1. Introduction

It is estimated by the National Brain Tumor Society that more than 688,000 people in the United States are living with a primary brain tumor or central nervous system tumor diagnosis [

1,

2,

3]. Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) is the most common and aggressive form of primary brain tumor and has no cure. It is highly malignant, and treatment is largely palliative. The current standard of care consists of surgical resection, radiation therapy and chemotherapy using Temozolomide, (TMZ) [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Most patients (90%) experience recurrence in situ [

8,

9]. To worsen the situation, there is no standard of care for patients of recurrent GBM [

9,

10]. The prognosis for patients diagnosed with GBM remains very poor with the five-year relative survival rate being only 7.2% and the median survival time being only 8 months, without therapeutic interventions [

1,

2,

11,

12]. With treatment, 12-15 months is the mean survival rate. GBM continues to be a major challenge in the clinic as a result of poor prognosis due to aggressiveness and high radioresistence [

3].

It is not completely understood why GBM is so treatment resistant. Among the putative reasons put forward for GBM’s poor prognosis is that conventional therapies target tumoral cells, but not glioblastoma stem cells (GSCs) [

4,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17]. Tumor heterogeneity is another reason given for the high radioresistance and high chemoresistance. GBM can be very resistant to therapeutic involvements because of the complex nature of the tumor itself [

18]. The tumor is varied in characteristics throughout its make-up, showing regions of necrosis and hemorrhage macroscopically, and genetically shows various deletions and point mutations that activate different molecular pathways [

3,

19,

20]. GBMs are not typically cured by surgery since the tumor tissue is not localized but is actually dispersed over larger areas of the brain, resulting in the inability to completely resect the tumor [

3]. Even with multiple surgeries for tumor regrowth, patients die from the spread of tumor into other vital regions of the brain.

The standard of care for GBM has remained unchanged for decades in the form of surgical resection, if possible, radiation therapy (RT), and adjuvant chemotherapy with Temozolomide (TMZ), following initial surgical resection or biopsy [

3,

21]. After maximum surgical resection of GBM, the incidence of recurrence at the primary tumor site is greater than 80%, and the median patient survival is just 12-18 months [

11,

22,

23,

24].

As a result of poor prognosis and outcomes from standard treatments, several new treatment approaches are being tested at the research level and preclinical level with the aims of killing the tumor cells and reducing recurrence [

3,

25,

26]. These methods include systematic administration of radioprotective drugs, and the use of nanoparticles as radiosensitizers [

11,

22,

24]. Through enhanced permeability and cellular retention, functionalized high Z and high electron density nanoparticles are rapidly taken up into tumor cells and can, though the release of secondary electrons, increase the local dose to the tumor [

24,

27,

28,

29]. The secondary electrons that are produced can only travel very short distances within the tumor volume. This process can enhance the generation of more reactive oxygen species (ROS) within the tumor sub-volumes that may produce single and double-stranded DNA breaks [

24,

29]. This can make DNA repair and replication more difficult and can lead to irreversible cell damage [

26,

29].

Here, we use novel nanoparticles, precisely, graphene quantum dots (GQD), in attempt to enhance the therapeutic effects of TMZ and radiotherapy. We quantify such effects using live cell proliferation/migration measurements and clonogenic assays, with the overall goal of finding better treatment outcomes against GBM. Our main hypothesis is that nanoparticles such as GQD can enhance the tumoricidal effects of concurrent TMZ and RT against GBM, to improve overall therapeutic outcome. This main hypothesis falls within an emerging form of combination therapy called nanoparticle mediated chemo-radiotherapy. To account for the inter-patient and intra-tumoral heterogeneity of GBM, we tested our hypothesis on two different GBM cell lines, T98G and U87. Surprisingly, our cloud-based clonogenic assays showed no significant differences in cell survival between treatment conditions with GQD and/or TMZ, and those without. However, cell proliferation/migration, measured in two different and independent ways, namely, an electric cell substrate impedance sensing device, ECIS, and a cloud-based live cell imaging assay, Omni, reveal very significant reductions (p<0.0001) in migration/proliferation for treatment conditions with GQD and/or TMZ. These reductions suggest reduced potential for local invasion and perhaps reduced potential for recurrence. Our assays set the stage for patient-specific theranostics against GBM and other brain cancers, in view of improved treatment outcomes. These results provide parameters for rapid pre-clinical, peri-clinical, and supplementary evaluation of combination modalities against brain tumors. In fact, our cloud-based in vitro assays can already handle 3D tumor spheroids [

30]. The results presented here provide impetus for cloud-based patient-specific assays (using patient-samples), following surgical resection, to determine the best course of treatment for GBM.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biological Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Human Glioblastoma T98G Cell Line

T98G is a glioblastoma multiforme cell line derived from a 61-year-old Caucasian male from the American Type Culture Collection, ATCC. The cells are classified morphologically as fibroblastic and are adherent cells [

31]. The T98G cells used were purchased from the ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) as T98G [T98-G] (ATCC

® CRL-1690

TM). The cells were cultured based on the ATCC recommended protocols, using EMEM + 10% (v/v) FBS + 1% (v/v) P/S, purchased from the ATCC, as the growth medium as well as DMEM +10% (v/v) FBS + 1% (v/v) P/S, also purchased from ATCC. The cells were cultured in an incubator at 37°C ± 1°C and 5% ± 1% CO

2 in-air atmosphere. The population doubling time is approximately 28 hours. The cells were seeded at 1

10

5 – 2 ×10

5 cells/mL and are cultured when the cells are at 80% or 90% confluency using cell medium, trypsin, and phosphate buffered saline (PBS).

2.1.2. Human Glioblastoma U87 Cell Line

U87 is a primary human glioblastoma cell line commonly used in brain cancer research, just as the T98G cell line. U87 cells are adherent cells with an epithelial morphological characteristic. The cells used were purchased from the ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) as U87 [U87 MG] (ATCC® HTB-14TM). This glioblastoma cell line is derived from a human malignant tumor from a hypodiploid female. The cells were cultured using the ATCC recommended protocols, that is, EMEM + 10% (v/v) FBS + 1% (v/v) P/S, purchased from the ATCC, as the growth medium or DMEM +10% (v/v) FBS + 1% (v/v) P/S, also purchased from ATCC. The cells were cultured in an incubator at 37°C ± 1°C and 5% ± 1% CO2 in-air atmosphere. The population doubling time is approximately 34 hours. Like T98G, U87 cells were cultured when the cells were at 80% or 90% confluency using cell medium, trypsin, and PBS.

2.1.3. Cell Culture Procedure

Cells are seeded in either a T-25 or T-75 flask at a density of 1.0 105 – 2.0 105 cells/mL solution. Cells are maintained in the log phase of growth reaching a density of 6.0 105 – 8.0 105 cells/mL before re-seeding the cells into new flasks at an approximate 1:3 ratio. Experiments are conducted at a cell density of approximately 1.0 106 cells/mL.

Both U87 and T98G cell lines were cultured using Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium (EMEM, ACC 30-2003) or Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Corning 10-013-CMR) culture medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco 10100147) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (P/S, Sigma Aldrich P4333-100ML). To begin culturing, the medium in the flask is discarded and then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco 20012027) to remove any remaining medium in the flask. This solution was then discarded as well. The adherent cells were then lifted from the flask with 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco) and incubated for 10 minutes to ensure all cells were lifted. The flask is then viewed using a microscope to check that cells are no longer adherent to the flask. Once detached, the trypsin is neutralized using culture medium. 90 µL of the solution was removed and placed into a separate tube containing 10 µL trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich) for counting and cell viability by hand on a hemocytometer or Invitrogen Countess II automatic cell counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific AMQAX1000). The solution remaining in the flask is then put into the centrifuge and run at 800 RPM for 5 minutes. After centrifuging, the cells form a pellet at the bottom of the tube which allows for an easy removal of medium. The cells are then resuspended in fresh medium, gently pipetted, and seeded into flasks at the aforementioned density.

2.1.4. Cell Preparation

Cells used in experiment are cultured as outlined above, but with different cell densities based on the experiment to be run. Trypan blue is once again used for cell counting and viability measurement using the automatic cell counter. If the viability is determined to be less than about 92% then the cell culture is not used. Cells that are only treated with radiotherapy do not require incubation after reseeding into the new plate, but cells that required outside treatment such as chemotherapeutic drugs or quantum dots are incubated for at least 30 minutes after exposure to ensure sufficient uptake.

2.2. Chemical Materials and Methods

2.2.1. Temozolomide

Temozolomide (TMZ) (Sigma T2577-25MG) was measured following a guide by Liston and Davis [

32] that lists the in vivo dosage that corresponds to the standard clinical dose used. A standard dose for TMZ is 150 mg/m

2 patient which corresponds to a 7300 ng TMZ/mL solution in vitro [

32]. This guide was followed to ensure maximum accuracy in dosage to avoid overdose issues that can occur with the absence of the blood-brain barrier in vitro. A stock concentration of 0.8

0.42 mg/mL solution was used with a final concentration of 7304

523 ng TMZ/mL for the corresponding clinical dose. Our doses of TMZ were kept within clinical margins when compared to in vivo doses [

32].

2.2.2. Graphene Quantum Dots

Aqua green luminescent Graphene quantum dots (GQD) (900712-50ML) suspended in H

2O at a concentration 1 mg/mL were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA). GQDs have strong fluorescent properties that allow for a controllable excitation wavelength, similar to CQDs. The absorption wavelength is 485 nm, and the emission wavelength is 530 nm. According to Sigma-Aldrich, the quantum yield is

17%.[

33].

2.3. Radiotherapy

In order for the method of irradiation to be reproducible and repeatable, the Faxitron’s CellRad™ X-ray irradiator system was used. Faxitron’s CellRad™ is a compact, x-ray irradiator system with an energy range of 10 kV-130 kV, tube current 0.1 mA-5 mA, and a tube power of 750 W. The dose rate unfiltered can reach up to 70 Gy/min and filtered with 0.5 mm aluminum can reach up to 17 Gy/min. The filtered beam is more penetrating and has a maximum field size of 30 cm. Faxitron’s Cellrad™ is equipped with a specimen turntable that is operated electrically to ensure uniform dosing. The irradiator has a built-in, factory-calibrated integrated dosimeter that has a feature called Automatic Dose Control (ADC) that allows for the setting of an exact dose at the center of the turntable. Another feature of Faxitron’s Cellrad™ includes a built-in touchscreen interface for users to have control over the parameters that are relative to delivered dose (see

Figure S1). These parameters include tube energy, tube current, irradiation time, and absorbed dose.

The CellRad has a required 30-minute warm-up period to ensure the peak performance of the system through the gradual increase of tube energies and currents up to the maximum values. A Dose Quality Assurance (QA) check is performed after the warm-up to ensure the accuracy of the dosimeter to within ±5% of the reference doses. This QA confirms that the x-ray and dosimeter are working within acceptable parameters prior to irradiation.

2.4. Cell Survival Measurements

2.4.1. Clonogenic Assay Setup

Clonogenic assays are the gold standard for studying the effectiveness of radiation therapy as cell death or cell survival curves are produced from counting the formation of cell colonies over a span of 21-25 days [

34]. The clonogenic assay enables an assessment of the difference in the ability of cells to reproduce between the untreated control cells and cells that have undergone various treatments such as different levels of ionizing radiation, chemotherapy, and exposure to radiosensitizers. Following both standard and the manufacturer’s protocols, varied cell density counts were used for each condition to ensure statistically relevant results for different radiation dose levels. A range of 50-5000 cells were seeded into wells of a 24-well plate in a volume of 0.6 mL of solution. Two wells of each condition were plated to gather more accurate data for each trial, and 12 conditions were able to be tested in each trial. To ensure more accurate cell counts, cells were plated in 35 mm diameter plates (Falcon 353001) and were allowed to grow for 2-3 days prior to the start of the experiment. These smaller plates were also used as a vessel for treatment in the Faxitron CellRad so that each condition and set of cells could be treated separately. Once the cells are treated, they are lifted from the plate and reseeded into the 24-well plate at the appropriate density for each condition.

Table S1 shows the target number of cells for each condition plated.

2.4.2. Manual Counting Method

We used two different methods to conduct clonogenic assays, a manual counting method and the cloud-based Omni device. In the first method, the cells are treated and seeded into 6 cm diameter well plates with approximately 1000 cells per well. For each condition, 5 well plates are prepared so that colonies are counted in one well every five days while the other plates continue to incubate. The medium in each well plate is also renewed every five days by removing 75% of the medium in the well and replacing it with the same amount of fresh medium.

At each five-day mark, one well plate for each condition is removed from the incubator in order to count the number of cell colonies. The medium is removed from the well plate, and the well plate is then rinsed twice with PBS. The colonies are then fixed using 1 mL of fix solution from a clonogenic assay kit purchased from BioPioneer (CA-001, San Diego, CA). The well plates with the fix solution are then incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes. After 15 minutes, 1 mL of stain solution (crystal violet in dH2O), also from a clonogenic assay kit purchased from BioPioneer (CA-001, San Diego, CA), is added to the well plate to stain the fixed cells. The well plate is then incubated at room temperature for 45 minutes to allow the colonies to be fully stained. The well plates are then rinsed with PBS 3-4 times to remove the remaining stain and fixing solution. Once stained, the well plates are examined under a microscope to count the number of colonies formed posttreatment. Colonies are considered to be clusters of 50 or more cells.

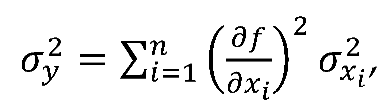

2.4.3. Cloud-Based Omni Method

The second method involves a cloud-based live cell imaging device called the Omni, developed by CytoSMART Technologies (the Netherlands) and recently acquired by Axion Biosystems. The Omni device, shown in

Figure 1, is an automated bright-field microscope that can visualize an entire surface of a cell culture vessel and operate from inside a standard CO

2 incubator. The Omni device is an advanced platform for live-cell analysis that enables continuous imaging of multiple wells from within the incubator. The Omni device is able to capture cellular behavior by creating high-quality time-lapse videos and photos for days or weeks at a time. This machine has an automated setting to scan different size well plates. In this method, we use a 24-well plate and seed a varying number of cells in each well depending on the treatment conditions for said well. For clonogenics, we set the Omni device to capture an image every 24 hours, for 21 days (see

Figure S2 for day 1 and day 21 images). Besides clonogenic analysis, the Omni features five other software/algorithms, namely, Confluency Module which tracks proliferation/migration; Fluorescence Module for fluorescently labelled object detection; iPSC Module for pluripotent stem cells; Organoid Analysis Module and Scratch Assay Module for wound closure investigations. For clonogenics, the Omni counts the number of colonies detected in each image, and the size of colonies that are detected can be adjusted to specific dimensions for greater accuracy.

2.4.4. Clonogenic Assay Analysis

The plating efficiency (PE) is the ratio of number of colonies to the number of cells seeded for the untreated condition,[

35,

36] and is calculated for each trial run to account for any cell death. Equation 1 shows the equation used to calculate plating efficiency.

The number of colonies that form after the treatment of cells, expressed in terms of plating efficiency is called the surviving fraction (SF) [

35,

36]. The surviving fraction is plotted as a function of the dose in order to produce the survival curve. Equation 2 is used to calculate the surviving fraction.

The surviving fraction can be multiplied by 100% in order to find the surviving fraction in terms of percentage. The survival curve is fit to the linear-quadratic model, the most commonly used model for cell survival:

where D is the dose of radiation and

and

are parameters that describe a cell’s sensitivity to radiation-induced cell death as a result of DNA double strand breaks from one ionization event and two ionization events, respectively [

37].

2.5. Cell Proliferation and Migration Measurements

2.5.1. Electric Cell Impedance Sensing (ECIS)

The Electric Cell-substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) method was used to study the impact of quantum dots and chemotherapy drugs on cell proliferation and migration. ECIS is a well-established in vitro impedance measuring system that quantitatively measures cell behavior within adherent cell layers [

38,

39,

40]. The ECIS electronics are contained in two separate units as seen in

Figure S3. The ECIS instrument is capable of measuring the resistance and capacitance of the ECIS electrodes simultaneously over a broad range of AC frequencies. ECIS is used to provide real-time assessment of adherence, migration, and proliferation of cells post-treatment. It provides a noninvasive method of continuous and quantitative monitoring of adherent cells while incubated. We have described the ECIS and our application of it, extensively in our previous works [

41,

42]. Briefly, the ECIS consists of a circuit containing a gold-plated electrode, counter electrode, alternating voltage source, and cell culture substrate. The circuit is completed by the culture medium and adherent cells as they migrate and proliferate across the electrode. The weak alternating (AC) voltage is applied across the circuit in multiple frequencies ranging between 10 Hz and 100 kHz. The impedence (Z) or effective resistance of the circuit is defined by equation where R is the total resistance and X

c is the capacitive reactance of the circuit.

The capacitive reactance is defined as . The capacitive reactance is inversely proportional to both frequency and capacitance so the impedance can be modulated by the frequency of the AC voltage. The current primarily follows ions in the medium that are situation around cells. Low frequencies provide quantitative measurements of the interactions between cells as well as their adherence to the cell substrate. At high frequencies that are generally greater than 40000 Hz, the capacitive reactance is greatly reduced and the impedance is dominated by total resistance, in which the current is directed across the membrane of cells in the substrate. This scenario is best for measurements of cell coverage over the electrode quantifying cell proliferation and migration.

2.5.2. Cloud-Based Omni

The cloud-based Omni device has already been described above. It can be used to quantify other cell behaviors such as proliferation/migration using the confluence module. For cloud-based cell proliferation/migration, cells were seeded at a density of 2 x 10⁵/ml and imaged for about 80 hours. The confluence module of analysis available on the Omni cloud-based software (see

Figures S4 and S5) were used to measure time-dependent cell proliferation/migration over the course of 80 hours.

2.6. Statistical and Computational Methods

2.6.1. Error Analysis

Standard error analysis techniques were performed in order to calculate error and error propagation. Standard error of the mean (SEM) is calculated using the following equation

where

is the standard deviation and N is the sample size, which varied according to experiments. Error propagation was performed using the general propagation formula below

where y depends on a function of variables x

1 to x

n, but propagation is not necessary for values that have their own associated error.

2.6.2. Analysis Using ANOVA

Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) in Origin (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA). ANOVA tests determine if experiment results have significant statistical differences between the means of different data sets [

43]. OriginLab has an ANOVA feature that performs one- and two-way ANOVA tests and gives readouts at different significant levels. Given that many of the experiments performed consisted of multiple conditions, ANOVA was appropriate for means comparison.

3. Results

3.1. Clonogenic Assays Provide Impact of Quantum Dots and TMZ on Cell Survical

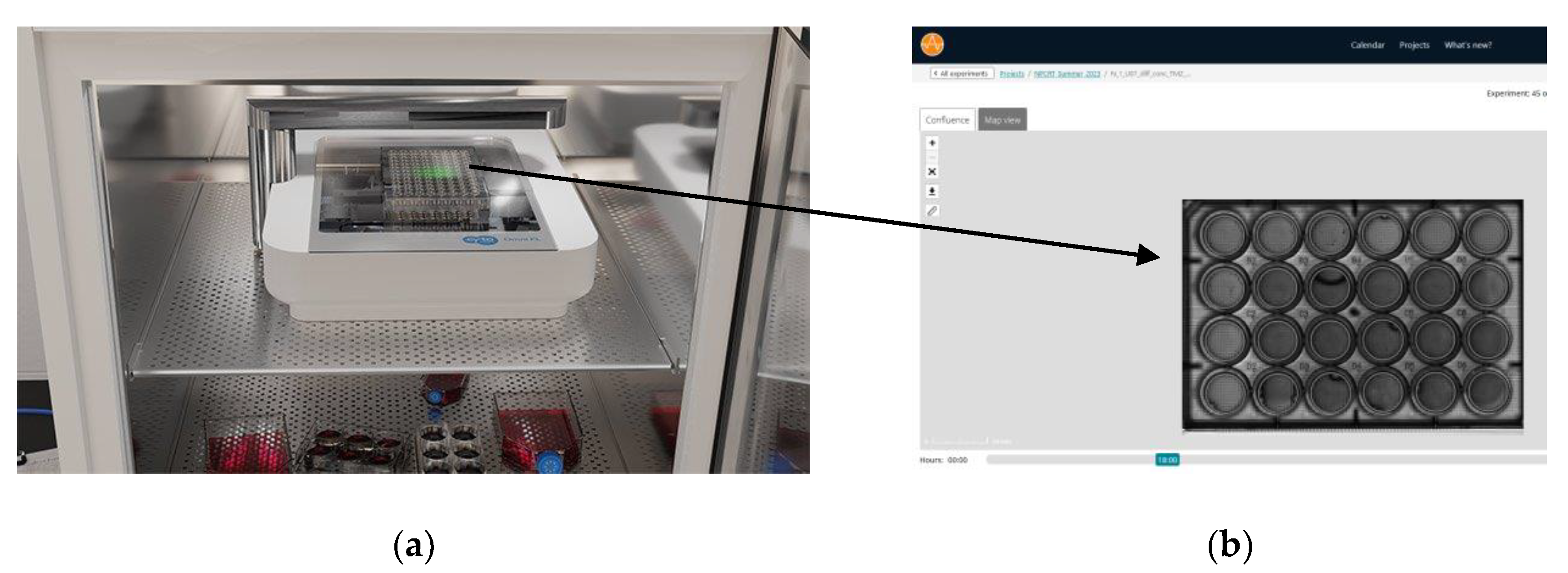

3.1.1. Impact of Graphene Quantum Dots (GQD) Alone with RT on Cell Survival

Clonogenic assays are considered the gold standard in measurement of cell survival following various treatment conditions. The conditions involved U87 cells and T98G cells with different combinations of graphene quantum dots (GQD), radiotherapy, and temozolomide. Cell survival curves were plotted from the survival fraction results and the was α⁄β determined based on fitted linear quadratic model hitherto described (

Section 2.4.4 and Equations 2 and 3). The α⁄β ratio was calculated for each condition tested at 0 Gy, 2 Gy, 5 Gy, 10 Gy, 20 Gy, and 50 Gy. All four treated conditions (T98G only, T98G + GQD, U87 only, U87 + GQD) showed that increased radiation significantly decreased cell survival (p < 0.0001, compared to 0 Gy), as shown in

Figure 2. Surprisingly, there was no statistically significant difference in survival fraction between T98G cells only and T98G cells treated with GQD, at any radiation dosage. There was also no statistically significant difference in survival fraction between U87 cells alone, compared to U87 cells treated with GQD, at any radiation dose. The results shown in

Figure 2, are the averages from three independent N1, N2, and N3 for T98G and U87. The individual trials followed the same trend as their averages. The α/β ratio calculated for each condition can be found in

Table S2. The calculated α/β ratios for T98G were higher than expected, but for U87 the values fell within ranges found in other studies [

44,

45,

46,

47]. These results suggest that those T98G and U87 cells that are subject to radiotherapy-induced cell death remain so, in the presence of GQD. However, it is well known that the GBM stem cell population are the most resistant to treatment [

4,

14,

16]. It might be that GQD does not affect the clonogenicity of the GBM cells including the GSCs among them. But if GQD affects biophysical properties of the GBM cells, such as migration, reducing the spread of GSCs in particular might offer some therapeutic advantage in terms of reducing recurrence.

3.1.2. Impact of Temozolomide (TMZ) and GQD with RT on Cell Survival

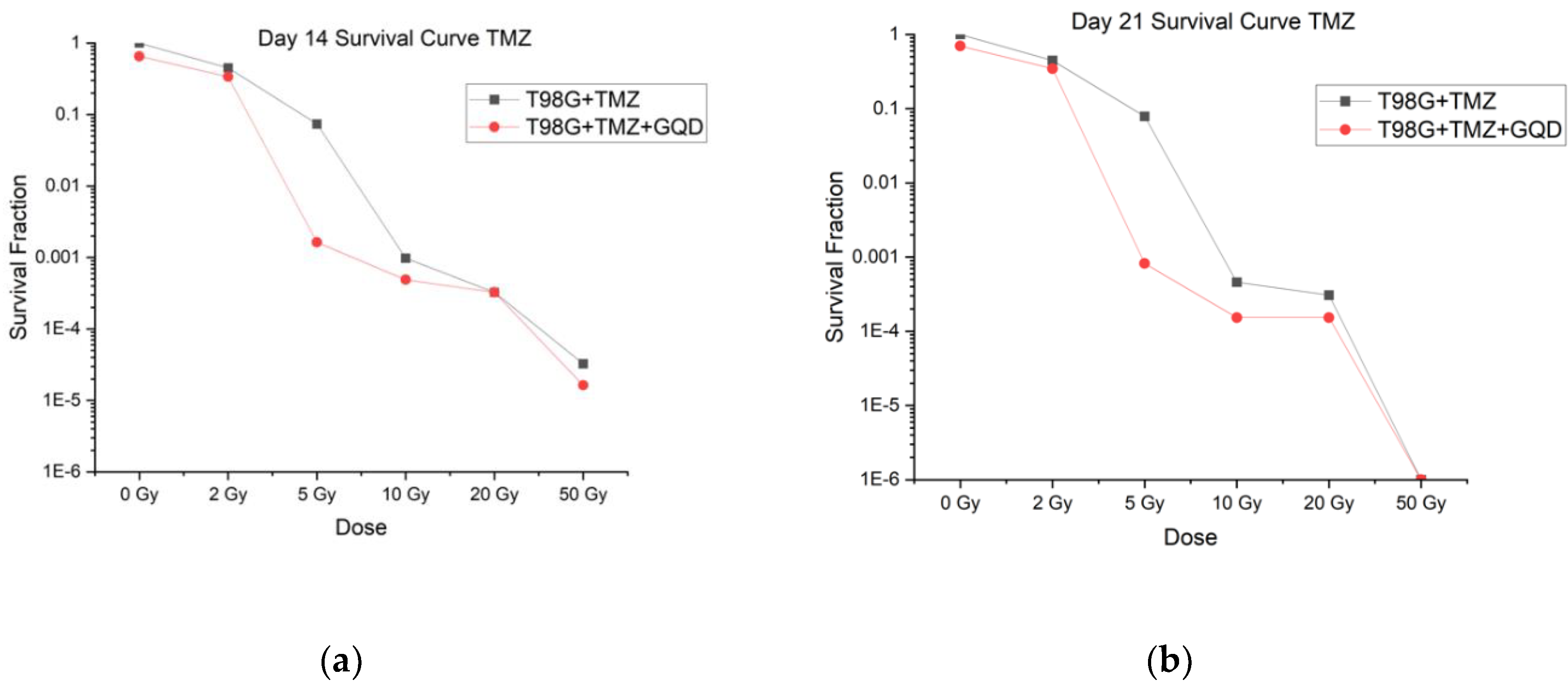

When tested at 0 Gy, 2 Gy, 5 Gy, 10 Gy, 20 Gy, and 50 Gy, all treatment conditions (T98G + TMZ and T98G +TMZ + GQD) showed that increased radiation decreased cell survival (p < 0.0001), as shown in

Figure 3. The figure shows an average of three independent trials, N1, N2, and N3. The α/β ratio was calculated for each condition and can be found in

Table S3. These values followed the same trend as GQD alone where T98G values are higher than expected. Apart from the 5 Gy irradiation, all other radiation doses showe no statistically significant difference in cell survival between T98G + TMZ and T98G +TMZ+GQD. These results suggest that those T98G cells that respond to radiotherapy-induced cell death remain so, in the presence of a combination of GQD and TMZ as well as TMZ alone. Succinclty, 2D clonogenic assays do not show significant advantage of GQD-mediated chemo-and radiotherapy over the standard of care chemo-radiotherapy against GBM, at least, with respect to clonogenicity. These results prompted us to investigate the impact of GQD on chemo-radiotherapy at earlier time points and in terms of parameters important for local invasion, metastasis and recurrence, and not just on direct cell killing.

3.2. Proliferation and Migration Measurements Provide Rational for New Therapeutic Targets

3.2.1. ECIS Migration Results

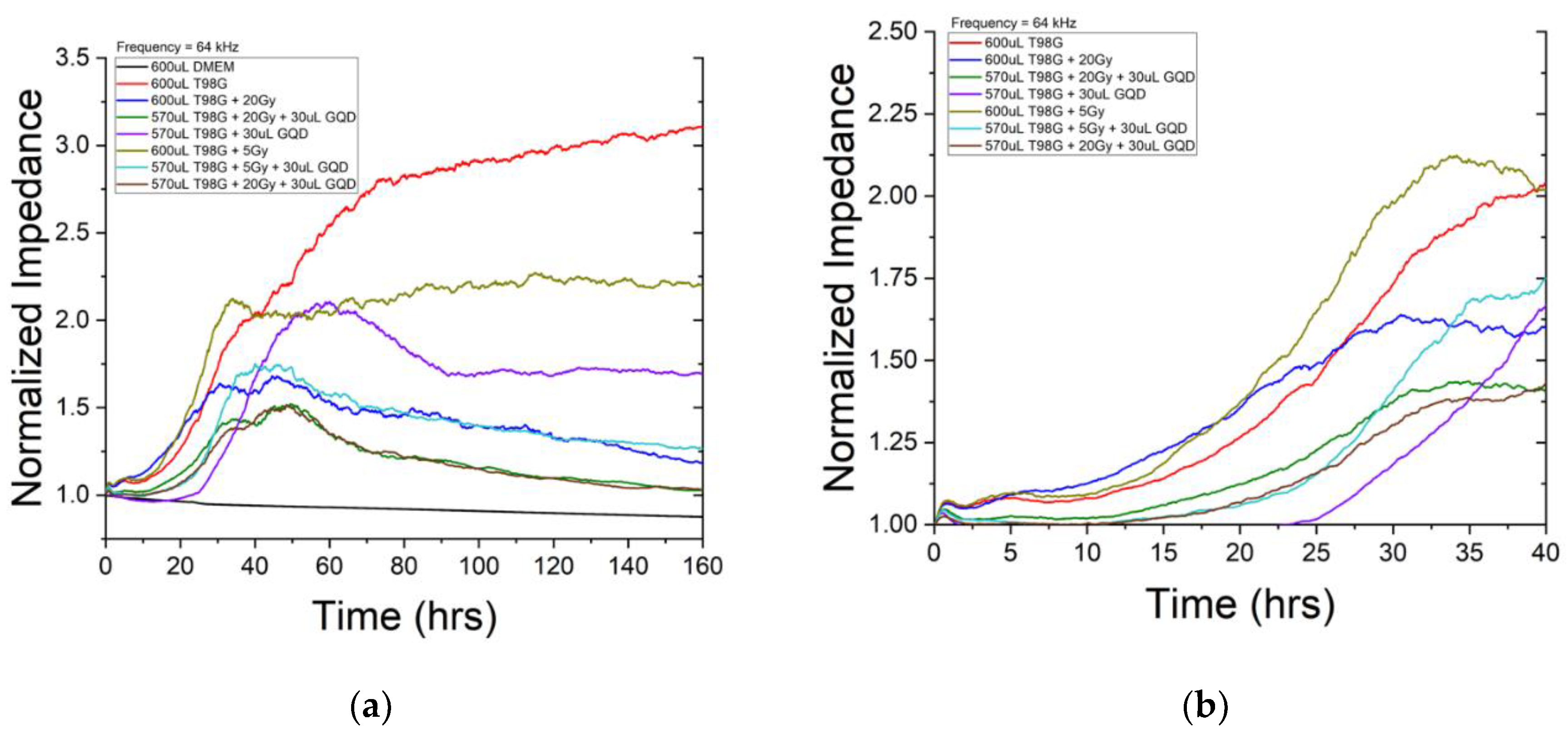

ECIS impedance analysis was employed to monitor cell proliferation and migration within 7 days or 168 hours post-treatment. Though data was taken over several frequences, analysis was performed at 64 kHz where impedance is influenced more by cell-coverage to better characterize migration and proliferation. We see about three regions in the ECIS impedance result (

Figure 4). The first region represents the initial migration and proliferation across electrodes once cells are placed in the incubator. This is characterized by a steady rise impedance where the rate is related to how quickly the cells migrate and proliferate. The second region begins when the migratory and growth patterns of the population of cells is greatly reduced marking a migratory endpoint as impedance plateaus. For a healthy population of cells, this happens when the population completely covers the surface. This is represented by a plateau in the impedance staying relatively constant. The final region occurs after the plateau or end-plateau point. The impedance decreases as cells die and lift from the surface of the electrodes. There are several indications for enhanced radiosensitivity and anti-metastatic effects for irradiated conditions incubated with GQD. First, there is decreased rate of migration and proliferation in the first region represented by a slower increase in impedance measurements. Second, the time it takes for the cell death to begin to occur in the second region once reaching a plateau. This is represented by the duration of the plateau that ends when cells begin to die and lift. The third occurs in the final region describing the rate at which cells die and lift from the surface. Sharper decreases in impedance measurements indicate higher rates of cell death.

Figure 4 shows impedance monitoring of N1 of T98G incubated with GQD. The black curve represents the first control condition containing only DMEM medium. The impedance stays relatively constant throughout the monitoring period confirming that there was no contamination and electronics were performing correctly. The red curve represents our second control and reference conditions containing untreated T98G cells. Compared to untreated T98G cells in the red curve, cells treated with 5 Gy (light brown curve) and cells treated with 20 Gy (blue curve) both expressed enhance migration and proliferation. This is consistent with our previous publication that demonstrated radiation elevates migratory patterns that can result in metastasis [

48].

Indication of GQD enhancement of radiosensitivity can be seen first in

Figure 4, looking at T98G cells incubated with GQD that received 5 Gy (teal curve). T98G cells incubated with GQD and received 5 Gy had a slower rise in impedance in the first region compared to both untreated T98G cells (red curve) and T98G cells that received 5 Gy (light brown curve). This is further depicted in

Figure 4b indicating decreased migration and proliferation. Additionally, T98G cells and the T98G cells that received 5 Gy maintained their plateau region once reaching it. This indicates that the cells reached confluency and maintained a living layer of cells throughout the duration of the study. However, the T98G cells incubated with GQD that received 5 Gy impedance began decreasing shortly after reaching the plateau. This suggests cells began to die and lift around 45 hours into the study much quicker than T98G cells that were not incubated with GQD.

A similar relationship can be seen”In t’e T98G cells incubated with GQD that received 20 Gy dose (green and brown curves). Untreated T98G cells (red curve) and T98G cells that received 20 Gy dose (blue) had a much steeper rise in impedance in the first region of

Figure 4. This suggests that cells incubated with GQD had decreased migration and proliferation comparatively. The trends discussed above repeated in N2 and N3 of the ECIS GQD study (see

Figures S6 and S7). Overall, cell proliferation/migration, measured using ECIS, reveal very significant reductions (p < 0.0001) in migration/proliferation for treatment conditions with GQD and/or TMZ. The ANOVA was carried out on the entire impedance curves shown in

Figure 4a. Clearly, GQD has impact on cell proliferation and cell migration, which is not necessarily reflected in certain measurements of clonogenicity including ours in this manuscript.

3.2.2. Cloud-Based Omni Proliferation and Migration Results

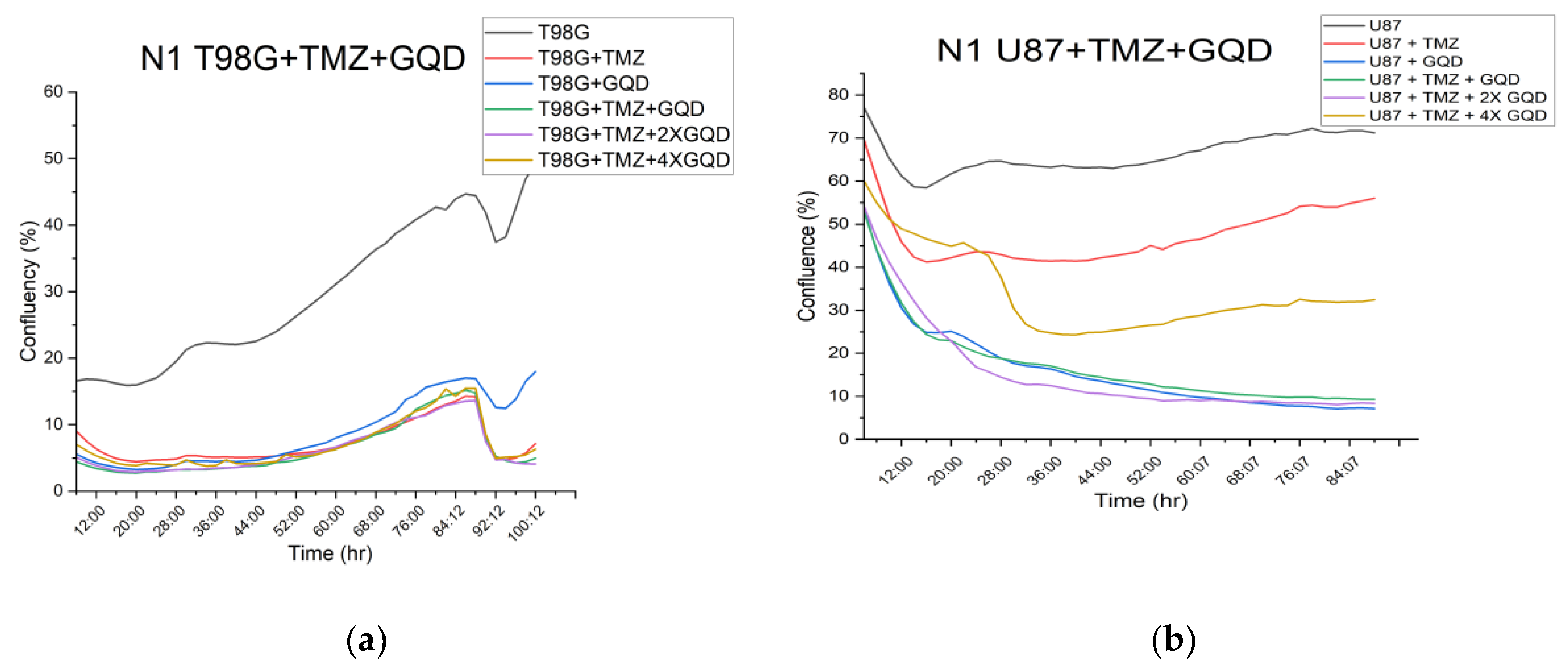

Using the confluence module to analyze proliferation/migration measurements from the cloud-based Omni, our aim was to carry out both independent check on the result from ECIS migration, as well as set the stage for 3D organoid experiments which will further elucidate implications of the migration results on local invasion.

Figure 5 shows the raw confluence results from the Omni device, without normalization.

Figure S4 provides the plots of

Figure 5 along with their standard deviation at every time point.

Figure S5 shows images of the cells at 0, 24 and 72 hours post-treatment. The parametrization of proliferation/migration in the Omni device is image-based or morphometric.

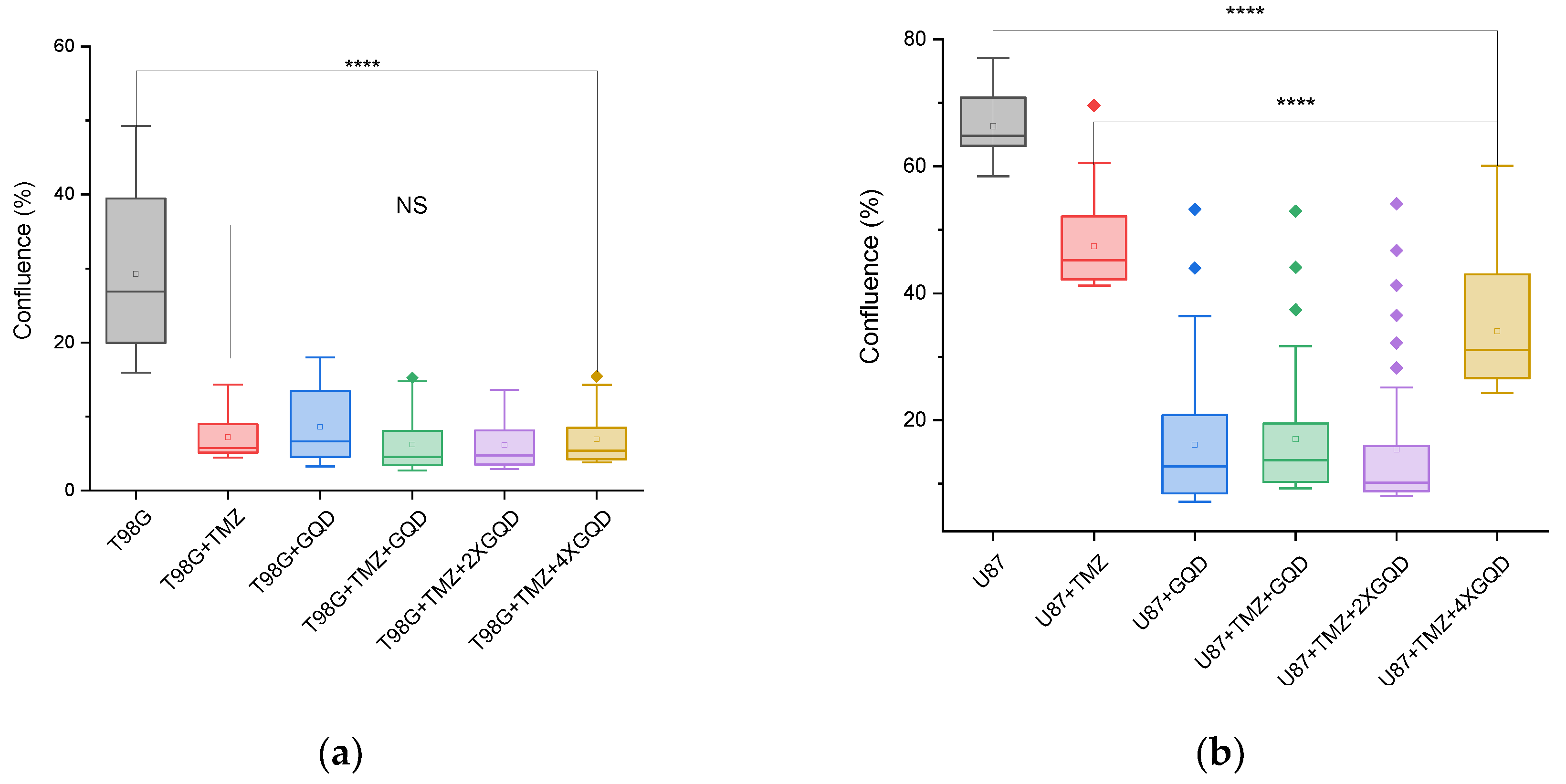

As shown in

Figure 6, the cloud-based Omni assay reveals a statistically significant (p < 0.0001) reduction in morphometric confluency, a readout of cell proliferation/migration, between untreated T98G cells and T98G cells treated with GQD and/or TMZ. The immediate implication of these reductions becomes a new hypothesis and a putative new therapeutic target, namely: can GQD and/or TMZ treatment reduce local invasion of 3D tumors into their surrounding matrix, in vitro or in vivo? This new question, this new possibility or plausible possibility, is a major finding of this work. It gives further scientific rationale for patient-specific theranostics against GBM and other brain cancers, in view of improved treatment outcomes. We now discuss our overall findings within this context of a new therapeutic target for future work.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overall Hypothesis, Current Literature, and Importance of Results

The primary goal of this work was to further develop biocompatible nanoparticles, precisely graphene quantum dot (GQD), as radiosensitizers in combination with chemotherapy drugs, here, temozolomide (TMZ), for nanoparticle-mediated chemo-radiotherapy against glioblastoma (GBM). Two GBM-derived cell lines, T98G and U87, were chosen as they mirror the high radioresistance, high chemoresistance and high heterogeneity of GBM. Previous work had set the scientific basis for our hypothesis by quantifying the changes in ROS production using nanoparticles simultaneously as fluorescent probes via florescence detection techniques and as possible radiosensitizers owing to such ROS production [

49,

50]. Our main working hypothesis that nanoparticles such as GQD can enhance the therapeutic efficacy of concurrent TMZ and RT against GBM, becomes even more plausible, considering several recent reports on mechanisms of action GQD in NPRT against GBM. For instance, functionalized GQD have been shown to modulate malignancy of GBM by downregulating the formation of neurospheres (clusters of GBM cells formed by the presence of a stem cell subpopulation) [

51]. Note that this modulation of malignancy does not show up in terms of changes in clonogenicity. Another mechanistic instance is the finding that GQD enhances the effect of the chemotherapeutic agent doxorubicin on U87 GBM cells by increasing membrane permeability [

52]. Furthermore, by modifying GQDs with appropriate nucleus-targeting ligands, GQD alone has been used as an anticancer therapeutic agent to directly damage the nucleus of cancer cells [

53], without any other chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or other interventions. Thus, while it was disappointing to find that cell survival results from our clonogenic assays 21 days posttreatment did not show significant positive therapeutic contributions from GQD combinations, our migration/proliferation measurements, guided by our cloud-based live cell imaging results, enabled the discovery of possible anti-invasive impact of GQD combinations, which we now recapitulate in the context of existing literature, recent reports from other groups and in view of future work.

4.2. Clonogenic Assay: Impact of GQD on Cell Survival

Both T98G and U87 cell lines had decreasing survival rates with increasing radiation dose when treated at 0 Gy, 2 Gy, 5 Gy, 10 Gy, 20 Gy, and 50 Gy, as expected. There was no significant difference in cell survival between cells treated with radiation only and cells treated with radiation and GQDs for both U87 and T98G cell lines. From these results, it can be concluded that radiation dose does directly affect cell survival, but there is no significant evidence that GQD changes the survival fraction in a positive or negative way. GQDs have demonstrated good biocompatibility and show a high capability of crossing several biological barriers [

54,

55,

56]. Our results support reports of high biocompatibility of GQDs since there was no significant evidence of altered clonogenicity resulting from the addition of GQD. As there is no significant difference in cell survival with the addition of GQD, the positive impact of GQD may be in terms of cell migration associated with local invasiveness and tumor recurrence.

4.3. Clonogenic Assay: Impact of GQD and TMZ on Cell Survival

T98G cells treated with TMZ, GQD, and radiation showed a decreasing cell survival with increasing radiation dose, generally. The conditions treated with GQD had a consistently lower cell survival fraction than the conditions with no GQD at every radiation dose, but the differences were not statistically significant. There was a significant difference (p < 0.0001) in survival fraction between the conditions treated with TMZ only and the conditions treated with TMZ and GQD when both conditions did not receive any radiation, that is, at 0 Gy. From these results, it can be concluded that the addition of GQD with TMZ and radiation does increase cell killing but not in a significant manner. There have been few studies published on the radiosensitizing potential of TMZ for glioblastoma cell lines. In certain cell lines, there has been a demonstrated enhancement of the effects of radiation in certain cell lines, but other cell lines have shown no interaction [

57]. Due to the lack of studies providing evidence of radiosensitization via TMZ, we may presume any radiosensitizing effects result from GQD. A study done by Barazzuol et al. [

58] reports no therapeutic gain from the addition of only TMZ to T98G cells.

4.4. Impedance-Based and Cloud-Based Proliferation/Migration Assay

The primary focus of this research was the combination of TMZ (chemotherapy) and GQDs, with radiation, as nanoparticle mediated chemo- and radiotherapy, against GBM. The significant reductions (p < 0.0001) in cell proliferation/migration parameters from both the impedance-based (ECIS) and cloud-based (Omni) assays, in treatment conditions containing GQD and/or TMZ, are major findings of this work, since they suggest some impact of GQD and TMZ on local invasion and with that, tumor recurrence. When radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant TMZ was established as part of the standard of care against GBM was established [

59], only few mechanisms of action of TMZ were known and GBM stem cells[

13,

15] were not known to be involved. Now that the roles of GBM stem cells are being uncovered, including how GQD even modulates malignancy of GBM by downregulating the action of a stem cell subpopulation [

51], our work gives scientific rationale for investigating the role of GQD on local invasiveness of GBM in 3D tumor microenvironments. We have already successfully generated 3D tissue spheroids [

30] of both GBM cell lines, T98G and U87, in view of testing a new hypothesis, namely, whether 3D cancer spheroids generated via simulated microgravity, can serve as tissue models for nanoparticle mediated radiotherapy (NPRT), chemoradiotherapy and radioimmunotherapy (RIT). Furthermore, the discovery that GQD enhances the effect of other chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin by increasing membrane permeability [

52] and the finding that GQD can act alone as an anticancer agent by directly damaging the nucleus of cancer cells [

53], without any other chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or other interventions, all corroborate our finding regarding the reduction of proliferation/migration in GBM treated with GQD and/or TMZ.

5. Conclusions

In this work, we investigated the effect of concurrent nanoparticle-based radiosensitization and chemoradiotherapy by examining cell survival, cell proliferation, and migration following treatment of two GBM cell lines, T98G and U87. Treatment with increasing radiation dose significantly increased (p < 0.0001) cell death for both T98G and U87 cells treated at 0 Gy, 2 Gy, 5 Gy, 10 Gy, 20 Gy, and 50 Gy. This effect was dominant for all trials regardless of the presence of temozolomide (TMZ), graphene quantum dots (GQD), or a combination of the two. Although clonogenicity based on cell survival curves did not show any significant improvement due to the presence of GQD or TMZ or both, the results from both the impedance-based (ECIS) and cloud-based (Omni) migration/proliferation assays indicate significant decrease (p < 0.0001) in migration due to GQD and TMZ treatments. These reductions in migration in our 2D assays suggest a reduction in local invasiveness in 3D tumor microenvironment. It is local invasiveness that contributes to tumor recurrence which is a main cause of death in patients presenting with GBM. Hence, the results of this research indicate that chemo-radiotherapy using TMZ and augmented with NPs such as GQD provide rationale for 3D migration and cell survival studies, in view of patient specificic prognosis using samples from patients following surgical resection, prior to radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

6. Patents

1. Andrew Ekpenyong, Caleb Thiegs, Anne Hubbard, Yohan Walter, Haris Kramer, Kimal Djam, “Methods for Simultaneous Dose Enhancement and Counter-Metastasis in Cancer Radiation Therapy.” Non-Provisional Patent Application Number. 63270375. (Full patent pending).

nonprovisional patent application, titled: “Cancer Radiation Therapy with Biocompatible Quantum Dots for Simultaneous Dose Enhancement and Counter-Metastasis”, United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) application number 17/970,720, Confirmation# 6513, dated 04/17/2023.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: Faxitron CellRad x-ray irradiator system; Figure S2: Omni images for clonogenics; Figure S3: The electric cell impedance sensing (ECIS) device; Figure S4: Online analysis of Omni experiments; Figure S5: Some proliferation/migration experiment images of cells from the Omni device; Figure S6: ECIS impedance monitoring of various T98G conditions N2; Figure S7: ECIS impedance monitoring of various T98G conditions N3; Table S1: Example conditions for clonogenic assays; Table S2: Average alpha and beta values for each condition +GQD; Table S3: Average alpha and beta values for each condition +GQD+TMZ.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, A.E.; methodology, A.H., J.H., S.S., H.O., N.R., L.B., B.I., K.M., A.K., K.B., I.A., C.T., and A.E.; software, A.H.,B.I.,C.T., and A.E.; validation, A.H., Y.Y. and A.E.; formal analysis, A.H., B.I., C.T., and A.E..; investigation, A.H., J.H., S.S., H.O., N.R., L.B., B.I., K.M., A.K., K.B., I.A., C.T., and A.E; resources, A.H., J.H., S.S., H.O., B.I., C.T., and A.E.; A.H., B.I., I.A., A.E.; writing—original draft preparation, A.H., B.I., C.T., and A.E.; writing— A.H., B.I., C.T., and A.E.; visualization, A.H., B.I., C.T., and A.E; supervision, A.E.; project administration, A.E.; funding acquisition, A.H., B.I., C.T., and A.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by NASA Nebraska Space Grant (Federal Award #80NSSC20M0112) (3D tumor microenvironment) and Nebraska LB696 (Omni Device). Creighton University Internal Grants: CURAS, Haddix, SURF, Clare-Booth, Dr Zepf. This research was funded a Creighton University Startup grant (to AEE) and a CURAS Faculty Research Award, MIRA, to AEE. Nebraska Tobacco Settlement Biomedical Research Development Fund/Creighton University LB692

Institutional Review Board Statement

“Not applicable” since studies did not involve humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

“Not applicable” since studies did not involve humans or animals.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material and indicated as representative data. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author. The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request, directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge technical support from CU IT when equipment used required maintenance/upgrading steps.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NPRT |

Nanoparticle Mediated Radiation Therapy |

| ECIS |

Electric Cell Substrate Impedance Sensing |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| GBM |

Glioblastoma multiforme |

| GQD |

Graphene Quantum Dot |

| ROS |

Reactive Oxygen Species |

| PE |

Plating Efficiency |

| GSC |

Glioblastoma Stem Cells |

| ATCC |

American Type Culture Collection |

| PBS |

Phosphate Buffered Saline |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| EMEM |

Eagle’s Minimum Essential Medium |

| FBS |

Fetal Bovine Serum |

References

- “National Brain Tumor Society,” in The Grants Register 2019, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Y. Wen and S. Kesari, “Malignant Gliomas in Adults,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 359, no. 5, 2008. [CrossRef]

- E. C. Holland, “Glioblastoma multiforme: The terminator,” 2000. [CrossRef]

- J. Hawly, M. G. J. Hawly, M. G. Murcar, A. Schcolnik-Cabrera, · Mark, and E. Issa, “Glioblastoma stem cell metabolism and immunity,” vol. 43, pp. 1015–1035, 2024. [CrossRef]

- R. D. Read, Z. M. R. D. Read, Z. M. Tapp, P. Rajappa, and D. Hambardzumyan, “Glioblastoma microenvironment-from biology to therapy,” 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Lee et al., “nature medicine High-throughput identification of repurposable neuroactive drugs with potent anti-glioblastoma activity,” Nature Medicine |, vol. 30, pp. 3196–3208, 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. S. Dash, Y.-J. B. S. Dash, Y.-J. Lu, and J.-P. Chen, “Enhancing Photothermal/Photodynamic Therapy for Glioblastoma by Tumor Hypoxia Alleviation and Heat Shock Protein Inhibition Using IR820-Conjugated Reduced Graphene Oxide Quantum Dots,” Cite This: ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, vol. 16, pp. 13543–13562, 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Matcovschii, D. V. Matcovschii, D. Lisii, V. Gudumac, and S. Dorosenco, “Selective interstitial doxorubicin for recurrent glioblastoma,” Clin Case Rep, vol. 7, no. 12, pp. 2520–2525, Dec. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Ratliff et al., “Patient-Derived Tumor Organoids for Guidance of Personalized Drug Therapies in Recurrent Glioblastoma,” Int J Mol Sci, vol. 23, no. 12, p. 6572, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Wang et al., “Comparison of tumor immune environment between newly diagnosed and recurrent glioblastoma including matched patients,” J Neurooncol, vol. 159, no. 1, pp. 163–175, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Haj, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Extent of Resection in Newly Diagnosed Glioblastoma: Impact of a Specialized Neuro-Oncology Care Center,” Brain Sci, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 5, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. Quan, H. R. Quan, H. Zhang, Z. Li, and X. Li, “Survival analysis of patients with glioblastoma treated by long-term administration of temozolomide,” Medicine, vol. 99, no. 2, p. e18591, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Mehta, A. M. Mehta, A. Khan, S. Danish, B. G. Haffty, and H. E. Sabaawy, “Radiosensitization of primary human Glioblastoma stem-like cells with low-dose AKT inhibition,” Mol Cancer Ther, vol. 14, no. 5, pp. 1171–1180, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. U. Ahmed, R. S. U. Ahmed, R. Carruthers, L. Gilmour, S. Yildirim, C. Watts, and A. J. Chalmers, “Selective inhibition of parallel DNA damage response pathways optimizes radiosensitization of glioblastoma stem-like cells,” Cancer Res, vol. 75, no. 20, pp. 4416–4428, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- J. D. Lathia, S. C. J. D. Lathia, S. C. Mack, E. E. Mulkearns-Hubert, C. L. L. Valentim, and J. N. Rich, “Cancer stem cells in glioblastoma,” Genes Dev, vol. 29, no. 12, pp. 1203–1217, Jun. 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. D. Robilliard et al., “Can ECIS Biosensor Technology Be Used to Measure the Cellular Responses of Glioblastoma Stem Cells?,” Biosensors (Basel), vol. 11, no. 12, p. 498, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Beier, J. B. D. Beier, J. B. Schulz, and C. P. Beier, “Chemoresistance of glioblastoma cancer stem cells - much more complex than expected,” Mol Cancer, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 128, Oct. 2011. [CrossRef]

- P. Y. Wen and S. Kesari, “Malignant Gliomas in Adults,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 359, no. 5, pp. 492–507, Jul. 2008. [CrossRef]

- T. L. Whiteside, “The tumor microenvironment and its role in promoting tumor growth,” Oncogene, vol. 27, no. 45, pp. 5904–5912, Oct. 2008. [CrossRef]

- H. A. Goubran, R. R. H. A. Goubran, R. R. Kotb, J. Stakiw, M. E. Emara, and T. Burnouf, “Regulation of Tumor Growth and Metastasis: The Role of Tumor Microenvironment,” Cancer Growth Metastasis, vol. 7, 2014. [CrossRef]

- F. Dhermain, “Radiotherapy of high-grade gliomas: Current standards and new concepts, innovations in imaging and radiotherapy, and new therapeutic approaches,” Chin J Cancer, vol. 33, no. 1, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Zehri, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Neurosurgical confocal endomicroscopy: A review of contrast agents, confocal systems, and future imaging modalities,” Surg Neurol Int, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 60, 2014. [CrossRef]

- R. C. Fields et al., “Surgical Resection of the Primary Tumor is Associated with Increased Long-Term Survival in Patients with Stage IV Breast Cancer after Controlling for Site of Metastasis,” Ann Surg Oncol, vol. 14, no. 12, pp. 3345–3351, Nov. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Kimal Honour Djam, “Nanoparticles for Simultaneous Assessment of ROS and Radiosensitization of Brain Cancer Cells for Improved Radiotherapy Outcomes,” Creighton University, Omaha, 2020.

- R. Baskar, K. A. R. Baskar, K. A. Lee, R. Yeo, and K.-W. Yeoh, “Cancer and Radiation Therapy: Current Advances and Future Directions,” Int J Med Sci, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 193–199, 2012. [CrossRef]

- D. Hanahan and R. A. Weinberg, “Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation,” 2011. [CrossRef]

- H. Wang, X. H. Wang, X. Mu, H. He, and X. D. Zhang, “Cancer Radiosensitizers,” 2018. [CrossRef]

- P. Wardman, “Chemical Radiosensitizers for Use in Radiotherapy,” Clin Oncol, vol. 19, no. 6, 2007. [CrossRef]

- E. L. Alpen, Biophysics of Radiation: Radiation Biophysics, 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1990.

- S. McKinley et al., “Simulated Microgravity-Induced Changes to Drug Response in Cancer Cells Quantified Using Fluorescence Morphometry,” Life, vol. 13, no. 8, p. 1683, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. A. P. Franken, H. M. N. A. P. Franken, H. M. Rodermond, J. Stap, J. Haveman, and C. van Bree, “Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro,” Nat Protoc, vol. 1, no. 5, 2006. [CrossRef]

- D. R. Liston and M. Davis, “Clinically Relevant Concentrations of Anticancer Drugs: A Guide for Nonclinical Studies,” Clinical Cancer Research, vol. 23, no. 14, pp. 3489–3498, Jul. 2017. [CrossRef]

- “Sigma-Aldrich,” Millipore Sigma.

- N. A. P. Franken, H. M. N. A. P. Franken, H. M. Rodermond, J. Stap, J. Haveman, and C. van Bree, “Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro,” Nat Protoc, vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 2315–2319, Dec. 2006. [CrossRef]

- N. A. P. Franken, H. M. N. A. P. Franken, H. M. Rodermond, J. Stap, J. Haveman, and C. van Bree, “Clonogenic assay of cells in vitro,” Nat Protoc, vol. 1, no. 5, pp. 2315–2319, Dec. 2006. [CrossRef]

- N. Brix, D. N. Brix, D. Samaga, R. Hennel, K. Gehr, H. Zitzelsberger, and K. Lauber, “The clonogenic assay: robustness of plating efficiency-based analysis is strongly compromised by cellular cooperation,” Radiation Oncology, vol. 15, no. 1, p. 248, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Munshi, M. Hobbs, and R. E. Meyn, “Clonogenic cell survival assay.,” Methods Mol Med, vol. 110, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Giaever and C., R. Keese, “Micromotion of mammalian cells measured electrically.,” Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, vol. 88, no. 17, pp. 7896–900, Sep. 1991, Accessed: Jan. 09, 2019. [Online]. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1881923.

- Renken, C. Keese, and I. Giaever, “Automated assays for quantifying cell migration,” Biotechniques, vol. 49, no. 5, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Wegener, C. R. Keese, and I. Giaever, “Electric cell-substrate impedance sensing (ECIS) as a noninvasive means to monitor the kinetics of cell spreading to artificial surfaces,” Exp Cell Res, vol. 259, no. 1, pp. 158–166, Aug. 2000. [CrossRef]

- M. Merrick et al., “In vitro radiotherapy and chemotherapy alter migration of brain cancer cells before cell death,” Biochem Biophys Rep, vol. 27, p. 101071, Sep. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Walter et al., “Development of In Vitro Assays for Advancing Radioimmunotherapy against Brain Tumors,” Biomedicines, vol. 10, no. 8, p. 1796, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- “What is ANOVA (Analysis of Variance) and What Can I Use it For?,” Qualtrics.

- C. M. van Leeuwen et al., “The alfa and beta of tumours: a review of parameters of the linear-quadratic model, derived from clinical radiotherapy studies,” Radiation Oncology, vol. 13, no. 1, p. 96, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. B. Guerra et al., “Intercomparison of radiosensitization induced by gold and iron oxide nanoparticles in human glioblastoma cells irradiated by 6 MV photons,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 9602, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. M. Brush, P. A. Watson, N. A. Cacalano, K. S. Iwamoto, and W. H. McBride, “Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor vIII Expression in U87 Glioblastoma Cells Alters Their Proteasome Composition, Function, and Response to Irradiation,” Molecular Cancer Research, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 426–434, Mar. 2008. [CrossRef]

- T. Chew et al., “The radiobiological effects of He, C and Ne ions as a function of LET on various glioblastoma cell lines,” J Radiat Res, vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 178–188, Mar. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Merrick, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; et al. , “Radiotherapy and chemotherapy alter migration of brain cancer cells before cell death,” bioRxiv, p. 2020.07.23.218636, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. H. Djam, B. H. K. H. Djam, B. H. Lee, S. Suresh, and A. E. Ekpenyong, “Quantum Dots for Assessment of Reactive Oxygen Species Accumulation During Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy,” Humana, New York, NY, 2020, pp. 293–303. [CrossRef]

- B. H. Lee, S. B. H. Lee, S. Suresh, and A. Ekpenyong, “Fluorescence intensity modulation of CdSe/ZnS quantum dots assesses reactive oxygen species during chemotherapy and radiotherapy for cancer cells,” J Biophotonics, vol. 12, no. 2, p. e201800172, Dec. 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Perini et al., “Functionalized Graphene Quantum Dots Modulate Malignancy of Glioblastoma Multiforme by Downregulating Neurospheres Formation,” C (Basel), vol. 7, no. 1, p. 4, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. Perini et al., “Enhanced chemotherapy for glioblastoma multiforme mediated by functionalized graphene quantum dots,” Materials, vol. 13, no. 18, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- L. Qi et al., “Biocompatible nucleus-targeted graphene quantum dots for selective killing of cancer cells via DNA damage,” Commun Biol, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1–12, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. Ruan et al., “Graphene Quantum Dots for Radiotherapy,” ACS Appl Mater Interfaces, vol. 10, no. 17, 2018. [CrossRef]

- G. Perini et al., “Enhanced Chemotherapy for Glioblastoma Multiforme Mediated by Functionalized Graphene Quantum Dots,” Materials, vol. 13, no. 18, p. 4139, Sep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, I. S. S. Wang, I. S. Cole, and Q. Li, “The toxicity of graphene quantum dots,” RSC Adv, vol. 6, no. 92, pp. 89867–89878, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A. P. Franken et al., “Cell survival and radiosensitisation: Modulation of the linear and quadratic parameters of the LQ model,” Int J Oncol, vol. 42, no. 5, pp. 1501–1515, May 2013. [CrossRef]

- L. Barazzuol et al., “In Vitro Evaluation of Combined Temozolomide and Radiotherapy Using X Rays and High-Linear Energy Transfer Radiation for Glioblastoma,” Radiat Res, vol. 177, no. 5, pp. 651–662, May 2012. [CrossRef]

- R. Stupp et al., “Radiotherapy plus Concomitant and Adjuvant Temozolomide for Glioblastoma,” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 352, no. 10, pp. 987–996, Mar. 2005. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).