Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Catalyst Preparation

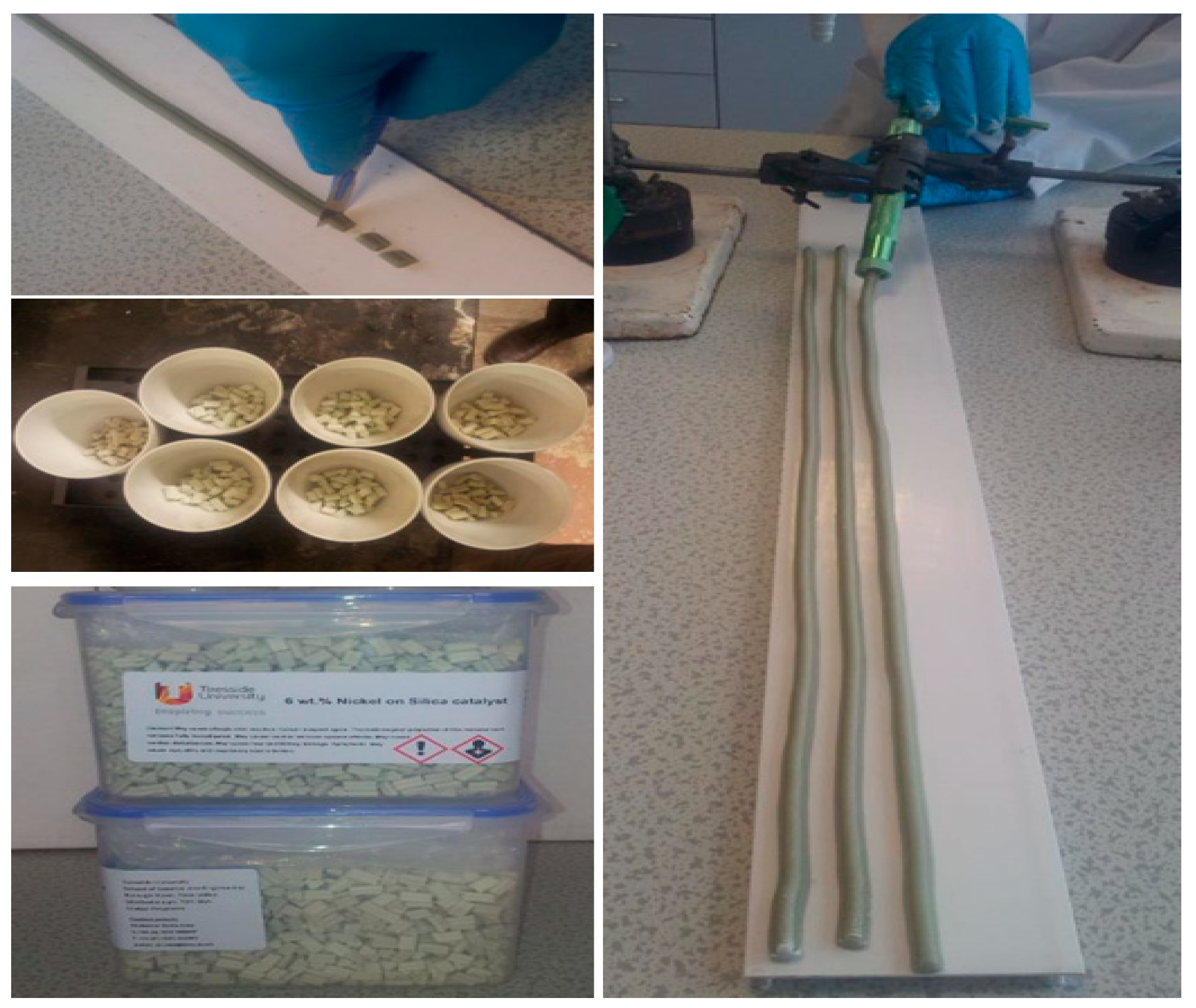

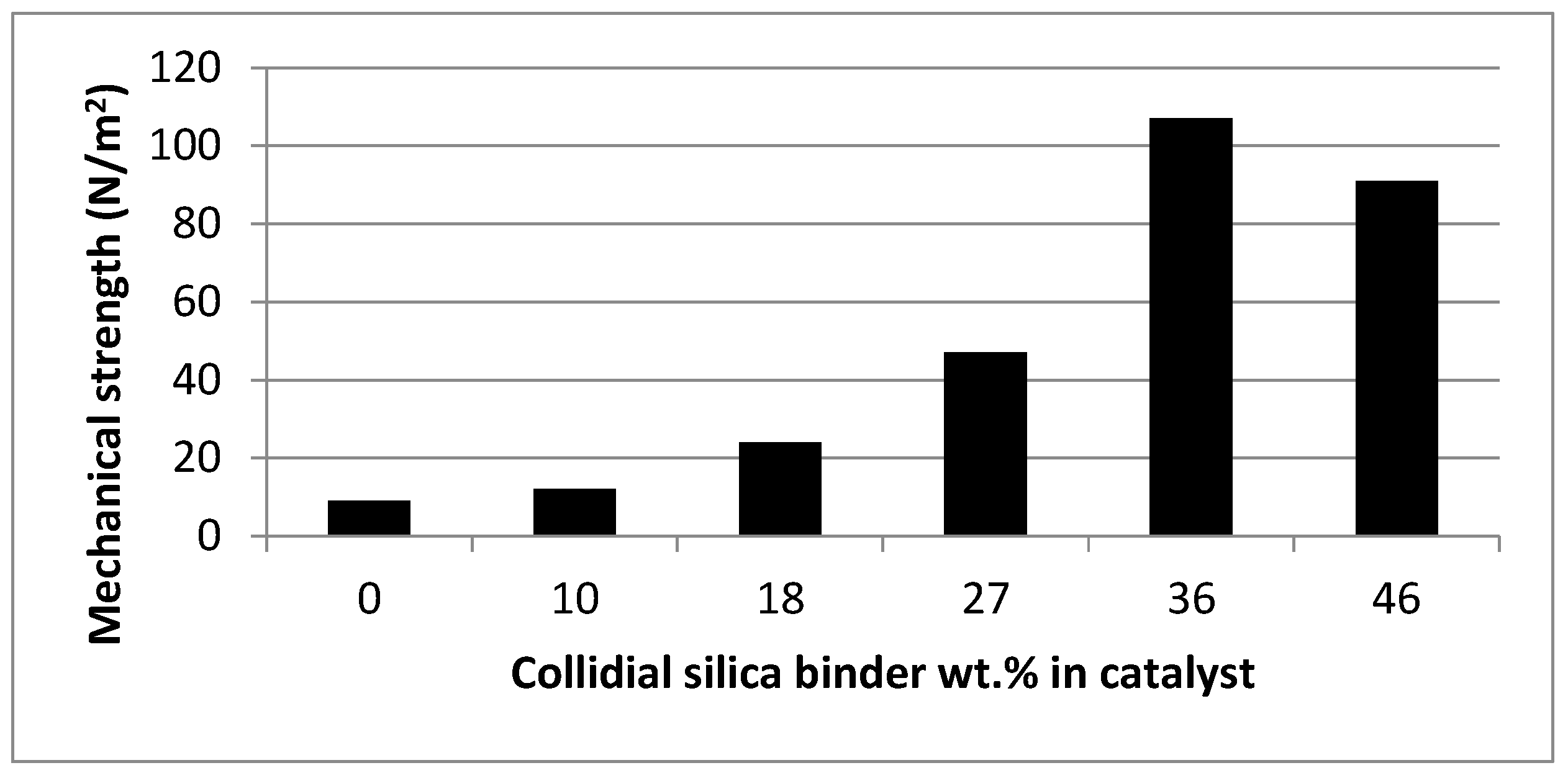

2.2. Preparation of Ni/SBA-15 Pellets

2.3. Characterisation of Prepared Catalyst Pellets

2.4. Single Pellet Mechanical Strength Test

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) Images

2.6. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) Images

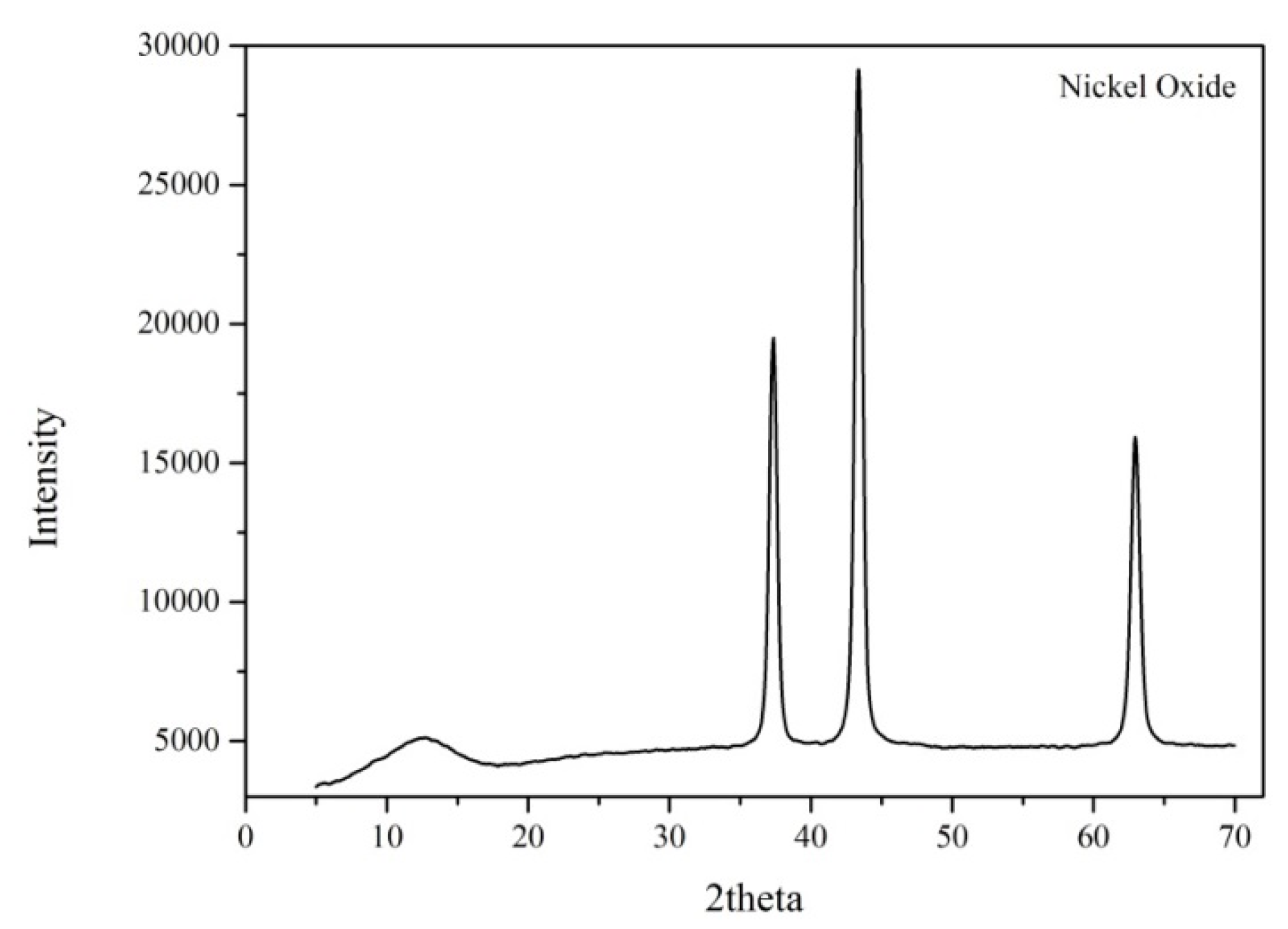

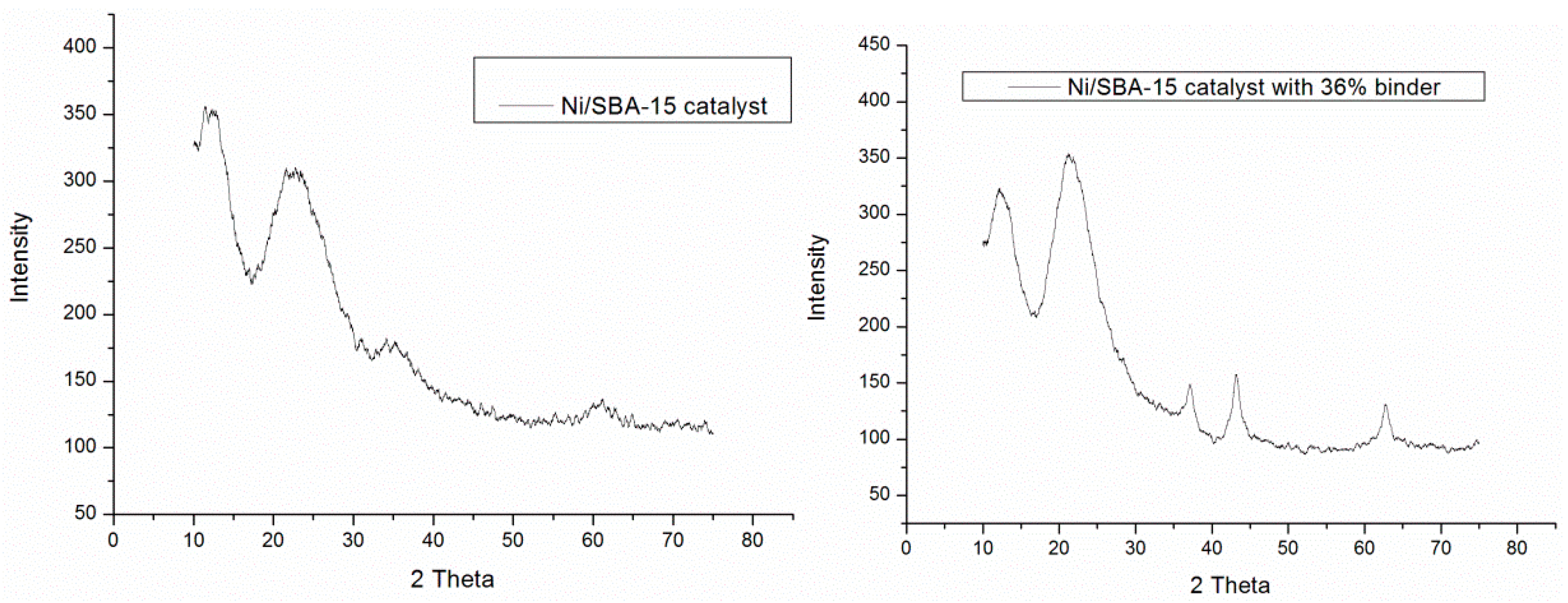

2.7. Wide Angle XRD

2.8. Physical Properties of the NiSBA-15 Catalyst

2.9. Temperature Programmed Reduction (TPR)

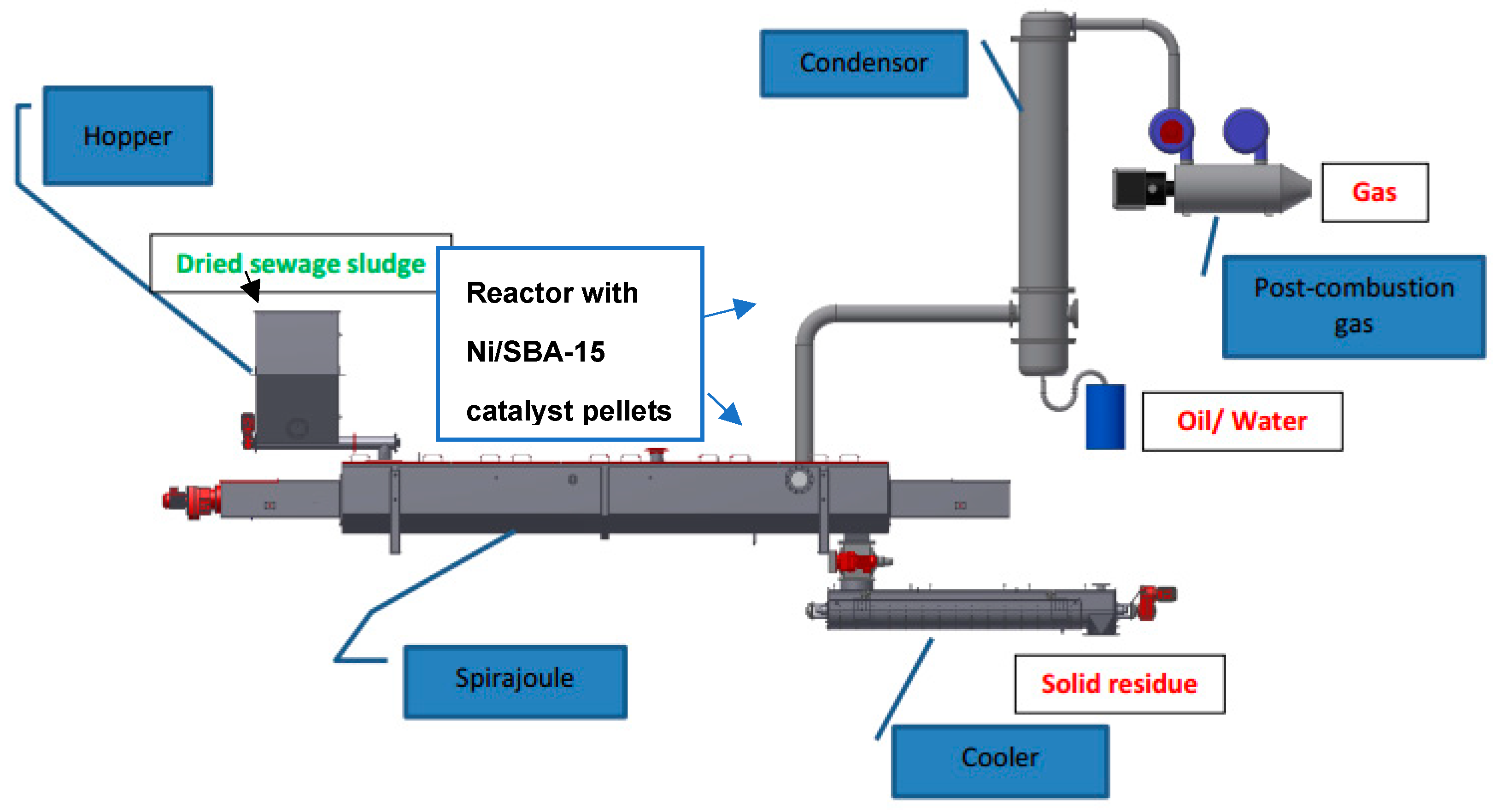

2.10. Pilot Plant Test Procedure

2.11. Analysis of Liquid and Gas Pyrolysis Fractions

2.12. Catalyst Characterisation

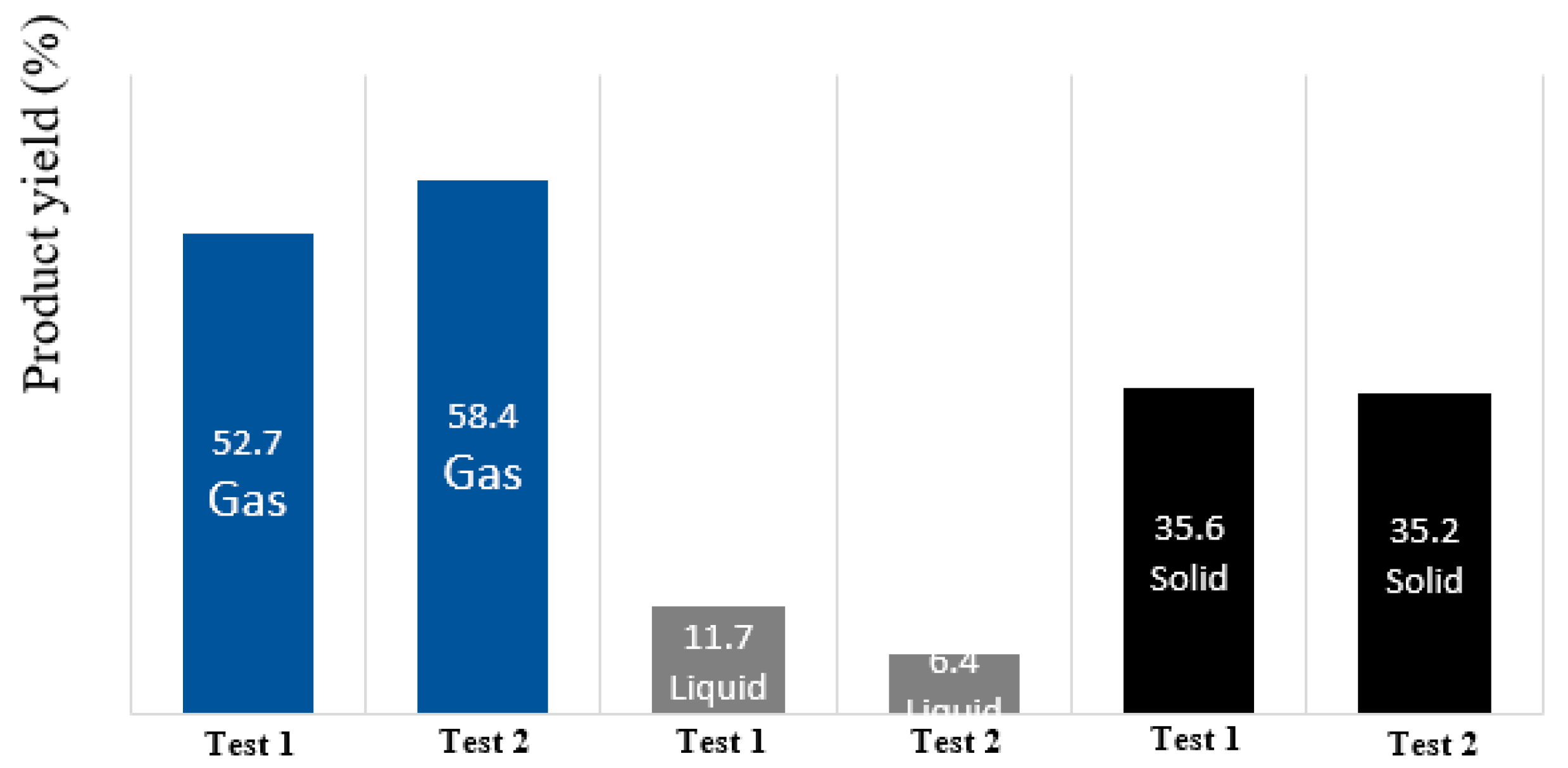

3. Pilot Plant Test Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterisation of Pyrolysis Liquid Fraction Without Catalytic Cracking

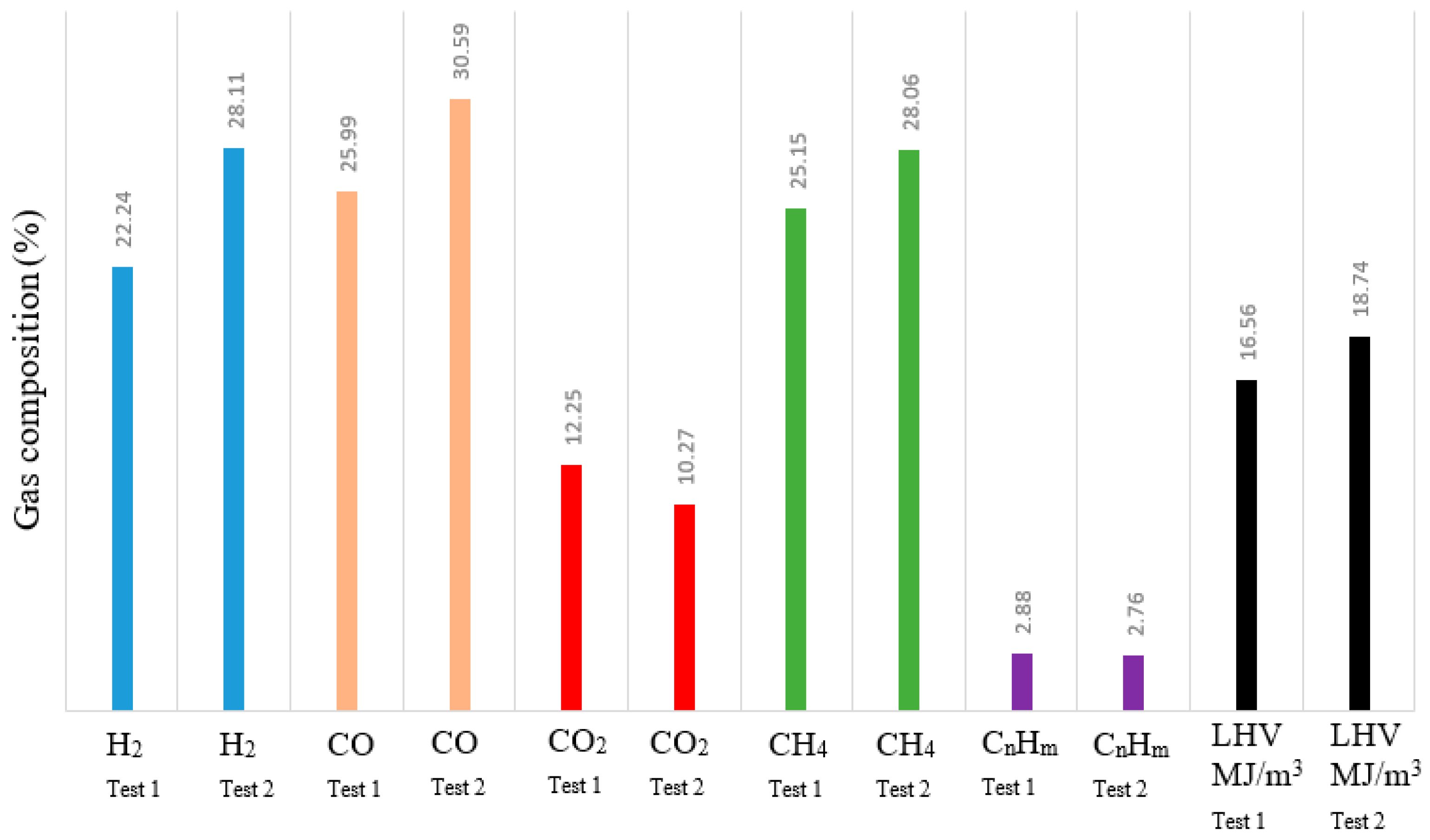

3.2. Pyrolysis Gas Composition

3.3. Characterisation of the Catalyst Before and After Reaction

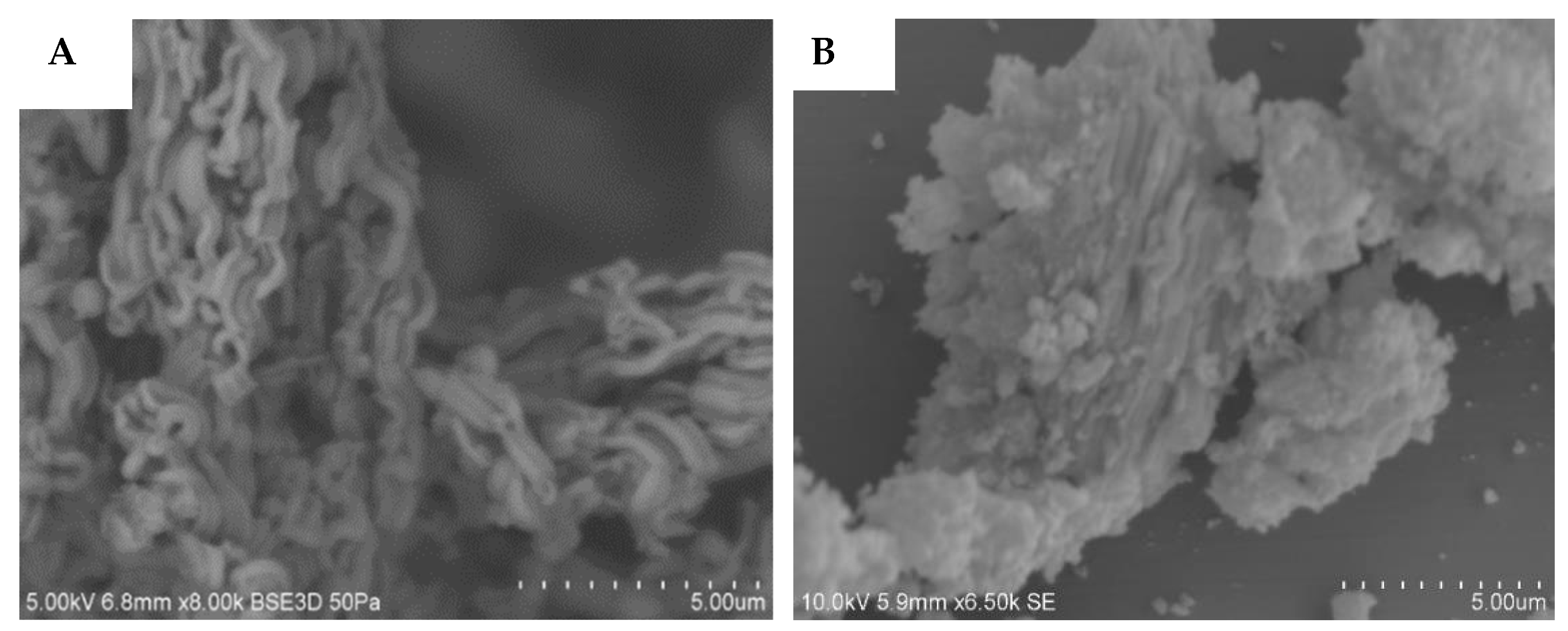

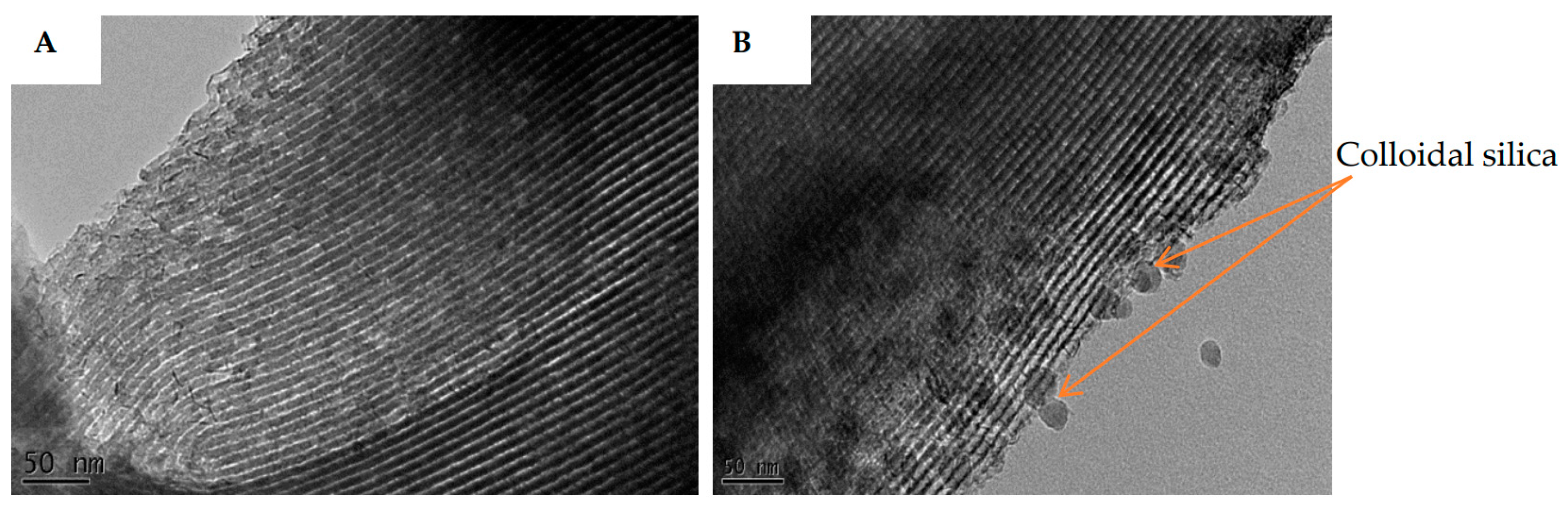

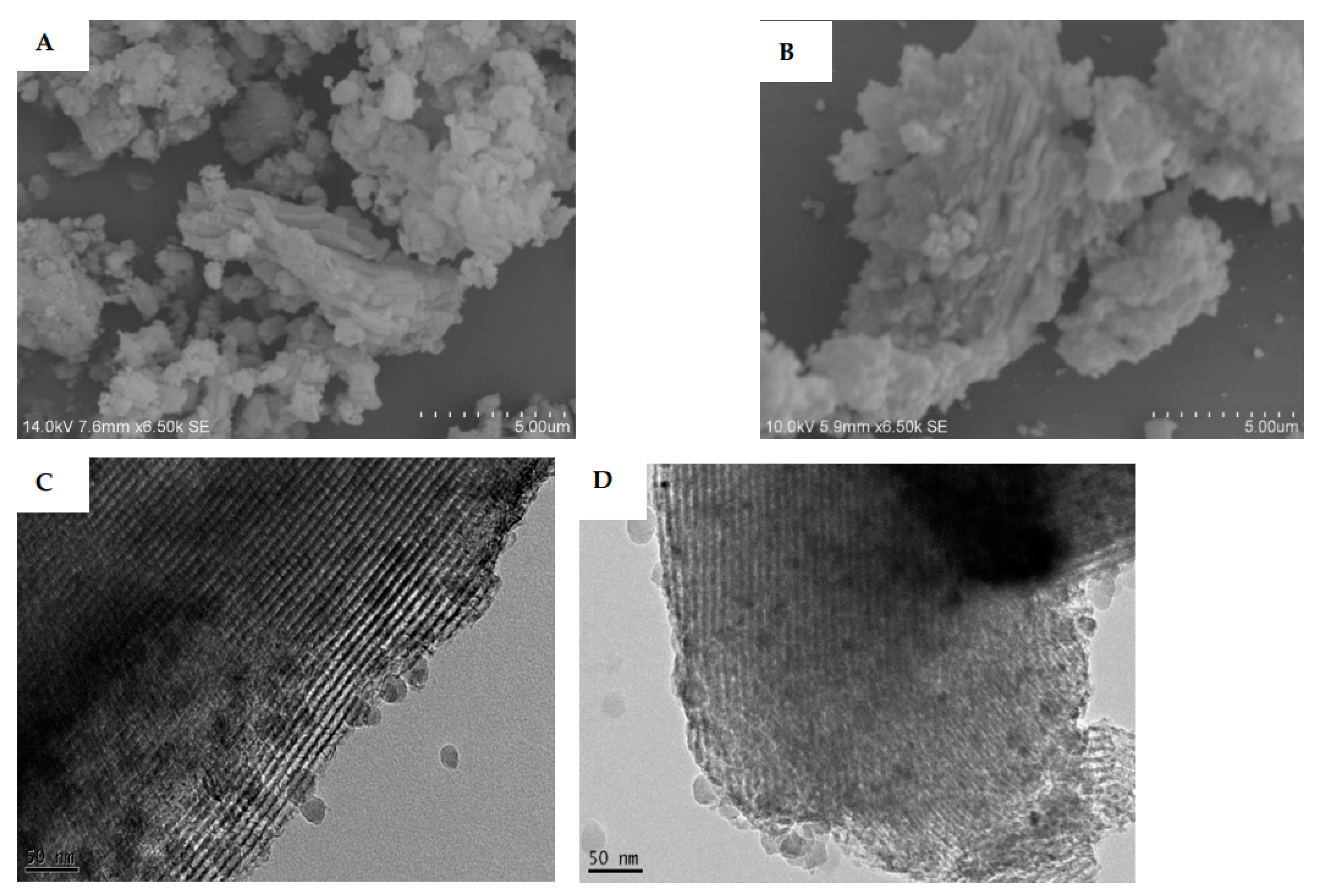

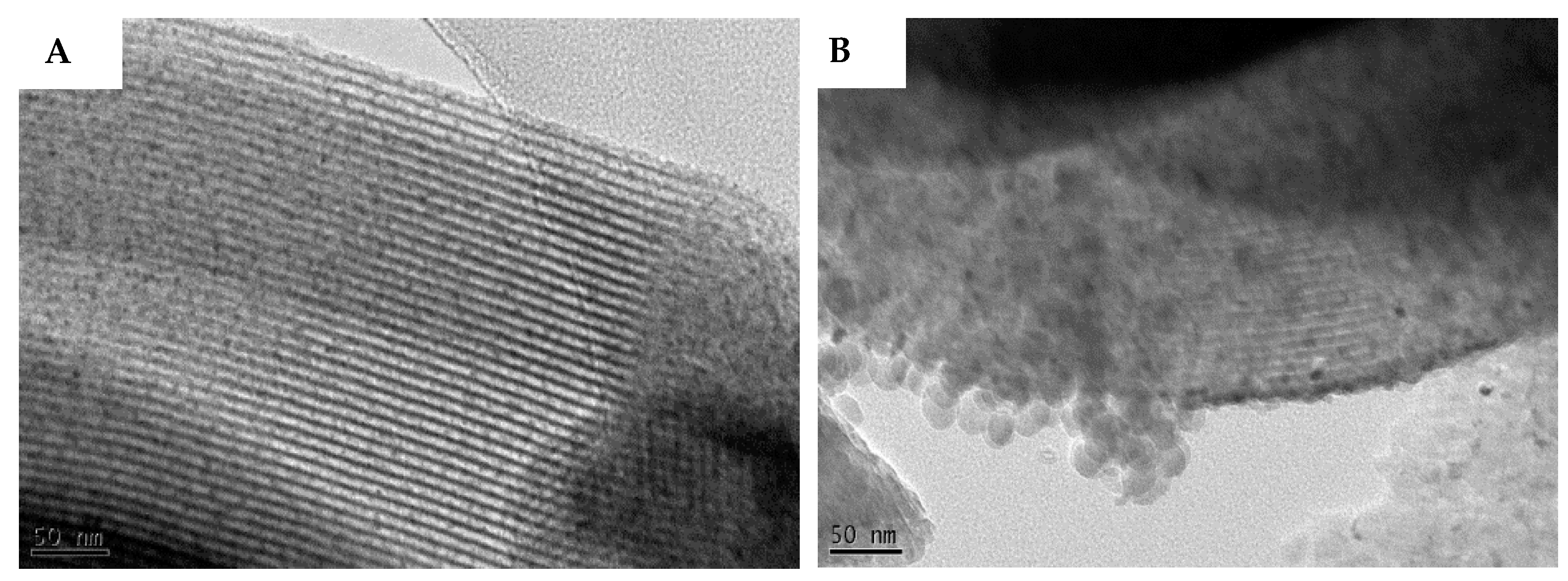

3.3.1. SEM and TEM Results

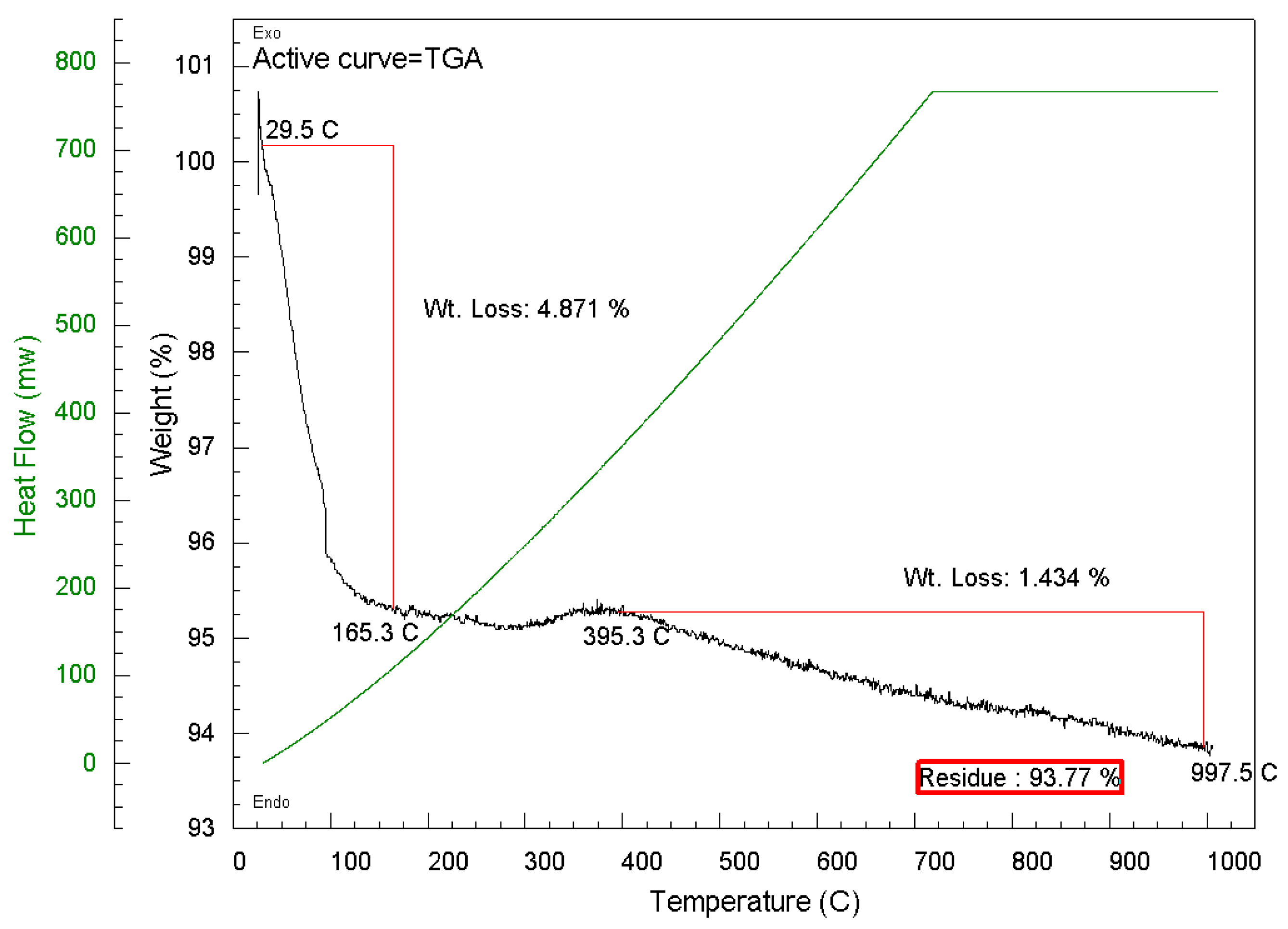

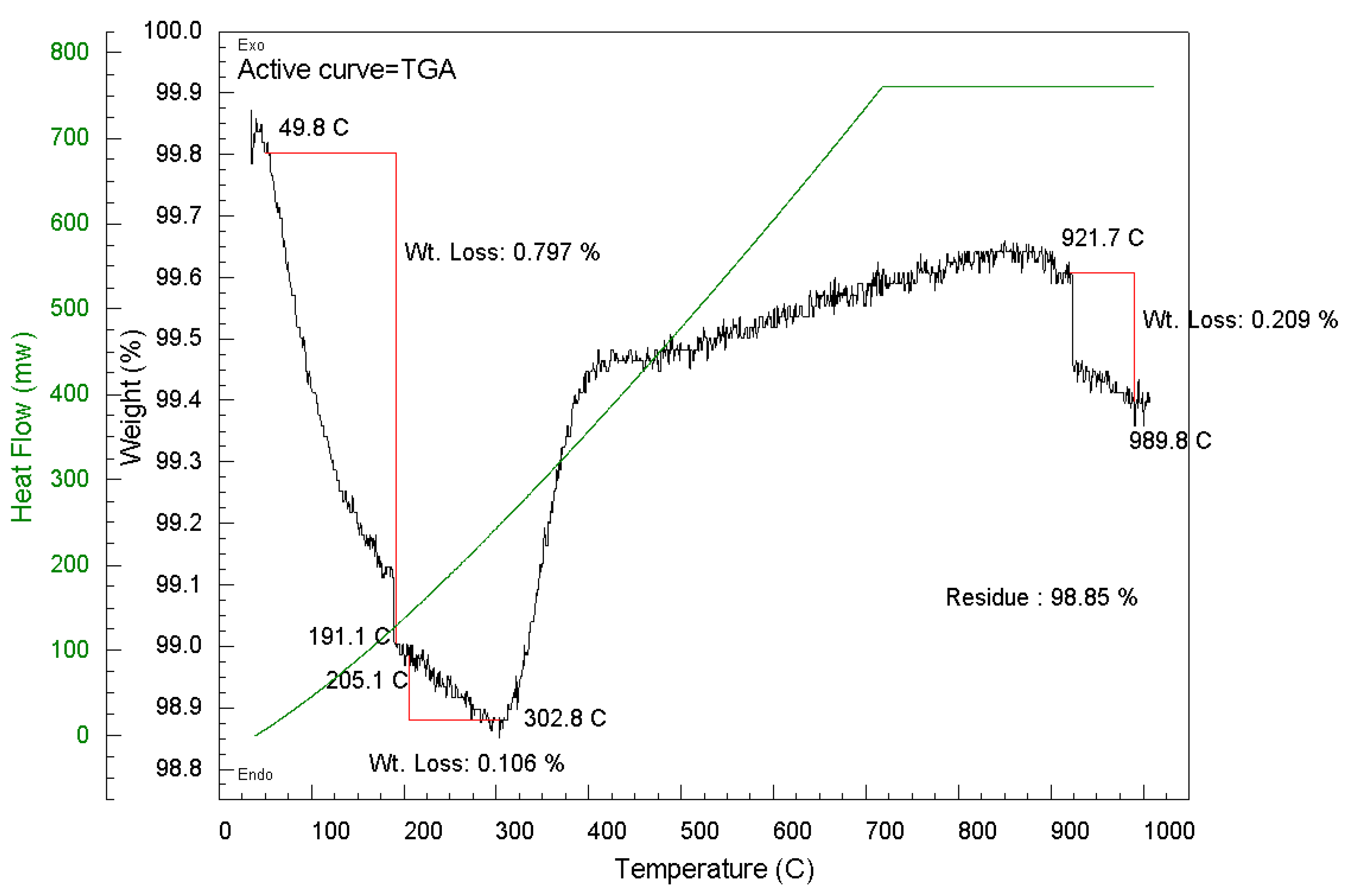

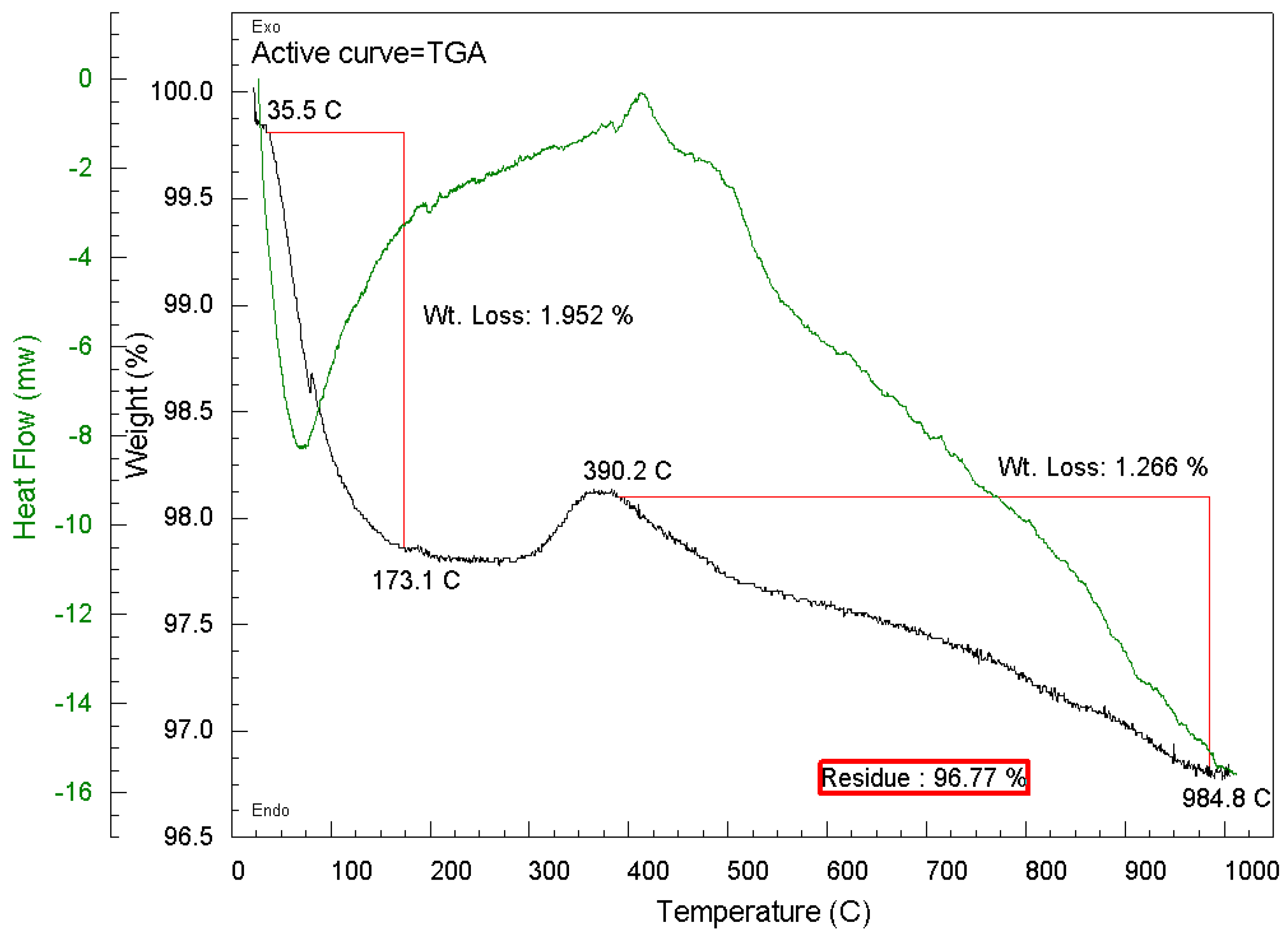

3.3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

4. Comparing the Catalytic Performance of Crushed Ni-SBA-15 Pellets with the Powered Ni-SBA-15 Catalyst Without Binder

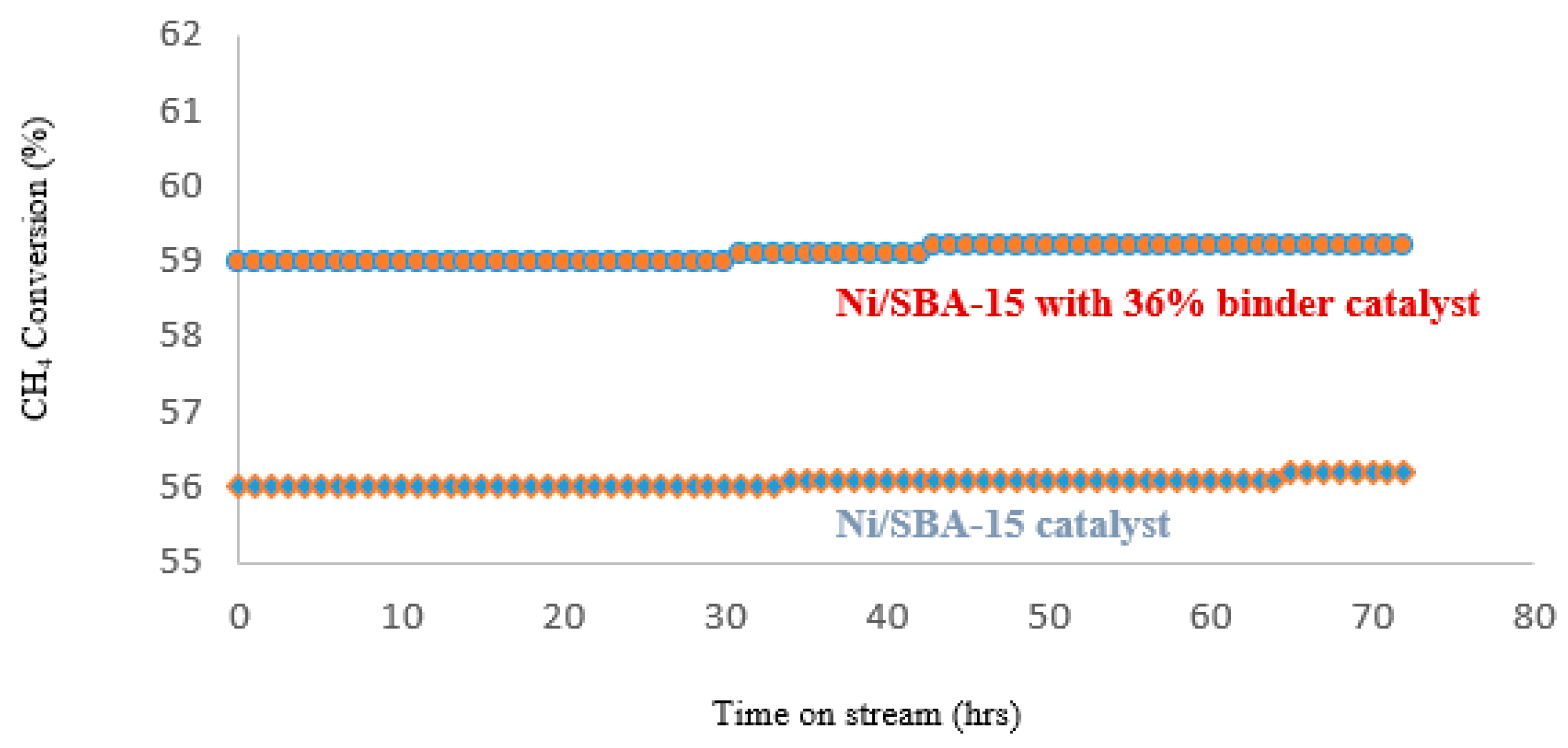

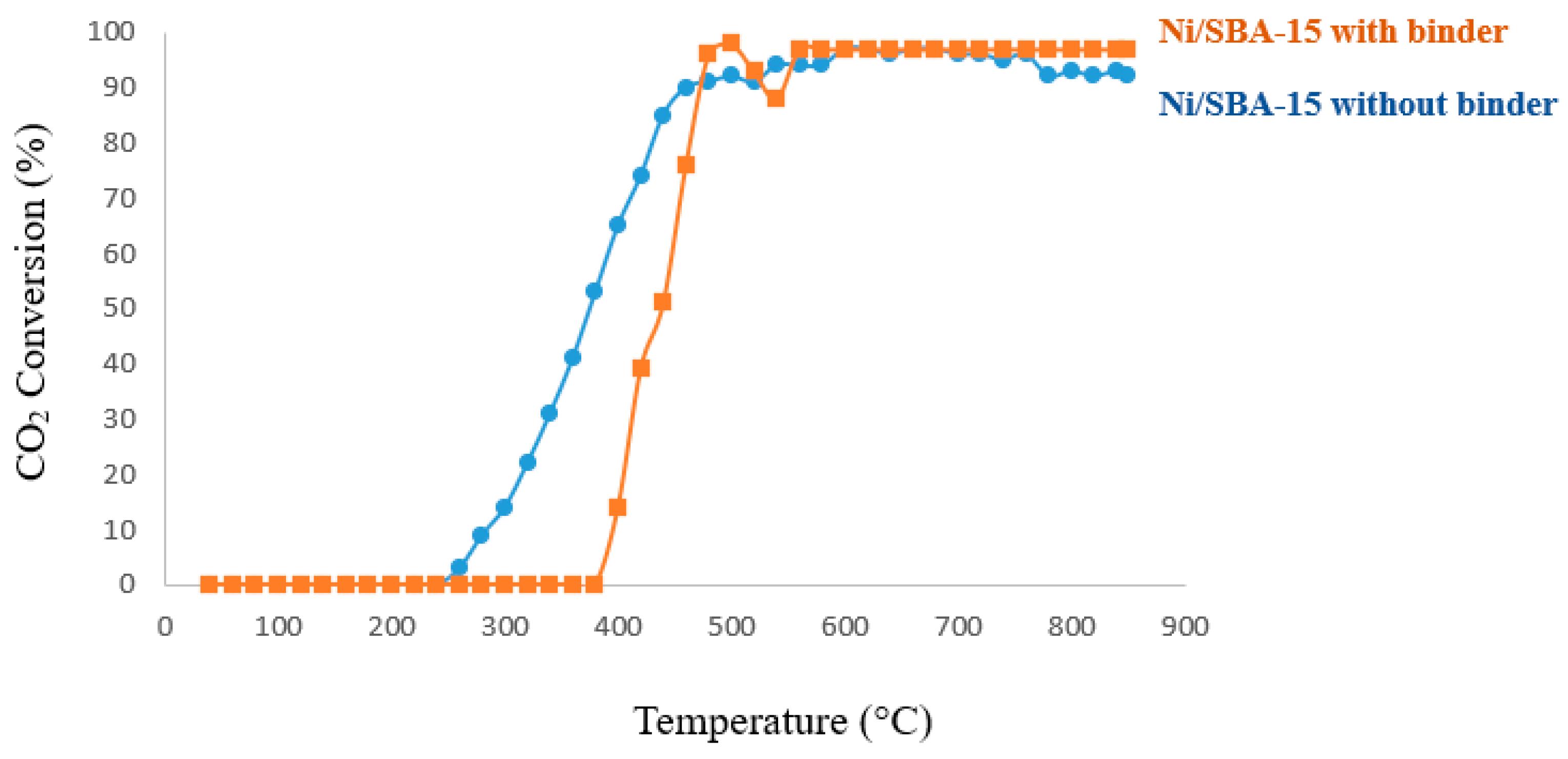

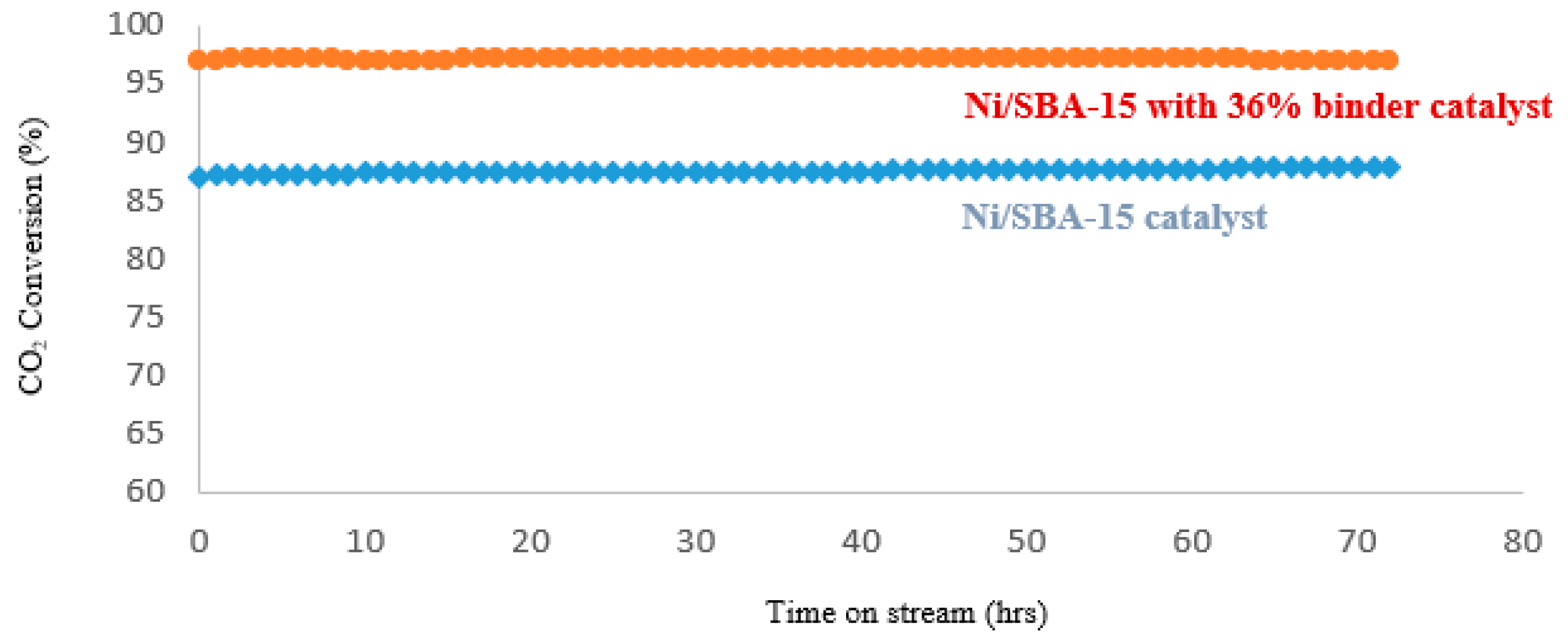

4.1. Catalytic Test Evaluation

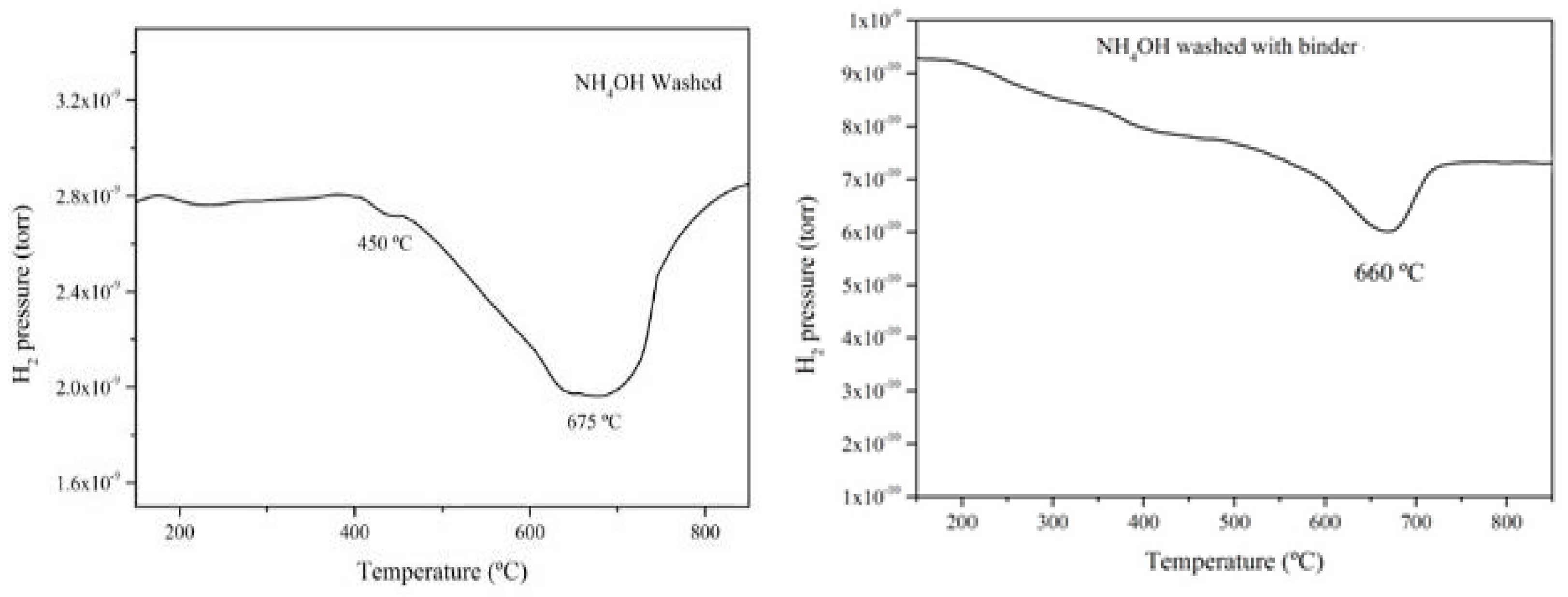

4.2. Temperature Programmed Reaction (TPRx)

4.3. Catalyst Life-Time-Test-On Stream

4.4. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

5. Conclusions

References

- C.o.E. Communities, Council Directive 91/271/EEC of 21 March 1991 concerning urban waste-water treatment (amended by the 98/15/EC of 27 February 1998).

- G. Williams, N. Aitkenhead, Lessons from Loscoe: the uncontrolled migration of landfill gas. Quarterly Journal of Engineering Geology and Hydrogeology 1991, 24, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Boeckx, O.v. Cleemput, I. Villaralvo, Methane emission from a landfill and the methane oxidising capacity of its covering soil. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 1996, 28, 1397–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. W. Mosher, P.M. Czepiel, R.C. Harriss, J.H. Shorter, C.E. Kolb, J.B. McManus, E. Allwine, B.K. Lamb, Methane Emissions at Nine Landfill Sites in the Northeastern United States. Environmental Science & Technology 1999, 33, 2088–2094. [Google Scholar]

- M. d.A.F. Al-Dabbas, Reduction of methane emissions and utilization of municipal waste for energy in Amman. Renewable Energy 1998, 14, 427–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Zamorano, J. Ignacio Pérez Pérez, I. Aguilar Pavés, Á. Ramos Ridao, Study of the energy potential of the biogas produced by an urban waste landfill in Southern Spain. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2007, 11, 909–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Lundin, M. Olofsson, G.J. Pettersson, H. Zetterlund, Environmental and economic assessment of sewage sludge handling options, Resources. Conservation and Recycling 2004, 41, 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S.E. Harakeh, N. S.E. Harakeh, N. Mahmood, Y. Zhang, Sewage Sludge Process Improvement Investigation for London, Ontario in: Green Fuels and Chemicals, University of Western Ontario. Department of Chemical and Biochemical Engineering, 2011.

- G. Maschio, C. Koufopanos, A. Lucchesi, Pyrolysis, a promising route for biomass utilization. Bioresource Technology 1992, 42, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. V. Bridgwater, The technical and economic feasibility of biomass gasification for power generation. Fuel 1995, 74, 631–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Higman, M. C. Higman, M. Van der Burgt, Gasification, Gulf professional publishing, 2011.

- P. McKendry, Energy production from biomass (part 3): gasification technologies. Bioresource Technology 2002, 83, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Z. -b. Hu, W.R.G. Saman, R.R. Navarro, D.-y. Wu, D.-l. Zhang, M. Matsumura, H.-n. Kong, Removal of PCDD/Fs and PCBs from sediment by oxygen free pyrolysis. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2006, 18, 989–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Manara, A. Zabaniotou, Towards sewage sludge based biofuels via thermochemical conversion—A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 2566–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonts, M. Azuara, G. Gea, M.B. Murillo, Study of the pyrolysis liquids obtained from different sewage sludge. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2009, 85, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, Y. Fernández, B. Fidalgo, J.J. Pis, J.A. Menéndez, Bio-syngas production with low concentrations of CO2 and CH4 from microwave-induced pyrolysis of wet and dried sewage sludge. Chemosphere 2008, 70, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- T. Karayildirim, J. Yanik, M. Yuksel, H. Bockhorn, Characterisation of products from pyrolysis of waste sludges. Fuel 2006, 85, 1498–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Font, A. Fullana, J.A. Conesa, F. Llavador, Analysis of the pyrolysis and combustion of different sewage sludges by TG. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2001, 58–59, 927–941. [Google Scholar]

- M. E. Sánchez, O. Martínez, X. Gómez, A. Morán, Pyrolysis of mixtures of sewage sludge and manure: A comparison of the results obtained in the laboratory (semi-pilot) and in a pilot plant. Waste Management 2007, 27, 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Shafizadeh, Introduction to pyrolysis of biomass. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 1982, 3, 283–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Inguanzo, A. Domı́nguez, J.A. Menéndez, C.G. Blanco, J.J. Pis, On the pyrolysis of sewage sludge: the influence of pyrolysis conditions on solid, liquid and gas fractions. Journal of Analytical and Applied Pyrolysis 2002, 63, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bridgwater, Renewable fuels and chemicals by thermal processing of biomass. Chemical Engineering Journal 2003, 91, 87–102. [CrossRef]

- J. Ábrego, J. Arauzo, J.L. Sánchez, A. Gonzalo, T. Cordero, J. Rodríguez-Mirasol, Structural changes of sewage sludge char during fixed-bed pyrolysis. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 2009, 48, 3211–3221. [Google Scholar]

- H. J. Park, H.S. Heo, Y.-K. Park, J.-H. Yim, J.-K. Jeon, J. Park, C. Ryu, S.-S. Kim, Clean bio-oil production from fast pyrolysis of sewage sludge: Effects of reaction conditions and metal oxide catalysts. Bioresource Technology 2010, 101, S83–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Piskorz, D.S. Scott, I.B. Westerberg, Flash pyrolysis of sewage sludge. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Process Design and Development 1986, 25, 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- F. d.M. Mercader, M.J. Groeneveld, S.R.A. Kersten, R.H. Venderbosch, J.A. Hogendoorn, Pyrolysis oil upgrading by high pressure thermal treatment. Fuel 2010, 89, 2829–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. K. Sharma, N.N. Bakhshi, Catalytic upgrading of pyrolysis oil. Energy & Fuels 1993, 7, 306–314. [Google Scholar]

- V. A. Doshi, H.B. Vuthaluru, T. Bastow, Investigations into the control of odour and viscosity of biomass oil derived from pyrolysis of sewage sludge. Fuel Processing Technology 2005, 86, 885–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A.V. Bridgwater, G. A.V. Bridgwater, G. Grassi, Biomass pyrolysis liquids upgrading and utilization, Springer Science & Business Media, 2012.

- S. Xiu, A. Shahbazi, Bio-oil production and upgrading research: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2012, 16, 4406–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Hasler, T. Nussbaumer, Gas cleaning for IC engine applications from fixed bed biomass gasification. Biomass and Bioenergy 1999, 16, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Stevens, R.C. C. Stevens, R.C. Brown, Thermochemical processing of biomass: conversion into fuels, chemicals and power, John Wiley & Sons, 2011.

- C. Xu, J. Donald, E. Byambajav, Y. Ohtsuka, Recent advances in catalysts for hot-gas removal of tar and NH3 from biomass gasification. Fuel 2010, 89, 1784–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. J.M.-W. Roddy, Biomass Gasification and Pyrolysis. Comprehensive Renewable Energy 2012, 5, 133–153. [Google Scholar]

- Y. Cao, Y. Wang, J.T. Riley, W.P. Pan, A novel biomass air gasification process for producing tar-free higher heating value fuel gas. Fuel Processing Technology 2006, 87, 343–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- I. -S. Antonopoulos, A. Karagiannidis, L. Elefsiniotis, G. Perkoulidis, A. Gkouletsos, Development of an innovative 3-stage steady-bed gasifier for municipal solid waste and biomass. Fuel Processing Technology 2011, 92, 2389–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, M. Asadullah, L. Dong, H.-L. Tay, C.-Z. Li, An advanced biomass gasification technology with integrated catalytic hot gas cleaning. Part II: Tar reforming using char as a catalyst or as a catalyst support. Fuel 2013, 112, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- B. Dou, J. Gao, X. Sha, S.W. Baek, Catalytic cracking of tar component from high-temperature fuel gas. Applied Thermal Engineering 2003, 23, 2229–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Delgado, M.P. Aznar, J. Corella, Calcined Dolomite, Magnesite, and Calcite for Cleaning Hot Gas from a Fluidized Bed Biomass Gasifier with Steam: Life and Usefulness. Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research 1996, 35, 3637–3643. [Google Scholar]

- S. Anis, Z. Zainal, Tar reduction in biomass producer gas via mechanical, catalytic and thermal methods: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2011, 15, 2355–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. Wang, J. Chang, P. Lv, J. Zhu, Novel catalyst for cracking of biomass tar. Energy & fuels 2005, 19, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- L. Devi, K.J. Ptasinski, F.J.J.G. Janssen, A review of the primary measures for tar elimination in biomass gasification processes. Biomass and Bioenergy 2003, 24, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Tang. J-P. Cao, Z-M. He, W. Jiang, Z-H. Wang, Recent progress of catalysts for reforming of biomass tar/tar models at low temperature - A short review. ChemCatChem 2023, 15, e202300581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Mitchell, N-L. Michels, J. Pérez-Ramírez, From powder to technical body: the undervalued science of catalysy scale up. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 6094–6112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iro, E.; Ariga-Miwa, H.; Sasaki, T.; Asakura, K.; Olea, M. Elimination of Indoor Volatile Organic Compounds on Au/SBA-15 Catalysts: Insights into the Nature, Size, and Dispersion of the Active Sites and Reaction Mechanism. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. Liu, X.-Y. Quek, H.H.A. Wah, G. Zeng, Y. Li, Y. Yang, Carbon dioxide reforming of methane over nickel-grafted SBA-15 and MCM-41 catalysts. Catalysis Today 2009, 148, 243–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Ni/SBA-15 catalyst (g) | Methyl cellulose (g) | Colloidal silica+H2O suspension (g) | Amount of Colloidal silica in Ni/SBA-15 catalyst (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | - | - | - |

| 2 | 6 | 5 | 10 | 46 |

| 3 | 7 | 5 | 8 | 36 |

| 4 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 27 |

| 5 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 18 |

| 6 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 10 |

| Catalyst | BET surface area (m2/g) | Pore size (nm) |

Pore volume (cm2/g) |

Ni loading (wt. %) | Ni size (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ni/SBA-15 | 539 | 5.3 | 0.65 | 5.7 | 1- 2 |

| Pyrolysis at 800 °C | Sewage sludge | Plant operating parameters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test runs | Moisture content (%) | Density | Residence Time | Feed flow rate (kg/h) | Duration (mins) |

| Test 1 Without catalyst |

7.8 | 0.7 | 20 | 3.7 | 85 |

| Test 2 With Ni/SBA-15 catalyst pellets |

7.8 | 0.7 | 20 | 3.3 | 75 |

| Liquid density (g/cm3) |

pH of liquid | Water content (%) |

Tar content (%) |

Nitrogen content (µg/ml) / wt. ppm |

Sulphur content (µg/ml) / wt. ppm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0347 | 9 | 55 | 45 | 4803 / 4642 |

704 / 680 |

| Tar Compounds | Amount (%) |

|---|---|

| Light aromatics excluding benzene | 22.2 |

| Pyridine | 20.2 |

| Dimethylpyrazine | 9.2 |

| Acids | 9.1 |

| Aliphatic | 7.4 |

| Phenol | 3.6 |

| 4-Pyridiamine | 3 |

| Others | 25.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).