Submitted:

30 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Reasons for the Simplicity of Electric Vehicle Powertrain Designs

3. Advanced Electric Car and Heavy Vehicle Engines

Fixed Ratio Gearboxes, Tesla and GKN Gearbox Types

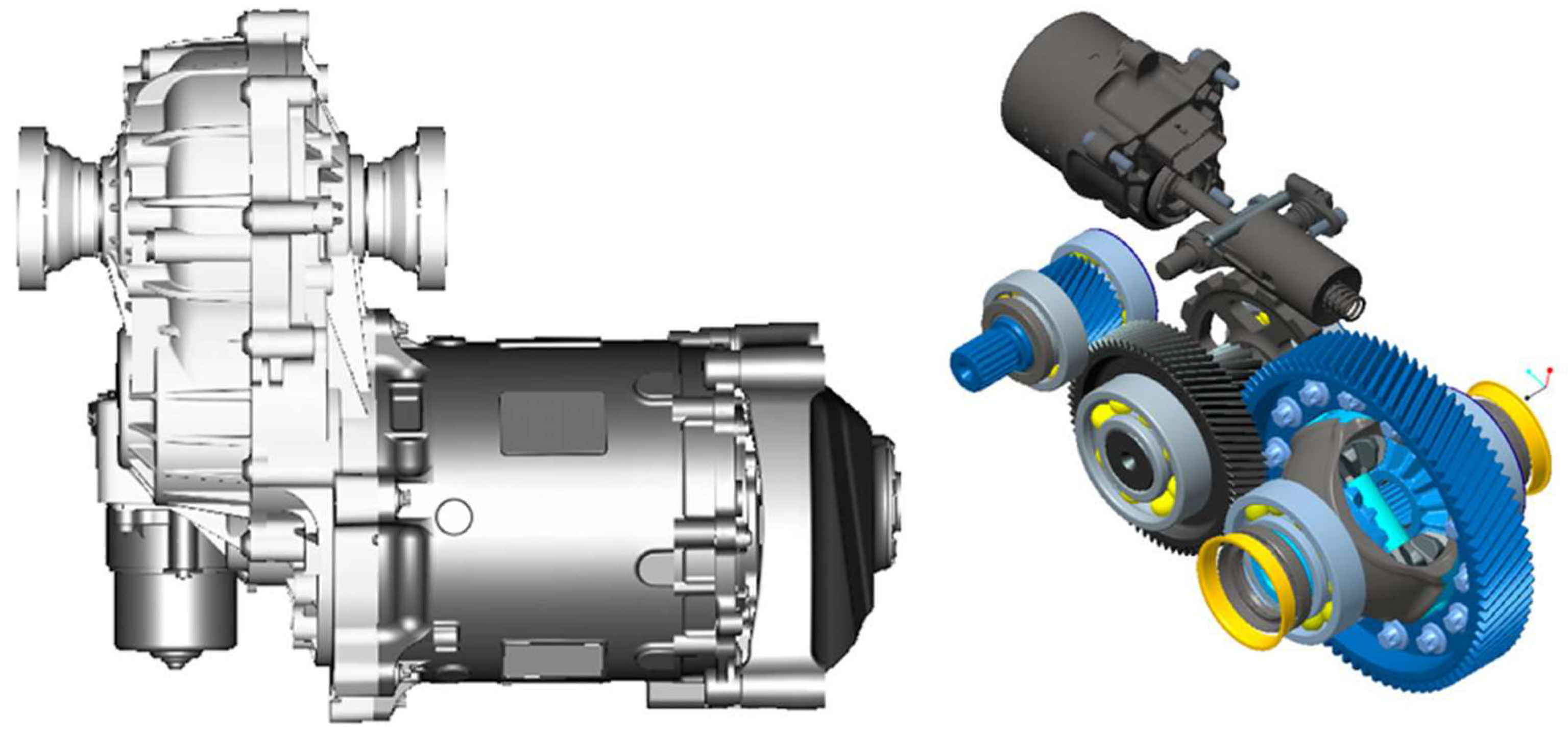

GKN Gen II eAxle Constant Ratio Gearbox

GKN Co-Axial eAxles

Two-Speed Gearboxes with Optional Gear Ratio

GKN Two-Speed eAxle Gearbox

AVL Two-Speed Gearboxes with Double Clutch

Multi-Speed Drives

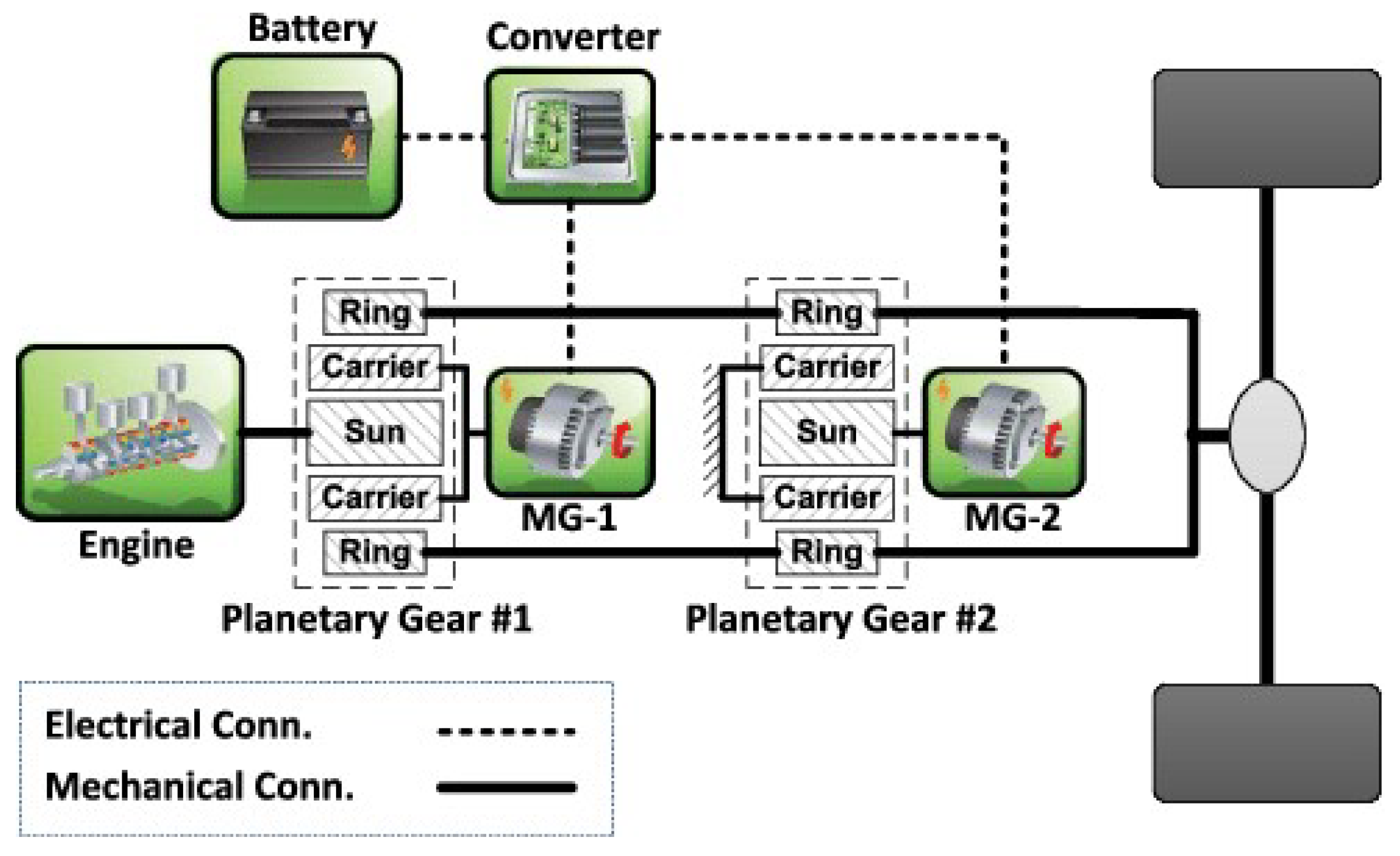

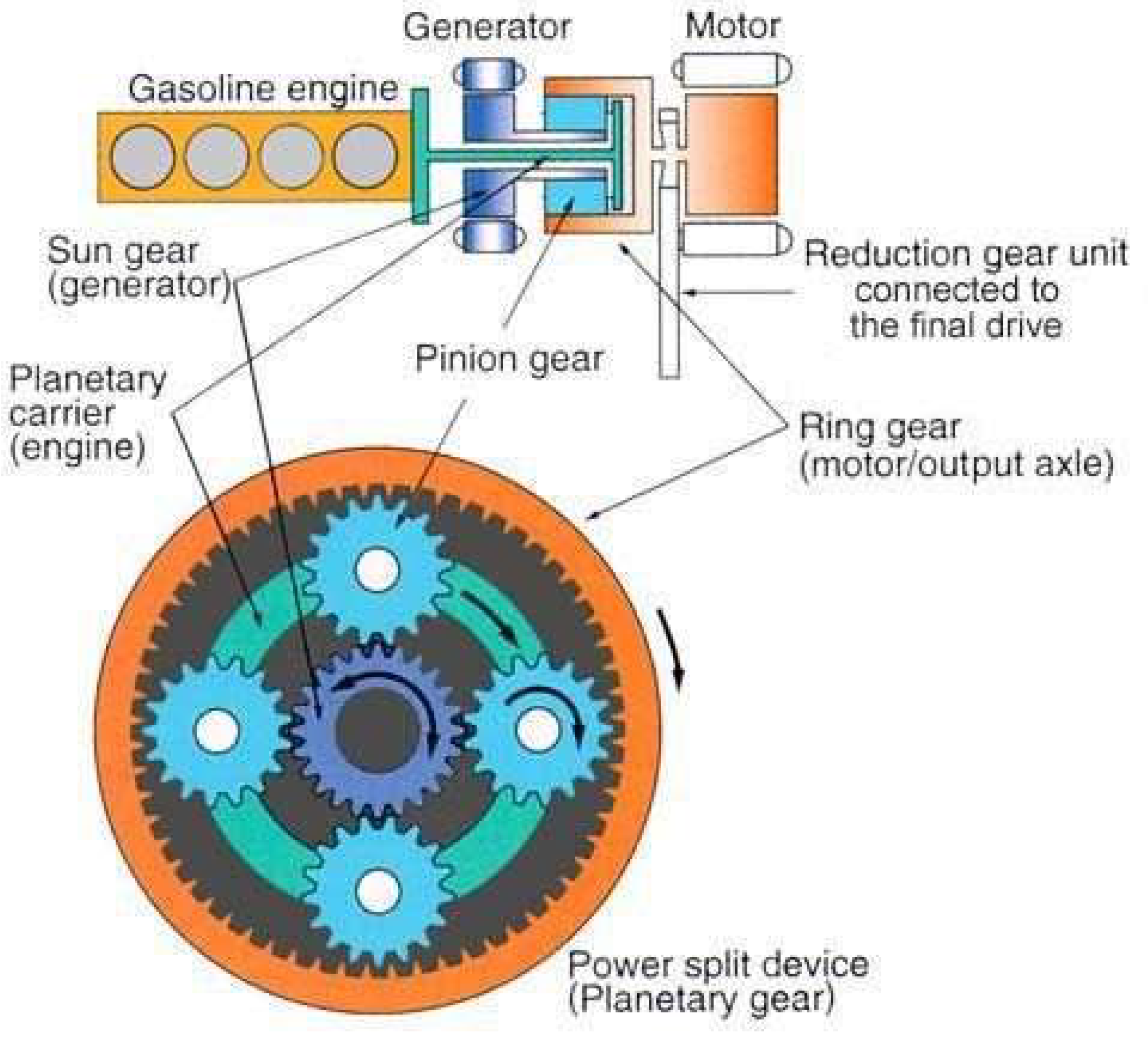

Hybrid Drive Trains

- Toyota Prius

Multimode eTransmissions

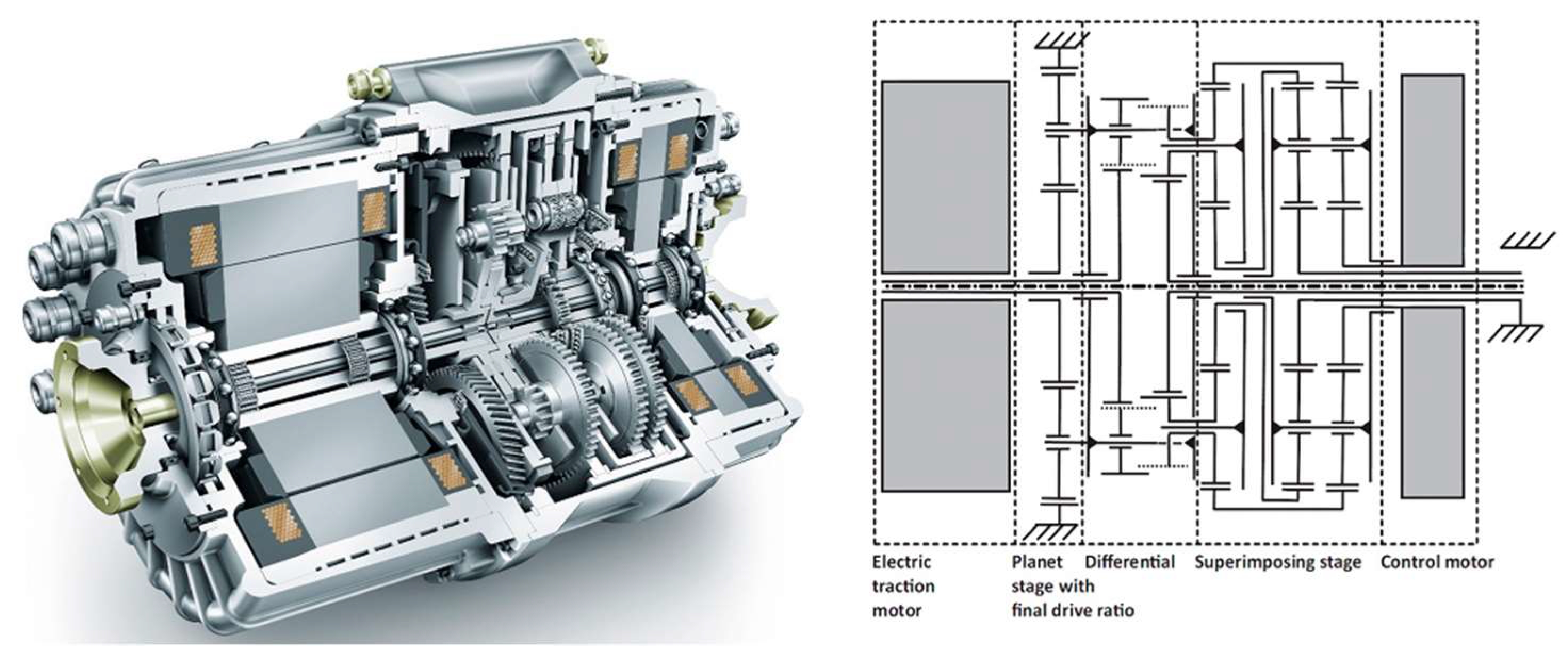

Schaeffler Planetary Gearbox with Spur-Geared Differential

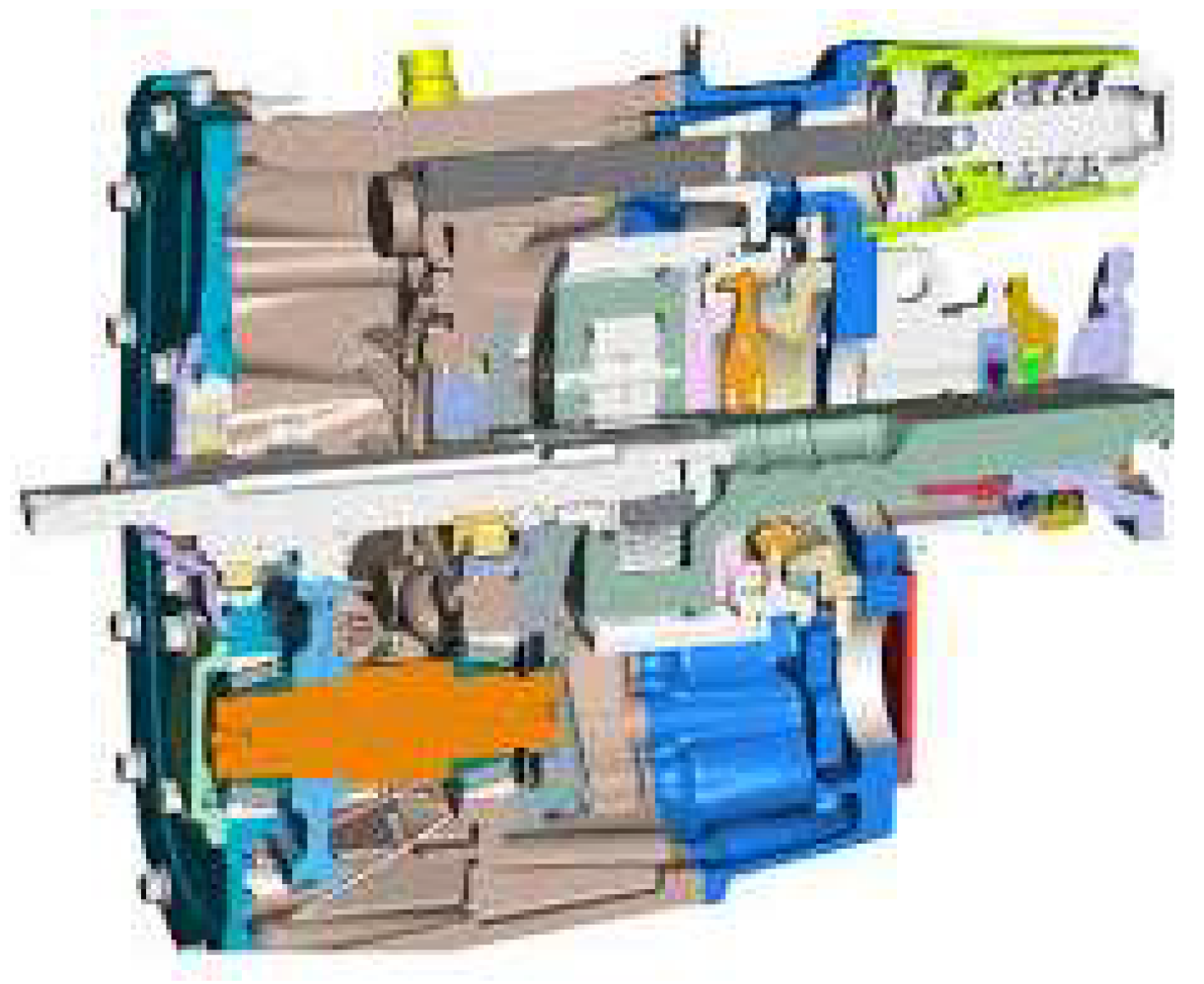

UQM Technology

4. Development Areas, Opportunities

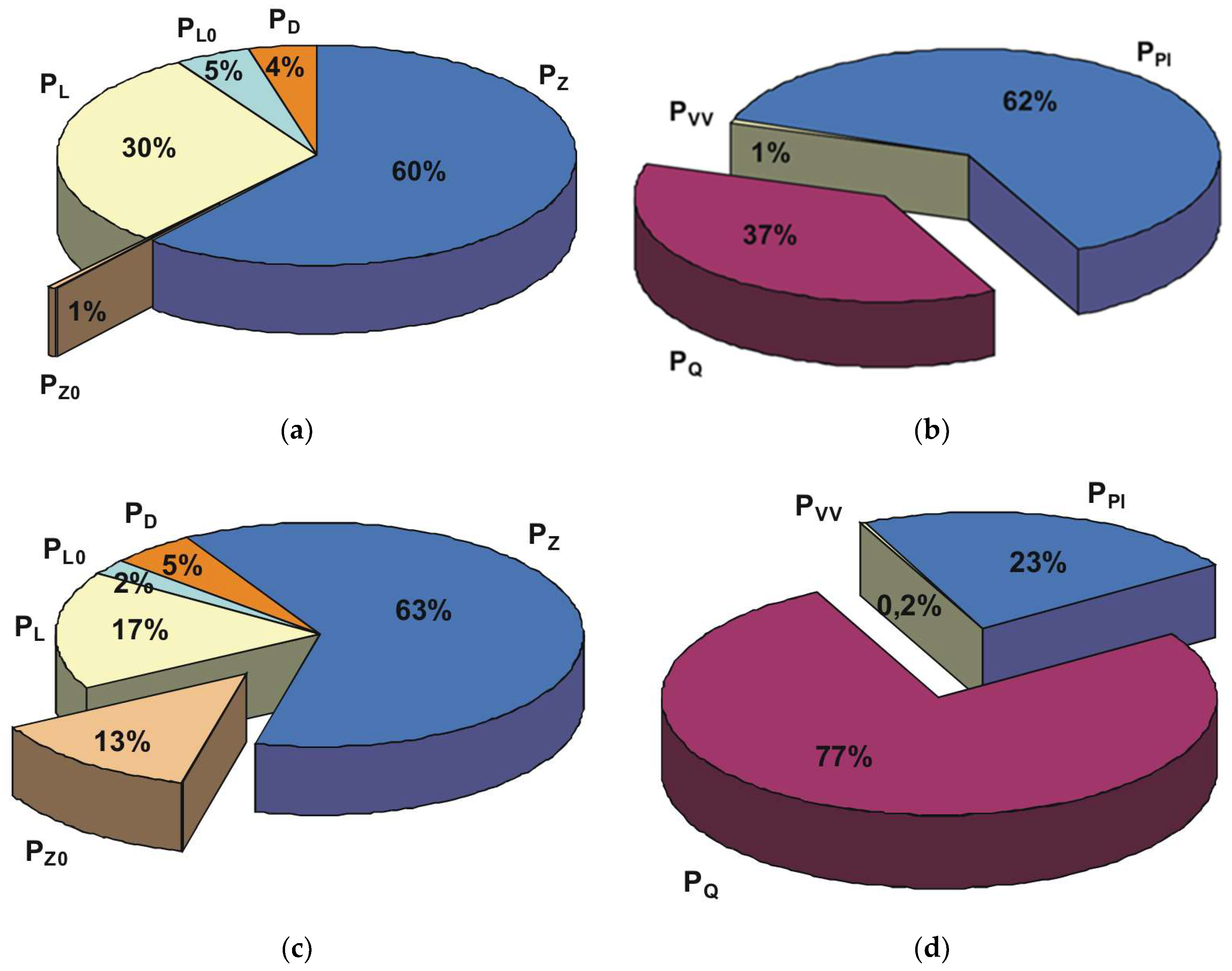

5. Power Losses of Gear Drives

Gearbox Gear Efficiency

Calculating the Bearing Friction Losses

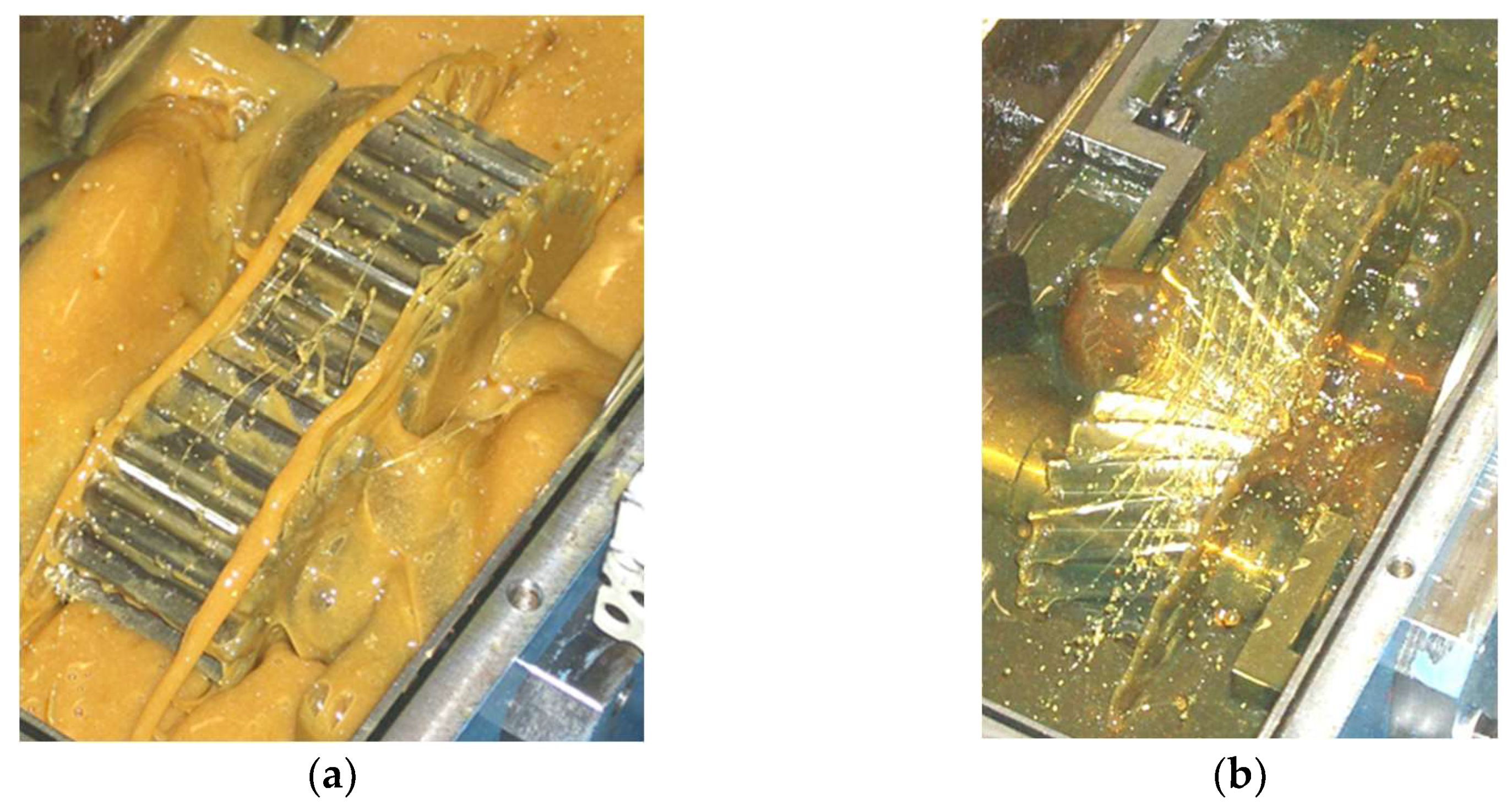

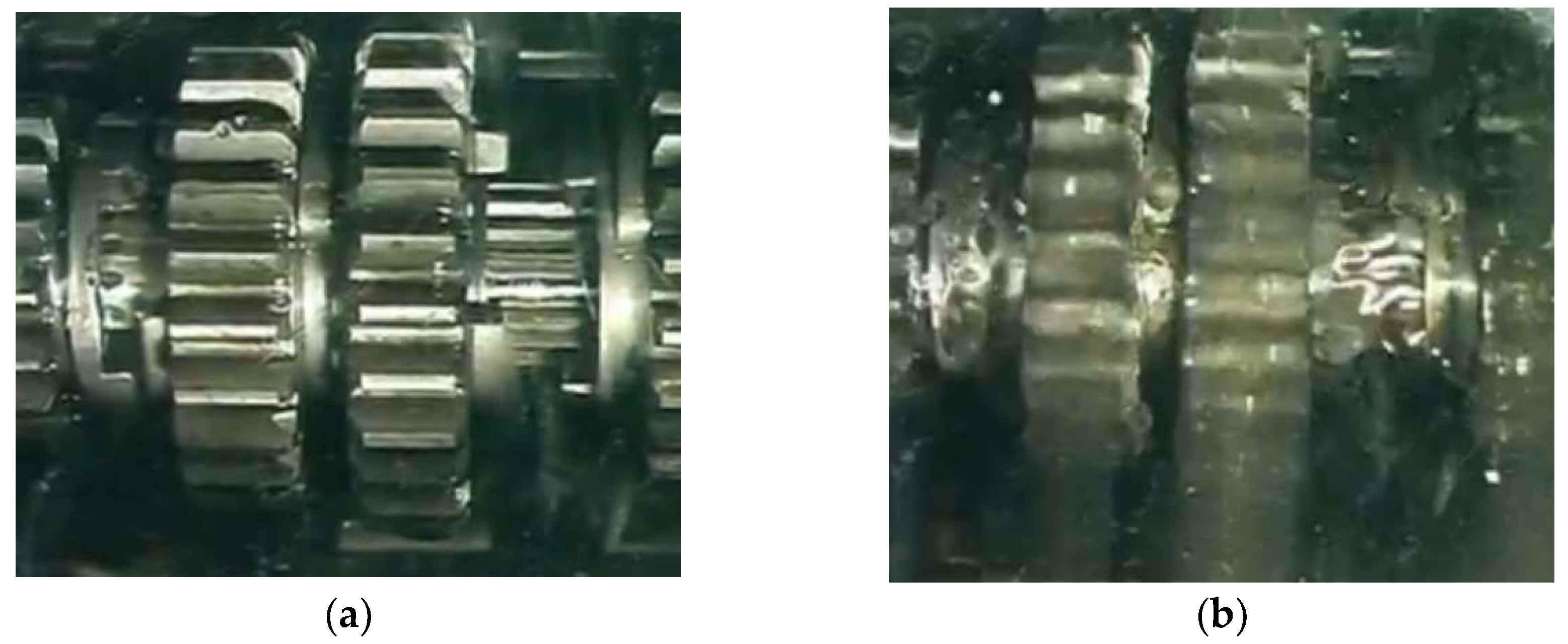

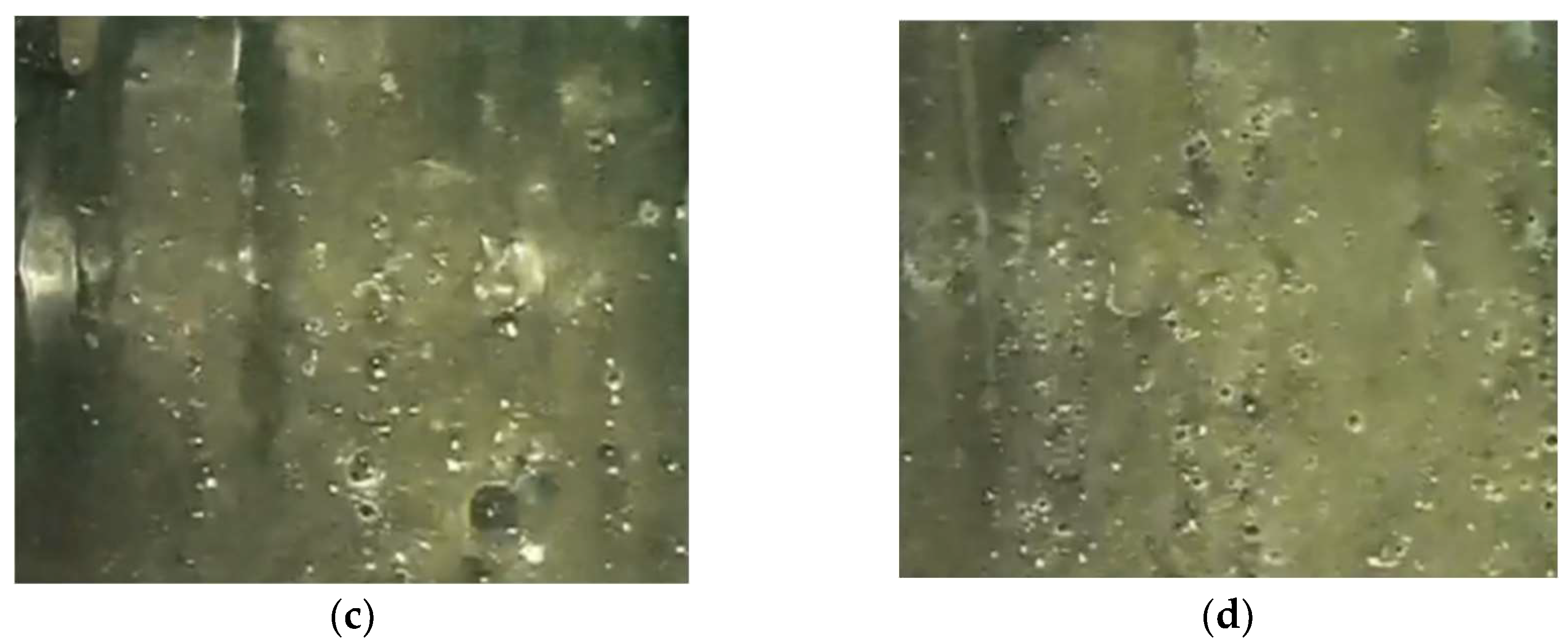

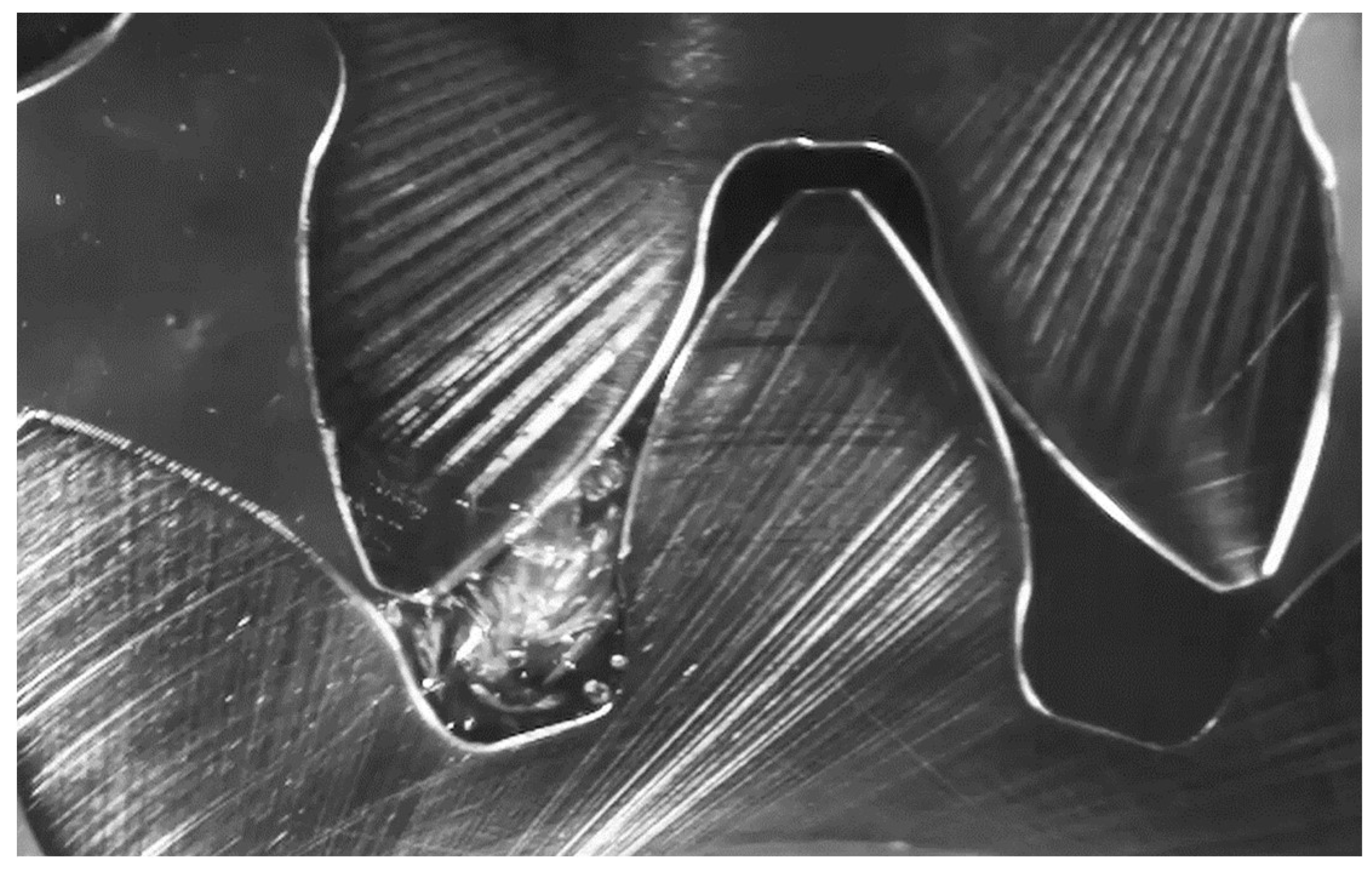

Oil Churning Losses of Gears

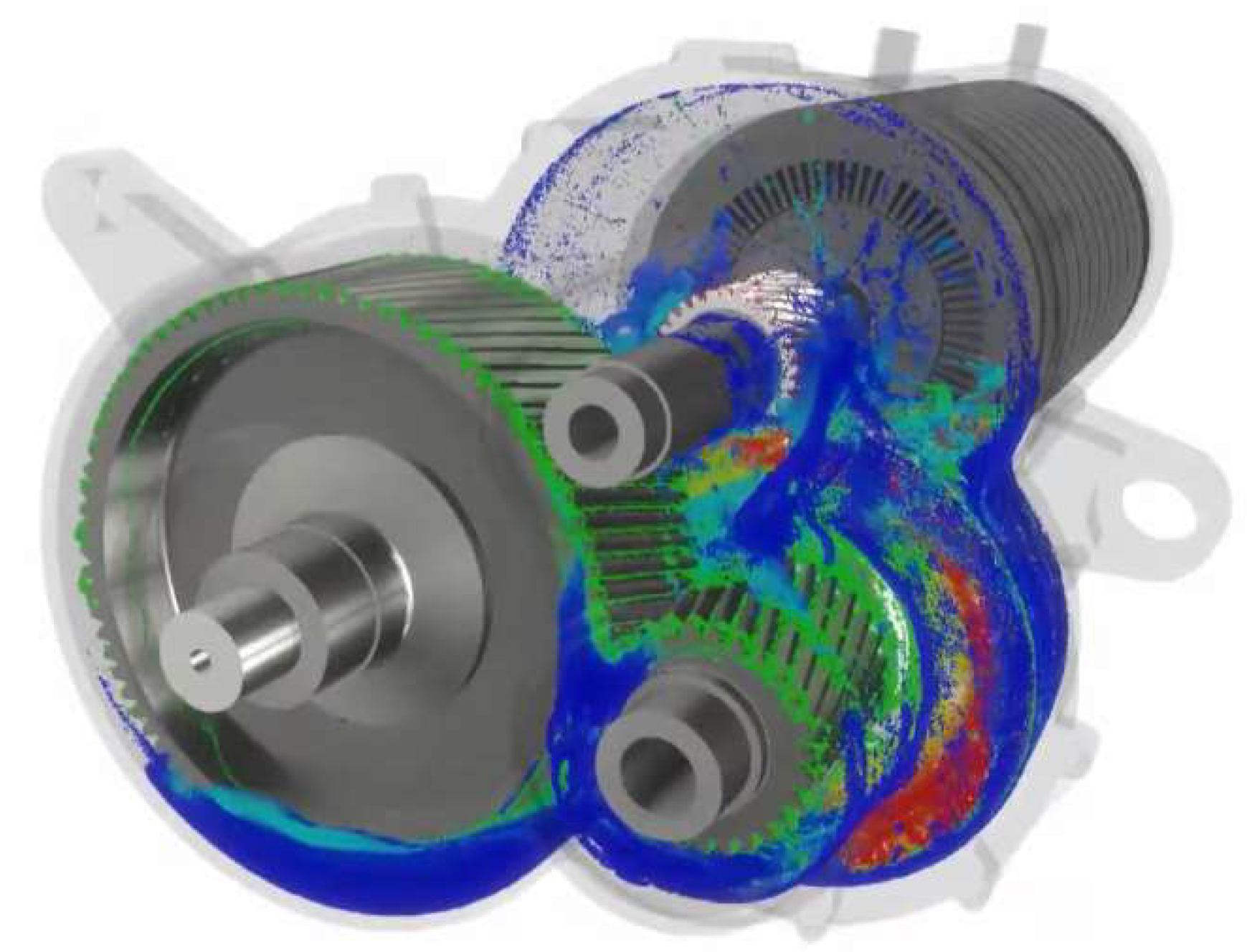

Windage Losses in Gearboxes

Seal Friction Losses

6. Summary

The Future of Electric Powertrain Designs

Appendix

- Tooth Friction Losses

- Oil Churning Losses

- Windage Losses

- Seal Friction Losses

References

- M. Pisaturo and A. Senatore, ‘Simulation of engagement control in automotive dry-clutch and temperature field analysis through finite element model’, Appl. Therm. Eng., vol. 93, pp. 958–966, Jan. 2016. [CrossRef]

- ‘Home | GKN Automotive’. . Available online: https://www.gknautomotive.com/. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- ‘AVL Home | AVL’. . Available online: https://www.avl.com/en. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- ‘Home’, Electronic Design. . Available online: https://www.electronicdesign.com/. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- ‘Ann Arbor Import Auto Repair & Service | European, Asian & Domestic Repairs’. . Available online: https://www.arbormotion.com/. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- ‘PriusChat’, PriusChat. . Available online: https://priuschat.com/forum/. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- ‘Schaeffler active eDifferential: The active differential for future drive trains: Schaeffler Symposium’, 2010. . Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Schaeffler-active-eDifferential%3A-The-active-for/bf7cb351b5f0e1f183913398111e84956f0e0b9d. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- ‘Automated manual transmissions | Fuller transmission’, Eaton. . Available online: https://www.eaton.com/us/en-us/products/transmissions.html. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- M. Vajedi and N. L. Azad, ‘Ecological Adaptive Cruise Controller for Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles Using Nonlinear Model Predictive Control’, IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst., vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 113–122, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Group, ‘Home - Mobility Engineering Technology’. . Available online: https://www.mobilityengineeringtech.com/. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- ‘Charged EVs’, Charged EVs. . Available online: https://chargedevs.com/. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- ‘openPR.com - Worldwide Open Public Relations - Publish Press Releases Free of Charge’. . Available online: https://www.openpr.com/. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Csobán, ‘Bolygóművek hő-teherbírásának meghatározása, Ph.D. doktori értekezés’, Budapest: Budapesti Műszaki és Gazdaság-tudományi Egyetem, 2011.

- ‘BPW eTransport electric drive axle’, Mynewsdesk. . Available online: https://newsroom-en.bpw.de/images/bpw-etransport-electric-drive-axle-1429834. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- ‘ZF AVE 130’. . Available online: https://press.zf.com/press/en/media/media_1506.html. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Y. N. Drozdov and Y. A. Gavrikov, ‘Friction and scoring under the conditions of Simultaneous rolling and sliding of bodies’, Wear, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 291–302, Apr. 1968. [CrossRef]

- D. Strasser, ‘Einfluss des Zahnflanken- und Zahnkopfspieles auf die Leerlaufverlustleistung von Zahnradgetrieben’, Ruhr-Universität Bochum: Fakultät für Maschinenbau, 2005.

- Z. Terplán, F. Z. Terplán, F. Apró, and Á. Döbröczöni, Fogaskerék-bolygóművek. Budapest: Műszaki Könyvkiadó, 1979.

- G. Niemann and H. Winter, Maschinenelemente, vol. 1–3. Springer Verlag, 1989. Accessed: Dec. 17, 2024. Available online: https://www.springer.com/series/0421.

- M. Duda, ‘Der geometrische Verlustbeiwert und die Verlustunsymmetrie bei geradverzahnten Stirnradgetrieben’. Forschung im Ingenieurwesen 37 VDI-Verlag, 1971.

- H. Klein, Bolygókerék hajtóművek. Budapest: Műszaki Könyvkiadó, 1968.

- J. P. O’Donoghue and A. Cameron, ‘Friction and Temperature in Rolling Sliding Contacts’, E Trans., vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 186–194, Jan. 1966. [CrossRef]

- Y. A. Misharin, ‘Influence of The Friction Condition on The Magnitude of The Friction Coefficient in The Case of Rollers with Sliding’, Proc Int Conf Gearing, pp. 159–164, 1958.

- ‘ISO/TR 13989-1:2000(en), Calculation of scuffing load capacity of cylindrical, bevel and hypoid gears — Part 1: Flash temperature method’. Accessed: Dec. 17, 2024. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/es/#iso:std:iso:tr:13989:-1:ed-1:v1:en.

- G. H. Benedict and B. W. Kelly, ‘Instanteous Coefficients of Gear Tooth Friction’, in Transactions of ASLE, 1960, pp. 55–70.

- H. Xu, ‘Development of a generalized mechanical efficiency prediction methodology for gear pairs’, The Ohio State University, 2005. Accessed: Dec. 17, 2024. Available online: https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odb_etd/etd/r/1501/10?clear=10&p10_accession_num=osu1128372109.

- E. Ciulli, I. E. Ciulli, I. Bartilotta, and A. Polacco, ‘A Model for Scuffing Prediction’, Journal of Mechanical Engineering. Accessed: Dec. 17, 2024. Available online: https://www.sv-jme.eu/article/a-model-for-scuffing-prediction/.

- F. Reuleaux, ‘Friction in Tooth Gearing’, Trans. ASME, vol. VIII, no. 9, pp. 45–85, 1886.

- K. F. Martin, ‘A review of friction predictions in gear teeth’, Wear, vol. 49, no. 2, pp. 201–238, Aug. 1978. [CrossRef]

- T. Yada, ‘Review of Gear Efficiency Equation and Force Treatment’, JSME Int. J. Ser C Dyn. Control Robot. Des. Manuf., vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 1997. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li and A. A. Seireg, ‘Predicting The Coefficient of Friction in Sliding-Rolling Contacts’, Tribol. Conf., no. K18.

- C. Naruse, S. C. Naruse, S. Haizuka, R. Nemoto, and H. Takahashi, ‘Influences of Tooth Profile on Frictional Loss and Scoring Strength in The Case of Spur Gears’, MPT’91 JSME Int’l Conf. Motion Power Transm. Hiroshima Jpn., 1991.

- H. Mizutani and Y. Isikawa, ‘Power Loss of Long Addendum Spur Gears’, VDI Berichte, vol. 1230, pp. 83–95, 1996.

- T. Yada, ‘The Measurement of Gear Mesh Friction Losses’, ASME 72-PTG-35, Oct. 1972.

- C. Changenet and M. Pasquier, ‘Power Losses and Heat Exchange in Reduction Gears: Numerical and Experimental Results’, VDI Berichte, vol. 1665, pp. 603–613, 2022.

- K. Ikejo and K. Nagamura, ‘Power Loss of Spur Gear Drive Lubricated with Traction Oil’, presented at the DETC’03/PTG, Chicago, Illinois, 2003.

- F. Hirano and T. Ueno, ‘EFFECT OF ANGLE BETWEEN DIRECTION OF SLIDING+ LINE OF CONTACT ON FRICTION+ WEAR OF ROLLER’, Lubr. Eng., vol. 20, no. 2, p. 57, 1964.

- C. M. Denny, ‘Mesh Friction in Gearing’, AGMA Fall Tech. Meet., vol. 98FTM2, 1998.

- J. I. Pedrero, ‘Determination of The Efficiency of Cylindrical Gear Sets’, 4th World Congr. Gearing Power Transm. Paris Fr., Mar. 1999.

- Y. Michlin and V. Myunster, ‘Determination of power losses in gear transmissions with rolling and sliding friction incorporated’, Mech. Mach. Theory, vol. 37, no. 2, pp. 167–174, Feb. 2002. [CrossRef]

- N. E. Anderson and S. H. Loewenthal, ‘Efficiency of Nonstandard and High Contact Ratio Involute Spur Gears’, J. Mech. Transm. Autom. Des., vol. 108, no. 1, pp. 119–126, Mar. 1986. [CrossRef]

- N. E. Anderson and S. H. Loewenthal, ‘Design of Spur Gears for Improved Efficiency’, J. Mech. Des., vol. 104, no. 4, pp. 767–774, Oct. 1982. [CrossRef]

- N. E. Anderson and S. H. Loewenthal, ‘Effect of Geometry and Operating Conditions on Spur Gear System Power Loss’, J. Mech. Des., vol. 103, no. 1, pp. 151–159, Jan. 1981. [CrossRef]

- J. P. Barnes, ‘Non-Dimensional Characterization of Gear Geometry, Mesh Loss and Windage’, 97FTM11, 1997.

- M. Vaishya and D. R. Houser, ‘Modeling and Measurement of Sliding Friction for Gear Analysis’, 99FTMS1, Oct. 1999.

- D. Dowson and G. R. Higginson, ‘A theory of involute gear lubrication’, Proceeding Symp. Organ. Mech. Tests Lubr. Panel Inst. Inst. Pet. Gear Lubr., vol. 182, no. 1, pp. 8–15.

- K. F. Martin, ‘The Efficiency of Involute Spur Gears’, J. Mech. Des., vol. 103, no. 1, pp. 160–169, Jan. 1981. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, H. Y. Wang, H. Li, J. Tong, and J. Jang, ‘Transient thermoelastohydrodynamic lubrication analysis of an involute spur gear | Request PDF’, ResearchGate, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Wu and H. S. Cheng, ‘A Friction Model of Partial-EHL Contacts and its Application to Power Loss in Spur Gears’, ResearchGate, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. H. Dawson, ‘High-speed Gear Windage’, GEC Rev., vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 164–167, 1988.

- P. Luke and A. V. Olver, ‘A study of churning losses in dip-lubricated spur gears’, Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G J. Aerosp. Eng., vol. 213, no. 5, pp. 337–346, May 1999. [CrossRef]

- Y. Diab, F. Y. Diab, F. Ville, P. Velex, and C. Changenet, ‘Windage Losses in High Speed Gears—Preliminary Experimental and Theoretical Results’, J. Mech. Des., vol. 126, no. 5, pp. 903–908, Oct. 2004. [CrossRef]

- D. Dowson and G. R. Higginson, Elasto-hydrodynamic lubrication | WorldCat.org. Pergamon Press, Oxfort, 1977. Accessed: Dec. 17, 2024. Available online: https://search.worldcat.org/title/569568722.

- S. Ali, ‘DUDLEY's HANDBOOK OF PRACTICAL GEAR DESIGN and MANUFACTURE’, Accessed: Dec. 17, 2024. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/45138343/DUDLEYs_HANDBOOK_OF_PRACTICAL_GEAR_DESIGN_and_MANUFACTURE.

- P. Heingartner and D. Mba, ‘Determining Power Losses in The Helical Gear Mesh; Case Study, Chicago, Illinois, 2003’, presented at the DETC’3, Chicago, Illinois, 2003.

- R. Stribeck, Kugellager für beliebige Belastungen. Springer, 1901.

- Palmgren, Neue Untersuchungen über Energieverluste in Wälzlagern | WorldCat.org. SKF Kugellagerfabriken, Schweinfurt, 1975. Accessed: Dec. 17, 2024. Available online: https://search.worldcat.org/title/313978755.

- T. Bartels, ‘Instationäres Gleitwälzkontaktmodell zur Simulation der Reibung und Kinematik von Rollenlagern’, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 1997.

- T. Bartels, ‘Bordreibung von Zylinderrollenlagern’, in Antrienbtechnik, vol. 420, 1994.

- P. Eschmann, ‘Einleitung’, in Das Leistungsvermögen der Wälzlager: Eine Beurteilung nach neuen Gesichtspunkten, P. Eschmann, Ed., Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 1964, pp. 1–3. [CrossRef]

- P. K. Gupta, Advanced Dynamics of Rolling Elements. New York, NY: Springer, 1984. [CrossRef]

- G. Hansberg, ‘Fresstragfähigkeit vollrolliger Planetenrad-Wälzlager’, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 1991.

- J. Hollatz, ‘Start– und Reibungsverhalten von ölgeschmierten Wälzlagern bei Umgebungstemperaturen bis – 40 °C’, Universität Hannover, 1984.

- J. Koryciak, ‘Einfluss der Ölmenge auf das Reibmoment von Wälzlagern mit Linienberühnung’, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 2007.

- H. Korrenn, ‘The Axial Load-Carrying Capacity of Radial Cylindrical Roller Bearings’, J. Lubr. Technol., vol. 92, no. 1, pp. 129–134, Jan. 1970. [CrossRef]

- B. Liang, ‘Berechnungsgleichungen für Reibmomente in Planetenrad-Wälzlagern’, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 1992.

- Potthoff, ‘Anwendungsgrenzen vollrolliger Planetenrad-Wälzlager’, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 1986.

- B. Scherb, ‘Prediction and Measurement of Friction Torque Characteristics of Radially and Axially Loaded Readial Cylindrical Roller Bearings’, University of Glamorgan, UK, 1999.

- T. Siepmann, ‘Reibmomente in Zylinderrollenlagern für Planetenrädern’, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, 1987.

- H. Kumar and V. Gupta, ‘Effect of Surface Roughness on the Friction Moment in a Lubricated Deep Groove Ball Bearing’, Accessed: Dec. 28, 2024. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2075-4442/12/12/443.

- P. Lee, C. P. Lee, C. Sanchez, M. Moneer, and A. Velasquez, ‘Electrification of a Mini Traction Machine and Initial Test Results’, Lubricants, vol. 12, no. 10, p. 337, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ariura, ‘The Lubricant Churning Loss and its Behaviour in Gear Box in Cylindrical Gear Systems’, J. Jpn. Soc. Lubr. Eng., vol. 20, no. 3, 1975, . Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?&title=The%20lubricant%20churning%20loss%20and%20its%20behavior%20in%20gearbox%20in%20cylindical%20gear%20systems&publication_year=1975&author=Ariura%2CY&author=Ueno%2CT#d=gs_cit&t=1734713379861&u=%2Fscholar%3Fq%3Dinfo%3AkmcULDnzRXEJ%3Ascholar.google. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Y. Ariura, T. Y. Ariura, T. Ueno, T. Sunaga, and S. Sunamoto, ‘The Lubricant Churning Loss in Spur Gear Systems’, Bull. JSME, vol. 16, no. 95, pp. 881–892, 1973. [CrossRef]

- P. Walter, ‘Untersuchungen zur Tauchschmierung von Stirnrädern bei Umfangsgeschwindigkeiten bis 60 m/s’, Universität Stuttgart, 1982.

- W. Mauz, Hydraulische Verluste bei Tauch- und Einspritzschmierung von Zahnradgetrieben: Abschlußbericht ; Forschungsvorhaben Nr. 44/III ; Berichtszeitraum: 1983-1984. FVA, 1985.

- S. Terekhov, ‘Hydraulic losses in gearboxes with oil immersion’, Russ. Eng. J., vol. 55, 1975.

- S. Terekhov, ‘Basic Problems of Heat Calculation of Gear Reducers’, JSME Int. Conf. Motion Powertransmissions, 1991.

- J. Maurer, ‘Lastunabhängige Verzahnungsverluste schnellaufender Stirnradgetriebe’, in Dissertation Universität Stuttgart, Stuttgart, 1994.

- Dick, ‘Untersuchungen zu den Leerlaufverlusten eines einspritzgeschmierten Stirnradgetriebes’, in Dissertation Universität Stuttgart, 1989.

- Sax, ‘Untersuchungen zur Wirkungsweise der Tauchschmierung’, in Dissertation Universität Stuttgart, 1996.

- Schimpf, ‘Untersuchungen zur Wirkungsweise der Tauchschmierung’, in Dissertation Universität Stuttgart, 1994.

- D.-O. Leimann, ‘Wärmearm konstruieren, Teil 1: Einfluss des Zahnflankenspiels auf die Erwärmung bzw. Verlustleistung von Zahnradgetrieben’, in Antriebstechnik, vol. 3, in 32, vol. 3., 1993, pp. 70–73.

- D.-O. Leimann, ‘Einfluss der Übersetzungsaufteilung auf die Erwärmung von Zahnradgetrieben’, in Wärmearm konstruieren, vol. 5, in Antriebstechnik 32, vol. 5., 1993, pp. 85–883.

- E. Lauster, ‘Untersuchungen und Berechnungen zum Wärmehaushalt mechanischer Schaltgetriebe’, Dissertation Universität Stuttgart, 1980.

- M. Butsch, ‘Hydraulische Verluste schnelllaufender Stirnradgetriebe’, in Dissertation Universität Stuttgart, 1989.

- J. Tochtermann, ‘Development of an integrated axle for MD trucks for urban distribution traffic’, presented at the 16th International CTI Symposium Automotive Transmissions, HEV and EV Drives, Berlin, 2017.

- ‘Edison Motors’, Edison Motors. . Available online: https://www.edisonmotors.ca. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- kmx888, Royal Enfield UCE Gearbox Lubrication, (Sep. 01, 2009). Accessed: Dec. 28, 2024. [Online Video]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2V_rP88YEP0.

- FPRG, External Gear Pump - Cavitation, (Apr. 27, 2017). Accessed: Dec. 28, 2024. [Online Video]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a_o0v9mPkhU.

- TECHNIA Simulation, SIMULIA XFlow: Simulation of gearbox Lubrication, (May 22, 2019). Accessed: Dec. 28, 2024. [Online Video]. Available: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=irb2V2-JO2w.

- ‘Automotive News | Car News | AutoNews.com’. . Available online: https://www.autonews.com/. (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- M. Silvestri, ‘A Theoretical Study of Viscoelastohydrodinamic Lubrication (VEHL) in Elastomeric Lip Seals’, presented at the ECOTRIB 2009, Pisa, Italy, 2009.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).