Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Statistical Analysis and Data Presentation

3. Results

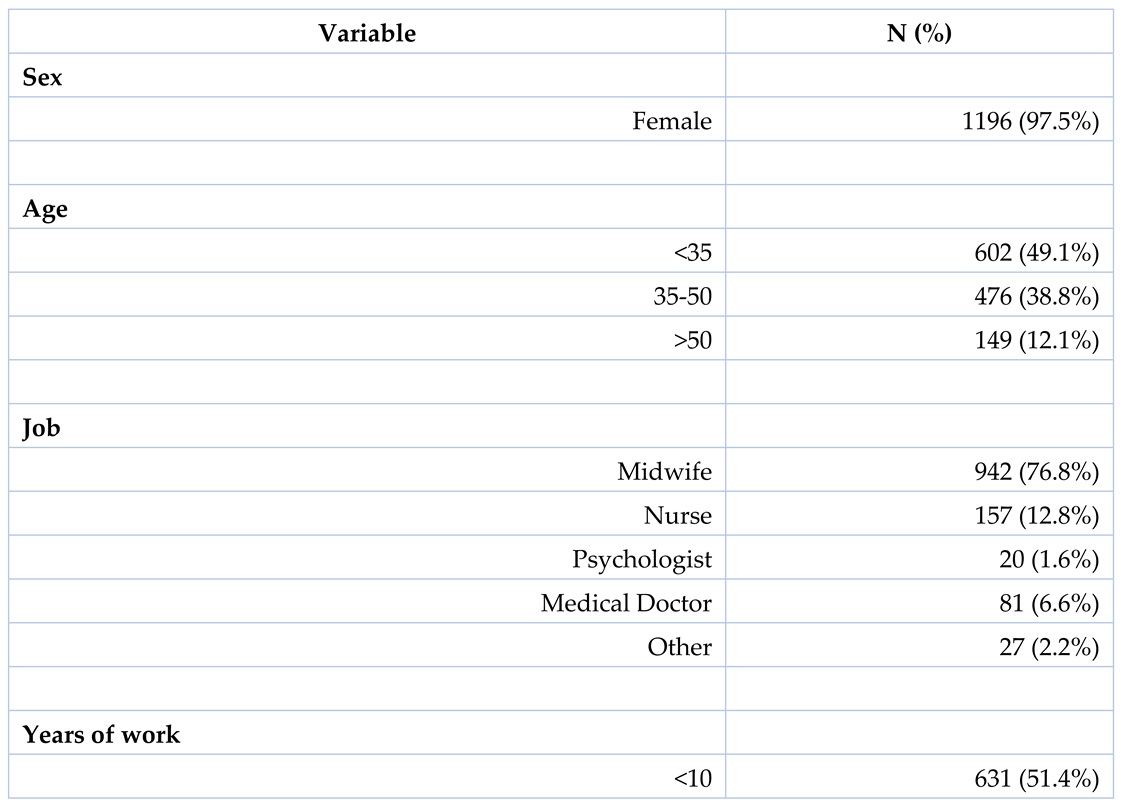

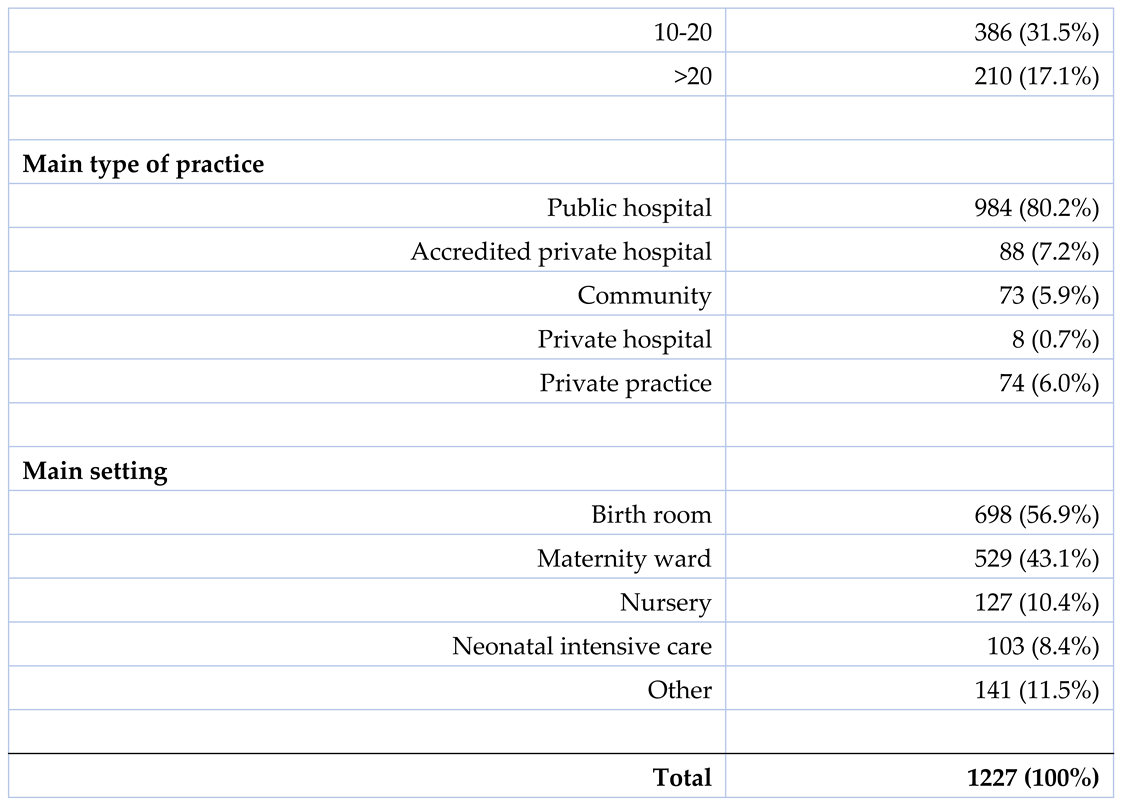

3.1. Sample Characteristics

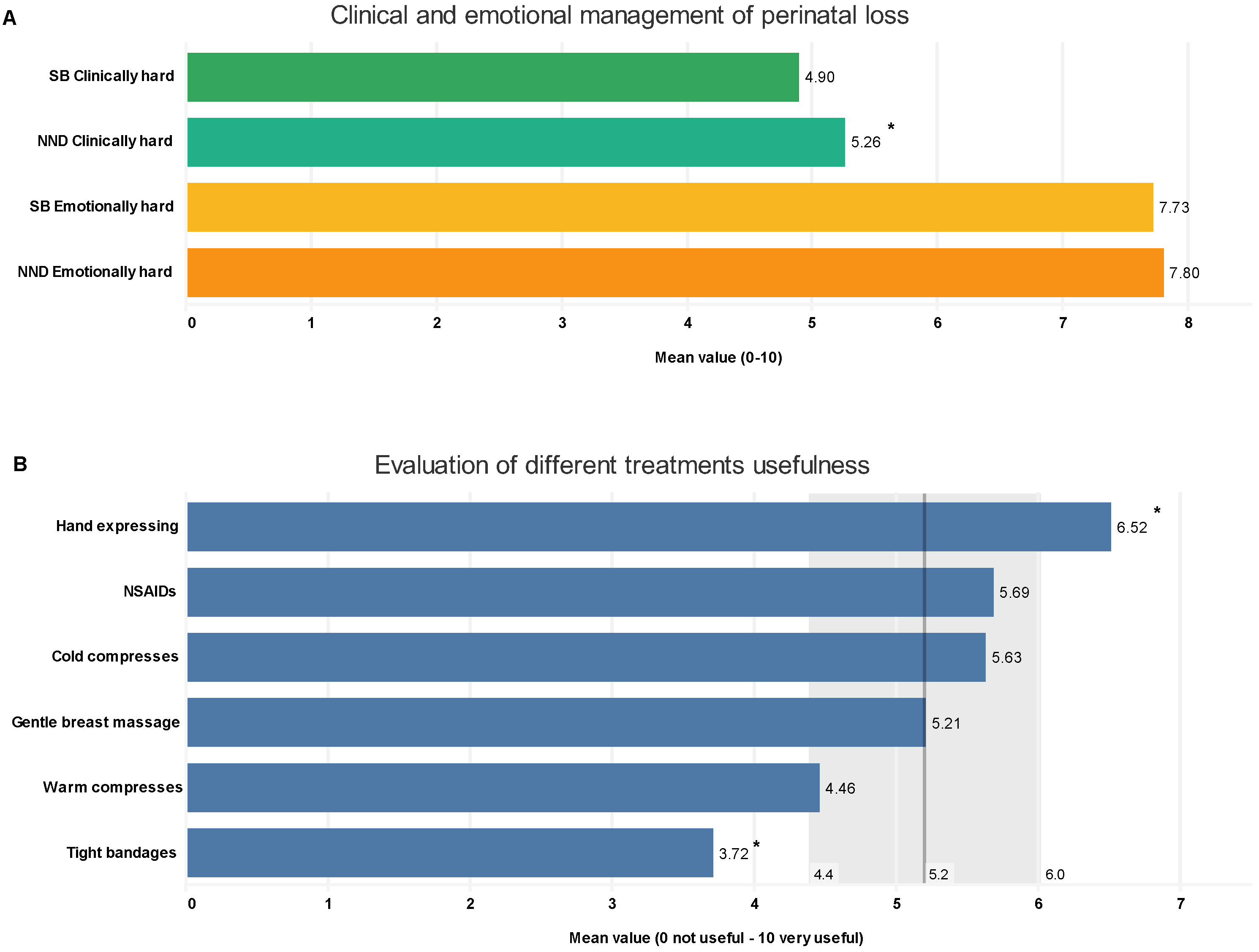

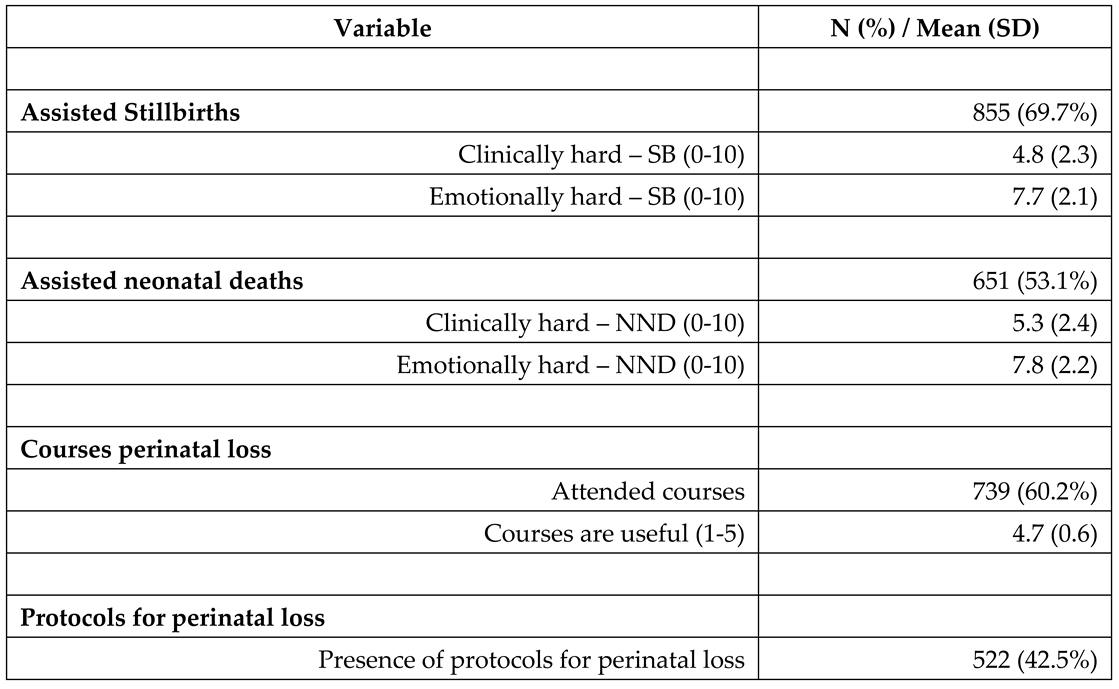

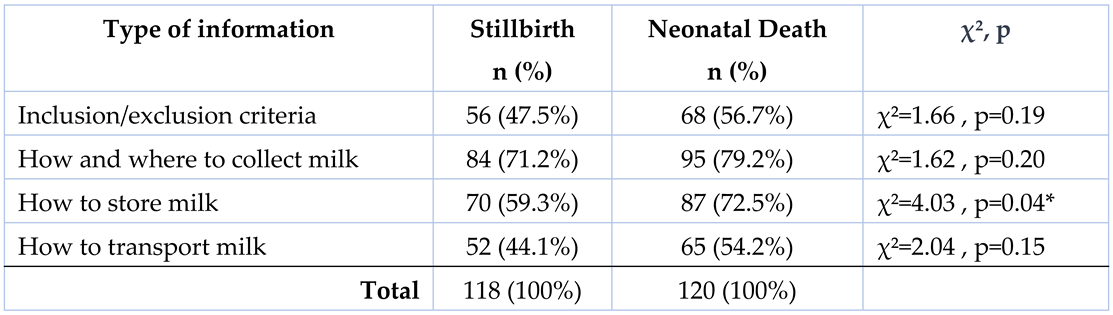

3.2. Perinatal Loss Management

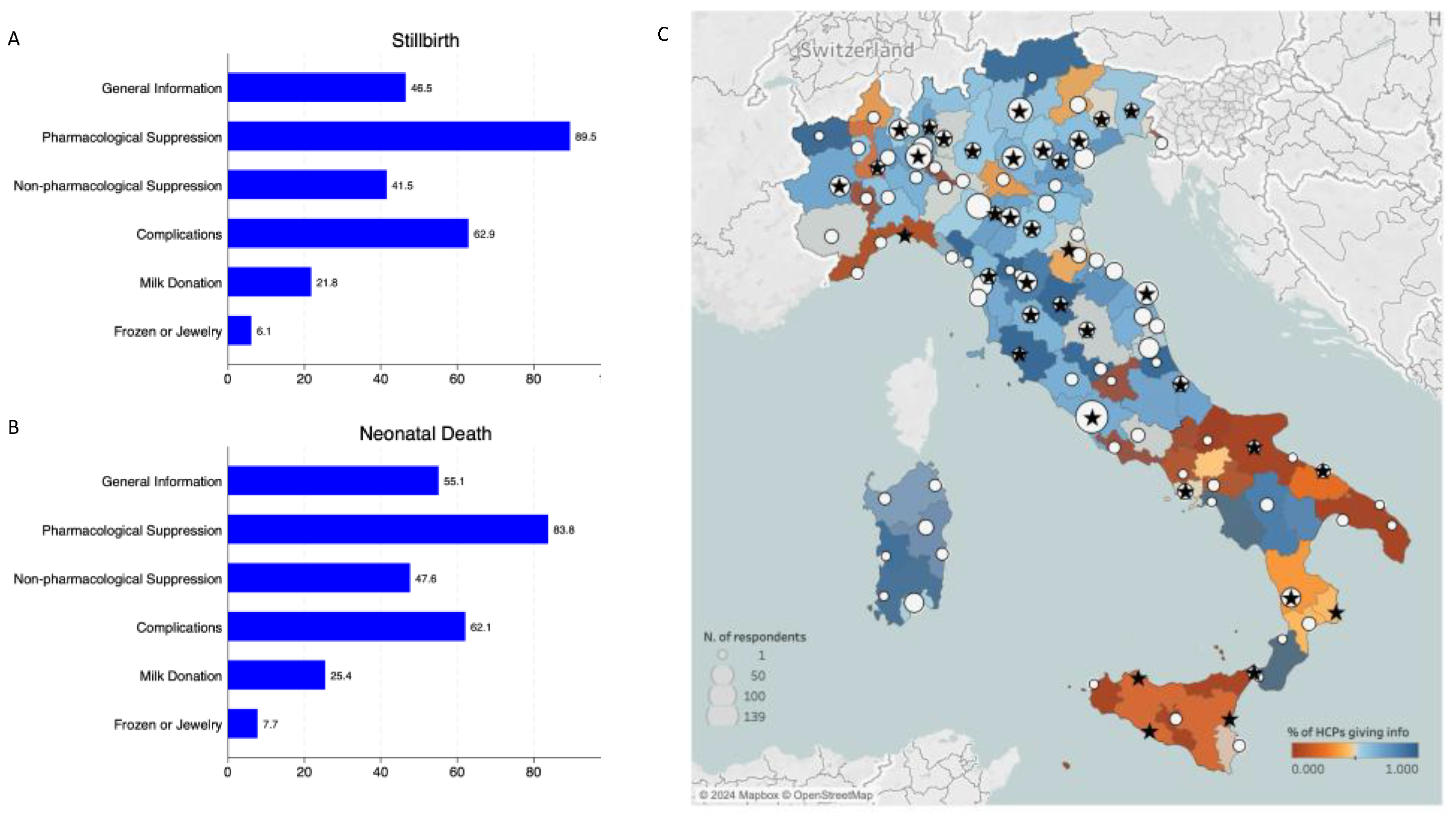

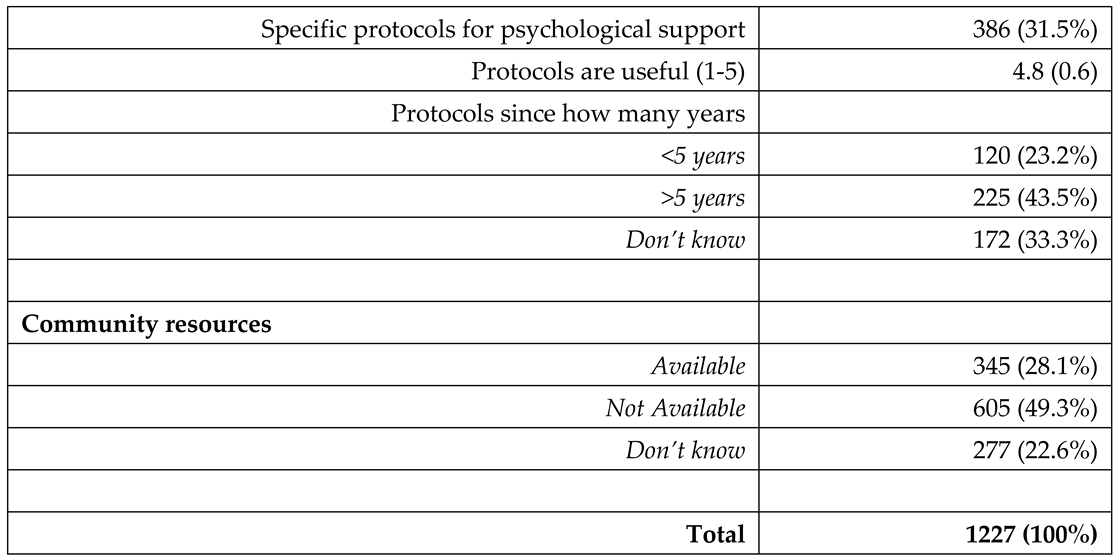

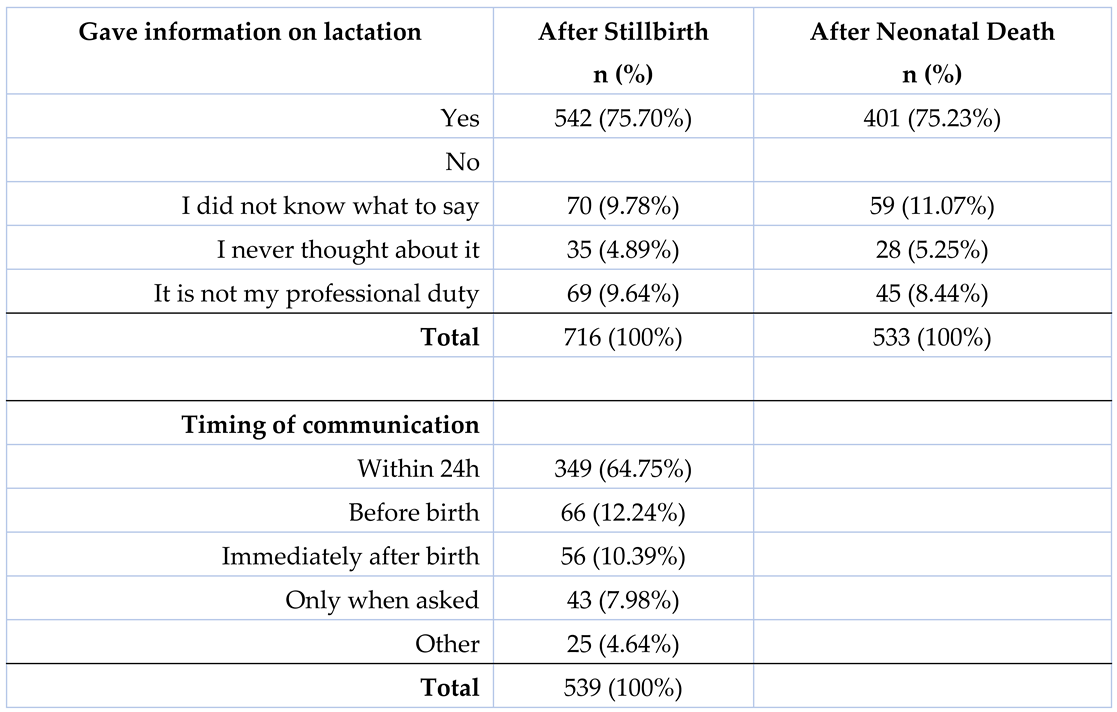

3.3. Information on Lactation After Perinatal Loss

3.4. Follow Up and Outpatient Services

3.5. Open-Ended Questions

- Communication (m 66 / s 8.6): emerged as a fundamental aspect, underscoring the vital role of effective, empathetic communication in navigating the delicate circumstances surrounding perinatal loss. Its high frequency and score indicated its paramount importance in providing sensitive and supportive care.

- Finding the right words (m 60 / s 7.4): this theme, with its significant score, highlighted the profound challenge healthcare professionals faced in articulating comfort and empathy. It reflected the intricacy of verbalising support in a way that acknowledged the immense grief while offering solace.

- Empathy (m 39 / s 5.9): A critical component, illustrating the need for healthcare providers to connect emotionally and understand the depth of the parents’ loss, while maintaining professional boundaries.

- Pain (m 30 / s 4.5): Captured both the physical anguish of the mother and the emotional suffering of all involved. This theme’s notable presence in the responses underscored the pervasive impact of grief and loss in these scenarios.

- Helplessness/Impotence (m 25 / s 3.8): Reflected a sense of powerlessness often felt by professionals in the face of such profound loss, impacting their sense of efficacy and contributing to emotional strain.

- Bureaucracy (m 13 / s 2.3): Particularly highlighted in stillbirths, this theme points to the complexities and challenges of navigating administrative procedures during emotionally charged times, adding another layer of difficulty to the care process.

- Not crying (m 9 / s 2.7): More pronounced in stillbirths, it signifies the struggle of healthcare professionals to manage their own emotional responses in a professional setting, illustrating the personal impact of these events.

- Silence (m 8 / s 1.7): Unique to stillbirths, this theme encompassed the literal absence of the newborn’s sounds and the broader societal reticence surrounding stillbirths. It may symbolise the profound depth of loss and the emotional complexities entwined in providing care.

4. Discussion

“I didn’t feel up to the task of caring for the couples in such a very delicate and intimate moment for them”.A young midwife

“Staff training is essential and [care] should not be left to chance or rely on personal empathy in difficult situations such as the puerperium period or the management of lactation of a woman who suffered a perinatal loss.”A nurse

“I believe it is right that a couple has to know every option. Grieving parents could decide to transform what they have into a gift for other families.”A midwife

4.1. Strength and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| HCPs | Healthcare Professionals |

| NICU | Neonatal Intensive Care Unit |

| HMBs | Human Milk Banks |

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

| UN IGME | United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation |

| PSANZ | Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand |

References

- United Nations Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME). A Neglected Tragedy: the global burden of stillbirths. New York: United Nations Children’s Fund, 2020.

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Newborn Mortality [cited 2023 Aug 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/levels-and-trends-in-child-mortality-report-2021.

- EpiCentro [Internet]. Stillbirth, i dati 2019 [cited 2023 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/materno/stillbirth-report-2020.

- Westby CL, Erlandsen AR, Nilsen SA, Visted E, Thimm JC. Depression, anxiety, PTSD, and OCD after stillbirth: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21(1):782. [CrossRef]

- Noble-Carr D, Carroll K, Copland S, Waldby C. Providing Lactation Care Following Stillbirth, Neonatal and Infant Death: Learning from Bereaved Parents. Breastfeed Med Off J Acad Breastfeed Med 2023;18(4):254-64.

- Carroll K, Noble-Carr D, Sweeney L, Waldby C. The “Lactation After Infant Death (AID) Framework”: a guide for online health information provision about lactation after stillbirth and infant death. J Hum Lact 2020;36(3):480-91. [CrossRef]

- Fondazione Confalonieri Ragonese. Gestione della morte endouterina fetale (MEF). Prendersi cura della natimortalità. SIGO, AOGOI, AGUI, 2023.

- Perinatal Society of Australia and New Zealand (PSANZ). Clinical Practice Guideline for Care Around Stillbirth and Neonatal Death: Version 3.4. 2020.

- Welborn JM. The experience of expressing and donating breast milk following a perinatal loss. J Hum Lact 2012;28(4):506-10. [CrossRef]

- Waldby C, Noble-Carr D, Carroll K. Mothers, milk and mourning: the meanings of breast milk after loss of an infant. Sociol Health Illn 2023;45(1):109-27. [CrossRef]

- McDonnell A, Butler M, White J, et al. National Clinical Practice Guideline: Stillbirth – Prevention, Investigation, Management and Care. National Women and Infants Health Programme and The Institute of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, 2023.

- Pope CJ, Mazmanian D. Breastfeeding and postpartum depression: an overview and methodological recommendations for future research. Depress Res Treat 2016;2016:4765310. [CrossRef]

- Herbert D, Young K, Pietrusińska M, MacBeth A. The mental health impact of perinatal loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2022;297:118–29. [CrossRef]

- Blackmore ER, Côté-Arsenault D, Tang W, et al. Previous prenatal loss as a predictor of perinatal depression and anxiety. Br J Psychiatry 2011;198(5):373-8. [CrossRef]

- Dickens J. Lactation after loss: supporting women’s decision-making following perinatal death. Br J Midwifery 2020;28(7):442–8. [CrossRef]

- Ravaldi C, Levi M, Angeli E, et al. Stillbirth and perinatal care: are professionals trained to address parents’ needs? Midwifery 2018;64:53–9.

- Ravaldi C, Carelli E, Frontini A, et al. The BLOSSoM study: Burnout after perinatal LOSS in Midwifery. Results of a nation-wide investigation in Italy. Women Birth 2022;35(1):48–58. [CrossRef]

- Ravaldi C, Mosconi L, Mannetti L, et al. Post-traumatic stress symptoms and burnout in healthcare professionals working in neonatal intensive care units: results from the STRONG study. Front Psychiatry 2023;14:1050236. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson H, Whittington R, Perry L, Eames C. Examining the relationship between burnout and empathy in healthcare professionals: A systematic review. Burn Res 2017;6:18–29. [CrossRef]

- Ravaldi C, Mosconi L, Bonaiuti R, Vannacci A. The emotional landscape of pregnancy and postpartum during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: a mixed-method analysis using artificial intelligence. J Clin Med 2023;12(19):6140. [CrossRef]

- Heazell AEP, Siassakos D, Blencowe H, et al. Stillbirths: economic and psychosocial consequences. Lancet 2016;387(10018):604-16. [CrossRef]

- Puia DM, Lewis L, Beck CT. Experiences of obstetric nurses who are present for a perinatal loss. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2013;42(3):321-31. [CrossRef]

- Wallbank S, Robertson N. Predictors of staff distress in response to professionally experienced miscarriage, stillbirth and neonatal loss: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2013;50(8):1090-7. [CrossRef]

- McCreight BS. Perinatal grief and emotional labour: a study of nurses’ experiences in gynae wards. Int J Nurs Stud 2005;42(4):439-48. [CrossRef]

- Taranu SM, Ilie AC, Turcu A-M, et al. Factors associated with burnout in healthcare professionals. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19(22):14701. [CrossRef]

- Ravaldi C, Roper F, Mosconi L, Vannacci A. CLASS - CiaoLApo Stillbirth Support checklist: adherence to stillbirth guidelines and women’s psychological well-being. medRxiv 2023;23291084. [CrossRef]

- Pollock D, Ziaian T, Pearson E, Cooper M, Warland J. Understanding stillbirth stigma: A scoping literature review. Women Birth 2020;33(3):207-218. [CrossRef]

- Nuzum D, Meaney S, O’Donoghue K. The impact of stillbirth on consultant obstetrician gynaecologists: a qualitative study. BJOG 2014;121(8):1020-8. [CrossRef]

- Shakespeare C, Merriel A, Bakhbakhi D, et al. The RESPECT Study for consensus on global bereavement care after stillbirth. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2020;149(2):137-47. [CrossRef]

- Ministero dell’Istruzione dell’Università e della Ricerca [Internet]. Decreto Interministeriale 2 aprile 2001 - Determinazione delle classi delle lauree universitarie delle professioni sanitarie [cited 2024 Jan 23]. Available from: 2001 https://www.miur.it/0006Menu_C/0012Docume/0015Atti_M/1421CLASSE.htm.

- Spitz AM, Lee NC, Peterson HB. Treatment for lactation suppression: little progress in one hundred years. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;179(6 Pt 1):1485-90. [CrossRef]

- Oladapo OT, Fawole B. Treatments for suppression of lactation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;2012(9):CD005937. [CrossRef]

- Sands (Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Charity). National Bereavement Care Pathway - Neonatal Death. 2022.

- Sands (Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Society). National Bereavement Care Pathway - Stillbirth.

- McGuinness D, Coghlan B, Butler M. An exploration of the experiences of mothers as they suppress lactation following late miscarriage, stillbirth or neonatal death. Evidence Based Midwifery 2014;12(2):65-70.

- Fernández-Medina IM, Jiménez-Lasserrotte MDM, Ruíz-Fernández MD, Granero-Molina J, Fernández-Sola C, Hernández-Padilla JM. Milk Donation Following a Perinatal Loss: A Phenomenological Study. J Midwifery Womens Health 2022;67(4):463-469. [CrossRef]

- Cole M. Lactation after Perinatal, Neonatal, or Infant Loss. Clin Lact 2012;3:94–100. [CrossRef]

- Hallowell SG, Spatz DL, Hanlon AL, Rogowski JA, Lake ET. Characteristics of the NICU work environment associated with breastfeeding support. Adv Neonatal Care 2014;14(4):290-300. [CrossRef]

- Nisi GD, Moro GE, Arslanoglu S, et al. The third survey on the activity of human milk banks in Italy and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Nutr 2022;7(2):31–41.

- Health Service Executive Ireland. National Standards for Bereavement Care Following Pregnancy Loss and Perinatal Death. 2022.

- Salgado HO, Andreucci CB, Gomes ACR, Souza JP. The perinatal bereavement project: development and evaluation of supportive guidelines for families experiencing stillbirth and neonatal death in Southeast Brazil-a quasi-experimental before-and-after study. Reprod Health 2021;18:5. [CrossRef]

|

|

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).