Submitted:

03 January 2025

Posted:

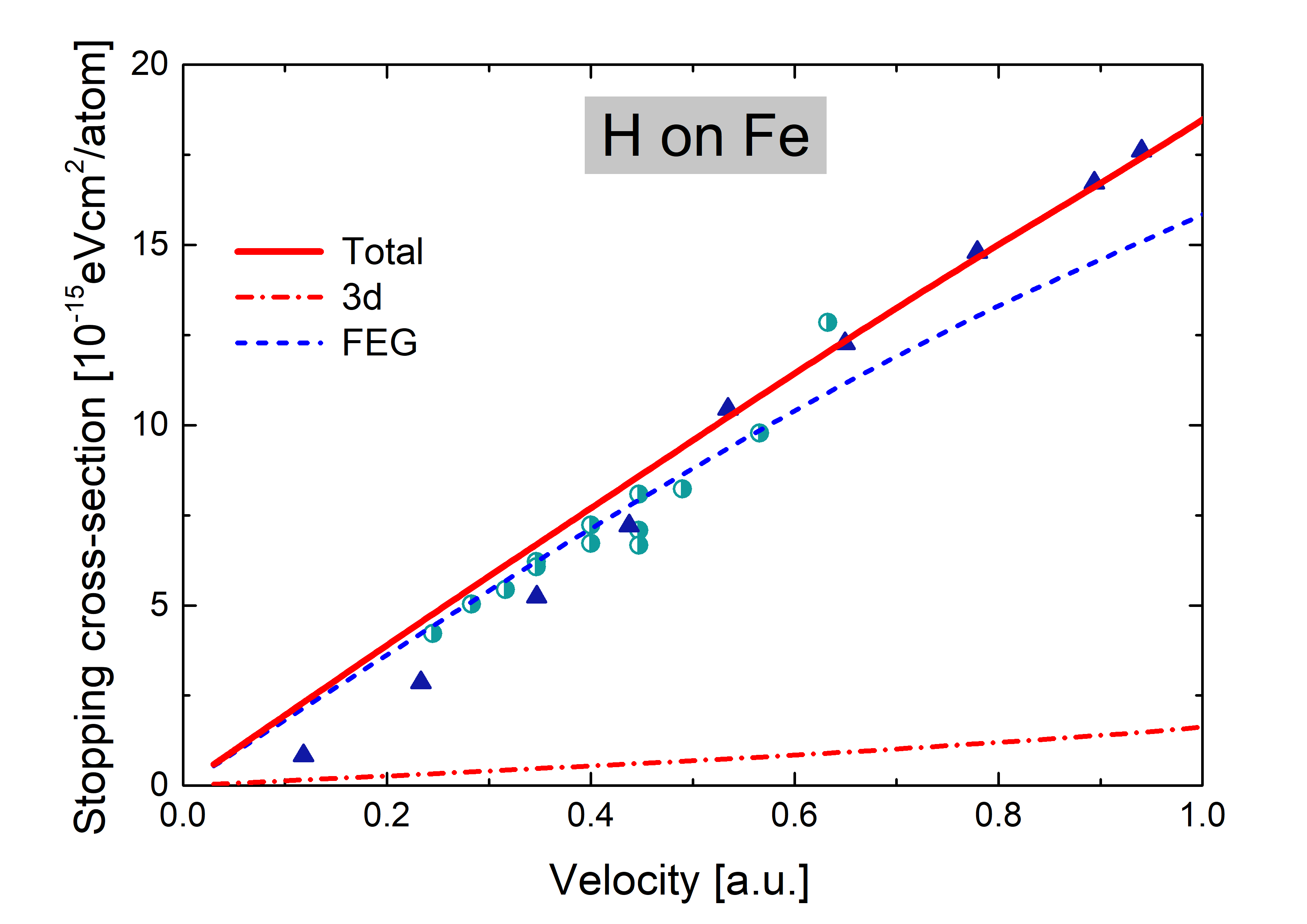

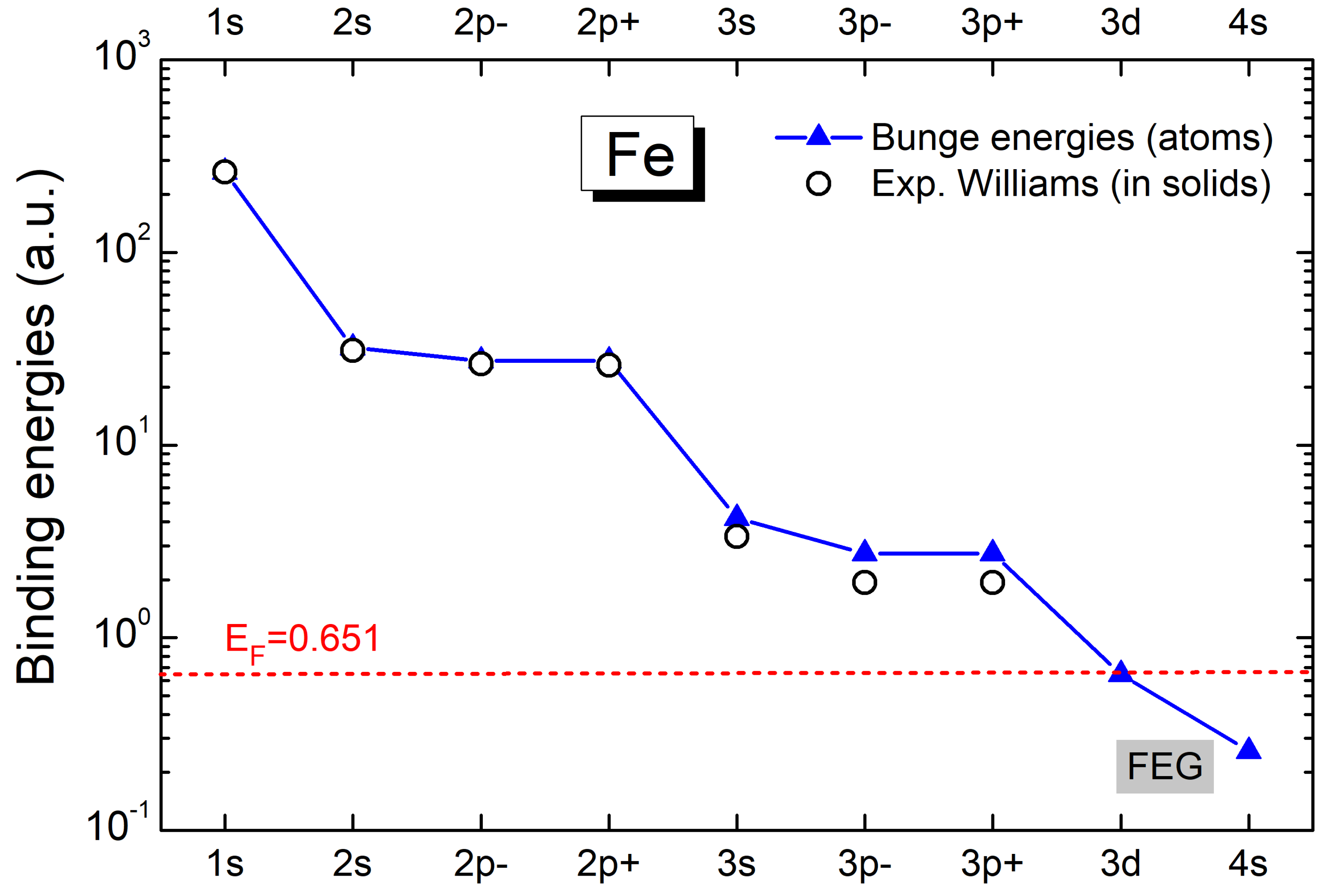

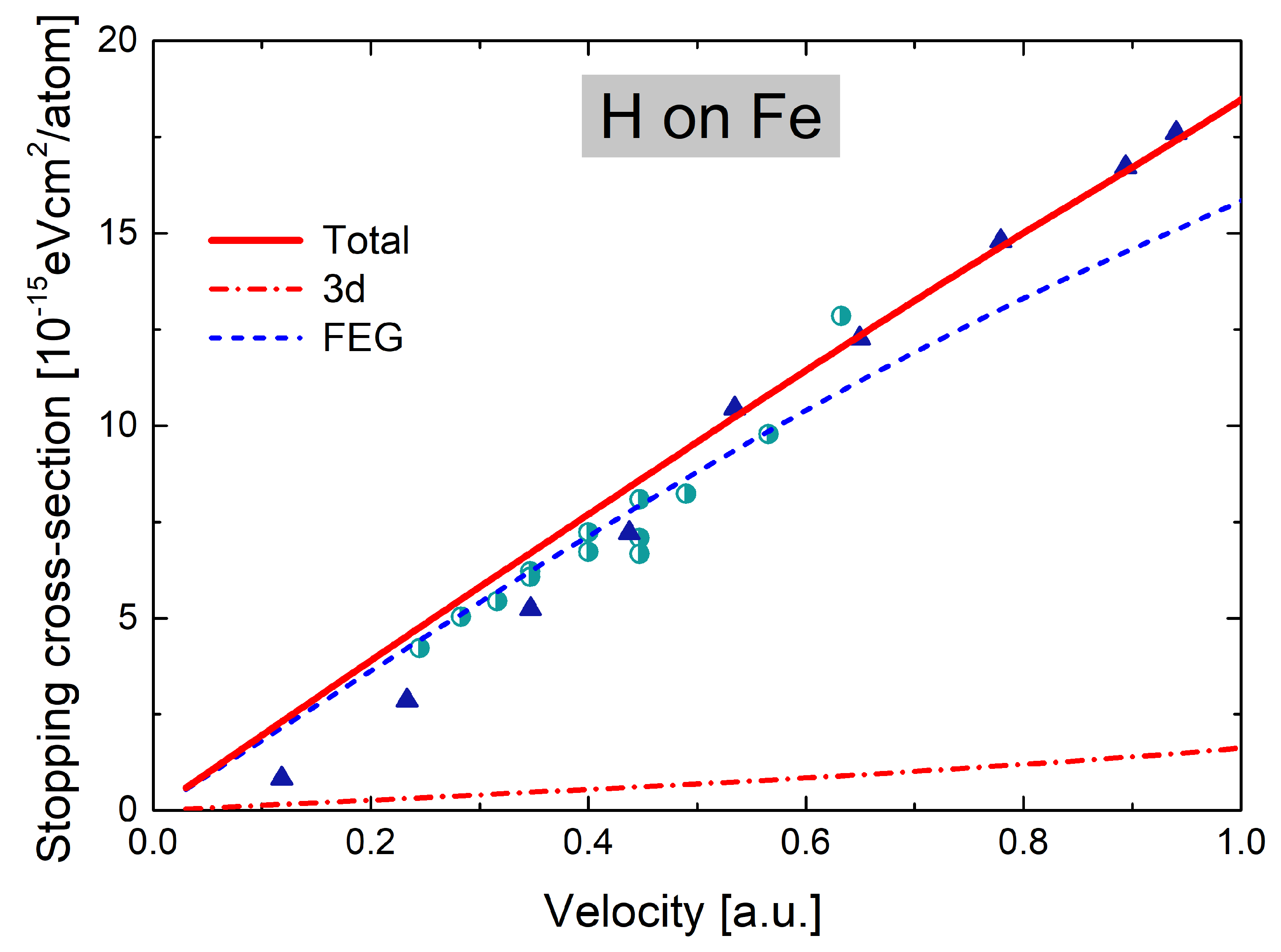

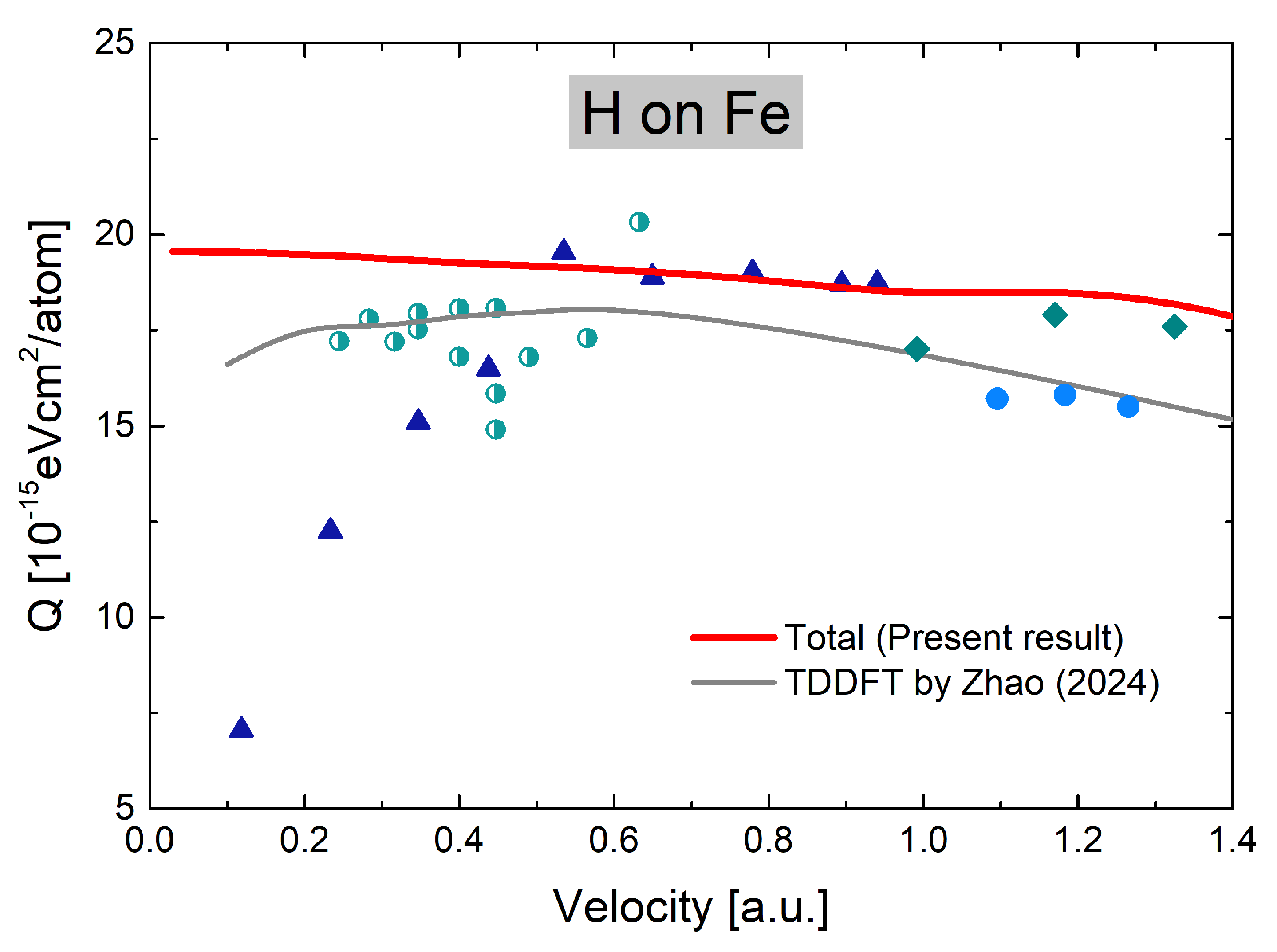

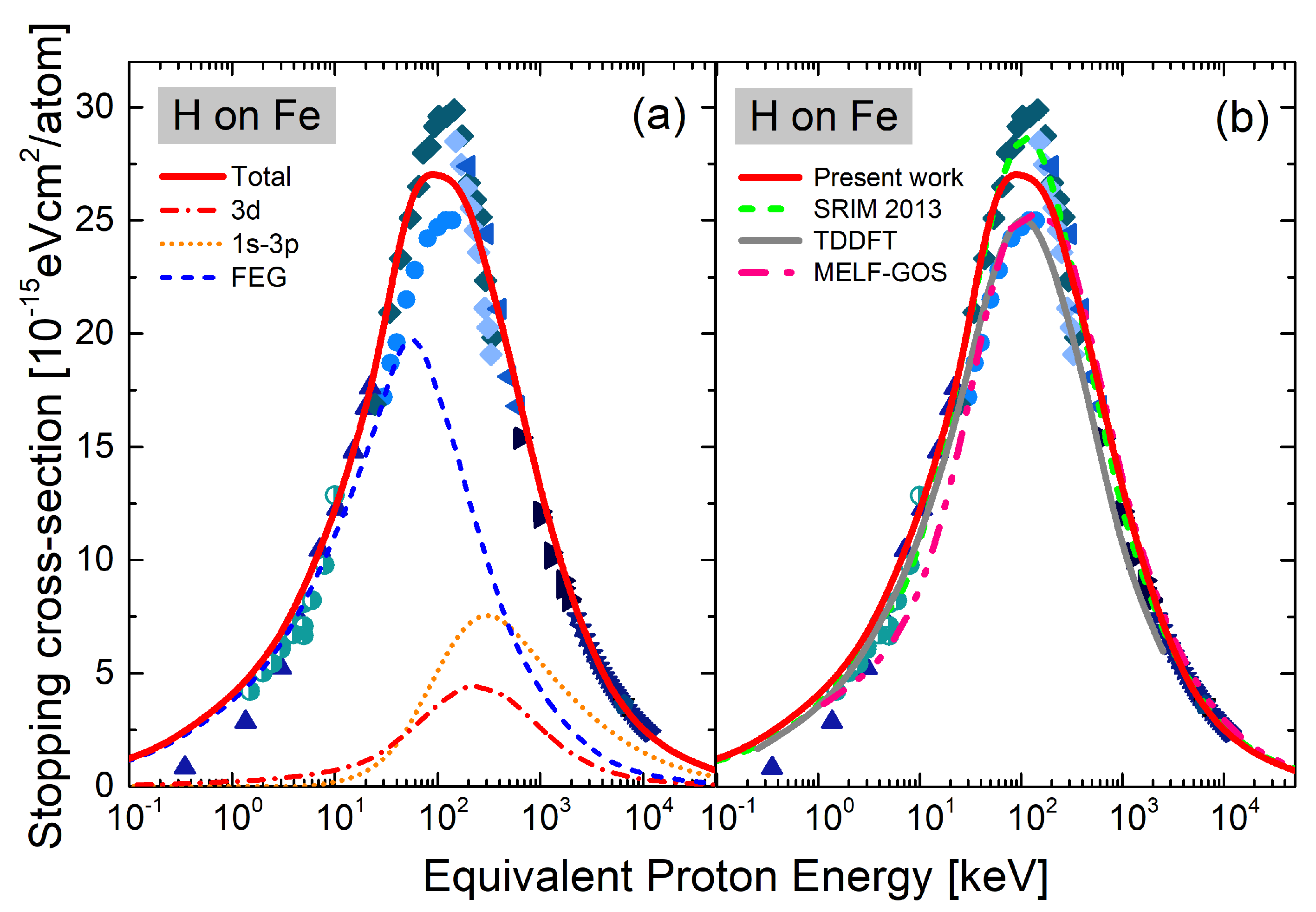

08 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Models

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Funding

References

- Montanari, C.; Dimitriou, P.; Marian, L.; Mendez, A.; Peralta, J.; Bivort-Haiek, F. The IAEA electronic stopping power database: Modernization, review, and analysis of the existing experimental data. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 2024, 551, 165336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethe, H. Zur Theorie des Durchgangs schneller Korpuskularstrahlen durch Materie. Annalen der Physik 1930, 397, 325–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, N. The penetration of atomic particles through matter; Munksgaard Copenhagen, 1948.

- Sigmund, P.; Schinner, A. Progress in understanding heavy-ion stopping. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 2016, 382, 15–25, The 21st International workshop on Inelastic Ion Surface Collisions (IISC-21). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashcroft, N.W.; Mermin, N.D. Solid State Physics; Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1976.

- Ritchie, R.H. Interaction of Charged Particles with a Degenerate Fermi-Dirac Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. 1959, 114, 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, T.L.; Ritchie, R.H. Energy losses by slow ions and atoms to electronic excitation in solids. Phys. Rev. B 1977, 16, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echenique, P.M.; Flores, F.; Ritchie, R.H. , Dynamic Screening of Ions in Condensed Matter; Academic Press, 1990; Vol. 43, Solid State Physics, pp. 229–308. [CrossRef]

- Quashie, E.E.; Saha, B.C.; Correa, A.A. Electronic band structure effects in the stopping of protons in copper. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 155403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.K.; Guo, X.; Xue, J.M.; Zhang, F.S. Electronic stopping power of protons in platinum: Direct valence and inner-shell-electron excitations from first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. A 2023, 107, 052814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.D.; Mao, F.; Deng, H. Electronic stopping of iron for protons and helium ions from first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. A 2024, 109, 032807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matias, F.; Grande, P.L.; Koval, N.E.; Shorto, J.M.B.; Silva, T.F.; Arista, N.R. Deeper-band electron contributions to stopping power of silicon for low-energy ions. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2024, 161, 064310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Trujillo, R.; Sabin, J.; Deumens, E.; Öhrn, Y. Dynamical Processes in Stopping Cross Sections. In Theory of the Interaction of Swift Ions with Matter. Part 1; Academic Press, 2004; Vol. 45, Advances in Quantum Chemistry, pp. 99–124. [CrossRef]

- Schiwietz, G.; Grande, P. Stopping of protons – Improved accuracy of the UCA model. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 2012, 273, 1–5, 20th International Conference on Ion Beam Analysis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinner, A.; Sigmund, P. Expanded PASS stopping code. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 2019, 460, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcocer-Ávila, M.E.; Quinto, M.A.; Monti, J.M.; Rivarola, R.D.; Champion, C. Proton transport modeling in a realistic biological environment by using TILDA-V. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 14030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abril, I.; Garcia-Molina, R.; Denton, C.D.; Pérez-Pérez, F.J.; Arista, N.R. Dielectric description of wakes and stopping powers in solids. Phys. Rev. A 1998, 58, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, C.C.; Miraglia, J.E. The Dielectric Formalism for Inelastic Processes in High-Energy Ion–Matter Collisions. In Advances in Quantum Chemistry: Theory of Heavy Ion Collision Physics in Hadron Therapy; Belkic, D., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, 2013; Vol. 2, chapter 7, pp. 165–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vera, P.; Abril, I.; Garcia-Molina, R. Energy Spectra of Protons and Generated Secondary Electrons around the Bragg Peak in Materials of Interest in Proton Therapy. Radiation Research 2018, 190, 282–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindhard, J. On the properties of a gas of charged particles. K. Dan. Vidensk. Selsk. Mat.-Fys. Medd. 1954, 28, 0. [Google Scholar]

- Mermin, N.D. Lindhard Dielectric Function in the Relaxation-Time Approximation. Phys. Rev. B 1970, 1, 2362–2363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, P.; Krist, T. Electronic stopping cross sections for 30–300 keV protons in materials with 23≤Z2≤30. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research 1982, 194, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, P.; Krist, T. Stopping ratios for 30–330 keV ions with 1≤Z1≤5. Journal of Applied Physics 1982, 53, 7343–7349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, W.; Mueller, R.M. Electronic Stopping Cross Sections for 1H and 4He Particles in Cr, Mn, Co, Ni, and Cu at Energies near 100 keV. Phys. Rev. 1969, 187, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baglin, J.; Chu, W. Stopping power of 0.3–2.6 MeV 4He ions in Fe and Ni. Nuclear Instruments and Methods 1978, 149, 695–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, W.K.; Powers, D. Alpha-Particle Stopping Cross Section in Solids from 400 keV to 2 MeV. Phys. Rev. 1969, 187, 478–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantero, E.D.; Lantschner, G.H.; Eckardt, J.C.; Arista, N.R. Velocity dependence of the energy loss of very slow proton and deuteron beams in Cu and Ag. Phys. Rev. A 2009, 80, 032904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markin, S.N.; Primetzhofer, D.; Prusa, S.; Brunmayr, M.; Kowarik, G.; Aumayr, F.; Bauer, P. Electronic interaction of very slow light ions in Au: Electronic stopping and electron emission. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 78, 195122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorge, E. Valdés, P.V.; Esaulov, V.A. Energy losses of slow ions traveling through crystalline solids and scattered on crystalline surfaces. Radiation Effects and Defects in Solids 2016, 171, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goebl, D.; Roth, D.; Bauer, P. Role of d electrons in electronic stopping of slow light ions. Physical Review A - Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics 2013, 87, 062903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, J.P.; Mendez, A.M.P.; Mitnik, D.M.; Montanari, C.C. The d-electron contribution to the stopping power of transition metals. Submitted to Phys. Rev. A, in progress. [CrossRef]

- IAEA. Electronic Stopping Power of Matter for Ions, https://www-nds.iaea.org/stopping/, 1928–2024.

- Shams-Latifi, J.; Pitthan, E.; Primetzhofer, D. Experimental electronic stopping cross-section of EUROFER97 for slow protons, deuterons and helium ions. Radiation Physics and Chemistry 2024, 224, 112073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fermi, E.; Teller, E. The Capture of Negative Mesotrons in Matter. Phys. Rev. 1947, 72, 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, C.C.; Miraglia, J.E. Low- and intermediate-energy stopping power of protons and antiprotons in solid targets. Phys. Rev. A 2017, 96, 012707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, I.; Bergara, A. A model for the velocity-dependent screening. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 1996, 115, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peralta, J.P.; Fiori, M.; Mendez, A.M.P.; Montanari, C.C. Stopping-power calculations and the Levine-Mermin dielectric function for inner shells. Phys. Rev. A 2022, 105, 062814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunge, C.; Barrientos, J.; Bunge, A. Roothaan-Hartree-Fock Ground-State Atomic Wave Functions: Slater-Type Orbital Expansions and Expectation Values for Z = 2–54. Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables 1993, 53, 113–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, M.R.; Levy, H., I. Simple Analytic Expression for General Two-Center Coulomb Integrals. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1969, 50, 2938–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, W.S.M.; Glantschnig, K.; Ambrosch-Draxl, C. Optical Constants and Inelastic Electron-Scattering Data for 17 Elemental Metals. Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data 2009, 38, 1013–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.P. , Electron Binding Energies of the Elements; CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, CRC Press, 2014; chapter 10, pp. 200–205.

- Arkhipov, E.P.; Gott, Y.V. Soviet Journal of Experimental and Theoretical Physics 1969, 29, 615. 29.

- de Vera, P.; Abril, I.; Garcia-Molina, R. Electronic cross section, stopping power and energy-loss straggling of metals for swift protons, alpha particles and electrons. Frontiers in Materials 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, J.F. SRIM, http://www.srim.org/, 2013.

- Bader, M.; Pixley, R.E.; Mozer, F.S.; Whaling, W. Stopping Cross Section of Solids for Protons, 50–600 KeV. Phys. Rev. 1956, 103, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwari, R.; Shiomi, N.; Shirai, S.; Uemura, U. Stopping powers of Al, Ti, Fe, Cu, Mo, Ag, Sn, Ta and Au for 7.2 MeV protons. Physics Letters A 1974, 48, 96–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiwari, R.; Shiomi, N.; Sakamoto, N. Stopping powers of Be, Al, Ti, V, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Mo, Rh, Ag, Sn, Ta, Pt and Au for 6.75 MeV protons. Physics Letters A 1979, 75, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, H.H.; Hanke, C.C.; Simonsen, H.; Sørensen, H.; Vajda, P. Stopping Power of the Elements Z=20 Through Z=30 for 5–12-MeV Protons and Deuterons. Phys. Rev. 1968, 175, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiedeakatemia, S. Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae: Physica. Series A.. VI; Annales Academiae Scientiarum Fennicae: Physica, Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Shiomi-Tsuda, N.; Sakamoto, N.; Ishiwari, R. Stopping powers of Be, Al, Ti, V, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, Mo, Rh, Ag, Sn, Ta, Pt and Au for 13 MeV deuterons. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 1994, 93, 391–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).