1. Introduction

In contemporary manufacturing, with continuous technological advancements, the precision machining and quality inspection of complex components have become core processes, with the accurate measurement and analysis of complex deep-hole internal structures being particularly crucial. Our research team previously used the annular light sectioning method to measure the diameter of steel pipe components and completed the 3D reconstruction of their internal surface point clouds [

1,

2]. The object of study is a relatively simple steel tube part with an internal structure close to a smooth bore morphology, which is suitable for the application of existing algorithms such as Steger, Canny, Sobel, Prewitt, Roberts, etc. [

3,

4,

5] to extract the contour of the annular laser beam quickly and accurately. However, this write-up algorithm faces many challenges when applied to the detection of inner walls with complex geometries (e.g., internal gears, splines, gun barrel bore, etc.) [

6]. The internal walls of these components have complex geometries, with surface roughness, machining tool marks, and surface reflection characteristics, all of which can alter the interaction between the laser and the material, resulting in uneven laser energy distribution and discontinuous laser stripes [

7]. Due to the combined effects of the internal wall’s complex shape and material properties, the laser stripes exhibit unpredictable and highly variable characteristics, significantly increasing the difficulty of subsequent laser stripe centerline extraction [

8].

In traditional methods, such as applying the Steger algorithm to extract the laser stripe centerlines of complex internal shapes (e.g., lobed, internal gears, splines, internal octagonal shapes, etc.), issues such as burrs, low-frequency noise, and redundant branches commonly arise. These issues significantly affect the accuracy and completeness of the extraction results, failing to meet the requirements for high-precision measurement and accurate analysis of complex components [

9]. Building on previous research, our team used self-developed deep-hole detection equipment to capture laser stripe images of the internal surfaces of various deep-hole components, applying the Steger algorithm for point cloud extraction of laser stripes of different shapes. Experimental results indicated that while the Steger algorithm is suitable for extracting simple laser stripes, its performance degrades when applied to complex laser stripes, often generating low-frequency random noise signals. These signals, with small amplitudes and close to the variations of the measured surface, manifest as burrs or erratic branching points [

10]. Nevertheless, the Steger algorithm still retains detail information of the contours during the overall extraction process, yet automatically identifying the precise centerline of the laser stripes from noise and subpixel point cloud data remains a significant challenge in the field of complex laser stripe extraction [

11]. Traditional methods typically rely on manual noise removal to obtain a complete contour, which is time-consuming and prone to human error, thereby affecting the accuracy of subsequent feature parameter calculations and 3D reconstruction.

To address this issue, this study proposes an efficient alternative method aimed at automatically extracting complete contour curves from noisy point cloud data, with the goal of providing an effective solution for precise extraction of complex contours. Currently, research in laser stripe extraction often relies on adaptive improvements to existing mature algorithms. Typical improvements include the enhanced Hessian matrix [

12,

13], gray gravity method [

14], DBSCAN [

15], adaptive bidirectional grayscale methods [

16], and adaptive convolution techniques [

17,

18,

19]. While these methods have shown some success in specific tasks, their widespread application in industry remains unverified, and they often require further optimization and adjustment in practical applications, making it difficult to achieve breakthrough progress.

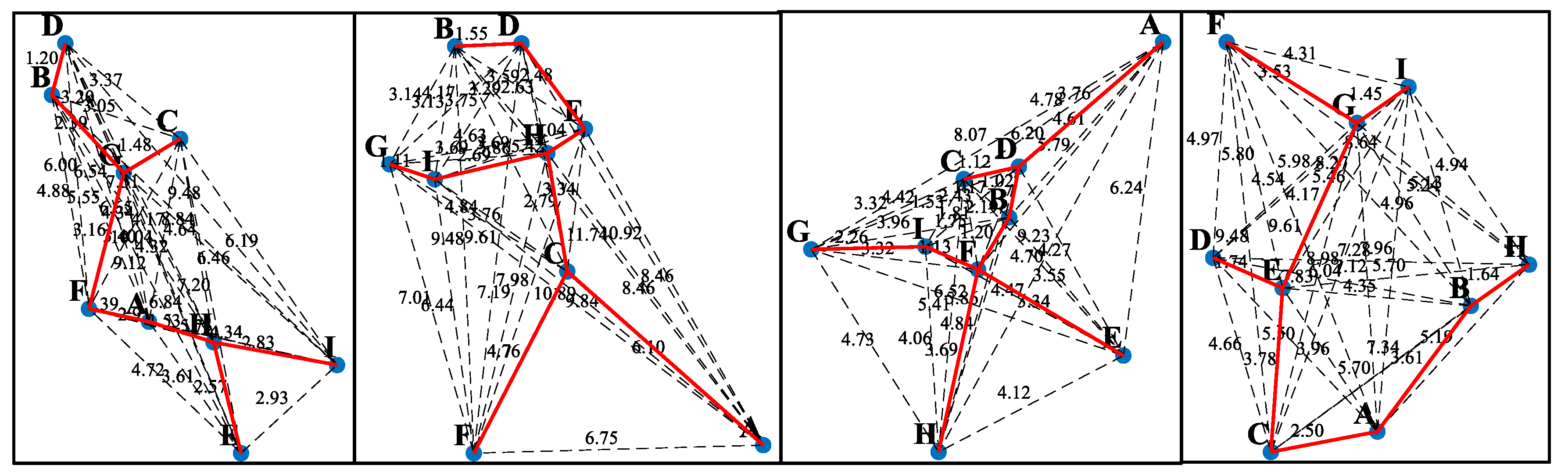

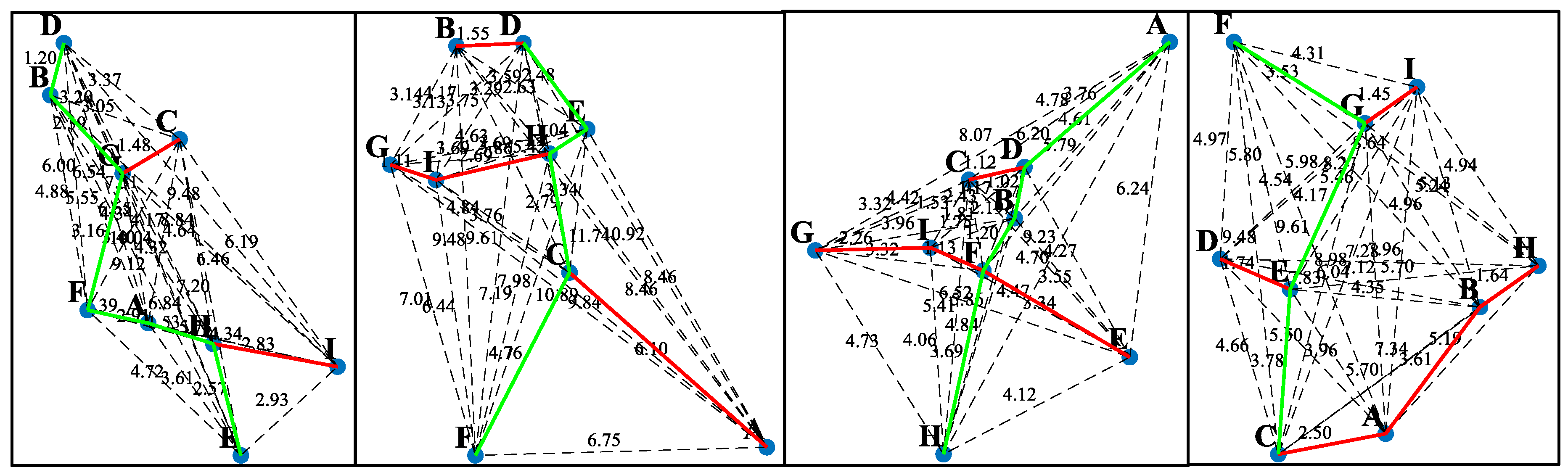

In this context, this study innovatively proposes a laser stripe centerline extraction method based on minimum spanning tree (MST) with depth-first search (DFS) for complex deep bore internal cavities. The study begins by using the Steger algorithm to generate a subpixel point cloud model containing noise, followed by the application of MST and DFS for main contour searching and tracking. This approach effectively removes interference from point cloud data, accurately obtaining the point cloud coordinates of the laser stripe’s geometric center. The method fully exploits the MST’s advantage in constructing an effective connectivity structure of point cloud data, ensuring reasonable connections between points, and combines the traversal and pathfinding capabilities of DFS to precisely search and track the main contour. This approach acts as an efficient noise filter, systematically removing burrs, erratic branches, and other noise points, thereby ultimately and accurately obtaining the point cloud coordinates of the laser stripe’s geometric center. This provides reliable data support for subsequent feature parameter calculations, 3D reconstruction, and further analysis [

20].

2. Analysis of Laser Stripe Characteristics in Complex Deep-Hole Geometries

In the field of image processing, HALCON is a commercially available computer vision software library that has been widely validated through industrial applications, demonstrating excellent reliability and efficiency. The linesgauss operator in HALCON, based on the core of the Steger algorithm, Sis capable of effectively detecting various geometric shapes, such as straight lines, curves, arcs, elliptical arcs, and waveforms. This algorithm is an efficient line feature extraction method, particularly outstanding in applications that require high precision and subpixel-level edge detection. In the previous research, Steger algorithm was successfully applied to the point cloud extraction of the laser stripe centerline on the inner surface of a deep hole part, and significant results were achieved. Therefore, this study first applies the Steger algorithm to extract the laser stripe centerlines from contours of varying complexities, aiming to investigate the performance of the algorithm in such applications.

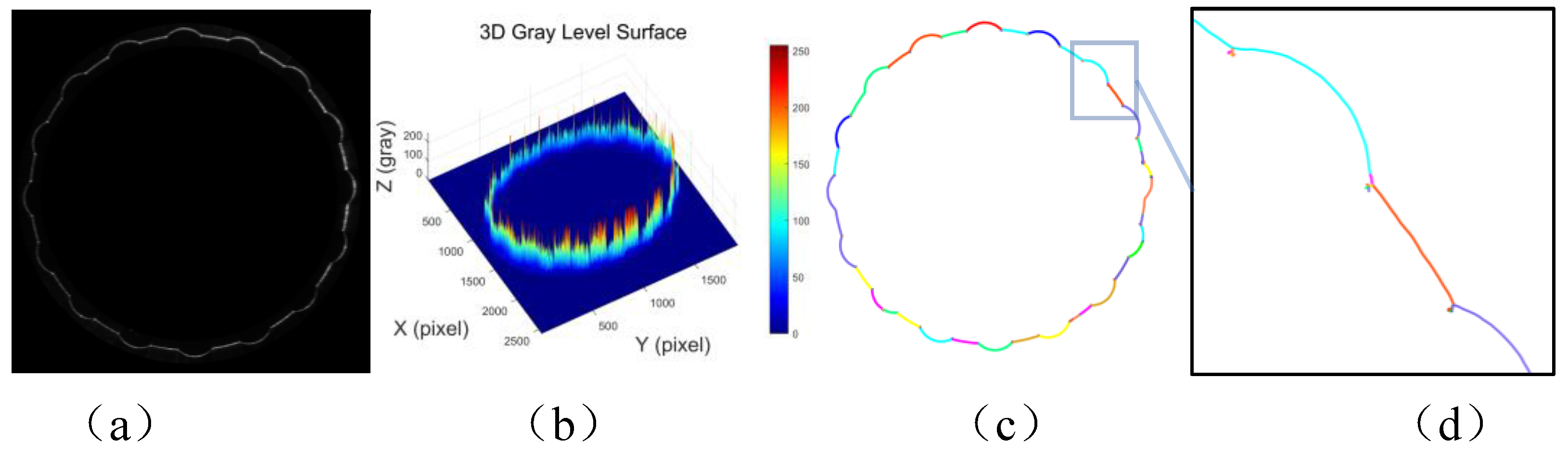

Figure 1 (a) shows the laser stripe image of a smooth deep hole, while

Figure 1 (b) presents a 3D intensity distribution of the grayscale values from the image. It is evident from the figure that the laser stripe is uniformly distributed and has a simple contour shape.

Figure 1 (c) shows the result of the laser stripe centerline extraction using the Steger algorithm, and

Figure 1 (d) is a local zoomed-in view of the extracted result. From these results, it is clear that the Steger algorithm performs well in extracting the centerline of laser stripes with simple contours. The algorithm accurately extracts a subpixel contour curve, facilitating subsequent contour feature parameter calculations and 3D reconstruction.

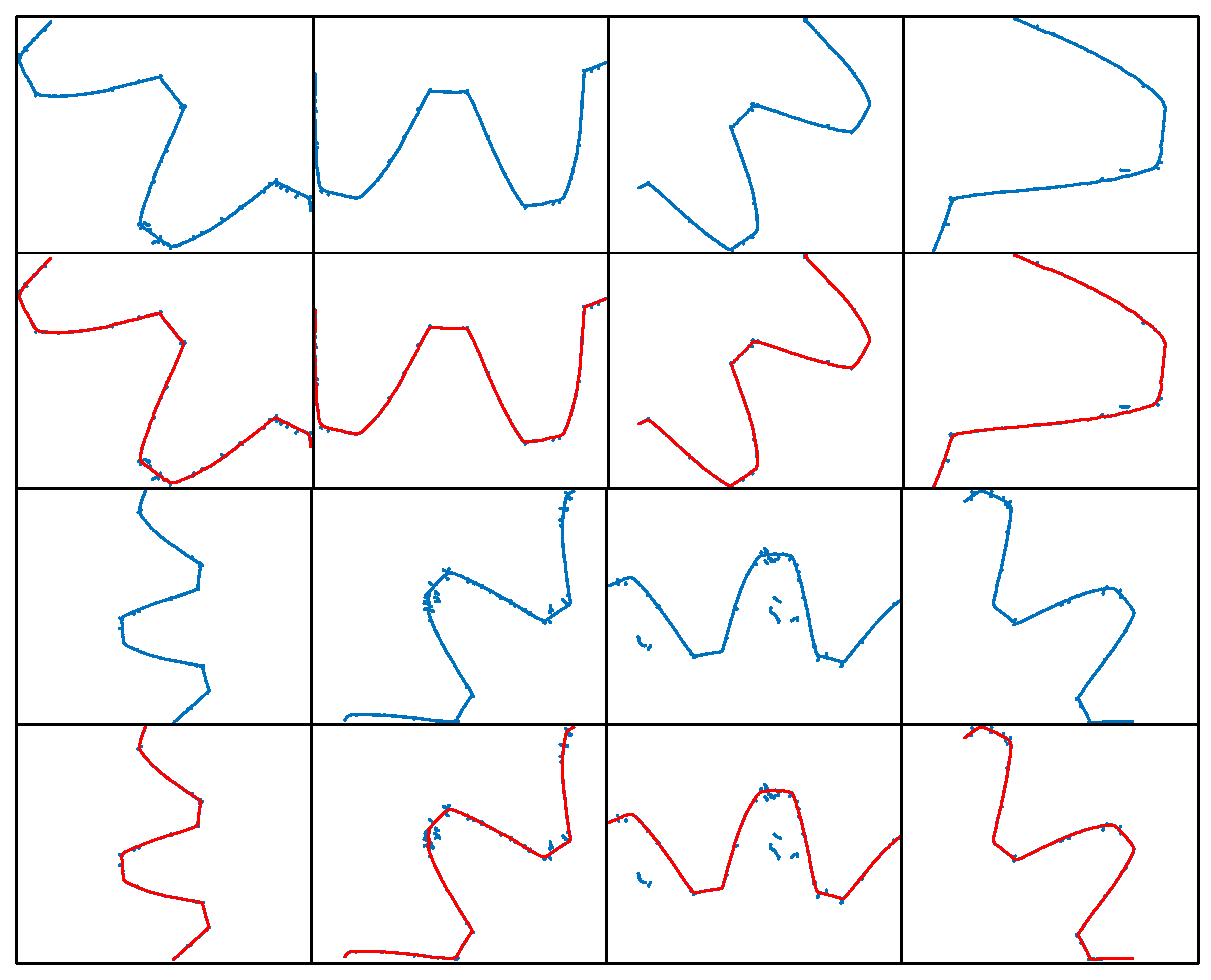

Figure 2 (a) shows an image of the contour of the flap laser stripe, which exhibits an annular distribution consisting of a combination of straight lines and circular arcs.

Figure 2(b), on the other hand, shows the three-dimensional distribution of the gray intensity of this image. It can be observed that there is an obvious abrupt change in the gray intensity at the junction of straight lines and circular arcs, which leads to an uneven energy distribution of the laser stripes.

Figure 2(c) demonstrates the results of the laser stripe centerline extracted using Steger’s algorithm (after optimizing the parameters), and

Figure 2(d) is a local zoomed-in view of the laser stripe center extraction results. It can be clearly seen that the algorithm identifies multiple line segments, and the figure distinguishes the extracted line segments with different colors, which is again very different from the extraction result of the laser stripe centerline of the smooth hole in

Figure 2(c) above, and there are many burr noises in the junction of the straight line and the circular arc. This kind of gray scale mutation easily causes Steger’s algorithm to misidentify the pseudo edges, which poses a challenge to the extraction of the centerline.

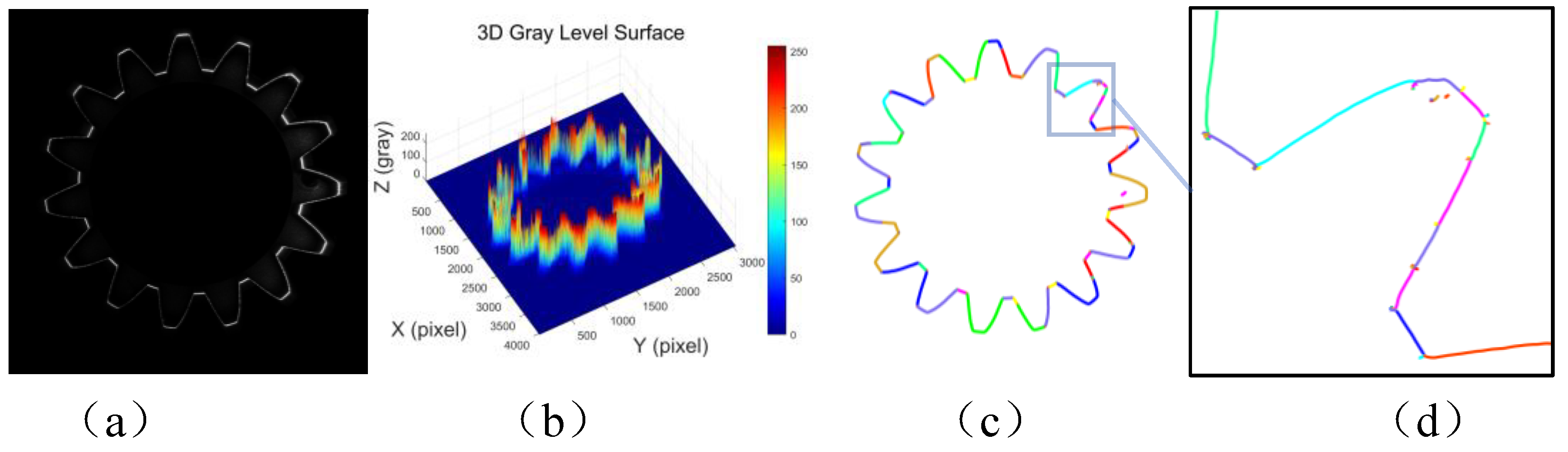

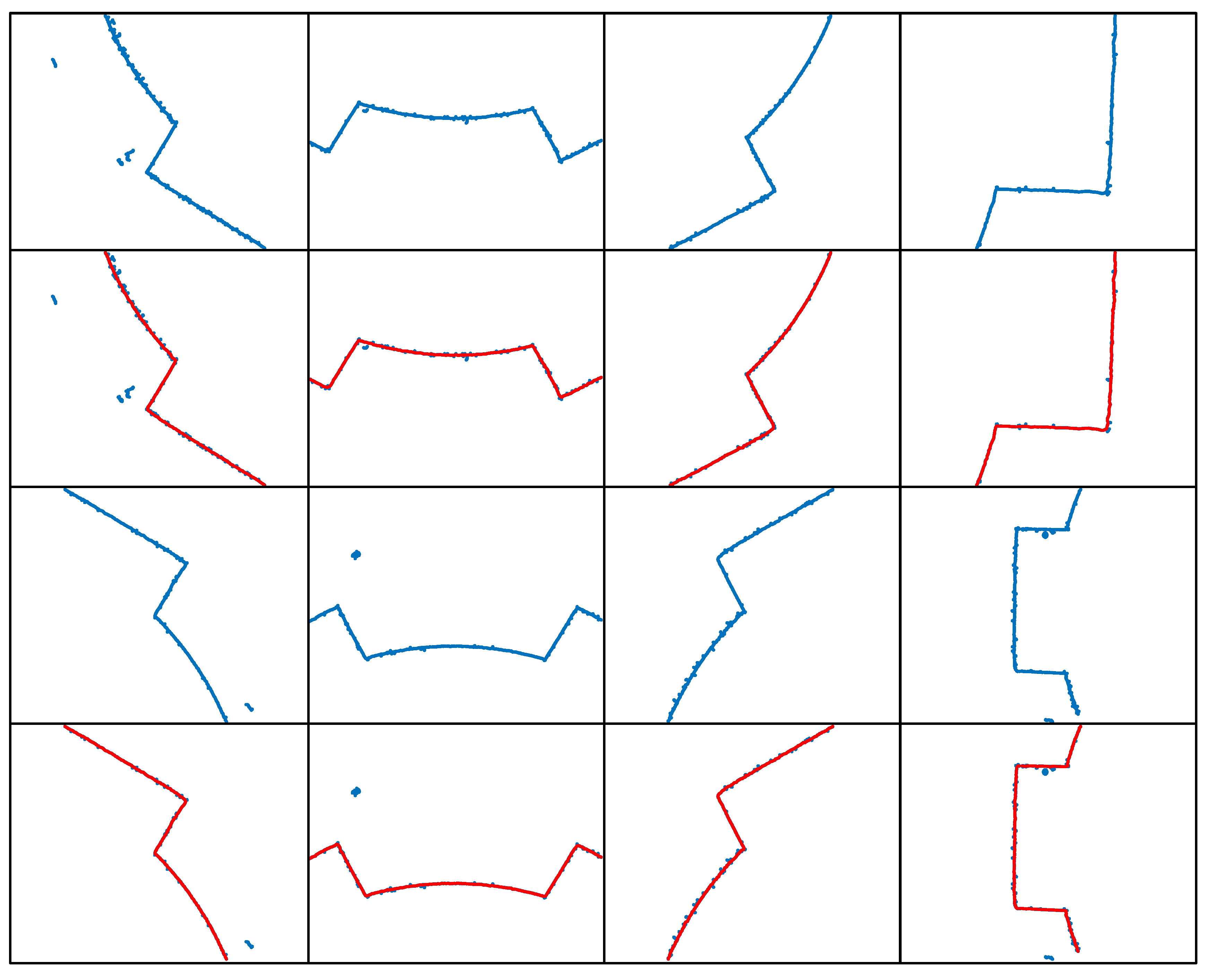

This The inner surface of an internal gear has a complex shape and can be considered as one of the representatives for the extraction of complex laser stripe centerlines.

Figure 3 (a) shows the grayscale image of the laser stripes on the inner surface of the internal gear. It can be observed that the laser stripe intensity distribution is uneven, with alternating light and dark areas, which significantly differs from the laser stripe grayscale image of the smooth deep hole surface.

Figure 3 (b) presents the 3D intensity distribution of the laser stripes on the internal gear. From the figure, it is clear that there is a significant grayscale intensity difference between the tooth crest, tooth root, and the involute surface. The laser stripe intensity is higher on the tooth crest and tooth root, while the intensity on the involute surface is relatively lower. The main reason for this phenomenon lies in the fact that the optical flux generated by the annular laser beam is uniform within a unit angle. However, within the same angular range, the length of the involute curve is greater than that of the tooth crest and tooth root curves, resulting in lower optical intensity per unit length on the involute curve, and higher intensity on the tooth crest and tooth root curves. Additionally, the variation in laser stripe grayscale intensity is influenced by factors such as surface roughness, machining tool marks, and surface reflectivity.

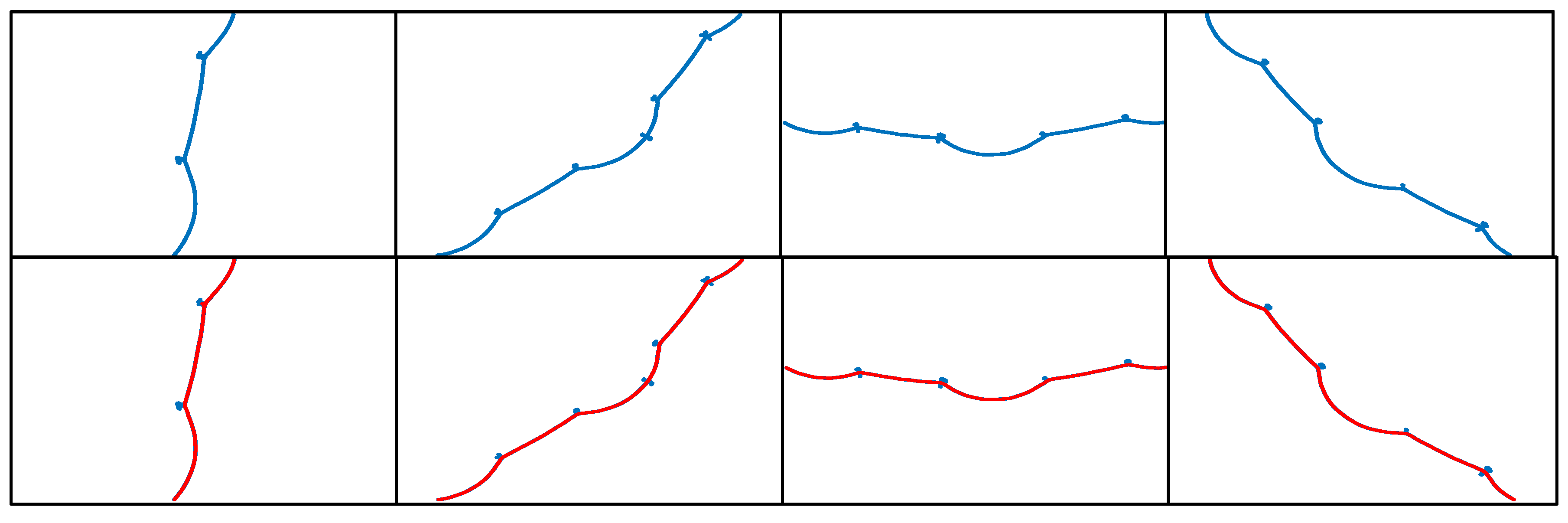

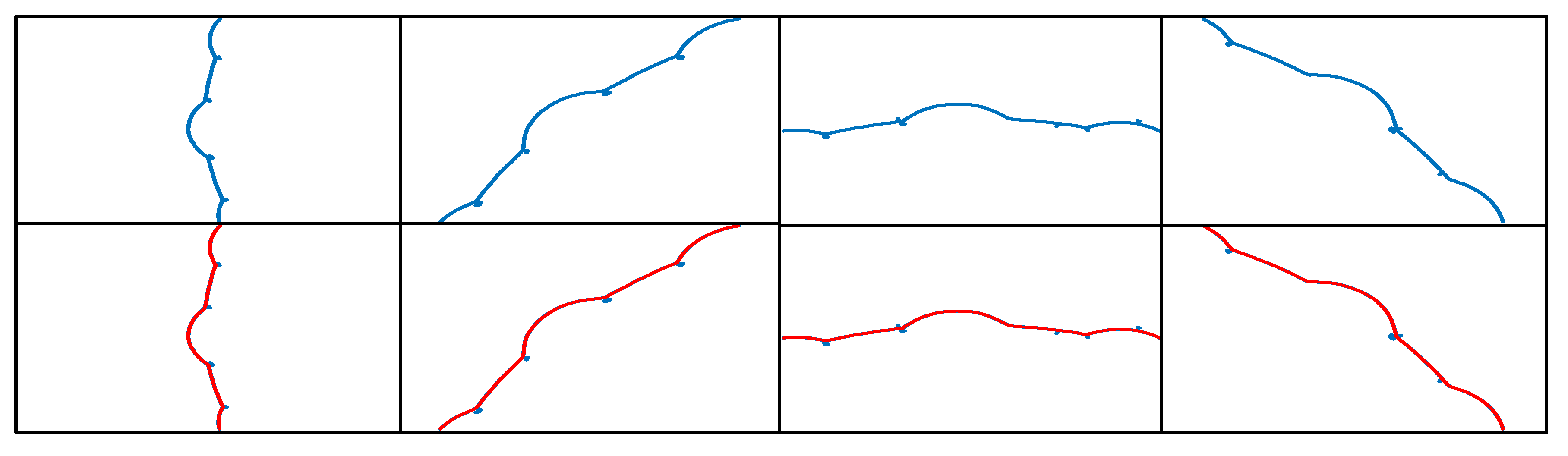

Figure 3 (c) shows the result of the laser stripe centerline extraction on the internal gear using the Steger algorithm, and

Figure 3 (d) provides a local zoom-in of the extracted result. It can be clearly seen that the algorithm identifies multiple line segments, distinguishing them by different colors. However, in the zoomed-in subpixel point cloud, numerous noise points can be observed, appearing as burrs or chaotic branch points. Despite this, the overall extraction effectively retains the detailed information of the internal gear contour. By manually removing the noise points, a complete contour of the internal gear can be obtained.

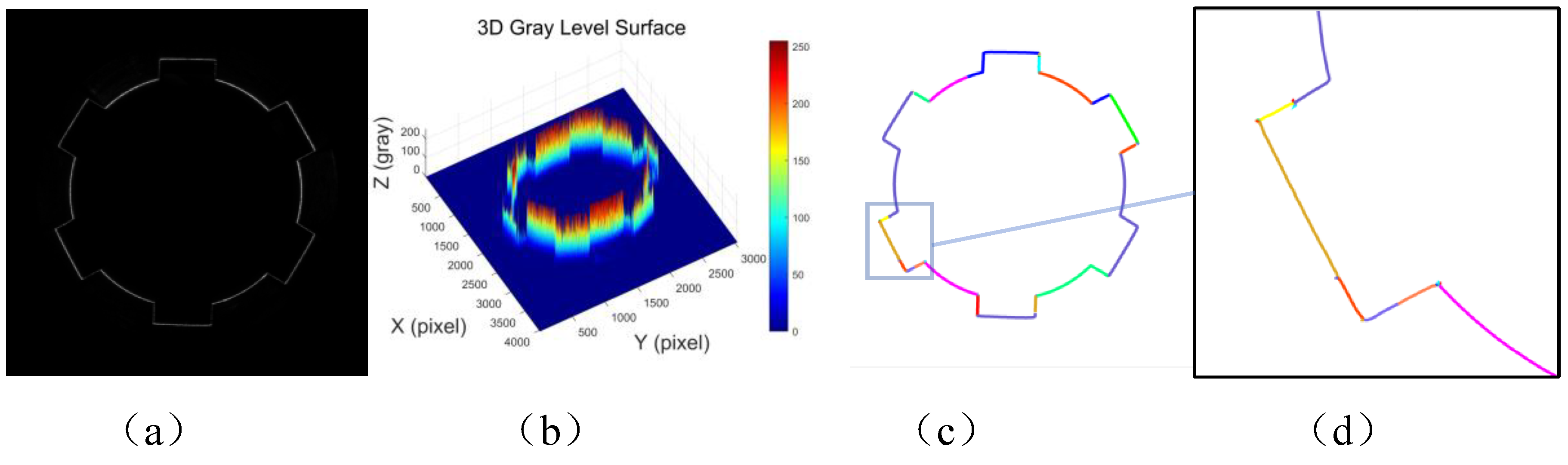

Figure 4 (a) shows the grayscale image of the laser stripes on the surface of a rectangular spline. From the image, it can be observed that the laser stripe intensity distribution is similar to that of the internal gear surface.

Figure 4 (b) displays the 3D intensity distribution of the laser stripes on the rectangular spline. It is clearly evident that the laser stripe intensity is higher in the arc regions, while the intensity is relatively lower in the rectangular keyway areas. This phenomenon is similar to the behavior observed in the internal gear laser stripes and is mainly influenced by a combination of factors, including the inner surface profile shape, surface roughness, machining tool marks, and surface reflectivity.

Figure 4 (c) presents the result of laser stripe centerline extraction on the rectangular spline using the Steger algorithm, and

Figure 4 (d) shows a local zoom-in of the extracted result. From the images, it is clear that the algorithm successfully identifies multiple line segments, with different colors representing different segments. However, in the zoomed-in subpixel point cloud, a large number of noise points can be observed, which primarily appear as burrs or chaotic branch points. Despite this, the overall extraction process retains the detailed information of the rectangular spline contour quite effectively.

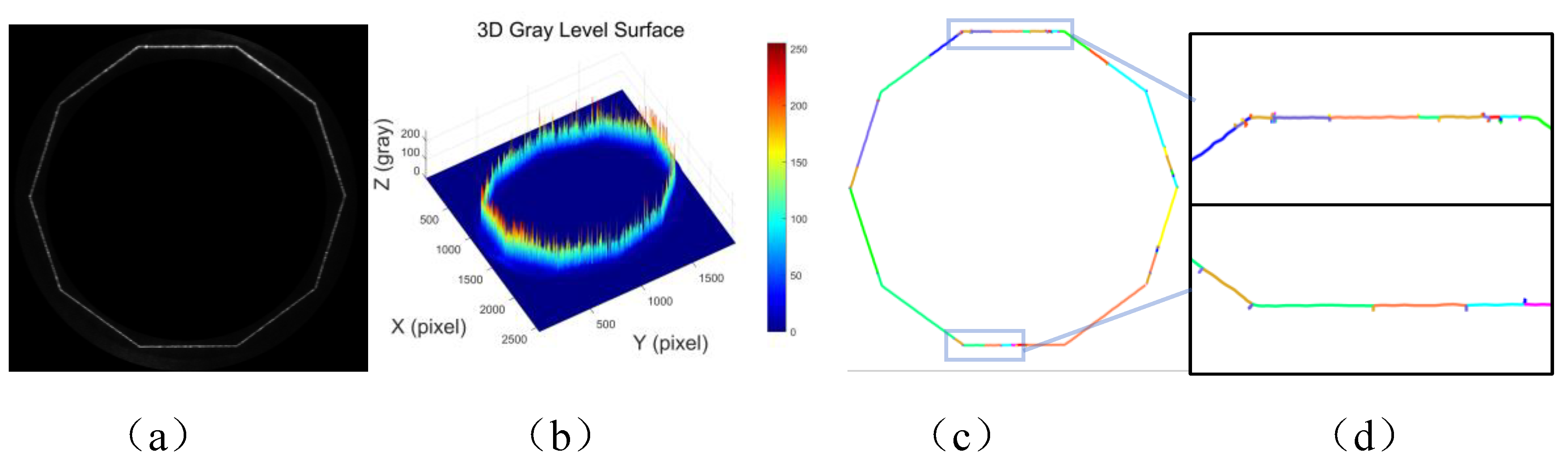

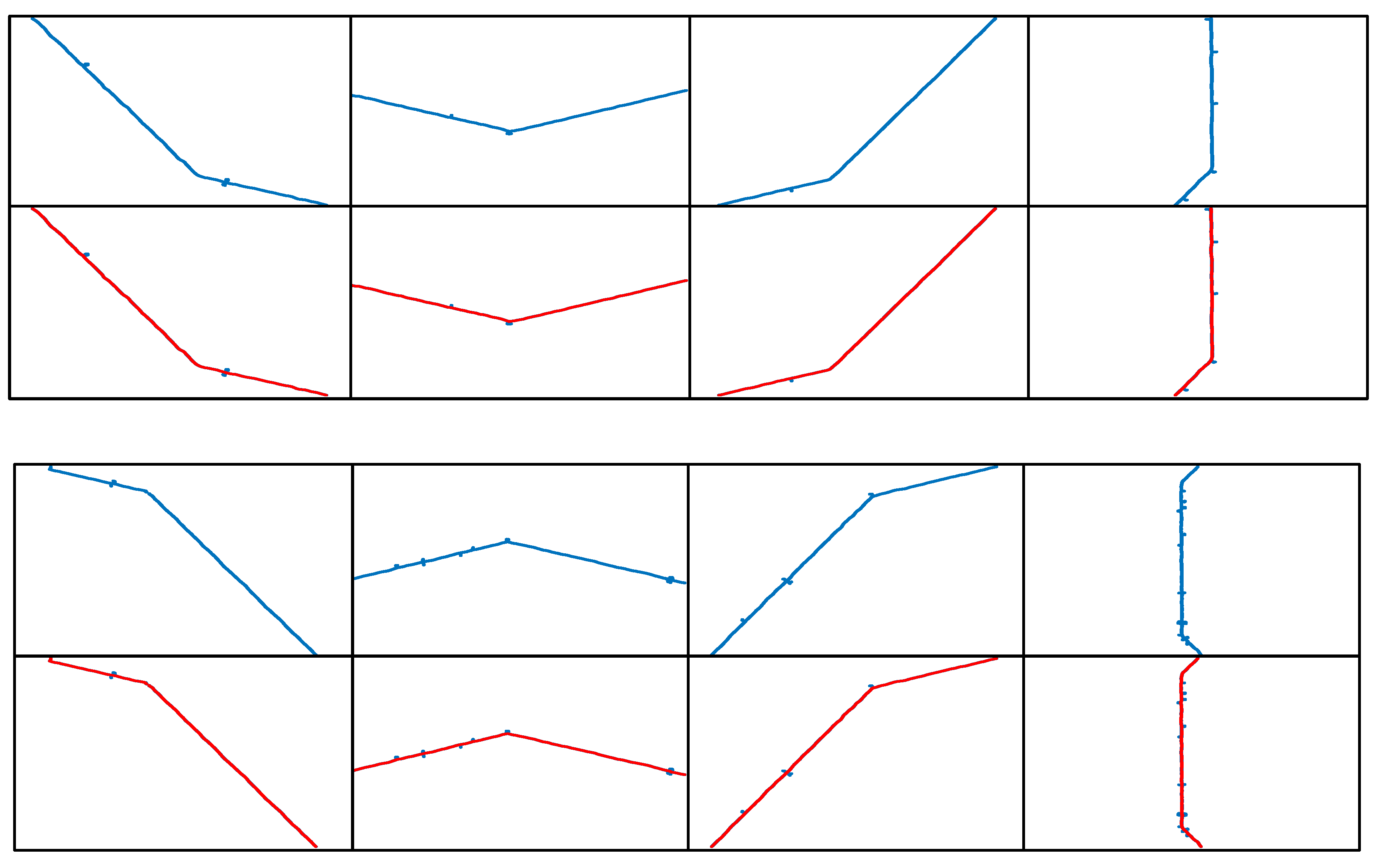

Figure 5 presents the feature analysis and geometric centerline extraction results of the internal octagonal laser stripe image.

Figure 5 (a) shows the grayscale image of the internal octagonal laser stripes, where the stripe distribution exhibits a regular octagonal pattern, with the stripe intensity more evenly distributed along the edges.

Figure 5 (b) presents the 3D grayscale distribution of the image. From this, it is clear that the grayscale intensity along one edge of the octagon is higher, while the intensity along the other edges remains relatively uniform, with a few points showing sudden intensity changes. This distribution characteristic is closely related to surface shape, roughness, machining tool marks, and reflective properties.

Figure 5 (c) displays the result of the geometric centerline extraction of the internal octagonal laser stripes based on the Steger algorithm, with different colors used to distinguish each line segment. The overall extraction result is relatively clear.

Figure 5 (d) provides a local zoom-in of the extracted result, where the details of the local line segments can be clearly observed. However, at the junctions of these segments, multiple line segments are identified, with numerous noise points and chaotic branches appearing.

In summary, for images with simple shape contours and uniform energy intensity distribution, the mature Steger algorithm can accurately extract the centerline of the laser stripes. However, when dealing with complex laser stripe images, the limitations of this algorithm become apparent. These parts, due to their complex inner surface shapes, varying roughness, random machining tool marks, diverse reflective properties, and the combined effects of laser and sensor system errors, result in low-frequency random noise signals in the subpixel contour point cloud data extracted by the Steger algorithm. This error is difficult to fully eliminate. The main issues with the Steger algorithm in complex laser stripe centerline extraction are as follows:

Shape Complexity: Complex contours, such as petals, internal gears, rectangular splines, etc., include multiple concave and convex structures, and the internal structural differences may lead to uneven illumination, thereby reducing image contrast and significantly affecting the extraction results.

Noise Interference: Reflections from the metal surface or machining marks are easily misidentified as edges, increasing the difficulty and complexity of stripe recognition.

Curvature Variation: At the junctions of straight lines with straight lines, straight lines with arcs, or arcs with arcs, large curvature variations are common, which can cause discontinuities in the extraction results or generate spurious edges.

Parameter Adjustment Limitations: Although the Steger operator can improve extraction results through parameter adjustments, for complex shapes such as petals, internal gears, rectangular splines, and internal octagons, relying solely on parameter adjustments cannot achieve ideal detection outcomes.

These limitations significantly affect the direct application of the Steger algorithm in complex laser stripe centerline extraction. However, from an overall extraction perspective, the Steger algorithm still retains the contour’s detailed information relatively well. Currently, complete contours are obtained by manually removing noisy points from point cloud data containing noise, which is a time-consuming and human-influenced process. Therefore, this study proposes an efficient method to automatically extract a complete contour curve from point cloud data containing noise points, providing an effective solution for the precise extraction of complex contours.