Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

02 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Funding: Increase investment in programs and policies to enable breastfeeding

- The International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes (The Code): Full implementation with legislation and effective enforcement

- Maternity protection in the workplace: Enact paid family leave and workplace policies

- Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI): Implement the 10 steps to successful breastfeeding in maternity facilities

- Breastfeeding counseling and training: Improve access to skilled breastfeeding counseling in health facilities

- Community support programs: Encourage networks that protect, promote, and support breastfeeding

- Monitoring systems: Track progress on policies, programs, and funding

- Infant and young child feeding support in emergencies: Invest in policies and programs to protect continued breastfeeding during emergency situations

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting

| Socio-demographic indicator | Philippines | Viet Nam |

| Population | 115 559 009 [80] | 98 186 856 [81] |

| Urban: rural | 48:52 [82] | 39:61 [82] |

| Life expectancy | 69.3 years [83] | 73.6 years [83] |

| Fertility rate | 1.9 (2022) [84] | 1.9 [83] |

| Institutional birth rate | 89% (2020) from 50.5% (2010) | 96.3% |

| Crude birth rate (per 1000 people) | 21.8 (2021) [79] | 15.0 (2021) [79] |

| Public: private hospitals | 40:60 | 86:14 |

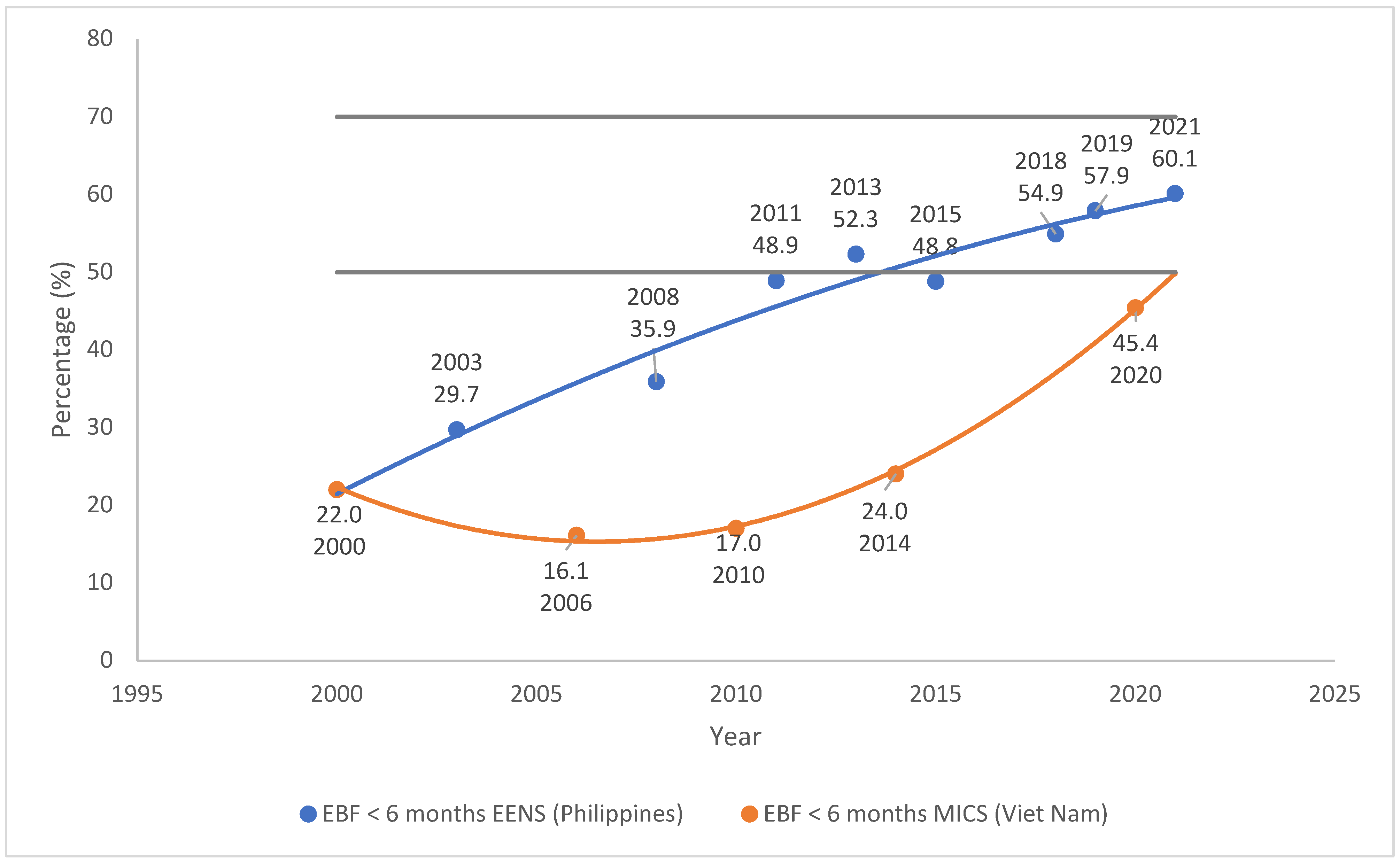

| Exclusive breastfeeding < 6 mo. | 34.0% (2008); 60.1% (2021) [62] | 17.0% (2010); 24.0% (2014); 45.4% (2021) [85] |

| Continued breastfeeding (% children 12-23 months fed breastmilk the previous day) | 57.1% (2022) [84] | 43.9% (2020) [85] |

| Immediate skin-to-skin contact | 71% [84] | 59% [86] |

| Stunting in children < 5 years | 26.7% (2021) [62] | 19.5% |

| Unemployment (2023) | 4.4% | 2.0% |

| Labor force participation rate | Men: 76.3%; Women: 52.9% [68] | Men: 74.3% Women: 61.6% [87] |

| Vulnerable employment 1 | 2022: Men: 30%; women: 38.5% [68] | 2022: Men: 46.9%; women: 57.3% [77] |

| Informal employment | 38.9% [88] | 2019: Men: 78.9 %, Women: 67.2% [78] |

| Commercial milk formula market | 2020: 8th largest globally: US$832.2 million in total US$7.6 annual per capita expenditure [65] |

2020: 4th largest globally: US$ 1,421.2 million in total US$14.6 annual per capita expenditure [65] |

2.3. Collating, Synthesizing, and Reporting the Results

2.4. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Policies to Enable Breastfeeding in the Philippines and Viet Nam

3.2. Implementation of Code Legislation in the Philippines and Viet Nam

3.3. Implementation of Maternity Protection Legislation in the Philippines and Viet Nam

- establishment of lactation rooms

- implementation of lactation breaks in workplaces

- workplaces are required to create a breastfeeding policy

- workplaces are required to comply with the Philippine Milk Code

- compliance with the Act is required to issue/renew business permits

- workplaces can apply for renewable exemptions in establishing lactation rooms if exemptible criteria are met

-

workplaces can apply for the Mother-Baby-Friendly Workplace Certification (valid for two years) by complying with this Act and fulfilling additional requirements set by the Department of Health.

- ∘

- Review and assessment of applications is assigned to local government units

- ∘

- Onsite inspection and approval of certification is conducted by DoH Centres for Health Development

3.4. Barriers to Implementation of Legislation to Enable Breastfeeding in the Philippines and Viet Nam

3.4.1. Barriers to Implementing Code Legislation in the Philippines

3.4.2. Barriers to Implementing Code Legislation in Viet Nam

3.4.3. Barriers to Implementing Maternity Protection Legislation in the Philippines

3.4.4. Barriers to Implementing Maternity Protection Legislation in Viet Nam

3.5. Recommendations to Improve the Implementation of Policies to Enable Breastfeeding in the Philippines and Viet Nam

4. Discussion

4.1. National Code Legislation in the Philippines and Viet Nam

4.2. Maternity Protection Legislation in the Philippines and Viet Nam

4.3. Cross-Sectoral Nature of Breastfeeding Policy Implementation

4.4. Feasibility of Recommendations

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Victora CG, Bahl R, Barros AJD, França GVA, Horton S, Krasevec J, et al. Breastfeeding in the 21st century: epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. Lancet. 2016;387:475–90. [CrossRef]

- Rollins NC, Bhandari N, Hajeebhoy N, Horton S, Lutter CK, Martines JC, et al. Why invest, and what it will take to improve breastfeeding practices? Lancet. 2016;387:491–504. [CrossRef]

- Walters DD, Phan LTH, Mathisen R. The cost of not breastfeeding: global results from a new tool. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34:407–17. [CrossRef]

- Smith JP, Iellamo A, Nguyen TT, Mathisen R. The volume and monetary value of human milk produced by the world’s breastfeeding mothers: Results from a new tool. Front Public Heal. 2023;11. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cordero S, Pérez-Escamilla R. What will it take to increase breastfeeding? Matern Child Nutr. 2022;18:1–5.

- Pérez-Escamilla R, Tomori C, Hernández-Cordero S, Baker P, Barros AJD, Bégin F, et al. Breastfeeding: crucially important, but increasingly challenged in a market-driven world. Lancet. 2023;401:472–85. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Nutrition Targets 2025 Policy Brief Series. Geneva; 2014.

- WHO-UNICEF. Global Breastfeeding Scorecard 2023. Geneva & New York; 2023.

- World Health Organization (WHO). International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes. Geneva; 1981.

- WHO & UNICEF. Innocenti Declaration on the Protection, Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding. New York; 1990.

- WHO & UNICEF. Global Strategy for Infant and Young Child Feeding. Geneva; 2003.

- Alive & Thrive, IBFAN. Protecting Breastfeeding Throughout History: The Evolution of the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes. 2021.

- Baumslag N. Cicely Delphine Williams: Doctor of the World’s Children. J Hum Lact. 2005;21:6–7. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Code and subsequent resolutions. Nutrition and Food Safety. 2024. https://www.who.int/teams/nutrition-and-food-safety/food-and-nutrition-actions-in-health-systems/code-and-subsequent-resolutions. Accessed 18 Nov 2024.

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). What I Should Know About “the Code”: A guide to implementation, compliance and identifying violations. New York; 2023.

- International Code Documentation Centre (ICDC). International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes and relevant WHA resolutions. Penang; 2022.

- WHO UNICEF and IBFAN. Marketing of breast-milk substitutes: National implementation of the International Code, status report 2024. Geneva; 2024.

- Rollins N, Piwoz E, Baker P, Kingston G, Mabaso KM, McCoy D, et al. Marketing of commercial milk formula: a system to capture parents, communities, science, and policy. Lancet. 2023;401:486–502. [CrossRef]

- Baker P, Smith JP, Garde A, Grummer-Strawn LM, Wood B, Sen G, et al. The political economy of infant and young child feeding: confronting corporate power, overcoming structural barriers, and accelerating progress. Lancet. 2023;401:503–24. [CrossRef]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). C003 - Maternity Protection Convention, 1919 (No. 3). 1919. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID:312148. Accessed 4 Oct 2023.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Maternity Protection Convention (No. 183). 2000. https://normlex.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C183. Accessed 18 Nov 2024.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). R191 - Maternity Protection Recommendation, 2000 (No. 191). 2000. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/de/f?p=1000:12100:0::NO::P12100_INSTRUMENT_ID,P12100_LANG_CODE:312529,en:NO. Accessed 23 Nov 2020.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). International Labour Standards on Maternity protection. Labour standards. 2024. https://www.ilo.org/global/standards/subjects-covered-by-international-labour-standards/maternity-protection/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed 22 Feb 2024.

- Gribble KD, Smith JP, Gammeltoft T, Ulep V, Van Esterik P, Craig L, et al. Breastfeeding and infant care as ‘sexed’ care work: reconsideration of the three Rs to enable women’s rights, economic empowerment, nutrition and health. Front Public Heal. 2023;11:1–16. [CrossRef]

- Bettinelli ME, Smith JP, Haider R, Sulaiman Z, Stehel E, Young M, et al. ABM Position Statement: Paid Maternity Leave—Importance to Society, Breastfeeding, and Sustainable Development. Breastfeed Med. 2024;19:141–51. [CrossRef]

- Chai Y, Nandi A, Heymann J. Does extending the duration of legislated paid maternity leave improve breastfeeding practices? Evidence from 38 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Heal. 2018;3:e001032. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Rosenblatt D, Garmendia M-L. Maternity Leave and Its Impact on Breastfeeding: A Review of the Literature. Breastfeed Med. 2018;13:589–97. [CrossRef]

- Nandi A, Hajizadeh M, Harper S, Koski A, Strumpf EC, Heymann J. Increased Duration of Paid Maternity Leave Lowers Infant Mortality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Quasi-Experimental Study. PLOS Med. 2016;13:e1001985. [CrossRef]

- Aitken Z, Garrett CC, Hewitt B, Keogh L, Hocking JS, Kavanagh AM. The maternal health outcomes of paid maternity leave: A systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:32–41. [CrossRef]

- Heshmati A, Honkaniemi H, Juárez SP. The effect of parental leave on parents’ mental health: a systematic review. Lancet Public Heal. 2023;8:e57–75. [CrossRef]

- Franzoi IG, Sauta MD, De Luca A, Granieri A. Returning to work after maternity leave: a systematic literature review. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Charmes J, International Labour Office (ILO). The unpaid care work and the labour market: an analysis of time use data based on the latest world compilation of time-use surveys. Geneva: ILO; 2019.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Ratifications of C183 - Maternity Protection Convention, 2000 (No. 183). https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=1000:11300:0::NO:11300:P11300_INSTRUMENT_ID:312328. Accessed 8 Jan 2024.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Care at work: Investing in care leave and services for a more gender equal world of work - Executive Summary. Geneva; 2022.

- Pereira-Kotze C, Doherty T, Faber M. Maternity protection for female non-standard workers in South Africa: the case of domestic workers. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022;22:657. [CrossRef]

- Ulep VG, Zambrano P, Datu-Sanguyo J, Vilar-Compte M, Belismelis GMT, Pérez-Escamilla R, et al. The financing need for expanding paid maternity leave to support breastfeeding in the informal sector in the Philippines. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17:1–8. [CrossRef]

- Stumbitz B, Lewis S, Kyei AA, Lyon F. Maternity protection in formal and informal economy workplaces: The case of Ghana. World Dev. 2018;110:373–84. [CrossRef]

- Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC). General Comment 15 on the right of the child to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health (art. 24). 2013.

- Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC). The Convention on the Rights of the Child. 1989.

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Joint statement by the UN Special Rapporteurs on the Right to Food, Right to Health, the Working Group on Discrimination against Women in law and in practice, and the Committee on the Rights of the Child in support of increased efforts to promote, support. 2016. https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2016/11/joint-statement-un-special-rapporteurs-right-food-right-health-working-group. Accessed 19 May 2024.

- Grummer-Strawn LM, Zehner E, Stahlhofer M, Lutter C, Clark D, Sterken E, et al. New World Health Organization guidance helps protect breastfeeding as a human right. Matern Child Nutr. 2017;13:e12491. [CrossRef]

- Joyce CM, Hou SS-Y, Ta BTT, Vu DH, Mathisen R, Vincent I, et al. The Association between a Novel Baby-Friendly Hospital Program and Equitable Support for Breastfeeding in Vietnam. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:6706. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Cordero S, Pérez-Escamilla R, Zambrano P, Michaud-Létourneau I, Lara-Mejía V, Franco-Lares B. Countries’ experiences scaling up national breastfeeding, protection, promotion and support programmes: Comparative case studies analysis. Matern Child Nutr. 2022;18:1–27. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TT, Weissman A, Cashin J, Ha TT, Zambrano P, Mathisen R. Assessing the Effectiveness of Policies Relating to Breastfeeding Promotion, Protection, and Support in Southeast Asia: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2020;9:e21286. [CrossRef]

- Michaud-Létourneau I, Gayard M, Pelletier DL. Contribution of the Alive & Thrive-UNICEF advocacy efforts to improve infant and young child feeding policies in Southeast Asia. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:1–14. [CrossRef]

- Michaud-Létourneau I, Gayard M, Mathisen R, Phan LTH, Weissman A, Pelletier DL. Enhancing governance and strengthening advocacy for policy change of large Collective Impact initiatives. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:1–12. [CrossRef]

- Payán DD, Zahid N, Glenn J, Tran HTT, Huong TTT, Moucheraud C. Implementation of two policies to extend maternity leave and further restrict marketing of breast milk substitutes in Vietnam: a qualitative study. Health Policy Plan. 2022;37:472–82. [CrossRef]

- Harris J, Frongillo EA, Nguyen PH, Kim SS, Menon P. Changes in the policy environment for infant and young child feeding in Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia, and the role of targeted advocacy. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:492. [CrossRef]

- Baker P, Zambrano P, Mathisen R, Singh-Vergeire MR, Escober AE, Mialon M, et al. Breastfeeding, first-food systems and corporate power: a case study on the market and political practices of the transnational baby food industry and public health resistance in the Philippines. Global Health. 2021;17:125. [CrossRef]

- Baker P, Santos T, Neves PA, Machado P, Smith J, Piwoz E, et al. First-food systems transformations and the ultra-processing of infant and young child diets: The determinants, dynamics and consequences of the global rise in commercial milk formula consumption. Matern Child Nutr. 2021;17:1–18. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y. Global infant formula products market: estimations and forecasts for production and consumption. China Dairy. 2018; July:4 pp.

- Koe T. Growth 2024: Why South East Asian countries are the emerging nutrition markets to look out for this year 03-Jan-2024 By Tingmin Koe. Nutraingredients Asia. 2024.

- Michaud-Létourneau I, Gayard M, Pelletier DL. Translating the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes into national measures in nine countries. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TT, Tran HTT, Cashin J, Nguyen VDC, Weissman A, Nguyen TT, et al. Implementation of the Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes in Vietnam: Marketing Practices by the Industry and Perceptions of Caregivers and Health Workers. Nutrients. 2021;13:2884. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TT, Cashin J, Ching C, Baker P, Tran HT, Weissman A, et al. Beliefs and Norms Associated with the Use of Ultra-Processed Commercial Milk Formulas for Pregnant Women in Vietnam. Nutrients. 2021;13:4143. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TT, Cashin J, Tran HTT, Vu DH, Nandi A, Phan MT, et al. Awareness, Perceptions, Gaps, and Uptake of Maternity Protection among Formally Employed Women in Vietnam. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:4772. [CrossRef]

- Samaniego JAR, Maramag CC, Castro MC, Zambrano P, Nguyen TT, Datu-Sanguyo J, et al. Implementation and Effectiveness of Policies Adopted to Enable Breastfeeding in the Philippines Are Limited by Structural and Individual Barriers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:10938. [CrossRef]

- Joyce CM, Nguyen TT, Pham TN, Mathisen R, Nandi A. The impact of Vietnam’s 2013 extension of paid maternity leave on women’s labour force participation. J Asian Public Policy. 2023;00:1–18. [CrossRef]

- Maramag CC, Samaniego JAR, Castro MC, Zambrano P, Nguyen TT, Cashin J, et al. Maternity protection policies and the enabling environment for breastfeeding in the Philippines: a qualitative study. Int Breastfeed J. 2023;18:60. [CrossRef]

- Philippine Statistics Authority. Special Release: 2022 National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) Key Indicators - Health Insurance Coverage. 2023:2–4. https://rssocar.psa.gov.ph/system/files/attachment-dir/CAR-SSR-2023-23_2022-NDHS-Insurance-Coverage.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2024.

- DOST-FNRI. Expanded National Nutrition Survey: 2019 Results - Nutritional Status of Filipino Infants and Young Children (0-23 months). 2019. https://www.fnri.dost.gov.ph/images/sources/eNNS2018/Infants_and_Young_Children_0-23m.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2024.

- DOST-FNRI. Expanded National Nutrition Survey: 2021 Survey Results. 2022;282. https://www.scribd.com/document/747228306/2021-ENNS-National-Results-Dissemination. Accessed 18 Nov 2024.

- Bhattacharjee N V., Schaeffer LE, Hay SI, Lu D, Schipp MF, Lazzar-Atwood A, et al. Mapping inequalities in exclusive breastfeeding in low- and middle-income countries, 2000–2018. Nat Hum Behav. 2021;5:1027–45. [CrossRef]

- Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). Status of ratification: Interactive Dashboard. 2024. https://indicators.ohchr.org/. Accessed 8 Apr 2024.

- Wood B, O’Sullivan D, Baker P, Nguyen T, Ulep V, McCoy D. Who Benefits from Undermining Breastfeeding? Exploring the global commercial milk formula industry’s generation and distribution of wealth and income. 2022.

- Official Gazette- Republic of the Philippines. Republic Act 11210. An Act Increasing the Maternity Leave Period to One Hundred Five (105) Days for Female Workers with an Option to Extend for an Additional Thirty (30) Days Without Pay, and Granting an Additional Fifteen (15) Days for Solo Mothers, and. Official Gazette- Republic of the Philippines. 2019;1–10. http://legacy.senate.gov.ph/republic_acts/ra 11210.pdf. Accessed 18 Nov 2024.

- Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA). Labor Force Survey Media Release. Quezon City; 2023.

- World Bank. Philippines Gender Landscape. 2024. https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/economies/philippines. Accessed 16 Nov 2024.

- Cabegin ECA. Policy Brief: The Informal Labor Carries the Brunt of a COVID-19 – induced Economic Recession: The Need for Stronger Transition Policies to Formality. Quezon City; 2022.

- UNICEF. UNICEF Data Warehouse: Viet Nam indicator - exclusive breastfeeding. 2023. https://data.unicef.org/resources/data_explorer/unicef_f/?ag=UNICEF&df=GLOBAL_DATAFLOW&ver=1.0&dq=VNM.NT_BF_EXBF.&startPeriod=1970&endPeriod=2023. Accessed 5 Oct 2023.

- UNICEF. Viet Nam SDGCW (Sustainable Development Goal Indicators on Children and Women) Survey 2020-2021: Infant and Young Child Feeding. 2021;5–6.

- WHO & UNICEF. The extension of the 2025 Maternal, Infant and Young Child nutrition targets to 2030: Discussion paper. 2019.

- Nguyen TT, Cashin J, Tran HT, Hoang TA, Mathisen R, Weissman A, et al. Birth and newborn care policies and practices limit breastfeeding at maternity facilities in Vietnam. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1–15. [CrossRef]

- Interesse G. Vietnam’s Baby Formula Market: Key Considerations for Foreign Brands and Exporters. Vietnam Briefing. 2023. https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/vietnams-baby-formula-market-key-considerations-for-foreign-brands-and-exporters.html/. Accessed 11 Jan 2024.

- WHO & UNICEF. How the marketing of formula milk influences our decisions on infant feeding. Geneva; 2022.

- YCP Solidiance. Vietnam Market Study on Formula Milk. 2020; October. https://www.gov.br/empresas-e-negocios/pt-br/invest-export-brasil/exportar/conheca-os-mercados/pesquisas-de-mercado/estudo-de-mercado.pdf/formulamilkhanoiengl.pdf. Accessed 16 Nov 2024.

- World Bank. Viet Nam Gender Landscape. 2024. https://genderdata.worldbank.org/en/economies/vietnam. Accessed 16 Nov 2024.

- Barcucci V, Cole W, Rosina G. Research brief: Gender and the Labor Market in Vietnam. Hanoi, Viet Nam; 2021.

- The World Bank Group. Birth rate, crude (per 1,000 people). 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.CBRT.IN?locations=VN. Accessed 31 May 2024.

- World Bank. Population total - Philippines. 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=PH. Accessed 23 Feb 2024.

- World Bank. Population, total - Viet Nam. 2022. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=VN. Accessed 23 Feb 2024.

- World Bank. Rural population (% of total population). 2023. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS. Accessed 18 Nov 2024.

- World Bank. Health Nutrition and Population Statistics. 2021. https://databank.worldbank.org/source/health-nutrition-and-population-statistics. Accessed 4 Mar 2024.

- Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), ICF. Philippine National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS): Final Report. Quezon City, Philippines and Rockville, Maryland, USA; 2023.

- General Statistics Office, UNICEF. Survey Measuring Viet Nam Sustainable Development Goal Indicators on Children and Women 2020-2021, Survey Findings Report. Ha Noi, Viet Nam; 2021.

- WHO Western Pacific Region, UNICEF. Action Plan for Healthy Newborn Infants in the Western Pacific Region (2014-2020): Second biennial progress report (2016–2017). 2018.

- General Statistics Office (GSO) [Viet Nam]. Report on Labour Force Survey 2021. Ha Noi, Viet Nam; 2022.

- Philippines Statistics Authority. Philippines Labor Force Survey December 2023. 2023. https://psa.gov.ph/statistics/labor-force-survey/node/1684062347. Accessed 15 Mar 2024.

- WHO, UNICEF, IBFAN. Marketing of breast-milk substitutes: national implementation of the international Code, status report 2022. Geneva; 2022.

- UNICEF East Asia & Pacific Region. Strengthening Implementation of the Breast-milk Substitutes Code in Southeast Asia: Putting Child Nutrition First. 2021.

- Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) [Philippines]. Renumbering of the Labor Code of the Philippines, as Amended. Manila, Philippines and Calverton, Maryland USA; 2015.

- Official Gazette- Republic of the Philippines. Expanded Breastfeeding Promotion Act of 2009. Metro Manila; 2010.

- WHO & UNICEF. NetCode toolkit. Monitoring the marketing of breast-milk substitute: protocol for ongoing monitoring systems. 2017.

- Nguyen TT, Darnell A, Weissman A, Cashin J, Withers M, Mathisen R, et al. National nutrition strategies that focus on maternal, infant, and young child nutrition in Southeast Asia do not consistently align with regional and international recommendations. Matern Child Nutr. 2020;16:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen TT, Huynh NL, Huynh PN, Zambrano P, Withers M, Cashin J, et al. Bridging the evidence-to-action gap: enhancing alignment of national nutrition strategies in Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam with global and regional recommendations. Front Nutr. 2024;10 January:1–11. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidance on regulatory measures aimed at restricting digital marketing of breast-milk substitutes. Geneva; 2023.

- Giang HTN, Duy DTT, Vuong NL, Ngoc NTT, Pham TT, Duc NTM, et al. Prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of an infant’s life and associated factors in a low–middle income country. Int Breastfeed J. 2023;18:47. [CrossRef]

- Republic of the Philippines House of Representatives. Bill encouraging corporate social responsibility passed in the House. Press and Public Affairs Bureau. 2023. https://www.congress.gov.ph/press/details.php?pressid=12521. Accessed 19 Mar 2024.

- Capili DIS, Datu-Sanguyo J, Mogol-Sales CS, Zambrano P, Nguyen TT, Cashin J, et al. Cross-sectional multimedia audit reveals a multinational commercial milk formula industry circumventing the Philippine Milk Code with misinformation, manipulation, and cross-promotion campaigns. Front Nutr. 2023;10:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Brewer BK, Salgado R V, Alexander E, Lo A, Bhatia R. National Assessment on the Compliance with the Code and the National Measures: Philippines Report. Rockville, Maryland; 2021.

- Reinsma K, Ballesteros AJC, Bucu RAA, Dizon TS, Jumalon NJU, Ramirez LC, et al. Mother-Baby Friendly Philippines: Using Citizen Reporting to Improve Compliance to the International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes. Glob Heal Sci Pract. 2022;10:e2100071. [CrossRef]

- Perez R. You Can Now File Your SSS Maternity Notification, Report Milk Code Violations Via Apps. 2020. https://www.smartparenting.com.ph/life/news/sss-mobile-app-and-mother-baby-friendly-app-a00041-20190706#. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

- Philippines Department of Health. Mother-Baby Friendly Philippines. https://mbfp.doh.gov.ph/.

- World Vision Development Foundation. Mother-Baby Friendly PH App. 2019. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/mbf-ph/id1260502250.

- FHI Solutions. VIVID: Virtual Violations Detector. 2022. https://www.fhisolutions.org/innovation/vivid-virtual-violations-detector/. Accessed 18 Jan 2024.

- Alive & Thrive. News: In a first, innovative tool reveals findings on Code violations, showing potential to disrupt digital marketing of commercial milk formula. 2023. https://www.aliveandthrive.org/en/news/in-a-first-innovative-tool-reveals-findings-on-code-violations-showing-potential-to-disrupt-digital. Accessed 23 Feb 2024.

- Alive & Thrive, Hekate. VIVID: Virtual Violations Detector. 2024. https://code.corporateaccountabilitytool.org/vietnam. Accessed 23 Feb 2024.

- Backholer K, Nguyen L, Vu D, Ching C, Baker P, Mathisen R. Violations of Vietnamese laws related to the online marketing of breastmilk substitutes: Detections using a virtual violations detector. Matern Child Nutr. 2025;21(1):e13680. [CrossRef]

- Pereira-Kotze C, Malherbe K, Faber M, Doherty T, Cooper D. Legislation and Policies for the Right to Maternity Protection in South Africa: A Fragmented State of Affairs. J Hum Lact. 2022;089033442211080.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Making the right to social security a reality for domestic workers: A global review of policy trends, statistics and extension strategies. Geneva: ILO; 2022.

- Alive & Thrive. Centers of Excellence for Breastfeeding Model in Viet Nam. 2023.

- Alive & Thrive. Toolkit to support breastfeeding women in the workplace: For reference in Viet Nam. Hanoi, Viet Nam; 2023.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Healthy Beginnings for a Better Society: Breastfeeding in the Workplace is Possible - A Toolkit. Makati City; 2015.

- Vu K, Glewwe P. Maternity benefits mandate and women’s choice of work in Vietnam. World Dev. 2022;158:105964. [CrossRef]

- Alive & Thrive, Scaling Up Nutrition. Report on Maternity Protection Policy Expansion for female workers in non-formal sector. 2023.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Care at work: Investing in care leave and services for a more gender equal world of work. Geneva; 2022.

- Boockmann B. The Ratification of ILO Conventions: A Failure Time Analysis. Mannheim; 2000.

- Smith JP, Borg B, Iellamo A, Nguyen TT, Mathisen R. Innovative financing for a gender-equitable first-food system to mitigate greenhouse gas impacts of commercial milk formula: investing in breastfeeding as a carbon offset. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2023;7:1–9. [CrossRef]

- ASEAN, UNICEF, Alive & Thrive. Guidelines and Minimum Standards for the Protection, Promotion and Support of Breastfeeding and Complementary Feeding. Jakarta; 2022.

- ASEAN, UNICEF. Minimum standards and guidelines on actions to protect children from the harmful impact of marketing of food and non-alcoholic beverages in the ASEAN region. Jakarta; 2023.

- ASEAN. ASEAN Leaders’ Declaration on Ending All Forms of Malnutrition. 2017.

- Skekar M, Okamura KS, D’Alimonte M, Dell’Aria C. Financing the Global Nutrition Targets: Progress to Date. In: Skekar M, Okamura KS, Vilar-Compte M, Dell’Aria C, editors. Investment Framework for Nutrition 2024. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2024. p. 231–67.

- Smith J, Baker P, Mathisen R, Long A, Rollins N, Waring M. A proposal to recognize investment in breastfeeding as a carbon offset. Bull World Health Organ. 2024;102:336–43. [CrossRef]

| Title, author, year | Country, year of data collection | Study design | Study sample, data collection techniques and data used | Aim | Policy type investigated |

| Translating the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes into national measures in nine countries [53] | Viet Nam, May 2015 to March 2017. | Real-time evaluation | Participant observation 16 key informant meetings 3 in-depth interviews (IDIs) Reflective practice; Desk review |

To document the extent to which policy objectives were (or were not) achieved in 9 countries (including Viet Nam) and to identify the key drivers of policy changes. | Breastfeeding protection: the Code |

| Implementation of the Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes in Vietnam: marketing practices by the industry and perceptions of caregivers and health workers [54] | Viet Nam, May to July 2020. | Mixed methods, cross-sectional | Quantitative survey of 268 pregnant women and 726 mothers of infants aged 0–11 months. Qualitative IDIs with 70 participants, incl. subsets of interviewed women (n = 39), policymakers, media executives, and health workers (n = 31). |

To examine the enactment and implementation of the Code of Marketing of Breast-Milk Substitutes (the Code) in Viet Nam, focusing on marketing practices by the baby food industry and perceptions of caregivers, health workers, and policymakers. | Breastfeeding protection: the Code |

| Beliefs and norms associated with the use of ultra-processed commercial milk formulas for pregnant women in Vietnam [55] | Viet Nam, May to July 2020. | Post-hoc analysis of quantitative survey data | Quantitative interviews with 268 pregnant women in their second and third trimesters from two provinces and one municipality representing diverse communities in Vietnam. | To examine the association between the use of commercial milk formula for pregnant women and related beliefs and norms among pregnant women in Vietnam. | Breastfeeding protection: the Code |

| Awareness, perceptions, gaps, and uptake of maternity protection among formally employed women in Vietnam [56] | Viet Nam, May to July 2020. | Mixed methods, cross-sectional | Quantitative interviews with 494 formally employed female workers (107 pregnant and 387 mothers of infants). IDIs with a subset of women (n = 39). |

To examine the uptake of Vietnam’s maternity protection policy in terms of entitlements and awareness, perceptions, and gaps in implementation through the lens of formally employed women. | Maternity protection |

| Implementation and effectiveness of policies adopted to enable breastfeeding in the Philippines are limited by structural and individual barriers [57] | The Philippines, December 2020 to March 2021. | Mixed methods, cross-sectional | Desk review of policies and documents IDIs with 100 caregivers, employees, employers, health workers, and policymakers in the Greater Manila Area. |

This study assesses the adequacy and potential impact of breastfeeding policies, as well as the perceptions of stakeholders of their effectiveness and how to address implementation barriers. | Breastfeeding protection promotion and support, including the Code and maternity protection |

| The impact of Vietnam’s 2013 extension of paid maternity leave on women’s labour force participation [58] |

Viet Nam, 2015-2018 (data from Labor Force Surveys) | Regression discontinuity (RD) design | RD to evaluate the impact of paid maternity leave on the probability of women holding a job and formal labour contract 3-5 years after giving birth. | To evaluate whether the expansion of Vietnam’s paid maternity leave policy was associated with improved long-term labor outcomes for Vietnamese women | Maternity protection |

| Maternity protection policies and the enabling environment for breastfeeding in the Philippines: a qualitative study [59] | The Philippines, December 2020 to April 2021 | Mixed methods, cross-sectional | Desk review of policies, guidelines, and related documents on maternity protection. IDIs with 87 mothers and partners, employers, and authorities from government and non-government organizations in the Greater Manila Area. |

This study reviewed the content and implementation of maternity protection policies in the Philippines, assessed their role in enabling recommended breastfeeding practices, and identified bottlenecks to successful implementation. | Maternity protection |

| Provision | Philippines | Viet Nam | Highest scores |

| Scope | 20 | 16 | 20 |

| Monitoring and enforcement | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Informational / educational materials | 9 | 5 | 10 |

| Promotion to general public | 10 | 20 | 20 |

| Promotion in health facilities | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Engagement with health workers and systems | 14 | 10 | 15 |

| Labeling | 12 | 8 | 15 |

| Total | 85 | 79 | 100 |

| ILO Maternity Protection Convention 183 | ILO Maternity Protection Recommendation 183 | Philippines | Viet Nam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paid maternity leave | ||||

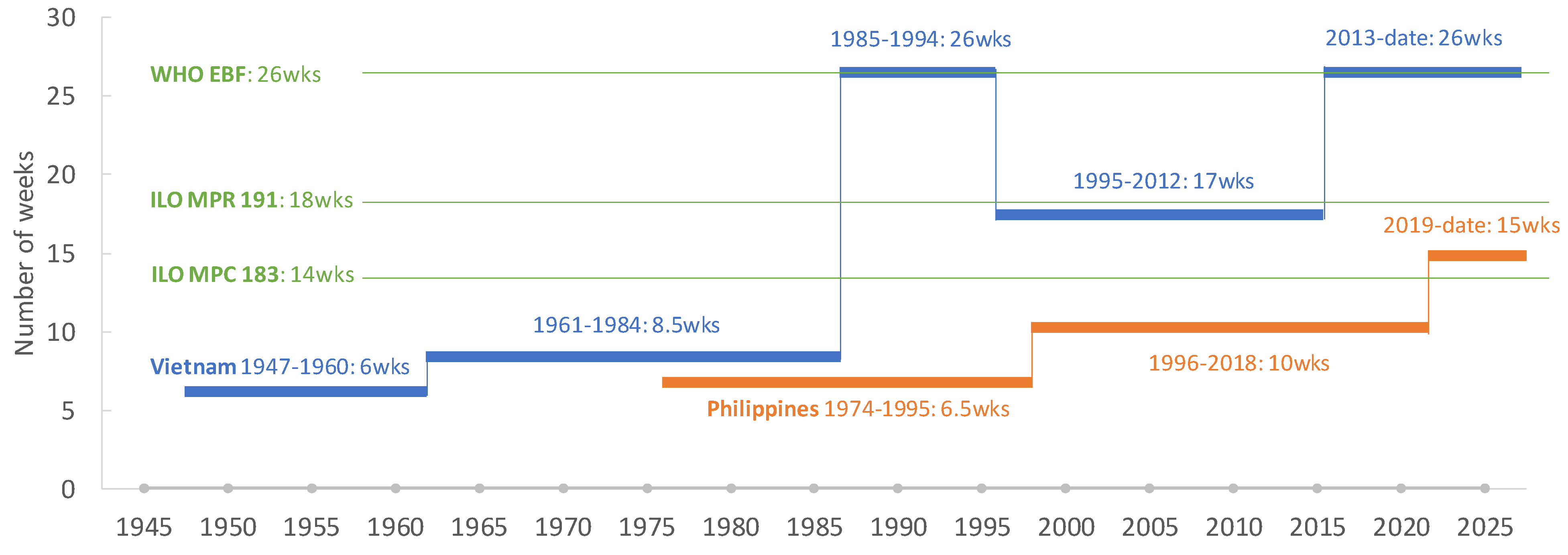

| Duration of maternity leave in national legislation | Mandates minimum maternity leave of 14 weeks. | Recommends increasing maternity leave to 18 weeks. | 15 weeks (105 days), option to extend an additional 30 days | 26 weeks (6 months) |

| Amount of maternity leave cash payments (% of previous earnings) |

Adequate to keep mother and child healthy, out of poverty, especially women in informal economy; >67% of previous earnings. | Recommends increasing maternity leave cash payments to 100%, when possible. | 100% for 15 weeks (105 days) | 100% |

| Source of funding maternity leave cash payments | Employers should not be individually liable for direct costs of maternity leave. Cash benefits shall be provided through compulsory social insurance, public funds or non-contributory social assistance to women who do not qualify for benefits out of social insurance; especially for informal economy or self-employed workers. | Social insurance and employer | Social insurance only | |

| Maternity leave cash payments for self-employed workers | Yes, but only for workers who are actively paying members of the Social Security System | No | ||

| Source of funding | 7 days (4 paid), employer | 5 days, social insurance | ||

| Breastfeeding (nursing) breaks | ||||

| Entitlement to paid nursing breaks | Women should be provided with the right to one or more daily breaks, or daily reduction of work hours to breastfeed. The period during which this is allowed, the number, duration of breaks and procedures for reducing daily work hours shall be determined by national law. | Frequency and length of nursing breaks should be adapted to needs. It should be possible to combine time allotted for daily nursing breaks to allow reduced work hours at beginning/ end of the workday. Where practical, provision should be made for establishing hygienic nursing facilities at or near the workplace. | Paid | Paid |

| Number of daily nursing breaks | Not limited | Not specified | ||

| Total daily nursing break duration | 40 minutes | 60 minutes | ||

| Period when nursing breaks are allowed by law | Not specified | Until child is 12 months | ||

| Statutory provisions for working nursing facilities | All workers | Mandatory at workplaces ≥ 1,000 female employees | ||

| The Philippines | Viet Nam |

|---|---|

| 1. Barriers to implementing Code legislation | |

| Structural gaps in legislation. Ambiguity surrounding monitoring responsibilities and irregular inspections. Weak sanctions limit enforcement. Some consider existing legislation to be too strict. |

Gaps in legislation: insufficient scope, inadequate regulation of information and education materials, engagement with health workers and systems, and labeling. Conflicting advertising regulations exist regarding functional food, supplemented food, food for special medical purposes for children under 24 months, and breastmilk substitutes. Legislative gaps mean company representatives still access health facilities and obtain contact information from pregnant women and new mothers. Gaps in scope allow rampant cross-promotion, especially of CMF-PW with CMF for infants. Routine monitoring is limited, relies on self-assessment, and data is unavailable. Limited enforcement due to human resource constraints and pro-industry tendencies. Gaps are illustrated by continued violations. |

| 2. Barriers to implementing maternity protection | |

| Informal sector workers are not reached by maternity protection entitlements. Length of paid maternity leave less than WHO recommendation of EBF to six months. Implementation of workplace lactation support policies varies according to workplace and type of work. Employers recognize the value of maternity protection but perceive disadvantages to policies with some not supporting workplace lactation. Sense of acceptance that breastfeeding will stop when women return to work. No systematic enforcement and monitoring. |

Low knowledge among all mothers of the full set of maternity protection entitlements. Perceived barriers to using entitlements. Disparities in knowledge and uptake by occupation and sector. Limited access to cash entitlements while on maternity leave and low maternity allowance do not protect mothers and infants from poverty due to low contribution to social security fund before maternity leave. Discrimination is based on pregnancy and childbirth. Unintended negative consequences on labor force participation. |

| Recommendations to improve implementation of Code legislation in the Philippines and Viet Nam |

|

| Recommendations to improve implementation of maternity protection legislation in the Philippines and Viet Nam |

|

| Philippines (“Substantially aligned” with the Code) |

|

| Viet Nam (“Substantially aligned” with the Code) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).