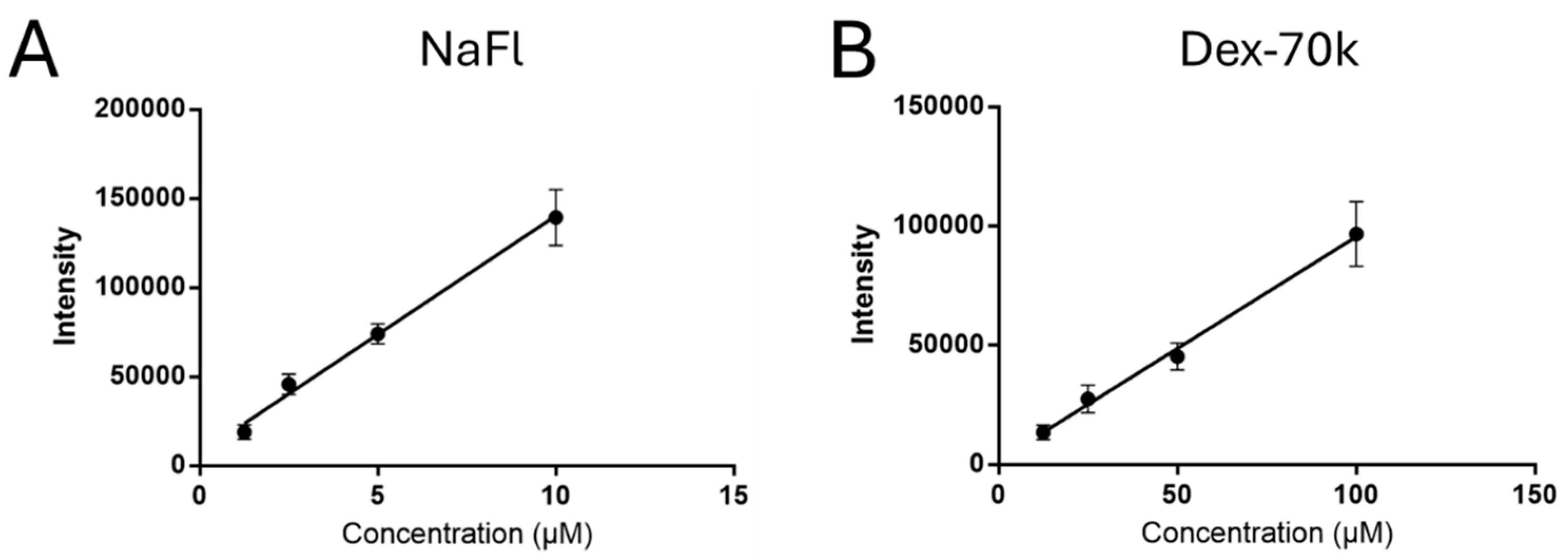

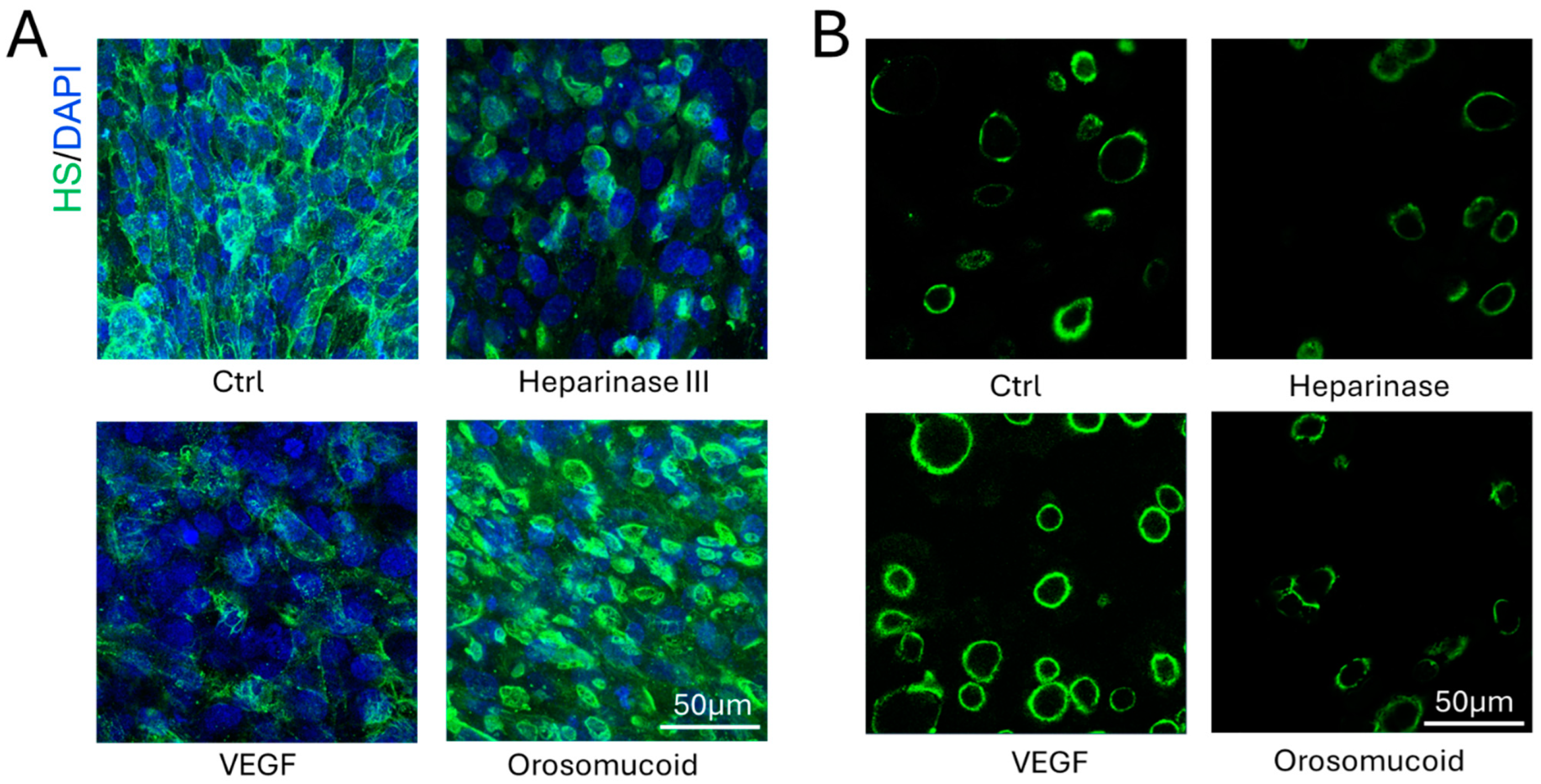

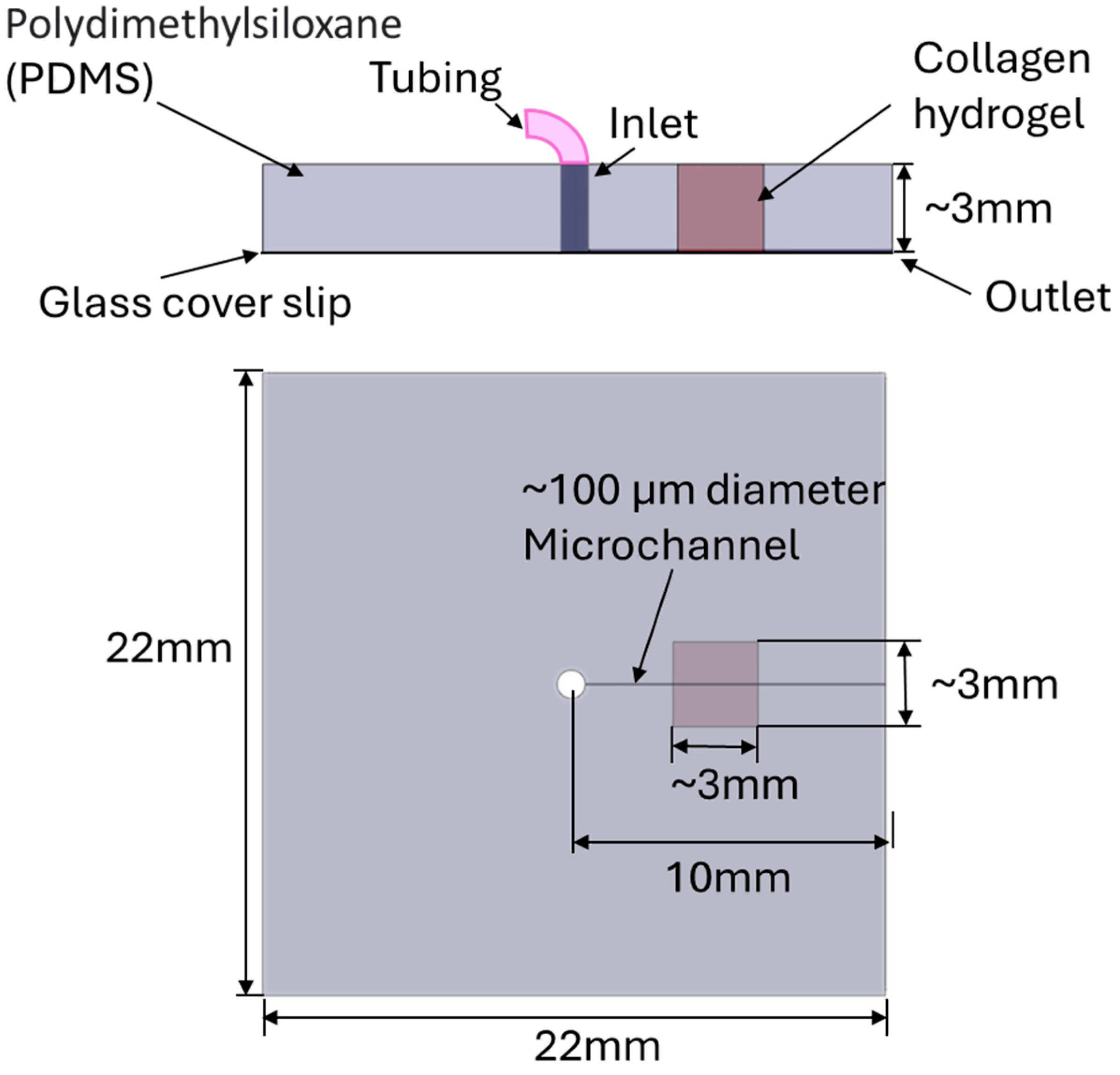

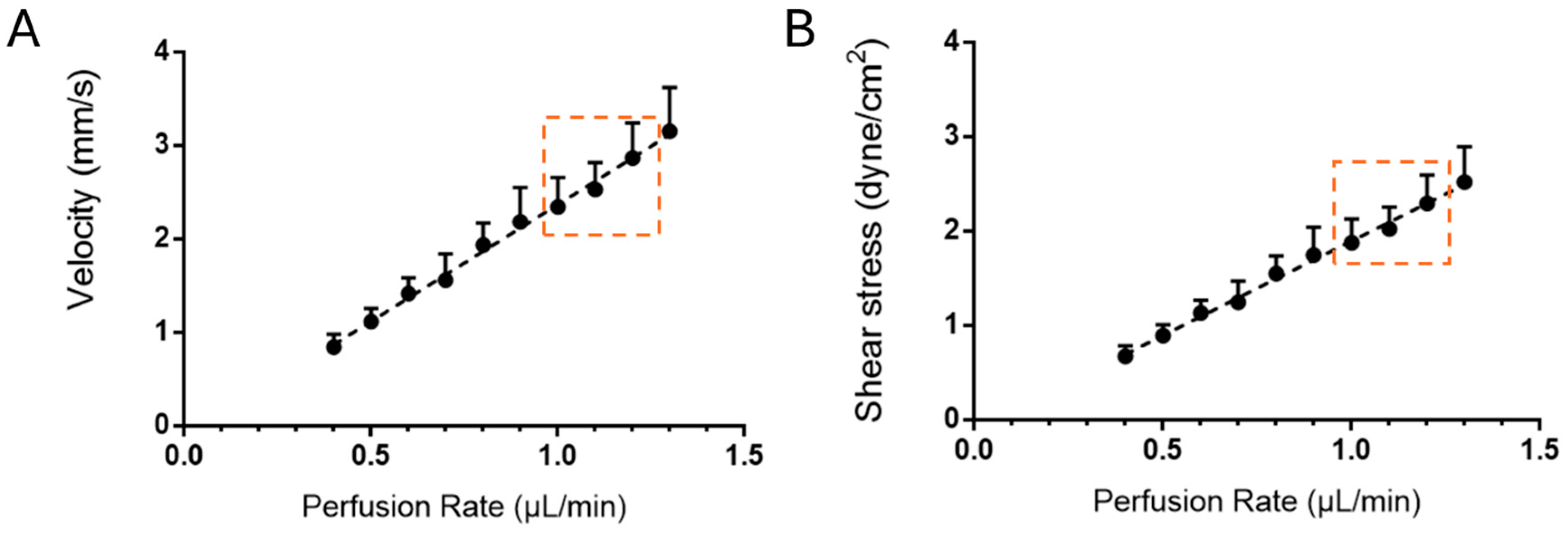

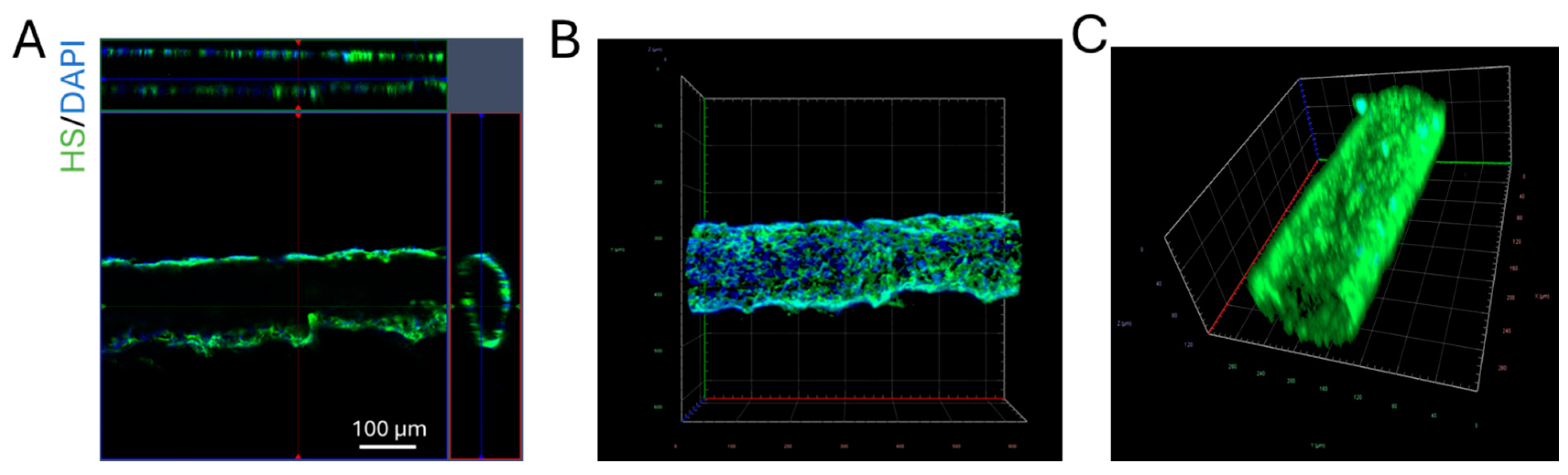

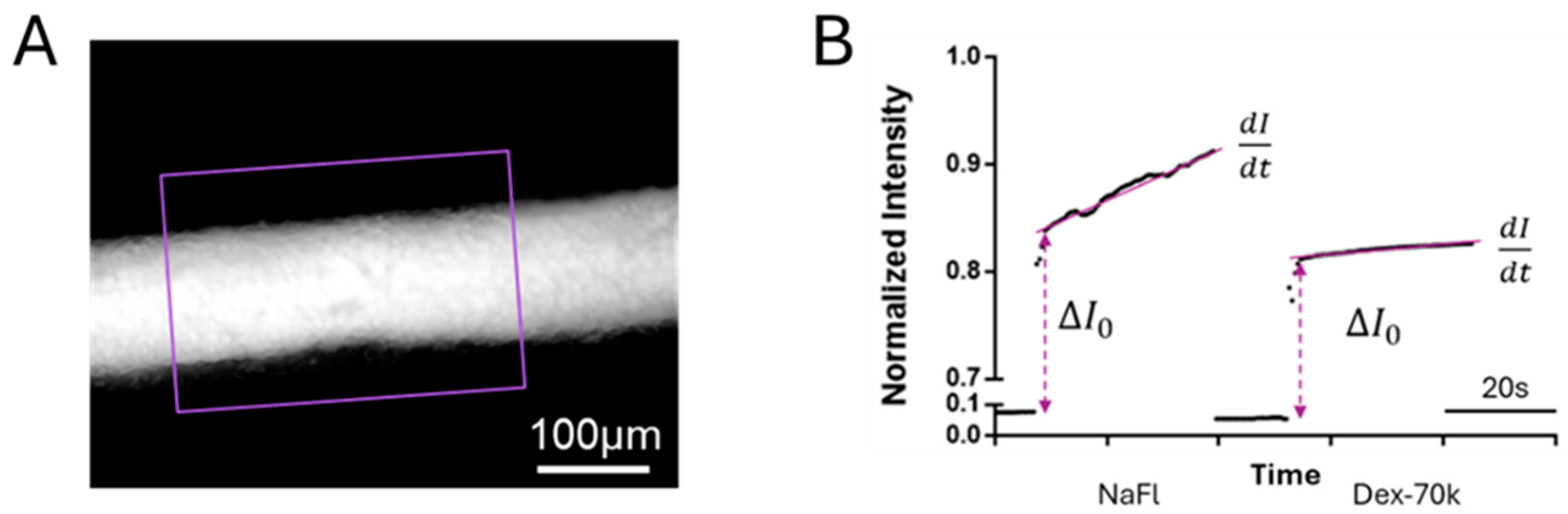

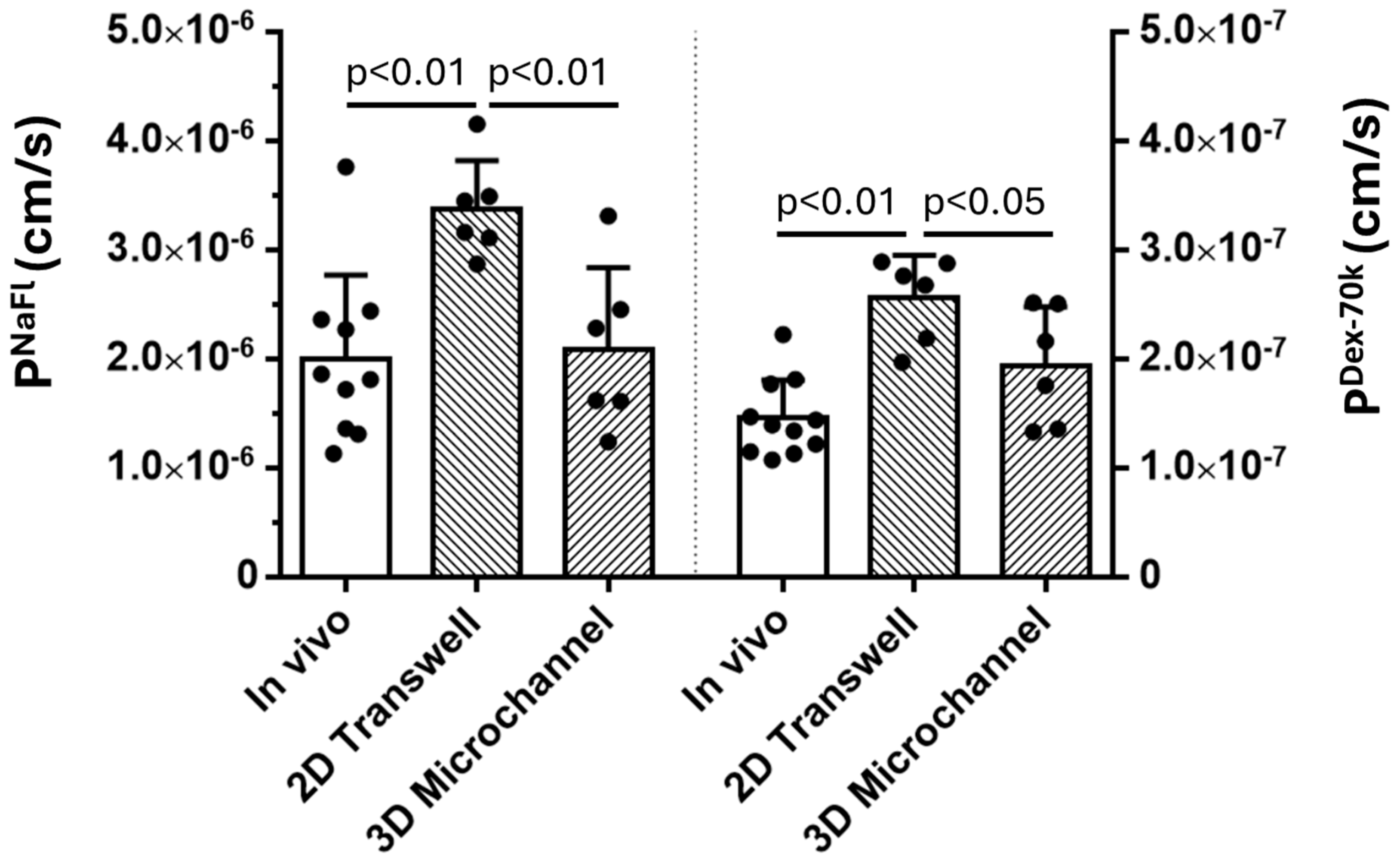

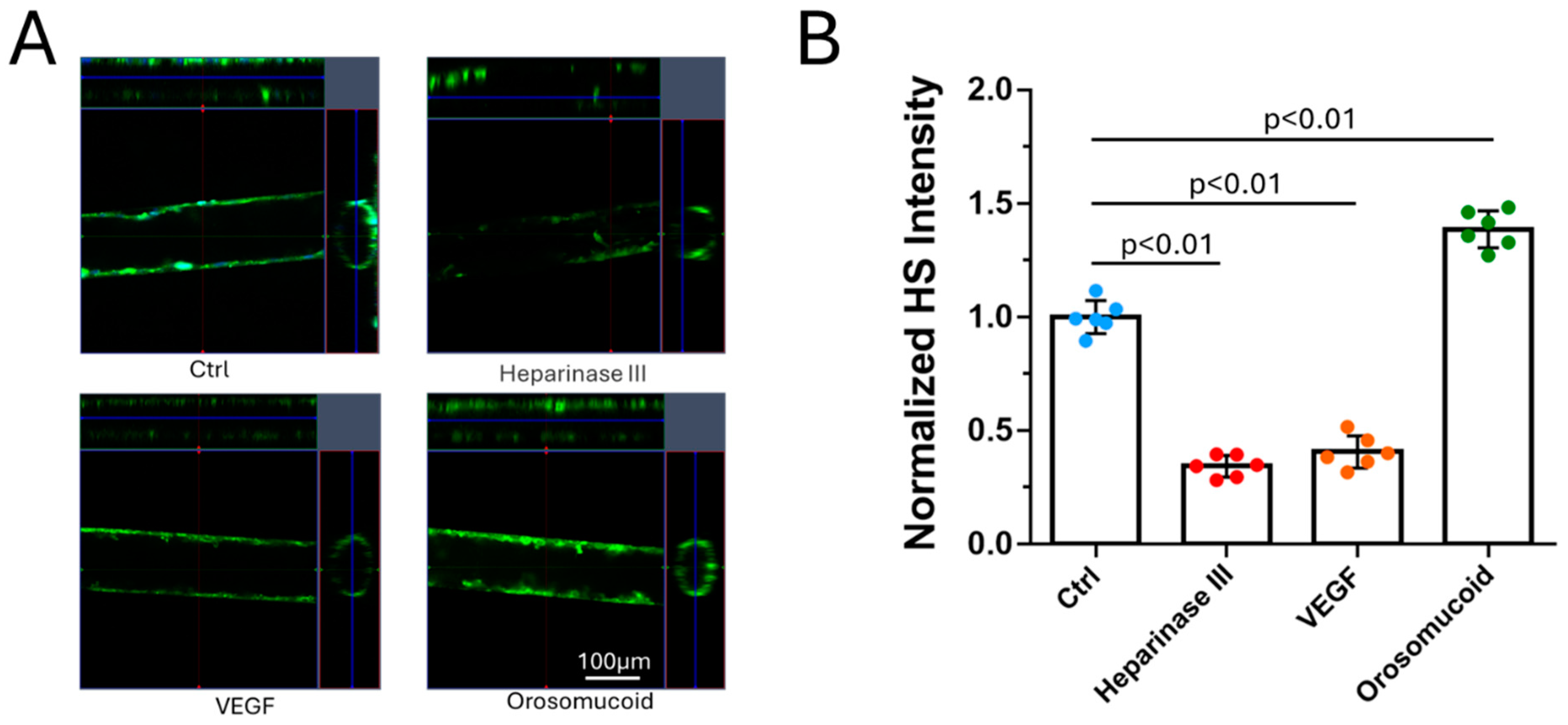

By utilizing PDMS, collagen hydrogel and a cell line for human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells, we generated a 3D microchannel-BBB model under physiological flows. This 3D BBB has a circular shaped cross-section and a diameter of ~100m, which can properly mimic the cerebral microvessel responsible for material exchange between the circulating blood and brain tissue. The permeability of the 3D microchannel-BBB to a small molecule (sodium fluorescein with molecular weight 376) and that to a large molecule (Dex-70k) are the same as those of rat cerebral microvessels. This 3D BBB model can replicate the response to a plasma protein, orosomucoid, a cytokine, VEGF, and an enzyme, heparinase III, in either rat cerebral or mesenteric microvessesels in terms of permeability and glycocalyx (heparan sulfate). It can also replicate the adhesion of a breast cancer cell, MDA-MB-231, in rat mesenteric microvessels with no treatment and with treatments with VEGF, orosomucoid and heparinase III. Because of difficulties in accessing human cerebral microvessels, this inexpensive and easy to assemble 3D human BBB model can be applied to investigate the BBB modulating mechanisms in health and in disease and to develop therapeutic interventions targeting tumor metastasis to the brain.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Generation of a 3D PDMS-Hydrogel Microchannel

2.3. Generation of a 3D Microchannel-BBB Under Flow

2.4. Quantification of Heparan Sulfate (HS) at the 3D Microchannel-BBB

2.5. Modulation of HS of the 3D BBB and MB231 by Various Agents

2.6. Quantification of 3D Microchannel-BBB Permeability

2.7. Quantification of MB231 Cell Adhesion to the 3D Microchannel-BBB Under Flow

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of the Solute Permeability of the 3D Microchannel-BBB with That of the 2D BBB and That of Rat Cerebral Microvessels

3.2. Effects of Heparinase III, VEGF and Orosomucoid on the HS of the 3D Microchannel-BBB

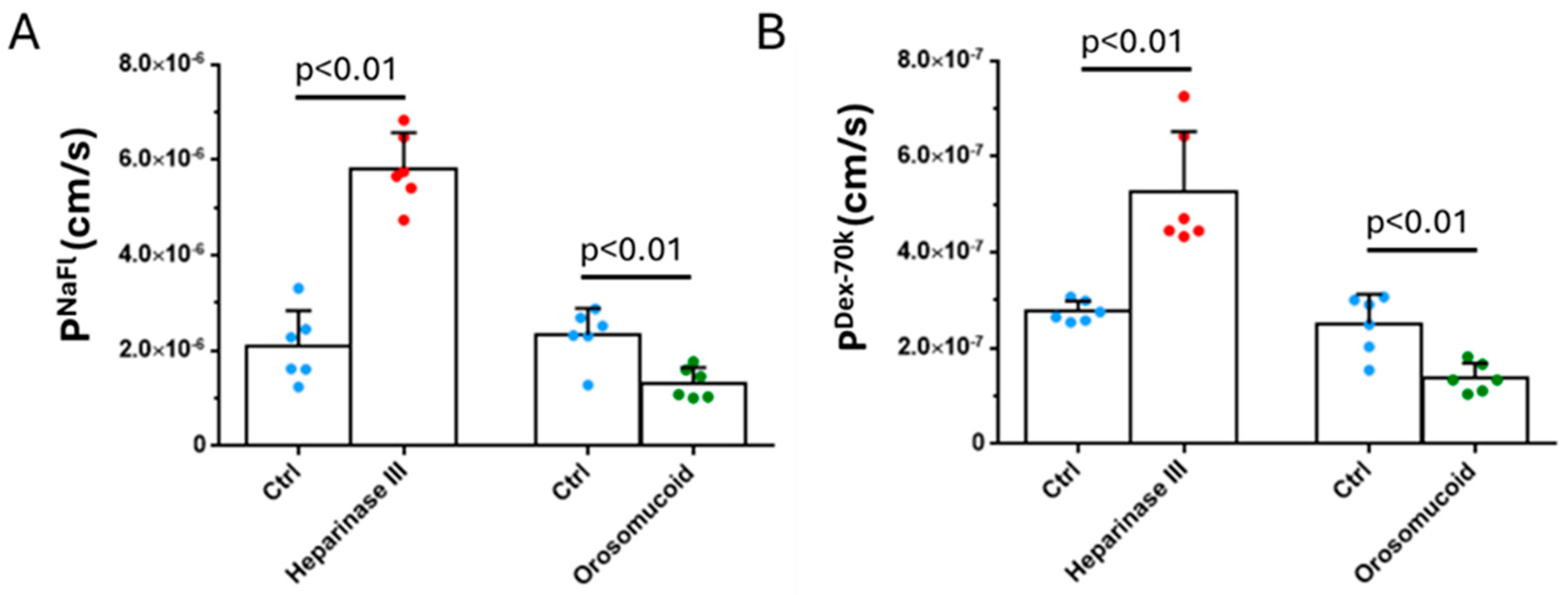

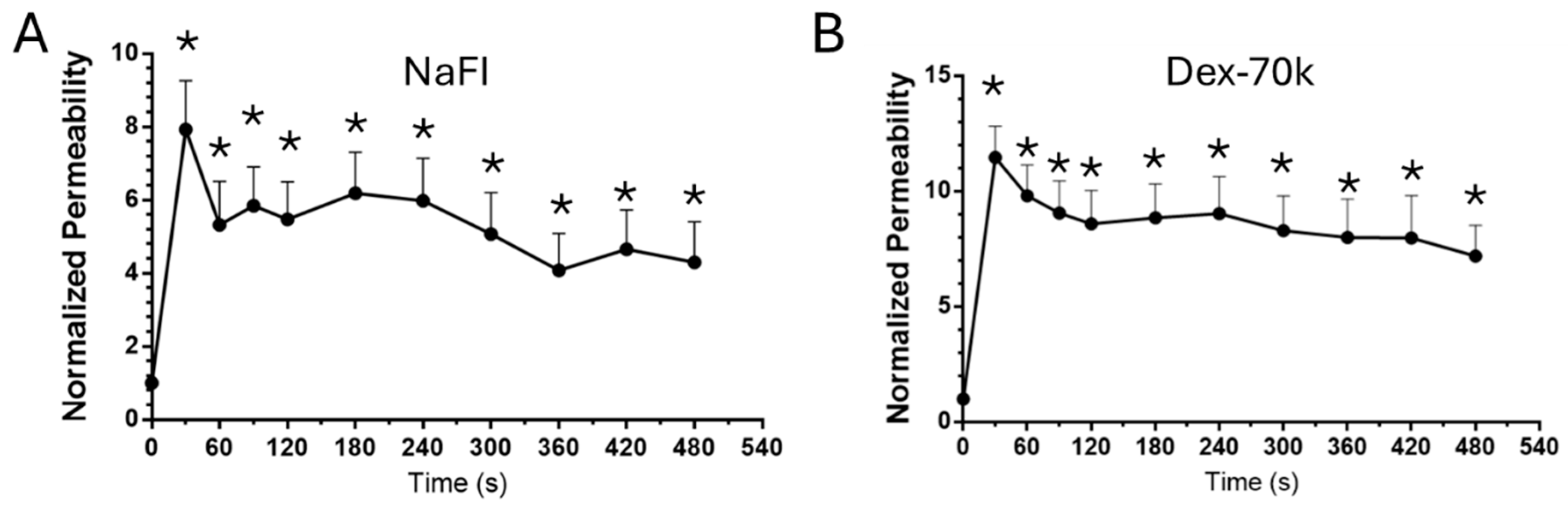

3.3. Effects of Heparinase III, Orosomucoid and VEGF on the Solute Permeability of the 3D Microchannel-BBB

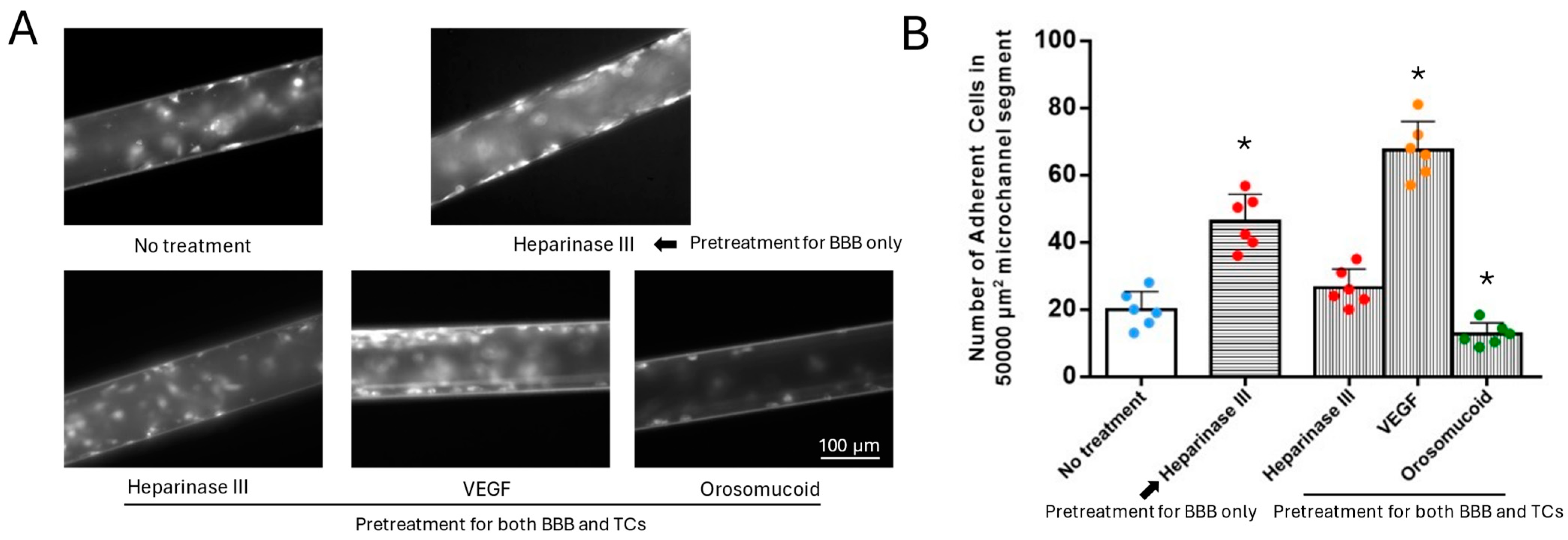

3.4. Effects of HS Modulation on MB231 Adhesion to the 3D Microchannel-BBB Under Flow

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Abbott, N.J.; Patabendige, A.A.K.; Dolman, D.E.M.; Yusof, S.R.; Begley, D.J. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010, 37, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-López, A.; Torres-Suárez, A.I.; Martín-Sabroso, C.; Aparicio-Blanco, J. An overview of in vitro 3D models of the blood-brain barrier as a tool to predict the in vivo permeability of nanomedicines. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 196, 114816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.; Heo, C.; Lee, L.P.; Cho, H. Human mini-blood–brain barrier models for biomedical neuroscience research: a review. Biomater. Res. 2022, 26, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamieson, J.J.; Searson, P.C.; Gerecht, S. Engineering the human blood-brain barrier in vitro. J. Biol. Eng. 2017, 11, 37–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watase, K.; Zoghbi, H.Y. Modelling brain diseases in mice: the challenges of design and analysis. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2003, 4, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogorad, M.I.; DeStefano, J.; Wong, A.D.; Searson, P.C. Tissue-engineered 3D microvessel and capillary network models for the study of vascular phenomena. Microcirculation 2017, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linville, R.M., et al., Human iPSC-derived blood-brain barrier microvessels: validation of barrier function and endothelial cell behavior. Biomaterials, 2019. 190-191: p. 24-37.

- Lee, S., et al., 3D brain angiogenesis model to reconstitute functional human blood-brain barrier in vitro. Biotechnol Bioeng 2020, 117, 748–748. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.S.; Bersini, S.; Gilardi, M.; Dubini, G.; Charest, J.L.; Moretti, M.; Kamm, R.D. Human 3D vascularized organotypic microfluidic assays to study breast cancer cell extravasation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, Y.; Choi, S.H.; Kim, E.; Bylykbashi, E.; Kim, J.A.; Chung, S.; Kim, D.Y.; Kamm, R.D.; Tanzi, R.E. Blood–Brain Barrier Dysfunction in a 3D In Vitro Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajal, C.; Ibrahim, L.; Serrano, J.C.; Offeddu, G.S.; Kamm, R.D. The effects of luminal and trans-endothelial fluid flows on the extravasation and tissue invasion of tumor cells in a 3D in vitro microvascular platform. Biomaterials 2020, 265, 120470–120470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagtiani, E.; Yeolekar, M.; Naik, S.; Patravale, V. In vitro blood brain barrier models: An overview. 2022, 343, 13–30. [CrossRef]

- Cucullo, L.; Hossain, M.; Rapp, E.; Manders, T.; Marchi, N.; Janigro, D. Development of a Humanized In Vitro Blood–Brain Barrier Model to Screen for Brain Penetration of Antiepileptic Drugs. Epilepsia 2007, 48, 505–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeon, J.H.; Na, D.; Choi, K.; Ryu, S.-W.; Choi, C.; Park, J.-K. Reliable permeability assay system in a microfluidic device mimicking cerebral vasculatures. Biomed. Microdevices 2012, 14, 1141–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivandzade, F.; Cucullo, L. In-vitro blood–brain barrier modeling: A review of modern and fast-advancing technologies. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2018, 38, 1667–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atkins, G.B. and M.K. Jain, Role of Krüppel-Like Transcription Factors in Endothelial Biology. Circulation Research, 2007. 100(12): p. 1686-1695.

- Fu, B.M. and J.M. Tarbell, Mechano-sensing and transduction by endothelial surface glycocalyx: composition, structure, and function. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med, 2013. 5(3): p. 381-90.

- Coisne, C.; Lyck, R.; Engelhardt, B. Live cell imaging techniques to study T cell trafficking across the blood-brain barrier in vitro and in vivo. Fluids Barriers CNS 2013, 10, 7–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, M.J.; Dong, C. Neutrophils influence melanoma adhesion and migration under flow conditions. Int. J. Cancer 2003, 106, 713–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slattery, M.J.; Liang, S.; Dong, C.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, M.; Fu, B.M.; Cai, B.; Fan, J.; Ozdemir, T.; Zhang, P.; et al. Distinct role of hydrodynamic shear in leukocyte-facilitated tumor cell extravasation. Am. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2005, 288, C831–C839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cucullo, L.; Hossain, M.; Puvenna, V.; Marchi, N.; Janigro, D. The role of shear stress in Blood-Brain Barrier endothelial physiology. BMC Neurosci. 2011, 12, 40–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griep, L.M.; Wolbers, F.; de Wagenaar, B.; ter Braak, P.M.; Weksler, B.B.; Romero, I.A.; Couraud, P.O.; Vermes, I.; van der Meer, A.D.; Berg, A.v.D. BBB ON CHIP: microfluidic platform to mechanically and biochemically modulate blood-brain barrier function. Biomed. Microdevices 2012, 15, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellgren, K.L.; Hawkins, B.T.; Grego, S. An optically transparent membrane supports shear stress studies in a three-dimensional microfluidic neurovascular unit model. Biomicrofluidics 2015, 9, 061102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, R.; Kim, H. Characterization of a microfluidic in vitro model of the blood-brain barrier (μBBB). Lab a Chip 2012, 12, 1784–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.I.; Abaci, H.E.; Shuler, M.L. Microfluidic blood–brain barrier model provides in vivo-like barrier properties for drug permeability screening. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2017, 114, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staicu, C.E.; Jipa, F.; Axente, E.; Radu, M.; Radu, B.M.; Sima, F. Lab-on-a-Chip Platforms as Tools for Drug Screening in Neuropathologies Associated with Blood–Brain Barrier Alterations. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, G.; Fang, Q.; den Toonder, J.M.J. Microfluidics for cell-based high throughput screening platforms—A review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 903, 36–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oddo, A.; Peng, B.; Tong, Z.; Wei, Y.; Tong, W.Y.; Thissen, H.; Voelcker, N.H. Advances in Microfluidic Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB) Models. 2019, 37, 1295–1314. [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Sun, H.; Li, X.; He, P. Leveraging avidin-biotin interaction to quantify permeability property of microvessels-on-a-chip networks. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2022, 322, H71–H86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Xu, J.; Bartolák-Suki, E.; Jiang, J.; Tien, J. Evaluation of 1-mm-diameter endothelialized dense collagen tubes in vascular microsurgery. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B: Appl. Biomater. 2020, 108, 2441–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linville, R.M.; Boland, N.F.; Covarrubias, G.; Price, G.M.; Tien, J. Physical and Chemical Signals That Promote Vascularization of Capillary-Scale Channels. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2016, 9, 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adriani, G., et al., A 3D neurovascular microfluidic model consisting of neurons, astrocytes and cerebral endothelial cells as a blood–brain barrier. Lab on a Chip, 2017. 17(3): p. 448-459.

- Brown, J.A.; Pensabene, V.; Markov, D.A.; Allwardt, V.; Neely, M.D.; Shi, M.; Britt, C.M.; Hoilett, O.S.; Yang, Q.; Brewer, B.M.; et al. Recreating blood-brain barrier physiology and structure on chip: A novel neurovascular microfluidic bioreactor. Biomicrofluidics 2015, 9, 054124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, T.-E.; Mustafaoglu, N.; Herland, A.; Hasselkus, R.; Mannix, R.; FitzGerald, E.A.; Prantil-Baun, R.; Watters, A.; Henry, O.; Benz, M.; et al. Hypoxia-enhanced Blood-Brain Barrier Chip recapitulates human barrier function and shuttling of drugs and antibodies. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herland, A.; van der Meer, A.D.; FitzGerald, E.A.; Park, T.-E.; Sleeboom, J.J.F.; Ingber, D.E. Distinct Contributions of Astrocytes and Pericytes to Neuroinflammation Identified in a 3D Human Blood-Brain Barrier on a Chip. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0150360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajal, C.; Offeddu, G.S.; Shin, Y.; Zhang, S.; Morozova, O.; Hickman, D.; Knutson, C.G.; Kamm, R.D. Engineered human blood–brain barrier microfluidic model for vascular permeability analyses. Nat. Protoc. 2022, 17, 95–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winkelman, M.A.; Kim, D.Y.; Kakarla, S.; Grath, A.; Silvia, N.; Dai, G. Interstitial flow enhances the formation, connectivity, and function of 3D brain microvascular networks generated within a microfluidic device. Lab a Chip 2021, 22, 170–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Guo, Z.; Kulkarni, S.; Norman, D.; Zhang, S.; Chung, T.D.; Nerenberg, R.F.; Linville, R.M.; Searson, P. Engineering the Human Blood–Brain Barrier at the Capillary Scale using a Double-Templating Technique. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morin, F., et al., Chapter 6 - Biomechanical Modeling of Brain Soft Tissues for Medical Applications, in Biomechanics of Living Organs, Y. Payan and J. Ohayon, Editors. 2017, Academic Press: Oxford. p. 127-146.

- Raub, C.; Putnam, A.; Tromberg, B.; George, S. Predicting bulk mechanical properties of cellularized collagen gels using multiphoton microscopy. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 4657–4665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Zeng, M.; Sun, Y.; Fu, B.M. Quantification of Blood-Brain Barrier Solute Permeability and Brain Transport by Multiphoton Microscopy. J. Biomech. Eng. 2014, 136, 031005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Li, Y.; Fu, B.M. Differential effects of vascular endothelial growth factor on glycocalyx of endothelial and tumor cells and potential targets for tumor metastasis. APL Bioeng. 2022, 6, 016101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Shteyman, D.B.; Hachem, Z.; Ulay, A.A.; Fan, J.; Fu, B.M. Heparan Sulfate Modulation Affects Breast Cancer Cell Adhesion and Transmigration across In Vitro Blood–Brain Barrier. Cells 2024, 13, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Fan, J.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, L.; Fu, B.M. Adhesion of malignant mammary tumor cells MDA-MB-231 to microvessel wall increases microvascular permeability via degradation of endothelial surface glycocalyx. J. Appl. Physiol. 2012, 113, 1141–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A., et al., Collagen-based brain microvasculature model in vitro using three-dimensional printed template. Biomicrofluidics, 2015. 9(2).

- Výborný, K.; Vallová, J.; Kočí, Z.; Kekulová, K.; Jiráková, K.; Jendelová, P.; Hodan, J.; Kubinová, Š. Genipin and EDC crosslinking of extracellular matrix hydrogel derived from human umbilical cord for neural tissue repair. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, S.; Rhim, J.-W. Genipin-Crosslinked Gelatin/Chitosan-Based Functional Films Incorporated with Rosemary Essential Oil and Quercetin. Materials 2022, 15, 3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grifno, G.N.; Farrell, A.M.; Linville, R.M.; Arevalo, D.; Kim, J.H.; Gu, L.; Searson, P.C. Tissue-engineered blood-brain barrier models via directed differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrobak, K.M.; Potter, D.R.; Tien, J. Formation of perfused, functional microvascular tubes in vitro. 2006, 71, 185–196. [CrossRef]

- Gould, I.G., et al., The capillary bed offers the largest hemodynamic resistance to the cortical blood supply. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab, 2017. 37(1): p. 52-68.

- Koutsiaris, A.G.; Tachmitzi, S.V.; Batis, N.; Kotoula, M.G.; Karabatsas, C.H.; Tsironi, E.; Chatzoulis, D.Z. Volume flow and wall shear stress quantification in the human conjunctival capillaries and post-capillary venules in vivo. Biorheology 2007, 44, 375–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santisakultarm, T.P.; Cornelius, N.R.; Nishimura, N.; Schafer, A.I.; Silver, R.T.; Doerschuk, P.C.; Olbricht, W.L.; Schaffer, C.B. In vivo two-photon excited fluorescence microscopy reveals cardiac- and respiration-dependent pulsatile blood flow in cortical blood vessels in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302, H1367–H1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Mirc, D.; Fu, B.M. Mechanical mechanisms of thrombosis in intact bent microvessels of rat mesentery. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 2726–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, P.; Cai, B.; Lei, M.; Liu, Y.; Fu, B.M. Differential arrest and adhesion of tumor cells and microbeads in the microvasculature. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2013, 13, 537–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katt, M.E., et al., Functional brain-specific microvessels from iPSC-derived human brain microvascular endothelial cells: the role of matrix composition on monolayer formation. Fluids Barriers CNS, 2018. 15(1): p. 7.

- Xu, S.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; He, P. Development and Characterization of In Vitro Microvessel Network and Quantitative Measurements of Endothelial [Ca2+]i and Nitric Oxide Production. J. Vis. Exp. 2016, e54014–e54014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, W.-Y.; Cai, B.; Zeng, M.; Tarbell, J.M.; Fu, B.M. Quantification of the endothelial surface glycocalyx on rat and mouse blood vessels. Microvasc. Res. 2012, 83, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Ebong, E.E.; Fu, B.M.; Tarbell, J.M. The Structural Stability of the Endothelial Glycocalyx after Enzymatic Removal of Glycosaminoglycans. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e43168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Fan, J.; Cai, B.; Lv, Y.; Zeng, M.; Hao, Y.; Giancotti, F.G.; Fu, B.M. Vascular endothelial growth factor enhances cancer cell adhesion to microvascular endothelium in vivo. Exp. Physiol. 2010, 95, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, W.; Lv, Y.; Zeng, M.; Fu, B.M. Non-invasive measurement of solute permeability in cerebral microvessels of the rat. Microvasc. Res. 2008, 77, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L., M. Zeng, and B.M. Fu, Temporal effects of vascular endothelial growth factor and 3,5-cyclic monophosphate on blood-brain barrier solute permeability in vivo. J Neurosci Res, 2014. 92(12): p. 1678-89.

- Shin, D.W.; Fan, J.; Luu, E.; Khalid, W.; Xia, Y.; Khadka, N.; Bikson, M.; Fu, B.M. In Vivo Modulation of the Blood–Brain Barrier Permeability by Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS). Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 48, 1256–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutuzov, N., H. Flyvbjerg, and M. Lauritzen, Contributions of the glycocalyx, endothelium, and extravascular compartment to the blood–brain barrier. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 2018. 115(40): p. E9429-E9438.

- Jamieson, J.J., et al., Role of iPSC-derived pericytes on barrier function of iPSC-derived brain microvascular endothelial cells in 2D and 3D. Fluids and Barriers of the CNS, 2019. 16(1): p. 15.

- Helms, H.C.; Abbott, N.J.; Burek, M.; Cecchelli, R.; Couraud, P.-O.; Deli, M.A.; Förster, C.; Galla, H.J.; Romero, I.A.; Shusta, E.V.; et al. In vitro models of the blood–brain barrier: An overview of commonly used brain endothelial cell culture models and guidelines for their use. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2016, 36, 862–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, N.J.; Friedman, A. Overview and introduction: The blood–brain barrier in health and disease. Epilepsia 2012, 53, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, N.J., L. Rönnbäck, and E. Hansson, Astrocyte–endothelial interactions at the blood–brain barrier. Nature reviews neuroscience, 2006. 7(1): p. 41.

- Offeddu, G.S.; Cambria, E.; Shelton, S.E.; Haase, K.; Wan, Z.; Possenti, L.; Nguyen, H.T.; Gillrie, M.R.; Hickman, D.; Knutson, C.G.; et al. Personalized Vascularized Models of Breast Cancer Desmoplasia Reveal Biomechanical Determinants of Drug Delivery to the Tumor. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2402757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Offeddu, G.S.; Hajal, C.; Foley, C.R.; Wan, Z.; Ibrahim, L.; Coughlin, M.F.; Kamm, R.D. The cancer glycocalyx mediates intravascular adhesion and extravasation during metastatic dissemination. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.; Vandormael, R.; De Laere, M.; Pintelon, I.; Berneman, Z.; Watts, R.; Cools, N. A Microfluidic In Vitro Three-Dimensional Dynamic Model of the Blood–Brain Barrier to Study the Transmigration of Immune Cells. Brain Sci. 2022, 12, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achrol, A.S., et al., Brain metastases. Nat Rev Dis Primers, 2019. 5(1): p. 5.

- Fu, Y.; Li, A.; Wu, J.; Kunz, R.F.; Sun, R.; Ding, Z.; Wu, J.; Dong, C. Fibrinogen and Fibrin Differentially Regulate the Local Hydrodynamic Environment in Neutrophil–Tumor Cell–Endothelial Cell Adhesion System. Appl. Sci. 2020, 11, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Julia, C.G., et al., CD44 engagement enhances acute myeloid leukemia cell adhesion to the bone marrow microenvironment by increasing VLA-4 avidity. Haematologica, 2021. 106(8): p. 2102-2113.

- Schnitzer, J.E.; Pinney, E. Quantitation of specific binding of orosomucoid to cultured microvascular endothelium: role in capillary permeability. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 1992, 263, H48–H55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, A.; Malvi, P.; Wajapeyee, N. Heparan Sulfate and Heparan Sulfate Proteoglycans in Cancer Initiation and Progression. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 9, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.C.; AB Multhaupt, H.; Couchman, J.R. Cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans control adhesion and invasion of breast carcinoma cells. Mol. Cancer 2015, 14, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippmann, E.S.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Palecek, S.P.; Shusta, E.V. Modeling the blood–brain barrier using stem cell sources. Fluids Barriers CNS 2013, 10, 2–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stebbins, M.J.; Gastfriend, B.D.; Canfield, S.G.; Lee, M.-S.; Richards, D.; Faubion, M.G.; Li, W.-J.; Daneman, R.; Palecek, S.P.; Shusta, E.V. Human pluripotent stem cell–derived brain pericyte–like cells induce blood-brain barrier properties. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campisi, M.; Shin, Y.; Osaki, T.; Hajal, C.; Chiono, V.; Kamm, R.D. 3D self-organized microvascular model of the human blood-brain barrier with endothelial cells, pericytes and astrocytes. Biomaterials 2018, 180, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippmann, E.S.; Azarin, S.M.; Kay, J.E.; Nessler, R.A.; Wilson, H.K.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Palecek, S.P.; Shusta, E.V. Derivation of blood-brain barrier endothelial cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weksler, B.; A Romero, I.; Couraud, P.-O. The hCMEC/D3 cell line as a model of the human blood brain barrier. Fluids Barriers CNS 2013, 10, 16–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, B.P.; Cruz-Orengo, L.; Pasieka, T.J.; Couraud, P.-O.; Romero, I.A.; Weksler, B.; Cooper, J.A.; Doering, T.L.; Klein, R.S. Immortalized human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells maintain the properties of primary cells in an in vitro model of immune migration across the blood brain barrier. J. Neurosci. Methods 2012, 212, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).