Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

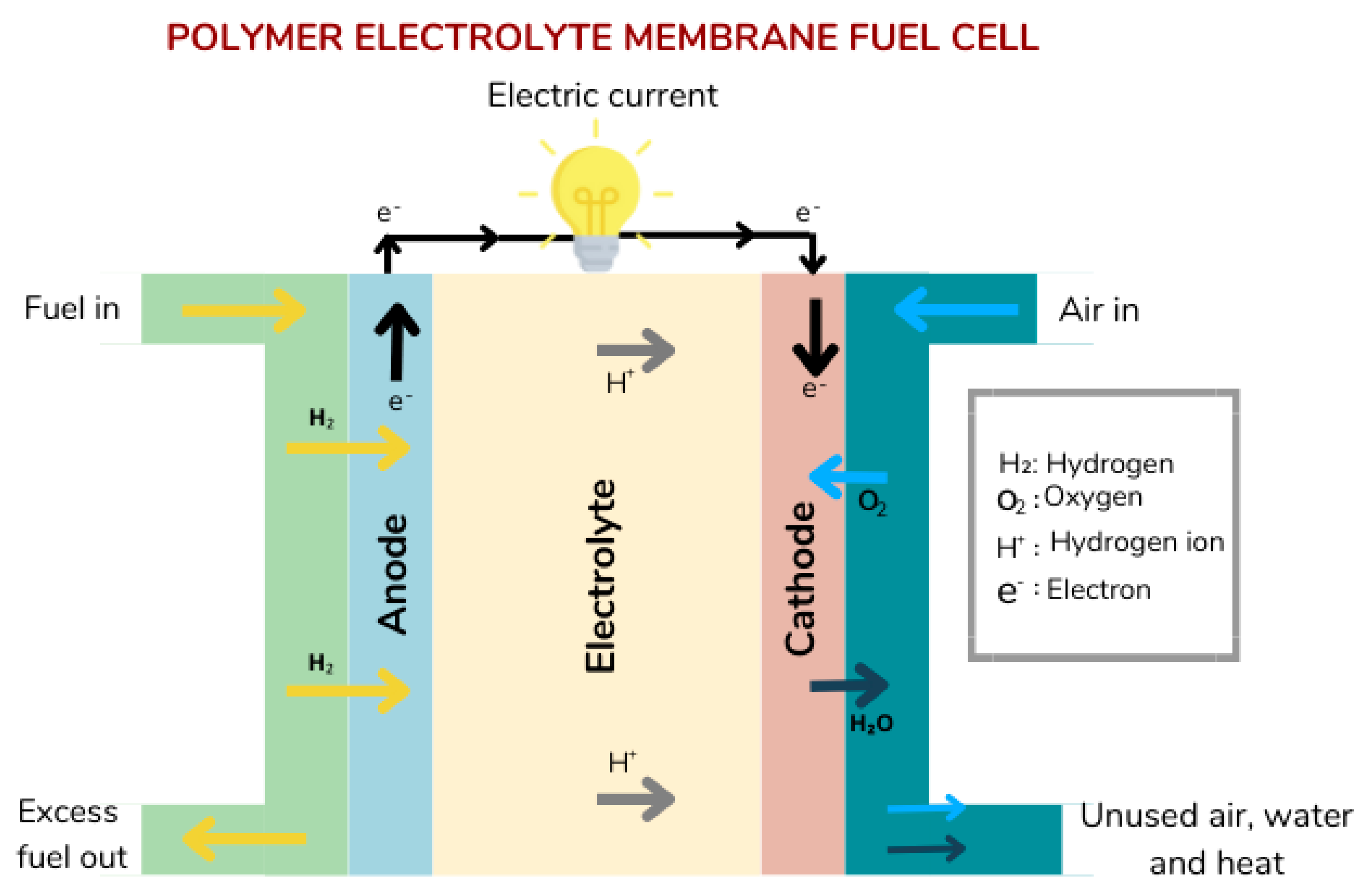

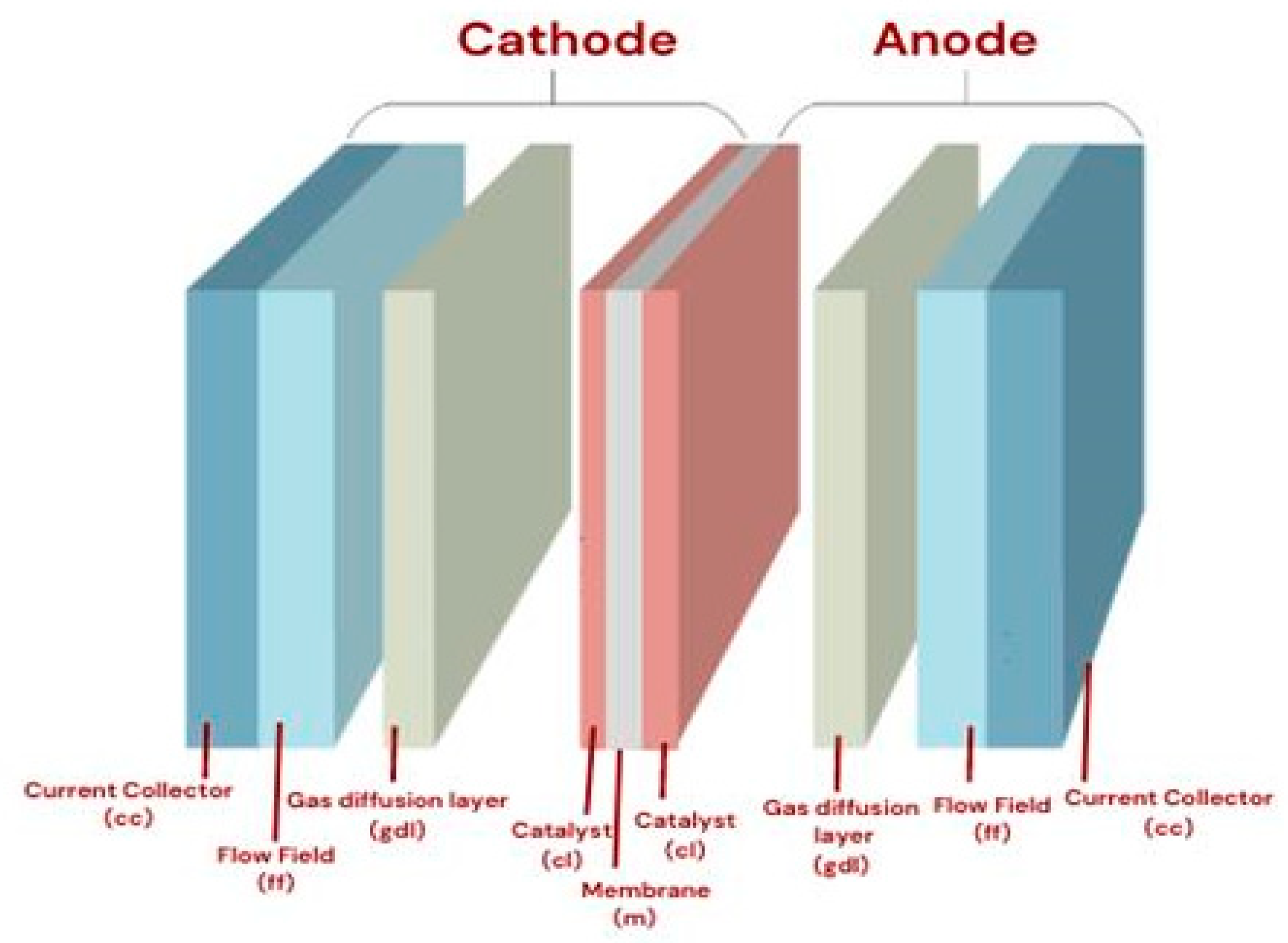

2. Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs)

| Catalyst Type | Advantage | Disadvantages | Recent Progress and Ongoing Research for Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platinum-based catalyst |

|

|

|

| Platinum free Catalyst |

|

|

|

| Alloy-Based electrocatalyst |

|

|

|

| Single atom catalyst |

|

|

|

| Metal free catalyst |

|

|

|

3. Discussions

4. Recommendation

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kordesch, K.V.; Simader, G.R. Environmental Impact of Fuel Cell Technology. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Diaz, D.F.R.; Chen, K.S.; Wang, Z.; Adroher, X.C. Materials, technological status, and fundamentals of PEM fuel cells—A review. Mater. Today 2020, 32, 178–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabi, A.S.; Popoola, A.P.I.; Popoola, O.M.; Mathe, N.R.; Abdulwahab, M. Materials for electrocatalysts in proton exchange membrane fuel cell: A brief review. Front. Energy Res. 2023, 11, 1091105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, D.K.; Filipponi, M.; Di Schino, A.; Rossi, F.; Castaldi, J. Corrosion behaviour of high temperature fuel cells: Issues for materials selection. Metalurgija 2019, 58, 347–351. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Aili, D.; Lu, S.; Li, Q.; Jiang, S.P. Advancement toward Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells at Elevated Temperatures. Research 2020, 2020, 9089405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Seo, B.; Wang, B.; Zamel, N.; Jiao, K.; Adroher, X.C. Fundamentals, materials, and machine learning of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell technology. Energy AI 2020, 1, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, B.; Yang, D.; Lv, H.; Xiao, Q.; Ming, P.; Wei, X.; Zhang, C. Highly efficient, cell reversal resistant PEMFC based on PtNi/C octahedral and OER composite catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 8930–8940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, K.S.; Mishler, J.; Cho, S.C.; Adroher, X.C. A review of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells: Technology, applications, and needs on fundamental research. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 981–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffell, I. Zero carbon infinite COP heat from fuel cell CHP. Appl. Energy 2015, 147, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- energy ID-I journal of hydrogen, 2002. Technical, environmental and exergetic aspects of hydrogen energy systems. Elsevier n.d.

- Wang, Y.; Chen, K.S.; Mishler, J.; Cho, S.C.; Adroher, X.C. A review of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells: Technology, applications, and needs on fundamental research. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 981–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundmacher, K. Fuel Cell Engineering: Toward the Design of Efficient Electrochemical Power Plants. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 10159–10182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, B.; Mamaghani, A.H.; Rinaldi, F.; Casalegno, A. Fuel partialization and power/heat shifting strategies applied to a 30 kW el high temperature PEM fuel cell based residential micro cogeneration plant. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 14224–14234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandan, A.; Hattenberger, M.; El-Kharouf, A.; Du, S.; Dhir, A.; Self, V.; Pollet, B.G.; Ingram, A.; Bujalski, W. High temperature (HT) polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells (PEMFC)—A review. J. Power Sources 2013, 231, 264–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuppala, R.K.S.S.; Chaedir, B.A.; Jiang, L.; Chen, L.; Aziz, M.; Sasmito, A.P. Optimization of Membrane Electrode Assembly of PEM Fuel Cell by Response Surface Method. Molecules 2019, 24, 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dupuis, A.C. Proton exchange membranes for fuel cells operated at medium temperatures: Materials and experimental techniques. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2011, 56, 289–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talukdar, K.; Gazdzicki, P.; Friedrich, K.A. Comparative investigation into the performance and durability of long and short side chain ionomers in Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells. J. Power Sources 2019, 439, 227078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bapat, S.; Giehl, C.; Kohsakowski, S.; Peinecke, V.; Schäffler, M.; Segets, D. On the state and stability of fuel cell catalyst inks. Adv. Powder Technol. 2021, 32, 3845–3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantillo, N.M.; Zawodzinski, T.A. Effect of Carbon Structure and Ink Composition on 3M Ionomer Adsorption. ECS Meet. Abstr. 2020, MA2020-01, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, S.; Orfanidi, A.; Schmies, H.; Anke, B.; Nong, H.N.; Hübner, J.; Gernert, U.; Gliech, M.; Lerch, M.; Strasser, P. Ionomer distribution control in porous carbon-supported catalyst layers for high-power and low Pt-loaded proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Nat. Mater. 2019, 19, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Zhao, C.; Sun, F.; Fan, J.; Li, H.; Wang, H. Research progress of catalyst layer and interlayer interface structures in membrane electrode assembly (MEA) for proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) system. eTransportation 2020, 5, 100075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Li, J.; Xiong, D.; Xu, J. Carbon corrosion behaviors and the mechanical properties of proton exchange membrane fuel cell cathode catalyst layer. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 23519–23525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M. Characterization of gas transport phenomena in gas diffusion layers in a membrane fuel cell. 2020.

- Wang, Y.; Diaz, D.F.; Chen, K.S.; Wang, Z.; Adroher, X.C. Materials, technological status, and fundamentals of PEM fuel cells–a review. Mater. Today 2020, 32, 178–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niblett, D.; Mularczyk, A.; Niasar, V.; Eller, J.; Holmes, S. Two-phase flow dynamics in a gas diffusion layer - gas channel - microporous layer system. J. Power Sources 2020, 471, 228427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, L.M.; Mitra, S.K.; Secanell, M. Absolute permeability and Knudsen diffusivity measurements in PEMFC gas diffusion layers and micro porous layers. J. Power Sources 2012, 206, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, A.; Wang, H.; Yuan, X.Z.; Zhang, J.; Wilkinson, D.P. Degradation of polymer electrolyte membranes. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2006, 31, 1838–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yoshikawa, Y.; Matsuura, T.; Islam, N.; Hori, M. Preparing Gas-Diffusion Layers of PEMFCs with a Dry Deposition Technique. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2005, 8, A152–A155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamel, N.; Li, X.; Shen, J.; Becker, J.; Wiegmann, A. Estimating effective thermal conductivity in carbon paper diffusion media. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2010, 65, 3994–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Aldave, S.; Andreoli, E. Fundamentals of gas diffusion electrodes and electrolysers for carbon dioxide utilisation: Challenges and opportunities. Catalysts 2020, 10, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.Z.; Newman, J. Coupled Thermal and Water Management in Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, A2205–A2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niblett, D.; Mularczyk, A.; Niasar, V.; Eller, J.; Holmes, S. Two-phase flow dynamics in a gas diffusion layer - gas channel - microporous layer system. J. Power Sources 2020, 471, 228427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, Y.; McMurtrey, M.D.; Jerred, N.D.; Liou, F.; Li, J. Additive manufacturing for energy: A review. Appl. Energy 2020, 282, 116041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.; Ming, P.; Yang, D.; Zhang, C. Stainless steel bipolar plates for proton exchange membrane fuel cells: Materials, flow channel design and forming processes. J. Power Sources 2020, 451, 227783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, H.; Hung, Y.; Mahajan, D. Metal bipolar plates for PEM fuel cell—A review. J. Power Sources 2006, 163, 755–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simaafrookhteh, S.; Khorshidian, M.; Momenifar, M. Fabrication of multi-filler thermoset-based composite bipolar plates for PEMFCs applications: Molding defects and properties characterizations. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2020, 45, 14119–14132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Sui, P.; Djilali, N. Dynamic behaviour of liquid water emerging from a GDL pore into a PEMFC gas flow channel. J. Power Sources 2007, 172, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Meng, X.; Li, X.; Liang, W.; Huang, W.; Chen, K.; Chen, J.; Xing, C.; Qiu, M.; Zhang, B.; et al. Two-Dimensional Borophene: Properties, Fabrication, and Promising Applications. Research 2020, 2020, 2624617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousfi-Steiner, N.; Moçotéguy, P.; Candusso, D.; Hissel, D.; Hernandez, A.; Aslanides, A. A review on PEM voltage degradation associated with water management: Impacts, influent factors and characterization. J. Power Sources 2008, 183, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Wang, H.; Yuan, X.Z.; Martin, J.J.; Luo, Z.; Pan, M. Measurement of the water transport rate in a proton exchange membrane fuel cell and the influence of the gas diffusion layer. J. Power Sources 2008, 185, 1267–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yuan, X.; Wang, H.; Mérida, W.; Zhu, H.; Shen, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, J. A review of accelerated stress tests of MEA durability in PEM fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 34, 388–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, M.P.; Bonville, L.J.; Kunz, H.R.; Slattery, D.K.; Fenton, J.M. Fuel Cell Perfluorinated Sulfonic Acid Membrane Degradation Correlating Accelerated Stress Testing and Lifetime. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 6075–6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Gyergyek, S.; Li, Q.; Andersen, S.M. Evolution of the degradation mechanisms with the number of stress cycles during an accelerated stress test of carbon supported platinum nanoparticles. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 838, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Li, Q.; Yu, X.; Chen, L.; Li, H. Approaching Practically Accessible Solid-State Batteries: Stability Issues Related to Solid Electrolytes and Interfaces. Chem. Rev. 2019, 120, 6820–6877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Yuan, X.; Wang, H.; Mérida, W.; Zhu, H.; Shen, J.; Wu, S.; Zhang, J. A review of accelerated stress tests of MEA durability in PEM fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2008, 34, 388–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dafalla, A.M.; Jiang, F. Stresses and their impacts on proton exchange membrane fuel cells: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2018, 43, 2327–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.-H.; Mittelsteadt, C.K.; Gittleman, C.S.; Dillard, D.A. Viscoelastic Stress Model and Mechanical Characterization of Perfluorosulfonic Acid (PFSA) Polymer Electrolyte Membranes. In Proceedings of the ASME 2005 3rd International Conference on Fuel Cell Science, Engineering and Technology, Ypsilanti, MI, USA, 23–25 May 2008; pp. 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubler, L.; Dockheer, S.M.; Koppenol, W.H. Radical (HO•, H• and HOO•) Formation and Ionomer Degradation in Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cells. J Electrochem Soc 2011, 158, B755–B769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiraldi, D.A. Perfluorinated Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Durability. J. Macromol. Sci. Part C: Polym. Rev. 2006, 46, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotcenkov, G.; Han, S.D.; Stetter, J.R. Review of Electrochemical Hydrogen Sensors. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 1402–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Ge, J.; Uddin, A.; Zhai, Y.; Pasaogullari, U.; St-Pierre, J. Evaluation of cathode contamination with Ca2+ in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Electrochimica Acta 2018, 259, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamel, N.; Li, X. Effective transport properties for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells–with a focus on the gas diffusion layer. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2013, 39, 111–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, I.; Kocha, S.S. Examination of the activity and durability of PEMFC catalysts in liquid electrolytes. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 6312–6322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, M.; Taylor, A.; Sekol, R.; Podsiadlo, P.; Ho, P.; Kotov, N.; Thompson, L. High-Performance Nanostructured Membrane Electrode Assemblies for Fuel Cells Made by Layer-By-Layer Assembly of Carbon Nanocolloids. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 3859–3864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongkanand, A.; Mathias, M.F. The Priority and Challenge of High-Power Performance of Low-Platinum Proton-Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 1127–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natarajan, D.; Van Nguyen, T. Three-dimensional effects of liquid water flooding in the cathode of a PEM fuel cell. J. Power Sources 2003, 115, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenberg, A.; Chowdhury, A.; Fang, M.; Weber, A.Z.; Okamoto, Y.; Kusoglu, A.; Modestino, M.A. Highly Permeable Perfluorinated Sulfonic Acid Ionomers for Improved Electrochemical Devices: Insights into Structure–Property Relationships. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 3742–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.; Hao, Z.; Zhang, K.; Yan, Z.; Chen, J. Advances and Challenges for the Electrochemical Reduction of CO2 to CO: From Fundamentals to Industrialization. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 20795–20816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.; Lim, E.S.; Kim, K.-Y. Effects of channel geometry and electrode architecture on reactant transportation in membraneless microfluidic fuel cells: A review. Fuel 2021, 298, 120818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.; Choi, G.M. Novel modification of anode microstructure for proton-conducting solid oxide fuel cells with BaZr0.8Y0.2O3−δ electrolytes. J. Power Sources 2015, 285, 431–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, P.C.; Belgacem, I.B.; Emori, W.; Uzoma, P.C. Nafion degradation mechanisms in proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) system: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 27956–27973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunato, G.V.; Pizzutilo, E.; Cardoso, E.S.; Lanza, M.R.; Katsounaros, I.; Freakley, S.J.; Mayrhofer, K.J.; Maia, G.; Ledendecker, M. The oxygen reduction reaction on palladium with low metal loadings: The effects of chlorides on the stability and activity towards hydrogen peroxide. J. Catal. 2020, 389, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, J.; Shi, Z.; Holdcroft, S. Hydrocarbon proton conducting polymers for fuel cell catalyst layers. Energy Environ. Sci. 2011, 4, 1575–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gittleman, C.S.; Coms, F.D.; Lai, Y.-H. Membrane durability: physical and chemical degradation. In Polymer Electrolyte Fuel Cell Degradation; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012; pp. 15–88. [Google Scholar]

- Taghizadeh, M.T.; Vatanparast, M. Ultrasonic-assisted synthesis of ZrO2 nanoparticles and their application to improve the chemical stability of Nafion membrane in proton exchange membrane. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 483, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Y.; Yin, G.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Y. Proton exchange membrane fuel cell from low temperature to high temperature: Material challenges. J. Power Sources 2007, 167, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, K.; Xuan, J.; Du, Q.; Bao, Z.; Xie, B.; Wang, B.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, L.; Wang, H.; Hou, Z.; et al. Designing the next generation of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. Nature 2021, 595, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, C.; Xue, J.; Huang, T.; Yin, Y.; Qin, Y.; Jiao, K.; Du, Q.; Guiver, M.D. Oriented proton-conductive nano-sponge-facilitated polymer electrolyte membranes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 13, 297–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, E.H.; Jayanti, S. Thermal management strategies for a 1 kWe stack of a high temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2012, 48, 465–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Jin, W.; Xu, N. Two-Dimensional-Material Membranes: A New Family of High-Performance Separation Membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 13384–13397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oar-Arteta, L.; Wezendonk, T.; Sun, X.; Kapteijn, F.; Gascon, J. Metal organic frameworks as precursors for the manufacture of advanced catalytic materials. Mater. Chem. Front. 2017, 1, 1709–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markovic, N.; Gasteiger, H.; Ross, P.N. Kinetics of Oxygen Reduction on Pt(hkl) Electrodes: Implications for the Crystallite Size Effect with Supported Pt Electrocatalysts. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1997, 144, 1591–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Martinez, A.; Hong, P.; Xu, H.; Bockmiller, F.R. Polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cell and hydrogen station networks for automobiles: Status, technology, and perspectives. Adv. Appl. Energy 2021, 2, 100011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, S.; Simon, L.C.; Fowler, M.W. Comparison of two accelerated NafionTM degradation experiments. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2008, 93, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Jermsittiparsert, K.; Nasseri, M. An efficient terminal voltage control for PEMFC based on an improved version of whale optimization algorithm. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şengül, E.; Erdener, H.; Akay, R.G.; Yücel, H.; Baç, N.; Eroğlu, İ. Effects of sulfonated polyether-etherketone (SPEEK) and composite membranes on the proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC) performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2009, 34, 4645–4652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Lu, S.; Xiang, Y.; Jiang, S.P. Intrinsic Effect of Carbon Supports on the Activity and Stability of Precious Metal Based Catalysts for Electrocatalytic Alcohol Oxidation in Fuel Cells: A Review. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 2484–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, G. Material and Device Design for Rapid Response and Long Lifetime Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells (PEMFCs). 2018.

- Ijaodola, O.; Hassan, Z.E.; Ogungbemi, E.; Khatib, F.; Wilberforce, T.; Thompson, J.; Olabi, A. Energy efficiency improvements by investigating the water flooding management on proton exchange membrane fuel cell (PEMFC). Energy 2019, 179, 246–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosli, R.E.; Sulong, A.B.; Daud, W.R.W.; Zulkifley, M.A.; Husaini, T.; Rosli, M.I.; Majlan, E.H.; Haque, M.A. A review of high-temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cell (HT-PEMFC) system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 9293–9314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Jiao, K. Multi-phase models for water and thermal management of proton exchange membrane fuel cell: A review. J. Power Sources 2018, 391, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najjari, M.; Khemili, F.; Ben Nasrallah, S. The effects of the cathode flooding on the transient responses of a PEM fuel cell. Renew. Energy 2008, 33, 1824–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüber, K.; Pócza, D.; Hebling, C. Visualization of water buildup in the cathode of a transparent PEM fuel cell. J. Power Sources 2003, 124, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrevaya, X.C.; Sacco, N.J.; Bonetto, M.C.; Hilding-Ohlsson, A.; Cortón, E. Analytical applications of microbial fuel cells. Part I: Biochemical oxygen demand. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 63, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, S.; Wang, C.-Y. Liquid Water Formation and Transport in the PEFC Anode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2007, 154, B998–B1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berning, T.; Djilali, N. A 3D, Multiphase, Multicomponent Model of the Cathode and Anode of a PEM Fuel Cell. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2003, 150, A1589–A1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, K.S.; Mishler, J.; Cho, S.C.; Adroher, X.C. A review of polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells: Technology, applications, and needs on fundamental research. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 981–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, Z.; Wu, S.; Song, D.; Zhang, J.; Fatih, K.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; et al. A review of water flooding issues in the proton exchange membrane fuel cell. J. Power Sources 2008, 178, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Lu, G.; Wang, C.-Y. Low Crossover of Methanol and Water Through Thin Membranes in Direct Methanol Fuel Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2006, 153, A543–A553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasabe, T.; Tsushima, S.; Hirai, S. In-situ visualization of liquid water in an operating PEMFC by soft X-ray radiography. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 11119–11128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Z.; Wang, C.; Fu, W.; Pan, M. Visualization of water transport in a transparent PEMFC. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, X.Z.; Martin, J.J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Shen, J.; Wu, S.; Merida, W. A review of PEM fuel cell durability: Degradation mechanisms and mitigation strategies. J. Power Sources 2008, 184, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, A.; Weng, F.-B.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-M. Studies on flooding in PEM fuel cell cathode channels. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2006, 31, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghunath, K.V.; Reddy, B.K.; Muliankeezhil, S.; Aparna, K. Non-isothermal One-Dimensional Two-Phase Model of Water Transport in Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells with Micro-porous Layer. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2022, 48, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.L.; Han, J.; Nguyen, X.L.; Yu, S.; Goo, Y.-M.; Le, D.D. Review of the Durability of Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cell in Long-Term Operation: Main Influencing Parameters and Testing Protocols. Energies 2021, 14, 4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, B.; Yang, D.; Lv, H.; Xiao, Q.; Ming, P.; Wei, X.; Zhang, C. Highly efficient, cell reversal resistant PEMFC based on PtNi/C octahedral and OER composite catalyst. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 8930–8940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamekhorshid, A.; Karimi, G.; Noshadi, I. Current distribution and cathode flooding prediction in a PEM fuel cell. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2011, 42, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, S.; Shimpalee, S.; Van Zee, J. Three-dimensional numerical simulation of straight channel PEM fuel cells. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2000, 30, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussaini, I.S.; Wang, C.Y. Visualization and quantification of cathode channel flooding in PEM fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2009, 187, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santarelli, M.G.; Torchio, M.F.; Calı, M.; Giaretto, V. Experimental analysis of cathode flow stoichiometry on the electrical performance of a PEMFC stack. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2007, 32, 710–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.M.; Parthasarathy, V. A passive method of water management for an air-breathing proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Energy 2013, 51, 457–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carton, J.G.; Olabi, A.G. Design of experiment study of the parameters that affect performance of three flow plate configurations of a proton exchange membrane fuel cell. Energy 2010, 35, 2796–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, Z.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Wahid, K.A.A. Fuel cells as an advanced alternative energy source for the residential sector applications in Malaysia. Int. J. Energy Res. 2020, 45, 5032–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’hayre RP, Colella WG, Adams RH. FUEL CELL FUNDAMENTALS SUK-WON CHA FRITZ B. PRINZ n.d.

- Seo, S.H.; Lee, C.S. A study on the overall efficiency of direct methanol fuel cell by methanol crossover current. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 2597–2604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Hao, D.; Shen, C.; Shao, Z. Experimental investigation of the steady-state efficiency of fuel cell stack under strengthened road vibrating condition. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 3767–3772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Sui, P.; Djilali, N. Dynamic behaviour of liquid water emerging from a GDL pore into a PEMFC gas flow channel. J. Power Sources 2007, 172, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litkohi, H.R.; Bahari, A.; Gatabi, M.P. Improved oxygen reduction reaction in PEMFCs by functionalized CNTs supported Pt–M (M= Fe, Ni, Fe–Ni) bi-and tri-metallic nanoparticles as efficient. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 23543–23556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A.; Kuhn, P.; Weber, J.; Titirici, M.; Antonietti, M. Porous Polymers: Enabling Solutions for Energy Applications. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2009, 30, 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corti, H.R.; Nores-Pondal, F.; Buera, M.P. Low temperature thermal properties of Nafion 117 membranes in water and methanol-water mixtures. J. Power Sources 2006, 161, 799–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chugh, S.; Chaudhari, C.; Sonkar, K.; Sharma, A.; Kapur, G.; Ramakumar, S. Experimental and modelling studies of low temperature PEMFC performance. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 45, 8866–8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakil, F.A.; Kamarudin, S.K.; Basri, S. Modified Nafion membranes for direct alcohol fuel cells: An overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 65, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Hasan, S.M.K.; Hossain, M.I.; Das, R.C.; Bencherif, H.; Rubel, M.H.K.; Rahman, F.; Emrose, T.; Hashizume, K. A Review of Applications, Prospects, and Challenges of Proton-Conducting Zirconates in Electrochemical Hydrogen Devices. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Investigation of Nafion®/HPA composite membranes for high temperature/low relative humidity PEMFC operation.

- A simple model of a high temperature PEM fuel cell.

- Rosli, R.E.; Sulong, A.B.; Daud, W.R.W.; Zulkifley, M.A.; Husaini, T.; Rosli, M.I.; Majlan, E.H.; Haque, M.A. A review of high-temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cell (HT-PEMFC) system. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 9293–9314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimir, W.; Al-Othman, A.; Tawalbeh, M.; Al Makky, A.; Ali, A.; Karimi-Maleh, H.; Karimi, F.; Karaman, C. Approaches towards the development of heteropolyacid-based high temperature membranes for PEM fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 6638–6656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L. Polymer composites for high-temperature proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. Polym. Membr. Fuel Cells 2009, 159–184. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, V.T.; Ziolo, J.T.; Yang, Y.; Diercks, D.; Alfaro, S.M.; Hjuler, H.A.; Steenberg, T.; Herring, A.M. 12-Silicotungstic Acid Doped Phosphoric Acid Imbibed Polybenzimidazole for Enhanced Protonic Conductivity for High Temperature Fuel Cell Applications. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, F504–F513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xing, D.; Shao, Z.G. The stability of Pt/C catalyst in H3PO4/PBI PEMFC during high temperature life test. J. Power Sources 2007, 164, 126–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.O.; Kwon, K.; Cho, M.D.; Hong, S.-G.; Kim, T.Y.; Yoo, D.Y. Role of Binders in High Temperature PEMFC Electrode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2011, 158, B675–B681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y. Effect of cooling surface temperature difference on the performance of high-temperature PEMFCs. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2023, 48, 16813–16828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiti, T.K.; Singh, J.; Majhi, J.; Ahuja, A.; Maiti, S.; Dixit, P.; Bhushan, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. Advances in polybenzimidazole based membranes for fuel cell applications that overcome Nafion membranes constraints. Polymer 2022, 255, 125151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Sulong, A.; Loh, K.; Majlan, E.H.; Husaini, T.; Rosli, R.E. Acid doped polybenzimidazoles based membrane electrode assembly for high temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cell: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2017, 42, 9156–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Types of Fuel Cell | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Reversible Fuel cell |

|

|

| Molten Carbonate Fuel Cell |

|

|

| Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell |

|

|

| Direct methanol fuel cell |

|

|

| Reversible Fuel cell |

|

|

| Direct ammonia fuel cell |

|

|

| Alkaline fuel cell |

|

|

| Microbial Fuel Cells |

|

|

| Phosphoric acid fuel cell |

|

|

| Direct Propane Fuel Cell |

|

|

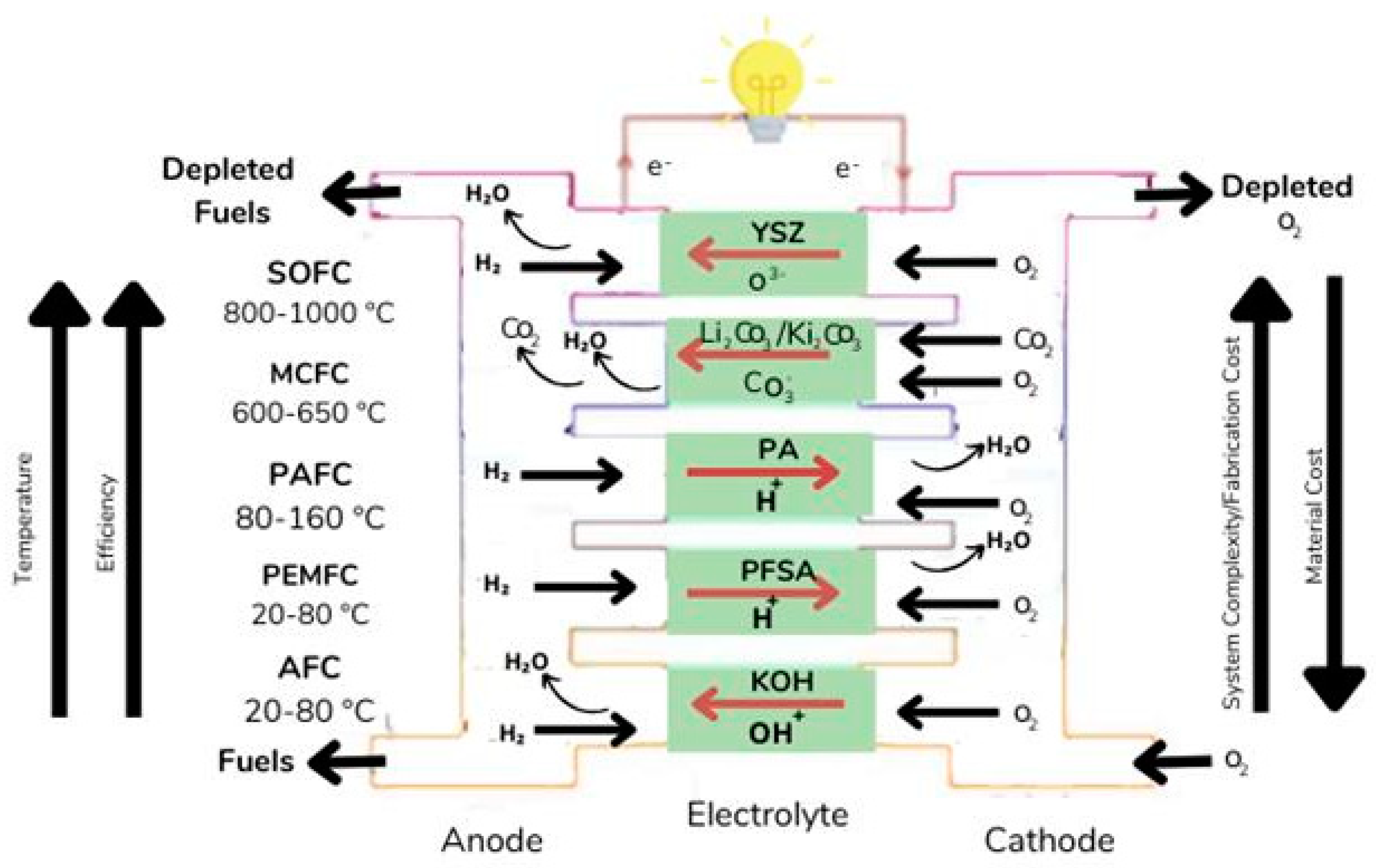

| PEMFCs | AFCs | SOFCs | MCFCs | PAFCS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte | Polymetric membrane | Potassium hydroxide | Ceramics | Molten carbonate | Phosphoric acid |

| Charge Carrier | H+ | OH- | O2- | CO32- | H+ |

| Operating temperature | -40 -1200 C | 50–200 oC | 500–1000 OC | 600–700 OC | 150–220 OC |

| Electrical efficiency | Up to 60–72% | Up to 70% | Up to 65% | Up to 60% | Up to 45% |

|

Primary fuel Primary applications |

H2 /methanol | Cracked ammonia/ H2 | Biogas/methane/ H2 | Biogas/methane/ H2 | H2/ reformed H2 |

| Shipment as of 2019 | 934.2 MW | 0 MW | 106.27 MW | 10.2 MW | 78.1 MW |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).