Submitted:

04 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Institutional Drivers of National Growth

2.2. Theoretical Characterizations of Inclusive and Extractive Instituions

"Inclusive economic institutions, are those that allow and encourage participation bythe great mass of people in economic activities that make best use of their talents and skills and that enable individuals to make the choices they wish. To be inclusive, economic institutions must feature secure private property, an unbiased system of law, and a provision of public services that provides a level playing field in which people can exchange and contract; it also must permit the entry of new businesses and allow people to choose their careers." [1]

Extractive political institutions concentrate power in the hands of a narrow elite and place few constraints on the exercise of this power. Economic institutions are then often structured by this elite to extract resources from the rest of the society. Extractive economic institutions thus naturally accompany extractive political institutions. In fact, they must inherently depend on extractive political institutions for their survival [1].

2.3. Research Objective

3. Hypotheses

- H1: In the resolute progression of institutional development, nations characterized by a higher degree of inclusiveness manifested in the amplification of voice and accountability, the establishment of effective governance, the adherence to the rule of law, and an augmented commitment to research and development shall inevitably achieve greater sustainability. Inclusive institutions by cultivating an environment where resources are equitably distributed, and innovation is not only encouraged but institutionalized, create the necessary conditions for sustainable practices. These institutions through their large participation, go beyond the limitations of narrow, self-serving interests, and establish congruity between economic growth and sustainability. Good governance and sustainability are inseparable aspects of the modern institution, as effective governance structures inherently facilitate the advancement of sustainability objectives. The integration of sustainability into the core operations of an institution is increasingly recognized as essential [13,14].

- H2: In contrast, nations that exhibit higher scores of extractiveness as evident in the prevalence of corruption, political instability, and low regulatory quality, will manifest diminished sustainability outcomes. These institutions, grounded in the concentration of power and wealth in the hands of a few, thwart the potential for sustainable development. By fostering a system wherein resources are misallocated and inequalities entrenched, such institutions obstruct the very conditions required for long-term prosperity and environmental equilibrium. Ineffective governance, as a limiting factor, can obstruct the advancement of environmental innovation. When governance structures are deficient, institutions are less likely to generate green innovations, particularly in circumstances where institutional ownership is minimal and financial constraints are prevalent. In this context, the lack of robust governance mechanisms acts as a barrier to the development of sustainable solutions, thus hindering the realization of the potential for environmental progress within the institution. The absence of such structures diminishes the capacity for innovation and reinforces the interdependence between governance quality and the pursuit of ecological sustainability [15].

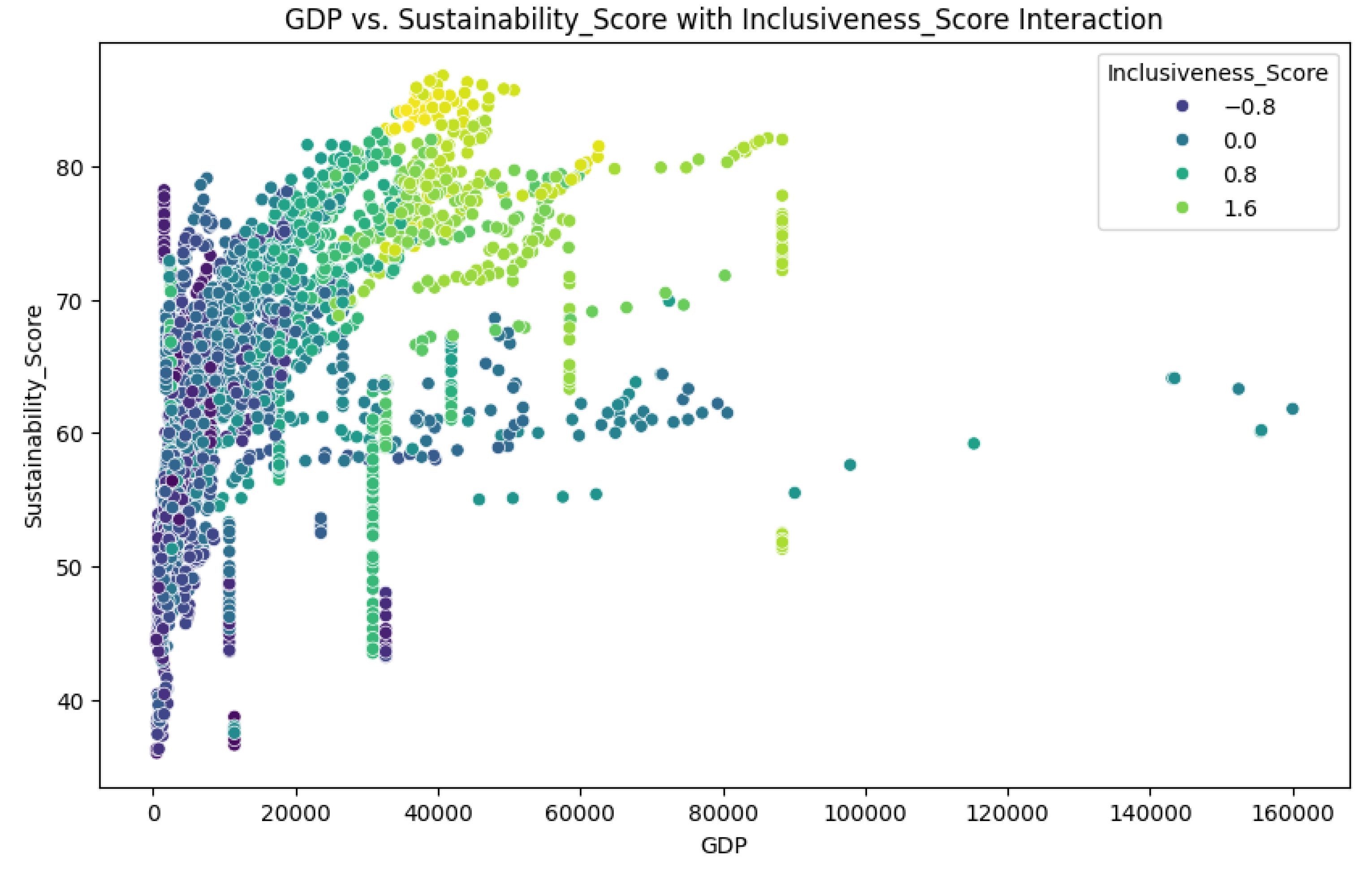

- H3: We hypothesize that the relationship between inclusiveness and sustainability is mediated by the realization of economic growth, which is quantifiable by GDP. The economic growth that emerges from inclusive institutions provides the material foundation necessary for investments in sustainable infrastructures. Through the generation of capital, inclusive growth enables advancements in technology and the development of social programs, positioning economic growth as the essential conduit through which the aspirations of sustainability are actualized. Thus, GDP, as a manifestation of economic prosperity, reflects the material conditions that render sustainable progress achievable.

- H4: We suggest that a higher proportion of R&D expenditure relative to GDP amplifies the positive relationship between inclusiveness and sustainability. The rationale for this lies in the fact that economies driven by innovation, through the allocation of resources towards research and development, are better positioned to cultivate sustainable technologies and practices. In this hypothesis, R&D investment acts as a catalyst, by enhancing the capacity of inclusive institutions to achieve sustainable progress. Through innovation driven by R&D, economies achieve more efficient energy markets and achieve sustainable economic development. In the European Union and the United States, a clear connection emerges, wherein increased R&D spending is correlated with lower CO2 emissions, although the effect manifests more strongly within the European context (regarded as inclusive). However, in China (regarded as less inclusive), the relationship between R&D expenditure and CO2 emissions does not follow the same clear trajectory, as the economic and environmental contexts diverge [16].

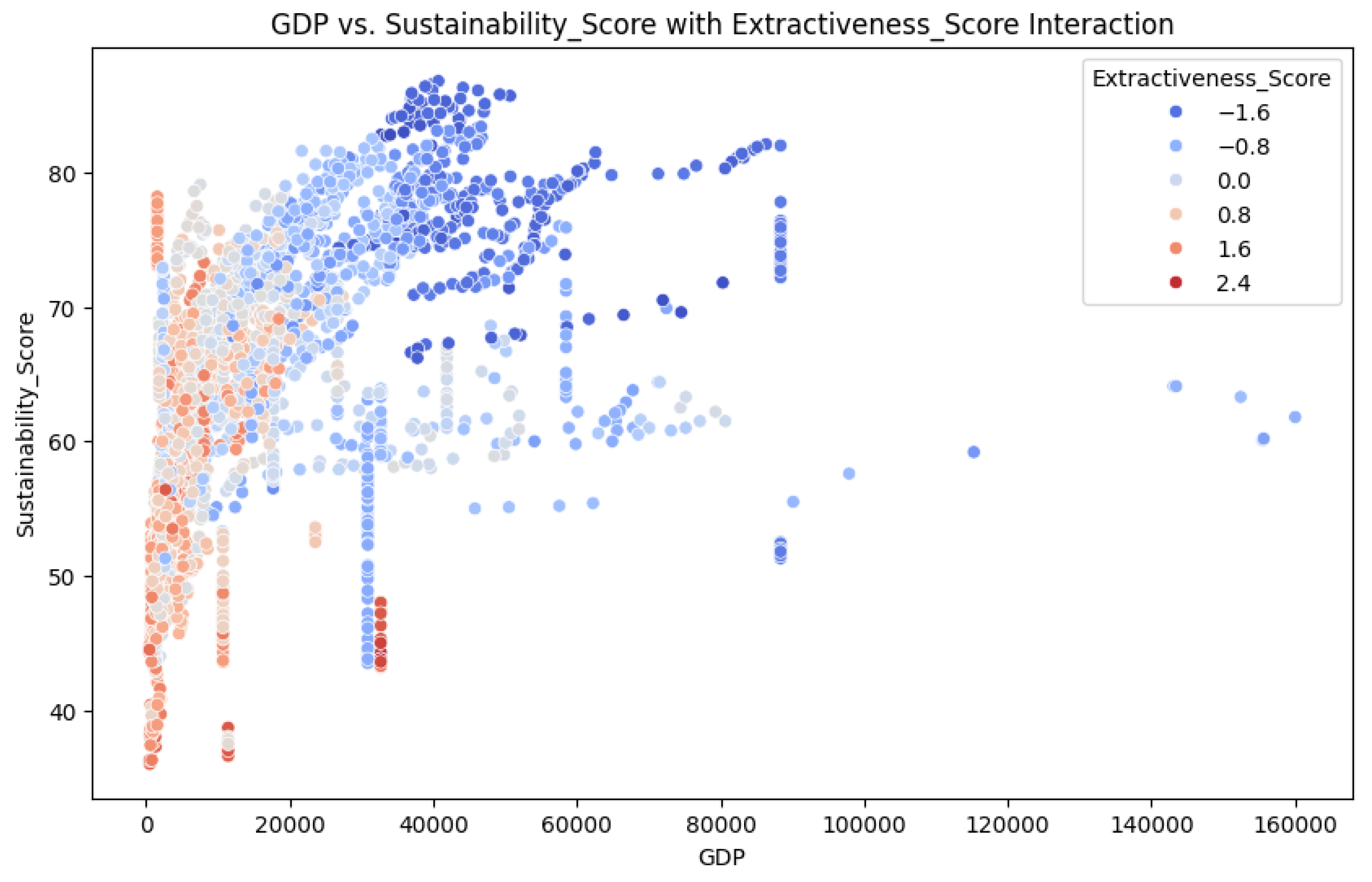

- H5: The interaction between inclusiveness and GDP generates a significant positive effect on sustainability, as inclusive institutions channel economic resources toward sustainable outcomes. Inclusiveness amplifies the benefits of economic growth by engaging in equitable distribution of resources, thereby facilitating the pursuit of long-term sustainability. Conversely, the interaction between extractiveness and GDP exerts a negative influence on sustainability. In extractive systems, economic resources are disproportionately directed toward elite interests, which restricts the potential for widespread development and stalls sustainable progress. Thus, the concentration of power and wealth in such systems hinders the realization of sustainable objectives and creates a cycle that undermines sustainability.

- H6: We hypothesize that the relationship between GDP and sustainability is nonlinear, but follows a quadratic pattern, where the initial stages of economic growth promotes sustainability, yet beyond a certain point, the benefits of growth may plateau or even worsen. This occurs as overconsumption and environmental degradation begin to counterbalance the positive effects of economic development. We posit that the interaction between inclusiveness, extractiveness, and sustainability is not universal, but varies significantly across regions. Local factors and regional contexts, such as specific governance systems and the availability of resources, shape how these institutional frameworks influence sustainability.

4. Data

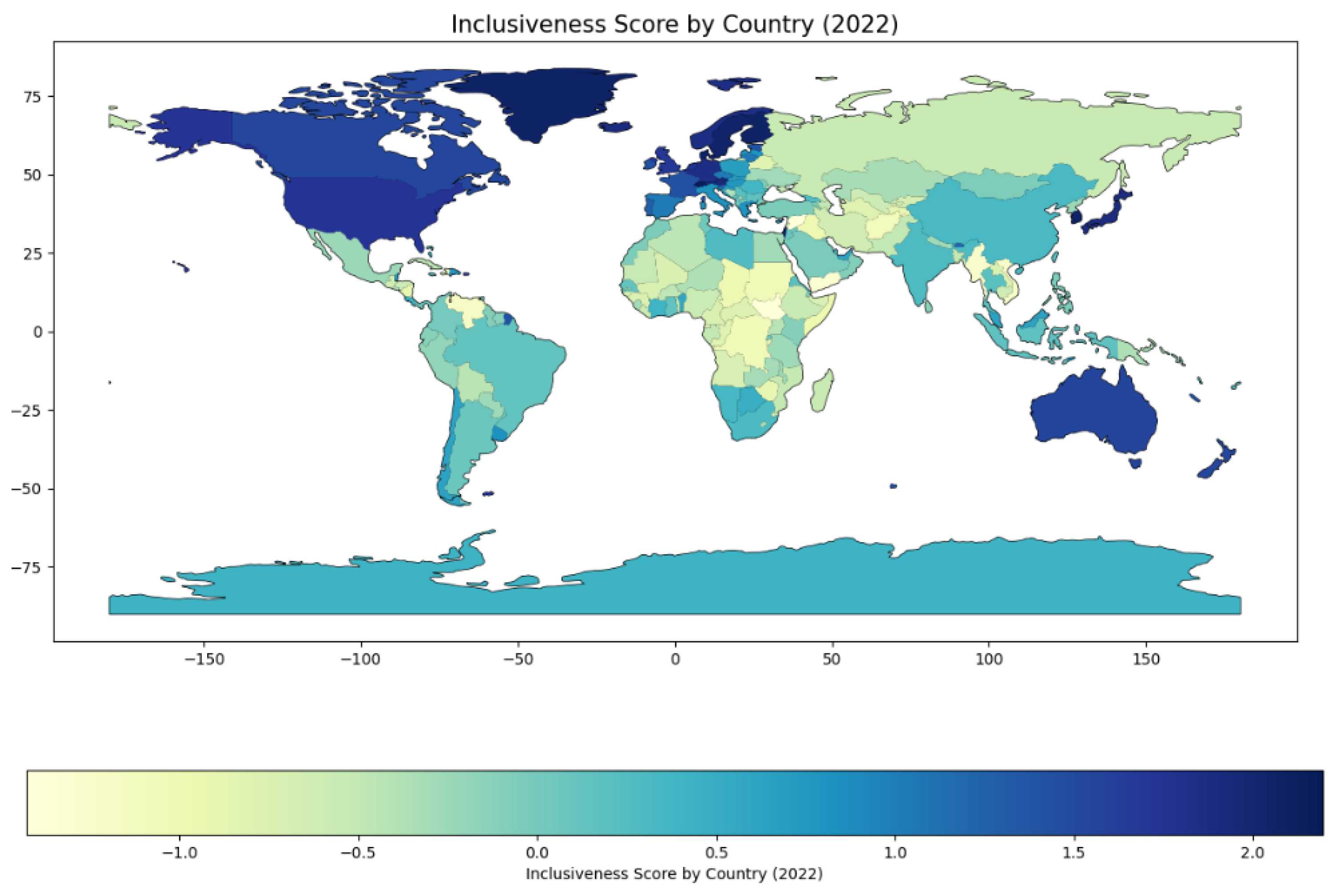

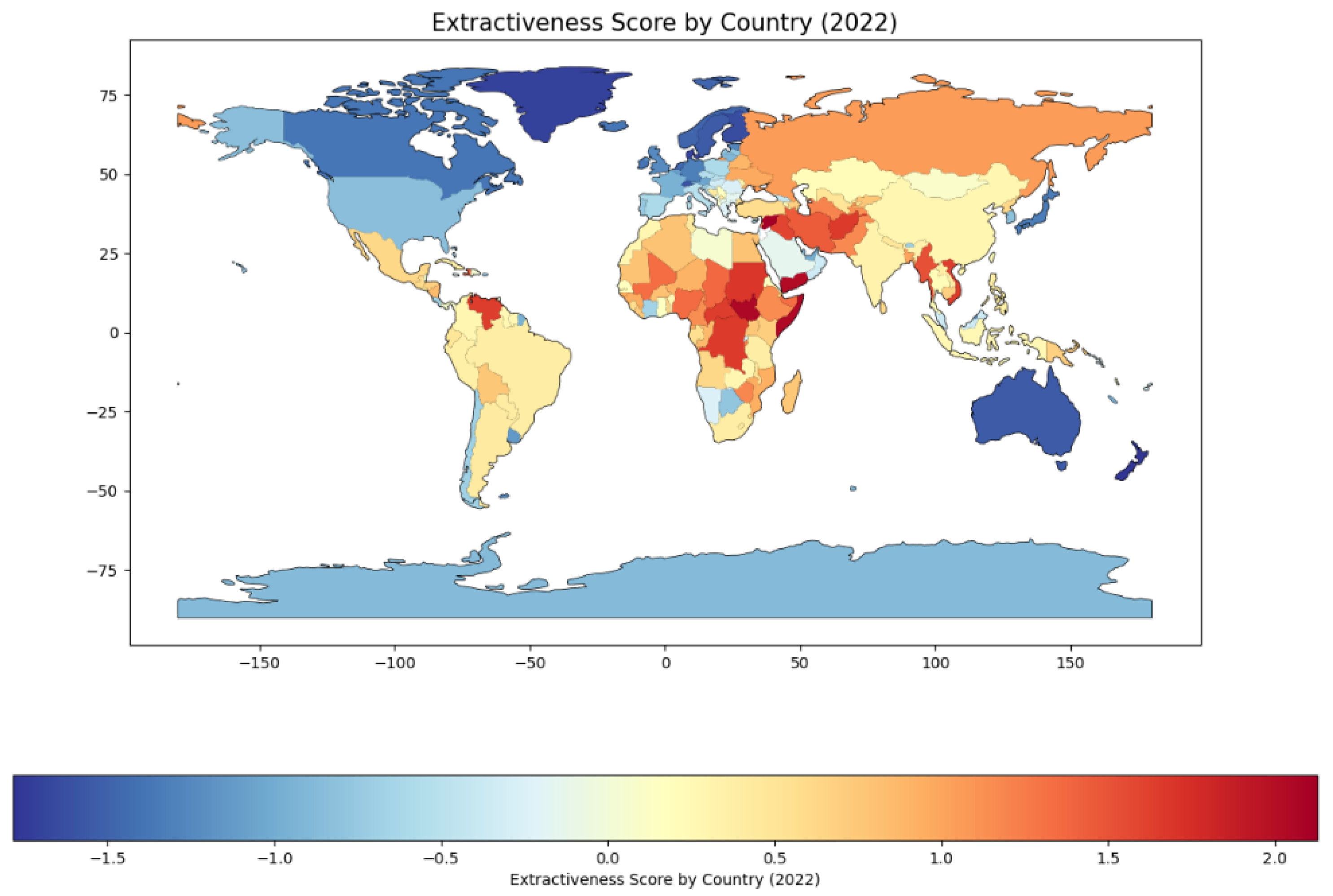

4.1. Governance Indicators

-

Mechanisms of Political Selection and Stability:

- -

- Voice and Accountability (VA) : measures the extent to which citizens can participate in governance through free expression, association, and media.

- -

- Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism (PV): assesses the likelihood of governmental stability and the absence of politically motivated unrest or terrorism.

-

Governmental Capacity for Policy Implementation:

- -

- Government Effectiveness (GE): measures the quality of public service delivery, civil service independence, and the credibility of policy commitments.

- -

- Regulatory Quality (RQ) : evaluates the ability to design and enforce regulations conducive to private sector development.

-

Institutional Respect and Legal Integrity:

- -

- Rule of Law (RL): examines confidence in societal rules, contract enforcement, property rights, and protection from crime and violence.

- -

- Control of Corruption (CC): assesses the extent of misuse of public power for private gain, encompassing both systemic and opportunistic corruption.

4.2. Economic Indicators

4.3. Innovation Indicators

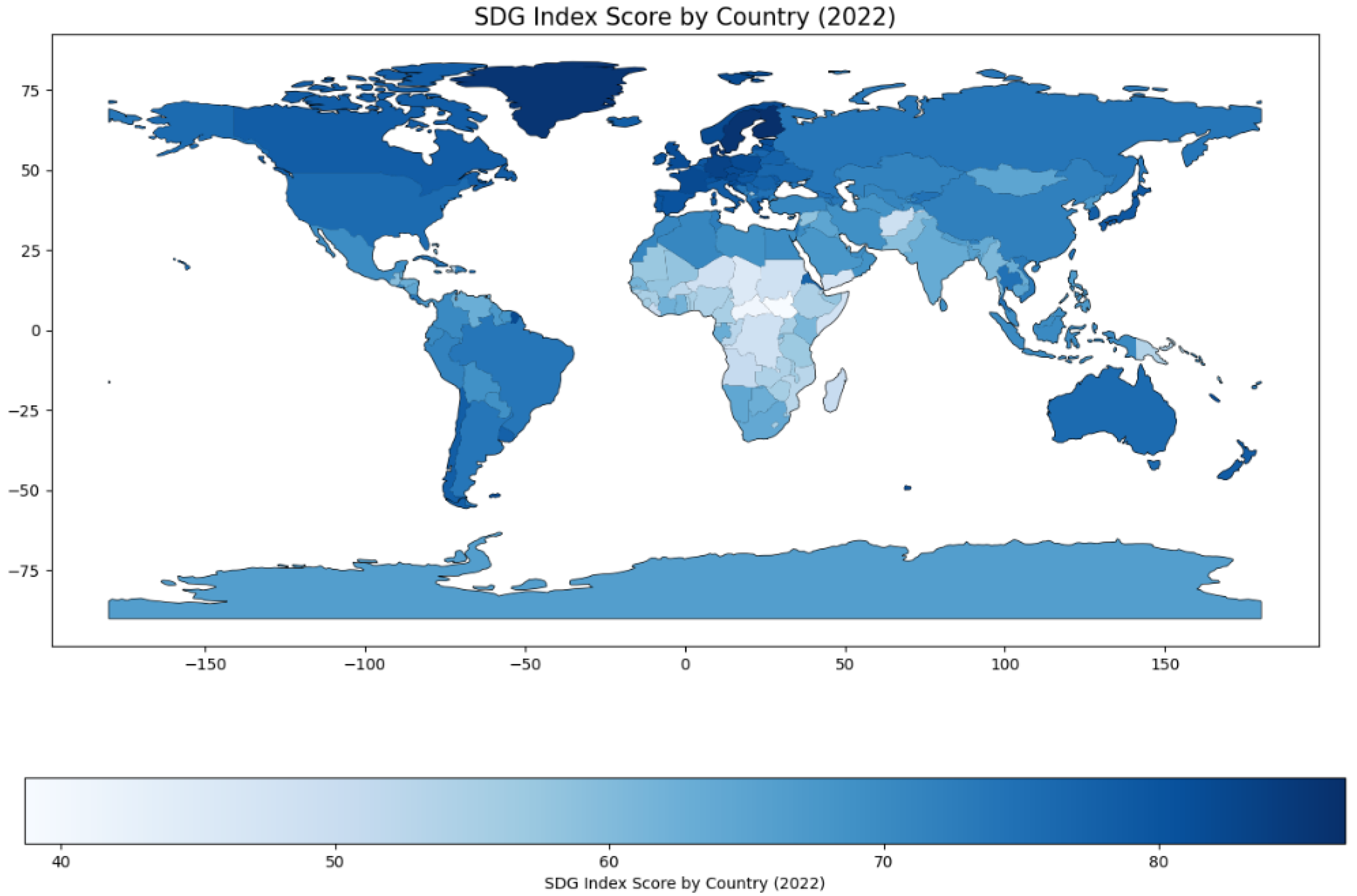

4.4. Sustainibility Indicators

5. Institutions and Sustainability: Methodological Analysis

5.1. OLS Estimates

5.2. Machine Learning Estimates

-

Random Forest is an ensemble learning method that builds multiple decision trees and aggregates their outputs. For regression tasks, the final prediction is computed as the average of predictions from n trees:where is the prediction of the i-th tree for input X. Random sampling of both the data and features ensures model diversity, reducing overfitting and variance.We evaluate the importance of each feature by the total reduction in impurity it provides across all trees. The impurity decrease can be computed using metrics such as the Gini Index or Mean Squared Error:where is the reduction in impurity for feature j in tree t.

-

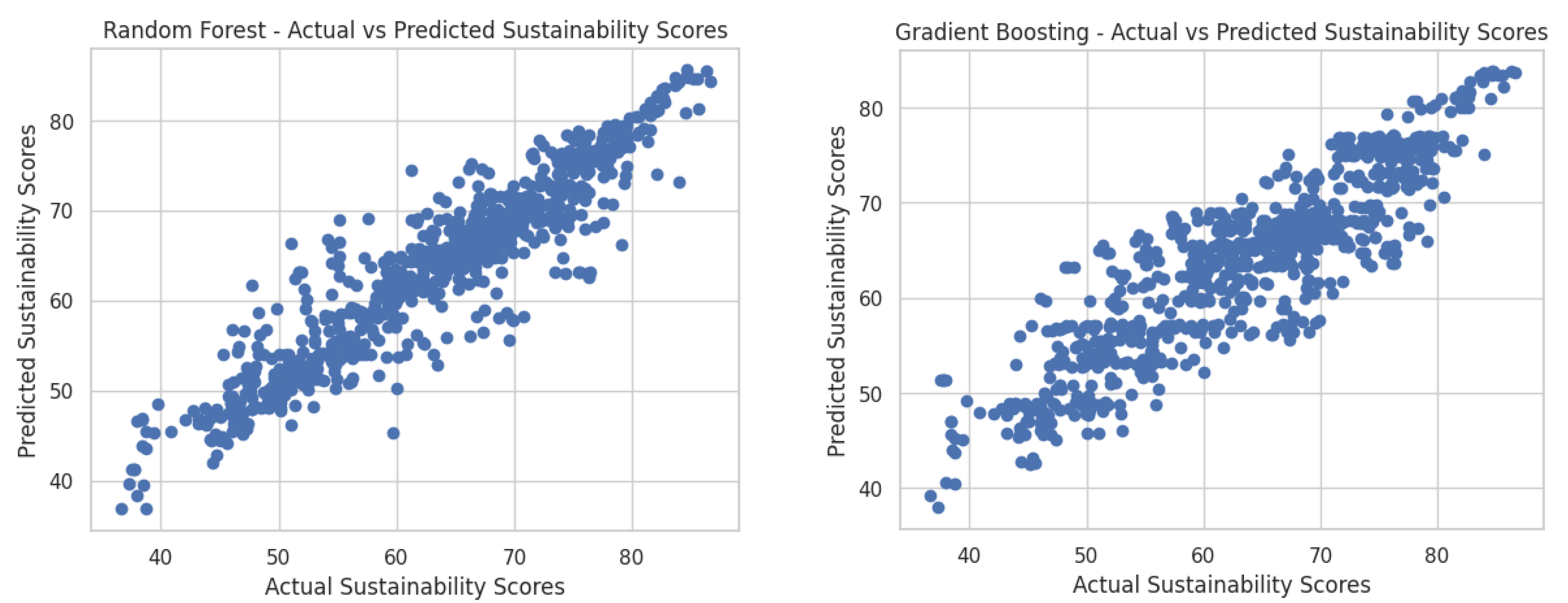

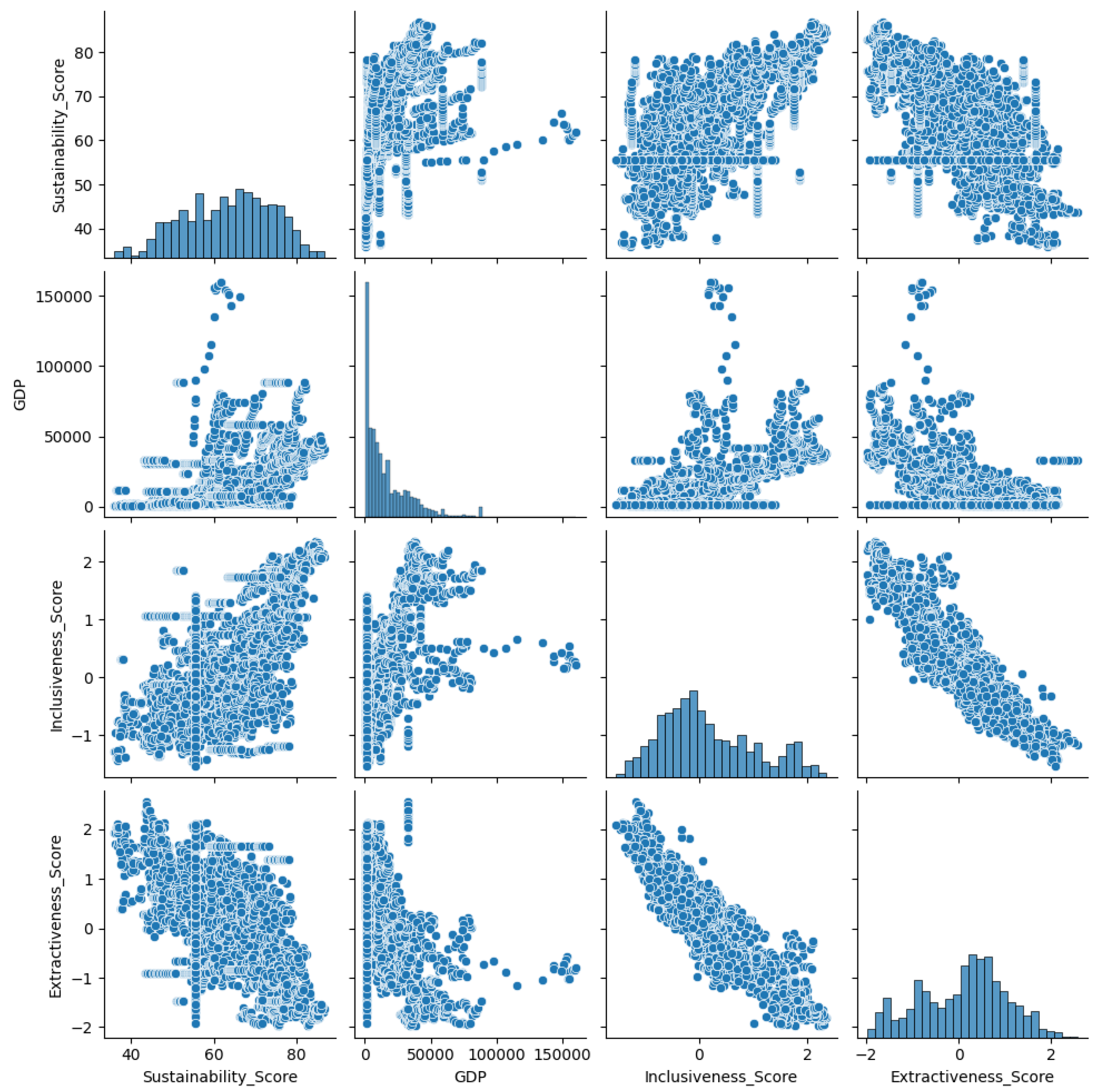

Gradient Boosting sequentially builds decision trees to minimize a specified loss function . For regression tasks, this is commonly the Mean Squared Error:At each iteration, the algorithm fits a new tree to the negative gradient of the loss function (also the residuals):The model updates predictions as:where is the prediction of the k-th tree, and is the learning rate.The scatter plots for both models (See Figure 3 and Figure 4:) Random Forest and Gradient Boosting Regressors show a strong correlation between actual and predicted sustainability scores. This alignment confirms the models capability to observe patterns in the data effectively. The clustering of points near the diagonal line in both scatter plots confirm that the predictions closely follow the true values which leads us to conclude a minimal bias and a good fit.The feature importance analysis further helps us to find the significance of the predictors (Inclusiveness Score, Extractiveness Score, and GDP) in driving the models predictions. In the Random Forest model, feature importance is derived from the reduction in loss across the ensemble of decision trees. The results show that all three predictors contribute meaningfully to the sustainability score predictions, with the relative contributions that ensure their influence on the target variable.The Random Forest model builds on the diversity of decision trees by using bootstrap aggregation (bagging), which reduces variance and guards against overfitting. By averaging predictions across multiple trees, the model achieves robust performance, even when the data includes noise or complex interactions between variables.In contrast, the Gradient Boosting model follows a sequential shape, where each new tree corrects the residual errors of the previous ones. It’s an iterative learning mechanism that helps Gradient Boosting to focus on areas where the model struggles and leads to reduced bias and improved accuracy. The learning rate () in the Gradient Boosting controls the step size of corrections and balances the trade-off between training time and model precision.

5.3. Granger Causality Test: Research and Development as Driver for Sustainability

| Statistic | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| R&D Expenditure ADF Test p-value | 0.0 | Stationary time series |

| SDG Index Score ADF Test p-value | 1.5818561954387344e-13 | Stationary time series |

| Lag | F-Test Value | p-value |

| Lag 1 F-Test | 5.8948 | 0.0152 |

| Lag 1 Chi-Square Test | 5.8991 | 0.0151 |

| Lag 1 Likelihood Ratio Test | 5.8949 | 0.0152 |

| Lag 1 Parameter F-Test | 5.8948 | 0.0152 |

| Lag 2 F-Test | 3.4995 | 0.0303 |

| Lag 2 Chi-Square Test | 7.0074 | 0.0301 |

| Lag 2 Likelihood Ratio Test | 7.0015 | 0.0302 |

| Lag 2 Parameter F-Test | 3.4995 | 0.0303 |

| Lag 3 F-Test | 2.3078 | 0.0745 |

| Lag 3 Chi-Square Test | 6.9350 | 0.0740 |

| Lag 3 Likelihood Ratio Test | 6.9292 | 0.0742 |

| Lag 3 Parameter F-Test | 2.3078 | 0.0745 |

| Lag 4 F-Test | 1.7889 | 0.1281 |

| Lag 4 Chi-Square Test | 7.1712 | 0.1271 |

| Lag 4 Likelihood Ratio Test | 7.1650 | 0.1274 |

| Lag 4 Parameter F-Test | 1.7889 | 0.1281 |

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

References

- Robinson, J.A.; Acemoglu, D. Why nations fail: The origins of power, prosperity and poverty; Profile London, 2012.

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J.A. Rents and economic development: the perspective of Why Nations Fail. Public Choice 2019, 181, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radionova, I.O. INCLUSIVE SOCIETY: FROM THEORY TO REALITIES 2019. 2, 195–207. [CrossRef]

- Natkhov, T.; Polishchuk, L. Political Economy of Institutions and Development: The Importance of Being Inclusive. Reflection on "Why Nations Fail" by D. Acemoglu and J. Robinson. Part II. Institutional Change and Implications for Russia. Journal of the New Economic Association 2017, 35, 12–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, J. Why Nations Fail. The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty. International Journal of Social Economics 2014, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. Institutions as the Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth. CEPR Discussion Paper Series 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. Chapter 6 Institutions as a Fundamental Cause of Long-Run Growth 2005. 1, 385–472. [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S. Unbundling Institutions. Journal of Political Economy 2003, 113, 949–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, C.R. Informal institutions rule: institutional arrangements and economic performance. Public Choice 2009, 139, 371–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przeworski, A. Institutions Matter? 1. Government and Opposition 2004, 39, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devos, T.; Spini, D.; Schwartz, S. Conflicts among human values and trust in institutions. The British journal of social psychology 2002, 41 Pt 4, 481–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capoccia, G. 89Critical Junctures. In The Oxford Handbook of Historical Institutionalism; Oxford University Press, 2016; [https://academic.oup.com/book/0/chapter/212252849/chapter-ag-pdf/44594567/book_28116_section_212252849.ag.pdf]. [CrossRef]

- Aras, G.; Crowther, D. Governance and sustainability: an investigation into the relationship between corporate governance and corporate sustainability. Management Decision 2008, 46, 433–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klettner, A.; Clarke, T.; Boersma, M. The Governance of Corporate Sustainability: Empirical Insights into the Development, Leadership and Implementation of Responsible Business Strategy. Journal of Business Ethics 2014, 122, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amore, M.; Bennedsen, M. Corporate Governance and Green Innovation. S&P Global Market Intelligence Research Paper Series 2015. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, Y.; López, M.A.F.; Blanco, B.O. Innovation for sustainability: The impact of R&D spending on CO2 emissions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 172, 3459–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Worldwide Governance Indicators, 2024. Accessed: 2024-12-25.

- Kaufmann, D.; Kraay, A.C. The Worldwide Governance Indicators : Methodology and 2024 update. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099005210162424110/IDU17c6f0b9e1f0c214b1d1b30d176c4644af69e. Accessed: 2024-12-25.

- Roser, M.; Arriagada, P.; Hasell, J.; Ritchie, H.; Ortiz-Ospina, E. Data Page: GDP per capita. Online resource, 2023. Part of the publication: Economic Growth. Data adapted from Bolt and van Zanden.

- Sachs, J.D.; Lafortune, G.; Fuller, G.; Drumm, E. Implementing the SDG Stimulus. Sustainable Development Report 2023; Dublin University Press: Dublin, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, C.; Metternicht, G.; Wiedmann, T. Initial progress in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): a review of evidence from countries. Sustainability Science 2018, 13, 1453–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. The Age of Sustainable Development 2015. [CrossRef]

- del Río Castro, G.; Fernández, M.C.G.; Ángel Uruburu Colsa. Unleashing the convergence amid digitalization and sustainability towards pursuing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): A holistic review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021. [CrossRef]

- Troster, V. Testing for Granger-causality in quantiles. Econometric Reviews 2018, 37, 850–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, K.; Härdle, W. A CONSISTENT NONPARAMETRIC TEST FOR CAUSALITY IN QUANTILE. Econometric Theory 2007, 28, 861–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S. Granger Causality in Risk and Detection of Extreme Risk Spillover Between Financial Markets. Journal of Econometrics 2009, 150, 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistic | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Sustainability_Score | |

| R-squared | 0.367 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.366 | |

| F-statistic | 830.8 | 1 |

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.00 | Significant at the 0.01 level |

| Log-Likelihood | -15324 | |

| No. Observations | 4306 | |

| AIC | 30660 | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | 30680 | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| Covariance Type | Nonrobust | |

| Variable | Coefficient | Confidence Interval (95%) |

| const | 63.3737 | [63.120, 63.628] |

| x1 | 2.9577 | [2.267, 3.649] |

| x2 | -2.8416 | [-3.516, -2.167] |

| x3 | 1.0927 | [0.752, 1.433] |

| Statistic | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Sustainability_Score | |

| R-squared | 0.367 | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.366 | |

| F-statistic | 830.8 | 1 |

| Prob (F-statistic) | 0.00 | Significant at the 0.01 level |

| Log-Likelihood | -15324 | |

| No. Observations | 4306 | |

| AIC | 30660 | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | 30680 | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| Covariance Type | Nonrobust | |

| Variable | Coefficient | Confidence Interval (95%) |

| const | 63.3737 | [63.120, 63.628] |

| x1 | 2.9577 | [2.267, 3.649] |

| x2 | -2.8416 | [-3.516, -2.167] |

| x3 | 1.0927 | [0.752, 1.433] |

| Statistic | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | log_Sustainability_Score | |

| Model | RLM | Robust Linear Model |

| Method | IRLS | Iteratively Reweighted Least Squares |

| Norm | HuberT | |

| Scale Estimation | MAD | Median Absolute Deviation |

| Covariance Type | H1 | |

| No. Observations | 4306 | |

| Df Residuals | 4302 | |

| Df Model | 3 | |

| Date | Fri, 20 Dec 2024 | |

| Time | 11:59:20 | |

| No. Iterations | 21 | |

| Variable | Coefficient | Confidence Interval (95%) |

| const | 4.1567 | [4.153, 4.161] |

| x1 | 0.0461 | [0.035, 0.057] |

| x2 | -0.0448 | [-0.056, -0.034] |

| x3 | 0.0205 | [0.015, 0.026] |

| Statistic | Value | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Sustainability_Score | |

| Model | OLS | Ordinary Least Squares |

| Method | Least Squares | |

| Covariance Type | Nonrobust | |

| No. Observations | 4306 | |

| Df Residuals | 4300 | |

| Df Model | 5 | |

| Date | Fri, 20 Dec 2024 | |

| Time | 12:00:02 | |

| Variable | Coefficient | Confidence Interval (95%) |

| const | 63.3737 | [63.133, 63.614] |

| Inclusiveness_Score | 1.4549 | [0.640, 2.270] |

| GDP | -3.0980 | [-3.753, -2.443] |

| Extractiveness_Score | 8.2382 | [7.532, 8.945] |

| Extractiveness_GDP_Interaction | -1.2000 | [-1.725, -0.675] |

| Inclusiveness_GDP_Interaction | -6.1485 | [-6.721, -5.576] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).