Submitted:

06 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

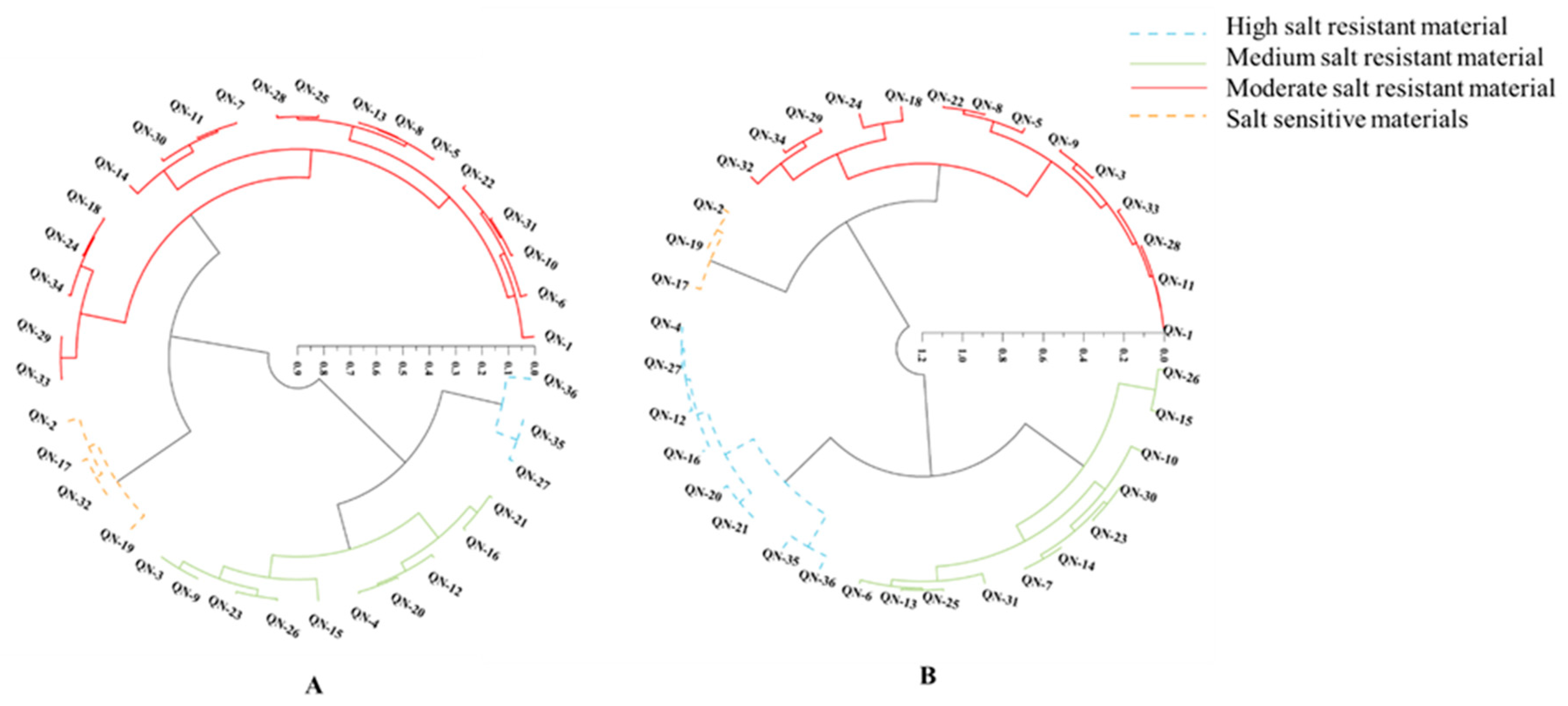

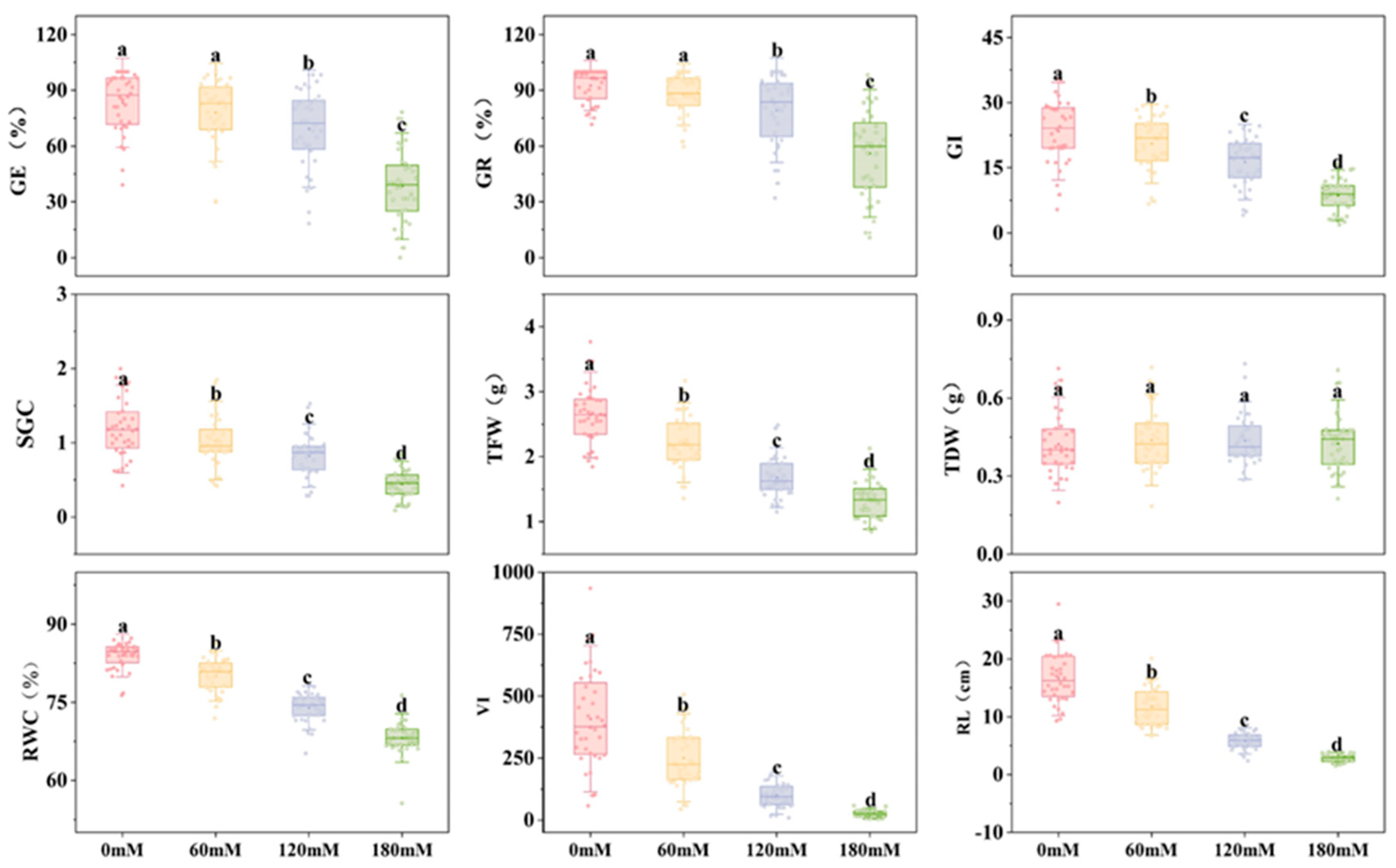

Various biotic and abiotic stresses challenge plant growth and production, with salt stress notably impeding normal development, compromising quality, and reducing yield in plants. The objective is to identify salt-tolerant soybean germplasm resources and develop a comprehensive method for assessing salt tolerance during soybean germination. This study involved the utilization of 36 soybean germplasm to induce varying degrees of salt stress through the application of 0, 60, 120, and 180 mmol/L NaCl solutions, employing the Petri dish germination identification method to assess nine phenotypic indices, such as germination potential, rate, and radicle length. The salt tolerance of soybean germination was comprehensively assessed using one-way ANOVA, multi-factor ANOVA, principal component analysis, affiliation function, quadratic regression equation analysis, and cluster analysis. These methods were employed to investigate the impact of varied NaCl concentrations on different germination indices, determine the best screening parameters for identifying soybean germination salt tolerance, and identify soybean germplasm with varying salt tolerances. The results indicated that soybean seeds exhibited tolerance to low salt concentrations, while concentrations exceeding 120 mmol/L led to significant inhibition of germination indicators. Notably, the vitality index and radicle length were highly sensitive indicators reflecting the impact of salt stress on seed germination. By analyzing the quadratic regression equation correlating the germination index and the salt tolerance coefficient, an LC50 value of 155.4 mmol/L with a coefficient of variation of 20.00% was derived. This value serves as a viable screening concentration for identifying salt tolerance during the soybean germination stage. Additionally, clustering analysis categorized 36 soybean varieties into 4 salt tolerance levels, with QN-27, QN-35, and QN-36 demonstrating high salt tolerance, and QN-2, QN-17, and QN-19 were classified as salt-sensitive materials.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. The Effects of Different Concentrations of NaCl on Various Indicators of Soybean Germination Stage

2.2. Multifactor Analysis of Variance of Each Single Indicator

2.3. Principal Component Analysis of the Salt Tolerance Coefficient

2.4. Analysis of the Affiliation Function

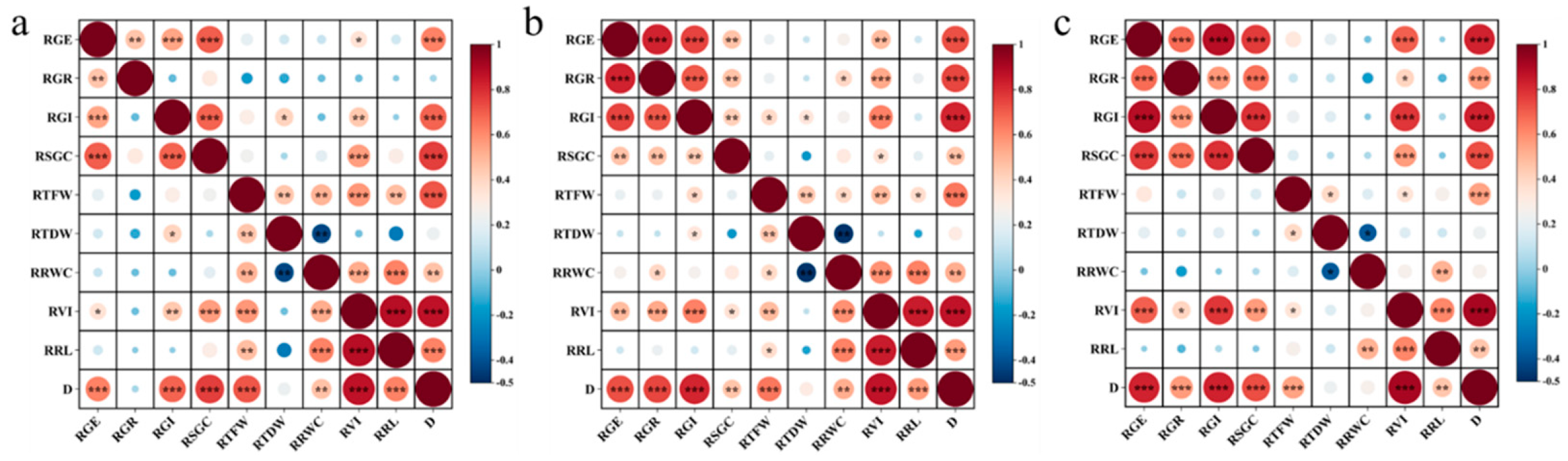

2.5. Correlation Analysis

2.6. Regression Analysis

2.7. Cluster Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Experimental Design

4.3. Data Statistics and Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, M.Y.; Van, K.; Kang, Y.J.; Kim, K.H.; Lee, S.-H. Tracing Soybean Domestication History: From Nucleotide to Genome. Breed. Sci. 2012, 61, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Ma, J. Genomic Introgression through Interspecific Hybridization Counteracts Genetic Bottleneck during Soybean Domestication. Genome Biol 2019, 20, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartman, G.L.; West, E.D.; Herman, T.K. Crops That Feed the World 2. Soybean—Worldwide Production, Use, and Constraints Caused by Pathogens and Pests. Food Sec. 2011, 3, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yang, D.; Li, M.; Shi, L. Metabolic Profiles Reveal Changes in Wild and Cultivated Soybean Seedling Leaves under Salt Stress. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0159622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, J.X.; Si, w. Development trends and policy suggestions of soybean industry in 2024. Soybean Science & Technology 2024, 1, 1–5. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Foti, C.; Khah, E.M.; Pavli, O.I. Germination Profiling of Lentil Genotypes Subjected to Salinity Stress. Plant Biol J 2019, 21, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gobade, A.; Arathi, S.; Gijare, S.; Pawar, D.; Patil, A.S. Evaluating Salt Tolerance in Soybean Core Collection: Germination Response under Salinity Stress. Genet Resour Crop Evol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munns, R.; Tester, M. Mechanisms of Salinity Tolerance. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2008, 59, 651–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qadir, M.; Quillérou, E.; Nangia, V.; Murtaza, G.; Singh, M.; Thomas, R.J.; Drechsel, P.; Noble, A.D. Economics of Salt-induced Land Degradation and Restoration. Natural Resources Forum 2014, 38, 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, A.; Riaz, S.; Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Gene Expression Profiling of Plants under Salt Stress. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 2011, 30, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cheng, X.; Zhu, H.; Bañuelos, G.; Shutes, B.; Wu, H. Influence of Salt Stress on Propagation, Growth and Nutrient Uptake of Typical Aquatic Plant Species. Nordic Journal of Botany 2019, 37, njb.02411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltabayeva, A.; Ongaltay, A.; Omondi, J.O.; Srivastava, S. Morphological, Physiological and Molecular Markers for Salt-Stressed Plants. Plants 2021, 10, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, N.T.; Vu, H.T.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, L.-A.T.; Nguyen, M.-C.D.; Hoang, K.L.; Nguyen, K.T.; Quach, T.N. Co-expression of Arabidopsis AtAVP1 and AtNHX1 to Improve Salt Tolerance in Soybean. Crop Science 2019, 59, 1133–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasheed, A.; Raza, A.; Jie, H.; Mahmood, A.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, L.; Xing, H.; Li, L.; Hassan, M.U.; Qari, S.H.; et al. Molecular Tools and Their Applications in Developing Salt-Tolerant Soybean (Glycine Max L.) Cultivars. Bioengineering 2022, 9, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, O.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, V.; Singh, T.; Kumar, R.; Auji, R. Salinity Stress Effect on Staple Food Crops and Novel Mitigation Strategies. Biologia 2024, 79, 2359–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Liao, X.; Cui, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhang, X.; Du, H.; Ma, Y.; Ning, L.; Wang, H.; Huang, F.; et al. A Cation Diffusion Facilitator, GmCDF1, Negatively Regulates Salt Tolerance in Soybean. PLoS Genet 2019, 15, e1007798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuffo, A.M.; Steiner, F.; Aguilera, J.G.; Teodoro, P.E.; Teodoro, L.P.R.; Busch, A. Multi-trait Stability Index: A Tool for Simultaneous Selection of Soya Bean Genotypes in Drought and Saline Stress. J Agronomy Crop Science 2020, 206, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Dou, W.; Chen, J.; Chen, J.W.; La, J, B. Characteristics of Spatial-temporal Dynamics of Soil Salinity in the YellowRiver Delta and Zoning and High Quality Utilization of Saline Soil. Geoscience 2024, 1–13. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Cao, D.; Yan, Y.L.; Xu, D.H. Assessment of Salt Tolerance and Analysis of the Salt Tolerance Gene Ncl in Indonesian Soybean Germplasm. Plant Genet. Resour. 2019, 17, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Tian, Y.; Qu, Z.; Wang, J.; Han, D.; Dong, S. Comparing the Salt Tolerance of Different Spring Soybean Varieties at the Germination Stage. Plants 2023, 12, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Wang, G.; Yu, X.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Song, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Guan, C. Assessing Alfalfa ( Medicago Sativa L.) Tolerance to Salinity at Seedling Stage and Screening of the Salinity Tolerance Traits. Plant Biol J 2021, 23, 664–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Zhang, H.; Zeng, Y.; Xiang, L.; Lei, Z.; Huang, Q.; Li, T.; Shen, F.; Cheng, Q. A Salt Tolerance Evaluation Method for Sunflower (Helianthus Annuus L.) at the Seed Germination Stage. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 10626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Ye, N.; Wang, X.; Das, D.; Tan, Y.; You, X.; Long, M.; Hu, T.; Dai, L.; Zhang, J.; et al. Drought Stress and Plant Ecotype Drive Microbiome Recruitment in Switchgrass Rhizosheath. JIPB 2021, 63, 1753–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahid, M.A.; Sarkhosh, A.; Khan, N.; Balal, R.M.; Ali, S.; Rossi, L.; Gómez, C.; Mattson, N.; Nasim, W.; Garcia-Sanchez, F. Insights into the Physiological and Biochemical Impacts of Salt Stress on Plant Growth and Development. Agronomy 2020, 10, 938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabravolski, S.A.; Isayenkov, S.V. The Regulation of Plant Cell Wall Organisation under Salt Stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1118313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Shao, Y.; Feng, X.; Otie, V.; Matsuura, A.; Irshad, M.; Zheng, Y.; An, P. Cell Wall Components and Extensibility Regulate Root Growth in Suaeda Salsa and Spinacia Oleracea under Salinity. Plants 2022, 11, 900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, F.; Zhou, H. Plant Salt Response: Perception, Signaling, and Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1053699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.T.; Sang, M.K. Enhancement of Osmotic Stress Tolerance in Soybean Seed Germination by Bacterial Bioactive Extracts. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0292855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhou, J.; Sui, N. Mechanisms of Salt Tolerance in Halophytes: Current Understanding and Recent Advances. Open Life Sciences 2018, 13, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Gao, Y.; Sun, S.; Lu, X.; Li, Q.; Li, L.; Wang, K.; Liu, J. Effects of Salt Stress on the Antioxidant Activity and Malondialdehyde, Solution Protein, Proline, and Chlorophyll Contents of Three Malus Species. Life 2022, 12, 1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Guan, R.; Bose, J.; Henderson, S.W.; Wege, S.; Qiu, L.; Gilliham, M. Soybean CHX-type Ion Transport Protein GmSALT3 Confers Leaf Na+ Exclusion via a Root Derived Mechanism, and Cl− Exclusion via a Shoot Derived Process. Plant Cell & Environment 2021, 44, 856–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, G.; Zhang, W.; Yang, W.; Ma, D.; Zhang, D.; Hao, D.; Hu, Z.; Yu, D. Association Mapping of Soybean Seed Germination under Salt Stress. Mol Genet Genomics 2015, 290, 2147–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, H.; Guo, J.; Wang, C.; Li, K.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.; Li, M.; Wang, B. An Effective Screening Method and a Reliable Screening Trait for Salt Tolerance of Brassica Napus at the Germination Stage. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Liao, X.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, W.; Li, Y.; Bhat, J.A.; Kan, G.; Yu, D. Linkage and Association Mapping of Wild Soybean (Glycine Soja) Seeds Germinating under Salt Stress. Journal of Integrative Agriculture 2022, 21, 2833–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravelombola, W.; Dong, L.; Barickman, T.C.; Xiong, H.; Olaoye, D.; Bhattarai, G.; Zia, B.; Alshaya, H.; Alatawi, I.; Shi, A. Evaluation of Salt Tolerance in Cowpea at Seedling Stage. Euphytica 2021, 217, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Treatment | index | GE/% | GR/% | GI | SGC | TFW/g | TDW/g | RWC/% | VI | RL/cm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0mM | Max | 100.00 | 100.00 | 37.13 | 2.00 | 3.77 | 0.71 | 89.34 | 934.42 | 29.49 |

| Min | 39.06 | 71.67 | 5.39 | 0.42 | 1.85 | 0.20 | 76.32 | 57.00 | 9.28 | |

| Mean | 83.36 | 92.58 | 23.45 | 1.19 | 2.64 | 0.42 | 83.99 | 408.26 | 16.69 | |

| SD | 15.97 | 8.96 | 7.53 | 0.39 | 0.44 | 0.12 | 2.73 | 196.27 | 4.33 | |

| CV | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.17 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.47 | 0.26 | |

| 60mM | Max | 100.00 | 100.00 | 29.33 | 1.85 | 3.17 | 0.72 | 86.35 | 506.23 | 20.10 |

| Min | 29.81 | 59.64 | 6.66 | 0.42 | 1.36 | 0.18 | 71.90 | 44.26 | 6.64 | |

| Mean | 78.09 | 87.66 | 20.54 | 1.03 | 2.22 | 0.44 | 80.08 | 251.17 | 11.77 | |

| SD | 17.67 | 11.08 | 6.07 | 0.35 | 0.41 | 0.12 | 3.19 | 118.64 | 3.28 | |

| CV | 0.23 | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.18 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.28 | |

| 120mM | Max | 98.33 | 100.00 | 26.26 | 1.53 | 2.49 | 0.73 | 78.49 | 212.73 | 9.07 |

| Min | 18.33 | 32.09 | 4.10 | 0.29 | 1.15 | 0.29 | 65.14 | 9.66 | 2.36 | |

| Mean | 69.31 | 79.31 | 16.33 | 0.83 | 1.68 | 0.44 | 73.93 | 100.77 | 5.83 | |

| SD | 20.97 | 18.73 | 5.77 | 0.28 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 2.80 | 51.44 | 1.51 | |

| CV | 0.30 | 0.24 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.04 | 0.51 | 0.26 | |

| 180 mM | Max | 78.27 | 98.13 | 15.79 | 0.86 | 2.13 | 0.71 | 76.34 | 58.41 | 3.90 |

| Min | 0.00 | 10.83 | 1.88 | 0.09 | 0.85 | 0.21 | 55.58 | 4.60 | 1.52 | |

| Mean | 38.47 | 56.07 | 8.65 | 0.45 | 1.34 | 0.43 | 68.22 | 25.35 | 2.79 | |

| SD | 19.06 | 22.94 | 3.86 | 0.20 | 0.31 | 0.11 | 3.12 | 14.14 | 0.68 | |

| CV | 0.50 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.23 | 0.28 | 0.05 | 0.56 | 0.24 |

| Index | Germplasm | NaCl concentration | Germplasm and NaClconcentration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGE | F | 27.176 | 300.58 | 2.199 |

| Sig | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| RGR | F | 22.849 | 171.023 | 2.193 |

| Sig | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| RGI | F | 39.542 | 497.529 | 2.376 |

| Sig | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| RSGC | F | 29.284 | 469.048 | 2.124 |

| Sig | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| RTFW | F | 23.385 | 612.680 | 1.989 |

| Sig | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| RTDW | F | 34.640 | 1.077 | 1.473 |

| Sig | <0.01 | >0.05 | <0.01 | |

| RRWC | F | 7.484 | 443.229 | 1.224 |

| Sig | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| RVI | F | 16.378 | 786.579 | 3.591 |

| Sig | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | |

| RRL | F | 17.471 | 1388.012 | 5.410 |

| Sig | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Item | Trait | 60 mM | 120 mM | 180 mM | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS1 | CS2 | CS3 | CS1 | CS2 | CS3 | CS1 | CS2 | CS3 | ||||

| Eigenverctor | RGE | 0.108 | 0.883 | 0.119 | 0.941 | 0.069 | -0.014 | 0.919 | 0.009 | 0.203 | ||

| RGR | -0.184 | 0.657 | -0.464 | 0.899 | 0.179 | -0.046 | 0.771 | -0.234 | 0.113 | |||

| RGI | 0.089 | 0.599 | 0.642 | 0.847 | 0.162 | 0.299 | 0.186 | -0.037 | -0.177 | |||

| RSGC | 0.306 | 0.850 | 0.168 | 0.815 | 0.248 | 0.218 | 0.897 | -0.006 | 0.020 | |||

| RTFW | 0.650 | 0.021 | 0.591 | 0.143 | 0.550 | 0.655 | 0.117 | 0.296 | 0.867 | |||

| RTDW | -0.277 | 0.053 | 0.874 | 0.151 | -0.233 | 0.935 | 0.201 | -0.352 | 0.878 | |||

| RRWC | 0.837 | -0.001 | -0.211 | 0.241 | 0.808 | -0.361 | 0.000 | -0.172 | 0.041 | |||

| RVI | 0.861 | 0.329 | 0.203 | 0.466 | 0.796 | 0.190 | -0.053 | 0.833 | -0.232 | |||

| RRL | 0.915 | 0.075 | -0.112 | 0.037 | 0.925 | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.869 | 0.196 | |||

| Eigenvalue | 3.484 | 2.114 | 1.616 | 3.395 | 2.623 | 1.609 | 3.727 | 2.020 | 1.716 | |||

| Contribution (%) | 38.708 | 23.493 | 17.956 | 37.728 | 29.141 | 17.877 | 41.414 | 22.449 | 19.065 | |||

| Cumulative contribution (%) | 38.708 | 62.201 | 80.157 | 37.728 | 66.869 | 84.746 | 41.414 | 63.863 | 82.928 | |||

| Weight coefficient (%) | 40.520 | 33.400 | 26.080 | 44.518 | 34.386 | 21.095 | 49.940 | 27.070 | 22.990 | |||

| Germplasm | Salt-tolerant half-lethal | Average value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGE | RGR | RGI | RSGC | RTFW | RVI | RRL | ||

| QN-1 | 3.16 | 3.38 | 2.51 | 2.20 | 3.66 | 0.93 | 1.17 | 2.43 |

| QN-2 | 0.97 | 1.78 | 2.29 | 1.62 | 2.49 | 1.29 | 1.63 | 1.73 |

| QN-3 | 3.25 | 2.52 | 2.28 | 2.48 | 3.76 | 1.62 | 2.10 | 2.57 |

| QN-4 | 2.89 | 3.38 | 2.59 | 2.96 | 4.50 | 2.14 | 2.54 | 3.00 |

| QN-5 | 2.71 | 2.87 | 2.36 | 2.67 | 2.47 | 1.65 | 2.10 | 2.40 |

| QN-6 | 2.90 | 5.67 | 2.65 | 3.08 | 2.70 | 1.18 | 1.40 | 2.80 |

| QN-7 | 3.70 | 5.08 | 2.80 | 2.52 | 2.94 | 1.27 | 1.58 | 2.84 |

| QN-8 | 2.68 | 2.93 | 2.57 | 2.70 | 2.70 | 1.23 | 1.29 | 2.30 |

| QN-9 | 2.84 | 2.96 | 2.62 | 1.18 | 2.99 | 1.51 | 1.76 | 2.27 |

| QN-10 | 3.43 | 6.73 | 2.34 | 3.92 | 4.32 | 1.19 | 1.90 | 3.40 |

| QN-11 | 2.32 | 2.49 | 2.38 | 2.32 | 2.54 | 1.90 | 2.33 | 2.33 |

| QN-12 | 3.51 | 3.90 | 3.09 | 2.95 | 2.73 | 1.78 | 1.81 | 2.82 |

| QN-13 | 2.85 | 4.63 | 2.59 | 2.94 | 2.74 | 1.11 | 1.36 | 2.60 |

| QN-14 | 3.42 | 3.50 | 2.99 | 2.83 | 3.00 | 0.49 | 1.18 | 2.49 |

| QN-15 | 2.87 | 4.53 | 2.77 | 2.97 | 3.07 | 1.47 | 1.77 | 2.78 |

| QN-16 | 5.74 | 9.46 | 3.80 | 4.06 | 3.28 | 1.33 | 1.66 | 4.19 |

| QN-17 | 1.88 | 1.74 | 1.66 | 1.54 | 2.69 | 0.90 | 1.55 | 1.71 |

| QN-18 | 2.52 | 2.54 | 2.23 | 2.38 | 3.18 | 1.07 | 1.49 | 2.20 |

| QN-19 | 2.54 | 2.58 | 2.29 | 1.97 | 2.31 | 0.93 | 1.13 | 1.96 |

| QN-20 | 3.04 | 11.24 | 2.54 | 3.16 | 3.03 | 1.72 | 2.16 | 3.84 |

| QN-21 | 3.29 | 3.47 | 3.12 | 2.85 | 3.18 | 1.45 | 1.51 | 2.69 |

| QN-22 | 2.82 | 3.16 | 2.43 | 2.79 | 2.94 | 1.19 | 1.48 | 2.40 |

| QN-23 | 2.50 | 2.91 | 2.64 | 2.50 | 3.05 | 1.46 | 1.84 | 2.41 |

| QN-24 | 2.71 | 4.03 | 2.31 | 2.24 | 2.86 | 0.92 | 1.26 | 2.33 |

| QN-25 | 3.77 | 3.35 | 3.15 | 3.51 | 2.55 | 1.01 | 1.22 | 2.65 |

| QN-26 | 2.77 | 3.86 | 2.75 | 2.85 | 2.99 | 1.68 | 1.83 | 2.67 |

| QN-27 | 3.59 | 2.34 | 3.27 | 3.53 | 3.34 | 1.78 | 1.43 | 2.75 |

| QN-28 | 2.79 | 3.92 | 2.70 | 2.04 | 2.92 | 1.01 | 1.37 | 2.39 |

| QN-29 | 2.37 | 2.72 | 2.33 | 2.15 | 2.60 | 1.37 | 1.69 | 2.17 |

| QN-30 | 3.47 | 3.48 | 3.01 | 3.35 | 3.40 | 0.86 | 0.93 | 2.65 |

| QN-31 | 3.23 | 3.32 | 2.70 | 2.38 | 2.87 | 1.06 | 1.33 | 2.41 |

| QN-32 | 2.85 | 3.59 | 2.34 | 2.18 | 2.47 | 0.89 | 1.11 | 2.20 |

| QN-33 | 2.82 | 3.53 | 2.65 | 2.46 | 2.39 | 1.07 | 1.22 | 2.31 |

| QN-34 | 2.67 | 2.89 | 2.46 | 2.43 | 2.27 | 1.06 | 1.14 | 2.13 |

| QN-35 | 4.09 | 5.06 | 2.75 | 2.86 | 3.90 | 2.03 | 2.47 | 3.31 |

| QN-36 | 3.85 | 4.96 | 3.42 | 3.08 | 3.65 | 1.41 | 1.65 | 3.15 |

| Mean | 3.02 | 3.90 | 2.65 | 2.66 | 3.01 | 1.30 | 1.59 | 2.59 |

| CV | 0.24 | 0.48 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.28 | 0.25 | 0.20 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).