1. Introduction

Microsoft Windows dominates the global operating system (OS) market, with over 75% of desktop users worldwide relying on it for both personal and professional purposes [

1]. This widespread adoption, however, makes Windows a prime target for malicious actors seeking to exploit vulnerabilities for data theft, system disruption, and other nefarious activities [

2]. The Windows Registry (WR) serves as a living repository of configuration settings, user activities, and system events, providing a foundation for reconstructing digital event sequences, detecting malicious behaviour, and delivering crucial evidence in investigations [

10]. The response to cyber incidents involves both live monitoring and post-incident forensic analysis. Live monitoring tracks and records system data in real time, while post-incident analysis investigates events after they occur. Both methods are used to map Registry paths containing Universal Serial Bus (USB) identifiers, such as make, model, and global unique identifiers (GUIDs), which distinguish individual USB devices. These identifiers are often located in both allocated and unallocated Registry spaces [

8].

However, the sheer volume of data within the Registry and the sophistication of modern cyberattacks pose significant challenges for the digital forensics and incident response (DFIR) community [

7]. The introduction of Windows 10 and 11, designed for seamless operation across computers, smartphones, tablets, and embedded systems, has further expanded their adaptability and reach, complicating forensic efforts [

6].

Current Registry forensic analysis faces several challenges. The volume of data is immense, while the lack of automation in traditional tools forces time-consuming manual work. Its dynamic nature and frequent changes complicate tracking, and limited contextual information often demands expert interpretation. Moreover, data fragmentation across hives and keys, the evolution of Windows versions, and limited advanced analysis features further hinder effective forensic investigation. Addressing these challenges requires advanced tools, investigative techniques, and artificial intelligence (AI) integration to enhance the efficiency and accuracy of Registry analysis.

This research seeks to improve the efficiency of forensic investigations involving the WR by introducing a framework that integrates Reinforcement Learning (RL) with a Rule-Based AI (RB-AI) system. The framework employs a Markov Decision Process (MDP) model to represent the WR and events timeline, enabling state transitions, actions, and rewards to support analysis and event correlation.

The motivation for adopting RL lies in its ability to automate and expand the scope of WR analysis in cyber incident response, given the increasing complexity of modern cyber threats. The registry is vital for tracking system changes and detecting traces of malicious activity, yet its vast data volume creates major challenges, particularly for real-time investigation. Manual analysis is often resource-intensive and time-consuming, limiting the effectiveness of forensic efforts. By combining RL with RB-AI, the proposed framework enhances automation, accuracy, and coverage of WR analysis. Since the registry stores essential data such as system configurations, application records, and operational traces, this integration offers a promising approach to extracting relevant evidence more efficiently and reliably.

1.1. Research Questions

This study aims to contribute to the advancement of cyber incident response in the context of WR analysis and forensics by addressing the following research questions:

RQ1: How can combining RL and RB-AI in WinRegRL enhance effectiveness, accuracy, and scalability of Windows forensic investigations?

RQ2: What performance metrics validate WinRegRL’s effectiveness over traditional forensics, and how does it address modern cybercrime targeting WR artefacts?

RQ3: To what extent does WinRegRL enable consistent, optimised multi-machine analysis, and what are the implications for DFIR applications?

1.2. Novelty and Contribution

This research introduces a novel application of RL to automate Windows cyber incident investigations, addressing gaps and limitations in existing registry analysis methods, tools, and techniques. The main contributions to the body of knowledge and DFIR practice are:

MDP model and WinRegRL: A novel MDP-based framework that provides a structured representation of the Windows environment (Registry, volatile memory, and file system), enabling efficient automation of the investigation process.

Expertise extraction and reply: By capturing and generalising optimal policies, the framework reduces investigation time through direct feeding of these policies into the MDP solver, minimising the time required for the RL agent to discover decisions.

Performance superiority: Empirical results demonstrate that the RL-based approach surpasses existing industry methods in consumed time, relevance, and coverage, for both automated systems and human experts.

For clarity, the following terms are used throughout this paper. The following

Table 1 summarises key abbreviations used in this paper.

1.3. Article Organization

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows:

Section 2 provides an overview of WR and volatile memory forensic analysis, along with the state-of-the-art tools and investigation frameworks.

Section 3 explains the registry structure, its forensic relevance, and introduces RL key elements, approaches, and their use in this research. It also details the architecture and modules of the proposed RL-powered framework, hereafter referred to as WinRegRL.

Section 4 discusses the WinRegRL implementation, testing results, and their interpretation. Finally,

Section 5 presents reflections, conclusions, and future research directions.

2. Literature Review

The WR is a cornerstone of Microsoft Windows OS, serving as a hierarchical database that stores configuration settings, system information, and user preferences. From a forensic perspective, the Registry is a goldmine of information, offering insights into system activities, user actions, and potential security breaches.

Table 2 summarises the high-level architecture and content of different registry hives. These hives store critical data, including user profiles, installed software, and network settings, and are traditionally analysed using tools such as Registry Editor or specialised forensic software like FTK Imager. Key forensic artefacts within the Registry include

UserAssist (recently executed programs),

MRU (most recently used files),

ShellBags (folder navigation), and

External Devices (connected USB drives) [

17]. These artefacts provide valuable information for live security monitoring and post-incident investigations.

Specific work in post-incident malware investigations has incorporated RL to efficiently process memory dumps, network data, and registry hives. By defining registry artefacts as part of the state space in an MDP model, RL-based systems can classify and prioritise malicious registry entries, improving both speed and accuracy. This approach integrates Q-learning algorithms to train agents on actions such as identifying anomalies, collecting forensic data, and correlating registry changes with attack vectors [

10]. The intervention of technology has rapidly improved the quality of forensic science, especially in the field of digital forensics. However, the need for speedy and intelligent investigation still exists to maintain an elevated position on digital crime [

34]. ProDiscover is a digital forensic tool used to generate and analyse data. It can be used to analyse a broad range of data and generate reports autonomously. It can also be used for searching specific data based on the node-enabled.

In [

33], researchers proposed ARXEL, an interacting GUI which is an automated tool for WR analysis that has the capability of extracting data from an E01 image. AXREL uses interacting NTFSDUMP, which then outputs results in a table mode, containing key registry information that can be used for manual investigation with a keyword search that is related to specific events. However, this tool only filters system information, program execution, autoruns, and installed software. ARXEL is time-efficient and productive. However, it must be noted that it does not analyse all necessary data. It also needs to be manually verified for accuracy and relevance reasons.

The multi-agent digital investigation toolkit (MADIK) proposed by [

37] is a tool used to assist cyber incident response in forensic examination. It deploys an intelligent software agent (ISA), a system that uses AI to achieve defined goals in an autonomous manner. The tool performs different analyses related to a given case in a distributed manner [

10]. MADIK contains six intelligent agents, including HashSetAgent, TimelineAgent, FileSignatureAgent, FilePathAgent, KeywordAgent, and WindowsRegistryAgent. The WR Agent examines information related to time zones, installed software, removable media information, and others [

37].

AI-enabled forensic analysis has become outstanding in its contribution to detecting and preventing digital crimes [

10]. In AI, machine learning (ML) has four main categories: supervised learning, semi-supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and RL. Thi latter works by rewarding good behaviours and punishing behaviours that are not good enough. Various ML approaches, including KNN, DT, SVM, PCA, K-Means, SVD, NB, ANN, LR, and RF have been deployed for forensic analysis. The WR is a huge data source for forensic analysis, and advantage must be taken of AI techniques to analyse the WR [

14].

Kroll artefact parser and extractor (KAPE) is a multifunctional digital forensic tool developed for efficient data collection and parsing of forensically relevant artefacts [

46]. It uses a target-based approach to data acquisition. Targets are predefined instructions for KAPE, identified by their

tkape extension, directing it to locate specific files and folders on a computer. Upon the identification of items that align with the predetermined criteria, KAPE methodically duplicates the pertinent files and folders for subsequent analysis. The tool comprises an array of default targets, including the SANS_Triage compound collection, which enhances the efficiency of triage and evidence collection. Furthermore, various programs are run against the files, and the output from the programs is then saved in directories named after a category, such as Evidence_Of_Execution, Browser_History or Account_Usage.

Table 3 summarise the most relevant research works proposing impactful tools or frameworks.

3. Research Methodology

This section provides an outline of the RL choice and research methodology followed in this work. These steps are summarised below in a manner which enables grasping the WR (WinRegRL) Forensics domains and components and understanding the interaction between the different entities and the human expert. The research methodology used in this research has five steps:

Current Methods Review for WR Analysis Automation and study the mechanisms, limitations, and challenges of existing methods in light of the requirements set by WR forensics for efficiency and accuracy.

Investigating Techniques and Approaches used in WR Forensics. we particularly focused on ML approaches and rule-based reasoning systems that can extend or replace human intervention in the sequential decision-making processes involved in WR forensics. Find the best ways through which Rule-Based AI systems can be integrated into the forensics process in order to gain better investigative results.

WinRegRL framework development from the design to the implementation of the different modules, making the WinRegRL framework. We first focus on the WinRegRL-Core, which introduces a new MDP model and Reinforcement Learning to optimise and enhance WR investigations. Also, add a module to capture, process, generalise, and feed human expertise into the RL environment using a Rule-Based AI (RB-AI) via Pyke Python Knowledge Engine.

Testing and Validation of WinRegRL on the latest research and industry standards datasets made to mimic real-world DFIR scenarios and covering different sizes of evidence, especially in large-scale WR forensics. The performance of the framework should be evaluated against traditional methods and human experts in terms of efficiency, accuracy, time reduction, and artefact exploration. Refine the framework iteratively based on feedback testing for robust and adaptive performance in diverse investigative contexts.

Finalisation of the WinRegRL Framework through unifying reinforcement learning and rule-based reasoning to support efficient WR and volatile data investigations. The final testing will demonstrate how it reduces reliance on human expertise while increasing efficiency, accuracy, and repeatability significantly, especially in cases with multiple machines of similar configurations.

3.1. MDP and RL Choice Justification

In contrast to supervised and unsupervised learning paradigms, which treat registry artefacts as independent, static samples, modelling WR forensics as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) inherently captures both the temporal dependencies and decision-making requirements of a live investigation. An MDP formalism specifies a set of discrete states (e.g., registry key configurations, volatile memory snapshots), actions (e.g., key-value extraction, anomaly scoring, timeline correlation), transition probabilities, and rewards, thereby framing registry analysis as a sequential optimisation problem rather than isolated classification or clustering tasks.

First, supervised classifiers or deep anomaly detectors optimise per-instance loss functions and lack mechanisms to propagate delayed signals: a benign key modification may only become suspicious in light of subsequent changes. In an RL-driven MDP, reward signals—assigned for uncovering correlated evidence or reducing case uncertainty—are back-propagated through state transitions, enabling credit assignment across long event chains. This ensures that policies learn to prioritise early, low-salience indicators that lead to high-impact findings downstream.

Second, unsupervised methods (e.g., clustering, autoencoders) identify outliers based on static distributions but cannot adapt online to evolving attacker tactics. An RL agent maintains an exploration–exploitation balance, continuously refining its decision policy as new registry patterns emerge. This on-policy learning adapts to zero-day techniques without manual rule updates, overcoming the brittleness of static, rule-based systems.

Finally, the explicit definition of an MDP reward function allows multi-objective optimisation—for instance, maximising detection accuracy while minimising analyst workload—whereas supervised models cannot natively reconcile such competing goals. By unifying sequential decision-making, delayed-reward learning, and adaptive policy refinement, MDP-based RL provides a theoretically grounded and practically scalable framework uniquely suited to the dynamic complexities of WR forensics.

To sum up, the choice of MDP is due to the offered structured approach for modelling and optimising sequential decision making, which is a characteristic of digital forensic investigations where analysts are requested to make informed decisions in the presence of complex WR and volatile memory analysis [

4].

3.2. WR and Volatile Data Markov Decision Process

A Markov Decision Process (MDP) is commonly used to mathematically formalise RL problems. The key components of an MDP include the state space, action space, transition probabilities, and reward function. This formalism provides a structured approach to implement RL algorithms, ensuring that agents can learn robust policies for complex sequential decision-making tasks across diverse application domains[

53]. Markov decision process (MDP) is widely adopted to model sequential decision-making process problems to automate and optimise these processes [

56]. The components of an MDP environment are summarised in Equation (

1):

A

Markov Decision Process, MDP, is a 5-tuple

where:

Value Function: Value function describes

how good it is to be in a specific state

s under a certain policy

. For MDP:

To achieve the optimal value function, WinRegRL Agent will calculate the expected reward return when starting from

s and following

, but account for the cumulative discounted reward.

WinRegRL Agent at each step t receives a representation of the environment’s state, , and it selects an action . Then, as a consequence of its action, the agent receives a reward, .

Policy: WinRegRL

policy is a mapping from a state to an action

That is the probability of selecting an action if .

Reward: The total

reward is expressed as:

where

is the

discount factor and

H is the

horizon, which can be infinite.

3.3. Markov Decision Process (MDP) Formulation

The WinRegRL framework models the WR investigation process as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), defined by the tuple :

States (S): Each state represents a snapshot of the investigation environment, including Registry artefacts such as keys, values, and timeline-related entries. States also capture associated metadata extracted from volatile memory and hive files.

Actions (A): The set of forensic operations available to the agent, including search, parse, correlate, filter, and export. Each action manipulates or interrogates the current state to progress the investigation.

Transition Dynamics (T): A probabilistic function that defines the likelihood of moving from state s to state after executing action a. Transitions reflect how the investigation progresses as new evidence is discovered, filtered, or correlated.

Reward Function (R): A mapping assigning numerical values to the outcomes of actions in a given state. Higher rewards are assigned to critical indicators of compromise (IOCs) or highly relevant artefacts, while lower rewards correspond to non-relevant or redundant findings.

This explicit formulation ensures the investigation workflow is reproducible and aligns with reinforcement learning principles, enabling the optimisation of both time efficiency and evidential accuracy.

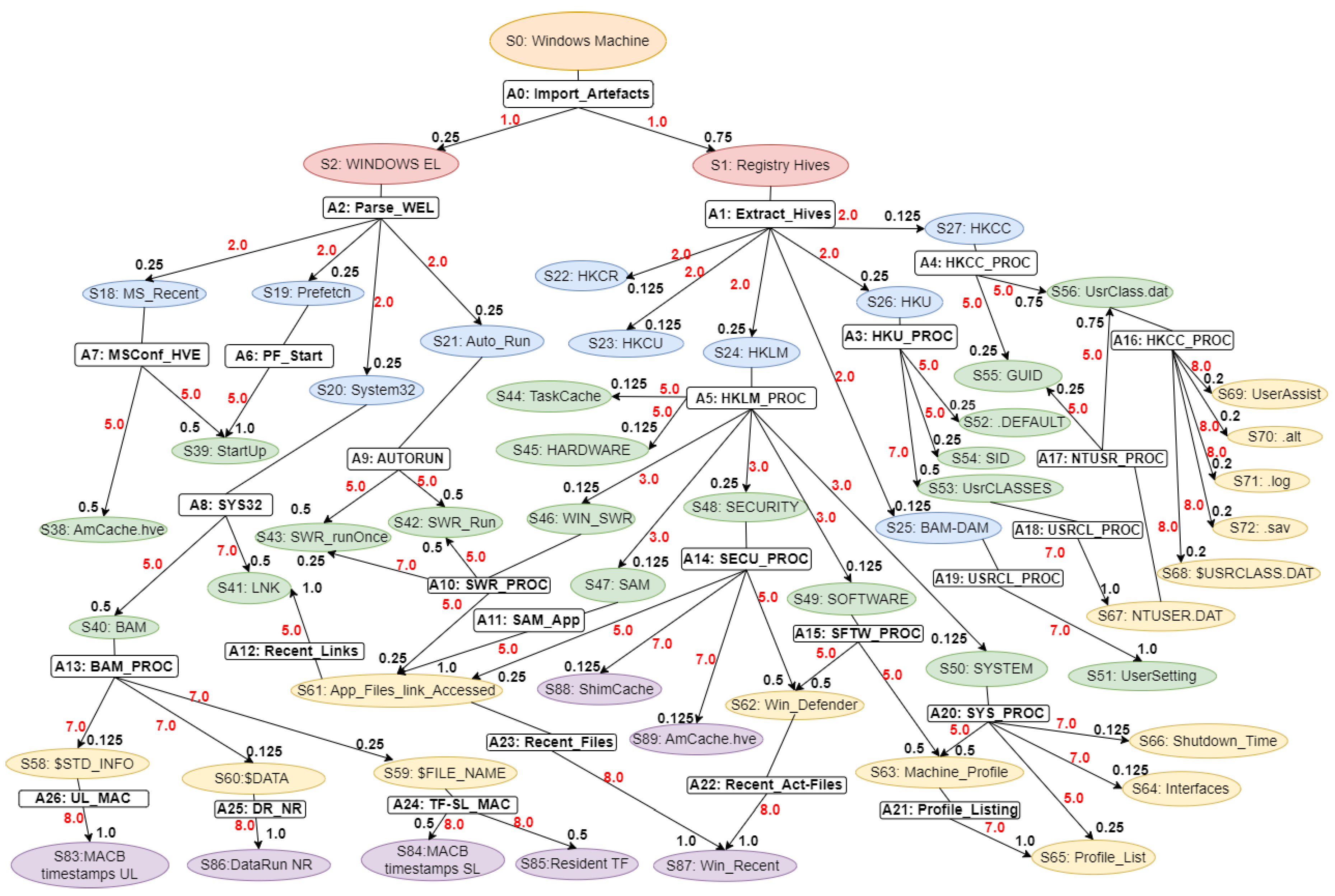

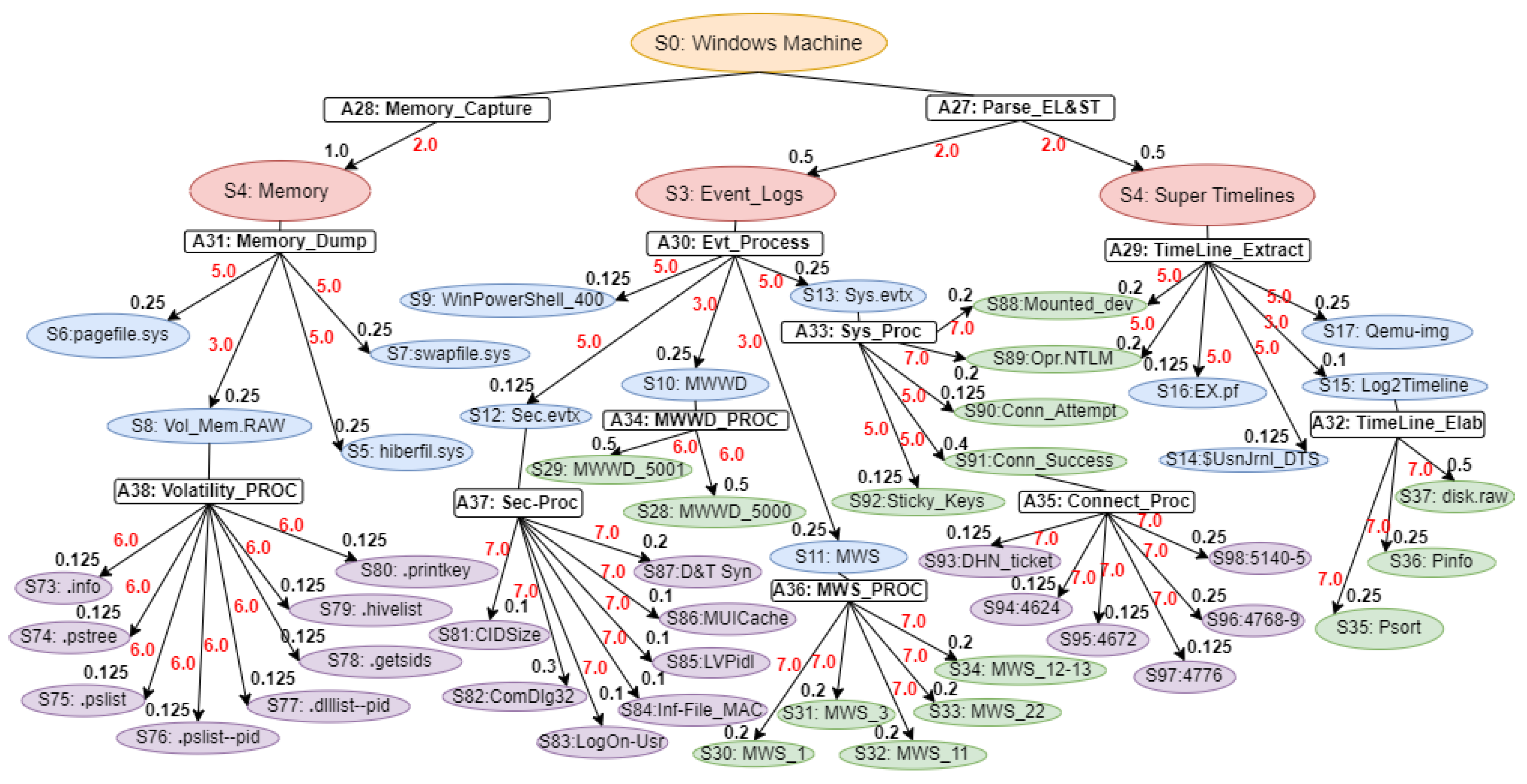

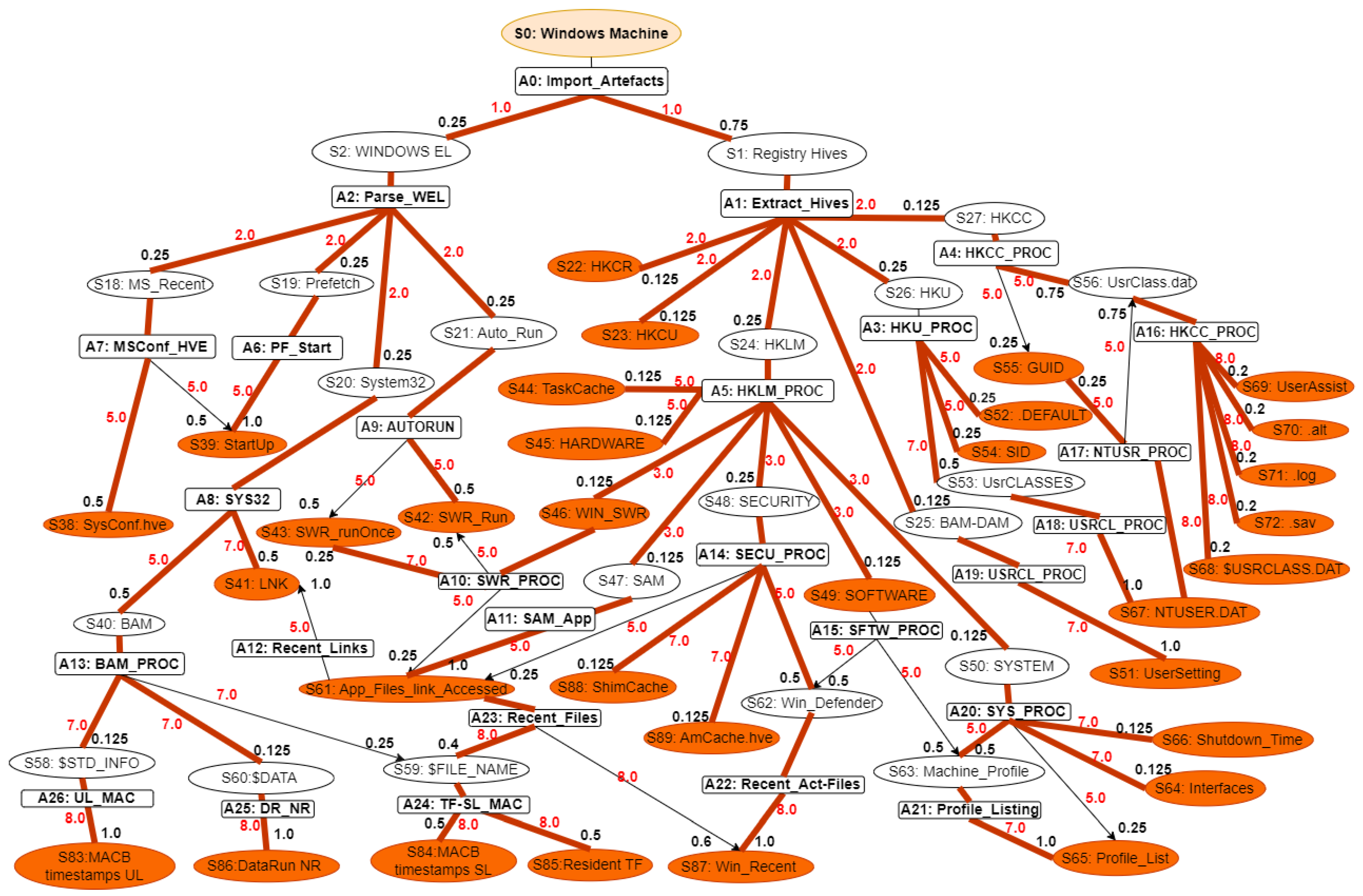

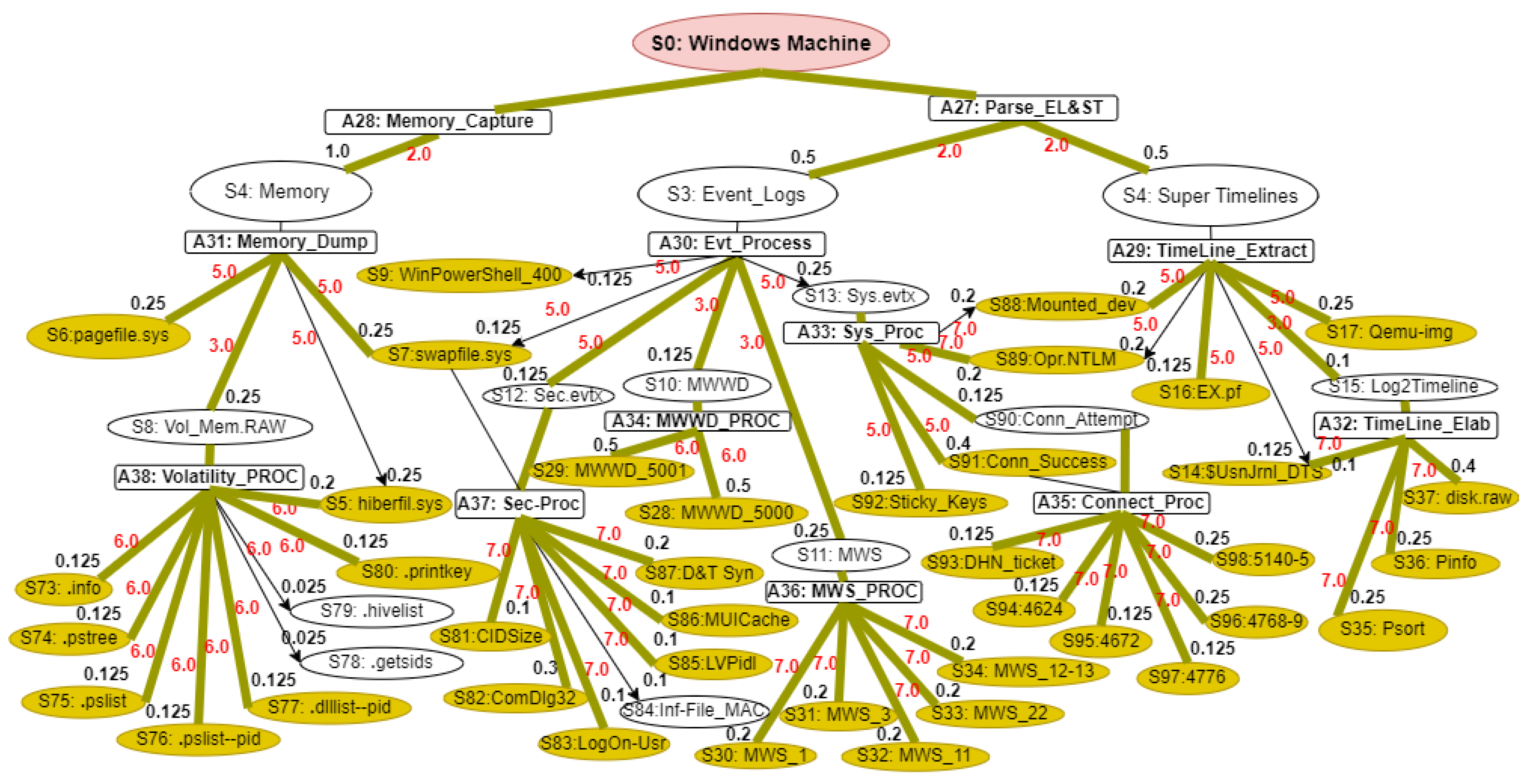

Our proposed WinRegRL MDP, illustrated in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, representation is unique and distinct by the complete capturing of the Registry Forensics and Timeline features of allowing the RL agent to act even when it fails to identify the exact environment state. The environment for RL in this context would be a simulation of the Windows OS registry activities combined with real-world data logs. This setup should allow the agent to interact with a variety of registry states and receive feedback. The MDP model elaboration is operated following SANS, including File Systems, Registry Forensic, Jump Lists, Timeline, Peripheral Profiling and Journaling as summarised in

Table 4.

State Space: In WR and volatile memory forensics, the state space refers to the status of a system at some time points. Such states include the structure and values of Registry keys, the presence of volatile artefacts, and other forensic evidence. The state space captures a finite and plausible set of such abstractions, allowing the modelling of the investigative process as an MDP. For example, states could be “Registry key exists with specific value” or “Volatile memory contains a given process artefact.”

Actions Space: Nodes refer for Actions labelled are states (: Windows Machine, : Registry Hives). The actions denote forensic steps that move the system from one state to another. Examples of these are Registry investigation, memory dump analysis, or timeline artefact correlation. Every action can probabilistically progress to one of many possible states. The latter reflects inherent uncertainties of forensic methods: for example, querying a given Registry key might show some value with some probability and guide the investigator with future actions.

Transition Function: The transition function models the probability of moving from one state to another after acting. For example, examining a process in memory might lead to identifying associated Registry keys or other volatile artefacts with a given likelihood. The transition probabilities capture the dynamics of the forensic investigation, reflecting how evidence unfolds as actions are performed.

Reward Function: The reward function assigns a numerical value to state-action pairs, representing the immediate benefit obtained by taking a specific action in a given state. In the forensics context, rewards can quantify the importance of discovering critical evidence or reducing uncertainty in the investigation process. For example, finding a timestamp in the Registry that corresponds to one of the known events can be assigned a large reward for solving the case.

This MDP framework provides a structured approach for modelling and optimising forensic investigations, enabling analysts to make statistically informed decisions in the presence of complex WR and volatile memory analysis. The MDP model elaboration is operated following SANS, including File Systems, Registry Forensic, Jump Lists, Timeline, Peripheral Profiling and Journaling as summarised in

Table 4.

The problem of registry analysis can be defined as an optimisation problem focused on the agent, where it is to determine the best sequence of actions to maximise long-term rewards, thus obtaining the best possible investigation strategies under each system state. Reinforcement Learning (RL) provides a broad framework for addressing this challenge through flexible decision-making in complex sequential situations. Over the past decade, RL has revolutionised planning, problem-solving, and cognitive science, evolving from a repository of computational techniques into a versatile framework for modelling decision-making and learning processes in diverse fields [

52]. Its adaptability has, therefore, stretched beyond the traditional domains of gaming and robotics to address real-world challenges ranging from cybersecurity to digital forensics.

In the proposed MDP model, an investigative process can be modelled as a continuous interaction between an AI agent controlling the forensic tool and its environment WR structure. The environment is formally defined by the set of states representing the registry’s hierarchical keys, values, and metadata; the agent, on the other hand, selects actions in a number of states at scanning, analysing, or extracting data from it. Every action transitions the environment to a new state and provides feedback in the form of rewards, which guide the agent’s learning process.

The sequential decision-making inherent in registry forensics involves navigating a series of states, from an initial registry snapshot to actionable insights. Feedback in this context includes positive rewards for identifying anomalies, detecting malicious artefacts, or uncovering system misconfigurations and negative rewards for redundant or ineffective actions. The RL agent will learn how to optimise its analysis by interacting iteratively with the environment and refining its policy; hence, it will raise the efficiency of finding important forensic artefacts systematically. That would automate and speed up registry analysis, additionally making it adaptive to changing attack patterns, which makes RL a very valuable tool for modern WR forensics.

RL enables an autonomous system to learn from its experiences using rewards and punishments derived from its actions. By exploring its environment through trial and error, the RL agent refines its decision-making process [

50]. As training RL agents requires a large number of samples from an environment to reach human-level performance [

45], we have opted for WinRegRL for an efficient approach by adopting model-based RL instead of training an agent’s policy network using actual environment samples. We only use dataset samples to train a separate model supervised by a certified WR Forensics expert, having acquired GCFE or GCFA. This phase enabled us to predict the environment’s behaviour, and then use this transition dynamics model to generate samples for learning the agent’s policy [

16].

3.4. Reinforcement Learning

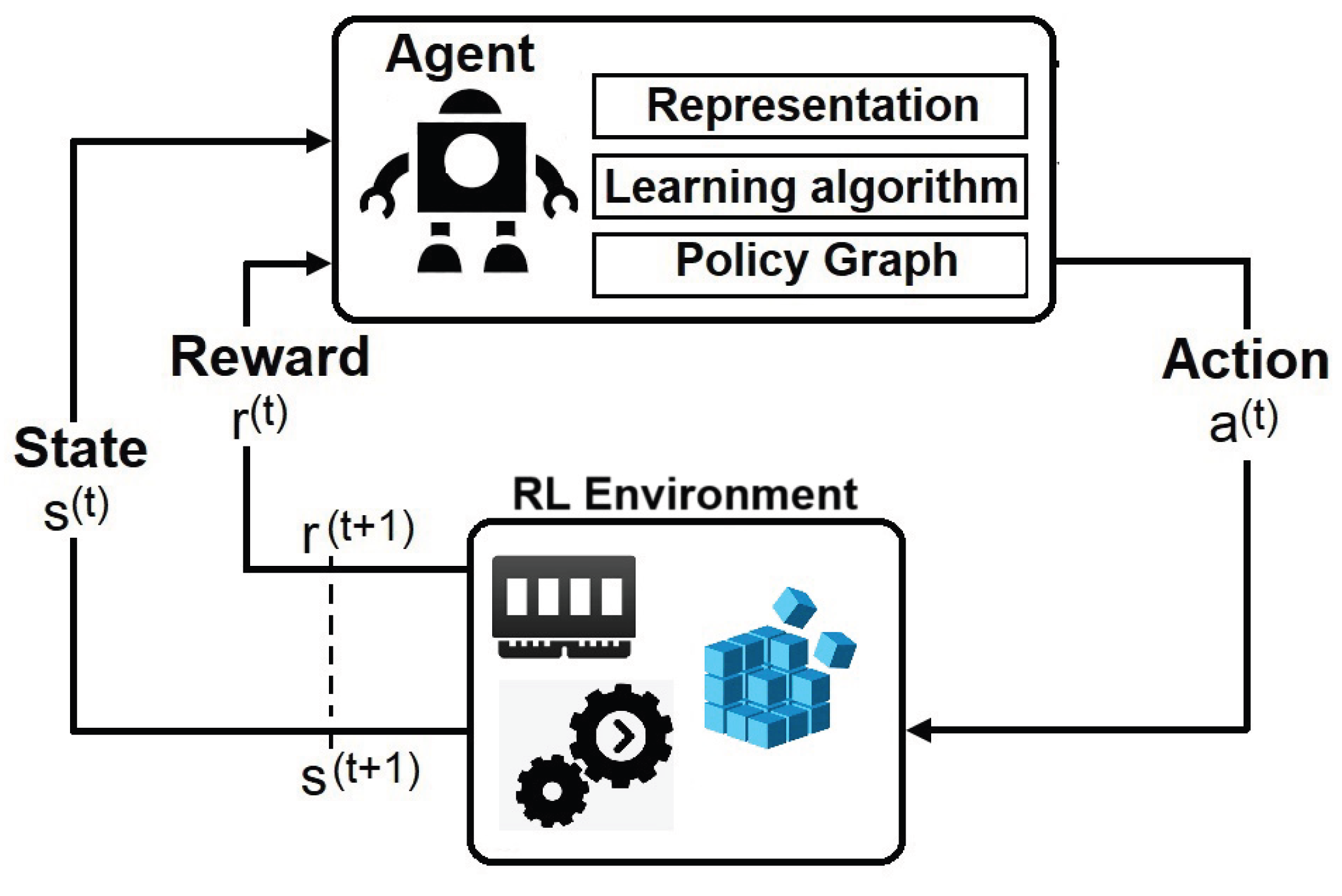

In this system, an RL agent interacts with its surround in a sequence of steps in time : (1) the agent receives a representation of the environment (state); (2) selects and executes an action; (3) receives the reinforcement signal; (4) updates the learning matrix; (5) observe the new state of the environment.

Figure 3.

The Reinforcement Learning conceptual framework in the context of WR and Volatile Data Forensic analysis.

Figure 3.

The Reinforcement Learning conceptual framework in the context of WR and Volatile Data Forensic analysis.

The RL Agent at each step t receives a representation of the environment’s state, , and it selects an action . Then, as a consequence of its action, the agent receives a reward, . RL is about learning a policy () that maximises the reinforcement values. A policy defines the agent’s behaviour, mapping states into actions. The -greedy method is an example of the action selection policy adopted in RL. We are seeking an Exact solution to our MDP problems and initially considered the following methods:

Value Iteration

Policy Iteration

Linear Programming

3.4.1. Value Iteration and Action-Value (Q) Function

We denoted the expected reward for state and action pairs in Equation (

6).

3.4.2. Optimal Decision Policy

WinRegRL optimal value-action decision policy is formulated by the following function:

We can then redefine

, Equation (

3), using

, Equation (

7):

This equation conveys that the value of a state under the optimal policy

must be equal to the expected return from the best action taken from that state. Rather than waiting for V(s)V(s) to converge, we can perform policy improvement and a truncated policy evaluation step in a single operation [

29].

|

Algorithm 1 WinRegRL Value Iteration |

- Require:

State space S, action space A, transition probability , discount factor , small threshold

- Ensure:

Optimal value function and deterministic policy

- 1:

Initialization: - 2:

▹ Initialize value function - 3:

- 4:

repeat - 5:

- 6:

for all do

- 7:

▹ Store current value of s

- 8:

- 9:

▹ Update the maximum change - 10:

end for

- 11:

until ▹ Check for convergence - 12:

- 13:

Extract Policy: - 14:

for all

do

- 15:

- 16:

end for - 17:

Output: Deterministic policy and value function

|

Monte Carlo (MC) is a

model-free method, meaning it does not require complete knowledge of the environment. It relies on

averaging sample returns for each state-action pair [

29].

3.5. Core Algorithmic Components

WinRegRL-Core: This module is the reinforcement learning engine responsible for solving the formulated MDP efficiently. It alternates between value iteration and Q-learning, combining the convergence properties of model-based planning with the adaptability of model-free learning. Value iteration is applied in the early stages when the state transition model is known or can be accurately estimated, providing a rapid computation of an initial optimal policy. Q-learning is then employed to refine the policy when the model is incomplete or when the investigation environment evolves dynamically. This hybrid strategy accelerates convergence and maintains optimal performance across varying forensic scenarios.

PGGenExpert-Core: This expert-in-the-loop module captures and generalises decision-making patterns from experienced digital forensic practitioners. It constructs

policy graphs from sequences of expert actions taken during investigations, then abstracts and generalises these policies for storage in a knowledge base. These reusable strategies enable WinRegRL to leverage accumulated human expertise, allowing faster adaptation to similar or partially related cases in the future. The integration of PGGenExpert-Core ensures that the system benefits from both automated reinforcement learning optimisation and the nuanced judgment of human experts.

Figure 4 illustrates the sequential learning approach used in WinRegRL, showing the step-by-step interaction between the agent, environment, and policy update process.

3.5.1. Bellman Equation

An important recursive property emerges for both Value (

2) and Q (

6) functions if we expand them [

51].

3.5.2. Value Function

Similarly, we can do the same for the Q function:

3.5.3. Policy Iteration

We can now find the optimal policy

|

Algorithm 2 WinRegRL Policy Iteration |

Require: State space S, action space A, transition probability , discount factor , small threshold

Ensure: Optimal value function and policy

- 1:

Initialization: - 2:

▹ Initialize value function - 3:

▹ Initialize arbitrary policy - 4:

- 5:

repeat - 6:

Policy Evaluation:

- 7:

- 8:

for all do

- 9:

- 10:

- 11:

- 12:

end for

- 13:

until ▹ Repeat until value function converges - 14:

- 15:

Policy Improvement: - 16:

- 17:

for alldo

- 18:

- 19:

- 20:

if then

- 21:

- 22:

end if

- 23:

end for - 24:

- 25:

if

then

- 26:

return and

- 27:

else - 28:

go to Policy Evaluation - 29:

end if

|

3.6. WinRegRL Framework Design and Implementation

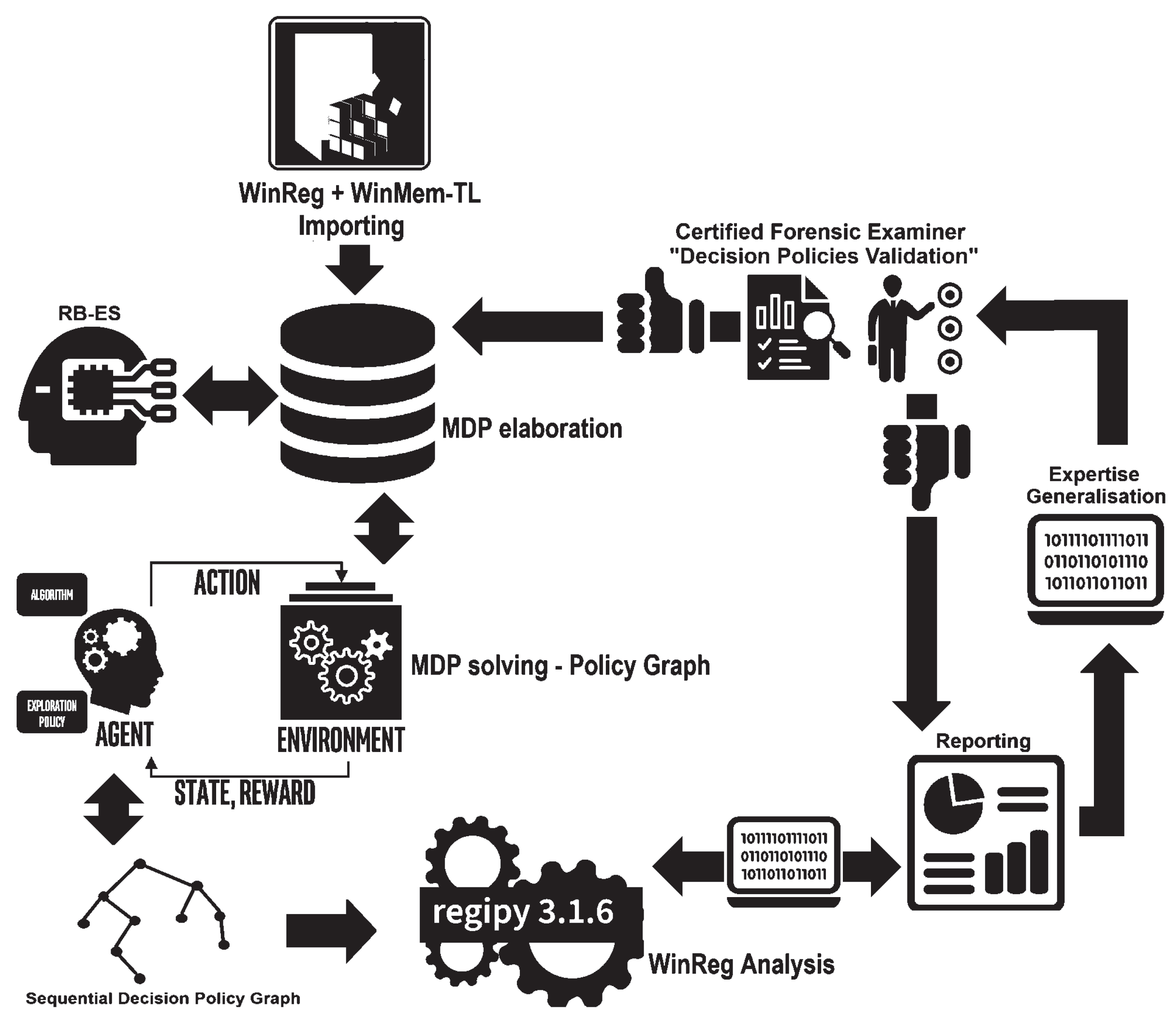

The proposed WinRegRL framework illustrated in

Figure 5 integrates data from the WR and volatile memory into a decision-making system that models these data as MDP Environments. It also relies on Rule-Based AI (RB-AI) and other ML algorithms during the phase of MDP environments elaboration. It enables forensic examiners to validate decisions, identify patterns in fraudulent or malicious activities, and generate actionable reports.

Figure 5 provides a detailed diagram illustrating WinRegRL functioning, covering WR Hives and Volatile Data Parsing, MDP environment elaboration, RL and RB-AI functioning, as well as the human expert (GCFE) validation. The Diagram only consider WR (WinReg) analysis and volatile memory (WinMem-TL) data for elaborating MDP envisionments. This framework highlights an iterative decision-making process that combines expert knowledge with Reinforcement Learning and the use of automated forensic tools to enhance the analysis and detection of fraudulent or anomalous activities in a Windows environment.

We describe here, WinRegRL framework modular breakdown:

WinReg + WinMem-TL Importing The process begins by importing WR data and memory timelines (WinMem-TL).

MDP Elaboration The imported data is transformed into a Markov Decision Process (MDP) environment following the structure defined in Equation (

1).

MDP Solver The out-of-the-box MATLAB MDP toolbox contains various algorithms to solve the discrete-time Markov Decision Processes: backward induction, value iteration, policy iteration, and linear programming [

20]. In the case of the analysis of the WR, an MDP agent—a purple head icon with the label AGENT—interacts with the registry environment to receive state observations and reward signals to improve its decision policies [

22]. The RL agent will therefore systematically search through registry keys and values, identifying patterns and anomalies in a feedback-driven cycle of analysis. This interaction constructs a Sequential Decision Policy Graph to visualise possible actions and decision paths specific to registry analysis. An off-the-shelf MDP solver is then applied to find optimal policies, dynamically focusing on registry artefacts based on their reward importance. This methodology exposes, with great skill, hidden malicious behaviours or misconfigurations in the WR, yielding insights that are often overlooked by traditional static analysis or manual investigation techniques. The algorithm functioning is detailed in

Section 3.9

3.7. Expertise Capturing and Generalisation

A Rule-Based AI (RB-AI) with an online integrator that interacts with the RL MDP-solver, likely applying expert knowledge or predefined rules to assist in elaborating decision policies based on the imported data [

47].

3.7.1. Expertise Generalisation

If the generated policies are inadequate, they undergo further Expertise Generalisation, where more complex or nuanced decision-making logic is applied to better handle fraud detection or anomaly identification.

3.7.2. Reporting and Analysis

The validated results are compiled into a report for decision-making or further investigation. The process feeds back into WinReg Analysis using Regipy 3.1.6, a tool for forensic analysis of WR hives, ensuring continual refinement and improvement of the decision-making model.

3.8. Human Expert Validation Module

The generated decision policies are validated by a Certified Forensic Examiner holding at least GIAC GCFE or GCFA to ensure that the automatically generated decision policies are correct and appropriate. If the policies are valid, they receive a “thumbs up”; if not, further generalisation or adjustments are needed (denoted by the “thumbs down” icon).

3.9. WinRegRL-Core

WinRegRL-Core, as illustrated in Algorithm 3, is the Core Reinforcement Learning algorithm where the RL Agent is trained on a model MDP—the latter created based on some given data about the WR. The algorithm initialises the policy, value function, and generator with random values first, then updates the policy of the agent in each iteration based on the computed state-action values by using either policy iteration or value iteration. Policy iteration directly updates the policy by choosing those actions with maximum Q-values, while value iteration is an iterative refinement of a value function V(s). Q-learning is used so the RL Agent would explore the environment and update a Q-table while following the epsilon-greedy approach for balancing exploration and exploitation. WinRegRL-Core incorporates increasingly improved iterations of the critic, or value function, and the generator, or policy, for the refinement of the policy towards the selection of appropriate actions for the maximisation of cumulative rewards. Convergence is verified based on whether the difference between the predicted and target policy is less than a specified threshold, which demonstrates that ♢ is the optimal policy. The last trained generator and the critic represent the optimised policy and value function, respectively, used for decision-making within the MDP environment.

For non-stationary problems, the Monte Carlo estimate for, e.g,

V is:

where

is the learning rate, how much we want to forget about past experiences.

|

Algorithm 3 WinRegRL-Core |

Require: MDP , where S is the set of states derived from WR data, A is the set of actions, P is the transition probability matrix, R is the reward function, and is the discount factor; Local iterations I, learning rate for Critic , learning rate for Generator , gradient penalty

Ensure: Trained Critic and Generator for the optimal policy

- 1:

Initialize Generator with random weights - 2:

Initialize Critic (value function) for each

- 3:

Initialize policy arbitrarily for each

- 4:

for iteration to I do

- 5:

while MDP not converged do

- 6:

for each state do

- 7:

for each action do

- 8:

Compute Bellman update for expected reward

- 9:

end for

- 10:

Update policy with max Q-value

- 11:

Update value

- 12:

end for

- 13:

if using Policy Iteration then

- 14:

Check for stability of ; if stable, break

- 15:

else if using Value Iteration then

- 16:

Check convergence in ; break if changes are below threshold - 17:

end if

- 18:

end while

- 19:

if Q-Learning is needed then

- 20:

Initialize Q-table for all

- 21:

for each episode until convergence do

- 22:

Observe initial state s

- 23:

while episode not done do

- 24:

Choose action a using -greedy policy based on

- 25:

Execute action a, observe reward r and next state

- 26:

Update

- 27:

- 28:

end while

- 29:

end for

- 30:

end if

- 31:

Train Critic to update value function - 32:

Train Generator to optimize policy using updated critic values - 33:

Confirm convergence of the target policy , break

- 34:

end for - 35:

return Trained Generator and Critic for optimized policy

|

3.10. PGGenExpert-Core

PGGenExpert is the proposed Expertise Extraction, Assessment and Generalisation Algorithm 4, it converts WinRegRL Policy Graph to generalised policies independently of the covered case for future use, processes and corrects a state-action policy graph derived from reinforcement learning on WR data. It starts by taking the original dataset, a complementary volatile dataset, and an expert-corrected policy graph as inputs. The algorithm first creates a copy of the action space and iterates over each feature to ensure actions remain within the valid range, correcting any out-of-bounds actions. Next, it addresses binary values by identifying incorrect actions that differ from expected binary states and substitutes them with expert-provided corrections. For each state-action pair, it then adjusts the action values so that only the highest-probability action remains non-zero, effectively refining the policy to select the most relevant actions. Finally, the algorithm returns the corrected and generalised policy graph, providing an updated model of action transitions that aligns with expert knowledge and domain constraints.

|

Algorithm 4 GenExpert: Policy Graph Expertise Extraction, Assessment and Generalisation Algorithm |

Require: Original WR data with n instances and d features, Complementary volatile data Y with shape matching W, and State-to-Action Policy Graph Z. Expert-corrected general policy graph C.

Ensure: updated transition probabilities in the MDP model based on corrected actions.

- 1:

procedure Correct_Action_State_PG Maping() - 2:

Copy of the action space:

- 3:

for do ▹ Handle missing and out-of-range actions - 4:

- 5:

- 6:

▹ Bound actions within valid range - 7:

end for

- 8:

for do ▹ Correct binary values - 9:

▹ Identify invalid actions - 10:

▹ Replace with expert-corrected values - 11:

▹ Set all but highest value in state-action vector to 0 - 12:

end for

- 13:

▹ Extract generalized policy graph based on highest value action - 14:

return ▹ Return updated state-action policy graph - 15:

end procedure

|

4. Testing, Results and Discussion

4.1. Testing Datasets

To test WinRegRL, we opted for different DFIR datasets.

Table 5 summarises the WinRegRL Testing Datasets, which were a mixed selection of four (04) datasets that cover multiple Windows architectures and versions. In general, three datasets are widely adopted in DFIR research:

CFReDS: The NIST Computer Forensic Reference DataSet (CFReDS) Portal is a comprehensive resource for accessing documented digital forensic image datasets and supporting tasks such as tool testing, practitioner training, and research. Each dataset includes descriptions of significant artefacts and can be searched by year, author, or attributes. The portal features collections developed by NIST for projects like Computer Forensic Tool Testing (CFTT) and Federated Testing, alongside contributions from other sources. These datasets enable users to evaluate forensic tools, develop expertise, train professionals, and conduct custom studies, offering a valuable foundation for advancing digital forensics practices [

13].

TREDE and VMPOP: The dataset includes four WR files from different PCs, providing critical insights for system security and digital forensics. The WR, storing essential system and application configurations, helps identify vulnerabilities and forensic artefacts. As the PCs were inactive during extraction, no active threats were present. Three files are raw datasets directly extracted using Windows command-line tools, maintaining their original integrity. The fourth file is a reformatted key-value pair version of one raw dataset, preserving its semantic accuracy [

9]. This structure supports in-depth analysis, uncovering traces of unauthorised access, malware persistence, and other forensic evidence.

DWosFA: This dataset contains Windows forensic artefacts, including the NTFS file system and event log records. This dataset was created from disk images of devices used in CTF competitions, mainly focusing on the forensics of the Windows OS and analysis of user activity. Security incident timelines were extracted using the Plaso tool, allowing the creation of a timeline of events in order from these disk images. The timeline attributes were then converted into binary values for easier data analysis and ML. The final dataset is divided into 13 separate files, saved in CSV format for organised analysis [

11].

4.2. Reinforcement Learning Parameters and Variables

The WinRegRL reinforcement learning model uses important parameters to optimise decision-making. The discount factor of

0.99 seeks long-term rewards by properly weighting immediate and future gains. Decision epochs of

200 were selected to determine the maximum number of steps per episode. The value function tolerance is set to

0.001, which determines the precision of convergence, and epsilon of 0.00001, which controls the threshold of value improvement. The learning generator rate was set between [0–99%], which determines the change of policies; the reward value between [ -10, +100 ] that act as the feedback mechanism, The choice of MDP rewards ranging from -10 to 100 is purely empirical, it was set experimentally (trial/error) and not derived from theory or formal optimisation. In our research, theoretical reward design was impractical and thus we based it on observed outcomes (investigative tasks’ success) to allocate reward within that range. Expertise thresholds are set between [0–99%] and interpolated samples of 0.01 to enhance performance. Generalisation loss is set between [0, +100] to evaluate how well expertise is generalised. A buffer size of 100,000 allows a memory replay, which is controlled by variant batch sizes [1024, 512, 256].

Table 6 summarises the variables and parameters we selected for running WinRegRL Experiments.

4.3. WinRegRL Results

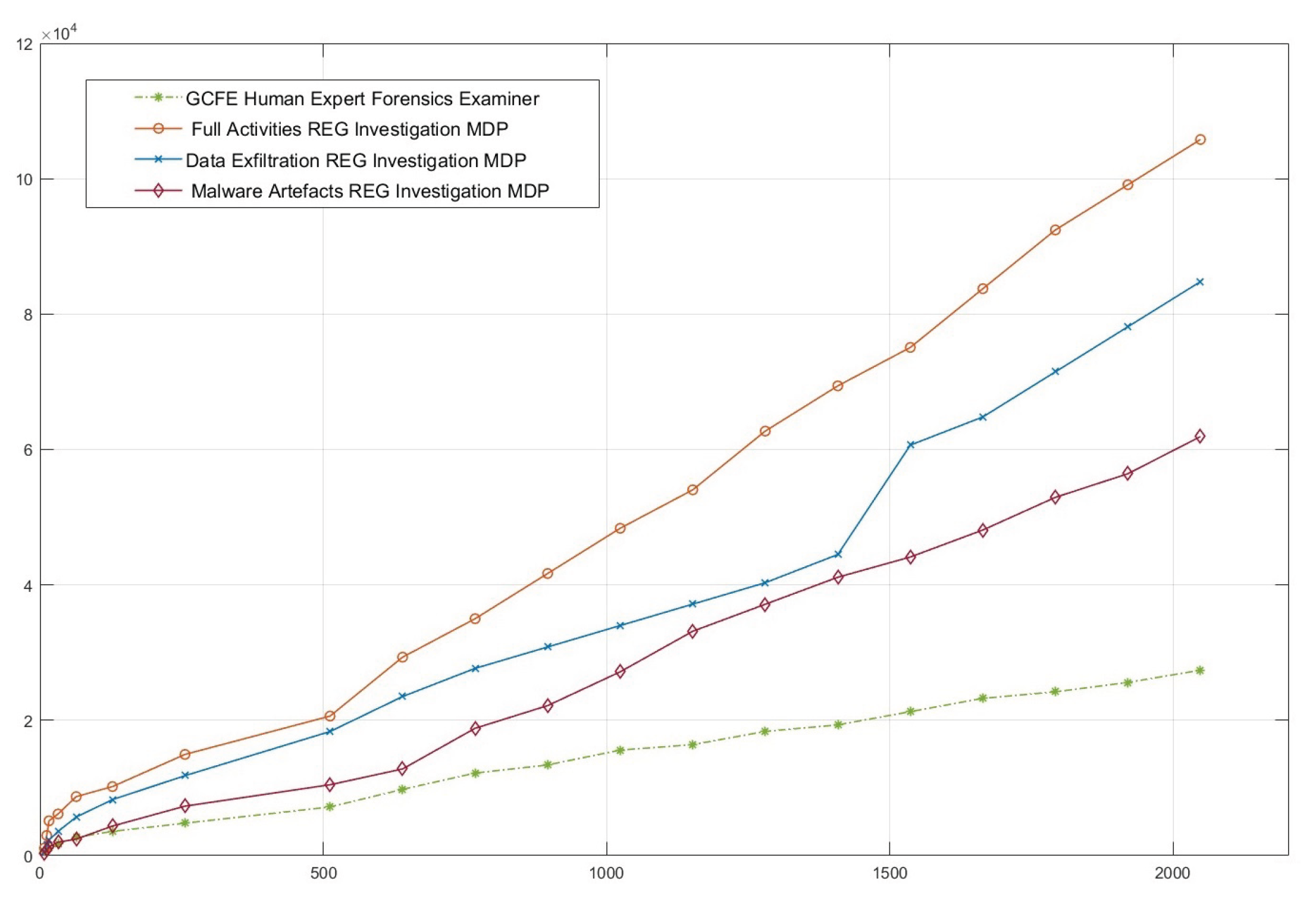

Figure 6 illustrates the evaluation of the WinRegRL Framework’s performance in different scenarios of Markov Decision Processes (MDPs), including the Full Activities REG Investigation MDP, the Data Exfiltration REG Investigation MDP, and the Malware Artefacts REG Investigation MDP. It is contrasted with the baseline time taken by a GCFE Human Expert Forensics Examiner (green dashed), used only as a reference point. The horizontal axis represents the WR size in MB, while the vertical axis represents the time in seconds it took to run the respective MDP tasks. The results show that Full Activities REG Investigation MDP always takes the longest time, followed by Data Exfiltration REG Investigation MDP, then Malware Artefacts REG Investigation MDP—showing how different the task complexities are. Notably, the GCFE Human Expert shows a linear and considerably lower time requirement in smaller datasets but points out scalability limitations when dealing with larger registries.

On the other hand,

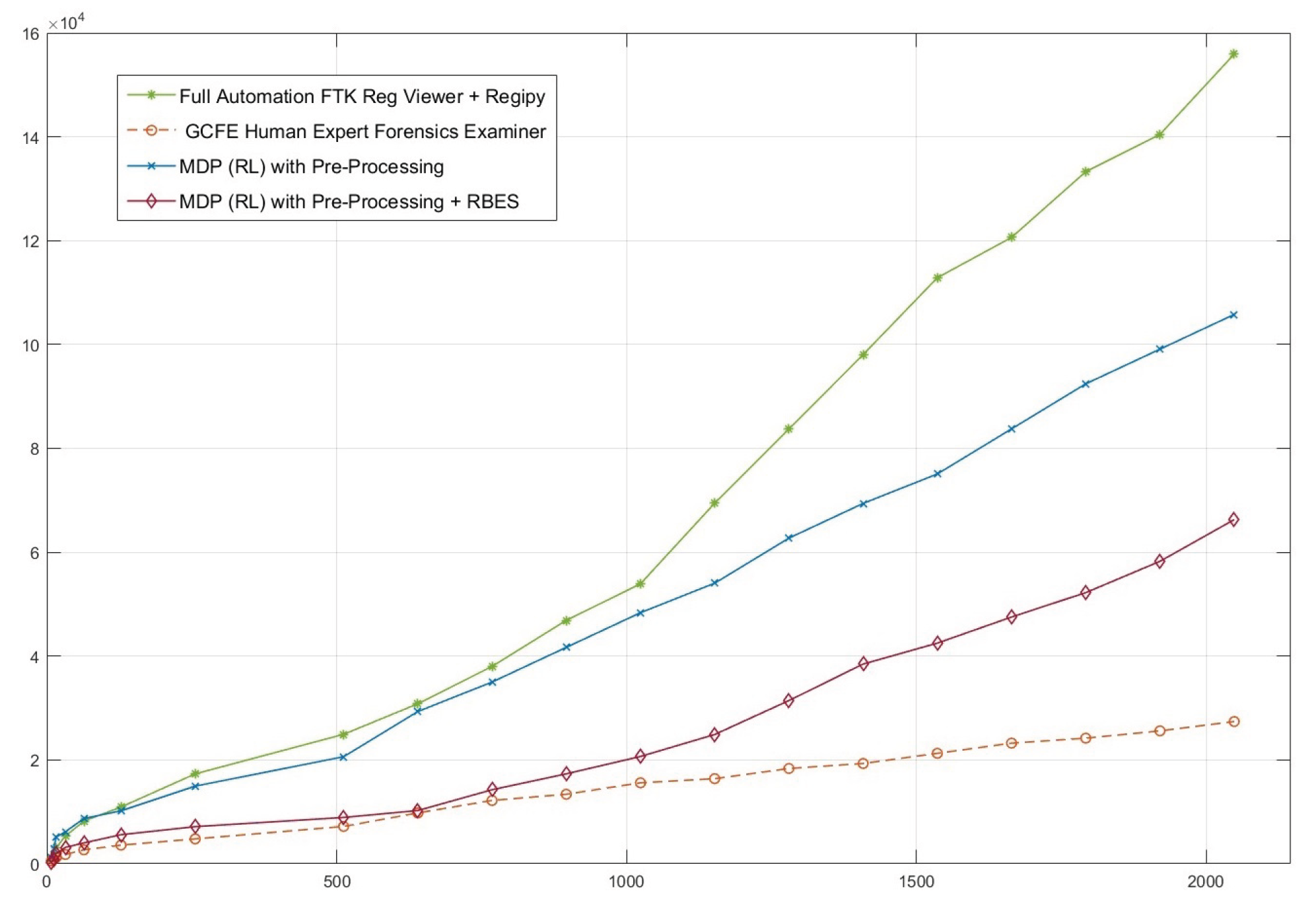

Figure 7 shows a comparative analysis of the WinRegRL Framework’s performance regarding various WR sizes (on the x-axis) and the time required to complete forensic analyses (on the y-axis, in seconds). Four approaches are compared: Full Automation FTK Reg Viewer with Regipy, GCFE Human Expert Forensics Examiner, MDP (RL) with Pre-Processing, and MDP (RL) with Pre-Processing and RB-AI. Results show that the fully automated approach vastly outperforms all others, with a sharp rise in efficiency as the registry size scales. The MDP (RL) with Pre-Processing follows, showing moderate scalability, while the inclusion of RB-AI further optimises performance but remains below full automation. By comparison, the GCFE Human Expert Forensics Examiner method is the least efficient, with the investigation time increasing linearly and falling behind both automated and reinforcement learning-based methods by a large margin. This comparison empowers the scalable nature and effectiveness of automated and AI-driven approaches in handling large-scale registry investigations.

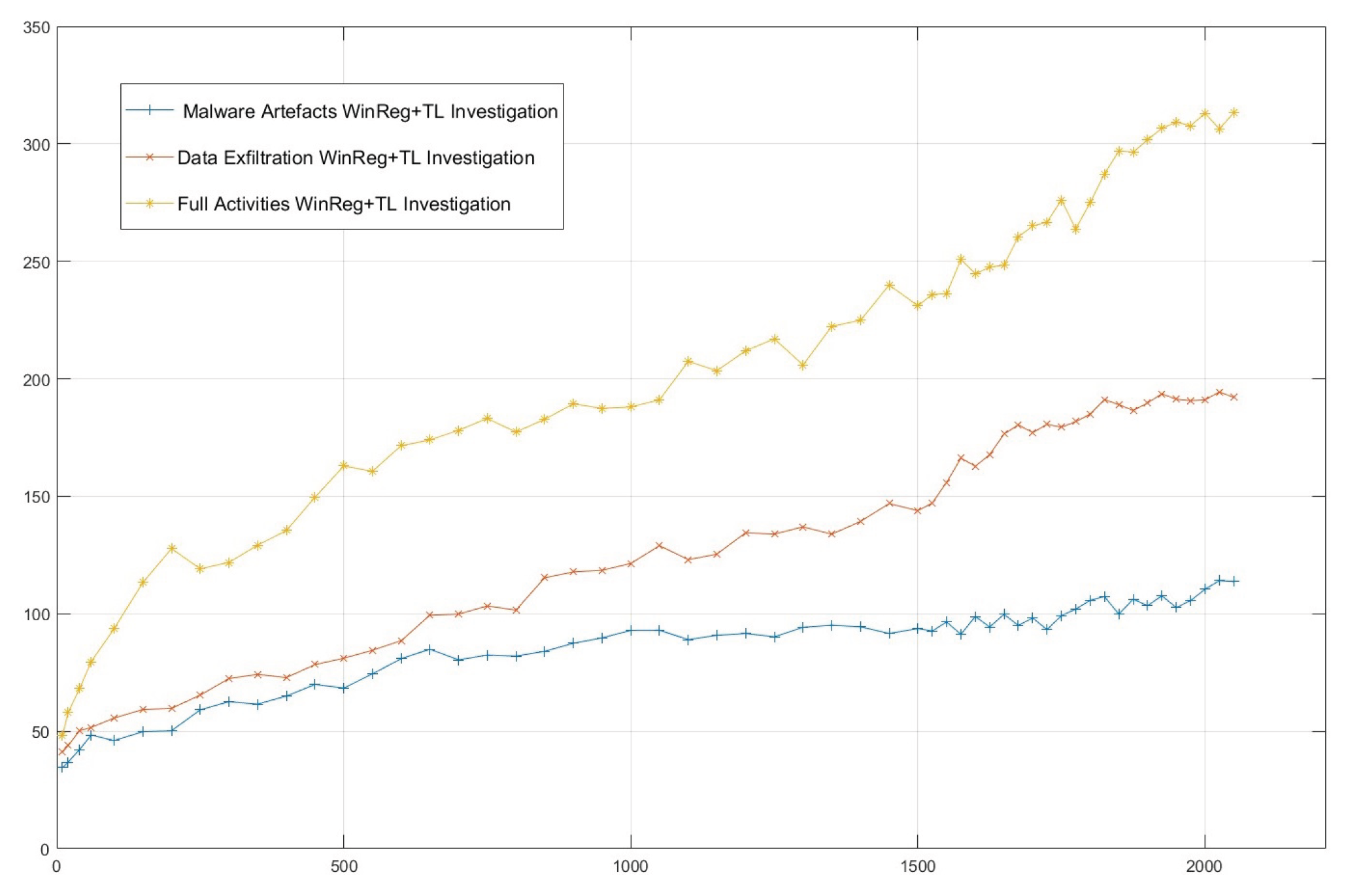

Figure 8 shows the efficacy of the WinRegRL Framework in three cases of investigation, including malware artefacts, Full WR with Timeline (WinReg+TL) Investigation, data exfiltration WinReg+TL Investigation, and Full Activities WinReg+TL Investigation. The x-axis represents the size of the WR, while the y-axis shows the number of artefacts found during each investigation. Results show that the Full Activities WinReg+TL Investigation always finds the most artefacts, and this number goes up quickly as the registry size gets bigger. The Data Exfiltration WinReg+TL Investigation comes next, showing a fair rate of finding artefacts with a steady increase. On the other hand, the Malware Artefacts WinReg+TL Investigation finds the fewest artefacts with a slower growth rate and a flat level seen at larger registry sizes. These results indicate that the level of complexity and the quantity of artefacts vary in divergent investigation situations. They emphasize the fact that full-activity investigations span more ground than focused malware and data theft studies.

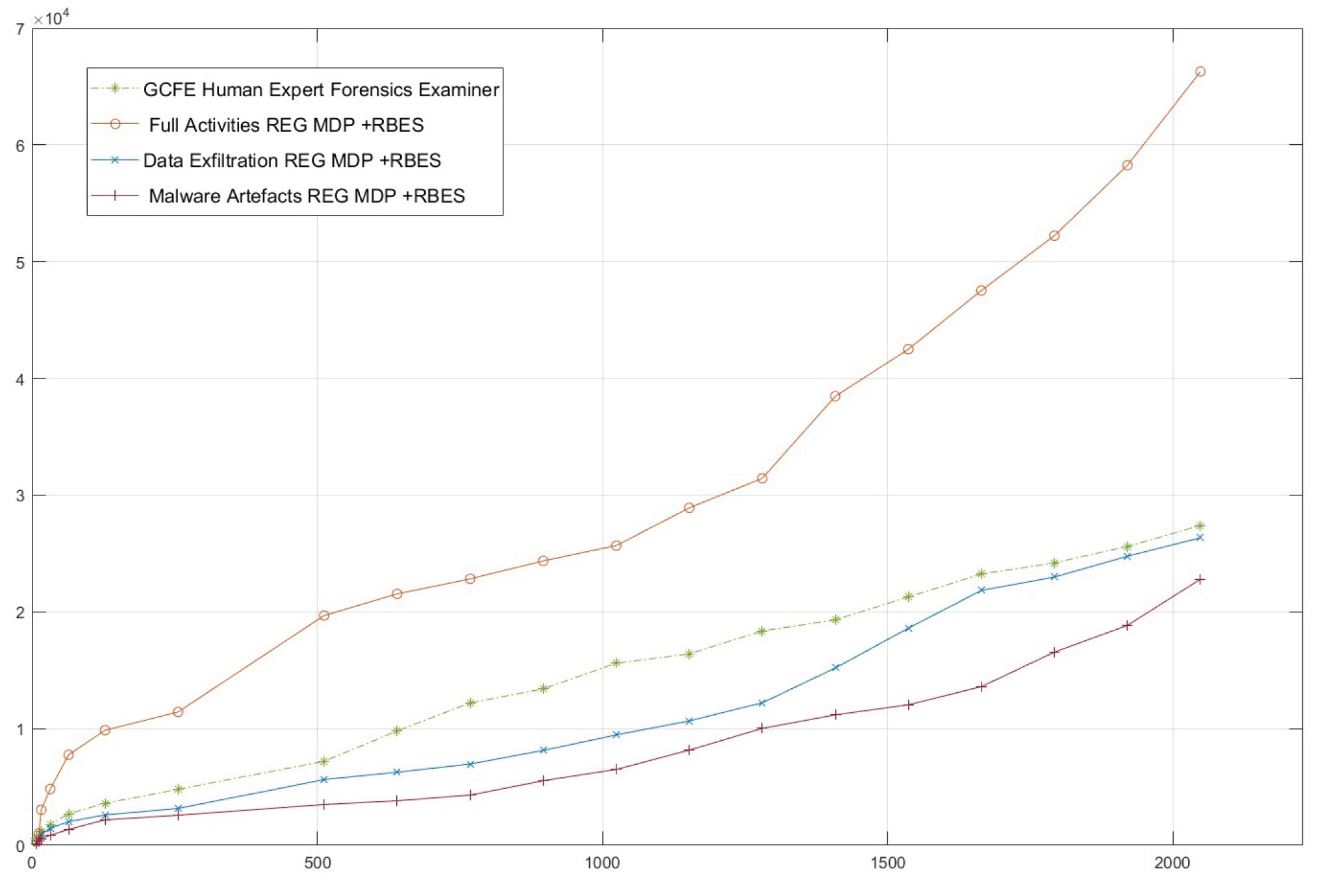

Figure 9 illustrates the performance of the WinRegRL framework tested under varying WR sizes (x-axis) against execution time in seconds (y-axis) across three scenarios: full activities, data exfiltration, and malware artefacts, in comparison to a human expert (GCFE). The results demonstrate that while the GCFE maintains consistent performance, WinRegRL outperforms in all scenarios, especially in handling larger registry sizes, with significantly lower time costs and error-free operation. The full activities scenario exhibits the highest time efficiency gain, followed by data exfiltration and malware artefacts. The findings highlight WinRegRL’s capability to deliver scalable, cost-effective, and error-free registry analysis compared to human expertise.

4.4. WinRegRL Performances Validation

Finally, we proceeded to the validation of the obtained results by running the same experiments on different forensic datasets. We summarised WinRegRL accuracy and performance benchmarking compared with industry tools when tested using the aforementioned four datasets summarised in

Table 7, which validated the fact that WinRegRL outperforms both the automated full FTK Registry Viewer and Kroll KAPE in terms of the number of relevant artefacts discovered as well as the coverage of these later to the right evidence categories.

In terms of explainability and accuracy, we reflected WinRegRL output optimal PGs and mapped them to an expert GCFE-certified expert decision-making in terms of optimal action for each state.

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 illustrate one example from a Windows 10 full investigation both covering Registry analysis and Volatile Data timeline analysis, respectively.

4.5. Discussion

The WinRegRL framework represents a new revolution in the analysis of the WR, offering a solution that is fast, secure, and efficient for investigations of cyber incidents. Thanks to the integration of reinforcement learning into this analytical framework, WinRegRL is capable of automating key forensic and security operations while addressing the dynamic and complex nature of the WR for anomaly, malware, and misconfiguration detection, commonly exploited by cybercriminals. In this ever-changing landscape of cybersecurity, RL enables WinRegRL to continually adapt and tune its decision-making capabilities. Such dynamic adaptability improves the ability of the framework to detect cyber threats, anomalies, and suspicious registry behaviours. Cyber incidents, such as malware infections, often leave traces in the registry. WinRegRL accelerates and simplifies the identification of such threats, ensuring that responses during investigations are both fast and accurate. Traditional registry analysis is very time-consuming, error-prone, and hence risky. WinRegRL automates this process by leveraging RL to identify irregularities and suspicious activities with precision. The more the RL models see data, the better they become at recognising subtle patterns that may go unnoticed by static rule-based systems or manual methods. This ensures a scalable and error-free approach to handling registry analysis. WinRegRL significantly enhances the detection of malicious artefacts in the WR and volatile memory. Reinforcement learning-driven automation enables fast analysis of registry data, drastically reducing the time required for detection and response. Moreover, the adaptive nature of the framework allows it to stay proactive with newly emerging threats, providing very important insights into innovative attack vectors that may evade traditional approaches. By underlining the aspects of speed, safety, and accuracy, WinRegRL places itself as a fundamental tool for modern digital forensics and incident response.

4.6. Limitations of the Proposed Approach

The WinRegRL framework, while demonstrating significant improvements in efficiency, accuracy, and artefact discovery, has specific limitations that define its current scope. First, the framework has been evaluated exclusively in Microsoft Windows environments and is not currently adapted for other OSs such as macOS or Linux. Second, its performance depends on the representativeness and quality of the training datasets, meaning that accuracy may decrease in scenarios significantly different from those used in the evaluation phase. Third, the present implementation focuses on registry artefacts and volatile memories, other forensic data sources, including network traffic and complete disc images, are not directly processed. Fourth, the approach assumes that registry hives and volatile data are acquired in full and without corruption, incomplete or tampered datasets may impact performance. Finally, the rule-based component requires periodic updates to remain effective against evolving malware techniques and changes to Windows OSs. These constraints should be considered when applying WinRegRL to real-world digital investigations, and they highlight directions for future research and enhancement.

4.7. Ability to Generalise and Dynamic Environment

To address concerns about cross-version generalisation and exposure to novel threats, we will augment our evaluation pipeline to include Registry datasets drawn from multiple Windows editions (Windows 7, 8, 10, and 11) and varied configuration profiles (e.g., Home vs. Enterprise). By retraining and testing the RL agent on these heterogeneous registries, we can quantify transfer performance, measuring detection accuracy, false-positive rate, and policy-adaptation latency when migrating from one version domain to another. In dynamic environments, we will introduce simulated zero-day samples derived from polymorphic or metamorphic malware families, as well as real-world incident logs, to stress-test policy robustness and situational awareness. Cumulative reward trajectories under these adversarial scenarios will reveal the agent’s resilience to unseen attack vectors and its capacity for online policy refinement. Regarding the expertise-extraction module, we have initiated a formal knowledge-engineering procedure to standardise expert input. Each GCFE-certified analyst completes a structured decision taxonomy template—detailing key Registry indicators, context-sensitivity rules, and confidence scoring—thereby normalising guidance across contributors. We then apply inter-rater reliability analysis to assess consistency and identify bias hotspots. Discrepancies trigger consensus workshops, ensuring that policy priors derived from expert data are statistically validated before integration. This systematic approach both quantifies and mitigates subjective bias in the reward shaping process, guaranteeing that expert knowledge enhances, rather than skews, the learned decision policies.

4.8. Limitations Discussion

WinRegRL’s reliance on a single MDP model for all registry structures poses risks under severely sparse or noisy data. Sparse data, such as fragmented hives and partially deleted keys, may lead to incomplete state representations, causing the RL agent to misjudge transitions or rewards. Noisy data (e.g., irrelevant entries, timestomping) could distort reward signals, delaying convergence or yielding suboptimal policies. WinRegRL framework proposes an explicit fallback mechanism using rule-only inference for such scenarios. While RB-AI assists in policy generalisation, it operates alongside RL rather than as a contingency. Real-world deployment would require robustness enhancements, such as uncertainty-aware RL or dynamic RB-AI fallbacks, when state confidence thresholds are breached.

5. Conclusions and Future Works

This paper introduces a novel RL-based approach to enhance the current automation and data management in WR forensics and timeline analysis in volatile data investigation. We have shown that it is possible to streamline the analysis process, reducing both the time and effort required to identify relevant forensic artefacts as well as increase accuracy and performance, which will be translated into a better and more trusted output. Our proposed MDP model dynamically covers all registry hives, volatile data and key values based on their relevance to the investigation, and has proven effective in a variety of simulated attack scenarios. The model’s ability to adapt to different investigation contexts and learn from previous experiences represents a significant advancement in the field of cyber forensics. This research addresses gaps in existing methodologies through the introduction of a novel MDP model representing the Windows environment, enabling efficient automation of the investigation process. It also tackles the waste of knowledge in the practice as RL Optimal policies are captured and generalised, thus reducing investigation time by minimising MDP solving time. However, while the results are promising, several challenges remain. The effectiveness of the RL model heavily relies on the quality and modelling, which vary considerably in real-world scenarios and can be sparse or unbalanced, notably in new Windows OSs. Ultimately, the application of RL in WR analysis holds significant promise for improving the speed and accuracy of cyber incident investigations, potentially leading to more timely and effective responses to cyber threats. As the cyber threat landscape continues to evolve, the development of intelligent, automated tools such as the one proposed in this study will be crucial in staying ahead of adversaries and ensuring the integrity of digital investigations.

While RL offers robust solutions for cyber incident forensics analysis, challenges remain in implementing scalable models for WR analysis. Existing studies highlight the complexity of crafting accurate state-action representations and addressing reward sparsity. Future work should refine the model to handle diverse and evolving threat landscapes more robustly [

48]. This includes incorporating Large Language Models (LLMs) coupled with Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAGs) techniques in defining the MDP environments from dynamic cyber incident response data, enhancing the model’s generalisability, and ensuring its applicability across various versions of the Windows OS.

References

- StatCounter. 2024. Desktop Windows Version Market Share Worldwide for the period Oct 2023 - Oct 2024. Statcounter GlobalStats Report. https://gs.statcounter.com/os-version-market-share/windows/desktop/worldwide.

- Microsoft Inc. 2024. Microsoft Digital Defense Report 2024 The foundations and new frontiers of cybersecurity. https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/security-insider/intelligence-reports/microsoft-digital-defense-report-2024.

- Casino, F. , Dasaklis, T.K., Spathoulas, G.P., Anagnostopoulos, M., Ghosal, A., Borocz, I., Solanas, A., Conti, M. and Patsakis, C., 2022. Research trends, challenges, and emerging topics in digital forensics: A review of reviews. IEEE Access, 10, pp.25464-25493. [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.C. , 2022. Towards an efficient automation of network penetration testing using model-based reinforcement learning (Doctoral dissertation, City, University of London).https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/29885/.

- Yosifovich, P. , Solomon, D.A., Russinovich, M.E. and Ionescu, A., 2017. Windows Internals: System architecture, processes, threads, memory management, and more, Part 1. Microsoft Press.https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/3158930.

- Singh, A. , Venter, H.S. and Ikuesan, A.R., 2020. Windows Registry harnesser for incident response and digital forensic analysis. Australian Journal of Forensic Sciences, 52(3), pp.337-353. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H. and Kwon, H.Y., 2022. Large-scale digital forensic investigation for Windows Registry on Apache Spark. Plos one, 17(12), p.e0267411. [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.C. , Mulvihill, P., Ouazzane, K., Djemai, R. and Dunsin, D., 2023. D2WFP: A novel protocol for forensically identifying, extracting, and analysing deep and dark web browsing activities. Journal of Cybersecurity and Privacy, 3(4), pp.808-829. [CrossRef]

- Park, J. , 2018. TREDE and VMPOP: Cultivating multi-purpose datasets for digital forensics–A Windows Registry corpus as an example. Digital Investigation, 26, pp.3-18. [CrossRef]

- Dunsin, D. , Ghanem, M.C., Ouazzane, K., Vassilev, V., 2024. A comprehensive analysis of the role of artificial intelligence and ML in modern digital forensics and incident response. Forensic Science International. Digital Investigation 48, 301675. [CrossRef]

- Marková, Eva; Sokol, Pavol; Krišáková, Sophia Petra; Kováčová, Kristína. 2024. Dataset of Windows OS forensics artefacts, Mendeley Data, V1. [CrossRef]

- Farzaan, M.A. , Ghanem, M.C. and El-Hajjar, A., 2025. AAI-Powered System for an Efficient and Effective Cyber Incidents Detection and Response in Cloud Environments. IEEE Transactions on Machine Learning in Communications and Networking. Vol 3, Pages: 623-643. [CrossRef]

- Park, J. , Lyle, J.R. and Guttman, B., 2016. Introduction to CFTT and CFReDS projects at NIST. https://cfreds.nist. [CrossRef]

- Dunsin, D. , Ghanem, M.C., Ouazzane, K. and Vassilev, V., 2025. Reinforcement Learning for an Efficient and Effective Malware Investigation during Cyber Incident Response. High-Confidence Computing Journal. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Jun-Ha, and Hyuk-Yoon Kwon. 2020.Redundancy analysis and elimination on access patterns of the Windows applications based on I/O log data. IEEE Access 8 (2020): 40640-40655. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, Z. X. Wang, Z.Yang, G. Chen, Y. Liu. (2023). A Reinforcement Learning Method of Solving Markov Decision Processes: An Adaptive Exploration Model Based on Temporal Difference Error. Electronics. 12. 4176. [CrossRef]

- T. Zhang, C. Xu, J. Shen, X. Kuang and L. A. Grieco, How to Disturb Network Reconnaissance: A Moving Target Defense Approach Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning, in IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 18, pp. 5735-5748, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Bashar, S. Muhammad, N. Mohammad and M. Khan, “Modeling and Analysis of MDP-based Security Risk Assessment System for Smart Grids”, 2020 Fourth International Conference on Inventive Systems and Control (ICISC), Coimbatore, India, 2020, pp. 25-30. [CrossRef]

- X. Mo, S. Tan, W. Tang, B. Li and J. Huang, ReLOAD: Using Reinforcement Learning to Optimize Asymmetric Distortion for Additive Steganography. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, vol. 18, pp. 1524-1538, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Borkar, V. and Jain, R., 2014. Risk-constrained Markov decision processes. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 59(9), pp.2574-2579. [CrossRef]

- Dunsin, D. , Ghanem, M.C., Ouazzane, K. and Vassilev, V., 2024. A comprehensive analysis of the role of artificial intelligence and ML in modern digital forensics and incident response. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation, 48, p.301675. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. , Ju, P., Lei, S., Wang, Z., Wu, F. and Hou, Y., 2019. Markov decision process-based resilience enhancement for distribution systems: An approximate dynamic programming approach. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid, 11(3), pp.2498-2510. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Hyuk-Yoon (2022). Windows Registry Data Sets, Mendeley Data, V1. [CrossRef]

- MChadès, I. , Cros, M.J., Garcia, F. and Sabbadin, R., 2009. Markov decision processes (MDP) toolbox. http://www.inra.fr/mia/T/MDPtoolbox.

- Hore, S. , Shah, A. and Bastian, N.D., 2023. Deep VULMAN: A deep reinforcement learning-enabled cyber vulnerability management framework. Expert Systems with Applications, 221, p.119734. [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, R. , Jajodia, S., Shah, A. and Cam, H., 2016. Dynamic scheduling of cybersecurity analysts for minimising risk using reinforcement learning. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology (TIST), 8(1), pp.1-21. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. , Zhang, Z., Mao, B. and Yao, X., 2022. An overview of artificial intelligence ethics. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence, 4(4), pp.799-819. [CrossRef]

- Puterman, M.L. , 1990. Markov decision processes. Handbooks in operations research and management science, 2, pp.331-434. [CrossRef]

- Littman, M.L., Dean, T.L. and Kaelbling, L.P., 1995, August. On the complexity of solving Markov decision problems. In Proceedings of the Eleventh Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence (pp. 394-402). https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/2074158.2074203.

- Lapso, J.A. , Peterson, G.L. and Okolica, J.S., 2017. Whitelisting system state in Windows forensic memory visualizations. Digital Investigation, 20, pp. [CrossRef]

- Choi, J. , Park, J. and Lee, S., 2021. Forensic exploration on Windows File History. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation, 36, p.301134. [CrossRef]

- Berlin, K., Slater, D. and Saxe, J., 2015, October. Malicious behaviour detection using Windows audit logs. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Security (pp. 35-44). [CrossRef]

- Visoottiviseth, V. , Noonkhan, A., Phonpanit, R., Wanichayagosol, P. and Jitpukdebodin, S., 2023, September. AXREL: Automated Extracting Registry and Event Logs for Windows Forensics. In 2023 27th International Computer Science and Engineering Conference (ICSEC) (pp. 74-78). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, S. and Garg, G., 2021, July. Comparative analysis of acquisition methods in digital forensics. In 2021 Fourth International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Communication Technologies (CCICT) (pp. 129-134). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Studiawan, H. , Ahmad, T., Santoso, B.J. and Pratomo, B.A., 2022, October. Forensic timeline analysis of iOS devices. In 2022 International Conference on Engineering and Emerging Technologies (ICEET) (pp. 1-5). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Ionita, M.G. and Patriciu, V.V., 2015, May. Cyber incident response aided by neural networks and visual analytics. In 2015 20th International Conference on Control Systems and Computer Science (pp. 229-233). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Hoelz, B.W., Ralha, C.G., Geeverghese, R. and Junior, H.C., 2008. Madik: A collaborative multi-agent toolkit to computer forensics. OTM Confederated International Workshops and Posters, Monterrey, Mexico, November 9-14, 2008. Proceedings (pp. 20-21). [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M.C., Chen, T.M., Ferrag, M.A. and Kettouche, M.E., 2023. ESASCF: Expertise extraction, generalization and reply framework for optimized automation of network security compliance. IEEE Access.

- Horsman, G. and Lyle, J.R., 2021. Dataset construction challenges for digital forensics. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation, 38, p.301264. [CrossRef]

- Du, J. , Raza, S.H., Ahmad, M., Alam, I., Dar, S.H. and Habib, M.A., 2022. Digital Forensics as Advanced Ransomware Pre-Attack Detection Algorithm for Endpoint Data Protection. Security and Communication Networks, 2022(1), p.1424638. [CrossRef]

- Moore C., Detecting ransomware with honeypot techniques, Proceedings of the 2016 Cybersecurity and Cyberforensics Conference (CCC), August 2016, Amman, Jordan, IEEE, 77–81. [CrossRef]

- Du, J. , Raza, S.H., Ahmad, M., Alam, I., Dar, S.H. and Habib, M.A., 2022. Digital Forensics as Advanced Ransomware Pre-Attack Detection Algorithm for Endpoint Data Protection. Security and Communication Networks, 2022(1), p.1424638. [CrossRef]

- Lapso, J.A. , Peterson, G.L. and Okolica, J.S., 2017. Whitelisting system state in Windows forensic memory visualizations. Digital Investigation, 20, pp.2-15. [CrossRef]

- Karapoola, S., Singh, N., Rebeiro, C., 2022, October. RaDaR: A Real-Word Dataset for AI-powered Run-time Detection of Cyber-Attacks. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management (pp. 3222-3232). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M., Hu, Z. and Liu, P., 2014, November. Reinforcement learning algorithms for adaptive cyber defense against heartbleed. In Proceedings of the first ACM workshop on moving target defense (pp. 51-58).

- Zimmerman, E. 2019. I KAPE - Kroll artefact Parser and Extractor, Cyber Incident Division- Kroll LLC, https://ericzimmerman.github.io/KapeDocs/ (Accessed July 21, 2025).

- Hore, S. , Shah, A. and Bastian, N.D., 2023. Deep VULMAN: A deep reinforcement learning-enabled cyber vulnerability management framework. Expert Systems with Applications, 221, p.119734. [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y. , Duan, J., Xu, K., Cai, Y., Sun, Z. and Zhang, Y., 2024. A survey on large language model (llm) security and privacy: The good, the bad, and the ugly. High-Confidence Computing, p.100211. [CrossRef]

- Khalid, J. Rozner E. Felter W. Xu C. Rajamani K. Ferreira A. Akella A. Seshan S. Banerjee S(2018) Iron. Proceedings of the 15th USENIX Conference on Networked Systems Design and Implementation. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3307441.3307468.

- Guestrin, C. , Koller, D., Parr, R. and Venkataraman, S., 2003. Efficient solution algorithms for factored MDPs. Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 19, pp.399-468. [CrossRef]

- Littman, M.L., Dean, T.L. and Kaelbling, L.P., 1995, August. On the complexity of solving Markov decision problems. In Proceedings of the Eleventh conference on Uncertainty in artificial intelligence (pp. 394-402). https://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/2074158.2074203.

- Sanner, S. and Boutilier, C., 2009. Practical solution techniques for first-order MDPs. Artificial Intelligence, 173(5-6), pp.748-788. [CrossRef]

- Hahn, E.M. , Perez, M., Schewe, S., Somenzi, F., Trivedi, A. and Wojtczak, D., 2020, April. Good-for-MDPs automata for probabilistic analysis and reinforcement learning. In International Conference on Tools and Algorithms for the Construction and Analysis of Systems (pp. 306-323). Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Kimball, J., Navarro, D., Froio, H., Cash, A. and Hyde, J. 2022. Magnet Forenisics Inc. CTF 2022 dataset. https://cfreds.nist.gov/all/MagnetForensics/2022WindowsMagnetCTF.(Accessed 08/12/2024).

- Demir, M. 2024. IGU-CTF24: İstanbul Gelişim Üniversitesi Siber Güvenlik Uygulamaları Kulübü bünyesinde düzenlenen İGÜCTF 24’. https://cfreds.nist.gov/all/GCTF24Forensics. (Accessed 08/12/2024).

- Givan, R. , Dean, T. and Greig, M., 2003. Equivalence notions and model minimization in Markov decision processes. Artificial intelligence, 147(1-2), pp.163-223. [CrossRef]

- Patiballa, A.K. 2019. MemLabs Windows Forensics Dataset. https://cfreds.nist.gov/all/AbhiramKumarPatiballa/MemLabs. (Accessed 08/12/2024).

- Digital Corpora. 2009. NPS-Domexusers 2009 Windows XP Registry and RAM Dataset. https://corp.digitalcorpora.org/corpora/drives/nps-2009-domexusers.

- Loumachi, Fatma Yasmine, Mohamed Chahine Ghanem, and Mohamed Amine Ferrag. 2025. Advancing Cyber Incident Timeline Analysis Through Retrieval-Augmented Generation and Large Language Models. Computers 14, no. 2: 67. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).