Submitted:

01 January 2025

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

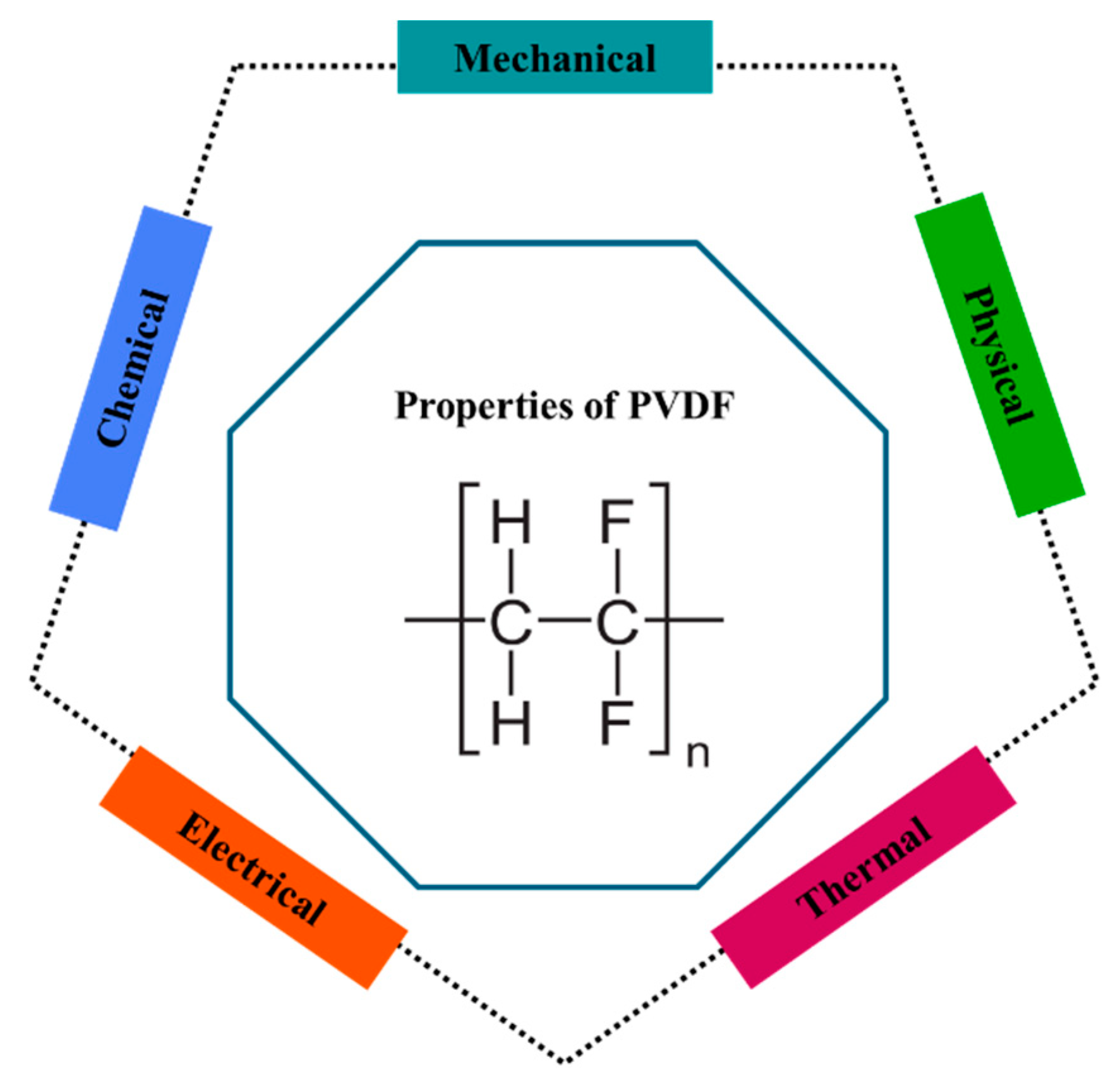

2. Materials Properties

2.1. Physical Properties

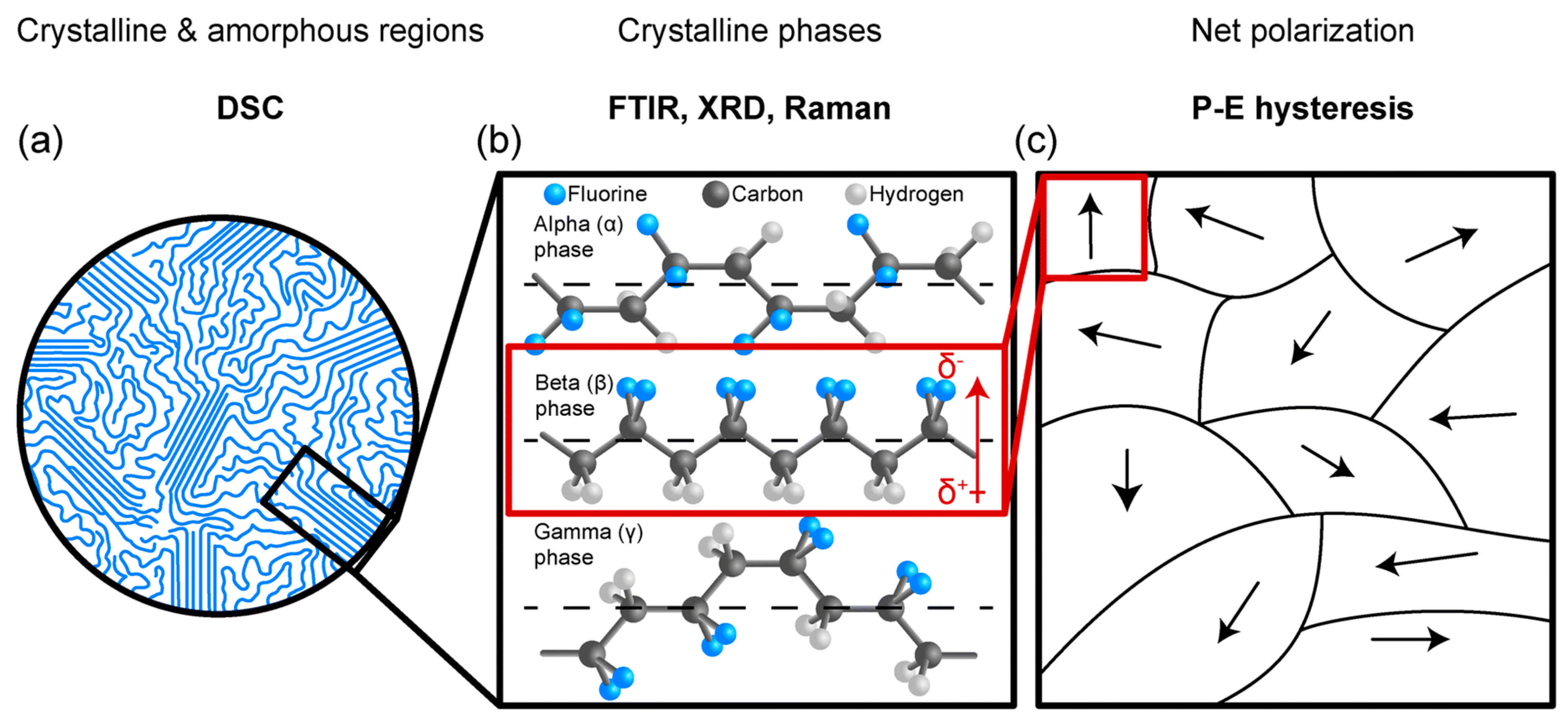

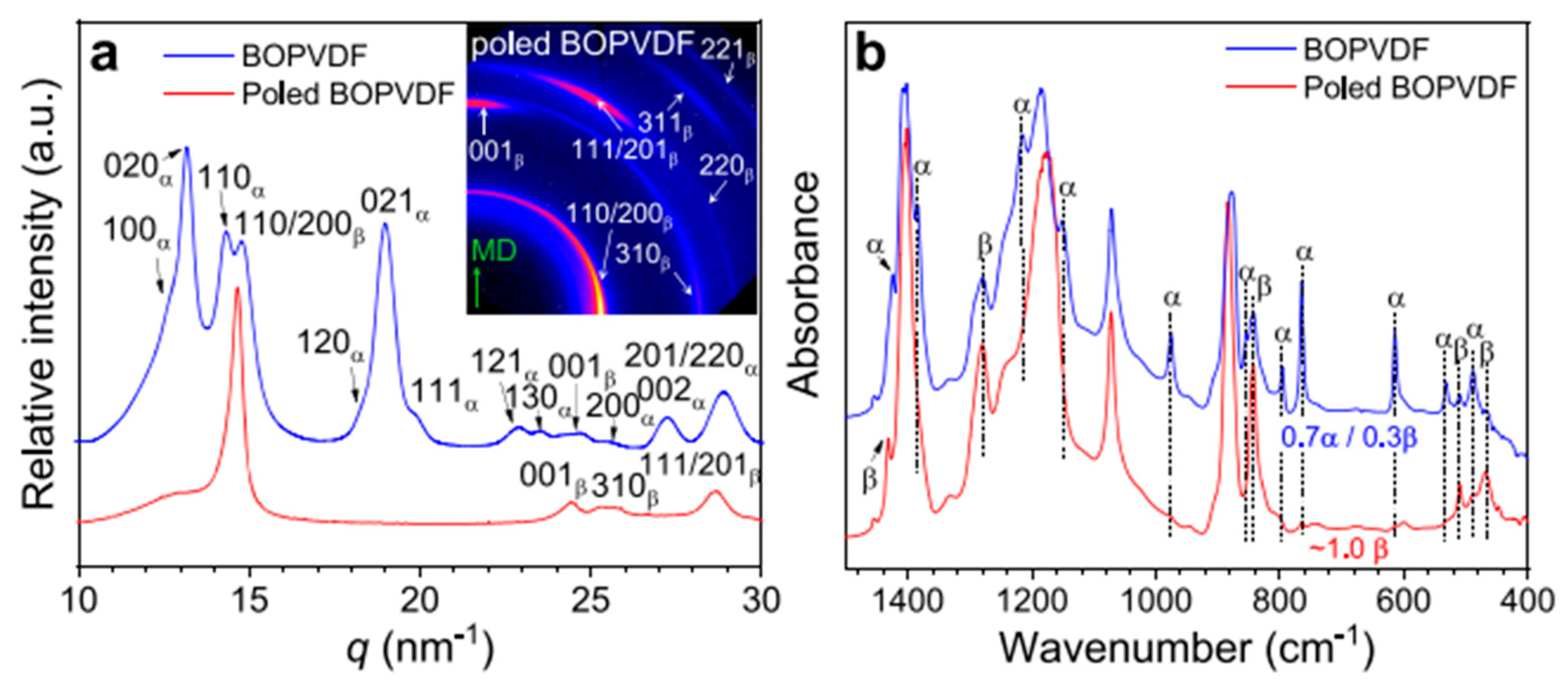

2.1.1. Crystaline Structure of PVDF

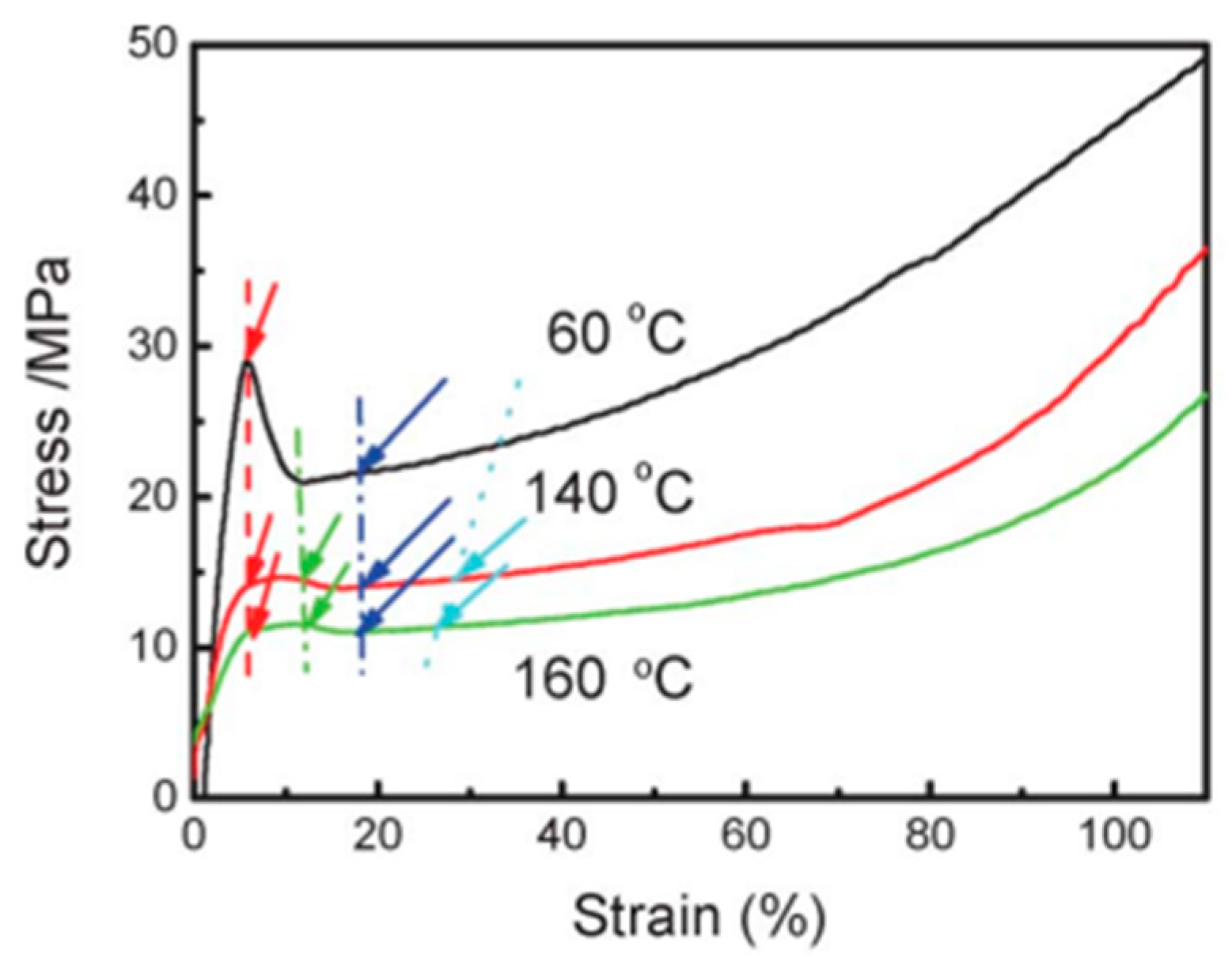

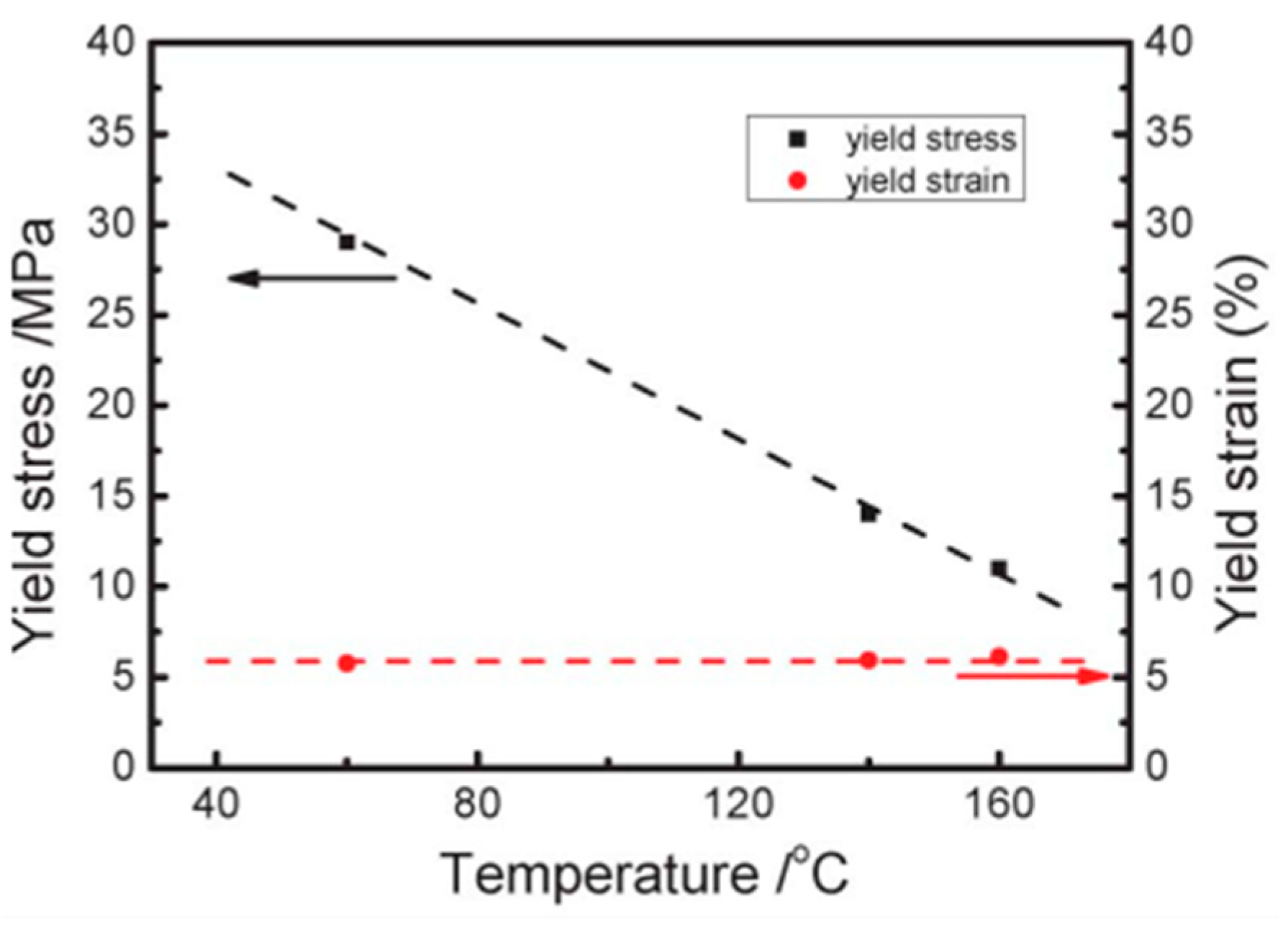

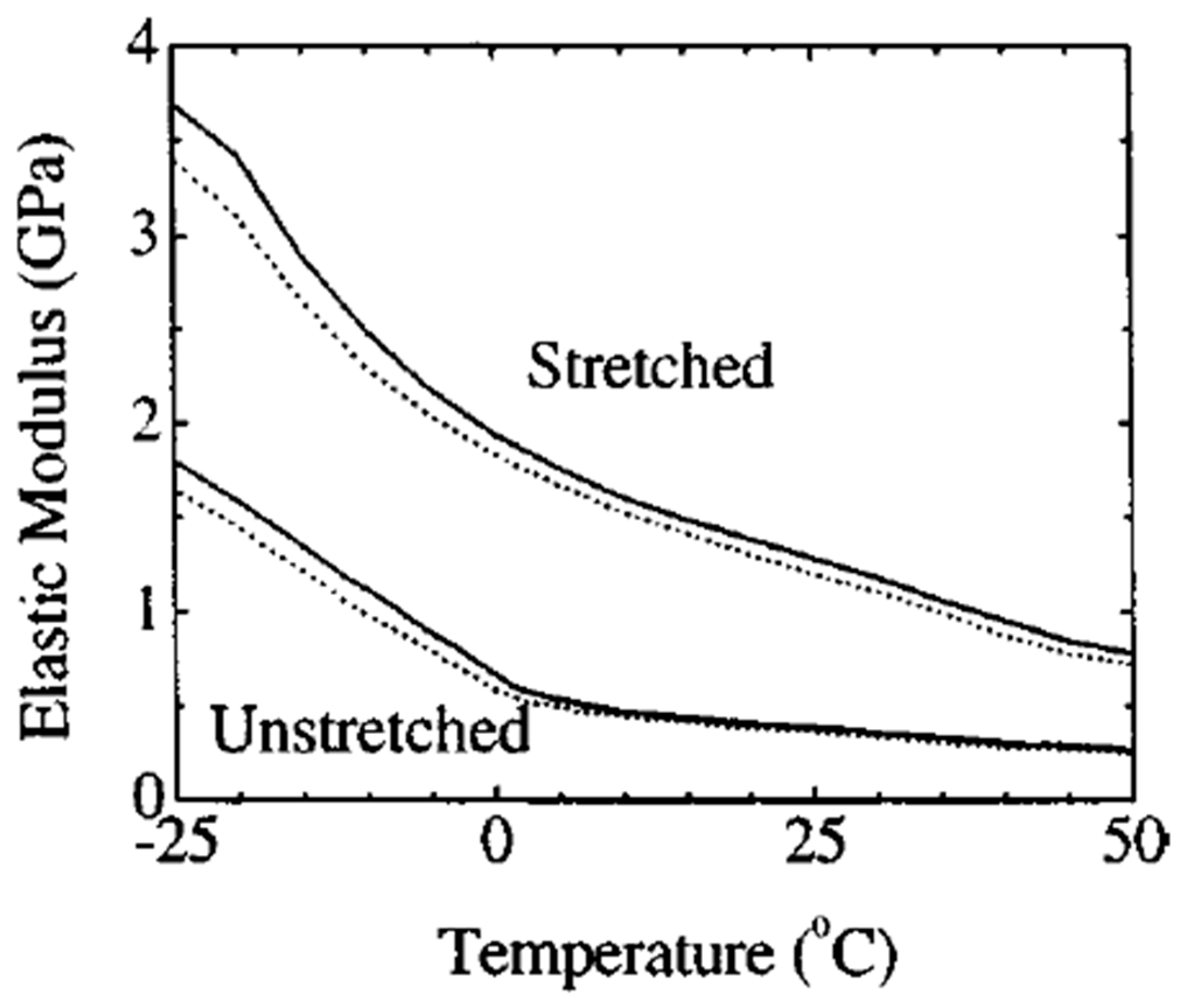

2.2. Mechanical Properties

2.3. Chemical Properties

2.4. Thermal Properties

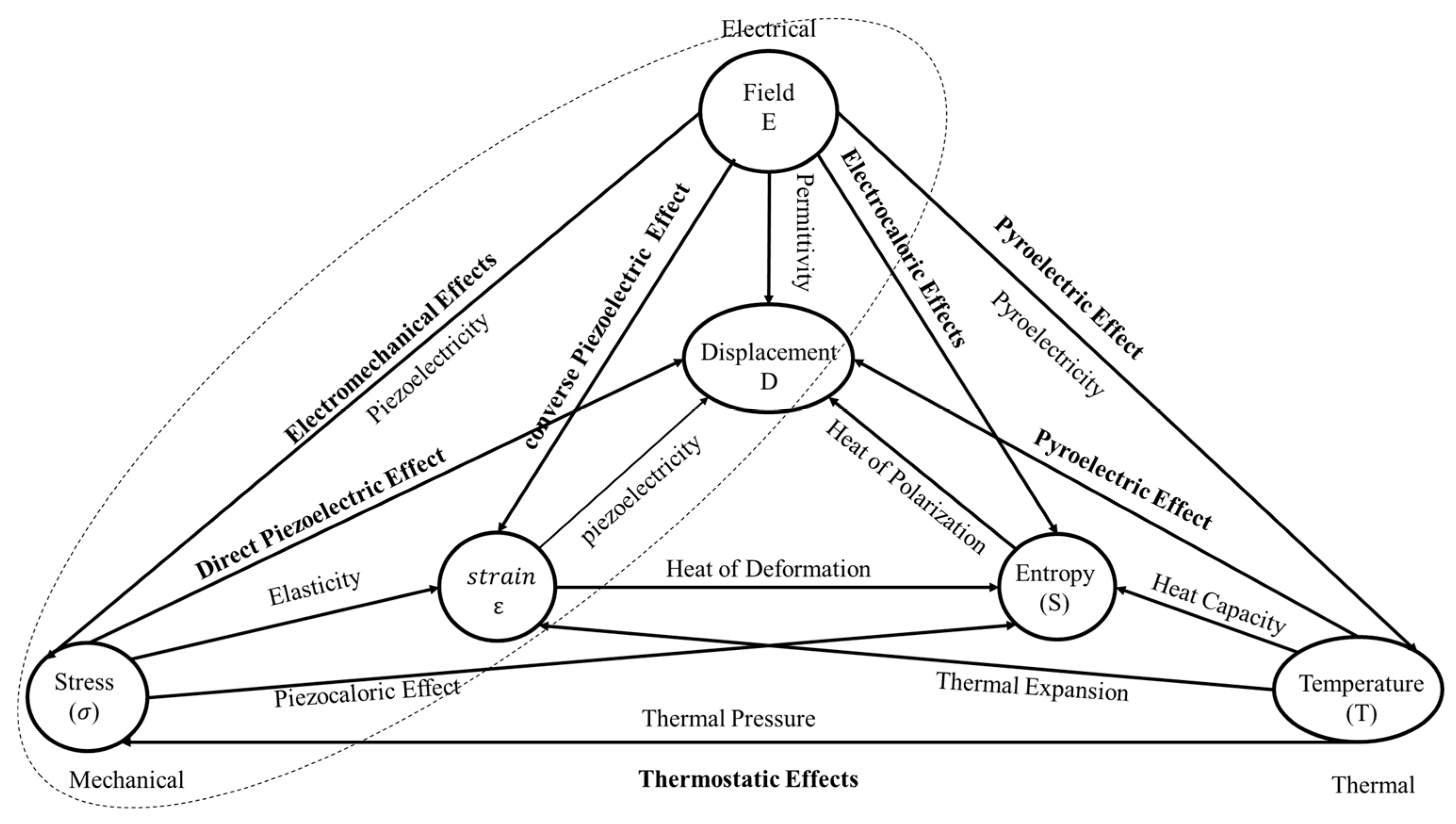

2.5. The Electroactive Properties of the PVDF

2.5.1. Ferroelectric Effect

2.5.1.1. Dielectric Properties

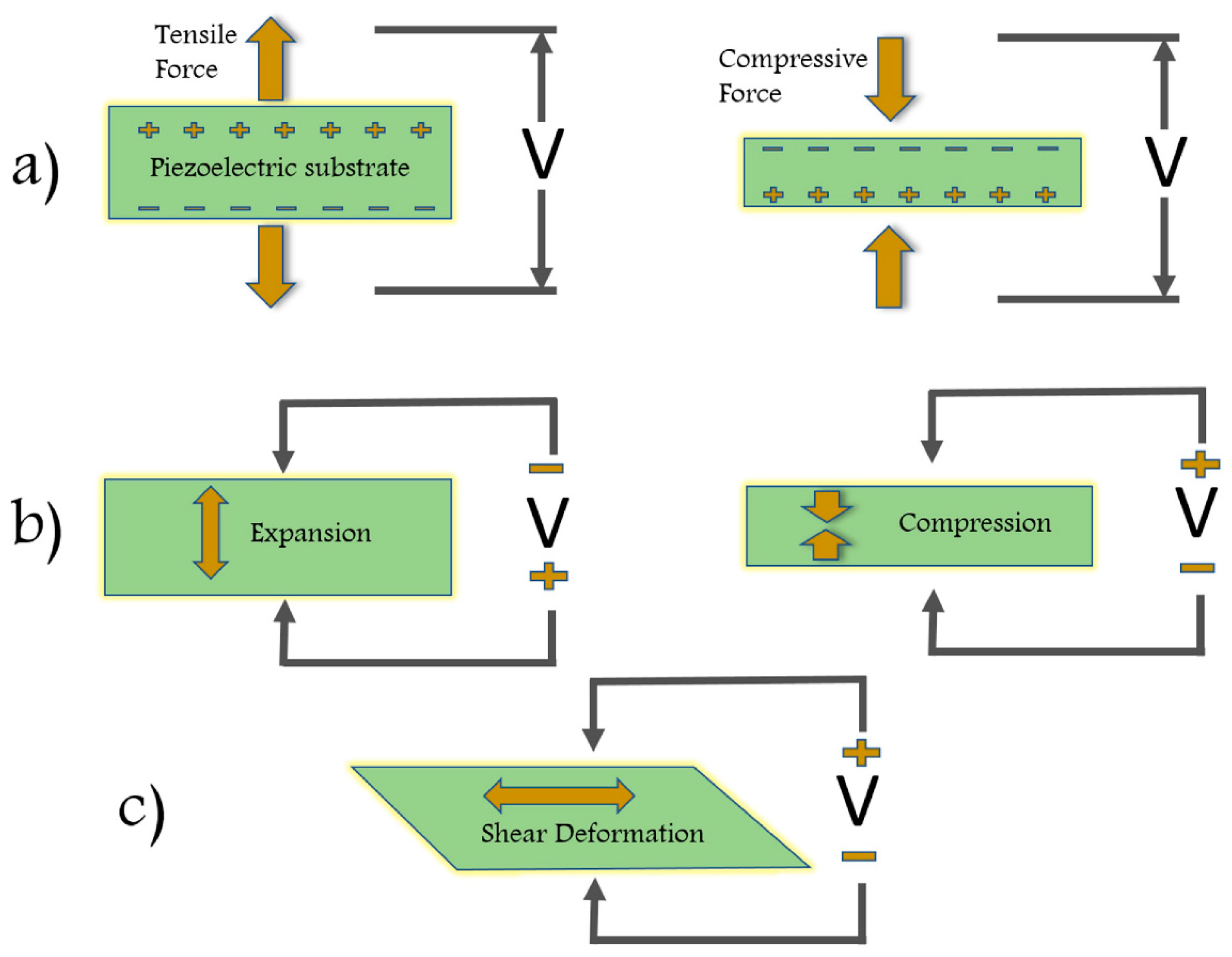

2.5.1.2. Piezoelectric EFFECT

2.5.4. Pyroelectric Effect

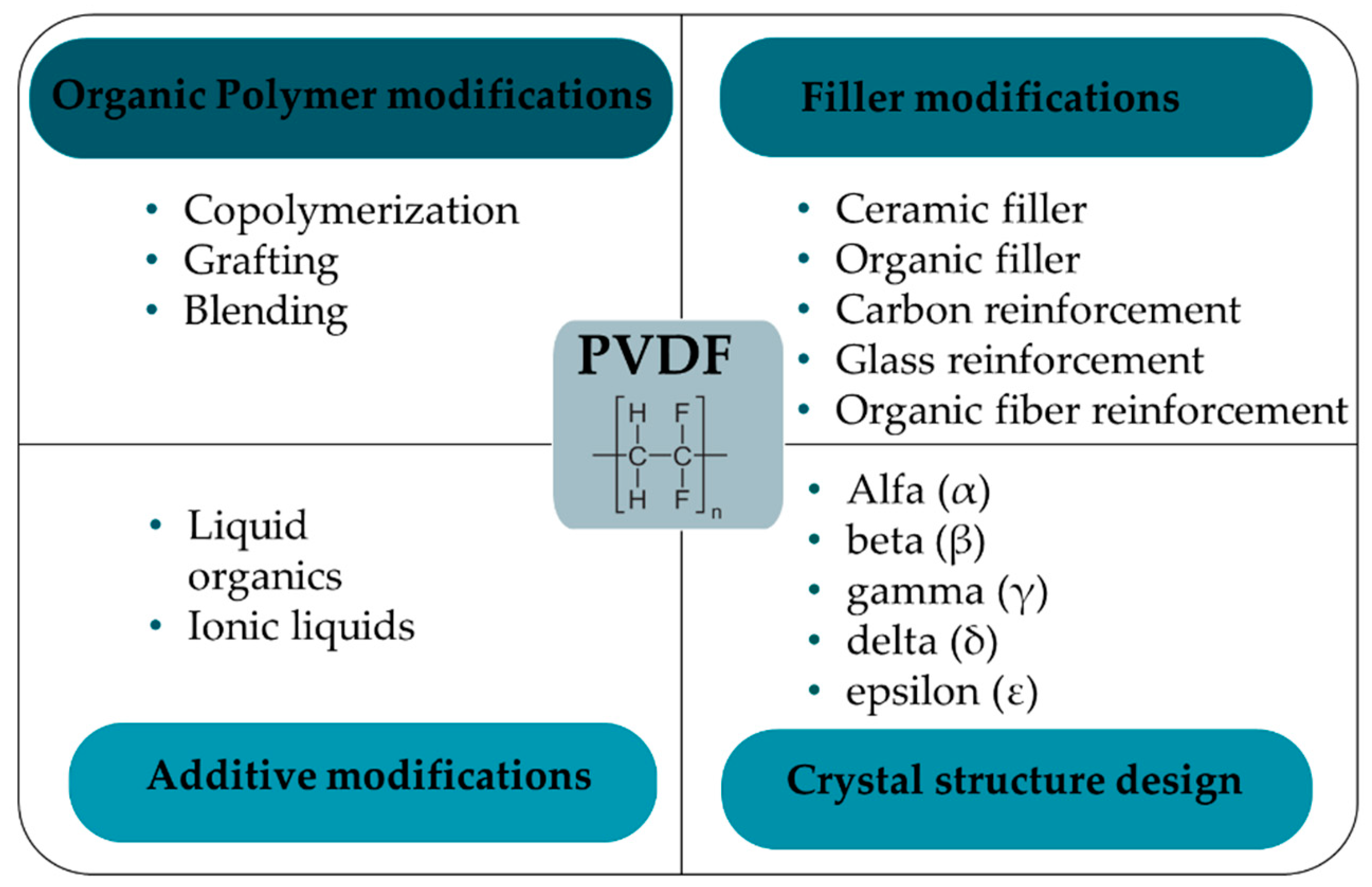

3. Enhancement of PVDF Properties Through Optimized Preparation Methods

3.1. PVDF Film Fabrication Methods

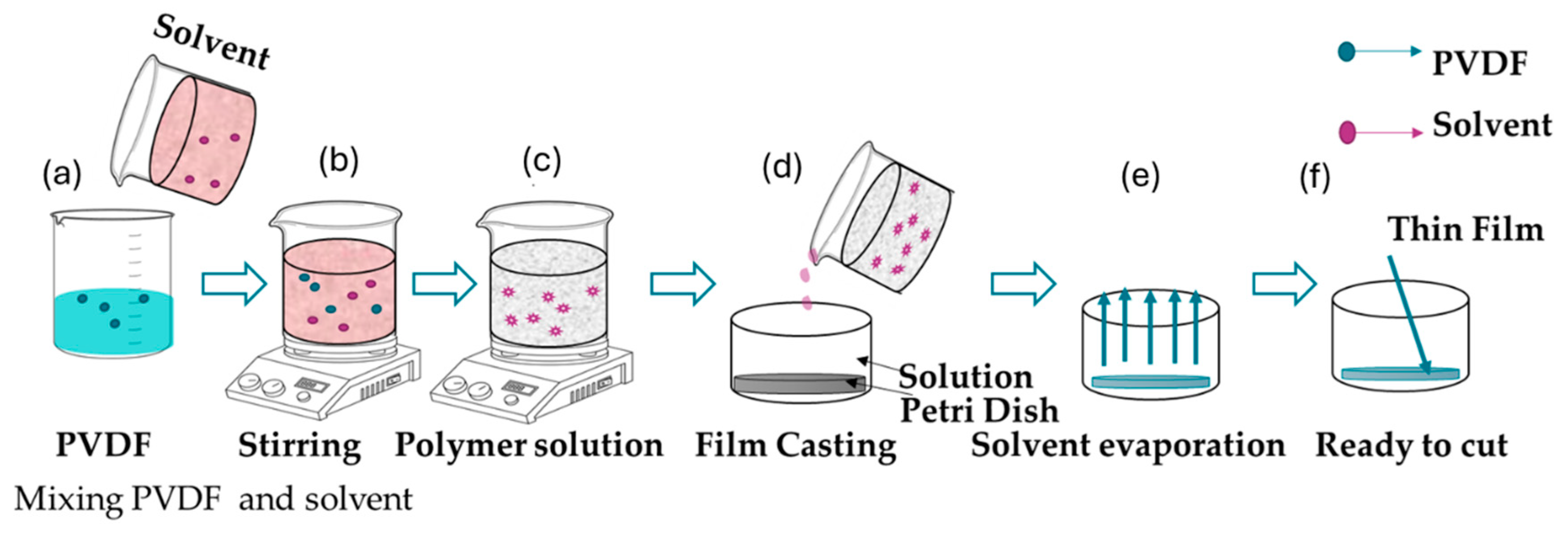

3.1.1. Solution Casting

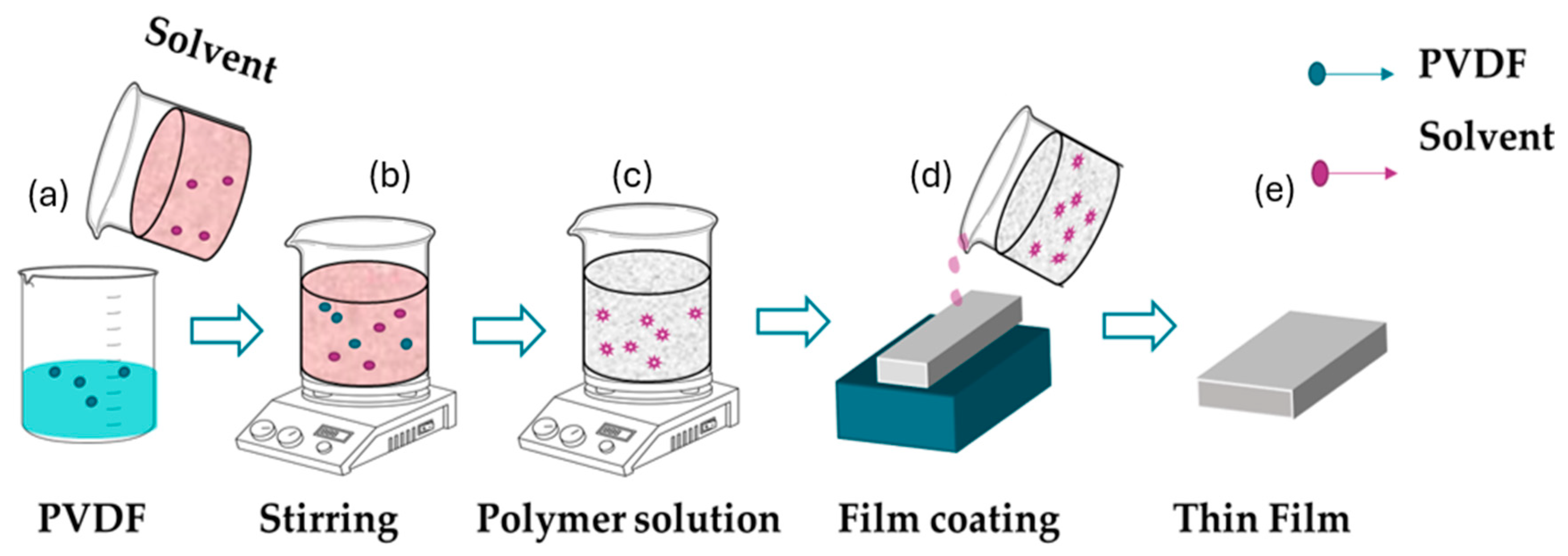

3.1.2. Solution Coating

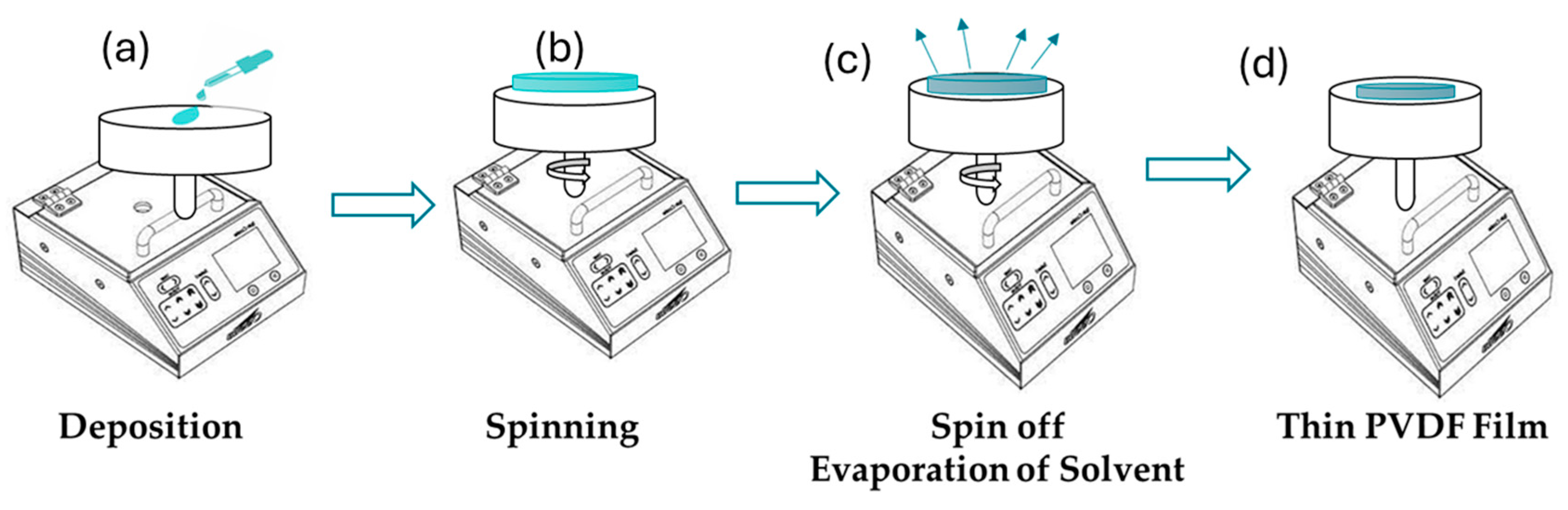

3.1.3. Spin Coating

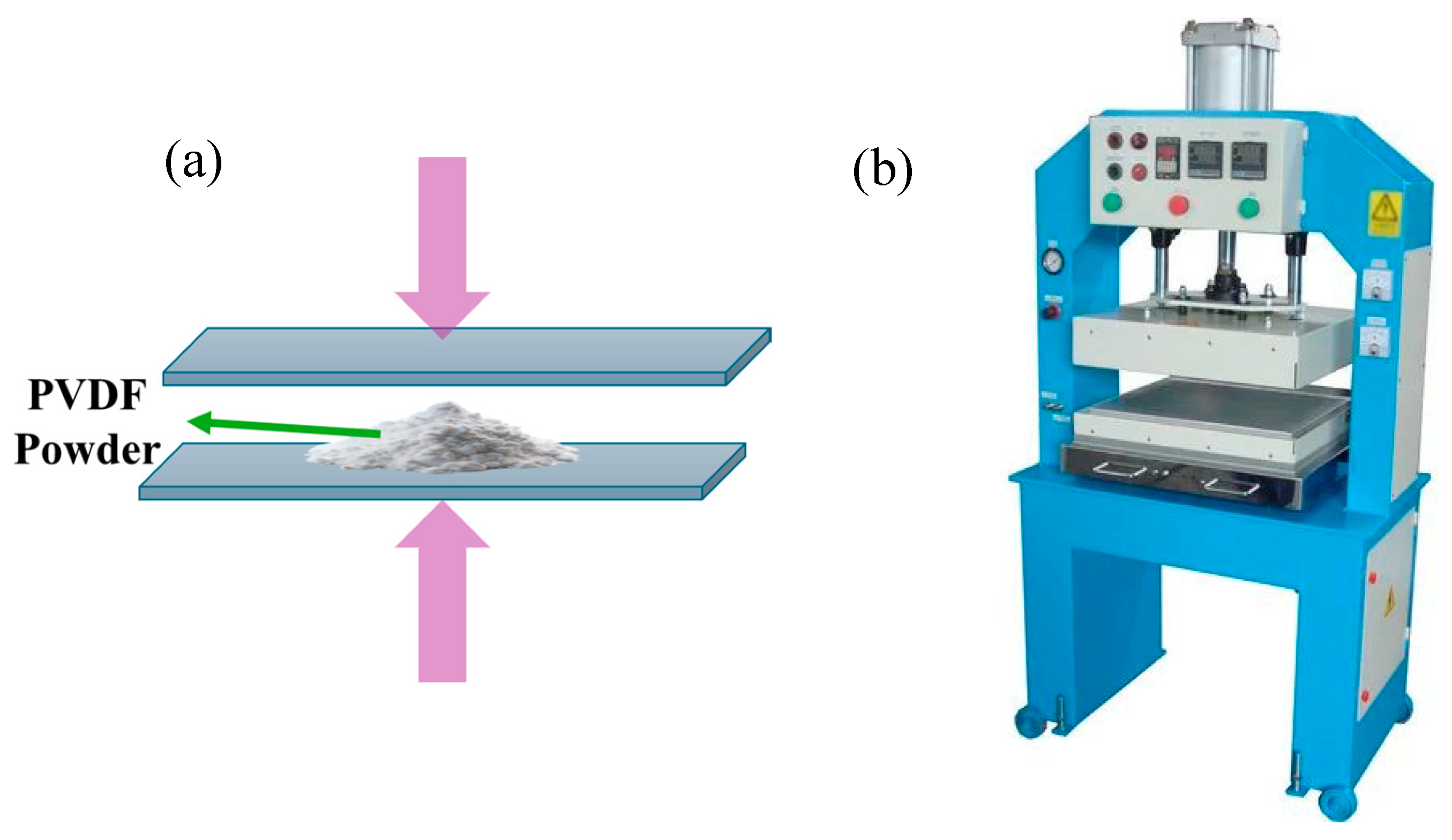

3.1.4. Hot Pressing Method

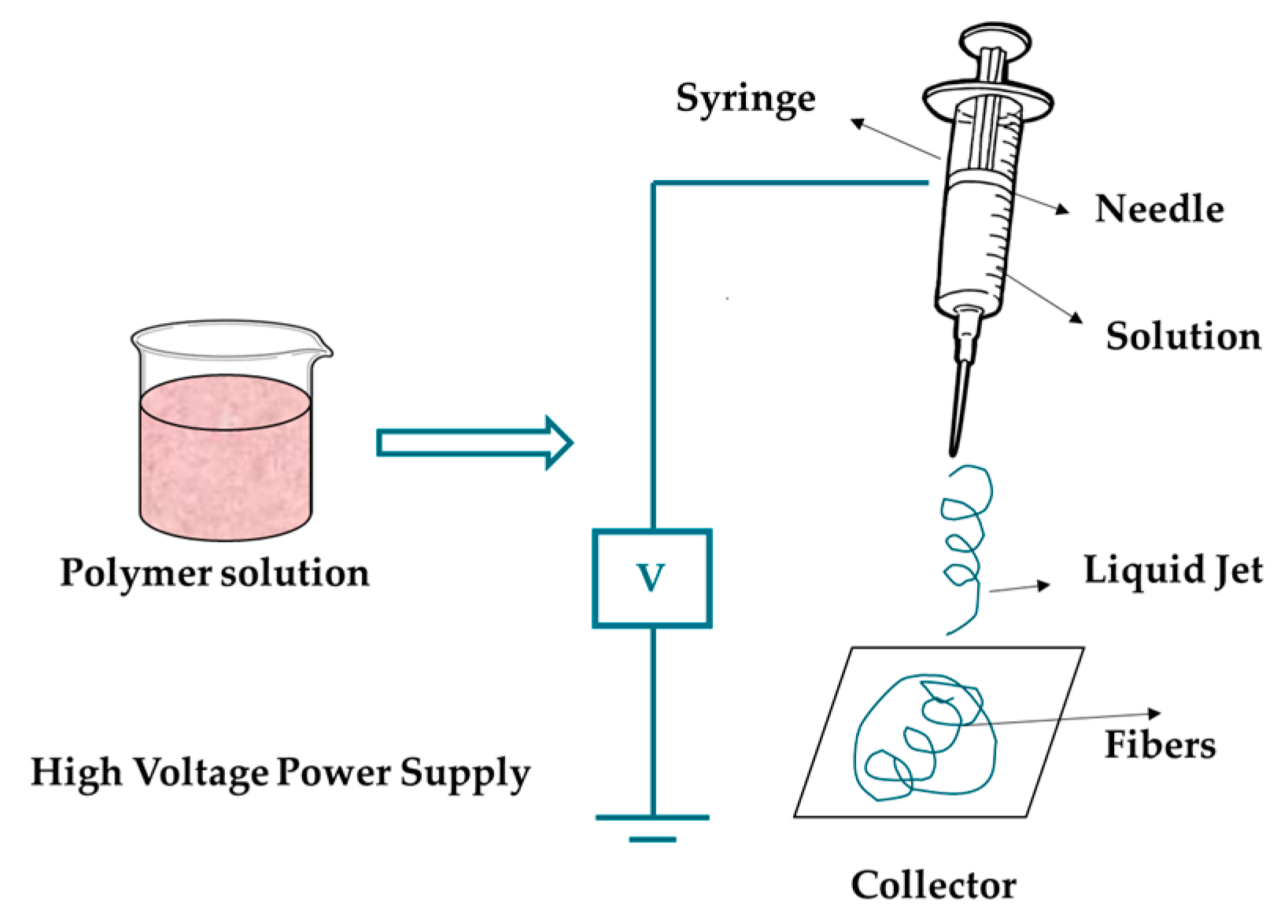

3.1.5. Electrospinning

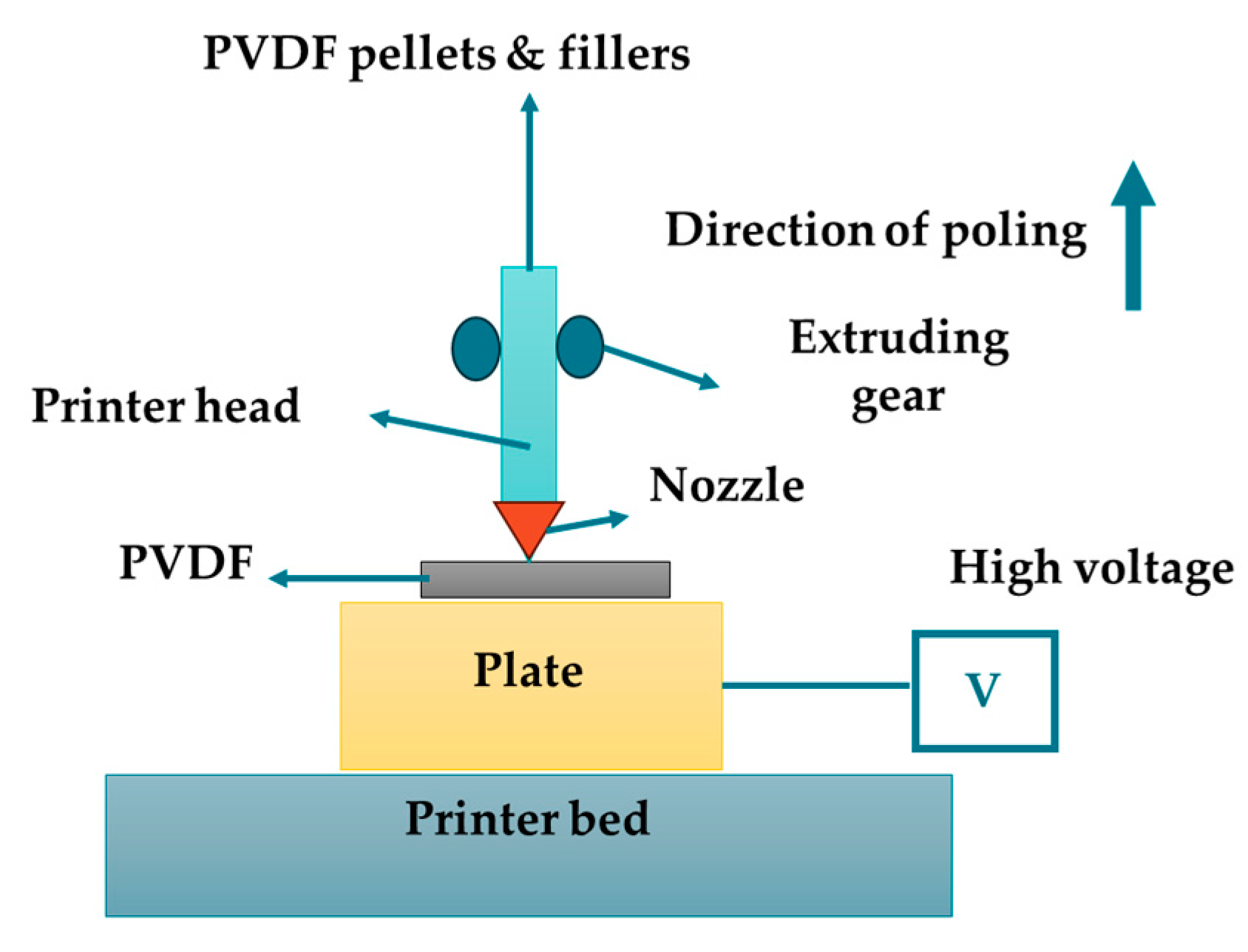

3.1.6. 3D Printing

3.2. Phase Transition and Achievement Methods

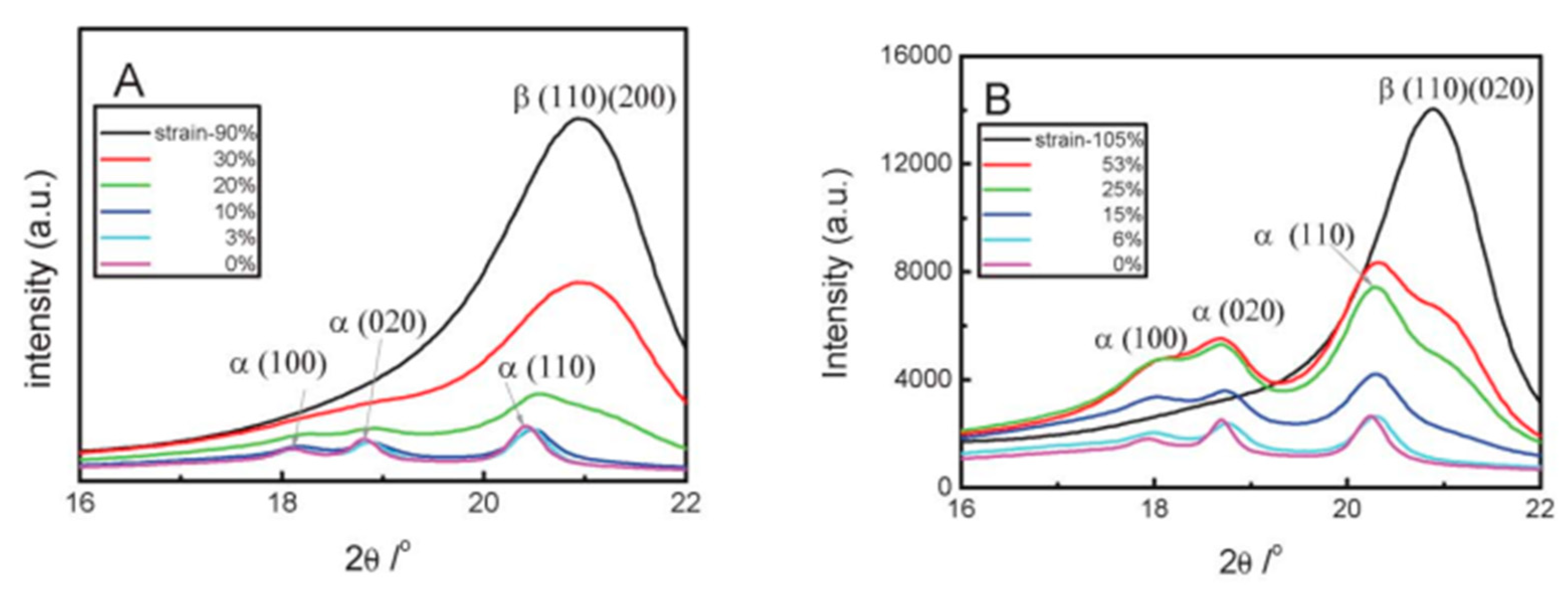

3.2.1. Stretching

3.2.2. Annealing

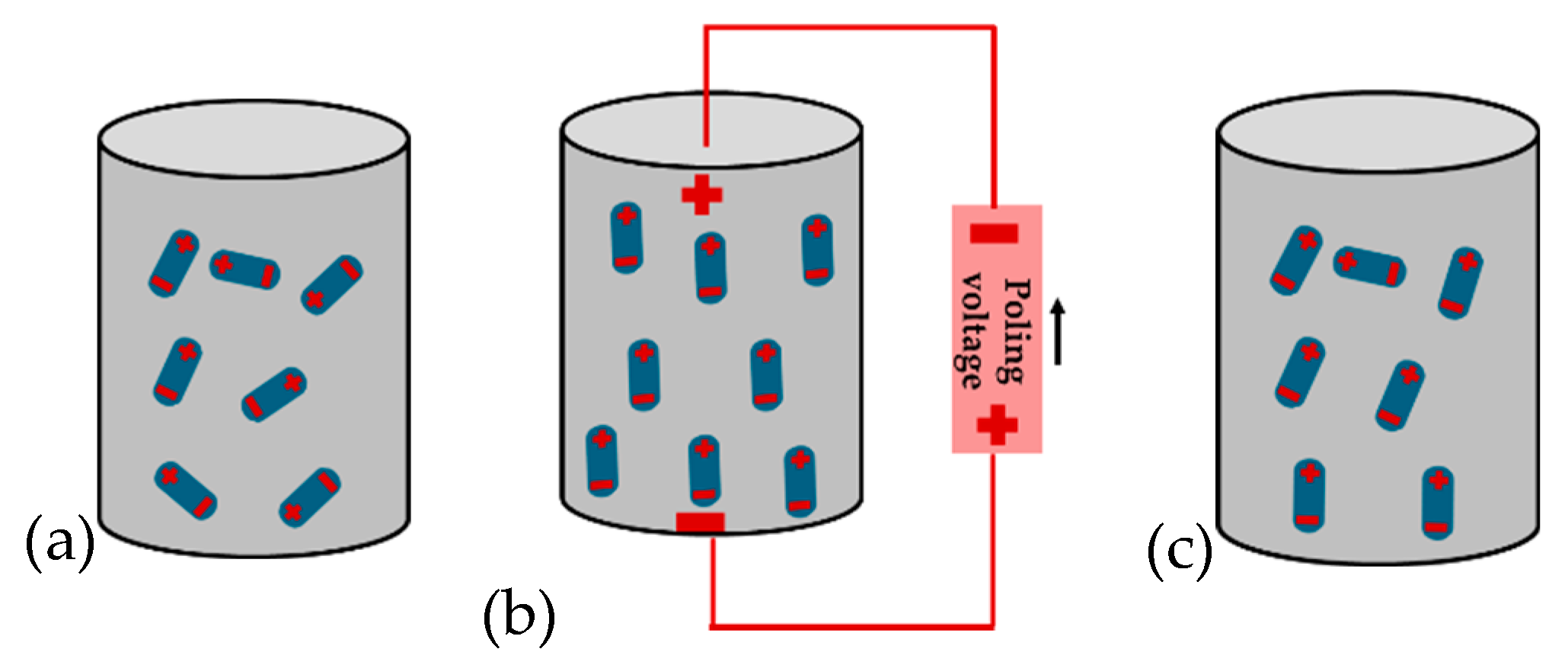

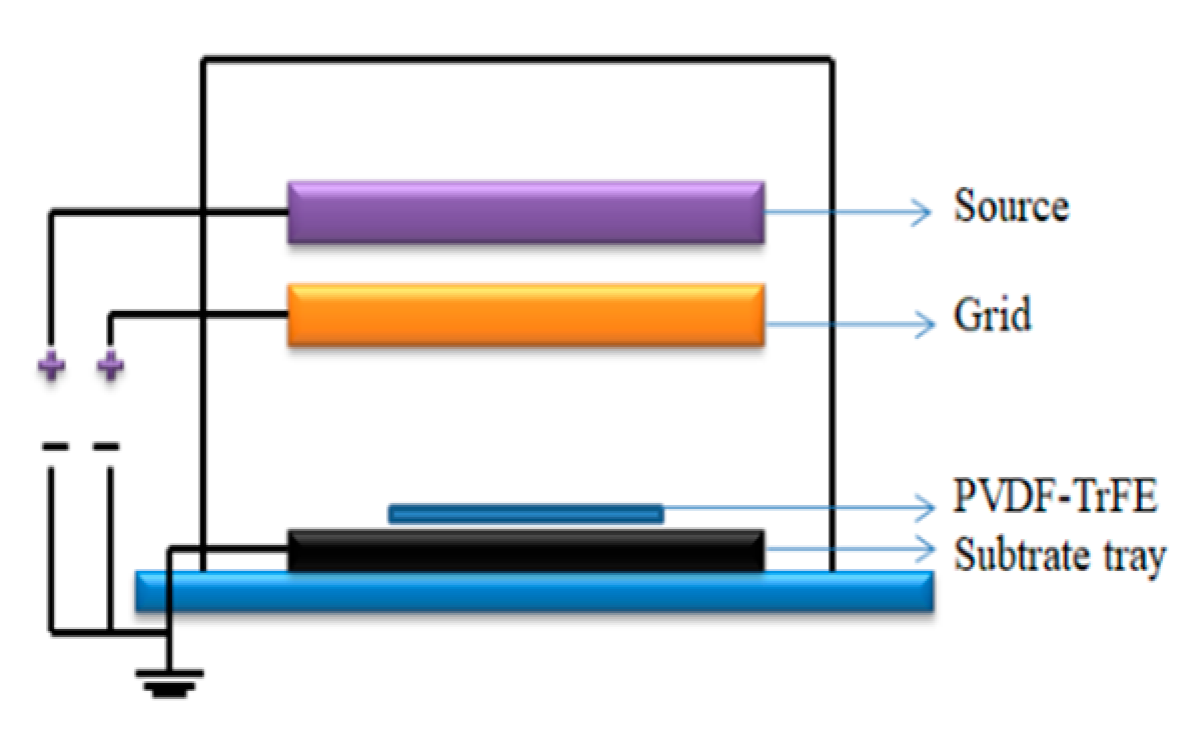

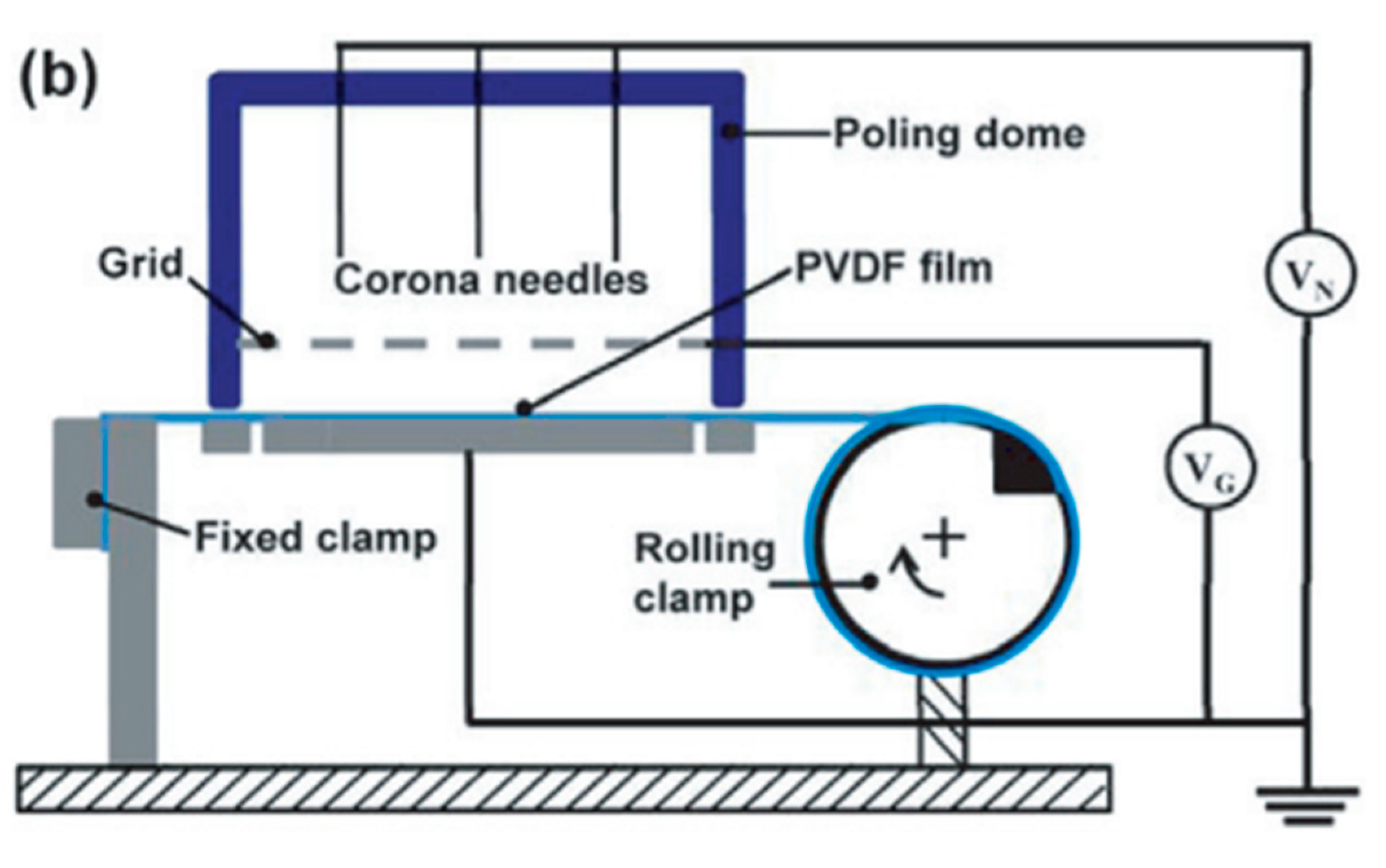

3.3. Poling

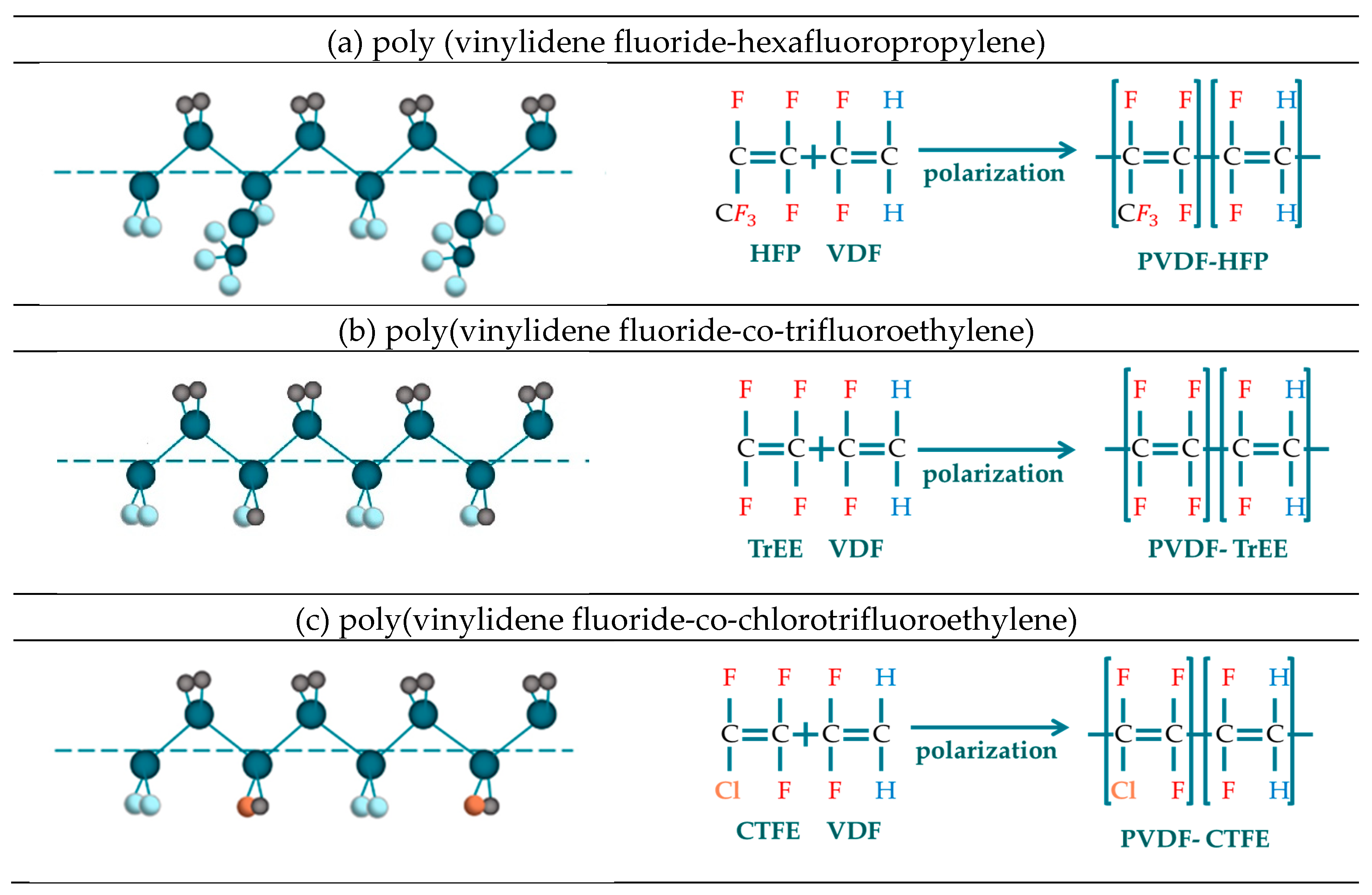

3.4. Copolymerization of PVDF

3.4.1. P(VDF-co-HFP)

3.4.2. P(VDF-co-TrFE)

3.4.3. P(VDF-co-CTFE)

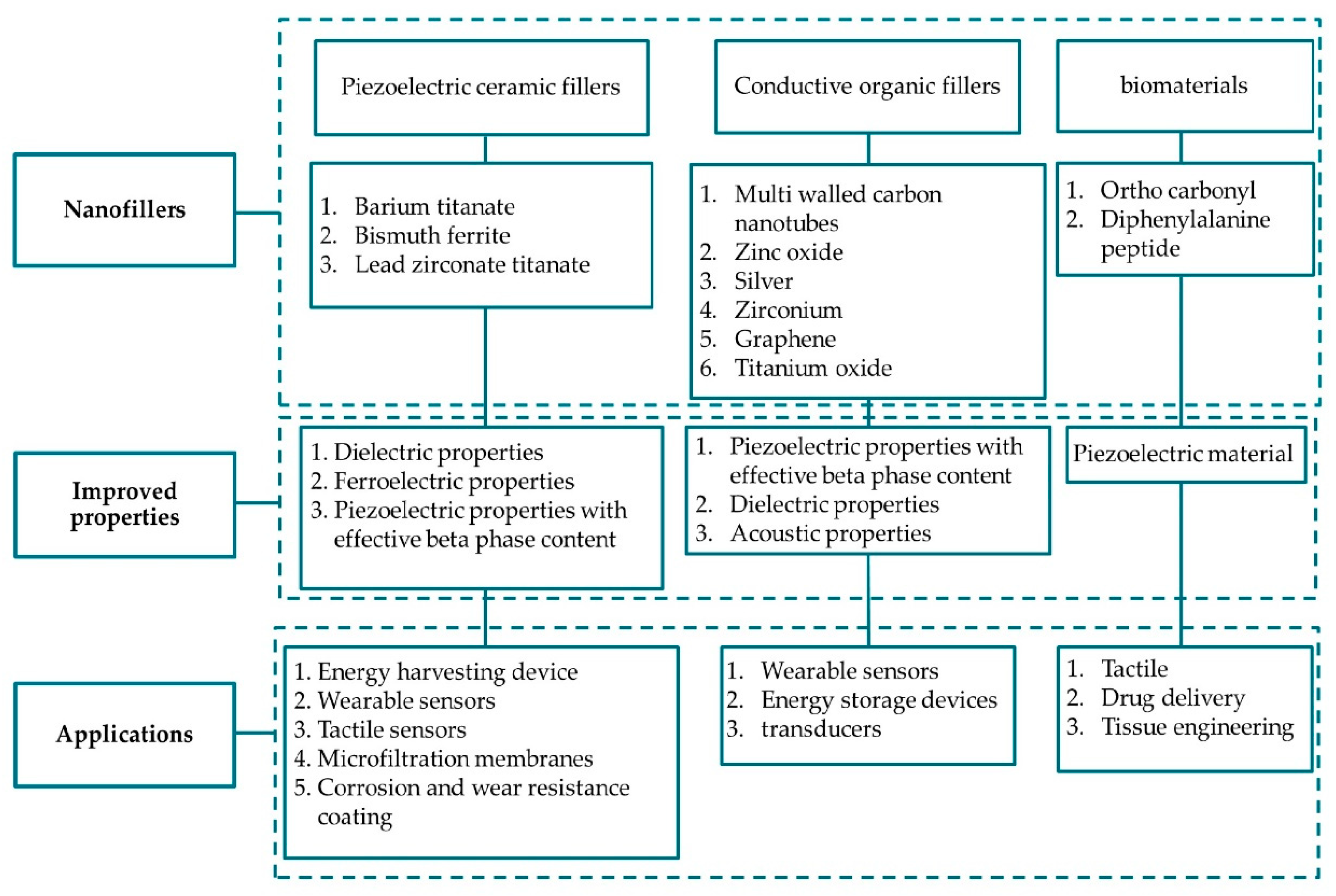

3.5. PVDF Composites

3.5.1. Fillers

3.5.2. Enhanced Piezoelectric Properties by PVDF Blend with Polymers.

4. Material Property Characterizations and Techniques

4.1. Thermal Characterization

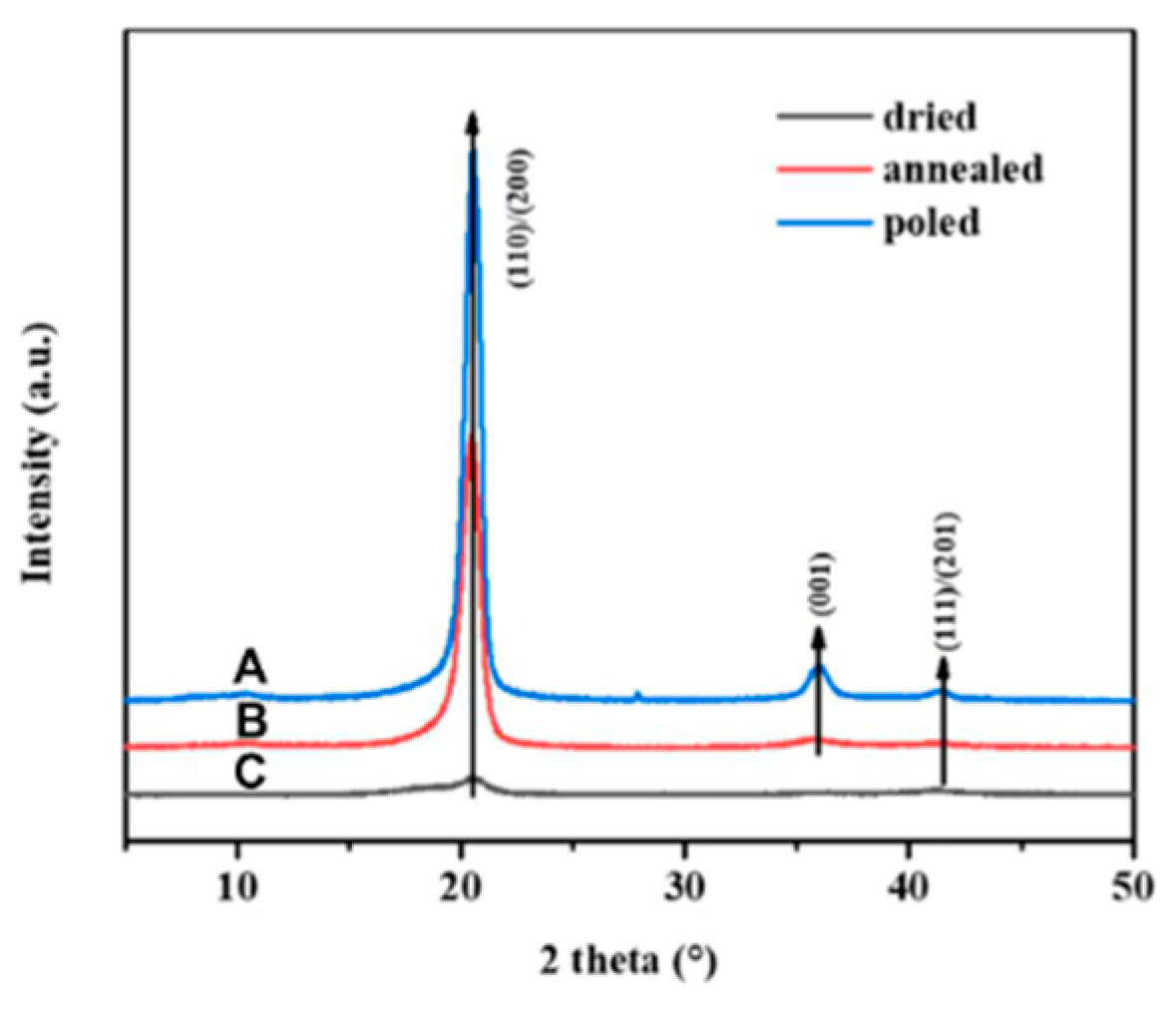

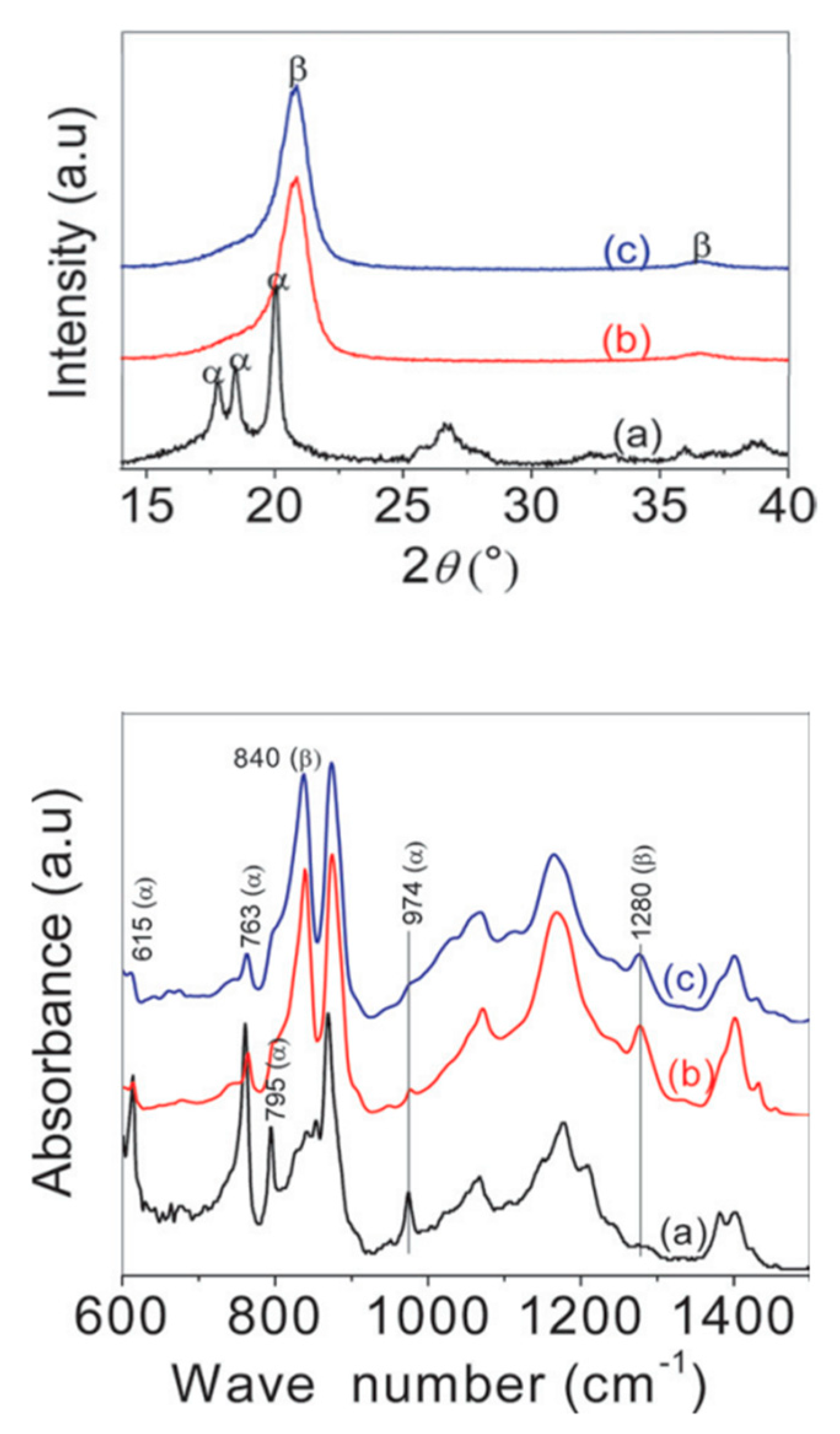

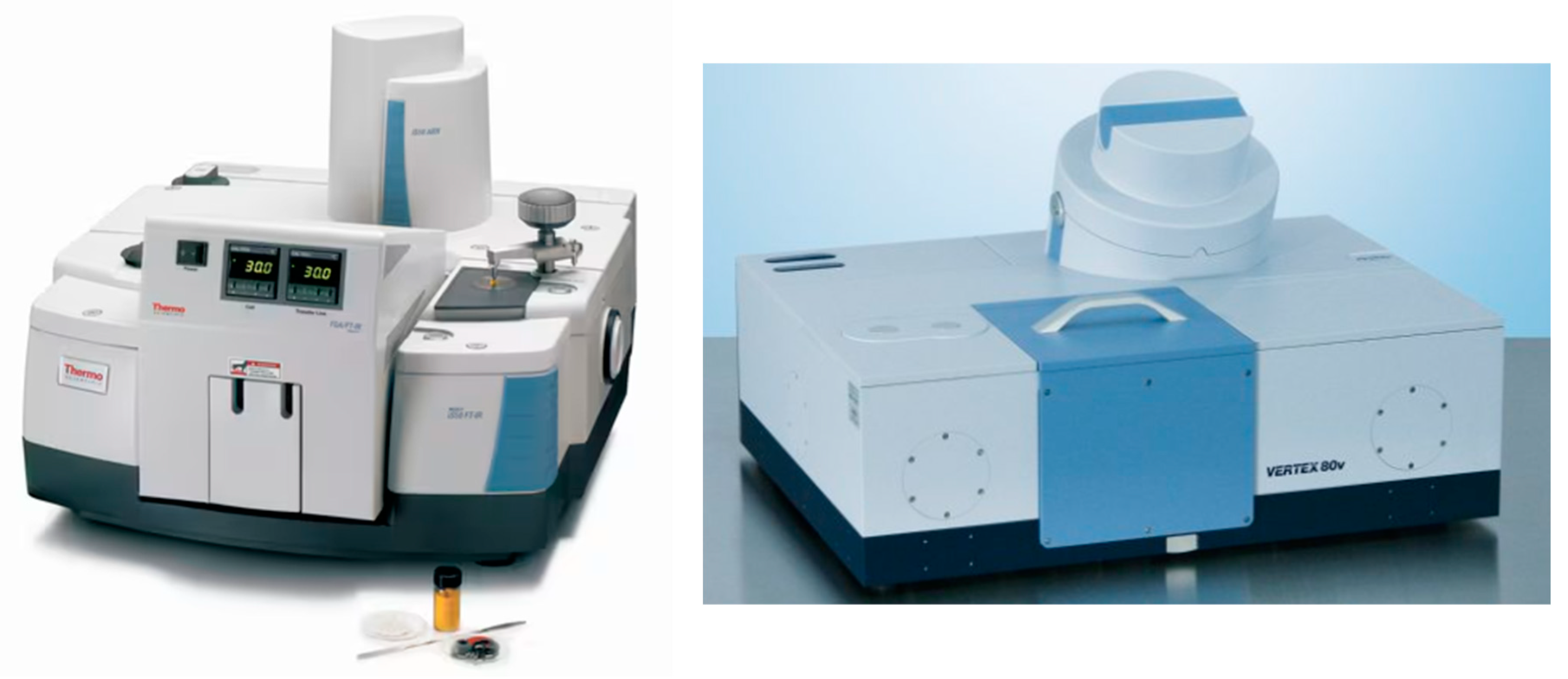

4.2. Structural Characterization

4.3. Mechanical Characterization

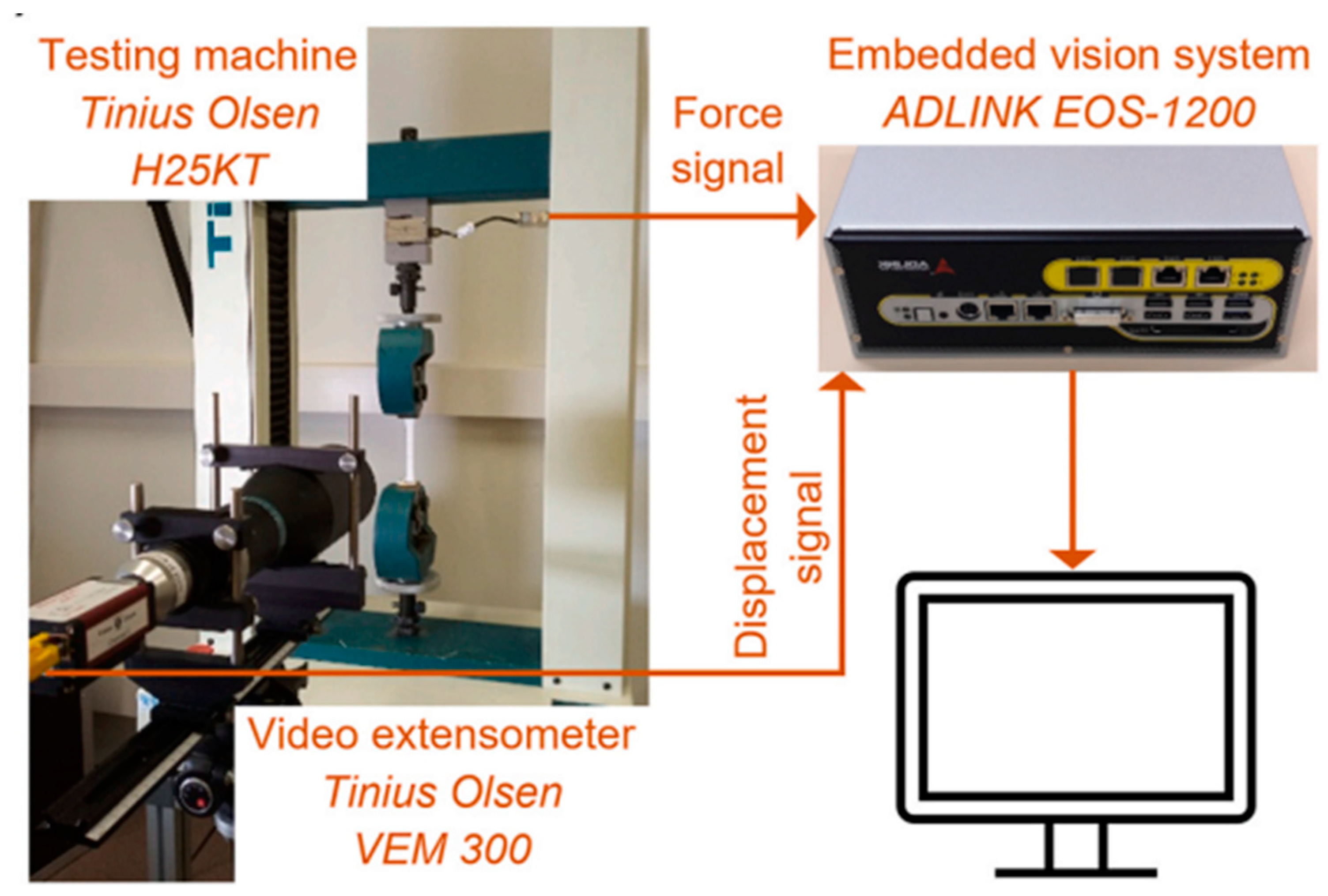

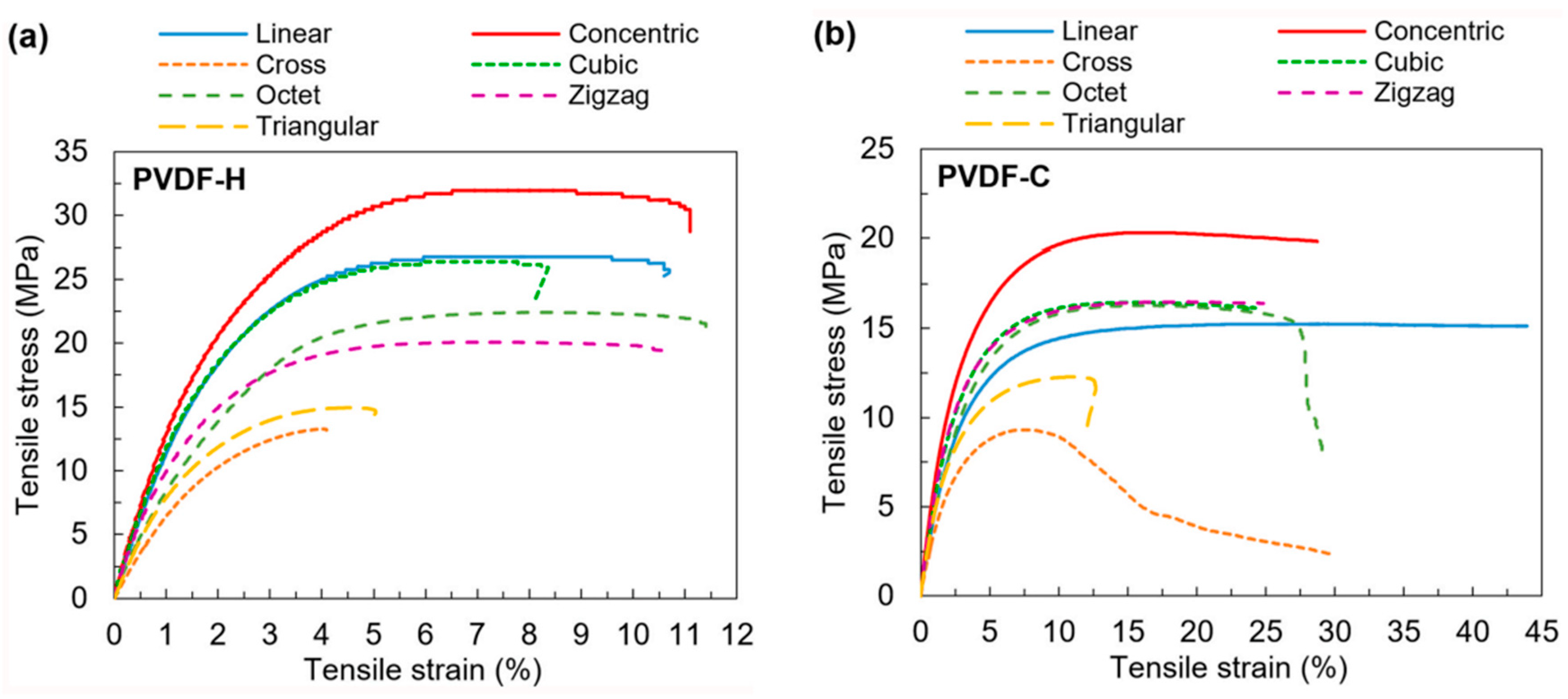

4.3.1. Tensile Testing

4.4. Electrical Characterization

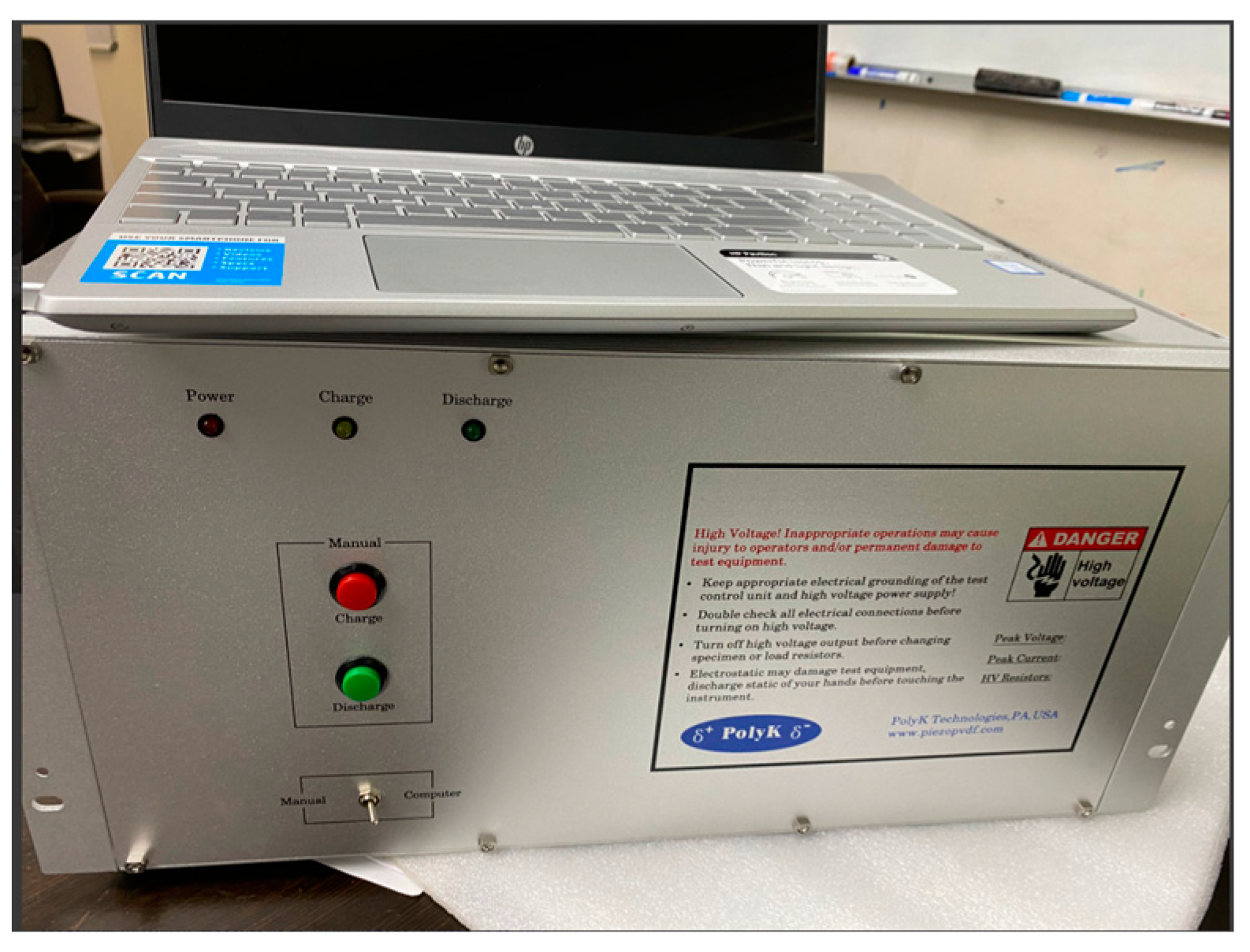

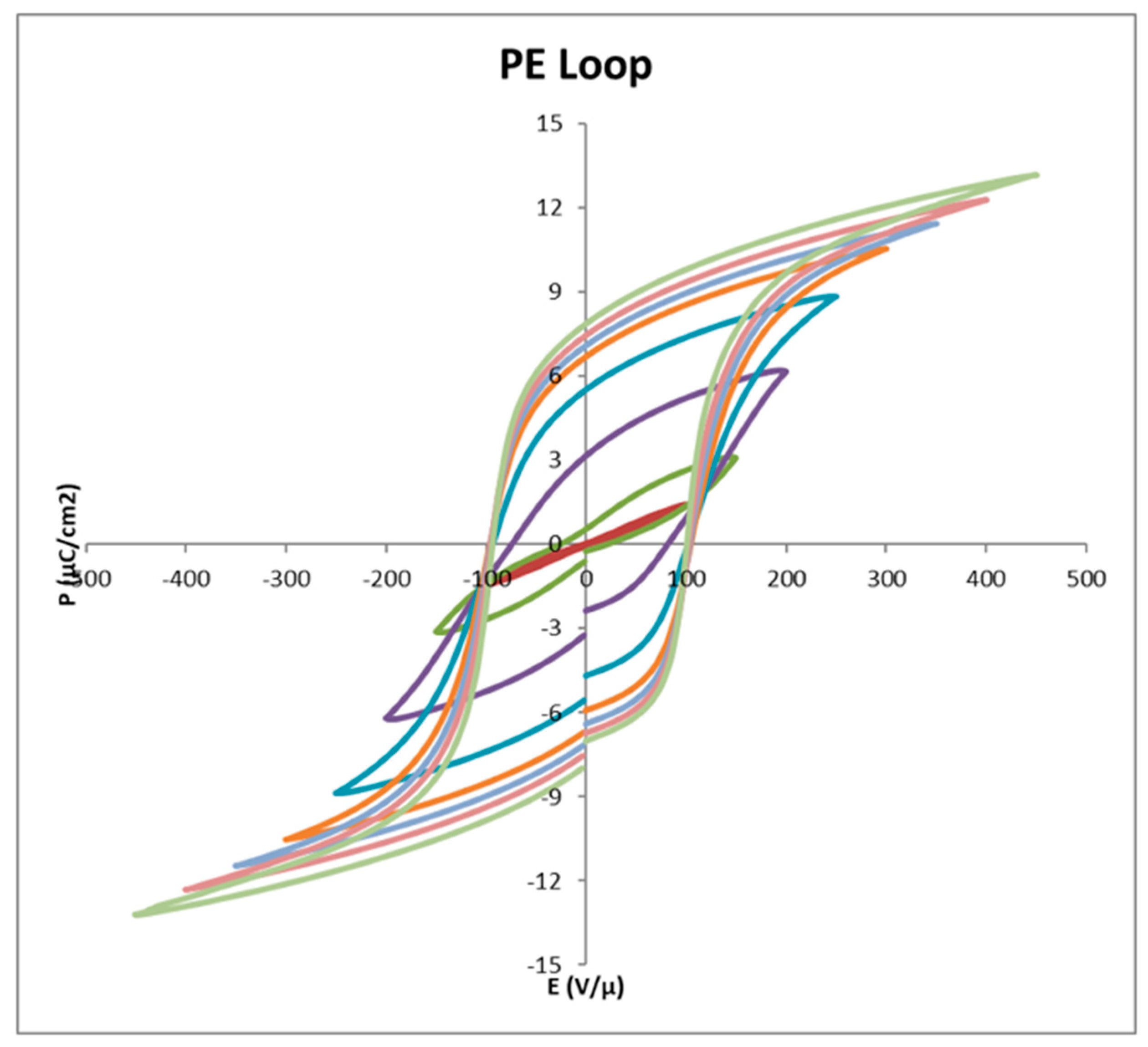

4.4.1. Ferroelectricity

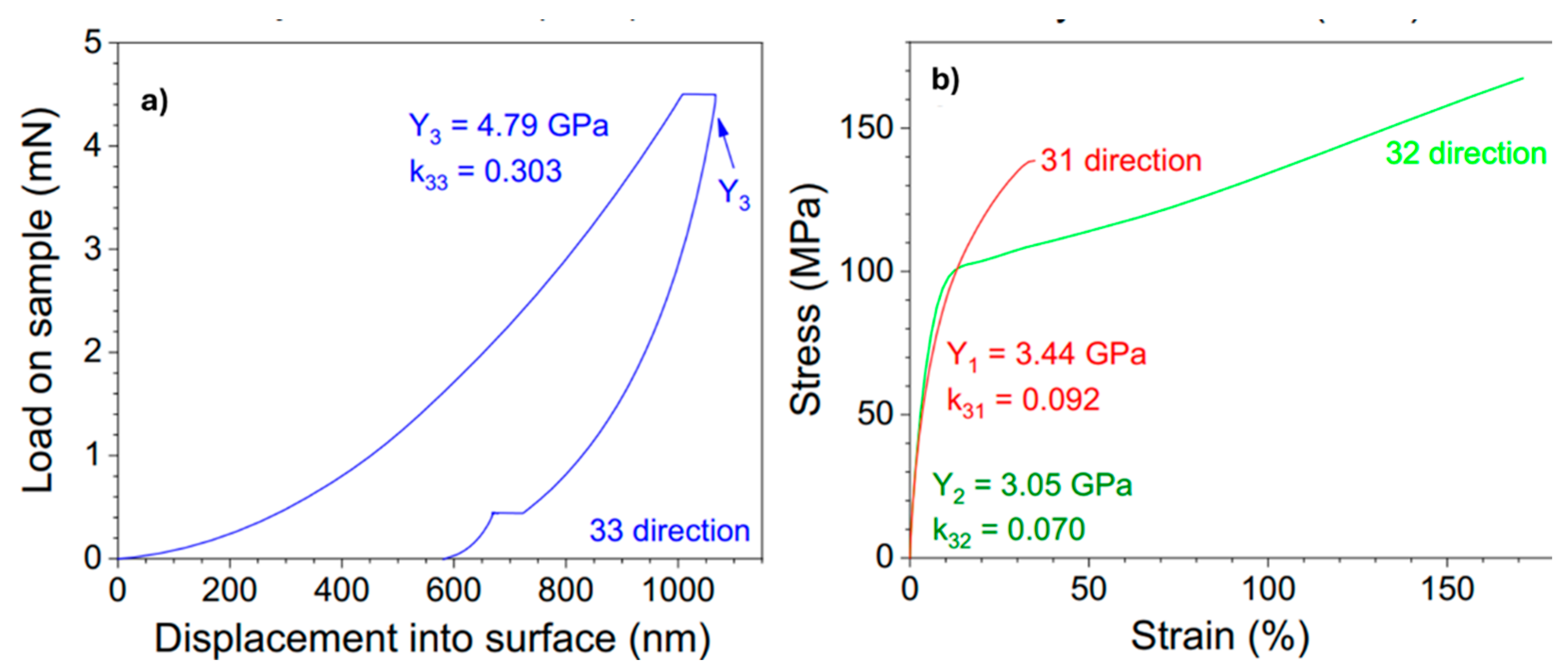

4.5. Electromechanical Properties

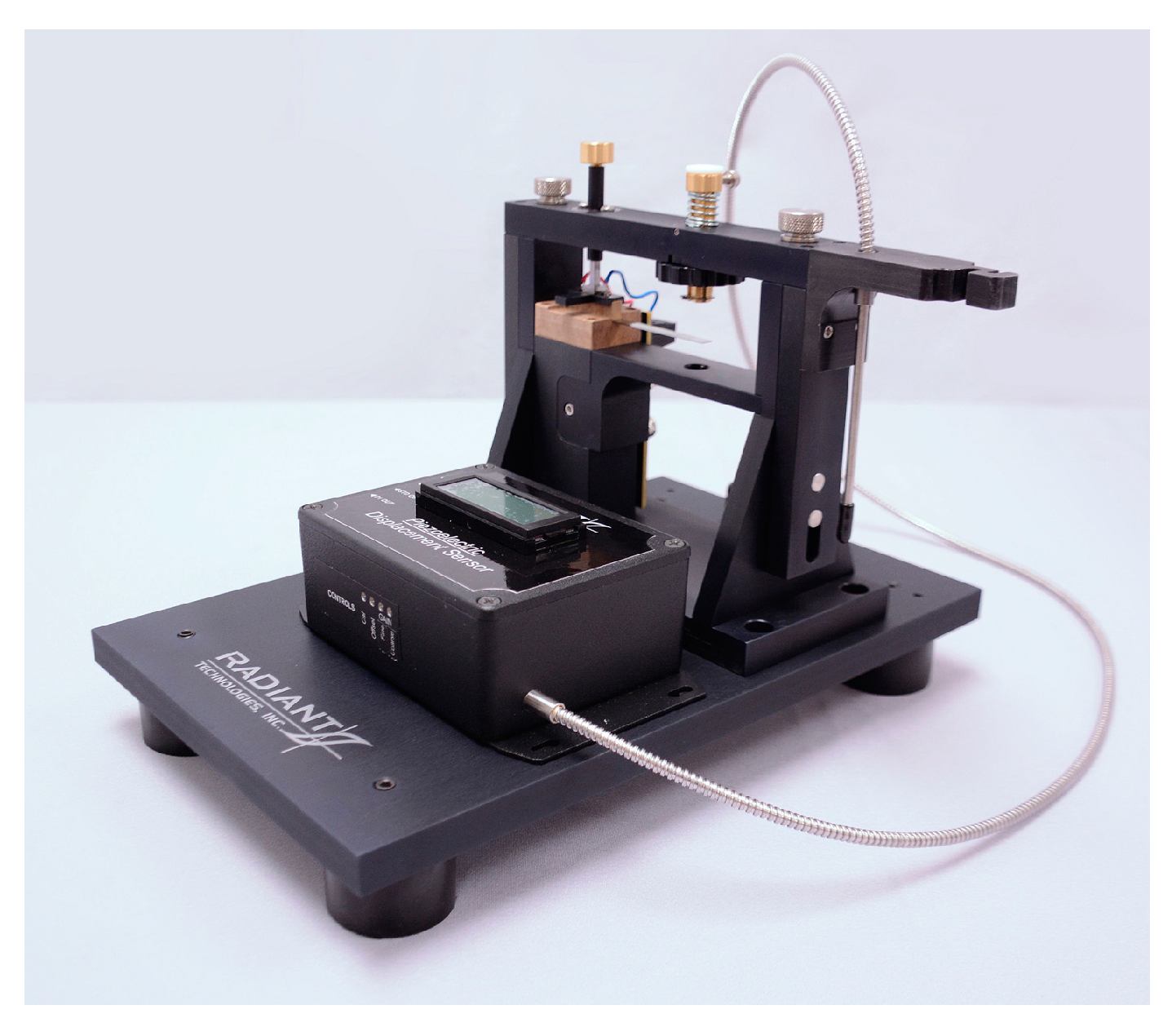

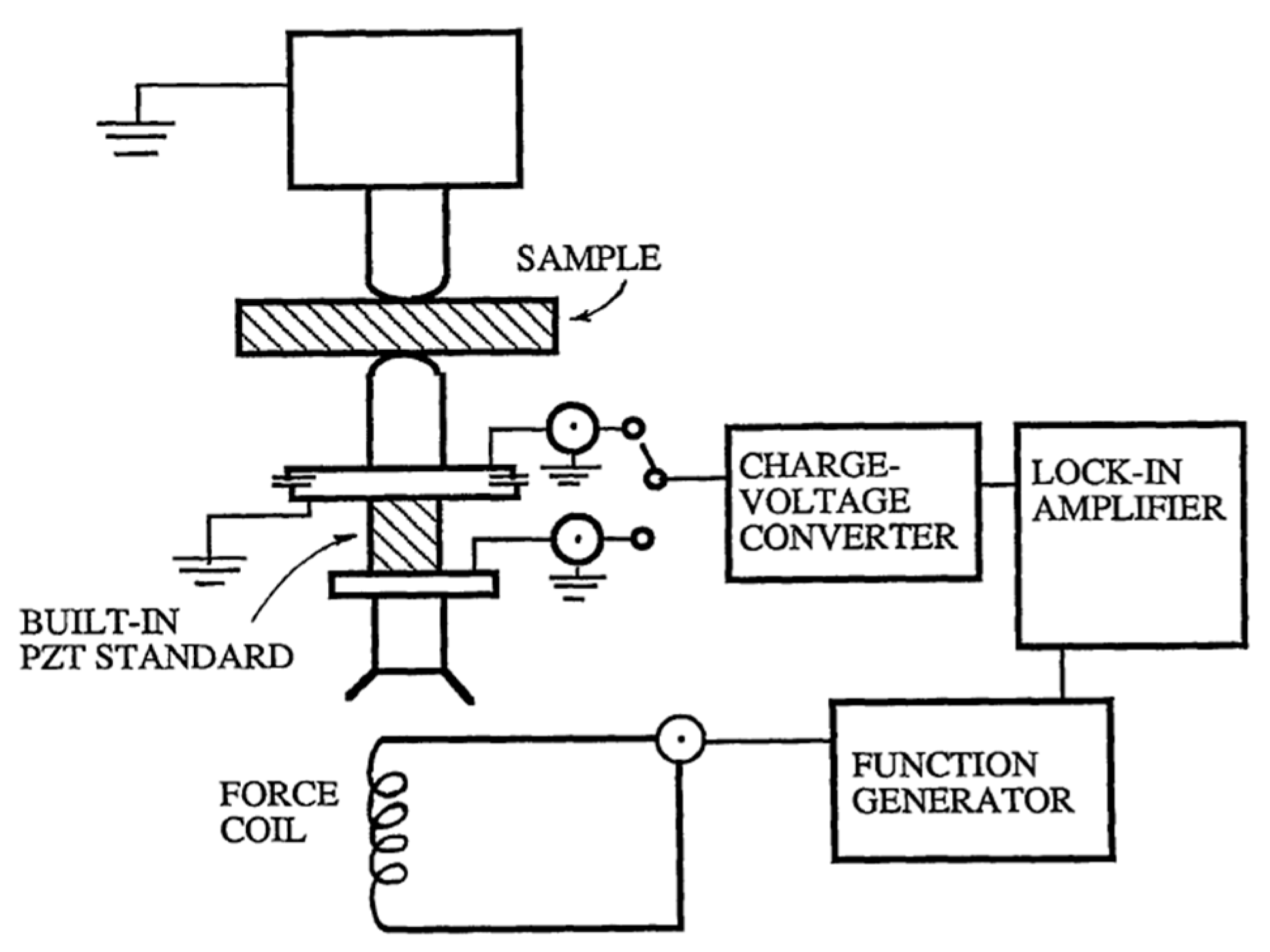

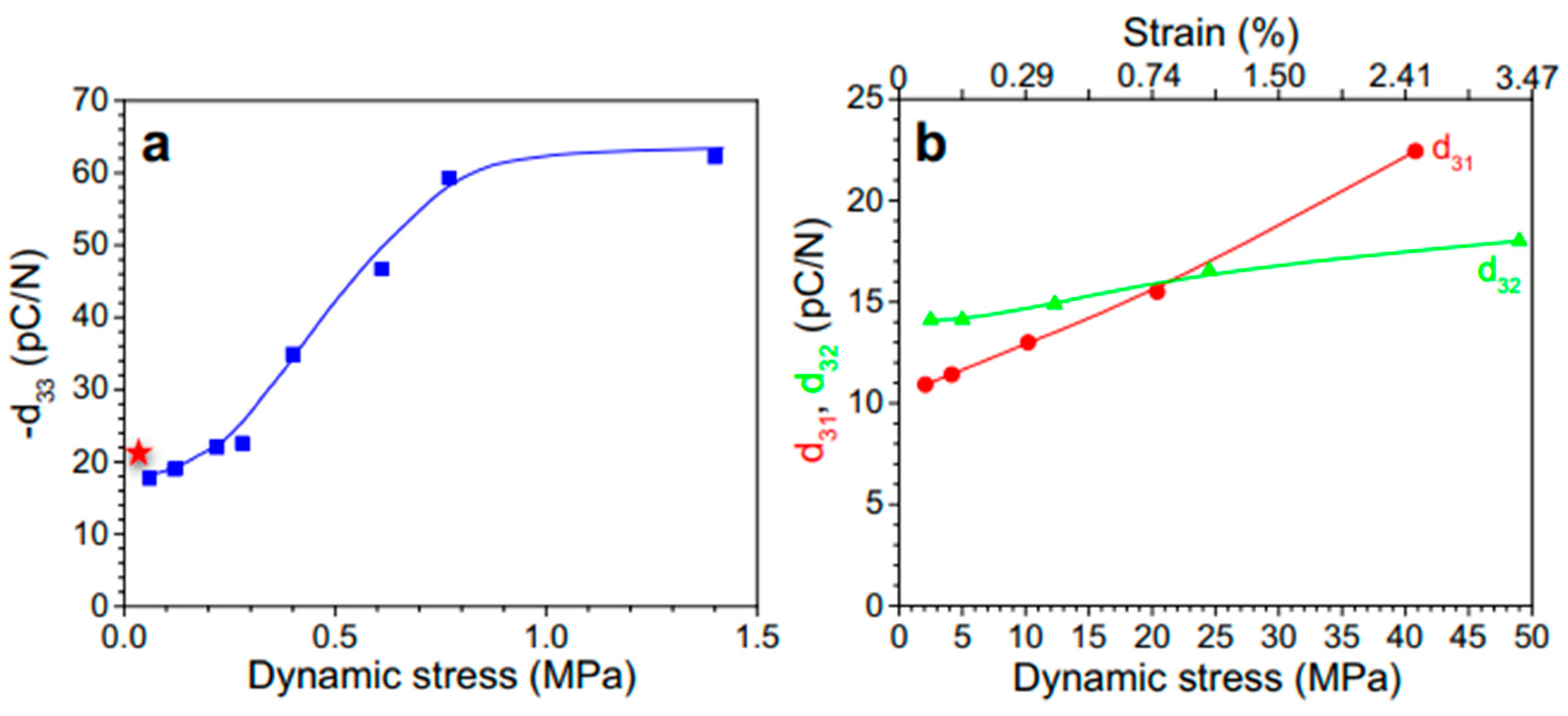

4.5.1. Piezoelectric Coefficient by Direct Methods

Quasi-Static Method

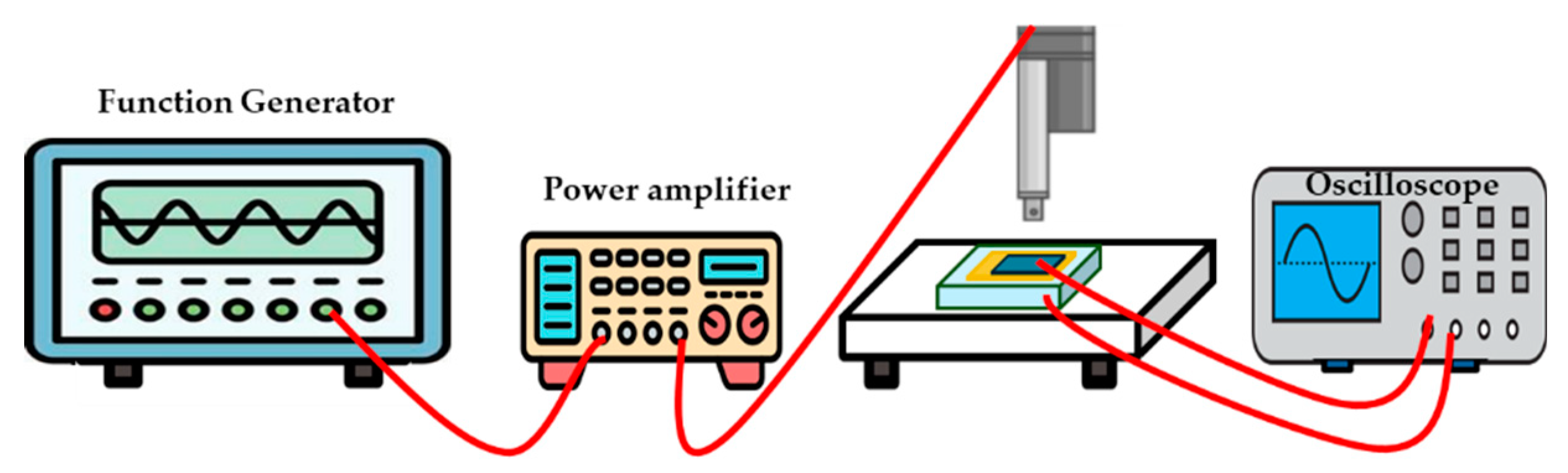

Dynamic Method

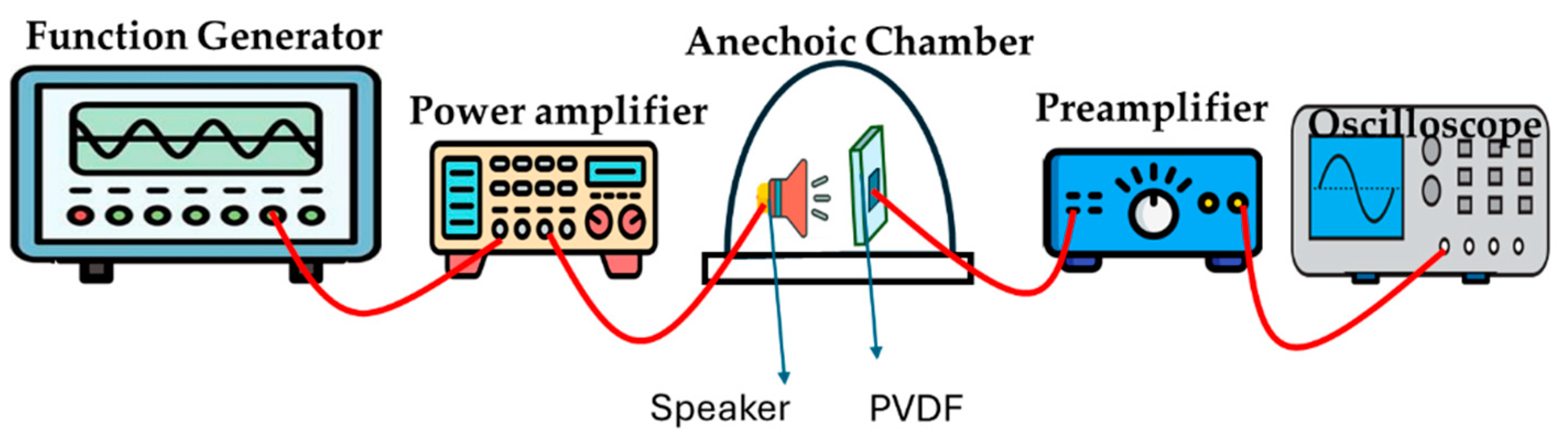

Acoustic Method

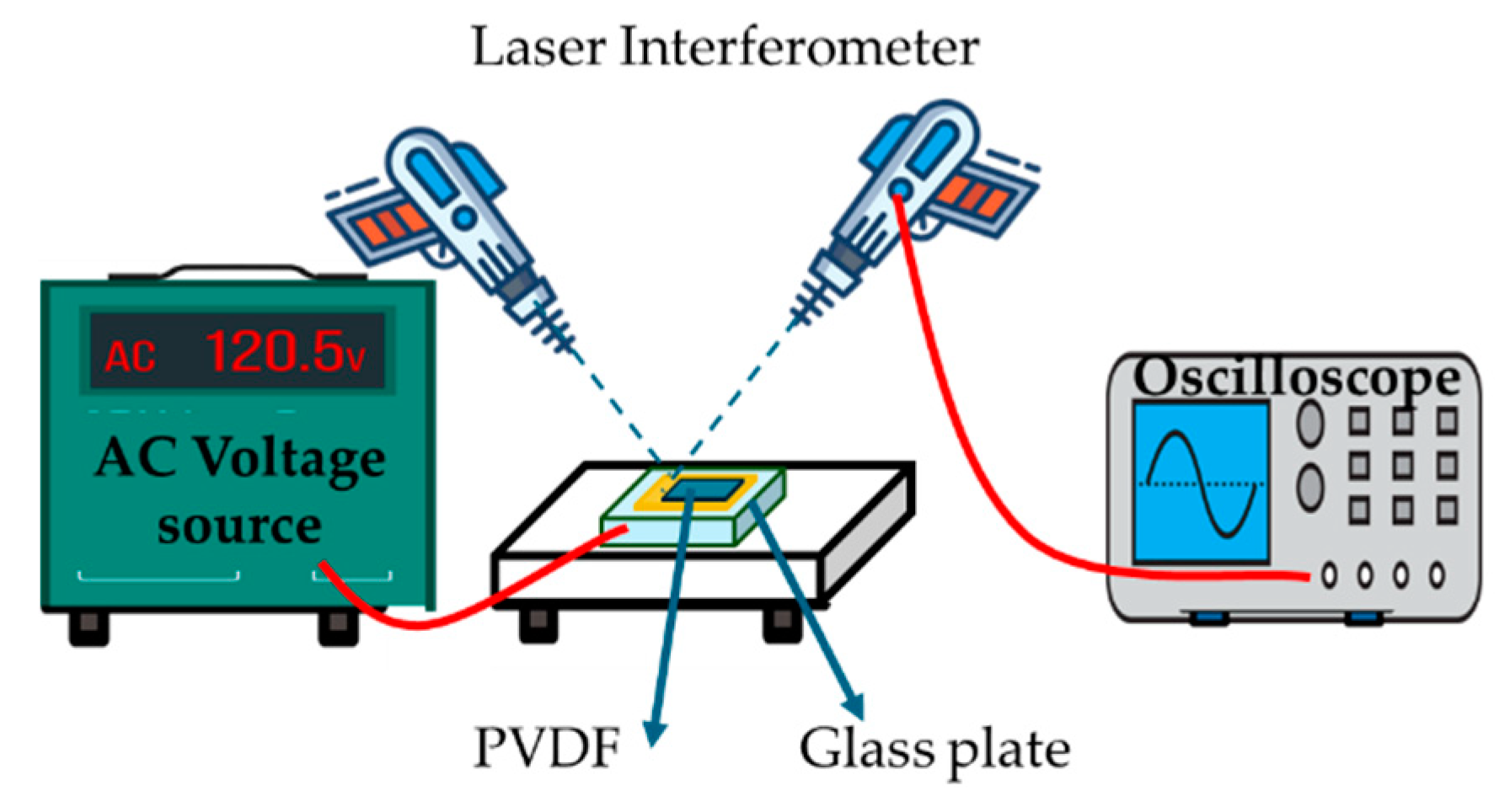

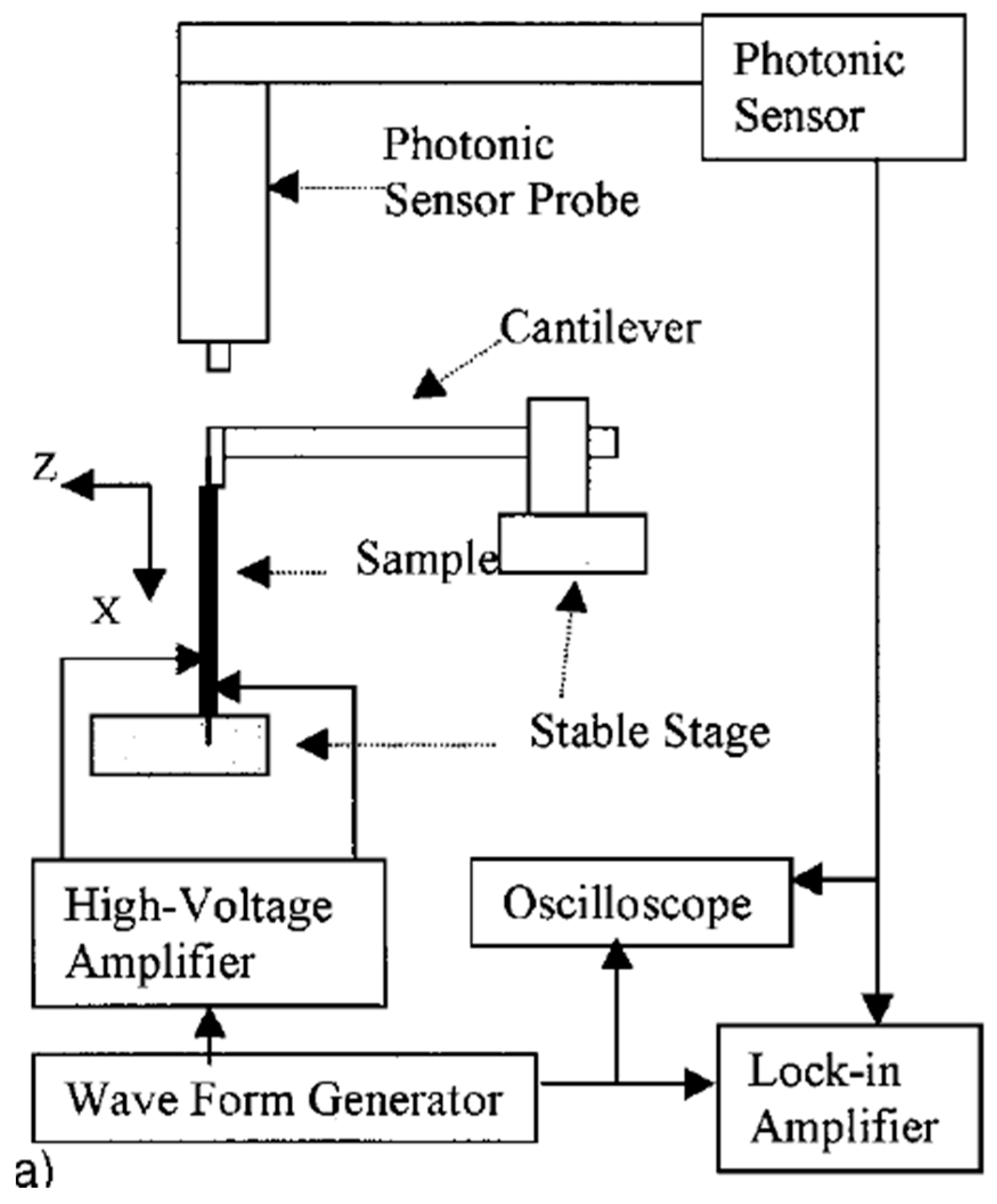

4.5.2. Strain Induced by Indirect Piezoelectric Effect

4.5.3. Resonance Methods

4.6. Pyroelectric Coefficient

5. Summary and Future Pespectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Smith, M.; Kar-Narayan, S. Piezoelectric polymers: theory, challenges and opportunities. International Materials Reviews 2022, 67, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, K.S.; Sameoto, D.; Evoy, S. A review of piezoelectric polymers as functional materials for electromechanical transducers. Smart Mater Struct 2014, 23, 033001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; et al. Piezoelectric Actuators and Motors: Materials, Designs, and Applications. Adv Mater Technol 2020, 5, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Unnikrishnan, L.; Nayak, S.K.; Mohanty, S. Advances in Piezoelectric Polymer Composites for Energy Harvesting Applications: A Systematic Review. Macromol Mater Eng 2019, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueberschlag, P. PVDF piezoelectric polymer. Sensor Review 2001, 21, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadpourfazeli, S.; Arash, S.; Ansari, A.; Yang, S.; Mallick, K.; Bagherzadeh, R. Future prospects and recent developments of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) piezoelectric polymer; fabrication methods, structure, and electro-mechanical properties. RSC Adv 2023, 13, 370–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalimuldina, G.; et al. A Review of Piezoelectric PVDF Film by Electrospinning and Its Applications. Sensors 2020, 20, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.; Zeng, X.C. Elastic properties of poly(vinyldene fluoride) (PVDF) crystals: A density functional theory study. J Appl Phys 2011, 109, 093514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; You, M.; Yi, N.; Zhang, X.; Xiang, Y. Enhanced Piezoelectric Coefficient of PVDF-TrFE Films via In Situ Polarization. Front Energy Res 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrau, S.; et al. Nanoscale Investigations of α- and γ-Crystal Phases in PVDF-Based Nanocomposites. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10, 13092–13099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrekrstos, A.; Muzata, T.S.; Ray, S.S. Nanoparticle-Enhanced β-Phase Formation in Electroactive PVDF Composites: A Review of Systems for Applications in Energy Harvesting, EMI Shielding, and Membrane Technology. ACS Appl Nano Mater 2022, 5, 7632–7651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; et al. Recent Progress on Structure Manipulation of Poly(vinylidene fluoride)-Based Ferroelectric Polymers for Enhanced Piezoelectricity and Applications. Adv Funct Mater 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.K.; et al. In situ -grown organo-lead bromide perovskite-induced electroactive γ-phase in aerogel PVDF films: an efficient photoactive material for piezoelectric energy harvesting and photodetector applications. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 7214–7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, A.C.; Caparros, C.; Ribelles, J.L.G.; Neves, I.C.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Electrical and thermal behavior of γ-phase poly(vinylidene fluoride)/NaY zeolite composites. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2012, 161, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; et al. Revisiting the δ-phase of poly(vinylidene fluoride) for solution-processed ferroelectric thin films. Nat Mater 2013, 12, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curie, J.; Curie, P. Développement par compression de l’électricité polaire dans les cristaux hémièdres à faces inclinées. Bulletin de la Société minéralogique de France 1880, 3, 90–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, H. The Piezoelectricity of Poly (vinylidene Fluoride). Jpn J Appl Phys 1969, 8, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- “M. TAMURA, Y. T, O. T, and Y. T, ‘ELECTROACOUSTIC TRANSDUCERS WITH PIEZOELECTRIC HIGH POLYMER FILMS.,’ ELECTROACOUSTIC TRANSDUCERS WITH PIEZOELECTRIC HIGH POLYMER FILMS., 1975”.

- Cheng, Z.; Xu, T.-B.; Zhang, Q.; Meyer, R.; Van Tol, D.; Hughes, J. Design, fabrication, and performance of a flextensional transducer based on electrostrictive polyvinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene copolymer. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 2002, 49, 1312–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.-B.; Cheng, Z.-Y.; Zhang, Q.M. High-performance micromachined unimorph actuators based on electrostrictive poly(vinylidene fluoride–trifluoroethylene) copolymer. Appl Phys Lett 2002, 80, 1082–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.-Y.; Bharti, V.; Xu, T.-B.; Xu, H.; Mai, T.; Zhang, Q.M. Electrostrictive poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) copolymers. Sens Actuators A Phys 2001, 90, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.M.; Bharti, V.; Zhao, X. Giant Electrostriction and Relaxor Ferroelectric Behavior in Electron-Irradiated Poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) Copolymer. Science (1979) 1998, 280, 2101–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.-B.; Su, J. Development, characterization, and theoretical evaluation of electroactive polymer-based micropump diaphragm. Sens Actuators A Phys 2005, 121, 267–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Xu, T.-B.; Zhang, S.; Shrout, T.R.; Zhang, Q. An electroactive polymer-ceramic hybrid actuation system for enhanced electromechanical performance. Appl Phys Lett 2004, 85, 1045–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.-B.; Su, J. Theoretical modeling of electroactive polymer-ceramic hybrid actuation systems. J Appl Phys 2005, 97, 034908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.S.O.Z. Piezoelectric Polymers. 2001. Available online: http://www.sti.nasa.gov.

- Zhu, G.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yan, X. Piezoelectricity in β-phase PVDF crystals: A molecular simulation study. Comput Mater Sci 2008, 44, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, A.; Gustafsson, C.; Bertilsson, H.; Rychwalski, R.W. Enhancement of β phase crystals formation with the use of nanofillers in PVDF films and fibres. Compos Sci Technol 2011, 71, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Rault, F.; Lewandowski, M.; Mohsenzadeh, E.; Salaün, F. Electrospun PVDF Nanofibers for Piezoelectric Applications: A Review of the Influence of Electrospinning Parameters on the β Phase and Crystallinity Enhancement. Polymers (Basel) 2021, 13, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajkiewicz, P.; Wasiak, A.; Gocłowski, Z. Phase transitions during stretching of poly(vinylidene fluoride). Eur Polym J 1999, 35, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.J.; et al. Spin cast ferroelectric beta poly(vinylidene fluoride) thin films via rapid thermal annealing. Appl Phys Lett 2008, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Lei, D.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L.; Hu, N. Influences of poling temperature and elongation ratio on PVDF-HFP piezoelectric films. Nanotechnol Rev 2021, 10, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, C.; Ameduri, B.; Boutevin, B.; Dolbier, W.R.; Winter, R.; Gard, G. Radical Terpolymerization of 1,1,2-Trifluoro-2-pentafluorosulfanylethylene and Pentafluorosulfanylethylene in the Presence of Vinylidene Fluoride and Hexafluoropropylene by Iodine Transfer Polymerization. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Mao, B.E., and M. A., “Ferroelectric Properties and Polarization Switching Kinetic of Poly (vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) Copolymer,” in Ferroelectrics - Physical Effects, InTech, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.W.; Choi, J.K.; Park, J.T.; Kim, J.H. Proton conducting poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-chlorotrifluoroethylene) graft copolymer electrolyte membranes. J Memb Sci 2008, 313, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameduri, B. From Vinylidene Fluoride (VDF) to the Applications of VDF-Containing Polymers and Copolymers: Recent Developments and Future Trends. Chem Rev 2009, 109, 6632–6686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahbab, N.; Xu, T.-B. Multifunctional Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF)-Based Polymer, Copolymer, and Compo-Sites for Aerospace Applications: A Comprehensive Technical Review. in ASME 2024 Aerospace Structures, Structural Dynamics, and Materials Conference, American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Drobny, J.G. Fluoropolymers in automotive applications. Polym Adv Technol 2007, 18, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.M.; et al. Smart and Multifunctional Materials Based on Electroactive Poly(vinylidene fluoride): Recent Advances and Opportunities in Sensors, Actuators, Energy, Environmental, and Biomedical Applications. Chem Rev 2023, 123, 11392–11487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-W.; Li, B.; Sun, L.; Lively, B.; Zhong, W.-H. The effects of nanofillers, stretching and recrystallization on microstructure, phase transformation and dielectric properties in PVDF nanocomposites. Eur Polym J 2012, 48, 1062–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Shen, Y.; Xi, N.; Tan, X. Integrated sensing for ionic polymer–metal composite actuators using PVDF thin films. Smart Mater Struct 2007, 16, S262–S271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Chung, G.-S. Synthesis of PVDF-graphene nanocomposites and their properties. J Alloys Compd 2013, 581, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Khatun, M.; Nasrin, L.; Raihan, M.J.; Rahman, M. Pure β -phase formation in polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)-carbon nanotube composites. J Phys D Appl Phys 2017, 50, 163002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Ende, D.A.; van de Wiel, H.J.; Groen, W.A.; van der Zwaag, S. Direct strain energy harvesting in automobile tires using piezoelectric PZT–polymer composites. Smart Mater Struct 2012, 21, 015011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.-H.; Jian, J.-W.; Yang, C.; Lei, T.; Cheng, T. Piezoelectric Performance of PVDF Composites for Transportation Engineering: A Multi-Scale Simulation Study. in Volume 3: Advanced Materials: Design, Processing, Characterization, and Applications, American Society of Mechanical Engineers, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Vatansever, D.; Hadimani, R.L.; Shah, T.; Siores, E. An investigation of energy harvesting from renewable sources with PVDF and PZT. Smart Mater Struct 2011, 20, 055019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Zhang, Z. PVDF-based dielectric polymers and their applications in electronic materials. IET Nanodielectrics 2018, 1, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanceros-Méndez, S.; Mano, J.F.; Costa, A.M.; Schmidt, V.H. FTIR AND DSC STUDIES OF MECHANICALLY DEFORMED β-PVDF FILMS. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B 2001, 40, 517–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapron, D.; et al. In-situ Raman monitoring of the poly(vinylidene fluoride) crystalline structure during a melt-spinning process. Journal of Raman Spectroscopy 2021, 52, 1073–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; et al. Recent advances in the preparation of PVDF-based piezoelectric materials. Nanotechnol Rev 2022, 11, 1386–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, S.; Feng, J.; Xiong, Y.; Tian, S.; Liu, S.; Kong, L. Performance and Mechanism of Piezo-Catalytic Degradation of 4-Chlorophenol: Finding of Effective Piezo-Dechlorination. Environ Sci Technol 2017, 51, 6560–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.-X.; et al. A review of microphase separation of polyurethane: Characterization and applications. Polym Test 2022, 107, 107489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrlík, M.; et al. Comparative Study of PVDF Sheets and Their Sensitivity to Mechanical Vibrations: The Role of Dimensions, Molecular Weight, Stretching and Poling. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, C.; Markevicius, V. Development of Ultrasound Piezoelectric Transducer-Based Measurement of the Piezoelectric Coefficient and Comparison with Existing Methods. Processes 2023, 11, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://piezopvdf.com/, “PolyK piezoelectric PVDF.”.

- Xu, T.-B.; Su, J. Design, modeling, fabrication, and performances of bridge-type high-performance electroactive polymer micromachined actuators. Journal of Microelectromechanical Systems 2005, 14, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chunduri, S. PVDF Rules Backsheet Market . Nov. 2020. Available online: http://taiyangnews.info/technology/a-review-backsheet-components/ (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Brien, J.J.G.G.S.O. Photovoltaic Module Using PVDF Based Flexible Glazing Film. May 01, 2018.

- Task, I.P.V.S. Task 13 Performance, Operation and Reliability of Photovoltaic Systems. Apr. 2021. Available online: www.iea-pvps.org.

- Qi, F.; Xu, L.; He, Y.; Yan, H.; Liu, H. PVDF-Based Flexible Piezoelectric Tactile Sensors: Review. Crystal Research and Technology 2023, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sappati, K.K.; Bhadra, S. Piezoelectric Polymer and Paper Substrates: A Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dallaev, R.; Pisarenko, T.; Sobola, D.; Orudzhev, F.; Ramazanov, S.; Trčka, T. Brief Review of PVDF Properties and Applications Potential. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14, 4793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Concha, V.O.C.; et al. Properties, characterization and biomedical applications of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF): a review. J Mater Sci 2024, 59, 14185–14204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G.; Cao, Y. Application and modification of poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) membranes – A review. J Memb Sci 2014, 463, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golda-Cepa, M.; Engvall, K.; Hakkarainen, M.; Kotarba, A. Recent progress on parylene C polymer for biomedical applications: A review. Prog Org Coat 2020, 140, 105493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nivedhitha, D.M.; Jeyanthi, S. Polyvinylidene fluoride, an advanced futuristic smart polymer material: A comprehensive review. Polym Adv Technol 2023, 34, 474–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.S.; Bhatt, U.M.; Gautam, P.; Thote, S.; Joglekar, M.M.; Manhas, S.K. Fabrication and modeling of β-phase PVDF-TrFE based flexible piezoelectric energy harvester. Sens Actuators A Phys 2020, 304, 111879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sencadas, V.; Gregorio, R.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. α to β Phase Transformation and Microestructural Changes of PVDF Films Induced by Uniaxial Stretch. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B 2009, 48, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovinger, A.J. Poly(Vinylidene Fluoride). in Developments in Crystalline Polymers—1, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 1982, 195–273. [CrossRef]

- Barrau, S.; et al. Nanoscale Investigations of α- And γ-Crystal Phases in PVDF-Based Nanocomposites. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018, 10, 13092–13099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.S.; Bhatt, U.M.; Gautam, P.; Thote, S.; Joglekar, M.M.; Manhas, S.K. Fabrication and modeling of β-phase PVDF-TrFE based flexible piezoelectric energy harvester. Apr. 01, 2020, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.H.; Singh, S.; Khare, N. Enhanced β-phase in PVDF polymer nanocomposite and its application for nanogenerator. Polym Adv Technol 2018, 29, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, E.; Bose, N.; Das, S.; Mukherjee, N.; Mukherjee, S. Enhancement of electroactive β phase crystallization and dielectric constant of PVDF by incorporating GeO2 and SiO2 nanoparticles. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2015, 17, 22784–22798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sencadas, V.; Gregorio, R.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. α to β phase transformation and microestructural changes of PVDF films induced by uniaxial stretch. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B: Physics 2009, 48, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.K.; et al. In situ -grown organo-lead bromide perovskite-induced electroactive γ-phase in aerogel PVDF films: An efficient photoactive material for piezoelectric energy harvesting and photodetector applications. Nanoscale 2020, 12, 7214–7230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.C.; Caparros, C.; Ribelles, J.L.G.; Neves, I.C.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Electrical and thermal behavior of γ-phase poly(vinylidene fluoride)/NaY zeolite composites. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2012, 161, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; et al. Revisiting the δ-phase of poly(vinylidene fluoride) for solution-processed ferroelectric thin films. Nature Materials 2013, 12, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovinger, A.J. POLY(VINYLIDENE FLUORIDE). 1982.

- Fortunato, M.; et al. Phase Inversion in PVDF Films with Enhanced Piezoresponse Through Spin-Coating and Quenching. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11, 1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; et al. Recent Progress on Structure Manipulation of Poly(vinylidene fluoride)-Based Ferroelectric Polymers for Enhanced Piezoelectricity and Applications. Adv Funct Mater 2023, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxena, P.; Shukla, P. A comprehensive review on fundamental properties and applications of poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF). Adv Compos Hybrid Mater 2021, 4, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TZOU, H.S.; LEE, H.-J.; ARNOLD, S.M. Smart Materials, Precision Sensors/Actuators, Smart Structures, and Structronic Systems. Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures 2004, 11, 367–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, N.A.; Liu, Y.; Li, K. Stability of PVDF hollow fibre membranes in sodium hydroxide aqueous solution. Chem Eng Sci 2011, 66, 1565–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Wang, J.; Qu, D.; Luan, Z.; Ren, X. Fabrication and characterization of hydrophobic PVDF hollow fiber membranes for desalination through direct contact membrane distillation. Sep Purif Technol 2009, 69, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, H. Fluorination of polyhydrofluoroethylenes. II. Formation of perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids on the surface region of poly(vinylidene fluoride) film by oxyfluorination, fluorination, and hydrolysis. Journal of Polymer Science: Polymer Chemistry Edition 1979, 17, 1543–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, M.; Küunstler, W.; Gerhard-Multhaupt, R. Poling Behavior and Optical Absorption of Partially Dehydrofluorinated and Uniaxially Stretched Polyvinylidene Fluoride. Ferroelectrics 2006, 336, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspitasari, V.; Granville, A.; Le-Clech, P.; Chen, V. Cleaning and ageing effect of sodium hypochlorite on polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. Sep Purif Technol 2010, 72, 301–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, I.; Shin, Y.-H.; Kim, S.; Choi, J.; Kang, C.-Y. Flexible piezoelectric polymer-based energy harvesting system for roadway applications. Appl Energy 2017, 197, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, M.; Chen, W.; Geerlings, H.; Asta, M.; Persson, K.A. A database to enable discovery and design of piezoelectric materials. Sci Data 2015, 2, 150053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa, T. Ferroelectric properties of vinylidene fluoride copolymers. Phase Transitions 1989, 18, 143–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naber, R.C.G.; Asadi, K.; Blom, P.W.M.; de Leeuw, D.M.; de Boer, B. Organic Nonvolatile Memory Devices Based on Ferroelectricity. Advanced Materials 2010, 22, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. M. G. M. E. Lines, Principles and Applications of Ferroelectrics and Related Materials. 2001. Available online: https://books.google.com/books/about/Principles_and_Applications_of_Ferroelec.html?id=p6ruJH8C84kC (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Wan, C.; Bowen, C.R. Multiscale-structuring of polyvinylidene fluoride for energy harvesting: the impact of molecular-, micro- and macro-structure. J Mater Chem A Mater 2017, 5, 3091–3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cauda, V.; Stassi, S.; Bejtka, K.; Canavese, G. Nanoconfinement: an Effective Way to Enhance PVDF Piezoelectric Properties. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2013, 5, 6430–6437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kausar, A.; Chang, C.-Y.; Raja, M.A.Z.; Zameer, A.; Shoaib, M. Novel design of recurrent neural network for the dynamical of nonlinear piezoelectric cantilever mass–beam model. The European Physical Journal Plus 2024, 139, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, A.; Chang, C.-Y.; Raja, M.A.Z.; Shoaib, M. A novel design of layered recurrent neural networks for fractional order Caputo–Fabrizio stiff electric circuit models. Modern Physics Letters B 2024, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zameer, A.; Naz, S.; Raja, M.A.Z. Parallel differential evolution paradigm for multilayer electromechanical device optimization. Modern Physics Letters B 2024, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhao, G.; Li, B.; Wang, J. Design optimization of PVDF-based piezoelectric energy harvesters. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Raja, M.A.Z.; Kausar, A.; Zameer, A.; Mehmood, A.; Shoaib, M. Dynamics of nonlinear cantilever piezoelectric–mechanical system: An intelligent computational approach. Math Comput Simul 2022, 196, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zameer, A.; Naz, S.; Raja, M.A.Z.; Hafeez, J.; Ali, N. Neuro-Evolutionary Framework for Design Optimization of Two-Phase Transducer with Genetic Algorithms. Micromachines (Basel) 2023, 14, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Usman, A.; Zameer, A.; Muhammad, K.; Raja, M.A.Z. Efficient multivariate optimization of an ultrasonic transducer with genetic parallel algorithms. Waves in Random and Complex Media 2023, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, Z.; Naz, S.; Raja, M.A.Z.; Zameer, A. Design of wideband tonpilz transducers for underwater SONAR applications with finite element model. Applied Acoustics 2021, 183, 108293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Raja, M.A.Z.; Mehmood, A.; Zameer, A.; Shoaib, M. Neuro-intelligent networks for Bouc–Wen hysteresis model for piezostage actuator. The European Physical Journal Plus 2021, 136, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Raja, M.A.Z.; Mehmood, A.; Jaafery, A.Z. Intelligent Predictive Solution Dynamics for Dahl Hysteresis Model of Piezoelectric Actuator. Micromachines (Basel) 2022, 13, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sappati, K.K.; Bhadra, S. Piezoelectric polymer and paper substrates: A review. Sensors 2018, 18, 3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Xu, T.-B. A Comprehensive Review of Piezoelectric Ultrasonic Motors: Classifications, Characterization, Fabrication, Applications, and Future Challenges. Micromachines (Basel) 2024, 15, 1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. G. Cain, Ed., Characterisation of Ferroelectric Bulk Materials and Thin Films, vol. 2. in Springer Series in Measurement Science and Technology, vol. 2. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, R.; Abbasipour, M. Piezoelectric PVDF Polymeric Films and Fibers: Polymorphisms, Measurements, and Applications. in Industrial Applications for Intelligent Polymers and Coatings, Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016, 313–336. [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.; Tran, V.H.; Wang, J.; Fuh, Y.-K.; Lin, L. Direct-Write Piezoelectric Polymeric Nanogenerator with High Energy Conversion Efficiency. Nano Lett 2010, 10, 726–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, Y.; Suprapto; Chiu, C.; Gunawan, H. Characteristic analysis of biaxially stretched PVDF thin films. J Appl Polym Sci 2018, 135. [CrossRef]

- Sagar, R.; Gaur, S.S.; Gaur, M.S. Effect of BaZrO3 nanoparticles on pyroelectric properties of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF). J Therm Anal Calorim 2017, 128, 1235–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, M.C.; Veena, E.; Kumar, N.S.; Naidu, K.C.B.; Mallikarjuna, A.; Basha, D.B. A Review on Piezoelectric Materials and Their Applications. Crystal Research and Technology 2023, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PYROELECTRIC SANDWICH THERMAL ENERGY HARVESTERS. US 10 , 147 , 863 B2, Dec. 04, 2018. Available online: https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/e6/52/2e/7ab65ef12c4790/US10147863.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Tashiro, K. Crystal structure and phase transition of PVDF and related copolymers. Plastics Engineering-New York 1995, 28, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.; Tian, B.; Zhu, Q.; Duan, C. Characterization and Application of PVDF and Its Copolymer Films Prepared by Spin-Coating and Langmuir–Blodgett Method. Polymers (Basel) 2019, 11, 2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, L.; Yao, X.; Chang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Qin, G.; Zhang, X. Properties and applications of the β phase poly(vinylidene fluoride). Polymers 2018, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; et al. Enhancement of β-crystalline phase of poly(vinylidene fluoride) in the presence of hyperbranched copolymer wrapped multiwalled carbon nanotubes. J Colloid Interface Sci 2011, 363, 122–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navid, A.; Lynch, C.S.; Pilon, L. Purified and porous poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) thin films for pyroelectric infrared sensing and energy harvesting. Smart Mater Struct 2010, 19, 055006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, P.; Varughese, K.T.; Dwarakanath, K.; Varma, K.B.R. Dielectric properties of Poly(vinylidene fluoride)/CaCu3Ti4O12 composites. Compos Sci Technol 2010, 70, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.; Matsumoto, H.; Minagawa, M.; Tanioka, A.; Danno, T.; Horibe, H. Preparation of PVDF/PMMA Blend Nanofibers by Electrospray Deposition: Effects of Blending Ratio and Humidity. Polym J 2009, 41, 402–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Zheng, W.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Zhao, Z. Formation Mechanism of β-Phase in PVDF/CNT Composite Prepared by the Sonication Method. Macromolecules 2009, 42, 8870–8874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes-Pereira, J.; Martins, P.; Cardoso, V.F.; Costa, C.M.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. A green solvent strategy for the development of piezoelectric poly(vinylidene fluoride–trifluoroethylene) films for sensors and actuators applications. Mater Des 2016, 104, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Zhao, X.J.; Chen, S.J.; Ma, W.Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.L. Effect of solution-blended poly(styrene-co-acrylonitrile) copolymer on crystallization of poly(vinylidene fluoride). Express Polym Lett 2010, 4, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remeika, M.; Qi, Y. Scalable solution coating of the absorber for perovskite solar cells. Journal of Energy Chemistry 2018, 27, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotovvati, B.; Namdari, N.; Dehghanghadikolaei, A. On Coating Techniques for Surface Protection: A Review. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2019, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Liu, H.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, M.; Tang, Y. Preparation and electroactive properties of a PVDF/nano-TiO2 composite film. Appl Surf Sci 2011, 257, 3831–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, F.; et al. Recent progress in electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)-based nanofibers for sustainable energy and environmental applications. Prog Mater Sci 2025, 148, 101376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-C.; Hsu, W.-L.; Wang, Y.-T.; Ho, C.-T.; Chang, P.-Z. Enhance the Pyroelectricity of Polyvinylidene Fluoride by Graphene-Oxide Doping. Sensors 2014, 14, 6877–6890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyona, M.D. A theoritical study on spin coating technique. Advances in materials Research 2013, 2, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimi, A.; Yousefi, A.A. Analysis Method: FTIR studies of β-phase crystal formation in stretched PVDF films. Polym Test 2003, 22, 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffari, G.H.; Khan, M.S.I.; Mumtaz, F.; Wang, Y.; Khan, N.A. Manipulation of crystallization and dielectric relaxation dynamics via hot pressing and copolymerization of PVDF with Hexafluoropropylene. Journal of Polymer Research 2023, 30, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhumrash, S.; Gautam, A.; Kumar, A.; Jaglan, N.; Uniyal, P. Appreciable amelioration in the dielectric and energy storage behavior of the electrospun fluoropolymer PVDF-HFP thick films: Effect of hot-pressing. J Energy Storage 2024, 103, 114337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartono, A.; Djamal, M.; Satira, S.; Bahar, H. ; Ramli; Sanjaya, E. Effect of roll hot press temperature on crystallite size of PVDF film. 2014, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Chen, H.; Luo, H. Enhancing the energy storage performance of PVDF films through optimized hot-pressing temperatures. Ionics (Kiel) 2024, 30, 5341–5351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.-X.; Wang, M.-M.; Feng, Y.-H.; Qu, J.-P. β-Phase Formation of Polyvinylidene Fluoride via Hot Pressing under Cyclic Pulsating Pressure. Macromolecules 2020, 53, 8494–8501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.M.; Chou, M.H. Polymorphism, piezoelectricity and sound absorption of electrospun PVDF membranes with and without carbon nanotubes. Compos Sci Technol 2016, 127, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalimuldina, G.; et al. A Review of Piezoelectric PVDF Film by Electrospinning and Its Applications. Sensors 2020, 20, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, T.; Zhu, P.; Cai, X.; Yang, L.; Yang, F. Electrospinning of PVDF nanofibrous membranes with controllable crystalline phases. Applied Physics A 2015, 120, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaarour, B.; Zhu, L.; Jin, X. Controlling the surface structure, mechanical properties, crystallinity, and piezoelectric properties of electrospun PVDF nanofibers by maneuvering molecular weight. Soft Mater 2019, 17, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cailleaux, S.; Sanchez-Ballester, N.M.; Gueche, Y.A.; Bataille, B.; Soulairol, I. Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM), the new asset for the production of tailored medicines. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 330, 821–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheibi, A.; Bagherzadeh, R.; Merati, A.A.; Latifi, M. Electrical power generation from piezoelectric electrospun nanofibers membranes: electrospinning parameters optimization and effect of membranes thickness on output electrical voltage. Journal of Polymer Research 2014, 21, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, M.S.; et al. Understanding nucleation of the electroactive β-phase of poly(vinylidene fluoride) by nanostructures. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 113007–113015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Tarbutton, J.A. Electric poling-assisted additive manufacturing process for PVDF polymer-based piezoelectric device applications. Smart Mater Struct 2014, 23, 095044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhang, F.; Guan, S.; Zheng, J.; Xu, C. Wearable piezoelectric device assembled by one-step continuous electrospinning. J Mater Chem C Mater 2016, 4, 6988–6995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-E.; Shin, Y.-E.; Lee, G.-H.; Kim, J.; Ko, H.; Chae, H.G. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)/cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) nanocomposite fiber and triboelectric textile sensors. Compos B Eng 2021, 223, 109098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Achaby, M.; Arrakhiz, F.Z.; Vaudreuil, S.; Essassi, E.M.; Qaiss, A. Piezoelectric β-polymorph formation and properties enhancement in graphene oxide – PVDF nanocomposite films. Appl Surf Sci 2012, 258, 7668–7677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalimuldina, G.; et al. A review of piezoelectric pvdf film by electrospinning and its applications. Sensors 2020, 20, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Tarbutton, J.A. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) direct printing for sensors and actuators. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2019, 104, 3155–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, M.; Rong, M.; Ruan, W. Studies on the transformation process of PVDF from α to β phase by stretching. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 3938–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; et al. In-situ synchrotron SAXS and WAXS investigations on deformation and α–β transformation of uniaxial stretched poly(vinylidene fluoride). CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; et al. Can Relaxor Ferroelectric Behavior Be Realized for Poly(vinylidene fluoride- co -chlorotrifluoroethylene) [P(VDF–CTFE)] Random Copolymers by Inclusion of CTFE Units in PVDF Crystals? Macromolecules 2018, 51, 5460–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaur, A.; Kumar, C.; Tiwari, S.; Maiti, P. Efficient Energy Harvesting Using Processed Poly(vinylidene fluoride) Nanogenerator. ACS Appl Energy Mater 2018, 1, 3019–3024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; et al. Ultrahigh energy density of poly(vinylidene fluoride) from synergistically improved dielectric constant and withstand voltage by tuning the crystallization behavior. J Mater Chem A Mater 2021, 9, 27660–27671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, B.; Yousefi, A.A.; Bellah, S.M. Effect of tensile strain rate and elongation on crystalline structure and piezoelectric properties of PVDF thin films. Polym Test 2007, 26, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.P.; Costa, C.M.; Sencadas, V.; Paleo, A.J.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Degradation of the dielectric and piezoelectric response of β-poly(vinylidene fluoride) after temperature annealing. Journal of Polymer Research 2011, 18, 1451–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniasadi, M.; et al. Correlation of annealing temperature, morphology, and electro-mechanical properties of electrospun piezoelectric nanofibers. Polymer (Guildf) 2017, 127, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furukawa; Nakajima; Takahashi, “Factors governing ferroelectric switching characteristics of thin VDF/TrFE copolymer films. IEEE Transactions on Dielectrics and Electrical Insulation 2006, 13, 1120–1131. [CrossRef]

- Men, S.; Gao, Z.; Wen, R.; Tang, J.; Zhang, J.M. Effects of annealing time on physical and mechanical properties of <scp>PVDF</scp> microporous membranes by a melt extrusion-stretching process. Polym Adv Technol 2021, 32, 2397–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spampinato, N.; Maiz, J.; Portale, G.; Maglione, M.; Hadziioannou, G.; Pavlopoulou, E. Enhancing the ferroelectric performance of P(VDF-co-TrFE) through modulation of crystallinity and polymorphism. Polymer (Guildf) 2018, 149, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satthiyaraju, M.; Ramesh, T. Effect of annealing treatment on PVDF nanofibers for mechanical energy harvesting applications. Mater Res Express 2019, 6, 105366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniasadi, M.; et al. Correlation of annealing temperature, morphology, and electro-mechanical properties of electrospun piezoelectric nanofibers. Polymer (Guildf) 2017, 127, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lim, S. Self-poled and transparent polyvinylidene fluoride- co -hexafluoropropylene-based piezoelectric devices for printable and flexible electronics. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 4581–4590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusty, M.; Shirage, P.M. Insights and perspectives on graphene-PVDF based nanocomposite materials for harvesting mechanical energy. J Alloys Compd 2022, 904, 164060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, E.; Lund, A.; Jonasson, C.; Johansson, C.; Hagström, B. Poling and characterization of piezoelectric polymer fibers for use in textile sensors. Sens Actuators A Phys 2013, 201, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Hu, X.; Xiang, Y. In-situ polarization enhanced piezoelectric property of polyvinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene films. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci 2021, 770, 012071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadeva, S.K.; Berring, J.; Walus, K.; Stoeber, B. Effect of poling time and grid voltage on phase transition and piezoelectricity of poly(vinyledene fluoride) thin films using corona poling. J Phys D Appl Phys 2013, 46, 285305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasperini, L.; Selleri, G.; Pegoraro, D.; Fabiani, D. Corona poling for polarization of nanofibrous mats: advantages and open issues. in 2022 IEEE Conference on Electrical Insulation and Dielectric Phenomena (CEIDP), IEEE, Oct. 2022, 479–482. [CrossRef]

- Rui, G.; et al. Giant spontaneous polarization for enhanced ferroelectric properties of biaxially oriented poly(vinylidene fluoride) by mobile oriented amorphous fractions. J Mater Chem C Mater 2021, 9, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, T.; Chen, X.; Langhe, D.; Ponting, M.; Baer, E.; Zhu, L. Enhancing breakdown strength and lifetime of multilayer dielectric films by using high temperature polycarbonate skin layers. Energy Storage Mater 2022, 45, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, J.; Nunes, J.S.; Sencadas, V.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Influence of the β-phase content and degree of crystallinity on the piezo- and ferroelectric properties of poly(vinylidene fluoride). Smart Mater Struct 2010, 19, 065010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.Z.; et al. A high-performance soft actuator based on a poly(vinylidene fluoride) piezoelectric bimorph. Smart Mater Struct 2019, 28, 055011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; et al. Investigation on in-situ sprayed, annealed and corona poled PVDF-TrFE coatings for guided wave-based structural health monitoring: From crystallization to piezoelectricity. Mater Des 2021, 199, 109415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, C.; Améduri, B. Iodine transfer copolymerization of vinylidene fluoride and α-trifluoromethacrylic acid in emulsion process without any surfactants. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem 2009, 47, 4710–4722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbrent, S.; Plestil, J.; Hlavata, D.; Lindgren, J.; Tegenfeldt, J.; Wendsjö, Å. Crystallinity and morphology of PVdF–HFP-based gel electrolytes. Polymer (Guildf) 2001, 42, 1407–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wang, R.; Cao, Y. Effect of the rheology of poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluropropylene) (PVDF–HFP) dope solutions on the formation of microporous hollow fibers used as membrane contactors. J Memb Sci 2009, 344, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wu, Y. Influence of extrusion, stretching and poling on the structural and piezoelectric properties of poly (vinylidene fluoride-hexafluoropropylene) copolymer films. J Appl Polym Sci 2007, 104, 858–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, P.; Lopes, A.C.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Electroactive phases of poly(vinylidene fluoride): Determination, processing and applications. Prog Polym Sci 2014, 39, 683–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, Z.-Y. Electromechanical properties of poly(vinylidene-fluoride-chlorotrifluoroethylene) copolymer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 88, 062904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, F.; Yuan, Z.; Shu, E.W.; Zhu, L. Fast discharge speed in poly(vinylidene fluoride) graft copolymer dielectric films achieved by confined ferroelectricity. Appl Phys Lett 2009, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooti, A.; et al. Magnetic and high-dielectric-constant nanoparticle polymer tri-composites for sensor applications. J Mater Sci 2020, 55, 16234–16246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, T.; D’Souza, N.; Berman, D. Electrospun Fe3O4-PVDF Nanofiber Composite Mats for Cryogenic Magnetic Sensor Applications. Textiles 2021, 1, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, P.; et al. Case Study of Polyvinylidene Fluoride Doping by Carbon Nanotubes. Materials 2021, 14, 1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolmaleki, H.; Agarwala, S. PVDF-BaTiO3 Nanocomposite Inkjet Inks with Enhanced β-Phase Crystallinity for Printed Electronics. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arularasu, M.V.; Harb, M.; Vignesh, R.; Rajendran, T.V.; Sundaram, R. PVDF/ZnO hybrid nanocomposite applied as a resistive humidity sensor. Surfaces and Interfaces 2020, 21, 100780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naz, S.; Zameer, A.; Raja, M.A.Z.; Muhammad, K. Weighted differential evolution heuristics for improved multilayer piezoelectric transducer design. Appl Soft Comput 2021, 113, 107835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, J.R.; Samal, S.K.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)/Ag@TiO2 nanocomposite membrane with enhanced fouling resistance and antibacterial performance. Mater Chem Phys 2021, 268, 124723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.C.; Costa, C.M.; Tavares, C.J.; Neves, I.C.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Nucleation of the Electroactive γ Phase and Enhancement of the Optical Transparency in Low Filler Content Poly(vinylidene)/Clay Nanocomposites. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2011, 115, 18076–18082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Duan, X.; Xie, M.; Aw, K.C.; Xue, Q. Composites, Fabrication and Application of Polyvinylidene Fluoride for Flexible Electromechanical Devices: A Review. Micromachines (Basel) 2020, 11, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachin, M.; Haridass, R.; Ramanujam, B.T.S. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF)-poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)-expanded graphite (ExGr) conducting polymer blends: Analysis of electrical and thermal behavior. Mater Today Proc 2020, 28, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontes, K.; Indrusiak, T.; Soares, B.G. Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluorpropylene)/polyaniline conductive blends: Effect of the mixing procedure on the electrical properties and electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness. J Appl Polym Sci 2021, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gu, X.; Ni, C.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; You, J. Improvement of PLLA Ductility by Blending with PVDF: Localization of Compatibilizers at Interface and Its Glycidyl Methacrylate Content Dependency. Polymers (Basel) 2020, 12, 1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudman, D.; Weizman, O.; Amir, E.; Ophir, A. Development and characterization of expanded graphite filled-PET/PVDF blend: thermodynamic and kinetic effects. Polym Adv Technol 2017, 28, 590–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaabour, L.H.; Hamam, K.A. The Change of Structural, Optical and Thermal Properties of a PVDF/PVC Blend Containing ZnO Nanoparticles. Silicon 2018, 10, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallaiah, Y.; Jeedi, V.R.; Swarnalatha, R.; Raju, A.; Reddy, S.N.; Chary, A.S. Impact of polymer blending on ionic conduction mechanism and dielectric properties of sodium based PEO-PVdF solid polymer electrolyte systems. Journal of Physics and Chemistry of Solids 2021, 155, 110096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.M.; Nasr, R.A. Structural characterization of <scp>PVDF</scp> / <scp>PVA</scp> polymer blend film doped with different concentration of <scp>NiO NPs</scp> for photocatalytic degradation of malachite green dye under visible light. J Appl Polym Sci 2022, 139, 51847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, C.V.S.; Zhu, Q.-Y.; Mai, L.-Q.; Chen, W. Electrochemical studies on PVC/PVdF blend-based polymer electrolytes. Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry 2007, 11, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; et al. Polyamide 11/Poly(vinylidene fluoride) Blends as Novel Flexible Materials for Capacitors. Macromol Rapid Commun 2008, 29, 1449–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbe, S.S.; Joshi, G.M.; Deshmukh, R.R.; Dhanumalayan, E.; Kaleemulla, S. Improved under damped oscillator properties of polymer blends for electronic applications. Mech Time Depend Mater 2022, 26, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Lamnawar, K.; Maazouz, A.; Zhang, H. Revealing the dynamic heterogeneity of PMMA/PVDF blends: from microscopic dynamics to macroscopic properties. Soft Matter 2016, 12, 3252–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, A.; Sawada, H.; Kojima, Y. Application of Poly(vinylidene fluoride) and Poly(methyl methacrylate) Blends to Optical Material. Polym J 1990, 22, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; et al. Preparation of PVDF based blend microporous membranes for lithium ion batteries by thermally induced phase separation: I. Effect of PMMA on the membrane formation process and the properties. J Memb Sci 2013, 444, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guselnikova, O.; Svanda, J.; Postnikov, P.; Kalachyova, Y.; Svorcik, V.; Lyutakov, O. Fast and Reproducible Wettability Switching on Functionalized PVDF/PMMA Surface Controlled by External Electric Field. Adv Mater Interfaces 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, P.; Ghosh, A.; Bose, N.; Mukherjee, S.; Chowdhury, A.R.; Datta, P. A comparative assessment of poly(vinylidene fluoride)/conducting polymer electrospun nanofiber membranes for biomedical applications. J Appl Polym Sci 2020, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.N.; Kersch, M.; Altstädt, V.; Oliveira, R.V.B. Electrical conductivity of poly(vinylidene fluoride)/polyaniline blends under oscillatory and steady shear conditions. Polym Test 2013, 32, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Shen, Y.; Shen, Z.; Jiang, J.; Chen, L.; Nan, C.-W. Achieving High Energy Density in PVDF-Based Polymer Blends: Suppression of Early Polarization Saturation and Enhancement of Breakdown Strength. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2016, 8, 27236–27242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.K. Handbook of Materials Characterization. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Jeedi, V.R.; Narsaiah, E.L.; Yalla, M.; Swarnalatha, R.; Reddy, S.N.; Chary, A.S. Structural and electrical studies of PMMA and PVdF based blend polymer electrolyte. SN Appl Sci 2020, 2, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deeba, F.; Gupta, A.K.; Kulshrestha, V.; Bafna, M.; Jain, A. Investigations on dielectric properties of PVDF/PMMA blends. Mater Today Proc 2022, 66, 3547–3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Sahoo, R.; Unnikrishnan, L.; Ramadoss, A.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Enhanced structural and dielectric behaviour of PVDF-PLA binary polymeric blend system. Mater Today Commun 2021, 26, 101958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Hakukawa, H.; Yamahira, N.; Li, Y.; Horiuchi, S. Mechanism of Reactive Compatibilization of PLLA/PVDF Blends Investigated by Scanning Transmission Electron Microscopy with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectrometry and Electron Energy Loss Spectroscopy. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2019, 1, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, D.M.; et al. Influence of Cation and Anion Type on the Formation of the Electroactive β-Phase and Thermal and Dynamic Mechanical Properties of Poly(vinylidene fluoride)/Ionic Liquids Blends. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2019, 123, 27917–27926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, K.; et al. Preparation and properties of polyvinylidene fluoride dielectric nanocomposites for energy storage applications through synergistic addition of ionic liquid-modified graphene oxide nanosheets and functionalized barium titanate hybrid fillers. Polym Compos 2024, 45, 7102–7115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepelin, N.A.; et al. New developments in composites, copolymer technologies and processing techniques for flexible fluoropolymer piezoelectric generators for efficient energy harvesting. Royal Society of Chemistry 2019, 12, 1143–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; et al. Enhanced piezoelectricity from highly polarizable oriented amorphous fractions in biaxially oriented poly(vinylidene fluoride) with pure β crystals. Nat Commun 2021, 12, 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.-Y.; et al. Enhanced Dielectric and Ferroelectric Properties of Poly(vinylidene fluoride) through Annealing Oriented Crystallites under High Pressure. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 2014–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilla, K.; Neergat, M.; Jonnalagadda, K.N. Strain and temperature induced phase changes in <scp>spin-coated PVDF</scp> thin films. Journal of Polymer Science 2023, 61, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullaveettil, F.N.; Dauksevicius, R.; Wakjira, Y. Strength and elastic properties of 3D printed PVDF-based parts for lightweight biomedical applications. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 2021, 120, 104603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

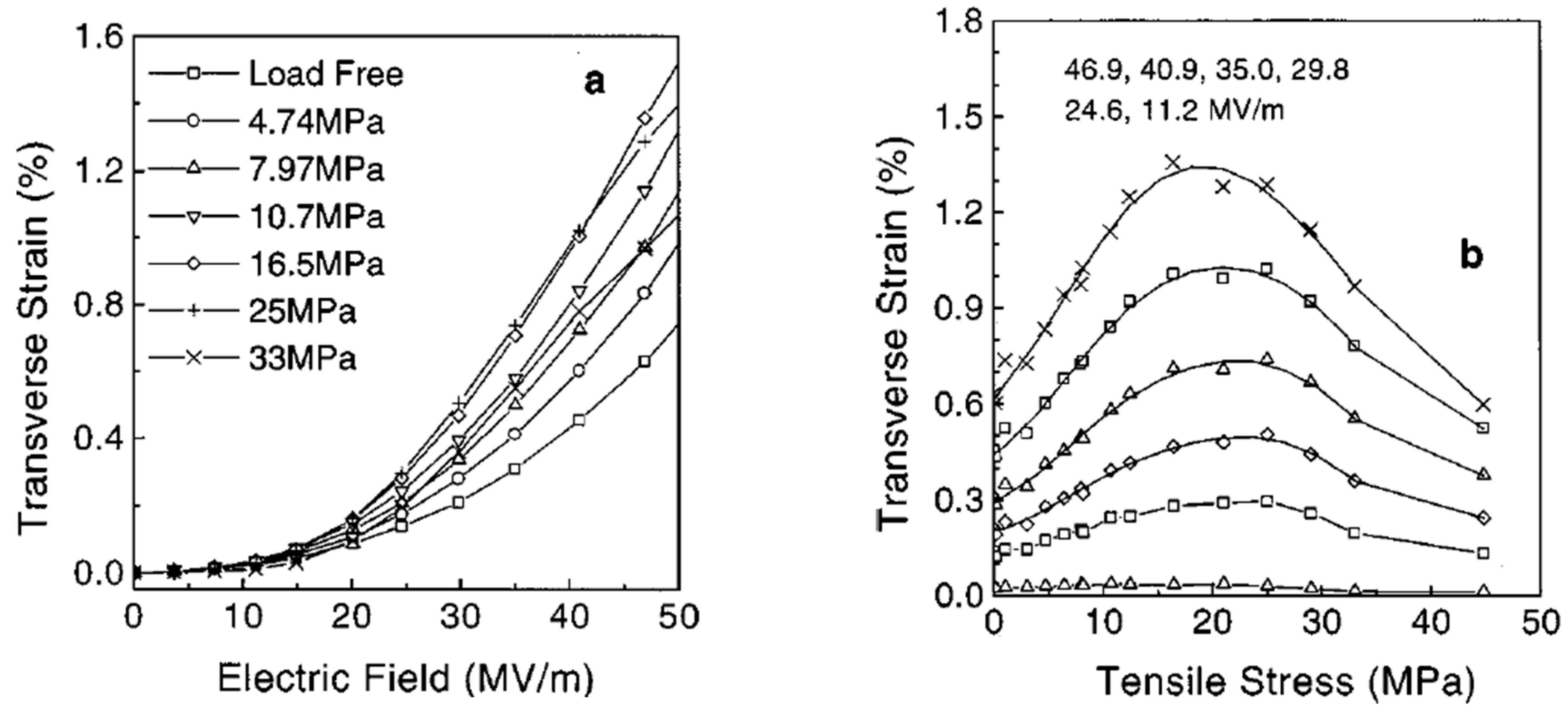

- Cheng, Z.-Y.; Xu, T.-B.; Bharti, V.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q.M. Transverse strain responses in the electrostrictive poly(vinylidene fluoride–trifluorethylene) copolymer. Appl Phys Lett 1999, 74, 1901–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, Q.Z.Q.; Cross, L.E.C.L.E. A High Sensitivity, Phase Sensitive d 33 Meter for Complex Piezoelectric Constant Measurement. Jpn J Appl Phys 1993, 32, L1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; et al. A Tough and Self-Powered Hydrogel for Artificial Skin. Chemistry of Materials 2019, 31, 9850–9860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghayari, S. PVDF composite nanofibers applications. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiujuan, F.; Longbiao, H.; Triantafillos, K.; Feng, N.; Bo, Z.; Ping, Y. Comparison between methods for the measurement of the D33 constant of piezoelectric materials COMPARISON BETWEEN METHODS FOR THE MEASURE-MENT OF THE D 33 CONSTANT OF PIEZOELECTRIC MATE-RIALS. 2018. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/326274919.

- Chen, X.; et al. Giant Electrostriction Enabled by Defect-Induced Critical Phenomena in Relaxor Ferroelectric Polymers. Macromolecules 2023, 56, 690–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; et al. Relaxor ferroelectric polymer exhibits ultrahigh electromechanical coupling at low electric field. Science (1979) 2022, 375, 1418–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

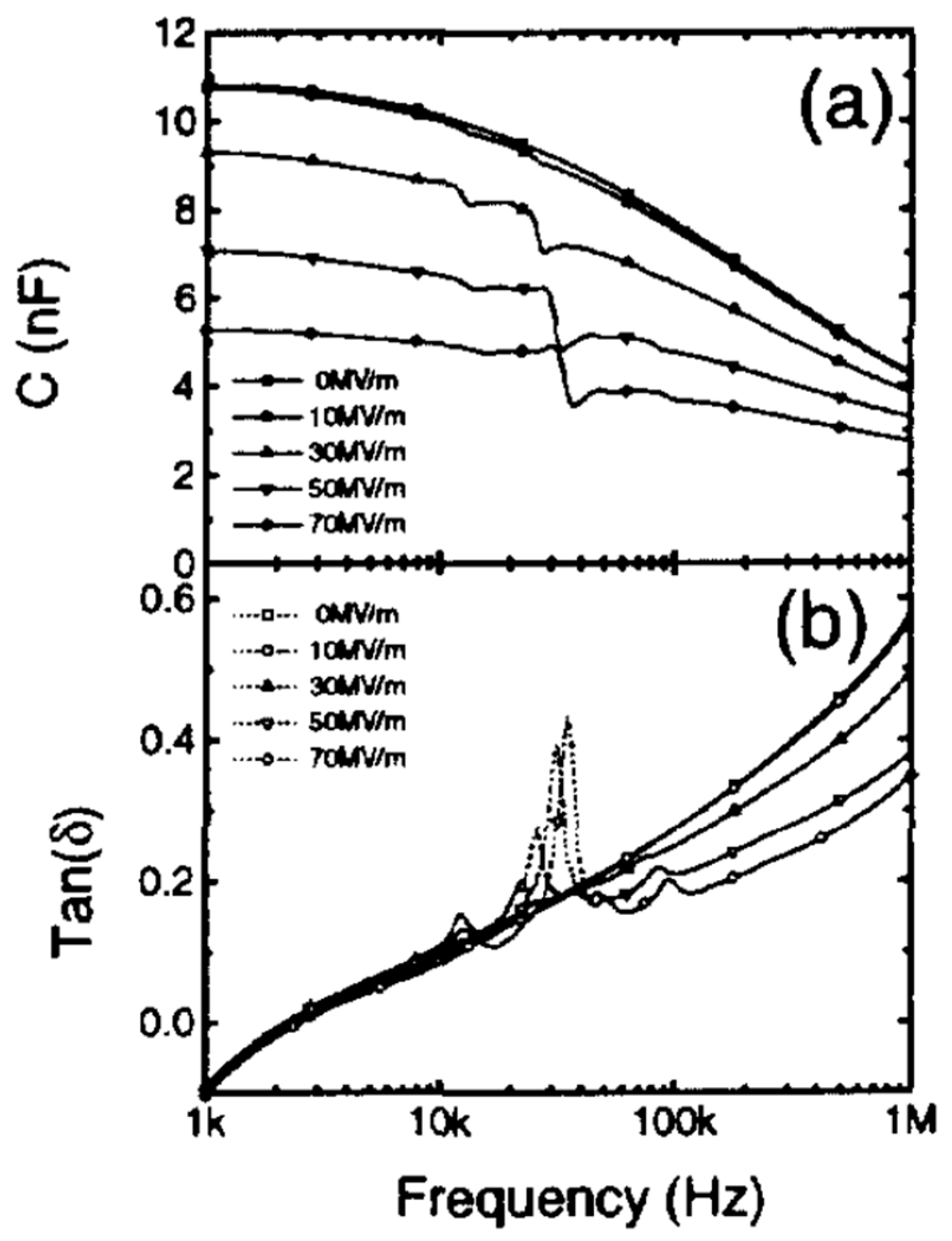

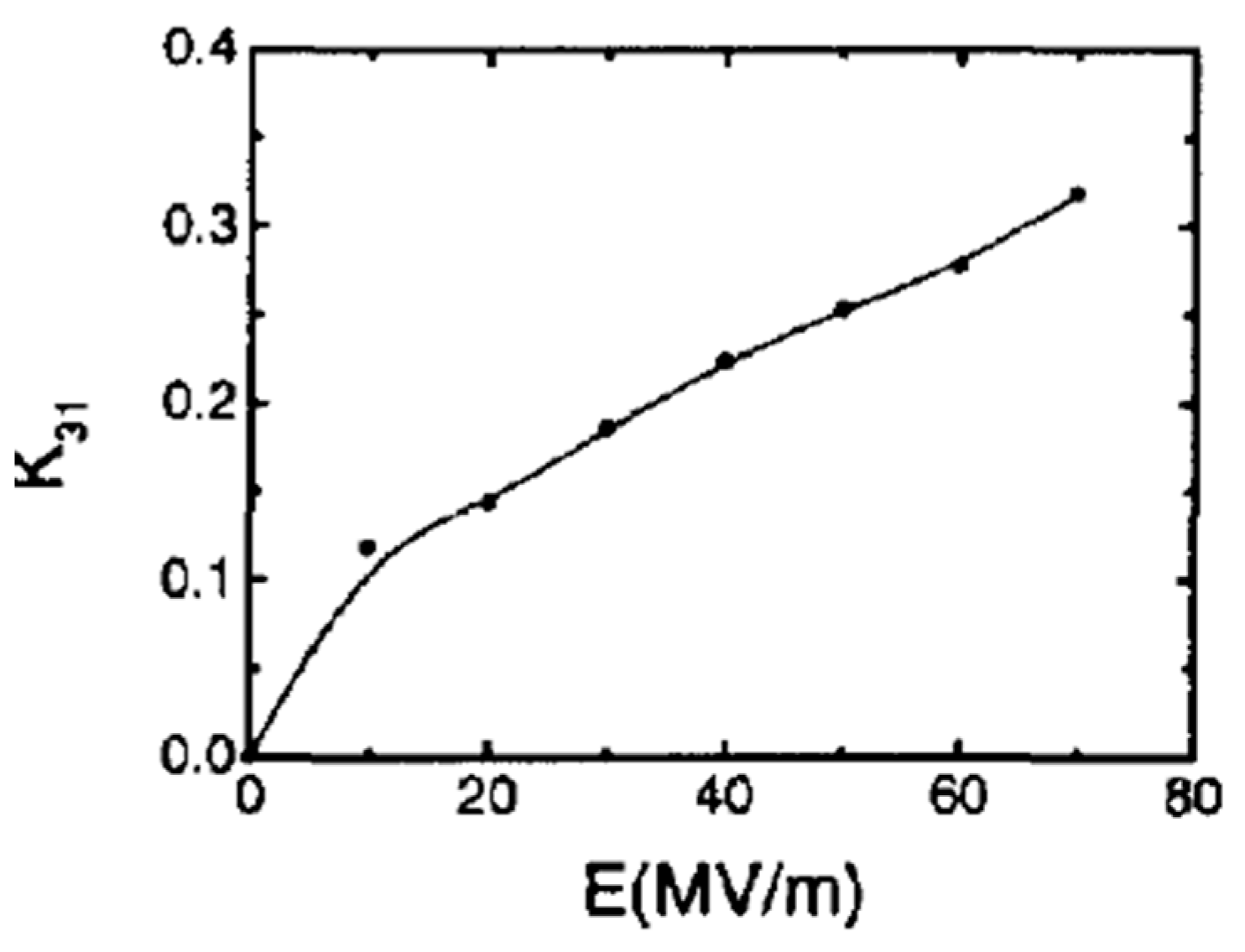

- Cheng, Z.-Y.; et al. Transverse strain responses in electrostrictive poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) films and development of a dilatometer for the measurement. J Appl Phys 1999, 86, 2208–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.-B. Development of Electromechanical Devices based on Newly Developed Electroactive P(VDF-TrFE) polymer. The Pennsylvania State University, 2002. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/9c2f4d8b211aa359eb7c083a1a7f95ad/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Xu, T.-B.; Cheng, Z.-Y.; Mai, T.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.M. Electromechanical coupling factor of electrostrictive P(VDF-TrFE) copolymer. in 2000 IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium. Proceedings. An International Symposium (Cat. No.00CH37121), IEEE, 997–1000. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; et al. Studies on the electrostatic effects of stretched PVDF films and nanofibers. Nanoscale Res Lett 2021, 16, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Properties | Parameters | PVDF example values |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | Density (g/cm³) | 1.78 |

| Material color | transparent resin without color | |

| Water absorption % | 0.02 - 0.07 | |

| Refraction Index (ND) | 1.40 - 1.42 | |

| Oxygen Index (%) | 42 - 44 | |

| Mechanical | Tensile strength @ 23°C (MPa) | 35–55 |

| Hardness, Shore D | 50 - 80 | |

| Young’s modulus @ 23°C (MPa) | 1340–2000 | |

| Permittivity of free space(F/m) | ε0= 8.854*10-12 | |

| Elastic constant N/m2 | C11 =2.184*109 C12=0.633*109 |

|

| Piezoelectric | Curie temperature 80°C Strain constant d (10-12 C/N) |

d31 = 20–30 d33 = -30 |

| Stress constant (10-3 mV/N) | g33=335 | |

| Volume resistivity (Ω – cm) | 1015 -2.0 × 1014 | |

| Thermal | Melting Point °C | 177 |

| Defection temperature °C(261 psi) | 114–118 | |

| Flammability | V-O | |

| Thermal expansion coefficient(μm/m-°C) | 10-4 | |

| Decomposition Temp (°C) | 375 | |

| Thermal Conductivity (W/m - K) | 0.144 - 0.2 | |

| Glass transition temperature, °C | −35 | |

| Flammability°C | V-O |

| Chemical properties of PVDF | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organic solvent resistance | Alcohol resistance | ||||

| Chemical | 20°C | 50°C | Chemical | 20 °C | 50 °C |

| Acetone | Not | Not | Benzyl alcohol (pure) | Yes | Yes |

| Chlorobenzene | Yes | Yes | Methanol | Yes | Yes |

| Benzene | Yes | Limited | Ethanol (30%) | Yes | Yes |

| Chloroform | Yes | Yes | Methyl alcohol (10%) | Yes | Yes |

| Diethylene glycol | Yes | - | Phenol (10%) | Yes | Yes |

| Cyclohexane | Yes | Yes | Methyl alcohol (pure) | Yes | Yes |

| Dimethyl formamide | - | - | Propanol | Yes | Yes |

| Trichloroethane | Yes | Yes | Phenol (100% | Yes | Yes |

| Diethylamino | Yes | Not | Resistance to acids and bases | ||

| Xylol | Yes | yes | Formic acid (10%) | Yes | Yes |

| Food product resistance | Acetic acid (100%) | Yes | Yes | ||

| Glucose | Yes | Not | Acetic acid (10%) | Yes | Yes |

| Milk | Yes | Yes | Hydrochloric acid | Yes | Yes |

| Olive oil | Yes | Yes | Sulfuric acid (10%) | Yes | Yes |

| Wine | Yes | Yes | Lactic acid | Yes | Limited |

| Vinegar | Yes | Limited | Nitric acid (10%) | Yes | Yes |

| Resistance to oils and fats | Nitric acid (Conc.) | Limited | Limited | ||

| Coconut oil | Yes | Yes | Hydrogen peroxide (90%) | Yes | - |

| Butyl acetate | Yes | Limited | Sulfuric acid (90%) | Yes | Yes |

| Mineral oils | Yes | Yes | Sulfuric acid (fuming/monohydrate) |

Not | Not |

| Pine oil | Yes | Yes | Trichlorofluoromethane | Yes | Yes |

| Paraffin oil | Yes | Yes | Tetrahydrofuran | Limited | Not |

| Method | Advantages | Disadvantages | Common Prameter |

| Solution Casting |

|

|

Concentration: 10-20 wt% Temperature: 25-80°C |

| Hot pressing |

|

|

- |

| Electrospinning |

|

|

Voltage: 10-30 kV Flow rate: 0.5-2 mL/h |

| Spin Coating |

|

|

Speed: 1000-5000 rpm Time: 30-60 s |

| Solution Coating |

|

|

Concentration: 5-15 wt% Temperature: 25-60°C |

| 3D Printing |

|

|

Layer height: 0.1-0.4 mm Speed: 10-100 mm/s |

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Stretching[68,171] |

|

|

| Annealing Treatment [155,161] |

|

|

| Poling[9,172] |

|

|

| Polymer | Advantage | Applications |

| PVDF |

|

|

| Poly (VDF-co-TrFE) |

|

|

| Poly (VDF-co-HFP) |

|

|

| Poly (VDF-co-CTFE) |

|

|

| PVDF blend with polymers | Advantage | Applications | Ref |

| PVDF/PMMA | promotes the formation of the β-phase |

|

[207,208] |

| PLLA/PVDF | Improved biodegradability |

|

[209,210] |

| PVDF/ ILs | - |

|

[211,212] |

| Properties | Characterization methods | Determining parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal characterization | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Melting point, Glass transition temperature, Crystallization temperature. |

| Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) | Thermal stability, Degradation behavior. |

|

| Structural characterization | X-ray Diffraction (XRD) | Crystal phases (α, β, γ), Crystallinity percentage. |

| Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) | Characteristic peaks of various crystal phases. | |

| Mechanical characterization | Universal testing machine(UTM) | Tensile strength, Young's modulus, Elongation at break. |

| Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA) | Viscoelastic behavior, | |

| Electrical characterization | Dielectric Spectroscopy | Dielectric constant, Loss tangent over frequency. |

| Conductivity Measurements | Electrical conductivity. | |

| Dielectric | Impedance Analyzer | Dielectric constant, Loss tangent as a function of frequency. |

| Ferroelectric characterization | Ferroelectric Loop Tracer | Polarization-electric field (P-E) hysteresis loops. |

| Switching Spectroscopy | Domain switching dynamics. | |

| Electromechanical characterization | Strain Gauge | Strain generated by electric field. |

| Laser Interferometry | Displacement due to electric field. | |

| Piezoelectric characterization | d33 Meter | Piezoelectric charge coefficient (d33). |

| Piezo response Force Microscopy (PFM) | Piezoelectric domains, Piezoelectric coefficients. | |

| Pyroelectric characterization | Pyroelectric Current Meter | Pyroelectric current caused by temperature variation. |

| Electrocaloric Effect Measurements | Temperature change induced by electric field. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).