Submitted:

28 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

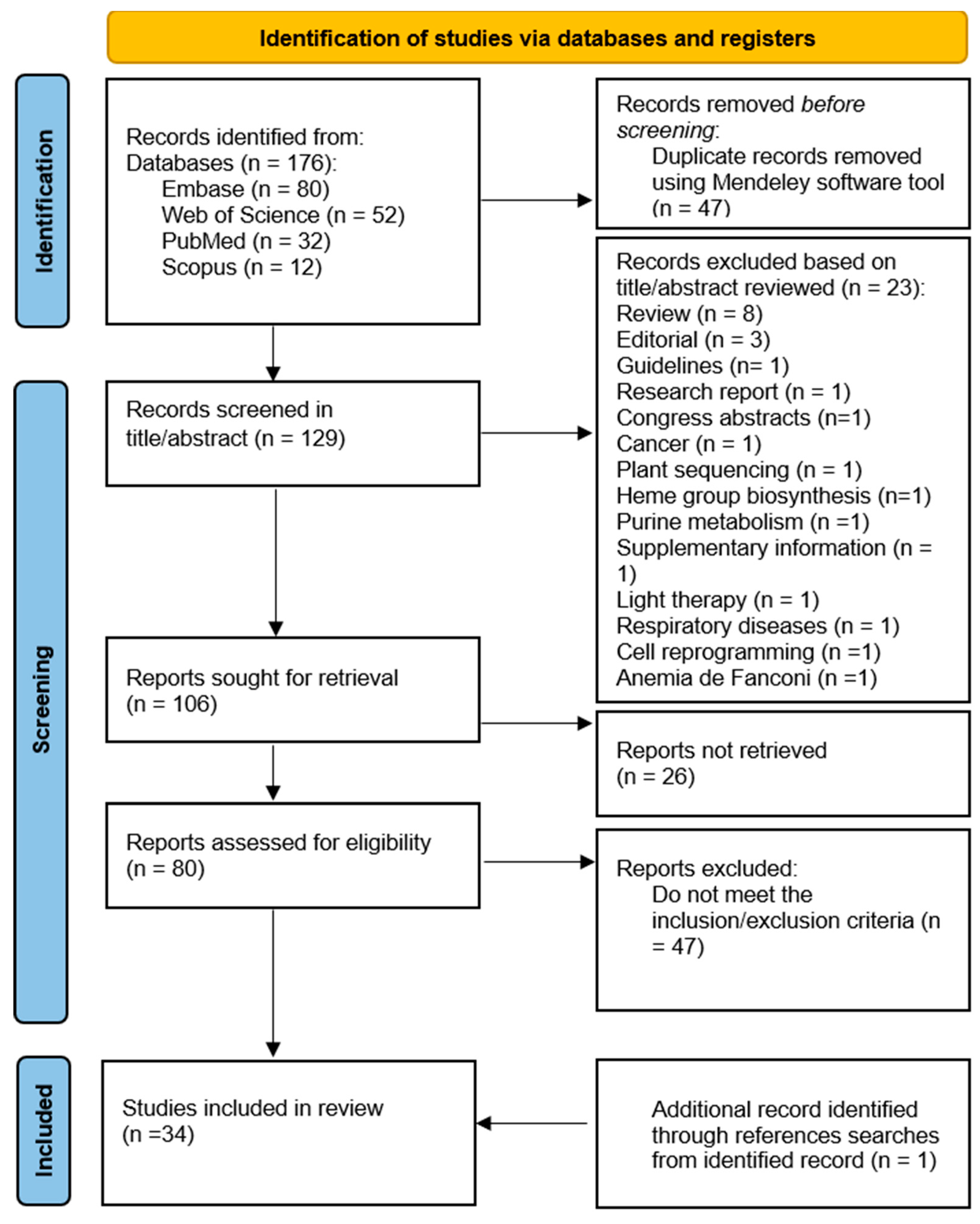

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Search and selection of elegible studies

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Molecules as potential regulators of mitochondial metabolism for treating neurodegenerative diseases

3.2. Methological Quality Assessment

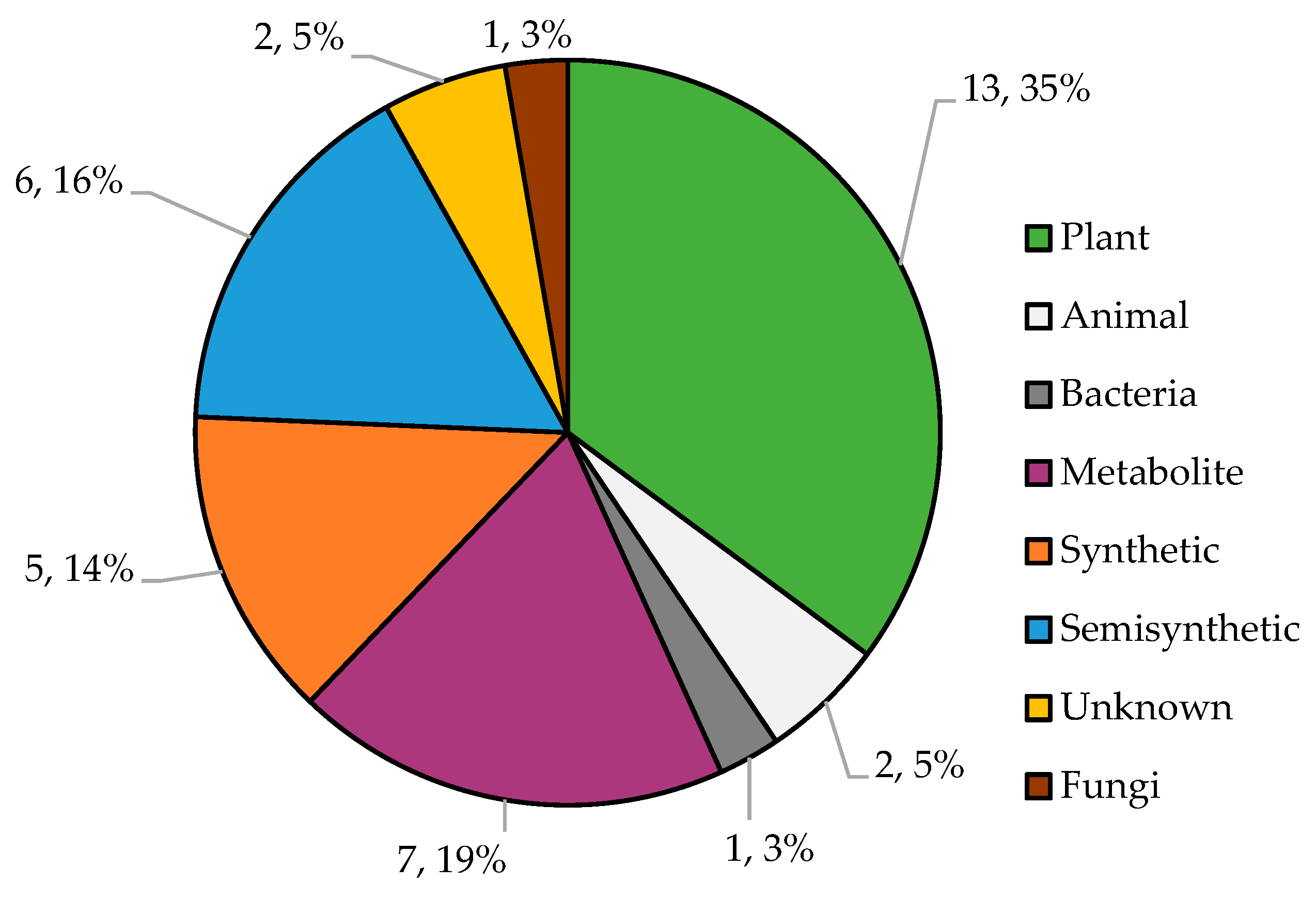

3.3. Analysis of Potential Mitochondrial Regulator Characteristics

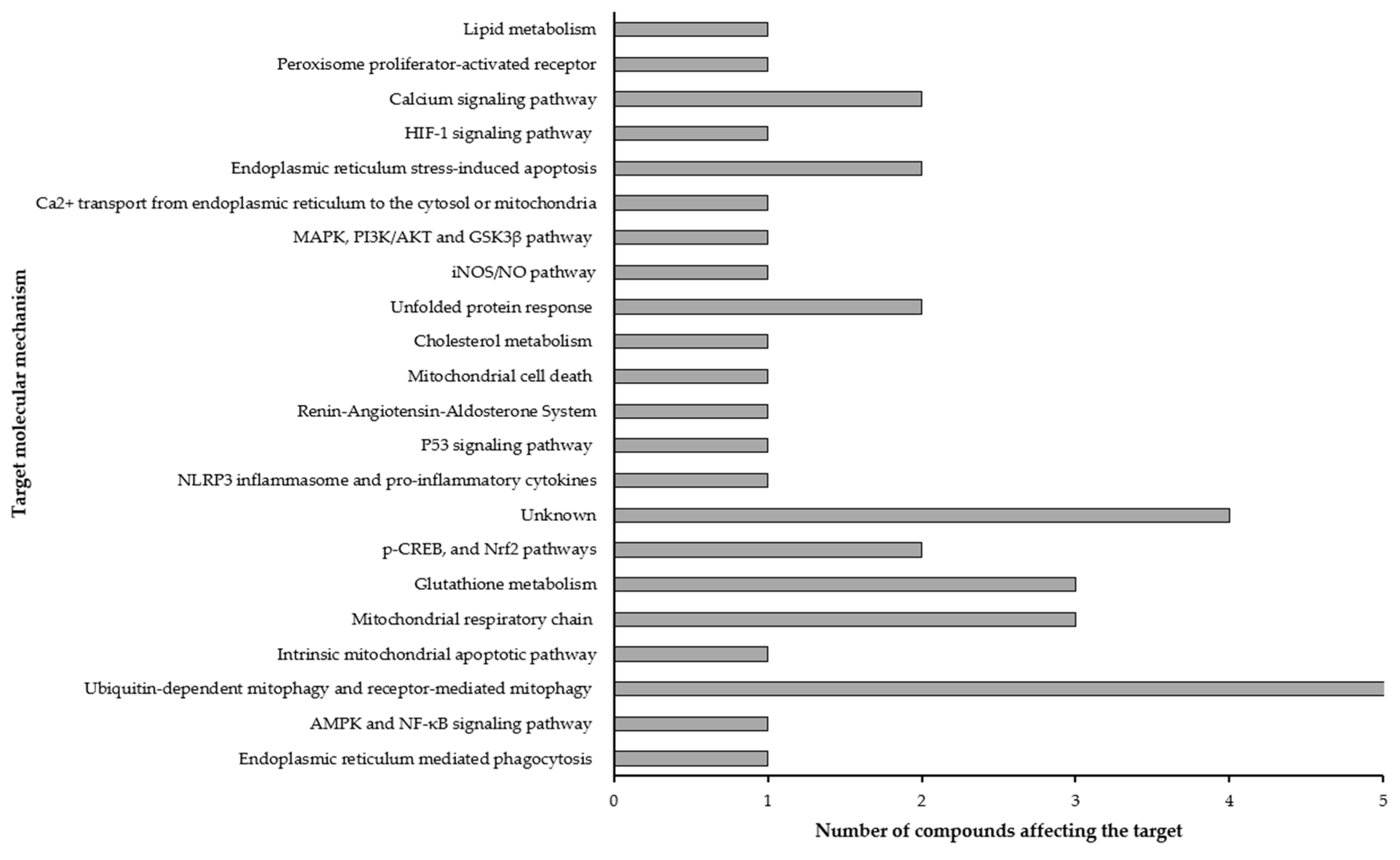

3.4. Mitochondrial Regulation Mechanisms Analysis

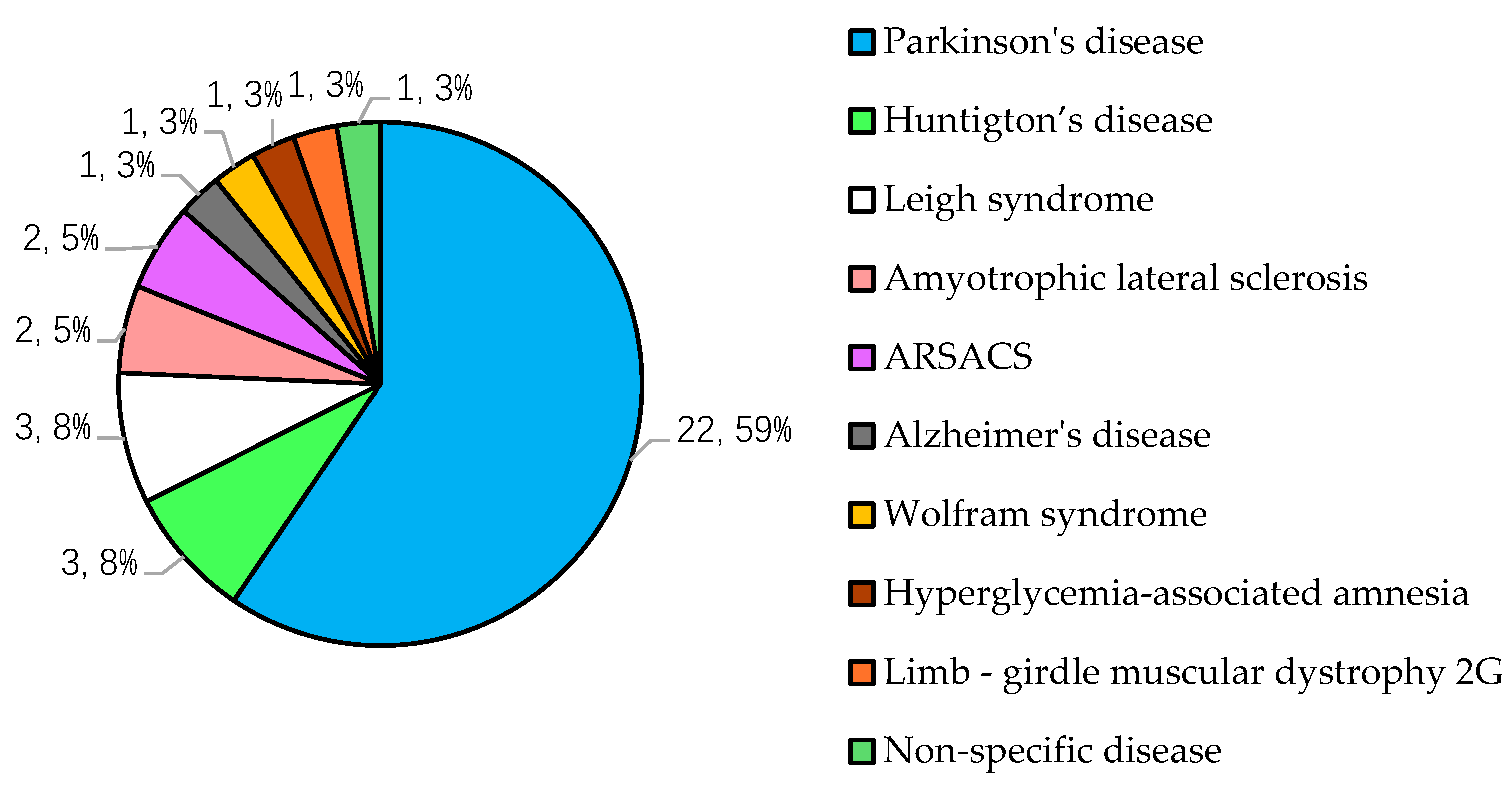

3.5. Analysis of the Neurodegenerative Disease Models.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu-Wai-Man, P.; Griffiths, P.G.; Chinnery, P.F. Mitochondrial optic neuropathies—Disease mechanisms and therapeutic strategies. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2011, 30, 81–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quelle-Regaldie, A.; Sobrido-Cameán, D.; Barreiro-Iglesias, A.; Sobrido, M.J.; Sánchez, L. Zebrafish Models of Autosomal Recessive Ataxias. Cells 2021, 10, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tayran, H.; Yilmaz, E.; Bhattarai, P.; Min, Y.; Wang, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, N.; Jeong, I.; Nelson, N.; Kassara, N.; et al. ABCA7-dependent induction of neuropeptide Y is required for synaptic resilience in Alzheimer’s disease through BDNF/NGFR signaling. Cell Genom. 2024, 4, 100642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuschl, K.; Meyer, E.; Valdivia, L.E.; Zhao, N.; Dadswell, C.; Abdul-Sada, A.; Hung, C.Y.; Simpson, M.A.; Chong, W.K.; Jacques, T.S.; et al. Mutations in SLC39A14 disrupt manganese homeostasis and cause childhood-onset parkinsonism–dystonia. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: Elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2016, 354. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; A Shoemaker, B.; A Thiessen, P.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D1373–D1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Zhou, G.; Hui, F.; Xu, L.; Viau, C.; Spigelman, A.F.; E MacDonald, P.; Wishart, D.S.; Li, S.; et al. MetaboAnalyst 6.0: Towards a unified platform for metabolomics data processing, analysis and interpretation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, W398–W406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M.; Furumichi, M.; Sato, Y.; Kawashima, M.; Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 51, D587–D592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 2019, 28, 1947–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000, 28, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokina, M.; Merseburger, P.; Rajan, K.; Yirik, M.A.; Steinbeck, C. COCONUT online: Collection of Open Natural Products database. J. Cheminform. 2021, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendeley | Free reference manager | Elsevier. Available online: https://www.elsevier.com/products/mendeley (accessed on 26 November 2024).

- Koh, H.; Chung, J. PINK1 as a Molecular Checkpoint in the Maintenance of Mitochondrial Function and Integrity. Mol. Cells 2012, 34, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naef, V.; Marchese, M.; Ogi, A.; Fichi, G.; Galatolo, D.; Licitra, R.; Doccini, S.; Verri, T.; Argenton, F.; Morani, F.; et al. Efficient Neuroprotective Rescue of Sacsin-Related Disease Phenotypes in Zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-Q.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, S.-Q.; Shi, Y.-Y.; Jiang, X.-L.; Wu, S.-S.; Zhou, P.; Wang, H.-Y.; Li, P.; Li, F. An Inhibitor of NF-κB and an Agonist of AMPK: Network Prediction and Multi-Omics Integration to Derive Signaling Pathways for Acteoside Against Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 652310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haridevamuthu, B.; Nayak, S.R.R.; Murugan, R.; Pachaiappan, R.; Ayub, R.; Aljawdah, H.M.; Arokiyaraj, S.; Guru, A.; Arockiaraj, J. Prophylactic effects of apigenin against hyperglycemia-associated amnesia via activation of the Nrf2/ARE pathway in zebrafish. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 976, 176680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Sheng, W.; Tan, Z.; Ren, Q.; Wang, R.; Stoika, R.; Liu, X.; Liu, K.; Shang, X.; Jin, M. Treatment of Parkinson's disease in Zebrafish model with a berberine derivative capable of crossing blood brain barrier, targeting mitochondria, and convenient for bioimaging experiments. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 249, 109151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, C.-M.; Ma, D.; Zhao, C.; Franklin, R.J.; Zhou, Z.-Y.; Ai, N.; Li, C.; Yu, H.; Hou, T.; Sa, F.; et al. Discovery of a novel neuroprotectant, BHDPC, that protects against MPP+/MPTP-induced neuronal death in multiple experimental models. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 1057–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nellore, J.; Pauline, C.; Amarnath, K. Bacopa monnieriPhytochemicals Mediated Synthesis of Platinum Nanoparticles and Its Neurorescue Effect on 1-Methyl 4-Phenyl 1,2,3,6 Tetrahydropyridine-Induced Experimental Parkinsonism in Zebrafish. J. Neurodegener. Dis. 2013, 2013, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.J.; Cho, S.H.; Seo, Y.; Kim, S.-D.; Park, H.-C.; Kim, B.-J. Neuro-Restorative Effect of Nimodipine and Calcitriol in 1-Methyl 4-Phenyl 1,2,3,6 Tetrahydropyridine-Induced Zebrafish Parkinson’s Disease Model. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2024, 67, 510–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Hernandez, I.; Koyuncu, S.; Kis, B.; Häggblad, M.; Lidemalm, L.; Abbas, A.A.; Bendegúz, S.; Göblös, A.; Brautigam, L.; et al. The anti-leprosy drug clofazimine reduces polyQ toxicity through activation of PPARγ. EBioMedicine 2024, 103, 105124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiprich MT, Vasques R da R, Zaluski AB, et al. 3-Nitropropionic acid induces histological and behavioral alterations in adult zebrafish: role of antioxidants on behavioral dysfunction. Published online May 2, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Haroon, S.; Yoon, H.; Seiler, C.; Osei-Frimpong, B.; He, J.; Nair, R.M.; Mathew, N.D.; Burg, L.; Kose, M.; Venkata, C.R.M.; et al. N-acetylcysteine and cysteamine bitartrate prevent azide-induced neuromuscular decompensation by restoring glutathione balance in two novel surf1 −/− zebrafish deletion models of Leigh syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2023, 32, 1988–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, C.-W.; Hung, H.-C.; Huang, S.-Y.; Chen, C.-H.; Chen, Y.-R.; Chen, C.-Y.; Yang, S.-N.; Wang, H.-M.D.; Sung, P.-J.; Sheu, J.-H.; et al. Neuroprotective Effect of the Marine-Derived Compound 11-Dehydrosinulariolide through DJ-1-Related Pathway in In Vitro and In Vivo Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Mar. Drugs 2016, 14, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, A.; Monteiro, S.M.; Venâncio, C.; Félix, L. Protective effects of 24-epibrassinolide against the 6-OHDA zebrafish model of Parkinson's disease. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2023, 269, 109630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, M.; Jiang, H.-Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Yin, X.; Wang, S.-Y.; Qi, Y.; Wang, X.-D.; Feng, H.-L. Guanabenz delays the onset of disease symptoms, extends lifespan, improves motor performance and attenuates motor neuron loss in the SOD1 G93A mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neuroscience 2014, 277, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, A.; Patten, S.A.; Aggad, D.; Julien, C.; Maios, C.; Kabashi, E.; Drapeau, P.; Parker, J.A. Pharmacological reduction of ER stress protects against TDP-43 neuronal toxicity in vivo. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 55, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.-L.; Cheng, Y.-C.; Yeh, T.-H.; Liu, H.-F.; Weng, Y.-H.; Chen, R.-S.; Lu, J.-C.; Hwang, T.-L.; Wei, K.-C.; Liu, Y.-C.; et al. HCH6-1, an antagonist of formyl peptide receptor-1, exerts anti-neuroinflammatory and neuroprotective effects in cellular and animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2023, 212, 115524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesh, S.; Kannan, R.R.; Sivaji, K.; Balakrishnan, A. Hesperidin downregulates kinases lrrk2 and gsk3β in a 6-OHDA induced Parkinson’s disease model. Neurosci Lett. 2020, 740, 135426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.; Zhang, R.; Xu, L.; Wang, G.; Yan, C.; Lin, P. Tcap Deficiency in Zebrafish Leads to ROS Production and Mitophagy, and Idebenone Improves its Phenotypes. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 836464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vijayanand, M.; Issac, P.K.; Velayutham, M.; Shaik, M.R.; Hussain, S.A.; Guru, A. Exploring the neuroprotective potential of KC14 peptide from Cyprinus carpio against oxidative stress-induced neurodegeneration by regulating antioxidant mechanism. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, F.; Zhang, M.; Wang, P.; Dai, Z.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Jing, L.; Qi, C.; Fan, H.; Qin, M.; et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals the anti-Parkinson's activity of Mangiferin in zebrafish. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2024, 179, 117387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, M.-Z.; Li, H.-X.; Dai, X.-Q.; Wang, X.-B.; Liu, J.-Y.; Shen, Y.; Xu, X.; Zhong, Z.-M.; Wang, H.; Liu, C.-F.; et al. Melatonin Ameliorates Abnormal Sleep-Wake Behavior via Facilitating Lipid Metabolism in a Zebrafish Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Neurosci. Bull. 2024, 40, 1901–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, B.R.; Reis, S.D.; Guedes-Dias, P.; Leitão-Rocha, A.; Quintas, C.; Valentão, P.; Andrade, P.B.; Santos, M.M.; Oliveira, J.M. Pharmacological modulation of HDAC1 and HDAC6 in vivo in a zebrafish model: Therapeutic implications for Parkinson’s disease. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 103, 328–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesh, S.; Kannan, R.R.; Balakrishnan, A. Naringenin alleviates 6-hydroxydopamine induced Parkinsonism in SHSY5Y cells and zebrafish model. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2021, 239, 108893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, C.-H.; Liu, Z.; Chen, S.; Lin, F.; Berneshawi, A.R.; Yu, C.Q.; Koo, E.B.; Kowal, T.J.; Ning, K.; Hu, Y.; et al. Primary cilia formation requires the Leigh syndrome–associated mitochondrial protein NDUFAF2. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanese, C.; Tapias, V.; Gabriels, S.; Cerri, S.; Levandis, G.; Blandini, F.; Tresini, M.; Shiva, S.; Greenamyre, J.T.; Gladwin, M.T.; et al. Mitochondrial Complex I Reversible S-Nitrosation Improves Bioenergetics and Is Protective in Parkinson's Disease. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2018, 28, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, G.-H.J.; Mo, H.; Liu, H.; Wu, Z.; Chen, S.; Zheng, J.; Zhao, X.; Nucum, D.; Shortland, J.; Peng, L.; et al. A zebrafish screen reveals Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors as neuroprotective via mitochondrial restoration in dopamine neurons. eLife 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.-L.; Lin, Y.-H.; Wu, Q.; Su, F.-J.; Ye, C.-H.; Shi, L.; He, B.-X.; Huang, F.-W.; Pei, Z.; Yao, X.-L. Paeonolum protects against MPP+-induced neurotoxicity in zebrafish and PC12 cells. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2015, 15, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moskal, N.; Visanji, N.P.; Gorbenko, O.; Narasimhan, V.; Tyrrell, H.; Nash, J.; Lewis, P.N.; McQuibban, G.A. An AI-guided screen identifies probucol as an enhancer of mitophagy through modulation of lipid droplets. PLOS Biol. 2023, 21, e3001977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, N.J.; Davies, N.O.; Lovett, J.E.; Miller, M.R.; Cook, G.; Becker, T.; Becker, C.G.; McPhail, D.B.; Kunath, T. A synthetic cell permeable antioxidant protects neurons against acute oxidative stress. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee; Zhang, Z.J.; Cheang, L.C.V.; Wang, M.W.; Lee, S.M.-Y. Quercetin exerts a neuroprotective effect through inhibition of the iNOS/NO system and pro-inflammation gene expression in PC12 cells and in zebrafish. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2011, 27, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.Q.; Sa, F.; Chong, C.M.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Z.Y.; Chang, R.C.C.; Chan, S.W.; Hoi, P.M.; Lee, S.M.Y. Schisantherin A protects against 6-OHDA-induced dopaminergic neuron damage in zebrafish and cytotoxicity in SH-SY5Y cells through the ROS/NO and AKT/GSK3β pathways. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 170, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouzier, L.; Danese, A.; Yasui, Y.; Richard, E.M.; Liévens, J.-C.; Patergnani, S.; Couly, S.; Diez, C.; Denus, M.; Cubedo, N.; et al. Activation of the sigma-1 receptor chaperone alleviates symptoms of Wolfram syndrome in preclinical models. Sci. Transl. Med. 2022, 14, eabh3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaytow, H.; Carroll, E.; Gordon, D.; Huang, Y.-T.; van der Hoorn, D.; Smith, H.L.; Becker, T.; Becker, C.G.; Faller, K.M.E.; Talbot, K.; et al. Targeting phosphoglycerate kinase 1 with terazosin improves motor neuron phenotypes in multiple models of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. EBioMedicine 2022, 83, 104202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, W.-J.; Liang, L.; Pan, M.-H.; Lu, D.-H.; Wang, T.-M.; Li, S.-B.; Zhong, H.-B.; Yang, X.-J.; Cheng, Y.; Liu, B.; et al. Theacrine, a purine alkaloid from kucha, protects against Parkinson's disease through SIRT3 activation. Phytomedicine 2020, 77, 153281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Nguyen, D.T.; Olzomer, E.M.; Poon, G.P.; Cole, N.J.; Puvanendran, A.; Phillips, B.R.; Hesselson, D. Rescue of Pink1 Deficiency by Stress-Dependent Activation of Autophagy. Cell Chem. Biol. 2017, 24, 471–480.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.M.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s Risk of Bias Tool for Animal Studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ascenzi, P.; di Masi, A.; Leboffe, L.; Fiocchetti, M.; Nuzzo, M.T.; Brunori, M.; Marino, M. Neuroglobin: From structure to function in health and disease. Mol. Asp. Med. 2016, 52, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasha, R.; Moon, T.W. Coenzyme Q10 protects against statin-induced myotoxicity in zebrafish larvae (Danio rerio). Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2017, 52, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinho, B.R.; Reis, S.D.; Hartley, R.C.; Murphy, M.P.; Oliveira, J.M. Mitochondrial superoxide generation induces a parkinsonian phenotype in zebrafish and huntingtin aggregation in human cells. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 130, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, V.; Radhakrishnan, D.M. Parkinson's disease: A review. Neurol. India 2018, 66, 26–S35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, T.M.; Ko, H.S.; Dawson, V.L. Genetic Animal Models of Parkinson's Disease. Neuron 2010, 66, 646–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parkinson, J. An Essay on the Shaking Palsy. J. Neuropsychiatry 2002, 14, 223–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, S.M. Environmental Toxins and Parkinson's Disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2014, 54, 141–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glinka, Y.Y.; Youdim, M.B. Inhibition of mitochondrial complexes I and IV by 6-hydroxydopamine. Eur. J. Pharmacol. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 1995, 292, 329–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langston, J.W. The MPTP Story. J. Park. Dis. 2017, 7, S11–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Granados, K.; Cruz-Reyes, J.; Horta-Marrón, J.F.; Marí-Beffa, M.; Díaz-Rubio, L.; Córdova-Guerrero, I.; Chávez-Velasco, D.; Ocaña, M.C.; Medina, M.A.; Romero-Sánchez, L.B. Synthesis, characterization and biological evaluation of octyltrimethylammonium tetrathiotungstate. BioMetals 2020, 34, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Márquez, J.; Moreira, B.R.; Valverde-Guillén, P.; Latorre-Redoli, S.; Caneda-Santiago, C.T.; Acién, G.; Martínez-Manzanares, E.; Marí-Beffa, M.; Abdala-Díaz, R.T. In Vitro and In Vivo Effects of Ulvan Polysaccharides from Ulva rigida. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vega-Granados, K.; Escobar-Ibarra, P.; Palomino-Vizcaino, K.; Cruz-Reyes, J.; Valverde-Guillén, P.; Latorre-Redoli, S.; Caneda-Santiago, C.; Marí-Beffa, M.; Romero-Sánchez, L. Hexyltrimethylammonium ion enhances potential copper-chelating properties of ammonium thiomolybdate in an in vivo zebrafish model. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2024, 758, 110077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marí-Beffa, M.; Mesa-Román, A.B.; Duran, I. Zebrafish Models for Human Skeletal Disorders. Front. Genet. 2021, 12, 675331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Keywords used during the search |

|---|---|

| Embase | (Broad search): mitochondrial metabolism AND therapy AND neurodegenerative diseases AND zebrafish |

| Web of Science | Documents Topic: mitochondrial metabolism AND therapy AND neurodegenerative diseases AND zebrafish |

| PubMed | PubMed Advanced Search Builder (All fields): mitochondrial metabolism AND therapy AND neurodegenerative diseases AND zebrafish |

| Scopus | Search within (Article title, Abstract, Keywords) mitochondrial metabolism AND therapy AND neurodegenerative diseases AND zebrafish |

| Stage | Stage description | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Article keywords analysis | Keywords: Mitochondrial metabolism; therapy; neurodegenerative diseases; zebrafish |

|

| 2 | Title and abstract analysis | Treatments with compounds of synthetic, semisynthetic, bacterial, plant, animal or synthetic origin | Keywords on other pathologies: Aging, Cancer, respiratory diseases. |

| 3 | Full text analysis |

| Software tools | Reference |

|---|---|

| PubChem | 6 |

| MetaboAnalyst 6.0 | 7 |

| KEGG Database | 8–10 |

| Coconut (COlleCtion of Open Natural ProdUcTs) | 11 |

| Name of the compound | Chemical nature of the compound | Chemical source | Molecular mechanism | Physiological Pathway | Experimental model | Related diseases | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetyl-DL-leucine | Organic acid, carboxylic acid, amino acid | - | Partial restoration of vim and calr mRNA expression levels, improved SRC and basal ATP level | Endoplasmic reticulum mediated phagocytosis | Z | ARSACS | 14 |

| Acteoside | Lipid, saccharolipid | Plant (Cistanche tubulosa) | Acteoside restores mitochondria function through the upregulation of PGC-1α and UCP-2 and suppresses LPS-stimulated M1 polarization | AMPK and NF-κB signaling pathway | Z and CC | Alzheimer’s disease | 15 |

| Apigenin | Phenylpropanoid, flavonoid, hidroxyflavonoid | Plant (Camellia sinensis) | Apigenin mitigates oxidative stress by the Nrf2/ARE mechanism | Nrf2 pathway | Z | Hyperglycemia-associated amnesia | 16 |

| Berberine derivate (BBRP) | Alkaloid, protoberberine alkaloid | Plant (Coptis chinensis) | Berberine inhibits the accumulation of Pink1 protein and the overexpression of LC3 protein, regulators related to mitochondrial autophagy during Parkinson’s disease | Ubiquitin-dependent mitophagy and receptor-mediated mitophagy | Z and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 17 |

| BHDPC | A pyrimidine derivative | Synthetic | BHDPC decreases MPP+-induced mitochondrial membrane potential loss and caspase 3 activation, via activating PKA/CREB survival signaling and up-regulating Bcl2 expression | Intrinsic mitochondrial apoptotic pathway | Z and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 18 |

| BmE-PtNPs | Platinum nanoparticles with aqueous extract of Bacopa monnieri leaves | Plant (Bacopa monnieri) | BmE-PtNPs alleviates the ROS generation, scavenges free radicals, and demonstrates the same activity of mitochondrial complex I, oxidizing NADH to NAD+ | Mitochondrial respiratory chain | Z | Parkinson’s disease | 19 |

| Calcitriol | Lipid, steroid, vitamin D | - | Calcitriol rescues locomotor deficit and loss dopaminergic neurons induced by MPP+ | Calcium signaling pathway | Z | Parkinson’s disease | 20 |

| Clofazimine | Phenazine, monochlorobenzene | Synthetic | Clofazimine stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor | Z, CC and CE | Huntigton’s disease | 21 |

| Creatine | Organic acid, carboxylic acid, aminoacid | - | Creatine restores hypolocomotion induced by 3-NPA | Unknown | Z | Huntigton’s disease | 22 |

| Cysteamine birtartrate | An aminothiol salt | - | Cysteamine birtartrate prevents glutathione antioxidant unbalance and increased ROS levels | Glutathione metabolism | Z | Leigh syndrome | 23 |

| 11- Dehydrosinulariolide | Organic chemical, hydrocarbon, terpene, diterpene | Animal (Sinularia flexibilis) | 11-Dehydrosinulariolide upregulates cytosolic DJ-1 expression and promotes its translocation into mitochondria and the nucleus. 11-Dehydrosinulariolide also activates Akt and induces upregulation of p-CREB, and Nrf2/HO-1 pathways | p-CREB, and Nrf2 pathways | Z, R, and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 24 |

| 24- Epibrassinolide | Lipid, steroid, steroid lactone. | Plant (Fabaceae) | 24-epibrassinolide reverses the locomotor deficits caused by 6-OHDA | Unknown | Z | Parkinson’s disease | 25 |

| Guanabenz | Aromatic compound, benzenoid, dichlorobenzene | Synthetic | Guanabenz increases the levels of phosphorylated-eIF2α protein | Endoplasmic reticulum stress and mitochondrial stress | M and Z* | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 26,27 |

| HCH6-1 | A dipeptide, a competitive antagonist of formyl peptide receptor 1 | Synthetic | HCH6-1 prevents the activation of the inflammasome and upregulation of active caspase-1, TNF-α, IL-1β and active caspase-3 levels in microglia; and inhibits mitochondrial oxidative stress and apoptosis of dopaminergic neurons. | NLRP3 inflammasome and pro-inflammatory cytokines | Z, M, and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 28 |

| Hesperidin | Phenylpropanoid, flavonoid, flavonoid glycoside | Plant (Citrus sp) | Hesperidin rescues mitochondrial membrane potential, reduces oxidative stress and downregulates kinases lrrk2, gsk3 β, casp9, and polg | Ubiquitin-dependent mitophagy and receptor-mediated mitophagy | Z and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 29 |

| Idebenone | Organic chemical, quinone, benzoquinone | Semisynthetic analogue of ubiquinone | Idebenone restores the BNIP3L and citrate synthase expression to reduce ROS production and restore mtDNA copy number | Ubiquitin-dependent mitophagy and receptor-mediated mitophagy | Z | Limb – girdle muscular dystrophy 2G | 30 |

| KC14 | Organic acid, carboxylic acid, peptide | Animal (Cyprinus carpio) | KC14 enhances acetylcholinesterase activity and significantly reduces intracellular ROS levels. | Glutathione metabolism | Z | Non-specific disease | 31 |

| Mangiferin | Organic heterocyclic compound, benzopyran, 1-benzopyran | Plant (Mangifera indica) | Mangiferin regulates PD-related genes such as lrrk2, vps35, atp13a, dnajc6, and uchl1 | Ubiquitin-dependent mitophagy and receptor-mediated mitophagy | Z | Parkinson’s disease | 32 |

| Melatonin | Organoheterocyclic compound, indole | - | Melatonin improves the memory dysfunction caused by 3-NPA | Unknown | Z | Huntigton’s disease | 22 |

| Melatonin | Organoheterocyclic compound, indole | - | Not determined | Lipid metabolism | Z | Parkinson’s disease | 33 |

| MS-275 | Organic chemical, carboxylic acid, benzoate, benzamide | Semisynthetic | MS-275 inhibits HDAC1 and rescues the metabolic impairment induced by MPP+ | P53 signaling pathway | Z | Parkinson’s disease | 34 |

| N - Acetylcysteine | Organic acid, carboxylic acid, amino acid | - | N-acetylcysteine prevents glutathione antioxidant unbalance and increased ROS levels. | Glutathione metabolism | Z | Leigh syndrome | 23 |

| Naringenin | Phenylpropanoid, flavonoid, flavan, flavanone | Plant (Camellia sinensis, Humulus lupulus) | Narigenin downregulates the expression of some Parkinsonian genes such as casp9, lrrk2 and polg, and upregulate pink1 | Ubiquitin-dependent mitophagy and receptor-mediated mitophagy | Z and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 35 |

| Nicotinamide | Organoheterocyclic compound, pyridine, pyridinecarboxylic acid | Fungi (Lactarius subplinthogalus) | Nicotinamide elevates levels of OCR, increases mitochondrial complex I activity and reduces NAD+/NADH ratio | Mitochondrial respiratory chain | Z and CC | Leigh syndrome | 36 |

| Nimodipine | Benzenoid, benzene, nitrobenzene, dihydropyridine derivative | Semisynthetic Calcium channel antagonist | Nimodipine antagonizes calcium channels reducing the need for calcium | Calcium signaling pathway | Z | Parkinson’s disease | 20 |

| Nitrite | Organic chemical, nitrite | - | Nitrite promotes complex I S-nitrosation and activation of the antioxidant Nrf2 pathway | Unfolded protein response | Z, R, and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 37 |

| Olmesartan | Organic heterocyclic compound, azole, tetrazole | Semisynthetic | Olmesartan inhibits 1 AGTR1 and restores the expression of mitochondrial pathway genes. | Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System | Z and D | Parkinson’s disease | 38 |

| Paeonolum | Organic oxygen compound, organooxygen compound, carbonyl compund | Plant (Paeonia suffruticosa) | Paeonolum restores the damage caused by MPP+ via reducing the accumulation of ROS, attenuating the reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential, restoring the levels of GSH and reducing the cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activity | Mitochondrial cell death | Z and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 39 |

| Probucol | Organic chemical, hydrocarbon, benzene derivative, phenol | Bacteria (Penicillium citrinum) | Probucol enhances mitophagy via the ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA1 and its effects on lipid droplets. | Cholesterol metabolism | Z, D and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 40 |

| Proxison | Phenylpropanoid, flavonoid | Semisynthetic | Proxison significantly dampens induction of the NRF2 antioxidant response pathway. | Unfolded protein response | Z and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 41 |

| Quercetin | Phenylpropanoid, flavonoid, flavonoid glycoside | Plant (Salvia miltiorrhiza and Hydrangea serrata) | Quercetin inhibits the iNOS/NO system and downregulates the overexpression of pro-inflammatory genes | iNOS/NO pathway | Z and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 42 |

| Schisantherin A | Phenylpropanoid, tannin, hydrolysable tannin | Plant (Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill | Schisantherin A regulates intracellular ROS accumulation and inhibit NO overproduction by downregulating the over-expression of iNOS | MAPK, PI3K/AKT and GSK3β pathway | Z and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 43 |

| SR1 agonist PRE-084 | Heterocyclic compound, oxazine, morpholine | Synthetic | SR1 agonist PRE-084 modulates IP3R by stabilizing its conformation at the MAMs. | Ca2+ transfer from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol or mitochondria | Z and M | Wolfram syndrome | 44 |

| Tauroursodeoxycholic acid | Lipid, steroid, bile acid | - | Partially restores vim and calr mRNA expression levels and improves SRC and basal ATP level. | Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis | Z | ARSACS | 14 |

| Terazosin | Heterocyclic compound, quinazoline | - | Terazosin increases the activity of PGK1. | HIF-1 signaling pathway | Z, M and CC | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 45 |

| Theacrine | Organoheterocyclic compound, imidazopyrimidine, purine | Plant (Camellia assamica var. Kucha.) | Theacrine activates SIRT3, which promotes deacetylation of SOD2, thereby reducing ROS accumulation and restoring mitochondrial function. | Mitochondrial respiratory chain | Z, R, M, and CC | Parkinson’s disease | 46 |

| Trifluoperazine | Organic chemical, sulfur compound, phenothiazine | Plant (Crotalaria pallida) | Trifluoperazine acts downstream of PINK1/PARKIN to restore TFEB nuclear translocation | Ubiquitin-dependent mitophagy and receptor-mediated mitophagy | Z | Parkinson’s disease | 47 |

| Vitamin C | Organoheterocyclic compound, dihydrofuran, furanone, butenolide | - | Vitamin C improves the memory dysfunction and restores hypolocomotion caused by 3-NPA | Unknown | Z | Huntington’s disease | 22 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zhang ZJ et al (2011)42 | Y | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | Y | 4 | |

| Nellore J et al. (2013)19 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | Y | 2 | |

| Vaccaro A et al. (2013)27 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 1 | |

| Jiang HQ et al. (2014)26 | Y | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | Y | NC | 4 | |

| Chong C et al. (2015)18 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | Y | 3 | |

| Lu XL et al (2015)39 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | Y | Y | 4 | |

| Pinho BR et al. (2015) 34 | Y | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | Y | 4 | |

| Zhang LQ et al (2015)43 | NC | Y | NC | NC | Y | NC | Y | NC | Y | NC | 4 | |

| Feng CW et al. (2016)24 | Y | Y | NC | NC | Y | NC | Y | NC | Y | NC | 5 | |

| Drummonf NJ et al. (2017)41 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 2 | |

| Zhang Y et al (2017)47 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | Y | 3 | |

| Milanese C et al. (2018)37 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | Y | NC | 3 | |

| Duan WJ et al. (2020)46 | Y | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 3 | |

| Kesh S et al. (2021)29 | NC | Y | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | Y | 4 | |

| Kesh S et al (2021)35 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | Y | 3 | |

| Kim GHJ et al (2021)38 | NC | Y | NC | NC | Y | NC | Y | NC | Y | Y | 5 | |

| Li Y et al. (2021)15 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 2 | |

| Naef V et al. (2021)14 | Y | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | Y | 4 | |

| Wang L et al. (2021)17 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 2 | |

| Chaytow H et al (2022)45 | Y | Y | NC | NC | Y | NC | Y | NC | Y | Y | 6 | |

| Crouzier L et al. (2022)44 | NC | Y | NC | Y | Y | NC | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7 | |

| Lv X et al. (2022)30 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | NC | Y | NC | 3 | |

| Gomes A et al. (2023)25 | Y | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | Y | Y | 5 | |

| Haroon S et al. (2023)23 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 2 | |

| Moskal N et al (2023)40 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 2 | |

| Wang HL et al. (2023)28 | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 1 | |

| Haridevamuthu B et al. (2024)16 | Y | Y | NC | NC | NC | Y | Y | NC | Y | Y | 6 | |

| Kim M et al. (2024)20 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | Y | 3 | |

| Li X et al. (2024)21 | Y | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 3 | |

| Lo CH et al. (2024)36 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 2 | |

| Pang MZ et al. (2024)33 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 2 | |

| Qin F et al. (2024)32 | Y | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 3 | |

| Vijayanand M et al. (2024)31 | NC | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 2 | |

| Wiprich M et al. (2024)22 | Y | Y | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | NC | Y | NC | 3 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).