Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Method

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Internal Consistency

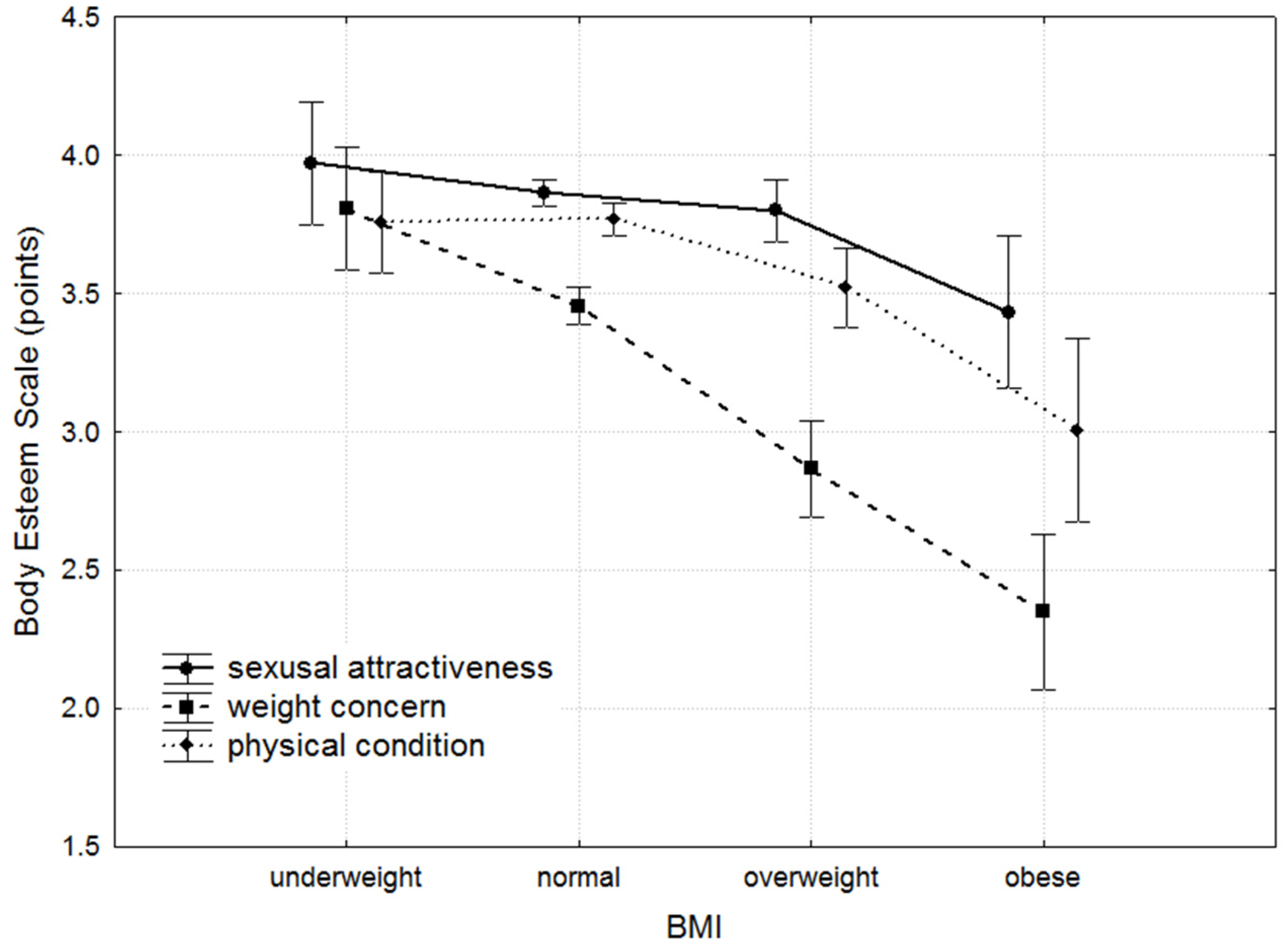

3.2. Body Mass Index

3.3. Sociodemographic Variables

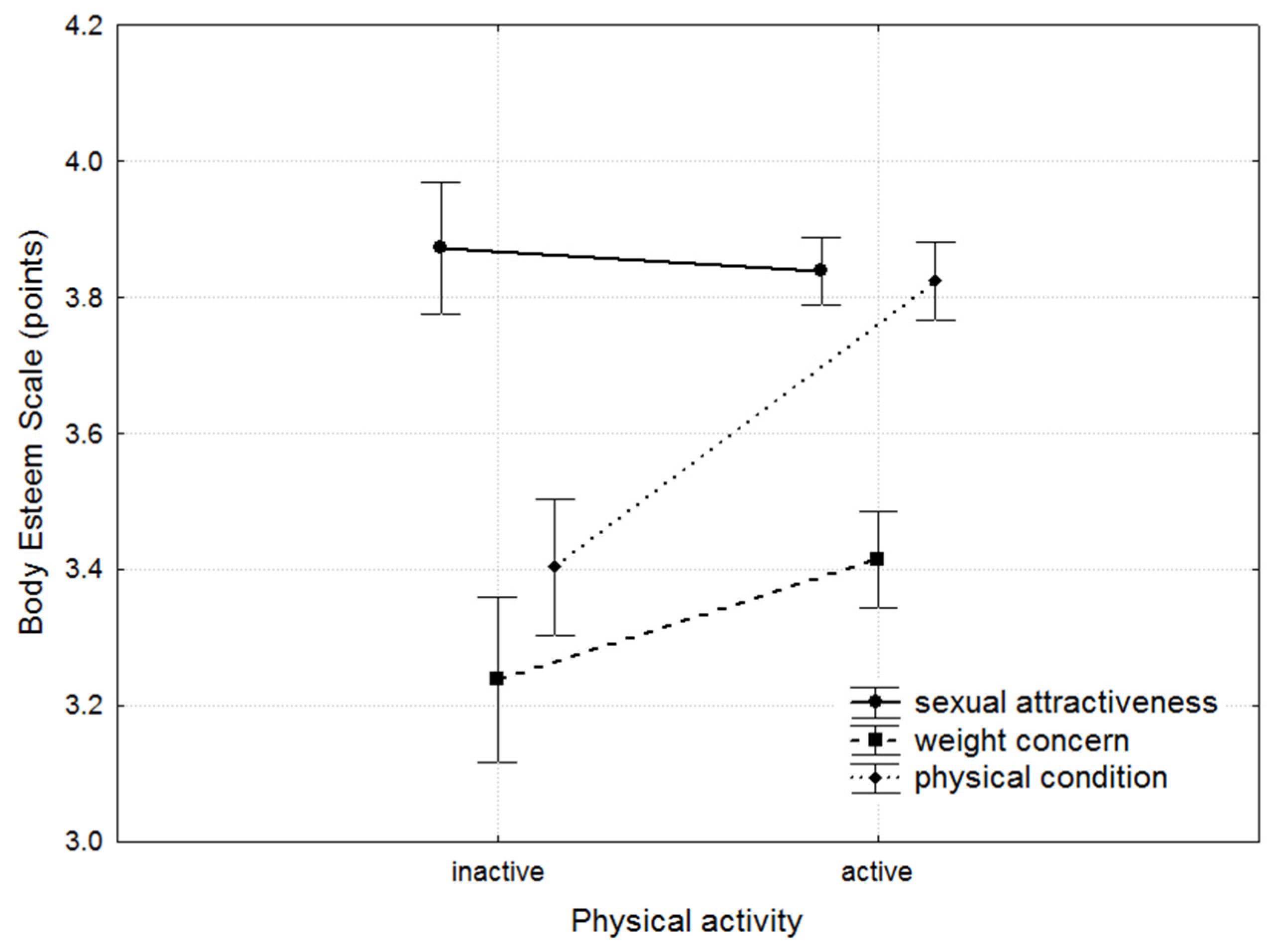

3.4. Physical Activity

3.5. Regression Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BI | Body Image |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| BES | Body Esteem Scale |

| SEWL | Subjective Experience of Work Load |

| PA | Physical Activity |

References

- Abbott, B.D. & Barber B.L. (2011). Differences in functional and aesthetic body image between sedentary girls and girls involved in sports and physical activity: Does sport type make a difference? Psychology of Sport and Exercise 12(3), 333-342. [CrossRef]

- Alleva, J.M. (2017). Shapeshifting: Focusing on body functionality to improve body image. Journal of Aesthetic Nursing, 6(6), 300-301. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, K.L., Janssen, I., Appelhans, B.M., Kazlauskaite, R., Karavolos, K., Dugan, S.A., Avery, E.A., Shipp-Johnson, K.J., Powell, L.H., & Kravitz, H.M. (2014). Body image satisfaction and depression in midlife women: the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN). Archives of Womens Mental Health, 17, 177-187. [CrossRef]

- Cash, T.F., Theriault, J.E., & Annis, N.M. (2004). Body image in an interpersonal context: Adult attachment, fear of intimacy, and social anxiety. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 89-102.

- Krawczyk, R., Menzel, J., & Thompson, J.K. (2012). Methodological issues in the study of body image and appearance. In N. Rumsey & D. Harcourt (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of the psychology of appearance (pp. 605-619). Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Pop, CL. (2017). Physical Activity, Body Image, and Subjective Well-Being. Well-being and Quality of Life—Medical Perspective, Mukadder Mollaoglu, Intech Open. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, L.A. (2004). Physical attractiveness: A sociocultural perspective. In T.F. Cash & T. Pruzinsky (Eds.), Body Images: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice (pp. 13-21). Guilford Press.

- Avalos, L., Tylka, T.L., & Wood-Barcalow, N. (2005).The Body Appreciation Scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image, 2, 285-297. [CrossRef]

- Wood-Barcalow, N.L., Tylka, T.L., & Augustus-Horvath, C.L. (2010).“But I like my body”: Positive body image characteristics and a holistic model for young-adult women. Body Image, 7, 106-116. [CrossRef]

- Tylka, T.L. (2012). Positive psychology perspectives on body image. In T.F. Cash (Ed.). Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance. (vol.2, pp: 657-663). San Diego Academic Press.

- Tylka, T.L., & Wood-Barcalow, N.L. (2015). What is and what is not positive body image? Conceptual foundations and construct definition. Body Image, 14, 118-129. [CrossRef]

- Swami, V., Weis, L., Barron, D., Furnham, A. (2018). Positive body image is positively associated with hedonic (emotional) and eudaimonic (psychological and social) well-being in british adults. The Journal of Social Psychology, 158(5), 541-552. [CrossRef]

- Swami, V., Airs, N., Chouhan, B., Leon, M.A.P., & Towell, T. (2009). Are there ethnic differences in positive body image among female British undergraduates? European Psychologist, 14, 288-296. [CrossRef]

- Swami, V., Campana, A.N., & Coles, R. (2012). Acceptance of cosmetic surgery among British female university students: Are there ethnic differences? European Psychologist, 17, 55-62. [CrossRef]

- Tylka, T.L., & Kroon Van Diest, A.M. (2013).The Intuitive Eating Scale—2: Item refinement and psychometric evaluation with college women and men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60, 137-153. [CrossRef]

- Alleva, J.M., Medoch, M.M., Priestley, K., Philippi, J.L., Hamaekers, J., Salvinho, E.N., Sanne, H., Custers, M. (2021). “I appreciate your body, because…” Does promoting positive body image to a friend affect one’s own positive body image? Body image, 3(36), 134-138. [CrossRef]

- Allen, M.S., & Walter, E.E. (2016). Personality and body image: A systematic review. Body Image, 19, 79-88. [CrossRef]

- Bessenoff, G.R. (2006). Can the media affect us? Social comparison, self-discrepancy, and the thin ideal. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 239-251. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, F., & Wardle, J. (2005). Dietary restraint, body image dissatisfaction, and psychological distress: a prospective analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114, 119. [CrossRef]

- Przezdziecki, A., Sherman, K. A., Baillie, A., Taylor, A., Foley, E., & Stalgis-Bilinski, K. (2013). My changed body: Breast cancer, body image, distress and self-compassion. Psycho-Oncology, 22, 1872-1879. [CrossRef]

- Woertman, L., & van den Brink, F. (2012). Body image and female sexual functioningand behavior: A review. Journal of Sex Research, 49, 184-211. [CrossRef]

- Levine, M. P., & Piran, N. (2004). The role of body image in the prevention of eating disorders. Body Image 1, 57-70. [CrossRef]

- Menzel, J.E., Schaefer, L.M., Burke, N.L., Mayhew, L.L., Brannick, M.T., & Thompson, J.K. (2010). Appearance-related teasing, body dissatisfaction, and disorder edeating: A meta-analysis. Body Image, 7, 261-270. [CrossRef]

- Dionne, M.M., & Davis, C. (2012). Body image and personality. In T.F. Cash (Ed.). Encyclopedia of body image and human appearance (pp. 136-140). Elsevier.

- Grabe, S., Ward, L.M., & Hyde, J.S. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 460-476. [CrossRef]

- Bell, B.T., & Dittmar, H. (2011). Does media type matter? The role of identification in adolescent girls’ media consumption and the impact of different thin-ideal media on body image. Sex Roles, 65, 478. [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, C.J., Munoz, M.E., Contreras, S., & Velasquez, K. (2011). Mirror, mirror on the wall: peer competition, television influences, and body image dissatisfaction. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 30, 458-483. [CrossRef]

- Levine, M.P., & Chapman, K. (2011). Media influences on body image. In T.F. Cash, & L. Smolak (Eds.). Body Image: A Handbook of science, practice, and prevention (2nd ed., pp. 101-109). Guilford Press.

- McCabe, M.P., & McGreevy, S.J. (2011). Role of media and peers on body change strategies among adult men: is body size important? European Eating Disorders Review, 19, 438-446. [CrossRef]

- Abraczinskas, M., Fisak, B., & Barnes, R.D. (2012). The relation between parental influence, body image, and eating behaviors in a nonclinical female sample. Body Image 9, 93-100. [CrossRef]

- Chrisler, J.C., & Ghiz, L. (1993). Body image issues of older women. Women & Therapy, 14(1), 67-75.

- Mercurio, A.E., & Landry, L.J. (2008). Self-objectification and well-being: The impact of self-objectification on women’s overall sense of self-worth and life satisfaction. Sex Roles, 58, 458-466. [CrossRef]

- Choma, B. L., Shove, C., Busseri, M. A., Sadava, S. W., & Hosker, A. (2009). Assessing the role of body image coping strategies as mediators or moderators of the links between self-objectification, body shame, and well-being. Sex Roles, 61, 699-713. [CrossRef]

- Albawardi, N.M., AlTamimi, A.A., AlMarzooqi, M.A., Alrasheed, L., & Al-Hazzaa, H.M. (2021). Associations of body dissatisfaction with lifestyle behaviors and socio-demographic factors among saudi females attending fitness centers. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 611472. [CrossRef]

- Mendelson, B.K., Mendelson, M.J., & White, D.R. (2001). Body Esteem Scale for adolescents and adults. Journal of Personality Assessment, 76(1), 90-106. [CrossRef]

- Baecke, J.A., Burema, J., & Frijters, J.E. (1982). A short questionnaire for the measurement of habitual physical activity in epidemiological studies. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 36, 936-42.

- Hertogh, E.M., Monninkhof, E.M., Schouten, E.G. et al. (2008). Validity of the Modified Baecke Questionnaire: comparison with energy expenditure according to the doubly labeled water method. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition & Physical Activity, 5, 30. [CrossRef]

- Ahern, A.L., Bennett, K.M., Kelly, M., & Hetherington, M.M. (2011). A qualitative exploration of young women’s attitudes towards the thin ideal. Journal of Health Psychology, 16(1),70-9. [CrossRef]

- Swami, V., & Smith, J.-M. (2012). How not to feel good naked? The effects of television programs that use ‘real women’ on female viewers’ body image and mood. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 31, 151-68. [CrossRef]

- Swami, V., Tran, U.S., Stieger, S., Voracek, M. (2015). Associations between women’s body image and happiness: Results of the YouBeauty.com Body Image Survey (YBIS). Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 705-718. [CrossRef]

- Diekman, A.B., & Goodfiernd, W.(2006). Rolling with the changes: A role congruity perspective on gender norms. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 30, 369-383. [CrossRef]

- Hὂnekopp, J., Rudolph, U., Beier, L., Liebert, A., & Mὕller, C. (2007). Physical attractiveness of face and body as indicators of physical fitness in men. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28, 106-111. [CrossRef]

- Henss, R. (2000). Waist-to-hip ratio and female attractiveness. Evidence from photographic stimuli and methodological considerations. Personality and Individual Diferences 28, 501-513. [CrossRef]

- Agliata, D., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (2004). The impact of media exposure on males’ body image. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23, 7-22. [CrossRef]

- Platek, S.M., & Singh, D. (2010). Optimal Waist-to-Hip Ratios in Women Activate Neural Reward Centers in Men. PLoS ONE, 5(2), e9042. [CrossRef]

- Garza, R., Heredia, R.R., Cieslicka, A.B. (2016). Male and Female Perception of Physical Attractiveness: An Eye Movement Study. Evolutionary Psychology, 14(1). [CrossRef]

- Ladabaum, U., Mannalithara, A., Myer, P.A., Singh, G. (2014). Obesity, abdominal obesity, physical activity, and caloric intake in US adults: 1988 to 2010. The American Journal of Medicine, 127(8), 717-727. [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, D.R., Jones, B.C., DeBruine, L.M., Moore, F.R., Law Smith, M.J., Cornwell, E., Tiddeman, B.P., Boothroyd, L.G., & Perrett, D.I. (2005). The voice and face of woman: One ornament that signals quality?, Evolution and Human Behavior,26(5) 398-408. [CrossRef]

- Bovet, J., Barkat-Defradas, M., Durand, V., Faurie, C., & Raymond, M. (2018), Women’s attractiveness is linked to expected age at menopause. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 31, 229-238. [CrossRef]

- Cutler, W.B., & Genovese, E. (2009). Pheromones, sexual attractiveness and quality of life in menopausal women, Climacteric, 5(2), 112-121. [CrossRef]

- Séjourné. N., Got, F., Solans, C., & Raynal, P. (2019). Body image, satisfaction with sexual life, self-esteem, and anxiodepressive symptoms: A comparative study between premenopausal, perimenopausal, and postmenopausal women. Journal of Women Aging. 31(1), 18-29. [CrossRef]

- Jiannine, L.M. (2018). An investigation of the relationship between physical fitness, self-concept, and sexual functioning. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 7(1), 57. [CrossRef]

- Graff Low, K., Charanasomboon, S., Brown, C., Hiltunen, G., Long, K., Reinhalter, K., & Jones, H. (2003). Internalization of the thin ideal, weight, and body image concerns. Social Behavior and Personality: An international journal, 31(1), 81-90. [CrossRef]

- Wronka, I., Suliga, E., Pawlińska-Chmara, R. (2013). Perceived and desired body weight among female university students in relation to BMI-based weight status and socio-economic factors. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 20(3), 533-538.

- World Health Organization. (2021). Obesity and overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- Zaborskis, A., Petronyte, G., Sumskas, L., Kuzman, M., & Iannotti, R.J. (2008). Body image and weight control among adolescents in Lithuania, Croatia, and the United States in the context of global obesity. Croatian medical journal, 49(2), 233-242. [CrossRef]

- Park, E. (2011). Overestimation and underestimation: adolescents’ weight perception in comparison to BMI-based weight status and how it varies across socio-demographic factors. Journal of School Health, 81(2), 57-64. [CrossRef]

- Metcalf, P.A., Scragg, R.K.R., Willoughby, P., Finau, S., & Tipene-Leach, D. (2000). Ethnic differences in perceptions of body size in middle-aged European, Maori and Pacific People living in New Zealand. International Journal of Obesity, 24(5), 593-599. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M., & Berenson, A.B. (2010). Self-perception of weight and its association with weight-related behaviors in young, reproductive-aged women. Obstetrics and gynecology, 116(6), 1274-1280. [CrossRef]

- Hausenblas, A.A., & Fallon, E.A. (2006). Exercise and body image: A meta-analysis, Psychology & Health, 21(1), 33-47. [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.A.S., Nahas, M.V., Sousa, T.F., Del Duca, G.F., & Peres, K.G. (2011). Prevalence and associated factors with body image dissatisfaction among adults in southern Brazil: a population-based study. Body Image, 8, 427-431. [CrossRef]

- Holmqvist, K., & Frisen, A. (2010). Body dissatisfaction across cultures: findings and research problems. European Eat Disorder Reviev 18, 133-146. [CrossRef]

| Variable | Age group | Total | ||||||||

| 18-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | |||||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| SA | -0.02 | ns | -0.34 | *** | -0.05 | ns | -0.12 | ns | -0.12 | ** |

| WC | -0.42 | *** | -0.54 | *** | -0.30 | * | -0.26 | ns | -0.42 | *** |

| PC | -0.14 | ** | -0.37 | *** | -0.50 | *** | -0.33 | ns | -0.24 | *** |

| Variable | BMI | Age group | Total | ||||||||

| 18-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | ||||||||

| Me | p | Me | p | Me | p | Me | p | Me | p | ||

| SA | a: U | 3.85 | 3.54 | 4.62 | 3.69 | 3.85 | |||||

| b: N | 3.92 | 4.08 | 3.62 | 3.85 | 3.92 | ||||||

| c: OV | 3.92 | 3.85 | 3.58 | 3.58 | 3.77 | a-d* | |||||

| d: OB | 3.69 | ns | 3.27 | b-d** | 3.73 | ns | 2.69 | ns | 3.62 | b-d** | |

| WC | a-b* | a-b* | |||||||||

| a: U | 4.00 | a-c** | 3.60 | 4.30 | 3.40 | 4.00 | a-c*** | ||||

| b: N | 3.50 | a-d*** | 3.40 | a-d* | 3.60 | 3.50 | 3.50 | a-d*** | |||

| c: OV | 2.50 | b-c*** | 2.90 | b-c* | 2.85 | 3.60 | 2.80 | b-c*** | |||

| d: OB | 2.20 | b-d* | 2.00 | b-d*** | 3.05 | ns | 2.30 | ns | 2.30 | b-d*** | |

| PC | a: U | 3.67 | 4.50 | 4.33 | 4.22 | 3.78 | |||||

| b: N | 3.89 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 3.78 | 3.89 | a-d*** | |||||

| c: OV | 3.50 | 3.44 | 3.39 | 3.89 | 3.56 | b-c** | |||||

| d: OB | 3.06 | ns | 2.83 | b-d* | 3.50 | ns | 2.83 | ns | 3.17 | b-d*** | |

| Variable | Category | n (%) | SA | WC | PC | |||

| Me | p | Me | p | Me | p | |||

| education level (n=740) |

a:basic professional | 62 (8.38 | 3.54 | a-b*** a-c*** |

3.30 | ns | 3.89 | ns |

| b: high school | 220 (29.73) | 3.92 | 3.50 | 3.67 | ||||

| c: university | 458 (61.89) | 3.92 | 3.40 | 3.78 | ||||

| professional status (n=740) |

d: student | 345 (46.62) | 3.85 | ns | 3.40 | ns | 3.67 | d-e* |

| e: working | 296 (40.00) | 3.85 | 3.50 | 3.89 | ||||

| f:not working | 99 (13.38) | 3.77 | 3.40 | 3.88 | ||||

| marital status (n=656) |

g: single | 174 (26.52) | 3.77 | ns | 3.30 | ns | 3.78 | ns |

| h: in relationship | 482 (73.48) | 3.92 | 3.40 | 3.67 | ||||

| material status (n=581) |

i:low | 160 (27.54) | 3.96 | i-j** | 3.50 | ns | 3.89 | j-k* |

| j: average | 223 (38.38) | 3.77 | 3.40 | 3.67 | ||||

| k: high | 198 (34.08) | 3.92 | 3.60 | 3.89 | ||||

| age (years) (n=740) |

l: 18-29 | 551 (74.46) | 3.92 | 3.50 | 3.78 | |||

| m: 30-39 | 106 (14.32) | 3.85 | 3.10 | 3.67 | ||||

| n: 40-49 | 50 (6.76) | 3.62 | 3.40 | 3.67 | ||||

| o: 50-59 | 33 (4.46) | 3.69 | ns | 3.50 | a-b* | 3.78 | ns | |

| Variable | Age group | Total | ||||||||

| 18-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | |||||||

| r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | r | p | |

| SA | 0.13 | ** | 0.02 | ns | 0.16 | ns | 0.35 | * | 0.13 | ** |

| WC | 0.12 | * | 0.09 | ns | 0.20 | ns | 0.16 | ns | 0.13 | ** |

| PC | 0.43 | *** | 0.32 | ** | 0.34 | * | 0.32 | ns | 0.40 | *** |

| Variable | Activity | Age group | Total | ||||||||

| 18-29 | 30-39 | 40-49 | 50-59 | ||||||||

| Me | p | Me | p | Me | p | Me | p | Me | p | ||

| SA | A | 3.85 | ns | 3.77 | ns | 3.62 | ns | 3.65 | ns | 3.85 | ns |

| IN | 3.92 | 4.00 | 3.62 | 3.69 | 3.92 | ||||||

| WC | A | 3.50 | ns | 3.10 | * | 3.40 | ns | 3.50 | ns | 3.50 | * |

| IN | 3.40 | 3.00 | 3.90 | 3.40 | 3.30 | ||||||

| PC | A | 3.89 | *** | 3.89 | ** | 3.67 | ns | 3.89 | ns | 3.89 | *** |

| IN | 3.33 | 3.33 | 3.67 | 3.33 | 3.33 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).