Introduction

The West African countries commonly known as the ECOWAS nations have abundance natural resources (NR) that can be used for economic development, yet they are wallowing in energy poverty (EP) crisis. The abundance of NR in this region means that these countries have a variety of energy sources (renewable energy (RE) and non-renewable energy (NRE)), such as wind energy, solar energy, hydro energy and coal that can be utilised to lower EP. Moreover, the availability of abundance NR enable these nations to generate income (NRR) through the sale of these NRs; hence, use it towards improving energy affordability and accessibility. Energy is key to life and is important in supporting the standards of living of citizens through raising the national income as it supports economic growth (Deka et al., 2023). Recent studies have presented energy as a key determinant of economic development, that can be seen as a factor of production (Kadir et al., 2023). Moreover, energy is essential in providing street lighting, lighting up houses and industries, powering household appliances, machineries in the industries and for cooking at home (Casati et al., 2023). Therefore, considering the importance of energy in different realms of life, promoting energy accessibility and affordability in the economies becomes paramount. This is so because the lack of energy accessibility and affordability is what is generally considered as energy poverty (Gonzalez, 2023). Moreover, it is also key to note that energy poverty is witnessed when polluting energy sources are used, rather than clean sources and this is the case of the ECOWAS rural areas and most of the rural areas in Africa. Polluting energy sources harms and degrades the environment; hence, does not encourage sustainable development (Deka, 2024). Examples of polluting energy sources used in the ECOWAS nations and various other African nations especially in the rural areas include coal, firewood and charcoal. Examples of cleaner energy sources include electricity especially from RE sources and natural gas. These are relatively expensive and can be afforded by high-income earners than low-income earners.

The data of the World Bank (WB) clearly shows the energy poverty problems experienced in the ECOWAS nations.

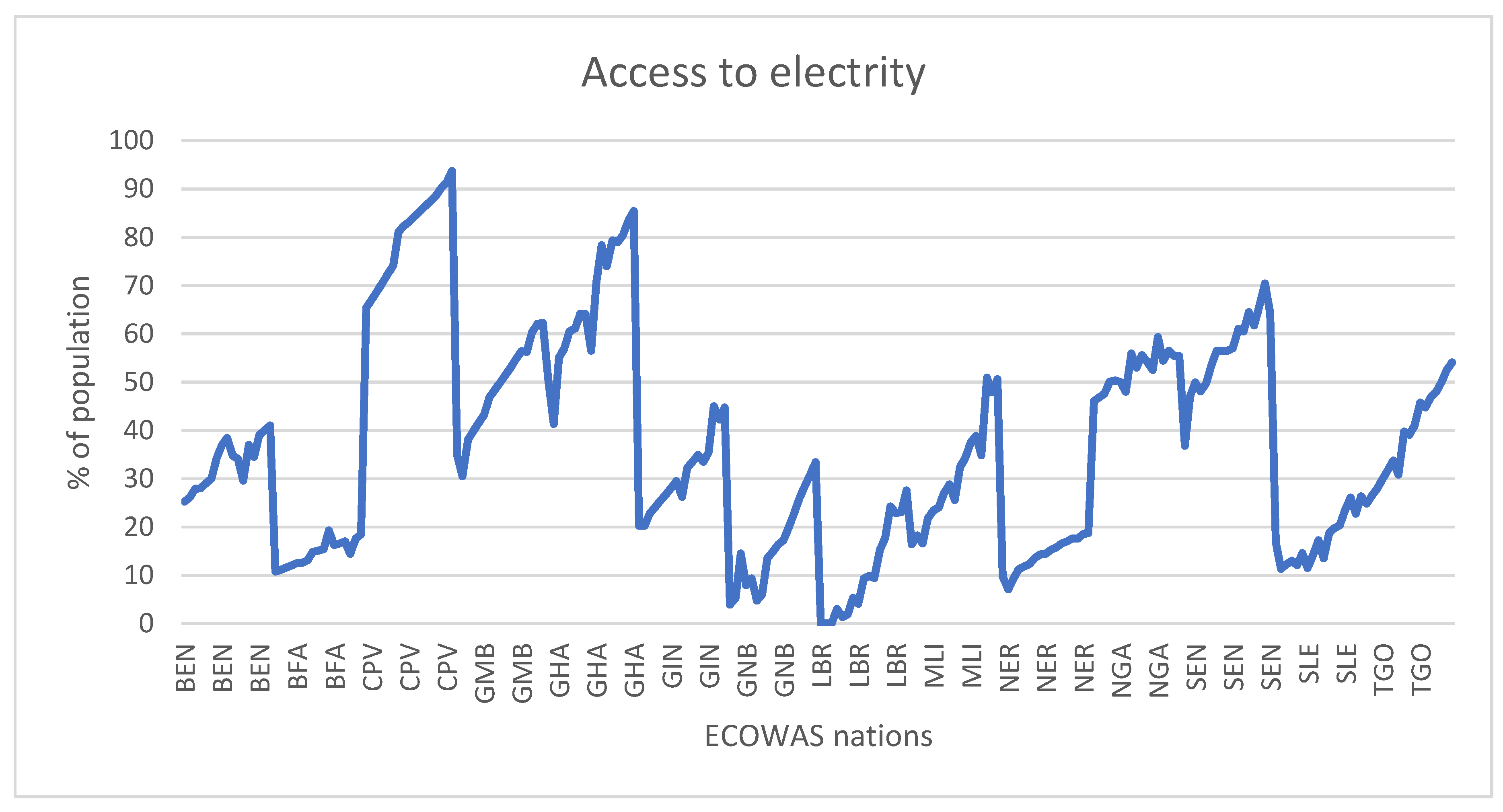

Figure 1 developed with the World Bank data for the period 2004 to 2020 of the ECOWAS nations shows that most of the nations in this region have problems of access to electricity (AE, henceforth).

Figure 1 shows that the ECOWAS nations with AE as a percent of the population that is above 50% include Cape Verde, Ghana, Senegal and Gambia. The remaining ECOWAS nations represents AE of below 50% depicting the existence of energy poverty issues in this region. Energy poverty is a serious issue that culminates in the rising poverty levels in a country. One of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) is energy poverty reduction and the access to affordable and clean energy. Therefore, it is imminent for the ECOWAS countries to ensure a long-lasting solution in reducing energy poverty is developed; hence, poverty reduction is achieved too.

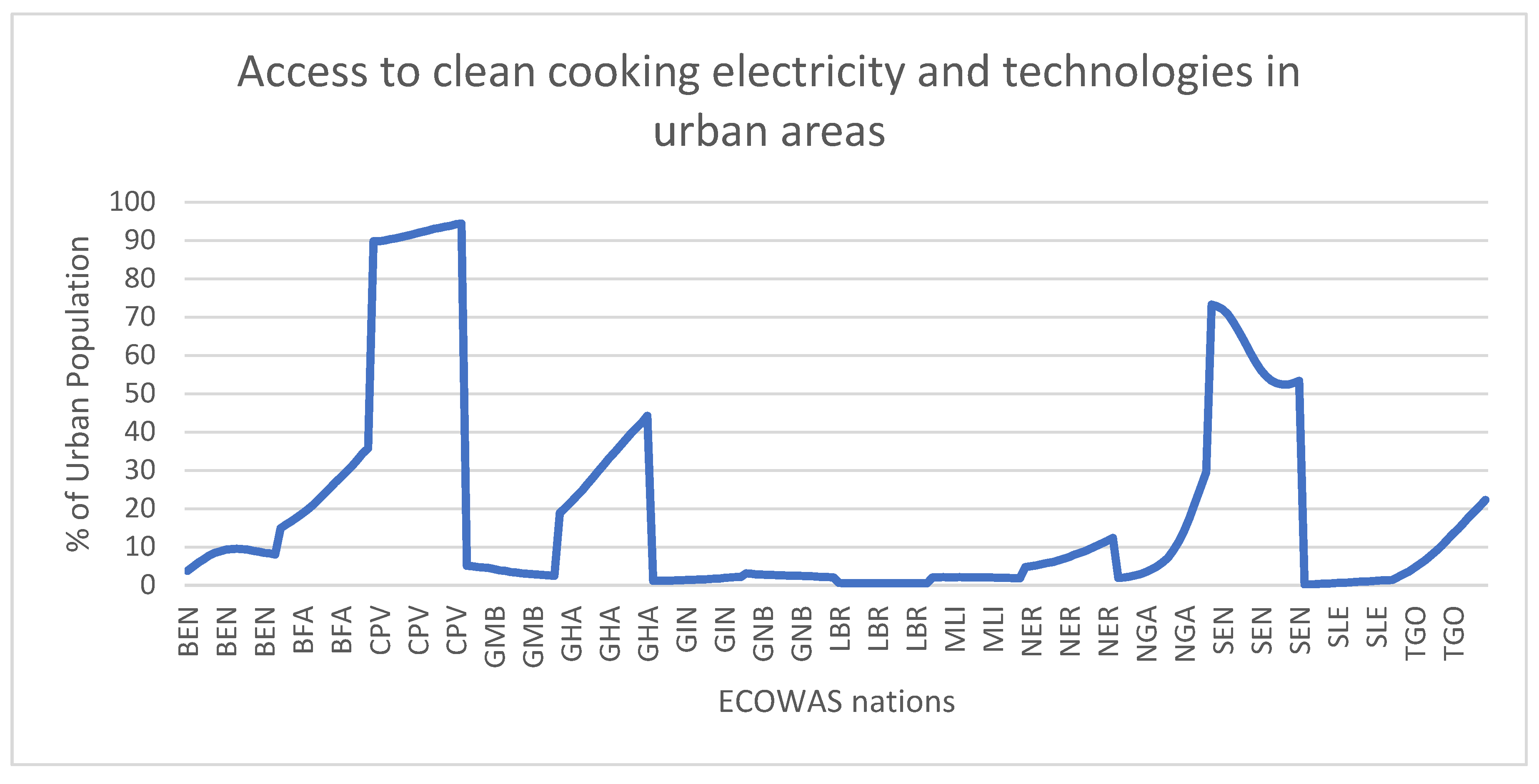

Moreover, the information presented in

Figure 2 extends in showing the extent of energy poverty in the ECOWAS countries.

Figure 2 depicts that ‘access to clean cooking electricity and technologies in urban areas’ (ACU, henceforth) as percent of urban population in the ECOWAS nations is below minimum. Cape Verde and Senegal only ECOWAS nations with ACU that is above 50%. Some ECOWAS countries have ACU that is way below 10%, for example, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone and Benin. The Urban areas are the most populated areas than the rural areas, considering the population density per square meter. Abrahams (2020) is of the postulations that energy affordability and accessibility is paramount in areas of high population density. In these areas, clean electricity is paramount to ensure the healthy systems are not jeopardised. Thus, the lack of clean energy in the urban areas of the ECOWAS nations is worrisome. Therefore, it is imminent for the ECOWAS nations to consider seeking solution to energy poverty issues in their region. Various avenues can be considered such as considering the harnessing the NR that are abundance in these countries and use them to support energy accessibility. However, developing nations are always associated with what is termed the ‘resource curse’ emanating from the high corruption and political instabilities problems leading to these countries failing to advance economic development. Thus, innovative studies that are instrumental in informing policies on how energy-poverty-reduction strategies can be developed are needed.

This research is one of the first attempts to address energy poverty in the ECOWAS countries through developing an energy poverty gap (EPG) proxy that can accurately represent energy poverty than using indicators like access to electricity as seen in various studies that have attempted to address energy poverty issues in various regions. This research adopts the EPG presented in Wang and Du (2024), and focusses on energy accessibility than affordability and production because of limitations in the data availability for the nations under consideration. Thus, the AE and ACU are employed to develop the energy poverty index with the geometric mean and then subtracted from 100% to show the gap in energy poverty. Just like Wang and Du (2024), this research bases its research model on the two key theories on energy poverty, that is, energy ladder and stacking. These theories are important especially when studying energy poverty in the developing nations. The energy ladder theory divides energy sources into low- and high-ladder sources, where charcoal and other convectional fuels are categorised as low-ladder fuels, while natural gas and electricity are categorised as high-ladder fuels. Li et al. (2023) shows that the energy stacking theory explains the existence of multi-ladder phenomenon where both low- and high-ladder sources are used interchangeably. This is the case of developing nations where low- and high-ladder sources of energy can be used together because of energy use habits and the cost of high-ladder energy. Moreover, this research novelty is in the consideration of the interplay of green finance (GF), economic growth, technological innovations (TI), foreign direct investment (FDI) and NRR in lowering energy poverty problems in the ECOWAS nations. The importance of these factors is supported in the energy ladder theory that has depicted the significance of income and technology is promoting energy affordability and accessibility. Lastly, through using the ‘Methods of Moments Quantile Regression (MMQR)’ results that are fundamental in informing policies on reducing energy poverty in the ECOWAS nations are presented. The MMQR method is key in panel data analysis because it overcomes various problems associated with panel data, such as ‘Cross-sectional dependence (CD)’, ‘heterogeneity’ and dynamics, and allows asymmetric effects to be examined through allowing heterogeneous outcomes to be presented (Machado & Silva, 2019).

Literature Gap and Contribution

The ECOWAS countries are associated with high-levels of energy poverty because of the lack of affordable and clean electricity both in the rural and urban areas. Therefore, considering the importance of energy in the advancements of economy as highlighted in the introduction section above, it is vital for the ECOWAS countries to come up with some policies that can ensure advancements in the production accessibility and affordability of energy in this region; hence, lowering energy poverty levels. To devise some policies necessary to reduce energy poverty in the ECOWAS countries, it is fundamental to present state-of-the-art studies that investigates into the various mechanism that can be employed to alleviate energy poverty in this region. While such studies are imminent in the ECOWAS region, literature lacks studies that specifically investigates energy poverty in the ECIWAS region. Therefore, this study is one among the first attempts presented in the literature to examine energy poverty in the ECOWAS countries and hence present crucial policies needed to improve the well-being of the society in this region. In this section, we present findings of various studies that have examined energy poverty in the African countries, though these studies does not specifically concentrate on the ECOWAS countries. Studies that have examined energy poverty in other regions of the world are also investigated to identify the gaps that are existing in the literature and hence attempt to cover these gaps by contributing to the existing literature.

The evidence that is presented in the literature have shown the existence of long-term implications of energy poverty on social and economic progress of countries, their health systems, as well as the sustainability of the environment (ES), Katoch et al. (2023); Feng et al. (2023). Therefore, considering the strong implications of energy poverty on the various aspects of life such as economic development, health prospects and sustainability it is vital for nations to consider addressing energy poverty by improving the accessibility and affordability of electricity among their countries. Stewart et al. (2023) specifically show that addressing energy poverty problems requires comprehensive techniques that are vigorous and effective in ensuring positive outcomes to the society. The health outcomes have been observed to be worsened by energy poverty as the citizens may end up turning to the utilization of polluting energy sources such as firewood, coal and charcoal, where accessibility of clean fuels is not available. Using these traditional and polluting energy sources degrades the environment and causes the widespread of diseases thereby deteriorating the health outcomes in the country. According to Dimnwobi et al. (2023b), the African countries are heavily relying on the utilization of solid biomass energies in cooking, both in the rural and urban areas where energy poverty problems are present; hence, resulting in the deterioration of the environment as these pollutants are emitted into the environment. Environmental deterioration is a serious problem in most of the world economies and to this date immediate action is being called for to find ways and work towards improving the surroundings. The studies done on this subject have shown that the utilization of renewable energy (RE) is recommended in order to ensure the environment is not further damaged (Banga et al., 2022; Akpanke et al., 2023). The damaging effects of using solid biomass fuels in the African countries, on the environment, has been supported by various empirical studies that have been undertaken and presented in this field (Dimnwobi et al., 2023b; Boluwaji Elehinafe et al., 2023). However, while the utilization of REs recommended in the world economies, drawbacks in achieving a transition to its use have been observed due to the exorbitant nature of these sources of energies (Deka & Dube, 2021).

While some could have addressed the subject of energy poverty in the African countries empirical past studies it is observed that these studies focused in addressing energy poverty by employing some indicators that can be used to proxy energy poverty such as the accessibility of energy among others. Thus, most of the policies that have been presented in the literature are based on the individual indicators that represents energy poverty in this region. Dimnwobi et al. (2023a) investigated energy poverty in the cities of the African countries and recommended advancements in the accessibility of clean fuels for cooking in the urban areas of the African nations in order to ensure the reduction of energy poverty in the region. The recommendation presented in Dimnwobi et al. (2023a) is supported by the postulations of Ahmed et al. (2023) who has highlighted the urgency in addressing and improving clean cooking fuel accessibility in the cities of African nation. Urbanization is on the rise in the world and the African nations are not an exception; hence, increasing the demand for fuels in the urban areas, which further worsens energy poverty in the African countries. The increase in urbanization in the African countries has specifically led to the rise in the development of informal settlements in the cities, which has led to the emergence of unique energy poverty challenges in this region (Khavari et al., 2023). Considering these unique challenges on energy poverty that are arising as a result of rising urbanization and informal settlements in the cities in the African countries, there is need to devise special techniques that are sophisticated and advanced to efficiently and effectively reduce energy poverty. Devising such techniques requires empirical studies that provides robust results and hence informed policies to be undertaken. Therefore, the present research is one of the attempt to consider the ECOWAS countries and device some mechanisms that can be used specifically for this part of the African region in lowering energy poverty problems.

According to Tsai et al. (2023), the process of addressing energy poverty requires the development of a comprehensive approach that puts into consideration the engagement with the community, policy frameworks, financial techniques, as well as technological mechanisms. Furthermore, Okere et al. (2023) is of the postulations that policies that are poorly formulated in a move towards addressing energy poverty tends to hinder the production of RE. This is supported in the empirical study of the European Union (EU) that is presenting evidence indicating that green transition policies in this region have been worsening energy poverty (Belaid, 2022b). Therefore, countries should ensure that the green energy transition policies are properly designed and can vigorously improve the use of RE without worsening the lack of energy accessibility and affordability. Thus, there is need for the ECOWAS countries to properly devise policies that are meant to improve energy accessibility and affordability while maintaining improvements in the production of RE. RE is crucial in ensuring the level of pollution presented in the environment is lowered; hence, promoting the attainment of ES in the countries (Deka et al., 2024). It is also worrisome that new forms of inequalities on income are emerging due to scarcity of energy in the economy, Song et al. (2023). To solve the problems in the inequalities that are arising due to the problems of energy scarcity it is important to devise policies that are vigorous and are formulated properly (Belaid, 2022b).

Moreover, Belaid (2022b) postulates that skyrocketing energy prices in the EU nations is further worsening energy poverty in this region. The rising energy prices are associated with increases in the expenses of low-income earners that are utilizing more of energy sources in Egypt (Belaid & Flambard, 2023). Where energy poverty is arising from increases in the prices of energy, price controls on energy sources by the government becomes an alternative solution. Additionally, policies towards improving the national income of the country while ensuring the disposable income of households is raised become key in alleviating energy poverty. This is supported in the empirical study of Belaid (2022a), which has shown that stabilization of the economy, improvements in the educational systems, as well as improvement in the national income from economic stabilization can significantly address the problem. When the educational system is improved, human capital is advanced thereby improving the employment levels of the citizens; hence, households’ income is raised. Empirical studies have shown that when human capital increases, citizens tends to substitute polluting fuels with cleaner fuels due to improved energy affordability arising from increased incomes; hence, ES is maintained (Quito et al., 2023; Van Der Kroon et al., 2013). Human capital also promotes efficient exploitation of NR with the use of sophisticated technologies and increases in energy efficiency; hence, eradicate energy poverty problems (Zafar et al., 2019). The problems with the ECOWAS countries emanate from the poor educational system, leading to poor human capital and the lack of technological innovations in this region to advance energy accessibility and affordability. Therefore, by examining on how different factors affects energy poverty in the ECOWAS countries the development of different mechanisms through well-informed policies to address this issue is guaranteed.

Materials and Methods

Theoretical Framework

The famous theories of energy poverty are the “Energy ladder” and “Energy stacking” theories (Wang & Du, 2024). Zafar et al. (2019) that efficient exploitation of NR could be accomplished with well-skilled and educated human capital that will encourage societies to utilize technologies that are energy efficient. Increasing educational opportunities will lead to higher chances of households being employed, therefore raising their income, which will help to deal with energy affordability. Thus, with the increase in income, energy will be more accessible and affordable. In addition, human capital might influence energy poverty via the theory of the “energy ladder”. The theory posits that with the income increase, households will be triggered to substitute conventional fuel utilization with modern and sustainable sources (Quito et al., 2023; Van Der Kroon et al., 2013). Therefore, the rise in households’ income would trigger the transition to clean energy utilization and reduction in energy poverty.

According to the energy ladder theory, low-ladder sources of energy include charcoal, wood, and coal, which are readily available in developing countries. The high-ladder sources of energy include natural gas and electricity and these can easily substitute the low-ladder sources of energy in developed nations (Wang & Du, 2024). In developing nations, due to a lack of urbanization, these two forms of energy may coexist. Wang and Du (2024) articulate that even if natural gas and electricity may be available in developing countries, low-ladder sources will still be used by households because of various reasons such as the habits of energy use and the cost of the high-ladder sources. When this situation occurs then the multi-ladder overlap phenomenon is said to be present and thus the emergence of the energy stacking theory (Dong et al., 2023). Thus, in the context where different ladders exist, the conventional measurement of energy accessibility is ineffective (Li et al., 2023).

From the postulations of the Energy ladder and stacking theories, this study presents the model on energy poverty that takes technology, economic growth, NRR, FDI and green finance as the explanatory factors. This is so because technology is important in supporting energy poverty according to the postulations of Zafar et al. (2019). In the same lines, green finance improves R&D on clean technologies and in advancing RE, hence reduces energy poverty. Moreover, economic growth measures the national income of the country that is vital in providing energy; hence reduce energy poverty. FDI and NRR helps in generating the income that can be useful in alleviating the problem of energy poverty. The research model is presented as shown in Equation 1.

In this Equation EP is used to represent energy poverty; TI, is technological innovations; EG, is economic growth; GF, green finance; NRR, natural resources rents; FDI, foreign direct investment. Moreover, is the constant; is the error term; to are the coefficients; while the superscripts are representing the cross-sections and the time period.

Data

The data used in the analysis of this research is for the fourteen ECOWAS countries and the time period considered is for the 2004 to 2020 period. It is annual data for the said countries. This research calculates the energy poverty gap (EPG) index to represent the energy poverty in the ECOWAS nations. To calculate the energy poverty gap, we first calculate the energy poverty index (EPI) from access to electricity (AE) and ACU according to the data available in the ECOWAS countries. ACE and AE are both measured as a percent of the population. Some studies have further used energy production and consumption, but since the data on the production of energy is not readily available, the accessibility of energy is used in this research. The geometric mean is used to calculate the EPI from ACE and AE, and then subtract the EPI from hundred to obtain the EPG ().

The economic growth is the percent change in the GDP of a country, that is, the growth rate in the GDP. FDI inflows as a percent of GDP and the revenue generated from selling the NR of the nation is used and is the NRR. Moreover, the money given to developing nations for supporting R&D on RE and clean technologies of the Our World in Data (OWID) is utilised to represent green finance. ‘Fixed Broadband Subscription’ (FBS), ‘Mobile Cellular Subscription’ (MCS) and the ‘internet usage’ (IU) are used to develop an aggregated index of the technological innovations. This is achieved with the ‘Principal Component Analysis’ (PCA) method. MCS and FBS are measured per hundred persons and the IU is measured as percent of the population. In summarizing the measurements of the variable used and their sources, the information is given in

Table 1. Moreover, the descriptive statistics given in

Table 2 summarizes the measures of dispersion of the indicators specified in the model.

Method

This research uses the MMQR technique to overcome ‘cross-sectional dependence (CD)’, ‘heterogeneity’, and dynamics in the model (Deka, 2024). CD is tested in the indicators with the Pesaran (2004) test, which enables us to use the CIPS method of Im et al. (2003) to test unit root (UR) where CD is present, and in the model with the Frees (1995; 2004), Friedman (1937) and Pesaran (2015) methods. Moreover, the ‘slope heterogeneity’ method is used to check ‘heterogeneity’ (Pesaran & Yamagata, 2008). Additionally, the MMQR method is used because of the existence of long run (LR) association presented through the cointegration tests of Kao and Pedroni methods because it presents heterogeneous outcomes in different quantiles. Lower quantiles present short run (SR) findings while upper-quantiles presents LR findings. The MMQR technique is adopted in various recent studies and is recommended for presenting reliable outcomes and showing investigating asymmetries on the link among the independent factors and the dependent factor. The MMQR statistical Equation is shown in Equation 2.

In Equation 2, is the conditional quantile of the explained variable, while the factors on the right hand side of the equation are similar to those explained in Equation 1.

Results

Pretesting Outcomes

This section presents the findings of the CD techniques in order to ascertain if the variables have CD problems; hence, determine the method to be used in analyzing the UR. Moreover, in this section the model is tested for ‘multi-collinearity’ in order to ascertain if the independent variables employed are not strongly related; hence, robust results could be presented. We also present the results of the ‘heterogeneity’ test. In this section, the results of the cointegration, as well as the results of the ‘weak CD’ test in the model. All these tests are important to ascertain the most appropriate method that can be used to analyze the relationship specified in the model of this study.

The CD findings show that all the factors specified in the model exhibit significant (sig.) CD.

Table 3 depicts that the indicators specified in the model are sig. at 5% and 1%; hence, the presence of strong CD in these panel variables.

In order to overcome CD that is depicted in the variables, according to the findings presented in

Table 3, this research utilizes the SG method in order to present robust results on the stationarity of the indictors. To this end, the CIPS method is employed and the findings are shown in in

Table 4.

Table 4 depicts that the factors used in this analysis are I(0) and I(1) since the indictors are observed to be stationary at level, while the other indicators are observed to be stationary after differencing them once.

Table 4 depicts that EPG, FDI, economic growth and green finance are I(0), whereas TI and NRR are I(1). After having shown that the indicators used in this analysis exhibit mixed integration orders, the methods of analysis that works with variables that have mixed integration orders are selected and used.

The VIF test detects ‘multi-collinearity’ in the model and ensures robust findings are presented without allowing strongly related independent variables to be specified in the same model.

Table 5 depicts that no ‘multi-collinearity’ is present in the independent indictors.

It is also necessary to test if the model exhibits sig. cointegration; hence, be able to ensure that the LR connection is examined in the analysis.

Table 6 depicts that strong LR relationship is present in the model. This is supported by the findings of the two methods employed, the Kao and Pedroni; hence, presenting strong evidence on the existence of a LR relationship. Therefore, the analysis that is carried out in this study to ascertain the relationship specified in the research model will consider presenting the LR results by employing a method that is the capacity to do so.

In addition, the ‘slope heterogeneity’ method employed to examine ‘heterogeneity’ in the model show that the problems of ‘heterogeneity’ are present in the model.

Table 7 depicts that the Delta Statistics is sig. and the adjusted delta statistics is also sig. This test is fundamental in informing the researcher to utilize the SG method in the analysis of the model because SG methods tends to overcome this problem.

Finally, in the pretesting analysis of the model the ‘weak CD’ results are presented as shown in

Table 8.

Table 8 depicts that the model exhibit a sig. ‘weak CD’ problem since all the three test methods employed concurs that ‘weak CD’ is present. The ‘weak CD’ results presented are essential in informing the researcher to consider the utilization of the SG methods for the purpose of overcoming this problem.

MMQR Results and Discussion

In this research, we present the empirical findings for the model specified in section 3 by employing the MMQR method that provides LR results, overcomes ‘weak CD’ and ‘heterogeneity’ that has been observed in the section above. It is also important to note that the MMQR method ensures the asymmetric effects of the independent factors on the dependent factor is examined by giving results that are heterogeneous in different quantiles.

The findings presented depict that TI and EP in the ECOWAS countries exhibit a sig. negative connection.

Table 9 shows that raising TI results in a sig. decrease in the EP in these countries. The increase in TI by a single unit results in a decrease in EP in the ECOWAS countries by a magnitude of 20.95 units to 17.19 units in the 0.1 to the 0.9 quantiles. The influence of TI on EP is strong as depicted by the sig. at 1% in all the quantiles and is also symmetric showing that all ECOWAS countries, regardless of their level of EP tends to benefit from TI in abating the problems of EP. Moreover, the sig. and negative effect of TI on EP in the ECOWAS countries in all the quantiles is an indication that EP is reduced through TI in the SR as well as in the LR. Therefore, it is important to propose some policies that encourages the ECOWAS countries to advance technologies that ensures improvement in energy production; hence, reduce the problem of EP in this region. The importance of TI in lowering EP in the ECOWAS nations is supported by the energy ladder theory of energy poverty. In this theory, the utilisation of advanced technologies emanating from human capital is found to raise clean energy affordability (Quito et al., 2023; Van Der Kroon et al., 2013). Therefore, the ECOWAS nations should adopted mechanisms that allows it possible to advance technologies and ease the problem of EP.

Moreover,

Table 9 depicts that GF significantly reduce EP in the ECOWAS countries only in the 0.1 to the 0.5 quantiles. The results of the 0.75 quantile and 0.9 quantile are not sig., though the 0.75-quantile results are negative depicting that GF in this quantile reduces EP, but the 0.9-quantile results are positive depicting that GF increases EP. Thus,

Table 9 depicts that an increase in GF by 1% lowers EP in the ECOWAS countries by 1.47% to 0.15% in the 0.1 to 0.5 quantiles. Therefore, GF present asymmetric effects on the EP of the ECOWAS countries. ECOWAS countries with low EP problems tend to benefit from GF to alleviate EP in their countries, whereas ECOWAS countries with high-EP do not significantly benefit from EP to reduce the problems of EP. We can also show in these results that GF is important in supporting the reduction of EP in this region only in the SR and in the LR the influence of GF on EP becomes insignificant (insig.). However, because of the importance of GF in reducing EP in the lower quantiles, this study recommends the utilization of these funds that are received to support the R&D towards the advancements of new technologies and new clean fuels in order to alleviate EP in this region. The importance of GF in alleviating EP is clear because GF is devised to support developing nations in the R&D meant to advance RE and technologies that are clean (Our World in Data, 2024). However, in empirical study of Deka and Efe-Onakpojeruo (2024) GF is observed to lower the accessibility of energy sources in the African region; hence, causing EP to rise. The detrimental influence of GF on EP in the African region has been explained by the corruption that is more in these nations; hence, causing the existence of the ‘resource curse’ (Auty, 1994; Deka & Efe-Onakpojeruo, 2024)

Furthermore, the results presented depicts the importance of economic growth in a reducing EP in the ECOWAS countries in all the quantiles.

Table 9 presents a sig. negative effect of economic growth on EP in all the quantiles showing that economic growth symmetrically reduces EP in this region. The findings presented show that an increase in the economic growth by a single unit can reduce EP by an average of 1.47 units to 0.39 units in the 0.1 to the 0.9 quantiles, respectively. These findings show that the ECOWAS countries with high-EP problems or with low-EP problems can capitalize on economic growth to support the improvement in its energy resources; hence, lowers the problems of EP. Additionally, this also shows that EP is decreased through the utilization of national income in both SR as well as in the LR in this region. The past studies of Bai and Liu (2023) have shown that EP is lowered with the improvements in the growth of economies. This shows the need for the ECOWAS countries to advance and improve national income of their nations. With increased national income in nations, households’ disposable income is greatly increased and this will enable them to afford and access energy. Quito et al. (2023); Van Der Kroon et al. (2013) have supported the importance of income among citizens in ensuring the affordability of energy and hence promotes the transition from conventional fuels that pollutes the surroundings to cleaner fuels. This is also supported in the energy ladder theory. Therefore, these findings are important in informing policies in the ECOWAS nations.

Table 9. also depicts that the effect of NRR on EP in the ECOWAS countries is positive in the 0.5 to the 0.9 quantiles. The findings also depicts that in the lower quantiles such as the 0.1 and 0.25, the effect of NRR is insig., but the 0.1 quantile shows a negative relationship and the 0.25 quantiles show a positive relationship. Through raising NRR by one-unit in the 0.5 to 0.9 quantiles, the findings presented in

Table 9 depicts that the EP of the ECOWAS countries increases by 0.33 to 0.48 units, respectively. These outcomes clearly shows the presence of asymmetric effects of NRR on the EP in this region. Thus, ECOWAS countries with low-level EP problems are not significantly impacted by NRR in alleviating EP but ECOWAS countries with high-EP problems are worsened in their EP through increases in the NRR. These findings support the RC theory showing that nations, especially the developing ones, receive little benefits from the abundance of NR in their countries to support the development of their economies (Auty, 1994). More empirical outcomes supports the RC theory in the developing nations; hence, supporting the findings presented in this study (Sha, 2023; Khan et al., 2023). Moreover, the scarcity of the NR, as shown by the high rents (Hussen, 2000), EP in the countries becomes acute. However, Deka and Efe-Onakpojeruo (2024) presents that NRR improves the accessibility of energy for cooking in the African nations. The differences observed with the present study can be explained by the use of different proxies of EP and the different regions examined. This research examines this connection in the ECOWAS countries and through calculating the EP gap, while Deka and Efe-Onakpojeruo (2024) examines the connection in all SSA countries with the use of cooking energy accessibility. Therefore, the ECOWAS countries are required to devise vigorous policies that reduces corruption and instabilities in this region in order to ensure EP reduction with NRR.

Table 9 shows that FDI does not significantly affect EP in the 0.1; 0.25; 0.5 and 0.9 quantiles, while it presents a sig. positive influence on EP in the 0.75 quantiles. The effect presented in the 0.75 quantile of FDI on EP is not strong as illustrated by a sig. level at 10%. Based on the results of the 0.75 quantile, increasing FDI by one-unit in this quantile increases EP by 0.089 units. While asymmetric effects of FDI on EP are observed in the results shown in

Table 9, it is evident that FDI is detrimental to the continuous rise in the EP of the ECOWAS countries. Deka and Efe-Onakpojeruo (2024) supports the increase in FDI that is associated with increased EP. In the SSA nations, the same findings are presented depicting that raising FDI can make the accessibility of cooking energy to decrease in the SSA nations, Deka and Efe-Onakpojeruo (2024). Thus, these countries does not benefit from the inflows of FDI from foreigners rather this tends to worsen the EP situation in these countries. However, a number of empirical outcomes given in literature on this connection show that nations can benefit is solving EP problems with encouraging FDI (Magnani & Vaona, 2016; Sarkodie & Adams, 2020). Thus, in the SSA nations and its sub-region of the ECOWAS nations, rising FDI that is linked with the worsening in the EP situation in this region is because foreign investment in these nations does not usually benefit the nation as a whole. This call for vigorous policies to ensure that the income raised from FDI are used for the betterment of the economy.

Conclusion

In short, this study provides the very important insights that can be used to improve energy resources in the ECOWAS countries and hence lower the problem of EP in this region. It articulates the factors that are necessary to be improved in the ECOWAS region so that these countries can overcome the problem of EP. The study also show the various factors that are worsening EP in this region; hence, in calling for policy makers to try, stabilize such factors; hence, lowers EP. To this end, this study presents three major themes and two subthemes from the findings presented in the analysis. Firstly, through employing the MMQR method the study show that it is fundamental for the ECOWAS countries to ensure advancements in technology and to promote TI in order to lower EP in these countries. The importance of technological advancement in increasing energy production and consumption in the ECOWAS countries is supported in all the quantiles; hence, it’s important in alleviating EP in all the ECOWAS countries. Secondly, the study findings show the importance of GF in lowering EP in the ECOWAS countries; hence, calling for these countries to capitalize on these international finances and advance R&D there is specific elements to improve clean energy sources and clean technologies thereby leading to lower EP problems in this region. Specifically, this study show that the ECOWAS countries with long- to medium-EP problems benefits from GF, while ECOWAS countries with high-level EP cannot advance their energy resources through GF. Thirdly, EP in the ECOWAS countries can be reduced through the advancements in the economic growth of these countries. With high-levels economic growth, these countries can use the national income generated in the country to support energy production and consumption; hence, lowering EP problems. Fourthly, NRR in the ECOWAS countries worsens EP in the middle- and upper-quantiles, an indication that the RC is present in these countries. Thus, the abundance of NR in the ECOWAS countries is not fundamental in reducing EP problems in this region. Fifthly, FDI is not fundamental in increasing energy production and use but rather tends to increase EP. Therefore, the inflow of national foreign income from foreign investors cannot be relied upon in the ECOWAS countries.

While this research focuses on the EP of the ECOWAS countries, the insights presented in this research can be extended to the whole region of the SSA countries. This is so because most of the SSA countries are facing challenges of EP and have the same level of income. They also have abundant NR and almost similar level of technology. Thus, all SSA countries are recommended to capitalize on economic growth, GF and TI in order to solve the problem of EP in their countries. The RC indicated in the results, in these countries with abundance resources can be corrected through the reduction in the political instabilities and the level of corruption. The novelty of the study is in both the conceptual framework, as well as the practical implications on how EP can be elevated in the ECOWAS countries considering the very few studies present in the literature addressing this problem. While this study addresses the various factors to be considered by policymakers in alleviating EP in this region, various questions remain unanswered on why NRR tends to increase EP when the energy sources comes from these NR. Thus, future studies can explore various reasons for the detrimental effect of NRR on the EP in these countries. It is natural to expect NRR to reduce EP, since abundance NR means the availability of abundance energy sources like coal and many other REs.

References

- Abrahams: D. (2020). Conflict in abundance and peacebuilding in scarcity: Challenges and opportunities in addressing climate change and conflict. World Development, 132, 104998. [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A., Boahen Asabere, S., Adams, E. A., & Abubakari, Z. (2023). Patterns and determinants of multidimensional poverty in secondary cities: Implications for urban sustainability in African cities. Habitat International, 134, 102775. [CrossRef]

- Akpanke, TA, Deka, A., Ozdeser, H., & Seraj, M. (2023). The role of forest resources, energy efficiency, and renewable energy in promoting environmental quality. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment , 195 (9), 1071. [CrossRef]

- Auty, R. M. (1994). Industrial policy reform in six large newly industrializing countries: The resource curse thesis. World development, 22(1), 11-26. [CrossRef]

- Bai, R., & Liu, Y. (2023). Natural resources as a source of financing energy poverty reduction? Resources extraction perspective. Resources Policy, 82, 103496. [CrossRef]

- Banga, C., Deka, A., Kilic, H., Ozturen, A., & Ozdeser, H. (2022). The role of clean energy in the development of sustainable tourism: does renewable energy use help mitigate environmental pollution? A panel data analysis. Environmental Science and Pollution Research , 29 (39), 59363-59373. [CrossRef]

- Belaïd, F. (2022a). Mapping and understanding the drivers of fuel poverty in emerging economies: The case of Egypt and Jordan. Energy Policy , 162 , 112775. [CrossRef]

- Belaïd, F. (2022b). Implications of poorly designed climate policy on energy poverty: Global reflections on the current surge in energy prices. Energy Research & Social Science , 92 , 102790. [CrossRef]

- Belaïd, F., & Flambard, V. (2023). Impacts of income poverty and high housing costs on fuel poverty in Egypt: An empirical modeling approach. Energy Policy , 175 , 113450. [CrossRef]

- Boluwaji Elehinafe, F., David Ibukun, F., Ladipo Lasebikan, O., Adisa, H. A., & Elehinafe, F. B. (2023). A review on indoor air pollution from lightning sources in developing countries-The pollutants, the prevention and the latest technologies for control. Applied Chemical Engineering, 6(2). [CrossRef]

- Casati, P., Moner-Girona, M., Khaleel, S. I., Szabo, S., & Nhamo, G. (2023). Clean energy access as an enabler for social development: A multidimensional analysis for Sub-Saharan Africa. Energy for Sustainable Development, 72, 114–126. [CrossRef]

- Deka, A., & Dube, S. (2021). Analyzing the causal relationship between exchange rate, renewable energy and inflation of Mexico (1990–2019) with ARDL bounds test approach. Renewable Energy Focus , 37 , 78-83. [CrossRef]

- Deka, A., Ozdeser, H., & Seraj, M. (2023). The impact of primary energy supply, effective capital and renewable energy on economic growth in the EU-27 countries. A dynamic panel GMM analysis. Renewable Energy , 219 , 119450. [CrossRef]

- Deka, A. (2024). The role of natural resources rent, trade openness and technological innovations on environmental sustainability–Evidence from resource-rich african nations. Resources Policy , 98 , 105364. [CrossRef]

- Deka, A., Abshir, H. M., & Ozdeser, H. (2024). The influence of effective capital, technological innovation and energy efficiency on environmental sustainability on the European region. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology , 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Deka, A., & Efe-Onakpojeruo, C. C. (2024). The role of green finance and natural resources rent in eradicating energy poverty–the case of the Sub-Saharan African countries. Development and Sustainability in Economics and Finance , 100032. [CrossRef]

- Dimnwobi, S. K., Kingsley, ·, Okere, I., Favour, ·, Onuoha, C., Benedict, ·, Uzoechina, I., Ekesiobi, C., Ebele, ·, & Nwokoye, S. (2023a). Energizing environmental sustainability in Sub-Saharan Africa: the role of governance quality in mitigating the environmental impact of energy poverty. 30, 101761–101781. [CrossRef]

- Dimnwobi, S. K., Kingsley, ·, Okere, I., Favour, ·, Onuoha, C., Benedict, ·, Uzoechina, I., Ekesiobi, C., Ebele, ·, & Nwokoye, S. (2023b). Energizing environmental sustainability in Sub-Saharan Africa: the role of governance quality in mitigating the environmental impact of energy poverty. 30, 101761–101781. [CrossRef]

- Dong, K., Wei, S., Liu, Y., & Zhao, J. (2023). How does energy poverty eradication promote common prosperity in China? The role of labor productivity. Energy policy , 181 , 113698. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., Hu, J., Afshan, S., Irfan, M., Hu, M., & Abbas, S. (2023). Bridging resource disparities for sustainable development: A comparative analysis of resource-rich and resource-scarce countries. Resources Policy, 85, 103981. [CrossRef]

- Frees, E. W. (1995). Assessing cross-sectional correlation in panel data. Journal of econometrics, 69(2), 393-414. [CrossRef]

- Frees, E.W., (2004). Longitudinal and Panel Data: Analysis and Applications in the Social Sciences. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Friedman, M. (1937). The use of ranks to avoid the assumption of normality implicit in the analysis of variance. Journal of the american statistical association, 32(200), 675-701.

- Gonzalez, C. G. (2023). Climate Change, Race, and Migration. Journal of Law and Political Economy, 1(1). [CrossRef]

- Hussen, A. M., (2000). Principles of Environmental Economics. Routledge: Taylor & Francis, London & NewYork.

- Im, K. S., Pesaran, M. H., & Shin, Y. (2003). Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. Journal of econometrics, 115(1), 53-74. [CrossRef]

- Kadir, MO, Deka, A., Ozdeser, H., Seraj, M., & Turuc, F. (2023). The impact of energy efficiency and renewable energy on GDP growth: new evidence from RALS-EG cointegration test and QARDL technique. Energy Efficiency , 16 (5), 46. [CrossRef]

- Katoch, O. R., Sharma, R., Parihar, S., & Nawaz, A. (2023). Energy poverty and its impacts on health and education: a systematic review. International Journal of Energy Sector Management. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z., Hossain, M. R., Badeeb, R. A., & Zhang, C. (2023). Aggregate and disaggregate impact of natural resources on economic performance: role of green growth and human capital. Resources Policy, 80, 103103. [CrossRef]

- Khavari, B., Ramirez, C., Jeuland, M., & Nerini, F. F. (2023). Nature sustainability A geospatial approach to understanding clean cooking challenges in sub-Saharan Africa. Nature Sustainability |, 6, 447–457. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Li, Y., Zheng, G., & Zhou, Y. (2024). Interaction between household energy consumption and health: A systematic review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews , 189 , 113859. [CrossRef]

- Machado, J. A., & Silva, J. S. (2019). Quantiles via moments. Journal of Econometrics, 213(1), 145-173. [CrossRef]

- Magnani, N., & Vaona, A. (2016). Access to electricity and socio-economic characteristics: Panel data evidence at the country level. Energy, 103, 447-455. [CrossRef]

- Okere, K. I., Dimnwobi, S. K., Ekesiobi, C., & Onuoha, F. C. (2023). Turning the tide on energy poverty in sub-Saharan Africa: Does Public Debt Matter?. Energy, 282, 128365. [CrossRef]

- Our World in Data (2024): International finance received for clean energy, 2021, https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/international-finance-clean-energy.

- Pesaran, M. H. (2004). General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels. Available at SSRN 572504.

- Pesaran, M. H. (2015). Testing weak cross-sectional dependence in large panels. Econometric reviews, 34(6-10), 1089-1117. [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. H., & Yamagata, T. (2008). Testing slope homogeneity in large panels. Journal of econometrics, 142(1), 50-93. [CrossRef]

- Quito B, del Río-Rama M de la C, Álvarez- García J, Bekun FV (2023) Spatiotemporal influencing factors of energy efficiency in 43 european countries: A spatial econometric analysis. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 182:113340. [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S. A., & Adams, S. (2020). Electricity access, human development index, governance and income inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa. Energy Reports, 6, 455-466. [CrossRef]

- Sha, Z. (2023). The effect of globalisation, foreign direct investment, and natural resource rent on economic recovery: Evidence from G7 economies. Resources Policy, 82, 103474. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, P., Halkos, G. E., & Aslanidis, P.-S. C. (2023). Addressing Multidimensional Energy Poverty Implications on Achieving Sustainable Development. Mdpi.Com. [CrossRef]

- Tsai, W.-H., Jones, E. C., & Reyes, A. (2023). Identifying Themes in Energy Poverty Research: Energy Justice Implications for Policy, Programs, and the Clean Energy Transition. Energies 2023, Vol. 16, Page 6698, 16(18), 6698. [CrossRef]

- Van der Ploeg F, Poelhekke S (2009) Volatility and the natural resource curse. Oxf Econ Pap 61:727–760. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Du, Z. (2024). Has energy poverty entangled the households by hindering the filial generation? Energy Policy , 186 , 114018. [CrossRef]

- Zafar MW, Zaidi SAH, Khan NR, et al. (2019). The impact of natural resources, human capital, and foreign direct investment on the ecological footprint: The case of the United States. Resour Policy 63:101428. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).