1. Introduction

Humans interact with many different objects throughout their daily activities. Some examples include carrying a briefcase to work, pushing a cart while shopping for groceries, working in the garden with a wheelbarrow, and lifting and moving boxes. Likewise, humans who have trouble walking use assistive devices to help them walk to places they need to go. The way humans interact with these different objects varies in many ways. Objects can be interacted with using only one hand or some need to be interacted with both hands due to the size and shape of the object. The area where humans place their hands to interact with the object is also different given the shape and size of the different objects. Humans approach and interact with these objects differently, and the biomechanics to move these objects also varies. This paper presents a library of data characterizing humans interacting with several objects from daily living, which will be used to develop a better understanding of human motion, object motion, and haptic interaction between the human and object in future work.

2. Motivation

Libraries of data characterizing human manipulation and interaction help scientists and engineers characterize how humans interact with those objects. Such data provides a foundation for ergonomists, biomechanicians, roboticists, and virtual reality and gaming engineers seeking to characterize human biomechanics and develop new devices and technology to simulate those interactions. Understanding the forces, torques, and dynamics produced on objects when a human interacts with them is crucial [

1]. The motion of a human walking up to the object and interacting with the object, i.e. grabbing, lifting, pushing, etc., is also important to characterize the typical ways humans interact with these objects. This research produces a library of data representing user biomechanics while interacting with those objects. The library will be used in future work to evaluate interaction with the objects and to design haptic manipulators that will mimic the objects in virtual reality. The haptic devices and virtual objects will then be used in user studies comparing virtual and real objects using the data from this library.

Our motivation for creating the library is somewhat unique. Many libraries, such as the KIT database [

2], are used to create a database representing human-object interactions with multiple objects, but they usually focus on motion alone and often strive to mimic that motion in related applications. Motion capture data from the KIT library, for example, is used to control robotic humanoids in simulation [

3] using a reference kinematics and dynamics model of the human body called the master motor map (MMM). The KIT database is also used to segment bimanual manipulation from household tasks based upon human demonstration [

4], which was also used to control humanoid robots. Other researchers have also used the KIT data base to create motions for humanoid robots [

5] based upon motions of the humans.

While these research endeavors characterize human kinematics while interacting with an object, we also aim to characterize haptic interactions with objects. While the KIT database has been applied to create a taxonomy differentiating coordination patterns in human bimanual manipulation [

6], our motivation is to eventually characterize human interactions with objects from both a biomechanics

and haptics perspective, which will be used as a baseline for evaluating the haptic manipulators that we are developing While the data from our library might be used to create a taxonomy like [

6], it is not a specific motivation for our research.

To characterize human kinematics and haptic interaction, our library is a combination of motion capture data, load cell data of the interaction between the human and different objects, and IMU (Inertial Measurement Unit) readings of the object when it is being manipulated.

3. Related Work

3.1. Haptics

Haptics is the study of touch and motion. For us specifically, we are researching how subjects touch and move different objects from everyday life. The field of haptics has been an ongoing research topic [

7,

8]. There are 4 main subareas of haptics: human haptics, machine haptics, computer haptics, and multimedia haptics [

9]. Human haptics is more focused on physiological response, such skin stretching in response to forces, which is not related to this work. Machine haptics is more focused on design and control of a device to mimic haptic interactions, which is more a focus of our future work designing and evaluating haptic manipulators based upon the library in this paper. For this research we are focused on the forces, torques and manipulation of objects by humans and the way humans orient themselves to interact with these objects. Motion capture, load cells on the objects, and an IMU on the object track the human subject and provide haptic measurements when the subjects interact with the objects. Computer graphics haptics is more focused on visual display of objects moving due to haptic interact, which will be the focus of future work citing this library. Multimedia haptics is more focused on the ability of multimedia display to mimic haptic interaction, such as the work in [

10] where environmental displays such as wind and mist are used to create haptic sensations, which is quite different from this work.

Adding load cells to objects that humans are interacting with has been done before. Russo et al studied how humans balanced on a wooden beam while holding two canes with load cells in the base and motion capture to track the forces and human orientations to balance themselves on the beam [

11]. McClain et al conducted a similar experiment of a human using a walker for load support, but used strain gauges on the tubes supporting the handles to measure interaction forces [

12]. The data was used to design a new walker and its control systems to support similar forces. We are using a 6-DoF load cell to obtain interaction forces and will evaluate how a user interacts with haptic manipulators mimicking a walker. We believe that the work presented here is unique since the goal is to create a library of such biomechanical and haptic interactions with objects while standing and walking.

3.2. Similar Databases

There are many human motion databases openly that include a wide range of information. These databases are essential for many different fields such as computer vision, computer graphics, multimedia, robotics, human-computer interaction, and machine learning. Zhu et al [

15] provide an extensive survey of human motion databases, characterizing them by measurement techniques, types of motion and manipulation used to generate the data, and the types of data contained in the studies. Common data sources include marker-based motion capture, ground reaction force data, inertial measurements, video, and imagery. A wide variety of motions are studied, such as walking, lifting, kicking, dancing, and interaction with different objects. Some tasks require single-handed manipulation and others require two-handed manipulation. Objects range from small household items, such as bottles, caps, and utensils, to hand-held tools, to large items, such as furniture, boxes, and doors.

Of the many databases described in [

15], the work presented here is most similar to those focusing on manipulation of medium to large objects from daily living combined with locomotion, specifically where one and two-handed manipulation is required. Human motion and kinematics, object motion, and kinetic interactions with the object are characterized. A brief review of the most related data sets is provided below and summarized in

Table 1, which highlights the different types of data presented, the types of motion used to collect data, and the objects that are manipulated.

In [

16], Bassani et al provide a dataset characterizing human motion and muscular activity in manual material handling tasks, which is typical in the biomechanics and ergonomics communities. Users lifted and moved a small barbell weight with one-arm and a medium sized box using bimanual manipulation, amongst other tasks. Data is collected using an Xsens MVN suit composed of (17) 9-axis IMU sensors and 8 sEMG sensor readings and contains data from 14 subjects. Subjects stood in the N-pose in front of a table, lifted the object from the floor, kept it lifted with the elbow flexed at 90 deg, and placed it on a table. Subjects would then lift the object from the table, carry it to another position, and place it on the floor. Their box manipulation task is like the box manipulation task in our library, but our study instruments the box to measure interaction wrenches and uses motion capture to measure kinematics, which is unique since our database provides a baseline for characterizing haptic interaction.

Geissinger et al [

17] use an XSens MVN with sparse IMUs to measure human kinematics during activities of daily life on a university campus, driving, going to a variety of different stores, working in a machine shop and laboratory, exercising, and at home. This generated a large data set across 13 subjects, which was then used to train deep learning networks to predict upper body motion and full body motion. While some of the activities, such as walking up to a door and opening it, pushing a cart, or lifting a box, are like those in our study, they only focus on the kinematics of the human whereas the database presented here also characterizes kinetic interaction with the object and its resulting motion.

Table 1.

Comparison of our dataset library and existing ones.

Table 1.

Comparison of our dataset library and existing ones.

| Database |

Human

Sensing |

Haptic

Sensing |

Object

Sensing |

Object

Size

(S, M, L) |

Similar

Objects |

Locomotion

with Objects |

Number of

Subjects |

Dataset of Human Motion and

Muscular

Activities [16] |

IMU, sEMG |

None |

None |

M |

B |

Yes |

14 |

Dataset of

Unscripted

Human Motion [17] |

IMU |

None |

None |

S, M, L |

B, D, SC |

Yes |

13 |

|

HBOD [18] |

MoCap, IMU |

None |

MoCap |

S, M |

None |

No |

5 |

An Industry-

Oriented Dataset [19] |

IMU, MoCap |

Pressure Sensor |

None |

S, M, L |

None |

Yes |

13 |

|

BEHAVE [20] |

RGBD Images |

None |

RGBD Images |

S, M, L |

B, L |

No |

8 |

|

KIT [2] |

MoCap |

None |

MoCap |

S, M, L |

B |

Yes |

43 |

| Our Database |

MoCap |

Load Cell |

MocCap, IMU |

M, L |

B, D, BC, L, W, WB, SC |

Yes |

6 |

The hand-body-object dataset (HBOD) includes data of subjects moving and interacting with a screwdriver, hammer, spanner, electrical drill, and rectangular workpiece with one hand [

18]. Data is derived from 12 IMUs placed on body segments and a Cyberglove 2, which together measure body and hand kinematics. In this case, motion capture markers were used to measure the posture of the objects being manipulated. Five subjects then lifted and placed objects at high positions and performed tool manipulation. While the measurement of human and object kinematics are in the same spirit our database, [

18] focuses more on dexterous kinematics, and kinetics are not measured. Likewise, the objects being manipulated are quite different than those presented in this paper.

The Industry-Oriented Dataset for Collaborative Robotics includes data of human postures and actions that are common in industry [

19]. Like HBOD, [

19] measures both whole body kinematics using IMUs and a glove with flexion sensors to measure hand kinematics. Similar to our work, they also use marker-based motion capture to measure human kinematics. Their gloves use pressure sensors to detect contact with the objects, but this does not provide kinetic information about interaction forces as we do in this paper. The study emphasizes tasks typical of assembly lines, which are mainly focused on picking up small parts, carrying them, and then assembling them with other objects. They do, however, evaluate lifting larger loads and moving them to a shelf, which is like the box-lift task in our study. Unlike HBOD and this paper, the object motions in [

19] are not measured. Measurements from 13 subjects are reported in [

19]. Two cameras are used for video recording tasks, but data is not derived from them.

The BEHAVE dataset [

20] includes a large set of images of 8 subjects interacting with objects in natural environments. This dataset contains Multiview-RGBD frames with accurate pseudo ground-truth SMPL (Skinned Multi-Person Linear Model). Objects that are manipulated include various boxes, chairs, and tables, as well as a crate, backpack, trashcan, monitor, keyboard, suitcase, basketball, exercise ball, yoga mat, stool, and toolbox. Interactions include lifting, carrying, sitting, pushing, and pulling, as well as unstructured free movement combined with object interactions. One and two-handed manipulations are provided with hands, as well as manipulations using feet. Imagery data does not measure kinematics and kinetic interaction directly, but the authors do provide computer vision code to demonstrate basic reconstruction of kinematics using the data. It is not clear if such information is sufficient for characterizing haptic interaction.

The KIT database includes a dataset of full-body human and object motion capture using one and two hand manipulation [

2]. This database has 43 different subjects and 41 different objects with raw data and post-processed motions. This dataset includes a full body motion capture marker setup with 56 markers and markers placed on each of the objects to analyze object movement. The objects and interactions include tasks such as opening a door, manipulating a box, walking up and down stairs, and interaction between subjects. This is a very extensive database and includes a plethora of other objects, but it is mainly focused on kinematics. Kinetic interaction is not measured.

While these studies have provided detailed insight into how people interact with specific objects, our end goal focuses on haptic interaction with a series of everyday objects combined with locomotion. The database described in this paper includes full body motion capture and object motion capture data, which is only present in a few studies, such as [

2]. Unique to our database is object instrumentation using IMU measurements of the object motion when a human is moving the object and measurements of interaction wrenches using 6-DOF load cells. This allows detailed measurement of forces and torques exerted on the object combined with the object’s accelerations and position, which should be sufficient to characterize haptic interaction with the object. This new information can be used to characterize the different object models for future applications, such as haptics and virtual reality (VR). Further unique to this study is that this haptic interaction is combined with measuring human motion during that interaction, which allows simultaneous characterization of human gait and kinematics during haptic interaction. This knowledge will be helpful for validating interactions with future haptic devices mimicking these objects in a virtual world.

4. Tasks

Several activities of daily life have been identified as motivating tasks for this research based on coordination of locomotion and manipulation. The first task uses two-handed oppositional grasp and is shown in

Figure 1 (a) where a user is grasping and lifting a box on a virtual table. The next task uses a piece of luggage, also known as a roller-board, where the user supports the luggage by the handle and pulls it behind them as they walk,

Figure 1 (b). This task is proposed as an example of a person walking through an airport. A task using a briefcase,

Figure 1 (c), is shown in the user’s right hand, which is carried like a person walking to work. A walker usage task is presented,

Figure 1 (d), which is motivated by our prior work with subjects with Parkinson’s Disease [

21] and Spinal Cord Injury [

22] where the walker is used to help support the user while they walk. Walker usage usually requires the user to lift the handles slightly and push it to locomote. The shopping cart task shown in

Figure 1 (e) requires the user to push the cart using different levels of force in each hand to control the cart direction.

Figure 1 (f) illustrates a task where the user operates a wheelbarrow, which is common for yard work around the home. This requires the user to lift the back of the wheelbarrow with the handles and then push it forward while walking. They may tip is slightly side to side to control steering. Depending on the load in the wheelbarrow (e.g. dirt or concrete versus wood chips or leaves), this can be incredibly demanding, requiring both strength, coordination, and balance. Hence, we will use wheelbarrow operation to display more physically challenging tasks to the user. The door opening task is proposed as shown in

Figure 1 (g), which was selected since this is consistently in everyday life. The door is configured to open inward and pivot on its right side such that the user pushes the door open with their right hand and steps through.

Figure 1.

Tasks done in everyday life: (a) manipulating a box, (b) walking with luggage, (c) carrying a briefcase, (d) using a walker, (e) pushing a cart, manipulating a wheelbarrow, and (f) opening a door.

Figure 1.

Tasks done in everyday life: (a) manipulating a box, (b) walking with luggage, (c) carrying a briefcase, (d) using a walker, (e) pushing a cart, manipulating a wheelbarrow, and (f) opening a door.

5. Methods and Procedures

This paper presents methods and procedures used to create a database describing how humans interact with the objects presented in

Section 4. The human walks up to these objects, grabs the handles, lifts/lowers, pushes, or walks with a steady gait while grasping/manipulating the object. During the study, information such as forces, torques, object motion, human kinematics, and human gait are collected. The use of 6-DOF load cells incorporated into the object’s interaction areas, such as handles, record forces and torques applied to the object by the human. Body and object kinematics and dynamics are studied using full body motion capture and IMU readings of the object motion when a human interacts with the object.

5.1. Motion Capture Volume

The motion capture system consists of a 10 camera VICON motion capture system with a mixture of MXF20 and MXF40 cameras. The capture volume is designed to capture full body motion in an 8.2 by 4.5 by 2-meter sized space. This ensures that we are capturing full body data for a subject who is 1.9-meters tall locomoting for multiple gait cycles and interacting with the objects naturally. The room is sufficiently large that users can begin walking and establish a gait pattern.

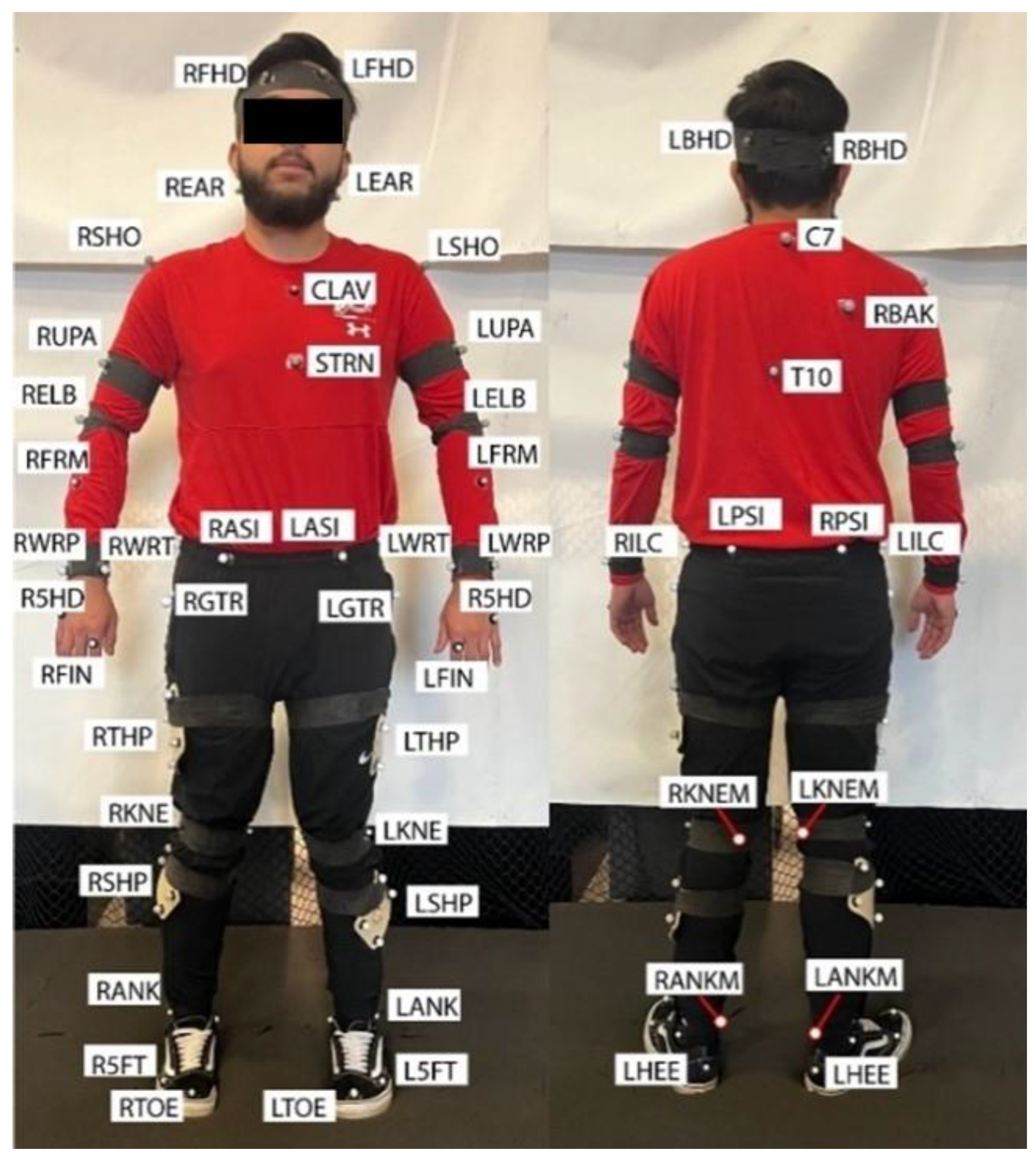

5.2. Marker Set

The full body marker setup is shown in

Figure 2. Reflective markers are placed on all main segments and on rotational joints [

23,

24]. A minimum of three markers are placed on each of the segments to fully define the segment and record its movement. The motion capture setup is found to be sufficient enough to get full body motions for all sizes of participants in the study. This data is exported in CSV and C3D files to be viewed in the database.

Figure 2.

Motion Capture Marker Setup [

23,

24].

Figure 2.

Motion Capture Marker Setup [

23,

24].

5.3. Instrumentation and Syncronization

Each object is instrumented with force/torque sensors, an IMU, and motion capture markers. The force/torque sensors are 6-DOF sensors from ATI Industrial Automation (9105-TIF-OMEGA85). The IMU is a Parker Lord Microstrain IMU (3DMGX5-AR) and can capture a wide variety of different readings. We are mainly interested in the acceleration of the object when it is manipulated by the user. One of the Load Cells and the IMU are encased inside the IMU/Load Cell casing to keep the IMU safe and to have the respective coordinate frames stay consistent between the Load Cell and the IMU (Figure 3). The Load Cell/IMU casing has a marker extension with VICON markers on it designed to produce an unobstructed coordinate frame when connected to the different objects. The second load cell is in a similar case but it does not have an IMU inside of it.

Figure 3.

The Load Cell and IMU holder.

Figure 3.

The Load Cell and IMU holder.

Each sensor is logged on a separate computer which requires a method of data synchronization. The dSpace system sends a chain of impulses to the VICON DAQ to line up the data between the load cell and the motion capture data. To synchronize all of this data the object is given 10 short impulses by the subject, resulting in accelerations in the IMU, and force measurement in the force/torque sensor. Displacements in the motion capture data, which are synchronized in time, can be used to check the synchronization between all the different data sets. The synchronization between the different sensors/ computers is essential to keeping the data consistent.

5.4. Object Instrumentation

5.4.1. Box

The box used in this study is heavier and large, so it is more challenging than other tasks. The box object is constructed to model a 50.5 45.7 45.7-centimeter cardboard box with moderate rigidity. The box weighs 8 kilograms and has an added 1.4-kilogram weight placed inside. Figure 4 shows the box object, which is comprised of three parts, the main body of the box and then two separate sides. The main body is constructed of thin, aluminum plates with small brackets for added rigidity. The sides are made of large aluminum brackets with cardboard mounted externally, allowing the user to feel the texture of cardboard during manipulation. The two force/torque sensors are mounted between the main body and each of the sides. The IMU is encased inside the IMU/Load cell casing and is between the main body and the left side, Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The Box Apparatus.

Figure 4.

The Box Apparatus.

5.4.2. Luggage

The luggage object is 48.3 by 33 by 17.8-centimeter roller luggage compartment with an instrumented handle as shown in Figure 5. There is a 4.5-kilogram weight added inside the luggage compartment to simulate a packed piece of luggage. The luggage itself weighs about 2.3-kilograms. The sensor housing containing the load cell and IMU are between the luggage compartment and the handle. It is positioned here to measure the forces exerted by the human when holding the handle and walking with the object. Motion capture markers surround the compartment and are on either side of the handle. There are also markers placed on the sensor housing to know the location of the Load Cell and IMU.

Figure 5.

The Luggage/Roller Board Apparatus.

Figure 5.

The Luggage/Roller Board Apparatus.

5.4.3. Briefcase

The briefcase is a 48.3 by 12.7 by 45.7-centimeter briefcase with an articulating handle, Figure 6. The briefcase has added weight inside of it to simulate a full briefcase weighting 8-kilograms. The briefcase handle has been instrumented by detaching it from the briefcase and putting it on a fixture consisting of aluminum and 3D printed parts. This fixture is connected to the load cell, which is connected to the sensor housing also containing the IMU. The handle is able to rotate exactly the same as the original briefcase design. An aluminum plate is bolted to the side of the hard case of the briefcase to be able to mount the handle and the sensor housing. The handle is in the relative location as when it was connected to the briefcase but elevated slightly to accommodate the sensor housing. Motion capture markers are placed around the briefcase and on the sensor housing.

Figure 6.

The Briefcase Apparatus.

Figure 6.

The Briefcase Apparatus.

5.4.4. Walker

The walker object is a modified assistive walker with the handle height being 94-centimeters high and the handles being 61-centimeters apart with a weight of about 7.5-kilograms, shown in Figure 7. The Load Cells/IMU casings are located between the handles and the adjustable height bars. The height is adjustable but set to a position that an average person can comfortably use. Motion capture markers are placed around the lower frame of the walker and the Load Cell/ IMU casings.

Figure 7.

The Walker Apparatus.

Figure 7.

The Walker Apparatus.

5.4.5. Shopping Cart

The shopping cart is a standard shopping cart typical of a US grocery store, shown in Figure 8. The shopping cart is 91.5 by 61 by 112-centimeters with the handles located 112-centimeters above the ground. The shopping cart weight19.5-kilograms and there is also a 22.7-kilogram plate fixed inside the shopping cart to simulate the cart carrying groceries. The cart is painted matte black so it does not affect the motion capture cameras when capturing datasets. The load cells and IMU are located between the handles, which are split, and the shopping cart body. The frame of the handles is cut so they sit at the same location as a normal shopping cart. There are motion capture markers placed around the lower frame near the wheels and around the top of the cart basket.

Figure 8.

Shopping Cart Apparatus.

Figure 8.

Shopping Cart Apparatus.

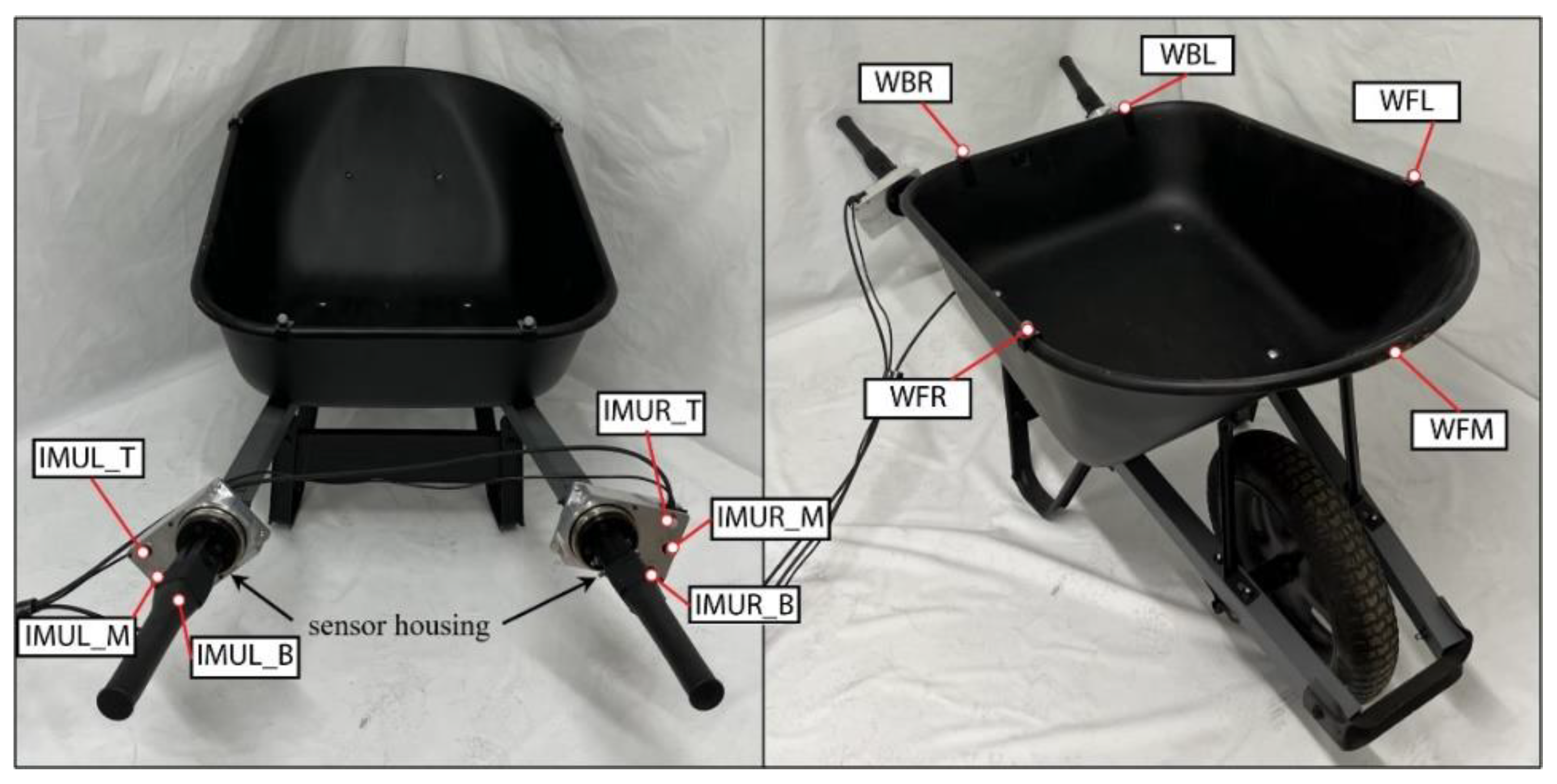

5.4.6. Wheelbarrow

The wheelbarrow is a standard steel wheelbarrow purchased from Home Depot, shown in Figure 9. The wheelbarrow is a 68.58 by 67.8 by 115-centimeter fixed wheelbarrow which weighs 16.3-kilograms. The wheelbarrow also has a 22.7-kilogram plate in it to simulate the wheelbarrow carrying a load such as dirt. The Load Cell and IMU cases are located between the chassis of the wheelbarrow and the handles. The end of the handles are in the same position as they were originally so as to not change the overall design. There are motion capture markers located around the bucket of the wheelbarrow and on the Load Cell/ IMU casings. The wheel barrow was painted matte black to prevent interference with the motion capture system.

Figure 9.

Wheelbarrow Apparatus.

Figure 9.

Wheelbarrow Apparatus.

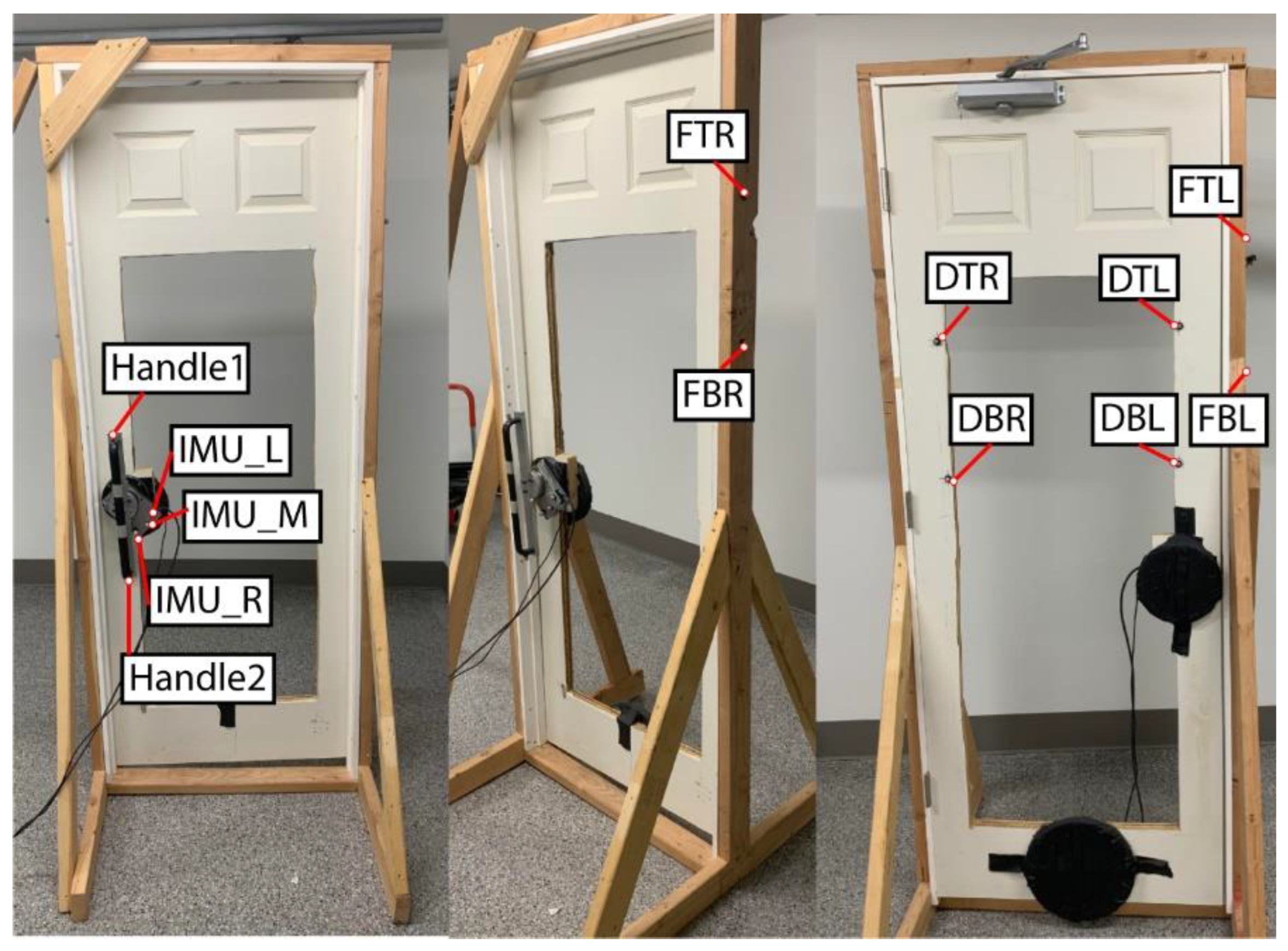

5.4.7. Door

The door is a standard solid core molded composite interior door purchased from Home Depot (Item No. THDQC225400566). The door is 76.2-centimeters wide by 203.2-centimeters high and weighed 25.4-kilograms. The door is cut out in the middle to allow the motion capture cameras to see through the door and view the motion capture markers on the front of the subject (Figure 10). Due to cutting out a large portion of the door, added weights were placed on the door to simulate a heavy door weighting 15.87-kilograms. The door has a door closer so there is added tension on the door and the door closes by itself. The door handle is a standard long door handle, which is affixed to the load cell and IMU case and then attached to the door where a standard door handle would be. The load cell and IMU case has the extension on it to put the motion capture markers in an area where they can be seen by the motion capture cameras. There are also motion capture markers placed on both sides of the door and around the frame of the door so the door angle can be found when opening it.

Figure 10.

The Door Apparatus.

Figure 10.

The Door Apparatus.

5.5. Object Interaction Protocols

The database includes a variety of human motion capture files, object motion capture files, and sensor files specific to interaction with the objects mentioned in Sec 3. Separate protocols for each object are used to provide similar interactions amongst the subjects. While all interactions involve walking and manipulation of the object, they are all slightly different due to the unique ways humans interact with each of them. We generally evaluate multiple interactions with each object such that lifting of an object is considered separately from walking with the object. This allows us to decouple the two types of interactions for evaluations in future studies. Likewise, tasks involving walking while manipulating the object initiate gate with the left foot, allowing a common gait pattern to be established in all the trials. All interactions were designed to mimic natural interactions with the objects, although interactions were segmented as indicated above.

1) Box: The box has two types of interactions. The first is lifting. The box is sitting on a stand. The subject starts standing straight up, then bends down and grabs the sides of the box with an oppositional two-handed grasp and then lifts the box. They will then lower the box back down to the stand, let go, and stand back up. In the second interaction the subject carries the box while walking. The subject starts at one end of the capture volume holding the box with a two-handed oppositional grasp and then walks through the volume. They start with their left foot and walk to the other side of the volume with a steady gait while holding the box.

2) Luggage: The subject starts at one end of the capture value holding the handle of the luggage. They then walk through the capture volume pulling the roller luggage behind them. They begin walking with their left foot first while keeping a steady gait until they reach the other side of the capture volume.

3) Briefcase: The briefcase has two different types of interactions. The first is lifting. At the start, the subject is standing straight up, then bends down and grabs the handle, and then lifts the briefcase. They then lower the briefcase to the ground, let go, and stand back up. In the second interaction the subject caries the briefcase while walking. They start at one end of the capture volume while holding the briefcase in their right hand. They then walk, starting with their left foot, through the volume to the other side with a steady gait while holding the briefcase.

4) Walker: In this interaction, the subject walks through the motion capture volume using the walker for support. They start at one end of the volume with their hands grasping the walker handles. The subject then lifts the handles slightly and pushes the roller walker forward while extending their arms. They set the handles down and then apply downward force on the handles to support their weight while stepping towards the walker. The process repeats until the subject traverses the capture volume.

5) Shopping cart: The subject approaches the shopping cart and then pushes it through the motion capture volume. The subject starts in a standing position a step back from the shopping cart. They step towards the cart and place their hands on its handles; both of their arms come up and grasp the shopping cart. They then push the shopping cart through the volume while walking.

6) Wheelbarrow: The wheelbarrow has two types of interactions. The first is lifting the handles. The subject starts in a standing position between the handles. They then bend down, grab the handles, and lift the wheelbarrow handles. The handles are then lowered until the back of the wheelbarrow again contacts the ground. The subject then releases the handles and stands back up. In the second task the subject pushes the wheelbarrow through the volume while walking. The subject starts at one end of the capture volume while holding the wheelbarrow handles; meaning that the back of the wheelbarrow is lifted and the front is balanced on its wheel. They then walk through the volume while pushing the wheelbarrow. They start walking with their left foot, develop a steady gait, and push the wheelbarrow through the capture volume.

7) Door: The subject walks up to the door, opens it, steps through, and releases the door handle. They begin standing a few steps away from the door. Unlike the other walking trials, the subject first takes a step with their right foot due to the location of the door so they can more naturally open the door and step through it. After the right step, they step with their left foot towards the door while also reaching with their right hand to grasp the door handle. They then push the door open with their right hand and walk through with the left foot leading. This is due to the fact that it is a right-handed door, meaning that the hinge is on the right side of the door and the handle and opening are on the left side. They then finish stepping through the door with their right foot and release the handle, allowing it to start closing. They then take a half step with their left foot such that it evens up with the right foot. The subject is then standing straight up and the door has closed behind them.

8) Gait: Natural gait is also measured since so many of the tasks involve walking with objects. This will allow a baseline comparison in future studies so that the effect of handling the objects can be considered. The subject stands at one end of the capture volume and starts walking with their left foot. They walk across the capture volume and their gate is recorded.

6. Data Processing

6.1. Vicon

Processing starts with the data collected via our Vicon motion capture system. Marker registration is verified first to ensure that all markers are continuously registered through the motion sequence since markers may be lost occasionally. Vicon Nexus data gap-filling (i.e., Spline, Cyclic, and Pattern filling) was applied to resolve unregistered markers. For small gaps, a mixture of Cyclic and Spline gap-filling was applied. Cyclic filling uses information from the whole trial. Since we were repeating gaits, Cyclic was a great option due to the repetitive nature of the study. Spline filling uses cubic spline interpolation of the points around the marker gap. Pattern filling was used for large gaps where Cyclic and Spline filling failed. Pattern filling references other markers that experience the same trajectory characteristics (rigid bodies), on the same segment.

After marker filling, Vicon data is then exported. Exporting is the same for all studies, no matter the object or trial. For each full trial, trajectory data is exported in CSV data files and C3D motion files while trigger data is exported in CSV files. Trigger data is generated by the dSpace system indicated later in this section. Trajectory data includes motion capture data from both the subject and object.

Full trial data is also segmented in Nexus to create short segments for repeated tasks. For example, a subject may lift an object multiple times in a full trial or may push an object multiple times in a full trial. The segmented trajectory data is trimmed to windows where only the whole human and object marker sets are visible. Segmented trajectory data is provided in CSV data file and C3D motion file formats in the database.

6.2. AddBiomechanics

AddBiomechanics is an open-source motion capture pipeline developed at Stanford University that uses optimization to process uploaded motion capture data faster and more efficiently [

25]. The C3D files from the previous subsection are uploaded to AddBiomechanics along with subject demographic, height, and weight information. C3D data is combined with a musculoskeletal model of the subject. The OpenSim musculoskeletal model by Rajagopal et al [

26] is adapted to use our marker set. The single markers used by Rajagopal at the thigh and shank were replaced by the marker rigid marker plates that we use at these locations. The four markers used by Rajagopal at the shoulder were replaced by our single marker. Our marker set also includes an additional marker on the hand and 3 extra markers on the trunk, which were added to the model. The modified musculoskeletal model is provided in the database and is stored in AddBiomechanics with the data.

AddBiomechanics is then used to process the data. AddBiomechanics first estimates the functional joint centers and then creates an initial guess for body segment scales and marker registrations [

25]. Bilevel optimization is applied to fit the model geometry and kinematics to the marker data. AddBiomechanics is then used to produce exportable files that include joint and segment rotational angles. The files produced byAddBiomechanics are marker error (CSV), the joint and segment angles (MOT), and PDF previews of the data. All of this data is available in AddBiomechanics and in our database.

6.3. dSpace/Load Cells

The dSpace file is presented as a MAT filetype and contains the information from both of the load cells (force, and torque). This file includes time syncing data (i.e., trigger data) and force and torque measurements. Both raw and filtered data is included. Filtered data is also included by using a low pass filter with a 20 Hz cutoff frequency.

6.4. IMU

The IMU data is presented as a CSV file and includes data reported by the IMU located on the object. Data is transmitted by serial communications to the dSpace computer using the SensorConnect software. The information in this file include the acceleration readings of the object when it is interacted with and the gyroscopic readings when the object is manipulated.

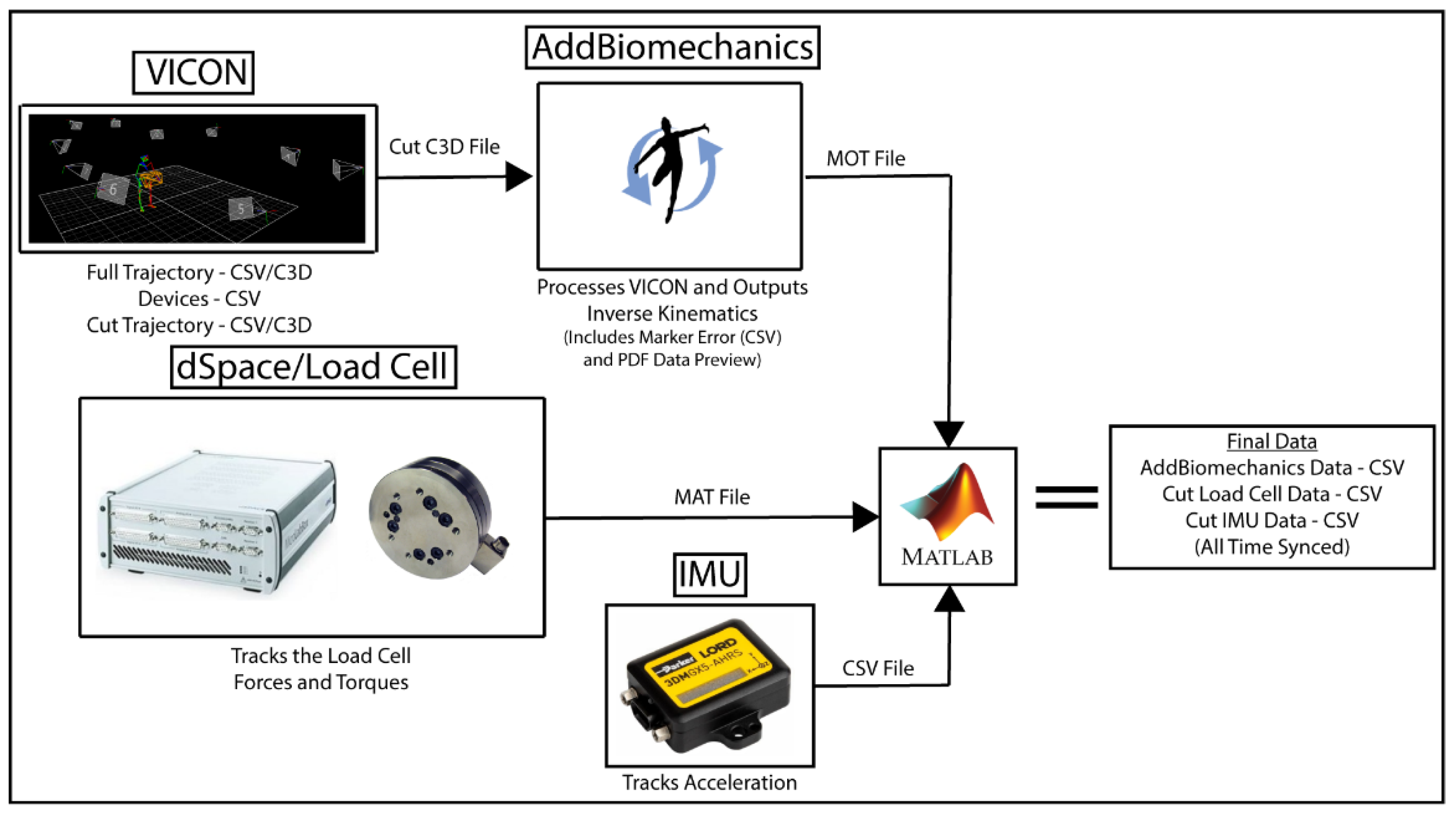

6.5. Final Data Synchronization and Export

Once the data processing described in the previous subsections is complete, final synchronization and file generation is performed Figure 11. Data is synchronized and exported for each subject, object, and interaction separately. A MATLAB script first loads the data:

VICON trajectory CSV,

VICON trigger data CSV,

Cut VICON trajectory CSV,

AddBiomechanics MOT motion file,

Load Cell MAT file, and

IMU CSV file.

Figure 11.

Data Processing Flowchart.

Figure 11.

Data Processing Flowchart.

This MATLAB script then synchronizes the different datasets. The VICON trigger data CSV contains analog measurements of the trigger signal which is produced by dSpace when the measurements are started. The same trigger signal is recorded in the Load Cell MAT file and is used to align the timestamps of the two data sets. The Load Cell MAT file and IMU CSV file timestamps are then synchronized by detecting the 10 taps indicated in

Section 5.3. The Cut VICON Trajectory CSV timestamps are the same as those in the Vicon Trajectory CSV, so the timestamps in the Cut Vicon data are then used segment the Load Cell and IMU data correspondingly for each trial. This allows the cut data to represent both the kinematics and kinetics for each trial separately. AddBiomechanics shifts the start time for each trial to zero to represent the start of each trial uniformly. The segmented Load Cell data and IMU data for each trial are likewise shifted to zero to correlate to the AddBiomechanics data. MATLAB exports the synchronized Final Data (AddBiomechanics, Load Cell, and IMU) in CSV format.

7. Results

7.1. Subjects

The dataset currently contains data from 6 subjects, which will be expanded as this project continues. The subjects are all healthy males ranging from 18 to 30 years old. They range from 1.6 to 1.9-meters in height and 56.6 to 133-kilograms in weight. Data was collected according to University of Utah IRB #00123921.

7.2. Datasets

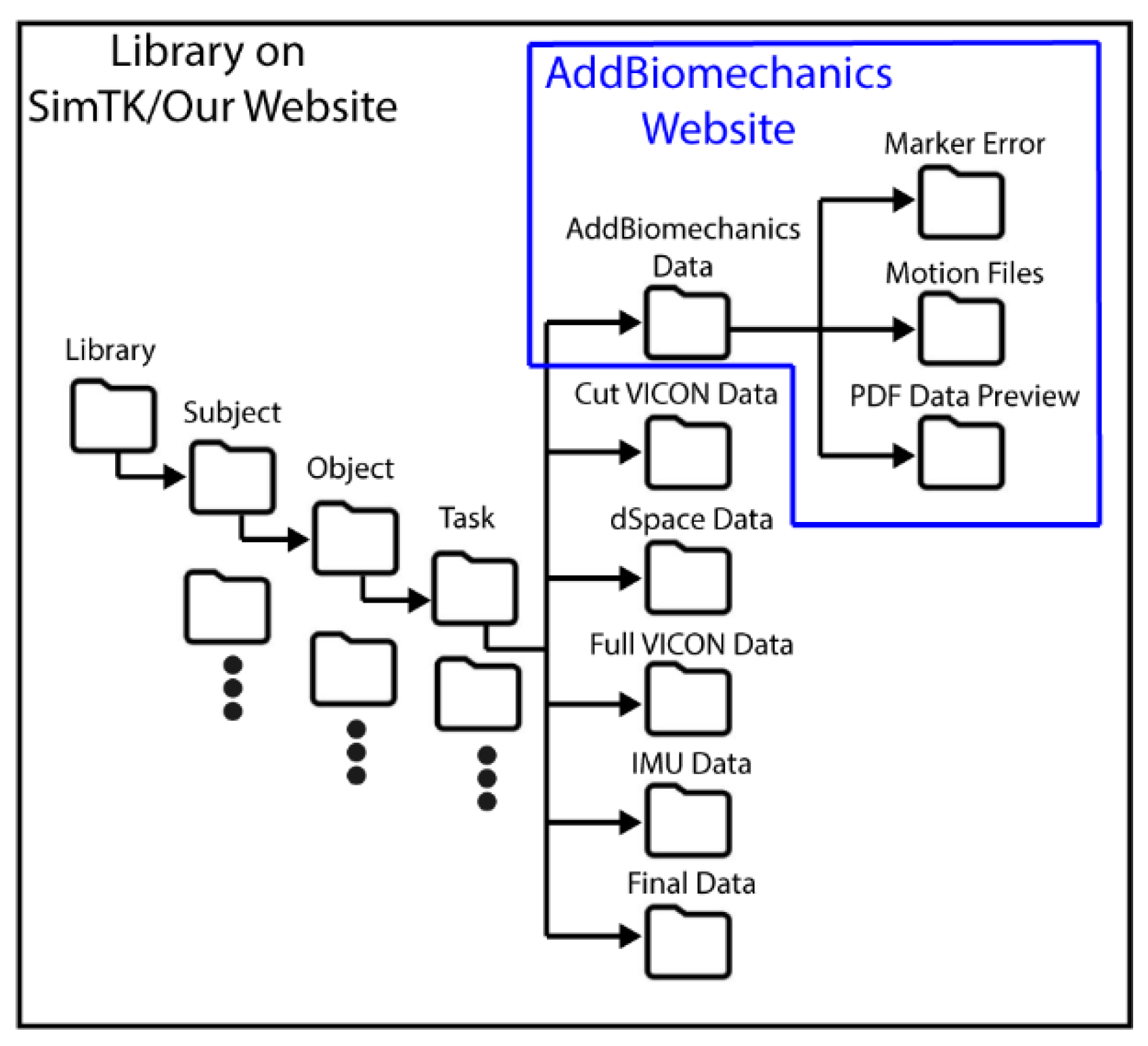

Our dataset includes a few different data sets from the different stages of processing, Figure 12.

- 1)

The main dataset is located on our website and contains all the files described in

Section 6 and shown in

Figure 12. Data is arranged by subject, object, and task. The AddBiomechanics folder contains the data generated from the AddBiomechanics which is the Marker Error (CSV), Motion Files (MOT), and PDFs that show a preview of the data in the motion files. The Cut VICON Data folder contains the windowed marker data from VICON (CSV/C3D). The dSpace Data contains a MAT file of each load cell and additional data needed for time syncing. The Full VICON Data folder contains the whole marker trajectory file for each task (CSV/C3D) and the trigger data file for syncing (CSV). The IMU Data folder contains the IMU sensor data (CSV). The Final Data folder contains the synced AddBiomechanics full body joint and segment angles (CSV), the force and torque from the load cells (CSV), and the IMU data (CSV) of the windows of the VICON data. The entire library of data is available on our website and SimTK.

Figure 12.

Database File Organization.

Figure 12.

Database File Organization.

- 2)

The AddBiomechanics data is also available on the AddBiomechanics website and contains everything that is in the main dataset. It also contains the uploaded files used to generate the AddBiomechanics data. It contains the PDF, the marker errors and the motion files described above. It contains the marker data in a (TRC) file, and the OpenSim models used to get this information. AddBiomechanics is provided so that other researchers can evaluate the data processing and have ready access to raw and processed data.

- 3)

The main dataset is also available on SimTK and contains everything that is in the main database file described above. SimTK is commonly used amongst the biomechanics community.

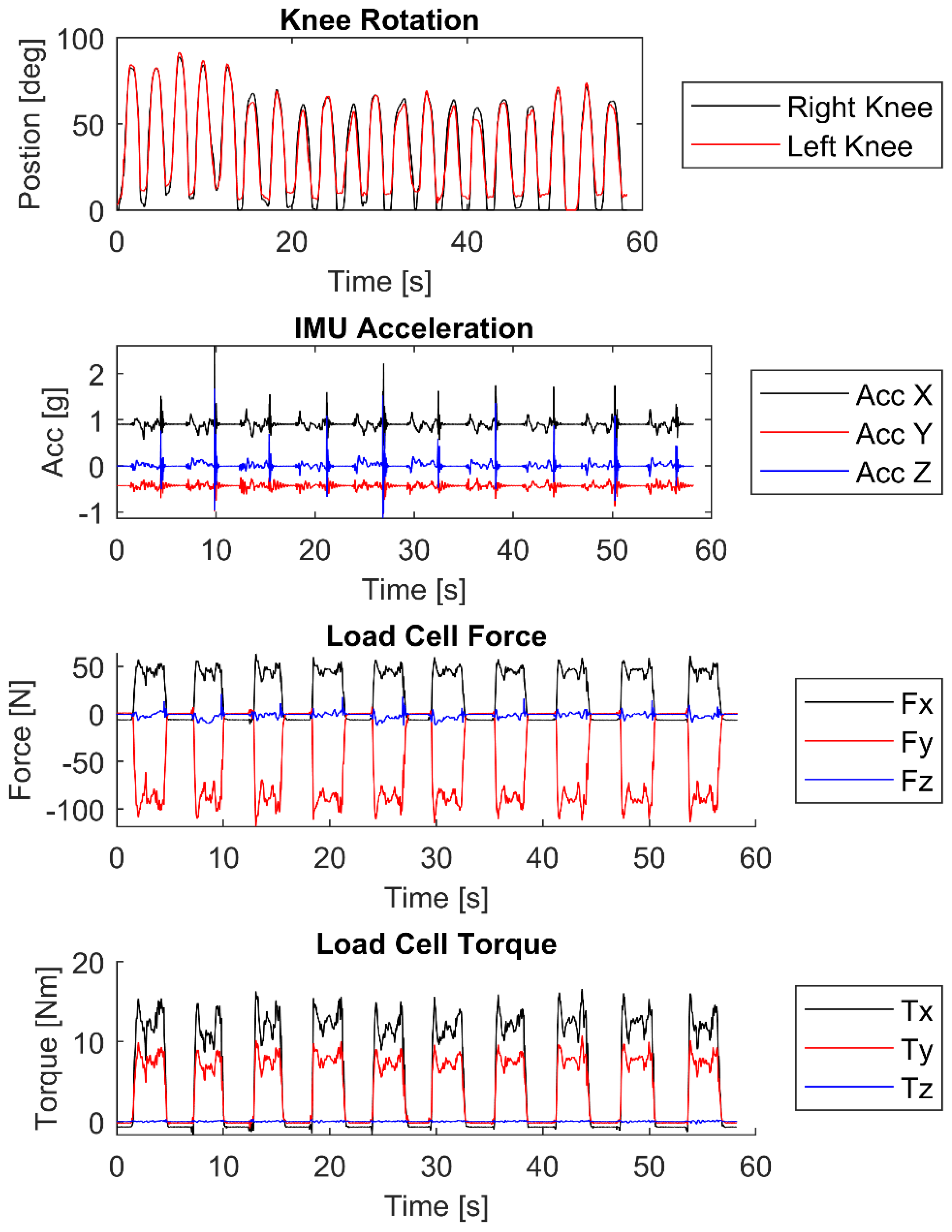

7.3. Data Sample

There is a large amount of data in the library and many different actions/objects. An example of the data is shown in Figure 13. Using the cut dataset from VICON the AddBiomechanics dataset was generated. An example of the motion data that is included in the AddBiomechanics output is shown in Figure 13. The data shown is the right and left knee angles of a subject picking up a briefcase and then setting it back down ten times. This is only a subset of the kinematic angles available in the dataset. The dataset contains joint angles and segment angles of the whole body in the MOT files in the AddBiomechanics folder. As seen from the knee data the angles of both knees increase as the subject bends down, reaches a position to grab the briefcase and then it decreases back to ~zero in a standing position. The subject then bends back down to place the briefcase on the ground and releases the handle.

Figure 13.

Example of typical data showing knee rotation from AddBiomechanics, IMU acceleration of the object when it is getting manipulated, and force and torque from the load cell of the subject lifting and manipulating a briefcase.

Figure 13.

Example of typical data showing knee rotation from AddBiomechanics, IMU acceleration of the object when it is getting manipulated, and force and torque from the load cell of the subject lifting and manipulating a briefcase.

Example data from the load cell and the IMU are also presented in Figure 13. This data is aligned with respect to the time of the cut VICON and AddBiomechanics data. When the object is interacted with, the load cell and IMU signals vary. An example of the accelerometer data is shown in Figure 13. Spikes correlate to when the briefcase is picked up and when it is set back down. Non-zero forces and torques between the spikes correlate to the load cell data measured while the subject lifts and lowers the briefcase. The load cell data then returns to ~zero when the briefcase is set on the ground and released.

8. Conclusion

We have presented a database characterizing human interaction with medium to large size objects from daily living. Unique to this database is its focus on characterizing data important for representing haptic interaction with objects, such as interaction forces, inertial measurements, and object motion, in addition to normal human biomechanical data. Such information can be useful for researchers working in ergonomics, biomechanics, robotics, virtual reality, and gaming.

Methods for collecting the data are presented. The various sensors used to create this database are described. Motion capture marker locations on the human subjects and objects are indicated. Data processing through VICON, AddBiomechanics, and MATLAB are presented to produce data that is useful for future applications. An example subset of data is presented to show the output of one of our trials for one object interaction trial.

Future work includes continuing to grow the database, identifying object properties, and characterizing human interaction with those objects. Object characteristics will then be programmed into haptic manipulators. Similar studies to those presented here will evaluate human subjects interacting with the manipulators and will be added to this database.

Supplementary Materials

Library Databases will be available at AddBiomechanics.com, github.com and simtk.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L., N.B., J.H., and M.M.; methodology, N.L., N.B., J.F.G., J.H., M.M.; software, N.L., N.B., and J.F.G.; validation, N.L., N.B., and J.F.G.; formal analysis, N.L. and J.F.G.; investigation, N.L., N.B.,J.H., M.M.; resources, N.L. and M.M.; data curation, N.L. and M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, N.L., N.B., and M.M.; writing—review and editing, N.L. and M.M.; visualization, N.L., J.H., and M.M.; supervision, N.L., J.H., and M.M.; project administration, M.M.; funding acquisition, N.L., J.H., and M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the US National Science Foundation, grant number 1911194.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Utah (IRB_00123921).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this library is freely available for public use.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Sasha McKee and Derrick Greer for their efforts to create the cart and wheelbarrow objects. We would also like to thank Jaden Hunter for his help processing VICON data.

Conflicts of Interest

authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- T. Feix, I. M. Bullock, and A. M. Dollar, “Analysis of human grasping behavior: Object characteristics and grasp type,” IEEE transactions on haptics, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 311-323, 2014.

- C. Mandery, Ö. Terlemez, M. Do, N. Vahrenkamp, and T. Asfour, “The KIT whole-body human motion database,” in 2015 International Conference on Advanced Robotics (ICAR), 2015: IEEE, pp. 329-336. [Online].

- C. Mandery, Ö. Terlemez, M. Do, N. Vahrenkamp, and T. Asfour, “Unifying representations and large-scale whole-body motion databases for studying human motion,” IEEE Transactions on Robotics, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 796-809, 2016.

- A. Meixner, F. Krebs, N. Jaquier, and T. Asfour, “An Evaluation of Action Segmentation Algorithms on Bimanual Manipulation Datasets,” in 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2023: IEEE, pp. 4912-4919. [Online].

- S. Kang, K. Ishihara, N. Sugimoto, and J. Morimoto, “Curriculum-based humanoid robot identification using large-scale human motion database,” Frontiers in Robotics and AI, vol. 10, 2023.

- F. Krebs and T. Asfour, “A bimanual manipulation taxonomy,” IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 11031-11038, 2022.

- M. Emami, A. Bayat, R. Tafazolli, and A. Quddus, “A survey on haptics: Communication, sensing and feedback,” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, 2024.

- B. Varalakshmi, J. Thriveni, K. Venugopal, and L. Patnaik, “Haptics: state of the art survey,” International Journal of Computer Science Issues (IJCSI), vol. 9, no. 5, p. 234, 2012.

- A. El Saddik, “The potential of haptics technologies,” IEEE instrumentation & measurement magazine, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 10-17, 2007.

- T. E. Truong et al., “Evaluating the Effect of Multi-Sensory Stimulation on Startle Response Using the Virtual Reality Locomotion Interface MS. TPAWT,” in Virtual Worlds, 2022, vol. 1, no. 1: MDPI, pp. 62-81. [Online].

- M. Russo, J. Lee, N. Hogan, and D. Sternad, “Mechanical effects of canes on standing posture: beyond perceptual information,” Journal of NeuroEngineering and Rehabilitation, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1-13, 2022.

- E. W. McClain, “Simulation and Control of a Human Assistive Quadrupedal Robot,” The University of Utah, 2022.

- E. W. McClain and S. Meek, “Determining optimal gait parameters for a statically stable walking human assistive quadruped robot,” in 2018 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 2018: IEEE, pp. 1751-1756. [Online].

- T. Shen, M. R. Afsar, M. R. Haque, E. McClain, S. Meek, and X. Shen, “Quadrupedal human-assistive robotic platform (Q-HARP): Design, control, and Preliminary Testing,” Journal of Mechanisms and Robotics, vol. 14, no. 2, p. 021004, 2022.

- W. Zhu et al., “Human motion generation: A survey,” IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2023.

- G. Bassani, A. Filippeschi, and C. A. Avizzano, “A Dataset of Human Motion and Muscular Activities in Manual Material Handling Tasks for Biomechanical and Ergonomic Analyses,” IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 21, no. 21, pp. 24731-24739, 2021.

- J. H. Geissinger and A. T. Asbeck, “Motion inference using sparse inertial sensors, self-supervised learning, and a new dataset of unscripted human motion,” Sensors, vol. 20, no. 21, p. 6330, 2020.

- P. Kang, K. Zhu, S. Jiang, B. He, and P. Shull, “HBOD: A Novel Dataset with Synchronized Hand, Body, and Object Manipulation Data for Human-Robot Interaction,” in 2023 IEEE 19th International Conference on Body Sensor Networks (BSN), 2023: IEEE, pp. 1-4. [Online].

- P. Maurice et al., “Human movement and ergonomics: An industry-oriented dataset for collaborative robotics,” The International Journal of Robotics Research, vol. 38, no. 14, pp. 1529-1537, 2019.

- B. L. Bhatnagar, X. Xie, I. A. Petrov, C. Sminchisescu, C. Theobalt, and G. Pons-Moll, “Behave: Dataset and method for tracking human object interactions,” in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2022, pp. 15935-15946. [Online].

- Y. Wang et al., “Augmenting virtual reality terrain display with smart shoe physical rendering: A pilot study,” IEEE Transactions on Haptics, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 174-187, 2020.

- P. Sabetian, “Modular Cable-Driven Robot Development and Its Applications in Locomotion and Rehabilitation,” The University of Utah, 2019.

- L. D. Duffell, N. Hope, and A. H. McGregor, “Comparison of kinematic and kinetic parameters calculated using a cluster-based model and Vicon’s plug-in gait,” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part H: Journal of Engineering in Medicine, vol. 228, no. 2, pp. 206-210, 2014.

- N. Goldfarb, A. Lewis, A. Tacescu, and G. S. Fischer, “Open source Vicon Toolkit for motion capture and Gait Analysis,” Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, vol. 212, p. 106414, 2021.

- K. Werling et al., “AddBiomechanics: Automating model scaling, inverse kinematics, and inverse dynamics from human motion data through sequential optimization,” Plos one, vol. 18, no. 11, p. e0295152, 2023.

- A. Rajagopal, C. L. Dembia, M. S. DeMers, D. D. Delp, J. L. Hicks, and S. L. Delp, “Full-body musculoskeletal model for muscle-driven simulation of human gait,” IEEE transactions on biomedical engineering, vol. 63, no. 10, pp. 2068-2079, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).