Submitted:

07 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

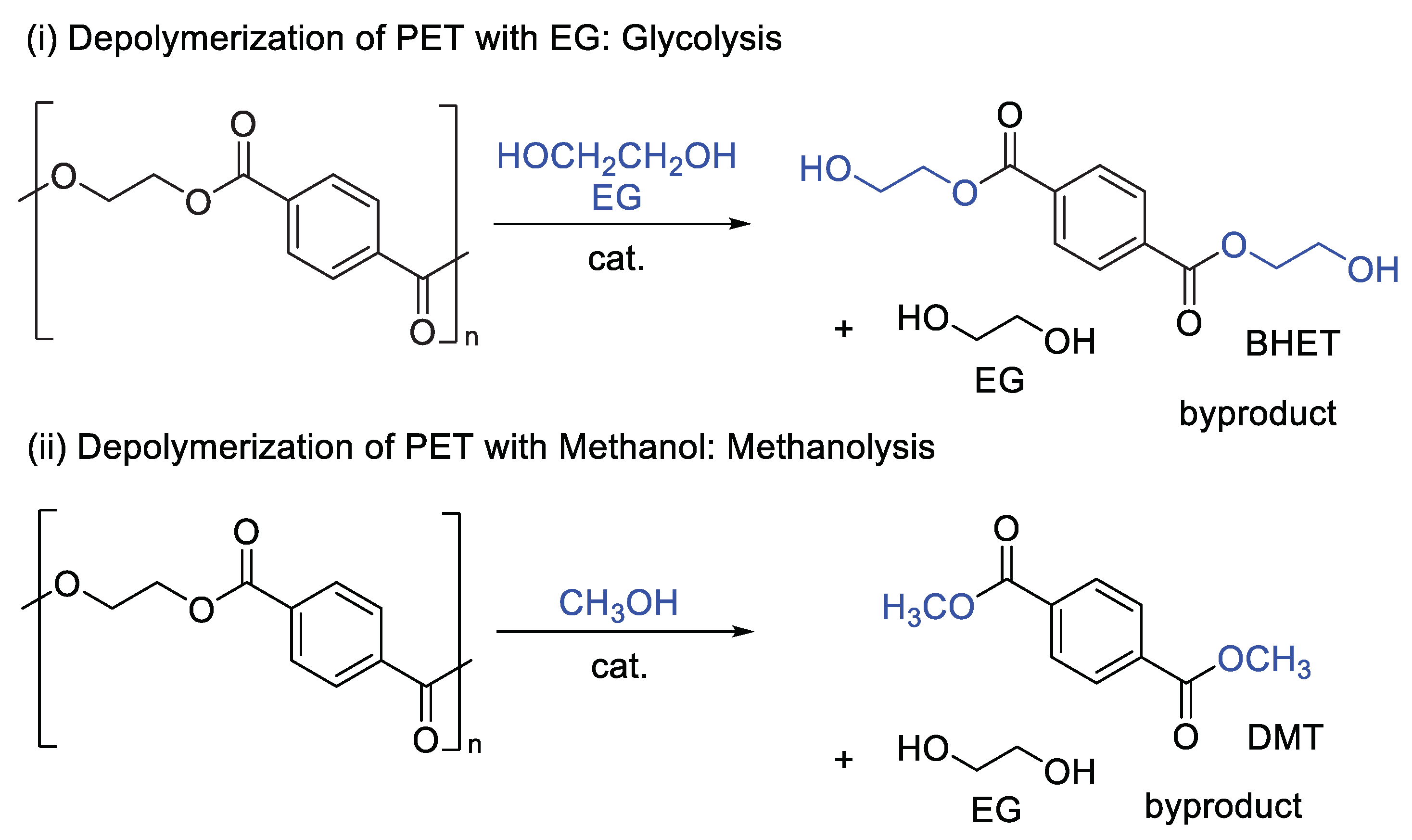

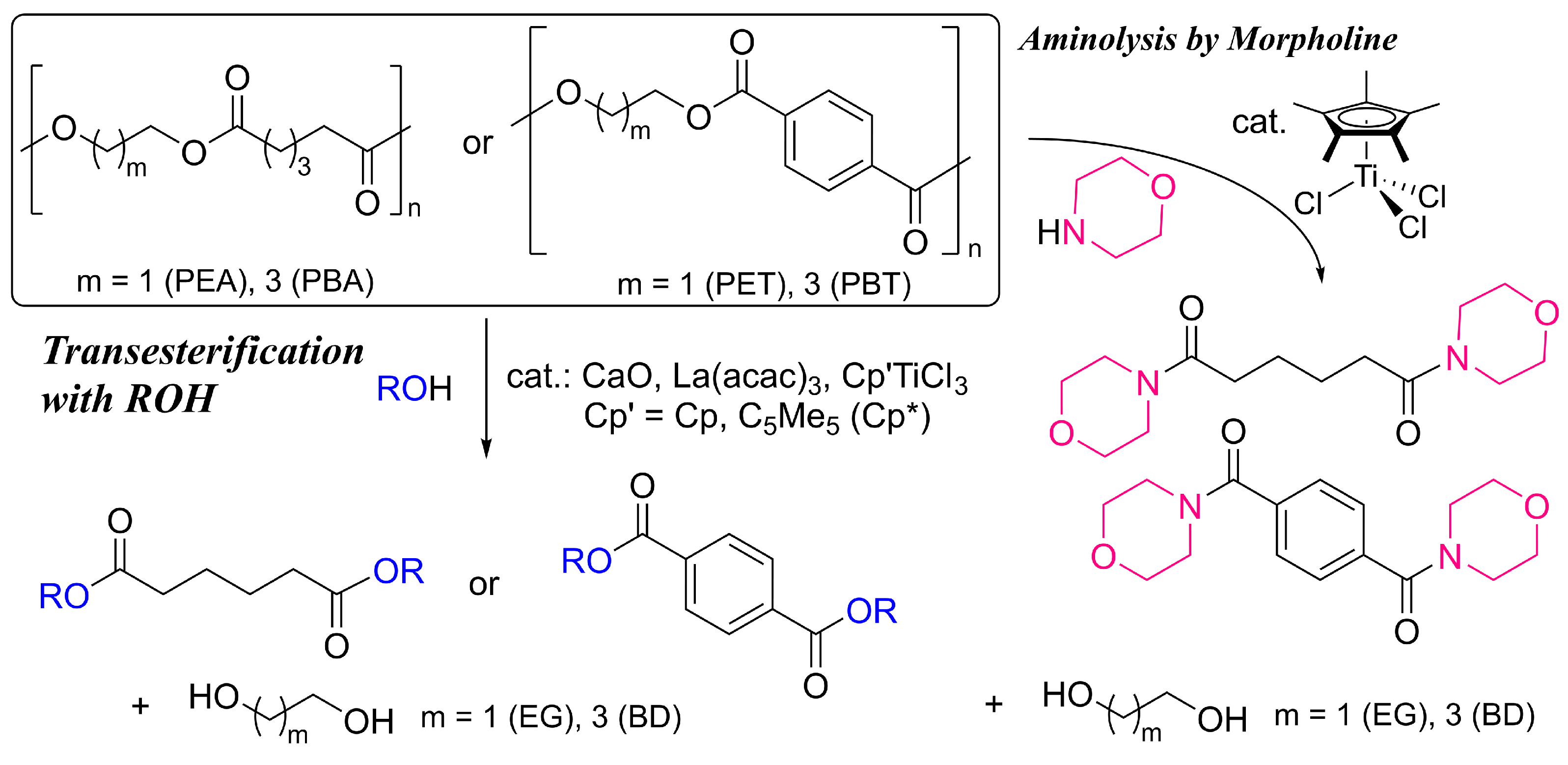

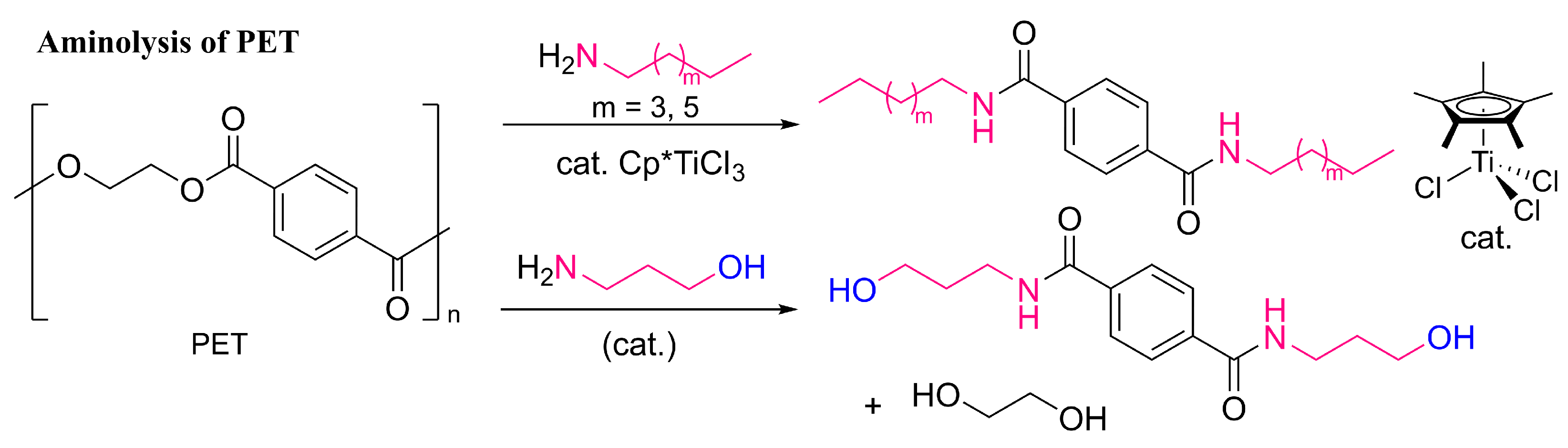

1. Introduction

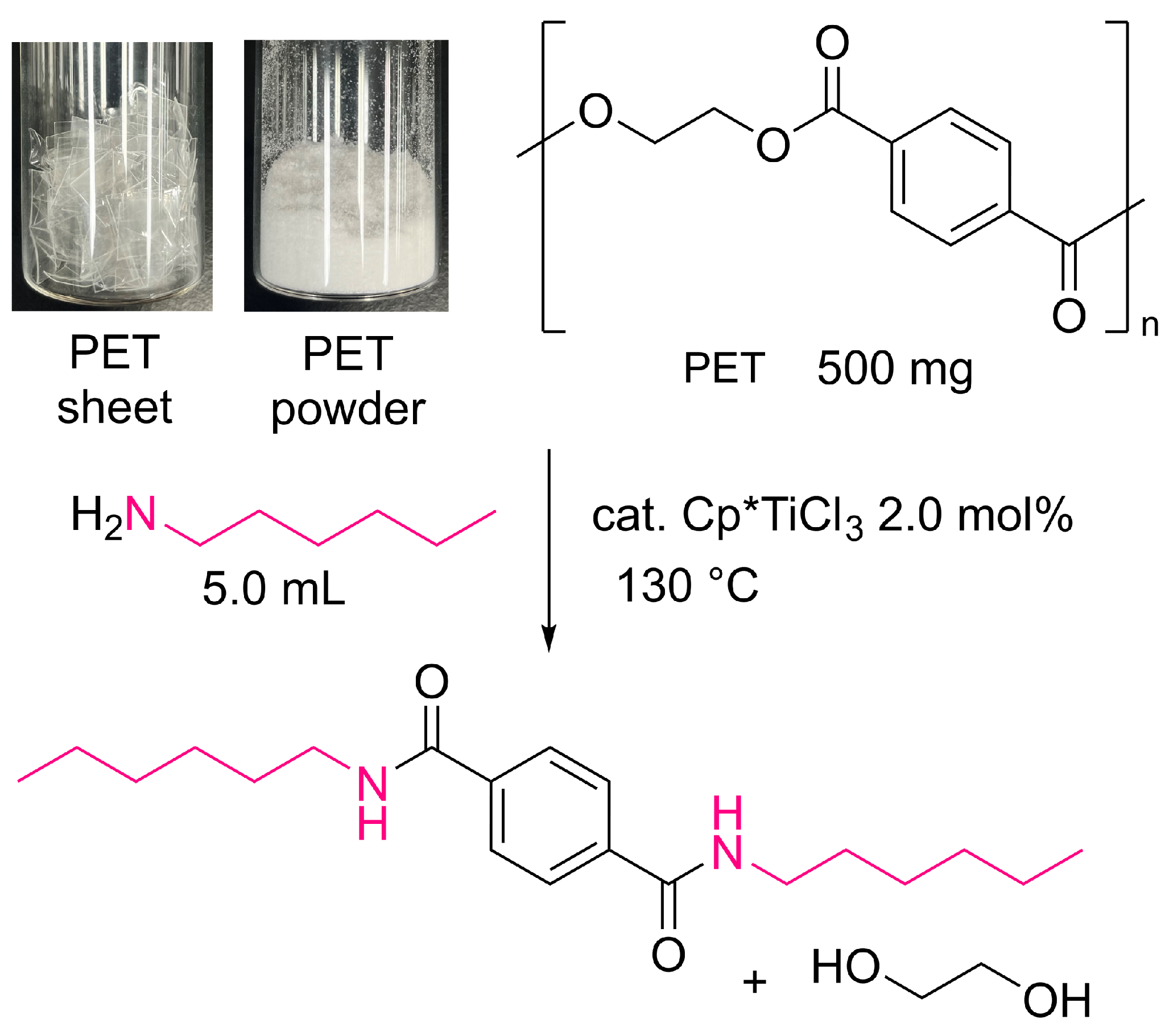

2. Results and Discussion

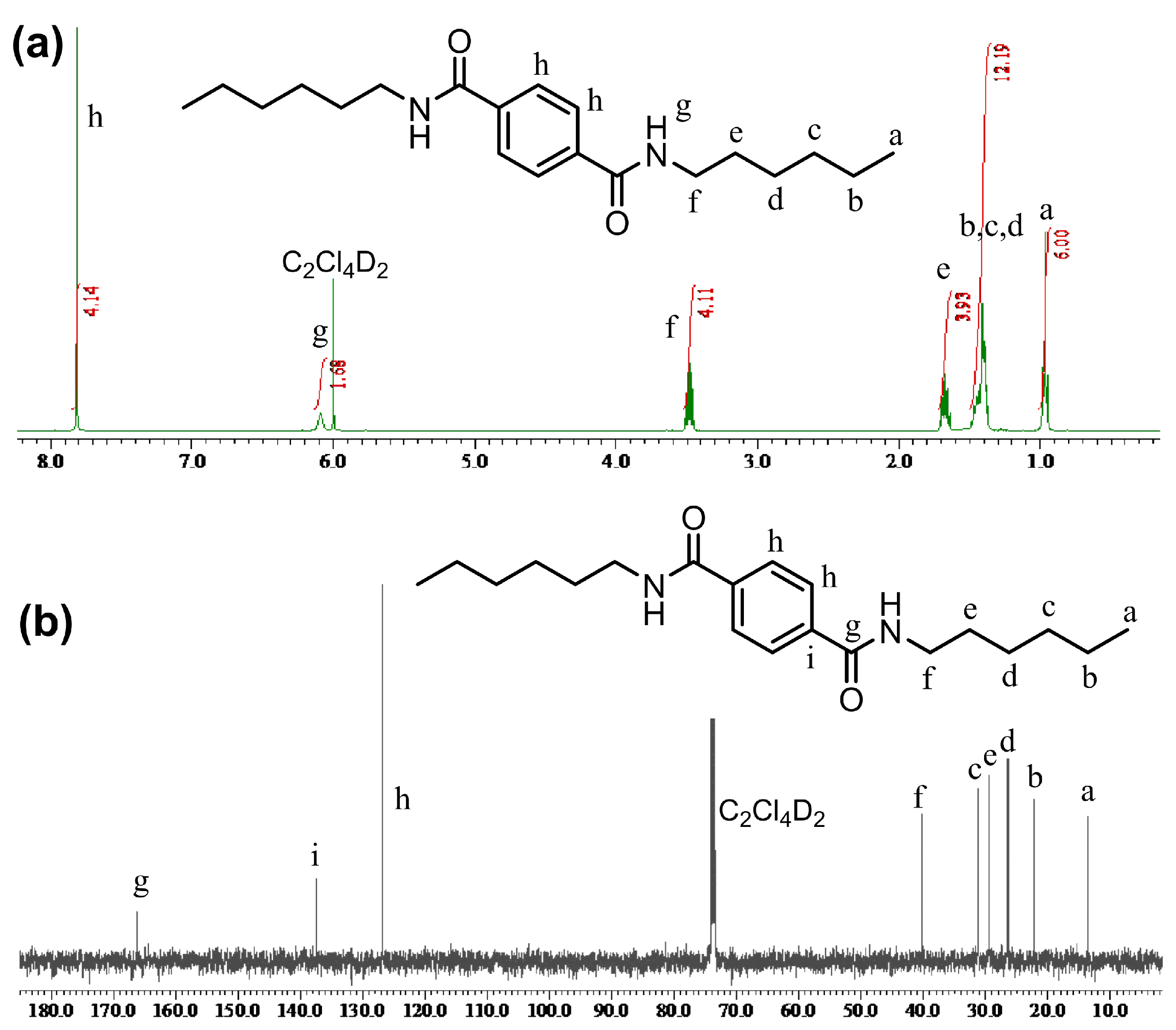

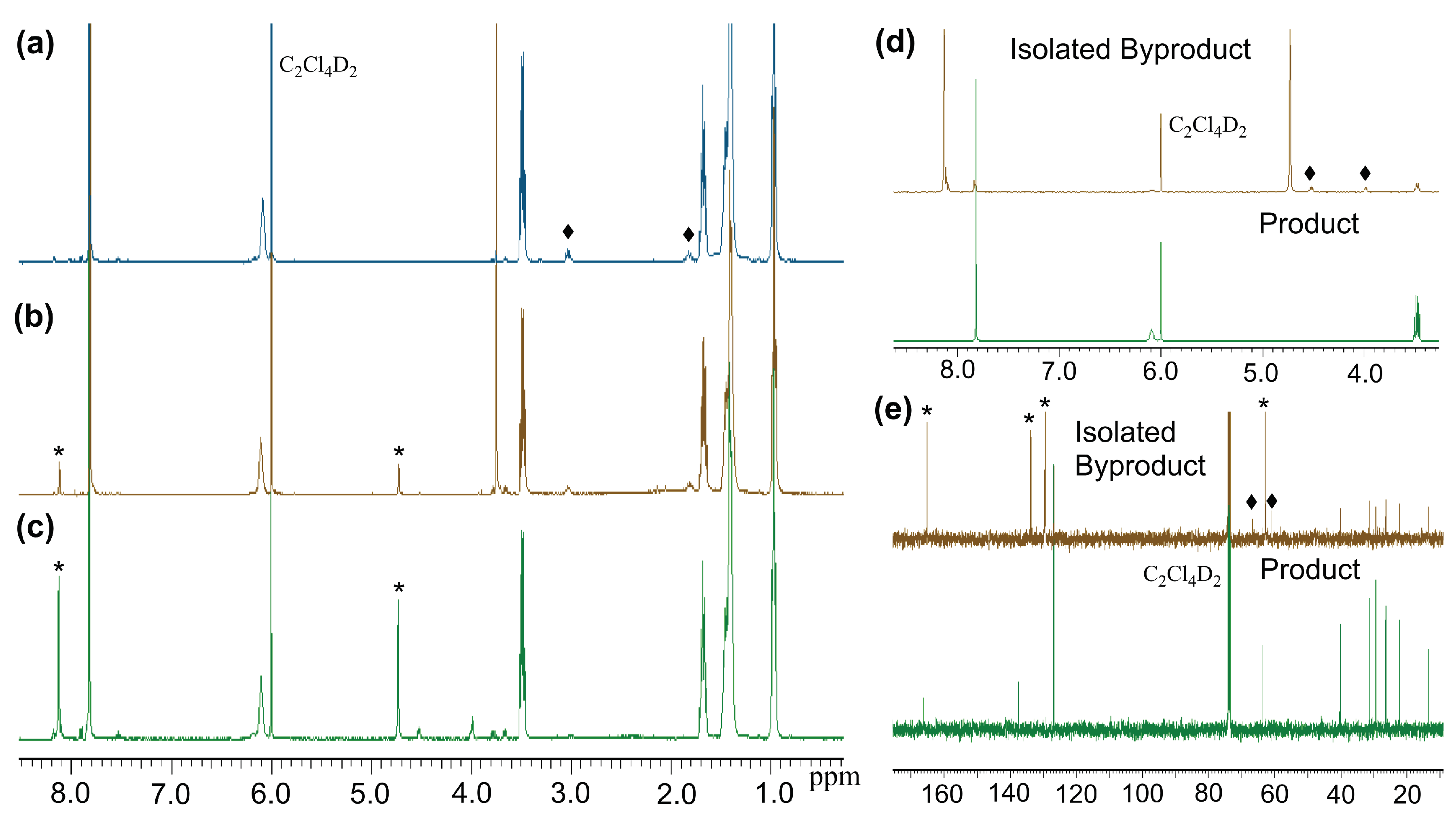

2.1. Reactions of PET with n-Hexylamine, n-Octylamine

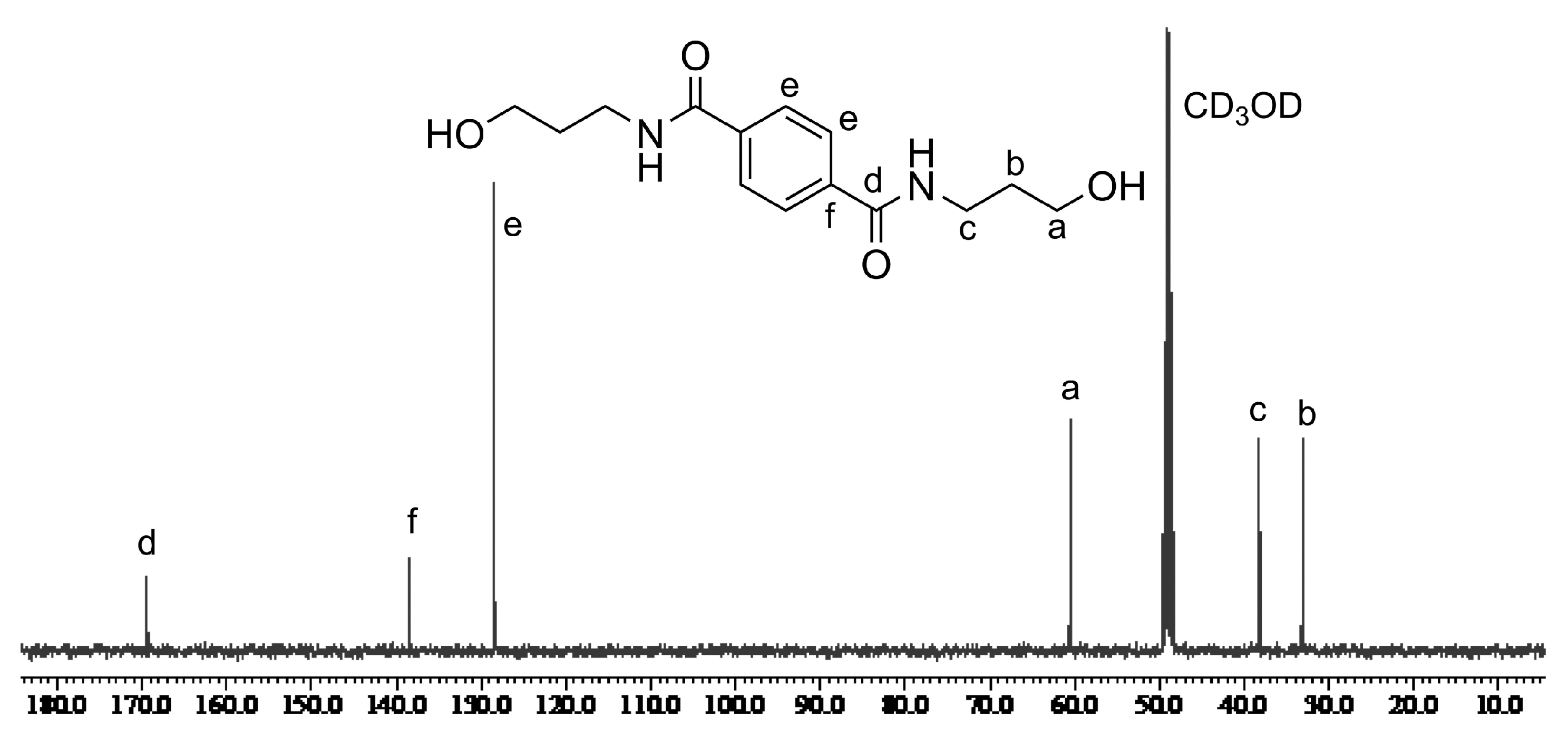

2.2. Reaction of PET with 3-Amino-1-Propanol

3. Materials and Methods

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coates, G.W.; Getzler, Y.D.Y.L. Chemical recycling to monomer for an ideal, circular polymer economy. Nat. Rev. Mat. 2020, 5, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collias, D.I.; James, M.I.; Layman, J.M. (Eds.) Circular Economy of Polymers: Topics in Recycling Technologies; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Worch, J.C.; Dove, A.P. 100th Anniversary of macromolecular science viewpoint: Toward catalytic chemical recycling of waste (and future) plastics. ACS Macro Lett. 2020, 9, 1494–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, M.; Liu, Y.; Lou, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J. Rational design of chemical catalysis for plastic recycling. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 4659–4679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fevre, M.; Jones, G.O.; Waymouth, R.M. Catalysis as an enabling science for sustainable polymers. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 839–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westhues, S.; Idel, J.; Klankermayer, J. Molecular catalyst systems as key enablers for tailored polyesters and polycarbonate recycling concepts. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4, eaat966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basterretxea, A.; Jehanno, C.; Mecerreyes, D.; Sardon, H. Dual organocatalysts based on ionic mixtures of acids and bases: A step toward high temperature polymerizations. ACS Macro Lett. 2019, 8, 1055–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.; Jones, M.D. The chemical recycling of polyesters for a circular plastics economy: Challenges and emerging opportunities. ChemSusChem. 2021, 14, 4041–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Häußler, M.; Eck, M.; Rothauer, D.; Mecking, S. Closed-loop recycling of polyethylene-like materials. Nature 2021, 590, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.D.; James, M.I. Chemical Recycling of PET. In Circular Economy of Polymers: Topics in Recycling Technologies; Collias, D.I., James, M.I., Layman, J.M., Eds.; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Paszun, D.; Spychaj, T. Chemical recycling of poly(ethylene terephthalate). Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1997, 36, 1373–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damayanti; Wu, H.S. Strategic possibility routes of recycled PET. Polymers 2021, 13, 1475. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeeley, A.; Liu, Y. A. Assessment of PET depolymerization processes for circular economy. 1. Thermodynamics, chemistry, purification, and process design. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 3355–3399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanno, C.; Pérez-Madrigal, M. M.; Demarteau, J.; Sardon, H.; Dove, A. P. Organocatalysis for depolymerization. Polym. Chem. 2019, 10, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Dios Caputto, M. D.; Navarro, R.; Valentín, J. L.; Marcos-Fernández, Á. Chemical upcycling of poly(ethylene terephthalate) waste: Moving to a circular model. J. Polym. Sci. 2022, 60, 3269–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, L.A.; Gupta, V.P. Degradative transesterification of terephthalate polyesters to obtain DOTP plasticizer for flexible PVC. J. Vinyl. Technol. 1993, 15, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.-W.; Chen, L.-W. The glycolysis of poly(ethylene terephthalate). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1999, 73, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lo, Y.-W.; Mao, C.-F.; Liao, W.-T. Studies of glycolysis of poly(ethylene terephthalate) recycled from postconsumer soft-drink bottles. I. Influences of glycolysis conditions. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 80, 943–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, S.H.; Ikladious, N.E. Depolymerization of poly(ethylene terephthalate) wastes using 1,4-butanediol and triethylene glycol. Polym. Test. 2002, 21, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurokawa, H.; Ohshima, M.; Sugiyama, K.; Miura, H. Methanolysis of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) in the presence of aluminium tiisopropoxide catalyst to form dimethyl terephthalate and ethylene glycol. Polym. Degrad. Satbil. 2003, 79, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troev, K.; Grancharov, G.; Tsevi, R.; Gitsov, I. A novel catalyst for the glycolysis of poly (ethylene terephthalate). J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 90, 1148–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fonseca, R.; Duque-Ingunza, I.; de Rivas, B.; Arnaiz, S.; Gutiérrez-Ortiz, J.I. Chemical recycling of post-consumer PET wastes by glycolysis in the presence of metal salts. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2010, 95, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, K.; Coulembier, O.; Lecuyer, J.M.; Almegren, H.A.; Alabdulrahman, A.M.; Alsewailem, F.D.; Mcneil, M.A.; Dubois, P.; Waymouth, R.M.; Horn, H.W.; et al. Organocatalytic depolymerization of poly(ethylene terephthalate). J. Polym. Sci., Part A Polym. Chem. 2011, 49, 1273–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukushima, K.; Coady, D.J.; Jones, G.O.; Almegren, H.A.; Alabdulrahman, A.M.; Alsewailem, F.D.; Horn, H.W.; Rice, J.E.; Hedrick, J.L. Unexpected efficiency of cyclic amidine catalysts in depolymerizing poly(ethylene terephthalate). J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym.Chem. 2013, 51, 1606–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Kim, D.H.; Al-Masry, W.A.; Mahmood, A.; Hassan, A.; Haider, S.; Ramay, S.M. Manganese-, cobalt-, and zinc-based mixed-oxide spinels as novel catalysts for the chemical recycling of poly(ethylene terephthalate) via glycolysis. Polym. Degrad. Satbil. 2013, 98, 904–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.W.; Wang, Z.P.; Li, L.; Yu, S.T.; Xie, C.X.; Liu, F.S. Butanol alcoholysis reaction of polyethylene terephthalate using acidic ionic liquid as catalyst. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013, 130, 1840–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Fu, W.; Lu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, S. Lewis acid–base synergistic catalysis for polyethylene terephthalate degradation by 1,3-Dimethylurea/Zn(OAc)2 deep eutectic solvent. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 7, 3292–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Geng, Y.; Lu, X.; Zhang, S. First-row transition metal-containing ionic liquids as highly active catalysts for the glycolysis of poly(ethylene terephthalate) (PET). ACS Sustai. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Fu, W.; Lu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, S. Lewis acid–base synergistic catalysis for polyethylene terephthalate degradation by 1,3-dimethylurea/Zn(OAc)2 deep eutectic solvent. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 3292–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehanno, C.; Demarteau, J.; Mantione, D.; Arno, M. C.; Ruipérez, F.; Hedrick, J. L.; Dove, A. P.; Sardon, H. Selective chemical upcycling of mixed plastics guided by a thermally stable organocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 6710–6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaiho, S.; Hmayed, A. A. R.; Chiaie, K. R. D.; Worch, J. C.; Dove, A.P. Designing thermally stable organocatalysts for poly(ethylene terephthalate) synthesis: Toward a one-pot, closed-loop chemical recycling system for PET. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 10628–10639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaie, K. R. D.; McMahon, F. R.; Williams, E. J.; Price, M. J.; Dove, A. P. Dual-catalytic depolymerization of polyethylene terephthalate (PET). Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 1450–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rollo, M.; Raffi, F.; Rossi, E.; Tiecco, M.; Martinell, E.; Ciancaleoni, G. Depolymerization of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) under mild conditions by Lewis/Brønsted acidic deep eutectic solvents. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 456, 141092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Dios Caputto, M. D.; Navarro, R.; Valentín, J. L.; Marcos-Fernandez, A. Tuning of molecular weight and chemical composition of polyols obtained from poly(ethylene terephthalate) waste recycling through the application of organocatalysts in an upcycling route. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 454, 142253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.-T.; Sun, Q.; Zeng, X.-F.; Wang, D.; Wang, J.-X.; Chen, J.-F. ZnO Nanodispersion as pseudohomogeneous catalyst for alcoholysis of polyethylene terephthalate. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2020, 220, 115642–115651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.D.; Cho, J. Low-energy catalytic methanolysis of poly(ethylene terephthalate). Green Chem. 2021, 23, 511–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirazimoghaddam, S.; Amin, I.; Faria Albanese, J. A.; Shiju, N. R. Chemical recycling of used PET by glycolysis using niobia-based catalysts. ACS Eng. Au, 2023, 3, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, S.; Sato, J.; Nakajima, Y. Capturing ethylene glycol with dimethyl carbonate towards depolymerisation of polyethylene terephthalate at ambient temperature. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 9412–9416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Koga, M.; Kuragano, T.; Ogawa, A.; Ogiwara, H.; Sato, K.; Nakajima, Y. Depolymerization of polyester fibers with dimethyl carbonate-aided methanolysis. ACS Mater. Au 2024, 4, 335–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abe, R.; Komine, N.; Nomura, K.; Hirano, M. La(iii)-Catalysed degradation of polyesters to monomers via transesterifications. Chem. Commun. 2022, 58, 8141–8144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohki, Y.; Ogiwara, Y.; Nomura, K. Depolymerization of polyesters by transesterification with ethanol using (cyclopentadienyl)titanium trichlorides. Catalysts 2023, 13, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruean, P.; Padungros, P.; Nomura, K. , Kitiyanan, B. Efficient chemical depolymerization of polyethylene terephthalate via transesterification with ethanol using CaO catalyst. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024, 26, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Yang, J.; Deng, C.; Deng, J.; Shen, L.; Fu, Y. Acetolysis of waste polyethylene terephthalate for upcycling and life-cycle assessment study, Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3249. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, K.; Aoki, T.; Ohki, Y.; Kikkawa, S.; Yamazoe, S. Transesterification of methyl-10-undecenoate and poly(ethylene adipate) catalyzed by (cyclopentadienyl)titanium trichlorides as model chemical conversions of plant oils and acid-, base-free chemical recycling of aliphatic polyesters. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 12504–12509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakaran, S.; Siddiki, S.M.A.H.; Kitiyanan, B.; Nomura, K. CaO catalyzed transesterification of ethyl 10-undecenoate as a model reaction for efficient conversion of plant oils and their application to depolymerization of aliphatic polyesters. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 12864–12872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, N.; Komine, N.; Nomura, K.; Hirano, H.; Hirano, M. La(III)-catalyzed depolymerization of poly(l-lactic acid) yielding chiral lactates. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn., 2023, 96, 1324–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awang, N. W. B.; Hadiyono, M. A. B. R.; Abdellatif, M. M.; Nomura, K. Depolymerization of PET with ethanol by homogeneous iron catalysts applied for exclusive chemical recycling of cloth waste. Ind. Chem Mat. 2024, web released on August 6. [CrossRef]

- Ogiwara, Y.; Nomura, K. Chemical upcycling of PET into a morpholine amide as a versatile synthetic building block. ACS Org. Inorg. Au 2023, 6, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bepari, M. R.; Sullivan, L. R.; O’Harra, K. E.; Barbosa, G. D.; Turner, C. H.; Bara, J. E. Depolymerizing polyethylene terephthalate (PET) via “imidazolysis” for obtaining a diverse array of intermediates from plastic waste. ACS Applied Polymer Materials 2024, 6, 7886–7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| run | PET2 | cat. | temp. | time | yield3 | |

| / mol% | / ºC | / h | / mg | / % | ||

| 1 | sheet | 2.0 | 130 | 48 | 786 | 91 |

| 2 | powder | 2.0 | 130 | 48 | 820 | 95 |

| 3 | sheet | 2.0 | 130 | 16 | 789 | 91 |

| 4 | powder | 2.0 | 130 | 16 | 794 | 92 |

| 5 | sheet | 2.0 | 130 | 6 | 766 | 89 |

| 6 | powder | 2.0 | 130 | 6 | 732 | 85 |

| 7 | powder | 0 | 130 | 6 | 714 | 83 |

| 8 | powder | 2.0 | 100 | 6 | 408 | 47 |

| 9 | powder | 5.0 | 100 | 6 | 498 | 58 |

| run | PET2 | cat. | temp. | time | yield3 | |

| / mol% | / ºC | / h | / mg | / % | ||

| 10 | sheet | 2.0 | 130 | 48 | 935 | 93 |

| 11 | powder | 2.0 | 130 | 48 | 929 | 92 |

| 12 | powder | 2.0 | 130 | 16 | 904 | 90* |

| 13 | powder | 2.0 | 130 | 6 | 694 | 69 |

| run | cat. | temp. | time | yield2 | |

| / mol% | / ºC | / h | / mg | / % | |

| 14 | 2.0 | 130 | 24 | 616 | 84 |

| 15 | 2.0 | 100 | 24 | 646 | 89 |

| 16 | 2.0 | 100 | 6 | 662 | 91 |

| 17 | 2.0 | 100 | 3 | 645 | 88 |

| 18 | 2.0 | 80 | 6 | 528 | 72* |

| 19 | 0 | 100 | 24 | 660 | 91 |

| 20 | 0 | 100 | 6 | 660 | 91 |

| 21 | 0 | 100 | 3 | 644 | 88 |

| 22 | 0 | 80 | 6 | 516 | 71* |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).