Submitted:

03 January 2025

Posted:

06 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

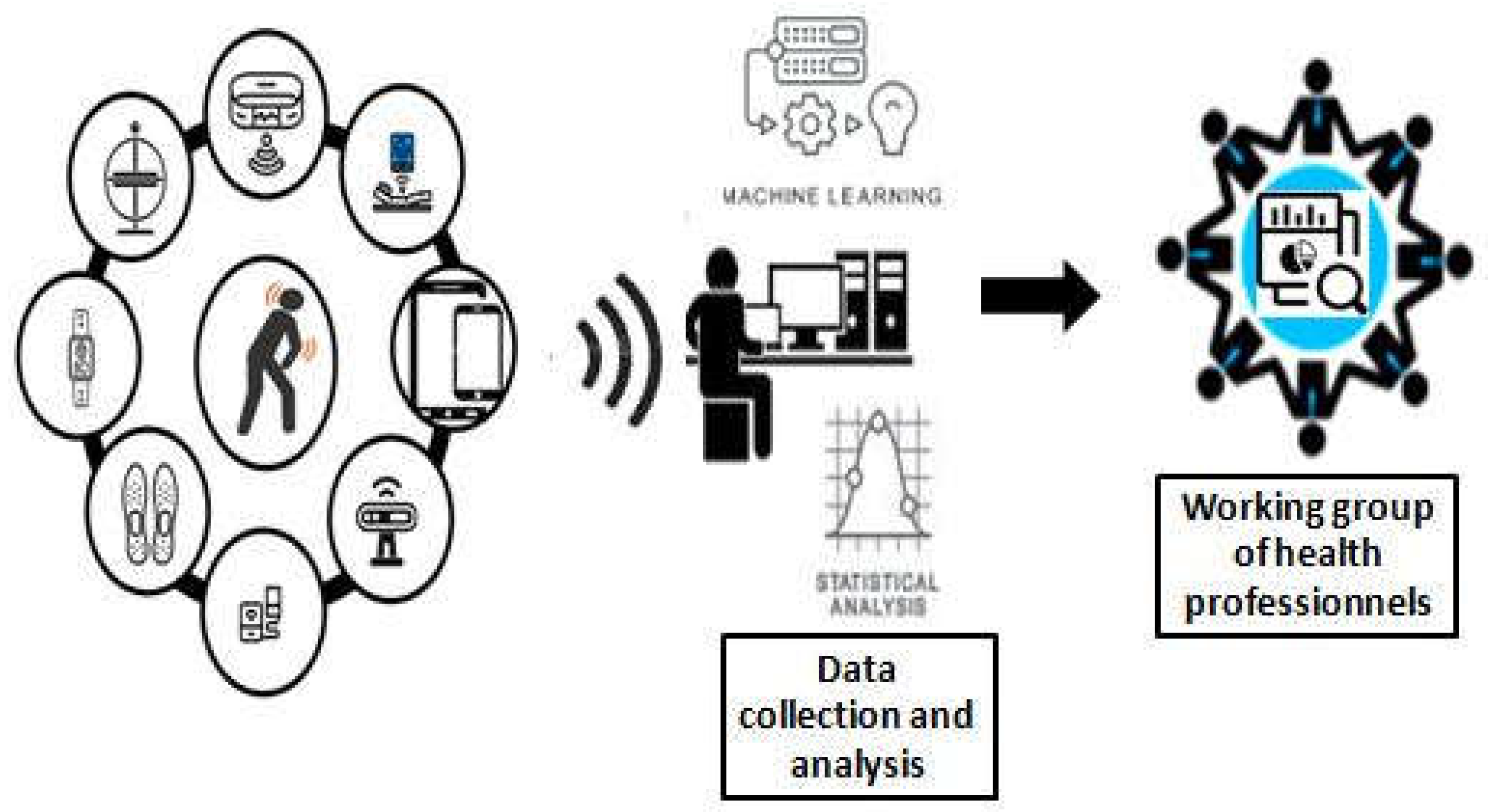

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

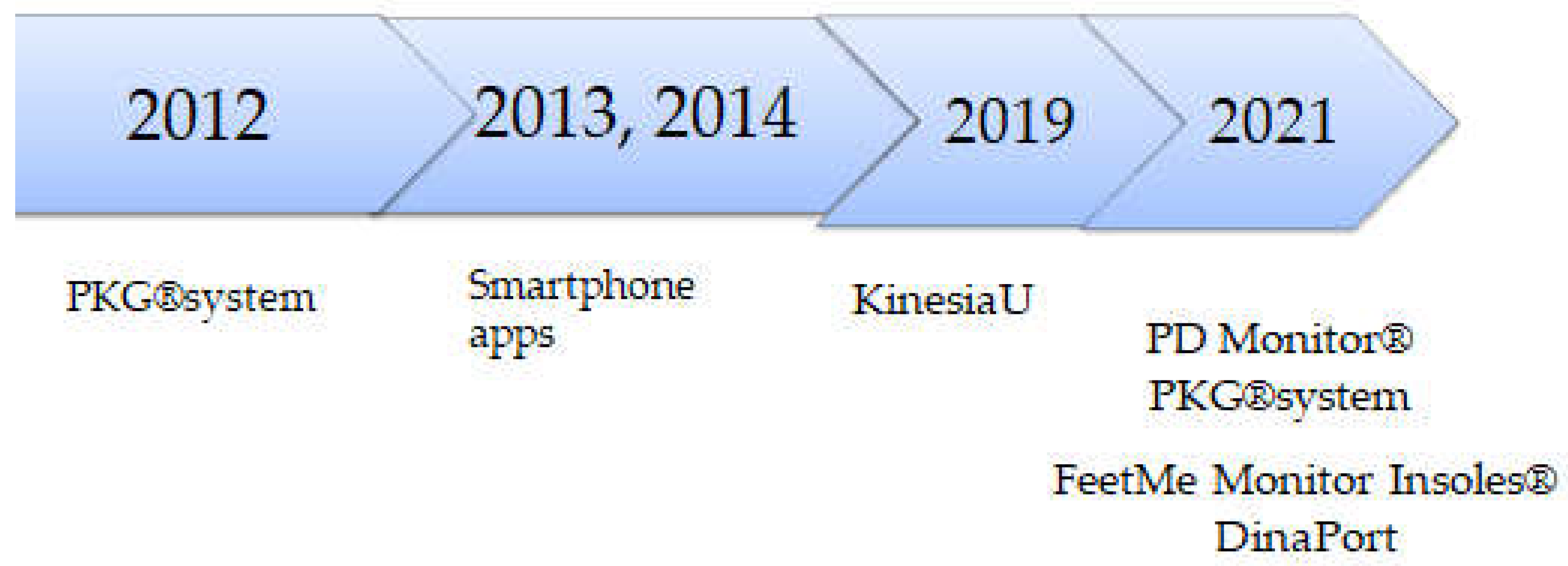

3.1. Wearable, Inertial Sensors and FDA-Approved Devices

3.2. Acoustic, Optical and Electrical and Electrochemical Sensors

3.3. Smartphones

3.4. Smart Domotics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bougea, A.; Angelopoulou, E. Non-Motor Disorders in Parkinson Disease and Other Parkinsonian Syndromes. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024, 11, 60–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, R.A.; McDermott, M.P.; Messing, S. Factors associated with the development of motor fluctuations and dyskinesias in Parkinson disease. Arch. Neurol. 2006, 63, 1756–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonini, A.; Stoessl, A.J.; Kleinman, L.S.; et al. Developing consensus among movement disorder specialists on clinical indicators for identification and management of advanced Parkinson's disease: a multi-country Delphi-panel approach. Curr. Med. Res.Opin. 2018, 34, 2063–2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löhle, M.; Bremer, A.; Gandor, F.; Timpka, J.; Odin, P.; Ebersbach, G.; Storch, A. Validation of the PD home diary for assessment of motor fluctuations in advanced Parkinson's disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2022, 2, 8–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukšys, D.; Jonaitis, G.; Griškevičius, J. Quantitative Analysis of Parkinsonian Tremor in a Clinical Setting Using Inertial Measurement Units. Parkinsons Dis. 2018, 2018, 1683831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, F.; Popa, M.; Solachidis, V.; Hernandez-Penaloza, G.; Belmonte-Hernandez, A.; Asteriadis, S.; Vretos, N.; Quintana, M.; Theodoridis, T.; Dotti, D.; Daras, P. Behavior analysis through multimodal sensing for care of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s patients. IEEE Multimed, 2018, 25, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulou, K.M.; Roussaki, I.; Demestichas, K. Internet of Things Technologies and Machine Learning Methods for Parkinson's Disease Diagnosis, Monitoring and Management: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahoney, D.F.; Purtilo, R.B.; Webbe, F.M.; Alwan, M.; Bharucha, A.J.; Adlam, T.D.; Jimison, H.B.; Turner, B.; Becker, S.A. In-home monitoring of persons with dementia: Ethical guidelines for technology research and development. Alzheimers Dement 2007, 3, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehnemouyi, Y.M.; Coleman, T.P.; Tass, P.A. Emerging wearable technologies for multisystem monitoring and treatment of Parkinson’s disease: a narrative review. Front. Netw. Physiol. 2024, 4, 1354211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichmann, H.; Klingelhoefer, L.; Bendig, J. The use of wearables for the diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2023, 130, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, A.; Russo, M.; Amboni, M.; Ponsiglione, A.M.; Di Filippo, F.; Romano, M.; Amato, F.; Ricciardi, C. The Role of Deep Learning and Gait Analysis in Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review. Sensors (Basel). 2024, 24, 5957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ancillao, A.; Tedesco, S.; Barton, J.; O'Flynn, B. Indirect Measurement of Ground Reaction Forces and Moments by Means of Wearable Inertial Sensors: A Systematic Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzetta, I.; Zampogna, A.; Suppa, A.; Gumiero, A.; Pessione, M.; Irrera, F. Wearable Sensors System for an Improved Analysis of Freezing of Gait in Parkinson's Disease Using Electromyography and Inertial Signals. Sensors 2019, 19, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, V.; Bilal, E.; Ho, B. .; Rice, J.J. Towards motor evaluation of Parkinson's Disease Patients using wearable inertial sensors. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2021, 2020, 203–212. [Google Scholar]

- Klingelhoefer, L.; Rizos, A.; Sauerbier, A.; McGregor, S.; Martinez-Martin, P.; Reichmann, H.; Horne, M.; Chaudhuri, K.R. Night-time sleep in Parkinson’s disease – the potential use of Parkinson’s KinetiGraph: A prospective comparative study. Eur J Neurol 2016, 23, 1275–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, M.J.; Arneson, P.A.; Schenck, C.H. A novel therapy for REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD). J Clin Sleep Med 2011, 7, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggare, S.; Scott, Duncan, T. ; Hvitfeldt, H.; H¨agglund, M. “You have to know why you’re doing this”: A mixed methods study of the benefits and burdens of self-tracking in Parkinson’s disease. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2019, 19, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maetzler, W.; Domingos, J.; Srulijes, K.; Ferreira, J.J.; Bloem, BR. Quantitative wearable sensors for objective assessment of Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2013, 28, 1628–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godinho, C.; Domingos, J.; Cunha, G.; Santos, A.T.; Fernandes, R.M.; Abreu, D.; Gonçalves, N.; Matthew, H.; Isaacs, T.; Duffen, J.; Al-Jawad, A.; Larsen, F.; Serrano, A.; Weber, P.; Thoms, A.; Sollinger, S.; Graessner, H.; Maetzler, W.; Ferreira, J.J. A systematic review of the characteristics and validity of monitoring technologies to assess Parkinson's disease. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2016, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovini, E.; Maremmani, C.; Cavallo, F. Automated Systems Based on Wearable Sensors for the Management of Parkinson's Disease at Home: A Systematic Review. Telemed. J. E Health. 2019, 25, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorp, J.E.; Adamczyk, P.G.; Ploeg, H.L.; Pickett, K.A. Monitoring Motor Symptoms During Activities of Daily Living in Individuals With Parkinson's Disease. Front Neurol. 2018, 9, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Din, S.; Godfrey, A.; Mazzà, C.; Lord, S.; Rochester, L. Free-living monitoring of Parkinson's disease: Lessons from the field. Mov Disord. 2016, 31, 1293–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rovini, E.; Maremmani, C.; Cavallo, F. How Wearable Sensors Can Support Parkinson's Disease Diagnosis and Treatment: A Systematic Review. Front Neurosci. 2017, 11, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, C.; Rolinski, M.; McNaney, R.; Jones, B.; Rochester, L.; Maetzler, W.; Craddock, I.; Whone, A.L. Systematic Review Looking at the Use of Technology to Measure Free-Living Symptom and Activity Outcomes in Parkinson's Disease in the Home or a Home-like Environment. J Parkinsons Dis. 2020, 10, 429–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloem, B.R.; Marks, W.J.; Silva de Lima, A.L.; Kuijf, M.L.; van Laar, T.; Jacobs, B.P.F.; Verbeek, M.M.; Helmich, R.C.; van de Warrenburg, B.P.; Evers, L.J.W.; intHout, J.; van de Zande, T.; Snyder, T.M.; Kapur, R.; Meinders, M.J. The Personalized Parkinson Project: examining disease progression through broad biomarkers in early Parkinson's disease. BMC Neurol. 2019, 19, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturchio, A.; Marsili, L.; Vizcarra, J.A.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Kauffman, M.A.; Duker, A.P.; Lu, P.; Pauciulo, M.W.; Wissel, B.D.; Hill, E.J.; Stecher, B.; Keeling, E.G.; Vagal, A.S.; Wang, L.; Haslam, D.B.; Robson, M.J.; Tanner, C.M.; Hagey, D.W.; El Andaloussi, S.; Ezzat, K.; Fleming, R.M.T.; Lu, L.J.; Little, M.A.; Espay, A.J. Phenotype-Agnostic Molecular Subtyping of Neurodegenerative Disorders: The Cincinnati Cohort Biomarker Program (CCBP). Front Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 553635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.L.; Kangarloo, T.; Tracey, B.; O'Donnell, P.; Volfson, D.; Latzman, R.D.; Zach, N.; Alexander, R.; Bergethon, P.; Cosman, J.; Anderson, D.; Best, A.; Severson, J.; Kostrzebski, M.A.; Auinger, P.; Wilmot, P.; Pohlson, Y.; Waddell, E.; Jensen-Roberts, S.; Gong, Y.; Kilambi, K.P.; Herrero, T.R.; Ray Dorsey, E.; Parkinson Study Group Watch-PD Study Investigators and Collaborators. Using a smartwatch and smartphone to assess early Parkinson's disease in the WATCH-PD study. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2023, 9, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J.L. WATCH-PD: Wearable assessments in the clinic and home in Parkinson’s disease: Study design and update. Mov.Disord. 2020, 35, S1–S702. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton, M.; Baig, F.; Rolinski, M.; Ruffman, C.; Nithi, K.; May, M.T.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Hu, M.T. Parkinson's Disease Subtypes in the Oxford Parkinson Disease Centre (OPDC) Discovery Cohort. J Parkinsons Dis. 2015, 5, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorici, A.; Băjenaru, L.; Mocanu, I.G.; Florea, A.M.; Tsakanikas, P.; Ribigan, A.C.; Pedullà, L.; Bougea, A. Monitoring and Predicting Health Status in Neurological Patients: The ALAMEDA Data Collection Protocol. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. NICE Recommends NHS Collects Real-World Evidence on Devices that Monitor People with Parkinson’s Disease. 2023. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ dg51 (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Antonini, A.; Reichmann, H.; Gentile, G.; Garon, M.; Tedesco, C.; Frank, A.; Falkenburger, B.; Konitsiotis, S.; Tsamis, K.; Rigas,G. ; Kostikis, N.; Ntanis, A.; Pattichis, C. Toward objective monitoring of Parkinson's disease motor symptoms using a wearable device: wearability and performance evaluation of PDMonitor®. Front Neurol. 2023, 14, 1080752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horne, MK.; McGregor, S.; Bergquist, F. An objective fluctuation score for Parkinson's disease. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0124522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pahwa, R.; Isaacson, SH.; Torres-Russotto, D.; Nahab, FB.; Lynch, PM.; Kotschet, KE. Role of the Personal KinetiGraph in the routine clinical assessment of Parkinson's disease: recommendations from an expert panel. Expert Rev Neurother. 2018, 18, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samà, A.; Pérez-López, C.; Rodríguez-Martín, D.; Català, A.; Moreno-Aróstegui, JM.; Cabestany, J.; de Mingo, E.; Rodríguez-Molinero, A. Estimating bradykinesia severity in Parkinson's disease by analysing gait through a waist-worn sensor. Comput Biol Med. 2017, 84, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, JP.; Riley, DE.; Maddux, BN.; Heldman, D.A. Clinically deployable Kinesia technology for automated tremor assessment. Mov Disord. 2009, 24, 723–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mera, T.O.; Heldman, D.A.; Espay, A.J.; Payne, M.; Giuffrida, J.P. Feasibility of home-based automated Parkinson's disease motor assessment. J Neurosci Methods. 2012, 203, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, A.J.; Riley, D.E.; Heldman, D.A. Real-World Evidence for a Smartwatch-Based Parkinson's Motor Assessment App for Patients Undergoing Therapy Changes. Digit Biomark. 2021, 5, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulliam, C.L.; Heldman, D.A.; Brokaw, E.B.; Mera, T.O.; Mari, Z.K.; Burack, M.A. Continuous Assessment of Levodopa Response in Parkinson's Disease Using Wearable Motion Sensors. IEEE Trans Biomed Eng. 2018, 65, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaacson, S.H.; Boroojerdi, B.; Waln, O.; McGraw, M.; Kreitzman, DL.; Klos, K.; Revilla, F.J.; Heldman, D.; Phillips, M.; Terricabras, D.; Markowitz, M.; Woltering, F.; Carson, S.; Truong, D. Effect of using a wearable device on clinical decision-making and motor symptoms in patients with Parkinson's disease starting transdermal rotigotine patch: A pilot study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2019, 64, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, J.D.; McNames, J. Objective measure of upper extremity motor impairment in Parkinson's disease with inertial sensors. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2011, 2011, 4378–4381. [Google Scholar]

- Espay, A.J.; Giuffrida, J.P.; Chen, R.; Payne, M.; Mazzella, F.; Dunn, E.; Vaughan, J.E.; Duker, A.P.; Sahay, A.; Kim, S.J.; Revilla, F.J.; Heldman, D.A. Differential response of speed, amplitude, and rhythm to dopaminergic medications in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2011, 26, 2504–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mera, T.; Vitek, J.L.; Alberts, J.L.; Giuffrida, J.P. Kinematic optimization of deep brain stimulation across multiple motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease. J Neurosci Methods. 2011, 198, 280–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heldman, D.A.; Filipkowski, D.E.; Riley, D.E. , Whitney, C.M.; Walter, B.L.; Gunzler, S.A.; Giuffrida, J.P.; Mera, T.O. Automated motion sensor quantification of gait and lower extremity bradykinesia. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2012, 2012, 1956–1959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mera, T.O.; Filipkowski, D.E.; Riley, D.E.; Whitney, C.M.; Walter, B.L.; Gunzler, S.A.; Giuffrida, J.P. Quantitative analysis of gait and balance response to deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Gait Posture. 2013, 38, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mera, T.O.; Burack, M.A.; Giuffrida, J.P. Objective motion sensor assessment highly correlated with scores of global levodopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2013, 3, 399–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldman, D.A.; Espay, A.J.; LeWitt, P.A.; Giuffrida, J.P. Clinician versus machine: reliability and responsiveness of motor endpoints in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014, 20, 590–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulliam, C.L.; Burack, M.A.; Heldman, D.A.; Giuffrida, J.P.; Mera, T.O. Motion sensor dyskinesia assessment during activities of daily living. J Parkinsons Dis. 2014, 4, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulliam, C.L.; Heldman, D.A.; Orcutt, T.H.; Mera, T.O.; Giuffrida, J.P.; Vitek, J.L. Motion sensor strategies for automated optimization of deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2015, 21, 378–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldman, D.A.; Giuffrida, J.P.; Cubo, E. Wearable Sensors for Advanced Therapy Referral in Parkinson's Disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2016, 6, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldman, D.A.; Urrea-Mendoza, E.; Lovera, L.C.; Schmerler, D.A.; Garcia, X.; Mohammad, M.E.; McFarlane, M.C.U.; Giuffrida, J.P.; Espay, A.J.; Fernandez, H.H. App-Based Bradykinesia Tasks for Clinic and Home Assessment in Parkinson's Disease: Reliability and Responsiveness. J Parkinsons Dis. 2017, 7, 741–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heldman, D.A.; Harris, D.A.; Felong, T.; Andrzejewski, K.L.; Dorsey, E.R.; Giuffrida, J.P.; Goldberg, B.; Burack, M.A. Telehealth Management of Parkinson's Disease Using Wearable Sensors: An Exploratory Study. Digit Biomark. 2017, 1, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sturchio, A.; Dwivedi, A.K.; Marsili, L.; Hadley, A.; Sobrero, G.; Heldman, D.; Maule, S.; Lopiano, L.; Comi, C.; Versino, M.; Espay, A.J.; Merola, A. Kinematic but not clinical measures predict falls in Parkinson-related orthostatic hypotension. J Neurol. 2021, 268, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchman, A.S.; Leurgans, S.E.; Weiss, A.; Vanderhors, V.; Mirelman, A.; Dawe, R.; Barnes, L.L.; Wilson, R.S.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Bennett, D.A. Associations between quantitative mobility measures derived from components of conventional mobility testing and Parkinsonian gait in older adults. PLoS One. 2014, 9, e86262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, E.J.; Mangleburg, C.G.; Alfradique-Dunham, I.; Ripperger, B.; Stillwell, A.; Saade, H.; Rao, S.; Fagbongbe, O.; von Coelln, R.; Tarakad, A.; Hunter, C.; Dawe, R.J.; Jankovic, J.; Shulman, L.M.; Buchman, A.S.; Shulman, J.M. Quantitative mobility measures complement the MDS-UPDRS for characterization of Parkinson's disease heterogeneity. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2021, 84, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, D.; Farid, L.; Ferré, S.; Herraez, K.; Gracies, J.M.; Hutin, E. Evaluation of the Validity and Reliability of Connected Insoles to Measure Gait Parameters in Healthy Adults. Sensors 2021, 21, 6543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardini, F.; Malavolti, M.; Pedrocchi, A.L.G.; Borghese, N.A.; Ferrante, S. A mobile app to transparently distinguish single- from dual-task walking for the ecological monitoring of age-related changes in daily-life gait. Gait Posture. 2021, 86, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farid, L.; Jacobs, D.; Do Santos, J.; Simon, O.; Gracies, J.M.; Hutin, E. FeetMe® Monitor-connected insoles are a valid and reliable alternative for the evaluation of gait speed after stroke. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2021, 28, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granja Domínguez, A.; Romero Sevilla, R.; Alemán, A.; Durán, C.; Hochsprung, A.; Navarro, G.; Páramo, C.; Venegas, A.; Lladonosa, A.; Ayuso, G.I. Study for the validation of the FeetMe® integrated sensor insole system compared to GAITRite® system to assess gait characteristics in patients with multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2023, 18, e0272596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parati, M.; Gallotta, M.; Muletti, M.; Pirola, A.; Bellafà, A.; De Maria, B.; Ferrante, S. Validation of Pressure-Sensing Insoles in Patients with Parkinson's Disease during Overground Walking in Single and Cognitive Dual-Task Conditions. Sensors 2022, 22, 6392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtze, C.; Nutt, J.G.; Carlson-Kuhta, P.; Mancini, M.; Horak, F.B. Levodopa Is a Double-Edged Sword for Balance and Gait in People With Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord. 2015, 30, 1361–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, S.; Liang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Guizani, M. Deep Multi-Layer Perceptron Classifier for Behavior Analysis to Estimate Parkinson’s Disease Severity Using Smartphones. IEEE Access. 2018, 6, 36825–36833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Li, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Albin, R.L.; Guan, Y. Heterogeneous digital biomarker integration out-performs patient self-reports in predicting Parkinson's disease. Comm. Biol. 2022, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.P.; Liang, H.Y.; Chen, Y.S.; Lu, C.H.; Wu, Y.R.; Chang, Y.Y.; Lin, W.C. Objective assessment of impulse control disorder in patients with Parkinson's disease using a low-cost LEGO-like EEG headset: a feasibility study. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2021, 18, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thévenot, D.R.; Toth, K.; Durst, R.A.; Wilson, G.S. Electrochemical biosensors: recommended definitions and classification. Biosens Bioelectron. 2001, 16, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.J.; Lee, C.S.; Kim, T.H. α-Synuclein Oligomer Detection with Aptamer Switch on Reduced Graphene Oxide Electrode. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsmeier, F.; Taylor, K.I.; Kilchenmann, T.; Wolf, D.; Scotland, A.; Schjodt-Eriksen, J.; Cheng, W.Y.; Fernandez-Garcia, I.; Siebourg-Polster, J.; Jin, L.; Soto, J.; Verselis, L.; Boess, F.; Koller, M.; Grundman, M.; Monsch, A.U.; Postuma, R.B.; Ghosh, A.; Kremer, T.; Czech, C.; Gossens, C.; Lindemann, M. Evaluation of smartphone-based testing to generate exploratory outcome measures in a phase 1 Parkinson's disease clinical trial. Mov Disord. 2018, 33, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, R.; Etezadi-Amoli, M.; Arnold, E.M.; Kianian, S.; Mance, I.; Gibiansky, M.; Trietsch, D.; Alvarado, A.S.; Kretlow, J.D.; Herrington, T.M.; Brillman, S.; Huang, N.; Lin, P.T.; Pham, H.A.; Ullal, A.V. Smartwatch inertial sensors continuously monitor real-world motor fluctuations in Parkinson's disease. Sci Transl Med. 2021, 13, eabd7865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iakovakis, D.; Hadjidimitriou, S.; Charisis, V.; Bostantjopoulou, S.; Katsarou, Z.; Klingelhoefer, L.; Reichmann, H.; Dias, S.B.; Diniz, J.A.; Trivedi, D.; Chaudhuri, K.R.; Hadjileontiadis, L.J. Motor Impairment Estimates via Touchscreen Typing Dynamics Toward Parkinson's Disease Detection From Data Harvested In-the-Wild. Front. ICT 2018, 5, 28. [Google Scholar]

- Simonet, C.; Noyce, A.J. Domotics, Smart Homes, and Parkinson's Disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2021, 11, S55–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva de Lima, A.L.; Smits, T.; Darweesh, S.K.L.; Valenti, G.; Milosevic, M.; Pijl, M.; Baldus, H.; de Vries, N.M.; Meinders, M.J.; Bloem, B.R. Home-based monitoring of falls using wearable sensors in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2020, 35, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Biagio, L. , M., Cingolani, D., Buzzatti, L., Capecci, M., Ceravolo, M.G. Virtual reality: A new rehabilitative approach in neurological disorders. In Ambient Assisted Living; Longhi, S., Siciliano, P., Germani, M., Monteriu, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Switzerland, 2014; pp. 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Pfeifer, K.J.; Kromer, J.A.; Cook, A.J.; Hornbeck, T.; Lim, E.A.; Mortimer, B.J.P.; Fogarty, A.S.; Han, S.S.; Dhall, R.; Halpern, C.H.; Tass, P.A. Coordinated Reset Vibrotactile Stimulation Induces Sustained Cumulative Benefits in Parkinson's Disease. Front Physiol. 2021, 12, 624317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melbourne, J.A. , Kehnemouyi, Y.M., O'Day, J.J., Wilkins, K.B., Gala, A.S., Petrucci, M.N., Lambert, E.F.; Dorris, H.J.; Diep, C.; Herron, J.A.; Bronte-Stewart, H.M. Kinematic adaptive deep brain stimulation for gait impairment and freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease. Brain Stimul. 2023, 16, 1099–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davidashvilly, S.; Cardei, M.; Hssayeni, M.; Chi, C.; Ghoraani, B. Deep neural networks for wearable sensor-based activity recognition in Parkinson's disease: investigating generalizability and model complexity. Biomed Eng Online. 2024, 23, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Zhang, D.; Yao, L.; Guo, B.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Y. Deep learning for sensor-based human activity recognition: Overview challenges and opportunities. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagasubramanian, G.; Sankayya, M. ; Multi-variate vocal data analysis for detection of Parkinson disease using deep learning. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 4849–4864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soundararajan, R.; Prabu, A.V.; Routray, S.; Malla, P.P.; RAY, A.K.; Palai, G.; Faragallah, O.S.; BAZ, M.; Abualnaja, M.M.; . Eid, M.M.A.; Rashed, A.N.Z. Deeply Trained Real-Time Body Sensor Networks for Analyzing the Symptoms of Parkinson’s Disease. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 63403–63421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O'Day, J.; Lee, M.; Seagers, K.; Hoffman, S.; Jih-Schiff, A.; Kidziński, Ł.; Delp, S.; Bronte-Stewart, H. Assessing inertial measurement unit locations for freezing of gait detection and patient preference. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2022, 19, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors (publication year ) | DB type | Sample | Assessment tools, ML algorithms/motor parameters | Main results |

| Hoffman et al. (2011) | triaxial gyroscopes and adaptive filters | 11 PD pts | UPDRS/ angular velocity signal | The angular velocity signal was less predictable than those collected from age, weight and height-matched controls |

| Heldman et al. (2012) | heel-worn motion sensor | 22 non-DBS pts with PD20 DBS pts with PD | MDS-UPDRS | kinematic data and clinician scores and produced outputs highly correlated to clinician scores with an average correlation coefficient of 0.86 |

| Mera et al. (2013) | KinetiSense wrist-worn motion sensor | 15 pts with PD | mAIMSPDYS-26 | Prediction of the Levodopa-induced peak-dose dyskinesia severity |

| Weiss et al. (2014) | body-fixed sensor (3D accelerometer) on lower back | 107 PD pts | Walking quantity (e.g., steps per 3-days) and quality (e.g., frequency-derived measures of gait variability) | Successful detection of the transition from non-faller to faller, whereas traditional metrics did not. |

| Ossig et al. (2016) | PKG | 24 PD pts | UPDRSIII motor scorepatient diariesBDI | moderate-to-high concordance of quantitative motor status by PKG and patient diaries |

| Pérez-López et al. (2016) | single belt-worn accelerometer |

1st database:92 PD pts (validation cohort) 2nd database:10 PD pts |

Indoors walking test Outdoors walking test FoG provocation test Dyskinesia test False Positive Test |

95% specificity and 39% sensitivity detecting mild d 95% specificity and 93% sensitivity for severe and mild trunk dyskinesias |

| Samà et al. (2017) | waist-worn triaxial accelerometer | 12 PD pts | UPDRS | >90% accuracy for detection of bradykinesia |

| Bayés et al. (2018) | REMPARK System: sensor +smartphone | 41 pts with moderate to severe idiopathic PD | UPDRSIII motor scorepatient diaries | 97% sensitivity in detecting OFF states and 88% specificity (i.e., accuracy in detecting ON states). |

| Lee et al. (2018) | Shoe-type IMU sensor | 17 PD pts | MDS-UPDRS MMSE/ linear accelerations, cadence, left step length, right step length, left step time, and right step time |

excellent agreement between motor parameters and the shoe-type IMU and motion capture systems |

| Pulliam et al. (2018) | wrist and ankle motion sensors recorded by video | 13 PD prs | UPDRS-III | Algorithm scores for tremor, bradykinesia, and dyskinesia agreed with clinician ratings of video recordings (ROC area > 0.8) |

| Wan et al. (2018) | smartphone accelerometer | 42 pts of early-stage PD | UPDRS ML classification algorithms |

Among all MLs, DMLP captured the best the accelerometer data from the smartphone |

| Buongiorno et al. (2019) | Microsoft Kinect v2 sensor | 16 PD pts |

MDS-UPDRS ANN SVM |

AAN:89.4% accuracy for 9 PD features and 95.0% of accuracy of 6 features in rating PD severity SVM: 87.1% accuracy for 2 PD features |

| Isaacson et al. (2019) | Kinesia 360: wrist and ankle sensors | 39 PD pts | UPDRS Kinesia 360-derived motor scores by time for the EG PDQ-39 PAM-13 |

continuous, objective, motor symptom monitoring as an adjunct to standard care enhances clinical decision-making |

| Mazzetta et al. (2019) | wearable system | Pts with P moderate PD |

real-time FOG detection using gyro and sEMG MDS-UPDRS 7-m TUG test FOG questionnaire |

timely detection of the FOG episode and, for the first time, the automatic distinction of the FOG –fall risk related phenotypes |

| Weiss et al. (2019) | Body fixed sensor | 96 participants with PD • One-off session | MoCA | Timed up-and-go strategies were not related to cognitive function |

| Xiong et al. (2020) | vocal vectors autoencoders | 188 PD pts with and without vocal disorders | 6 Supervised ML algorithms | Efficacy of the Adaptive Grey Wolf Optimization Algorithm in distinguishing the affected and healthy samples of PD |

| Hadley et al. (2021) | smartphone-based KinesiaUTM | 16 PD pts | electronic diary | successfully captured temporal trends in symptom scores following application of new therapy on hourly, daily, and weekly timescales |

| van Kersbergen et al. (2021) | Microsoft Kinect V2 sensor | 19 PD pts |

Camera-derived dataMDS-UPDRS |

significant differences between patients and controls for step length and average walking speed |

| Parati et al. (2022) |

FeetMe® insoles GaitRite®electronic pressure-sensitive walkway |

25 mild-to-moderatePD pts | UPDRS-part III Spatiotemporal gait parameters |

moderate to excellent correlations and good agreement between the two systems |

| Safarpour et al. (2022) | 3 inertial sensors | 31 mild to moderate PD pts |

MDS-UPDRS PIGD |

Prediction of MDS-UPDRS rigidity and PIGD scores by walking bouts, gait speed, and postural sway |

| Adams et al. (2023] | Smartphone smartwatch |

82 pts with early, untreated PD |

MDS-UPDRS Trail Making Test Part A MoCA Symbol Digital Visuospatial Working Memory |

moderate to very strong correlations of gait parameters with sensors measures |

| Antonini et al. (2023) | PDMonitor® | 65 PD pts | UPDRS Part III AIMS |

high accuracy in the detection of motor symptoms and the correlation between their severity |

| Keogh et al. (2023) | McRoberts Dynaport MM + waist worn device | 20 PD pts | Interviews CRS Rabinovich questionnaire |

The device was considered both comfortable and accetable |

| Bailo et al.( 2024) | G-Walk sensor by a semi-elastic belt | 22pts with mild PD | MDS-UPDRS II +III MoCA 6MWT TUG Leg Asymmetry Index Rigidity index Tremor index BMI PIGD |

positive correlations between gait variability and motor parameters |

| Wearable sensors Commercial name |

Study numbers, PD population (size, age, HY, disease duration)*, | Clinical/laboratoryTools assessments | Main outcomes | Medical class/FDA authorization (yes or no) |

| PD Monitor® | Two studies (sample size: 61–65 patients) Age range: NA; | Patients’ diaries AIMS scale UPDRS FoG index postural instability score gait impairment score |

Strong associations with video-recorded UPDRS and AIMS for bradykinesia and dyskinesia, very high for Off-time (accuracy: 99% resting tremor, 96% FoG) | CE mark class IIa /no |

| PKG® | 26 studies, large sample size (max sample size: 3288 patients) Age range: 30–80 yrs; Disease duration range: de novo (2 months) —23 years; HY: 1–4 (but disease data are not reported in all studies) | Patients’ diaries AIMS UPDRS |

Moderate correlation with bradykinesia, high correlation for dyskinesia, and tremor.97.1% sensitivity differentiating fluctuators vs non-fluctuators. | CE mark class Iia /no |

| STAT-ON® | 9 studies (12–75) Age range: 59–83; disease duration: 5–18 yrs; HY: 1–4 | Patients’ diaries UPDRS | 3 studies with good accuracy for On/Off fluctuations detection if compared to patients diaries, 2 studies (12–75 patients) with moderate/high correlation vs. UPDRS-III and gait, respectively; one study with moderate correlation with trunk/leg dyskinesia; one study (39 patients) with fair agreement for dyskinesia and FoG but low agreement for motor fluctuations if compared to UPDRS IV |

CE mark Class Iia /no |

| Kinesia360® | 10 studies (13–60 patients) Age range: 46–85 yrs; disease duration: 2–31 yrs; HY: 1–4 | Patients’ diaries UPDRS TETRAS |

high correlation for resting/postural tremor, dyskinesia and bradykinesia vs. physician-based video recordings | CE mark, Class I/yes |

| DinaPort | 3 studies (40–176 patients) Age range: 41–81; disease duration: 1–14 yrs; HY: 1–4 | MDS-UPDRS | MDS-UPDRS correlates with several gait parameters and misstep with history of falls | CE mark Class II in US and Classv I in EU/ yes |

| FeetMe Monitor Insoles® | one study (25 patients) Age (mean): 69 yrs; disease duration: 4 yrs; HY:2 | GaitRite® gait parameters |

high correlation for gait parameters between pressure-sensing insoles and the electronic walkway | CE-marked class Im /no |

| APDM® | 30 studies (max sample size: 198 PD patients) Age range: 52–78 yrs; disease duration: 1–19 yrs; HY: 1–4 | gold-standard laboratory metrics (GaitRite Mat,Optical MoCap, Force Plate) clinical scales (UPDRS-III, PIGD score) |

Moderate correlation with physicians’- base scales (UPDRS-III, PIGD score) High correlation with FoG episodes longer than 2–5 and >5 s Able to differentiate fallers vs. non fallers | Class II / yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).