Submitted:

13 February 2025

Posted:

17 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Lipids

2.1. Experimental

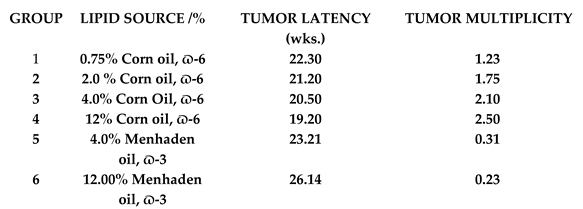

|

- Increasing levels of dietary omega-6 FA exacerbate UVR-carcinogenesis, both with respect to shorter tumor latent period and greater tumor multiplicity.

- Hydrogenation of the EFA, LA, decreases the level of exacerbation of UVR-carcinogenesis, apparently by lowering the level of LA.

- Dietary omega-3 FA markedly inhibit UVR-carcinogenesis.

- Plasma levels of PGE2, a cyclooxygenase intermediate and pro-inflammatory prostaglandin, increase in near linear fashion with increasing levels of omega-6 FA. Dietary omega -3 FA dramatically reduce PGE2 levels.

- High levels of omega-6 FA enhance cutaneous inflammatory response and suppress immune responses.

- Omega-6 FA exert its primary effect on UVR-carcinogenesis in the post-initiation, or promotion/progression stage of the carcinogenic continuum, whereas omega-3 FA exerts its primary effect during initiation, and across the carcinogenic continuum.

2.2. Clinical Studies

2.2.1. Dietary Fat Level

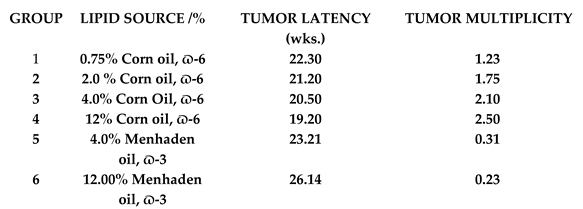

| Treatment | No. | BCC: SCC | NMSC/Patient* | Patients with MSC* | Improvement** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 58 | 0.26 | 9 | 9 9 NS | |

| 52:1 | P>0.01 | P>0.02 | |||

| Intervention | 57 | 0.02 | 1 |

9 1P>0.05 9 1P>0.05

|

- (1)

- The study involved only post-menopausal women as compared to both genders in the Intervention trial.

- (2)

- It relied on the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) to assess dietary intake. Participants were assessed at baseline and at one year and thereafter 33% of participants were assessed each year. On this basis, each participant completed a FFQ every three years. Dietary recall over such long assessment periods is notoriously inaccurate. The intervention trial dietary assessment in the intervention trial were compiled from 7-day food records and verified by a dietician.

- (3)

- Participants self-reported medical outcomes by completing questionnaires every six months. All participants in the intervention trial were assessed every four months by dermatologists.

- (4)

- Perhaps more importantly, pertaining to the null result, was the failure to reduce the fat level to the 20% target. The study reported a long-term difference (eight years) in the percentage of energy from total fat, versus the comparison group, of 8.1 %. The intervention trial reported a 47% reduction at month four that was maintained through month 24.

2.2.2. Type of Dietary Fat

- A direct link exists between PUFA intake and degree of unsaturation and susceptibility to BCC.

- Omega-3 FA supplementation significantly increases the erythema threshold to UVR.

- Omega-3 FA modulate a number of cytokines (in human cells in vitro) and eicosanoids that mediate inflammatory and immune responses.

- Omega-3 FA inhibit certain genotoxic markers of UVR-induced DNA damage, e.g., UVR- induced cutaneous p53.

- Omega-3 FA abrogate UVR-induced immunosuppression of cell mediated immunity assessed as nickel CHS

- Omega-3 FA reduce the risk of SCC and BCC in organ transplant patients.

3. Antioxidants

3.1. Experimental

- BHT dramatically inhibits UVR-carcinogenesis, both in regard to tumor latency period and tumor multiplicity and reduces the severity of those tumors that do develop.

- Inhibition of carcinogenesis occurs through a mechanism of dose diminution by altering the chemical characteristics of the stratum corneum.

- BHT provides marked systemic protection against UVR-mediated erythema in hairless mice. BHT also provides statistically significant protection when administered topically.

- BHT inhibits the UVR induction of ODC

- Several structurally related phenols were evaluated for anti-UVR-carcinogenesis, but only BHT conveyed significant inhibition of both tumor latency and tumor multiplicity.

- BHT supplementation may predispose the host to chemical carcinogenesis by inducing hepatic phase I and II microsomal detoxification/activation enzymes.

- Clinical Relevance:

- Human data is scarce and assessments of BHT and human risk have found that BHT levels in food stuff pose no risk and may even lower the carcinogenic risk. There appears to be no risk involved in the levels of BHT used in cosmetics.

- However, in view of experimental studies of BHT’s promotion or induction of carcinogenesis at various organ sites and the capacity to induce activation of pro-carcinogens, and potential endocrine disrupters, the intake of BHT should be approached with caution [95].

3.1.2. Polyphenols

- (1)

- Anthocyanins

- (2)

- Phenolic acids:

- (3)

- Vitamins C and E:

- effects of Anthocyanins have been demonstrated in human HaCaT keratinocyte cells and skin of SKH-1 mice.

- The treatment of highly malignant B16-F-10 melanoma cells with berry extracts (containing anthocyanins) reduced cell proliferation by one-third and inhibited the metastasis of these cells in vivo.

- Among the polyphenols, anthocyanins have shown several anti-tumor effects, e.g., antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-mutagenic, inhibiting proliferation through modulation of signal transduction pathways, inducing cell cycle arrest and stimulating apoptosis, and anti-metastasis.

- Photoprotective effects have been shown for phenolic acids, including Epigallocatechin (EGCG), quercetin, ellagic, and gallic acids, – all strong antioxidants and anti-tumor agents and constituents of green tea (GT) catechins.

- ECGC protects against UVR-induced suppression of Contact Hypersensitivity.

- Topical application of EGCG significantly reduced (by two thirds) the incidence of UVR-induced skin cancer.

- GT, when fed in drinking water, afforded significant protection against UVR-induced skin carcinogenesis through a mechanism distinct from inhibition of photo-immunosuppression.

- Resveratrol, a stilbene with antioxidant properties, has shown promise as an anti-cancer agent. It affects all carcinogenic stages, i.e., initiation, promotion, progression and induces apoptosis.

- Resveratrol provides strong protective effects against UVR-mediated skin carcinogenesis.

- Curcumin, a polyphenol found in turmeric, inhibits UVR-carcinogenesis whether administered systemically or topically.

- Gallic acid inhibits two-stage chemically induced carcinogenesis in skin and inhibits SCC through targeting heat shock protein that represses metastasis and invasion.

- Ferulic acid inhibits UVR-induced cytotoxicity, apoptosis, and cyclobutene pyrimidine dimer formation in human HaCaT human keratinocytes.

- Systemically or topically administered Ferulic acid to chronically UVR exposed mice resulted in reduced tumor volume and weight.

- Vitamin C, at very high doses, resulted in significant decreases in papilloma and SCC in UVR-radiated mice, as well as a delay in onset of malignant lesions.

- Topical application of vitamin E inhibits UVR-induced skin cancer formation and immunosuppression.

- High concentrations of the nonesterified, optimal isomers of vitamin C and E, applied topically, resulted in significant inhibition of acute erythema and tanning as well as chronic UVR-mediated aging and skin cancer.

- N—Acetylcysteine (NAC), alone, or in combination with vitamin C, modulates UVR-induced skin tumors in mice.

- NAC supplementation increases melanoma metastasis in animals – a consequence of the differential role that OS plays in the early and late stages of cancer.

- Glycine added to NAC (GlyNAC) supplements improved glutathione synthesis and reduced OS.

- Carbon 60 (C60) is a powerful antioxidant (100 to 1000-fold greater antioxidant capacity than other antioxidants), provides protective effects against UVA radiation injuries, suppresses superoxide radical formation, and suppresses apoptosis.

- Clinical relevance:

- Epidemiological and clinical studies of GT polyphenols have reported varying responses with regard to cancer incidence, with some studies showing an inverse relationship and some reporting increased risks.

- Resveratrol has shown promise as an anti-cancer agent. It affects all carcinogenic stages.

- Resveratrol is target-site specific and clinical trials have been ambiguous. Some trials have reported detrimental effects. Caution is advised when supplements are taken for chemoprevention.

- Most observational studies examining vitamin C intake in relation to cancer incidence have found no association.

- Randomized controlled trials have reported no effect of vitamin C supplementation on cancer risk.

- High vitamin C intake has been associated with increased cardiovascular disease mortality in diabetic postmenopausal women.

- High dose, intravenous vitamin C infusions have doubled overall survival of pancreatic patients when used as co-therapy with gemcitabine + nab-paclitaxel.

- Vitamin E has been shown to significantly reduce malondialdehyde levels but does not affect other measures of OS in human skin.

- Conflicting reports of benefits and risks of antioxidant supplementation has led the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research to conclude “A general recommendation to consume supplements for cancer prevention might have unexpected adverse effects” and thus, “Dietary supplements are not recommended for cancer prevention.”

4. Carotenoids

- (a)

- Conclusions from Experimental Studies:

- ∙

- Phytoene protects against sunburn in guinea pig skin.

- ∙

- Eary studies, in which animals were fed closed-formula rations, ß-carotene, canthaxanthin and phytoene were shown to have anti-tumor activity.

- ∙

- Later studies, employing a semi-defined ration, ß-carotene was found to exacerbate UVR-carcinogenesis.

- ∙

- Differences between the two responses to UVR was found to be diet related.

- ∙

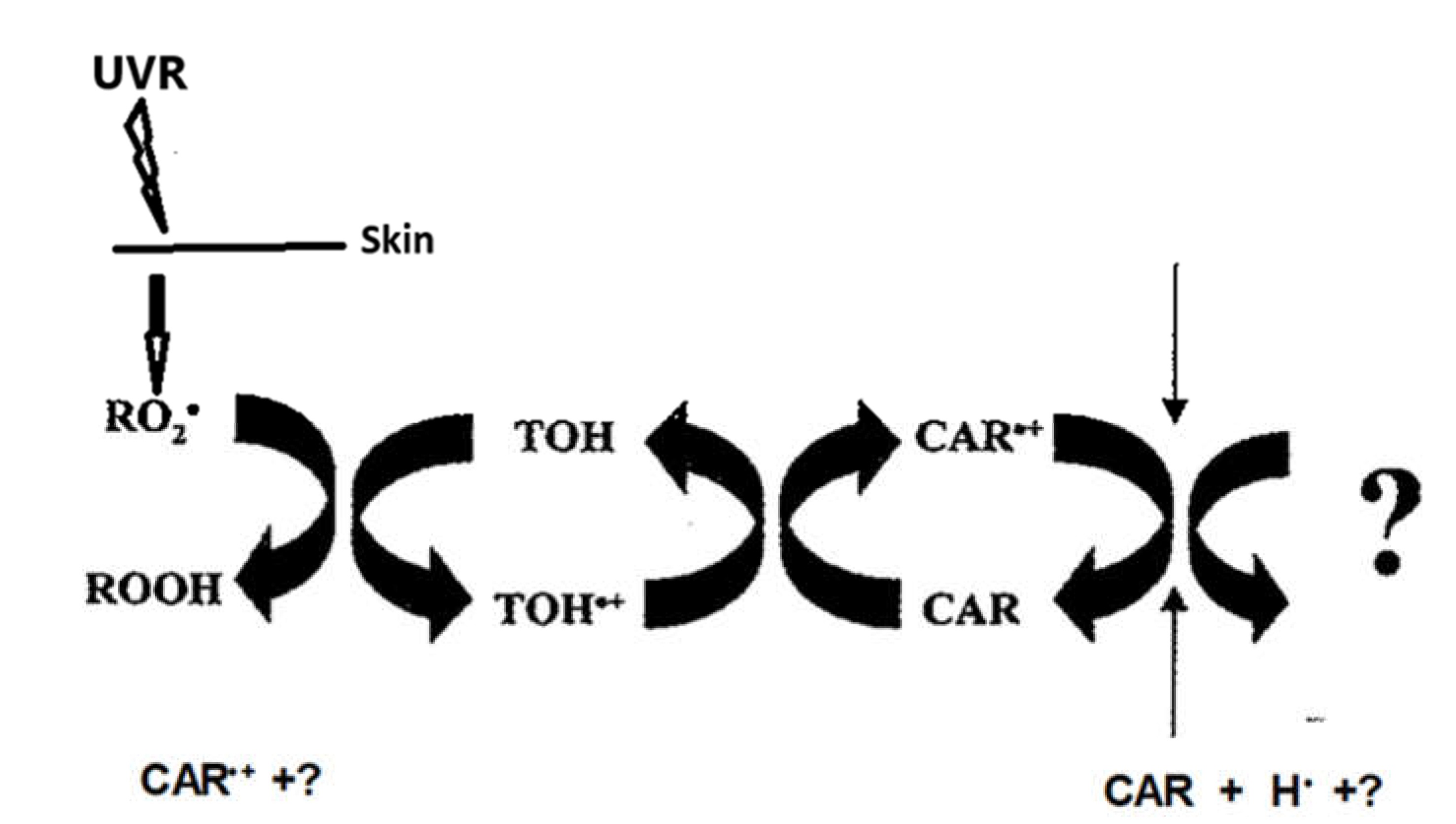

- Based upon one electron rate constants between ß-carotene, vitamins E and C, ß-carotene is highly reactive with peroxyl radicals that result with the formation of a carotenoid radical cation (this radical is a strong oxidizing agent, itself) that is repaired by vitamin E to form a vitamin E radical cation that would be repaired by vitamin C to form the vitamin C radical cation. The vitamin C radical cation would either be cleared or repaired by some other phytochemical found in closed-formular rations, but not in semi-defined diets. It also must be remembered that mice synthesize their own vitamin C, unlike humans who must have a dietary source. When vitamin C was either eliminated from the semi-defined diet or increased 6-fold, ß-carotene exacerbation of UVR carcinogenesis was not affected. Nor did 10-fold increases in vitamin E affect exacerbation. However, when vitamin E levels were reduced, there was augmentation of ß-carotene exacerbation of UVR carcinogenesis. These data do not support a role for vitamin C in ß-carotene radical cation repair but do suggest a vitamin E and ß-carotene interaction.

- ∙

- Astaxanthin has been shown to significantly decrease tumor size in a xenograft model and has potent in vivo and in vitro inhibiting effects on melanoma tumor growth and metastasis (cell migration).

- (b)

- Clinical Relevance:

- ∙

- Epidemiological studies have provided persuasive evidence for an association for cancer-preventive effects with ß-carotene.

- ∙

- ß-carotene modestly protects against UVA and UVB -induced erythema.

- ∙

- A controlled clinical trial found that ß-carotene supplementation had no effect on BCC or SCC occurrence.

- ∙

- A randomized trial in Australia found that ß-carotene did not significantly affect the incidence of BCC or SCC over a four-year period, although an increase in SCC (1508 vs 1145/100,000) was observed.

- ∙

- Three case-controlled studies found no association between blood carotenoid levels and risk of melanoma.

- ∙

- A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found that ß-carotene had no effect on the incidence of melanoma.

- ∙

- The ATBC trial reported that an 18% increase in the incidence of lung cancer in male smokers administered 20mg/day of ß-carotene occurred.

- ∙

- The CARET trial found that patients administered 30 mg/day of ß-carotene plus 25,000 IU of retinol was associated with an increased incidence of lung cancer among the cohort of 18, 314.

- ∙

- The IARC recommended that ß-carotene should not be used in cancer prevention until further insight is gained. Nor should it be assumed that ß-carotene is responsible for the cancer-protecting effects of diets rich in carotenoid containing fruits and vegetables.

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F. ; Laversanne, M,; Sung, H.; et al.: Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2: 74(3). [CrossRef]

- Siege, l R. L.; Miller, K. D., Ed.; Fuchs H.E.; Jemal, A.: Cancer Statistics, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemal, A, Torre, L, Soerjomataram I, Bray F (Eds). The Cancer Atlas. Third Ed. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society, 2019.: http://www.cancer.

- Urban, K. ; Mehrmal, S, Uppal, P.; et. al.: The global burden of skin cancer: A longitudinal analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study, 1990-2017. JAAD Int, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, Hinckley MR, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB, Coldiron BM. Arch Dermatol. 2010, Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006;146(3):283-287.

- Cancer Facts and Figures, 2024. Cancer.org/research/cancer/facts-statistics/all-cancer-facts-figures.

- Collins, KK. : The diabetes-cancer link. 2014, Diabetes Spectrum, 27: 276-280.

- Black, HS: Oxidative Stress and ROS Link Diabetes and Cancer. 2024, J. Mol. Pathol., 5, 96–119. https:// doi.org/10. 3390.

- Garrison, F.H. ; An Introduction to the History of Medicine, Saunders: Philadelphia, USA, 1929; p. 31.

- Warren, S. ; The immediate causes of death in cancer. AM. J. Med. Sci. 1932, 184, 610–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, D. ; Role of free radicals in mutation, cancer, aging, and the maintenance if life. Radiat. Res. 1962, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon, D. ; The free radical theory of aging. In Free Radicals in Biology, Pryor, WA. Ed.; Academic Press; NY, USA, 1982; pp. 255-275.

- Black HS: Reassessment of a free radical theory of cancer with emphasis on ultraviolet carcinogenesis. Integr. Cancer Therapies. 2004, 3:279-293.

- Watson, A.F. , Mellanby, E.: Tar cancer in mice II. The condition of the skin when modified by external treatment or diet, as a factor in influencing this cancerous reaction. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1930, 11: 311-322.

- Elmets, CA. , Mukhtar, H.: Ultraviolet radiation and skin cancer: progress in pathophysiologic mechanisms. Prog. Dermatol. 1996, 30: 1-16.

- Baumann, CA. , Rusch, HP.: Effect of diet on tumors induced by ultraviolet light. Am. J. Cancer. 1939, 35: 213-221.

- Black, HS. , Lenger, W., Phelps, AW., Thornby, JI.: Influence of dietary lipid upon ultraviolet light-carcinogenesis. Nutr. Cancer. 1983, 5: 59-68.

- Black, HS. : Dietary factors in ultraviolet carcinogenesis. The Cancer Bull. 1993, 45: 232- 237.

- Ip, C. , Carter, CA.; Ip, MM.: Requirement of essential fatty acid for mammary tumorigenesis in the rat. Cancer Res. 1985, 45: 1997-2001. [Google Scholar]

- Reeve, VE. , Matheson, M., Greenoak, GE., Canfield, PJ., Boehm-Wilcox, C., Gallagher, CH.: Effect of dietary lipid on UV light carcinogenesis in the hairless mouse. Photochem. Photobiol. 1988, 48: 689-696. [CrossRef]

- 21.Orengo, IF. 21.Orengo, IF., Black, HS., Kettler, AH., Wolf, JE., Jr.: Influence of dietary Menhaden oil upon carcinogenesis and various cutaneous responses to ultraviolet radiation. Photochem. Photobiol. 1989, 49: 71-77.

- Chung, HT. , Burnham, DK., Robertson, B., Roberts, LK., Daynes, RA.: Involvement of prostaglandins in the immune alterations caused the exposure of mice to ultraviolet radiation. J. Immunol. 1986, 137: 2378-2884.

- Henderson, CD. , Black, HS., Wolf, JE, Jr.: Influence of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid sources on prostaglandin levels in mice. Lipids. 1989, 24:502-505.

- Orengo, IF. , Gerguis, J., Phillips, R., Guevare. A., Lewis, AT., Black, HS.: Celecoxib, a cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor as a potential chemopreventive to UV-induced skin cancer. 2002, Arch. Dermatol. 138: 751-755. www.ARCHDERMATOL.

- Meeran, SM. , Singh, Nagy, TR., Katiyar, SK.: High-fat diet exacerbates inflammation and cell survival signals in the skin of ultraviolet B-irradiated C57BL/6 mice. Toxicol Appl. Pharmacol. 2009, 15;241(3):303-310. [CrossRef]

- Utsumi, H. , Ichikawa, K., Takeshita, K.: In vivo ESR measurements of free radical reactions in living mice. Toxicol. Lett. 1995, 82: 561-565.

- Black, HS. : ROS: A step closer to elucidating their role in the etiology of light-induced skin disorders. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2004, 122: xiii-ix (Editorial) Doi. 10111/j.0022-202X.2004.22625.

- Black, HS. : Oxidative Stress and ROS Link Diabetes and Cancer. J. Mol. Pathol. 2024, 5: 96–119. https:// doi.org/10. 3390. [Google Scholar]

- Djuric, Z., Lewis, SM., Lu, MH., Mayhugh, M,, Tang, N., Hart, RW.: Effect of varying dietary fat levels on rat growth and oxidative DNA damage. Nutr Cancer 2001, 39:214–9. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, MA. , Black, HS.: Modification of membrane composition, eicosanoid metabolism, and immunoresponsiveness by dietary omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid sources, modulators of ultraviolet-carcinogenesis. Photochem. Photobiol. 1991, 54: 381-387.

- Moison, RM. , Beijersbergen Van Henegouwen, GM.: Dietary eicosapentaenois acid prevents systemic immunosuppression in mice induced by UVB radiation. Radiat. Res. 2001, 156: 36-44.

- Kang, JX. , Fat-1 transgenic mice: A new model for omega-3 research. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty acids. 2007, 77: 263-267.

- Xia, S. , Lu, Y., Wang, J., He, C., Hong, S., Serhan, CN., Kang, JX.: Melanoma growth is reduced in fat-1 transgenic mice: Impact of omega-6/omega-3 essential fatty acids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103: 12499-12504.

- Black, HS. , Okotie-Eboh, G., Gerguis, J.: Dietary fat modulates immunoresponsiveness in UV-irradiated mice. Photochem, Photobiol. 1995, 62: 964-969.

- Okotie-Eboh, G. , Gerguis, J., Black, HS.: Influence of dietary lipid on hapten-specific UV-induced immunosuppression. Photodermatol.Photoimmunol. Photomed. 1998, 14:116-118.

- Black, HS. , Thornby, JI., Gerguis, J., Lenger, W.: Influence of dietary omega-6, 3-fatty acid sources on the initiation and promotion stages of photocarcinogenesis. Photochem. Photobiol. 1992, 56: 195-199.

- Forbes, PD. , Beer, JZ., Black, H.S, Cesarini, J-P., Cole, CA., Davies, RE., Davitt, JM., deGruijl, F., Epstein, J., Fourtanier, A. et.al.: Standardized protocols for photocarcinogenesis safety testing. Frontiers in Bioscience 2003, 8: 848-854.

- Graham, S. : Results of case-controlled studies of diet and cancer in Buffalo, New York. Cancer Res. 1983, 43 (Suppl): 2409-2413.

- Hunter, DJ. , Colditz, GA., Stampler, MJ.,Rosner, B., Willett, WC., Soeizer, FE.: Diet and risk of basal cell carcinoma of the skin in a prospective cohort of women. Ann. Epidermal. 1992, 2: 231-239.

- van Dam, RM. , Huang, Z., Giovannucci, E., Rimm, EB., Hunter, DJ., Colditz, GA., Stampfer, MJ., Willett, WC.: Dit and basal cell carcinoma of the skin in a prospective cohort of men. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 71: 135-141.

- Davies, TW. , Treasure, FP., Welch, AA., Day, NE.: Diet and basal cell skin cancer: results from the EPIC-Norfolk cohort. Br. J. Dermatol. 2002, 146: 1017-1022.

- Gamba, CS. , Stefanick, ML, Larson, J., Linos., E., Sims, ST., Marshall, J., Van Horn, L., Zeitouni, N., Tang, JY.: Low-Fat Diet and Skin Cancer Risk: The Women's Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Dietary Modification Trial. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2013, 22 (9): 1509–1519. [CrossRef]

- Thind, IS. : Diet and cancer – an international study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 1: 1986, 15, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, B. , Doll, R. Environmental factors and cancer incidence and mortality in different countries, with special reference to dietary practices. Int. J. Cancer, 1975, 15: 617-631.

- Rackett, SC. , Rothe, MJ., Grant-Kels, JM.: Diet and Dermatology. J. Am. Acad. 4: Dermatol, 1993, 29, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Karagas, MR. : Occurrence of cutaneous basal cell an squamous cell malignancies among those with a prior history of skin cancer. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1: 1994, 102 (Suppl), 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Black, HS. , Herd, JA., Goldberg, LH., Wolf, JE., Thornby, JI., Rosen, T., Bruce, S., Tschen, JA., Foreyt, JP., Scott, LW.et.al.: Jaax, S.: Effect of a low-fat diet on the incidence of actinic keratosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994, 330: 1272-1275.

- Black, HS. , Thornby, JI., Wolf, JE., Goldberg, LH., Herd, JA., Rosen, T., Bruce, S., Tschen, JA., Scott, LW., Jaax, S., et.al.: Evidence hat a low-fat diet reduces the occurrence of non-melanoma skin cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 1995, 62: 165-169.

- Jaax, S. , Scott, LW., Wolf, JE., Thornby, JI., Black, HS.: General guidelines for a low-fat diet effective in the management and prevention of nonmelanoma skin cancer. Nutr. Cancer, 1997, 27: 150-156.

- 49. Black, HS. 49. Black, HS.: Omega-3 fatty acids and non-melanoma skin cancer. In Handbook of diet. Nutrition and skin. Preedy, VR., Ed.: Wageningen Academic: Wagenin, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 367-378.

- Bang, H. , Dyerberg, J.: Plasma lipids and lipoprotein pattern in Greenlandic west-coast Eskimos. Acta Medical Scandinavia, 1972, 192: 85-94.

- Dyerberg, J. , Bang, H.: Eicosapentaenoic acid and prevention of thrombosis and atherosclerosis? Lancet 1978, 15: 117-119.

- Orengo, IF. , Black, HS., Wolf, JE, Jr., Influence of fish oil supplementation on the minimal erythema dose in humans. Arch. Dermatol. Res., 1992, 284: 219-221.

- Rhodes, LE. , O’Farrell, S., Jackson, MJ., Friedmann, PS.: Dietary fish-oil supplementation in humans reduces UVB-erythemal sensitivity but increases lipid peroxidation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1994, 103: 151-154.

- Rhodes, LE. , Shahbakhti, H., Azurdia, RM., Moison, RM., Steenwinkel, M.J, Homburg, MI., Dean MP., McArdle, F., Beijersbergen van Henegouwen, GM., Epe, B., et. Al.: Effect of eicosapentaenoic acid, an omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, on UVR-related cancer risk in humans. An assessment of early genotoxic markers. Carcinogenesis. 2003, 24(5):919-925. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pupe, R. , Moison, R., De Haes, P., van Henegouwen, GB., Rhodes, L., Degree, H., Garmyn, M.: Eicosapentaenoic Acid, a n-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Differentially Modulates TNF-α, IL-1α, IL-6 and PGE2 Expression in UVB-Irradiated Human Keratinocytes, J. Invest. Dermatol. 2002, 118: 692-698. [CrossRef]

- Shahbakhti,H., Watson, REB., Azurdia,,RM., Ferreira, CZ., Garmyn, M., Rhodes, LE.: Influence of Eicosapentaenoic Acid, an Omega-3 Fatty Acid, on Ultraviolet-B Generation of Prostaglandin-E2 and Proinflammatory Cytokines Interleukin-1β, Tumor Necrosis Factor-α, Interleukin-6 and Interleukin-8 in Human Skin In Vivo. Photochem. Photobiol. 2004, 80: 231-235. [CrossRef]

- Storey. A., McArdle, F., Friedmann, PS., Jackson, MJ., Rhodes, LE.: Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Docosahexaenoic Acid Reduce UVB- and TNF-α-induced IL-8 Secretion in Keratinocytes and UVB-induced IL-8 in Fibroblasts. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2005, 124: 248-255. [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, SM. , Massey, KA., Bennett, SP., MI Al-Aasswad, N., Roshdy,K., Gibbs, NK. Friedmann, PS., Nicolaou, A., Rhodes, LE.: Randomized controlled trial of oral omega-3 PUFA in solar-simulated radiation-induced suppression of human cutaneous immune responses. 2013, Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 97: 646-652. [CrossRef]

- Black, HS. , Rhodes, LE.: The potential of omega-3 fatty acids in the prevention of non-melanoma skin cancer. Can. Det. Prev. 2006, 30: 224-232. Doi. 10.1016/j.cdp.2006.04.

- Rahrovani, F. , Javanbakht, MH., Ghaedi, E., Mohammadi, H., Ehsani, AH., Esrafili, A., Djalali, M.: Erythrocyte Membrane Unsaturated (Mono and Poly) Fatty Acids Profile in Newly Diagnosed Basal Cell Carcinoma Patients. Clin Nutr Res. 2018, 7: 21-30. [CrossRef]

- Harris, WS. : The Omega-6: Omega-3 ratio: A critical appraisal and possible successor. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids, 2018, 132, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hakim, I. , Harris, R., Ritenbaugh, C.: Fat intake and risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Nutr. Cancer. 2000, 36: 155-162. [CrossRef]

- Wallingford, SC. , Hughes, MC., Adèle C. Green, AC., van der Pols, JC.: Plasma Omega-3 and Omega-6 Concentrations and Risk of Cutaneous Basal and Squamous Cell Carcinomas in Australian Adults. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2013, 22): 1900–1905. [CrossRef]

- Wallingford, SC. , van As, JA., Hughes, MC., TI., Green, AC., van der Pols, JC.: Intake of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids and risk of basal and squamous cell carcinomas of the skin: a longitudinal community-based study in Australian adults. Nutr. Cancer. 2012, 2012;64:982-990. [CrossRef]

- Seviiri, M. , Law, MH., Ong, JS., Gharahkhani, P., Nyholt, DR., Olsen., CM., Whiteman., DC., MacGregor, S.: Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Levels and the Risk of Keratinocyte Cancer: A Mendelian Randomization Analysis. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2021, 30:1591-1598. [CrossRef]

- Wu. B, Pan, F., Wang, Q., Liang Q., Qiu, H., Zhou, S., Zhou, X.: Association between blood metabolites and basal cell carcinoma risk: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15:1413777. [CrossRef]

- Park MK, Li WQ, Qureshi AA, Cho E. Fat Intake and Risk of Skin Cancer in U.S. Adults. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018,27:776-782. [CrossRef]

- Miura K, Way M, Jiyad Z, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid intake and decreased risk of skin cancer in organ transplant recipients. European Journal of Nutrition. 2021 Jun;60(4):1897-1905. [CrossRef]

- Miura K, Vail A, Chambers D, Hopkins PM, Ferguson L, Grant M, Rhodes LE, Green AC. Omega-3 fatty acid supplement skin cancer prophylaxis in lung transplant recipients: A randomized, controlled pilot trial. J Heart Lung Trans-plant. 2019 Jan;38(1):59-65. [CrossRef]

- Yen, A. , Black, HS., Tschen, J.: Effect of dietary omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid sources on PUVA-induced cutaneous toxicity and tumorigenesis. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 1994, 286: 331-336.

- Gibbs, NK. , Honigsmann, H., Young, AR.: PUVA treatment strategies and cancer risk. Lancet, 1986, 1: 150-151.

- Black, HS. , Chan, JT.: Suppression of ultraviolet light-induced tumor formation by dietary antioxidants. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1975, 65: 412-414.

- Black, HS. , Lenger, WA., Gerguis, J., Thornby, JI.: Relation of antioxidants and level of dietary lipid to epidermal peroxidation and ultraviolet carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1985, 45: 6254-6259.

- Black, HS. , Chan, JT., Brown, GE.: Effects of dietary constituents on ultraviolet light-mediated carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1978, 38: 1384-1387.

- Pauling, L. , Willoughby, R., Reynolds, R., Blaisdell, BE., Lawson, S.: Incidence of squamous cell carcinoma in hairless mice irradiated with ultraviolet light on relation to intake of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) and D,L-alpha-tocopherol acetate (vitamin E). 1982, Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. Suppl. 23: 53-82.

- De Rios, G. , Chan, JT., Black, HS., Rudolph, AH., Knox, JM.: Systemic protection by antioxidants against UVL-induced erythema. J Invest Dermatol. 1978, 70: 123-5. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, AO. , McCann, V., Black, HS.: Dietary modification of UV-induced epidermal ornithine decarboxylase, 1980, J. Invest. Dermatol. 75: 408-410.

- Black, HS. , Kleinhans, CM., Hudson, HT., Sayre, RM., Agin, PP.: Studies on the mechanism of protection by butylated hydroxytoluene to UV-radiation damage. Photobiochem. Photobiophys. 1980, 1: 119-123.

- Daniel, JW. , Gage, JB.: The absorption and excretion of butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) in the rat. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 1965, 3: 405-415. [CrossRef]

- Hathway, DE. : Metabolic fate in animals of hindered phenolic antioxidants in relation to their safety evaluation and antioxidant function. Adv. Food Res. 1966, 15: 1-56. [CrossRef]

- Black, HS. , Lenger, W., Gerguis, J., McCann, V.: Studies on the photoprotective mechanism of butylated hydroxytoluene. Photochem. Photobiol. 1984, 40: 69-75.

- Koone, MD. , Black, HS.: A mode of action for butylated hydroxytoluene-mediated photoprotection. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1986, 87: 343-347. [CrossRef]

- Astbury, WT. , Street, A.: X-ray studies of the structure of hair, wool, and related fibres. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond [Biol.] 1932, A230: 75-102.

- Solan, JL. , Laden, K.: Factors affecting the penetration of light through stratum corneum. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 1977, 28: 125-137.

- Owens, DW. , Knox, JM., Hudson, HT., Troll, D.: Influence of humidity on ultraviolet injury. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1975, 64: 250-252.

- Black, HS. , Tigges, J.: Evaluation of structurally related phenols for anti-photocarcinogenic and photoprotective properties. Photochem. Photobiol. 1986, 43: 403-408. [CrossRef]

- IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk of Chemicals to Humans: Some Naturally Occurring and Synthetic Food Components, Furocoumarins and Ultraviolet Radiation. IARC, Lyon, France, Vol. 40, 1986, pp.161-206.

- Williams, GM. , Iatropoulos, MJ., Whysner, J.: Safety assessment of butylated hydroxyanisole and butylated hydroxytoluene as antioxidant food additives. Food. Chem. Toxicol. 1999, 37: 1027-1038. [CrossRef]

- Lanigan, RS. , Yamarik, TA.: Final report on the safety assessment of BHT (1). Int. J. Toxicol. 2002, 21 ( Suppl 2): 19-94. [CrossRef]

- Olsen, P. , Bille, N., Meyer, O.: Hepatocellular neoplasms in rats induced by butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT). Acta. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1983, 53: 433-434.

- Witschi, HP. , Morse, CC.: Enhancement of tumor formation in mice by dietary butylated hydroxytoluene: dose-time relationships and cell kinetics. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1983, 71: 859-866.

- Chan, JT. , Ford, JO., Rudolph, AH., Black, HS.: Physiological changes in hairless mice maintained on an antioxidant supplemented diet. Experientia, 1977, 33: 72.

- Black, HS. , Gerguis, J.: Use of the Ames test in assessing the relation of dietary lipid and antioxidants to N-2-fluorenylacetamide activation. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. 1980, 4: 131-138.

- Centers for Science in the Public Interest. Butylated Hydroxytoluene (BHT) Washington, DC 20005. https://www.cspinet.

- Zhou, Y. , Zheng, J., Li, Y., Xu, D-P., Li, S., Chem, Y0M., Li, H-B.: Natural polyphenols for prevention and treatment of cancer. 5: Nutrients 2016, 8, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afaq, F. , Katiyar, SK.: Polyphenols: Skin Photoprotection and inhibition of photocarcinogenesis. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2011, 11: 1200-1215.

- Lin, BW. , Gong, CC., Song, HF., Cu,i YY.: Effects of anthocyanins on the prevention and treatment of cancer. Br J Pharmacol. 2017, 174: 1226-1243. [CrossRef]

- Wang, E. , Liu, Y., Xu, C., Liu, J.: Antiproliferative and proapoptotic activities of anthocyanin and anthocyanidin extracts from blueberry fruits on B16-F10 melanoma cells. Food Nutr. Res. 2017, 19:1325308. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H-P., Yuan-Wei Shih, Y-W., Yun-Ching, Chang, Y-C., Chi-Nan Hung, C-N., Chau-Jong Wang, C-J.: Chemoinhibitory Effect of Mulberry Anthocyanins on Melanoma Metastasis Involved in the Ras/PI3K Pathway J. Agric. Food Chem. 9: 2008, 56, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Afaq, F. , Syed, DN., Malik, A., Hadi, N., Sarfaraz, S., Kweon, MH., Khan, N., Zaid, MA., Mukhtar, H.: Delphinidin, an anthocyanidin in pigmented fruits and vegetables, protects human HaCaT keratinocytes and mouse skin against UVB-mediated oxidative stress and apoptosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007, 127: 222-232. [CrossRef]

- Wang, LS. , Stoner, GD.: Anthocyanins and their role in cancer prevention. Cancer Lett. 2008, 269: 281-290. [CrossRef]

- Negri, A. , Naponelli, V., Rizzi F., Bettuzzi, S.: Molecular Targets of Epigallocatechin-Gallate (EGCG): A Special Focus on Signal Transduction and Cancer. Nutrients. 2018 Dec 6;10(12):1936. [CrossRef]

- Gębka, N. , Gębka-Kępińska, B., Adamczyk, J., Mizgała-Izworska. E.: The use of flavonoids in skin cancer prevention and treatment. J. Pre-Clin. and Clin. Res. 2022,16:108-113. [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar, H. , Ahmad, N.: Tea polyphenols: prevention of cancer and optimizing health. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, ;71S:1698S-1702S. [CrossRef]

- Mukhtar H, Wang ZY, Katiyar SK, Agarwal R. Tea components: antimutagenic and anticarcinogenic effects. Prev Med. 1992 May;21(3):351-60. [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, SK. : Green tea prevents non-melanoma skin cancer by enhancing DNA repair. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011, 15::152-158. [CrossRef]

- Meeran SM, Akhtar S, Katiyar SK. Inhibition of UVB-induced skin tumor development by drinking green tea polyphenols is mediated through DNA repair and subsequent inhibition of inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. 2009,129:1258-70. [CrossRef]

- Gensler, HL. , Timmermann, BN., Valcic, S., Wächter, GA., Dorr, R., Dvorakova, K., Alberts, DS.: Prevention of photocarcinogenesis by topical administration of pure epigallocatechin gallate isolated from green tea. Nutr. Cancer. 1996; 26:325-335. [CrossRef]

- Bushman, JL: Green tea and cancer in humans: A review of the literature. Nutr. Cancer 1998, 31: 151–159. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, SY. , Li, Y., Jiang, D., Zhao, J., Ge, JF.: Anticancer effect and apoptosis induction by Quercetin in the human lung cancer cell line A-549. Mo; Med. Rep. 2012, 822-826.

- Chen, HS. , Bai, MH., Zhang, T., Li, GD., Liu, M.: Ellagic acid induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis through TGF-beta/Smad3 signaling pathway in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 46: 1730-1738.

- Berman, AY., Motechin; Wiesenfeld, MY. , Holz, MK.: The therapeutic potential of resveratrol: A review of clinical trials. NPJ Precis Oncol. 3: 2017, 1, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Ishag, RK. , Abotaleb, M., Kubatka, P., Kajo, K.., Busselberg, D.: Flavonoids and their anti-diabetic effects: Cellular mechanisms and effects to improve blood sugar levels. 4: Biomolecules 2019, 9, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, MH. , Reagan-Shaw., S., Wu, J., Longley, J., Ahmad, N.: Chemoprevention of skin cancer by grape constituent resveratrol: relevance to human disease? FASEB J. 2005, 19: 1193-1195. [CrossRef]

- Salehi, B. , Mishra, AP., Nigam, M., Sener, B., Kilic, M., Sharifi-Rad, M., Fokou, PVT., Martins, N., Sharifi-Rad, J.: Resveratrol: A Double-Edged Sword in Health Benefits. Biomedicines. 2018, 9:91. [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, BB. , Kumar, A., Bharti, AC.: Anticancer potential of curcumin: preclinical and clinical studies. Anticancer Res. 2003, 23:363-98.

- Tsai, K-D., Lin, J-C., Yang,S-m., Tseng,M-J., Hsu, J-D. Lee, Y-J. Cherng, L-M.; Curcumin Protects against UVB-Induced Skin Cancers in SKH-1 Hairless Mouse: Analysis of Early Molecular Markers in Carcinogenesis Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Med. 2012, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J. , Moore-Medlin, T., Sonavane, K., Ekshyyan, O., McLarty, J., O Nathan, C-A.: Curcumin inhibits UV radiation-induced skin cancer in SKH-1 mice. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2013, 148:797-803. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, V. , Venkatesan, B., Tumala, A, Vellaichamy, E.: Topical application of Gallic acid suppresses the 7,12-DMBA/Croton oil induced two-step skin carcinogenesis by modulating anti-oxidants and MMP-2/MMP-9 in Swiss albino mice. Food and Chem.Toxicol.2014, 66: 44-55. [CrossRef]

- de Jesus, SF. , de Souza, MG., Queiroz, LDRP., de Paula, DPS., Tabosa, ATL., Alves, WSM., da Silveira, LH., Ferreira, ATDS., Martuscelli, OJD., Farias, LC., et.al.: Gallic acid has an inhibitory effect on skin squamous cell carcinoma and acts on the heat shock protein HSP90AB1. Gene. 2023, 30: 851:147041. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A. , Mishra, A.: Gallic acid: molecular rival of cancer. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol.. 2013, 35:473-485. [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, M. , Rejitharaji, S., Prabhaka, T., Murugaraj, M.. Singh, RB.: Modulating Effect of Ferulic Acid on NF-kB, COX-2 and VEGF Expression Pattern During 7, 12-Dimethylbenz(a)anthracene Induced Oral Carcinogenesis The Open Nutraceuticals J. 2014, 7: 33-38: DOI 10. 2174. [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu, C. , Secme, M., Bagei, G., Dodurga, Y.: Assessment of the anticancer mechanism of ferulic acid via cell cycle and apoptotic pathways in human prostate cancer cell lines. Tumor Biol, 2015, 36: 9437-9446.

- Lin, X-F., Min, W., Luo, D.: Anticarcinogenic effect of ferulic acid on ultraviolet-B irradiated human keratinocyte HaCaT cells. J. 1: Medicinal Plants, 2010, 4, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Ambothi, K. , Prasad, N., Rajendra, N., Balupillai, A.: Ferulic acid inhibits UVB-radiation induced photocarcinogenesis through modulating inflammatory and apoptotic signaling in Swiss albino mice. Food and Chem. Toxicol. 2015, 82: 72-78. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, C. The Illiad, Homer, A New Translation.; HarperCollins Publishers, Sydney, NSW 2000, Australia, 2016; www.harpercollins.com.

- Kyriazia, M. , Yovaa, D., Rallis, M., Limac, A.: Cancer chemopreventive effects of Pinus Maritima bark extract on ultraviolet radiation and ultraviolet radiation-7,12,dimethylbenz(a) anthracene induced skin carcinogenesis of hairless mice. Cancer Letters. 2006, 237: 234–241. www.elsevier.

- The Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University. https://lpi.oregonstate.

- Dunham, WB. , Zuckerkandl, E., Reynolds, R., Willoughby, R., Marcuson, R., Barth, R., Pauling, L.: Effects of intake of L-ascorbic acid on the incidence of dermal neoplasms induced in mice by ultraviolet light. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1982, 79: :7532-7536. [CrossRef]

- Gerrish, KE. , Gensler, HL.: Prevention of photocarcinogenesis by dietary vitamin E. Nutr. Cancer. 1993, 19:125-33. [CrossRef]

- Gensler, HL, Magdaleno M. Topical vitamin E inhibition of immunosuppression and tumorigenesis induced by ultraviolet irradiation. Nutr. Cancer. 1991;15:97-106. [CrossRef]

- Gensler, HL. , Aickin, M., Peng, YM., Xu, M.: Importance of the form of topical vitamin E for prevention of photocar-cinogenesis. Nutr. Cancer. 1996, 26:183-91. [CrossRef]

- Burke, KE. : Interaction of vitamins C and E as better cosmeceuticals. Dermatologic Therapy 2007, 20: 314–32. Blackwell Publishing, Inc. [CrossRef]

- Burke, KE. : Photoprotection of the Skin with Vitamins C and E: Antioxidants and Synergies. In: Pappas, A. (eds) Nutrition and Skin. 2011, Springer, New York, NY. [CrossRef]

- Mussa, A. , Mohd Idris, RA., Ahmed, N., Ahmad, S., Murtadha, AH., Tengku Din, TADAA., Yean, CY., Wan, A., Rahman, WF., Lazim, N.,et. Al.: High-Dose Vitamin C for Cancer Therapy. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2022, 3: 15:711. [CrossRef]

- Bodeker, KL. , Smith, BJ., Berg, DJ., Chandrasekharan, C., Sharif, S., Fei, N., Vollstedt, S., Brown, H., Chandler, M., Lorack, A., et. al.: A randomized trial of pharmacological ascorbate, gemcitabine, and nab-paclitaxel for metastatic pancreatic cancer. Redox Biology 2024, 77: 103375, www.elsevier.

- Cotter. MA., Thomas, J., Cassidy, P., Robinette, K., Jenkins, N., Florel, SR., Leachman S, Samlowski, WE., Grossman, D.: N-acetylcysteine protects melanocytes against oxidative stress/damage and delays onset of ultraviolet-induced mela-noma in mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2007, 113(19):5952-8. [CrossRef]

- Le Gal, K.; Ibrahim, M.X.; Wiel, C.; Sayin, V.I.; Akula, M.K.; Karlsson, C.; Dalin, M.G.; Akyürek, L.M.; Lindahl, P.; Nilsson, J.; et al. Antioxidants can increase melanoma metastasis in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 2015, 7, 308re8 wwwScienceTranslationalMedicineorg. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assi, M. The differential role of reactive oxygen species in early and late stages of cancer. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. In-tegr. Comp. Physiol. 2017, 313, R646–R653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Agostini,F., Balansky,RM., Camoirano, A., De Flora, S. 6: Modulation of light-induced skin tumors by N -acetylcysteine and/or ascorbic acid in hairless mice Carcinogenesis, 2005, 26, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. , Osahon, OW. , Sekhar, RV.: GlyNAC (Glycine and N-Acetylcysteine) Supplementation in Mice Increases Length of Life by Correcting Glutathione Deficiency, Oxidative Stress, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Abnormalities in Mitophagy and Nutrient Sensing, and Genomic Damage. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, R.V. : GlyNAC (Glycine and N-Acetylcysteine) supplementation improves impaired mitochondrial fuel oxidation and lowers insulin resistance in patients with type 2 diabetes: Results of a pilot study. Antioxidants 2022, 11: 154. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, NB. , Shenoy, RUK., Kajampady, MK., Dcruz, CEM., Shirodkar, RK., Kumar, L., Verma, R.: Fullerenes for the treatment of cancer: an emerging tool. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2022, ;29: 58607-58627. [CrossRef]

- Martins, M. , Azoia, NG., Melle-Franco, M., Ribeiro, A., Cavaco-Paulo, A.: Permeation of skin with (C60) fullerene dispersions. Eng. Life Sci. 2017,17(7): 732-738. [CrossRef]

- Rondags, A. , Yuen, WY., Jonkman, MF., Horváth, B.: Fullerene C60 with cytoprotective and cytotoxic potential: prospects as a novel treatment agent in Dermatology? Exp Dermatol. 2017 Mar;26(3):220-224. [CrossRef]

- Saitoh, Y. , Ohta, H., Hyodo, H.: Protective effects of polyvinylpyrrolidone-wrapped fullerene against intermittent ultraviolet-A irradiation-induced cell injury in HaCaT cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B: Biology 2016, 163: 22-29. [CrossRef]

- Prylutska, SV. , Burlaka, AP., Klymenko, PP., Grynyuk, II., Prylutskyy, YI., Schütze, C., Ritter, U.: Using water-soluble C60 fullerenes in anticancer therapy. Cancer Nanotechnol. 2011, 2:105-110. [CrossRef]

- Bjelakovic, G.; Nikolova, D.; Gluud, L.L.; Simonetti, R.G.; Gluud, C. Mortality in randomized trials of antioxidant supplements for primary and secondary prevention: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2007, 297, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-H.; Folsom, AR.; Harnack, L.; Halliwell, B.; Jacobs, DR., Jr. Does supplemental vitamin C increase cardiovascular disease risk in women with diabetes? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 1194–2000 https://expertsumnedu/en/publications/does. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArdle, F. , Rhodes, L. E., Parslew, RAG., Close, GL., Jack, CIA., Friedmann, PS., Jackson, MJ.: Effects of oral vitamin E and beta-carotene supplementation on ultraviolet radiation-induced oxidative stress in human skin. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 80, 1270–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristow, M.; Zarse, K.; Oberbach, A.; Kloting, N.; Birringer, M.; Kiehntopf, M.; Stumvoll, M.; Kahn, C.R.; Bluher, M. Antioxidants prevent health-promoting effects of physical exercise in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 8665–8670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burton, GW. , Ingold, KU. : β-carotene: An unusual type of lipid antioxidant. Science 1984, 224, 569–573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: A Global Perspective; AICR: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hibino, M.; Maeki, M.; Tokeshi, M.; Ishitsuka, Y.; Harashima, H.; Yamada, Y. : A system that delivers an antioxidant to mitochondria for the treatment of drug-induced liver injury. Nat. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13: 6961. [CrossRef]

- Epstein, JH. : Effects of β-carotene on UV-induced skin cancer formation in the hairless mouse skin. Photochem. Photobiol. 1977, 25, 211–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santamaria, L. , Bianchi, A. , Arnaboldi, A., Andreoni, L:. Prevention of benzo(α)-pyrene photocarcinogenic effect by β-carotene and canthaxanthin. Med. Biol. Environ. 1981, 9, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews-Roth, MM. : Antitumor activity of β-carotene, canthaxanthin, and phytoene. Oncology 1982, 38, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews-Roth, MM. , Pathak, MA.: Phytoene as a protective agent against sunburn (>280 nm) radiation in guinea pigs. Photochem. Photobiol. 1975, 21: 261–263. [CrossRef]

- Mathews, MM. , Krinsky, NI.: Carotenoids affect development of UV-B induced skin cancer. Photochem. Photobiol. 1987, 46: 507–509. [CrossRef]

- Mathews-Roth, MM. , Krinsky, NI.: Carotenoid dose level and protection against UV-B- induced skin tumors. Photochem. Photobiol. 1985, 42: 35–38. [CrossRef]

- Gensler, HL, Aickin, M., Peng, YM.: Cumulative reduction of primary skin tumor growth in UV-irradiated mice by the combination of retinyl palmitate and canthaxanthin. Cancer Lett. 1990, 53: 27–31. [CrossRef]

- Rybski, JA. , Grogan, TM., Gensler, HL: Reduction of murine cutaneous UVB-induced tumor-inflitrating T lymphocytes by dietary canthaxanthin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1991, 9:, 892–897. [CrossRef]

- Black, HS. : Radical interception by carotenoids and effects on UV carcinogenesis. Nutr. Cancer 1998, 31, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, HS. , Okotie-Eboh, G., Gerguis, J.: Aspects of β-carotene-potentiated photocarcinogenesis. Photochem. Photobiol. 1999, 69: 32S.

- Nutrient Requirements of Laboratory Animals, 3rd ed.; Research Council/National Academy of Science: Washington, DC, USA, 1978; pp.

- Black, HS. , Okotie-Eboh, G., Gerguis, J.: Diet potentiates the UV-carcinogenic response to β-carotene. Nutr. Cancer 2000, 37, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, HS. , Boehm, F., Edge, R., Truscott, TG.: The benefits and risks of certain dietary carotenoids that exhibit both anti- and pro-oxidative mechanisms – A comprehensive review. Antioxidants 2020, 9: 265-295. [CrossRef]

- Black, HS. , Gerguis, J. : Modulation of dietary vitamins E and C fails to ameliorate β-carotene exacerbation of UV Carcinogenesis in mice. Nutr. Cancer 2003, 45, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, HS. : Pro-carcinogenic activity of β-carotene, a putative systemic photoprotectant. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 203, 3, 753–758. [CrossRef]

- Edge, R. , Truscott, TG. : Singlet oxygen and free radical reactions of retinoids and carotenoids—A Review. Antioxidants 2018, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews-Roth, MM. , Pathak, MA. , Parrish, J., Fitzpatrick, TB., Kass, EH., Toda, K., Clemens, W.: A clinical trial of the effects of beta-carotene on the responses of human skin to solar radiation. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1972, 59, 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews-Roth, MM. : Carotenoids in erythropoietic protoporphyria and other photosensitivity diseases. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1964, 691, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kune, GA. , Bannerman, S. , Field, B., Watson, LF., Cleland, H., Merenstein, D., Vitetta, L.: Diet, alcohol, smoking, serum β-carotene, and vitamin A in male nonmelanocytic skin cancer patients and controls. Nutr. Cancer 1992, 18, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, ER. , Baron, JA., Stukel, TA., Stevens, MM., Mandel, JS., Spencer, SK., Elias, PM., Lowe, N., Nierenberg, DW., Bayrd, G.; et. al.: A clinical trial of β-carotene to prevent basal-cell and squamous-cell cancer of the skin. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 323: 789–795. [CrossRef]

- Green, A. , Williams, G., Neale, R., Hart, V., Leslie, D., Parsons, P., Marks, GC., Gaffney, P., Battistuta, D., Frost, C., et. al.: A daily sunscreen application and beta carotene supplementation in prevention of basal-cell and squamous-cell carcinomas of the skin: A randomized trial. Lancet 1999, 354: 723–729. [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, ER. , Baron, JA., Karagas, MR., Stukel, TA., Nierenberg, DW., Stevens, MM., Mandel, JS., Haile, RW.: Mortality associated with low plasma concentration of beta carotene and the effect of oral supplementation. JAMA 1996, 275: 699–703. [CrossRef]

- Karagas, MR. , Greenberg, ER., Nierenberg, D., Stukel, TA., Morris, JS., Stevens, MM., Baron, JA.: Risk of squamous cell carcinoma of the skin in relation to plasma selenium, α-tocopherol, β-carotene, and retinol: A nested case-control study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1997, 6: 25–29.

- Stryker, WS. , Stampfer, MJ., Stein, EA., Kaplan, L., Louis, TA., Sober, A., Willett, WC.: Diet, plasma levels of β-carotene and alpha-tocopherol, and risk of malignant melanoma. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1990, 131: 597–611. [CrossRef]

- Kiripatrick, CS. , White, E., Lee, JAH.: Case-control study of malignant melanoma in Washington State. Am.. J. Epidemiol. 1994, 139: 869–880. [CrossRef]

- Breslow, RA. , Alberg, AJ., Helzlsouer, KJ., Bush, TL., Norkus, EP., Morris, JS., Spate, VE, Comstock, GW.: Serological precursors of cancer: Malignant melanoma, basal and squamous cell skin cancer, and diagnostic levels of retinol, β-carotene, lycopene, α-tocopherol, and selenium. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 1995, 4: 837–842.

- Bayerl, C. , Schwarz, B. In , Jung, EG.: Beneficial effect of β-carotene in dysplastic nevus syndrome—A randomized trial (abstract 068). In Proceedings of the 8th Congress of the European Society for Photobiology, Granada, Spain, 3–8 September 1999; p. 89. [Google Scholar]

- Druesne-Pecollo, N. , Latino-Martel, P., Norat, T., Barradon, E., Bertrais, S., Galan, P., Hercberg, S.: Beta-carotene supplementation and cancer risk: A systematic review and metanalysis of randomized controlled trials. Int..Cancer 2010, 127: 172–184. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y-T., Kao, C-J., Huang, H-Y. Huang, S-Y., Chen, C-Y., Lin, Y-S., Wen, Z-H., Wang, H-MD.: Astaxanthin reduces MMP expressions, suppresses cancer cell migrations, and triggers apoptotic caspases of in vitro and in vivo models in melanoma. J. 2: Functional Foods 2017,31, 2017. [CrossRef]

- The α-Tocopherol, β-Carotene Cancer Prevention Study Group.: The effect of vitamin E and β-carotene on the incidence of lung cancer and other cancers in male smokers. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 330: 1029–1035. [CrossRef]

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Cancer-Preventive Agents. C: IARC Handbooks of Cancer Prevention, 1998.

- Gary, E. , Goodman, MD., Thornquist, JB., Cullen, MR. Meyskens, FL. Omenn, GS., Valanis,B., Williams, JH. 1: Beta-Carotene and Retinol Efficacy Trial: Incidence of Lung Cancer and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality During 6-Year Follow-up After Stopping β-Carotene and Retinol Supplements, JNCI 2004, 96, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omenn, GS. : Chemoprevention of lung cancer: The rise and demise of beta-carotene. Ann. Rev. Public Health 1998, 19: 73–99. [CrossRef]

- Bayerl, C. : Beta-carotene in dermatology: Does it help? Acta Dermatoven APA 2008, 17, 160–166. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).