1. Introduction

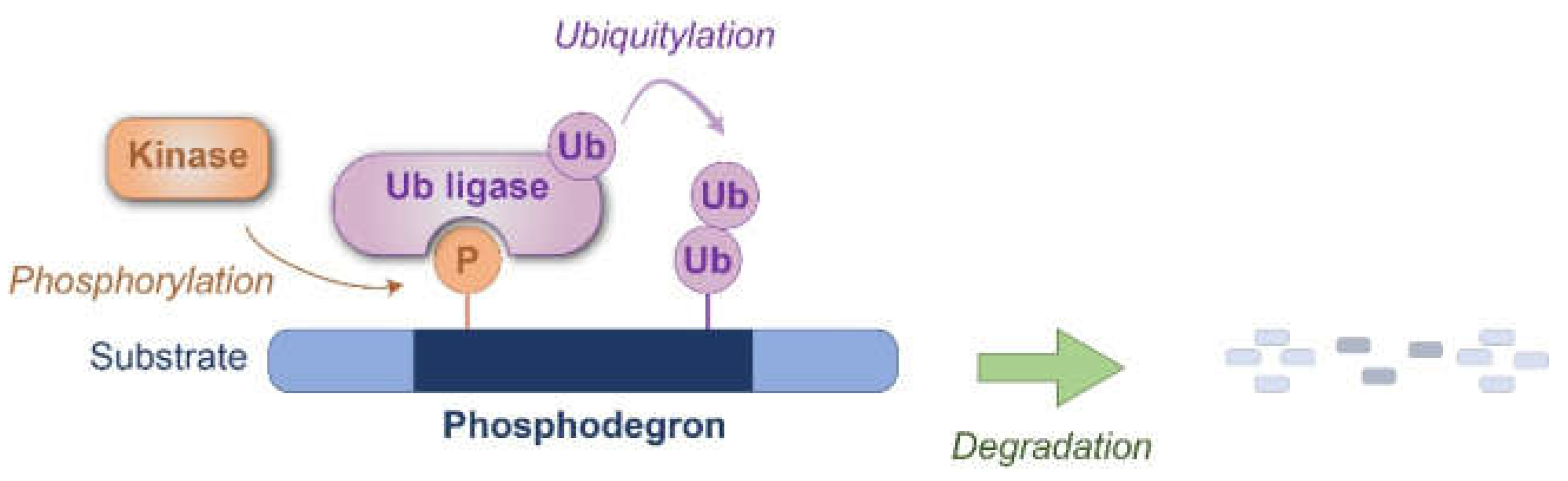

Phosphodegrons are phosphorylation-dependent recognition motifs found within specific proteins, playing a central role in the regulation of protein stability and function. The addition of phosphate groups to serine, threonine, or tyrosine residues within these motifs creates a structural signal that is specifically recognized by ubiquitin ligases or ubiquitin ligase subunits, such as β-TrCP or other F-box proteins [

1,

2,

3,

4], enabling the targeted ubiquitylation (also termed ubiquitination) and subsequent proteasomal degradation of proteins (

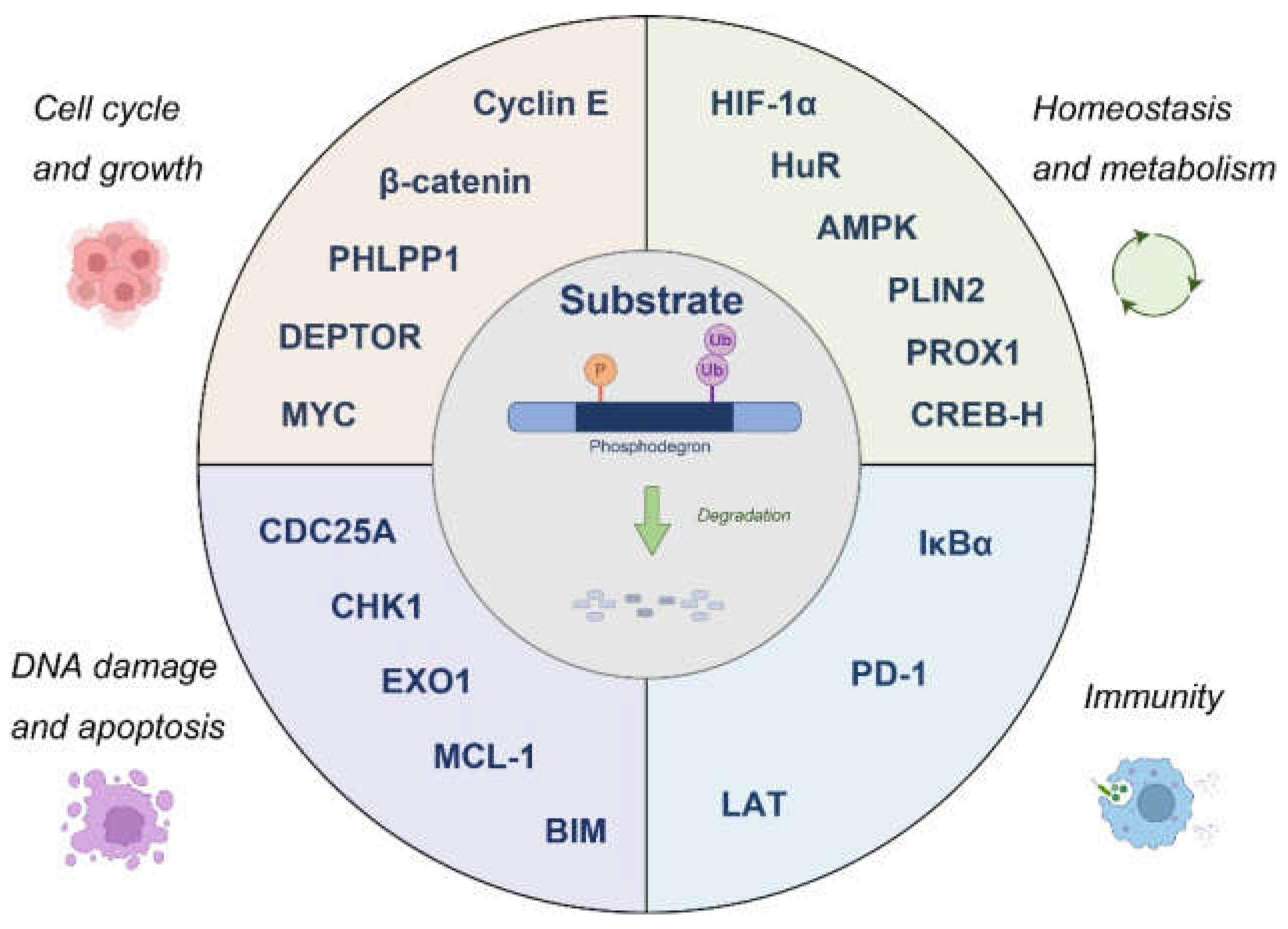

Figure 1). The functional importance of phosphodegrons lies in their ability to precisely control protein turnover, ensuring the timely degradation of key regulatory proteins involved in diverse cellular processes. For example, phosphodegrons regulate the degradation of cyclins during the cell cycle, transcription factors under hypoxic conditions, and DNA repair proteins in response to damage signals. This dynamic process contributes to cellular homeostasis by coordinating the activity of various signaling pathways. Importantly, the dysregulation of phosphodegron-mediated protein degradation has been implicated in a wide range of diseases, including cancer, inflammatory conditions, and neurodegenerative disorders, [

5]. As such, understanding the structural and functional properties of phosphodegrons is essential for deciphering their role in cellular regulation and identifying potential therapeutic targets.

The concept of phosphodegrons emerged as a critical advancement in understanding how cells regulate protein stability through post-translational modifications. The discovery of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, for which the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded in 2004, laid the groundwork for the identification of phosphodegrons [

6,

7]. Researchers identified that the UPS relies on precise recognition motifs within proteins to mediate their targeted degradation. However, the molecular details of how phosphorylation influences protein turnover remained unclear for several decades.

The first direct evidence of phosphodegrons came from studies on the degradation of cyclin E (in mammalian cells) and Sic1 (in budding yeast) in cell cycle regulation during the 1990s [

8,

9,

10]. In particular, the identification of the F-box protein as a key component of the SCF ubiquitin ligase complex revealed how phosphorylated motifs within target proteins serve as recognition sites [

10,

11]. These phosphorylation-dependent degradation motifs were later termed "phosphodegrons" [

12].

Subsequent research demonstrated that phosphodegrons are not limited to cell cycle regulators but are broadly involved in a variety of signaling pathways, including those governing DNA damage response, apoptosis, and metabolic regulation. Advances in proteomics and structural biology in the 2000s further refined our understanding of phosphodegrons, uncovering their molecular diversity and functional specificity. Today, phosphodegrons are recognized as critical components of cellular signaling networks, with their discovery and characterization continuing to shape our understanding of protein dynamics in health and disease. This historical trajectory highlights the importance of interdisciplinary research in unraveling the complexity of phosphodegron-mediated regulation.

This review aims to provide an overview of current knowledge on phosphodegrons, highlighting their fundamental biological significance and potential as therapeutic targets, while inspiring further research in this critical area of molecular biology with the discussion on recent advancements in molecular and in silico tools.

2. Phosphodegrons in Cell Cycle and Growth Control

Phosphodegrons play a pivotal role in the precise regulation of the cell cycle and cellular growth by controlling the timely degradation of key regulatory proteins. The cell cycle is a tightly regulated process driven by the coordinated action of cyclins, cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs), and their inhibitors [

13]. Phosphodegrons ensure the orderly progression through the different phases of the cell cycle by facilitating the targeted proteolysis of proteins at specific checkpoints.

For example, during the G1-to-S phase transition, the phosphorylation of cyclin E creates a phosphodegron that is recognized by the F-box protein FBXW7 (previously called FBW7), a component of the SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. This leads to the ubiquitylation and degradation of cyclin E, preventing its overaccumulation and ensuring proper S-phase entry [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Another well-characterized example of cell cycle regulation by phosphodegron involves the phosphorylation dependent degradation of β-catenin, a central player in the WNT signaling pathway. Under conditions where WNT signaling is inactive, β-catenin is phosphorylated which creates a binding site for β-TrCP. This interaction facilitates the ubiquitylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation of β-catenin, thereby maintaining low cytoplasmic β-catenin levels and preventing its nuclear translocation [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. This results in the reduced transcription of WNT target genes, many of which promote cell cycle progression and proliferation.

Phosphodegrons also regulate growth pathways by targeting key signaling proteins. For instance, in the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, which controls cell growth and metabolism, the phosphorylation of PHLPP1, a negative regulator of AKT, causes the degradation by β-TrCP [

25]. A pivotal kinase implicated in PHLPP1 phosphorylation is GSK3, whose activity is suppressed by AKT [

26]. Consequently, during AKT inactivity, the activation of GSK3 promotes PHLPP1 phosphorylation and subsequent degradation, thereby triggering AKT activation and sustaining AKT kinase activity. Similarly, the phosphorylation of DEPTOR, a negative regulator of mTOR kinase, by mTOR kinase and several other kinases generates a phosphodegron recognized by β-TrCP, promoting DEPTOR degradation and mTOR kinase activation [

27,

28,

29]. Thus, these feedback mechanisms ensure balanced growth in response to nutrient and energy availability.

The MYC protein, a master regulator of cell proliferation and growth, is tightly controlled by post-translational mechanisms, including phosphodegrons recognized by FBXW7 [

30,

31]. This regulation ensures that MYC levels are appropriately modulated to prevent aberrant cell cycle progression and uncontrolled growth, processes that are often disrupted in cancer.

3. Phosphodegrons in DNA Damage Response and Apoptosis

Phosphodegrons also play a critical role in maintaining cellular homeostasis by regulating the degradation of proteins involved in the DNA damage response (DDR) and apoptosis. These processes are essential for safeguarding genomic integrity and preventing the propagation of damaged or aberrant cells.

In the DDR, phosphodegrons are crucial for the timely removal of proteins that control cell cycle checkpoints and DNA repair. One well-studied example is the phosphorylation-dependent degradation of CDC25A, a phosphatase required for CDK activation. Upon DNA damage, CDC25A is phosphorylated by CHK1, creating a phosphodegron that is recognized by β-TrCP, resulting in its degradation [

32,

33]. This mechanism enforces cell cycle arrest, giving the cell time to repair damaged DNA before cell cycle progression.

CHK1, a serine/threonine kinase, is activated in response to replication stress and DNA damage, orchestrating the repair process by phosphorylating multiple substrates, including the CDC25A phosphodegron, as previously described. Active CHK1 is itself phosphorylated, which serves as a signal for recognition by the F-box protein FBXW6, a substrate adaptor of the SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. This interaction facilitates the ubiquitylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation of CHK1, thereby concluding checkpoint signaling and permitting the resumption of cell cycle progression [

34,

35].

EXO1, a 5′ to 3′ exonuclease, plays a pivotal role in DNA end resection during DNA repair processes. Similar to CHK1, EXO1 is activated by phosphorylation in response to DNA damage, which marks it for recognition by Cyclin F (also known as FBXO1), an F-box protein functioning as a substrate adaptor for the SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. This interaction drives the ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation of EXO1 [

36,

37]. Such regulation is particularly critical after the completion of DNA repair, as unchecked EXO1 activity could result in aberrant DNA end resection and chromosomal instability.

In the context of apoptosis, phosphodegrons regulate the stability of pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic proteins, ensuring a balanced response to cellular stress. For example, the phosphorylation of the anti-apoptotic protein MCL-1 creates a phosphodegron that is recognized by several ubiquitin ligases, leading to its ubiquitylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation [

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. This degradation allows for the activation of pro-apoptotic factors such as BIM, facilitating the initiation of apoptosis in response to stress signals.

The degradation of BIM is another key example of how phosphodegrons regulate apoptosis. BIM, a BH3-only member of the BCL-2 family, serves as a critical mediator of apoptosis by antagonizing anti-apoptotic BCL-2 family proteins and directly activating BAX and BAK, leading to mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and subsequent cytochrome c release. Under conditions of cellular stress, the activation of ERK kinases phosphorylates the phosphodegron domain of BIM, facilitating its degradation [

44,

45,

46,

47]. The role of ubiquitin in this process remains controversial, as phosphorylated BIM may be targeted to the proteasome via a ubiquitin-independent mechanism [

47]. This regulatory pathway serves to avert inappropriate apoptosis in response to diverse cellular stresses, ranging from the withdrawal of survival factors to endoplasmic reticulum overload.

4. Dysregulation and Utilization of Phosphodegrons in Cancer

As discussed in the preceding two sections, phosphodegrons ensure the precise turnover of key regulatory proteins involved in cell cycle control, growth, apoptosis, and DNA damage signaling pathways. Consequently, aberrations in these pathways can result in uncontrolled proliferation, evasion of apoptosis, and genomic instability, which are hallmarks of cancer [

48].

One common mechanism of dysregulation in cancers is the mutation or deletion of phosphodegron motifs within oncogenic proteins, rendering them resistant to ubiquitin-mediated degradation. For example, mutations in the phosphodegron of MYC prevent its recognition by the F-box protein FBXW7, leading to its accumulation and subsequent hyperactivation of the cell cycle [

49,

50]. Similarly, oncogenic mutations in β-catenin can abolish its phosphodegron, promoting its stabilization and constitutive activation of WNT signaling [

51], a pathway frequently upregulated in cancers such as colorectal carcinoma.

Alterations in ubiquitin ligases that recognize phosphodegrons also contribute to tumorigenesis. Loss-of-function mutations in FBXW7, for instance, impair the degradation of several oncogenic substrates, including MYC and cyclin E, leading to increased cellular proliferation and survival [

52]. Conversely, overexpression of certain ubiquitin ligases, such as β-TrCP, can enhance the degradation of tumor suppressors [

53], further tipping the balance toward malignancy.

Furthermore, phosphodegron dysregulation is implicated in resistance to therapy. For example, the loss of phosphodegron-mediated degradation of anti-apoptotic proteins like MCL-1 can enable cancer cells to evade apoptosis, contributing to resistance to chemotherapy and targeted therapies [

54].

Another significant role of phosphodegrons in cancer lies in their functional utilization. For instance, under glucose-starvation conditions commonly encountered by tumors, AMPK phosphorylates CHK1, targeting it for degradation via β-TrCP. This degradation impairs DNA repair mechanisms, thereby promoting tumorigenesis and enhancing cellular resistance to genomic stress. [

55,

56].

As described above, understanding the dysregulation and functional exploitation of phosphodegrons in cancer offers profound insights into tumor biology and presents promising opportunities for the development of targeted therapeutic strategies.

5. Phosphodegrons in Cellular Homeostasis, Metabolism and Stress Responses

Phosphodegrons play a crucial role in maintaining cellular homeostasis by modulating the turnover of essential proteins involved in stress response pathways and adaptive cellular processes beyond DNA damage repair. By facilitating the precise and timely degradation of targeted proteins, phosphodegrons enable cells to dynamically adapt to various environmental and intracellular stressors, including oxygen and nutrient deprivation, thermal stress, and metabolic perturbations.

One example of this role is the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF-1α). Under normoxic conditions, HIF-1α is hydroxylated, creating a hydroxydegron that is recognized by the Von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) ubiquitin ligase, leading to its degradation. This degradation prevents unnecessary activation of hypoxia-responsive genes. In hypoxic conditions, however, the lack of hydroxylation stabilizes HIF-1α, enabling it to activate adaptive responses such as angiogenesis and metabolic reprogramming [

57,

58,

59]. The FBXW7-containing complex provides an additional layer of regulation by degrading phosphorylated HIF-1α [

60,

61]. This pathway remains active under hypoxic conditions, providing a mechanism for HIF-1α regulation when the VHL-mediated pathway is inactive.

Another example is provided by heat shock response. Heat stress phosphorylates HuR, mRNA regulator, to induce TRIM21-mediated ubiquitylation and degradation, meriting survival and recovery from heat shock [

62].

Additionally, phosphodegrons modulate metabolic homeostasis by regulating proteins in key signaling pathways such as AKT/mTOR as described above and AMPK. For example, under high-glucose condition, AMPK is phosphorylated by AKT, creating a recognition site of E3 ligase TRIM72 (also known as MG53), resulting in degradation [

63]. AMPK itself serves as a kinase activating phosphodegron; one such example is phosphorylation of a lipid droplet protein PLIN2. When lipolysis is induced, PLIN2 is phosphorylated and degraded by chaperon-mediated autophagy [

64]. Another protein subjected to AMPK-dependent degradation is the transcriptional repressor PROX1, a repressor of intracellular BCAA pools [

65]. By this mechanism, intracellular BCAA pools are maintained under glucose starvation condition. As such, the phosphorylation-dependent degradation of AMPK itself or its substrates ensures a rapid switch between anabolic and catabolic states, enabling cells to adapt to changes in energy availability.

Lipid metabolism also involves phosphodegron. In this process, the amount of CREB-H, a liver-enriched transcription factor that plays a crucial role in regulating triglyceride homeostasis, is controlled through phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation mediated by the SCF-βTrCP ubiquitin ligase [

66].

Taken together, these data suggest that dysregulation of these phosphodegron-mediated processes can lead to chronic cellular stress and metabolic imbalance, both of which are hallmarks of various diseases. By highlighting their role in cellular homeostasis and stress responses, phosphodegrons emerge as promising therapeutic targets for restoring cellular balance in pathological conditions.

6. Phosphodegrons in Immunity and Immunological Diseases

Phosphodegrons are also integral to the regulation of immune responses by modulating the stability and activity of key immune signaling proteins. Through phosphorylation-dependent degradation, phosphodegrons ensure the timely turnover of regulatory proteins, maintaining immune homeostasis. Dysregulation of phosphodegron-mediated pathways can lead to immune dysfunction, contributing to chronic inflammation, autoimmunity, or immunosuppression.

One of the most well-studied examples of phosphodegron regulation in immunity involves the NF-κB signaling pathway, a central regulator of inflammatory and immune responses. The inhibitor of NF-κB, IκBα, contains a phosphodegron that is phosphorylated by the IκB kinase (IKK) complex in response to inflammatory signals. Phosphorylation of IκBα at specific serine residues generates a phosphodegron that is recognized by the SCF

β-TrCP ubiquitin ligase complex, leading to IκBα ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation [

20,

67,

68,

69,

70]. This degradation releases NF-κB, allowing it to translocate to the nucleus and activate the transcription of immune-response genes. Dysregulation of this process, such as deletion mutations in the IκBα phosphodegron, can lead to immunodeficiency [

71,

72,

73].

Immune checkpoint protein PD-1 is also influenced by phosphodegron-mediated regulation. Phosphorylation of PD-1 generates phosphodegrons recognized by FBXW7, triggering its degradation, and modulating their availability on the cell surface and fine-tuning immune responses [

74]. Dysregulation of these processes has implications for cancer immunotherapy, where immune checkpoint blockade is a key therapeutic strategy.

Immune cell activity is strictly regulated by stimulatory and inhibitor receptors. When inhibitory receptors on NK cells are engaged, LAT phosphorylation induces its ubiquitylation by ubiquitin ligases c-CBL and CBL-b and this ubiquitylation leads to LAT degradation by lysosome, resulting in suppression of NK cell cytotoxicity, suggesting that cytotoxic activity of immune cells is also under the control of phosphodegron [

75].

Phosphodegrons thus serve as molecular switches that balance immune activation and suppression, ensuring appropriate responses to infections and maintaining self-tolerance. Their critical role in regulating immunity makes them attractive therapeutic targets. Small molecules or peptides that modulate phosphodegron activity could enhance immune responses in immunodeficient states or suppress them in autoimmune diseases. Understanding the broader network of phosphodegrons in immune signaling will provide new insights into immune regulation and offer innovative strategies for therapeutic intervention.The substrates elaborated upon in the preceding sections are depicted in

Figure 2.

7. Phosphodegrons in Neurodegenerative Diseases

Phosphodegrons are increasingly recognized as critical regulators of proteostasis, and their dysregulation has profound implications in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), Huntington’s disease (HD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) are characterized by the accumulation of misfolded or aggregation-prone proteins, a process often resulting from defects in protein turnover. Phosphodegron-mediated pathways, which enable the targeted degradation of specific proteins through the ubiquitin-proteasome system, are vital for preventing such pathological accumulations. When these pathways are disrupted, cellular proteostasis collapses, contributing to neurodegeneration.

In AD, for instance, the microtubule-associated protein tau undergoes phosphorylation at specific residues, forming phosphodegrons that mark it for proteasomal degradation [

76,

77,

78]. Dysregulation in this process leads to the accumulation of hyperphosphorylated tau, which aggregates into neurofibrillary tangles, a hallmark of AD pathology.

In PD, PARIS, an accumulation of which causes neurodegeneration, is tightly controlled by phosphodegron-mediated mechanisms. Phosphorylation of PARIS by PINK1 creates a phosphodegron that facilitates its recognition by specific ubiquitin ligase Parkin [

79]. Mutations in

Parkin and

PINK1 are linked to familial forms of PD [

80]. These mutations impair the degradation of PARIS, promoting neuronal dysfunction and death.

HD is also speculated to involves phosphodegron dysregulation. The mutant huntingtin protein (mHTT) contains expanded polyglutamine (polyQ) tracts, which confers the ability to form aggregate and interfere with cellular functionality. Phosphorylation of either wild-type or mutant HTT targets it for degradation by E3 ligase CHIP [

81] and disruption of this process would lead to the accumulation of HTT, contributing to neuronal loss and motor dysfunction.

In ALS, most patients contain TDP-43 aggregates which are phosphorylated and ubiquitylated. Thus, the dysregulation of phosphodegron is suspected, by not clarified. Instead,

SOD1 mutation, which was the first mutation identified in ALS, involves phosphodegron. In mice with

SOD1 mutation, reactive oxygen species-mediated phosphorylation of occludin induces ubiquitylation and lysosomal degradation, causing blood-spinal cord barrier disruption, a characteristic of ALS [

82].

Mutations in

HSPB1 (also known as

HSP27) have been implicated in Charcot-Marie-Tooth (CMT) disease, a disorder characterized by progressive nerve degeneration [

83]. HSPB1 has been shown to facilitate the phosphodegron-mediated degradation of BIM. However, CMT-associated HSPB1 variants are linked to elevated BIM levels and exhibit an inability to confer protection against ER stress-induced apoptosis, highlighting a potential mechanism underlying the disease pathology [

47].

Targeting phosphodegron-mediated pathways offers promising therapeutic opportunities in neurodegenerative diseases. Strategies aimed at enhancing phosphodegron recognition, or stabilizing phosphodegron interactions could promote the clearance of toxic proteins and mitigate neurodegeneration. Small molecules that mimic phosphodegron motifs or inhibitors that block the aggregation of degradation-resistant proteins represent potential approaches for disease-modifying treatments. Furthermore, advancing our understanding of how phosphodegrons contribute to proteostasis and neuronal survival will provide novel insights into the development of targeted therapies for these devastating disorders.

The substrates, kinases and ubiquitin ligases taken up in this article are summarized in

Table 1.

8. Future Directions

Recent advancements in molecular and computational tools have propelled phosphodegron research, enabling more precise identification and functional characterization of these critical regulatory motifs. These innovations have deepened our understanding of how phosphodegrons govern protein turnover and cellular processes, while also paving the way for new therapeutic applications.

Phosphoproteomics and ubiquitylomics (also called ubiquitinomics) have emerged as a cornerstone for phosphodegron research, leveraging high-resolution mass spectrometry (MS) to map phosphorylation and ubiquitylation sites across the proteome [

84,

85,

86]. These approaches have allowed the unbiased identification of novel phosphodegrons. Recent studies have also used quantitative MS techniques, such as label-free quantitation or stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC), to monitor dynamic changes in phosphodegron activity under various physiological and pathological conditions [

87].

Computational tools such as PhosphoSitePlus, ELM, deepDegron and DegronID have advanced phosphodegron discovery by predicting potential functional degron motifs [

88,

89,

90,

91]. Further elaboration of machine learning-based algorithms trained on experimentally validated phosphodegrons would provide rapid in silico identification of candidate motifs for experimental validation and accelerate the discovery of conserved phosphodegrons and their roles in diverse biological contexts.

Structural biology techniques, including X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM, have elucidated the interactions between phosphodegrons and their binding ubiquitin ligases [

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97]. These studies reveal how specific phosphorylation events enable substrate recognition, providing critical insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying phosphodegron function. This structural information would be beneficial to guiding the design of inhibitors and mimetics that modulate phosphodegron activity [

98].

CRISPR technology has revolutionized biomedical researches by enabling genome editing with ease [

99,

100,

101]. Although most researches on phosphodegron do not utilize this technique, this approach, especially site-specific mutagenesis of phosphodegron, would be instrumental in studying the functional relevance of specific phosphodegrons in protein stability and signaling pathways in the endogenous settings [

102,

103]. Additionally, CRISPR-based genomic screens would uncover new components involved in phosphodegron-related pathways.

Chemical biology approaches, including phosphorylation-mimetic peptides [

104] and binding enhancers [

105], could provide versatile tools for studying phosphodegrons. These probes allow researchers to dissect phosphodegron interactions with E3 ligases and assess their functional relevance in cellular and disease models.

The ongoing integration of proteomics, computational modeling, and structural biology continues to advance the field of phosphodegron research. Emerging technologies, such as single-cell proteomics and artificial intelligence-driven motif discovery, hold great promise for uncovering previously unrecognized phosphodegrons and their biological roles. These advancements will further elucidate the fundamental mechanisms of phosphodegron-mediated regulation and highlight their potential as therapeutic targets in diverse diseases.

9. Concluding Remarks

Phosphodegrons are central to the regulation of protein turnover, playing critical roles in key cellular processes such as cell cycle control, DNA damage repair, apoptosis, and stress responses. By acting as phosphorylation-dependent recognition motifs for ubiquitin ligases, phosphodegrons ensure the precise timing and fidelity of proteasomal degradation, thereby maintaining cellular homeostasis. Dysregulation of phosphodegron-mediated pathways has been implicated in a wide range of diseases, including cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, metabolic syndromes, and immune dysfunction, underscoring their importance in both health and disease.

Recent advancements in mass spectrometry, computational modeling, and structural biology provide the basis on revolutionizing the identification and characterization of phosphodegrons, gaining unprecedented insights into their molecular mechanisms and regulatory networks. These findings only expand our understanding of how phosphodegrons govern cellular signaling but also highlight their potential as therapeutic targets.

Many phosphodegrons and their interacting partners remain unidentified, and the complexity of their regulatory networks is not fully understood. Future investigations should focus on integrating multi-omics approaches, applying advanced computational tools, and exploring the functional roles of phosphodegrons in diverse biological contexts. Additionally, translating phosphodegron research into clinical applications will require innovative approaches to modulate their activity with precision and specificity.

In conclusion, phosphodegrons represent a critical intersection of cellular regulation, disease pathology, and therapeutic potential. Continued research into their biology and applications promises to uncover novel mechanisms, enhance our understanding of proteostasis, and drive the development of targeted treatments for a wide range of diseases. By addressing the outstanding questions and leveraging emerging technologies, phosphodegron research will continue to illuminate new frontiers in molecular and cellular biology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.N.; literature search and analysis T.N. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation, T.N. and M.N.; review and editing, T.N.; funding acquisition, T.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by KAKENHI, grant number 23K06367.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Keiichi I. Nakayama and Keiko Nakayama for guiding to and supporting for our research on CRL1F-box proteins.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Holt, L.J. Regulatory modules: Coupling protein stability to phopshoregulation during cell division. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 2773–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.M. and L. Busino. The Biology of F-box Proteins: The SCF Family of E3 Ubiquitin Ligases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1217, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Skaar, J.R. J.K. Pagan, and M. Pagano. SCF ubiquitin ligase-targeted therapies. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014, 13, 889–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, L.L. , et al. The SCF Complex Is Essential to Maintain Genome and Chromosome Stability. The SCF Complex Is Essential to Maintain Genome and Chromosome Stability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa, T. K. Nakayama, and K.I. Nakayama. Knockout Mouse Models Provide Insight into the Biological Functions of CRL1 Components. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020, 1217, 147–171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Melino, G. Discovery of the ubiquitin proteasome system and its involvement in apoptosis, in Cell Death Differ. 2005: England. 1155-7–1157.

- Wilkinson, K.D. The discovery of ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15280–15282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clurman, B.E. , et al. Turnover of cyclin E by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is regulated by cdk2 binding and cyclin phosphorylation. Genes. Dev. 1996, 10, 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Won, K.A. and S.I. Reed, Activation of cyclin E/CDK2 is coupled to site-specific autophosphorylation and ubiquitin-dependent degradation of cyclin E. Embo j 1996, 15, 4182–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skowyra, D. , et al. F-box proteins are receptors that recruit phosphorylated substrates to the SCF ubiquitin-ligase complex. Cell 1997, 91, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, C. , et al. SKP1 connects cell cycle regulators to the ubiquitin proteolysis machinery through a novel motif, the F-box. Cell 1996, 86, 263–274. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, T. , The age of crosstalk: phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and beyond. Mol. Cell 2007, 28, 730–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, H.K.; Bertoli, C.; de Bruin, R.A.M. Cell cycle control in cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2022, 23, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmaier, H. , et al. Human F-box protein hCdc4 targets cyclin E for proteolysis and is mutated in a breast cancer cell line. Nature 2001, 413, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koepp, D.M. , et al. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin E by the SCFFbw7 ubiquitin ligase. Science 2001, 294, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welcker, M. , et al. Multisite phosphorylation by Cdk2 and GSK3 controls cyclin E degradation. Mol. Cell 2003, 12, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, X. , et al. Recognition of phosphodegron motifs in human cyclin E by the SCF(Fbw7) ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 50110–50119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Drogen, F. , et al. Ubiquitylation of cyclin E requires the sequential function of SCF complexes containing distinct hCdc4 isoforms. Mol. Cell 2006, 23, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grim, J.E. , et al. Isoform- and cell cycle-dependent substrate degradation by the Fbw7 ubiquitin ligase. J. Cell Biol. 2008, 181, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, J.T. , et al. The SCFbeta-TRCP-ubiquitin ligase complex associates specifically with phosphorylated destruction motifs in IkappaBalpha and beta-catenin and stimulates IkappaBalpha ubiquitination in vitro. Genes. Dev. 1999, 13, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- tres, E., D.S. Chiaur and M. Pagano. The human F box protein beta-Trcp associates with the Cul1/Skp1 complex and regulates the stability of beta-catenin. Oncogene 1999, 18, 849–854.

- Hart, M. , et al. The F-box protein beta-TrCP associates with phosphorylated beta-catenin and regulates its activity in the cell. Curr. Biol. 1999, 9, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitagawa, M. , et al. An F-box protein, FWD1, mediates ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis of beta-catenin. Embo j 1999, 18, 2401–2410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Liu, C. , et al. beta-Trcp couples beta-catenin phosphorylation-degradation and regulates Xenopus axis formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 6273–6278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. J. Liu, and T. Gao, beta-TrCP-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of PHLPP1 are negatively regulated by Akt. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 29, 6192–6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majewska, E. and M. Szeliga. AKT/GSK3β Signaling in Glioblastoma. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, D. , et al. mTOR drives its own activation via SCF(βTrCP)-dependent degradation of the mTOR inhibitor DEPTOR. Mol. Cell 2011, 44, 290–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y. X. Xiong, and Y. Sun, DEPTOR, an mTOR inhibitor, is a physiological substrate of SCF(βTrCP) E3 ubiquitin ligase and regulates survival and autophagy. Mol. Cell 2011, 44, 304–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, S. , et al. mTOR generates an auto-amplification loop by triggering the βTrCP- and CK1α-dependent degradation of DEPTOR. Mol. Cell 2011, 44, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yada, M. , et al. Phosphorylation-dependent degradation of c-Myc is mediated by the F-box protein Fbw7. Embo j 2004, 23, 2116–2125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welcker, M. , et al. The Fbw7 tumor suppressor regulates glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylation-dependent c-Myc protein degradation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2004, 101, 9085–9090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busino, L. , et al. Degradation of Cdc25A by beta-TrCP during S phase and in response to DNA damage. Nature 2003, 426, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J. , et al. SCFbeta-TRCP links Chk1 signaling to degradation of the Cdc25A protein phosphatase. Genes. Dev. 2003, 17, 3062–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.W. , et al. Genotoxic stress targets human Chk1 for degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Mol. Cell 2005, 19, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.W. , et al. The F box protein Fbx6 regulates Chk1 stability and cellular sensitivity to replication stress. Mol. Cell 2009, 35, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomimatsu, N. , et al. DNA-damage-induced degradation of EXO1 exonuclease limits DNA end resection to ensure accurate DNA repair. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 10779–10790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H. , et al. Cyclin F-EXO1 axis controls cell cycle-dependent execution of double-strand break repair. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eado0636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q. , et al. Degradation of Mcl-1 by beta-TrCP mediates glycogen synthase kinase 3-induced tumor suppression and chemosensitization. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 27, 4006–4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harley, M.E. , et al. Phosphorylation of Mcl-1 by CDK1-cyclin B1 initiates its Cdc20-dependent destruction during mitotic arrest. Embo j 2010, 29, 2407–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inuzuka, H. , et al. SCF(FBW7) regulates cellular apoptosis by targeting MCL1 for ubiquitylation and destruction. Nature 2011, 471, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wertz, I.E. , et al. Sensitivity to antitubulin chemotherapeutics is regulated by MCL1 and FBW7. Nature 2011, 471, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magiera, M.M. , et al. Trim17-mediated ubiquitination and degradation of Mcl-1 initiate apoptosis in neurons. Cell Death Differ. 2013, 20, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, H. , et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligases β-TrCP and FBXW7 cooperatively mediates GSK3-dependent Mcl-1 degradation induced by the Akt inhibitor API-1, resulting in apoptosis. Mol. Cancer 2013, 12, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, R. , et al. Activation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway promotes phosphorylation and proteasome-dependent degradation of the BH3-only protein, Bim. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 18811–18816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luciano, F. , et al. Phosphorylation of Bim-EL by Erk1/2 on serine 69 promotes its degradation via the proteasome pathway and regulates its proapoptotic function. Oncogene 2003, 22, 6785–6793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, A. , et al. Multisite phosphorylation regulates Bim stability and apoptotic activity. Mol. Cell 2008, 30, 415–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D. , et al. HSPB1 facilitates ERK-mediated phosphorylation and degradation of BIM to attenuate endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. , Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahram, F. , et al. c-Myc hot spot mutations in lymphomas result in inefficient ubiquitination and decreased proteasome-mediated turnover. Blood 2000, 95, 2104–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minella, A.C. , et al. Cyclin E phosphorylation regulates cell proliferation in hematopoietic and epithelial lineages in vivo. Genes. Dev. 2008, 22, 1677–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. and S. Jeong, Mutation Hotspots in the β-Catenin Gene: Lessons from the Human Cancer Genome Databases. Mol. Cells 2019, 42, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, J. , et al. Clinical significance of FBXW7 loss of function in human cancers. Mol. Cancer 2022, 21, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.J. Y.W. Yi, and Y.S. Seong, Beta-Transducin Repeats-Containing Proteins as an Anticancer Target. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, J. , et al. FBW7 mutations mediate resistance of colorectal cancer to targeted therapies by blocking Mcl-1 degradation. Oncogene 2017, 36, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, A.J. , et al. Glucose deprivation is associated with Chk1 degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and effective checkpoint response to replication blocks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1813, 1230–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y. , et al. SCFβ-TrCP ubiquitinates CHK1 in an AMPK-dependent manner in response to glucose deprivation. Mol. Oncol. 2019, 13, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, P.H. , et al. The tumour suppressor protein VHL targets hypoxia-inducible factors for oxygen-dependent proteolysis. Nature 1999, 399, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivan, M. , et al. HIFalpha targeted for VHL-mediated destruction by proline hydroxylation: implications for O2 sensing. Science 2001, 292, 464–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaakkola, P. , et al. Targeting of HIF-alpha to the von Hippel-Lindau ubiquitylation complex by O2-regulated prolyl hydroxylation. Science 2001, 292, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassavaugh, J.M. , et al. Negative regulation of HIF-1α by an FBW7-mediated degradation pathway during hypoxia. J. Cell Biochem. 2011, 112, 3882–3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flügel, D. A. Görlach, and T. Kietzmann, GSK-3β regulates cell growth, migration, and angiogenesis via Fbw7 and USP28-dependent degradation of HIF-1α. Blood 2012, 119, 1292–1301. [Google Scholar]

- Nag, S. , et al. An AKT1-and TRIM21-mediated phosphodegron controls proteasomal degradation of HuR enabling cell survival under heat shock. iScience 2023, 26, 106307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P. , et al. Negative regulation of AMPK signaling by high glucose via E3 ubiquitin ligase MG53. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 629–637.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S. and A.M. Cuervo, AMPK-dependent phosphorylation of lipid droplet protein PLIN2 triggers its degradation by CMA. Autophagy 2016, 12, 432–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y. , et al. AMPK induces degradation of the transcriptional repressor PROX1 impairing branched amino acid metabolism and tumourigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa, S. , et al. Phosphorylation and SCF-mediated degradation regulate CREB-H transcription of metabolic targets. Mol. Biol. Cell 2015, 26, 2939–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaron, A. , et al. Identification of the receptor component of the IkappaBalpha-ubiquitin ligase. Nature 1998, 396, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, E. J. Jiang, and Z. J. Chen, Signal-induced ubiquitination of IkappaBalpha by the F-box protein Slimb/beta-TrCP. Genes Dev 1999, 13, 284–294. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, H. , et al. IkappaBalpha ubiquitination is catalyzed by an SCF-like complex containing Skp1, cullin-1, and two F-box/WD40-repeat proteins, betaTrCP1 and betaTrCP2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1999, 256, 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- Hatakeyama, S. , et al. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of IkappaBalpha is mediated by a ubiquitin ligase Skp1/Cul 1/F-box protein FWD1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 3859–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, D.R. , et al. Heterozygous N-terminal deletion of IkappaBalpha results in functional nuclear factor kappaB haploinsufficiency, ectodermal dysplasia, and immune deficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 120, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Granados, E. , et al. A novel mutation in NFKBIA/IKBA results in a degradation-resistant N-truncated protein and is associated with ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency. Hum. Mutat. 2008, 29, 861–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temmerman, S.T. , et al. Defective nuclear IKKα function in patients with ectodermal dysplasia with immune deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 2012, 122, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J. , et al. FBW7-mediated ubiquitination and destruction of PD-1 protein primes sensitivity to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer. J. Immunother. Cancer 2022, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Matalon, O. , et al. Dephosphorylation of the adaptor LAT and phospholipase C-γ by SHP-1 inhibits natural killer cell cytotoxicity. Sci. Signal 2016, 9, ra54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, C.A. , et al. Deletion of the ubiquitin ligase CHIP leads to the accumulation, but not the aggregation, of both endogenous phospho- and caspase-3-cleaved tau species. J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 6985–6996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.H. , et al. CHIP-mediated hyperubiquitylation of tau promotes its self-assembly into the insoluble tau filaments. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 5599–5610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L. , et al. Tau Ubiquitination in Alzheimer's Disease. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 786353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. , et al. PINK1 Primes Parkin-Mediated Ubiquitination of PARIS in Dopaminergic Neuronal Survival. Cell Rep. 2017, 18, 918–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, J. , et al. Parkin and PINK1 mutations in early-onset Parkinson's disease: comprehensive screening in publicly available cases and control. J. Med. Genet. 2009, 46, 375–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, L.M. , et al. IKK phosphorylates Huntingtin and targets it for degradation by the proteasome and lysosome. J. Cell Biol. 2009, 187, 1083–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J. , et al. ALS-causing SOD1 mutants regulate occludin phosphorylation/ubiquitination and endocytic trafficking via the ITCH/Eps15/Rab5 axis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2021, 153, 105315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muranova, L.K. , et al. Mutations in HspB1 and hereditary neuropathies. Cell Stress. Chaperones 2020, 25, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerritsen, J.S. and F.M. White, Phosphoproteomics: a valuable tool for uncovering molecular signaling in cancer cells. Expert. Rev. Proteom. 2021, 18, 661–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, M. Ö. Karayel, and V. Demichev, Ubiquitinomics: History, methods, and applications in basic research and drug discovery. Proteomics 2022, 22, e2200074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, S.O. , et al. Ubiquitylomics: An Emerging Approach for Profiling Protein Ubiquitylation in Skeletal Muscle. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 2281–2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P. , et al. Global identification of phospho-dependent SCF substrates reveals a FBXO22 phosphodegron and an ERK-FBXO22-BAG3 axis in tumorigenesis. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornbeck, P.V. , et al. PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D512–D520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokheim, C. , et al. Systematic characterization of mutations altering protein degradation in human cancers. Mol. Cell 2021, 81, 1292–1308.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z. , et al. Elucidation of E3 ubiquitin ligase specificity through proteome-wide internal degron mapping. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 3377–3392.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M. , et al. ELM-the Eukaryotic Linear Motif resource-2024 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D442–D4d455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wu, G. , et al. Structure of a beta-TrCP1-Skp1-beta-catenin complex: destruction motif binding and lysine specificity of the SCF(beta-TrCP1) ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Cell 2003, 11, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, B. , et al. Structure of a Fbw7-Skp1-cyclin E complex: multisite-phosphorylated substrate recognition by SCF ubiquitin ligases. Mol. Cell 2007, 26, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlicky, S. , et al. An allosteric inhibitor of substrate recognition by the SCF(Cdc4) ubiquitin ligase. Nat. Biotechnol. 2010, 28, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horn-Ghetko, D. , et al. Ubiquitin ligation to F-box protein targets by SCF-RBR E3-E3 super-assembly. Nature 2021, 590, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welcker, M. , et al. Two diphosphorylated degrons control c-Myc degradation by the Fbw7 tumor suppressor. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabl7872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, K. , et al. Systemwide disassembly and assembly of SCF ubiquitin ligase complexes. Cell 2023, 186, 1895–1911.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Gimeno, A. and C. Galdeano, Drug Discovery Approaches to Target E3 Ligases. Chembiochem 2024, e202400656. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, P.D. E.S. Lander, and F. Zhang, Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell 2014, 157, 1262–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, A.V., L. W. Koblan, and D.R. Liu, Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 824–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y. and J.A. Doudna, CRISPR technology: A decade of genome editing is only the beginning. Science 2023, 379, eadd8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, S. , et al. Mutation of a PER2 phosphodegron perturbs the circadian phosphoswitch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 10888–10896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boretto, M. , et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is a target of the tumor-suppressor E3 ligase FBXW7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2309902121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arrendale, A. , et al. Synthesis of a phosphoserine mimetic prodrug with potent 14-3-3 protein inhibitory activity. Chem. Biol. 2012, 19, 764–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simonetta, K.R. , et al. Prospective discovery of small molecule enhancers of an E3 ligase-substrate interaction. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).