1. Introduction

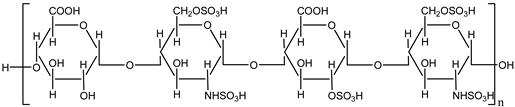

Heparin is a naturally occurring anticoagulant widely used in medical practice to prevent and treat thromboembolic disorders such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism (PE), and myocardial infarction (MI). It is derived from animal tissues, primarily porcine intestinal mucosa or bovine lung, and exists in two main forms: unfractionated heparin (UFH) and low molecular weight heparin (LMWH). Both forms function by enhancing the activity of antithrombin III, a plasma protein that inhibits thrombin and factor Xa, thereby disrupting the clotting cascade and preventing the formation of fibrin clots [

1].

Unfractionated heparin (UFH) is a heterogeneous mixture of polysaccharides with varying molecular weights, allowing it to bind to a variety of proteins. Its effects are rapid but require close monitoring due to an unpredictable dose-response relationship and the risk of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) [

1]. Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), on the other hand, offers a more predictable pharmacokinetic profile, greater bioavailability, and a lower risk of HIT, making it more suitable for outpatient use [

2].

Beyond its anticoagulant properties, heparin is being studied for its anti-inflammatory effects and potential use in other therapeutic areas such as oncology and viral infections [

3]. The clinical use of heparin is guided by specific indications, patient characteristics, and risk factors, ensuring optimal safety and efficacy in therapeutic and prophylactic regimens.

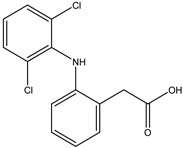

Diclofenac is a widely used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) with analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and antipyretic properties. It is primarily indicated for the treatment of pain and inflammation associated with conditions such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and musculoskeletal injuries. Diclofenac exerts its effects by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, COX-1 and COX-2, which are responsible for the synthesis of prostaglandins. Prostaglandins play a key role in mediating inflammation, pain, and fever [

4].

Available in various formulations, including oral tablets, topical gels, transdermal patches, and injectables, diclofenac is valued for its versatility in managing both acute and chronic pain conditions. Topical formulations, in particular, offer a localized treatment option with reduced systemic exposure and associated risks [

5]. Despite its effectiveness, diclofenac use is associated with potential adverse effects, especially with long-term or high-dose use. These include gastrointestinal toxicity, cardiovascular risks, and renal impairment, necessitating careful consideration of patient-specific factors and appropriate dosing [

6].

Recent studies also highlight the potential of diclofenac in managing other conditions such as postoperative pain and dysmenorrhea. Its pharmacokinetic properties and relatively rapid onset of action contribute to its widespread use as a first-line treatment in various clinical scenarios [

7].

Heparin and diclofenac play distinct yet important roles in the management of pain, particularly in specific conditions. While heparin is primarily recognized as an anticoagulant, emerging research highlights its anti-inflammatory properties that may contribute to alleviating pain in certain inflammatory or thromboembolic conditions. By inhibiting inflammatory pathways and reducing the activity of pro-inflammatory mediators, heparin has shown potential in managing pain associated with conditions like chronic venous insufficiency or ischemic disorders where inflammation and clot formation exacerbate discomfort [

3].

On the other hand, diclofenac is a cornerstone in the pharmacological management of pain and inflammation. As a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), it is highly effective in treating pain linked to musculoskeletal conditions such as arthritis, soft tissue injuries, and postoperative recovery. Diclofenac reduces pain by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes, thereby decreasing prostaglandin synthesis, which mediates pain and inflammation [

8]. Its versatility across oral, topical, and injectable formulations allows tailored approaches to pain relief, with topical applications providing effective localized pain management while minimizing systemic side effects [

9,

10].

Although both agents operate via distinct mechanisms, their overlapping roles in reducing inflammation illustrate the multifaceted approaches available for managing pain. Careful consideration of the underlying condition and patient-specific factors is essential to optimize treatment with either heparin or diclofenac.

Molecular docking is a computational technique used to predict the preferred orientation of one molecule (usually a small ligand) when it binds to a specific target molecule (often a protein or nucleic acid) to form a stable complex. This technique plays a critical role in drug discovery and structural biology, as it allows researchers to understand molecular interactions at the atomic level and identify potential therapeutic compounds efficiently.

The process of molecular docking involves two main components: the docking algorithm and the scoring function. The docking algorithm explores the possible conformations and orientations of the ligand within the binding site of the target molecule. Meanwhile, the scoring function evaluates the strength and stability of the interactions, typically by considering factors such as binding energy, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and steric complementarity [

11].

Molecular docking serves various applications, including virtual screening of large compound libraries, optimization of drug candidates, and elucidation of biochemical mechanisms. Advances in computational power and software development have made molecular docking an indispensable tool in modern drug design, enabling researchers to accelerate the identification of lead compounds while reducing the need for expensive and time-consuming experimental methods [

12].

Despite its advantages, molecular docking is not without limitations. The accuracy of docking predictions depends on factors such as the quality of the target structure, the flexibility of both the ligand and receptor, and the choice of the scoring function. Continuous advancements in algorithms and machine learning are addressing these challenges, improving the reliability of docking studies.

2. Results and Discussion

The initial phase of our study utilized the HyperChem program to conduct molecular modeling of compounds heparin and diclofenac. Following this, Hex 8.0.0 software was employed to assemble these compounds into complexes. In the docking simulations, one compound was designated as the ligand, while the other acted as the receptor. The primary objective of this analysis was to evaluate whether the binding sequence of these two compounds within the complex affected the results (see

Table 2).

The docking results presented in

Table 2 reveal the binding energies of the diclofenac-heparin and heparin-diclofenac complexes, highlighting the influence of the ligand-receptor designation on binding interactions. The energy values, expressed in negative terms, represent the strength of the binding affinity, with lower values indicating stronger interactions.

When diclofenac was designated as the ligand and heparin as the receptor, the binding energy was calculated as -140.56. Conversely, when the roles were reversed - heparin as the ligand and diclofenac as the receptor - the energy was slightly lower at -146.73, indicating a stronger binding affinity. This difference suggests that the orientation and specific interactions between the two molecules depend on their assigned roles during the docking process.

The stronger interaction in the heparin-as-ligand scenario could be attributed to its larger and more flexible structure compared to diclofenac. Heparin, being a polysaccharide, may have more opportunities for favorable interactions such as hydrogen, ionic, or van der Waals interactions when actively searching for binding sites on diclofenac. On the other hand, smaller and relatively rigid structure of diclofenac may limit its ability to fully optimize interactions when designated as the ligand.

This observation underscores the importance of exploring different ligand-receptor configurations in molecular docking studies to ensure a comprehensive understanding of binding interactions. Such differences in binding energy can guide the design of experiments or therapeutic strategies, particularly when considering the implications of ligand-receptor orientation in drug-receptor dynamics. Further analysis, including the examination of specific interaction sites and the contribution of hydrophobic and electrostatic forces, could provide deeper insights into the binding mechanisms.

A key factor in understanding these interactions is lipophilicity, typically expressed as the logarithm of the partition coefficient (logP), which measures the affinity of a compound for lipid (or octanol) phases compared to water [

14]. LogP values are crucial for predicting solubility, permeability, and overall bioavailability of a molecule. In this study, we evaluate values of logP to examine their influence on the interactions within the diclofenac-heparin complexes.

Table 3 presents the calculated logP values for the diclofenac-heparin and heparin-diclofenac complexes, providing insight into the lipophilicity of these systems and its potential impact on their behavior in biological environments. The logP value reflects the preference of a compound or complex for lipid phases over aqueous phases, with higher values indicating greater lipophilicity.

In the heparin-diclofenac complex, the value of logP is 4.04, slightly higher than 3.76 observed for the diclofenac-heparin complex. This difference suggests that the orientation and role of each molecule in the complex influence the overall hydrophobicity. The higher logP value for the heparin-diclofenac configuration indicates that this arrangement is more lipophilic, which could enhance its interaction with lipid membranes or hydrophobic environments. This increased lipophilicity might be due to the alignment or exposure of more hydrophobic regions of the molecules in this particular orientation.

In contrast, the diclofenac-heparin complex exhibits a lower logP value, implying it is slightly more hydrophilic than the reverse configuration. This could reflect differences in the exposure of polar functional groups or variations in the overall packing and interaction between the molecules when diclofenac acts as the ligand.

These findings highlight the importance of lipophilicity in determining the behavior of molecular complexes. A more lipophilic configuration might enhance membrane permeability and retention in lipid-rich environments, while a more hydrophilic orientation could favor interactions in aqueous media. Such differences can have implications for drug delivery and bioavailability, emphasizing the need to consider lipophilicity when designing and evaluating drug-receptor complexes [

16]. Further experimental validation and analysis of specific interaction sites could clarify the role of these logP differences in biological settings.

In the next phase of our study, we present the results of molecular docking simulations involving our complexes and the Protein Data Bank (PDB) receptors 3N8V (COX-1) and 5W58 (COX-2). Cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes are pivotal in pain management, as they mediate the production of prostaglandins involved in inflammation and pain. By incorporating structural data, this analysis aims to reveal how our complexes interact with these enzymes, providing insights into the three-dimensional nature of these interactions and their potential pharmacological relevance [

17].

The data in

Table 4 present the binding energies of various configurations involving heparin and diclofenac, either as individual compounds or as complexes. The complex heparin_diclofenac shows the most favorable binding energy at -358.06 kcal/mol, significantly lower than the energies observed for heparin alone (-309.55 kcal/mol) and diclofenac alone (-305.47 kcal/mol). This indicates that when heparin and diclofenac are combined in this specific complex, they form a stable interaction with enhanced binding affinity compared to either compound taken alone.

In contrast, the alternative complex configuration, diclofenac_heparin, exhibits a much higher binding energy of -63.7 kcal/mol, suggesting a far weaker interaction. This discrepancy between the two complexes indicates that the sequence in which heparin and diclofenac bind is critical to their overall stability. The heparin_diclofenac complex, where heparin likely acts as the receptor and diclofenac as the ligand, appears to enable stronger interactions, possibly due to optimal alignment of hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions.

The marked difference in binding energies between the two complexes underscores the significance of binding orientation and order. The high stability configuration of the heparin_diclofenac complex may enhance the pharmacological potential of this complex, as stronger binding can often correlate with better target specificity and bioactivity [

18]. These findings could provide a basis for future studies exploring the structural basis of binding preferences and optimizing the sequence of binding for improved therapeutic efficacy. Further structural analyses, such as molecular dynamics simulations, may help clarify the interaction mechanisms and identify the specific molecular interactions responsible for this increased stability.

The docking results presented in

Table 5 display the binding energies of different configurations involving diclofenac, heparin, and their complexes with COX-2 enzyme. The complex diclofenac_heparin exhibits the lowest binding energy at -468.48 kcal/mol, indicating the most stable interaction with COX-2. This high stability suggests that, when diclofenac acts as the ligand binding to heparin within the complex, the resulting structure has an enhanced affinity for COX-2 active site.

The alternative complex, heparin_diclofenac, shows a slightly higher binding energy of -434.59 kcal/mol. Although still a stable interaction, it is weaker compared to the diclofenac_heparin configuration, implying that the order in which these compounds bind affects the strength of the interaction with COX-2. The binding energies of the individual compounds, with diclofenac at -332.81 kcal/mol and heparin at -285.75 kcal/mol, are notably higher, indicating less stable interactions with COX-2 compared to the complexes. This suggests that the formation of a complex between diclofenac and heparin significantly enhances their collective binding affinity for COX-2, likely due to combined molecular interactions that are not achievable by either compound alone.

The results underscore the importance of binding orientation and sequence in complex formation, as it directly impacts binding strength with COX-2. The stronger binding affinity observed in the diclofenac_heparină complex may translate to improved inhibitory effects on COX-2, which could be advantageous in therapeutic contexts where COX-2 inhibition is desired. These findings suggest potential benefits in exploring diclofenac-heparin combinations for enhanced COX-2 targeting [

19]. Further studies, such as molecular dynamics simulations or experimental validation, could help clarify the specific interactions that contribute to this stability and optimize the design of diclofenac-heparin-based complexes for COX-2 inhibition.

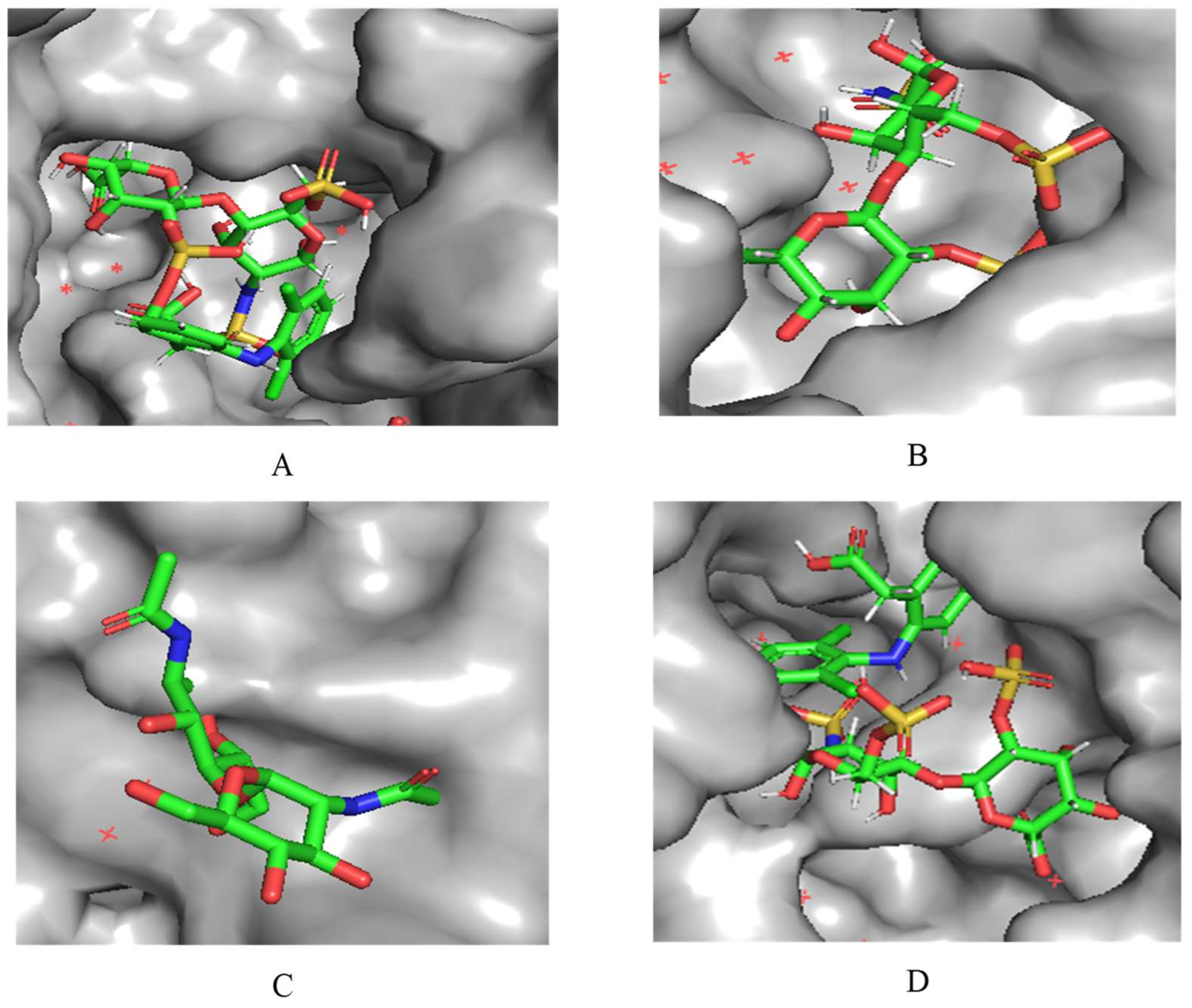

A notable observation from the docking images is that the heparin-diclofenac and diclofenac-heparin complexes bind at a site distinct from the binding sites of the individual drugs, heparin and diclofenac (

Figure 1). This difference in binding location may reflect altered spatial and chemical properties of the complexes compared to the individual molecules.

Furthermore, the docking results suggest that the strength of binding varies between the two complexes. Specifically, the diclofenac-heparin complex appears to exhibit weaker binding compared to the heparin-diclofenac complex, as indicated by the binding energy calculations. This disparity could be attributed to differences in the orientation and accessibility of key functional groups within each complex, which influence their interactions with COX-1 receptor. For instance, the heparin-diclofenac complex may align more favorably, allowing for stronger interactions with amino acid residues of the receptor, while the diclofenac-heparin complex might have a less optimal conformation.

The distinct binding sites and varying binding strengths highlight the importance of ligand-receptor orientation and molecular structure in determining the efficacy of drug-receptor interactions. These findings could have implications for designing combination therapies or conjugate drugs, as the binding behavior of complexes differs significantly from that of their constituent drugs.

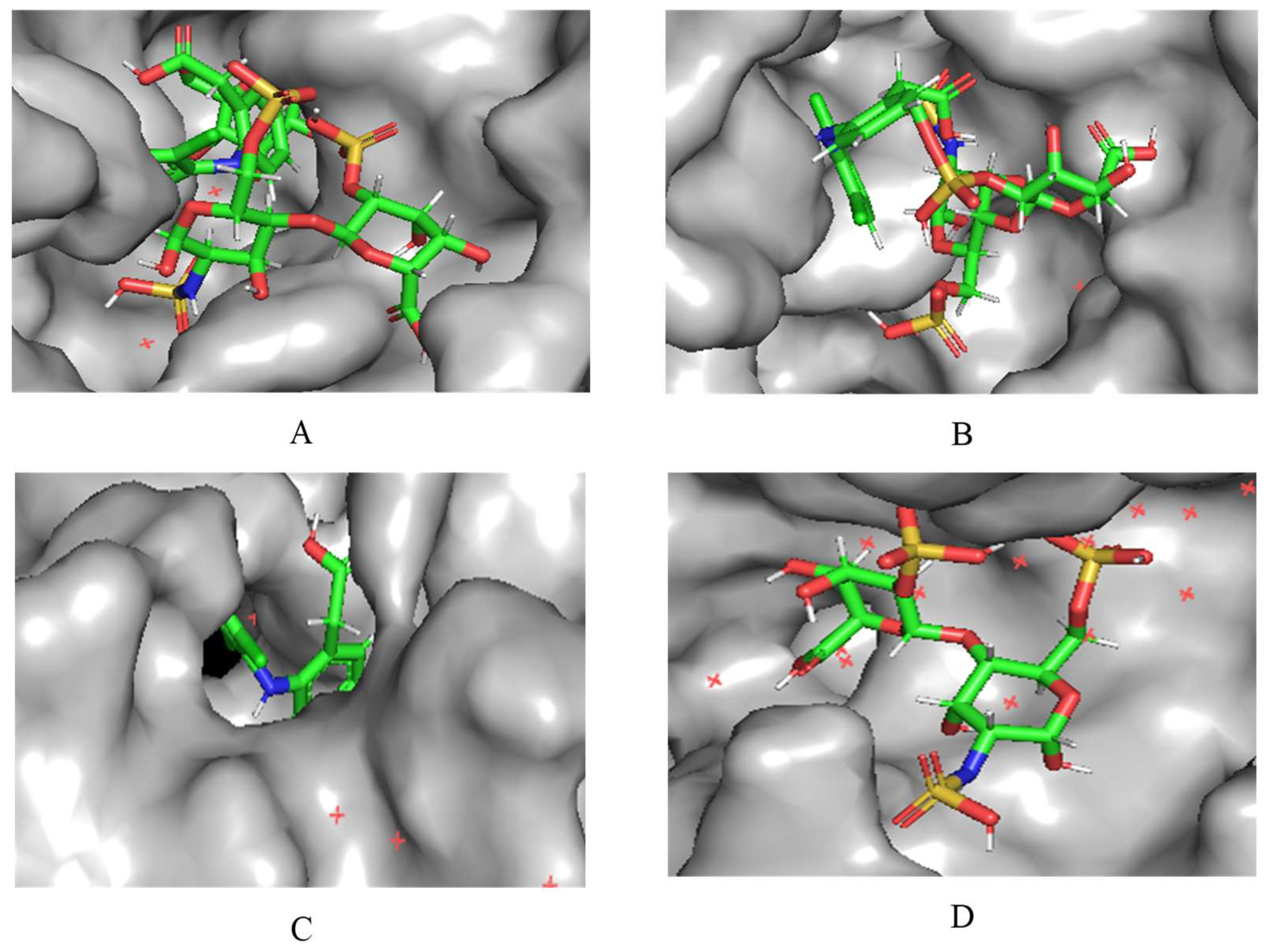

A notable finding from these docking simulations is that both complexes - heparin-diclofenac and diclofenac-heparin - exhibit stronger binding affinities to COX-2 receptor compared to the individual drugs (

Figure 2) [

21]. This enhanced binding suggests that the complexes introduce additional stabilizing interactions, such as extended hydrogen bonding networks, complementary hydrophobic interactions, or cooperative effects between functional groups of the two components.

Among the complexes, the heparin-diclofenac configuration generally demonstrates stronger binding than the diclofenac-heparin configuration, reflecting the importance of ligand orientation and the spatial arrangement of functional groups in optimizing receptor interactions. These differences could be tied to how the heparin molecule, as a larger and more flexible entity, aligns itself to maximize interactions with key residues of COX-2 receptor when serving as the ligand.

When comparing these results to those obtained for COX-1, there are clear distinctions in binding behavior. COX-1 and COX-2 share structural similarities, but their active sites have subtle differences that can influence how ligands and complexes interact [

22]. COX-2 has a slightly larger and more flexible active site, which may accommodate the bulkier heparin-diclofenac and diclofenac-heparin complexes more effectively, leading to stronger binding compared to COX-1. This structural variability could also account for differences in the binding strengths of individual drugs, such as diclofenac, between the two enzymes.

These observations underscore the potential of molecular complexes to enhance drug-receptor interactions beyond what is achievable with individual drugs. They also highlight the importance of receptor-specific dynamics in drug design [

23]. By leveraging the distinct binding site characteristics of COX-1 and COX-2, it may be possible to tailor therapies that selectively target one enzyme over the other, potentially minimizing side effects and improving therapeutic outcomes. Further investigation into the molecular details of these interactions, such as the specific residues involved and the energetic contributions of different interaction types, would provide deeper insights into the pharmacological implications of these complexes.