Submitted:

28 December 2024

Posted:

31 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chlamydia Stocks and Antigens

2.2. Mice

2.3. Construction of the Vaccine Vector, pCT-MECA and Expression of MECA by Immunoblotting Analysis

2.4. Production of rVCG-MECA Vaccine

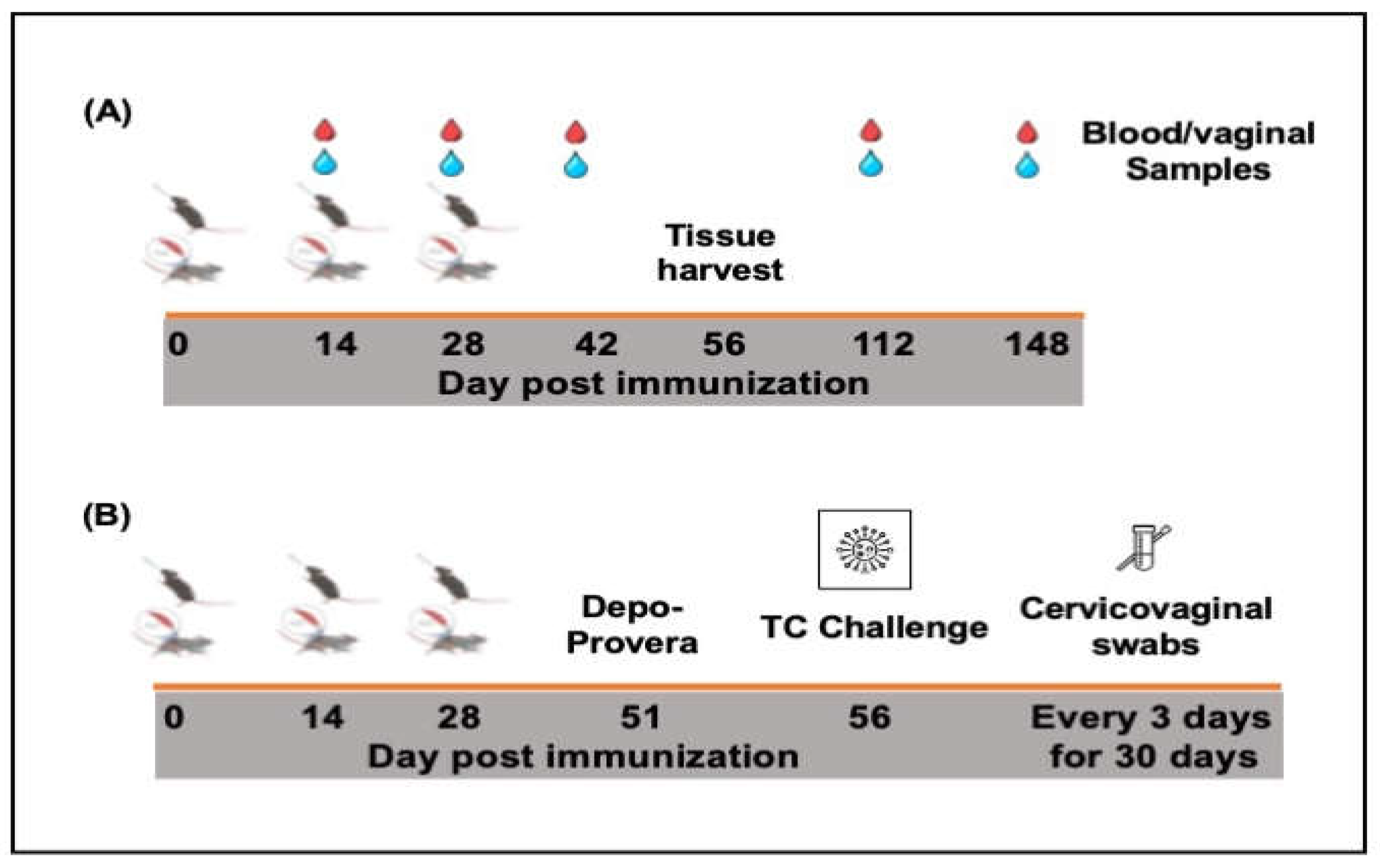

2.5. Immunization and Challenge of Immunized Mice

2.6. Determination of Antigen-Specific Humoral Immune Responses

2.7. Determination of Serum Antibody Avidity

2.8. Assessment of Antigen-Specific Cellular Immune Responses

3. Results

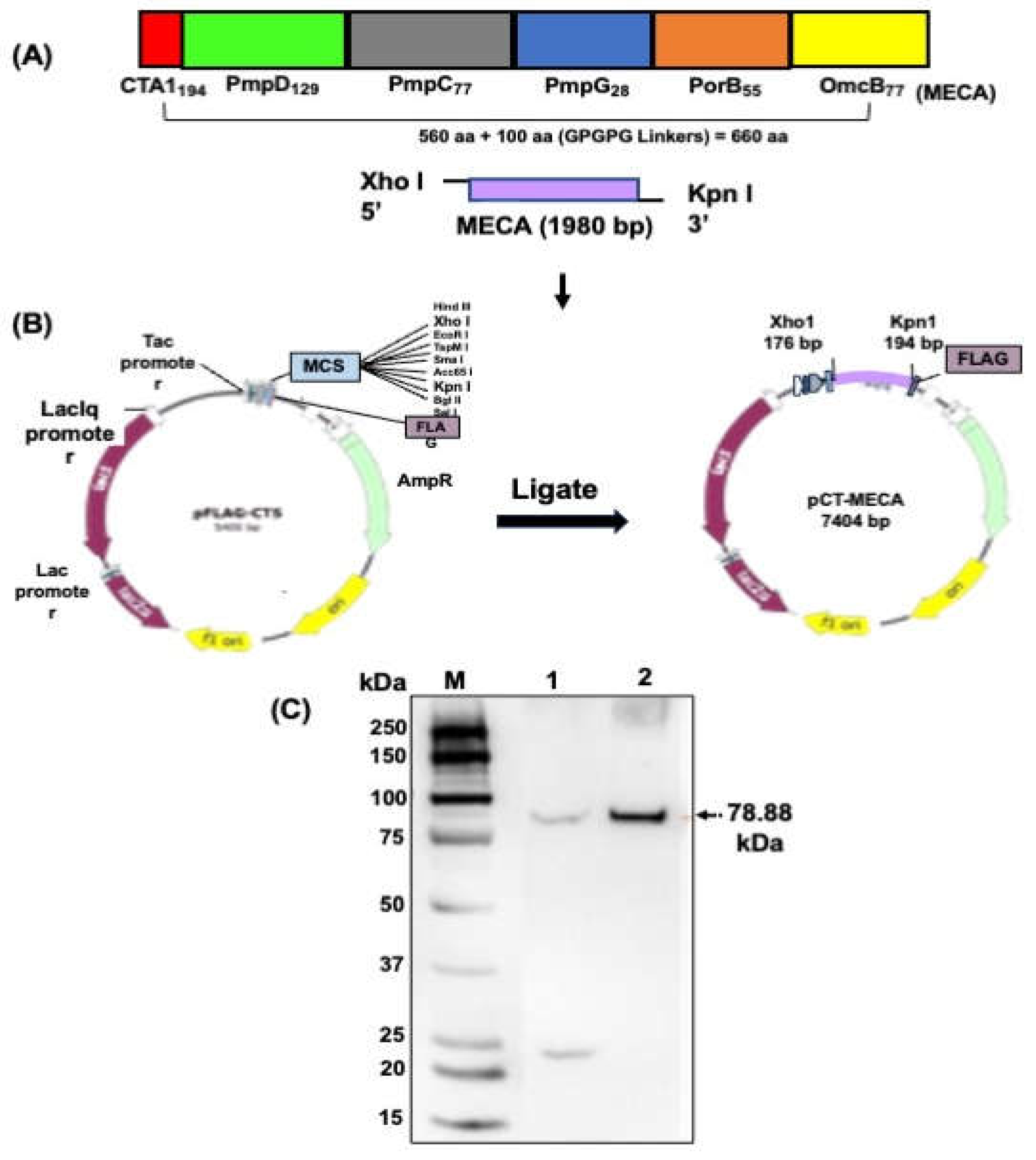

3.1. Construction of Plasmid pCT-MECA and VCG Expression of rMECA Protein

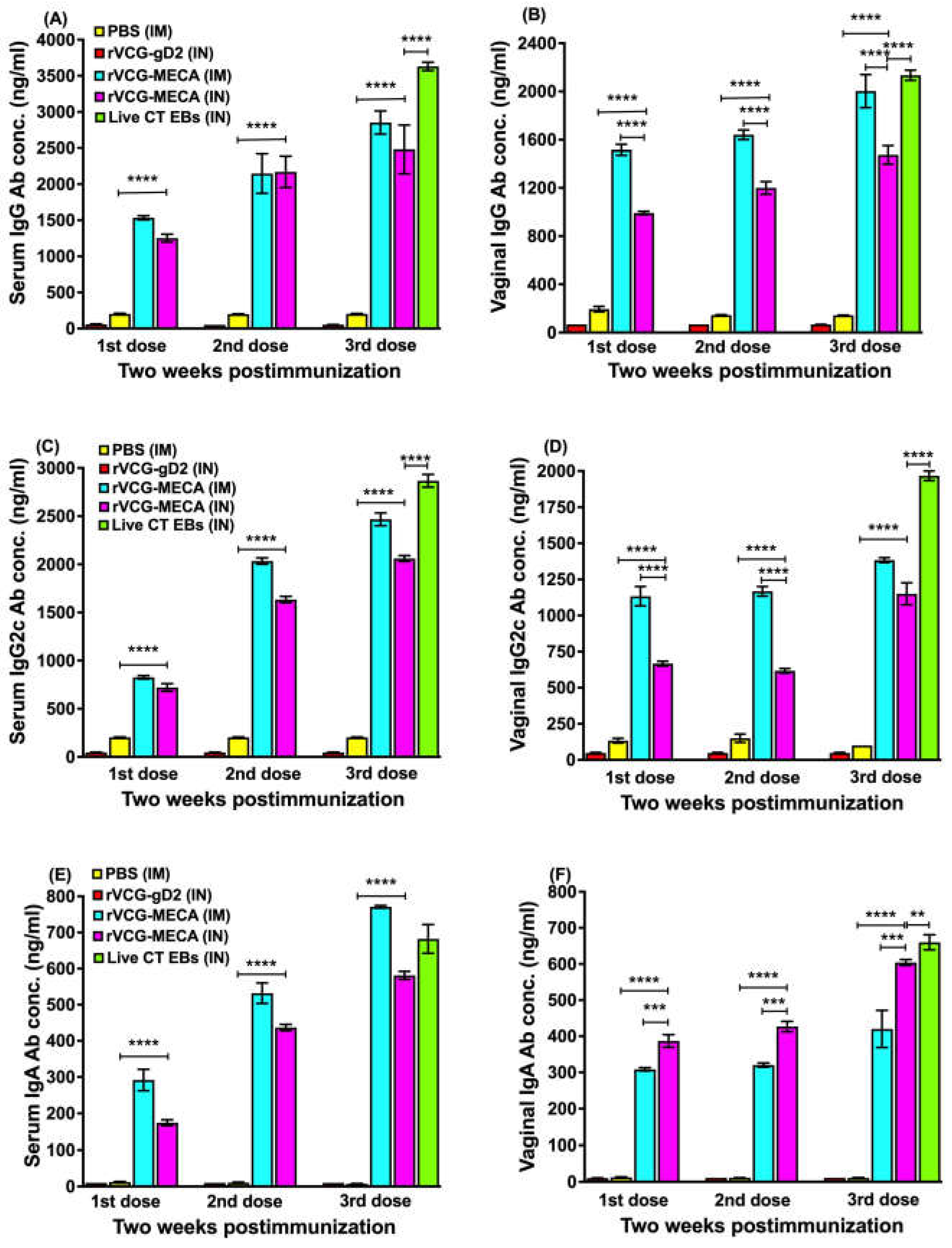

3.2. IM and IN Immunization with rVCG-MECA Induced Robust Antigen-Specific Antibodies in Serum and Vaginal Secretions

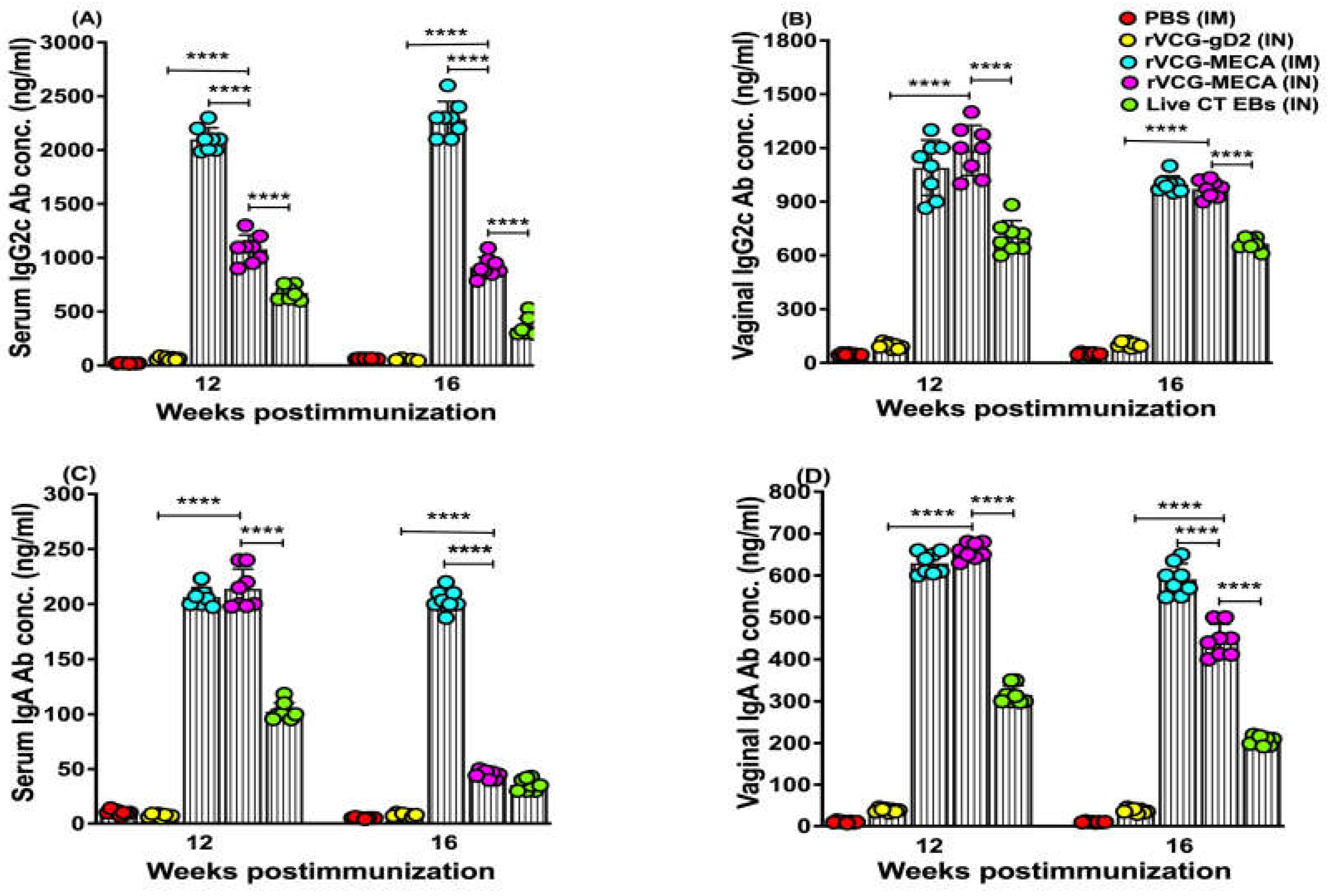

3.3. Vaccine-Induced CT-Specific IgG2c and IgA Antibodies Persisted in Serum and Vaginal Secretions

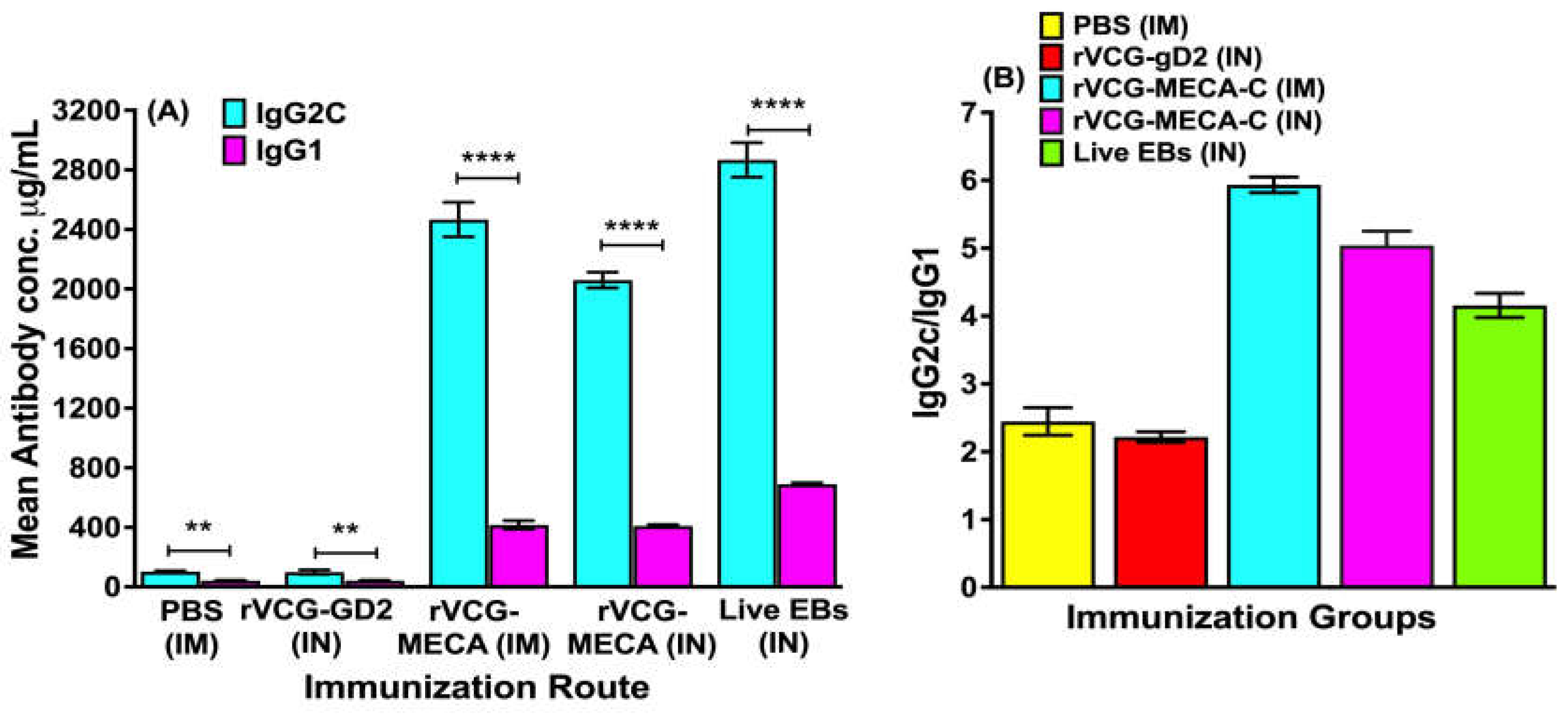

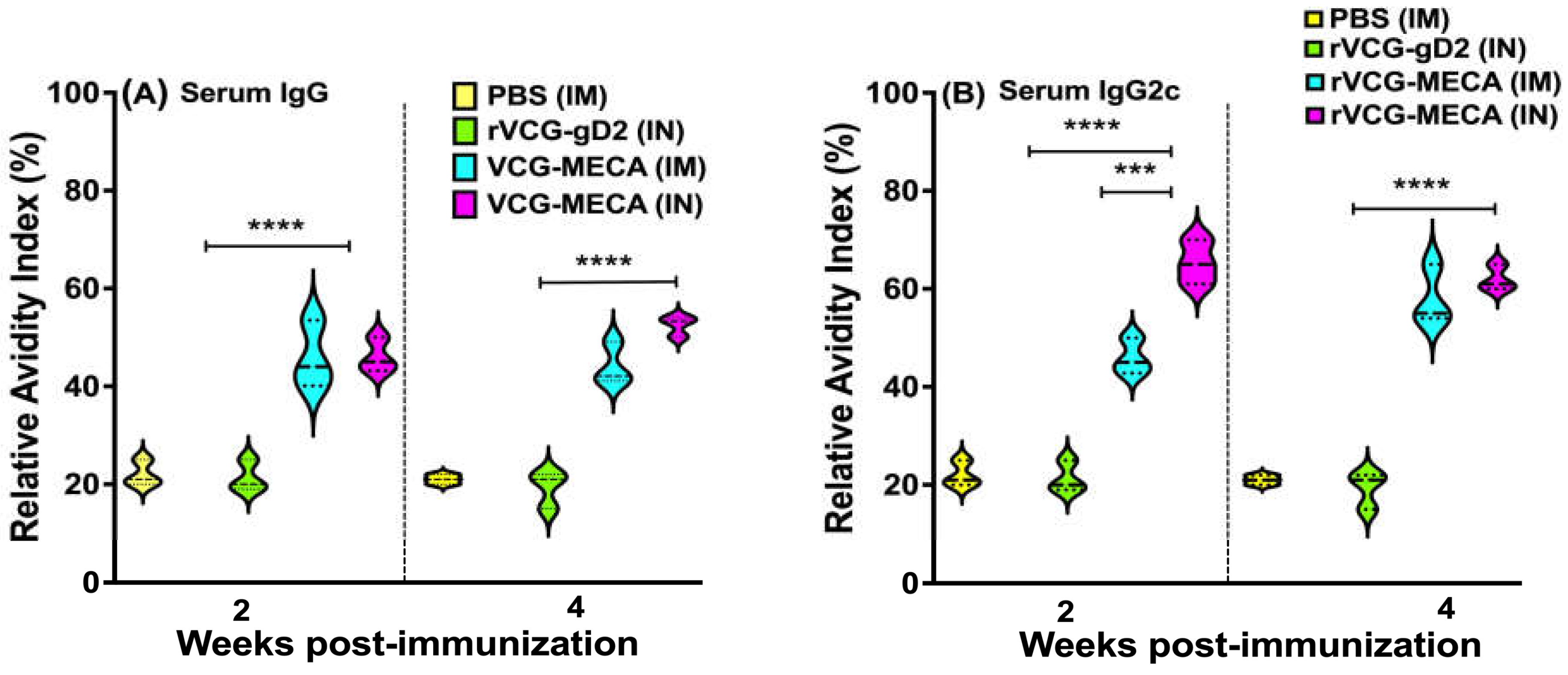

3.4. Avidity of Antigen-Specific Serum IgG and IgG2c Antibodies

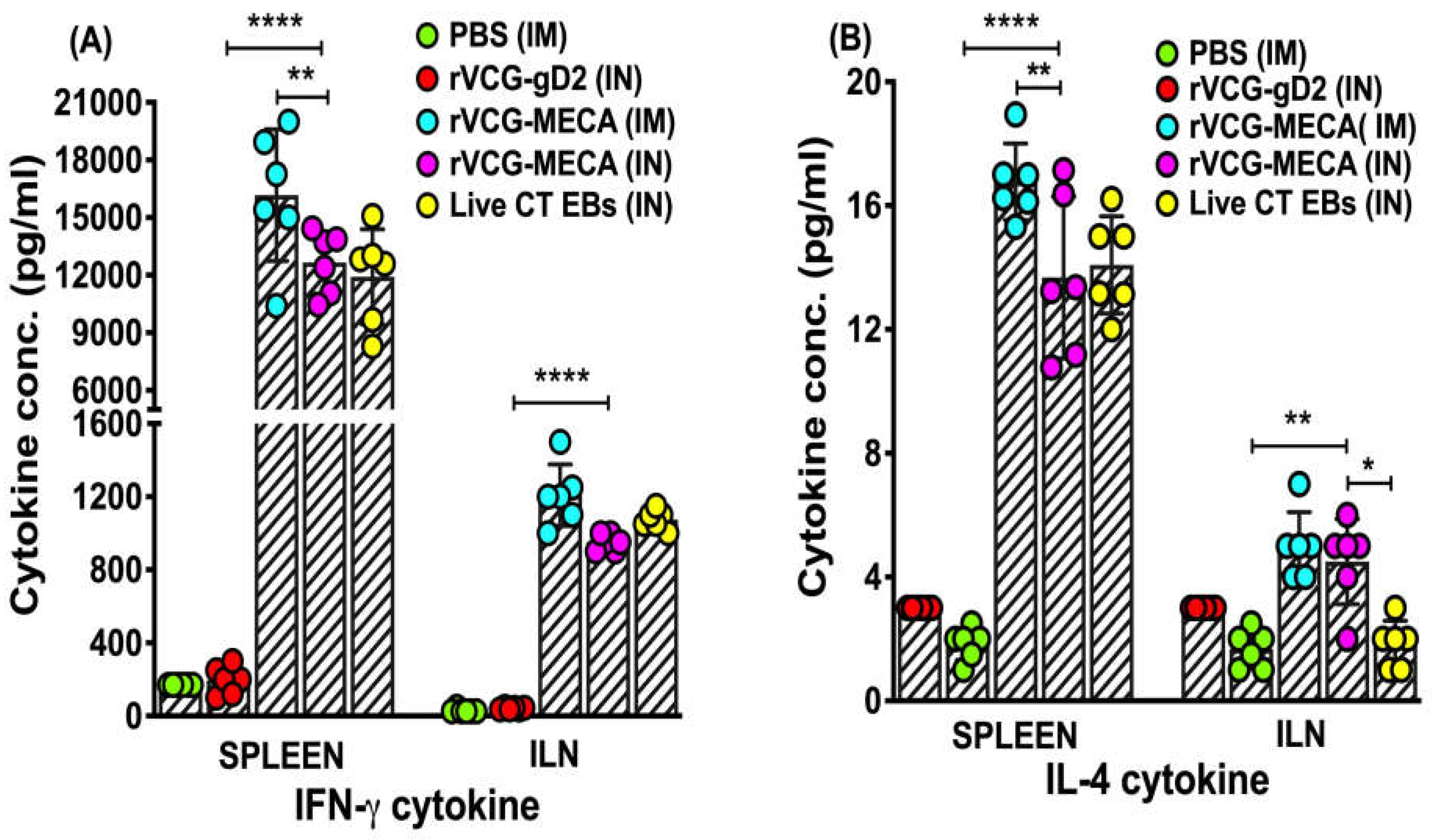

3.5. High Levels of Antigen-Specific IFN-γ Were Induced in Mucosal and Systemic Tissues Following Immunization with rVCG-MECA

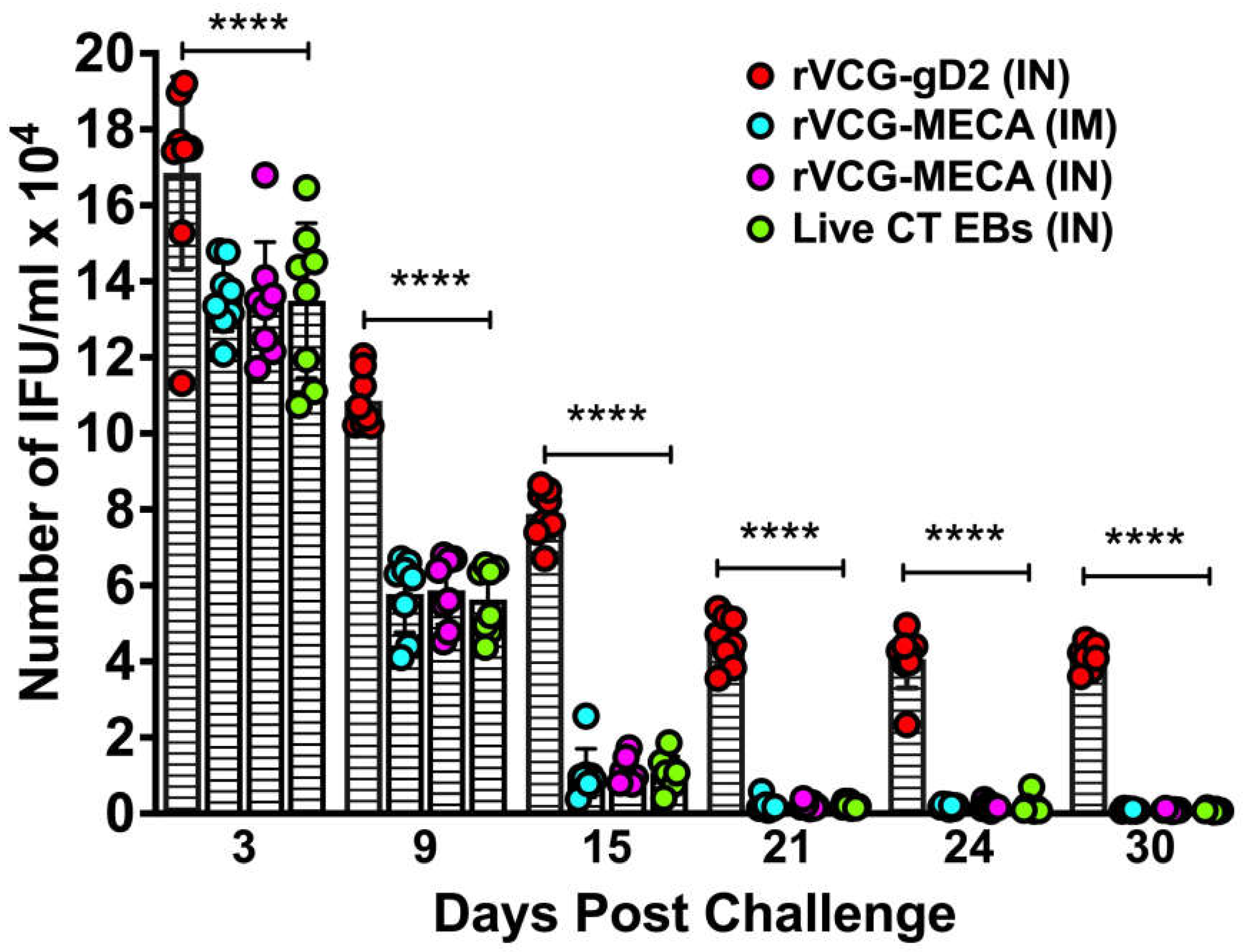

3.6. Immune Effectors Stimulated by Immunization with rVCG-MECA Protected Mice Against Transcervical Challenge with Live CT EBs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CDC, C.f.D.C.a.P. National Overview of STIs, 2022; 2022.

- Farley, T.A.; Cohen, D.A.; Elkins, W. Asymptomatic sexually transmitted diseases: the case for screening. Prev Med 2003, 36, 502–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stamm, W.E. Chlamydia trachomatis infections: progress and problems. J Infect Dis 1999, 179 Suppl 2, S380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonke, N.; Aragon, M.; Phillips, J.K. Chlamydial and Gonococcal Infections: Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Am Fam Physician 2022, 105, 388–396. [Google Scholar]

- Curry, A.; Williams, T.; Penny, M.L. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention. Am Fam Physician 2019, 100, 357–364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haggerty, C.L.; Gottlieb, S.L.; Taylor, B.D.; Low, N.; Xu, F.; Ness, R.B. Risk of sequelae after Chlamydia trachomatis genital infection in women. J Infect Dis 2010, 201 Suppl 2, S134–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.A.; Robinette, A.; Montgomery, M.; Almonte, A.; Cu-Uvin, S.; Lonks, J.R.; Chapin, K.C.; Kojic, E.M.; Hardy, E.J. Extragenital Infections Caused by Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: A Review of the Literature. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol 2016, 2016, 5758387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrott, S.L.; Kar, S.P. Appraisal of the causal effect of Chlamydia trachomatis infection on epithelial ovarian cancer risk: a two-sample Mendelian randomisation study. medRxiv, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, E.R.; Redgrove, K.A.; Mooney, A.R.; Mihalas, B.P.; Sutherland, J.M.; Carey, A.J.; Armitage, C.W.; Trim, L.K.; Kollipara, A.; Mulvey, P.B.M.; et al. Chronic testicular Chlamydia muridarum infection impairs mouse fertility and offspring developmentdagger. Biol Reprod 2020, 102, 888–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, A.H.; Follmann, F.; Dietrich, J. Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine development - a view on the current challenges and how to move forward. Expert Rev Vaccines 2022, 21, 1555–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, A.K.; Li, W.; Ramsey, K.H. Immunopathogenesis of Chlamydial Infections. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2018, 412, 183–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunham, R.C. The genome, microbiome and evolutionary medicine. CMAJ 2018, 190, E162–E166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunham, R.C.; Rey-Ladino, J. Immunology of Chlamydia infection: implications for a Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine. Nat Rev Immunol 2005, 5, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poston, T.B.; Gottlieb, S.L.; Darville, T. Status of vaccine research and development of vaccines for Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Vaccine 2019, 37, 7289–7294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, S.M.; McKay, P.F. Chlamydia trachomatis: Cell biology, immunology and vaccination. Vaccine 2021, 39, 2965–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayston, J.T.; Wang, S.-P.; Yeh, L.J.; Kuo C, C. Importance of reinfection in the pathogenesis of trachoma. Rev.Infect.Dis. 1985, 7, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, J.; Dawson, C.R. In Human chlamydial infections, PSG Publishing Company: Littleton, MA, 1978.

- Eko, F.O.; Lubitz, W.; McMillan, L.; Ramey, K.; Moore, T.T.; Ananaba, G.A.; Lyn, D.; Black, C.M.; Igietseme, J.U. Recombinant Vibrio cholerae ghosts as a delivery vehicle for vaccinating against Chlamydia trachomatis. Vaccine 2003, 21, 1694–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eko, F.O.; Mayr, U.B.; Attridge, S.R.; Lubitz, W. Characterization and immunogenicity of Vibrio cholerae ghosts expressing toxin-coregulated pili. J Biotechnol 2000, 83, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eko, F.; Ekong, E.; Okenu, D.; He, Q.; Ananaba, G.; Black, C.; Igietseme, J. Induction of immune memory by a multisubunit chlamydial. Vaccine 2011, 2011, 2011–2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, R.; Omosun, Y.; Igietseme, J.U.; Fujihashi, K.; Eko, F.O. Route of Vaccine Administration Influences the Impact of Fms-Like Tyrosine Kinase 3 Ligand (Flt3L) on Chlamydial-Specific Protective Immune Responses. Frontiers in immunology 2019, 10, 1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redgrove, K.A.; McLaughlin, E.A. The Role of the Immune Response in Chlamydia trachomatis Infection of the Male Genital Tract: A Double-Edged Sword. Front Immunol 2014, 5, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helgeby, A.; Robson, N.C.; Donachie, A.M.; Beackock-Sharp, H.; Lövgren, K.; Schön, K.; Mowat, A.; Lycke, N.Y. The combined CTA1-DD/ISCOM adjuvant vector promotes priming of mucosal and systemic immunity to incorporated antigens by specific targeting of B cells. J Immunol 2006, 176, 3697–3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agren, L.; Sverremark, E.; Ekman, L.; Schön, K.; Löwenadler, B.; Fernandez, C.; Lycke, N. The ADP-ribosylating CTA1-DD adjuvant enhances T cell-dependent and independent responses by direct action on B cells involving anti-apoptotic Bcl-2- and germinal center-promoting effects. J Immunol 2000, 164, 6276–6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.C.; Choi, J.A.; Park, H.; Yang, E.; Noh, S.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, M.J.; Song, M.; Park, J.H. Pharmaceutical and Immunological Evaluation of Cholera Toxin A1 Subunit as an Adjuvant of Hepatitis B Vaccine Microneedles. Pharm Res 2023, 40, 3059–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eriksson, A.M.; Schön, K.M.; Lycke, N.Y. The cholera toxin-derived CTA1-DD vaccine adjuvant administered intranasally does not cause inflammation or accumulate in the nervous tissues. J Immunol 2004, 173, 3310–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubo, A.; Stephens, R.S. Characterization and functional analysis of PorB, a Chlamydia porin and neutralizing target. Mol Microbiol 2000, 38, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunham, R.C.; Peeling, R.W. Chlamydia trachomatis antigens: role in immunity and pathogenesis. Infect Agents Dis 1994, 3, 218–233. [Google Scholar]

- Vasilevsky, S.; Stojanov, M.; Greub, G.; Baud, D. Chlamydial polymorphic membrane proteins: regulation, function and potential vaccine candidates. Virulence 2016, 7, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Karunakaran, K.P.; Jiang, X.; Brunham, R.C. Evaluation of a multisubunit recombinant polymorphic membrane protein and major outer membrane protein T cell vaccine against Chlamydia muridarum genital infection in three strains of mice. Vaccine 2014, 32, 4672–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eko, F.; Lubitz, W.; McMillan, L.; Ramey, K.; Moore, T.; Ananaba, G.A.; Lyn, D.; Black, C.M.; Igietseme, J.U. Recombinant Vibrio cholerae ghosts as a delivery vehicle for vaccinating against Chlamydia trachomatis. Vaccine 2003, 21, 1694–1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Parnell, M.; Caldwell, H.D. Protective efficacy of a parenterally administered MOMP-derived synthetic oligopeptide vaccine in a murine model of Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection: serum neutralizing IgG antibodies do not protect against chlamydial genital tract infection. Vaccine 1995, 13, 1023–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmillan, L.; Ifere, G.O.; He, Q.; Igietseme, J.U.; Kellar, K.L.; Okenu, D.M.; Eko, F.O. A recombinant multivalent combination vaccine protects against Chlamydia and genital herpes. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2007, 49, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzewikoswki de Lima, G.; Rodrigues, T.S.; Portilho, A.I.; Correa, V.A.; Gaspar, E.B.; De Gaspari, E. Immune responses of meningococcal B outer membrane vesicles in middle-aged mice. Pathog Dis 2020, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eko, F.O.; Ekong, E.; He, Q.; Black, C.M.; Igietseme, J.U. Induction of immune memory by a multisubunit chlamydial vaccine. Vaccine 2011, 29, 1472–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Pais, R.; Ohandjo, A.; He, C.; He, Q.; Omosun, Y.; Igietseme, J.U.; Eko, F.O. Comparative evaluation of the protective efficacy of two formulations of a recombinant Chlamydia abortus subunit candidate vaccine in a mouse model. Vaccine 2015, 33, 1865–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eko, F.O.; Mania-Pramanik, J.; Pais, R.; Pan, Q.; Okenu, D.M.; Johnson, A.; Ibegbu, C.; He, C.; He, Q.; Russell, R.; et al. Vibrio cholerae ghosts (VCG) exert immunomodulatory effect on dendritic cells for enhanced antigen presentation and induction of protective immunity. BMC Immunol 2014, 15, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pais, R.; Omosun, Y.; He, Q.; Blas-Machado, U.; Black, C.; Igietseme, J.U.; Fujihashi, K.; Eko, F.O. Rectal administration of a chlamydial subunit vaccine protects against genital infection and upper reproductive tract pathology in mice. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0178537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujihashi, K.; Koga, T.; van Ginkel, F.W.; Hagiwara, Y.; McGhee, J.R. A dilemma for mucosal vaccination: efficacy versus toxicity using enterotoxin-based adjuvants. Vaccine 2002, 20, 2431–2438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekong, E.E.; Okenu, D.; Mania-Pramanik, J.; He, Q.; Igietseme, J.; Ananaba, G.; Lyn, D.; Black, C.; Eko, F. A Vibrio cholerae ghost-based subunit vaccine induces cross-protective chlamydial immunity that is enhanced by CTA2B, the nontoxic derivative of cholera toxin. FEMS Immunology & Medical Microbiology 2009, 55, 280–291. [Google Scholar]

- Bemark, M.; Bergqvist, P.; Stensson, A.; Holmberg, A.; Mattsson, J.; Lycke, N.Y. A unique role of the cholera toxin A1-DD adjuvant for long-term plasma and memory B cell development. J Immunol 2011, 186, 1399–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, K.A.; Carey, A.J.; Lycke, N.; Timms, P.; Beagley, K.W. CTA1-DD is an effective adjuvant for targeting anti-chlamydial immunity to the murine genital mucosa. J Reprod Immunol 2009, 81, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schussek, S.; Bernasconi, V.; Mattsson, J.; Wenzel, U.A.; Strömberg, A.; Gribonika, I.; Schön, K.; Lycke, N.Y. The CTA1-DD adjuvant strongly potentiates follicular dendritic cell function and germinal center formation, which results in improved neonatal immunization. Mucosal Immunol 2020, 13, 545–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilevsky, S.; Greub, G.; Nardelli-Haefliger, D.; Baud, D. Genital Chlamydia trachomatis: understanding the roles of innate and adaptive immunity in vaccine research. Clin Microbiol Rev 2014, 27, 346–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rixon, J.A.; Depew, C.E.; McSorley, S.J. Th1 cells are dispensable for primary clearance of Chlamydia from the female reproductive tract of mice. PLoS Pathog 2022, 18, e1010333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tifrea, D.F.; Pal, S.; de la Maza, L.M. A Recombinant Chlamydia trachomatis MOMP Vaccine Elicits Cross-serogroup Protection in Mice Against Vaginal Shedding and Infertility. J Infect Dis 2020, 221, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, A.K.; Chambers, J.P.; Meier, P.A.; Zhong, G.; Arulanandam, B.P. Intranasal Vaccination with a Secreted Chlamydial Protein Enhances Resolution of Genital Chlamydia muridarum Infection, Protects against Oviduct Pathology, and Is Highly Dependent upon Endogenous Gamma Interferon Production. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 666–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Meara, C.P.; Armitage, C.W.; Harvie, M.C.G.; Timms, P.; Lycke, N.Y.; Beagley, K.W. Immunization with a MOMP-Based Vaccine Protects Mice against a Pulmonary Chlamydia Challenge and Identifies a Disconnection between Infection and Pathology. PLoS One 2013, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, D.J.; Huo, Z.; Barnett, S.; Kromann, I.; Giemza, R.; Galiza, E.; Woodrow, M.; Thierry-Carstensen, B.; Andersen, P.; Novicki, D.; et al. Transient facial nerve paralysis (Bell's palsy) following intranasal delivery of a genetically detoxified mutant of Escherichia coli heat labile toxin. PLoS One 2009, 4, e6999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmichael, J.R.; Pal, S.; Tifrea, D.; de la Maza, L.M. Induction of protection against vaginal shedding and infertility by a recombinant Chlamydia vaccine. Vaccine 2011, 29, 5276–5283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Lin, H.; Tang, L.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhong, G. Oral Chlamydia vaccination induces transmucosal protection in the airway. Vaccine 2018, 36, 2061–2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhu, C.; Zhang, T.; Tian, Q.; Zhang, N.; Morrison, S.; Morrison, R.; Xue, M.; Zhong, G. Nonpathogenic Colonization with Chlamydia in the Gastrointestinal Tract as Oral Vaccination for Inducing Transmucosal Protection. Infect Immun 2018, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, S.G.; Morrison, R.P. The protective effect of antibody in immunity to murine chlamydial genital tract reinfection is independent of immunoglobulin A. Infect Immun 2005, 73, 6183–6186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunham, R.C.; Kuo, C.-C.; Cles, L.; Holmes, K.K. Correlation of host immune response with quantitative recovery of Chlamydia trachomatis from the human endocervix. Infect.Immun. 1983, 39, 1491–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, R.P.; Feilzer, K.; Tumas, D.B. Gene knockout mice establish a primary protective role for major histocompatibility complex class II-restricted responses in Chlamydia trachomatis genital tract infection. Infect. Immun 1995, 63, 4661–4668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shillova, N.; Howe, S.E.; Hyseni, B.; Ridgell, D.; Fisher, D.J.; Konjufca, V. Chlamydia-Specific IgA Secretion in the Female Reproductive Tract Induced via Per-Oral Immunization Confers Protection against Primary Chlamydia Challenge. Infect Immun 2020, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Igietseme, J.U.; Eko, F.O.; Black, C.M. Contemporary approaches to designing and evaluating vaccines against Chlamydia. Expert Rev Vaccines 2003, 2, 129–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, R.; Caldwell, H. Immunity to murine chlamydial genital infection. Infect Immun 2002, 70, 2741–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Murthy, A.K.; Guentzel, M.N.; Seshu, J.; Forsthuber, T.G.; Zhong, G.; Arulanandam, B.P. Antigen-Specific CD4+ T Cells Produce Sufficient IFN-{gamma} to Mediate Robust Protective Immunity against Genital Chlamydia muridarum Infection. J Immunol 2008, 180, 3375–3382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, C.V.; Zhang, X.; Giovannone, N.; Sennott, E.L.; Starnbach, M.N. Protective immunity against Chlamydia trachomatis can engage both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and bridge the respiratory and genital mucosae. J Immunol 2015, 194, 2319–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G.; de la Maza, L.M. Activation of mouse peritoneal macrophages in vitro or in vivo by recombinant murine gamma interferon inhibits the growth of Chlamydia trachomatis serovar L1. Infect.Immun. 1988, 56, 3322–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rank, R.G.; Whittum-Hudson, J.A. Protective immunity to chlamydial genital infection: evidence from animal studies. J Infect Dis 2010, 201 Suppl 2, S168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicetti Miguel, R.D.; Quispe Calla, N.E.; Pavelko, S.D.; Cherpes, T.L. Intravaginal Chlamydia trachomatis Challenge Infection Elicits TH1 and TH17 Immune Responses in Mice That Promote Pathogen Clearance and Genital Tract Damage. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0162445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturdevant, g.; Caldwell, H. Innate immunity is sufficient for the clearance of Chlamydia trachomatis from the female mouse genital tract. Pathog Dis. 2014, 72, 72–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, A.T.; Braun, K.M.; Carabeo, R.A. Characterization of the Growth of Chlamydia trachomatis in In Vitro-Generated Stratified Epithelium. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2017, 7, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, A.; Chaganty, B.; Li, W.; Guentzel, M.; Chambers, J.; Seshu, J.; G, Z.; Arulanandam, B. A limited role for antibody in protective immunity induced by rCPAF and CpG vaccination against primary genital Chlamydia muridarum challenge. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009, 2009, 2009–2009. [Google Scholar]

- O'Meara, C.P.; Armitage, C.W.; Harvie, M.C.; Andrew, D.W.; Timms, P.; Lycke, N.Y.; Beagley, K.W. Immunity against a Chlamydia infection and disease may be determined by a balance of IL-17 signaling. Immunol Cell Biol 2014, 92, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S.; Peterson, E.M.; Rappuoli, R.; Ratti, G.; de la Maza, L.M. Immunization with the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein, using adjuvants developed for human vaccines, can induce partial protection in a mouse model against a genital challenge. Vaccine 2006, 24, 766–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zheng, K.; Tan, Y.; Wen, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, Q.; Yu, J.; Xu, M.; Tan, M.; Wu, Y. A recombinant multi-epitope peptide vaccine based on MOMP and CPSIT_p6 protein protects against Chlamydia psittaci lung infection. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2019, 103, 941–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Q.; Niu, H.; Li, Z.; Zhang, G.; Hu, L.; Wang, B.; Li, J.; Yu, H.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; et al. Subunit vaccine consisting of multi-stage antigens has high protective efficacy against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in mice. PLoS One 2013, 8, e72745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Maza, L.M.; Zhong, G.; Brunham, R.C. Update on Chlamydia trachomatis Vaccinology. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2017, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, T.; Medhavi, F.N.U.; Richardson, S.; Omosun, Y.O.; Eko, F.O. In silico design and analysis of a multiepitope vaccine against Chlamydia. Pathogens and disease 2024, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).