Introduction

There is an emerging body of research which suggests that qualitative researchers who engage in trauma-focused research face a risk for experiencing research-induced distress (RID) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]; with such distress having been found to take a number of forms including researcher fears for their own physical wellbeing [

8,

9,

10,

11], distressing emotional states (e.g., sadness/tearfulness, fear, or anxiety) [

9,

12], and symptoms of traumatic stress, including re-experiencing phenomena [

4]. Although RID has been most often studied among researchers who have had direct (face-to-face) contact with research participants, it has also been noted among members of research teams who do not have direct contact with participants including: individuals who are employed to transcribe or code recorded interviews [

13], researchers who examine archival material [

1], and research supervisors [

14].

The limited number of studies that have reported prevalence rates for RID among social researchers suggest that RID is relatively common. In a study conducted by Whitt-Woosley and colleague [

15] the prevalence rate for RID was found to be 57.7%, with qualitative researchers reporting significantly higher overall distress levels than quantitative researchers. With respect to specific types of RID, prevalence estimates for psychological distress have been found to vary from 18% to 44% [

16,

17], with comparative estimates for: (a) job burnout ranging from 35.5% to 54% [

17,

18], (b) feeling unsafe: 37.2% [

16], and (c) symptoms of traumatic stress: 9.1% [

16].

1.1. Conceptualizing Research-Induced Distress

In their work on contagious trauma, Coddington and colleague [

19,

20] highlight the mobility of trauma across place and time, and emphasize that conceptualizations of secondary traumatisation that focus exclusively on the ‘here and now’ of engagement with traumatised individuals, fail to adequately address the complexity of traumatic contagion. As Coddington (p.68) points out:

“Close engagement with the traumatized individuals does not necessarily result in the taking on of their feelings, but forms connections to other and often unrelated traumas in other times and spaces” [19].

With respect to RID, available studies suggest that direct contact with trauma survivors may be sufficient to trigger distressing trauma-related countertransference reactions, with such reactions at times mirroring the traumatic experiences reported by research participants [

21]. However, the mobility of trauma across time and space has been evident in the fact that RID has also been found to be associated with: (a) prior (at times unrelated) traumatic experiences that the researcher has experienced during their lives [

8,

9], as well as (b) traumatic events that are not restricted to the researcher’s life-span (e.g., intergenerational trauma) [

22]. Further, influences on RID have been found to emanate not only from the immediate context of research engagement but also from different spaces or places within the broader social ecology in which the researcher is embedded, including institutional and/or macrosystemic influences [

2].

1.2. Contextualising Research-Induced Distress

From a Conservation of Resources (COR) perspective [

23,

24] researchers can be viewed as individuals (with their own biographies and unique strengths and vulnerabilities) who are embedded in a network of family, interpersonal, organisational, and socio-cultural relationships; with the predictive validity of efforts designed to understand the experiences of researchers being likely to be limited if an attempt is made to separate any piece of this nested-self without reference to the greater whole [

24]. In a similar vein, contemporary conceptualisations of risk and resilience suggest that the outcome of exposure to adverse life circumstances can most usefully be construed as being the product of transactions between risk and salutary influences, with such influences emanating from various socioecological systems in which individuals are embedded [

25,

26,

27].

With respect to risk factors, RID has been found to be associated with (a) researchers’ inexperience, lack of training and preparation, and/or past history of exposure to traumatic life events [

28,

29,

30]; (b) events/experiences occurring during the process of engagement with participants, such as high workloads, researchers working alone, and/or threats to the researcher’s physical wellbeing [

28,

29,

31,

32]; (c) an inadequate institutional duty of care [

4,

33,

34,

35]; and/or (d) events/experiences emanating from the broader social system in which academia are embedded, including: dominant positivist research paradigms that often lead to the derision of interpretivist researchers , researching socially mediated forms of trauma such as poverty, warfare, and/or pandemic diseases, and/or national/international guidelines that do not adequately address RID among researchers [

16,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40].

Conversely, factors/mechanisms that have been found to mitigate RID include: (a) salutary personal characteristics such as emotional intelligence, high scores on measures of resilience, and the belief that the research is important/meaningful [

41,

42,

43]; (b) a proximal research context characterized by researchers working in pairs/teams, researchers being able to space interviews and take breaks, opportunities for discussion and informal debriefing by team members, and having/following carefully formulated safety protocols [

13,

44,

45]; (c) an adequate institutional duty of care [

4,

35]; (d) having a cultural broker on the research team in cases of cross-cultural research [

46]; and/or (e) the development of national and international guidelines designed to mitigate RID among researchers [

36].

1.3. RID among Child Abuse Researchers

Although there are a variety of emotionally laden research topics that have been found to be associated with RID, it is generally acknowledged that research on child maltreatment poses particular challenges for researchers [

47,

48,

49,

50,

51] According to Silverio and colleagues (p.68) the most difficult thing for child abuse researchers:

“…is not necessarily the morally objectionable or graphic information for which they can prepare themselves. They are the whispered insights which take researchers by surprise and leave a huge impact” [51].

Such strong reactions to researching child maltreatment have been found to occur regardless of whether data collection involves face-to face-interviews with children or file reviews of identified child abuse cases [

52].

Although much has been written about RID among child abuse researchers, there has to date been no systematic attempt to review available studies on the topic. As such, this systematic review is designed to address the question: “What are qualitative child abuse researchers’ perceptions of risk and protective factors for research-induced distress?”. For purposes of exhaustiveness, a broad definition of child abuse was employed in this review: with a child being defined as a person under that age of 19-years and with intrafamilial, extrafamilial, and structural forms of child maltreatment being considered as search terms.

2. Method

2.1. Research Question

What are qualitative child abuse researchers’ perceptions of risk and protective factors for research-induced distress?

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion criteria for this review were studies: (a) that employed qualitative or mixed-methods approaches (as long as qualitative data for mixed-methods studies were reported independently) , (b) in which child maltreatment was either the primary focus of the research or in which child maltreatment emerged as an important research focus during data collection, (c) that reported original empirical findings relating to researchers’ experiences of their research engagement, (d) that were published at any date prior to 2024 in peer reviewed journals, and (e) that were published in English.

Exclusion criteria were studies: (a) that employed a mixed-methods approach (in which qualitative data findings were not reported independently), (b) in which child maltreatment was not mentioned as a primary or emergent research focus, (c) that did not report original empirical findings relating to researchers’ experiences of their research engagement, (d) that were published after 2023, and/or (e) that were not published in English in peer reviewed journals.

2.3. Information Sources

We searched MEDLINE ProQuest, PsychINFO and Scopus for studies published prior to January 01 2024, with the search strategy being informed by four key constructs that were suggested by the research question: qualitative methods (or equivalent) AND researcher (or equivalent) AND child maltreatment (or equivalent) AND research-induced distress (or equivalent). In line with inclusion/exclusion criteria for the study, we included qualitative studies that reported original research in peer reviewed journals on any date prior to 2024, and excluded conference proceedings/abstracts, reviews of the extant literature, editorials, commentaries, and studies that were not published in English in peer reviewed journals. Specific search terms used in database searches were formulated by members of the research team, with a specialist librarian being recruited to validate the appropriateness of selected research terms. The final list of search terms used in database searches is presented in supplementary data (S1).

2.4. Study Selection

Reports identified through database searches were uploaded to EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics, PA, USA) with duplicates being removed using procedures suggested by Bramer and colleagues [

54]. Title/abstract/keyword review was conducted by two researchers (S.J.C. and D.R.) who worked independently and in duplicate; with any discrepancies between researcher’s evaluations being discussed until 100% agreement was reached. In cases where discrepancies could not be resolved between researchers a third researcher (S.R.V.) was used for blinded adjudication. Identical procedures, involving the same researchers, were employed in the full text evaluation of records for inclusion.

Two additional strategies were employed in order to identify additional records that may not have been captured in the database search. First, forward and backward citation searches were conducted in identified studies in order to identify any additional studies that were not identified in the database search. Second, the content pages of key child abuse and qualitative research journals were perused in order to identify additional studies that were published during the period 1989 to 2023 that appeared to be relevant to this review (with full-text reviews of all identified studies being conducted). Names of key journals searched are presented in supplementary data (S2).

These procedures identified a total 30 unique records that were included in this review [

11,

21,

22,

46,

49,

50,

51,

52,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76], with 21 records being identified via database searches [

22,

46,

49,

52,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

61,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

72,

73,

74,

75], seven records being identified via forward and backward citation searches [

11,

21,

50,

60,

62,

71,

76], and two records being identified by searching key journals (51,70). References for all identified studies are provided in the reference section and presented separately in supplementary data (S3)

Finally, a full-text review of all 30 identified reports confirmed that all reports addressed child maltreatment (or equivalent) and RID among qualitative researchers, However, none of the nine studies that were identified through citation searches or journal searches included key search terms – child (or equivalent) or child maltreatment (or equivalent) – in the title, abstract, or keywords, with this probably being the reason why they were not initially identified during the database search.

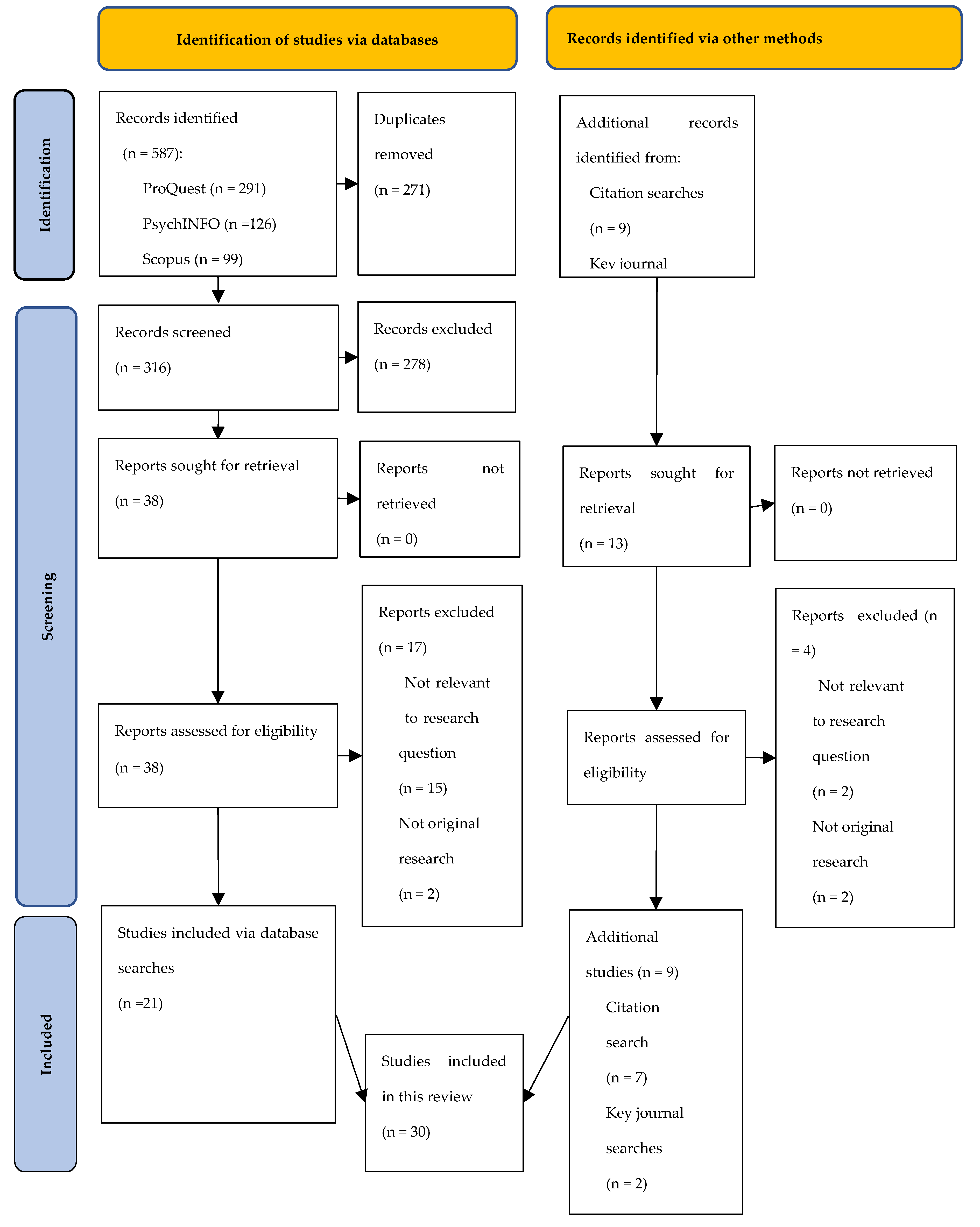

The PRISMA flow diagram for this selection procedure (

Figure 1), was guided by the framework proposed by Page and colleagues [

77].

2.5. Data Extraction

The following data were extracted from studies that were identified for inclusion in this review: (1) Researcher characteristics (number of researchers, discipline, geographical location, continent, country, country income level, research experience); (2) Study design (types of child maltreatment studied, participants, sampling strategy, research design, and data reduction strategies; and (3) Researchers’ perceptions of risk and salutary influences on RID outcomes. An initial data extraction sheet was developed by one researcher (S.J.C), with this sheet subsequently being adapted and augmented based on feedback provided by researchers during regular team meetings.

2.6. Data Synthesis

Data synthesis was conducted using a three-stage thematic synthesis approach for synthesizing qualitative data [

53,

78]. Stage 1 of this approach involved a line-by-line coding of all reviewed studies in order to identify statements relating to the wellbeing of researchers. Coding was conducted by two researchers (S.J.C. and D.R.) who worked independently, with research questions being put aside during coding in order to minimise an imposition of an a priori framework on the coding process. Finally, coders met to compare identified codes, with coding discrepancies being resolved through discussions between coders until consensus was reached. Finally, a team discussion, involving all researchers, was arranged to confirm that identified codes were exhaustive and that there was consistency in coder interpretation.

The second stage of the synthesis involved the development of descriptive themes, which entailed examining similarities and differences between initial codes in order to identify new (higher level) themes that captured the meaning of groups of codes. Each researcher in the team did this independently prior to group discussions designed to achieve consensus, and to ensure that all initial codes were adequately addressed by identified descriptive themes.

Finally, the third stage of the synthesis was designed to generate analytic themes. This superordinate level of synthesis was achieved by using the descriptive themes that emerged during Stage 2 of the synthesis to derive analytic themes that went beyond the content of reviewed studies to more directly address the review question (that had temporarily been put to one side during earlier stages of synthesis). Identified analytic themes (i.e., risk versus resilience and an eco-systemic framework) were derived from identified descriptive themes and informed by contemporary conceptualizations of stress, coping, and resilience [

2,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]; with these analytic themes being designed to ensure that the research more directly addressed the review question.

This process of data synthesis was iterative in nature, with adaptations, modifications, or additions being made following team discussions during the course of the data synthesis.

2.7. Quality Assessment

The quality of studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Assessment and Review tool (JBI-QARI) [

79], that contains 10-items which focus on the rigour of research design and the quality of reporting. For this review JBI-QARI evaluations were conducted independently by two researchers (S.J.C. and D.R.) with blinded adjudication by a third researcher (S.R.V.) being employed in cases where consensus could not be reached. Studies were generally rated as high quality, with 25 studies meeting 8-10 quality criteria [

11,

22,

46,

49,

50,

51,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

63,

64,

65,

66,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76] and 5 studies meeting 6-7 criteria [

21,

52,

55,

62,

67]. Quality ratings for each study are presented in supplementary data (S5). No studies were excluded based on quality assessment.

3. Results

3.1. Study Descriptions

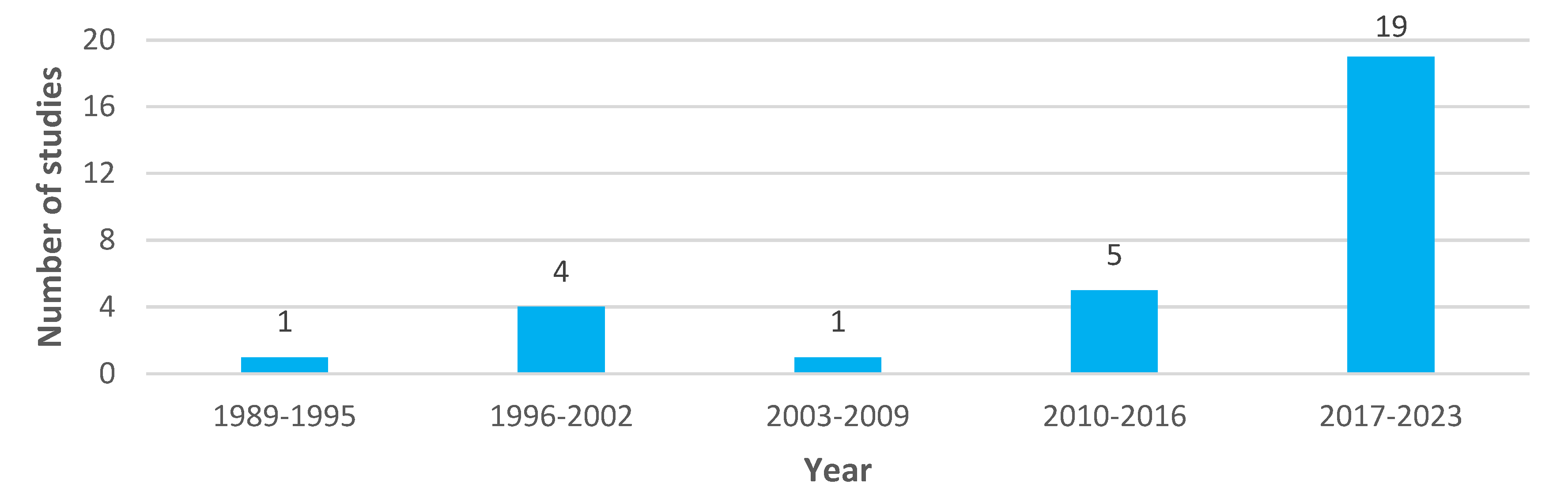

The 30 studies that were included in this review reported on the perceptions of 156 qualitative researchers. Although the review included studies published over a 35-year period (1989 to 2023), a breakdown of studies by publication year (

Figure 2 ) indicates that the majority of studies (63.3%) had been published in the past seven years, providing a largely contemporary perspective on RID.

Researchers’ home discipline was predominantly the social sciences (53.3%) or health sciences ( 36.7%), with the majority of researchers self-identifying as female (71.8%). According to World Bank ratings [

80] , three studies reported on the perceptions of researchers residing in middle-income African countries (South Africa and Tanzania) [

22,

46,

50], with all other studies reporting on the perceptions of researchers residing in high-income countries, and with no studies reporting on the perceptions of researchers’ living in low-income countries. Identified studies were conducted among researchers in four continents – North America (42.9%), Oceania (28.2%), Europe (24,4%), or Africa (4.5%) – with two studies [

46,

72] involving research teams that included researchers from more than one continent. With respect to the researchers’ country of residence, approximately nine out of 10 studies (92.9%) were conducted in one of four countries: the United States (27.6%), Australia, (27.6%), the United Kingdom (22.4%), or Canada (15.4%).

In 13 studies (43.3%) definitions of child maltreatment were restricted to one or more of the four classical types of child maltreatment (physical, sexual, emotional, and/or neglect) [

11,

21,

49,

55,

56,

59,

62,

66,

69,

70,

71,

74,

75], with additional forms of child maltreatment being considered in a number of studies, including: filicide [

50,

51,

60,

72], witnessing domestic violence [

58,

68], child labour [

46], household poverty [

22,

46], intergenerational trauma [

22,

65], unaccompanied child migrants [

73], or the commercial sexual exploitation of children [

67]. In the remaining six studies child maltreatment was (or emerged as) a research focus, without any specific type/s of child maltreatment being specified in the text [

52,

57,

61,

63,

64,

76]. With respect to data sources, information relating to child maltreatment was obtained from face-to-face interviews with: children [

46,

52,

57,

63,

64,

66,

67,

73], caretakers of abused children [

51,

55], adult survivors of child maltreatment [

11,

22,

46,

49,

50,

56,

57,

58,

59,

62,

63,

65,

68,

72,

75], and/or neighbours of maltreated children [

60]. In seven studies no face-to-face interviews were conducted, with researchers obtaining data relating to child maltreatment exclusively through file or archive reviews [

21,

61,

69,

70,

71,

74,

76].

With respect to research methodology, all studies employed convenience sampling and cross-sectional designs, with data reduction strategies taking a number of forms, including: thematic analysis [

11,

21,

52,

55,

62,

64,

67,

72,

73,

76], a process of critical self-reflection [

46,

49,

50,

51,

56,

57,

58,

59,

61,

63,

70,

75], or autoethnographic analysis [

22,

60,

65,

66,

68,

69,

71,

74]. A more detailed summary of study descriptions is provided in supplementary data (S4).

3.2. Data Synthesis

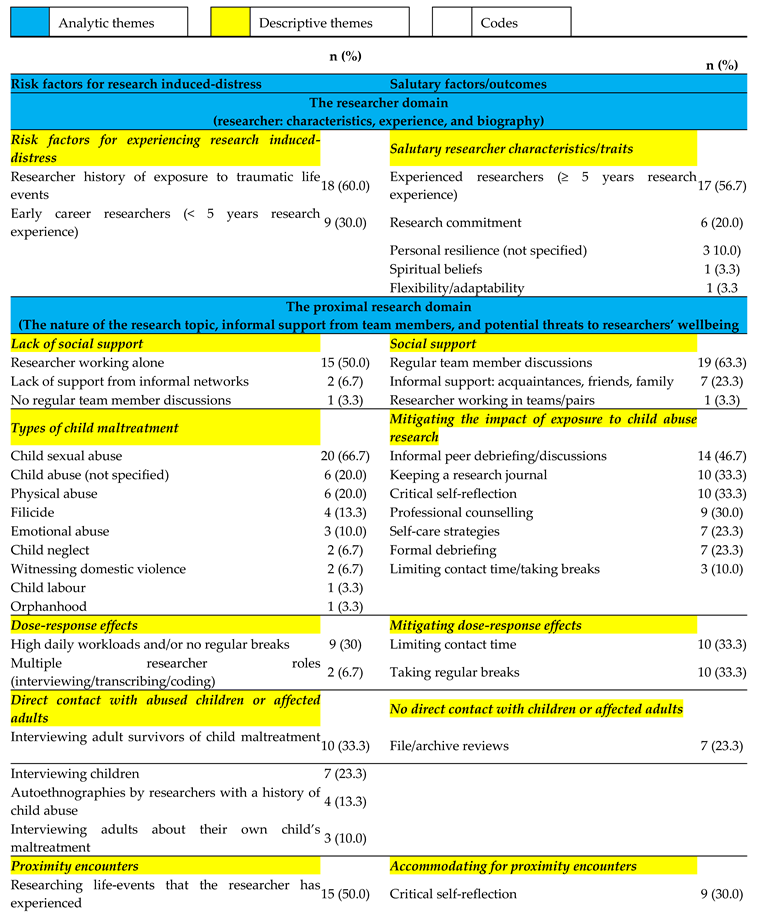

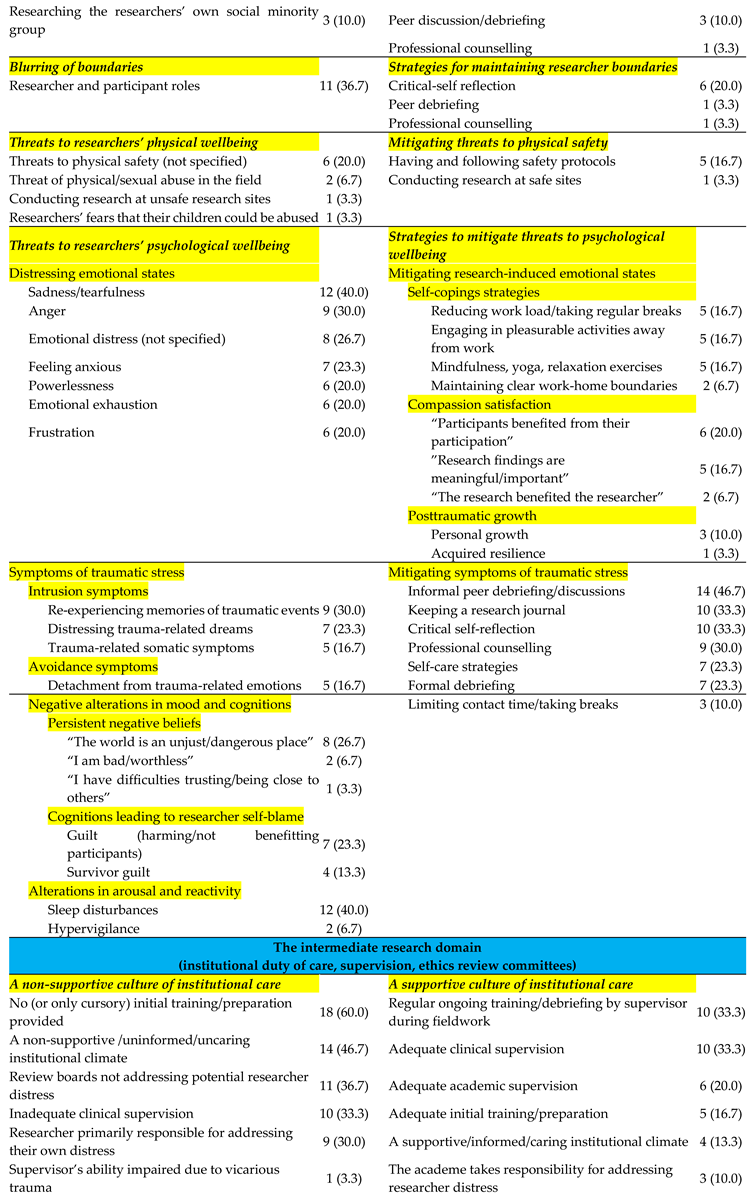

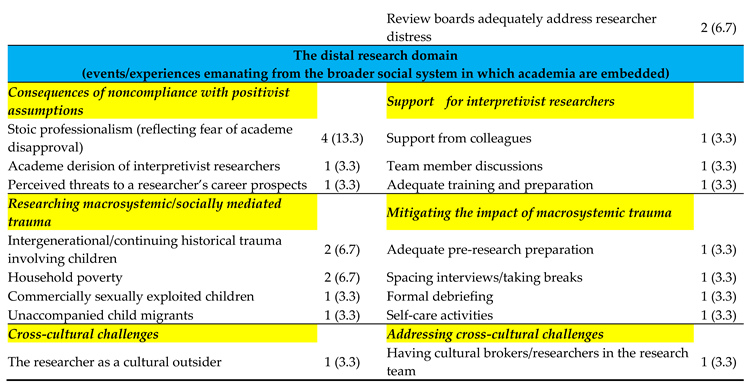

The hierarchical structure that emerged from the data synthesis is presented in

Table 1.

Line-by-line perusal of identified reports identified 115 codes, with these codes being more or less equally divided between risk factors for RID (

n = 58, 50.4%) and salutary influences on RID outcomes (

n = 57, 49.6%). From

Table 1 it is evident that approximately two out of three codes related to events or experiences that occurred in the proximal research domain (

n = 78, 68.4%) that encompasses the nature of the research topic, informal support from team members, and potential threats to researchers’ wellbeing emanating from research engagement. The three most frequently mentioned risk factors for RID were: child sexual abuse as a research focus (

n = 20 reports, 66.7%), researchers’ past experience of exposure to traumatic life events (

n = 18 reports, 60.0%), and researchers’ working alone (

n = 15 reports, 50%); with the three most frequently mentioned salutary influences being regular team member discussions (19 reports, 63.3%), researchers’ having ≥ 5-years research experience (17 records, 56.7%), and informal peer debriefing sessions (14 reports, 46.7%).

A total of 39 descriptive themes emerged from the data synthesis, with these descriptive themes relating to risk factors for RID (21 themes, 53.8%) or salutary influences on RID outcomes (18 themes, 46.2%). Finally, consistent with contemporary conceptualisations of traumatic distress (23-27) and contemporary conceptualisations of RID (2,19,20) , two themes (risk versus resilience, and the influence of different ecosystemic level on RID outcomes) were considered as analytic themes.

An emergent finding from the data synthesis was that some identified codes were characterised by multifinality (i.e., the idea that a single risk or protective factor can lead to multiple outcomes). For example, from

Table 1 it is evident that the protective strategy of seeking professional counselling was regarded by researchers as being an effective strategy for reducing RID associated with engaging in child abuse research, as well as being an effective strategy for addressing symptoms of traumatic distress and of minimizing the impact of proximity encounters and boundary violations.

Finally, although the data synthesis was grounded in researchers’ words and phrases, the voice of researchers was largely silenced in the process of data synthesis. In order to address this concern, the presentation of child abuse researchers’ perceptions of risk and salutary factors for RID draws on insights from the data synthesis (descriptive and analytic themes) , with efforts to enhance the credibility of such insights involving the inclusion of rich and thick verbatim descriptions of participants’ accounts (identified during line-by-line coding) to support conclusions drawn.

3.3. Child Abuse Researchers’ Perceptions of Triggers for RID`

This section explores researchers’ perceptions of triggers for RID, with a more detailed description of researchers experiences – including rich and verbatim accounts of researcher’s perceptions identified during line-by-line coding – being presented in supplementary data (S6).

With respect to levels of the research ecology that emerged in the data synthesis, child abuse researchers’ perceptions of triggers for RID can be considered in relation to triggers relating to: (a) the researcher domain, (b) the proximal research domain, (c) the intermediate/institutional domain, and/or (d) the broader socio-cultural context in which research institutions are embedded.

3.3.1. The Researcher Domain

For many researchers, a personal lack of research experience (<5 years research experience) was perceived to be associated with a greater risk for experiencing RID [

28,

46,

49,

50,

55,

58,

59,

65,

68,

69], with a lack of secure tenure being mentioned as a risk factor for RID by researchers who were employed on a fixed-term or casual basis [73.74].

A lack of preparedness – limited prior research experience and/or inadequate pre-research training - was perceived to pose a risk for RID [

11,

22,

28,

46,

49,

50,

51,

52,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

64,

65,

66,

68,

69,

70,

71,

73,

74], with such outcomes tending to be more likely in cases where the researcher was: an early career researcher (< 5-years research experience) [

28,

49,

50,

55,

58,

59,

65,

68,

69] and/or where the researcher was employed on a fixed-term/casual basis (73,74). However, a number of researchers expressed the view that experienced researchers would also benefit from more adequate training and preparation (52,70,72).

3.3.2. The Proximal Research Domain

Consistent with Coddington and colleagues’ perspective on traumatic contagion [

19,

20], researchers’ perceptions of key triggers for RID encompassed not only forms of traumatic countertransference that occurred as a result of listening to or reading about survivors’ experiences but also reflected “

connections to other and often unrelated traumas in other times and spaces” (p. 68) [

19].

With regard to traumatic countertransference, all 30 reports provided evidence that listening to or reading detailed accounts of children’s abuse experiences had the potential for triggering RID. Further, and consistent with the views of Figley [

81], two reports [

21,

65] highlighted the fact that countertransference reactions of researchers often mirrored traumatic symptoms reported by research participants. In addition to evoking emotional distress, the process of engaging with the experiences of abused children also posed a threat to some researchers sense of safety in their homes and/or raised concerns about the safety of the researcher’s children [

21].

The view that trauma is mobile across place and time [

19,

20] was reflected in the fact that many researchers reported intrusion phenomena in terms of which traumatic memories – either explicit (conscious) or implicit (subconscious) – relating to events that occurred in other places and times were activated or re-activated as a result of engaging with abused children’s stories. Explicit memories of past abuse experiences were reported by two researchers [

49,

65], with one researcher reporting that research engagement evoked explicit memories relating to events that occurred prior to the researcher’s birth (i.e. gross violations of human rights experienced by a parent in the past) [

73]. In addition, there was one researcher who reported that implicit memories of abuse only emerged as explicit memories in the context of research engagement [

59].

3.3.3. The Intermediate/Institutional Research Domain

A number of researchers identified an inadequate duty of care on the part of institutions (ethics review boards, team leaders, supervisors, academic colleagues) as a factor that either triggered or compounded RID outcomes [

17,

46,

50,

52,

55,

56,

57,

60,

61,

62,

69,

71,

74,

76]. In addition, many researchers referred to an absence of adequate pre-research training as a trigger for RID during research engagement [

11,

22,

51,

52,

56,

57,

60,

64,

66,

70,

71,

73,

74].

3.3.4. The Distal Research Domain

An important trigger for RID related to the fact that qualitative/interpretative methods fail to comply with the dictates of dominant positivist perspectives on social science research that emphasize objectivity and emotional detachment. As such, a number of researchers engaged in a process of what Hochschild [

82] refers to as ‘surface acting’, in terms of which researchers’ regulated the public expression of their emotions in order to avoid disapproval from the academe and/or significant others [

69,

71,

73,

74].

Researchers’ comments regarding socio-cultural triggers for RID focused largely on the researchers’ role as a cultural outsider, with a number of researchers suggesting that being a cultural outsider is likely to impact negatively on the researchers’ wellbeing and/or on the research process [

46,

63,

64]. However, one researcher maintained that being a cultural

insider may be associated with an increased risk of exposure to RID during the process of research engagement [

11].

3.4. Researchers’ Perspectives on Salutary Mechanisms Mitigating RID Outcomes

This section explores researchers’ perceptions of salutary factors/mechanisms that mitigated the risk for RID, with a more detailed description of researchers experiences – including rich and verbatim accounts of researcher’s perceptions identified during line-by-line coding – being presented in supplementary data (S7). As was the case for risk factors, salutary mechanisms that were perceived to mitigate RID outcomes were identified at all levels of the researchers’ research ecology.

3.4.1. The Researcher Domain

Discussions of salutary researcher characteristics focused largely on active coping styles (e.g., engaging in self-care activities or employing self-help coping strategies) as a protective factor [

11,

22,

49,

50,

51,

55,

57,

58,

60,

61,

62,

63,

65,

66,

67,

68,

71,

72,

73,

74,

75,

76]. Additionally, some researchers reported resilient traits and characteristics (general resilience, spiritual beliefs, research experience) that served to mitigate RID outcomes [

11,

22,

49,

57,

68,

69,

70,

73].

3.4.2. The Proximal Research Domain

There were a number of researcher’s who felt that the process of research engagement led to the development of personal resilience [

58,

63,

68,

69,

70,

72]. In two studies, an emerging sense of researcher resilience was directly inspired by the resilience of research participants [

58,

63].

3.4.3. The Intermediate/Institutional Research Domain

Researchers perceptions of factors mitigating RID related largely to ongoing training received during the process of search engagement [

45,

51,

57,

58,

60,

61,

62,

67,

69,

70,

71,

75], adequate academic and clinical supervision, [

11,

22,

49,

51,

57,

58,

61,

67,

70,

75,

76], and helpful ethical guidelines provided by members of the academe [

47,

49].

3.4.4. The Distal Research Domain

Efforts to counter the effects of stoic professionalism associated with surface acting involved researchers’ efforts to share their emotional burden in ‘safe’ places (mainly discussions with colleagues and team members) [

69,

71]. With respect to addressing triggers for RID in cross-cultural research, one study employed a number of strategies, including obtaining advice and guidance from local children’s rights experts and ensuring that cultural brokers formed part of the research team [

46].

3.5. Some Emergent Themes and Issues that Emerged During this Review

3.5.1. Geographical Disparities in Research Publications

Although only 16% of the world’s population live in high-income countries (HICs) [

80], 95.5% of studies in this review reported on the perceptions of researchers living in HICs, suggesting a form of sampling bias that amplifies the voices of the privileged few, and largely silences the voices of researchers living in resource scarce regions. Given that key challenges to researchers’ wellbeing have been found to vary as a function of country income levels [

12,

83] there would appear to be a clear need for research efforts designed to directly address and to remedy this form of sampling bias.

3.5.2. Silencing the Lambs

Children’s rights to be heard and to participate in decisions that impact on their lives is enshrined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child [

84]); with such rights encompassing not only that children’s voices be heard in research on matters affecting them but also a need for children to be engaged as collaborators in all phases of the research process [

85,

86,

87].

This ideal of child participation was not realized in most studies reviewed, with only seven studies (23.3%) affording children the right to report on perceptions of their own maltreatment [

46,

52,

57,

63,

64,

66,

67], and only one study making concerted efforts to engage children as collaborators during all phases of the research process [

46]. As such, future research on child abuse-related RID could benefit from more comprehensive efforts designed to amplify the voice of abused children and to more comprehensively incorporate children as collaborators in the research process.

3.5.3. A Matter of Time

Findings from this review confirm that RID is not simply a function of here-and-now influences emanating from the proximal research context but may also be influenced by intrusion phenomena (e.g. traumatic re-experiencing ) that relate to a researcher’s past history of exposure to child maltreatment [

19,

20]. Chronosystemic influences are also suggested by researchers’ perceptions that their RID was related: (a) to intergenerational traumatic experienced by significant others prior to the researcher’s birth (e.g., Nazism or Apartheid) [

22,

73] or (b) to future concerns regarding the safety of researchers and their children [

21]. As Coddington points out, this mobility of traumatic experiences across time and place provides us with an extended definition of influences on RID, that may usefully be considered in future studies [

19].

At another level, chronosystemic influences were evident at different times across the trajectory of research engagement, with some of these influences being most salient prior to research engagement (e.g., adequate/inadequate pre-research preparation and training), and others influences emerging during relatively early stages of research engagement, with still other issues arising from the process of emotional labour that researchers engaged in in order to address unanticipated RID [

82]. As such an adequate culture of care for researchers – involving ongoing competent clinical supervision, frequent formal debriefing or counselling, and ongoing training, and debriefing – would appear to be indicated during all phases of the research process.

4. Discussion

The aim of this research was to explore child abuse researchers’ perceptions of risk and salutary factors that impact on their wellbeing. Consistent with findings from previous studies [

1,

2,

4], the present findings suggest that influences on RID can usefully be considered in relation to a number of different layers of influence with these layers encompassing not only the researcher but also multiple levels of the research ecology in which the researcher is embedded; with responsibility for addressing RID, consequently, also needing to be considered at all levels of the researcher’s social ecology [

2].

The data synthesis produced a contextualised framework that was exhaustive (i.e., all identified triggers for RID were accommodated in the framework), with the heuristic value of the framework being suggested by the fact that factors relevant to RID outcomes were identified in each of the content domains defined by the two analytic themes (levels of the research ecology, and risk versus resilience mechanisms) included in the data synthesis.

It is notable that some identified salutary factors or mechanisms were characterized by multifinality, with certain strategies (e.g., seeking professional counselling) being perceived by researchers as mitigating RID outcomes in relation to risk factors occurring at a number of different levels of the research ecology. This finding is not particularly surprising as levels of the research ecology are not regarded as being distinct, with the outcome of a particular salutary influence being regarded as being shaped by the interactions and coactions of many systems working in concert [

25].

With respect to the dynamics of RID, review findings suggest that researcher wellbeing is not simply a function of influences emanating from different levels of the researchers’ social ecology but may also involves synergies between multisystem risk and protective factors working in concert [

27]. Thus, for example, accounts of intrusion (or re-experiencing) phenomena reported by researchers in this review would clearly appear to involve synergies between factors emanating from the both the researcher domain (a past history of traumatic exposure) and the proximal research domain (researching topics that are particularly salient in terms of the researcher’s biography). As Masten and colleagues [

27] point out, such synergies suggest the need for a multisystemic perspective that not only acknowledges the influence of multisystemic influences on individual’s wellbeing but also addresses synergistic transactions between different eco-systemic levels and/or different risk and protective factors. Although only a few of the studies in this review considered risk and protective factors emanating from more distal systemic influences (cultural and chronosystemic influences), available studies suggest that such distal influences have the potential to exert significant synergistic influences on individuals’ wellbeing [

19,

20,

88,

89,

90], and therefore need to be more comprehensively addressed in future studies of RID.

With respect to the implications of this review for researchers, the review provides child abuse researchers with a broad range of risk and salutary factors that can be used by researchers to prepare them for potential RID and to provide them with strategies that can be used to mitigate RID. Similarly, the findings from this review could usefully be considered by research institutions in their drafting of institutional protocols designed to protect the physical and psychological wellbeing of child abuse researchers.

Finally, it needs to be considered whether risk and protective factors for RID among child abuse researchers are similar to, or different from, factors that have been found to be associated with RID outcomes in the general literature on RID. The answer to this question is quite simply that in the vast majority of cases risk and protective influences identified in this review are similar to influences identified in previous studies, However, some influences appear to be largely unique to child abuse researchers (e.g., researchers increased concerns relating to their child being maltreated or re-experiencing phenomena related specifically to the researchers’ past history of child abuse). Conversely, it is of course possible that risk and salutary influences identified in the general literature on RID may include additional influences that were not identified in this review.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

We believe that this review has a number of strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this review represents the first attempt to explore factors associated with RID among qualitative child abuse researchers, with: (a) the research protocol for the review being registered with PROSPERO prior to the commencement of the review (CRD42024593507 ), (b) searches being conducted using four databases (Scopus, MEDLINE, PsychINFO, and ProQuest) augmented by full-text citation searches of all identified reports and additional searches in key journals), (c) study selection procedures being informed by the updated PRISMA 2020 statement [

77], and (d) the review being guided by the Lippencott-Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for systematic qualitative reviews. [

53].

However, the inclusion criterion that restricted all searches to records published in English may have excluded some potentially relevant studies. Further, the fact that 95.5% of reviewed studies reported on the perceptions of researchers living in high-income countries suggests that study findings may not be generalizable to researchers living in low- or middle-income countries. Finally, given that all authors of this paper are experienced child abuse researchers, it is possible that our own perceptions of researching child abuse may have unintentionally influenced study findings. Although concerted efforts were made by all authors to avoid such bias, we cannot be certain that we were totally successful in these efforts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R.V.; S.J.C., and D.R.; Methodology, S.R.V., S.J.C, and D.R.; Formal analysis, S.R.V., S,J.C., and D.R; Writing – original draft, S.R.V. and S.J.C.; Writing – review & editing, S.R.V. and S.J.C.

Funding

The authors declare that no funding was received for this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Study data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- AbiNader, M.A.; Messing, J.T.; Pizarro, J.; Mazzio, A.K.; Turner, B.G.; Tomlinson, L. Attending to our own trauma: Promoting vicarious resilience and preventing vicarious traumatization among researchers. Soci. Work Res. 2023, 47, 237-249. [CrossRef]

- Baker, S.; Bellemore, P.; Morgan, S. Researching in fragile contexts: Exploring and responding to layered responsibility for researcher care. Women’s Stud. Int. Forum 2023, 98, 102700. [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.M.; Sousa, B.J. The mental Health of people doing qualitative research: Getting serious about risks and remedies. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2018, 17, 1. [CrossRef]

- Dickson-Swift, V. Undertaking qualitative research on trauma: Impacts on researchers and guidelines for risk management. Qual. Res. Org. Manag. 2022, 17, 469-486. [CrossRef]

- MacIver, E.; Adams, N.N.; Torrance, N.; Douglas, F.; Kennedy, C.; Skatun, D.; Hernandez Santiago, V.; Grant, A. Unforeseen emotional labour: A collaborative autoethnography exploring researcher experiences of studying Long COVID in health workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. SSM Qual. Res. Health 2024, 5, 10039. [CrossRef]

- Orr, E.; Durepos, P.; Jones, V.; Jack, S.M. Risk of secondary distress for graduate students conducting qualitative research on sensitive subjects: A scoping review of Canadian dissertations and theses. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 2021, 8, 233339362199380. [CrossRef]

- San Roman Pineda, I.; Lowe, H.; Brown, L.J.; Mannell, J. Viewpoint: Acknowledging trauma in academic research. Gend. Place Cult. 2022, 30, 1184–1192. [CrossRef]

- Jané, S.E.; Fernandez, V.; Hällgren, M. Shit happens. How do we make sense of that? Qual. Res. Org. Manag. 2022, 17, 425-441. [CrossRef]

- Mavin, S. Women leaders’ work-caused trauma: Vulnerability, reflexivity and emotional challenges for the researcher. Qual. Res. Org. Manag. 2022 , 17, 2242. [CrossRef]

- Phenwan, T.; Sixsmith, J.; McSwiggan, L. Methodological reflections on conducting online research with people with dementia: The good, the bad and the ugly. SSM Qual. Res. Health 2023, 4, 100371. [CrossRef]

- Reed, R.M.; Morgan, L.M.; Cowan, R.G.; Birtles, C. Lived experiences of human subjects researchers and vicarious trauma. J. Soc. Behav. Health Sci. 2023, 17, 164–180. [CrossRef]

- Nkosi, B.; Van Nuil, J.I.; Nyirenda, D.; Chi, P.C.; Schneiders, M.L. Labouring on the frontlines of global health research: Mapping challenges experienced by frontline workers in Africa and Asia. Glob. Public Health 2022, 17, 4195–4205. [CrossRef]

- Hennessy, M.; Dennehy, R.; Doherty, J.; O'Donoghue, K. Outsourcing transcription: Extending ethical considerations in qualitative research. Qual. Health Res. 2022, 32, 1197–1204. [CrossRef]

- Lalor, J.G.; Begley, C.M; Devane, D. Exploring painful experiences: Impact of emotional narratives on members of a qualitative research team. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 56, 607–616. [CrossRef]

- Whitt-Woosley, A.; Sprang, G. Secondary traumatic stress in social science researchers of trauma-exposed populations. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 2018, 27, 475-486. [CrossRef]

- Brougham, P.L.; Uttley, C.M. Risk for researchers studying social deviance or criminal behavior. Soc. Sci. 2017, 6, 130. [CrossRef]

- Fried, A.L.; Fisher, C.B. Moral stress and job burnout among frontline staff conducting clinical research on affective and anxiety disorders. Prof. Psychol. Res. Pr. 2016, 47, 171–180. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, K.H.; Devine, K. Doctoral students’ emotional exhaustion and intentions to leave academia. IJDS 2016, 11, 35-61. http://ijds.org/Volume11/IJDSv11p035-061Hunter2198.pdf.

- Coddington, K. Contagious trauma: Reframing the spatial mobility of trauma within advocacy work. Emotion Space Society 2017, 24, 66-73. [CrossRef]

- Coddington, K.; Micieli-Voutsinas, J. On trauma, geography, and mobility: Towards geographies of trauma. Emotion Space Society 2017, 24, 52-56. [CrossRef]

- Alexander, J.G.; de Chesnay, M.; Marshall, E.; Campbell, A.R.; Johnson, S.; Wright, R. Research note: Parallel reactions in rape victims and rape researchers. Violence Vict. 1989, 4, 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Adonis, C.K. Bearing witness to suffering – A reflection on the personal impact of conducting research with children and grandchildren of victims of Apartheid-era gross human rights violations in South Africa. Soc. Epistemol. 2020, 34, 64-78. [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Stress, Culture, and Community. New York: Plenum Press, 1998.

- Hobfoll, S.E. The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S.; Lucke, C.M.; Nelson, K.M.; Stallworthy, I.C. Resilience in development and psychopathology: Multisystem perspectives. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 17. [CrossRef]

- Theron, L.; Ungar, M.; Höltge, J. Pathways of resilience: Predicting school management trajectories for South African adolescents living in a stressed environment. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2022, 69, 102062. [CrossRef]

- Ungar, M.; Theron, L.; Murphy, K.; Jeffries, P. Researching multisystemic resilience: A sample methodology. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 3808. [CrossRef]

- Dajani, M.A.; Nyerges, E.X.; Kacmar, A.M.; Gunathilake, W.A.P.M.; Harris, L.M. “Just a voice” or “a person, too?”: Exploring the roles and emotional responses of spoken language interpreters. USW 2023, USW-2023-0009.R1. [CrossRef]

- Flannery, E.; Peters, K.; Murphy, G.; Halcomb, E.; Ramjan, L.M. Bringing trauma home: Reflections on interviewing survivors of trauma while working from home. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2023, 22, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Pittens, C.; Dhont, J.; Petit, S.; Dubois, L.; Franco, P.; Mullaney, L.; Aznar, M.; Petit-Steeghs, V.; Bertholet, J. An impact model to understand and improve work-life balance in early-career researchers in radiation oncology. ctRO 2022, 37, 101–108. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, N. Doing research in peoples’ homes: Fieldwork, ethics and safety – on the practical challenges of researching and representing life on the margins. Qual. Res. 2018, 18, 638-653. [CrossRef]

- Woods, S.; Chambers, T.N.G.; Eizadirad, A. Emotional vulnerability in researchers conducting trauma-triggering research. J. High. Educ. Policy Leadersh. Stud. 2022, 3, 71-88. [CrossRef]

- Astill, S. The importance of supervisory and organisational awareness of the risks for an early career natural hazard researcher with personal past-disaster experience. Emotion Space Society 2018, 28, 46-52. [CrossRef]

- Dickson-Swift, V.; James, E.L.; Kippen, S. Do university ethics committees adequately protect public health researchers? ANZJPH 2005, 29(6), 576-579. [CrossRef]

- Gelling, L. Role of the research ethics committee. Nurse Educ. Today 1999, 19(7), 564-569. [CrossRef]

- Bracken-Roche, D.; Bell, E.; Macdonald, M.E.; Racine, E. The concept of ‘vulnerability’ in research ethics: An in-depth analysis of policies and guidelines. Health Res. Policy Sys. 2017, 15, 8. [CrossRef]

- Drozdzewski, D. Retrospective reflexivity: The residual and subliminal repercussions of researching war. Emotion Space Society 2015, 17, 30-36. [CrossRef]

- Humphries, N.; Byrne, J-P.; Creese, J.; McKee, L. ‘Today was probably one of the most challenging workdays I’ve ever had’: Doing remote qualitative research with hospital doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Qual. Health Res. 2022, 32, 1557-1573. [CrossRef]

- Newcomb, M. The emotional labour of academia in the time of a pandemic: A feminist reflection. QSW 2021, 20, 639–644. [CrossRef]

- Rogers-Shaw, C.; Choi, J; Carr-Chellman, D. Understanding and managing the emotional labor of qualitative research. Forum qual. Soz. forsch. 2021, 22, 22. [CrossRef]

- Herland, M.D. Emotional intelligence as a part of critical reflection in social work practice and research. Qual. Soc. Work 2022, 21, 662-678. [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, A. The better to break and bleed with: Research, violence, and trauma. Geopolit. 2021, 26, 94-117. [CrossRef]

- 43 Shannonhouse, L.; Barden, S.; Jones, E.C.; Gonzalez, L.; Murphy, A.D. Secondary traumatic stress for trauma researchers: A mixed methods research design. J. Ment. Health Couns. 2017, 38, 201-216. [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.; Pooley. J-A.; Holmes, L.; Gebbie, K.; Gershon, R. Vicarious trauma: Exploring the experiences of qualitative researchers who study traumatized populations. DMPHP 2021, 17, e6. [CrossRef]

- Velardo, S.; Elliott, S. The emotional wellbeing of doctoral students conducting qualitative research with vulnerable populations. TQR 2021, 26, 1522-1545. [CrossRef]

- Klocker, N. Participatory action research: The distress of (not) making a difference. Emotion Space Society 2015, 17, 37-44. [CrossRef]

- Dickson-Swift, V.; James, B. L.; Kippen, S.; Liamputtong, P. Researching sensitive topics: Qualitative research as emotion work. Qual. Res. 2009, 9, 61–79. [CrossRef]

- Harris, J.; Huntington, A. Emotions as analytic tools: Qualitative research, feelings, and psychotherapeutic insight. In The Emotional Nature of Qualitative Research; Gilbert, K., Ed; CRC: London, 2001; pp.129-145.

- Moran, R.J.; Asquith, N.L. Understanding the vicarious trauma and emotional labour of criminological research. Innovations 2020, 13. [CrossRef]

- Qhogwana, S. Research trauma in incarcerated spaces: Listening to incarcerated women's narratives. Emotion Space Society 2022, 42, 100865. [CrossRef]

- Silverio, S.A.; Sheen, K.S.; Bramante, A.; Knighting, K.; Koops, T.U.; Montgomery, E.; November, L.; Soulsby, L.K.; Stevenson, J.H.; Watkins, M.; Easter, A.; Sandall, J. Sensitive, challenging, and difficult topics: Experiences and practical considerations for qualitative researchers. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2022, 21, 16094069221124739. [CrossRef]

- Milling Kinard E. Conducting research on child maltreatment: Effects on researchers. Violence Vict. 1996, 11, 65–69. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A.; Robertson-Malt, S.; Rittenmeyer, L. Synthesizing qualitative evidence. Synthesis Science in Healthcare Series: Book 2, Lippincott-Joanna Briggs Institute, 2011. Available at: https://nursing.lsuhsc.edu/JBI/docs/JBIBooks/Syn_Qual_Evidence.pdf (accessed: 30 August 2024).

- Bramer, W.M.; Giustini, D.; de Jonge G.B.; Holland L.; Bekhuis, T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2016, 104, 240-243. [CrossRef]

- Skinner, J. Research as a counselling activity? A discussion of some uses of counselling within the context of research on sensitive issues. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 1998, 26, 533-540. [CrossRef]

- Etherington, K. The counsellor as researcher: Boundary issues and critical dilemmas. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 1996, 24, 339–346. [CrossRef]

- Coles, J.; Mudaly, N. Staying safe: Strategies for qualitative child abuse researchers. Child Abuse Rev. 2010, 19, 56–69. [CrossRef]

- Scerri, C.S.; Abela, A.; Vetere, A. Ethical dilemmas of a clinician/researcher interviewing women who have grown up in a family where there was domestic violence. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2012, 11, 102-131. [CrossRef]

- Stoler, L.R. Researching childhood sexual abuse: Anticipating effects on the researcher. FEM PSYCHOL 2002, 12, 269–274. [CrossRef]

- Connolly, K.; Reilly, R.C. ( 2007). Emergent issues when researching trauma: A confessional tale. Qual. Inq. 2007, 13, 522-540. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.; Backett-Milburn, K.; Newall, E. Researching distressing topics: Emotional reflexivity and emotional labor in the secondary analysis of children and young people’s narratives of abuse. SAGE Open 2013, 3, 2158244013490705. [CrossRef]

- Wilkes, L.; Cummings, J.; Haigh, C. Transcriptionist saturation: Knowing too much about sensitive health and social data. J. Adv. Nurs. 2015, 71, 295–303. [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, L.; James, H.; Cronin-Davis, J.; Tizro Kolangarani, Z.; Beetham, T.; Hullock, A.; Raynar, A. Reflexive research with mothers and children victims of domestic violence. Couns. Psychother. Res. 2017, 17, 157-165. [CrossRef]

- Powell, M.B.; Manger, B.; Dion, J.; Sharman, S.J. Professionals’ perspectives about the challenges of using interpreters in child sexual abuse interviews. Psychiatry Psychol. Law 2017, 24, 90–101. [CrossRef]

- Shah, R. Broken mirror: The intertwining of therapist and client stories of childhood sexual abuse (CSA). EJPC 2017, 19, 343-356. [CrossRef]

- Nikischer, A. Vicarious trauma inside the academe: Understanding the impact of teaching, researching and writing violence. High. Educ. 2019, 77, 905–916. [CrossRef]

- Rothman, E.F.; Farrell, A.; Bright, K.; Paruk, J. Ethical and practical considerations for collecting research-related data from commercially sexually exploited children. Behav. Med. 2018, 44, 250–258. [CrossRef]

- Abraham, A. Surviving domestic violence in an Indian-Australian household: An autoethnography of resilience. TQR 2018, 23, 2686-2699. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol23/iss11/6.

- Guerzoni, M.A. Vicarious trauma and emotional labour in researching child sexual abuse and child protection: A postdoctoral reflection. University of Tasmania. MIO 2020, 13, 205979912092634. [CrossRef]

- Michell, D.E. Recovering from doing research as a survivor-researcher. Qual. Rep. 2020, 25, 1377-1392. [CrossRef]

- Williamson, E.; Gregory, A.; Abrahams, H.; Aghtaie, N.; Walker, S.J; Hester, M. Secondary trauma: Emotional safety in sensitive research. J. Acad. Ethics 2020, 18, 55–70. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, P.; Dawson, M.; Price, J.; Rowlands, J. Intersectionality and invisible victims: Reflections on data challenges and vicarious trauma in femicide: Family and intimate partner homicide research. JOFV 2021, 36, 619–628. [CrossRef]

- Sultanić, I. Interpreting traumatic narratives of unaccompanied child migrants in the United States: Effects, challenges and strategies. LANS-TTS 2021, 20, 227–247. [CrossRef]

- Gleeson, J. Troubling/trouble in the academy: Posttraumatic stress disorder and sexual abuse research. High. Educ. 2022, 84, 195–209. [CrossRef]

- Alyce, S.; Taggart, D.; Sweeney, A. Centring the voices of survivors of child sexual abuse in research: an act of hermeneutic justice. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1178141. [CrossRef]

- Regehr, C.; Duff, W.; Aton, H.; Sato, C. Grief and trauma in the archives. J. Loss Trauma 2023, 28, 327-347. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J.M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M.M.; Li, T.; Loder, E.W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S…Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, J.; Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 45. [CrossRef]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools. 2017. Available at: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed 09 September 2024).

- Hamad, N.; Van Rompaey, C.; Metreau, E.; Eapen, S.G. New World Bank Country Classifications by Income Level: 2022-2023. 2022. Available at: https://blogs.worldbank.org/en/opendata/new-world-bank-country-classifications-income-level-2022-2023 (accessed 30 August 2024).

- Figley, C.R. Compassion Fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self-care. J. Clin. Psychol. 2002, 58, 1433-1441. [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, A. The Managed Heart: Commercialisation of Human Feeling. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012.

- Conradie, A.; Duys, R.; Forget, P.; Biccard, B.M. Barriers to clinical research: A quantitative and qualitative survey of clinical researchers in 27 African countries’, Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 121, 813–821. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Geneva, Switzerland: UN Office of High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR), 1989. Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Kellett, M. Rethinking Children and Research: Attitudes in Contemporary Society. London: Continuum, 2010.

- Mayne, F.; Howitt, C. (2019) Embedding young children’s participation rights into research: How the interactive narrative approach enhances meaningful participation. IJEC 2019, 51, 335–353. [CrossRef]

- Theobald, M.; Danby, S.; Ailwood, J. Child participation in the early years: Challenges for education. AJEC 2011, 36, 19-26. [CrossRef]

- Kirmayer, L.J.; Dandeneau, S.; Marshall, E.; Phillips, M.K.; Williamson, K.J. Rethinking resilience from indigenous perspectives. Can. J. Psychiat. 2011, 56, 84–91. [CrossRef]

- Masten, A.S. Ordinary Magic: Resilience in Development. New York: Guilford, 2014.

- Ungar, M.; Theron, L. 2020. Resilience and mental health: How multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. The Lancet 2020, 7, 441–48. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).