Introduction

The reflection index (RI), calculated from digital photoplethysmography, is a measure of resistance vessel and small to medium sized artery compliance (1). It is strongly correlated with the augmentation index (AIx) calculated from other methods of pulse wave analysis (1). AIx is a predictor of future major adverse cardiac events (MACE) (2), particularly in young healthy individuals, but appears to be less predictive of MACE in older subjects and in women (3-5). It is correlated with pulse wave velocity (PWV) in young persons and women, but this association is less apparent in older subjects or patients with cardiovascular disease (6,7). There is less information about the value of RI as a predictor of MACE, but it may have similar associations as AIx.

There is no data on the effects of antioxidant therapy on RI. AIx had been reported to be significantly reduced by about 4.6% during therapy with antioxidants in a meta-analysis of randomised trials that studied the effects of vitamins C and E, beta carotene or their combinations (8). Individual trials examining the effects of dietary or medicinal antioxidant therapy with single antioxidants have shown either no or little change in AIx (9-12). However, the combination of vitamin C and vitamin E has shown a significant reduction in AIx of about 8% in untreated hypertensive men (13). Treatment using multiple antioxidants in animal models of vascular disease has been more effective in improving vascular function than treatment with individual antioxidants (14).

We have previously reported that stiffness index (SI), measured by digital photoplethysmography, (which is closely related to pulse wave velocity, a measure of large arterial stiffness), was significantly reduced by 19% during therapy with a combination of 4 antioxidants (15). We simultaneously measured RI in the study, and this report presents the changes in RI in response to this combination antioxidant therapy.

Methods

Study Design and Subjects

The study followed a single blind, randomised, parallel group design of two weeks of treatment with either the antioxidant formulation or placebo in a diverse group of subjects. A single blind design was used because of difficulty obtaining matching placebos and because the outcomes assessed were measured by electronic devices which avoid the possibility for observer bias. The intention was to study 100 subjects with 50 subjects randomised to each treatment arm. The only exclusion criteria were the presence of atrial fibrillation or medication with antioxidant supplements. A diverse group of subjects representative of the general population was chosen so that the results would be of relevance to all groups that may choose to take antioxidant supplements, and to determine whether there were signals to suggest which patient characteristics predicted large changes in RI. The subjects were recruited by word of mouth, from patients attending a general practice clinic and from social groups at housing estates.

Study Procedures

The subjects attended on the first occasion to sign a consent form and for the recording of demographic data and vital signs. Baseline recordings RI were performed after resting in a seated position for 10 minutes. The subjects were then given a bottle containing greater than two weeks supply of the antioxidant formulation or placebo according to a randomisation schedule. The schedule was created by an independent pharmacist who sealed the randomisation schedule in an envelope that remained sealed until the data collection had been completed. Randomisation was performed in blocks of four. The subjects were instructed not to change their medication and to maintain the usual diet, caffeine and alcohol intake and to continue their usual level of physical activity until the study was completed.

The subjects were instructed to take their study medication in the morning at the same time each day and to attend two weeks after the first visit at the same time and same day of the week as at the first visit. At the second visit recordings of RI were again performed approximately 4 hours after taking their medication. Vital signs were recorded, and the subjects were questioned about the occurrence of possible adverse events. The bottles of study medication were returned, and the remaining tablets counted to determine compliance.

Measurement of RI

RI was measured in the sitting position after 10 minutes of rest using a Pulse Trace recorder (Micro Medical, Gillingham, Kent, UK). Six initial recordings were made to ensure that a stable, good quality arterial waveform was displayed on the monitor after which three further recordings were made and the mean values of RI from these three recordings were entered as the baseline and outcome measurements. SI was measured simultaneously with RI. Patients in whom the Pulse Trace recorder could not calculate RI (usually because of the absence of a recognisable reflected pulse wave) could not be included in the efficacy analysis but were included in the safety assessment.

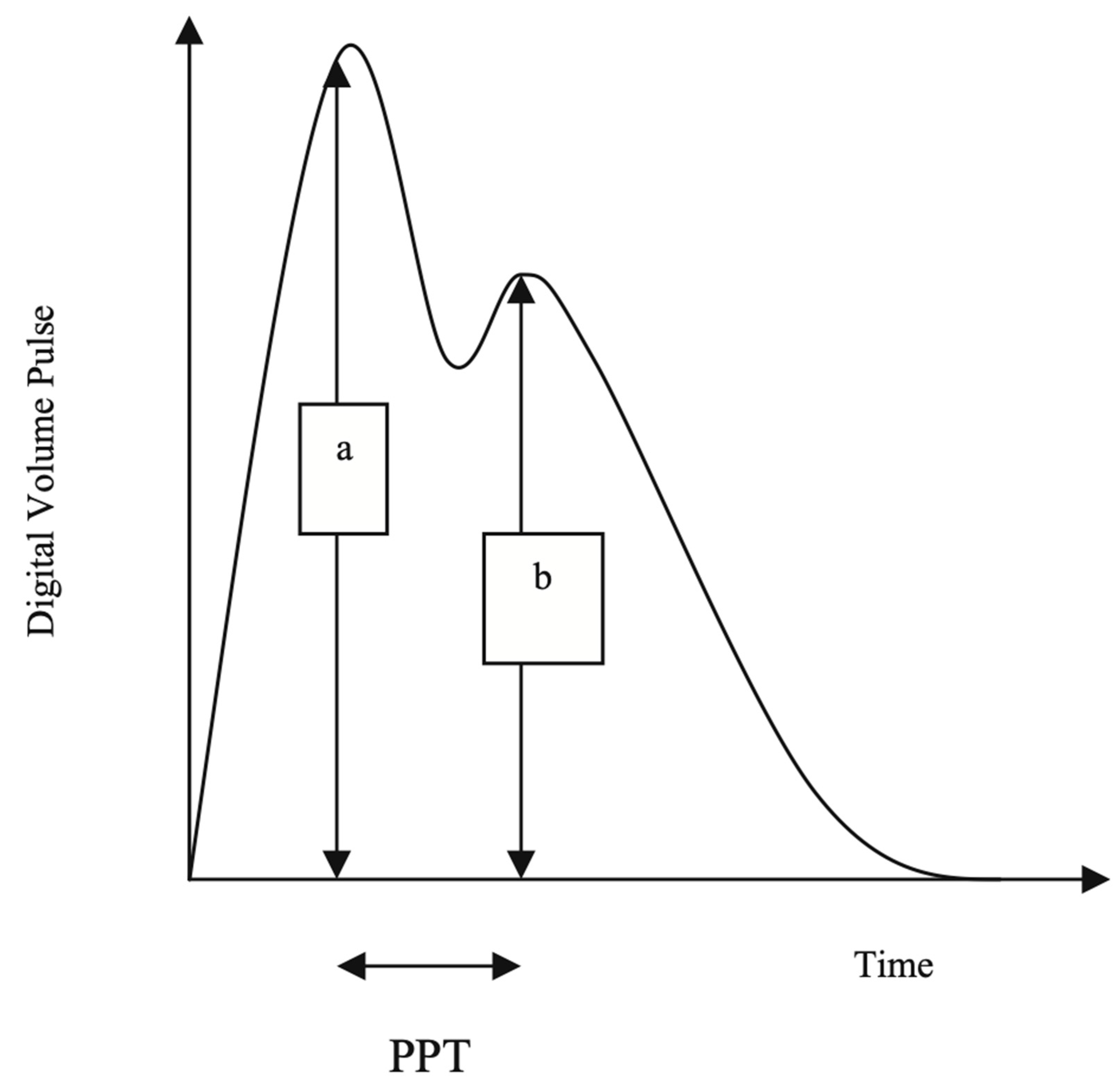

The Pulse Trace recorder uses a digital photoplethysmograph transmitting infrared light technique from a finger cuff applied to the left index finger. The amount of light transmitted through the finger varies proportionally to changes in its blood volume. The signal from the photoplethysmograph obtained over a 30-s period is averaged by the system, to produce a single digital volume pulse (DVP) waveform (

Figure 1). The peripheral pressure pulse has been shown to be related to the DVP by a single generalized transfer function, which is inbuilt in the Pulse Trace system (18).

The DVP wave (

Figure 1) consists of an early systolic peak (a), which results from an increase in digital blood volume from a pressure wave transmitted from the left ventricle to the finger along a direct path. The second peak, (b), occurs in diastole, and is formed by pressure waves reflected up to the aorta and thence to the finger, from sites of impedance mismatch in the lower body.

An index of small to medium-sized arterial stiffness can be derived from the magnitude of the reflected waves from the lower limbs to the aorta. RI is measured as b/a X 100%.

The time between the systolic and diastolic peaks (peak to peak time, PPT) can be used to infer the time taken for the pressure wave to travel from the aorta to the lower body, and then as a reflected wave back up to the aorta to the finger. This path length is unknown but is proportional to the subject’s height (h). An index of large arterial stiffness (SI) can therefore be derived, like the calculation of pulse wave velocity (PWV) by the formula: h/PPT. SI has been shown to be strongly correlated to central (aortic and carotid femoral) PWV (18).

A previous study in 115 subjects reported good intra-individual reproducibility, with a co-efficient of variation (CV) and for RI of 5%, and a CV of 8% for SI (19).

Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as the mean and standard deviation.

The change in RI (and SI), blood pressures and heart rate from baseline following the two-week treatment period was calculated. Differences between antioxidant and placebo treatments for change from baseline were analysed using Student’s t test. Estimates of the effect size were made according to the method of Cohen (difference between means divided by the pooled standard deviation) (20), or if there was a substantial difference between the standard deviation of the change from baseline between antioxidant and placebo therapy, by the method of Glass (difference between the means divided by the standard deviation of the control group) (21). Effect sizes of 0.3 or less are weak, those greater than 0.8 are strong and those greater than 1.2 are very strong (21). Predictors of change of RI were analysed by linear regression (age, gender, body mass index, SBP heart rate and change in SI).

Baseline differences between the two-treatment group were made using Student’s t test or the Chi square test for categorical variables.

The number of subjects required to detect a difference in RI between baseline and the end of the 2 -week treatment period of 10% between antioxidant and placebo groups (with a power of 80%, assumed equal standard deviations of 5% and alpha = 0.05 two tailed) was calculated to be 42 subjects in each group. A standard deviation of 5% was calculated from previously collected data (19), and 10% was the smallest change from baseline in RI between groups considered to be clinically significant. A sample size of 50 subjects in each group was chosen to allow for dropouts and failure to obtain arterial waveforms suitable for analysis.

Ethics

The subjects signed a consent form before any research activities commenced. The study conformed with the declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the Gold Coast University Hospital Human Ethics Committee.

Results

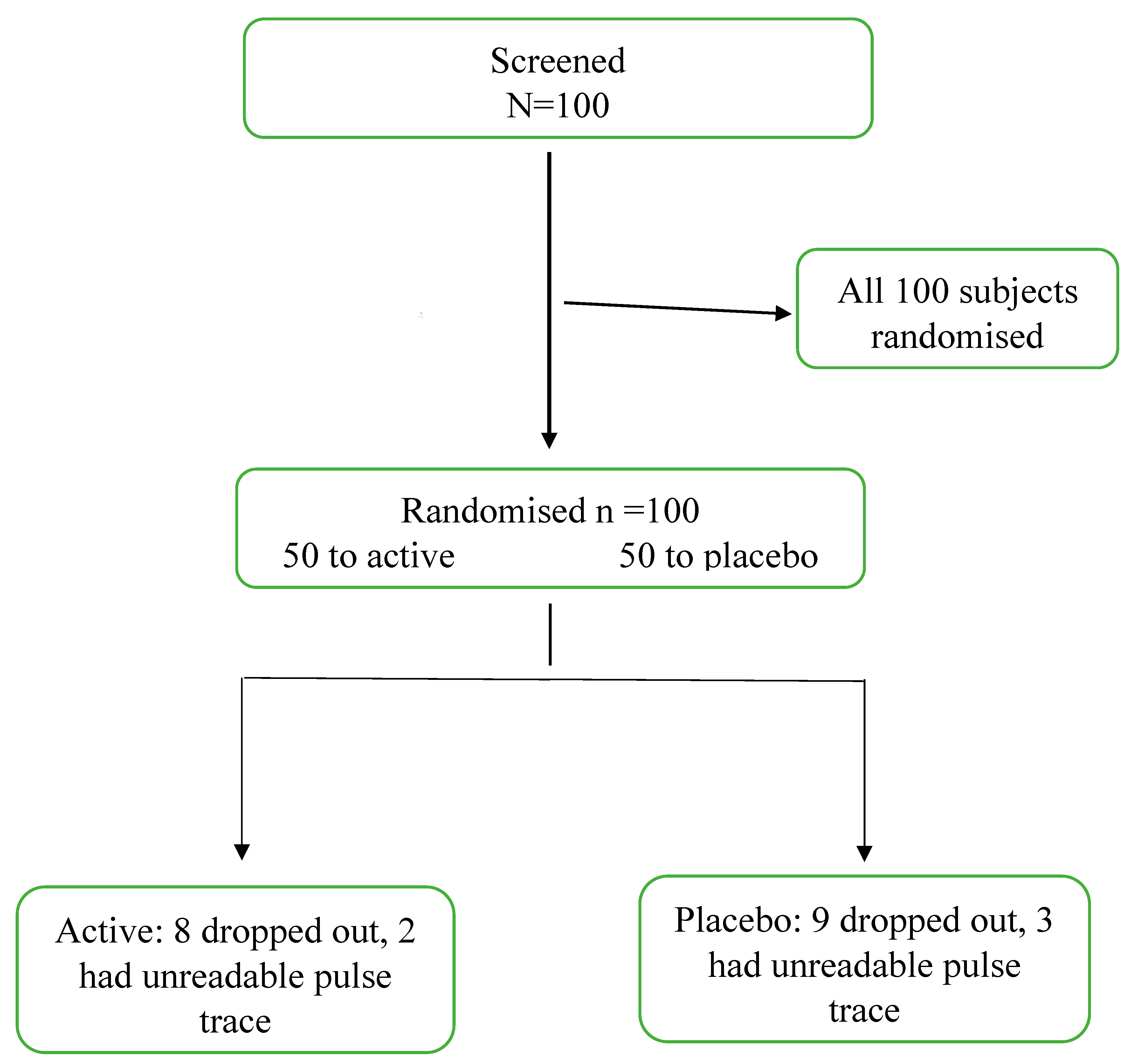

One hundred subjects were enrolled in the study and randomised to antioxidant or placebo therapy. Fifteen patients failed to attend for the second study day and 7 subjects had arterial waveforms that could not be analysed. A total of 40 subjects who were randomised to the antioxidant treatment and 38 patients randomised to placebo had complete data sets. A Consort flow chart is presented in

Figure 2.

The baseline characteristics and the changes from baseline to the end of study of RI, SI, blood pressures and heart rates are presented in

Table 1. The antioxidant and placebo groups were well matched apart from BMI which was slightly but statistically significantly higher in the antioxidant placebo group.

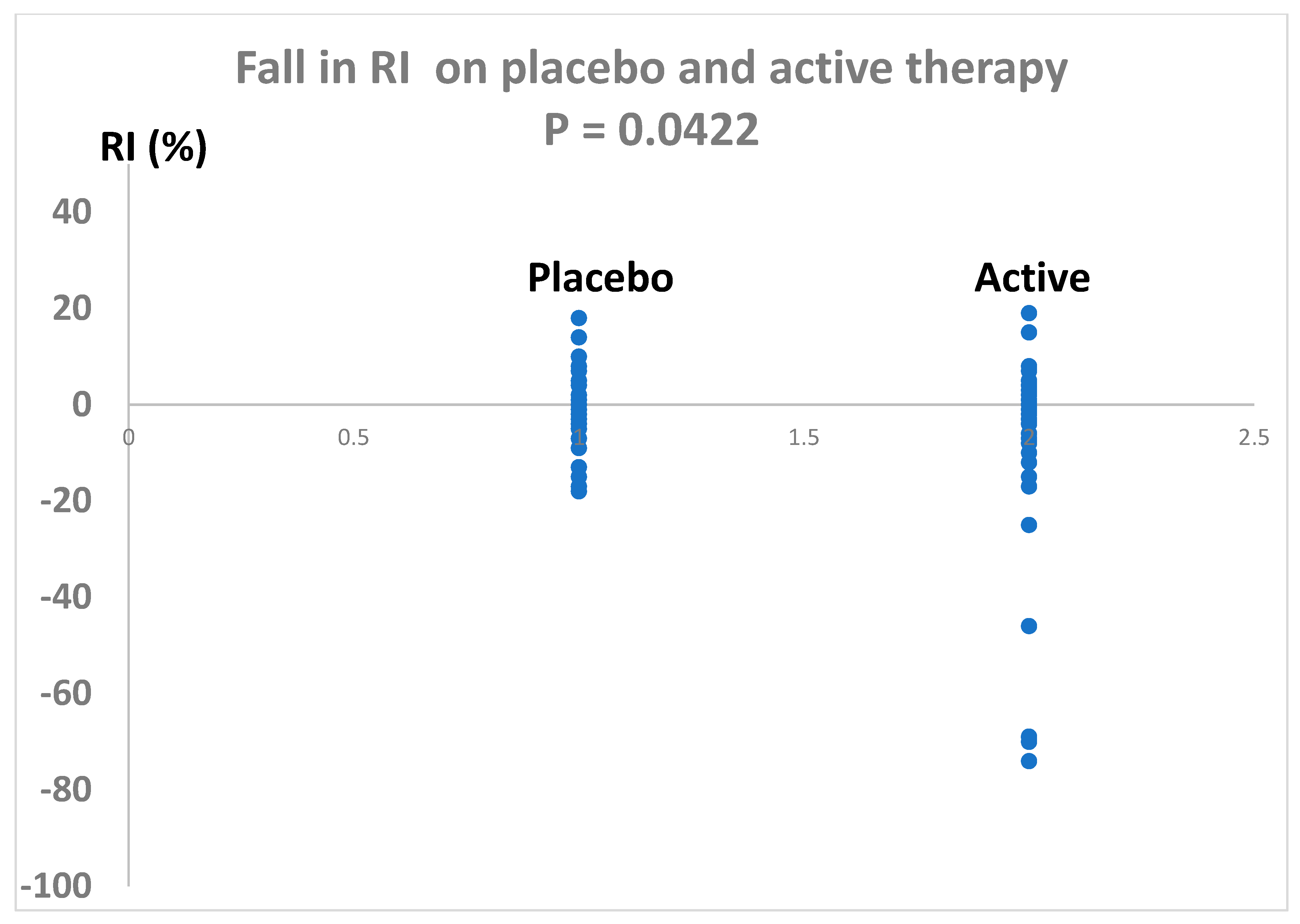

Antioxidant therapy significantly reduced RI by - 8% (placebo corrected) with 95% confidence levels of -1% to -15% (P = 0.0422). The variance for the change in RI from baseline was 526 for the antioxidant therapy and 64 fror the placebo group.The effect size for the fall in RI, calculated by the method of Glass (because of unequal variances between antioxidant and placebo therapies), was 1.0 which indicates a strong treatment effect.

Figure 2.

Consort diagram. Active = antioxidant therapy.

Figure 2.

Consort diagram. Active = antioxidant therapy.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and change from baseline at the second study day. Values are the mean ± standard deviation. P value for comparisons between the antioxidant and placebo therapies (Students t test).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and change from baseline at the second study day. Values are the mean ± standard deviation. P value for comparisons between the antioxidant and placebo therapies (Students t test).

| |

Antioxidant n= 40 |

Placebo n=38 |

P |

| Gender |

40%

60% |

34%

66% |

- |

| Age (years) |

62 ± 13 |

63 ± 10 |

0.83 |

| SBP (mmHg) |

138 ± 21 |

136 ± 14 |

0.62 |

| Change in SBP (mmHg) |

1 ± 17 |

-2 ± 10 |

0.27 |

| DBP (mmHg) |

81 ± 11 |

83 ± 10 |

0.45 |

| Change in DBP (mmHg) |

2 ± 9 |

-1 ± 9 |

0.20 |

| BMI (kg/m2) |

27 ± 4 |

30 ± 6 |

0.44 |

| RI (%) |

63 ± 21 |

58 ± 8 |

0.04 |

| Change in RI (%) |

- 9 ± 23 |

-1 ± 8 |

0.04 |

| SI (m/sec) |

8.97 ± 3.20 |

8.78 ± 3.73 |

0.81 |

Change in SI

(m/sec) |

-1.95 ± 3.20 |

-0.30 ± 1.14 |

0.002 |

Figure 3.

Change in RI following two weeks of antioxidant combination (active) compared with placebo. P= 0.0422 (Students t test).

Figure 3.

Change in RI following two weeks of antioxidant combination (active) compared with placebo. P= 0.0422 (Students t test).

The change in RI on antioxidant treatment was significantly and positively related to age (r =0.354, P = 0.022), but no significant relationship between age and change in RI was found for subjects on placebo (r = 0.125, P = 0.452). Large reductions in RI on antioxidant therapy tended to occur mainly in the older subjects.

The change in RI was strongly correlated to the change in SI both in subjects on antioxidant therapy (r = 0.882, P < 0.0001) and in subjects on placebo therapy (r = 0.530, P = 0.0006). There were no significant relationships between the change in RI and changes in SBP, DBP or HR, nor with gender or BMI.

Compliance with medication was greater than 80% in all patients and there were no reported adverse events.

Discussion

The antioxidant combination therapy reduced RI compared to placebo with an effect size of 1.0 using the method of Glass (21), indicating a strong effect of the antioxidants in reducing RI. The placebo corrected percent fall in RI (-8% with 95% confidence limits of -1% and -15%) was not as marked as the -19% fall that we observed for SI (95% confidence interval of -9% to 31%) (15). This reduction in RI compares forourably the reduction in AIx than has been reported for antioxidant therapies in a meta-analysis (effect size 0.20, approximate equating to a mean fall of AIx of less than -4.0%) (8), a standardised mean difference which is considered to be a weak effect (20). However, while the effect size for RI in our study appeared higher that most other studies of AIx, it should be noted that the 95% confidence intervals for the change RI in our study encompassed the possibily that we were equivalent to the fall in AIx found in other studies of antioxidant therapy that had statistically significant outcomes (8). Interestingly, subjects with low plasma antioxidant activity have been reported to have elevated AIx levels (22).

Combinations of antioxidant multiflavones with exercise have found acute reductions in Aix of approximately 15% (23). However, it was unclear how much of the effect was due to exercise, which may acutely reduce AIx (24).

The change in RI was significantly related to age in subjects on antioxidant therapy but not in the subjects on placebo. AIx has been reported to be significantly related to age in younger subjects but this association does not occur in patients over the age of 60 years (24). Combination antioxidant therapy may improve both central and peripheral artery function and restore the relationship between the compliance of central and peripheral arteries to that observed in young people.

The mechanisms involved in the reduction of RI during antioxidant therapy are uncertain but may result from a reduction of free radicals on the walls of resistance vessels and small to medium sized arteries. Antioxidants inactivate free radicals, reduce inflammation, and, therefore, protect the integrity of the artery wall (26,27).

The present study suggests that the antioxidant therapy that was used may be useful in assisting strategies for reducing cardiovascular disease. However, RI or AIx are not as predictive of MACE as SI or PWV, so the reduction is SI that we previously reported (15), which was greater than 2 times the effect that we observed on RI, may be a more useful predictor of future MACE. The reduction in MACE predicted by the effects of RI and SI of the antioxidant combination we have studied must be confirmed by future studies of cardiovascular outcomes. Studies of the effects of antioxidant supplementation in improving clinical outcomes have so far been disappointing (28).

The diverse population that we studied was associated with a much greater variance in the change in RI on the antioxidant combination than on placebo. It is possible that this may indicate the presence of individuals or groups that have a greater reduction in RI than others. The change in RI was greater in older subjects, suggesting that older patients may achieve the greatest benefit from combination antioxidant therapy. Further studies in population subgroups are needed to identify which patients are likely gain the greatest benefit from combination antioxidant therapy.

The optimal duration of treatment with antioxidants to achieve benefits in vascular function is uncertain. The meta-analysis of previous studies of antioxidants found that the reduction in measures of vascular compliance was similar during short term and long-term therapy (8). The decision to treat the subjects in the present study for 2 weeks was arbitrary. Further studies are needed to determine whether the changes that occurred after 2 weeks of treatment persist during long term therapy.

The reduction in Ri of 8% in the present study of combination antioxidant therapy compares favourably with other interventions that been evaluated for as possible ways of reducing RI or Aix. These have generally found reductions of 4.0% or less and have included the effects of antihypertensives (29), statins (30), exercise (31), alcohol consumption (32), hormone replacement therapy (33), isoflavones (34) and fenofibrate therapy (35). The exception is nitrate administration which has been reported to be accompanied by an acute reduction in AIx of -9.5 to -12% (36).

The single blinded design of the present study and the use of a placebo which differed in appearance to the antioxidant formulation may be a possible limitation of the study. However, RI was calculated by an electronic device (the Pulse Trace monitor) which may protect against observer bias.

We did not obtain information about the subjects’ medical conditions or drug therapy to investigate whether these factors influenced the effect of the antioxidant therapy on RI. An analysis of the effects of medical disorders and therapy was beyond the scope of the present study which was intended to determine the effects of the antioxidant therapy on RI in a broad cross section of the community. Further studies are needed to examine the effects of the combination antioxidant in subgroups of the general population.

In conclusion, supplementation with a mixture of several potent antioxidants improves RI to an extent that is greater than or equal to the reduction generally observed for other factors that have studied to determine whether they reduce Aix. However, the reduction was not as impressive as the reduction observed for SI (15).

Author Contributions

L.G.H.—conceptualisation, protocol development, analysis of data, writing, and editing manuscript. T.U.—recruiting of patients, collection of data, editing of manuscript. A.H.—recruiting of patients, collection of data, editing of manuscript. J.B.H.—coordination of study supervision of data collection, checking of data prior to analysis, assistance with writing and editing the manuscript. R.J.—conceptualisation, protocol development, writing, and editing manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No specific funding was obtained for this study. All persons involved gave their time freely. Study product and Placebo was provided by Phoenix Pharmaceuticals proprietary Limited.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Gold Coast University Hospital Human Ethics Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Inform consent was obtained in writing and compliance with GCP guidelines prior to any study related procedure.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from L.G.H.

Conflicts of Interest

J.B.H. is the CEO of Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, which supplied the active and placebo study medications. There were no other potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Woodman, R.J.; Watts, G.F.; Kingwell, B.A.; Dart, A.M. Interpretation of the digital volume pulse: its relationship with large and small artery compliance. Clin Sci 2003, 104(3), 283–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janner, J.H.; Godtfredsen, N.S.; Ladelund, S.; Vestbo, J.; Prescott, E. The association between aortic augmentation index and cardiovascular risk factors in a large unselected population. J Human Hypertens 2012, 26(8), 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janner, J.H.; Godtfredsen, N.S.; Ladelund, S.; Vestbo, J.; Prescott, E. High aortic augmentation index predicts mortality and cardiovascular events in men from a general population, but not in women. Eur J Prevent Cardiol. 2013, 20(6), 1005–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, B.G.; Park, J.B.; Cho, S.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Choi, S.M.; Park, J.H.; Park, Y.H.; Choi, J.O.; Lee, S.C.; Park, S.W. Pulse wave velocity is more closely associated with cardiovascular risk than augmentation index in the relatively low-risk population. Heart Vessel. 2009, 4, 413–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janner, J.H.; Godtfredsen, N.S.; Ladelund, S.; Vestbo, J.; Prescott, E. The association between aortic augmentation index and cardiovascular risk factors in a large unselected population. J Human Hypertens. 2012, 1, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, Y.; Kario, K.; Ishikawa, J.; Eguchi, K.; Hoshide, S.; Shimada, K. Reproducibility of arterial stiffness indices (pulse wave velocity and augmentation index) simultaneously assessed by automated pulse wave analysis and their associated risk factors in essential hypertensive patients. Hypertens Res. 2004, 27(11), 851–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanai, H. Correlations of arterial stiffness and augmentation index with metabolic risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Hypertens 2016, 18(6), 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashor, A.W.; Siervo, M.; Lara, J.; Oggioni, C.; Mathers, J.C. Antioxidant vitamin supplementation reduces arterial stiffness in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Nutrit 2014, 144(10), 1594–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magagna A, Plantinga Y, Salvini S, Ceroti M, Masala G, Ghiadoni L, Taddei S, Palli D, Salvetti A. 10.31 Habitual Dietary Antioxidant Intake, Flow Mediated Dilation and Augmentation Index in Hypertensive Patients and Normotensive Controls. High Blood Press Cardiovasc Preven. 2007, 14, 145.

- Ruel, G.; Lapointe, A.; Pomerleau, S.; Couture, P.; Lemieux, S.; Lamarche, B.; Couillard, C. Evidence that cranberry juice may improve augmentation index in overweight men. Nutrit Res. 2013, 33(1), 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.Y.; Isaac, H.B.; Wang, H.; Huang, S.H.; Long, L.H.; Jenner, A.M.; Kelly, R.P.; Halliwell, B. Cautions in the use of biomarkers of oxidative damage; the vascular and antioxidant effects of dark soy sauce in humans. Biochem Biophysical Res Com. 2006, 344(3), 906–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasool, A.H.; Rahman, A.R.; Yuen, K.H.; Wong, A.R. Arterial compliance and vitamin E blood levels with a self emulsifying preparation of tocotrienol rich vitamin E. Arch Pharmacol Res. 2008, 31, 1212–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plantinga, Y.; Ghiadoni, L.; Magagna, A.; Giannarelli, C.; Franzoni, F.; Taddei, S.; Salvetti, A. Supplementation with vitamins C and E improves arterial stiffness and endothelial function in essential hypertensive patients. Am J Hypertens. 2007, 20(4), 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orella-Urugua, S.; Briones-Valdivics, C.; Chichirelli, S.; Saso, L.; Rodrig, R. Potential role of natural antioxidants in countering Reperfusion Injury in Acute Myocardial Infarction and Ischemic Stroke. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howes, L.G.; Unni, T.; Hamza, A.; Howes, J.B.; Jayasinghe, R. Reduction in Arterial Stiffness Index (SI) in Response to Combination Antioxidant Therapy. J Clin Med. 2023, 12(21), 6804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinton, J.B.; Kemm, R.M.; Howes, L.G. A post marketing evaluation of Rapid Recovery in relieving symptoms of hangover. Clin. Res. Trials 2018, 4, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Mackus, M.; Van De Loo, A.J.; Garssen, J.; Kraneveld, A.D.; Scholey, A.; Verster, J.C. The Role of Alcohol Metabolism in the Pathology of Alcohol Hangover. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millasseau, S.C.; Guigui, F.G.; Kelly, R.P.; Prasad, K.; Cockcroft, J.R.; Ritter, J.M.; Chowienczyk, P.J. Noninvasive assessment of the digital volume pulse: Comparison with the peripheral pressure pulse. Hypertens 2000, 36, 952–956. [Google Scholar]

- Brillante, D.G.; O’Sullivan, A.J.; Howes, L.G. Arterial stiffness indices in healthy volunteers using non-invasive digital photoplethysmography. Blood Press. 2008, 17, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ledesma, R.D.; Macbeth, G.; Cortada de Kohan, N.U. Computing effect size measures with ViSta-the visual statistics system. Tut. Quantit. Meth. Psychol. 2009, 5, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, G.M.; Feinn, R. Using effect size—Or why the P value is not enough. J. Grad. Med. Ed. 2012, 4, 279–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedikli, O.; Ozturk, S.; Yilmaz, H.; Baykan, M.; Kiris, A.; Durmus, I.; Karaman, K.; Karahan, C.; Celik, S. Low total antioxidative capacity levels are associated with augmentation index but not pulse-wave velocity. Heart and vessels. 2009, 24, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kappus, R.M.; Curry, C.D.; McAnulty, S.; Welsh, J.; Morris, D.; Nieman, D.C.; Soukup, J.; Collier, S.R. The effects of a multiflavonoid supplement on vascular and hemodynamic parameters following acute exercise. Oxidat Med Cellul Longevity 2011, 4, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiston, E.M.; Ballantyne, A.; La Salvia, S.; Musante, L.; Erdbrügger, U.; Malin, S.K. Acute exercise decreases insulin-stimulated extracellular vesicles in conjunction with augmentation index in adults with obesity. J Physiol 2023, 601(22), 5033–5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomiyama, H.; Odaira, M.; Kimura, K.; Matsumoto, C.; Shiina, K.; Eguchi, K.; Miyashita, H.; Shimada, K.; Yamashina, A. Differences in effects of age and blood pressure on augmentation index. Am J Hyperten. 2014, 27(12), 1479–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betuil, O.; Fuet, G.M.; Zeliha, S.; Engrin, S.E. The investigation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potentials of apitherapeutic agents on heart tissues in nitric oxide synthase inhibited rats via N-omega-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 2021, 43, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Correa, M.L.; Hayes, W.G. Arterial compliance and endothelial function. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2007, 7, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y.; Li, J.; Yuan, Z. Effect of antioxidant vitamin supplementation on cardiovascular outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manisty, C.H.; Hughes, A.D. Meta-analysis of the comparative effects of different classes of antihypertensive agents on brachial and central systolic blood pressure, and augmentation index. Brit J Clin Pharmacol. 2013, 75(1), 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahebkar A, Pećin I, Tedeschi-Reiner E, Derosa G, Maffioli P, Reiner Ž. Effects of statin therapy on augmentation index as a measure of arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2016, 212, 160–168.

- Pierce, D.R.; Doma, K.; Leicht, A.S. Acute effects of exercise mode on arterial stiffness and wave reflection in healthy young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Physiol. 2018, 9, 328759, (acute exercise -4.5%). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAnulty, L.S.; Collier, S.R.; Hubner, M.L.; Anoufriev, G.; McAnulty, S.R. Chronic and acute effects of red wine versus red muscadine grape juice on body composition, blood lipids, vascular performance, inflammation, and antioxidant capacity in overweight adults. Int J Wine Res. 2019, 3, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayward, C.S.; Knight, D.C.; Wren, B.G.; Kelly, R.P. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on non-invasive cardiovascular haemodynamics. J Hypertens. 1997, 15(9), 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man, B.; Cui, C.; Zhang, X.; Sugiyama, D.; Barinas-Mitchell, E.; Sekikawa, A. The effect of soy isoflavones on arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Nutrit. 2020, 60, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiukka, A.; Westerbacka, J.; Leinonen, E.S.; Watanabe, H.; Wiklund, O.; Hulten, L.M.; Salonen, J.T.; Tuomainen, T.P.; Yki-Järvinen, H.; Keech, A.C.; Taskinen, M.R. Long-term effects of fenofibrate on carotid intima-media thickness and augmentation index in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008, 52(25), 2190–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greig, L.D.; Leslie, S.J.; Gibb, F.W.; Tan, S.; Newby, D.E.; Webb, D.J. Comparative effects of glyceryl trinitrate and amyl nitrite on pulse wave reflection and augmentation index. Brit J Clin Pharmacol. 2013, 75(1), 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).