Submitted:

04 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Pathogenesis of ER Stress and the UPR

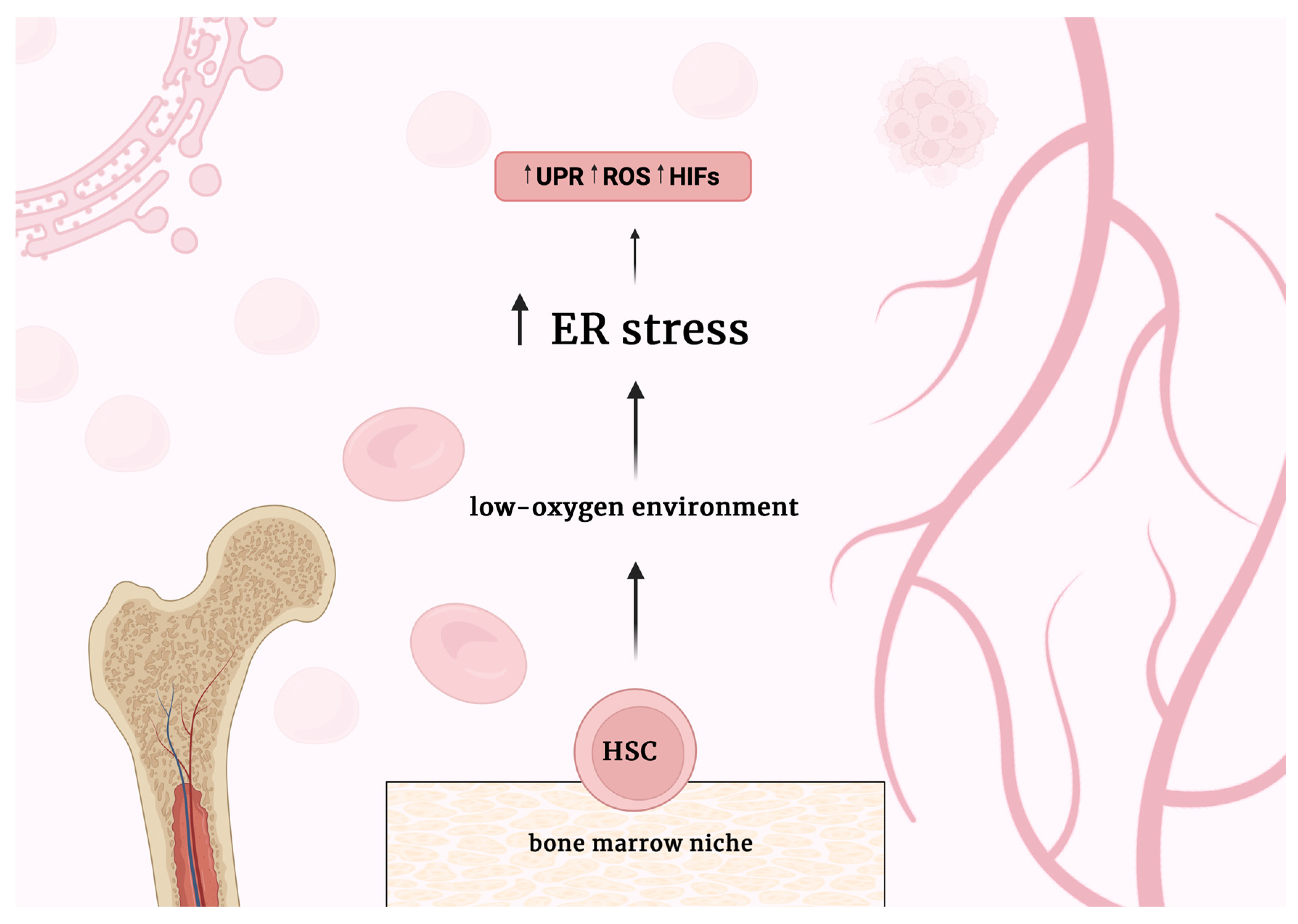

2.1. ER Stress and the UPR in HSCs

3. Pathogenesis of ER Stress and the UPR in AML

4. Prognostic Implications of ER Stress Markers in AML

5. Direct Targeting of ER Stress in AML

6. Effect of New Therapy on ER Stress in AML

6.1. JUN Inhibition in AML

6.2. NMT Inhibition in AML

6.3. Proteasome Inhibition in AML

6.4. Malachite Green-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) in AML

6.5. Staphylococcal Enterotoxins in AML

6.6. Camalexin in AML

6.7. PLK4 Inhibition in AML

6.8. Venetoclax in AML

6.9. PAD Inhibition in AML

6.10. G protein–Coupled Estrogen Receptor-1 (GPER) in AML

6.11. N-acetyltransferase 10 (NAT10) Inhibition in AML

6.13. Lysine Demethylase 6A (KDM6A) in AML

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khoury, J.D.; Solary, E.; Abla, O.; Akkari, Y.; Alaggio, R.; Apperley, J.F.; Bejar, R.; Berti, E.; Busque, L.; Chan, J.K.C.; et al. The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia 2022, 36, 1703–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pelcovits, A.; Niroula, R. Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Review. R I Med J (2013) 2020, 103, 38–40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Short, N.J.; Zhou, S.; Fu, C.; Berry, D.A.; Walter, R.B.; Freeman, S.D.; Hourigan, C.S.; Huang, X.; Nogueras Gonzalez, G.; Hwang, H.; et al. Association of Measurable Residual Disease With Survival Outcomes in Patients With Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Oncology 2020, 6, 1890–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachter, F.; Pikman, Y. Pathophysiology of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Acta Haematol 2024, 147, 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shallis, R.M.; Wang, R.; Davidoff, A.; Ma, X.; Zeidan, A.M. Epidemiology of Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Recent Progress and Enduring Challenges. Blood Reviews 2019, 36, 70–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebestreit, K.; Gröttrup, S.; Emden, D.; Veerkamp, J.; Ruckert, C.; Klein, H.-U.; Müller-Tidow, C.; Dugas, M. Leukemia Gene Atlas – A Public Platform for Integrative Exploration of Genome-Wide Molecular Data. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e39148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokota, S.; Kiyoi, H.; Nakao, M.; Iwai, T.; Misawa, S.; Okuda, T.; Sonoda, Y.; Abe, T.; Kahsima, K.; Matsuo, Y.; et al. Internal Tandem Duplication of the FLT3 Gene Is Preferentially Seen in Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndrome among Various Hematological Malignancies. A Study on a Large Series of Patients and Cell Lines. Leukemia 1997, 11, 1605–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estey, E.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Döhner, H. Distinguishing AML from MDS: A Fixed Blast Percentage May No Longer Be Optimal. Blood 2022, 139, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberg, O.K.; Porwit, A.; Orazi, A.; Hasserjian, R.P.; Foucar, K.; Duncavage, E.J.; Arber, D.A. The International Consensus Classification of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Virchows Arch 2023, 482, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desai, P.; Mencia-Trinchant, N.; Savenkov, O.; Simon, M.S.; Cheang, G.; Lee, S.; Samuel, M.; Ritchie, E.K.; Guzman, M.L.; Ballman, K.V.; et al. Somatic Mutations Precede Acute Myeloid Leukemia Years before Diagnosis. Nat Med 2018, 24, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmani, M.; Aust, M.M.; Hawkins, E.; Parker, R.E.; Ross, M.; Kmieciak, M.; Reshko, L.B.; Rizzo, K.A.; Dumur, C.I.; Ferreira-Gonzalez, A.; et al. Co-Administration of the mTORC1/TORC2 Inhibitor INK128 and the Bcl-2/Bcl-xL Antagonist ABT-737 Kills Human Myeloid Leukemia Cells through Mcl-1 down-Regulation and AKT Inactivation. Haematologica 2015, 100, 1553–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, L.; Wang, H.; Miao, Z.; Yu, Y.; Gai, D.; Zhang, G.; Ge, L.; Shen, X. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Related Signature Predicts Prognosis and Immune Infiltration Analysis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Hematology 2023, 28, 2246268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philippe, C.; Jaud, M.; Féral, K.; Gay, A.; Van Den Berghe, L.; Farce, M.; Bousquet, M.; Pyronnet, S.; Mazzolini, L.; Rouault-Pierre, K.; et al. Pivotal Role of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Related XBP1s/miR-22/SIRT1 Axis in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Apoptosis and Response to Chemotherapy. Leukemia 2024, 38, 1764–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urra, H.; Dufey, E.; Avril, T.; Chevet, E.; Hetz, C. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress and the Hallmarks of Cancer. Trends Cancer 2016, 2, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beilankouhi, E.A.V.; Sajadi, M.A.; Alipourfard, I.; Hassani, P.; Valilo, M.; Safaralizadeh, R. Role of the ER-Induced UPR Pathway, Apoptosis, and Autophagy in Colorectal Cancer. Pathology - Research and Practice 2023, 248, 154706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Féral, K.; Jaud, M.; Philippe, C.; Di Bella, D.; Pyronnet, S.; Rouault-Pierre, K.; Mazzolini, L.; Touriol, C. ER Stress and Unfolded Protein Response in Leukemia: Friend, Foe, or Both? Biomolecules 2021, 11, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śniegocka, M.; Liccardo, F.; Fazi, F.; Masciarelli, S. Understanding ER Homeostasis and the UPR to Enhance Treatment Efficacy of Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Drug Resist Updat 2022, 64, 100853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panahi, M.; Hase, Y.; Gallart-Palau, X.; Mitra, S.; Watanabe, A.; Low, R.C.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sepulveda-Falla, D.; Hainsworth, A.H.; Ihara, M.; et al. ER Stress Induced Immunopathology Involving Complement in CADASIL: Implications for Therapeutics. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2023, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayalalitha, R.; Archita, T.; Juanitaa, G.R.; Jayasuriya, R.; Amin, K.N.; Ramkumar, K.M. Role of Long Non-Coding RNA in Regulating ER Stress Response to the Progression of Diabetic Complications. Curr Gene Ther 2023, 23, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doron, B.; Abdelhamed, S.; Butler, J.T.; Hashmi, S.K.; Horton, T.M.; Kurre, P. Transmissible ER Stress Reconfigures the AML Bone Marrow Compartment. Leukemia 2019, 33, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Yang, N.; Li, Y.; Huang, K.; Jiang, X.; Liu, F.; Yu, Z.; Chen, J.; Lai, J.; Du, J.; et al. Metformin Sensitizes AML Cells to Venetoclax through Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress—CHOP Pathway. British Journal of Haematology 2023, 202, 971–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, F.; Qu, J.; Lin, D.; Feng, K.; Tan, M.; Liao, H.; Zeng, L.; Xiong, Q.; Huang, J.; Chen, W. Reduced Proteolipid Protein 2 Promotes Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Related Apoptosis and Increases Drug Sensitivity in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Mol Biol Rep 2023, 51, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Zhou, J.; Jiao, C.; Ge, J. Bioinformatics Analysis of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Related Prognostic Model and Immune Cell Infiltration in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Hematology 2023, 28, 2221101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolland, H.; Ma, T.S.; Ramlee, S.; Ramadan, K.; Hammond, E.M. Links between the Unfolded Protein Response and the DNA Damage Response in Hypoxia: A Systematic Review. Biochemical Society Transactions 2021, 49, 1251–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.H.; Li, H.; Yasumura, D.; Cohen, H.R.; Zhang, C.; Panning, B.; Shokat, K.M.; Lavail, M.M.; Walter, P. IRE1 Signaling Affects Cell Fate during the Unfolded Protein Response. Science 2007, 318, 944–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blazanin, N.; Son, J.; Craig-Lucas, A.B.; John, C.L.; Breech, K.J.; Podolsky, M.A.; Glick, A.B. ER Stress and Distinct Outputs of the IRE1α RNase Control Proliferation and Senescence in Response to Oncogenic Ras. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114, 9900–9905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, J.S.; Shamu, C.E.; Walter, P. Transcriptional Induction of Genes Encoding Endoplasmic Reticulum Resident Proteins Requires a Transmembrane Protein Kinase. Cell 1993, 73, 1197–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Tirasophon, W.; Shen, X.; Michalak, M.; Prywes, R.; Okada, T.; Yoshida, H.; Mori, K.; Kaufman, R.J. IRE1-Mediated Unconventional mRNA Splicing and S2P-Mediated ATF6 Cleavage Merge to Regulate XBP1 in Signaling the Unfolded Protein Response. Genes Dev 2002, 16, 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemorry, A.; Harnoss, J.M.; Guttman, O.; Marsters, S.A.; Kőműves, L.G.; Lawrence, D.A.; Ashkenazi, A. Caspase-Mediated Cleavage of IRE1 Controls Apoptotic Cell Commitment during Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. eLife 2019, 8, e47084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozpedek, W.; Pytel, D.; Mucha, B.; Leszczynska, H.; Diehl, J.A.; Majsterek, I. The Role of the PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP Signaling Pathway in Tumor Progression During Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Current Molecular Medicine 16, 533–544. [CrossRef]

- Blais, J.D.; Filipenko, V.; Bi, M.; Harding, H.P.; Ron, D.; Koumenis, C.; Wouters, B.G.; Bell, J.C. Activating Transcription Factor 4 Is Translationally Regulated by Hypoxic Stress. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2004, 24, 7469–7482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishitoh, H. CHOP Is a Multifunctional Transcription Factor in the ER Stress Response. The Journal of Biochemistry 2012, 151, 217–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groenendyk, J.; Agellon, L.B.; Michalak, M. Chapter One - Calcium Signaling and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. In International Review of Cell and Molecular Biology; Marchi, S., Galluzzi, L., Eds.; Inter-Organellar Ca Signaling in Health and Disease - Part B; Academic Press, 2021; Vol. 363, pp. 1–20.

- Banerjee, T.; Grabon, A.; Taylor, M.; Teter, K. cAMP-Independent Activation of the Unfolded Protein Response by Cholera Toxin. Infection and Immunity 2021, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Mi, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Q.; Song, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, D.; Xing, J.; Hou, B.; Li, H.; et al. Dihydroartemisinin-Induced Unfolded Protein Response Feedback Attenuates Ferroptosis via PERK/ATF4/HSPA5 Pathway in Glioma Cells. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2019, 38, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.J.; McCulloch, E.A.; Till, J.E. Cytological Demonstration of the Clonal Nature of Spleen Colonies Derived from Transplanted Mouse Marrow Cells. 1963.

- Calvanese, V.; Nguyen, A.T.; Bolan, T.J.; Vavilina, A.; Su, T.; Lee, L.K.; Wang, Y.; Lay, F.D.; Magnusson, M.; Crooks, G.M.; et al. MLLT3 Governs Human Haematopoietic Stem-Cell Self-Renewal and Engraftment. Nature 2019, 576, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouault-Pierre, K.; Lopez-Onieva, L.; Foster, K.; Anjos-Afonso, F.; Lamrissi-Garcia, I.; Serrano-Sanchez, M.; Mitter, R.; Ivanovic, Z.; de Verneuil, H.; Gribben, J.; et al. HIF-2α Protects Human Hematopoietic Stem/Progenitors and Acute Myeloid Leukemic Cells from Apoptosis Induced by Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Cell Stem Cell 2013, 13, 549–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, T.H.; Carroll, K.S. Redox Regulation of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Signaling through Cysteine Oxidation. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 9954–9965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Zhao, M.; Jin, X.; Ney, G.; Yang, K.B.; Peng, F.; Cao, J.; Iwawaki, T.; Del Valle, J.; Chen, X.; et al. Adaptive Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Signalling via IRE1α–XBP1 Preserves Self-Renewal of Haematopoietic and Pre-Leukaemic Stem Cells. Nat Cell Biol 2019, 21, 328–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Galen, P.; Kreso, A.; Mbong, N.; Kent, D.G.; Fitzmaurice, T.; Chambers, J.E.; Xie, S.; Laurenti, E.; Hermans, K.; Eppert, K.; et al. The Unfolded Protein Response Governs Integrity of the Haematopoietic Stem-Cell Pool during Stress. Nature 2014, 510, 268–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, A.; Xu, S.; Li, Q.; Zhu, C.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Hao, S.; Dong, F.; Cheng, H.; Cheng, T.; et al. Interlukin-4 Weakens Resistance to Stress Injury and Megakaryocytic Differentiation of Hematopoietic Stem Cells by Inhibiting Psmd13 Expression. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 14253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Pi, W.; Sivaprakasam, S.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, M.; Chen, J.; Makala, L.; Lu, C.; Wu, J.; Teng, Y.; et al. UFBP1, a Key Component of the Ufm1 Conjugation System, Is Essential for Ufmylation-Mediated Regulation of Erythroid Development. PLOS Genetics 2015, 11, e1005643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Chen, J.; Sivaprakasam, S.; Gurav, A.; Pi, W.; Makala, L.; Wu, J.; et al. RCAD/Ufl1, a Ufm1 E3 Ligase, Is Essential for Hematopoietic Stem Cell Function and Murine Hematopoiesis. Cell Death Differ 2015, 22, 1922–1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaquet, T.; Preisinger, C.; Bütow, M.; Tillmann, S.; Chatain, N.; Huber, M.; Koschmieder, S.; Kirschner, M.; Jost, E.; Brümmendorf, T.H.; et al. The Unfolded Protein Response Mediates Resistance in AML and Its Therapeutic Targeting Enhances TKI Induced Cell Death in FLT3-ITD + AML. Blood 2021, 138, 2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Li, J.; Du, J.; Jiang, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; He, Q.; Liang, H.; Fang, P.; Zhan, H.; et al. HMGCS1 Drives Drug-Resistance in Acute Myeloid Leukemia through Endoplasmic Reticulum-UPR-Mitochondria Axis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 137, 111378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, J.; Zeng, Z.; Konopleva, M.; Wilson, W.R. Targeting Hypoxia in the Leukemia Microenvironment. International Journal of Hematologic Oncology 2013, 2, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huiting, L.N.; Samaha, Y.; Zhang, G.L.; Roderick, J.E.; Li, B.; Anderson, N.M.; Wang, Y.W.; Wang, L.; Laroche, F.J.F.; Choi, J.W.; et al. UFD1 Contributes to MYC-Mediated Leukemia Aggressiveness through Suppression of the Proapoptotic Unfolded Protein Response. Leukemia 2018, 32, 2339–2351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvatori, B.; Iosue, I.; Djodji Damas, N.; Mangiavacchi, A.; Chiaretti, S.; Messina, M.; Padula, F.; Guarini, A.; Bozzoni, I.; Fazi, F.; et al. Critical Role of C-Myc in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Involving Direct Regulation of miR-26a and Histone Methyltransferase EZH2. Genes & Cancer 2011, 2, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.; Stolz, J.; Kohl, S.; Chiang, W.-C.; Lin, J.H. Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Human Photoreceptor Diseases. Brain Research 2016, 1648, 538–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turos-Cabal, M.; Sánchez-Sánchez, A.M.; Puente-Moncada, N.; Herrera, F.; Antolin, I.; Rodríguez, C.; Martín, V. FLT3-ITD Regulation of the Endoplasmic Reticulum Functions in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Hematol Oncol 2024, 42, e3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schardt, J.A.; Mueller, B.U.; Pabst, T. Chapter Thirteen - Activation of the Unfolded Protein Response in Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia. In Methods in Enzymology; Conn, P.M., Ed.; The Unfolded Protein Response and Cellular Stress, Part A; Academic Press, 2011; Vol. 489, pp. 227–243.

- Sun, H.; Lin, D.-C.; Guo, X.; Masouleh, B.K.; Gery, S.; Cao, Q.; Alkan, S.; Ikezoe, T.; Akiba, C.; Paquette, R.; et al. Inhibition of IRE1α-Driven pro-Survival Pathways Is a Promising Therapeutic Application in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 18736–18749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haefliger, S.; Klebig, C.; Schaubitzer, K.; Schardt, J.; Timchenko, N.; Mueller, B.U.; Pabst, T. Protein Disulfide Isomerase Blocks CEBPA Translation and Is Up-Regulated during the Unfolded Protein Response in AML. Blood 2011, 117, 5931–5940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schauner, R.; Cress, J.; Hong, C.; Wald, D.; Ramakrishnan, P. Single Cell and Bulk RNA Expression Analyses Identify Enhanced Hexosamine Biosynthetic Pathway and O-GlcNAcylation in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Blasts and Stem Cells. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perl, A.E.; Larson, R.A.; Podoltsev, N.A.; Strickland, S.; Wang, E.S.; Atallah, E.; Schiller, G.J.; Martinelli, G.; Neubauer, A.; Sierra, J.; et al. Follow-up of Patients with R/R FLT3-Mutation-Positive AML Treated with Gilteritinib in the Phase 3 ADMIRAL Trial. Blood 2022, 139, 3366–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erba, H.P.; Montesinos, P.; Kim, H.-J.; Patkowska, E.; Vrhovac, R.; Žák, P.; Wang, P.-N.; Mitov, T.; Hanyok, J.; Kamel, Y.M.; et al. Quizartinib plus Chemotherapy in Newly Diagnosed Patients with FLT3-Internal-Tandem-Duplication-Positive Acute Myeloid Leukaemia (QuANTUM-First): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1571–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiNardo, C.D.; Stein, A.S.; Stein, E.M.; Fathi, A.T.; Frankfurt, O.; Schuh, A.C.; Döhner, H.; Martinelli, G.; Patel, P.A.; Raffoux, E.; et al. Mutant Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 1 Inhibitor Ivosidenib in Combination With Azacitidine for Newly Diagnosed Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2021, 39, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathi, A.T.; Kim, H.T.; Soiffer, R.J.; Levis, M.J.; Li, S.; Kim, A.S.; Mims, A.S.; DeFilipp, Z.; El-Jawahri, A.; McAfee, S.L.; et al. Enasidenib as Maintenance Following Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for IDH2-Mutated Myeloid Malignancies. Blood Advances 2022, 6, 5857–5865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, M.; Wang, M.; Liu, M.; Fu, S.; Lin, Y.; Huo, Y.; Yu, J.; Yu, X.; Wang, C.; Xiao, H.; et al. C/EBPα-P30 Confers AML Cell Susceptibility to the Terminal Unfolded Protein Response and Resistance to Venetoclax by Activating DDIT3 Transcription. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2024, 43, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, F.W.; Qiu, Y.; Brown, B.D.; Gerbing, R.B.; Leonti, A.R.; Ries, R.E.; Gamis, A.S.; Aplenc, R.; Kolb, E.A.; Alonzo, T.A.; et al. Valosin-Containing Protein (VCP/P97) Is Prognostically Unfavorable in Pediatric AML, and Negatively Correlates with Unfolded Protein Response Proteins IRE1 and GRP78: A Report from the Children’s Oncology Group. PROTEOMICS – Clinical Applications 2023, 17, 2200109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mimura, N.; Fulciniti, M.; Gorgun, G.; Tai, Y.-T.; Cirstea, D.; Santo, L.; Hu, Y.; Fabre, C.; Minami, J.; Ohguchi, H.; et al. Blockade of XBP1 Splicing by Inhibition of IRE1α Is a Promising Therapeutic Option in Multiple Myeloma. Blood 2012, 119, 5772–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.H.; Cai, M.; Deng, J.; Yu, P.; Liang, H.; Yang, F. Anticancer Function and ROS-Mediated Multi-Targeting Anticancer Mechanisms of Copper (II) 2-Hydroxy-1-Naphthaldehyde Complexes. Molecules 2019, 24, 2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatokova, Z.; Evinova, A.; Racay, P. STF-083010 an Inhibitor of IRE1α Endonuclease Activity Affects Mitochondrial Respiration and Generation of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential. Toxicol In Vitro 2023, 92, 105652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandey, S.; Djibo, R.; Darracq, A.; Calendo, G.; Zhang, H.; Henry, R.A.; Andrews, A.J.; Baylin, S.B.; Madzo, J.; Najmanovich, R.; et al. Selective CDK9 Inhibition by Natural Compound Toyocamycin in Cancer Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14, 3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Huo, Y.; Zhou, S.; Guo, J.; Ma, X.; Li, T.; Fan, C.; Wang, L. Cancer Cell-Intrinsic XBP1 Drives Immunosuppressive Reprogramming of Intratumoral Myeloid Cells by Promoting Cholesterol Production. Cell Metab 2022, 34, 2018–2035.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebert, M.; Bartoszewska, S.; Opalinski, L.; Collawn, J.F.; Bartoszewski, R. IRE1-Mediated Degradation of Pre-miR-301a Promotes Apoptosis through Upregulation of GADD45A. Cell Commun Signal 2023, 21, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Masouleh, B.K.; Gery, S.; Cao, Q.; Alkan, S.; Ikezoe, T.; Akiba, C.; Paquette, R.; Chien, W.; Müller-Tidow, C.; et al. Abstract 510: Inhibition of IRE1α-Driven pro-Survival Pathways Is a Promising Therapeutic Application in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Cancer Research 2014, 74, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creedican, S.; Robinson, C.M.; Mnich, K.; Islam, M.N.; Szegezdi, E.; Clifford, R.; Krawczyk, J.; Patterson, J.B.; FitzGerald, S.P.; Summers, M.; et al. Inhibition of IRE1α RNase Activity Sensitizes Patient-Derived Acute Myeloid Leukaemia Cells to Proteasome Inhibitors. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2022, 26, 4629–4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Martinez, E.; Di Marcantonio, D.; Solanki-Patel, N.; Aghayev, T.; Peri, S.; Ferraro, F.; Skorski, T.; Scholl, C.; Fröhling, S.; et al. JUN Is a Key Transcriptional Regulator of the Unfolded Protein Response in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Leukemia 2017, 31, 1196–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamma, J.M.; Liu, Q.; Beauchamp, E.; Iyer, A.; Yap, M.C.; Zak, Z.; Ekstrom, C.; Pain, R.; Kostiuk, M.A.; Mackey, J.R.; et al. Zelenirstat Inhibits N-Myristoyltransferases to Disrupt Src Family Kinase Signaling and Oxidative Phosphorylation, Killing Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2024, OF1–OF12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Tao, Y.; Hu, K.; Lu, J. GRP78 Inhibitor HA15 Increases the Effect of Bortezomib on Eradicating Multiple Myeloma Cells through Triggering Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iaiza, A.; Mazzanti, G.; Goeman, F.; Cesaro, B.; Cortile, C.; Corleone, G.; Tito, C.; Liccardo, F.; De Angelis, L.; Petrozza, V.; et al. WTAP and m6A-Modified circRNAs Modulation during Stress Response in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Progenitor Cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liccardo, F.; Śniegocka, M.; Tito, C.; Iaiza, A.; Ottone, T.; Divona, M.; Travaglini, S.; Mattei, M.; Cicconi, R.; Miglietta, S.; et al. Retinoic Acid and Proteotoxic Stress Induce AML Cell Death Overcoming Stromal Cell Protection. Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 2023, 42, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çalişkan, M.; Bayrak, G.; Özlem Çalişkan, S. Anti-Leukemic Effect of Malachite Green-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy by Inducing ER Stress in HL-60 Cells. Medical Records 2024, 6, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turk, S.; Yanpar, H.; Baesmat, A.S.; Canli, S.D.; Cinar, O.E.; Malkan, U.Y.; Turk, C.; Haznedaroglu, I.C.; Ucar, G. Enterotoxins A and B Produced by Staphylococcus Aureus Increase Cell Proliferation, Invasion and Cytarabine Resistance in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cell Lines. Heliyon 2023, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pilatova, M.; Ivanova, L.; Kutschy, P.; Varinska, L.; Saxunova, L.; Repovska, M.; Sarissky, M.; Seliga, R.; Mirossay, L.; Mojzis, J. In Vitro Toxicity of Camalexin Derivatives in Human Cancer and Non-Cancer Cells. Toxicol In Vitro 2013, 27, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Wu, W.; Yao, S.; Han, X.; He, D.; He, J.; Zheng, G.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, Z.; et al. Camalexin Induces Apoptosis via the ROS-ER Stress-Mitochondrial Apoptosis Pathway in AML Cells. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2018, 2018, 7426950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Q.; Yu, Q.; Yang, N.; Xiao, Z.; Song, C.; Zhang, R.; Yang, S.; Liu, Z.; Deng, H. Therapeutic Potential of Targeting Polo-like Kinase 4. Eur J Med Chem 2024, 265, 116115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.L.; Anzola, J.V.; Davis, R.L.; Yoon, M.; Motamedi, A.; Kroll, A.; Seo, C.P.; Hsia, J.E.; Kim, S.K.; Mitchell, J.W.; et al. Cell Biology. Reversible Centriole Depletion with an Inhibitor of Polo-like Kinase 4. Science 2015, 348, 1155–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Zhong, L.; Chu, X.; Wan, P.; Liu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhou, Z.; Shao, X.; et al. Downregulation of Polo-like Kinase 4 Induces Cell Apoptosis and G2/M Arrest in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Pathol Res Pract 2023, 243, 154376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Y. Peptidylarginine Deiminases in Citrullination, Gene Regulation, Health and Pathogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013, 1829, 1126–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uysal-Onganer, P.; D’Alessio, S.; Mortoglou, M.; Kraev, I.; Lange, S. Peptidylarginine Deiminase Inhibitor Application, Using Cl-Amidine, PAD2, PAD3 and PAD4 Isozyme-Specific Inhibitors in Pancreatic Cancer Cells, Reveals Roles for PAD2 and PAD3 in Cancer Invasion and Modulation of Extracellular Vesicle Signatures. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-N.; Ma, Y.-N.; Jia, X.-Q.; Yao, Q.; Chen, J.-P.; Li, H. Inducement of ER Stress by PAD Inhibitor BB-Cl-Amidine to Effectively Kill AML Cells. Curr Med Sci 2022, 42, 958–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosini, G.; Natale, C.A.; Musi, E.; Garyantes, T.; Schwartz, G.K. The GPER Agonist LNS8801 Induces Mitotic Arrest and Apoptosis in Uveal Melanoma Cells. Cancer Res Commun 2023, 3, 540–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinković, G.; Koenis, D.S.; de Camp, L.; Jablonowski, R.; Graber, N.; de Waard, V.; de Vries, C.J.; Goncalves, I.; Nilsson, J.; Jovinge, S.; et al. S100A9 Links Inflammation and Repair in Myocardial Infarction. Circ Res 2020, 127, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, R.; Satilmis, H.; Vandewalle, N.; Verheye, E.; De Bruyne, E.; Menu, E.; De Beule, N.; De Becker, A.; Ates, G.; Massie, A.; et al. Targeting S100A9 Protein Affects mTOR-ER Stress Signaling and Increases Venetoclax Sensitivity in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood Cancer J 2023, 13, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, I.; Doepner, M.; Weissenrieder, J.; Majer, A.D.; Mercado, S.; Estell, A.; Natale, C.A.; Sung, P.J.; Foskett, J.K.; Carroll, M.P.; et al. LNS8801 Inhibits Acute Myeloid Leukemia by Inducing the Production of Reactive Oxygen Species and Activating the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Pathway. Cancer Res Commun 2023, 3, 1594–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Lu, Y.; Cao, J.; Lin, L.; Chen, X.; Zhou, Z.; Pu, J.; Chen, G.; Ma, X.; Deng, Q.; et al. N-Acetyltransferase NAT10 Controls Cell Fates via Connecting mRNA Cytidine Acetylation to Chromatin Signaling. Sci Adv 2024, 10, eadh9871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zi, J.; Han, Q.; Gu, S.; McGrath, M.; Kane, S.; Song, C.; Ge, Z. Targeting NAT10 Induces Apoptosis Associated With Enhancing Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in Acute Myeloid Leukemia Cells. Front Oncol 2020, 10, 598107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullazade, S.; Behrens, H.-M.; Krüger, S.; Haag, J.; Röcken, C. MDM2 Amplification Is Rare in Gastric Cancer. Virchows Arch 2023, 483, 795–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Deng, S.; Deng, M.; Shi, Y.; Zhong, M.; Ding, L.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Carter, B.Z.; Xu, B. Therapeutic Synergy of Triptolide and MDM2 Inhibitor against Acute Myeloid Leukemia through Modulation of P53-Dependent and -Independent Pathways. Exp Hematol Oncol 2022, 11, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Cui, J.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Xia, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, S.; Sun, S.; Shi, B.; et al. KDM6A-ARHGDIB Axis Blocks Metastasis of Bladder Cancer by Inhibiting Rac1. Mol Cancer 2021, 20, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay, S.K.; Bose, A.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Ghosh, S.; Bhowmik, S.; Samanta, S.K.; Bhattacharyya, M.; Sengupta, A. KDM6A Modulates Anti-Tumor Immune Response By Integrating Immunogenic Cell Death in Human Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood 2023, 142, 2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target | Compound Name | In combination | Current Status | Results |

| FTL3 | Gilteritinib | - | FDA-approved | FDA-approved Gilteritinib for treatment of adult patients who have relapsed or refractory AML with a FLT3 mutation based on ADMIRAL trial (NCT02421939) [56]. |

| Quizartinib | Cytarabine + anthracycline | FDA-approved | FDA-approved Quizartinib for treatment of adult patients with newly AML that is FLT3 ITD-positive baseod on QuANTUM-First trial (NCT02668653) [57]. | |

| Crenolanib | - | Phase II | Complete Response (CR)/CRi 14,3%, Partial Response (PR) 16,1%, Overall Response Ratio (ORR) 30.4%, safe, well tolerated. [NCT01657682]. | |

| IDH1 | Ivosidenib | Gilteritinib | Phase I | Data unpublished [NCT05756777]. |

| Ivosidenib | Azacitidine | Phase 1b/2 | ORR 78,3%, CR 60,9%, safe, well tolerated [58]. | |

|

IDH2 |

Enasidenib |

- |

Phase I | Two-year progression-free 69%, overall survival 74%, safe, well tolerate [59]. |

| Phase II | Data unpublished [NCT04203316] | |||

| Enasidenib | Gilteritinib | Phase I | Data unpublished [NCT05756777] | |

|

NPM1 |

Selinexor |

Homoharringtonine + daunorubicin + cytarabine or Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor + aclacinomycin + cytarabine | Phase III | Data unpublished [NCT05726110] |

| Revumenib | Azacitidine + venetoclax | Phase III | Data unpublished [NCT06652438] | |

| Eltanexor | Venetoclax | Phase I | Data unpublished [NCT06399640] | |

| Ziftomenib | - | Phase I/II | Data unpublished [NCT04067336] | |

| DS-1594b | Azacitidine + venetoclax or Cyclophosphamide + Dexamethasone + Vincristine + Rituximab | Phase I/II | Data unpublished [NCT04752163] | |

| BMF-219 | - | Phase I | Data unpublished [NCT05153330] |

| Target | Compound Name | In combination | Current Status | Results |

| JUN | shJUN-1 and shJUN-2 knockdown | - | Preclinical phase | Inhibition of XBP1 or ATF4 via shRNA leads to apoptosis in AML cells and significantly prolongs disease latency in vivo, linking reduced survival from JUN inhibition to decreased pro-survival UPR signaling [70]. |

| NMT | Zelenirstat | - | Preclinical phase | Zelenirstat was well tolerated in vivo and caused the inhibition of AML cell lines [71]. |

| Proteasome | MKC8866 | Btz or carfilzomib | Preclinical phase | MKC8866, in combination with proteasome inhibitors, significantly reduces XBP1s levels and increases cell death in AML cell lines and patient-derived AML cells [69]. |

| Btz | - | Phase I | Data unpublished [NCT00077467]. | |

| Retinoic acid | Btz and arsenic trioxide | Preclinical phase | The combination exhibits strong cytotoxic effects on FLT3-ITD+ AML cell lines and primary blasts from patients due to disrupted ER homeostasis and increased oxidative stress [74]. | |

| PLK4 | Centrinone | - | Preclinical phase | Inhibition of PLK4 induces apoptosis, G2/M, and ER stress in AML cells [81] |

| BCL-2 | Venetoclax |

Metformin | Preclinical phase | The combination of metformin and venetoclax showed enhanced anti-leukemic activity with acceptable safety in patients with AML [21]. |

| PAD | BB-Cl-Amidine | - | Preclinical phase | BB-Cl-A activates the ER stress response and, due to this, effectively induces apoptosis in the AML cells [84]. |

| GPER | S100A9 siRNA knockdown | Venetoclax |

Preclinical phase | S100A9 knockdown significantly increases venetoclax sensitivity in AML cells [87]. |

| LNS8801 | - | Preclinical phase | LNS8801 induced AML cell death mainly through a caspase-dependent apoptosis pathway, inducing levels of ROS and ER stress response pathways, including IRE1α [88]. | |

| NAT10 | NAT10 shRNA knockdown | - | Preclinical phase | Targeting NAT10 promotes ER stress, triggers the UPR pathway, and activates the Bax/Bcl-2 axis in AML cells [90]. |

| MDM2 | Nutlin-3a | Triptolide | Preclinical phase | The combination exhibits a significant antileukemia effect through both p53-dependent and independent mechanisms, the latter involving the disruption of the MYC-ATF4 axis-mediated ER stress [92]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).