1. Introduction

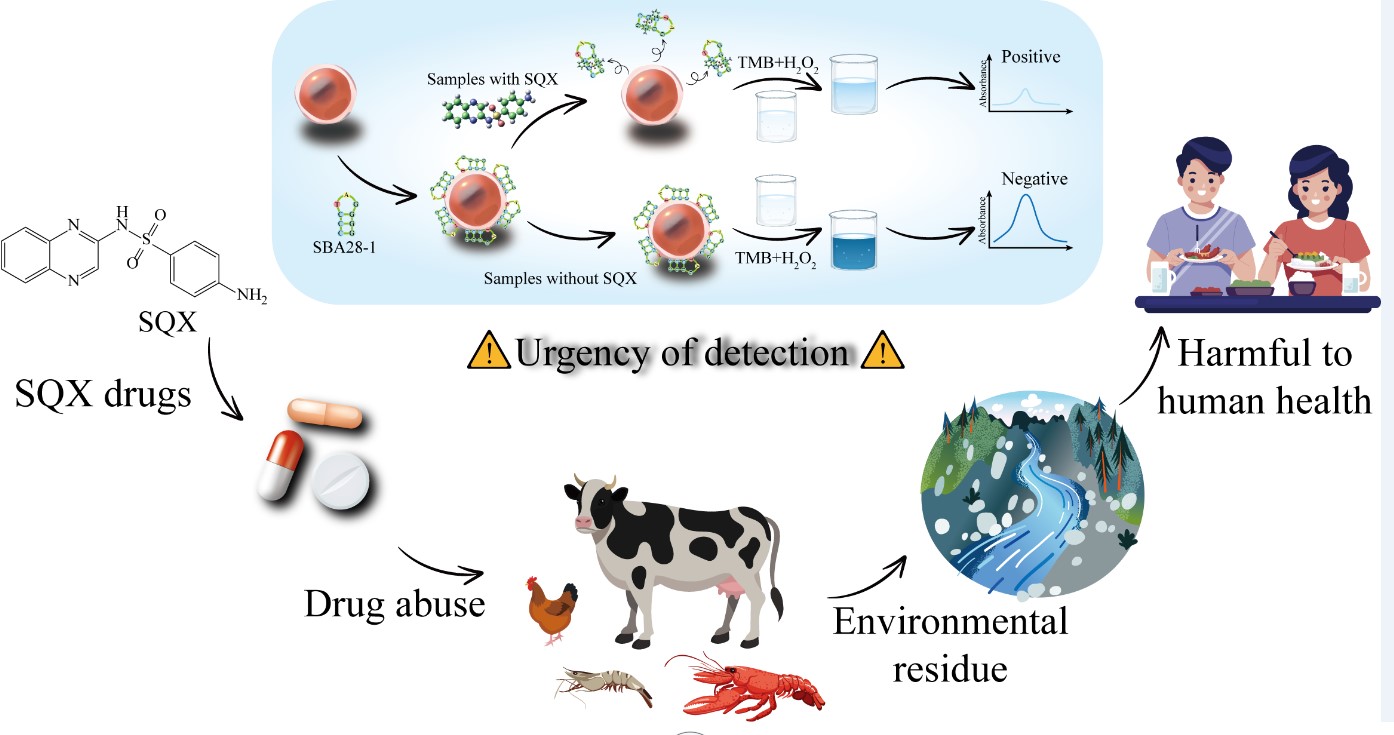

Sulfaquinoxaline (SQX) is a commonly used sulfonamide veterinary antibiotic with the advantages of broad antimicrobial spectrum and low price, which is widely used for treating and preventing bacterial infections in aquaculture and animal husbandry [

1,

2]. However, SQX degrades slowly and persists in the environment, with residual SQX detectable in both surfacewater and groundwater [

3]. SQX in water environment can enter the food chain through direct consumption or by aquatic organisms and crops, which may cause allergies, affect intestinal bacteria, lead to digestive and urinary dysfunction, and jeopardize human health [

4,

5,

6]. Consequently, the maximum residual limit for SQX has been established at 100 μg/kg in several countries, including China, the United States, and European nations [

7,

8]. Therefore, it is critical to develop an effective and rapid assay that can detect SQX residues.

There are currently several detection techniques used to detect SQX residues. The more common methods are high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [

9,

10,

11], liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [

12], ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UHPLC-MS/MS) [

13,

14], and capillary electrophoresis (CE) [

15,

16], which have high sensitivity and stability, but the equipment is expensive, complicated to operate, and requires specialized personnel. In addition, immunoassay methods for detecting of SQX, such as immunochromatographic assays (ICA) [

17], have been reported to provide rapid and highly sensitive results. However, it is difficult to prepare antibodies that recognize SQX, and the antibodies vary widely from batch to batch. Therefore, a novel and economical molecular probe for recognizing SQX is urgently needed. Aptamers, first proposed by Ellington [

18] and Tuerk [

19], are a kind of single-stranded ssDNA or RNA molecules selected from a random nucleic acid sequence library using SELEX technology, which have the advantages of shorter fabrication period, lower production cost, and better stability compared with antibodies [

20,

21]. Aptamers usually fold into some specific structures and recognize the target with high affinity and specificity through hydrogen bonds, van der Waals interactions, and other mechanisms [

22,

23].

As a kind of functional oligonucleotides, aptamers can be applied in various fields, including biosensing, medical imaging, and targeted drug delivery [

24,

25,

26]. Currently, the preparation of various aptasensors using aptamer-conjugated nanomaterials has become a research hotspot for environmental monitoring and food safety hazard detection. Zheng et al [

27]. constructed a fluorescent aptasensor based on graphene oxide, where one end of the aptamer that specifically binds to 1-aminolevulinic acid is modified with a FAM-labeled fluorescence, and a high specificity and high sensitivity detection of the target can be achieved by generating fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Tang et al [

28]. developed a dual fluorescent aptasensor based on silica composites using two aptamers modified by FAM and CY5, immobilized on a silica surface by a carboxyl-modified cDNA linker, which demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for sulfadimethoxine and oxytetracycline. Zhang et al [

29]. labeled the 3′ end of Sul-01 with FAM as a fluorescence donor, while the 5′ end was labeled with NED as a fluorescence acceptor, as well as designed the quenching probe BHQ2-P

Q-01, based on the fluorescence resonance energy transfer between FAM and NED, to develope a fluorescence aptasensor for detecting SQX. Li et al [

30]. immobilized double-stranded DNA on AuPd NPs@UiO-66-NH2/CoSe2 nanocomposites, and in the presence of SQX, its corresponding aptamer would be released from the double-stranded structure, the electrical signals would be increased accordingly, an electrochemical aptasensor for detecting SQX was designed. Most of these aptasensors for detecting SQX require a labeled modification of the aptamer, which may have some effect on the affinity of the aptamer and is not conducive to high-affinity binding between the aptamer and the target. Avoiding the use of expensive labels (e.g., fluorescent dyes and nanoparticles) to modify the aptamer would be more conducive to the binding between the aptamer and the target, the aptasensor would be easier to prepare and use, making label-free aptasensor cost-effective and suitable for widespread application.

Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) are widely recognized as nanomaterials with potential applications. It has been reported that AuNPs can be used in aptasensors for the detection of targets by colorimetric methods in the past due to their advantages of simple synthesis, large specific surface area, and high chemical stability [

31,

32,

33]. Yang et al [

34]. constructed an aptasensor based on aflatoxin B1 chimeric ligands and AuNPs, and utilized the peroxidase activity of AuNPs for the colorimetric detection of the corn oil of AFB1 was colorimetrically detected, and the aptasensor had high sensitivity and specificity, which is suitable for application in food safety monitoring. Wang et al [

35]. developed a noncompetitive colorimetric aptasensor for sensitive detection of diarrheal shellfish toxins using aptamer and hybridization chain reaction-assisted AuNPs. The aptasensor showed high sensitivity and specificity for target toxins in shellfish samples. AuNPs have peroxidase-like activity, which can oxidize TMB and generate colorimetric signals in the presence of H

2O

2. Surface negatively charged aptamers due to the dissociation of phosphate groups can bind to AuNPs, thus creating an electrostatic interaction with TMB and increasing its local concentration, resulting in more TMB oxidation and a stronger colorimetric signal. Given that aptasensor constructed with AuNPs is simple, cost-effective, and colorimetric signal can be detected [

36,

37], we developed a label-free aptasensor based on aptamer functionalized AuNPs for colorimetric detection of SQX.

In this study, a label-free aptasensor for the rapid detection of SQX was developed using AuNPs and SQX aptamers screened by our laboratory. The aptasensor realized the rapid detection of SQX in different water samples and the performance was compared with HPLC. The aptasensor is characterized by high specificity, low cost and simple operation, which provides a novel method for the detection of SQX residues in the water environment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

The SQX-specific aptamer SBA28-1 (5'-CCCTAGGGG-3') used in this experiment were screened by our laboratory [

38,

39] and synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai, China). SQX, sulfadimethoxine (SMM), sulfadimethoxine (SME), sulfadimethoxine (SDM), sulfamethoxymethoxine (SMZ) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). ofloxacin (OFL), Oxytetracycline (OTC), chloramphenicol (CAP), and chlortetracycline (CTC) were purchased from Aladdin Biotechnology Inc (Shanghai, China). AuNPs were synthesized following a previously established protocol [

40].

2.2. Colorimetric Aptasensor Detection of SQX

Initially, 25 nM of the aptamers was incubated with a series of different SQX solution concentrations for 30 minutes at room temperature using a constant temperature shaking incubator. Following this incubation, 50 μL of AuNPs solution was added and after thorough mixing and shaking for 30 minutes, 1.2 mM of TMB and 1.2 M of H₂O₂ were added, and shaking was continued for an additional 10 minutes. The final volume of the reaction system was 300 μL. The absorbance value of the mixture was measured at 650 nm and the ΔA650 value was calculated at different SQX concentrations (ΔA650=A0-ASQX, where A0 is the absorbance value without the addition of SQX solution and ASQX is the absorbance value after the addition of SQX solution). The aptamers were dissolved in binding buffer, while TMB and H2O2 were dissolved in sodium acetate buffer (pH 4.0).

2.3. Optimization of Conditions

First, different concentrations of aptamer (10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 nM) were incubated with 1 μg/mL of SQX for 30 minutes and then 50 μL of AuNPs were added, mixed and shaken for another 30 minutes. Then, 1.2 mM TMB and 1.2 M H2O2 were added, and the mixture was allowed to react for 10 minutes. The absorbance of the solution was measured, and the ΔA₆₅₀ value was calculated by determining the difference between the absorbance of the blank group without added SQX (A₀) and that of the experimental group with SQX (ASQX) (ΔA₆₅₀ = A₀ - ASQX).

In addition, to investigate the effect of pH on the experimental results, the pH of the solution was adjusted with glacial acetic acid to 3.0, 3.5, 4.0, 4.5, and 5.0. A 25 nM aptamer was then incubated with 1 μg/mL of SQX for 30 minutes. Following this, 50 μL of AuNPs were added and shaken for 30 minutes. Then, 1.2 mM TMB and 1.2 M H₂O₂ were added for 10 minutes reaction, after which the absorbance values were measured and ΔA₆₅₀ was calculated.

Next, to optimize the concentration of TMB, a 25 nM aptamer was incubated with 1 μg/mL of SQX for 30 minutes and then mixed with AuNPs for another 30 minutes. Different concentrations of TMB (0.8, 1.0, 1.2, 1.4, and 1.6 mM) along with 1.2 M H₂O₂ were added to react for 10 minutes, followed by measuring the absorbance of the solution and calculating ΔA₆₅₀.

Finally, to optimize the concentration of H₂O₂, a 25 nM aptamer was incubated with 1 μg/mL of SQX for 30 minutes before adding AuNPs to react for another 30 minutes. Then, 1.2 mM TMB and different concentrations of H₂O₂ (0.3, 0.6, 0.9, 1.2, and 1.5 M) were added and reacted for 10 minutes. The absorbance of the solution was measured, and ΔA₆₅₀ was calculated to determine the optimal concentration of H₂O₂.

2.4. Analytical Performance of the Aptasensor

Next, we evaluated the performance of the aptasensor. To verify its sensitivity, various concentrations of SQX (20, 40, 80, 160, 320, 640, 1280, and 2000 ng/mL) were incubated with 25 nM of aptamer for 30 minutes, then added to AuNPs to continue the reaction for another 30 minutes. 1.2 mM TMB and 1.2 M H₂O₂ were introduced, and the mixture was allowed to react for 10 minutes. The absorbance values of the solutions were measured, and the magnitude of ΔA₆₅₀ was calculated. The standard curves were established at different concentrations of SQX, the limit of detection (LOD) was calculated as 3 SD/slope, where SD is the standard deviation of the blank sample and slope is the slope of the linear regression curve. On the other hand, various interfering substances including SMM, SMZ, SME, SDM, CAP, OFL, OTC, and CTC were chosen to replace SQX, the concentration of each antibiotic was 1 µg/mL. The 25 nM aptamer was incubated with these antibiotics for 30 minutes before being mixed with AuNPs for another 30 minutes. Then, 1.2 mM TMB and 1.2 M H₂O₂ were added and allowed to react for 10 minutes. The absorbance values at 650 nm were measured for both experimental and control groups, and the specificity of the aptasensor was determined by comparing the magnitude of ΔA₆₅₀ produced by SQX with that of the different interferents.

2.5. Analysis of Real Samples

The aptasensor was evaluated using lake water and tap water to confirm the effectiveness and accuracy of the aptasensor. The samples were centrifuged to remove impurities with a 0.22 μm filter membrane, and the absence of SQX in the water samples was confirmed using HPLC. 10 mL of the water samples were then taken and spiked with various concentrations of SQX (50, 100, and 150 ng/mL) for the spiked recovery test. Firstly, the SQX-containing water samples were incubated with the aptamer for 30 minutes, followed by the addition of 50 μL of AuNPs for another 30 minutes. Then, 1.2 mM TMB and 1.2 M H₂O₂ were added, and the mixture was allowed to react for 10 minutes before measuring the absorbance values. In addition, the same lake water and tap water containing different concentrations of SQX were detected by HPLC. The chromatographic column was a ZORBAX SB-C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm, 5 μm), and the mobile phases were 2% glacial acetic acid (A) and 100% methanol (B). Recovery was calculated using the formula (measured concentration/known concentration) × 100%. Each spiked sample was analyzed five times to ensure statistical reliability [

41].

3. Results and Discussion

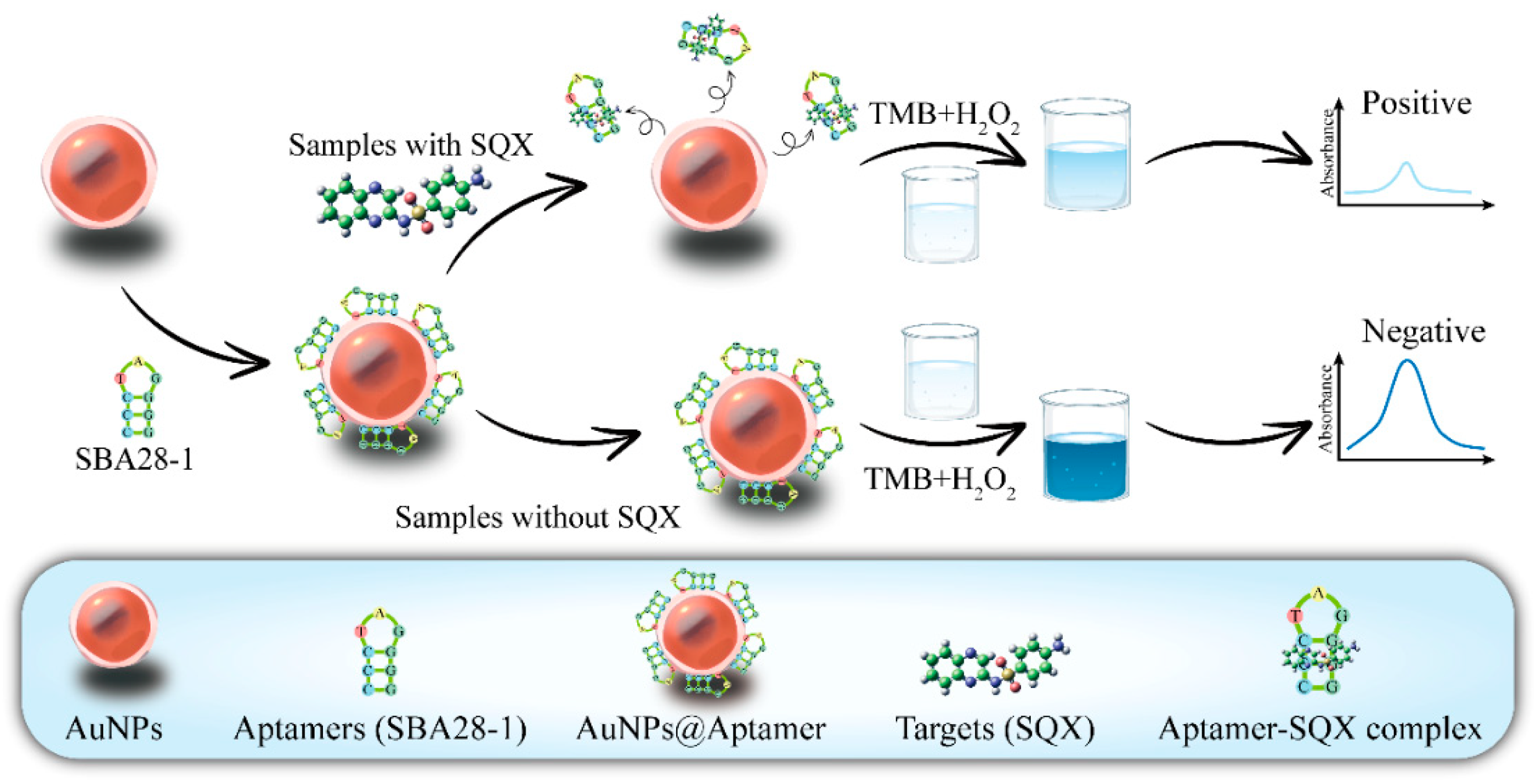

3.1. Principles of the Aptasensor

The principle of SQX detection based on aptamer and AuNPs is illustrated in

Figure 1. H

2O

2 is a common oxidant that oxidizes colorless TMB to blue TMB oxide, exhibiting an absorption peak at 650 nm [

42]. And AuNPs have peroxidase-like activity, which can be used as a catalyst to accelerate the process of this reaction. When the DNA aptamer binds to the surface of the AuNPs, its negatively charged phosphate backbone is exposed on the surface of the AuNPs. This increases the negative charge density of the aptamer-AuNPs complex, enhancing its interaction with the positively charged substrate TMB and significantly boosting enzyme activity, resulting in the generation of more blue TMB oxides [

43,

44]. When SQX is added to the system, the aptamer binds to SQX and is no longer adsorbed onto AuNPs, which weakens the catalytic effect of AuNPs, so the TMB oxides produced in the same time are reduced and the solution changes from dark blue to light blue. Therefore, the concentration of SQX can be detected by measuring the absorbance value at 650 nm of the solution before and after the addition of SQX.

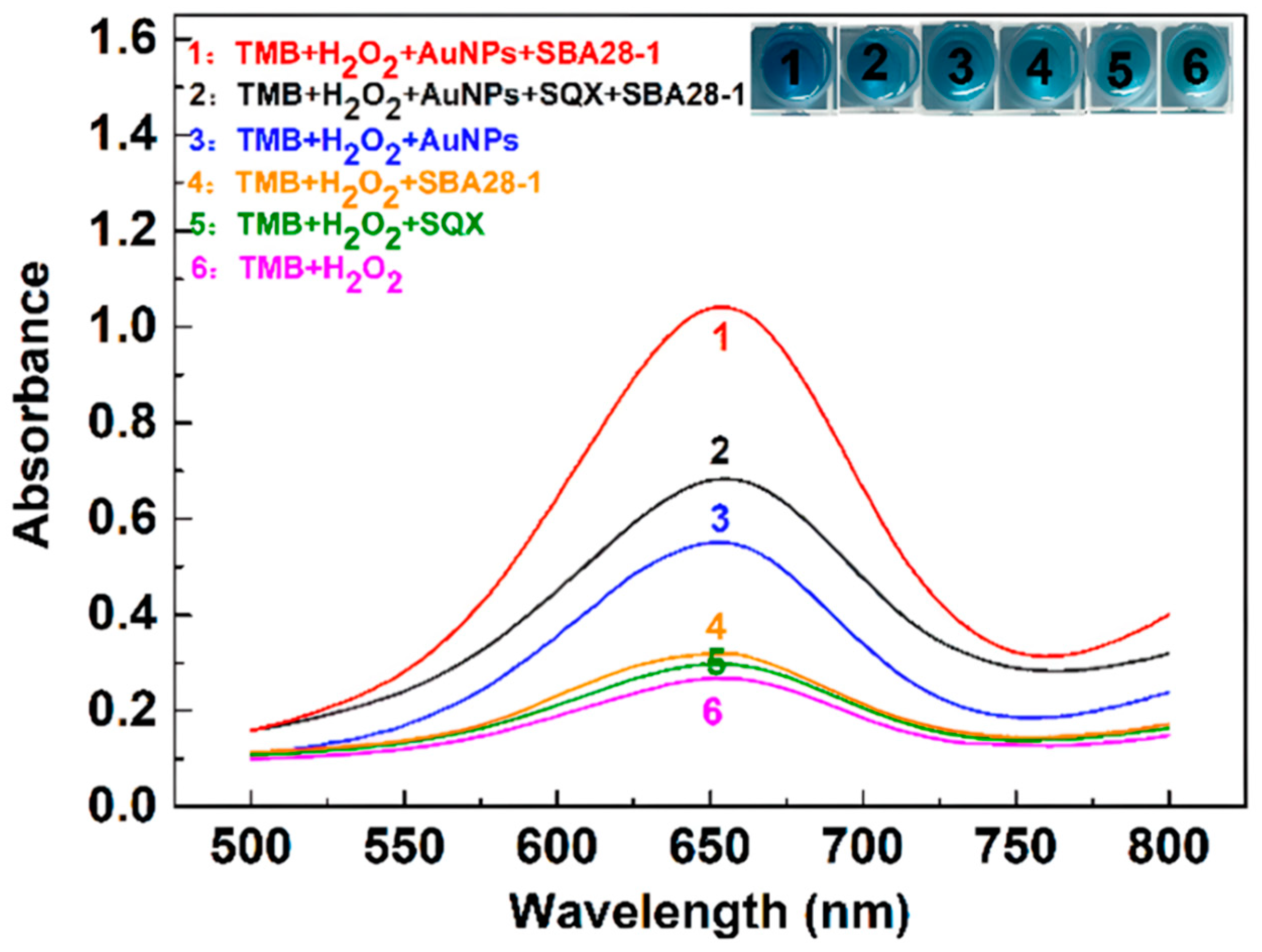

3.2. Feasibility of the Aptasensor

Different substances were added to the system of TMB and H

2O

2 for the study. As shown in

Figure 2 , curves 1 and 2 indicate that after addition of SQX, the aptamer binds to SQX, the catalytic ability of AuNPs decreases and the absorbance value of the solution at 650 nm decreases. Curves 1 and 3 show that the catalytic ability of AuNPs increased after the addition of aptamer to the solution containing AuNPs, and the blue color of the solution became darker. According to curves 3 and 6, it can be seen that H

2O

2 alone oxidizes TMB but produces less TMB oxide compared to the solution with the addition of AuNPs. Additionally, the presence of SQX or the aptamer alone does not affect the reaction between TMB and H₂O₂ (curves 4, 5, and 6).

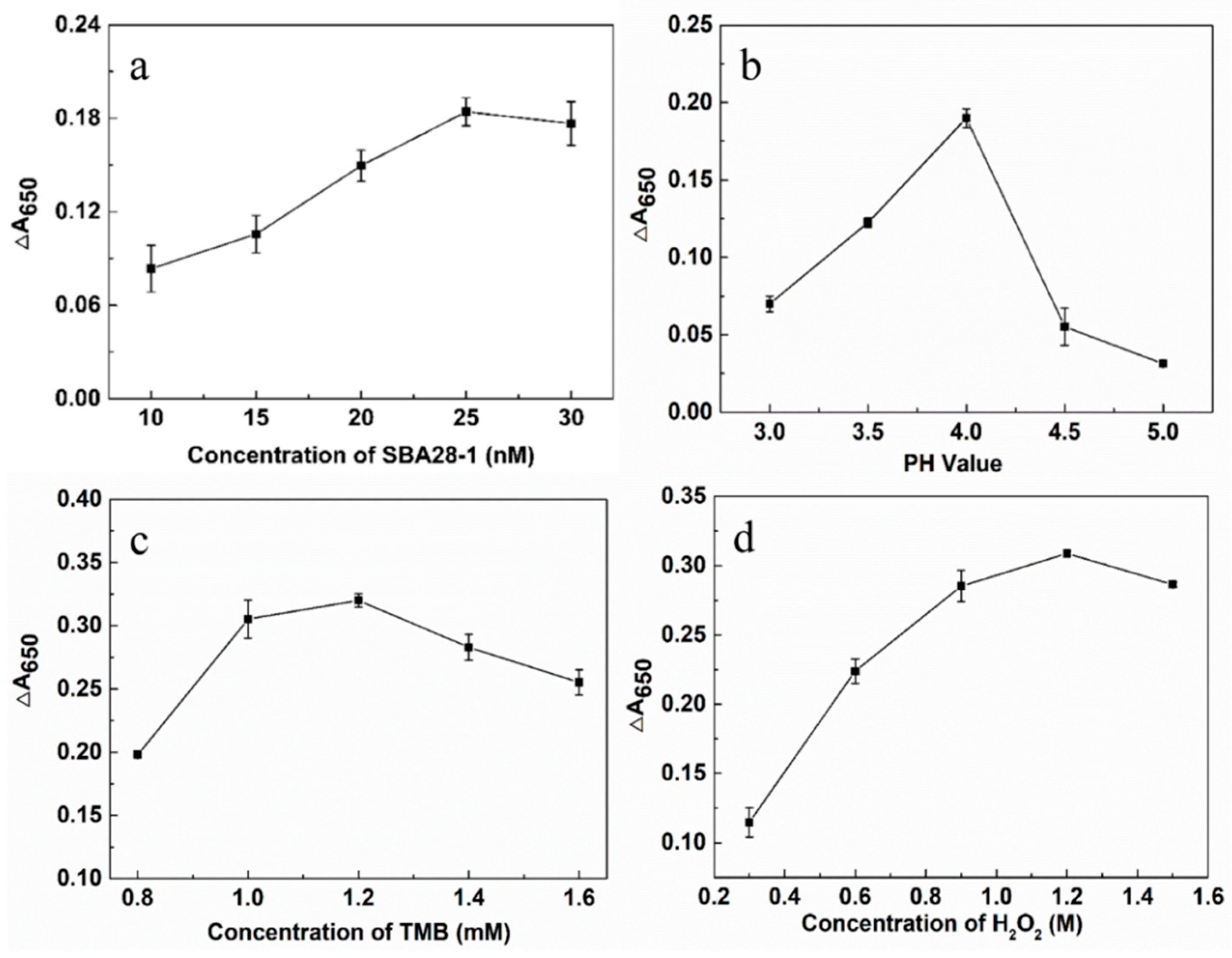

3.3. Optimization of the Aptasensor

In order to optimize the detection conditions of the aptasensor, we evaluated the concentration of the aptamer, the pH value of the solution as well as the concentrations of TMB and H

2O

2. The concentration of the aptamer, as the recognition element of the target SQX, had a large impact on the sensitivity of the aptasensor. With the increase of the concentration of the aptamer, the ΔA

650 continued to rise until the concentration reached 25 nM, at which time ΔA

650 peaked, indicating that all AuNPs had been encapsulated by the aptamer and its catalytic effect was optimal. Therefore, the optimal aptamer concentration for this aptasensor was determined to be 25 nM (

Figure 3a). In addition, the pH of the solution affects the decomposition rate of H

2O

2 catalyzed by AuNPs, and either too high or too low pH can lead to a decrease in the catalytic activity of the enzyme. The maximum difference in absorbance of the solution at 650 nM was observed when the pH of the solution was 4.0 (

Figure 3b). Therefore, the pH of the solution was determined to be 4.0. ∆A

650 then reached a maximum at 1.2 mM TMB (

Figure 3c), which was considered to be the optimal TMB concentration. ΔA650 continued to increase until the H₂O₂ concentration reached 1.2 M (

Figure 3d), so 1.2 M H₂O₂ was selected for subsequent experiments.

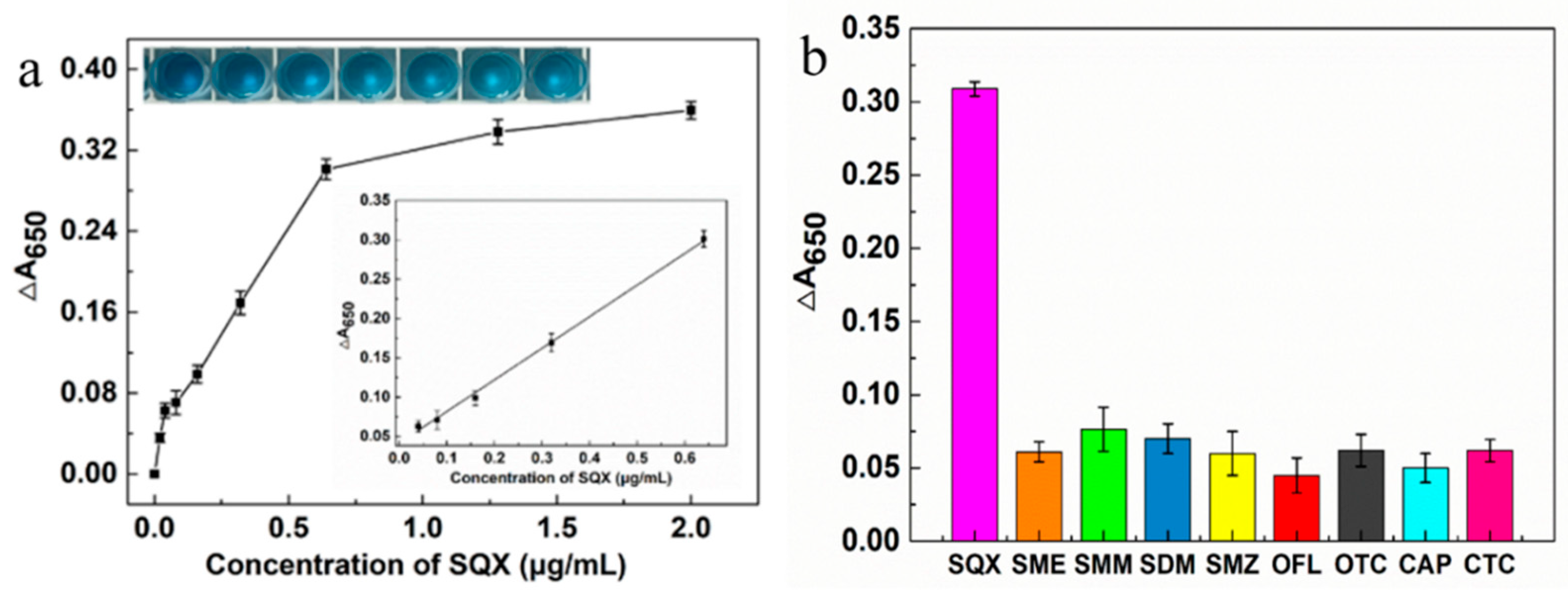

3.4. Sensitivity and Specificity of the Aptasensor

As shown in

Figure 4a, a linear regression equation was obtained based on the measured absorbance values of different SQX concentrations (20, 40, 80, 160, 320, 640, 1280, 2000 ng/mL) at 650 nm and their differences from the control. In the concentration range of 40-640 ng/mL, the absorbance difference exhibited a positive correlation with SQX concentration, resulting in the linear fitting equation Y = 0.4059X + 0.0397 (R² = 0.997) and a limit of detection (LOD) value of 36.95 ng/mL. To investigate the specificity of this aptasensor, four sulfonamides (SME, SMM, SDM, SMZ) and four non-sulfonamides (OTC, CTC, OFL, CAP) were used to test its specificity. As shown in the

Figure 4b, the ∆A

650 values of the eight non-SQX drugs were all below 0.07, which were significantly lower than the ∆A650 values for SQX, indicating that the aptasensor had a high specificity for SQX. According to chen et al [

39]. the aptamer SBA28-1 bases A-5, G-6 and G-7 form four hydrogen bonds with SQX, the aptamer SBA28-1 bases A-5 and G-6 have three π-sulfur interactions with SQX, and the aptamer SBA28-1 bases G-6 have two π-π T-shaped interactions with SQX. Such a special binding mechanism may be an important reason for the specificity exhibited by this aptasensor.

3.5. Validation of the Aptasensor

To evaluate the performance of the aptasensor in different water samples, various concentrations of SQX (50, 100, and 150 ng/mL) were added to SQX-free lake water and tap water. The experiment was repeated five times (n = 5) for each concentration, while the same samples were analyzed by HPLC to compare the results of both. As shown in the

Table 1, the recoveries of the aptasensor for the detection of SQX in lake and tap water ranged from 90.0% to 109.9% with coefficients of variation of 4.5% to 12.6%. The recoveries ranged from 99.0% to 101.8% with coefficients of variation of 0.9% to 3.4% when the samples were detected by HPLC. It can be seen that the present aptasensor shows a good correlation with the HPLC results. In addition, compared with other analytical methods for SQX detection (

Table 2), the aptasensor constructed in this study is cheaper and simpler to fabricate, has a higher reliability, making it promising for detecting SQX in various water samples.

4. Conclusions

Here, we successfully constructed an aptasensor for the detection of SQX , utilizing the principle that AuNPs catalyze the oxidation of TMB by H₂O₂, while the aptamer enhances the catalytic effect of the AuNPs. Compared with the traditional instrumental methods, the aptasensor is simpler and more convenient, which is more suitable for rapid detection on site. Unlike immunological methods that require specific antibodies, the aptamer, as a novel recognition molecule, is more readily available than antibodies, and the aptasensor is also able to rapidly detect SQX residues. In addition, avoiding the use of expensive labels such as fluorescent dyes or nanoparticles to modify the aptamer, the aptasensor becomes more cost-effective, easier to prepare, and widely available. The aptasensor constructed in this paper demonstrated good linearity (Y=0.4059X+0.0397, R2=0.997) at SQX concentrations ranging from 40 to 640 ng/mL, with the lowest detection limit of 36.95 ng/mL. The spiked recoveries of lake water and tap water were ranged from 90% to 109.9%, with coefficients of variation from 4.5% to 12.6%. The detection results of the aptasensor and HPLC showed good correlation. The results showed that the aptasensor can effectively detect the residual SQX in aqueous environments, and its detection range is wide, which has a good application prospect.

Author Contributions

Z.Z., conceptualization, methodology, writing. X.C., methodology, validation, investigation. S.J., methodology, resources, software. Z.C., validation, investigation, visualization. S.W., validation, supervision, visualization. Y.R., resources, supervision, validation. X.F., conceptualization, supervision. T.L., conceptualization, writing editing, supervision.

Funding

This research was supported by the Science and Technology Research Program of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (Grant No. KJZD-M202400501) and the Postgraduate Scientific Research and In-novation Project of Chongqing Municipal Education Commission (CYS23395).

Conflicts of Interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work; there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service, and/or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, the manuscript entitled “A label-free aptasensor for the detection of sulfaquinoxaline using AuNPs and aptamer in water environment”.

References

- Aminov, R. History of antimicrobial drug discovery: Major classes and health impact. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 133, 4–19. [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, S.; Kakarla, D.; Venkateswarlu, K.; Megharaj, M.; Yoon, Y.-E.; Lee, Y.B. Veterinary antibiotics (VAs) contamination as a global agro-ecological issue: A critical view. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 257, 47–59. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W., Zheng, M., Sun, J., Tian, Y., Fang, M., Zheng, Y., Zhang, T., and Zheng, C. Photolysis of enrofloxacin, pefloxacin and sulfaquinoxaline in aqueous solution by UV/H2O2, UV/Fe(II), and UV/H2O2/Fe(II) and the toxicity of the final reaction solutions on zebrafish embryos. Science of the Total Environment 2018, 651, 1457-1468.

- Yan, Z.; Tong-Shuai, L.; Xiao-Zhuang, W.; Yu-Can, L.; Chen, Z.; Hao, L.; Yi-Hong, Z. Using quantum chemistry theory to elucidate the mechanism for treating sulfonamide antibiotic wastewater by progressive freezing. J. Water Process. Eng. 2023, 53. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Li, S.; Pang, C.; Xiong, Y.; Li, J. A Cu(II)-anchored unzipped covalent triazine framework with peroxidase-mimicking properties for molecular imprinting-based electrochemiluminescent detection of sulfaquinoxaline. Microchim. Acta 2018, 185, 546. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, J.; Duan, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J. Inactivation of sulfonamide antibiotic resistant bacteria and control of intracellular antibiotic resistance transmission risk by sulfide-modified nanoscale zero-valent iron. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 400, 123226. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, L.; Xu, L.; Song, S.; Kuang, H.; Cui, G.; Xu, C. Gold immunochromatographic sensor for the rapid detection of twenty-six sulfonamides in foods. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 2833–2844. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Pan, Y.; Sun, C.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Fu, F. A multicolor immunosensor for the visual detection of six sulfonamides based on manganese dioxide nanosheet-mediated etching of gold nanobipyramids. Talanta 2023, 258, 124449. [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, H.I.; Abdel-Salam, R.A.; Hadad, G.M. Tolerance intervals modeling for design space of a salt assisted liquid-liquid microextraction of trimethoprim and six common sulfonamide antibiotics in environmental water samples. J. Chromatogr. A 2018, 1586, 18–29. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Xiao, X.; Li, G. Porous molecularly imprinted monolithic capillary column for on-line extraction coupled to high-performance liquid chromatography for trace analysis of antimicrobials in food samples. Talanta 2014, 123, 63–70. [CrossRef]

- Ghanem, M., Abu-Lafi, S., Karaman, R., and Hallak, H. Validated HPLC Method to Simultaneously Determine Amprolium Hydrochloride, Sulfaquinoxaline Sodium and Vitamin K3 in A.S.K Powder on ZIC-HILIC Column. Pharmaceutica Analytica Acta 2012, 3, 1-6.

- Hu, F.-Y.; He, L.-M.; Yang, J.-W.; Bian, K.; Wang, Z.-N.; Yang, H.-C.; Liu, Y.-H. Determination of 26 veterinary antibiotics residues in water matrices by lyophilization in combination with LC–MS/MS. J. Chromatogr. B 2014, 949-950, 79–86. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, C.; Xu, Z.; Chakraborty, A. A coupled method of on-line solid phase extraction with the UHPLC‒MS/MS for detection of sulfonamides antibiotics residues in aquaculture. Chemosphere 2020, 254, 126765. [CrossRef]

- Tetzner, N.F.; Maniero, M.G.; Rodrigues-Silva, C.; Rath, S. On-line solid phase extraction-ultra high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry as a powerful technique for the determination of sulfonamide residues in soils. J. Chromatogr. A 2016, 1452, 89–97. [CrossRef]

- Wuethrich, A.; Haddad, P.R.; Quirino, J.P. Field-enhanced sample injection micelle-to-solvent stacking capillary zone electrophoresis-electrospray ionization mass spectrometry of antibiotics in seawater after solid-phase extraction. Electrophoresis 2016, 37, 1139–1142. [CrossRef]

- Mamani, M.C.V.; Amaya-Farfan, J.; Reyes, F.G.R.; da Silva, J.A.F.; Rath, S. Use of experimental design and effective mobility calculations to develop a method for the determination of antimicrobials by capillary electrophoresis. Talanta 2008, 76, 1006–1014. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Ngom, B.; Le, T.; Jin, X.; Wang, L.; Shi, D.; Wang, X.; Bi, D. Utilizing Three Monoclonal Antibodies in the Development of an Immunochromatographic Assay for Simultaneous Detection of Sulfamethazine, Sulfadiazine, and Sulfaquinoxaline Residues in Egg and Chicken Muscle. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 7550–7555. [CrossRef]

- Ellington, A.D.; Szostak, J.W. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 1990, 346, 818–822. [CrossRef]

- Tuerk, C.; Gold, L. Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment: RNA Ligands to Bacteriophage T4 DNA Polymerase. Science 1990, 249, 505–510. [CrossRef]

- Chuesiang, P.; Ryu, V.; Siripatrawan, U.; He, L.; McLandsborough, L. Aptamer-based surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) for the rapid detection of Salmonella Enteritidis contaminated in ground beef. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2021, 150. [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Duan, N.; Gu, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z. Fluorometric determination of lipopolysaccharides via changes of the graphene oxide-enhanced fluorescence polarization caused by truncated aptamers. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Zhang, J., Huang, Z., Yang, Y., Fu, T., Yang, Y., Lyu, Y., Jiang, J., Qiu, L., Cao, Z., Zhang, X., You, Q., Lin, Y., Zhao, Z., and Tan, W. Robust Covalent Aptamer Strategy Enables Sensitive Detection and Enhanced Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Proteins. ACS Central Science 2023, 9, 72-83.

- Sabrowski, W.; Dreymann, N.; Möller, A.; Czepluch, D.; Albani, P.P.; Theodoridis, D.; Menger, M.M. The use of high-affinity polyhistidine binders as masking probes for the selection of an NDM-1 specific aptamer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Stuber, A.; Nakatsuka, N. Aptamer Renaissance for Neurochemical Biosensing. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 2552–2563. [CrossRef]

- Song, W., Song, Y., Li, Q., Fan, C., Lan, X., and Jiang, D. Advances in aptamer-based nuclear imaging. European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2022, 49, 2544-2559.

- Pan, Z.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, Q.; Sun, Y.; Wu, E.; Wang, Y.; Shi, K.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; et al. Development of Uveal Melanoma-Specific Aptamer for Potential Biomarker Discovery and Targeted Drug Delivery. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 5095–5108. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Jiang, S.; Ren, Y.; Wang, S.; Xie, Y.; Le, T. High-efficient selection of aptamers by magnetic cross-linking precipitation and development of aptasensor for 1-aminohydantoin detection. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2024, 199. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Zheng, X.; Jiang, S.; Cao, M.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Nie, X.; Fang, Y.; Le, T. Dual fluorescent aptasensor for simultanous and quantitative detection of sulfadimethoxine and oxytetracycin residues in animal-derived foods tissues based on mesoporous silica. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 1077893. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Liu, J.; Ping, M.; Yang, W.; Fu, F. Isolation of aptamers with excellent cross-reactivity and specificity to sulfonamides towards a ratiometric fluorescent aptasensor for the detection of nine sulfonamides in seafood. Talanta 2024, 277, 126380. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., He, B., Liang, Y., Wang, J., Jiao, Q., Liu, Y., Guo, R., Wei, M., and Jin, H. Sensitive electrochemical aptasensor for determination of sulfaquinoxaline based on AuPd NPs@UiO-66-NH2/CoSe2 and RecJf exonuclease-assisted signal amplification. Analytica Chimica Acta 2021, 1182, 338948.

- Dai, J.; Li, J.; Jiao, Y.; Yang, X.; Yang, D.; Zhong, Z.; Li, H.; Yang, Y. Colorimetric-SERS dual-mode aptasensor for Staphylococcus aureus based on MnO2@AuNPs oxidase-like activity. Food Chem. 2024, 456, 139955. [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Huang, Z.; Ping, T.; Su, H.; Yang, Q.; Wu, W. Dual-mode aptasensors based on AuNPs and Ag@Au NPs for simultaneous detection of foodborne pathogens. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2023, 184. [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Khan, I.M.; Wang, Z. Research Progress of Optical Aptasensors Based on AuNPs in Food Safety. Food Anal. Methods 2021, 14, 2136–2151. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Dong, Y. Development of a chimeric aptamer and an AuNPs aptasensor for highly sensitive and specific identification of Aflatoxin B1. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2020, 319, 128250. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, R.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Sun, J.; Mao, X. Aptasensing a class of small molecules based on split aptamers and hybridization chain reaction-assisted AuNPs nanozyme. Food Chem. 2022, 401, 134053. [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, P.; Taghdisi, S.M.; Maghami, P.; Abnous, K. A novel aptasensor for colorimetric monitoring of tobramycin: Strategy of enzyme-like activity of AuNPs controlled by three-way junction DNA pockets. Spectrochim. Acta Part A: Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2021, 267, 120626. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-Y.; Huang, P.; Wu, F.-Y. A label-free colorimetric aptasensor based on controllable aggregation of AuNPs for the detection of multiplex antibiotics. Food Chem. 2019, 304, 125377. [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Kou, Q.; Wu, P.; Sun, Q.; Wu, J.; Le, T. Selection and Application of DNA Aptamers Against Sulfaquinoxaline Assisted by Graphene Oxide–Based SELEX. Food Anal. Methods 2020, 14, 250–259. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Yang, L., Tang, J., Wen, X., Zheng, X., Chen, L., Li, J., Xie, Y., and Le, T. An AuNPs-Based Fluorescent Sensor with Truncated Aptamer for Detection of Sulfaquinoxaline in Water. Biosensors 2022, 12, 513.

- Yang, L.; Chen, X.; Wen, X.; Tang, J.; Zheng, X.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Jiang, S.; Le, T. A label-free dual-modal aptasensor for colorimetric and fluorescent detection of sulfadiazine. J. Mater. Chem. B 2022, 10, 6187–6193. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Han, Y., Sun, Q., Cheng, J., Yue, C., Liu, Y., Song, J., Jin, W., Ding, X., de la Fuente, J. M., Ni, J., Wang, X., and Cui, D. Au-siRNA@ aptamer nanocages as a high-efficiency drug and gene delivery system for targeted lung cancer therapy. Journal of Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 54.

- Hu, J.; Ni, P.; Dai, H.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Li, Z. Aptamer-based colorimetric biosensing of abrin using catalytic gold nanoparticles. Anal. 2015, 140, 3581–3586. [CrossRef]

- Hizir, M.S.; Top, M.; Balcioglu, M.; Rana, M.; Robertson, N.M.; Shen, F.; Sheng, J.; Yigit, M.V. Multiplexed Activity of perAuxidase: DNA-Capped AuNPs Act as Adjustable Peroxidase. Anal. Chem. 2015, 88, 600–605. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Tian, Y.; Huang, P.; Wu, F.-Y. Using target-specific aptamers to enhance the peroxidase-like activity of gold nanoclusters for colorimetric detection of tetracycline antibiotics. Talanta 2020, 208, 120342. [CrossRef]

- Ngom, B.; Guo, Y.; Jin, X.; Shi, D.; Zeng, Y.; Le, T.; Lu, F.; Wang, X.; Bi, D. Monoclonal antibody against sulfaquinoxaline and quantitative analysis in chicken tissues by competitive indirect ELISA and lateral flow immunoassay. Food Agric. Immunol. 2011, 22, 1–16. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Luo, X.; Li, Y.; Yang, H.; Liang, X.; Wen, K.; Cao, Y.; Li, C.; Wang, W.; Shi, W.; et al. A Class-Selective Immunoassay for Sulfonamides Residue Detection in Milk Using a Superior Polyclonal Antibody with Broad Specificity and Highly Uniform Affinity. Molecules 2019, 24, 443. [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Sheng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Wang, S. Upconversion Nanoparticles and Monodispersed Magnetic Polystyrene Microsphere Based Fluorescence Immunoassay for the Detection of Sulfaquinoxaline in Animal-Derived Foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 3908–3915. [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Yan, P.; Liu, J.; Wei, S. Simultaneous detection of sulfamethazine and sulfaquinoxaline using a dual-label time-resolved fluorescence immunoassay. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2013, 30, 1264–1269. [CrossRef]

- Soleymanpour, A.; Rezvani, S.A. Development of a novel carbon paste sensor for determination of micromolar amounts of sulfaquinoxaline in pharmaceutical and biological samples. Biomater. Adv. 2015, 58, 504–509. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).