Introduction

Infertility is a reproductive disorder defined as the failure to achieve clinical pregnancy 12 months after unprotected intercourse [

1,

2]. The World Health Organization estimates that 9% of couples worldwide struggle with fertility problems, 50% of which are caused by male factors.

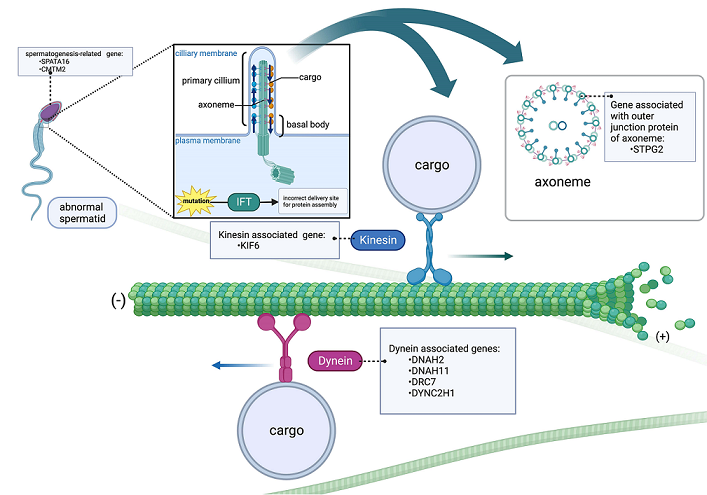

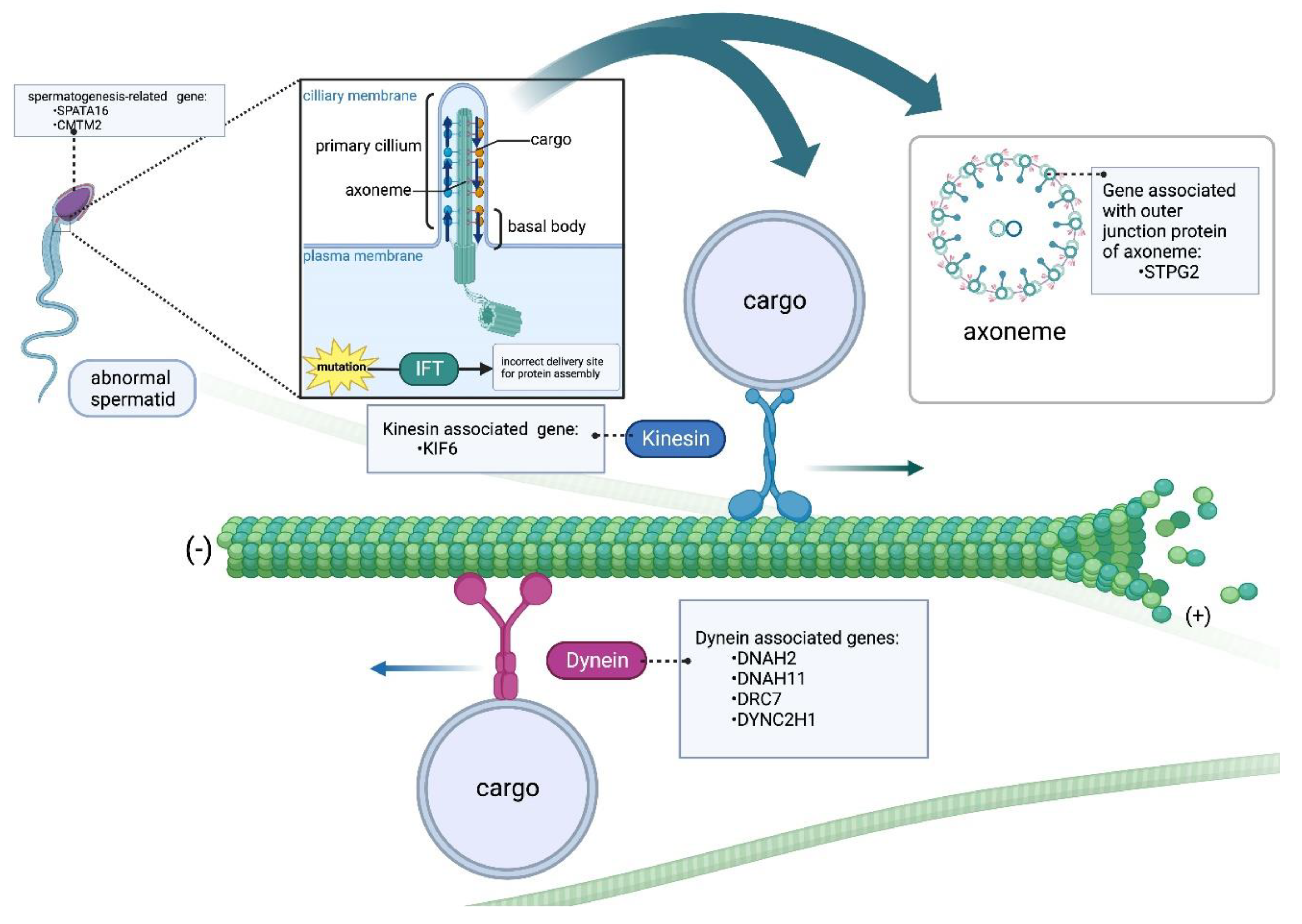

Microtubules (MTs) are the structural components of cells designed to participate in many essential processes such as cell division, intracellular transport and cell shape maintenance, and play a vital role in ensuring the normal formation and function of sperm. In spermatogenic cells, MTs are required for several processes, including the assembly of flagella in spermatids, and the production and maintenance of mature sperm motility [

3].

Motor proteins in MTs are specialized molecular motors that use adenosine triphosphate (ATP) as an energy source. These motors are responsible for transporting various cellular cargoes along MTs tracks, ensuring delivery of these cargoes to specific destinations within the cell, examples of such motor proteins include kinesins and dyneins [

4]. Movement in the outward or anterograde direction (from sperm head to tail) is directly facilitated by the microtubule motor protein kinesin-2. In contrast, cytoplasmic dynein 2 (also known as dynein 1b) promotes movement in an inward or retrograde direction [

5].

Furthermore, MTs ensure the successful division of cells during spermatogenesis [

6]. As the sperm tail develops, the matrix built within the centrosome of the spermatid anchors the MTs. Within this region, MTs play a crucial role in facilitating the movement of vesicles from the Golgi to the acrosome [

7]. MTs are also constituent elements of the sperm tail, the elongated flagella whose central axoneme protrudes from the basal body located posterior to the nucleus. To enable sperm motility, the movement of the inner and outer duplex MTs of the sperm flagella is dependent on the energy generated by the hydrolysis of ATP [

8].

Genetic mutations that disrupt MTs function during sperm development may cause male infertility [

9]. Mutations in

TSARG4 (Testis and spermatogenesis-associated gene 4) capable of impairing sperm head formation [

10]. Mutations in

SPATA6 can aberrantly remodel the sperm cell head while interfering with head-tail assembly [

11]. Mutations in the protein of katanin reveal a defective formation of the central microtubules in the flagellar axoneme, which is critical for male fertility [

9,

12]. Mutations of the N-terminal and C-terminal of

DNAH1 can have different effects on the axoneme structure of human spermatozoa. [

13]. More studies also have shown that the regulation of MT dynamics is critical for male infertility (azoospermia and oligospermia) [

14,

15].

This study utilized targeted NGS panel and WES to explore male infertility (MI)-associated SNPs to understand its causes and search for human azoospermia and oligospermia gene clusters that lead to abnormal sperm function. The aim of this study was to identify microtuble-related genes (such as KIF6 and DRC7) and their properties in sperm cell function, motility, intracellular trafficking, differentiation and cell division. Assessment of microtubules dynamics is an important aspect to fully understand the correlation between genes and male infertility. Further research in this area may improve diagnosis, treatment, and interventions for male infertility.

Materials and Methods

Patients and controls

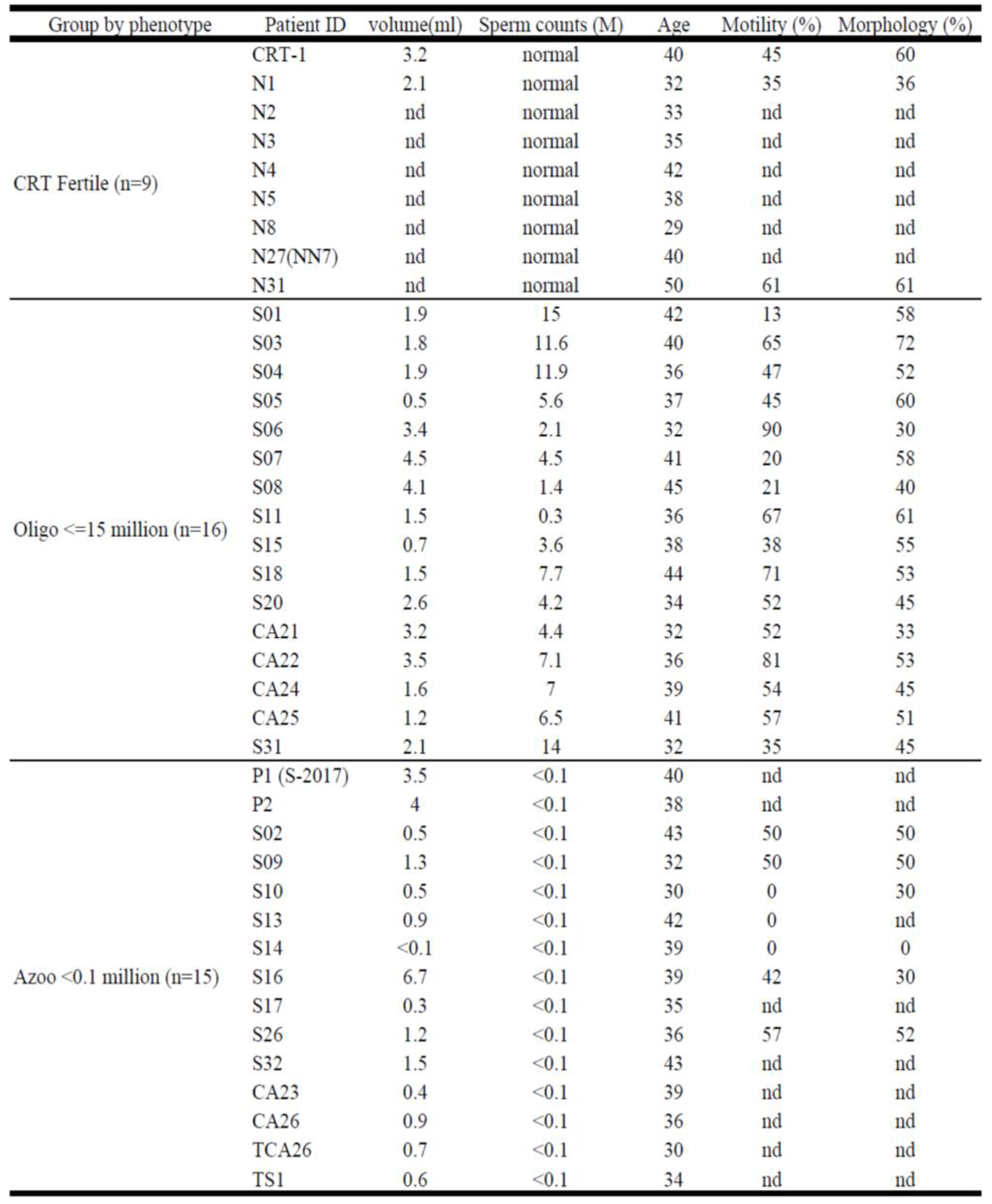

From July 2018 to Jan 2020, 31 infertile men between 30 and 45 years old were recruited during routine infertility treatment at the Reproductive Medical Center, Tri-Service General Hospital and Taipei City Hospital-Renai Branch (Taipei, Taiwan). The infertile men were included and their semen analyzed (

Table 1), we divided them into two groups based on sperm concentration in semen as azoospermia (<0.1million/ml, n=15), and oligozoospermia (0.1-15 million/ml, n=16). The fertile controls (n=9) were men who had children in the previous 3 years. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Taipei City Hospital Research Ethics Committee (protocol Ver2.0-1090414) (Taipei, Taiwan) and all the patients provided written consent prior to enrollment in the study.

Table 1.

Thirty-one (31) infertile men with no or low semen sperm count (<15 million/mL) and nine fertile men as controls were included in this study.

Table 1.

Thirty-one (31) infertile men with no or low semen sperm count (<15 million/mL) and nine fertile men as controls were included in this study.

Semen analysis

Patients refrained from sexual activity for 3 to 5 days, then semen samples were collected in sterile containers by masturbation. The semen is kept at room temperature for 15 to 30 minutes to allow for it to liquefy. After the process of liquefaction, the total volume of the semen and the sperm concentration, motility, and shape were documented in accordance with the World Health Organization Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen, Fifth Edition. Semen volume less than 1.5 mL, sperm concentration less than <15 million/mL, motility less than 40% or progressive motility (PR) plus non-progressive motility (NP) less than 32%, and normal morphology in less than 30% were considered abnormal

Y chromosome microdeletion (YCMD) examination

The Y chromosome's long arms (Yq) harbor numerous coding genes responsible for regulating spermatogenesis and testes development. Microdeletions within the AZF (azoospermia factor) region can lead to a diverse range of infertility phenotypes. To investigate these deletions, Yq microdeletion analysis was conducted by amplifying the AZFa, AZFb, and AZFc loci along with their associated sequence-tagged sites (STSs) markers. YCMD are identified in approximately 13% of men with nonobstructive azoospermia and 5% of men with severe oligozoospermia. Employing the YCMD assay (Promega), a PCR-based blood test, we assessed the presence or absence of sequence-tagged sites (STSs) as well as clinically relevant microdeletions (Figure S1).

YCMD testing is a prevalent method for evaluating male infertility. The Y chromosome's long arm (Yp) comprises of three azoospermia factor regions prone to deletions: AZFa, AZFb, and AZFc. Many Y chromosome genes are exclusive to spermatogenesis, and deletions within these regions, particularly at Yp's AZFc, can disrupt sperm formation. While Y-chromosome microdeletions and the genetic underpinnings of male infertility have garnered significant research attention, the clinical implications within this realm remain scattered and lack a unified consensus.

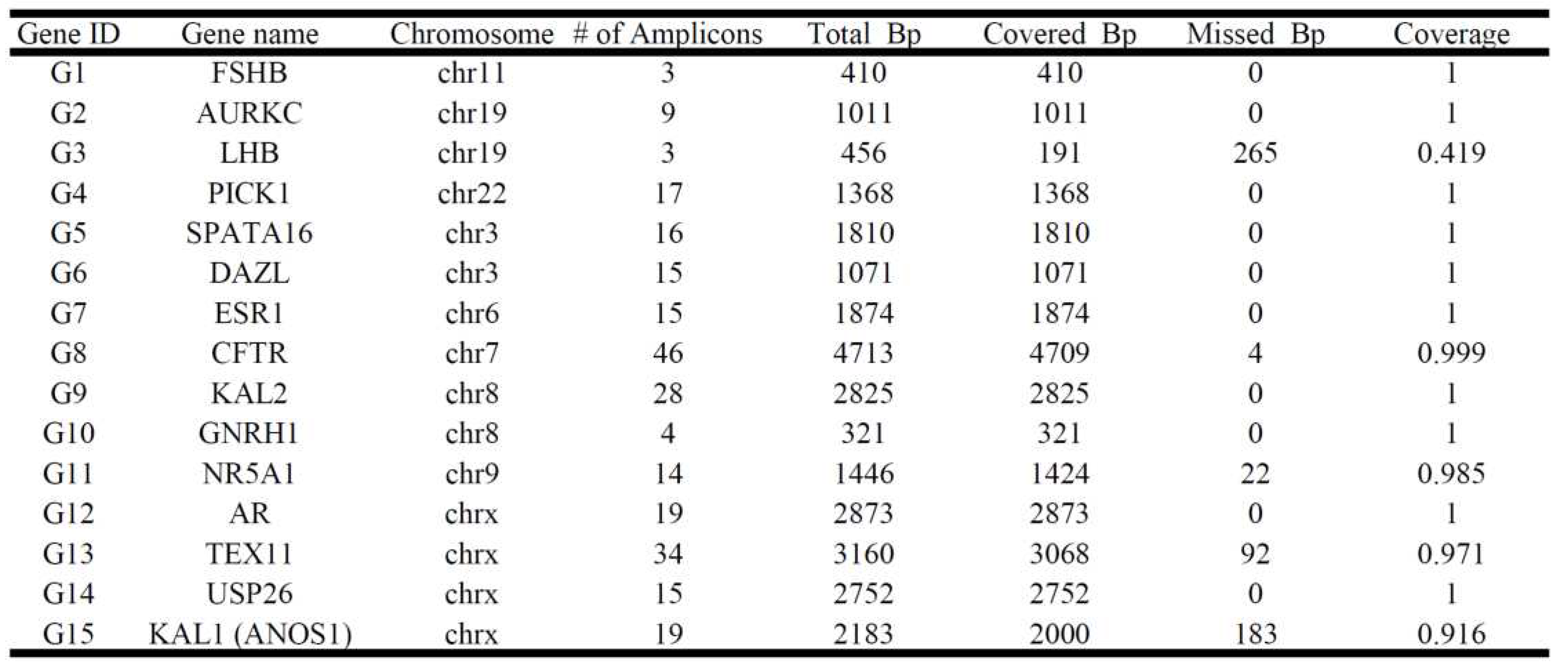

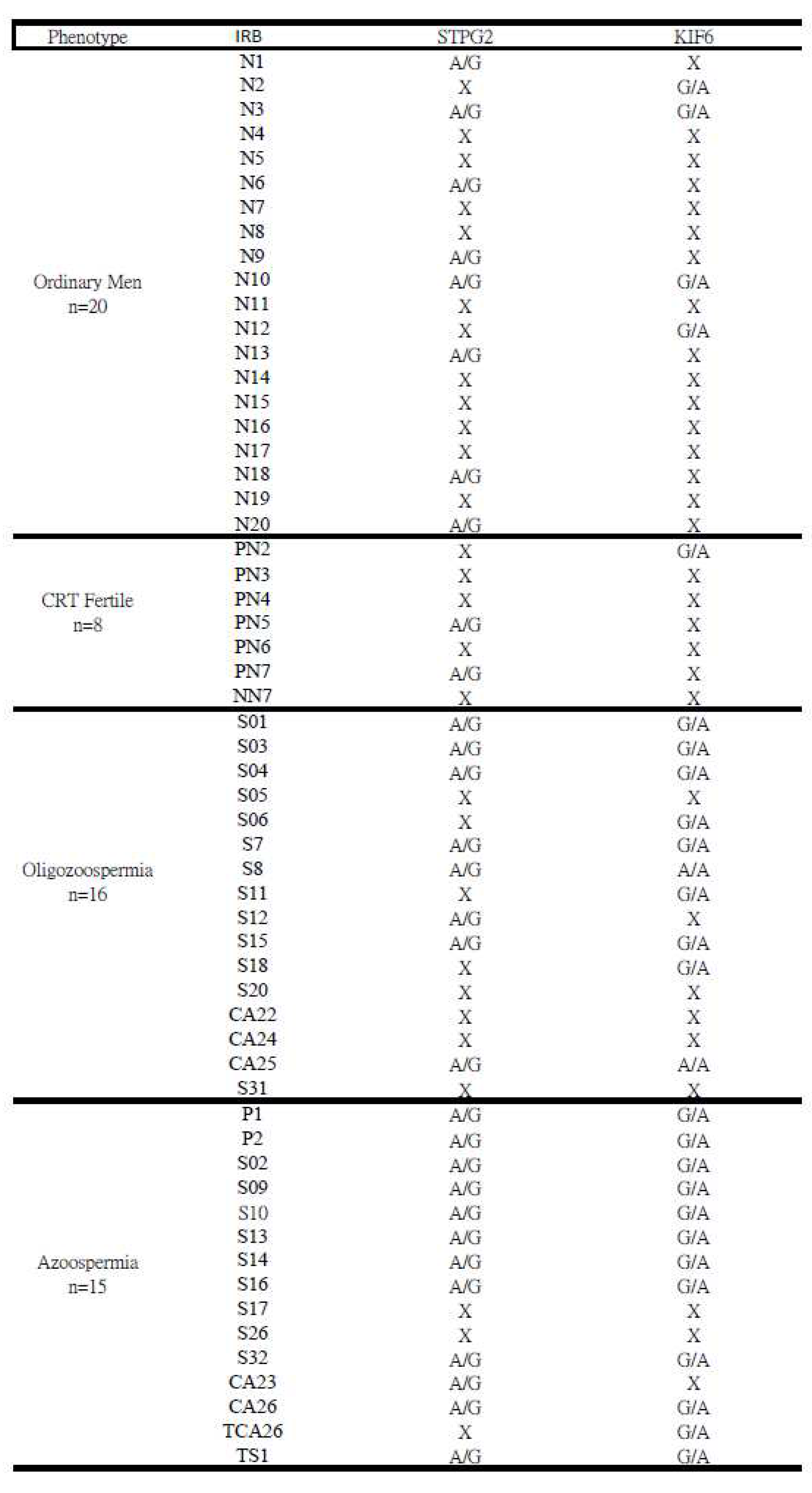

Targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) panel

The amplicon libraries of 8 infertile males and 2 fertile controls were constructed using the Ion AmpliSeq™ Library Kit v2.0 (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions, and using the Ion Xpress™ Barcode Adapter Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific) for barcode adapter ligation. The patient's genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using the MagPurix DNA extraction kit (Taipei, Taiwan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The custom Ion Ampliseq NGS panel was designed with 257 amplicons (IAD142966_182, 131+126 primer pairs containing 27, 707bps) to ensure comprehensive coverage of 15 gene targets previously associated with male infertility (

Table 2). Massively parallel sequencing was performed in the GeneStudio S5 Sequencing System (ThermoFisher Scientific) to cover exonic regions of genes, increasing the average sequencing depth by more than 1000-fold. All reads were further analyzed by Torrent Suite™ software (ThermoFisher Scientific) with the human reference genome (GRCh37.p5/hg19). All synonymous and non-altered protein splice site variants were then removed, leaving only the coding gene for comparison.

Table 2.

The customized Ion Ampliseq NGS panel of infertility included 15 spermatogenesis-related genes with 257 amplicons (IAD142966_182, 131+126 primers). We performed a massive parallel sequencing on an Ion S5 semiconductor sequencer (S5, ThermoFisher Scientific).

Table 2.

The customized Ion Ampliseq NGS panel of infertility included 15 spermatogenesis-related genes with 257 amplicons (IAD142966_182, 131+126 primers). We performed a massive parallel sequencing on an Ion S5 semiconductor sequencer (S5, ThermoFisher Scientific).

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) and Variant analysis

WES is a widely used next-generation sequencing (NGS) method that involves sequencing the protein-coding regions of the genome. We selected 15 samples of participants (8 cases and 7 controls) extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes by using the MagPurix DNA extraction kit, processed according to Illumnia TruSeq DNA Exome Kit guidelines and fragmented 100ng of genomic DNA into 150bp inserts by Covaris M22. Briefly, fragment gDNA is ligated with adapters and enriched by PCR. After PCR amplification, the probe captures the fragments and is then amplified to create the WES library. The Nextseq 550 (Illumnia) was used for WES. Then, those sequenced reads were aligned to the human reference genome (hg38) by using NGS Core Tools/FASTQ mapping with CLC Genome Workbench 23.0.4. We filtered out and compared those detected variants with SNPs database(p<0.05). SNPs profiles were assessed by using resequencing analysis/variant comparison module of CLCs. The cases (n=8) were compared with controls (n=7), and we put emphasis on those genes significantly expressed in testis tissue on the basis of NCBI HPA RNA-seq normal tissue.

Validation by Sanger sequencing

After the genes of interest were identified using targeted NGS sequencing and WES, Sanger sequencing was applied to examine the potential SNPs of the CFTR, SPATA16, KIF6, STPG2, DRC7 genes. The product of targeted genes was gained by using PCR (Proflex, ThermoFisher Scientific) with a pair of primers, the sequences are listed in Table S1. Sanger sequencing of Applied Biosystems Genetic analyzer (3130X, MA, USA) was performed on the infertile cases and fertile controls to validate the findings of the candidate SNPs by WES and targeted NGS. Sanger sequencing was also performed on an additional group of infertile men and fertile controls.

In silico evaluation workflow

The

in silico evaluation of the pathogenicity of nucleotide changes in exons was performed using CADD (Combined Annotation Dependent Depletion), SIFT (Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant), and PolyPhen2 (Polymorphism Phenotyping) (applied in

Table 5, Table S3). CADD is a tool for scoring the deleteriousness of single-nucleotide variants in the human genome, with a cutoff score of 15 and higher values indicating more deleterious conditions. The PolyPhen-2 score predicts the likely impact of amino acid substitutions on human protein structure and function, with scores ranging from 0.0 (tolerated) to 1.0 (deleterious). SIFT predicts whether amino acid substitutions are likely to affect protein function based on scores and qualitative predictions (either 'tolerated' or 'deleterious'). Minor allele frequencies (MAFs) were examined in the genome aggregation database gnomAD and Taiwan Biobank (TWB). When discussing MAF, we should recognize that variant allele frequency is basically a fraction, the variant positivity rate divided by the total number of alleles screened.

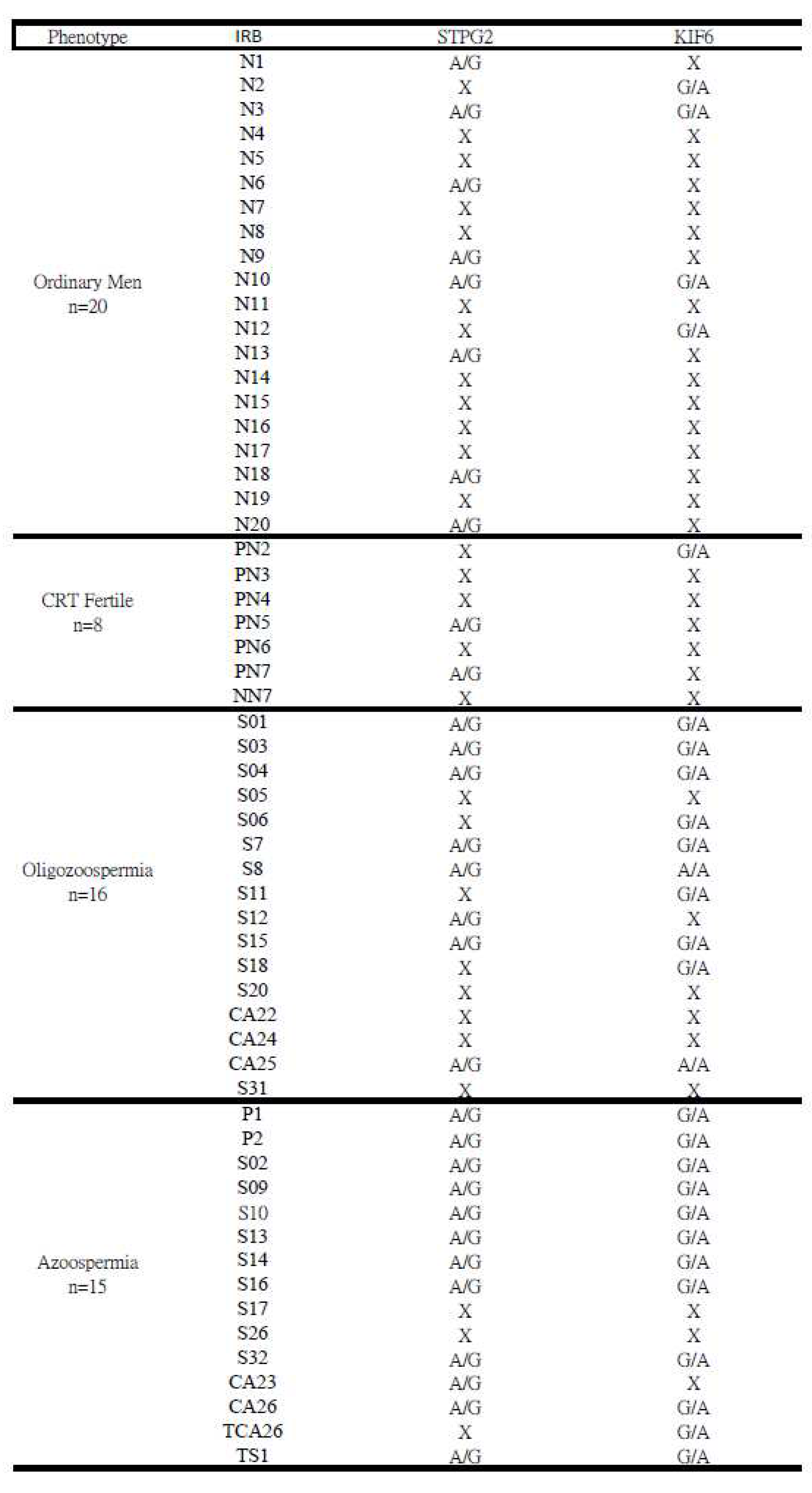

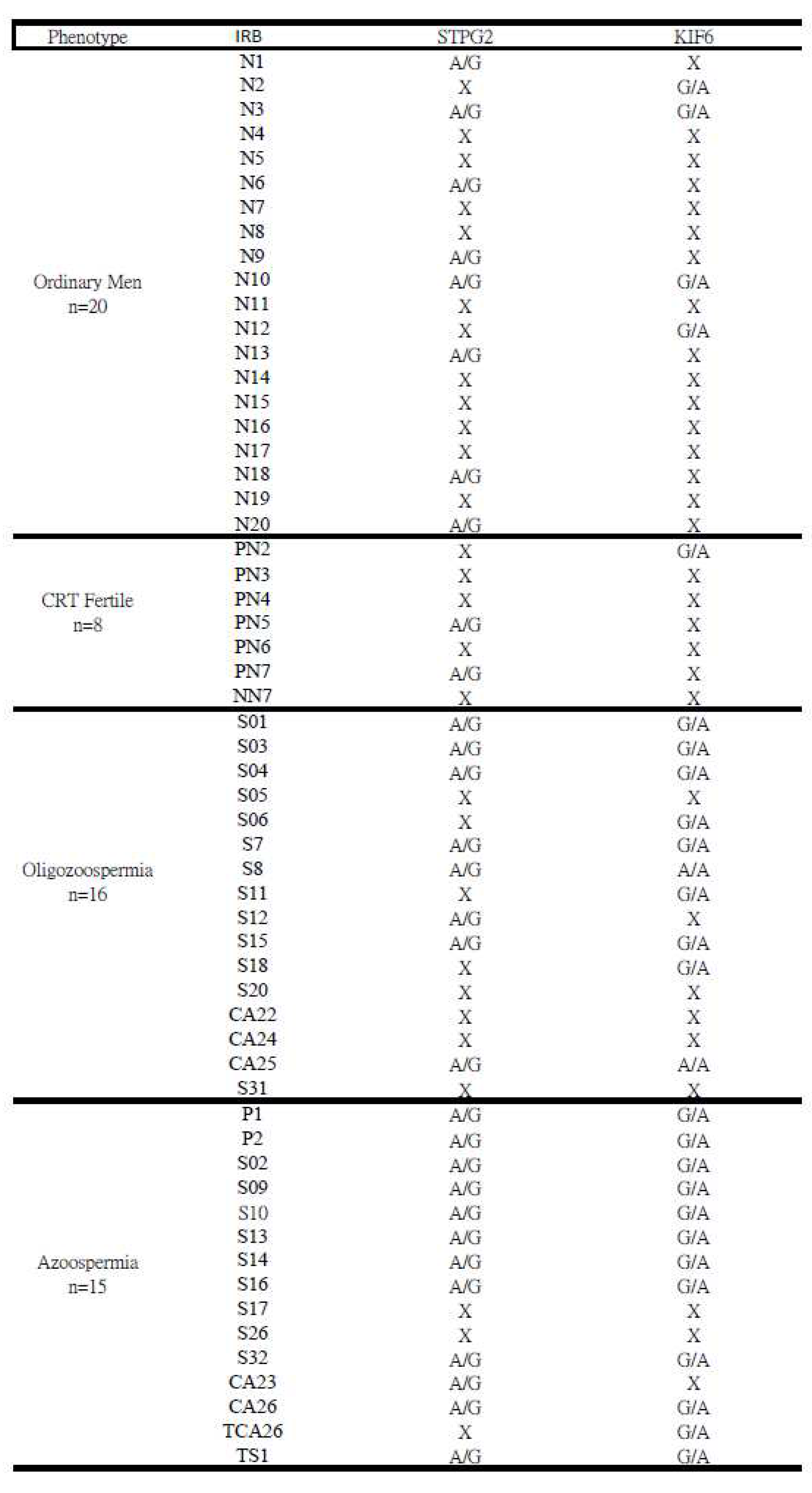

Table 5.

The occurrence of mutations on the STPG2 and KIF6 genes was valided through Sanger sequencing. Thirty-one (31) infertile men with no or low semen sperm count (<15 million/mL), twenty ordinary men and nine fertile men.

Table 5.

The occurrence of mutations on the STPG2 and KIF6 genes was valided through Sanger sequencing. Thirty-one (31) infertile men with no or low semen sperm count (<15 million/mL), twenty ordinary men and nine fertile men.

Results

Semen analysis

All samples were examined in accordance to the World Health Organization guidelines. After macroscopic and microscopic observations on sperm parameters, only sperm concentration is an evident factor. Patients were divided into three groups based on sperm concentration, fertile controls (>15 million/mL), oligozoospermia (<15 million/mL), and azoospermia (<0.1 million/mL). The sperm of infertile men and fertile controls were examined and summarized in

Table 1. There were 16 patients categorized into the oligozoospermia group, 15 patients categorized into the azoospermia group, and 9 fertile controls. The mean age of fertile controls, oligozoospermic, and azoospermic patients were 37, 38, and 37 years old, respectively. Semen volumes in oligozoospermia and azoospermia were abnormal, especially in azoospermia (1.64+/-1.8, n=15).

Y chromosome microdeletion

By employing the YCMD assay (Promega), a PCR-based blood test, the presence or absence of sequence-tagged sites (STSs) became assessable alongside clinically relevant microdeletions (Figure S1). The Y chromosome's long arms (Yq) contain numerous coding genes responsible for regulating spermatogenesis and testes development. Notably, Y chromosome microdeletions (YCMD) are detected in around 13% of men with nonobstructive azoospermia and approximately 5% of men experiencing severe oligozoospermia. Within the framework of this study, YCMD analysis was carried out on a group of 8 infertile men, comprising 4 with oligozoospermia and 4 with azoospermia (Figure S2). Interestingly, notable AZFc deletions were observed solely in two azoospermic patients (S02 and S-2017). Microdeletion of AZF-STS was not identified in 2 of the infertile patients, while others exhibited certain degrees of microdeletion (Table S2). The extent was insufficient to imply a direct cause-and-effect relationship.

Variant’s analysis and Validation in targeted NGS

Targeted sequencing was performed on 8 infertile men and 2 fertile controls. SNPs were identified from the 15 spermatogenesis-related genes (

Table 2). Primers of

SPATA16, CFTR and

ESR1 genes were used for Sanger validation of NGS variants, the sequences are shown in Table S1.

SPATA16 mutations at three SNPs (

rs16846616), (

rs1515442), and (rs1515441) were identified in all azoospermic patients and one oligozoospermic patient, while no mutation displayed in fertile (

Table 3).

CFTR mutation at one SNP (

rs213950) was identified in 7 of 8 infertile men and 1 of 2 fertile controls, though when verified with Sanger sequencing, no fertile controls displayed this

CFTR mutation (

Table 4). The remaining genes seemed to correlate more poorly. The mutations at SNPs of

TEX11 (

rs4844247),

LHB (

rs4146251380),

USP26 (

rs61741870) and (

rs41299088), and

ANOS1 (

rs2229013) were displayed in only 1 of 8 infertile men.

NR5A1 (

rs1110061) and

ANOS1 (

rs808119) mutations were present in both fertile controls.

TEX11 (

rs6525433) displayed mutations in only 2 of 8 infertile men. GNRH1 displayed mutations in 5 of 8 infertile men and 1 of 2 fertile controls, however this was not validated with Sanger sequencing (

Table 4).

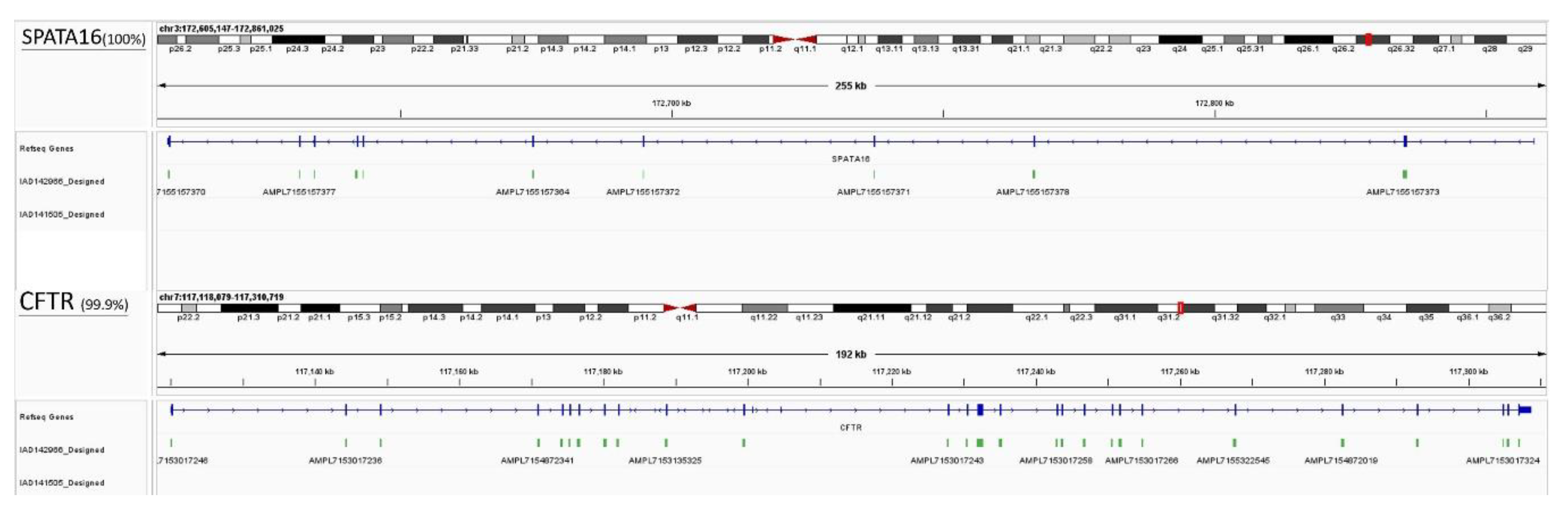

ESR1 displayed mutations in 5 of 8 infertile men and none in fertile controls and could be further explored as a gene target for male infertility. The results of the Sanger sequencing examining the

SPATA16 and

CFTR genes are presented on

Table 4 and

Figure 2. No fertile controls displayed the

CFTR mutation while 6 of 16 oligozoospermic and 10 of 15 azoospermic patients did, suggesting that

CFTR may be associated with male infertility (oligozoospermia and azoospermia). The mutations of

SPATA16 at two SNPs (rs16846616) and (rs1515411) occurred simultaneously, affecting 12 of 15 azoospermic, 6 of 16 oligozoospermic, and 2 of 8 fertile control patients. The mutation of

SPATA16 at one SNP(

rs1515442) affected 9 of 15 azoospermic, 1 of 16 oligozoospermic, and none of the fertile control patients. The

SPATA16 mutations appear to be associated with azoospermia. Three nearby SNPs (rs1515442), (rs1515441), and (rs16846616) in

SPATA16 were shown to have 4~9.6-fold higher mutation incidence in azoospermia compared to oligozoospermia while

CFTR was only 1.8-fold higher (

Figure 2).

Using CADD, SIFT, and PolyPhen2, we performed an in silico evaluation of the predicted pathogenicity of SPATA16 and CFTR mutations. In terms of CADD, the SPATA16 SNP was identified as a deleterious variant. Their values were 15.67, 19.12, and 22.2, which surpassed the deleterious variant cutoff of 15 (Table S3). They are also deleterious in SIFT. Only one nucleotide variant of SPATA16 (rs1515442) appeared benign in PolyPhen2. Overall, SPATA16 mutations at two SNPs (rs16846616 and rs1515441) are expected to be deleterious. MAF was examined in gnomAD and TWB, and the results are shown in Table S3. Two SNPs (rs16846616) and (rs1515411) of SPATA16 had lower MAF frequencies, 13.1%, and 11.9%, respectively in genomAD compared with TWB (32.8 and 32.5%). Interestingly, in our study in Taiwan, SPATA16 SNPs (rs16846616) and (rs1515441) co-occur at an 80% higher frequency in azoospermic patients. (Table S3).

Table 3.

The point mutation of genes in infertile men showed in red square (▓) ; the point mutation of genes in fertile men showed in black square (▓). (Azoo: azoospermia; Oligo: oligozoospermia)

Table 3.

The point mutation of genes in infertile men showed in red square (▓) ; the point mutation of genes in fertile men showed in black square (▓). (Azoo: azoospermia; Oligo: oligozoospermia)

Table 4.

The incidence of rs1515442, rs1515441 and rs16846616 on the SPATA16 gene by using Sanger sequencing.

Table 4.

The incidence of rs1515442, rs1515441 and rs16846616 on the SPATA16 gene by using Sanger sequencing.

SNPs of microtubule-associated genes in WES

Based on the variant comparison data (p<0.05) from CLC cases and controls, we have provided a detailed list of 15 SNPS in 13 candidate genes with significant expression in testicular tissues, including KIF6, STPG2, DRC7, NEK2, TRIM49, CATSPER2, CMTM2, SART3, DYNC2H1, CCDC168, BORCS5, TPTE, and RADIL. Among these, certain genes exhibit a high global Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) (>0.3) and a higher mutation rate in controls (>0.3). The genes with high MAF and mutation rate in controls, include TRIM49, CCDC168, TPTE, and RADIL, which might lead to an apparent elevated mutation rate in controls as well. The mutation rates and MAF for these genes in both cases and controls are presented in Table S4.

Variant analysis and Validation in WES

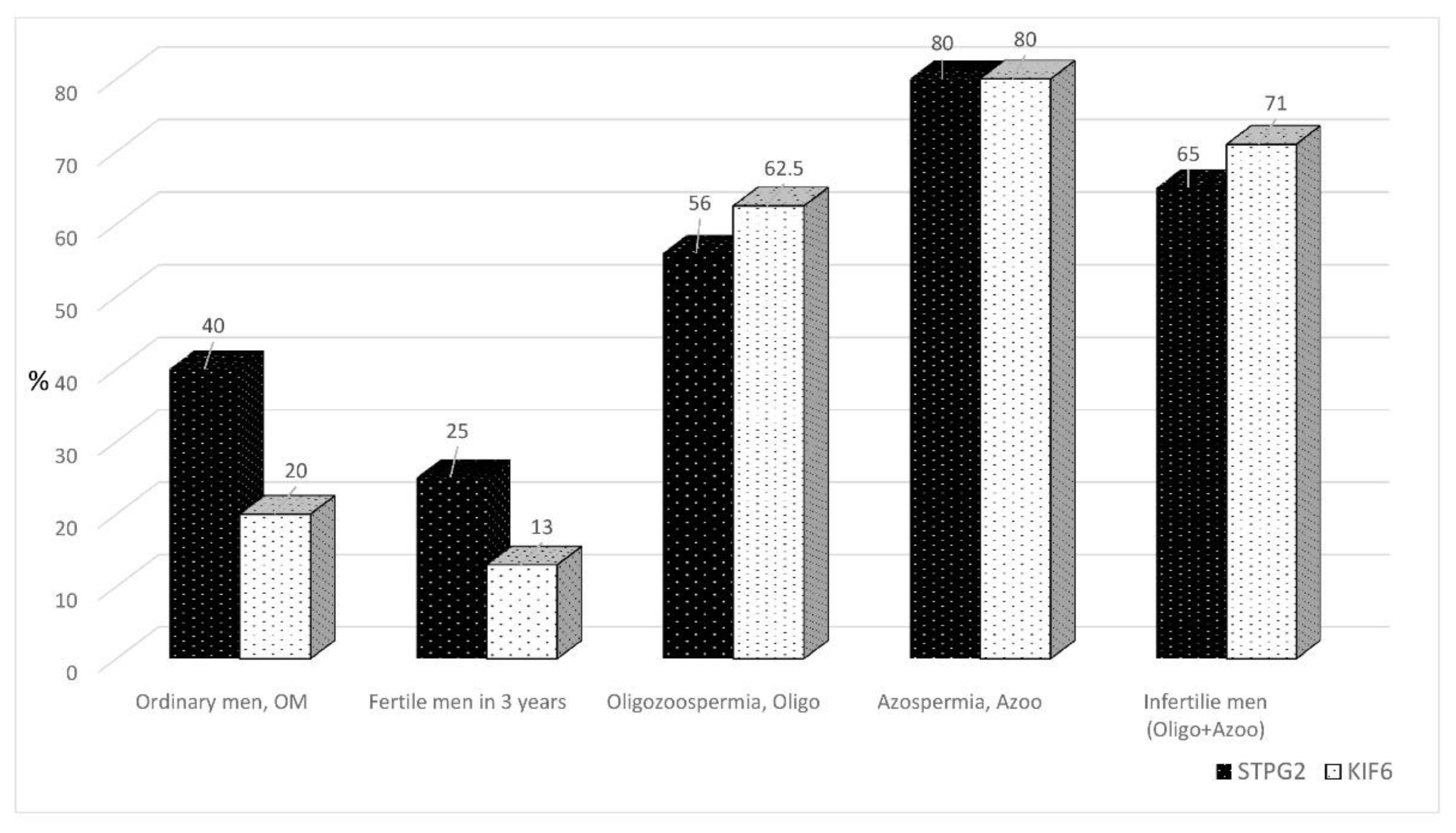

We selected two candidate genes,

KIF6 and

STPG2, from the pool of 60 candidates for Sanger sequencing validation. Sanger sequencing was employed to confirm the presence of SNPs on

KIF6, and

STPG2, facilitating a gene comparison between infertile and fertile men (

Table 5). In the case of

KIF6, 1 out of 8 controls exhibited mutation, whereas 22 out of 31 cases harbored mutations. Similarly, for

STPG2, there were 2 mutations among the 8 controls and 20 mutations among the 31 cases. Furthermore, in the

KIF6 gene, both A/A and G/A types of SNPs were observed (Figure S4). Upon comparing infertile men to fertile men (fertile within 3 years), the occurrence of SNPs on the

KIF6 gene appeared to be notably higher by a multiple of 5 (as shown in

Figure 3).

Using CADD, SIFT, and PolyPhen2, we conducted an in silico evaluation of the predicted pathogenicity of 13 mutations. In terms of CADD scores, 5 SNPs surpassed the deleterious variant cutoff of 15 (Table S4), namely STPG2 (rs17558183), NEK2, DYNC2H1, BORCS5, and TPTE. Among them, BORCS5 (CADD score: 29.9) and STPG2 (CADD score: 25.6) exhibited the highest scores. When considering SIFT predictions, BORCS5, STPG2, DRC7, and CATSPER2 were classified as deleterious variants. Within the framework of PolyPhen2 analysis, STPG2 (rs17558183), TRIM49, BORCS5, and TPTE were designated as possibly damaging, suggesting that alterations in these amino acids might disrupt protein structure. Minor allele frequency (MAF) was assessed both globally and specifically in East Asian populations (MAF_eas), with the results also summarized in Table S4. Notably, KIF6 (MAF: 0.04), BORCS5 (MAF: 0.06), DRC7 (MAF: 0.24), and STPG2 (MAF: 0.39) were listed in global MAF. It is worth highlighting that STPG2 exhibited a nearly 40% mutation rate, despite demonstrating a favorable case-to-control ratio (88/14) in whole exome sequencing (WES) data. However, this high mutation frequency in STPG2 could impact its potential as a candidate diagnostic marker. Additionally, it's noteworthy that KIF6 displayed significant differences in both global MAF (4%) and MAF_eas (25%), indicating a higher mutation rate in East Asian male populations. Interestingly, in our Taiwan study, the KIF6 SNP (rs2273063) and STPG2 (rs3809611) co-occur in 80% mutation rate in azoospermia and oligozoospermia patients with 20% MAF in ordinary men of Taiwan by Sanger sequencing.

Discussion

Genetic screening to identify genetic mechanisms of spermatogenesis failure in infertile men has become of clinical importance. These results not only allow to determine the etiology but also prevent the iatrogenic transmission of genetic defects to offspring through assisted reproductive techniques. These goals pose enormous challenges to reproductive medicine. In this study, we found some MI-related genes associated with male infertility. Through targeted NGS, we extensively examined 15 candidate genes involved in spermatogenesis (257 amplicons, 27707bp) within a cohort of unrelated Taiwanese infertile men (n = 8) (see

Table 2). Building upon previous studies, we confirmed the critical roles of

SPATA16 in globozoospermia and

CFTR in obstructive oligozoospermia or azoospermia. Notably, our findings provide further support for mutations in

SPATA16 and

CFTR genes being associated with non-obstructive oligozoospermia and azoospermia with normal morphology. Intriguingly, we established a strong correlation between

SPATA16 and azoospermia in our patient group. Additionally, our study raises questions about the implications of ESR1 and GnRH1 gene mutations in male infertility, which warrant more in-depth investigation.

Microtubule-associated genes affect spermatogenesis by variants analysis

KIF6 (kinesin family member 6) gene encodes motor proteins, including kinesins and dyneins, that play crucial roles in intracellular transport and cellular movement. Their activity is particularly important in cellular divisions during spermatogenesis and sperm motility. [

16,

17]. The two C-terminal tail domains interact with transported cargo through adapters and are connected to the head by a filamentous coiled stem that oligomerizes and regulates dynamics of microtubule [

18,

19,

20,

21]. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP, rs2273063) in the

KIF6 gene was identified through Illumina TruSeq whole exome sequencing (WES). This SNP had a higher prevalence in cases (87.5%) compared to controls (0%). Consequently, we validated SNPs by Sanger sequencing, which demonstrated that mutations in infertile cases were five times higher (0.65; 13/20) than in fertile controls (0.13; 1/8). Additionally, we performed a random sampling in ordinary men to estimate the mutation frequency of typical men in Taiwan (0.2; 4/20), contrasting it with the Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) (0.04; Table5). This reveals that the incidence of

KIF6 SNPs in collected infertile men in Taiwan is 16.25 times higher than the global MAF, and 3.25 times higher than the ordinary men in Taiwan. Based on Sanger sequencing data, the frequencies observed in our cases and controls suggest that

KIF6 mutations account for 60% of azoospermia cases and 50% of oligospermia cases, respectively. This underscores a greater occurrence of infertility among men (with azoospermia and oligospermia) compared to fertile men (Table4). Notably, its variant SNPs (A/G and A/A) may exhibit potential for genetic diagnosis and serve as markers for the progression of spermatogenesis (Fig. 2).

DRC7 (dynein regulatory complex subunit 7) is predicted to play a role in flagellated sperm motility, which aligns with its involvement in regulating ciliary motility [

22,

23]. Moreover,

DRC7 in flagellated sperm motility, as well as its potential involvement in spermatogenesis and the development of sperm cells [

24]. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP, rs3809611) in the

DRC7 gene was identified through Illumina TruSeq whole exome sequencing (WES). The mutation rate of the

DRC7 gene is reported to be 75%, which is lower than the mutation rate of the

KIF6 gene you mentioned earlier. The

DRC7 and

KIF6 genes were the only two genes within the control group that exhibited no mutations. The

DRC7 gene has the lowest global Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) among all candidate genes, with MAF values of 0.24 (global) and 0.16 (east asia). This indicates that the SNP is relatively uncommon in these populations. Both

DRC7 and

KIF6 stand out as promising candidates for meaningful genetic testing in the context of male infertility.

STPG2 (sperm tail PG-rich repeat containing 2) contains a PG-rich motif characterized by a five-residue pattern: P-G-P-x-Y, and forms a similar structure bound to the outer junction of microtubule [

25]. The expression profile of STPG2 protein suggests that it might be important in both testicular development and spermatogenesis and its deletion could impair spermatogenesis [

26]. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP, rs3809611) in the

STPG2 gene was identified through Illumina TruSeq whole exome sequencing (WES). The frequency of mutations among infertile patients was 87.5% (7/8), while the control group with recent fertility exhibited a mutation frequency of 14.3% (1/7). To validate SNP by Sanger sequencing, the ratio of

STPG2-mutated cases (20/31) to controls (2/8) is approximately only 2.6. Furthermore, it's noteworthy that our random sampling in ordinary men displayed a similar mutation frequency of 40%, which matches with the MAF. Of particular interest, the Azoospermia subgroup showed a mutation rate of 80% (12/15), as did the oligospermia group with 50% mutations (8/16). However, the

STPG2 gene itself presents an almost 40% mutation rate globally, whereas in East Asian populations, this rate drops to 30%. Consequently, when evaluating its potential relevance to male infertility, it's less representative compared to

KIF6 due to its already elevated mutation rate in ordinary men.

NEK2 (NIMA-related kinase 2) NEK2 (NIMA-associated kinase 2) is involved in centrosome duplication, a key process that ensures the correct organization of the microtubule organizing center of the cell [

27]. Accurate cell division is essential for proper sperm development. Any disruption caused by abnormal

NEK2 activity could result in damaged sperm cells. These disturbances may lead to diseases such as male infertility [

28].

NEK2 has a global MAF of 0.16 and an East Asian MAF of 0.22. Its relatively low mutation rate can be used as a strong reference index for male infertility. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP, rs2230489) in the

NEK2 gene was identified by Illumina TruSeq whole-exome sequencing (WES), and the mutation rate of the cases was 75% (6/8), while the mutation rate of the control group was 14.3 %(1/7).

Other genes affect spermatogenesis by variants analysis

SPATA16 (spermatogenesis-related 16, also known as NYD-SP12) is highly expressed in human testis and localized to the Golgi apparatus and pro-acrosomal vesicles [

29], which fuse to form the acrosome during spermatogenesis [

30,

31]. It was identified as the first autosomal gene and demonstrated that a homozygous mutation (c.848G→A) led to globozoospermia, the production of round headed and acrosomeless spermatozoa. In this study, we report that three closely homozygous mutations in

SPATA16 (rs16846616), (rs1515442) and (rs1515441) are not only associated with male infertility, but especially azoospermia in our Taiwan cohort. In particular,

SPATA16 (rs16846616) and (rs1515441) co-occur with a higher frequency (80%) in our azoospermic patients of Taiwan.

CFTR (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator) is one of the most common genetic mutations leading to azoospermia, which can lead to abnormalities in the male reproductive tract and ultimately result in infertility [

32,

33]. In our Sanger sequencing study, you found that 51.6% (16 out of 31) of infertile men had

CFTR mutations. These mutations were absent in ordinary men. Among the infertile men with

CFTR mutations, 67% of those with azoospermia (lack of sperm in semen) and 37.5% of those with oligospermia (low sperm count) had these mutations. Based on our findings, we establish a strong association between mutations in the

CFTR gene, specifically the rs213950 mutation, and the occurrence of oligospermia and azoospermia in this cohort of Taiwanese patients.

CMTM2 (CKLF-Like Marvel Transmembrane Domain Containing 2) plays a critical role in spermiogenesis in mice has been studied extensively34].CMTM2 has been extensively studied and is found to play a crucial role in spermiogenesis in mice. This gene's significance is particularly pronounced during the essential stages of sperm development. CMTM2-/- mice were unable to produce sperm, while CMTM2+/- mice exhibited a significant reduction in sperm count and motility. A single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP, rs2290182) in the CMTM2 gene was identified by Illumina TruSeq whole-exome sequencing (WES), and the mutation rate of the cases was 75% (6/8), while the mutation rate of the control group was 14.3 %(1/7). The Global Minor Allele Frequency (GMAF) and East Asian Minor Allele Frequency (MAF) were determined to be 0.17 and 0.28, respectively, indicating a higher prevalence within the East Asian population.

In this study, Ampiseq targeted NGS panel and Illumina TruSeq WES were both used to pinpoint 6 specific genes (KIF6, DRC7, STPG2, SPATA16, CFTR, CMTM2) that play a role in microtubule association and spermiogenesis, which are crucial factors in understanding the causes of male infertility.

Conclusions

Male infertility-associated genes can be roughly divided into three affected clusters: tubulin-associated genes (dynein and kinesin), outer junction proteins- associated genes, and spermatogenesis-associated genes. In our experimental results provide pinpointing evidence for a potential link between genetic variations in the

KIF6, DRC7, and

STPG2 genes and male infertility (

Figure 4). The fact that the prevalence of these SNPs was found to be significantly higher in infertile men compared to fertile men suggests that these genetic variations could indeed be associated with the development of male infertility. The alignment of our findings with the significance of microtubule-related genes, particularly in the context of sperm cell structure and function, adds an additional layer of biological plausibility to the observed associations. Microtubule is indeed essential components of the cytoskeleton and play crucial roles in cellular processes, including the formation of sperm heads and tails. The potential for genetic diagnosis based on these findings is promising, as it suggests that certain genetic variations could serve as markers for identifying individuals at a higher risk of male infertility. Our further approach also includes CRISPR gene knockout experiments to gain deeper insights into the precise roles of these candidates and their potential associations with male infertility. By involving larger azoospermic and oligozoospermic cohorts, we anticipate accelerating the identification of novel genes contributing to these phenotypes, ultimately contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of male infertility.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Tri-Service General Hospital (TSGH-A-111012), Taipei City Hospital (TPCH-108-45) and Ministry National Defense Medical Affairs Bureau (MAB-109-032).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the National Defense Medical Center Instrument Center for their technical services. We appreciate the technical supports provided by Genomics Center for Clinical and Biotechnological Applications of Cancer Progression Research Center, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, is supported by National Core Facility for Biopharmaceuticals (NCFB), Ministry of Science and Technology. We also thank the National Center for High-performance Computing (NCHC) of National Applied Research Laboratories (NARLabs) in Taiwan for providing computational and storage resources.

Disclosures

THY, HCT, PKH, JLC, BM&YCH performed the research; CCC, HCT, PKH, GJW&YCH analyzed the data and wrote the paper; THY, CCC&GJW executed the IRB for the study and YCH, BM, CCC&GJW designed the research study and wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Abbreviations

azoospermia (Azoo); oligozoospermia (Oligo); Y chromosome microdeletion (YCMD); targeted next-generation sequencing (targeted NGS); Illumnia Truseq DNA whole-exome sequencing (WES); minor allele frequency (MAF); CLC Genome Workbench 23.0.4 (CLC) spermatogenesis-related 16 (SPATA16); cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR); kinesin family member 6 (KIF6) ; sperm tail PG-rich repeat containing 2 (STPG2); dynein regulatory complex subunit 7 (DRC7); NIMA-related kinase 2 (NEK2); CKLF-Like Marvel Transmembrane Domain Containing 2 (CMTM2); intra-flagellar transport (IFT)

References

- Smits, R.M.; van de Ven, P.M.; et al. Defining infertility - a systematic review of prevalence studies. Hum Reprod Update. 2019, 25, 209–223. [Google Scholar]

- Tahmasbpour, E.; Balayla, J. Natural Conception Rates in Subfertile Couples Following Ovulation Induction and Intrauterine Insemination. J Reprod Infertil. 2014, 15, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Gunes, S.; Seli, E. Inhibition of microtubules and dynein rescues human sperm function. Fertil Steril. 2020, 113, 338–345. [Google Scholar]

- Vale, R.D.; Reese, T.S.; et al. The mechanism of dynein motility: insight from crystal structures of the motor domain. BioEssays. 2003, 25, 961–968. [Google Scholar]

- Lehti, M.S.; Sironen, A. Formation and function of the manchette and flagellum during spermatogenesis. Reproduction. 2016, 151, R43–R54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmke, K.J.; Heald, R.; et al. A novel RII-binding protein (RACK1) that interacts with the protein kinase CβII subfamily. J Biol Chem. 2013, 278, 5143–5153. [Google Scholar]

- Kierszenbaum, A.L.; Rivkin, E.; et al. TNP1 haploinsufficiency in humans leads to a diminished sperm phenotype. Biol Reprod. 2011, 85, 121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Mohri, H.; Ohtake, H.; et al. Submicromolar concentration of ATP as an energy source for mammalian sperm motility. J Biol Chem. 2012, 287, 7456–7467. [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell, L.; Stanton, P.G.; et al. Identification of atypical aspermatogenesis in testis biopsies from infertile men. Hum Reprod. 2012, 27, 3331–3337. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, F.; Liu, C.; et al. Mutations in PMFBP1 cause acephalic spermatozoa syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. 2016, 99, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liska, F.; Gosele, C.; et al. Disruption of axonemal microtubule organization causes sperm tail defects in an infertile ccdc39 mouse model. J Cell Sci. 2009, 122, 3316–3324. [Google Scholar]

- Pleuger, C.; Fietz, D.; et al. The role of fibrous sheath interacting protein 1 in spermiogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 2016, 366, 135–146. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, R.; Zaman, Q.; Chen, J.; et al. Novel Loss-of-Function Mutations in DNAH1 Displayed Different Phenotypic Spectrum in Humans and Mice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021, 12, 765639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Donnell, L.; O'Bryan, M.K. Microtubules and spermatogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2014, 30, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunleavy, J.E.M.; O'Bryan, M.K.; et al. Regulation of microtubules in the seminiferous epithelium. Microtubule Dynamics: Methods and Protocols. 2019, 1926, 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Kato, T.; Kuramochi-Miyagawa, S.; et al. Gene knockout of Tptr2, encoding a testosterone-responsive protein, results in impaired sperm differentiation and male fertility in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018, 115, 11775–11780. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney, H.L.; Holzbaur, E.L.F. Motor proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018, 10, a021931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miki, H.; Okada, Y.; et al. Mu2-adaptin dissociation from non-clathrin-coated vesicles is regulated by large Arf1 GTPase-activating proteins. J Cell Biol. 2001, 155, 305–318. [Google Scholar]

- Marx, A.; Nugoor, C.; et al. Structure of the actin-depolymerizing factor homology domain in complex with actin. J Cell Biol. 2009, 186, 333–340. [Google Scholar]

- Hirokawa, N.; Tanaka, Y. Kinesin superfamily proteins (KIFs): Various functions and their relevance for important phenomena in life and diseases. Exp Cell Res. 2015, 334, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirokawa, N.; Noda, Y.; et al. KIF1 motor proteins in axonal transport of synaptic vesicles. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020, 77, 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, E.F.; Lefebvre, P.A. The role of central apparatus components in flagellar motility and microtubule assembly. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2020, 77, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morohoshi, A.; Aiso, S.; et al. Mechanism of spermatogenesis and fertility in Drc7, a gene responsible for immotile cilia syndrome. Mol Biol Cell. 2020, 31, 2111–2122. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.; van Blerkom, J.; et al. The dynein regulatory complex is required for ciliary motility and otolith biogenesis in the inner ear. Nature. 2018, 553, 354–357. [Google Scholar]

- Kubo, N.; Imai, F.; et al. Mechanism of STPG2-mediated microtubule stabilization in cilia. Nat Commun. 2023, 14, 343. [Google Scholar]

- Yakut, T.; Over, V.; et al. A novel locus on the X chromosome is linked to dizygotic male infertility. J Med Genet. 2013, 50, 345–353. [Google Scholar]

- Singharajkomron, N.; Yodsurang, V.; Seephan, S.; et al. Evaluating the Expression and Prognostic Value of Genes Encoding Microtubule-Associated Proteins in Lung Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 14724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.J.; Liang, Q.X.; et al. Association study between polymorphisms in NEK2 gene and male infertility. Gene. 2020, 731, 144347. [Google Scholar]

- Ghédir, H.; Ibala-Romdhane, S.; et al. Homozygous mutation of SPATA16 is associated with male infertility in human globozoospermia. Am J Hum Genet. 2019, 105, 413–420. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Zeng, X.; et al. Testis-specific expression of the mouse gene for the axonemal protein sperm-associated antigen 6 (Spag6). Gene Expr Patterns. 2003, 3, 231–236. [Google Scholar]

- ElInati, E.; Lefièvre, L.; et al. Globozoospermia is mainly due to DPY19L2 deletion via non-allelic homologous recombination involving two recombination hotspots. Hum Mol Genet. 2012, 21, 3695–3702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Fuscoe, J.C.; et al. A rat gene catalog based on microarray data. Physiol Genomics. 2004, 16, 249–260. [Google Scholar]

- Bieniek, J.M.; Drabovich, A.P.; et al. Seminal plasma proteins as potential markers of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) function. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2021, 20, 100107. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Li, Y.; et al. CKLF-like MARVEL transmembrane domain-containing member 2 deficiency impairs spermatogenesis and male fertility in mice†. Biology of Reproduction. 2016, 94, 123. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).