1. Introduction

Immune imprinting, first described by Thomas Francis, Jr. in the context of influenza over fifty years ago, refers to how the immune system's initial encounter with an antigen shapes future responses to future encounters with related antigens [

1,

2]. This concept has gained renewed interest in the study of emerging viral pathogens, including SARS-CoV-2 [

3,

4,

5,

6]. Research on variant-specific vaccines and successive epidemic waves has underscored the influence of initial immune priming on subsequent immune responses [

5]. Understanding this phenomenon is essential for optimizing vaccine strategies and anticipating immune dynamics in response to evolving viral threats. Imprinting has been shown to have both beneficial [

7,

8,

9] and detrimental effects [

8,

10]. Recent studies on SARS-CoV-2 variants show that initial immunisation with multiple doses of the prototype mRNA-1273 vaccine effectively primes the immune system, enhancing broad cross-neutralising antibody responses to subsequent Omicron-based boosters [

11,

12]. These findings underscore the critical role of early antigen exposure in shaping durable, broad-spectrum immunity against SARS-CoV-2.

Uganda confirmed its first COVID-19 case on 21 March 2020 [

13] and launched its vaccination campaign on 10 March 2021 after receiving 864,000 doses of the AstraZeneca vaccine. In August 2020, initial SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences from infection clusters in Uganda were identified as lineage A.23, which is characterized by spike protein mutations R1021, F157L, V367F, Q613H and P681R. These constituted 32% of viruses sequenced from June to August 2020, increasing to 50% from September to November 2020. By late October 2020, the A.23.1 variant with an additional spike mutation (P681R) emerged [

14], and from December 2020 to January 2021, 90% of identified genomes (102 of 113) belonged to the A.23.1 lineage [

15,

16]. Uganda’s Delta wave surged rapidly, rising from a daily average of 100 cases per day on May 18, 2021, to its peak at about 1800 cases per day by June 12, 2021, less than a month later. Between June and August 2021, the country recorded 2,328 COVID-19 deaths, representing over half of its total mortality at the time. The Omicron wave, from December 2021 to January 2022, progressed even faster, peaking within just two weeks of onset at over 1800 cases per day [

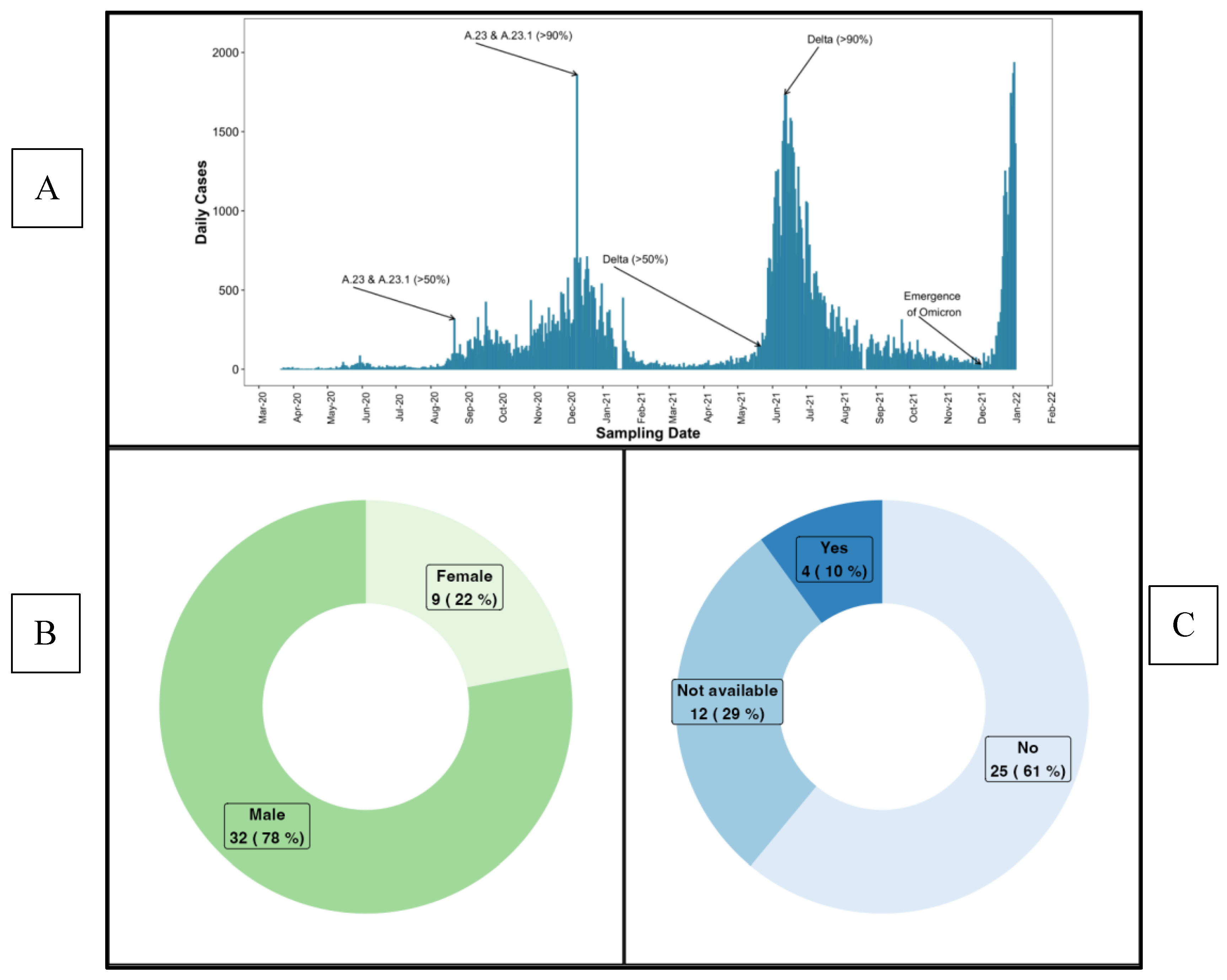

17], summarised in

Figure 1.

Our study uniquely investigated the A.23.1 variant, which constituted the primary antigenic exposure during Uganda's initial SARS-CoV-2 outbreak [

15]. A.23.1 is slightly distinct from the Wuhan-1 strain used in the vaccines administered in this population, owing to the presence of both V367F and Q613H mutations that increase its infectivity over the Wuhan-1 strain [

18]. This, combined with the NTD mutations, F157L and R102I, likely created a unique immunological imprint on the Ugandan population, with the long-term effects on subsequent immune responses to natural infection and vaccination remaining largely unexplored. We addressed this gap by analysing immune responses in a Ugandan cohort initially exposed to the A.23.1 variant, determining antibody binding in response to SARS-CoV-2 natural infection [

19] and vaccines [

20,

21,

22,

23] using Wuhan-1 strain antigens. The impact of A.23.1 on subsequent infections and vaccine responses remain uncertain, as does the specificity of serum-binding antibody titers in targeting A.23.1. It is also unclear how these antibody levels correlate with neutralisation of A.23.1 and other SARS-CoV-2 variants. Clarifying these interactions is essential for understanding the broader immune landscape shaped by natural infection and vaccination.

This study investigated how primary infection with the A.23.1 SARS-CoV-2 variant shaped antibody responses to both subsequent natural infections and vaccinations with the ancestral strain. By longitudinally tracking immune responses, we aimed to provide critical insights into the dynamics of antibody evolution in this context. Specifically, we assessed 1) how primary infection with the A.23.1 SARS-CoV-2 variant influenced the magnitude and breadth of serum-neutralising antibody responses, 2) the correlation between binding antibody levels and neutralising capacity against A.23.1 and other SARS-CoV-2 variants, and 3) the implications for immune assessments in this cohort. This is the first analysis of immune responses to a non-Wuhan-1 primary SARS-CoV-2 variant infection in an African population, and potentially has implications for tailored vaccine development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

This retrospective study, based on a well-characterised COVID-19 cohort [

19], included 41 participants monitored through subsequent variant epidemic waves (

Figure 1). SARS-CoV-2 positive participants were identified through rt-PCR testing as part of Uganda’s national border surveillance, focusing on truck drivers who were essential to maintaining economic activity during the nationwide lockdown. This cohort provided a unique opportunity to study viral transmission in at high-risk, mobile population. During that period, all PCR-positive cases were mandatorily isolated at Masaka and Entebbe Regional Referral Hospitals until a confirmed PCR-negative result. This strict isolation policy was implemented to prevent further transmission. Infection onset (Day 0) was estimated using the initial rt-PCR confirmation documented in hospital records, as all PCR-positive truck drivers were mandatorily hospitalised. During follow-up, eight participants were vaccinated with the AstraZeneca ChAdOx1-S COVID-19 vaccine. Aligned with the emergence of COVID-19 variants and daily case counts (

Figure 1A), most samples collected between July 2020 and October 2021 primarily reflect immune responses to infections driven by the A.23.1 and Delta variants, which predominated that period.

Of the 41 participants (median age: 29 years, IQR: 23–34), 78% were male. A majority (61%) were asymptomatic, 9.8% were symptomatic, and 29.3% had no symptom data (

Table 1,

Figure 1B and 1C). Over a 427-day follow-up period (median 182.2 days, IQR 91.5–277.2), 156 plasma samples were collected at four intervals: 0–9, 92–182, 183–273, and 274–427 days post-PCR confirmation of infection. The study was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the Uganda Virus Research Institute (GC/127/833) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS637ES). All participants provided written informed consent before their involvement.

2.2. Conventional in-House ELISA to Quantify Binding Antibody Concentrations

Anti-Spike-IgG antibodies were quantified using an optimised in-house ELISA protocol.[

24,

25] Briefly, 96-well flat-bottomed medium-binding plates (Greiner Bio-One, #655001) were coated with 50 μL of recombinant wild-type spike-protein or nucleoprotein antigen (R&D Systems, #10474-CV-01M, #10474-CV-01M) at 3.0 µg/mL and incubated overnight at 4°C. The following day, plates were washed with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and blocked for 1 hour at room temperature using PBS-T containing 1% BSA (Sigma, #A3803). Heat-inactivated plasma samples (56˚C for 30 minutes) were diluted 1:100 in PBS-T with 1% BSA and added in duplicate to the wells for a 2-hour incubation at room temperature. After incubation, plates were washed five times with PBS-T, followed by a one-hour incubation with 1:10,000 diluted horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG (γ-chain specific, Sigma, #A0170) in PBS-T with 1% BSA, at room temperature.

The assay included pre-determined negative and positive plasma samples, along with monoclonal antibodies CR3022 (0.1 µg/mL) targeting the spike protein and CR3009 (2 µg/mL) targeting nucleocapsid. Blank wells in duplicate served as controls. After washing, 50 μL of TMB substrate (Sera Care, #5120-0075) was added to each well and incubated for 3 minutes. The reaction was stopped by adding 50 μL of 1M hydrochloric acid (Sera Care, #5150-0021). Optical densities were measured at 450 nm, with blank well values subtracted to obtain net responses. Antibody concentrations were calculated using 4-parameter logistic standard curves and expressed in ng/mL, with values below the detection limit assigned 0 ng/mL. Longitudinal N-IgG concentrations were tracked to detect reinfection, defined by an 11-fold rise following the initial antibody peak, as previously reported [

19].

Figure 1 shows (A) the timeline of daily COVID-19 case counts and variant distribution from March 2020 to February 2022, indicating that samples collected between July 2020 and October 2021 are primarily linked to the A.23.1 and Delta variants. This figure is adapted and reused from Bbosa et al. [

38]. (B) and (C) display the baseline characteristics of the study participants, with 78% female and 61% being asymptomatic.

2.3. Preparation of SARS-CoV-2 Pseudotyped Viruses and Assessment of Neutralising Titres

Pseudotyped HIV-based viruses expressing SARS-CoV-2 spike variants D614G, B.1.617.2 (Delta), A.23.1 or Omicron (BA.4/5) were generated by culturing 3.5 x 106 HEK293T/17 cells in 10 mL of complete Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep). The cells were co-transfected with 15 μg of pHIV-Luciferase plasmid, 10 μg of HIV-Gag/Pol p8.91 plasmid and 5 μg of SARS-CoV-2 variant spike protein plasmid using 90 μg of Polyethylenimine (PEI-Max) transfection reagent.. After 18 hours, the media was replaced, and the supernatant collected 48 hours post-transfection, filtered (0.45 μm), and stored at -80°C. Heat-inactivated plasma samples were serially diluted five-fold starting at 1:25, in duplicates, using DMEM media with 10% FBS and 1% Pen/Strep. These were incubated with pseudotyped virus for 1 hour at 37°C in 96-well culture plates, followed by the addition of 12,500 HeLa cells stably expressing the human ACE-2 in 50 μL per well. The plates were incubated for 72 hours at 37°C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. Infection inhibition was assessed using Bright-Glo luciferase (Promega) and quantified on a Victor™ X3 multilabel reader (Perkin Elmer). The ID50 values, representing the dilution required to achieve 50% neutralisation, were calculated using curve fitting with the dose-response drc package in R software.

2.4. Statistical Methods

Box plots displayed the medians, means, and quartiles, while the Wilcoxon test, adjusted with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons assessed significant differences in neutralisation titres. Spearman rank correlation evaluated the relationship between neutralisation titres and binding antibody responses. Significance thresholds were defined as * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001. Non-significant results were denoted as ns (P > 0.05).

3. Results

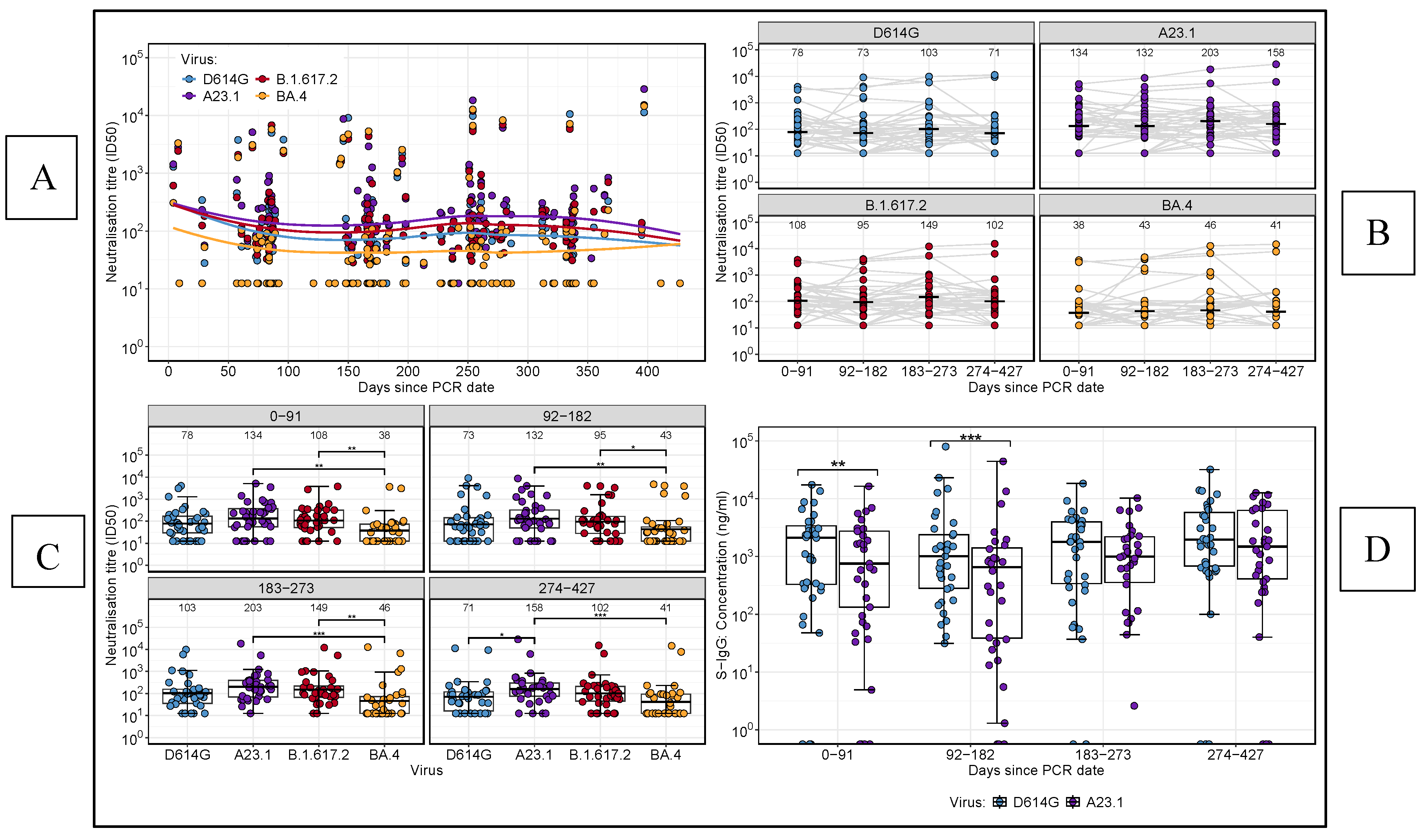

3.1. Longitudinal Analysis of Variant-Specific Neutralising Antibody Responses Revealed Temporal Trends and Stability

We analysed neutralising antibody titres over time against several SARS-CoV-2 variants A.23.1, D614G, Delta, and BA.4 (

Figure 2). Neutralisation against BA.4 remained consistently low across the study period (

Figure 2A). To provide further insights, we segmented the study into four intervals of approximately 3 months each: 0–91 days, 92–182 days, 183–273 days, and 274–427 days. Boxplot comparisons across these intervals, using an unpaired Wilcoxon test to address missing data (

Figure 2B), revealed significantly lower neutralising titres against BA.4 compared to both A.23.1 and Delta at all time points. At the final time point (274–427 days), A.23.1 titres were significantly higher than D614G variant (p < 0.05). The unpaired Wilcoxon test revealed no significant differences in neutralising titers over time for any of the viral variants, indicating a consistent neutralisation pattern throughout the study (

Figure 2C). This consistency highlights uniform temporal dynamics of neutralising antibody responses across intervals, irrespective of the viral variant. However, boxplots analysis showed significantly higher S-IgG concentrations for D614G compared to A.23.1 during the early phase of the study (p < 0.05,

Figure 2D). These results highlight the variability in neutralising responses between viral variants and underscore the importance of analysing immunogenicity in the context of dominant infection waves.

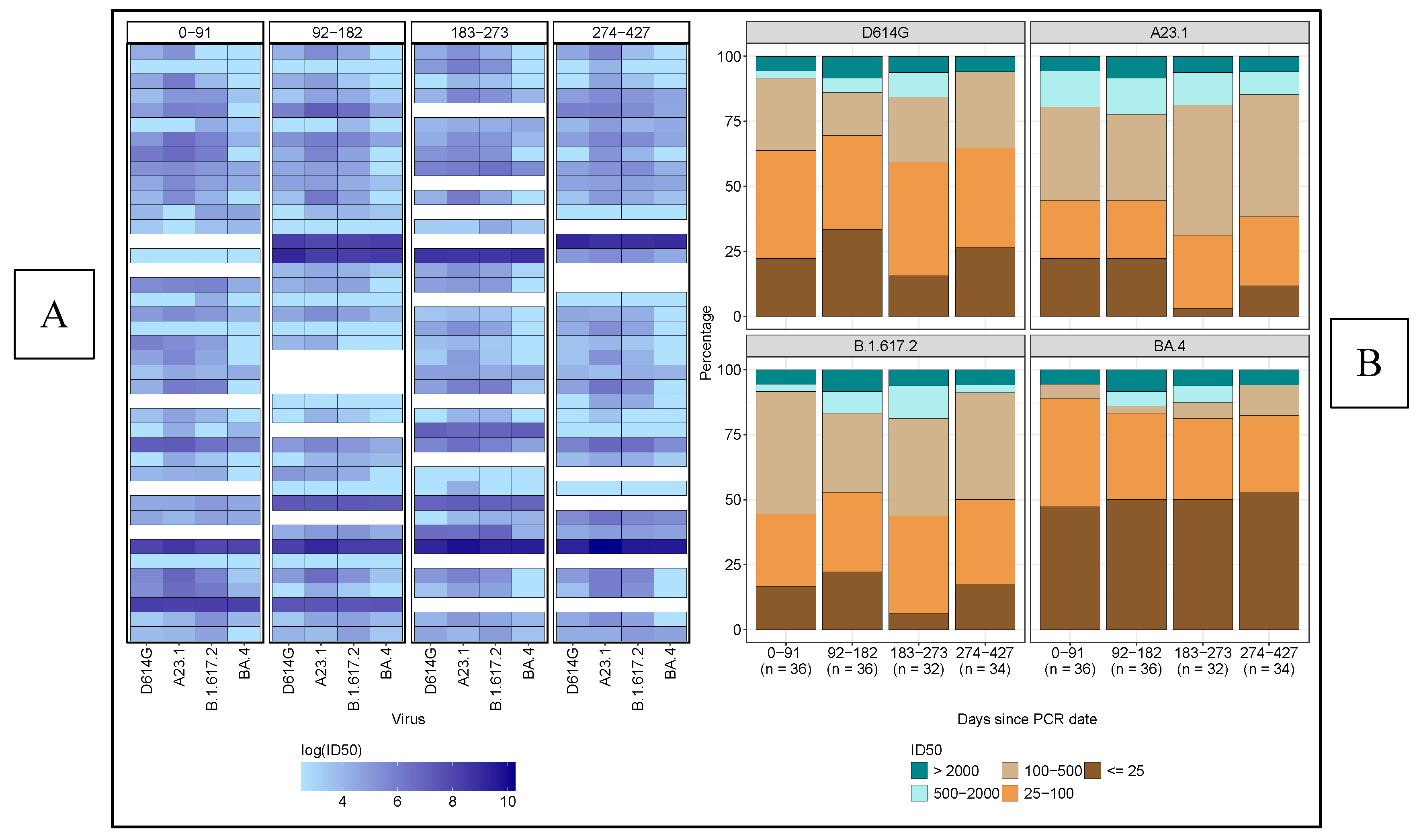

3.2. Limited Potency and Breadth of Neutralising Antibody Responses Against Diverse SARS-CoV-2 Variants, with BA.4 Demonstrating the Highest Immune Evasion

Neutralising antibody responses against diverse SARS-CoV-2 variants were limited in both potency and breadth over the 427-day observation period. As shown in the heatmap (

Figure 3A), only a small subset of participants consistently maintained high neutralisation titers across all variants and time points. Notably, BA.4 demonstrated the greatest resistance, with most participants exhibiting low neutralisation titers, reflected by lighter heatmap cells. Only a few individuals achieved robust neutralisation of this variant, underscoring the challenge of eliciting broad and durable immunity. These findings highlight the ongoing need for vaccines that provide more comprehensive protection against emerging variants

Figure 2 illustrates the longitudinal trends in neutralising antibody titres and full spike (S)-IgG concentrations across SARS-CoV-2 variants. (2A) Line plot showing neutralisation titres over time for BA.4, A.23.1, D614G, and Delta variants, with days categorized into four intervals: 0–91, 92–182, 183–273, and 274–427 days. (2B) Boxplots comparing the distribution of neutralising titres across the variants at each time point. (2C) Boxplots displaying the distribution of neutralising titres for each virus variant over time. (2D) Boxplots comparing the S-IgG concentration responses against D614G and A.23.1 variants throughout the study period.

A stacked-bar graph analysis among participants revealed that most exhibited low titres (25–100) against D614G, while intermediate titres (100–500) were more prevalent for A.23.1 across all time points (

Figure 3B,

Table 2). Delta variant responses primarily fell within the low (25–100) and intermediate (100–500) ranges, whereas BA.4 consistently showed low neutralisation titres, highlighting its significant immune evasion compared to the other variants throughout the study period. Notably, only a small fraction of participants achieved high neutralisation titres (>2000) across all variants, indicating a generally weak immune response, especially against the highly resistant BA.4 variant.

These findings show the variability in neutralising antibody potency across SARS-CoV-2 variants, with BA.4 showing the highest resistance to neutralisation. The small number of participants exhibiting consistently high titres across all time points highlights the challenge of achieving broad, potent immunity, especially against immune-evasive strains, with implications for vaccine design and long-term immune assessment.

Table 2 presents the number and corresponding proportions of subjects exhibiting varying levels of neutralising titres against each SARS-CoV-2 variant over time. The table categorizes subjects into distinct neutralisation levels, illustrating their distribution across distinct time intervals: 0-91 days, 92-182 days, 183-273 days, and 274-427 days. This breakdown provides an overview of the participant responses at low, intermediate, and high neutralisation titres for each virus variant, enabling the comparison of neutralisation patterns throughout the study period.

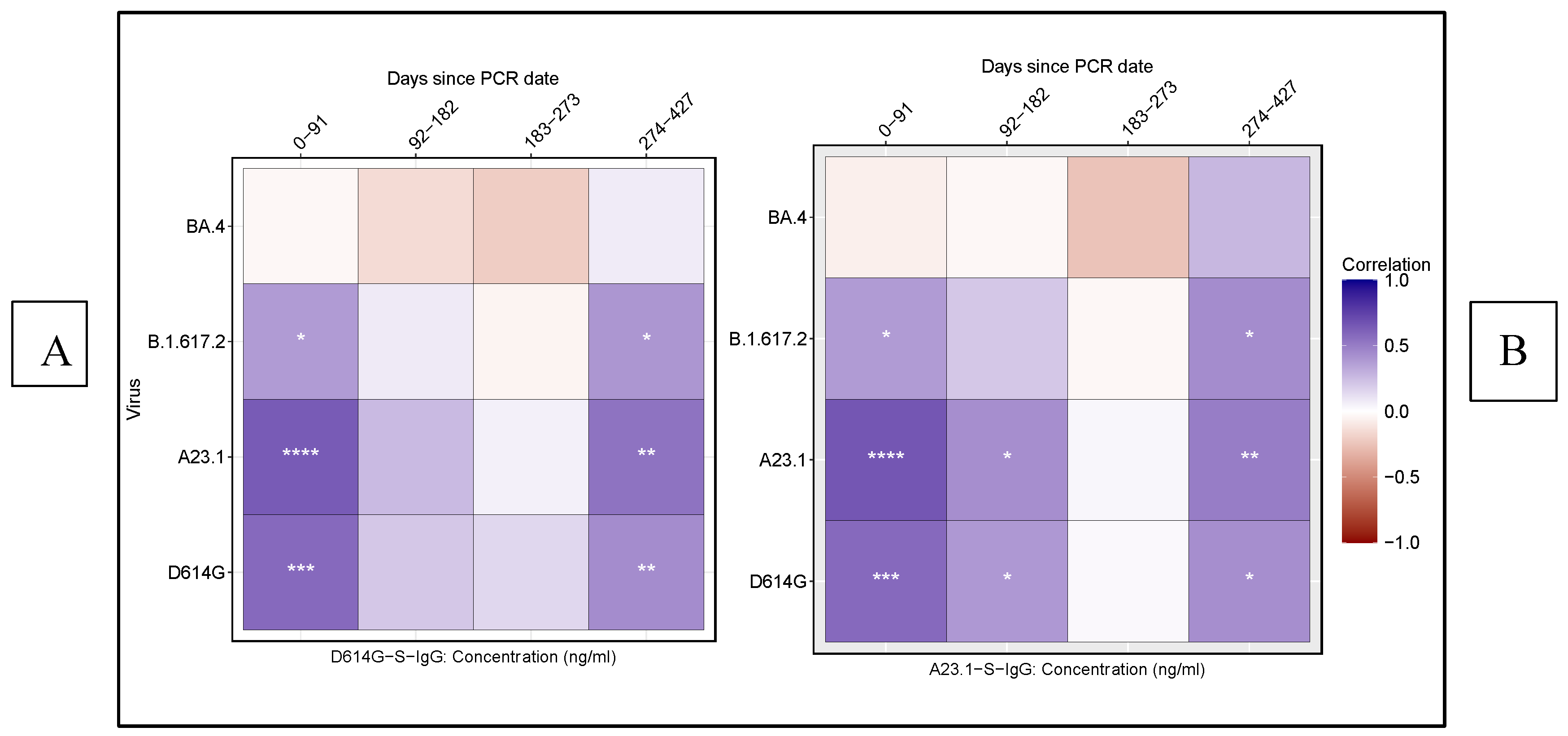

3.3. Correlation Between Neutralisation Titres and Spike-Specific IgG Binding Responses Across SARS-CoV-2 Variants

We assessed the correlation between neutralising antibody titres (ID

50) and D614G as well as A.23.1 S-IgG concentrations across SARS-CoV-2 variants D614G, A.23.1, Delta, and BA.4 over time using Spearman rank correlation analysis. For the D614G variant, we observed a significant, moderate positive correlation between neutralising titres (ID50) and S-IgG levels both in the early infection phase (0–91 days) and later phase (274–427 days) (

Figure 4A). Similar trends were noted for A.23.1 and Delta, reinforcing the consistency of the binding-neutralisation relationship across these variants. Similarly, for A.23.1 and Delta, consistent correlations were noted at these time points, indicating robust alignment between binding and neutralising responses. However, a lower correlation was detected during the intermediate phase (92–182 days) for D614G and A.23.1, suggesting a temporary decline in the binding-neutralisation relationship (

Figure 4B). No significant correlation was found for BA.4 at any time point, highlighting a distinct immune response to this variant.

These findings emphasise the temporal dynamics of antibody binding and neutralising responses, highlighting the differential correlation between S-IgG levels and neutralisation titres across various SARS-CoV-2 variants. The analysis underscores the pivotal role of spike-specific IgG antibodies in mediating protection, particularly against variants such as D614G and A.23.1. The distinct lack of correlation observed for BA.4 further illustrates its unique immunogenic properties, suggesting potential immune evasion. This divergence has significant implications for vaccine development and future therapeutic strategies, particularly in addressing variants capable of escaping immune recognition.

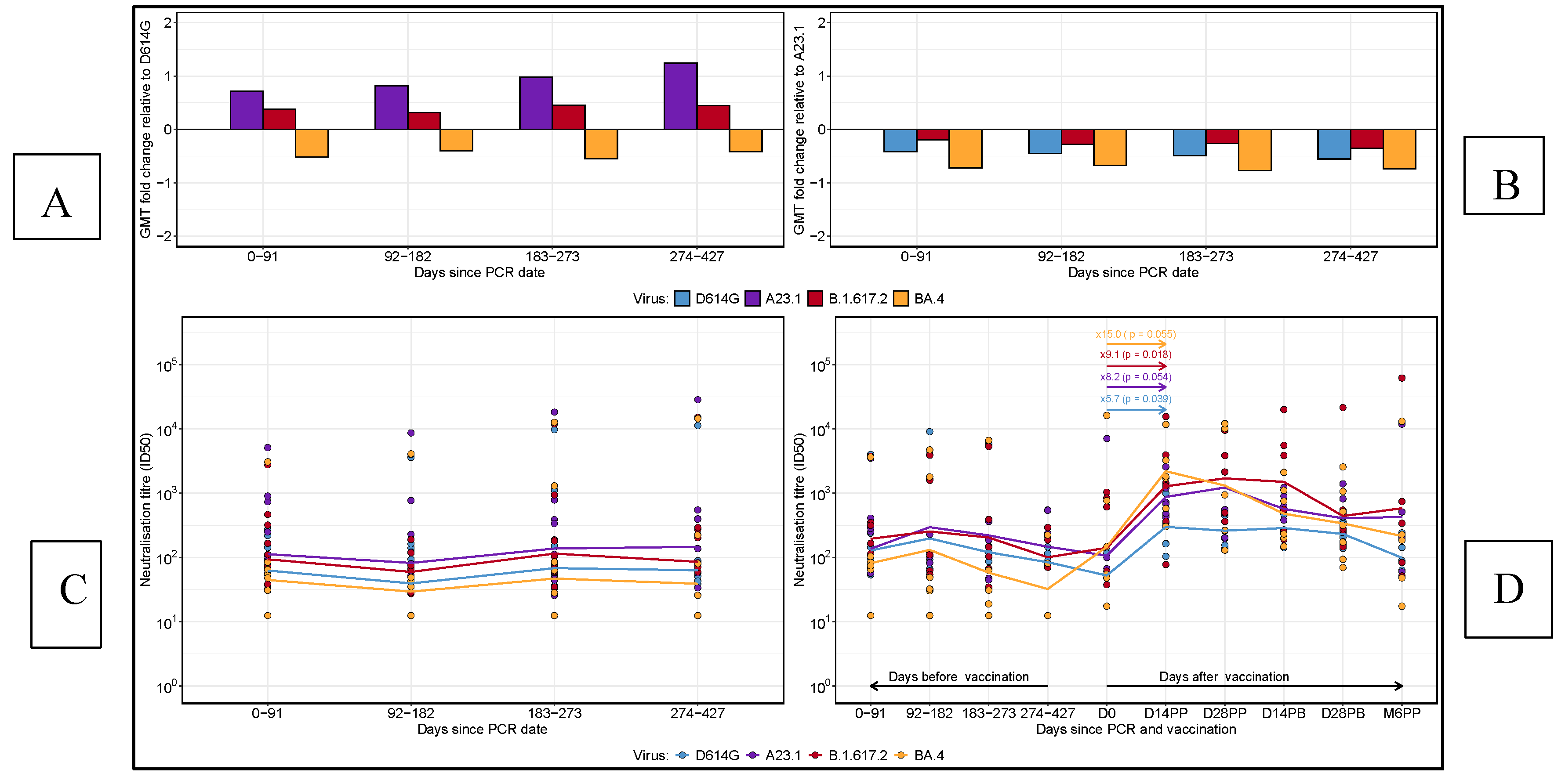

3.4. Comparative Longitudinal Analysis of GMT Fold Changes and Neutralisation Titres in Reinfected and Vaccinated Subjects

We performed a comparative analysis of geometric mean titres (GMT) fold changes relative to D614G and A.23.1 across all time points, as well as neutralising titres for 13 reinfected subjects and pre- and post-vaccination titres in 8 ChAdOx1-S-vaccinated participants (

Figure 5). At each time point, fold changes in neutralising titres were calculated for each virus variant relative to D614G (

Figure 5A) and A.23.1 (

Figure 5B). A fold change greater than 0 indicated an increase in neutralising titres, while a fold change below 0 represented a decrease. A fold change of 0 implied no change in titres. When neutralising titres were compared to D614G, Delta exhibited a marginal increase across all time points, indicating a slight enhancement in neutralising response. Over time, A.23.1 demonstrated a gradual fold increase in neutralising titres compared to D614G, signifying consistently higher titres for A.23.1. In contrast, BA.4 showed a consistent fold decrease relative to D614G, indicating lower neutralising antibody responses for BA.4 at all time points.

Figure 5 shows the geometric mean titre (GMT) fold changes in neutralising antibody responses relative to D614G (A) and A.23.1 (B) at each time point. A fold change above 0 indicates an increase, while a fold change below 0 indicates a decrease in neutralising titres relative to the reference virus. Panel C displays the neutralising titres of re-infected subjects over time, categorized by days post-infection, with a focus on variations in neutralisation responses across different virus variants. Panel D illustrates the neutralising titres before and after vaccination in vaccinated subjects, showing the comparative changes in responses to each virus variant following vaccination. Horizontal lines represent the geometric mean titres at each time point for each virus.

Relative to A.23.1 (Figure 5B), all other virus variants showed a fold decrease across all time points, highlighting the superior neutralising response elicited by A.23.1. This finding suggests that A.23.1 maintained a stronger neutralising response compared to D614G, Delta, and BA.4 throughout the study period. Neutralising titres for reinfected subjects, defined by an 11-fold or higher increase in N-IgG concentrations after the initial peak, were assessed (Figure 5C). A total of thirteen subjects met the reinfection criteria. For these individuals, neutralising titres displayed a declining trend during the first 182 days post-primary infection, followed by a gradual increase between 183 and 273 days across all virus variants. In a separate analysis of eight participants who received both doses of the AZN vaccine, we compared neutralising titres before and after vaccination (Figure 5D). BA.4 titres, which were initially low post-primary infection, rose sharply by 15-fold after vaccination. Delta titres increased by 9-fold, D614G by 6-fold, and A.23.1 by 2-fold. These results highlight the strong boosting effect of vaccination, enhancing neutralising responses against all variants, including BA.4, which had exhibited persistently lower responses pre-vaccination.

These findings highlight the dynamic nature of neutralising antibody responses across SARS-CoV-2 variants, revealing significant variability in immune recognition. The analysis underscores the profound enhancement in immune responses following vaccination, particularly against variants with initially low neutralisation profiles. The substantial post-vaccination increases in neutralising titres against BA.4, Delta, and D614G demonstrate the critical role of vaccination in bolstering the breadth of neutralising antibody responses. Furthermore, the consistently higher neutralising titres observed against A.23.1, both before and after vaccination, reinforce the observed effect of immune imprinting from the primary A.23.1 SARS-CoV-2 infection in this population. These findings have important implications for understanding variant-specific immune responses and guiding future vaccination strategies.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the long-term dynamics of neutralising antibody responses in a Ugandan cohort, with a specific focus on the influence of early exposure to the A.23.1 SARS-CoV-2 variant on subsequent immune responses to both natural infections and vaccinations with the wild-type prototype-based vaccines. Given the unique exposure history of this cohort, which first encountered the A.23.1 variant before the more globally dominant Delta and Omicron (BA.4) variants emerged, this study was justified by the need to explore the effects of immune imprinting in an African population, and its broader implications for public health and vaccine design strategies. We hypothesised that initial infection with A.23.1 would leave an immunological imprint that could influence the magnitude, specificity, and durability of neutralising responses to subsequent infections and vaccinations. Our primary finding was the sustained and robust neutralising antibody response against the A.23.1 variant, which surpassed responses to D614G, Delta, and BA.4. This highlights the potential impact of initial antigenic exposure on shaping long-term immune responses and is supported by previous observations of preferential neutralisation of the primary infecting variant over other variants [

26]. Additionally, neutralising responses to BA.4 were significantly weaker across all time points, underscoring the unique immune-evasive and antigenic divergence properties of this variant, consistent with findings from global studies on Omicron variants [

27,

28]. The higher neutralising titres against A.23.1 throughout, indicate a lasting imprint that may confer enhanced protection against this variant. These results align with the concept of immune imprinting, where the first antigen encounter primes the immune system in ways that influence responses to future exposures [

29].

Our findings revealed that, despite prior imprinting by the A.23.1 variant, vaccination in previously infected individuals substantially increased neutralising antibody titres and breadth across all tested variants. However, neutralising antibody responses to A.23.1 still remained higher than that against D614G, further highlighting the A.23.1 imprint. This suggests that prior exposure to A.23.1 did not diminish the potency and breadth of the vaccination response, even in the presence of a response favoring the primary infection variant over the variant of the vaccine-antigen, thus highlighting the effectiveness of vaccines in enhancing and broadening the immunity. This aligns with other studies showing that COVID-19 vaccines can elicit broad and potent neutralising responses regardless of prior variant exposure [

30]. Notably, our data also revealed a pronounced reduction in neutralising capacity against the BA.4 variant at all time points, aligning with this variant’s potential for immune evasion [

31]. These results corroborate prior studies demonstrating diminished vaccine efficacy and reduced antibody neutralisation against Omicron subvariants [

32,

33,

34], underscoring the necessity for ongoing surveillance and potential vaccine updates to counter evolving viral threats. Our findings introduce a crucial dimension to the literature on immune imprinting and SARS-CoV-2. While previous studies focused on the priming-effect of the original Wuhan-1 strain and subsequent variants of concern, the impact of early circulating variants such as A.23.1 were overlooked. This study bridges the gap by examining the A.23.1 variant, revealing how other non-Wuhan-1 strains like A.23.1 influence long-term immune responses.

A key strength of this study was its longitudinal design, which allowed for extended assessment of immune responses, offering a dynamic view of the antibody kinetics. The combined use of binding and neutralising antibody assays, alongside multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants, enhanced the robustness and comprehensiveness of our findings. However, the relatively small sample size and the predominance of males and asymptomatic participants could introduce bias and limit generalisability. Nonetheless, these demographics accurately represent those most affected by COVID-19 in sub-Saharan Africa.

The differential neutralising antibody responses observed against various SARS-CoV-2 variants suggest that the initial exposure to A.23.1 may have induced a unique immunological imprint, potentially through mechanisms such as epitope specificity and B-cell memory formation [

34], The lack of significant correlation between S-IgG concentrations and neutralising titres for the BA.4 variant further highlights the evolving challenges posed by new SARS-CoV-2 strains [

35]. Clinically, our results suggest that individuals initially exposed to the A.23.1 variant may have enhanced protection against similar variants but could be less protected against highly divergent strains like BA.4. This supports the need for variant-specific boosters to ensure broad and effective immunity. Moreover, the demonstrated boost in neutralising antibodies following vaccination in previously infected individuals supports the continued use of vaccines to enhance and diversify immune responses in populations with prior SARS-CoV-2 exposure. The diminished sensitivity of the BA.4 Omicron variant was anticipated, as Omicron variants possess up to 15 mutations in the receptor-binding domain (RBD) [

36,

37]. Mutations in Omicron, such as K417N, G446S, E484A, and Q493R, have been shown to significantly compromise the neutralising ability of RBD-binding antibodies whose epitopes overlap with the ACE2-binding motif.

This study provides critical insights into the impact of immune imprinting on long-term antibody responses in a Ugandan cohort exposed to the A.23.1 variant. By elucidating the specific and broad antibody responses elicited by this unique exposure, our findings contribute to the global understanding of SARS-CoV-2 immunology and highlight the importance of tailored vaccination strategies. Future research should aim to further dissect the mechanisms underlying immune imprinting and explore the implications of these findings for vaccine design and public health policy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JSer and PK; methodology, GKO, JSK, and JSer; laboratory investigation, GKO, JSem, AK, JSK, LK, CG and JSeo; data curation and formal analysis, VA, GKO and CG; resources, KJD, MHM, JAF, PK and JSer; writing—original draft preparation, JSer; writing—review and editing, GKO, JSer, PK, JAF, MHM, KJD, CG and JSeo; supervision, KJD and JSer; funding acquisition, JAF, KJD, MHM, PK and JSer. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded as part of the EDCTP2 program supported by the European Union (grant number RIA2020EF- 3008-COVAB). The work was conducted at Uganda Virus Research Institute, King’s College London and MRC/UVRI & LSHTM Uganda Research Unit which is jointly funded by the UK Medical Research Council (MRC), part of the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) and the UK Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development office (FDCO) under the MRC/FDCO Concordat agreement, and is also part of the EDCTP2 programme supported by the European Union. The work was funded in part by the Government of Uganda under the Science, Technology, and Innovation Secretariat-Office of the President (STI-OP), grant number: MOSTI-PRESIDE-COVID-19-2020/15. This publication is based on research funded in part by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation through the GIISER Uganda Grant Agreement Investment ID; INV-036306. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Uganda Virus Research Institute (Ref: GC/127/833, 7-Oct-2020) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (HS637ES, 22-Jan-2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Written Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request from the corresponding author (JSer).

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the study participants in the COVID-19 study cohort, who donated the specimens used in this study. The following reagent was produced under HHSN272201400008C and obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: Monoclonal Anti-SARS Coronavirus Recombinant Human Antibody, Clone CR3022 (produced in HEK293 Cells), NR-52481. The following reagent was obtained through BEI Resources, NIAID, NIH: Monoclonal Anti-SARS Coronavirus Recombinant Human IgG1, Clone CR3022 (produced in Nicotiana benthamiana), NR-52392. The Nucleoprotein mAb CR3009 (NIBSC Repository, Product No. 101011) used as a positive control was obtained from the Centre for AIDS Reagents, NIBSC, UK.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Monto AS, Malosh RE, Petrie JG, Martin ET. The Doctrine of Original Antigenic Sin: Separating Good From Evil. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(12):1782-8. [CrossRef]

- Haaheim, LR. Original antigenic sin. A confounding issue? Dev Biol (Basel). 2003;115:49-53.

- Rijkers GT, van Overveld FJ. The "original antigenic sin" and its relevance for SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) vaccination. Clin Immunol Commun. 2021;1:13-6. [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann P, Curtis N. Factors That Influence the Immune Response to Vaccination. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2019;32(2). [CrossRef]

- Tortorici MA, Addetia A, Seo AJ, Brown J, Sprouse K, Logue J, et al. Persistent immune imprinting occurs after vaccination with the COVID-19 XBB.1.5 mRNA booster in humans. Immunity. 2024;57(4):904-11.e4. [CrossRef]

- Johnston TS, Li SH, Painter MM, Atkinson RK, Douek NR, Reeg DB, et al. Immunological imprinting shapes the specificity of human antibody responses against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Immunity. 2024;57(4):912-25.e4. [CrossRef]

- Bayas JM, Vilella A, Bertran MJ, Vidal J, Batalla J, Asenjo MA, et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of the adult tetanus-diphtheria vaccine. How many doses are necessary? Epidemiol Infect. 2001;127(3):451-60. [CrossRef]

- Mugitani A, Ito K, Irie S, Eto T, Ishibashi M, Ohfuji S, et al. Immunogenicity of the trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in young children less than 4 years of age, with a focus on age and baseline antibodies. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2014;21(9):1253-60. [CrossRef]

- Kanesa-Thasan N, Sun W, Ludwig GV, Rossi C, Putnak JR, Mangiafico JA, et al. Atypical antibody responses in dengue vaccine recipients. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;69(6 Suppl):32-8. [CrossRef]

- Englund JA, Walter EB, Gbadebo A, Monto AS, Zhu Y, Neuzil KM. Immunization with trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in partially immunized toddlers. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):e579-85. [CrossRef]

- Chibwana MG, Moyo-Gwete T, Kwatra G, Mandolo J, Hermanaus T, Motlou T, et al. AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine induces robust broadly cross-reactive antibody responses in Malawian adults previously infected with SARS-CoV-2. BMC Med. 2022;20(1):128. [CrossRef]

- Liang C-Y, Raju S, Liu Z, Li Y, Asthagiri Arunkumar G, Case JB, et al. Imprinting of serum neutralizing antibodies by Wuhan-1 mRNA vaccines. Nature. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bugembe DL, Kayiwa J, Phan MVT, Tushabe P, Balinandi S, Dhaala B, et al. Main Routes of Entry and Genomic Diversity of SARS-CoV-2, Uganda. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(10):2411-5. [CrossRef]

- Lubinski B, Frazier LE, Phan MVT, Bugembe DL, Cunningham JL, Tang T, et al. Spike Protein Cleavage-Activation in the Context of the SARS-CoV-2 P681R Mutation: an Analysis from Its First Appearance in Lineage A.23.1 Identified in Uganda. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(4):e0151422. [CrossRef]

- Bugembe DL, Phan MVT, Ssewanyana I, Semanda P, Nansumba H, Dhaala B, et al. Emergence and spread of a SARS-CoV-2 lineage A variant (A.23.1) with altered spike protein in Uganda. Nat Microbiol. 2021;6(8):1094-101. [CrossRef]

- Bugembe DL, V.T. Phan M, Ssewanyana I, Semanda P, Nansumba H, Dhaala B, et al. A SARS-CoV-2 lineage A variant (A.23.1) with altered spike has emerged and is dominating the current Uganda epidemic. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Laing N, Mylan S, Parker M. Does epidemiological evidence support the success story of Uganda's response to COVID-19? J Biosoc Sci. 2024:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Li Q, Wu J, Nie J, Zhang L, Hao H, Liu S, et al. The impact of mutations in SARS-CoV-2 spike on viral infectivity and antigenicity. Cell. 2020;182(5):1284-94. e9.

- Serwanga J, Ankunda V, Sembera J, Kato L, Oluka GK, Baine C, et al. Rapid, early, and potent Spike-directed IgG, IgM, and IgA distinguish asymptomatic from mildly symptomatic COVID-19 in Uganda, with IgG persisting for 28 months. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1152522. [CrossRef]

- Serwanga* JA, Violet.; Katende, Ssebwana Joseph.; Baine, Claire.; Oluka, Gerald Kevin.; Odoch, Goeffrey.; Nantambi, Hellen.; Mugaba, Susan., Namuyanja, Angells.; Ssali, Ivan.; Ejou, Peter.; Kato, Laban.; The COVID-19 Immunoprofiling Team.; Musenero, Monica.; and Kaleebu, Pontiano.;. Sustained S-IgG and S-IgA Antibodies to Moderna's mRNA-1273 Vaccine in a Sub-Saharan African Cohort Suggests Need for the Vaccine Booster Timing Reconsiderations 2024.

- Serwanga J, Baine C, Mugaba S, Ankunda V, Auma BO, Oluka GK, et al. Seroprevalence and durability of antibody responses to AstraZeneca vaccination in Ugandans with prior mild or asymptomatic COVID-19: implications for vaccine policy. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1183983. [CrossRef]

- Sembera J, Baine C, Ankunda V, Katende JS, Oluka GK, Akoli CH, et al. Sustained spike-specific IgG antibodies following CoronaVac (Sinovac) vaccination in sub-Saharan Africa, but increased breakthrough infections in baseline spike-naive individuals. Frontiers in Immunology. 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Ankunda VS, Katende Joseph.; Oluka, Gerald Kevin.; Sembera, Jackson.; Claire, Baine.; Odoch, Geoffrey.; Ejou, Peter.; Kato, Laban.; Nantambi, Hellen.; Kaleebu, Pontiano.; Serwanga, Jennifer.;* The Subdued Post-Boost Spike-Directed Secondary IgG Antibody Response in Ugandan Recipients of the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 Vaccine Has Implications for Local Vaccination Policies. Front. Immunol. 2024;volume 15 - 2024. [CrossRef]

- Baine C, Sembera, J., Oluka, GK., Katende JS., Ankunda, V., Serwanga,. J. An Optimised Indirect ELISA Protocol for Detecting and Quantifying Anti-Viral Antibodies in Human Plasma or Serum: A Case Study using SARS-CoV-2; in press. Bioprotocol, Manuscript ID: 2305159. 2023.

- Oluka GK, Namubiru P, Kato L, Ankunda V, Gombe B, Cotten M, et al. Optimisation and Validation of a conventional ELISA and cut-offs for detecting and quantifying anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike, RBD, and Nucleoprotein IgG, IgM, and IgA antibodies in Uganda. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1113194. [CrossRef]

- Bekliz M, Adea K, Vetter P, Eberhardt CS, Hosszu-Fellous K, Vu D-L, et al. Neutralization capacity of antibodies elicited through homologous or heterologous infection or vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 VOCs. Nature Communications. 2022;13(1):3840.

- Pastorio C, Noettger S, Nchioua R, Zech F, Sparrer KMJ, Kirchhoff F. Impact of mutations defining SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1 and BA.4/5 on Spike function and neutralization. iScience. 2023;26(11):108299. [CrossRef]

- Wang Q, Guo Y, Iketani S, Nair MS, Li Z, Mohri H, et al. Antibody evasion by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5. Nature. 2022;608(7923):603-8. [CrossRef]

- Reynolds CJ, Pade C, Gibbons JM, Butler DK, Otter AD, Menacho K, et al. Prior SARS-CoV-2 infection rescues B and T cell responses to variants after first vaccine dose. Science. 2021;372(6549):1418-23. [CrossRef]

- Liang CY, Raju S, Liu Z, Li Y, Asthagiri Arunkumar G, Case JB, et al. Imprinting of serum neutralizing antibodies by Wuhan-1 mRNA vaccines. Nature. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Cao Y, Wang J, Jian F, Xiao T, Song W, Yisimayi A, et al. Omicron escapes the majority of existing SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies. Nature. 2022;602(7898):657-63. [CrossRef]

- Guo H, Ha S, Botten JW, Xu K, Zhang N, An Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron: Viral Evolution, Immune Evasion, and Alternative Durable Therapeutic Strategies. Viruses. 2024;16(5). [CrossRef]

- Mannar D, Saville JW, Zhu X, Srivastava SS, Berezuk AM, Tuttle KS, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant: Antibody evasion and cryo-EM structure of spike protein-ACE2 complex. Science. 2022;375(6582):760-4. [CrossRef]

- Yisimayi A, Song W, Wang J, Jian F, Yu Y, Chen X, et al. Repeated Omicron exposures override ancestral SARS-CoV-2 immune imprinting. Nature. 2024;625(7993):148-56. [CrossRef]

- Di H, Pusch EA, Jones J, Kovacs NA, Hassell N, Sheth M, et al. Antigenic Characterization of Circulating and Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants in the U.S. throughout the Delta to Omicron Waves. Vaccines (Basel). 2024;12(5). [CrossRef]

- Starr TN, Greaney AJ, Addetia A, Hannon WW, Choudhary MC, Dingens AS, et al. Prospective mapping of viral mutations that escape antibodies used to treat COVID-19. Science. 2021;371(6531):850-4. [CrossRef]

- Jawad B, Adhikari P, Podgornik R, Ching WY. Impact of BA.1, BA.2, and BA.4/BA.5 Omicron mutations on therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Comput Biol Med. 2023;167:107576. [CrossRef]

- Bbosa N, Ssemwanga D, Namagembe H, Kiiza R, Kiconco J, Kayiwa J, et al. Rapid replacement of SARS-CoV-2 variants by delta and subsequent arrival of Omicron, Uganda, 2021. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28(5):1021. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).