Submitted:

29 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

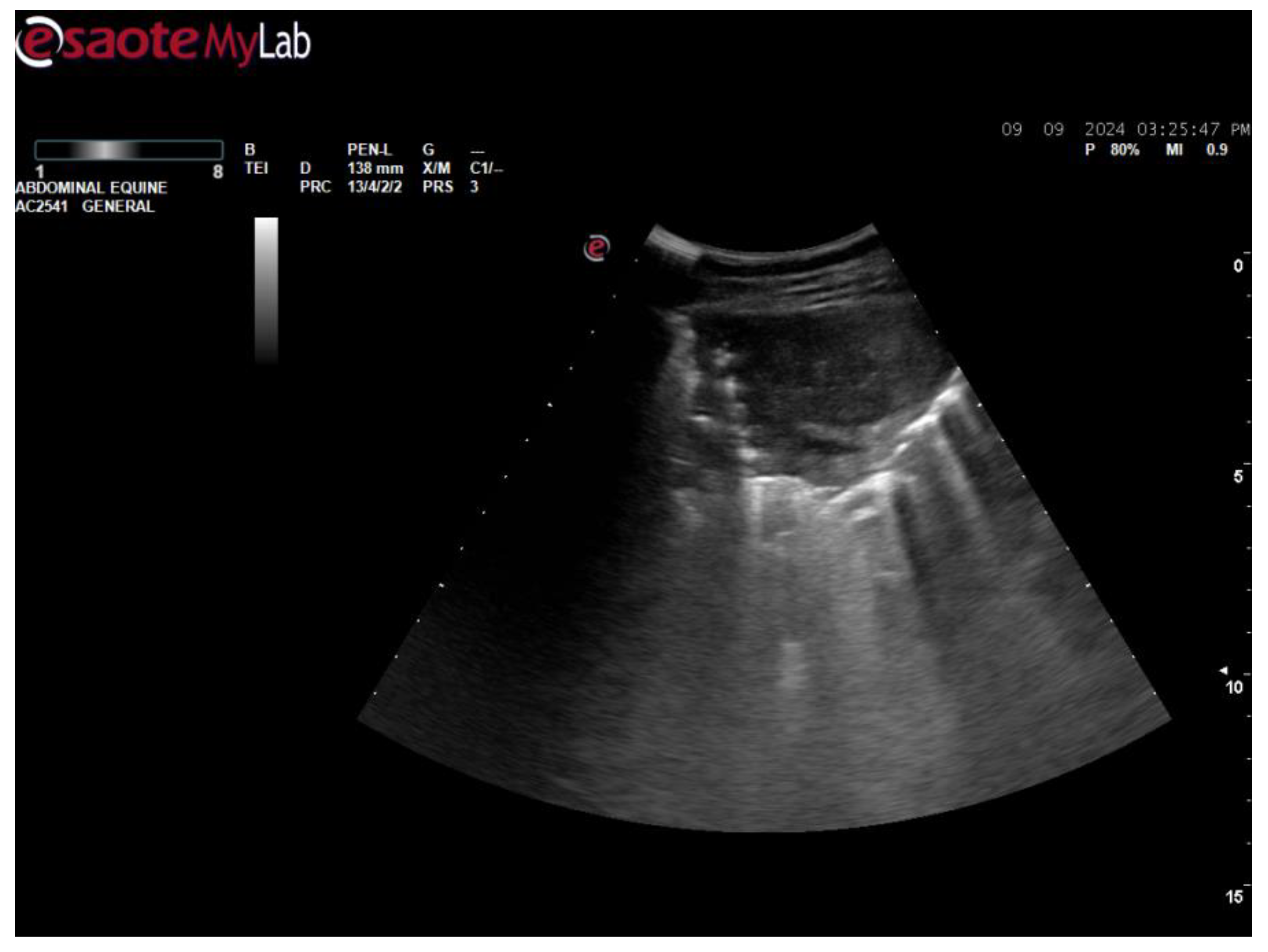

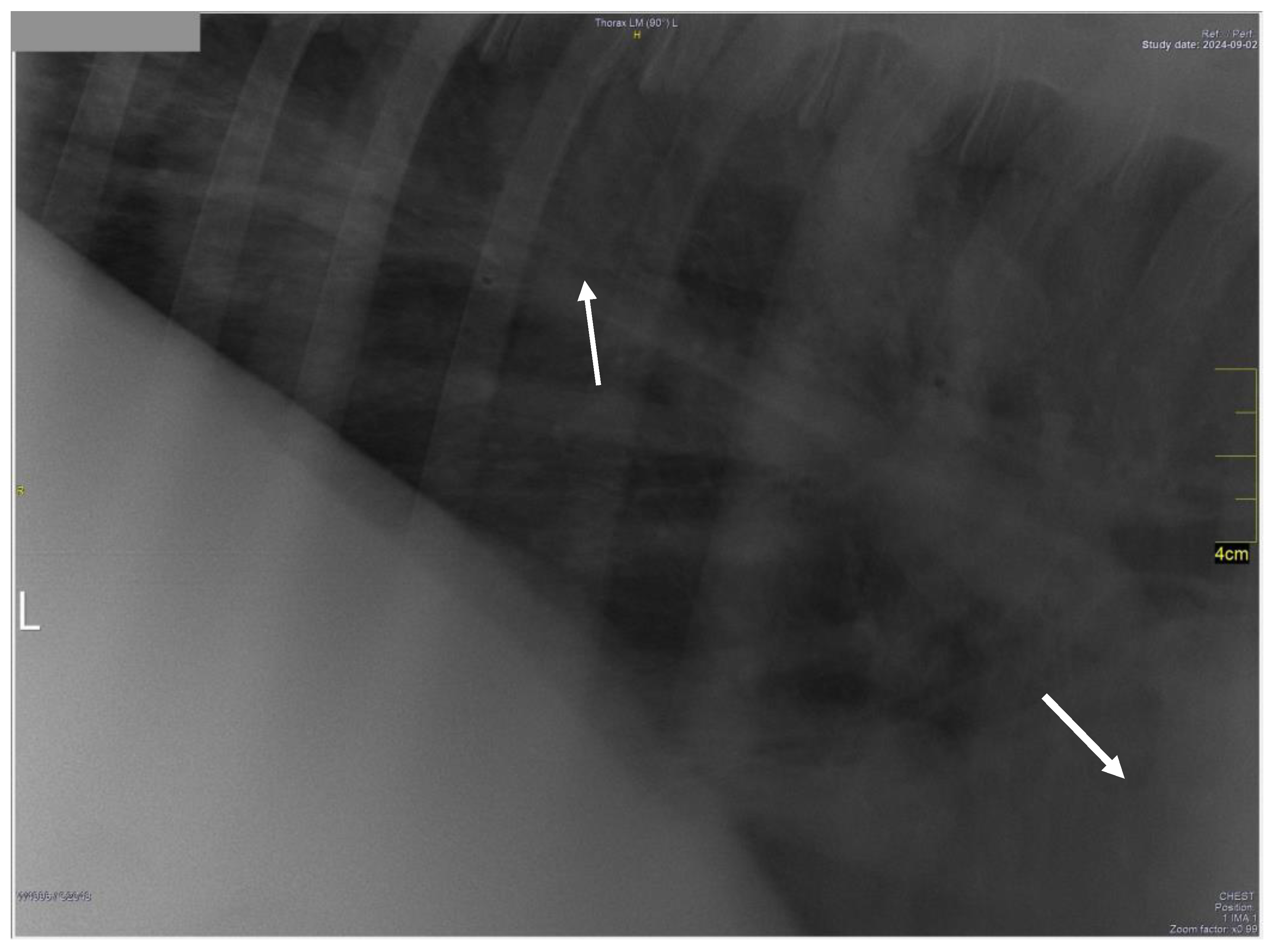

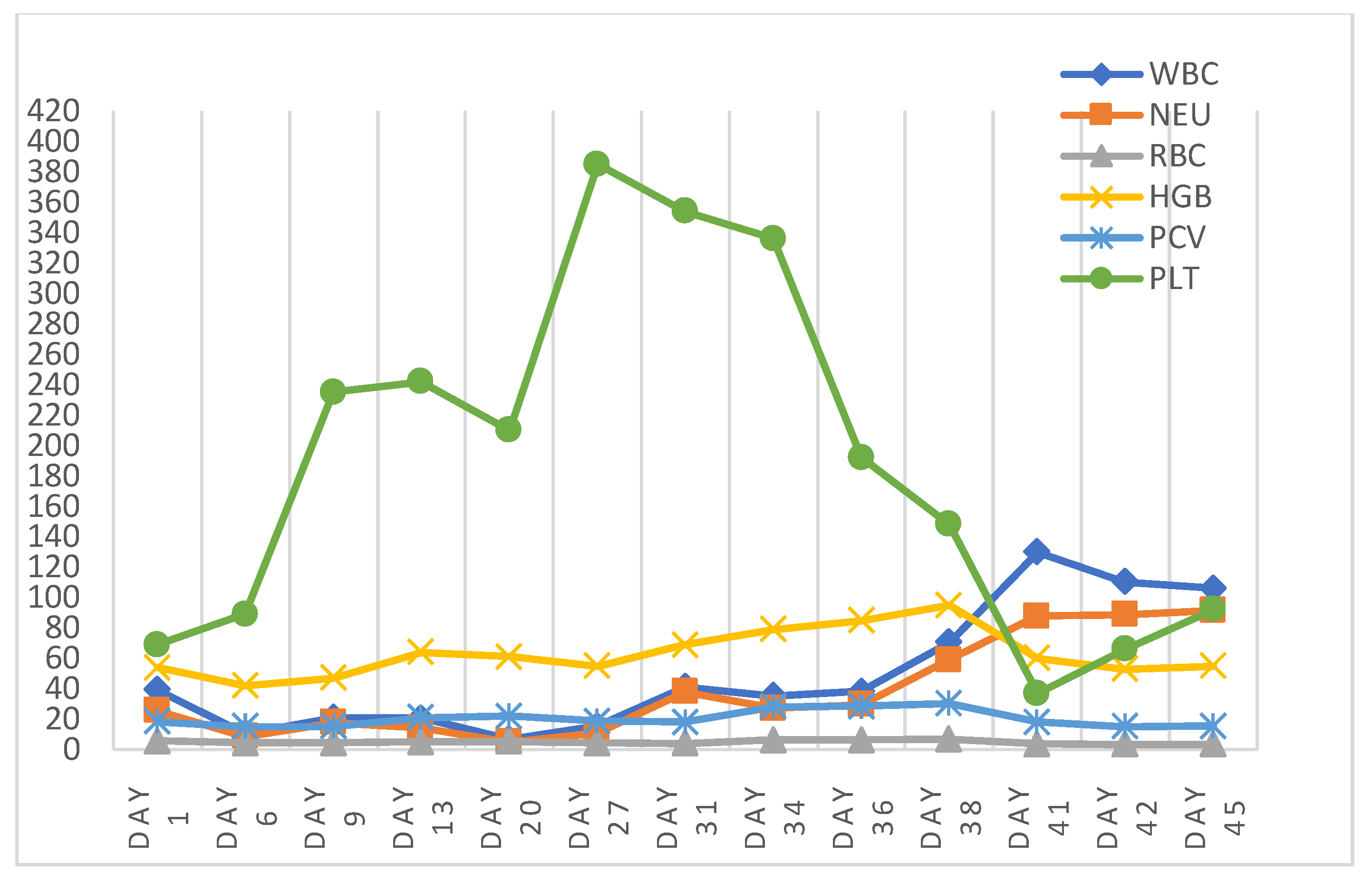

2. Case History

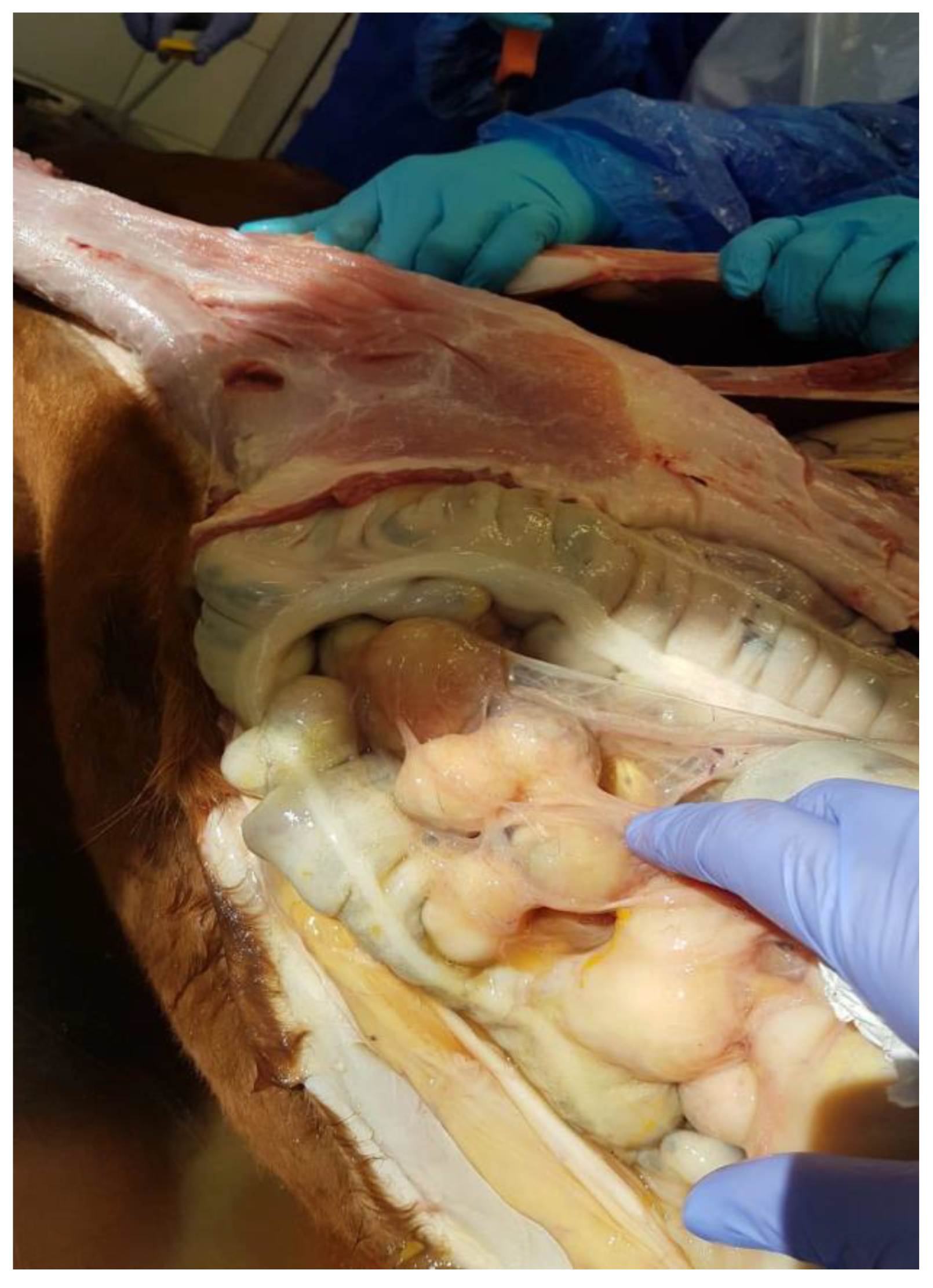

3. Post-Mortem Examination

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Petra Agthe, Abby R. Caine, Barbara Posch, and Michael E. Herrtage. 2009. ULTRASONOGRAPHIC APPEARANCE OF JEJUNAL LYMPH NODES IN DOGS WITHOUT CLINICAL SIGNS OF GASTROINTESTINAL DISEASE. Vet Radiology Ultrasound 50, 2 (March 2009), 195–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8261.2009.01516.x. [CrossRef]

- Felix Amereller, Christian Lottspeich, Grete Buchholz, and Karl Dichtl. 2020. A horse and a zebra: an atypical clinical picture including Guillain-Barré syndrome, recurrent fever and mesenteric lymphadenopathy caused by two concomitant infections. Infection 48, 3 (June 2020), 471–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-020-01397-5. [CrossRef]

- Betsy Vaughan, DVM*; Mary Beth Whitcomb, DVM, MBA, ECVDI (LA Assoc); and Nicola Pusterla, DVM, PhD, Diplomate ACVIM. 2013. Ultrasonographic Findings in 42 Horses With Cecal Lymphadenopathy. Vol. 59, AAEP PROCEEDINGS (2013), 238. Retrieved from https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.5555/20143210449.

- D. E. Brown, D. J. Meyer, W. E. Wingfield, and R. M. Walton. 1994. Echinocytosis Associated with Rattlesnake Envenomation in Dogs. Vet Pathol 31, 6 (November 1994), 654–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/030098589403100604. [CrossRef]

- Nicholas B. Burley, Paul S. Dy, Suraj Hande, Shreyas Kalantri, Chirayu Mohindroo, and Kenneth Miller. 2021. Autoimmune Hemolytic Anemia as Presenting Symptom of Hodgkin Lymphoma. Case Rep Hematol 2021, (2021), 5580823. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/5580823. [CrossRef]

- H. J. Cottle and K. J. Hughes. 2010. Haemolytic anaemia in a pony associated with a perivascular abscess caused by Clostridium perfringens. Equine Veterinary Education 22, 1 (January 2010), 13–19. https://doi.org/10.2746/095777309X474. [CrossRef]

- T. J. Divers, L. W. George, and J. W. George. 1982. Hemolytic anemia in horses after the ingestion of red maple leaves. J Am Vet Med Assoc 180, 3 (February 1982), 300–302.

- Erdal Erol, Carrie L. Shaffer, and Brian V. Lubbers. 2022. Synergistic combinations of clarithromycin with doxycycline or minocycline reduce the emergence of antimicrobial resistance in Rhodococcus equi. Equine Veterinary Journal 54, 4 (July 2022), 799–806. https://doi.org/10.1111/evj.13508. [CrossRef]

- S. Giguère, N.D. Cohen, M. Keith Chaffin, N.M. Slovis, M.K. Hondalus, S.A. Hines, and J.F. Prescott. 2011. Diagnosis, Treatment, Control, and Prevention of Infections Caused by R hodococcus equi in Foals. Veterinary Internal Medicne 25, 6 (November 2011), 1209–1220. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00835.x. [CrossRef]

- Steeve Giguère and Gregory D. Roberts. 2012. ASSOCIATION BETWEEN RADIOGRAPHIC PATTERN AND OUTCOME IN FOALS WITH PNEUMONIA CAUSED BY R hodococcus equi. Vet Radiology Ultrasound 53, 6 (November 2012), 601–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8261.2012.01964.x. [CrossRef]

- Courtney Higgins and Laura Huber. 2023. Rhodococcus Equi: Challenges to Treat Infections and to Mitigate Antimicrobial Resistance. Journal of Equine Veterinary Science 127, (August 2023), 104845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2023.104845. [CrossRef]

- Anna Hollis and Kevin Corley. 2007. Practical guide to fluid therapy in neonatal foals. In Practice 29, 3 (March 2007), 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1136/inpract.29.3.130. [CrossRef]

- Samuel D. Hurcombe, Margaret C. Mudge, and Kenneth W. Hinchcliff. 2007. Clinical and clinicopathologic variables in adult horses receiving blood transfusions: 31 cases (1999–2005). javma 231, 2 (July 2007), 267–274. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.231.2.267. [CrossRef]

- Rabyia Javed, A. K. Taku, R. K. Sharma, and Gulzaar Ahmed Badroo. 2017. Molecular characterization of Rhodococcus equi isolates in equines. Vet World 10, 1 (January 2017), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2017.6-10. [CrossRef]

- Imogen C. Johns, Anne Desrochers, Kathryn L. Wotman, and Raymond W. Sweeney. 2011. Presumed immune-mediated hemolytic anemia in two foals with Rhodococcus equi infection. J Vet Emergen Crit Care 21, 3 (June 2011), 273–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-4431.2011.00633.x. [CrossRef]

- F. A. Kallfelz, R. H. Whitlock, and R. D. Schultz. 1978. Survival of 59Fe-labeled erythrocytes in cross-transfused equine blood. Am J Vet Res 39, 4 (April 1978), 617–620.

- Anazoeze Jude Madu and Maduka Donatus Ughasoro. 2017. Anaemia of Chronic Disease: An In-Depth Review. Med Princ Pract 26, 1 (2017), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000452104. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Mair, F. G. Taylor, and M. H. Hillyer. 1990. Autoimmune haemolytic anaemia in eight horses. Vet Rec 126, 3 (January 1990), 51–53.

- Monique N. Mayer, Joshua A. Lawson, and Tawni I. Silver. 2010. SONOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF PRESUMPTIVELY NORMAL CANINE MEDIAL ILIAC AND SUPERFICIAL INGUINAL LYMPH NODES: Sonographic Features of Normal Lymph Nodes. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 51, 6 (November 2010), 638–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8261.2010.01710.x. [CrossRef]

- Sheila McCullough. 2003. Immune-mediated hemolytic anemia: understanding the nemesis. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice 33, 6 (November 2003), 1295–1315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2003.08.003. [CrossRef]

- Sandra J. Nance, Stephan Ladisch, Timothy L. Williamson, and George Garratty. 1988. Erythromycin-Induced Immune Hemolytic Anemia. Vox Sanguinis 55, 4 (November 1988), 233–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1423-0410.1988.tb04703.x. [CrossRef]

- Jed A. Overmann, Leslie C. Sharkey, Doug J. Weiss, and Dori L. Borjesson. 2007. Performance of 2 microtiter canine Coombs’ tests. Veterinary Clinical Pathol 36, 2 (June 2007), 179–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-165X.2007.tb00205.x. [CrossRef]

- M. Pate, T. Pirš, I. Zdovc, B. Krt, and M. Ocepek. 2004. Haemolytic Rhodococcus equi Isolated from a Swine Lymph Node with Granulomatous Lesions. Journal of Veterinary Medicine, Series B 51, 5 (June 2004), 249–250. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00758.x. [CrossRef]

- S. F. Peek. 2010. Immune-mediated haemolytic anaemia in adult horses: Do we need to transfuse, immunosuppress or just treat the primary problem? Equine Veterinary Education 22, 1 (January 2010), 20–22. https://doi.org/10.2746/095777309X475. [CrossRef]

- A. Pereira, C. Sanz, F. Cervantes, and R. Castillo. 1991. Immune hemolytic anemia and renal failure associated with rifampicin-dependent antibodies with anti-I specificity. Ann Hematol 63, 1 (July 1991), 56–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01714964. [CrossRef]

- J F Prescott. 1991. Rhodococcus equi: an animal and human pathogen. Clin Microbiol Rev 4, 1 (January 1991), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.4.1.20. [CrossRef]

- Charles R. Pugh. 1994. ULTRASONOGRAPHIC EXAMINATION OF ABDOMINAL LYMPH NODES IN THE DOG. Vet Radiology Ultrasound 35, 2 (March 1994), 110–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8261.1994.tb00197.x. [CrossRef]

- Alicja Rakowska, Agnieszka Marciniak-Karcz, Andrzej Bereznowski, Anna Cywińska, Monika Żychska, and Lucjan Witkowski. 2022. Less Typical Courses of Rhodococcus equi Infections in Foals. Veterinary Sciences 9, 11 (October 2022), 605. https://doi.org/10.3390/vetsci9110605. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Reuss. 2022. Rhodococcus equi , extrapulmonary disorders and lack of response to therapy. Equine Veterinary Education 34, 8 (August 2022), 399–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/eve.13583. [CrossRef]

- S. Schmaldienst and W. H. Horl. 1996. Bacterial infections during immunosuppression - immunosuppressive agents interfere not only with immune response, but also with polymorphonuclear cell function. Nephrol Dial Transplant 11, 7 (July 1996), 1243–1245.

- Elke Schreurs, Kathelijn Vermote, Virginie Barberet, Sylvie Daminet, Heike Rudorf, and Jimmy H. Saunders. 2008. ULTRASONOGRAPHIC ANATOMY OF ABDOMINAL LYMPH NODES IN THE NORMAL CAT. Vet Radiology Ultrasound 49, 1 (January 2008), 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8261.2007.00320.x. [CrossRef]

- Debra C. Sellon. 2004. Disorders of the Hematopoietic System. In Equine Internal Medicine. Elsevier, 721–768. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-72-169777-1/50014-7. [CrossRef]

- E. Sigler, A. Miskin, M. Shtlarid, and A. Berrebi. 1998. Fever of unknown origin and anemia with Rhodococcus equi infection in an immunocompetent patient. Am J Med 104, 5 (May 1998), 510.

- Joseph E. Smith, Molly Dever, Jana Smith, and Richard M. DeBowes. 1992. Post-Transfusion Survival of50 Cr-Labeled Erythrocytes in Neonatal Foals. Veterinary Internal Medicne 6, 3 (May 1992), 183–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1676.1992.tb00334.x. [CrossRef]

- H J Steinkamp, M Mueffelmann, J C Böck, T Thiel, P Kenzel, and R Felix. 1998. Differential diagnosis of lymph node lesions: a semiquantitative approach with colour Doppler ultrasound. The British Journal of Radiology 71, 848 (August 1998), 828–833. https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.71.848.9828794. [CrossRef]

- Brett Tennent-Brown. 2011. Plasma Therapy in Foals and Adult Horses. (2011).

- Helen L Thomas and Michael A Livesey. 1998. Immune-mediated hemolytic anemia associated with trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole administration in a horse. 39, (1998).

- K. Jane Wardrop. 2005. The Coombs’ test in veterinary medicine: past, present, future. Veterinary Clinical Pathol 34, 4 (December 2005), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-165X.2005.tb00057.x. [CrossRef]

- Maria Wetzig, Monica Venner, and Steeve Giguère. 2020. Efficacy of the combination of doxycycline and azithromycin for the treatment of foals with mild to moderate bronchopneumonia. Equine Veterinary Journal 52, 4 (July 2020), 613–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/evj.13211. [CrossRef]

- Melinda J. Wilkerson, Elizabeth Davis, Wilma Shuman, Kenneth Harkin, Judy Cox, and Bonnie Rush. 2000. Isotype-Specific Antibodies in Horses and Dogs with Immune-Mediated Hemolytic Anemia. J Vet Int Med 14, 2 (2000), 190. https://doi.org/10.1892/0891-6640(2000)014<0190:IAIHAD>2.3.CO;2. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).