Introduction

The United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (1992) defines biological diversity as “the variety of living organisms of any origin, including terrestrial and marine ecosystems, other aquatic systems and the ecological complexes of which they are a part, addressing diversity within and between species as well as between ecosystems”. Biodiversity is of great importance for ecosystems such as protecting soils against erosion, increasing soil fertility, providing clean water to streams/rivers, contributing to the healthy continuation of nutrient cycling, pollinating plants, acting as a buffer against diseases. These characteristics of biodiversity are called “ecosystem functions” or “ecosystem services”. However, many factors threaten biodiversity, such as changes in land cover and land use, pollution, invasion of exotic species and climate change. Among these, it would not be wrong to say that the anthropogenic climate change experienced today is one of the most important threats to biodiversity. Indeed, both the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and many studies clearly reveal the impacts of current and future climate change on biodiversity (IPCC AR6, Laušević et al. 2008; Feehan et al. 2009; Gottfried et al. 2012; Pauli et al. 2012). For example, according to the IPCC report, "climate change has caused increasing and irreversible losses and significant damage to terrestrial, freshwater, cryospheric, coastal and open ocean ecosystems". However, building biodiversity resilience to climate change and supporting ecosystem integrity can contribute to disaster risk reduction, climate change adaptation and mitigation, as well as benefits to people, including livelihoods, human health and well-being, and the provision of food, fibre and water (Türkeş, 2022). Therefore, the conservation and sustainability of biodiversity is becoming more and more important today.

Plant species, which are the cornerstone of terrestrial ecosystems, can reproduce and grow successfully only under certain climatic conditions. When these conditions change, these species will either adapt or be forced to migrate. However, migration is often difficult for some species, especially those living at high altitudes and in northern regions. When plant species cannot adapt to changing conditions or cannot relocate, they will face the danger of extinction. A reduction in the richness of plant species can limit overall biodiversity and lead to reduced ecosystem stability. It may become a threat to some ecosystem products and services such as raw materials, pollination, gas regulation, especially medicine and food. In addition, changes in plant species distribution and vegetation composition may have some consequences on the climate system (Demir, 2009). As a result, plant species diversity is of great importance for the healthy continuation of ecosystem functions or ecosystem services. However, studies show that plant species composition has changed or species have disappeared in many regions of the world with the human induced climate changes experienced today, especially anthropogenic effects. For example, Bakkenes et al. (2002) reported that species are becoming extinct at a rate 100-1000 times greater than what is considered normal, while Parmesan and Yohe (2003) found that a large number of plant species in Europe have moved northwards in the last few decades and that this is closely related to temperature increases. Studies also show that plants and vegetation, especially in high mountainous areas such as the Alps, are more sensitive to climate change (Beniston 1994; Guisan et al. 1995; Richard et al. 2008; Kienast et al. 1998).

According to IPCC reports, Turkey, like other Mediterranean countries, is one of the countries that will be most affected by climate change. As a matter of fact, many studies on climate change in Turkey also support this. For example, studies show that the number of tropical and summer days in Turkey has a statistically significant increasing trend, night temperatures have been rising rapidly since the mid-1980s, and the minimum temperature regime or statistical distribution has changed remarkably (Türkeş 2012; Erlat and Türkeş, 2017; Erlat and Türkeş, 2013; Şen et al., 2017). Our research is based on the assumption that the impacts of climate change on plant biodiversity and thus ecosystem services in Southwest Anatolia will be severe; in fact, these impacts, such as increasing temperatures, extreme pressure on water resources, increased frequency of severe weather conditions and floods, increased coastal erosion and more forest fires, etc., have started to be seen in our research area as in many parts of the world.

Material and Method

In order to reveal the changes and trends in temperature and precipitation in the research area, daily average, daily maximum and daily minimum temperatures and daily total precipitation data of 10 selected meteorological stations were obtained from the General Directorate of Meteorology (

Figure 1).

Non-parametric Mann-Kendall rank correlation coefficient was used to determine the long-term changes and trends in temperature and precipitation and to test their statistical significance. The Mann-Kendall test sample value gives the direction and statistical magnitude of a long-term trend in a sequence. The calculation of the M-K rank correlation coefficient tau (τ) is based on the original observation sequence of xi elements analyzed, replaced by a series of chi sequences of rank numbers obtained by arranging them in descending order, and the rank of each term is calculated. Secondly, the P statistic is calculated. The value of the first term in the ki sequence is compared with the values of all terms in the sequence, from the value of the second term to the Nth term. The number of terms exceeding ki is found and denoted as n1. The same operation is performed between the value of the second term and the subsequent terms, and the number of subsequent terms exceeding k2 is denoted as n2. This process is performed for each term in the sequence up to kn-1. The sum of ni gives the P statistic shown in equation (1).

The M-K test sample value (τ) is calculated by the following equation (2) using N and P:

The significance test (τ)t of tau (τ) is calculated by equation (3).

The null hypothesis "There is no trend in the mean of the observation series" is rejected for large values of (τ) and if the calculated value of (τ) is significant at the 0.05 or 0.01 level, the existence of a trend in the increasing direction is accepted if (τ) > 0 and in the decreasing direction if (τ) < 0 (Erlat & Yavaşlı, 2011).

Study Area

The study area is located in southwestern Turkey within the Mediterranean phytogeographic region and within squares C1 and C2 according to the Flora of Turkey quadratic system determined by Davis (1971) (

Figure 1). Squares C1 and C2 geographically cover the Aydın Mountains, the Menteşe region and part of the western Taurus Mountains. In this respect, it is observed that the area is highly rugged and the elevation, slope and aspect conditions change frequently in very short distances (

Figure 2). These topographical features have enabled the formation of local climatic zones in the research area, which is generally located in the Mediterranean macro-climatic zone, leading to an increase in biodiversity and the number of endemic species. The topographic features of the area and the associated local climatic zones provided a refuge for migratory plants during the last glacial period (Würm) (Médail and Diadema, 2009). As a matter of fact, approximately 3444 plant species have been identified in the area, of which approximately 772 are endemic and the rate of endemism is over 25% (Kutluk and Aytuğ, 2004).

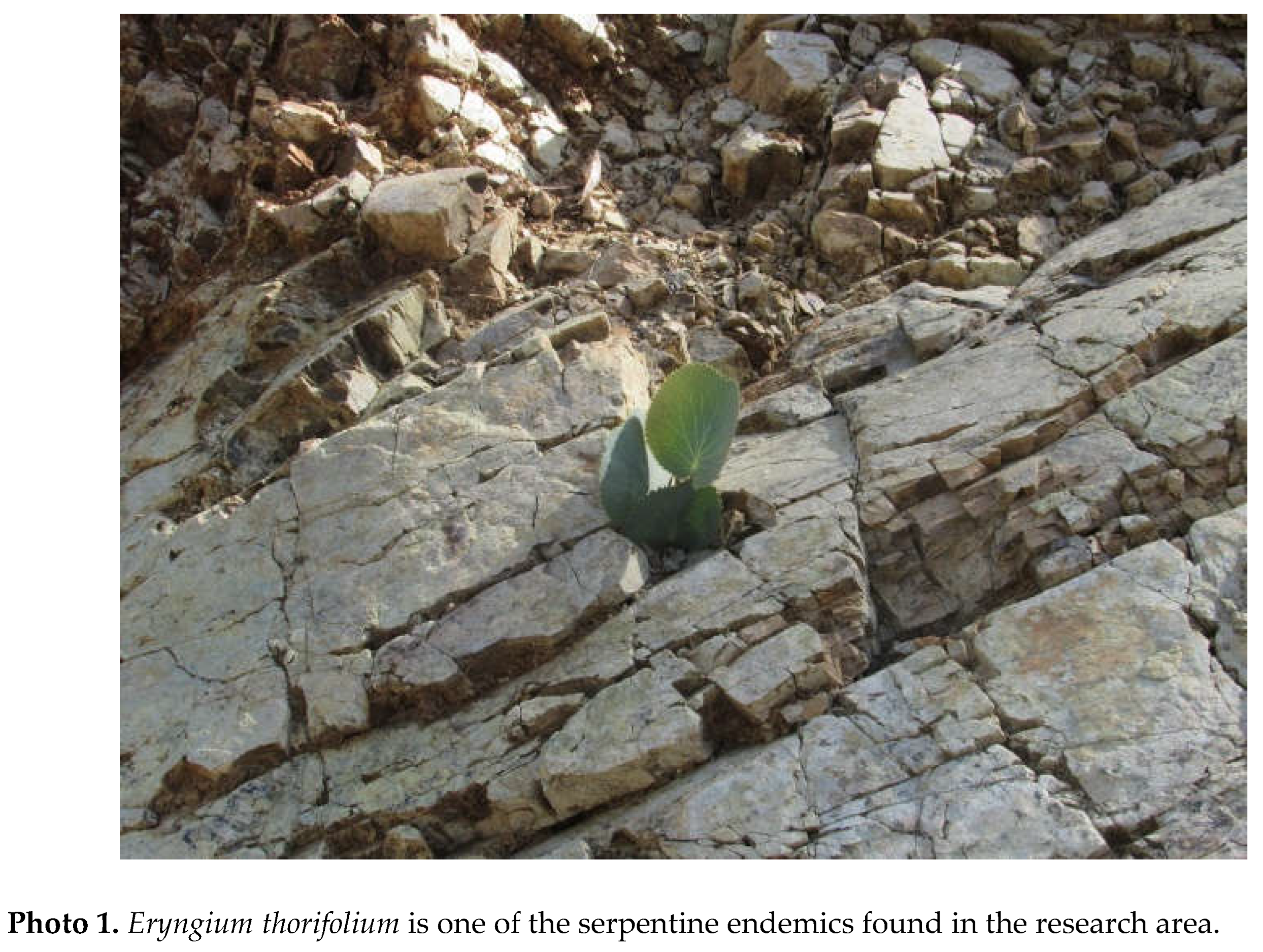

In addition to the diversity created by topographic conditions, the geological structure of the research area is also an effective factor in the high rate of endemism. In this area, serpentines in the ophiolite series among the ultramafic rocks occupy a large area and the areas where these types of rocks are found and the areas with high endemism rates mostly overlap. This situation is explained by geological isolation and Mason (1946) uses the name "edaphic endemic" for these species which are found on ultramafic rocks and have a narrow distribution (Photo 1).

The research area is located in the "Mediterranean Basin biological hotspot area" with its plant biodiversity. As is known, hotspots are defined as areas with at least 1500 plant species that are found nowhere else and have lost more than 70 per cent of their original habitat (Mittermeier et al., 2004). The Mediterranean Basin is the third richest hotspot in the world in terms of plant biodiversity and one of the most important areas in the world for endemic plants. In addition, there are 15 important plant areas in our research area (Table 3). Important plant areas (IPAs) are defined as "natural or semi-natural areas that hosting very rich populations of rare, endangered and/or endemic plant species and/or contain botanically exceptionally rich and/or highly valuable vegetation" (Özhatay et al. 2008).

Results and Conclusion

Changes and Trends in Temperature and Precipitation

When the time series plots of the mean, maximum and minimum temperatures of the 10 meteorological stations examined in the research area are analyzed, it is seen that the temperatures are in an increasing trend in all stations (

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). According to Mann-Kendall test, this increasing trend is significant at all stations with a probability of 99.9% (α=0.001) (

Table 1). When we look at the change of annual average temperatures according to seasons, it is seen that there is a statistically significant increasing trend in all seasons. Especially the increase in autumn and spring temperatures has an important place for plant development because it causes a result such as prolongation of the vegetation period. For example, an extended vegetation period may benefit farmers adapting to new conditions, but may be harmful to natural vegetation or flora, as discussed in more detail below (Laušević et al. 2008). In addition, it was observed that the average temperatures of the last twenty years in the research area were 0.7 °C higher than the long-term average temperatures.

It is observed that there is a decreasing trend in total annual precipitation at all stations, but this trend is not statistically significant. Seasonal precipitation was analyzed in order to reveal the change in the distribution of precipitation during the year and the tendency of this change. Accordingly, it is observed that there is a decrease in winter precipitation in all stations analyzed except Kaş. This decreasing trend is statistically significant with a probability of 90% (p<0.1) in Muğla and 95% (p<0.05) in Tefenni, while the decreasing trend is not statistically significant in other stations. On the other hand, there is an increasing trend in summer precipitation in the study area except for one station (Bodrum). This increasing trend is statistically significant with a probability of 90% (p<0.1) in Kaş, 95% (p<0.05) in Acıpayam and Muğla, 99% (p<0.01) in Tefenni, while the increasing trend in other stations is not statistically significant (

Table 2,

Figure 6).

Effects of Climate Change on Biodiversity

Phenological Changes

Phenology is a science that measures the timing of life cycle events for plants, animals and microorganisms and determines how the environment influences the timing of these events. When flowering plants are observed, these life cycle events or "phenological stages" include, among other steps, "bud bursting", "first flower bloom", "last flower bloom", "first fruit maturity" or "leaf drop" (Şimşek et al. 2014). As is well known, some phenological responses are mainly triggered by temperature, while others are more sensitive to day length. Such changes are linked to the growing season and affect ecosystem functioning and productivity (Menzel et al., 2006). Common changes in the timing of spring activities in relation to plants include earlier shoot and leaf appearance and flowering. Changes in flowering have effects on the timing and intensity of the pollen season, which shows a progressive trend with many species starting to flower earlier (Lausevic et al., 2008). Although there is no direct study showing phenological changes related to the research area, in recent years, there are studies aiming to reveal the relationships between various agricultural plants, their phenological periods and climate changes in Turkey. For example, the study, which included our research area and examined the effects of climate change on the phenological periods of fruit trees and field crops in Turkey, showed that with increasing temperatures, there was a negative relationship between the phenological periods of apple, cherry and wheat and the average temperatures of February-May, when plant growth is high. This means that plants shift their phenological period earlier in response to increasing temperatures. The trend calculated for the harvest dates of apple, cherry and wheat in the study is -25, -22, -40 days/100 years, respectively (Türkoğlu et al., 2014). In the study examining the changes in the duration of the vegetation period and the start and end dates of the vegetation period in the Aegean region, it was found that the relationship between the average temperatures of February-March-April and the changes in vegetation duration and vegetation period starts was very high (.000) at 0.001 level. According to the results of the same study, it is seen that the vegetation period in the Aegean region in the last thirty years (1990-2019) has been extended by 5 days according to the threshold value of 5 °C and 4 days according to the threshold value of 8 °C compared to the long-term averages (Sütgibi, 2023).

Change of Distribution Areas

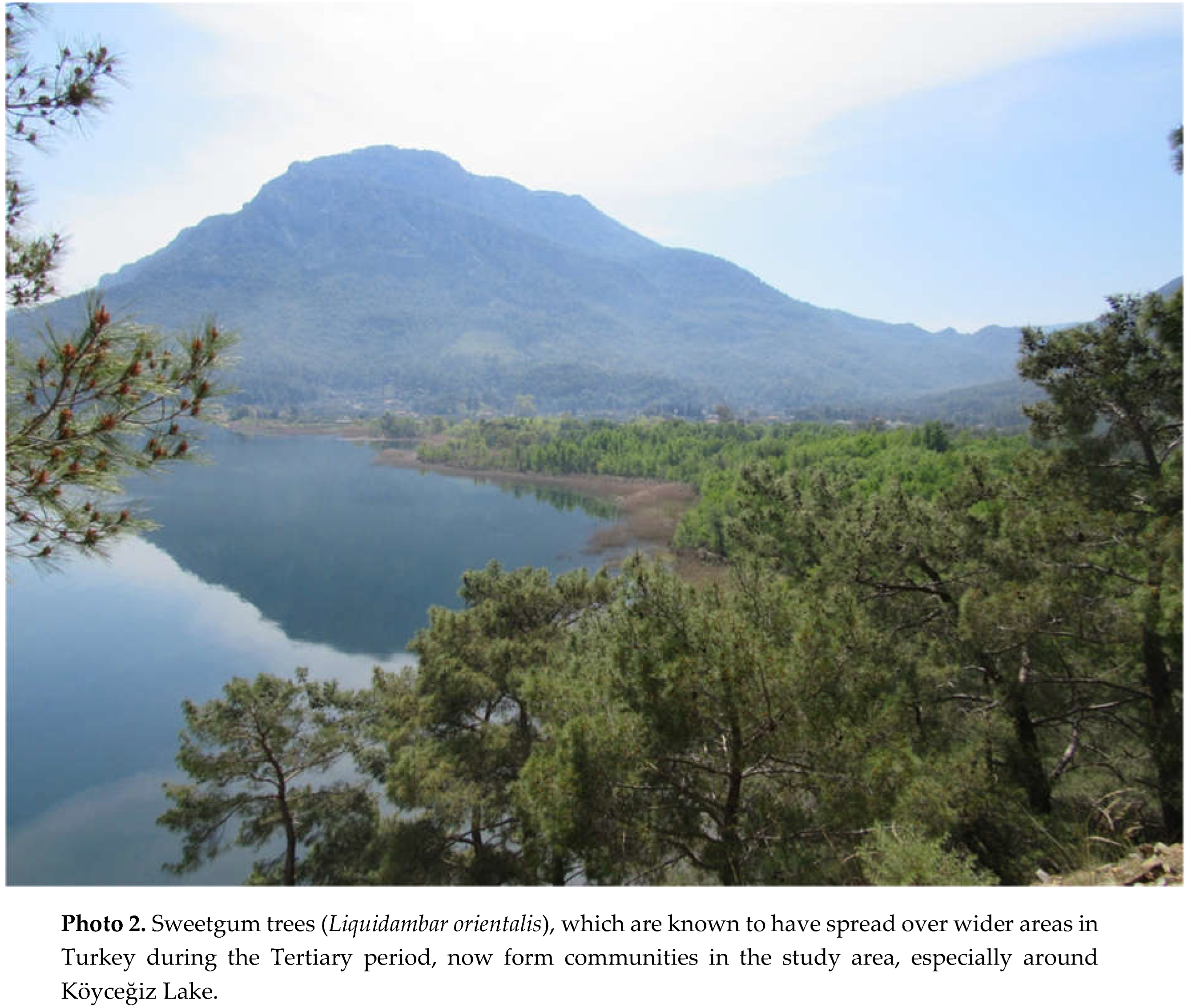

In response to changing climatic conditions, plants react mainly by expanding or contracting their range, among many other responses. Indeed, evidence from glacial and interglacial periods suggests that the dominant adaptive response of climate-limited plant species is to shift their distributions, resulting in movements towards altitude and the poles (Walther et al., 2005). For example, the sweetgum (Liquidambar orientalis) communities, which grow on the valley floors and slopes in our research area, is a Tertiary relic endemic, and while it was distributed in wider areas in our country in the Tertiary, it is now only found in an area limited to our research area due to changing climatic conditions (Photo 2). Again, as we have mentioned before, the topographical features of the study area and the resulting local climatic zones have made it a refuge for plants migrating during the last glacial period (Würm) and there are many species belonging to the Euro-Siberian phytogeographical region such as Salix alba, Populus alba and Carex outrage in the area. Studies show that plants respond to current climate changes in a similar way to those of the past. For example, holly (Ilex aquifolium), a climate-limited species, has been found to have expanded its range in southern Scandinavia over the last 30 years, consistent with increasing winter temperatures (Walther et al., 2005). Similarly, in Sweden (Scandes), the tree limit of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) has increased by 150-200 meters with increasing winter temperatures (Kullman 2006, 2007; Pauli et al., 2007). Again, Kullman (2007) states in his study that alpine and subalpine plant species have shifted an average of 200 m upslope, narrowing in the alpine zone (higher tree limit) and changing the landscape of alpine vegetation.

Extinction of Species

Although there is no record of any extinct plant species in the research area due to climate change today, the records of climate changes in the Pleistocene show that species that cannot keep up with the change are in danger of extinction. In particular, rapid change in ecological conditions can overwhelm the adaptive capacity of many species and lead to ecosystem reorganization and increasing numbers of extinctions. For example, studies show that plant species in mountainous areas and endemic and rare plants are more sensitive to changes in climate (Chersich et al. 2015; Li et al., 2018). In this respect, it would not be wrong to say that the research area is among the sensitive areas against changing climatic conditions with its rich mountainous ecosystem and plant species diversity, especially endemic plant species. As a matter of fact, as mentioned before, there are 15 important plant areas (IPA) in the research area, which are defined as areas with rich populations of rare, endangered or endemic plant species (

Table 3). When the table is analyzed, it is seen that more than 600 taxa, about 60% of which are endemic, are endangered in the area. We do not have enough data to say that this threat is related to climate change. These threats seem to be mostly related to land use, grazing, forest fires or over-collection of plants from nature. But as we also know, climate change could exacerbate existing threats to biodiversity. For example, changes in rainfall and temperature can alter the distribution of pests and weeds and create new opportunities for some species to become established (State of NSW and Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW 2010). In addition, there are many studies showing the effects of anthropogenic climate change on the increase in the number and impact area of forest fires, which are a significant threat to biodiversity today (Türkeş and Altan 2012; Abatzoglou and Williams 2016; Krikken et al. 2021). In the study of Türkeş and Altan (2012), which covers a large part of our research area, the relationship between droughts and forest fires is revealed and it is stated that this area, which is one of the most important areas of the Mediterranean climate zone with the most important climatic change in Turkey, may face more severe natural disasters in the future with climate change.

Another threat affecting plant biodiversity is the mismatch between the plant and its pollinators (e.g. insects) due to global warming. Mismatches in plant-pollinator interactions can occur temporally or spatially, with less coexistence of interacting partners in a shared habitat. Again, these mismatches may be due to a change in the flowering period of the plant and/or the phenology of the pollinator (Gérard et al. 2020). Recent studies also support the mismatches between phenological changes and plant/pollinator conflicts due to climate change and increasing temperatures (Memmott et al. 2007; Hegland et al. 2009; Byers 2017). Plants in our research area are under similar threats linked to increasing temperatures. This may also affect the reproductive potential of species, leading to a gradual decline in their populations.

Conclusion

As a result, the research area has an important place in Turkey's biodiversity with its rich plant species and diversity. However, today this diversity is threatened by human activities such as urbanization, land use, forest fires and deforestation, mining activities, and global climate change will make this threat even more serious. As a matter of fact, as a result of our study, it has been observed that there is a statistically significant increase in temperatures in the research area and a decreasing trend in annual total precipitation, although not statistically significant. It has also been determined that there are changes in the seasonal distribution of precipitation, for example, there is a general tendency to increase precipitation in the winter season and decrease precipitation in the summer season. Therefore, these changes, especially changes in temperatures, will affect plant biodiversity by prolonging the vegetation period and changing plant phenology.

References

- Abatzoglou, J. and Williams A.P., 2016. Impact of anthropogenic climate change on wildfire across western US forests, Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences, vol.113, no 42, 11770-11775.

- Bakkenes, M., Alkemade, J.R.M, Ihle, F.,.Leemans, R.and J.B.Latour,2002. Assessing Effects of Forecasted Climate Change on the Diversity and Distribution of European Higher Plants for 2050, Global Change Biology, 8, 390–407.

- Beniston, M. (ed.): 1994, Mountain Environment in Changing Climates, Routledge, London.

- Byers D., L., 2017. Studying Plant–Pollinator Interactions In A Changing Climate: A Review of Approaches, Applications in Plant Sciences, 5 (6), 1-15.

- Chersich S., Rejšek K., Vranová V., Bordoni M. and Meisina C., Climate change impacts on the Alpine ecosystem: an overview with focus on the soil – a revie, Journal of Forest Science, 61, 2015 (11): 496–514.

- Demir A., 2009. Küresel İklim Değişikliğinin Biyolojik Çeşitlilik ve Ekosistem Kaynakları Üzerine Etkisi, A.Ü. Çevre Bilimleri Dergisi, cilt 1, sayı 2, 37-54.

- Erlat E. and Yavaşlı D. D., 2011. Ege Bölgesi’nde Sıcaklık Ekstremlerinde Gözlenen Değişim ve Eğilimlerin Değerlendirilmesi, Ankara Üniversitesi Çevrebilimleri Dergisi, cilt 3, sayı 1, 25-37.

- Erlat E. and Türkeş M., 2013. Observed changes and trends in numbers of summer and tropical days, and the 2010 hot summer in Turkey, Int. J. Climatol. 33: 1898–1908.

- Erlat E. and Türkeş M., 2017. Türkiye’de Tropikal Gece Sayılarında Gözlenen Değişmeler Ve Eğilimler, Ege Coğrafya Dergisi, 26/2, 95-106.

- Feehan J., Harley M. and Minnen J. V., 2009. Climate change in Europe. 1. Impact on terrestrial ecosystems and biodiversity. A review, Agron. Sustain. Dev. 29, 409–421.

- Gérard M., Vanderplanck M., Wood T. and Michez D., 2020. Global warming and plant–pollinator mismatches, Emerging Topics in Life Sciences, 4, 77-86.

- Gottfried, M., H. Pauli,A. Futschik, M.Akhalkatsi, P. Barancok, J.L. Benito Alonso, G. Coldea, J. Dick, B. Erschbamer, M.R. Fernández Calzado, G. Kazakis, J. Krajci, P. Larsson, M. Mallaun, O. Michelsen, D. Moiseev, P. Moiseev, U. Molau, A. Merzouki, L. Nagy, G. Nakhutsrishvili, B. Pedersen, G. Pelino, M. Puscas, G. Rossi, A. Stanisci, J.-P. Theurillat, M. Tomaselli, L. Villar, P. Vittoz, I. Vogiatzakis, and G. Grabherr, 2012. Continent-wide response of mountain vegetation to climate change, Nature Climate Change, 2(2), 111-115.

- Guisan, A., Holten, J. I., Spichiger, R., and Tessier, L. (eds.): 1995, Potential Ecological Impacts of Climate Change in the Alps and Fennoscandian Mountains, Conservatoire et Jardin botaniques, Genève, p. 194.

- Hegland S. J., Nielsen A., Lazaro A., Bjerknes A.L. and Taoland O., 2009. How does climate warming affect plant-pollinator interactions?, Ecology Letters, 12, 184-195.

- Kienast, F., Wildi O. and Brzeziecki B., 1998. Potential Impacts Of Climate Change On Species Richness In Mountain Forests An Ecological Risk Assessment, Biological Conservation Vol. 83, No. 3, 291-305.

- Krikken, F., Lehner F., Haustein K., Drobyshev I. and Oldenborgh G.J., 2021. Attribution of the role of climate change in the forest fires in Sweden 2018, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 21, 2169–2179.

- Kullman, L. (2006) Long-term geobotanical observations of climate change impacts in the Scandes of West-Central Sweden, Nordic J. Bot. 24, 445–467.

- Kullman, L. (2007) Tree line population monitoring of Pinus sylvestris in the Swedish Scandes, 1973–2005: implications for tree line theory and climate change ecology, J. Ecol. 95, 41–52.

- Laušević, R., L. Jones-Walters and A. Nieto, 2008. Climate change and biodiversity in South-East Europe – impacts and action. REC, Szentendre, Hungary; ECNC, Tilburg, the Netherlands.

- Li, L., Zhang Y., Liu L., Wu J., Li S., Zhang H., Zhang B., Ding M., Wang Z. and Paudel B., 2018. Current challenges in distinguishing climatic and anthropogenic contributions to alpine grassland variation on the Tibetan Plateau, Ecology and Evolution. 2018;8, 5949–5963.

- Mason H., 1946. The Edaphic Factor in Narrow Endemism. II. The Geographic Occurrence of Plants of Highly Restricted Patterns of Distribution, Madrono, Vol 8, No 8, 241-257.

- Médail F and Diadema, K., 2009. Glacial refugia influence plant diversitypatterns in the Mediterranean Basin, Journal of Biogeography (J. Biogeogr.), 36, 1333–1345.

- Memmott, J., Craze P. G., Waser N. M. and Price M. V., 2007. Global warming and the disruption of plant–pollinator interactions, Ecology Letters, 10, 1-8.

- Özhatay N., Byfield A. and Atay S., 2008. Türkiye’nin 122 Önemli Bitki Alanı, WWW Türkiye (Doğal Hayatı Koruma Vakfı).

- Parmesan, C. and Yohe, G., 2003. A Globally Coherent Fingerprint of Climate Change Impacts Across Natural Systems, Nature, 421, ss. 37–42.

- Pauli H., Gottfried M., Reiter K., Klettner C., Grabherr G., 2007. Signals of range expansions and contractions of vascular plants in the high Alps: observations (1994–2004) at the GLORIA master site Schrankogel, Tyrol, Austria, Global Change Biol. 13, 147–156.

- Pauli, H., M. Gottfried, S. Dullinger, O. Abdaladze, M. Akhalkatsi, J.L. Benito Alonso, G. Coldea, J. Dick, B. Erschbamer, R. Fernández Calzado, D. Ghosn, J.I. Holten, R. Kanka, G. Kazakis, J. Kollár, P. Larsson, P. Moiseev, D. Moiseev, U. Molau, J. Molero Mesa, L. Nagy, G. Pelino, M. Puşcaş, G. Rossi,A. Stanisci,A.O. Syverhuset, J.-P.Theurillat, M.Tomaselli, P. Unterluggauer, L.Villar, P.Vittoz, and G. Grabherr, 2012. Recent plant diversity changes on Europe’s mountain summits, Science, 336(6079), 353-355.

- Richard P., G., Gillet M., Vengeon J. M., Genon S. D., Einhorn B. ve Deniset T., 2008. Climate Change in the Alps: Impacts and Natural Hazards, Rapport Technique N°1 de l’ONERC.

- Sütgibi S., 2023. Ege Bölgesi’nde Vejetasyon Süresi ile Vejetasyon Dönemi Başlama ve Son Bulma Tarihlerindeki Değişme ve Eğilimler. Coğrafya Dergisi(46), 31-38.

- Şen Ö. L., Bozkurt D., Göktürk O. M., Dündar B. and Altürk B., 2017. Türkiye’de İklim Değişikliği ve Olası Etkileri, 3. Taşkın Sempozyumu, Bildiriler Kitabı.

- Şimşek O., Nadaroğlu Y., Yücel G., Dokuyucu Ö., Gökdağ Ş.A., 2014. Türkiye Fenoloji Atlası, T.C. Orman ve Su İşleri Bakanlığı Meteoroloji Genel Müdürlüğü Araştırma Dairesi Başkanlığı.

- Türkeş, M. and Altan G., 2012. Muğla Orman Bölge Müdürlüğü’ne bağlı orman arazilerinde 2008 yılında çıkan yangınların kuraklık indisleri ile çözümlenmesi, Uluslararası İnsan Bilimleri Dergisi cilt 9, sayı 1, 912-931.

- Türkeş, M., 2012. Türkiye’de Gözlenen ve Öngörülen İklim Değişikliği, Kuraklık ve Çölleşme, Ankara Üni. Çevrebilim Dergisi, 4 (2), 1-32.

- Türkeş, M., 2022. Hükümetler arası İklim Değişikliği Paneli’nin (IPCC) Yeni Yayımlanan İklim Değişikliğinin Etkileri, Uyum ve Etkilenebilirlik Raporu Bize Neler Söylüyor? Dirençlilik Dergisi 6(1), 197-207.

- Türkoğlu N., Çiçek İ. and Şensoy S., 2014. Türkiye’de İklim Değişikliğinin meyve Ağaçları ve Tarla Bitkilerinin Fenolojik Dönemlerine Etkileri, TÜCAUM VIII. Coğrafya Sempozyumu, Bildiriler Kitabı, s.60-71, 23-24 Ekim 2014, Ankara.

- Walther, G.R., Berger S. and Sykes M.T., 2005. An ecological ‘footprint’ of climate change, Proceedings of The Royal Society 272, 1427-1432.

- State of NSW and Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW 2010. Priorities for Biodiversity Adaptation to Climate Change.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).