1. Introduction

Dimethyl sulfide (DMS), the simplest thioether, is a sulfurous, organic chemical compound with a chemical formula of (CH

3)

2S [

1]. Highly volatile due to its low boiling point (38°C) [

2], it is in gaseous state in brewer’s wort, which is processed in a temperature range from 30-45°C up to 78°C during mashing and up to the boiling point (about 101°C) during hopping [

3]. With odor and flavor concentration threshold in beer in the range 30 to 60 μg/L [

4], DMS is generally detrimental to beer quality, although higher levels are acceptable in lager than ale style [

5].

The chemical pathways leading to the generation of DMS in brewer’s wort have long been known. Since at least 1979, S-methylmethionine (SMM) was identified as the dominant precursor of DMS in malt [

6]. SMM, with a chemical formula of (CH

3)

2S

+CH

2CH

2CH(NH

3+)CO

2−, is a sulfur ylide with three covalent bonds, which are formed by the sulfur atom, and is a typical derivative of the essential amino acid methionine [

7]. A very hydrophilic functional biomolecule and also known as vitamin U, SMM showed efficacy for skin protection and wound healing, hepatoprotection and protection of the digestive tract; its main natural sources are raw cabbage, certain green vegetables, and green malt [

8].

SMM is a heat-labile compound, whose half-life in conventional brewing was established to depend on wort temperature and pH [

9], according to the first-order reaction model represented in Equation (1), which still holds few decades after its discovery:

where

CSMM is time-dependent SMM concentration (μg/L),

t is time (minutes), and

k describes the temperature- and pH-dependent reaction rate (min

-1). Based on Equation (1), SMM half-life can be described by Equation (2):

where

HLSMM is SMM half-life (minutes).

Original experiments aimed at determining

HLSMM [

9], and later experiments focused on the reaction rate

k [

4], showed accurate consistency. In particular, the dependence of the SMM conversion reaction (speed and half-life) on the levels of pH at any given temperature, and on temperature at any given pH, within the respective usual ranges for brewer’s wort processing, were quantitatively established and found to be independent of temperature and pH, respectively.

The conversion reaction of SMM into DMS was described as a nucleophilic substitution reaction by hydroxyl groups ∙OH from water molecules during heat processing [

10], leading to the hydrolysis of the carbon–sulfide bond and the release of protons from the sulfur atom [

7]. Since the content of hydroxyl groups in water increases with pH, also

k increases with pH and consequently

HLSMM decreases.

Free gaseous DMS can be generated from residual SMM also during beer storage due to the exposure to heat and light [

5], thus it is advisable that the total DMS content (sum of SMM and free DMS) at the end of wort cooking and before fermentation is held below approximately 100 μg/L [

4,

11]; however, also based on personal experience, in industrial breweries such threshold is generally fixed around a more conservative level of 60 μg/L. To achieve such target for total DMS content, besides the effective conversion of SMM, free DMS should also be effectively removed from brewer’s wort, which is usually accomplished by vigorous boiling around the temperature of 101°C for a time of 60 to 90 minutes [

12]. Free DMS should be rapidly and effectively removed during wort cooking also to prevent its later reforming from the oxidized form DMSO during fermentation, through metabolic reduction by brewer’s yeast [

11], lead to excessive accumulation of free DMS in the end product. In turn, DMSO is generated from DMS itself during the malt kilning process. This explains the conservative approach by industrial breweries with the threshold of total DMS at the end of wort cooking.

Effective inhibitors of off-flavor compounds in certain heat-treated vegetable beverages were successfully tested, such as phenolic acids, polyphenols, vitamins, and especially the enzyme glucose oxidase, which stabilized SMM by means of the reduction in the content of hydroxyl groups and the protonation of SMM, as well as the oxidation of free DMS by means of hydrogen peroxide produced with gluconic acid [

13]. However, such additives would substantially change pH, glucose content, and sensorial properties, and are not permitted for the use in brewer’s wort.

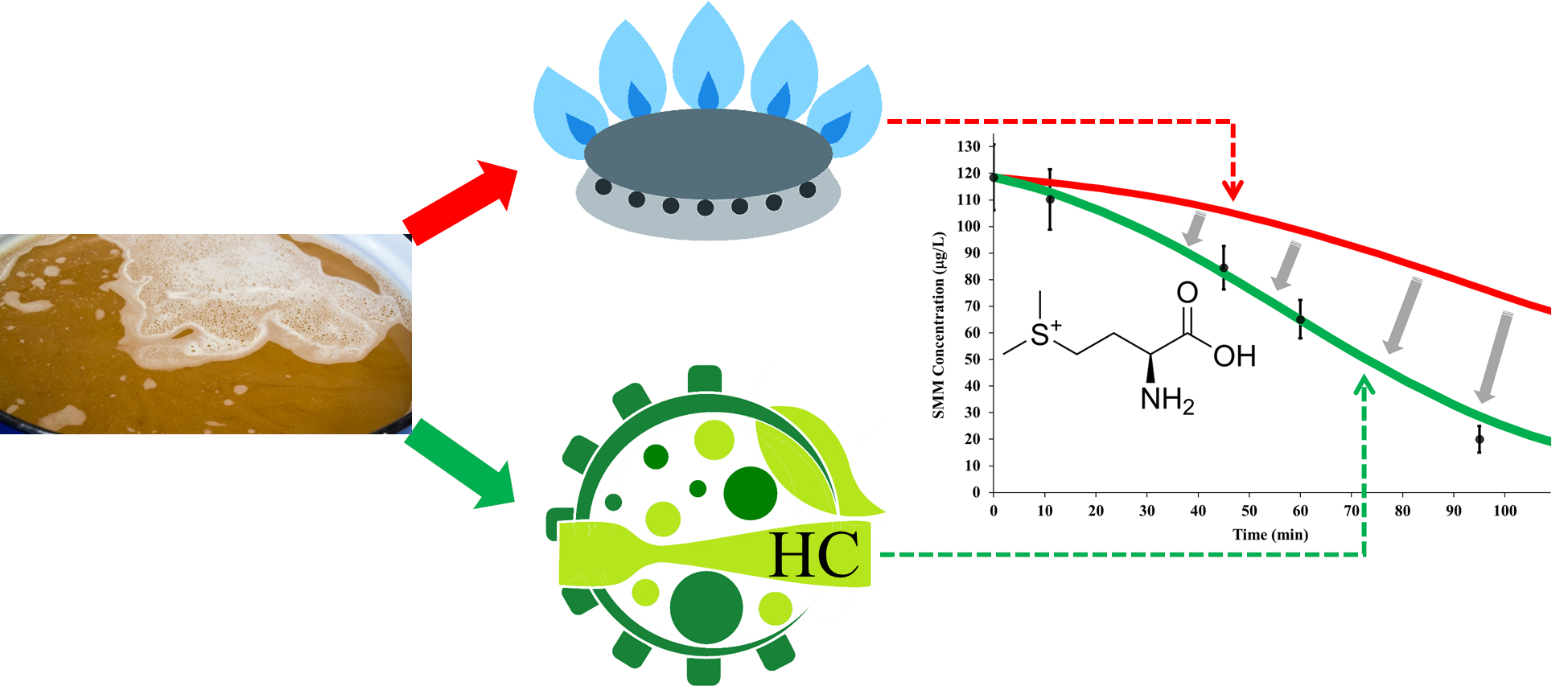

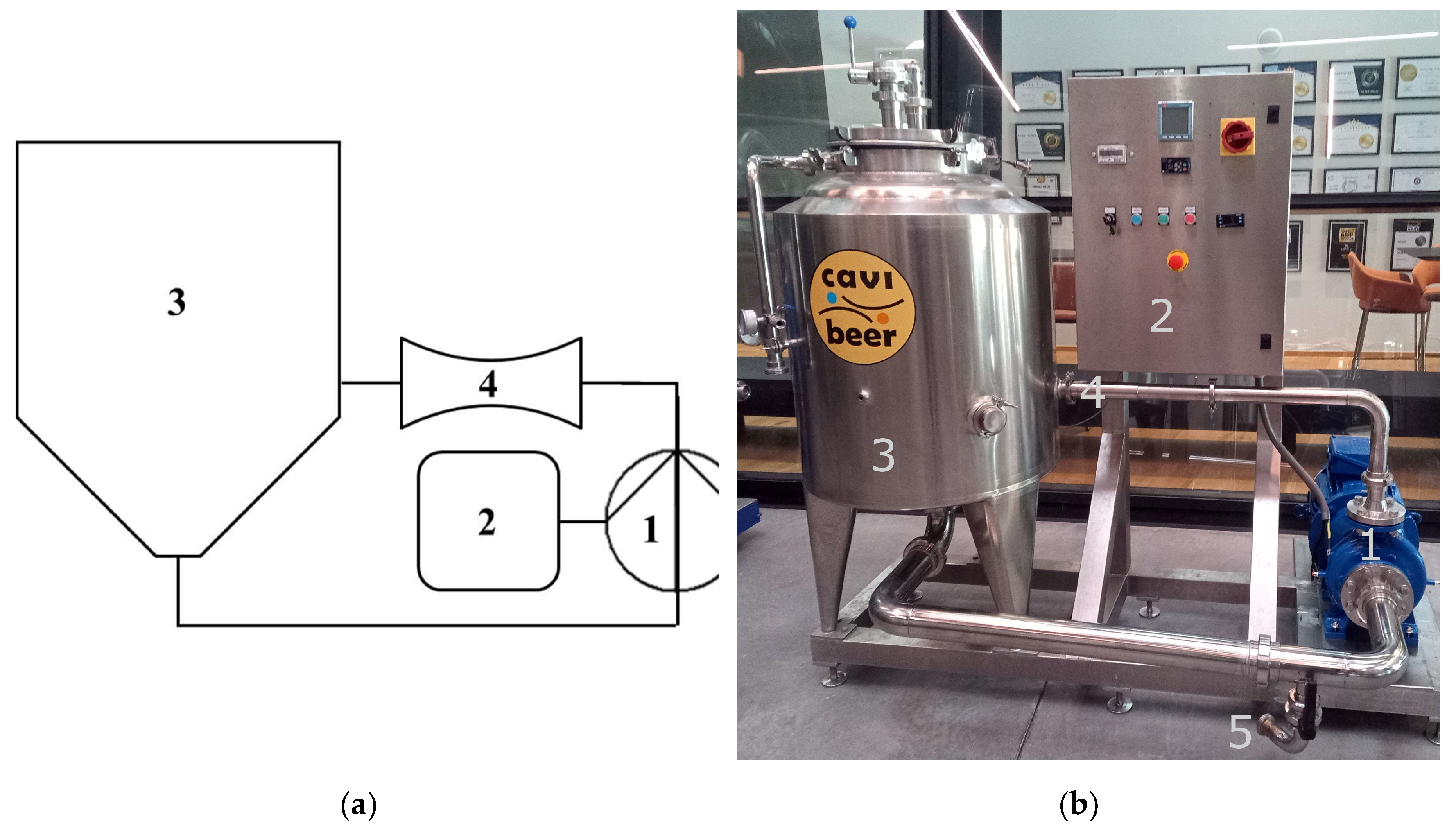

A recent study used hydrodynamic cavitation (HC), a well-known reaction intensification technique whose nature and details are presented in

Section 2, to treat brewer’s wort at the pilot scale according to a structured design of experiments, and found a substantial acceleration of hop alpha-acids isomerization over conventional heat treatment, so much that sufficient isomerization was achieved with HC processing for 90 minutes at the temperature of 90°C [

14]. However, other qualitative parameters of the brewer’s wort, such as total DMS and color, did not comply with standard specifications, requiring further heating to 100°C followed by boiling for 10 minutes at 100°C. Although a lower level of total DMS was achieved in the HC experiment compared to conventional heat treatment (both at the temperature of 90°C for 90 minutes), this topic was overlooked as the study focused on the isomerization of hop alpha-acids.

Past studies showed remarkable advantages of HC-based processing of brewer’s wort both in the mashing and boiling steps, including early saccharification and accelerated isomerization of hop alpha-acids [

3], the extraction of further bioactive compounds from hops [

15], and the possibility to achieve very low gluten content or gluten-free beer from a 100% barley malt recipe [

16].

This study was aimed at retrospectively analyzing and discussing the results of recent experiments performed at the pilot scale, with two primary purposes: further validating the standard model for the SMM conversion reaction and, as the main focus of this study, to investigate, for the first time, the effect of HC processes on the kinetics of the SMM conversion reaction in brewer’s wort compared to the standard model. Secondary objectives were the analysis of the removal rate of free DMS and the pattern of total DMS content, the isomerization rate of hop alpha-acids, and the change of wort color, to assess the compliance of wort properties after HC processes with standard specifications.

2. Hydrodynamic Cavitation

Cavitation in liquid media is a multiphase phenomenon consisting in the generation, growth and quasi-adiabatic collapse of vapor-filled bubbles under an oscillating pressure field, resulting in pressure shockwaves (up to 1000 bar), hydraulic jets, extreme local temperatures (up to thousands of K), and the formation of free radicals, in particular hydroxyl groups [

17,

18].

HC, obtained either by circulating a liquid through static constrictions of various geometries, or by special immersed rotary equipment, is the only fully scalable technological solution, and showed outstanding effectivity and efficiency for food processing, process intensification and extraction of natural products, besides plenty of other applications [

19,

20].

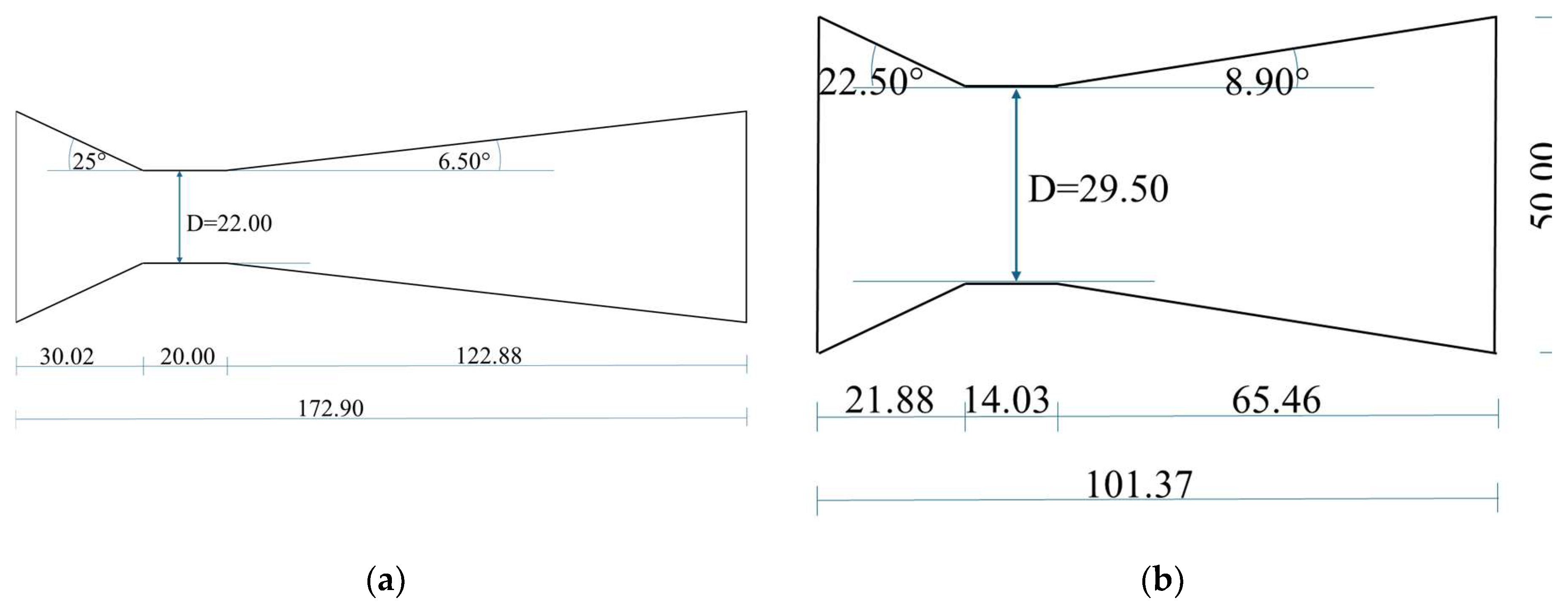

With static HC reactors, the simplest representation of cavitation regimes is given by the cavitation number (σ), derived from Bernoulli’s law and shown in Equation (3):

where

p2 is the recovery pressure downstream the throat (Pa),

psat is the saturation vapor pressure of the liquid (Pa);

ρ is the liquid density (kg⋅m

-3);

u is the flow velocity through the throat (m⋅s

-1) [

21].

Cavitation intensity increases with decreasing cavitation number until the limit of chocked cavitation, with a remarkable increase in the number of cavities that fill the downstream zone of the reactor and reduce the cavitational effects by coalescing and damping the energy released by the neighboring cavity collapse [

22]. In distilled water, the range 0.1<σ<1 corresponds to developed cavitation [

23].

Cavitation can occur also around the impeller of a centrifugal pump, and can be described by the usual cavitation number as in Equation (1) [

24], where the velocity term

u is assumed as the peripheral velocity of the impeller. For most practical applications of HC processes performed under atmospheric pressure, the recovery pressure term

p2 can be assumed equal to the atmospheric pressure (on average, 1 bar at sea level) for both the throat and the pump impeller cavitation zones [

25].

Static HC reactors, such as Venturi or orifice constrictions, were shown to outperform rotation reactors, especially in full-scale applications [

26,

27], with static reactors showing increasing efficiency with size, due to the reduction in pressure and energy requirements to achieve the same flow speed [

28]. With static reactors, σ can easily be controlled through the u quantity, just changing the geometry of the reactor itself, or the frequency of the pump used to circulate the liquid or the mixture, which changes the operating point, thus the head and the discharge, and consequently the flow velocity through the throat. Moreover, all else being equal, σ changes also with the temperature of the circulating medium, due to the temperature dependence of the quantities

psat and

ρ.

HC-based technologies and related methods appear on the verge of widespread industrial uptake, with plenty of opportunities related to the unrivaled intensification of chemical, physico-chemical and biochemical reactions, and residual obstacles due to insufficient technological and process standardization, cultural resistance, and the cost barrier for technological implementation [

29].

4. Results

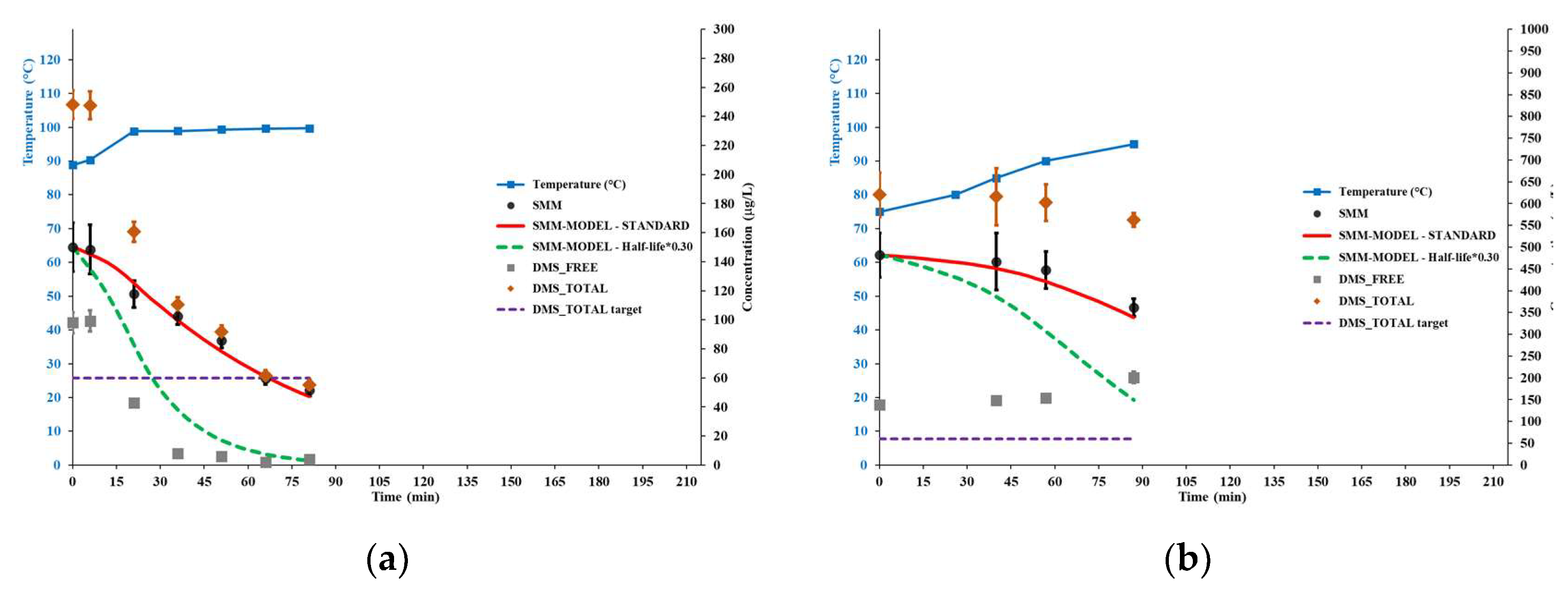

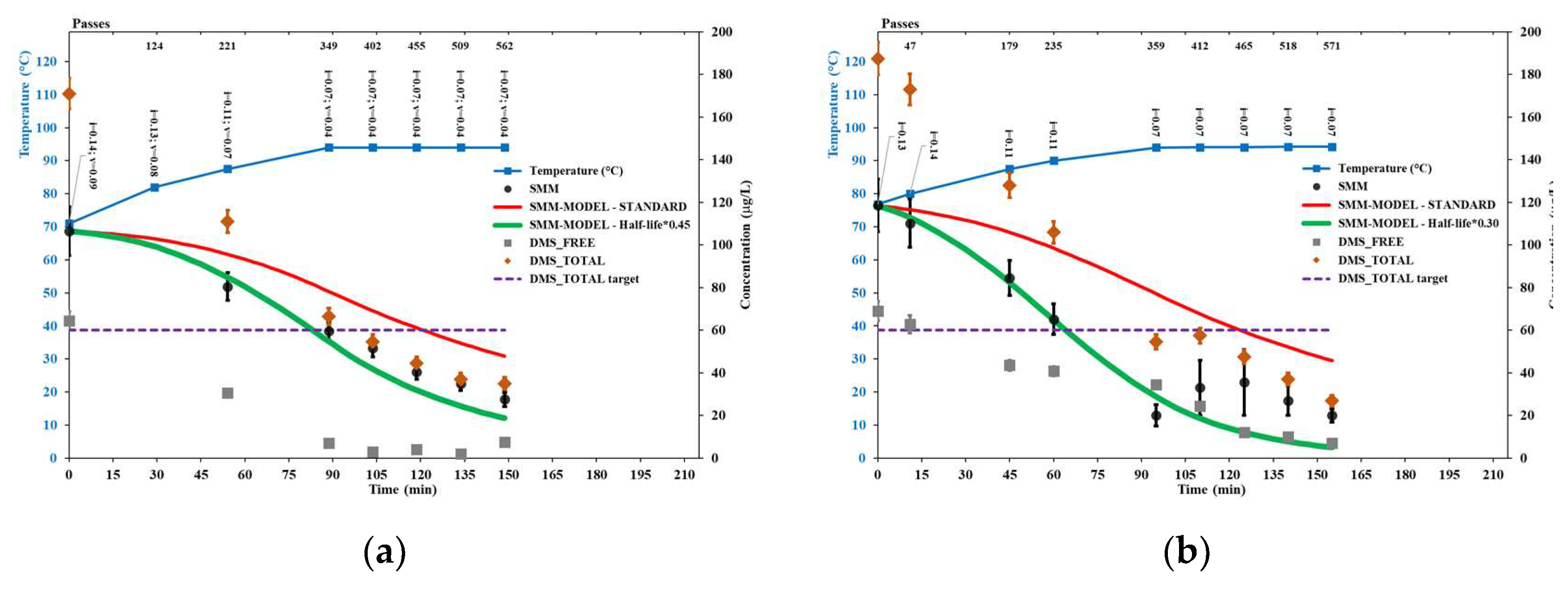

4.1. SMM and DMS in Standard Trials

Figure 3 shows the results of brewer’s wort boiling trials STD1 and STD2, aimed at checking the standard model for the SMM conversion reaction, as represented in Equation (6) and Equation (7). Conservatively, the concentration levels shown for the considered quantities did not take into account the water evaporation occurred during the trials (assessed between 1.5% and 4.5% based on change in Plato degree), i.e., only directly measured data are shown.

The results for trial STD1, performed according to the operational brewery’s boiling practice including strong agitation, show that the evolution of SMM concentration strictly followed the standard model, as well as free DMS was effectively removed from the boiling wort after the boiling temperature of 100°C was achieved.

The results for trial STD2, performed in a separate kettle with little or no stirring, up to the temperature of 95°C, again show that the evolution of SMM concentration strictly followed the standard model. In this case, no effective removal of free DMS from the wort was observed, thus the total DMS content changed very little during the process.

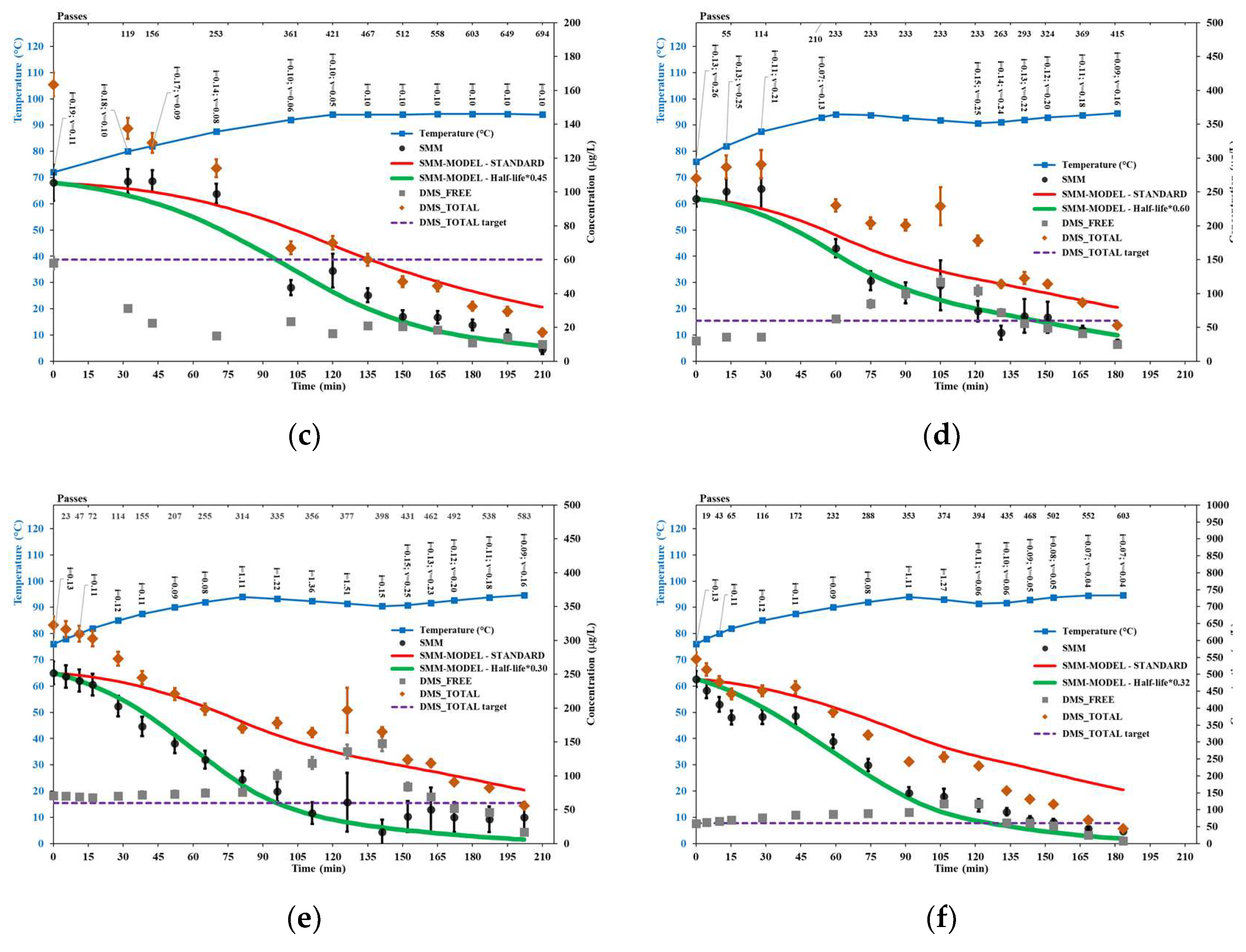

4.2. SMM and DMS in HC Trials

Figure 4 shows the results of brewer’s wort trials performed with the HC device. Conservatively, the concentration levels shown for the considered quantities did not take into account the water evaporation occurred during the trials (assessed between 3% and 10% based on change in Plato degree), i.e., only directly measured data are shown.

The peak temperature in HC trials could not exceed 94.4±0.4°C, likely due to a balance between the power supplied by the pump to the circulating mixture, on the one hand, and the loss of sensible heat and latent heat of evaporation on the other hand. As was stated in

Section 3.1, at temperatures around 94°C, the maximum allowed frequency set through the inverter was in the range 33 to 40 Hz due to excessive foaming, which limited the power supplied by the pump.

While all HC trials showed a remarkable intensification of the SMM conversion reaction, trials with the greatest reduction in SMM half-life (trials HC2, HC5 and HC6) were performed without a Venturi-shaped reactor, i.e., the only cavitation zone occurred in correspondence of the pump impeller, at least until a process temperature of 94°C, with the cavitation number decreasing from approximately 0.13 to 0.06 during wort heating up to the respective peak temperature levels. Notably, the reduction in SMM half-life was practically identical (around 70%, i.e., SMM half-life multiplied by 0.3, or reaction rate increased by about 3.3 times) across the latter trials, despite the wide range of initial contents of SMM and total DMS, corresponding to different levels of the Plato degree, thus of original gravity, and viscosity. These trials were comparable also regarding the passes of the entire volume through the cavitation zone, at least during the first 60 minutes of each process.

Trial HC6 showed a peculiar SMM pattern, with the SMM content initially decreasing very fast, followed by a temporary interruption of the decreasing trend (15 to 43 minutes of process time), and eventually following the modified curve until the onset of the rest phase (90 to 120 minutes of process time), which was introduced in the attempt to reduce the energy consumption. The temporary interruption of the SMM content trend could be attributed to the excessive foaming issue experienced in that phase of the trial H6, likely due to the high original gravity of the wort, which was fixed by inserting a further amount of the anti-foam product.

The effect of cavitation on the SMM conversion rate also arises based on the evident slowdown or discontinuation of the decrease in SMM content after the onset of the rest phases, such as in trials HC4 (from 60 to 120 minutes of process time, no recirculation), HC5 (from 80 to 140 minutes of process time, very slow recirculation), and HC6 (from 90 to 120 minutes of process time, very slow recirculation). Moreover, across the trials performed with a Venturi-shaped reactor, the SMM content initially followed the standard model in trials HC3 and HC4, but not in trial HC1. The most evident differences among such trials were the higher levels of the cavitation number in the impeller zone (HC3) or in the Venturi reactor zone (HC4) compared to HC1.

The removal of free DMS, generated because of SMM decomposition, was very effective at any temperature in trial HC1, which used two cavitation zones, both with low levels of the cavitation number. It was fairly effective at any temperature in trial HC3, which used two cavitation zones with low levels of the cavitation number in the Venturi reactor zone, and in trial HC2, which used only the cavitation zone around the pump impeller. The removal of free DMS was rather ineffective at the lower temperature levels and especially during the rest phases in the other trials, while at the higher temperature levels and with both cavitation zones active, it was fairly effective in trials HC4 and HC5 with relatively high levels of the cavitation number, and very effective in trial HC6 with lower levels of the cavitation number.

4.3. Other Wort Properties in Selected HC Trials

Few other properties of the brewer’s wort were measured for the trials showing the greatest intensification of the SMM conversion reaction (greatest reduction in SMM half-life), i.e., trials HC2, HC5 and HC6.

Table 2 shows the IBU levels, the assessment of hop alpha-acids utilization, and the wort color. Other parameters, such as free amino nitrogen (FAN), total and specific sugars, beta-glucans, and viscosity, were practically unaffected by HC processes.

The initial IBU levels, as high as 7.0±0.1 for trial HC6, were due to residual hop from previous brewing sessions in the brewery’s kettle, which conferred some bitterness to the wort used for the HC experiments. The hop utilization was affected by large uncertainties due to the uncertainty of the alpha-acid content of the used hops (4±1%); however, trial HC2 appeared to have achieved a higher utilization rate, and substantially earlier compared to trials HC5 and HC6.

Wort color significantly increased in all the considered trials, despite relatively large uncertainties. About trial HC2, which showed the lowest increase, it should be noted that the sampling was performed before the onset of boiling at the temperature of 94°C, while sampling for trials HC5 and HC6 was performed near the end of the boiling phase at the temperatures of 94.8°C and 94.5°C, respectively.

5. Discussion

The first important result of this study was the successful validation of the standard model of the SMM conversion reaction [

4,

9], as presented in

Section 4.1, which allowed to confidently assess the effect of the HC processes.

Based on the results presented in

Section 4.2, the SMM conversion reaction was shows to be remarkably intensified by cavitation processes to an extent quite sensitive to HC process parameters, in particular to the cavitation number in the pump impeller or Venturi reactor zones. Cavitation number levels greater than 0.13 in any of those zones appeared to completely suppress the intensification effect, while the presence of two cavitation zones, even with low levels of the cavitation number, damped the intensification effect.

Within the limits of this retrospective study, the optimal setting for the intensification of the SMM conversion reaction, by as much as a factor of 3.3 for the reaction rate k shown in Equation (1), or a reduction by 70% of the SMM half-life shown in Equation (2), was the simple recirculation of the brewer’s wort through the centrifugal pump, provided that the level of the cavitation number in the pump impeller zone was within the range of 0.07 to 0.13, such as in trials HC2, HC5 and HC6.

As anticipated in

Section 1, the conversion reaction of SMM into DMS was described as a nucleophilic substitution reaction by hydroxyl groups from water molecules during heat processing [

10], leading to the hydrolysis of the carbon–sulfide bond and the release of protons from the sulfur atom [

7]. Beyond temperature, the reaction rate is controlled by water pH, as the content of hydroxyl groups in water increases with pH. This framework offers a mechanism to explain the effect of cavitation on the intensification of the SMM conversion reaction, i.e., due to the excess generation of hydroxyl groups. Indeed, as anticipated in

Section 2, the collapse of the cavitation bubbles generates intense hydraulic jets, shockwaves, and highly reactive species, the latter being, in aqueous liquids, ∙OH, H∙, and H

2O

2 [

32].

The HC-based generation of such hydroxyl groups ∙OH could be the main mechanism of intensification of the SMM conversion reaction. On the other hand, due to the very hydrophilic nature of SMM, this molecule could not migrate into the vapor-filled cavitation bubbles, contrary to hydrophobic substances that could undergo pyrolytic disintegration processes. Residing in the bulk aqueous environment, SMM molecules could practically react only with residual ∙OH radicals created by the splitting of water molecules enhanced by cavitation processes, which did not react with other molecules at the gas-liquid interface [

33].

A mathematical model was developed to simulate the global production of hydroxyl radicals in pure water, based on a set of differential equations that account for the hydrodynamics, mass diffusion, heat exchange, and chemical reactions inside the cavitation bubbles generated by HC inside a Venturi-shaped reactor [

22]. The model was successfully validated against the degradation of p-nitrophenol, whose rate is proportional to the content of hydroxyl groups. The model results confirmed and quantified the theoretical prediction that increasing inlet pressure, i.e., increasing flow rate and decreasing cavitation number, leads to premature collapse of the cavitation bubbles, thus less violent collapse events and lower specific generation of ∙OH groups, with relative differences in the specific generation rate levels (number of ∙OH molecules generated per collapsing bubble) spanning up to more than two orders of magnitude (roughly, from 5⋅10

10 to 7⋅10

12 molecules/bubble). However, a lower cavitation number also leads to a higher bubbles generation rate, resulting in a non-monotonic relationship between inlet pressure (cavitation number) and overall generation of ∙OH molecules. Within the limits of cavitation regimes, the range of relative differences in the global production rate of hydroxyl radicals as a function of inlet pressure (or cavitation number) was smaller than the range applicable to the specific production, but still up to one order of magnitude. Thus, it is very likely that, for a given temperature, the content of ∙OH groups in a liquid medium undergoing continuous cavitation increases by substantially more than one order of magnitude compared to heat treatment alone.

A later study further confirmed the sensitivity of the global generation rate of ∙OH radicals in a Venturi-shaped HC reactor on the inlet pressure (cavitation number), even larger than previously predicted (up to roughly three orders of magnitude), as well as further remarkable sensitivity to the geometrical features of the Venturi reactor [

34]. For a simple circular Venturi reactor, with geometrical features quite similar to the ones used in this study, a weak local peak generation rate of ∙OH radicals was found at the inlet pressure of 4 bar, and a substantially higher generation rate at the inlet pressure of 6 bar, further showing the non-monotonicity of the considered dependence.

The above considerations further substantiate the hypothesis that the HC-based increased generation of ∙OH molecules is a major mechanism leading to the intensification of the SMM conversion reaction.

It was shown that, in the case of aqueous mixtures including dissolved solids up to the concentration of 10%, the presence of solid particles generally increases the cavitation efficiency, measured by the vapor content (increase up to about 5%), and in particular the bubbles generation rate [

35]. The main mechanisms were identified in the creation of further cavitation nuclei and in the increase of slip velocity and turbulent kinetic energy, also finding that the range of average diameter of solid particles promoting cavitation decreased with increasing concentration. However, with the increase of the load of soluble extractives with Plato degree (original gravity), viscosity also increased, as shown in

Table 1. Liquid viscosity is an important parameter in the equations of all cavitation models [

36], and a recent study offered a direct observation of pressure shockwaves generated after bubble collapse, as a function of liquid viscosity [

37]. The pressure peak and energy of the primary shockwave decreased very fast with increasing viscosity at a certain distance from the bubble center and attenuated faster with distance, and the shockwave front thickened, thus decreasing the highly relevant pressure gradient. The authors suggested that, with increasing viscosity, most of the energy of the first collapsing bubbles is transferred to the rebound cavitation bubble, thus in high viscosity liquids, more primary bubbles should be generated, producing shorter life and weaker shockwaves, to transfer as much energy as possible to rebound cavitation bubbles and at least partially preserve the cavitation effects.

Based on the above evidence, with increasing Plato degree and viscosity of the brewer’s wort, at any specific level of the cavitation number, the production rate of cavitation bubbles is likely to increase, which could compensate for the decreasing intensity of bubble collapse. Indeed, this seems to be the case, based on the evidence pointed out in

Section 4.2, that the reduction in SMM half-life was practically identical across trials H2, H5 and H6, despite remarkably different viscosity levels. In turn, this would mean that the generation rate of hydroxyl groups did not decrease with increasing gravity or viscosity. The latter considerations further reinforce the hypothesis that the generation of ∙OH molecules is the main mechanism by means of which HC processes intensify the SMM conversion reaction.

The above discussion also allows explaining the remarkable sensitivity of the degree of intensification of the SMM conversion reaction on the level of the cavitation number, which arose especially in trials HC1, HC3 and HC4, based on the different global production of ∙OH radicals. Results achieved in trial HC1, with levels of the cavitation number in the pump impeller zone very similar to trials HC2, HC5 and HC6, could also be explained based on the lower levels of the cavitation number in the Venturi reaction zone (0.09 to 0.04).

A closer look at trial HC1, shown in

Figure 4(a), allows to identify two distinct SMM patterns: a steeper decrease in SMM content up to about 54 minutes of process time, when the cavitation number in the Venturi reactor zone was greater than 0.07, followed by a slower decrease when the cavitation number in the same zone further decreased down to the level of 0.04, which could have even triggered a chocked cavitation regime with effectively inhibition of bubble collapse and generation of ∙OH radicals. This consideration could be relevant for further optimization, as it was shown in

Section 4.2 that the presence of both cavitation zones was favorable for the removal of free DMS, likely due to enhanced turbulence in the circulating wort. Indeed, constraining the levels of the cavitation number in both zones within an optimal range for the intensification of the SMM conversion reaction, such as 0.13 to 0.07, could also be quite effective for the removal of free DMS. This way, and avoiding any apparently useless rest phases, both SMM and free DMS, thus total DMS, could be reduced until achieving compliance with standard specifications faster and with substantially lower energy consumption. This is suggested as a topic of further fundamental and industrial research.

Finally, it can be argued that hydroxyl radicals generated by cavitation events could be effectively scavenged by the reaction with SMM molecules, leaving fewer of them for the oxidation of brewer’s wort. Although this consideration deserves further research for proper confirmation, it would explain why both in the considered experiments and in previous ones, brewer’s wort was never found in an oxidized state.

It is worth noting that the target for total DMS, fixed at the level of 60 μg/L, was achieved in all the considered HC trials, relatively faster (about 90 minutes) in trials whose initial total DMS level was lower, and in particular in HC1, showing intermediate intensification of the SMM conversion reaction and very effective removal of free DMS, and in trial HC2, showing the maximum intensification of the SMM conversion reaction and fairly effective removal of free DMS. Notably, trial HC6, starting with much higher levels of total DMS and SMM, achieved the total DMS target more than 30 minutes earlier than trial HC5 despite practically identical intensification of the SMM conversion reaction, due to the more effective removal of free DMS during the final boiling phase up to about 94°C, and the shorter rest period that limited the accumulation of free DMS.

A relevant question is whether the brewer’s wort, once complying with standard specifications for total DMS, also complies with other quality standards.

Based on data presented in

Section 4.3 and

Table 2 for trails showing the greatest intensification of the SMM conversion reaction, i.e., HC2, HC5 and HC6, the hop utilization rates, as a measure of the effectiveness of the hop alpha-acids isomerization reaction, were affected by large uncertainties due to the original uncertainty on the content of hop alpha-acids, spanning a range from 45±17% to 62±27%. However, hop utilization rates could have been even higher than in previous experiments using HC processes [

3], where they did not exceed 35%. Such a difference could be preliminarily attributed to the higher levels of the cavitation number used in previous experiments. Overall, the achieved results on hop utilization rate complied with brewery’s standard specifications, and confirmed recent results about the HC effect on the acceleration and intensification of the isomerization of hop alpha-acids at substantially sub-boiling temperatures [

14].

While process temperatures were practically identical across the considered trials, the main process differences that could explain the higher hop utilization in trial HC2 were the following:

Based on data presented in

Section 4.3 and

Table 2, the change of wort color index during HC trials HC2, HC5 and HC6, complied with the figures recently shown by Štěrba et al. for other wort boiling experiments involving HC processes and deemed in compliance with standard specifications [

14], with particular regard to the overall increase by about 5 EBC points in trials HC5 and HC6. Notably, such increases occurred between the starting point and the end (HC5) or near the end (HC6) of the trials, and in trial HC5 most of the increase in color index occurred after the end of the rest phase. Due to the practical uselessness of the rest phase, this result could have been safely achieved substantially earlier, such as after 140 min of process time. A similar consideration holds for trial HC6, which underwent a shorter rest phase of 30 minutes. The result shown for trial HC2, i.e., a color index increase by about 2 EBC points, complies with the intermediate result achieved for trial HC5, as the sampling during the trail HC2 was performed at the end of the heating phase and before the onset of boiling around the temperature of 94°C.

As already stated in

Section 4.3, other wort parameters, such as FAN, total and specific sugars, beta-glucans, and viscosity, were practically unaffected by HC processes.

Scaling up the HC device to a full industrial production capacity equipment would be straightforward, as also recently shown for a similar technological setup aimed at processing forestry by-products [

39], and could bring with it distinct advantages:

The sensible heat loss in a full scale HC equipment would be comparatively much lower compared to the pilot scale device used in the considered trials, which will help saving additional energy and process time. Indeed, the balance discussed in

Section 4.2 between the power supplied by the pump, on the one hand, and the loss of sensible heat and latent heat of evaporation on the other hand, would shift to higher temperatures than 94.4±0.4°C, in turn corresponding to higher SMM conversion rates, while preserving or even decreasing the process time and the energy consumption;

Bigger centrifugal pumps used to drive wort circulation in full-scale HC equipment would be more energy efficient than the pump used in the experimental trials discussed in this study, which would help saving additional energy;

A large amount of latent heat of evaporation is available in full-scale equipment for brewer’s wort boiling. It is an ordinary practice in industrial breweries to use such a waste heat, released during previous boiling sessions, to perform a preliminary wort heating, because all the desired processes in conventional wort boiling practically occur starting from temperatures around 95°C. Applying such a preliminary wort heating before HC processing, for example raising the wort temperature up to 85 or 90°C, could help achieving further and substantial energy savings due to the steep increase of the SMM conversion reaction rate with the temperature.

This study is affected by a few important limitations. First, it was a retrospective analysis of few trials performed in the absence of a proper design of experiments. Among other things, the nature of this study prevented the elaboration of a proper statistical fitting processing of the scaling factors of SMM half-life against the SMM content data. Due to logistic and resource constraints, the authors could not perform other trials meant to optimize and further clarify the results. However, based on the data provided with this study, other scholars could repeat the trials, arrange a structured design of experiments, and delve deeper into the subject. Second, the authors realized the relevance of the cavitation zone at the pump impeller only after the conclusion of the experiments and the gathering of sufficient analytical data, which hampered the performance of further sensitivity tests. Third, the available data concerning other brewer’s wort qualities were limited and could not allow a full representation of the degree of compliance of the wort resulting from the HC processes with the standard specifications.

Notwithstanding the above limitations, for the first time this study highlighted the extraordinary performance of hydrodynamic cavitation for the intensification of the SMM conversion reaction at the pilot scale, along with the effective removal of free gaseous DMS and the achievement of an overall compliance of the wort with standard specifications. These findings could pave the way to a long-awaited solution to an important issue affecting the food industry, potentially contributing to remarkable savings in energy and process time. Finally, a similar approach could be used advantageously for the processing of other food resources, such as certain fruit juices or vegetable beverages, which may be affected by off-flavors caused by DMS.