1. Introduction

Hospital-acquired infections (HAIs), also known as healthcare-associated infections, refer to infections that are neither present nor incubating at the time of hospital admission but manifest 48 hours or more after hospitalization [

1]. These infections include those that affect healthcare workers and infections detected post-discharge if they are linked to the healthcare environment [

2,

3]. Major organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), through the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN), actively monitor and guide the prevention of HAIs to enhance patient safety and improve healthcare outcomes [

4].

The most common HAIs are central line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs), surgical site infections (SSIs), ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP), and skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs). The causative agents of these infections include multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacteria, viruses, and fungi [

1,

2]. Globally, approximately 5%-10% of hospitalized patients develop HAIs. In high-income countries, prevalence rates range from 4.5% in the United States to 7.5% in Europe, while low- and middle-income countries report significantly higher rates, ranging from 5.7% to 19.2% [

2].

Several factors contribute to the occurrence of HAIs, including inappropriate use of antimicrobials, suboptimal hospital hygiene, and inadequate adherence to infection prevention protocols among healthcare workers and patients [

5]. The risk factors are particularly pronounced in intensive care units (ICUs) due to the severity of illnesses, frequent use of invasive devices, and prolonged hospital stays. These include immunosuppression, advanced age, comorbidities, mechanical ventilation, recent invasive procedures, and prior use of intravenous antibiotics [

6,

7].

Despite advancements in healthcare and technology, HAIs remain a global challenge, causing significant morbidity and mortality, extended hospital stays, and increased healthcare costs [

8,

9]. Moreover, HAIs facilitate the selection and spread of MDR pathogens, further complicating treatment and containment [

9]. Recent studies have highlighted the burden of HAIs in resource-limited settings, where surveillance and control measures are often inadequate. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, the prevalence of HAIs in ICUs ranges from 15% to 40%, with

Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, and

Staphylococcus aureus being common pathogens [

10].

Effective prevention and control strategies for HAIs emphasize adherence to infection prevention guidelines, proper hand hygiene, and the judicious use of antimicrobials. Organizations such as the CDC and WHO have provided comprehensive protocols aimed at reducing HAI prevalence, including surveillance systems and the implementation of evidence-based practices [

11,

12]. However, in many regions, including South Africa, there is limited data on the prevalence and types of HAIs, particularly in ICUs.

This study aims to determine the prevalence and types of HAIs among patients admitted to the ICU at Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital (NMAH) in Mthatha, Eastern Cape, South Africa. The findings will contribute to the growing body of evidence needed to inform targeted interventions for HAI prevention and control in similar settings.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This retrospective cross-sectional study analyzed hospital records of patients admitted to the ICU for various medical conditions between January 2020 and December 2022 at Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital (NMAH) in Mthatha, Eastern Cape, South Africa. The NMAH is a central academic hospital located in Mthatha, the main city of the King Sabata Dalindyebo Municipality in the rural northeastern region of the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. The hospital's adult intensive care unit (ICU) comprises eight ICU beds and six high-dependency care beds.

2.2. Population and Sampling

The study population comprised patients admitted to the adult Intensive Care Unit (ICU) of Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital for more than 48 hours between January 2020 and December 2022. Secondary data for this study were obtained from the clinical records of these patients, following ethical approval (HREC: 062/2023) and the Eastern Cape Department of Health (EC_202308_025). A simple random sampling method was employed to select 113 clinical records. Patients with incomplete medical records were excluded from the study. The dataset included information on the participants' demographic characteristics, length of hospitalization (LOH), types of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), associated microorganisms, use of invasive medical devices (IMDs), underlying health conditions (UHCs), and patient outcomes. Relevant data were systematically reviewed and recorded in an Excel spreadsheet to establish a structured dataset for statistical analysis. This method ensured efficient data handling, organization, and preparation for subsequent statistical processing, with an emphasis on standardizing the extracted data to ensure its accessibility and readiness for analysis.

2.3. Data Analysis

Hospital records of ICU patients at Nelson Mandela Academic Hospital, Mthatha, were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics summarized the data, with results presented in graphs and tables. The Shapiro–Wilk test assessed the normality of quantitative data. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data and as median with interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Comparisons between two groups were conducted using the student’s t-test for normally distributed data and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed data. Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and proportions, with comparisons made using Fisher’s exact test, Pearson’s chi-square test, or the chi-square test, as appropriate. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent determinants of prolonged ICU admission and factors associated with healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

Although the research used secondary data with no risk to patients, all due ethical processes were observed. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Postgraduate Education, Training, and Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University (HREC: 062/2023) and the Eastern Cape Department of Health (EC_202308_025).

3. Results

Socio-Demographic Characteristics of ICU Patients

A total of 113 patients were included in this retrospective study. The patients' ages ranged from 13 to 80 years, with a median age of 33 years. The majority (53.1%) were between the ages of 13 and 34 years. Male patients constituted slightly more than half of the study population (51.1%). Additionally, 61.1% of the patients had at least one underlying chronic illness, such as diabetes, hypertension, chronic renal failure, or other conditions. Of the total patient cohort, 26.5% succumbed during their ICU stay (

Table 1).

Invasive Medical Device Usage Among ICU Patients

All 113 patients in the study had urinary catheters during their ICU admission. More than half of the patients (53.1%, 60/113) utilized a combination of all three invasive medical devices (mechanical ventilation, urinary catheter, and intravenous central line). Additionally, 20 patients had only a urinary catheter, while 14 patients used both urinary and intravenous (IV) catheters (

Table 2).

Distribution and Types of Hospital-Acquired Infections

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection was the most common HAI (8/25) followed by surgical site infection and ventilator-associated pneumonia (7/250 and central line bloodstream infection (6/25) (

Table 3).

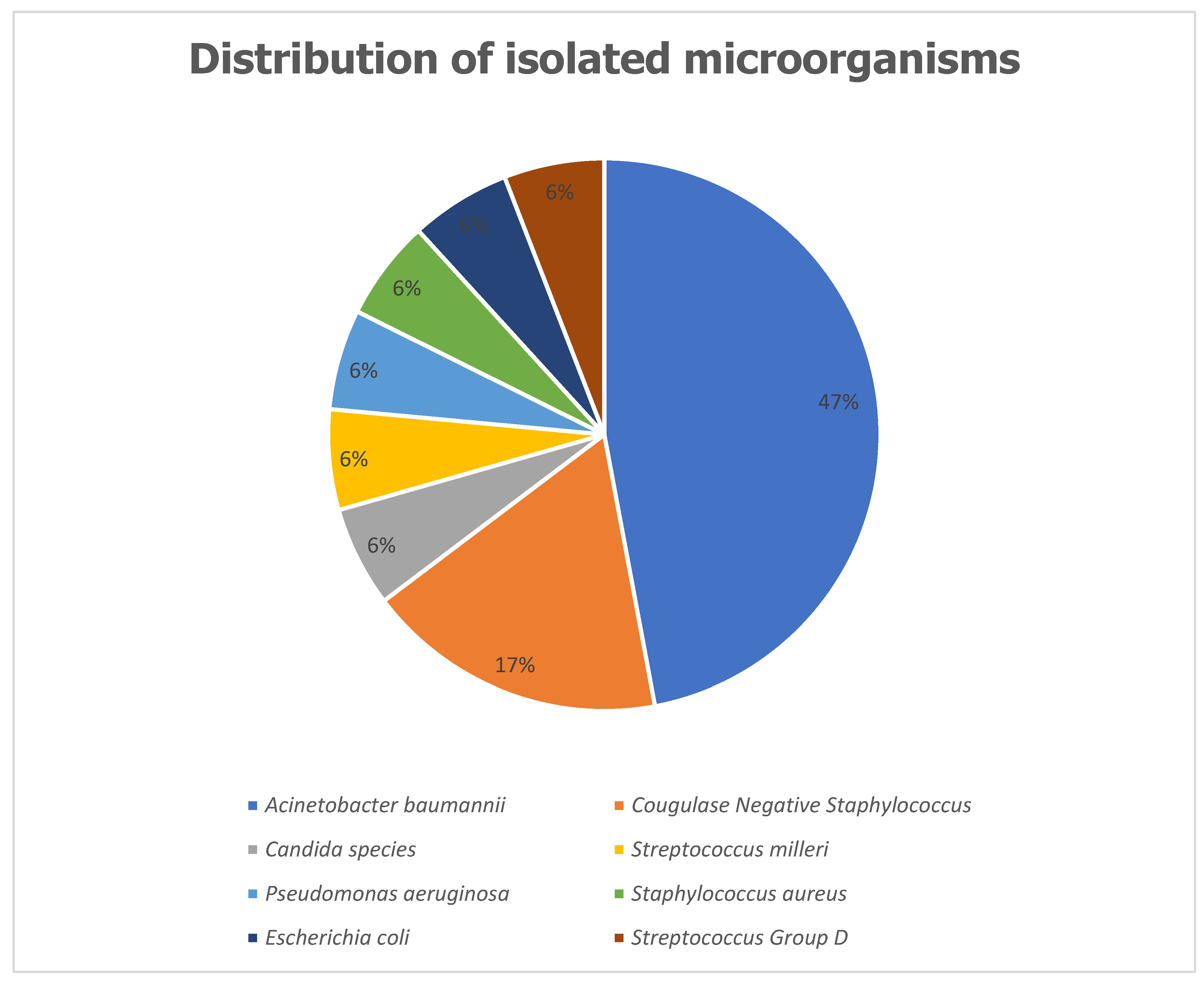

Distribution of Isolated Microorganisms

The most frequently isolated microorganism among patients with HAIs was

Acinetobacter baumannii complex, accounting for 8 cases (47%). This was followed by Coagulase-Negative

Staphylococci, identified in 3 cases (17%). Other isolated pathogens included

Staphylococcus aureus,

Escherichia coli, and

Candida species, each contributing 1 case (6%) (

Figure 1).

Hospital-Acquired Infections and Types of Invasive Medical Devices

Among patients who developed HAIs, 85% (21 out of 25) had all three invasive medical devices: mechanical ventilation, urinary catheter, and intravenous catheter. This represents a proportion of 35% (21 out of 60) of patients in this category. The prevalence of HAIs in this group was significantly higher compared to other categories (p = 0.02,

Table 4).

Factors Associated with Hospital-Acquired Infections

A univariate analysis was conducted to identify factors associated with the occurrence of HAIs, including gender, age, underlying health conditions, use of invasive medical devices, and length of stay in the ICU. Among these factors, only the length of ICU stays, and the use of invasive medical devices demonstrated a significant association with the development of HAIs (

Table 5).

Patients’ Outcome

Catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) was the only infection significantly associated with mortality in the ICU. Among participants with CAUTI, 87.5% (7/8) died, compared to 21.9% (23/105) of those without CAUTI (p < 0.001). In contrast, central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) (p = 0.573), surgical site infections (SSI) (p = 0.900), and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) (p = 0.058) showed no significant association with mortality due to hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) (

Table 6).

The Association Between Underlying Health Conditions and Outcome

71 (62.8%) of the 113 participants had an underlying health condition before admission to ICU. There was no association between the underlying health conditions and the patients’ outcomes (p=0.165) (

Table 7).

4. Discussion

This retrospective study included 113 patients, with ages ranging from 13 to 80 years and a median age of 33 years. The majority (53.1%) were between the ages of 13 and 34 years, and slightly more than half of the cohort were male (51.1%). A significant proportion of patients (61.1%) had at least one underlying chronic illness, such as diabetes, hypertension, or chronic renal failure. During their ICU stay, 26.5% of the patients succumbed to their condition (

Table 1). All patients had urinary catheters during their ICU admission. Over half (53.1%) of the patients used a combination of three invasive devices: mechanical ventilation, urinary catheter, and intravenous central line. Additionally, 20 patients used only a urinary catheter, while 14 patients used both urinary and intravenous catheters (

Table 2).

The most common hospital-acquired infection (HAI) was catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI), observed in 8 out of 25 patients, followed by surgical site infection (SSI) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP), each occurring in 7 out of 25 patients, and central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABSI) in 6 out of 25 patients (

Table 3). The predominant pathogen isolated was

Acinetobacter baumannii complex (47%), followed by Coagulase-negative

Staphylococci (17%), with fewer cases of

Staphylococcus aureus,

Escherichia coli, and

Candida species (6% each) (

Figure 1).

Among patients who developed HAIs, 85% (21 out of 25) had all three invasive medical devices, representing 35% of the 60 patients in this category. This group had a significantly higher prevalence of HAIs compared to others (p = 0.02,

Table 4). A univariate analysis revealed that the length of ICU stays, and use of invasive medical devices were significantly associated with the occurrence of HAIs. Logistic regression identified the invasive intravenous central line as the sole independent risk factor for acquiring HAIs. Regarding mortality, CAUTI was significantly associated with ICU mortality: 87.5% of patients with CAUTI died, compared to 21.9% of those without CAUTI (p < 0.001). Other infections (CLABSI, SSI, and VAP) did not show significant associations with mortality. Of the 113 participants, 71 (62.8%) had underlying health conditions, but these conditions were not significantly associated with patient outcomes (p = 0.165).

The findings of this study are consistent with those from other studies examining hospital-acquired infections (HAIs) in ICU settings. Like our study, previous research has identified CAUTI as a leading cause of HAIs in ICU patients [

13,

14], with mechanical ventilation and central venous lines being the most common risk factors [

15]. The association between the use of invasive devices and HAIs is well-established [

16], and our study's logistic regression analysis corroborates these findings, particularly the role of intravenous central lines as an independent risk factor for HAIs.

However, unlike studies that found a broader range of underlying health conditions linked to poor outcomes [

17], our study did not find significant associations between underlying chronic illnesses and mortality or HAI occurrence. This difference could be due to variations in patient populations or healthcare practices, such as infection control measures, which may mitigate the effects of pre-existing conditions in some ICU settings [

18].

The higher mortality associated with CAUTI in this study aligns with findings by Al-Hasan and colleagues [

19], who reported that CAUTI significantly increased ICU mortality rates. This contrasts with some studies, where the impact of CAUTI on mortality was less pronounced [

20]. Differences in patient demographics, infection severity, and management strategies may account for these disparities.

5. Conclusion

This study highlights the critical role of invasive medical devices, particularly the intravenous central line, in increasing the risk of hospital-acquired infections in ICU patients. CAUTI emerged as a key factor associated with mortality, emphasizing the need for improved infection prevention strategies in ICU settings. The findings are largely consistent with existing literature, although further research is needed to understand the varying impacts of underlying conditions and the specific pathogens involved in ICU-associated infections.

Funding

This research received no funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Postgraduate Education, Training, and Research Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Walter Sisulu University (HREC: 062/2023) and the Eastern Cape Department of Health (EC_202308_025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for this study was not obtained from the subjects involved because the research involved no risk to the subjects. The primary data were collected for purposes of patient management, not for research, and were de-identified to reduce the risk to privacy.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The data contains sensitive information that could compromise the privacy of the research participants. As such, access to these data is restricted and Trop. Med. Infect. Dis., and can only be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author, subject to approval by the relevant ethics review board.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge and appreciate the staff of adult ICU, NMAH Mthatha for granting the researchers permission to access their database.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest from any quarters. This study was not funded; it was purely the authors’ initiative to research an issue that is under-researched within the province.

Authors’ Contributions

SJ: data acquisition, and development of manuscript; CBB: data analysis, interpretation of data, and manuscript development; DTA: conception and design of the work; data acquisition, manuscript development, proofreading of the final manuscript, and corresponding author.

References

- Sikora, A.; Zahra, F. Healthcare-associated infections (HAIs): Epidemiology and outcomes. Infection and Drug Resistance 2021, 14, 1757–1767. [Google Scholar]

- Voidazan, S.; Moldovan, R.; Voidazan, S.; et al. Healthcare-associated infections: Risk factors and epidemiology. Journal of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology 2020, 6, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Khammarnia, M.; Ravangard, R.; Poursheikhali, A.; Setoodehzadeh, F. Hospital-acquired infections and their risk factors. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 2021, 42, 1040–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Boev, C.; Kiss, E. Hospital-acquired infections: Current trends and prevention. Critical Care Nursing Clinics of North America 2017, 29, 51–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugliotta, G.; Corcione, S.; De Rosa, F. G.; Di Perri, G. Antimicrobial stewardship programs in resource-limited settings: Current state and future challenges. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2020, 55, 105827. [Google Scholar]

- Monegro, A. F.; Muppidi, V.; Regunath, H. Hospital-acquired infections. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Metersky, M. L.; Kalil, A. C. Management of hospital-acquired and ventilator-associated pneumonia. Journal of the American Medical Association 2017, 317, 1168–1169. [Google Scholar]

- Leoncio, J. M.; Souza, S. M.; Andrade, D. Burden of healthcare-associated infections in neonates: A systematic review. Brazilian Journal of Infectious Diseases 2019, 23, 280–287. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, Z.; Godman, B.; Azhar, F.; Hassali, M. A. Point prevalence surveys of healthcare-associated infections: A global review. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology 2019, 40, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar]

- Dramowski, A.; Whitelaw, A.; Cotton, M. F. Healthcare-associated infections in South Africa: Challenges and opportunities for infection prevention. South African Medical Journal 2020, 110, 625–633. [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Healthcare-associated infections: Surveillance and prevention guidelines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hai. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Infection prevention and control: Global guidelines. Available at: https://www.who.int/infection-control. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Said, A.; et al. Prevalence and risk factors of hospital-acquired infections in ICU patients: A multicenter study. Journal of Hospital Infection 2020, 104, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, A. J.; et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections and the role of invasive devices in ICU patients: A cohort study. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021, 104, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, K. O.; et al. Hospital-acquired infections and their control measures in intensive care units: A review of global practices. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2019, 4, 67. [Google Scholar]

- Mendling, W.; et al. Risk factors for catheter-associated urinary tract infections in ICU settings: A systematic review. Clinical Microbiology and Infection 2018, 24, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chastre, J.; et al. Impact of chronic underlying conditions on outcomes of ICU patients with hospital-acquired infections: A prospective cohort study. Critical Care Medicine 2021, 49, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Rojas, R.; et al. Impact of infection prevention practices on the incidence of hospital-acquired infections in the ICU: A longitudinal study. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2022, 43, 1013–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hasan, M. N.; et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections and mortality in ICU patients: A retrospective cohort study. Journal of Critical Care Medicine 2020, 35, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kanj, S. S.; et al. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in intensive care units: Epidemiology, risk factors, and mortality. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2019, 219, 1322–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).