Introduction

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles and play a crucial role in the metabolism of spermatozoa. They are implicated in various many cellular functions such as oxidative phosphorylation and calcium homeostasis which are important for function of sperm [

1,

2,

3,

7]. The mitochondria in spermatozoa regulates important functions relating to human fertility and infertility [

27,

12,

28]. The genetic modification of mitochondria and its role in sperm development and in spermatogenesis has gained significant attention in recent years. The understanding of the function of mitochondria in sperm cells may provide critical insights into the molecular basis of male infertility [

18,

35,

13]. Recent reports suggested that male infertility is associated with a loss of mitochondrial proteins in spermatozoa, which induces low sperm motility, reduces OXPHOS activity, and results in male infertility [

18].

The dynamics of mitochondria in sperm, including their distribution, fusion, and fission, are important for sperm function and viability. During the development of sperm, mitochondria undergo significant structural and functional changes. The role of mitochondrial fusion and fission in sperm motility is increasingly understood, as proper mitochondrial dynamics are necessary for the motility and structural integrity of the sperm tail [

10]. The use of various staining dye to label mitochondria of the sperm such as Mitotracker leads to defect in fertility of sperm. Therefore, fluorescent proteins may be used for studying the effect of mitochondria in the development of the sperm in vivo.

Previously, the PGK2 promoter has been demonstrated as a testis-specific promoter [

34]. The PGK2 promoter drives expression of transgene in spermatocytes and spermatids in vivo [

14,

9,

16,

33]. The combination of GFP with a mitochondrial localization signal (MLS) allows for study of mitochondria within sperm [

17,

31,

24,

5]. This strategy will help to visualize the mitochondria of the sperm in vivo.

Although the role of PGK2 promoter in spermatogenesis is well established, it isnot used for studying mitochondrial dynamics of the sperm. In this study, we used the PGK2 promoter driving the expression of GFP-tagged to a mitochondrial localization signal (PGK2-MLS-GFP) to express GFP specifically in the sperm in transgenic mice.

Material and methods

Animals

Mice (FVB/J), were obtained from the small animal facility of National Institute of Immunology, were used for the present study. All animals were kept at 24 ± 2°C under 14 h light and 10 h dark cycle and used as per the National Guidelines provided by the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of the Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA). Protocols for the experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee. Animals were kept in a hygienic air condition with suitable humidity and handled by trained personnel. The animals were killed individually in a separate room by carbon dioxide inhalation in an in-house built carbon-dioxide device and by cervical dislocation [

23].

Transgene Constructs

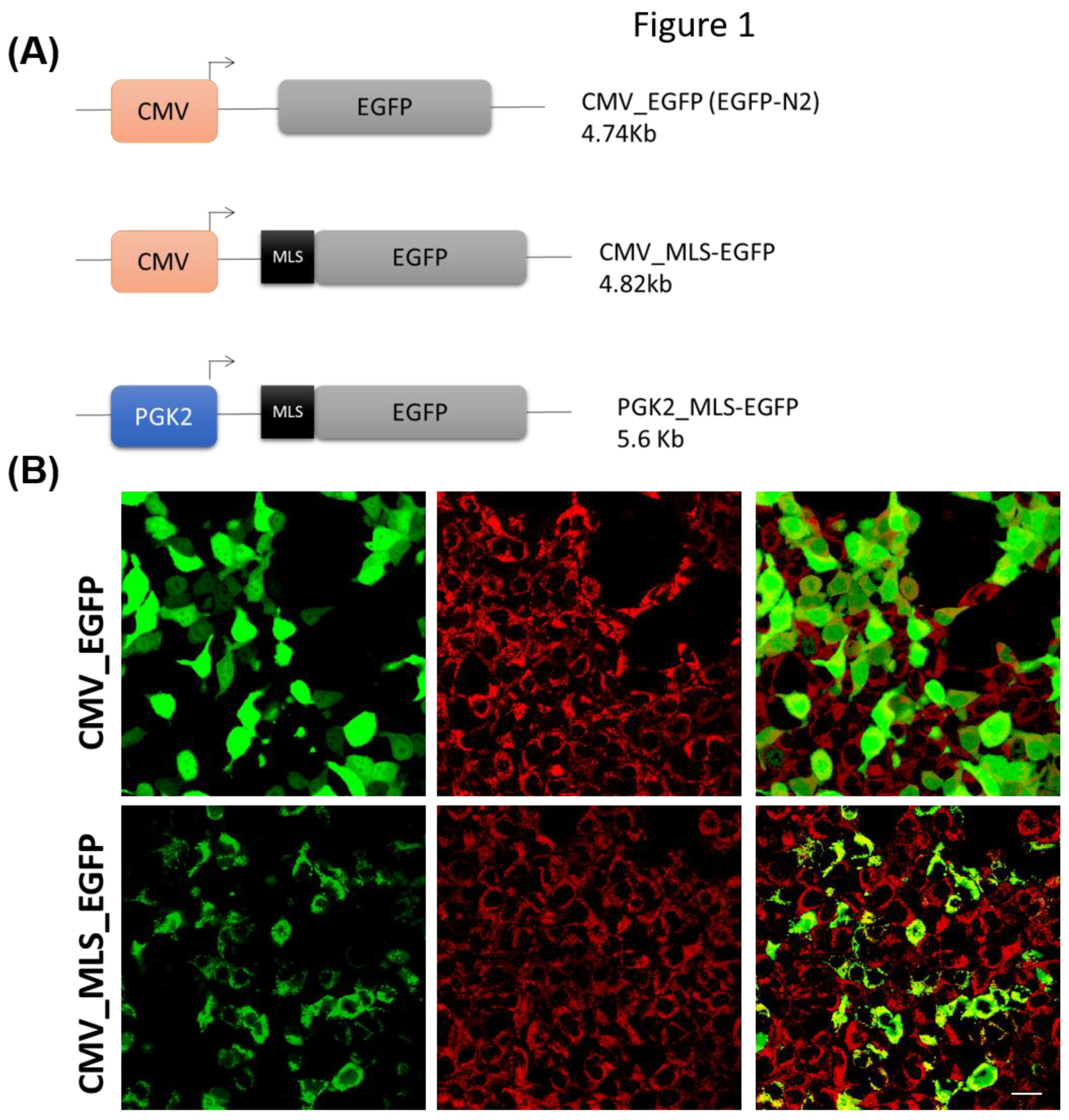

A total of three constructs were used in this study, and the schematic diagram were provided in

Figure 1A. The EGFPN

2 vector was used, and in this vector, mitochondrial localization signal of

COXVIII gene (TCCGTCCTGACGCCGCTGCTGCTGCGGGGCTTGACAGGCTCGGCCCGGCGGCTCCCAGTGCCGCGCGCCAAGA) (MLS) was added just before the coding sequence of

EGFP transgene. The CMV promoter from this vector was later replaced by PGK2 promoter of mice (1kb upstream region from the start codon of PGK2). The PGK2 promoter, a testis-specific promoter, was used to drive the expression of a green fluorescent protein (GFP) tagged to a mitochondrial localization signal (MLS). Cloning was performed using the standard method as described previously [

19]. The sequences of the construct were provided in the Supplementary data.

Validation of the Mitochondrial Localization Signal

HEK293 cells were transfected with the CMV-GFP-MLS plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s recommendation. After the transfection, cells were incubated for 24 hours and then analyzed for GFP expression and mitochondrial localization as previously described [

19]. The mitochondrial-specific dye, MitoTracker Red, was used to stain the mitochondria, and the colocalization was evaluated for the GFP signal to determine the mitochondrial targeting of the MLS.

Pronuclear Microinjection of Transgene Cassette and Oviductal Embryo Transfer

This method was performed as described previously by us [

20]. Transgenic mice were generated via pronuclear microinjection [

11,

8,

4]. For pronuclear microinjection, female mice were super-ovulated using PMSG and hCG followed by cohabitation with male mice. Oviducts were collected from donor mice (euthanized by cervical dislocation) and placed into Brinster’s Modified Oocyte Culture Media (BMOC) containing hyaluronidase (1 mg/mL). Embryos were collected and transferred to the 60 mm dish contain 100 µL drops of BMOC overlaid with mineral oil. Linearized transgene cassette (PGK2-MLS-EGFP) was prepared at a final concentration of 4ng/µl for microinjection. DNA was microinjected into the male pronucleus of fertilized eggs using Narishighe micromanipulator. Each manipulated embryo was then transferred into the pre-incubated BMOC containing dish and maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO

2 incubator. Embryos were incubated till 2-cell stage. Pseudo-pregnant female mice were generated by mating with vasectomized male mice. 2-cell stage embryos were transferred into the ampulla of the oviduct of pseudo-pregnant recipient mice. Approximately 20 microinjected embryos were transferred in the oviductal ampulla. After the gestation period (21 ± 2 days), recipient pups were born. Pups born were analyzed for transgene integration by PCR.

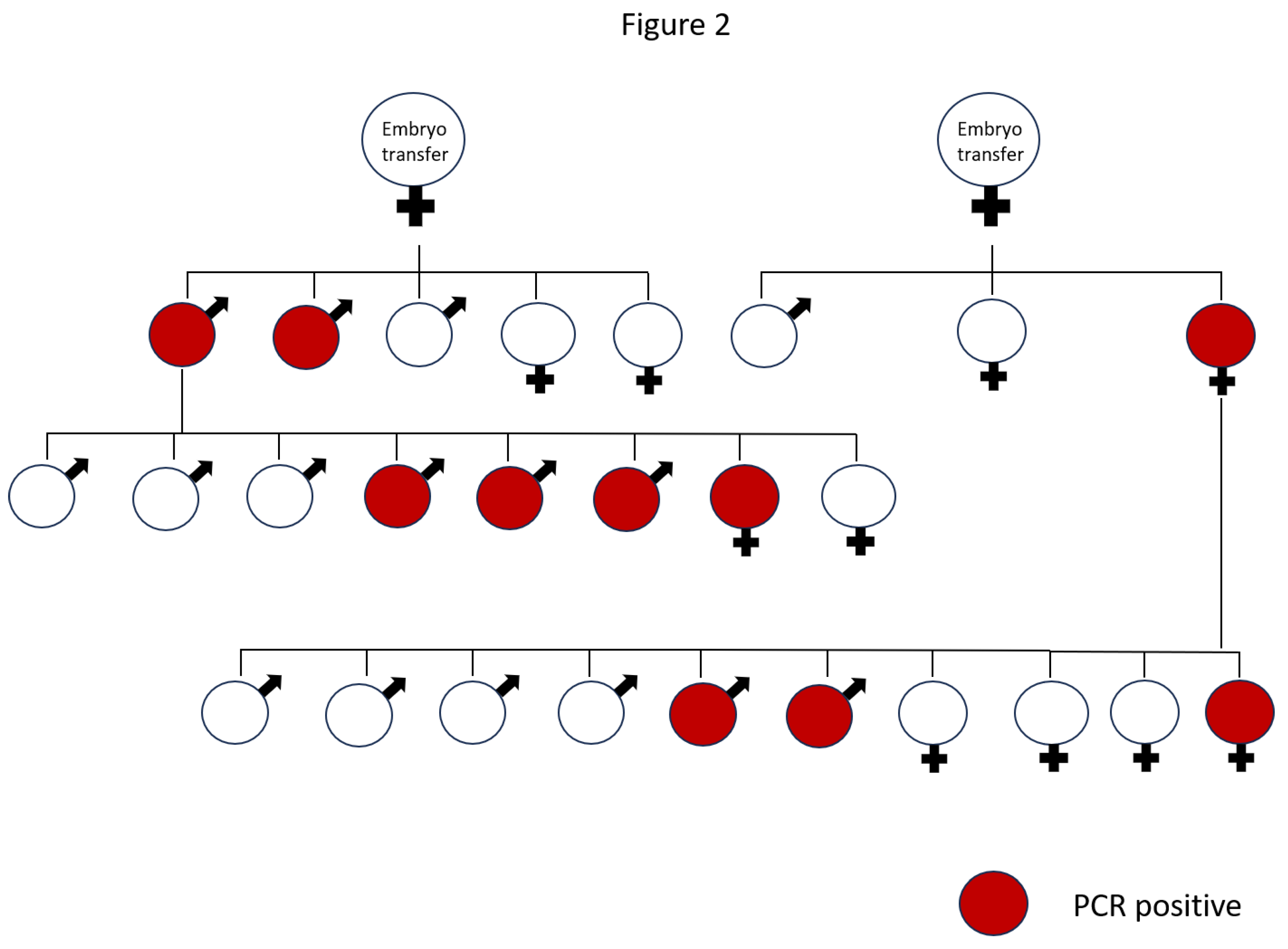

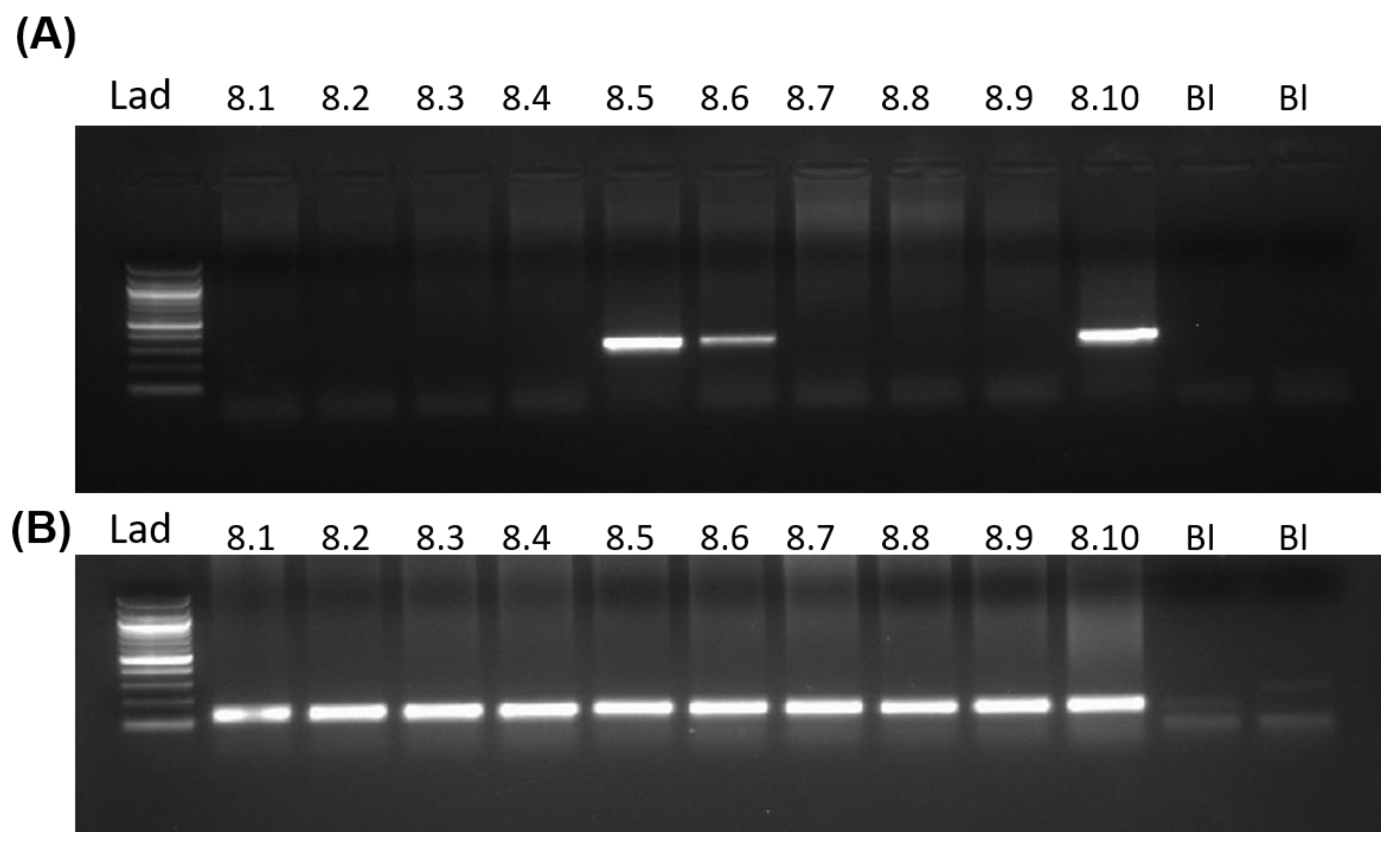

Establishment of Transgenic Lines

Two founder mice expressing PGK2-GFP-MLS were screened through PCR [

19,

29]. The founder mice were mated with wild-type females to establish the separate transgenic lines, and the transgene integration in the progeny was evaluated by PCR.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Fluorescence microscopy was employed to confirm GFP expression in the mitochondria of sperm cells. Sperm from transgenic mice were isolated by standard methods and immediately imaged using a confocal microscope [

19].

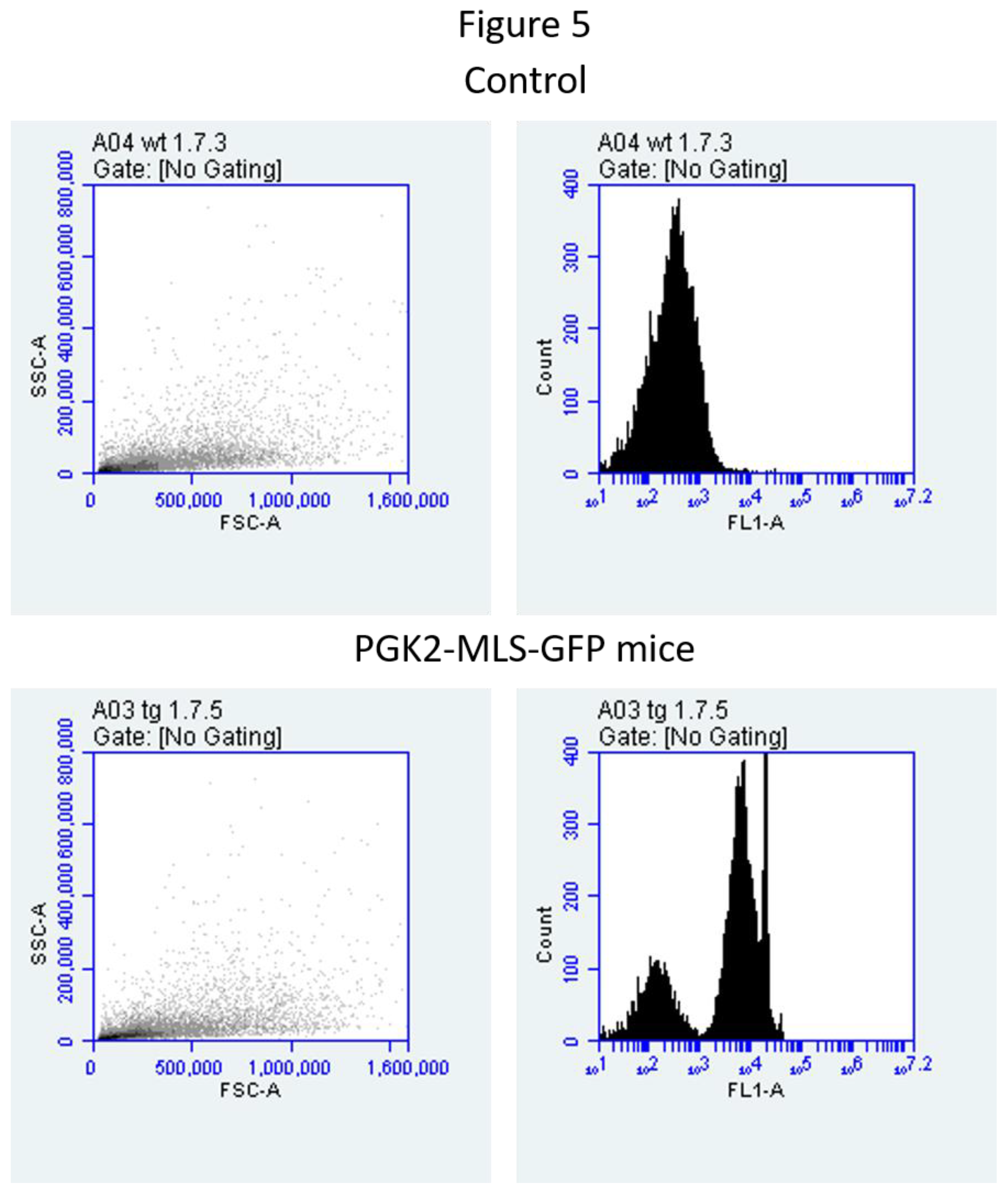

Flow Cytometry Analysis

The sperm were isolated from the cauda epididymis from the wild-type mice and transgenic mice. Samples were analyzed by a flow cytometer (FACS caliber, BD Biosciences). Data were collected and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar, Inc.) to assess the percentage of GFP-positive sperm [

19].

Results and Discussion

Validation of MLS Functionality in Hek 293 Cells

The MLS sequences for mitochondrial targeting were used previously [

25,

31,

5]. Previously, the importing signal of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit VIII was shown to be targeting the GFP to the mitochondria in Hela cells [

21,

22]. The mitochondrial targeting ability of the MLS of

COXVIII gene was validated by expressing the CMV-MLS-GFP construct in HEK 293 cells. We observed a colocalization of GFP with mitochondrial markers suggesting that the MLS was functional in our studies (

Figure 1B). As a control, we used the CMV-GFP construct without MLS.

Generation of Transgenic Mice

To determine the in vivo implications of MLS sequence in the germ line lineage, we generated two transgenic mouse lines using pronuclear microinjection. For this, we used the PGK2-MLS-GFP construct. The tissue-specific activity of the PGK2 promoter was previously demonstrated to drive post-meiotic gene expression in the male germline [

34]. We are providing a diagram of the generation of the transgenic line (

Figure 2). The transgene integration in the two different founders and in their progenies were confirmed by PCR (

Figure 3).

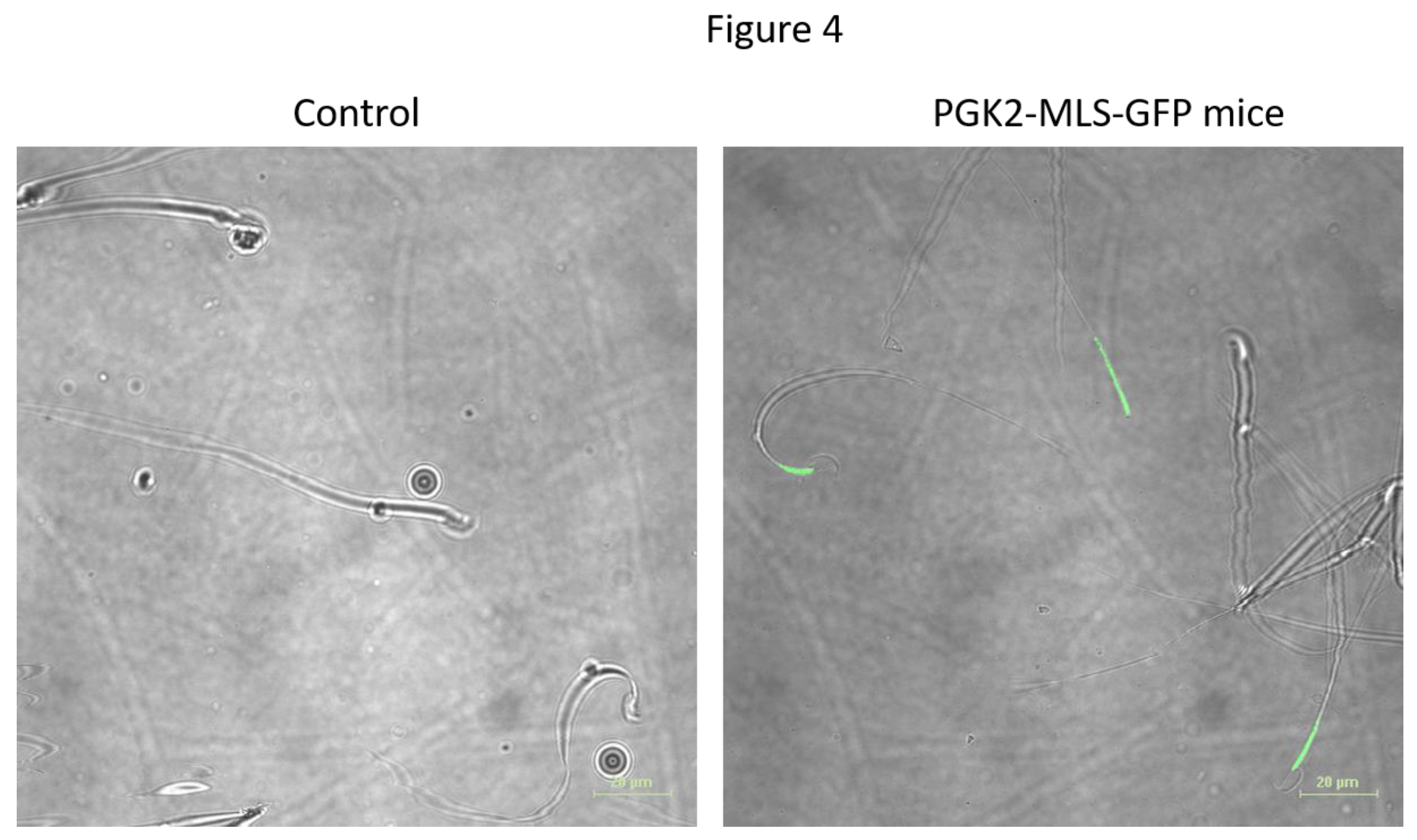

Localization of GFP in the Mitochondria of Sperm

Since, PGK2 promoter will drive the transgene in the male germ line, we evaluated the sperm of the transgenic mice. We performed the fluorescence microscopy to determine the expression of GFP fluorescence in the sperm. The GFP signal was observed in the middle piece of the mitochondria where the mitochondria are localized (

Figure 4). Mitochondria in the midpieces of the sperm are critical for energy production and the motility and previous studies suggest a link between mitochondrial dysfunction and male infertility [

18]. The expression of GFP in the mitochondria of the sperm do not affect its function [

30]. Here we demonstrated the functional importance of mitochondrial localization sequences in directing proteins to mitochondria of the sperm using a germ line specific promoter [

31,

5].

Analysis of GFP Expression by Flow Cytometry (FACS)

We performed the FACS analysis of sperm samples to validate the microscopy data. We observed that GFP-positive sperm in various transgenic mice, suggesting that the efficiency of the PGK2 promoter in directing mitochondrial GFP expression in vivo (

Figure 5). Our data also validated the microscopy data suggesting that the method is reproducible. This study may help in studies of mitochondrial health and dynamics in large populations of sperm cells [

18]. Our study provides a platform to investigate mitochondrial biology during spermatogenesis. The specificity of the PGK2 promoter ensures minimal ectopic expression, which is critical for accurate functional analyses [

34]. Such advancements address limitations of ubiquitous promoters in transgenic models. Mitochondria are vital for sperm function and is a major contributor to male infertility [

28]. Our studies will help to study the role of mitochondria in the development of the sperm.

Previously, various groups have shown the different fluorescent protein expression in the sperm in the transgenic mice [

25,

6,

32]. However, various constitutive promoters were used in these studies. The integration of a tissue-specific promoter with an MLS sequence enables precise visualization of mitochondrial architecture and bioenergetics in sperm in vivo. This approach addresses a critical gap in male reproductive biology, providing insights into mitochondrial dynamics in sperm development, motility, and fertilization [

15,

28]. This approach can be used to study the effect of various mutations caused by environmental stress on mitochondrial function, mitochondrial dynamics using advanced imaging techniques during spermatogenesis and the role of mitochondria in assisted reproduction technologies. These findings may have broad implications for mitochondrial research, particularly in male infertility and sperm development.

Author Contributions

Experiments were conceived and designed by B.S.P., H.S., and S.S.M. Experiments were performed by H.S., S.B., N.W. and B.SP. Data of the manuscript was analyzed by B.S.P, H.S. Manuscript was written and reviewed by B.S.P. and H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to all the staff of the Small Animal Facility. Thanks are due to Ram Singh, Dharamvir Singh and Birendar Roy for the technical assistance. We are grateful to the Director, NII for valuable support. We are grateful to Department of Biotechnology, Govt. of India, for providing the financial assistance under grants BT/PR11313/AAQ/01/376/2008, BT/HRD/35/01/01/2010 (TATA Innovation Award) and BT/PR10805/AAQ/1/576/2013. BSP was supported the Polish National Science Centre grant (2020/39/D/NZ5/02004). H.S. was supported by the Department of Biotechnology, Govt. of India grant (BT/PR46488/AAQ/1/886/2022). The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aitken, R.; Koppers, A.J. Apoptosis and DNA damage in human spermatozoa. Asian J. Androl. 2011, 13, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aitken, R.J.; Whiting, S.; De Iuliis, G.N.; McClymont, S.; Mitchell, L.A.; Baker, M.A. Electrophilic Aldehydes Generated by Sperm Metabolism Activate Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species Generation and Apoptosis by Targeting Succinate Dehydrogenase. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 33048–33060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amaral, A.; Lourenço, B.; Marques, M.; Ramalho-Santos, J. Mitochondria functionality and sperm quality. Reproduction 2013, 146, R163–R174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auerbach, A.B. Production of functional transgenic mice by DNA pronuclear microinjection. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2004, 51, 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, G.; Enkler, L.; Araiso, Y.; Hemmerle, M.; Binko, K.; Baranowska, E.; De Craene, J.-O.; Ruer-Laventie, J.; Pieters, J.; Tribouillard-Tanvier, D.; et al. Assigning mitochondrial localization of dual localized proteins using a yeast Bi-Genomic Mitochondrial-Split-GFP. eLife 2020, 9, e56649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrasso, A.P.; Tong, X.; Poché, R.A. The mito::mKate2 mouse: A far-red fluorescent reporter mouse line for tracking mitochondrial dynamics in vivo. Genesis 2017, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boguenet, M.; Bouet, P.-E.; Spiers, A.; Reynier, P.; May-Panloup, P. Mitochondria: Their role in spermatozoa and in male infertility. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2021, 27, 697–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, F.; Lacy, E. Introduction of a rabbit β-globin gene into the mouse germ line. Nature 1981, 294, 92–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danshina, P.V.; Geyer, C.B.; Dai, Q.; Goulding, E.H.; Willis, W.D.; Kitto, G.B.; McCarrey, J.R.; Eddy, E.; O'Brien, D.A. Phosphoglycerate Kinase 2 (PGK2) Is Essential for Sperm Function and Male Fertility in Mice1. Biol. Reprod. 2010, 82, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.; Hossain, T.; Eckmann, D.M. Mitochondrial dynamics involves molecular and mechanical events in motility, fusion and fission. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 1010232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, J.W.; A Scangos, G.; Plotkin, D.J.; A Barbosa, J.; Ruddle, F.H. Genetic transformation of mouse embryos by microinjection of purified DNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1980, 77, 7380–7384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Luo, Y.-X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, H.-Z.; Yu, Y. Potential of Mitochondrial Genome Editing for Human Fertility Health. Front. Genet. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, M.J.; Vijayaraghavan, S.; Fardilha, M. Signaling mechanisms in mammalian sperm motility†. Biol. Reprod. 2016, 96, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, J.M. Immunofluorescent localization of PGK-1 and PGK-2 isozymes within specific cells of the mouse testis. Dev. Biol. 1981, 87, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matilainen, O.; Quirós, P.M.; Auwerx, J. Mitochondria and Epigenetics – Crosstalk in Homeostasis and Stress. 2017, 27, 453–463. [CrossRef]

- McCarrey, J.R.; Berg, W.M.; Paragioudakis, S.J.; Zhang, P.L.; Dilworth, D.D.; Arnold, B.L.; Rossi, J.J. Differential transcription of Pgk genes during spermatogenesis in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 1992, 154, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otera, H.; Ishihara, N.; Mihara, K. New insights into the function and regulation of mitochondrial fission. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Cell Res. 2013, 1833, 1256–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.-J.; Pang, M.-G. Mitochondrial Functionality in Male Fertility: From Spermatogenesis to Fertilization. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.S.; Majumdar, S.S. An Efficient Method for Generation of Transgenic Rats Avoiding Embryo Manipulation. Mol. Ther. - Nucleic Acids 2016, 5, e293–e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, B.S.; Bhattacharya, I.; Sarkar, R.; Majumdar, S.S. Pubertal down-regulation of Tetraspanin 8 in testicular Sertoli cells is crucial for male fertility. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 26, 760–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuto, R.; Brini, M.; Pizzo, P.; Murgia, M.; Pozzan, T. Chimeric green fluorescent protein as a tool for visualizing subcellular organelles in living cells. Curr. Biol. 1995, 5, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzuto, R.; Brini, M.; De Giorgi, F.; Rossi, R.; Heim, R.; Tsien, R.Y.; Pozzan, T. Double labelling of subcellular structures with organelle-targeted GFP mutants in vivo. Curr. Biol. 1996, 6, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell, WMS and Burch, RL (1959) The principles of humane experimental technique. Methuen: London.

- Sandoval, H.; Yao, C.-K.; Chen, K.; Jaiswal, M.; Donti, T.; Lin, Y.Q.; Bayat, V.; Xiong, B.; Zhang, K.; David, G.; et al. Mitochondrial fusion but not fission regulates larval growth and synaptic development through steroid hormone production. eLife 2014, 3, e03558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shitara, H.; Kaneda, H.; Sato, A.; Iwasaki, K.; Hayashi, J.-I.; Taya, C.; Yonekawa, H. Non-invasive visualization of sperm mitochondria behavior in transgenic mice with introduced green fluorescent protein (GFP). FEBS Lett. 2001, 500, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkar, R.K.; Sharma, S.S.; Mandal, K.; Wadhwa, N.; Kunj, N.; Gupta, A.; Pal, R.; Rai, U.; Majumdar, S.S. Homeobox transcription factor Meis1 is crucial to Sertoli cell mediated regulation of male fertility. Andrology 2021, 9, 689–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinelli, J.B.; Haigis, M.C. The multifaceted contributions of mitochondria to cellular metabolism. Nat. Cell Biol. 2018, 20, 745–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesarik, J.; Mendoza-Tesarik, R. Mitochondria in Human Fertility and Infertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usmani, A.; Ganguli, N.; Sarkar, H.; Dhup, S.; Batta, S.R.; Vimal, M.; Ganguli, N.; Basu, S.; Nagarajan, P.; Majumdar, S.S. A non-surgical approach for male germ cell mediated gene transmission through transgenesis. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Duan, Y.; Chen, B.; Qiu, S.; Huang, T.; Si, W. Generation of Transgenic Sperm Expressing GFP by Lentivirus Transduction of Spermatogonial Stem Cells In Vivo in Cynomolgus Monkeys. Veter- Sci. 2023, 10, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakai, T.; Harada, Y.; Miyado, K.; Kono, T. Mitochondrial dynamics controlled by mitofusins define organelle positioning and movement during mouse oocyte maturation. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2014, 20, 1090–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, J.; Nishiyama, S.; Shimanuki, M.; Ono, T.; Sato, A.; Nakada, K.; Hayashi, J.-I.; Yonekawa, H.; Shitara, H. Comprehensive application of an mtDsRed2-Tg mouse strain for mitochondrial imaging. Transgenic Res. 2011, 21, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka, H.; Geyer, C.B.; Hornecker, J.L.; Patel, K.T.; McCarrey, J.R. In Vivo Analysis of Developmentally and Evolutionarily Dynamic Protein-DNA Interactions Regulating Transcription of the Pgk2 Gene during Mammalian Spermatogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27, 7871–7885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.P.; Stroud, J.; Eddy, C.A.; Walter, C.A.; McCarrey, J.R. Multiple Elements Influence Transcriptional Regulation from the Human Testis-Specific PGK2 Promoter in Transgenic Mice1. Biol. Reprod. 1999, 60, 1329–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zini, A.; de Lamirande, E.; Gagnon, C. Reactive oxygen species in semen of infertile patients: Levels of superoxide dismutase- and catalase-like activities in seminal plasma and spermatozoa. Int. J. Androl. 1993, 16, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).