Submitted:

10 February 2025

Posted:

11 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Paper Organization

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Forensics

2.2. Intention Recognition

2.3. Formal Modeling

2.4. Related Works

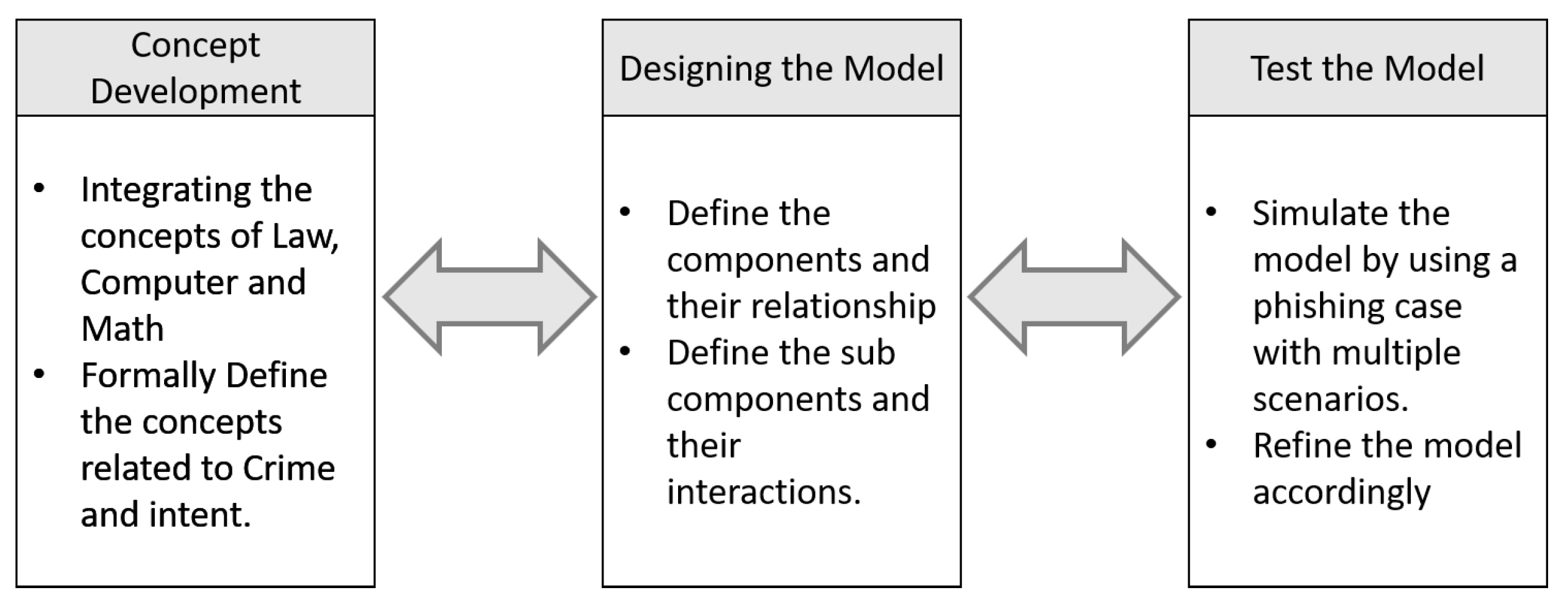

3. Method

3.1. Concept Development

3.2. Designing the Model

3.3. Testing the Model

4. Formal Definitions

4.1. Crime

- Let = Set of all crimes.

- Set = Set of all possible actions and inactions.

- Set = Set of all offenses.

- Set = Set of all punishments.

- Crime: The definition of crime can be expressed as (3)

4.2. Criminal intent

- E: Set of all evidence,

-

: A finite set specifying the four levels of intention or mens rea, where:

- −

- represents Purposely: Acting with the intention to achieve a specific result.

- −

- represents Knowingly: Acting with awareness that a result is practically certain to follow.

- −

- represents Recklessly: Acting with disregard for a substantial and unjustifiable risk.

- −

- represents Ignorantly: Acting without knowledge of the nature of the act or its consequences.

- S: Set of all suspects involved in the criminal activities.

- : Specifies that the evidence e shows that the suspect s has committed the crime c. This can be expressed as (4)

- : Specifies that the evidence e adequately satisfies the expected elements by the law l for the intent level i. This can be expressed as (5)

- : defines whether a suspect s has the criminal intent elements necessary for a crime c with intention i. For criminal intent to be established, the suspect must both commit the crime c and have the specific intention level i. Thus, criminal intent is true if and only if the evidence shows that the suspect has committed the crime and adequately satisfies the expected elements of the intention level i according to the law. This can be expressed as (6)

-

Alternatively:This definition (7) is equivalent to the above definition, however, it gives us the flexibility to reuse it in defining each type of intent based on the relation to the required intent elements by the law.

4.3. Intent Types

- Z: Set of all Outcomes.

- Purposeful Intent:

- 2

- Knowing Intent:

- 3

- Reckless Intent

- 4

- Ignorant Intent

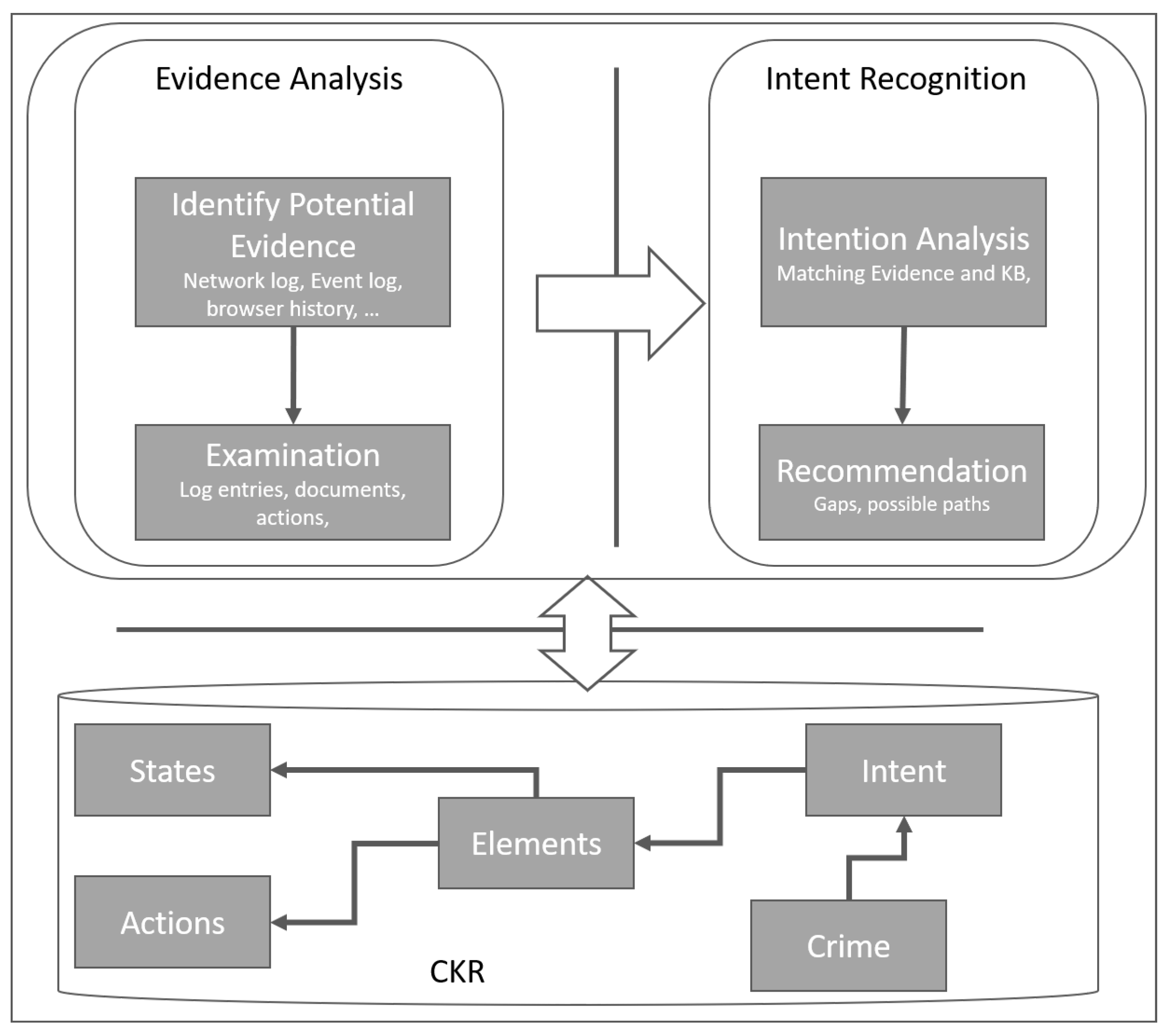

5. The IR based Model

5.1. Evidence Analysis

5.1.1. Identification of Potential Evidence

- Related(e,c,k): specifies that the evidence e is related to the crime c according to the crime knowledge repository k. This can be expressed as (17)

- PotentialEvidence(p,c): denotes the set of potential evidence p, that is the subset of the overall evidence, which is filted by applying the crime knowledge base related to the crime c. This can be expressed as (18)

5.1.2. Examiniation of Evidence

- RelatedEntry(q, p, c, k): specifies that the entry q is recorded in the potential evidence p and it is related to crime c according to the knowledge base k. This can be expressed by (19)

- Relevant(r): specifies that the evidence r is a relevant entry in the potential evidence for the crime c according to the crime knowledge repository k. This can be expressed by (20)

5.2. Intent Recognition

5.2.1. Intention Analysis

- Match(r, k, c, i): specifies that each elements of the crime c at the intention level of i which are found in the Crime Knowledge Base k has a match in the relevant evidence r. This can be expressed by (21)

- Culpable(s,c,i,r,k): specifies that the Suspect s is culpable of the Crime c at an intention level of i, given the match of the Relevant evidence r and the CKB k. This can be expressed by (22)

5.2.2. Recommendation

- NeededEvidence(d): specifies that from the elements of the crime c at the intention level of i which are found in the Crime Knowledge Base k, there are some elements d which are missing in the relevant evidence r. This can be expressed by (23)

- RelatedToOtherCrime(r): specifies that the Relevant evidence r is also related to other Crime c’ according to the CKB k. This can be expressed by (24)

5.3. Crime Knowledge Repository

6. Scenario

-

Purposely

- Context: An attacker (S1) designs a phishing email with a malicious link, aiming specifically at the company. The email is crafted to closely resemble legitimate communications from the company’s trusted partners.

- Specific Situation: The attacker sends the email to the finance officer, intending for it to be clicked and to initiate a DDoS attack on the company.

- Action Taken: The attacker’s goal is clear: to cause disruption or harm to the company’s operations by tricking the finance officer into clicking the malicious link.

- Categorization: The attacker’s intent is categorized as "purposely" because the malicious email was sent with the specific objective of causing harm.

For this level of culpability, the following crime elements are considered minimal requirements.- Connection to the Suspect: The court needs to establish that the suspect was indeed involved in the phishing attack. This can be done by showing evidence such as Network logs, email metadata, or records and transactions linking the suspect to the phishing activity [69,70]. (The necessary evidence are: Network logs, Email logs, Browser History)

- Plan to Deceive: The court would need evidence showing that the suspect intentionally crafted a fraudulent communication to manipulate the victim into disclosing personal or financial information. This can be shown from the evidence by disclosing the phishing tools and techniques the attacker employed [68,69]. (The necessary evidence are: Network logs, Event logs, System Logs, Browser History, System files)

- Transmission of Fraudulent Communications: The court would need proof that the suspect was responsible for sending the phishing communication—whether by email, phone, or other means. This can be shown through evidence such as email headers, phone logs, or IP address tracing [68,69]. (The necessary evidence are: Network log, email log, email content, phone log )

- Loss (or Victim’s Response): To prove that a phishing attack took place, it is generally necessary to show that the victim was deceived and suffered some form of harm, such as revealing sensitive information or losing money. Evidence such as victim testimony, transaction records, or documentation of identity theft can be used in establishing that the phishing attempt had a tangible impact [68,69]. (The necessary evidence are: Bank Transaction, Account History, reputation assessment, customer statistics)

The model will run the case as follows:-

Identification of Potential Evidence:

- −

- Input: The overall evidence collected in relation to the Suspect, S1.

- −

- Process: The sub component will filter the overall evidence by considering the evidence list for the specific crime, Phishing via email, from the Crime Knowledge Base.

- −

- Output: List of potential evidence extracted from the whole evidence. (Network log, Event log, Email log, Browser History, system files, Email Content, Phone log, Bank Transaction, Account History, Reputation Assessment, Customer statistics)

-

Examination of Evidence:

- −

- Input: Potential evidence identified which is the output of previous (Identification of Potential Evidence) sub component.

- −

- Process: The sub component go through each potential evidence and identify the relevant entries in relation to the Suspect S1 and the phishing crime. Besides this sub component convert the entries to a common format used by the CKB using action and state template.

- −

- Output: List of Relevant entries in the form of actions and state documentation.

-

Intention Analysis:

- −

- Input: List of Relevant entries in action and state format which is the output of the previous (Examination of Evidence) sub component.

- −

- Process: The sub component analyses the relevant entries with the expected evidence for the crime as documented in the CKB.

- −

- Output: The whole analysis as well as the entries and the expected evidence.

-

Recommendation:

- −

- Input: The analysis, the entries and the expected evidence which are the output of the previous (Intention Analysis) sub component.

- −

- Process: The sub component analyzes: considering the available evidence what should be the conviction level, what evidence are needed to support or clarify the case, what other criminal activities are related to the evidence.

- −

- Output: List of recommendations.

-

Ignorance

- Context: The company receives a phishing email that closely mimics previous legitimate communications and creates a sense of urgency.

- Specific Situation: The finance officer, recognizing the email as urgent and similar to past legitimate messages, forwards it to the cyber security officer for validation. After not receiving a prompt response and due to the urgency conveyed in the email, the finance officer decides to click the link.

- Action Taken: The finance officer clicks the link, assuming the email is legitimate, and is unaware of its malicious nature.

- Categorization: The finance officer’s action is categorized as "ignorance" because they acted under the mistaken belief that the email was legitimate, lacking awareness of its malicious intent.

-

Recklessly

- Context: A phishing email, designed to appear legitimate, is sent to the company and is forwarded by the finance officer to the cyber security officer for validation.

- Specific Situation: The cyber security officer, overwhelmed by other urgent tasks, quickly responds to the finance officer’s inquiry without thoroughly checking the link, indicating it is safe.

- Action Taken: The cyber security officer’s hasty response, without proper verification of the link, demonstrates a disregard for the potential risks involved.

- Categorization: The cyber security officer’s action is categorized as "recklessly" because they failed to exercise due diligence and responded in a manner that ignored the potential risks of the link.

-

Knowingly

- Context: A phishing email is received by the company, which closely resembles legitimate communications and contains a malicious link.

- Specific Situation: The finance officer forwards the email to the cyber security officer, requesting validation and indicating urgency. The cyber security officer, recognizing the link as malicious and knowing it could potentially lead to a DDoS attack, chooses not to respond to the finance officer’s inquiry.

- Action Taken: The cyber security officer makes a deliberate decision to ignore the email, based on the belief that the company’s security measures will mitigate any impact from the attack.

- Categorization: The cyber security officer’s action is categorized as **knowingly** because they were aware of the threat and chose not to act, assuming the company’s defenses would handle the risk.

-

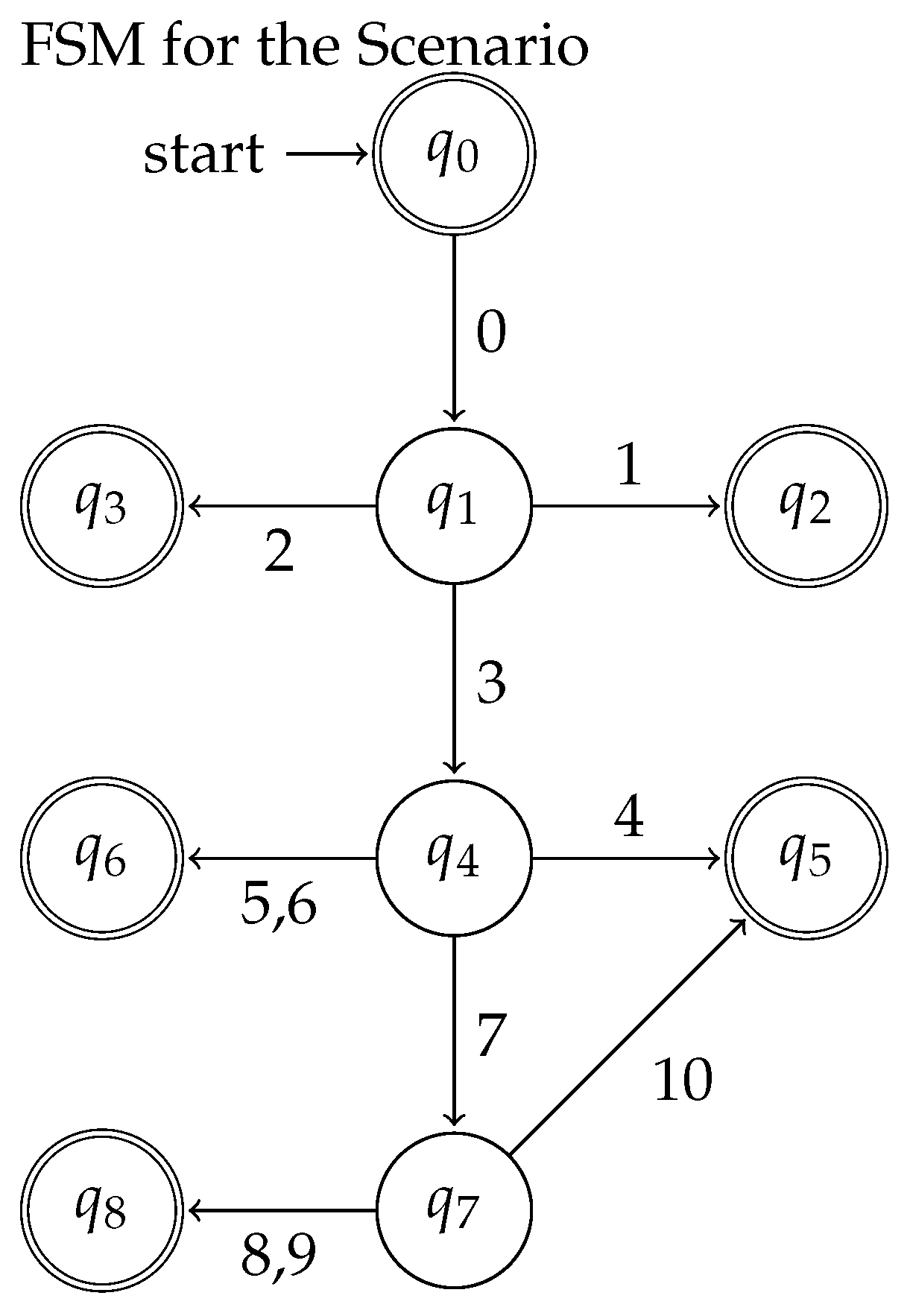

States

- : Attacker Sends Malicious Email and is guilty of "Purposefully" intent.

- : Email Received by Finance Officer

- : Finance officer is free from crime, (no criminal intent).

- : Finance officer is guilty of "ignorantly" intent

- : Finance Officer forwards the email to Cyber Security Officer for verification

- : Cyber Security Officer is free from crime (no criminal intent).

- : Cyber Security Officer is guilty of "recklessly" intent

- : Email investigated by Cyber Security Officer

- : Cyber Security Officer is guilty of "knowingly" intent

-

Transitions

- 0: Attacker sends the email.

- 1: Finance officer ignores the email.

- 2: Finance officer clicks the malicious link inside the email, assuming it’s legitimate.

- 3: Finance officer forwards the email to the Cyber Security Officer for validation.

- 4: Cyber Security Officer forbids the Finance Officer from clicking the malicious link.

- 5: Cyber Security Officer allows the Finance Officer to click the malicious link.

- 6: Cyber Security Officer ignores the email.

- 7: Cyber Security Officer analyzes the malicious link inside the email.

- 8: Cyber Security Officer allows the Finance Officer to click the malicious link, assuming the security measures are already in place to handle it.

- 9: Cyber Security Officer ignores the email, which is inaction despite knowing the threat.

- 10: Cyber Security Officer forbids the Finance Officer from clicking the malicious link.

7. Discussion

8. Conclusion and Future Work

References

- Kuzior, A.; Tiutiunyk, I.; Zielińska, A.; Kelemen, R. Cybersecurity and cybercrime: Current trends and threats. Journal of International Studies (2071-8330) 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Manocha, T.; Garg, S.; Sharma, S.; Garg, A.; Sharma, R. Growth of Cyber-crimes in Society 4. In 0. In Proceedings of the 2023 3rd International Conference on Innovative Practices in Technology and Management (ICIPTM); 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, D.S. Cybercrime: The transformation of crime in the information age; John Wiley & Sons, 2024.

- Lusthaus, J. Reconsidering Crime and Technology: What Is This Thing We Call Cybercrime? Annual Review of Law and Social Science 2024, 20, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biedron, S.R. Cybercrime in the Digital Age. Master’s thesis, University of Oxford, 2024.

- Fakhouri, H.N.; AlSharaiah, M.A.; Al hwaitat, A.k.; Alkalaileh, M.; Dweikat, F.F. Overview of Challenges Faced by Digital Forensic. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Cyber Resilience (ICCR); 2024; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alenezi, A.M. Digital forensics in the age of smart environments: A survey of recent advancements and challenges. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.09682, arXiv:2305.09682 2023.

- Dunsin, D.; Ghanem, M.C.; Ouazzane, K.; Vassilev, V. A comprehensive analysis of the role of artificial intelligence and machine learning in modern digital forensics and incident response. Forensic Science International: Digital Investigation 2024, 48, 301675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelet, G.; Breitinger, F.; Horsman, G. Automation for digital forensics: Towards a definition for the community. Forensic Science International 2023, 349, 111769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, D.; Choo, K.K.R. Impacts of increasing volume of digital forensic data: A survey and future research challenges. Digital Investigation 2014, 11, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Ahlami, N.; Zaman, K. Attack Intention Recognition : A Review 2017. 19. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Nguyen, N.A. Attack plan recognition using hidden Markov and probabilistic inference. Computers and Security 2020, 97, 101974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navalgund, U.V. ; K. In , P. Crime Intention Detection System Using Deep Learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Circuits and Systems in Digital Enterprise Technology (ICCSDET), dec 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abarna, S.; Sheeba, J.I.; Jayasrilakshmi, S.; Devaneyan, S.P. Identification of cyber harassment and intention of target users on social media platforms. Engineering Applications of Artificial Intelligence 2022, 115, 105283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute, A.L. Model penal code : official draft and explanatory notes : complete text of model penal code as adopted at the 1962 annual meeting of the American Law Institute at Washington, D.C., May 24, 1962; Philadelphia, Pa.: The Institute, 1985, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, O.D.; Montague, R.; Yaffe, G. Detecting mens rea in the brain. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 2020, 169, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Antill, G. Fitting the Model Penal Code into a ReasonsResponsiveness Picture of Culpability. Yale Law Journal 2022, 131, 1346–1384. [Google Scholar]

- National, G.; Pillars, H. Digital Forensics, Andre Arnes; 2018; p. 373.

- Kent, K.; Chevalier, S.; Grance, T.; Dang, H. Guide to Integrating Forensic Techniques into Incident Response. The National Institute of Standards and Technology 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, N.A. Introduction: Understanding Digital Forensics; 2019; pp. 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Holt, T.; Bossler, A.; Seigfried-Spellar, K. Cybercrime and Digital Forensics; Taylor and Francis, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Tripathi, A.K.; Kapil, G.; Singh, V.; Khan, M.W.; Agrawal, A.; Kumar, R.; Khan, R.A. Current Challenges of Digital Forensics in Cyber Security 2020. pp. 31–46. [CrossRef]

- Montasari, R.; Hill, R.; Parkinson, S.; Peltola, P.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Daneshkhah, A. Digital Forensics: Challenges and Opportunities for Future Studies. International Journal of Organizational and Collective Intelligence 2020, 10, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karie, N.M.; Venter, H.S. Taxonomy of Challenges for Digital Forensics. Journal of Forensic Sciences 2015, 60, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sukthankar, G.; Geib, C.; Bui, H.H.; Pynadath, D.; Goldman, R.P. Plan, activity, and intent recognition: Theory and practice; Newnes, 2014.

- Van-Horenbeke, F.A.; Peer, A. Activity, Plan, and Goal Recognition: A Review. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2021, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.A.; Pereira, L.M. State-of-the-art of intention recognition and its use in decision making. AI Communications 2013, 26, 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarno, D.; Kragic, D. Motion intention recognition in robot assisted applications. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2008, 56, 692–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Guo, Z.; Xia, S.; Zhu, L. Intention recognition of aerial target based on deep learning. Evolutionary Intelligence 2024, 17, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassa, Y.W.; James, J.I.; Belay, E.G. Cybercrime Intention Recognition: A Systematic Literature Review. Information 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, A.; Doshi, P.; Setayeshfar, O. Cyber Attack Intent Recognition and Active Deception Using Factored Interactive POMDPs. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and MultiAgent Systems, Richland, SC, 2021.

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, C.; Sun, P.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J. Network Attack Intention Recognition Based on Signaling Game Model and Netlogo Simulation. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Digital Society and Intelligent Systems (DSInS); 2021; pp. 162–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokolo, B.G.; Onyehanere, P.; Ogegbene-Ise, E.; Olufemi, I.; Tettey, J.N.A. Leveraging Machine Learning for Crime Intent Detection in Social Media Posts. In Proceedings of the AI-generated Content; Zhao, F.; Miao, D., Eds., Singapore; 2023; pp. 224–236. [Google Scholar]

- Bhugul, A.M.; Gulhane, V.S. Novel Deep Neural Network for Suspicious Activity Detection and Classification. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Students’ Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Science (SCEECS); 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsinganos, N.; Fouliras, P. Leveraging Dialogue State Tracking for Zero-Shot Chat-Based Social Engineering Attack Recognition 2023.

- Hamroun, M.; Gouider, M.S. A survey on intention analysis: successful approaches and open challenges. Journal of Intelligent Information Systems 2020, 55, 423–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J.P. Gerard O’Regan: Concise Guide to FormalMethods: Theory, Fundamentals and IndustryApplications. Formal Aspects of Computing 2020, 32, 147–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weyers, B.; Bowen, J.; Dix, A.; Editors, P.P. Human–Computer Interaction Series The Handbook of Formal Methods in Human-Computer Interaction; 2017.

- ter Beek, M.H.; Chapman, R.; Cleaveland, R.; Garavel, H.; Gu, R.; ter Horst, I.; Keiren, J.J.A.; Lecomte, T.; Leuschel, M.; Rozier, K.Y.; et al. Formal Methods in Industry. Form. Asp. Comput. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, K.; Legay, A.; Nolte, G.; Schlüter, M.; Stoelinga, M.; Steffen, B. Formal Methods Meet Machine Learning (F3ML). In Proceedings of the Leveraging Applications of Formal Methods, Verification and Validation. Adaptation and Learning; Margaria, T.; Steffen, B., Eds., Cham; 2022; pp. 393–405. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, E.; Schubert, T.; Kumar, M.V.A.K. Formal verification: an essential toolkit for modern VLSI design; Elsevier, 2023.

- Woodcock, J.; Larsen, P.G.; Bicarregui, J.; Fitzgerald, J. Formal methods: Practice and experience. ACM Comput. Surv. 2009, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, M.; Malik, A.; Dave, M. Formal Methods: Benefits, Challenges and Future Direction. Journal of Global Research in Computer Science 2013, 4, 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Knight, J.C. Challenges in the utilization of formal methods. In Proceedings of the Formal Techniques in Real-Time and Fault-Tolerant Systems; Ravn, A.P.; Rischel, H., Eds., Berlin, Heidelberg; 1998; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.A.; Mohammed, M.F. SAIRF: A similarity approach for attack intention recognition using fuzzy min-max neural network. Journal of Computational Science 2018, 25, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Shin, D.; Shin, D.; Kim, Y.H. Attack Detection Application with Attack Tree for Mobile System using Log Analysis. Mobile Networks and Applications 2019, 24, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, B. Cyber Situation Comprehension for IoT Systems based on APT Alerts and Logs Correlation. Sensors 2019, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, R.; Zhang, X.; Ji, S.; Luo, X.; Wang, T. AdvMind: Inferring Adversary Intent of Black-Box Attacks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 26th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery &. [CrossRef]

- Mirsky, R.; Shalom, Y.; Majadly, A.; Gal, K.; Puzis, R.; Felner, A. New Goal Recognition Algorithms Using Attack Graphs. In Proceedings of the Cyber Security Cryptography and Machine Learning; Dolev, S.; Hendler, D.; Lodha, S.; Yung, M., Eds., Cham; 2019; pp. 260–278. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Liu, Y.; Li, S.; Gao, X. Attack intent analysis method based on attack path graph. ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Yan, Q.; Li, B.; Shao, M.; Peng, H.; Sun, L. Automatically predicting cyber attack preference with attributed heterogeneous attention networks and transductive learning. Computers and Security 2021, 102, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Dai, Y.; Zhan, M.; Wang, W. ActDetector: A Sequence-based Framework for Network Attack Activity Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC); 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, T.; Tang, C. Detection of Malicious Activities Using Machine Learning in Physical Environments. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Computational Science and Computational Intelligence (CSCI), Los Alamitos, CA, USA, dec 2022; pp. 1047–1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guang, K.; Guangming, T.; Xia, D.; Shuo, W.; Kun, W. A network security situation assessment method based on attack intention perception. In Proceedings of the 2016 2nd IEEE International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), oct 2016; pp. 1138–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Mascorro, G.A.; Abreu-Pederzini, J.R.; Ortiz-Bayliss, J.C.; Garcia-Collantes, A.; Terashima-Marín, H. Criminal Intention Detection at Early Stages of Shoplifting Cases by Using 3D Convolutional Neural Networks. Computation 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mendonça, R.R.; de Brito, D.F.; de Franco Rosa, F.; dos Reis, J.C.; Bonacin, R. A framework for detecting intentions of criminal acts in social media: A case study on twitter. Information (Switzerland) 2020, 11, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, R.; Purohit, H.; Stabile, B.; Grant, A. Distributional Semantics Approach to Detect Intent in Twitter Conversations on Sexual Assaults. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence (WI); 2018; pp. 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsinganos, N.; Fouliras, P.; Mavridis, I. Applying BERT for Early-Stage Recognition of Persistence in Chat-Based Social Engineering Attacks. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, A. What is Crime Mapping 2013. 1.

- Bell, S. crime, A Dictionary of Forensic Science, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Gooch, G.; Williams, M. crime, A Dictionary of Law Enforcement, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Dictionaries, O. crime, The Oxford Essential Dictionary of the U.S. Military, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Government of Ethiopia. Computer Crime Proclamation No.958/2016. <italic>Negarit Gazeta</italic> <b>2016</b>, p. Government of Ethiopia. Computer Crime Proclamation No.958/2016. Negarit Gazeta, 9104. [Google Scholar]

- Gooch, G.; Williams, M. Intention, A Dictionary of Law Enforcement, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Law, J. intention, A Dictionary of Law (10 ed.), 2022. [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M. Criminal Intention and Motive in Criminal Law: A comparative approach. Researchgate 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coffey, G. Codifying the Meaning of ‘Intention’ in the Criminal Law. Journal of Criminal Law 2009, 73, 394–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastenis, J.; Ramanauskaitė, S.; Janulevičius, J.; Čenys, A.; Slotkienė, A.; Pakrijauskas, K. E-mail-Based Phishing Attack Taxonomy. Applied Sciences 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalil, Z.; Hewage, C.; Nawaf, L.; Khan, I. Phishing Attacks : A Recent Comprehensive Study and a New Anatomy 2021. 3. [CrossRef]

- Leukfeldt, E.R. Cybercrime and social ties. Trends in Organized Crime 2014, 17, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowledge and Information Edited by.

- Chawla, C.; Chatterjee, S.; Gadadinni, S.S.; Verma, P.; Banerjee, S. Agentic AI: The building blocks of sophisticated AI business applications. Journal of AI, Robotics & Workplace Automation 2024, 3, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- White, J. Building Living Software Systems with Generative and Agentic AI. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.01768, arXiv:2408.01768 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).