Submitted:

26 December 2024

Posted:

30 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

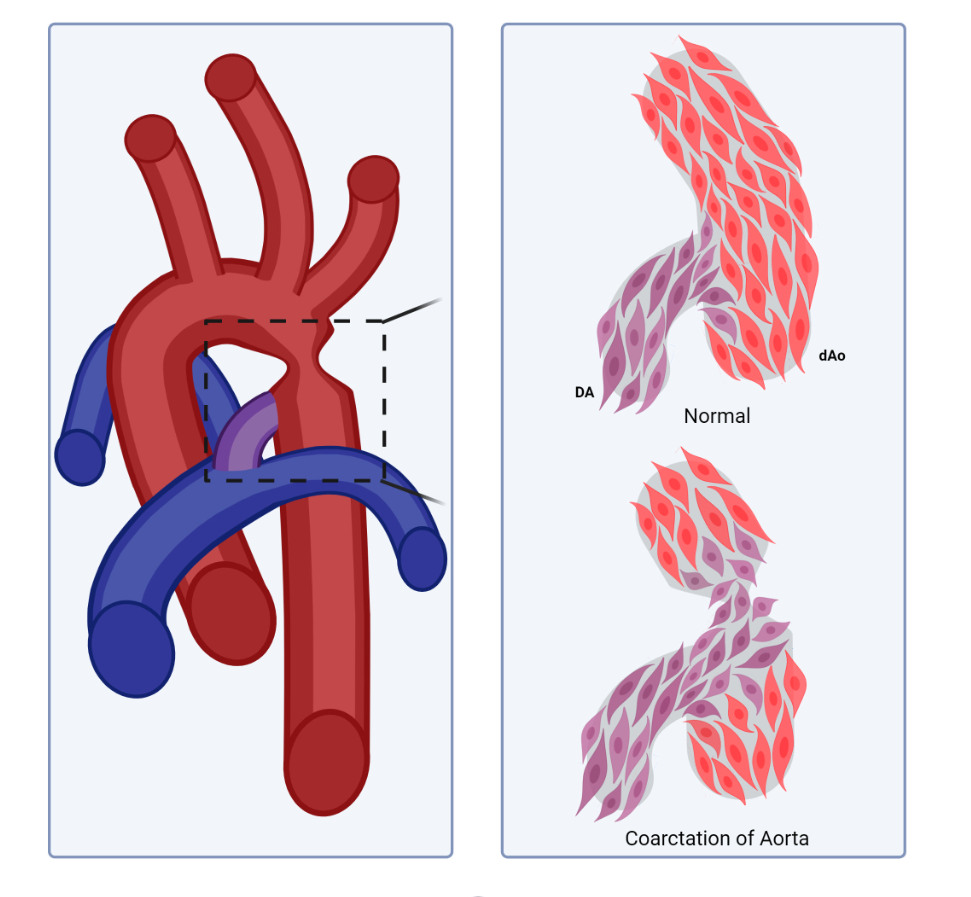

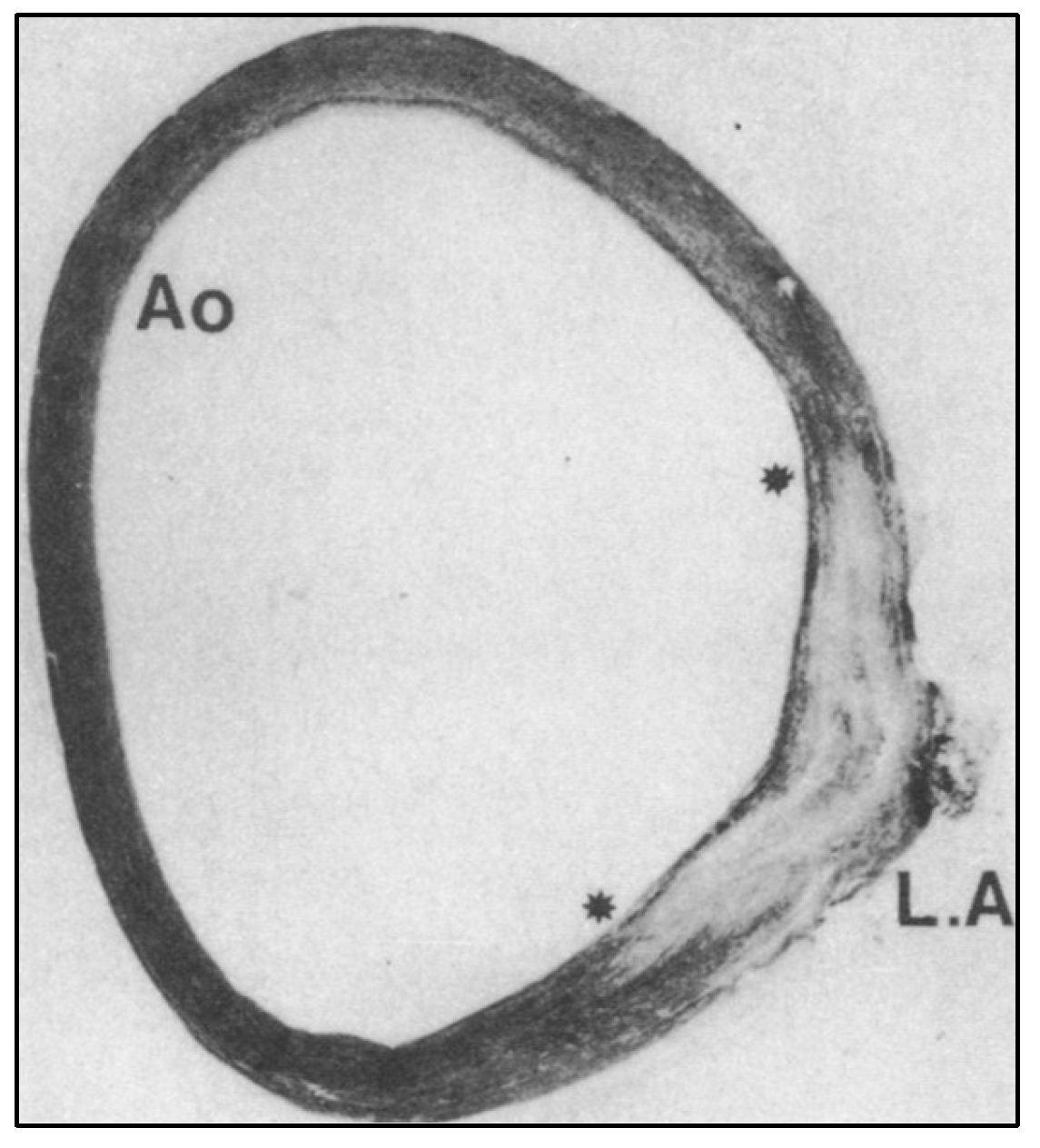

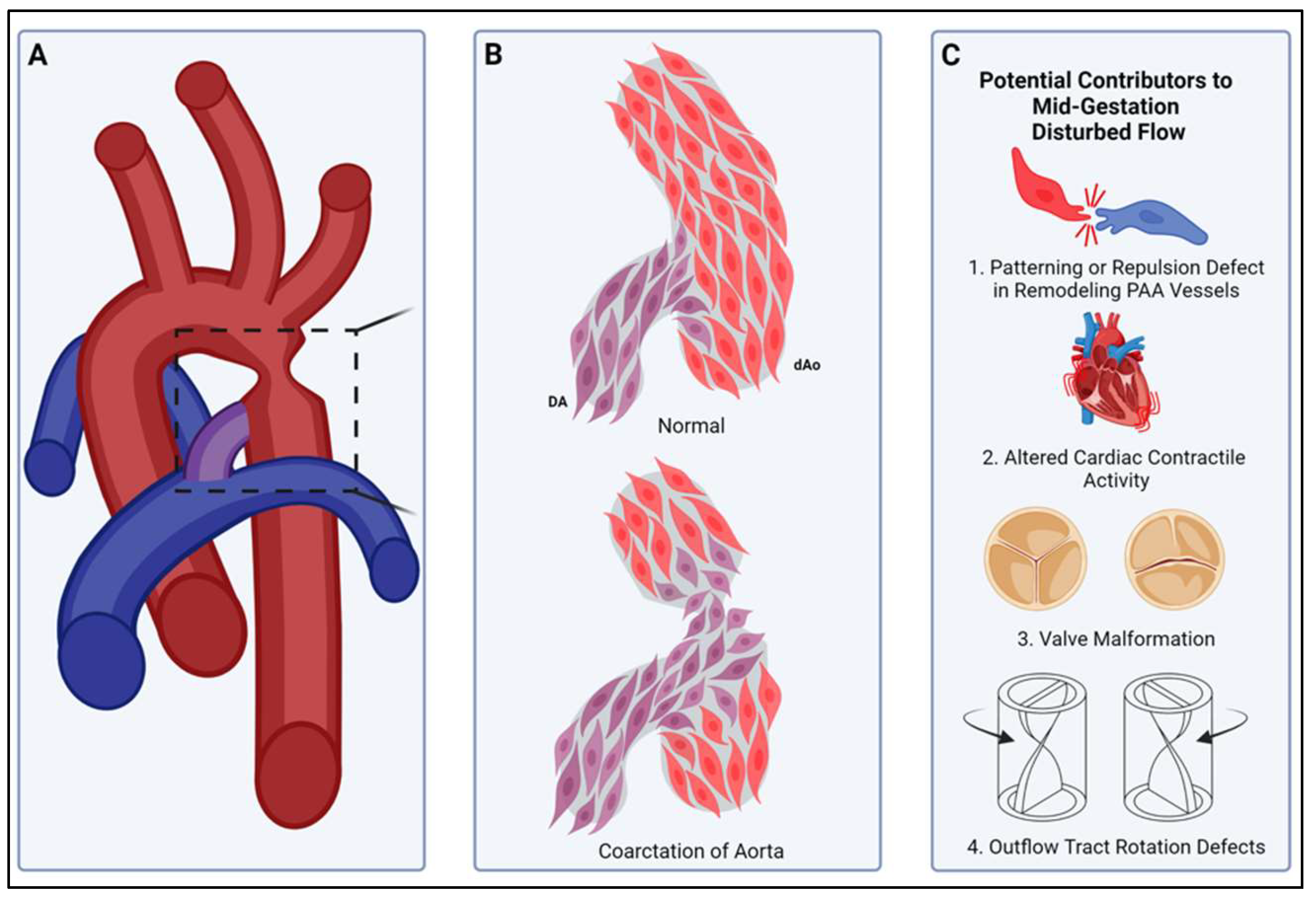

Compartment boundaries divide the embryo into segments with distinct fates and functions. In the vascular system, compartment boundaries organize endothelial cells into arteries, capillaries, and veins that are the fundamental units of a circulatory network. For vascular smooth muscle cells (SMCs) such boundaries produce mosaic patterns of investment based on embryonic origins with important implications for the non-uniform distribution of vascular disease later in life. Morphogenesis of blood vessels requires vascular cell movements within compartments as highly-sensitive responses to changes in fluid flow shear stress and wall strain. These movements underlie remodeling of primitive plexuses, expansion of lumen diameters, regression of unused vessels, and building multilayered artery walls. Although loss of endothelial compartment boundaries can produce arterial-venous malformations, little is known about the consequences of mislocalization or failure to form SMC origin-specific boundaries during vascular development. We propose that the failure to establish a normal compartment boundary between cardiac neural crest-derived SMCs of the 6th pharyngeal arch artery (future ductus arteriosus) and paraxial mesoderm-derived SMCs of the dorsal aorta in mid-gestation embryos leads to aortic coarctation observed at birth. This model raises new questions about the effects of fluid flow dynamics on SMC investment and the formation of SMC compartment borders during pharyngeal arch artery remodeling and vascular development.

Keywords:

Introduction

Development of the Ductus Arteriosus

Compartment Boundaries in Embryonic Development

Compartment Boundaries in Vascular Development

Repulsive Guidance Molecule Signaling

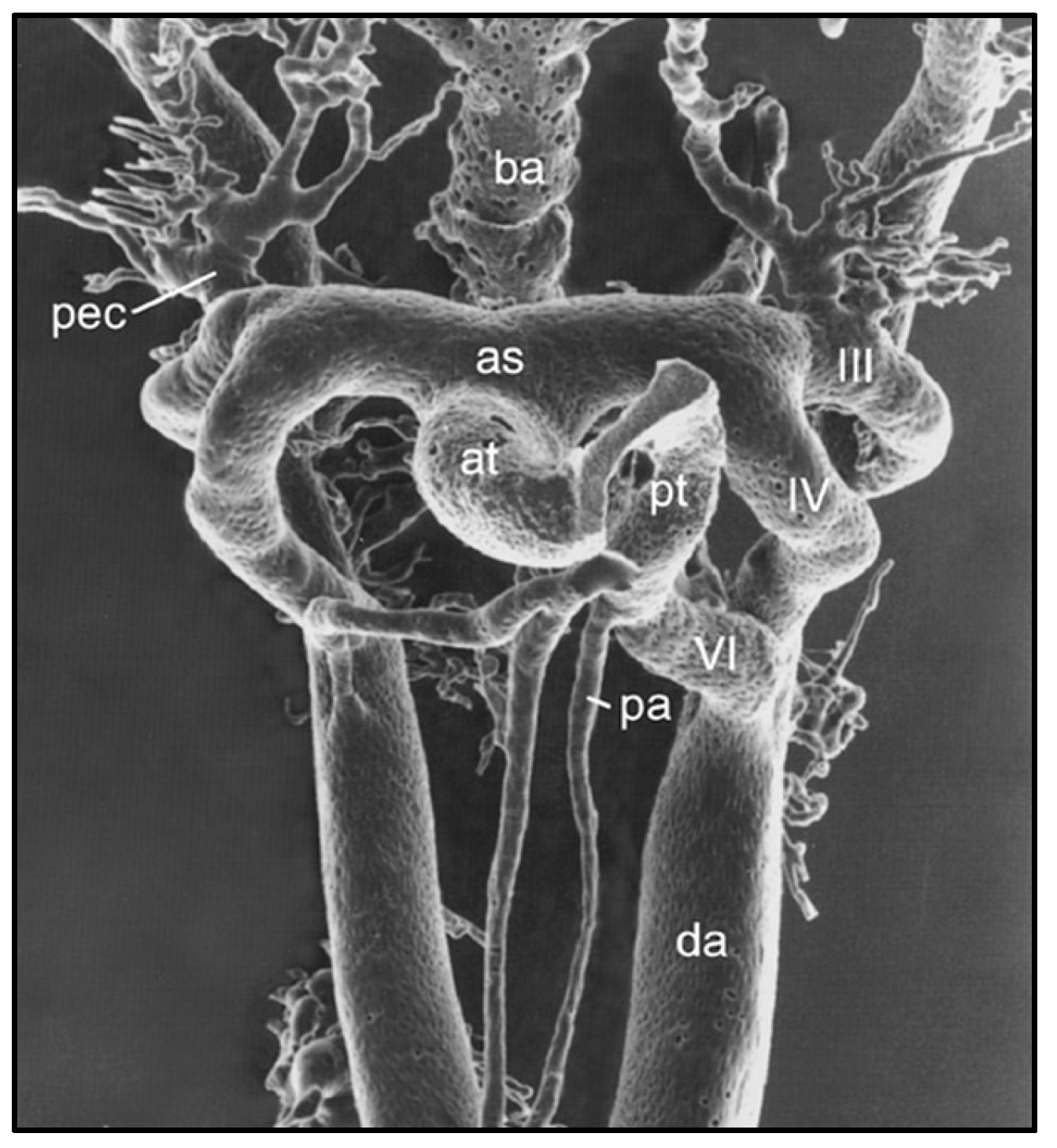

Remodeling of the Pharyngeal Arch Artery Complex

The Role of Hemodynamics in PAA Remodeling

Role of Hemodynamics in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cell Investment

Interactions Between Different Types of Vascular SMC Progenitors

A Smooth Muscle Compartment Boundary Model for CoA

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoffman JI, Kaplan S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002, 39, 1890–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai CT, Isenburg JL, Canfield MA et al. National population-based estimates for major birth defects, 2010-2014. Birth Defects Res 2019, 111, 1420–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagariello A, Breuer C, Birkner Y et al. Functional null mutations in the gonosomal homologue gene TBL1Y are associated with non-syndromic coarctation of the aorta. Curr Mol Med 2012, 12, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freylikhman O, Tatarinova T, Smolina N et al. Variants in the NOTCH1 gene in patients with aortic coarctation. Congenit Heart Dis 2014, 9, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosmann J, Uebe S, Dittrich S, Rüffer A, Ekici A, Toka O. Novel loci for non-syndromic coarctation of the aorta in sporadic and familial cases. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0126873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez-Castro M, Pichon O, Briand A, Poulain D, Gournay V, David A, Le Caignec C. Disruption of the SEMA3D gene in a patient with congenital heart defects. Human Mutation 2015, 36, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjornsson T, Thorolfsdottir RB, Sveinbjornsson G et al. A rare missense mutation in MYH6 associates with non-syndromic coarctation of the aorta. Eur Heart J 2018, 9, 3243–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donadille B and Christin-Maitre, S. Heart and Turner syndrome. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2021, 82, 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiruma T, Nakajima Y, Nakamura H. Development of pharyngeal arch arteries in early mouse embryo. J Anat 2002, 201, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- May SR, Stewart NJ, Chang W, Peterson AS. A Titin mutation defines roles for circulation in endothelial morphogenesis. Dev Biol 2004, 270, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin O, Burch M, Manning N, Sleeman K, Gould S, Archer N. Prenatal diagnosis of coarctation of the aorta improves survival and reduces morbidity. Heart 2002, 87, 67–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houshmandi MM, Eckersley L, Fruitman D, Mills L, Power A, Hornberger LK. Fetal diagnosis is associated with improved perioperative condition of neonates requiring surgical intervention for coarctation. Pediatr Cardiol 2021, 42, 1504–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldo KL, Kirby ML. Cardiac neural crest contribution to the pulmonary artery and sixth aortic arch artery complex in chick embryos aged 6 to 18 days. Anat Rec 1993, 237, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bökenkamp R, DeRuiter MC, van Munsteren C, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Insights into the pathogenesis and genetic background of patency of the ductus arteriosus. Neonatology 2010, 98, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Peterson JC, Wisse LJ, Roest AAW, Poelmann RE, Bökenkamp R, Elzenga NJ, Kaxekamp M, Bartelings MM, Jongbloed MRM, DeRuiter MC. Pulmonary ductal coarctation and left pulmonary artery interruption; pathology and role of neural crest and second heart field during development. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0228478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang X, Chen D, Chen K, Jubran A, Ramirez A, Astrof S. Endothelium in the pharyngeal arches 3,4 and 6 is derived from the second heart field. Dev Biol 2017, 421, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang X, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest. Development 2000, 127, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasteson P, Johansson BR, Jukkola T, Breuer S, Akyürek LM, Partanen J, Lindahl P. Developmental origin of smooth muscle cells in the descending aorta in mice. Development 2008, 135, 1823–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elzenga NJ, Gittenberger-de Groot AC. Localised coarctation of the aorta. An age dependent spectrum. Br Heart J 1983, 49, 317–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabinovitch, M. Cell-extracellular matrix interactions in the ductus arteriosus and perinatal pulmonary circulation. Semin Perinatol 1996, 20, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bentley RET, Hindmarch CCT, Dunham-Snary KJ, Snetsinger B, Mewburn JD, Thébaud A, Lima PD, Thébaud B, Archer SL. The molecular mechanisms of oxygen-sensing in human ductus arteriosus smooth muscle cells: A comprehensive transcriptome profile reveals a central role for mitochondria. Genomics 2021, 113, 3128–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahmann C, Basler K. Compartment boundaries: at the edge of development. Trends Genet 1999, 15, 320–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand-Saberi B, Christ B. Evolution and development of distinct cell lineages derived from somites. Curr Top Dev Biol 2000, 48, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Groves AK, LaBonne C. Setting appropriate boundaries: fate, patterning and competence at the neural plate border. Dev Biol 2014, 389, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagotto, F. The cellular basis of tissue separation. Development 2014, 141, 3303–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Dahmann C. Establishing compartment boundaries in Drosophila wing imaginal discs: An interplay between selector genes, signaling pathways and cell mechanics. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2020, 107, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagotto, F. Cell sorting at embryonic boundaries. Sem Cell Dev Biol 2020, 107, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maves L, Jackman W, Kimmel CB. FGF3 and FGF8 mediate a rhombomere 4 signaling activity in the zebrafish hindbrain. Development 2002, 129, 3825–3837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke JE, Kemp HA, Moens CB. EphA4 is required for cell adhesion and rhombomere-boundary formation in the zebrafish. Curr Biol 2005, 15, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiecker C, Lumsden A. Compartments and their boundaries in vertebrate brain development. Nat Rev Neurosci 2005, 6, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tannahill D, Cook GM, Keynes RJ. Axon guidance and somites. Cell Tissue Res 1997, 290, 275–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahashi Y, Koizumi K, Takagi A, Kitajima S, Inoue T, Koseki H, Saga Y. Mesp2 initiates somite segmentation through the Notch signalling pathway. Nat Genet 2000, 25, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe T, Sato Y, Saito D, Tadakoro R, Takahashi Y. EphrinB2 coordinates the formation of a morphological boundary and cell epithelialization during somite segmentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2009, 106, 7467–7472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco D, Meilhac SM, Christoffels VM, Kispert A, Buckingham M, Kelley RG. Left and right ventricular contributions to the formation of the interventricular septum in the mouse heart. Dev Biol 2006, 294, 366–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathiriya IS, Dominguez MH, Ro KS, Muncie-Vasic JM, Devine WP, Hu KM, Hota SK, Garay BI, Quintero D, Goyal P, Matthews MN, Thomas R, Sukonnik T, Miguel-Perez D, Winchester S, Brower EF, Forjaz A, Wu PH, Wirtz D, Kiemen AL, Bruneau BG. A disrupted compartment boundary underlies abnormal cardiac patterning and congenital heart defects. bioRxiv, 5789. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimmel RA, Turnbull DH, Blanquet V, Wurst W, Loomis CA, Joyner AL. Two lineage boundaries coordinate vertebrate apical ectodermal ridge formation. Genes Dev 2000, 14, 1377–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu Q, Chen H, Johnson RL. Lmx1b-expressing cells in the mouse limb bud define a dorsal mesenchymal lineage compartment. Genesis 2009, 47, 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morata G, Herrera SC. Cell reprogramming during regeneration in Drosophila: transgression of compartment boundaries. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2016, 40, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Dahmann C. Establishing compartment boundaries in Drosophila wing imaginal discs: An interplay between selector genes, signaling pathways and cell mechanics. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2020, 107, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharrock TE, Sanson B. Cell sorting and morphogenesis in early Drosophila embryos. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2020, 107, 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, PA. The making of a fly: the genetics of animal design. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, UK; 1992.

- Worley MI, Setiawan L, Hariharan IK. Regeneration and transdetermination in Drosophila imaginal discs. Annu Rev Genet 2012, 46, 289–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townes PL, Holtfreter J. Directed movements and selective adhesion of embryonic amphibian cells. J Exp Zool 1955, 128, 53–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nose A, Nagafuchi A, Takeichi M. Expressed recombinant cadherins mediate cell sorting in model systems. Cell 1988, 54, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, MS. Differential adhesion in morphogenesis: a modern view. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2007, 17, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brodland, GW. The differential interfacial tension hypothesis (DITH): a comprehensive theory for the self-rearrangement of embryonic cells and tissues. J Biomech Eng 2002, 124, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang HU, Xhen ZF, Anderson DJ. Molecular distinction and angiogenic interaction between embryonic arteries and veins revealed by ephrin-B2 and its receptor Eph-B4. Cell 1998, 93, 741–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale NW, Baluk P, Pan L, Kwan M, Holash J, DeChiara TM, McDonald DM, Yancopoulos GD. Ephrin-B2 selectively marks arterial vessels and neovascularization sites in the adult, with expression in both endothelial and smooth muscle cells. Dev Biol 2001, 230, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adams RH, Eichmann A. Axon guidance molecules in vascular patterning. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2010, 2, a001875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin D, Garcia-Cardena G, Hayashi S, Gerety S, Asahara T, Stavrakis G, Isner J, Folkman J, Gimbrone MA Jr, Anderson DJ. Expression of ephrinB2 identifies a stable genetic difference between arterial and venous vascular smooth muscle as well as endothelial cells, and marks subsets of microvessels at sites of adult neovascularization. Dev Biol 2001, 230, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finney AC, Orr AW. Guidance molecules in vascular smooth muscle. Front Physiol 2018, 9, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian X, Hu T, Je L, Zhang H, Huang X, Poelmann RE, Liu W, Yang Z, Yan Y, Pu WT, Zhou B. Peritruncal coronary endothelial cells contribute to proximal coronary artery stems and their aortic orifices in the mouse heart. PLoS One 2013, 8, e80857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang X, Rowitch DH, Soriano P, McMahon AP, Sucov HM. Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest. Development 2000, 127, 1607–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majesky, MW. Developmental basis of vascular smooth muscle diversity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2007, 27, 1248–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passman JN, Dong XR, Wu SP, Maguire CT, Hogan KA, Bautch VL, Majesky MW. A sonic hedgehog signaling domain in the arterial adventitia supports resident Sca1+ smooth muscle progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105, 9349–9354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada H, Rateri DL, Moorleghen JJ, Majesky MW, Daugherty A. Smooth muscle cells derived from the second heart field and cardiac neural crest reside in spatially distinct domains in the media of the ascending aorta – brief report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017, 37, 1722–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin CJ, Hunkins B, Roth R, Lin CY, Wagenseil JE, Mecham RP. Vascular smooth muscle cell subpopulations and neointimal formation in mouse models of elastin insufficiency. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2021, 41, 2890–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawada H, Katsumata y, Higashi H, Zhang C, Li Y, Morgan S, Lee LH, Singh SA, Chen JZ, Franklin MK, Moorleghen JJ, Howatt DA, Rateri DL, Shen YH, LeMaire SA, Aikawa M, Majesky MW, Lu HS, Daugherty A. Second heart field-derived cells contribute to angiotensin II-mediated ascending aortopathies. Circulation 2022, 145, 987–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedroza AJ, Dalal AR, Shad R. Yokoyama N, Nakamura K, Cheng P, Wirka RC, Mitchel O, Baiocchi M, Hiesinger W, Quertermous T, Fischbein MP. Embryologic origin influences smooth muscle cell phenotypic modulation signatures in murine Marfan syndrome aortic aneurysm. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2022, 42, 1154–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basler K, Struhl G. Compartment boundaries and the control of Drosophila limb pattern by hedgehog protein. Nature 1994, 368, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence PA, Struhl G. Morphogens, compartments, and pattern: Lessons from Drosophila? Cell 1996, 85, 951–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessier-Lavigne M, Goodman CS. The molecular biology of axon guidance. Science 1996, 274, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuhdi N, Ortega B, Giovannone D, Ra H, Reyes M, Asención V, McNicoll I, Ma L, de Bellard ME. Slit molecules prevent entrance of trunk neural crest cells in developing gut. Int J Dev Neurosci 2015, 41, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lepore JJ, Mericko PA, Cheng L, Lu MM, Morrisey EE, Parmacek MS. GATA-6 regulates semaphorin 3C and is required in cardiac neural crest for cardiovascular morphogenesis. J Clin Invest 2006, 116, 929–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- High F, Epstein JA. Signaling pathways regulating cardiac neural crest migration and differentiation. Novartis Found Symp 2007, 283, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyofuku T, Yoshida J, Sugimoto T, Yamamoto M, Makino N, Takamatsu H, Takegahara N, Suto D, Hori M, Fujisawa H, Kumanogoh A, Kikutani H. Repulsive and attractive semaphorins cooperate to direct the navigation of cardiac neural crest cells. Dev Biol 2008, 321, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholl AM, Kirby ML. Signals controlling neural crest contributions to the heart. WIRES 2009, 1, 220–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulz Y, Wehner P, Optiz L, Salinas-Riester G, Bongers EMHF, van Ravenswaaij-Arts CMA, Wincent J, Schoumans J, Kohlhase J, Borchers A, Pauli S. CHD7, the gene mutated in CHARGE syndrome, regulates genes involved in neural crest cell guidance. Hum Genet 2014, 133, 997–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kodo K, Shibata S, Miyagawa-Tomita S, Ong SG, Takahashi H, Kume T, Okano H, Matsuoka R, Yamagishi H. Regulation of Sema3c and the interaction between cardiac neural crest and second heart field during outflow tract development. Sci Rep 2017, 7, 6771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schussler O, Gharibeh L, Mootoosamy P, Murith N, Tien V, Rougemont AL, Sologashvili T, Suuronen E, Lecarpentier Y, Ruel M. Cardiac neural crest cells: their rhombomeric specification, migration, and association with heart and great vessel anomalies. Cell Mol Neurobiol 2021, 41, 403–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker SFS, Mayor R, Kashef J. Cadherin-11 mediates contact inhibition of locomotion during Xenopus neural crest cell migration. PLoS One 2013, 8, e85717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Fontaine C, Matthews HK, Kuriyama S, Moreno M, Dunn GA, Parsons M, Stern CD, Mayor R. Contact inhibition of locomotion in vivo controls neural crest directional migration. Nature 2008, 456, 957–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayor R, Carmona-Fontaine C. Keeping in touch with contact inhibition of locomotion. Trends Cell Biol 2010, 20, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theveneau E, Marchant L, Kuriyama S, Gull M, Moepps B, Parsons M, Mayor R. Collective chemotaxis requires contact-dependent cell polarity. Dev Cell 2010, 19, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willecke M, Hamaratoglu F, Sansores-Garcia L, Tal C, Halder G. Boundaries of Dachsous Cadherin activity modulate the Hippo signaling pathway to induce cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008, 105, 14897–14902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang J, Cheng L, Li J, Chen M, Zhou D, Lu MM, Proweller A, Epstein JA, Parmacek MS. Myocardin regulates expression of contractile genes in smooth muscle cells and is required for closure of the ductus arteriosus in mice. J Clin Invest 2008, 118, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yancopoulos GD, Klagsbrun M, Folkman J. Vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, and growth factors: ephrins enter the fray at the border. Cell 1998, 93, 661–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu MF, Liao CY, Wang LY, Chang JT. The role of Slit-Robo signaling in the regulation of tissue barriers. Tissue Barriers 2017, 5, e1331155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldo K, Hutson M, Ward C, Zdanowicz M, Stadt H, Kumiski D, Abu-Issa R, Kirby M. Secondary heart field contributes myocardium and smooth muscle to the arterial pole of the developing heart. Dev Biol 2005, 281, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topouzis S, Majesky MW. Smooth muscle lineage diversity in the chick embryo. Two types of aortic smooth muscle cell differ in growth and receptor-mediated transcriptional responses to transforming growth factor-beta. Dev Biol 1996, 178, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacFarlane EG, Parker SJ, Shin JY, Kang BE, Ziegler SG, Creamer TJ, Bagirzadeh R, Bedja D, Chen Y, Calderon JF, Weissler K, Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Lindsay ME, Habashi JP, Dietz HC. Lineage-specific events underlie aortic root aneurysm pathogenesis in Loeys-Dietz syndrome. J Clin Invest 2019, 129, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukla S, Jana S, Sanford N, Lee C, Liu L, Cheng P, Quertermous T, Dichek DA. Single cell transcriptomics identifies selective lineage-specific regulation of genes in aortic smooth muscle cells in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol.

- Weldy CS, Cheng PP, Guo W, Pedroza AJ, Dalal AR, Worssam MD, Sharma D, Nguyen T, Kundu R, Fischbein MP, Quertermous T. The epigenomic landscape of single vascular cells reflects developmental origin and identifies disease risk loci. The epigenomic landscape of single vascular cells reflects developmental origin and identifies disease risk loci. bioRxiv 2022, 492517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe M, Sesti C, Washington IM, Du L, Dronadula N, Chin MT, Stolz DB, Davis AC, Dichek DA. Transforming growth factor-β signaling in myogenic cells regulates vascular morphogenesis, differentiation, and matrix synthesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2012, 32, e1–e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Noble F, Moyon D, Pardanaud L, Yuan L, Djonov V, Matthijsen R, Bréant C, Fluery V, Eichmann A. Flow regulates arterial-venous differentiation in the chick embryo yolk sac. Development 2004, 131, 361–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lucitti JL, Jones EAV, Huang C, Chen J, Fraser SE, Dickinson ME. Vascular remodeling of the mouse yolk sac requires hemodynamic force. Development 2007, 134, 3317–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski WJ, Dur O, Wang Y, Patrick MJ, Tinney JP, Keller BB, Pekkan K. Critical transitions in early embryonic aortic arch patterning and hemodynamics. PLoS One 2013, 8, e60271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langille, BL. Arterial remodeling: relation to hemodynamics. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1996, 74, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bi W, Drake CJ, Schwarz JJ. The transcription factor Mef2c-null mouse exhibits complex vascular malformations and reduced cardiac expression of angiopoietin-1 and VEGF. Dev Biol 1999, 211, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isogai S, Lawson ND, Torrealday S, Horiguchi M, Weinstein BM. Angiogenic network formation in the developing vertebrate trunk. Development 2009, 130, 5281–5290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Udan RS, Vadakkan TJ, Dickinson ME. Dynamic responses of endothelial cells to changes in blood flow during vascular remodeling of the mouse yolk sac. Development 2013, 140, 4041–4050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langille, BL. Morphologic responses of endothelium to shear stress: reorganization of the adherens junction. Microcirculation 2001, 8, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzima E, Irani-Tehrani M, Klosses WB, Dejana E, Schultz DA, Engelhardt B, CaoG, DeLisser H, Schwartz MA. A mechanosensory complex that mediates the endothelial cell response to fluid shear stress. Nature 2005, 437, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones EAV, le Noble F, Eichmann A. What determines blood vessel structure? Genetic prespecification vs hemodynamics. Physiology 2006, 21, 388–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baeyens N, Bandopadhyay C, Coon BG, Yun S, Schwartz MA. Endothelial fluid shear stress sensing in vascular health and disease. J Clin Invest 2016, 126, 821–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowalski WJ, Pekkan K, Tinney JP, Keller BK. Investigating developmental cardiovascular biomechanics and the origins of congenital heart disease. Front Physiol 2014, 5, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Dur O, Patrick MJ, Tinney JP, Tobita K, Keller BB, Pekkan K. Aortic arch morphogenesis and flow modeling in the chick embryo. Ann Biomed Eng 2009, 37, 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yashiro K, Shiratori H, Hamada H. Haemodynamics determined by a genetic programme govern asymmetric development of the aortic arch. Nature 2007, 450, 285–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snider P, Conway SJ. Developmental biology: The power of blood. Nature 2007, 450, 180–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakaya C, Goktas S, Celik M, Kowalski WJ, Keller BB, Pekkan K. Asymmetry in mechanosensitive gene expression during aortic arch morphogenesis. Sci Rep 2018, 8, 16948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greif DM, Kumar M, Lighthouse JK, Hum J, An A, Ding L, Red-Horse K, Espinoza FH, Olson L, Offermanns S, Krasnow MA. Radial construction of an arterial wall. Dev Cell 2012, 23, 482–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada H, Meno C, Watanabe D, Saijoh Y. Establishment of vertebrate left-right asymmetry. Nat Rev Genet 2002, 3, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu C, Liu W, Palie J, Lu MF, Brown NA, Martin JF. Pitx2c patterns anterior myocardium and aortic arch vessels and is required for local cell movement into atrioventricular cushions. Development 2002, 129, 5081–5091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill MC, Kadow ZA, Li L, Tran TT, Wythe JD, Martin JF. A cellular atlas of Pitx2-dependent cardiac development. Development 2019, 146, dev180398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiratori H, Sakuma R, Watanabe M, Hashiguchi H, Michida K, Sakai Y, Nishino J, Saijoh Y, Whitman M, Hamada H. Two-step regulation of left-right asymmetric expression of Pitx2, initiation by nodal signaling and maintenance by Nkx2. Mol Cell 2001, 7, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phoon CK, Aristizabal O, Turnbull DH. 40 MHz doppler characterization of umbilical and dorsal aortic blood flow in the early mouse embryo. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2000, 26, 1275–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirby, ML. Cardiac development. Oxford University Press, Oxford OX2 6DP, United Kingdom, 2007. ISBN: 9780195178197.

- Chen X, Gays D, Milia C, Santoro MM. Cilia control vascular mural cell recruitment in vertebrates. Cell Rep 2017, 18, 1033–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padget RL, Mohite SS, Hoog TG, Justis BS, Green BE, Udan RS. Hemodynamic force is required for vascular smooth muscle cell recruitment to blood vessels during mouse embryonic development. Mech Dev 2019, 156, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng S, Xia IF, Wanner R, Abello J, Stratment AN, Nicoli S. Hemodynamics regulate spatiotemporal artery muscularization in the developing circle of Willis. eLife 2024, 13, RP94094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palumbo R, Gaetano C, Antonini A, Pompilio G, Bracco E, Rönnstrand L, Heldin CH, Capogrossi MC. Different effects of high and low shear stress on platelet-derived growth factor isoform release by endothelial cells: consequences for smooth muscle cell migration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002, 22, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardik A, Yamashita A, Aziz F, Asada H, Sumpio BE. Shear stress-stimulated endothelial cells induce smooth muscle cell chemotaxis via platelet-derived growth factor-BB and interleukin-1alpha. J Vasc Surg 2005, 41, 321–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zerwes HG, Risau W. Polarized secretion of a platelet-derived growth factor-like chemotactic factor by endothelial cells in vitro. J Cell Biol 1987, 105, 2037–2041. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellström M, Kalén M, Lindahl P, Abramsson A, Betsholtz C. Role of PDGF-B and PDGFR-beta in recruitment of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes during embryonic blood vessel formation in the mouse. Development 1999, 126, 3047–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratman AN, Pezoa SA, Farrelly OM, Castranova D, Dye LE, Butler MG, Sidik H, Talbot WS, Weinstein BM. Interactions between mural cells and endothelial cells stabilize the developing zebrafish dorsal aorta. Development 2017, 144, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leonard EV, Figueroa RJ, Bussmann J, Lawson ND, Amigo JD, Siekmann AF. Regenerating vascular mural cells in zebrafish fin blood vessels are not derived from pre-existing mural cells and differentially require Pdgfrβ signaling for their development. Development 2022, 149, dev199640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siekmann, AF. Biology of vascular mural cells. Development 2023, 150, dev200271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee J, Goeckel ME, Levitas A, Colijn S, Shin J, Hindes A, Mun G, Burton Z, Chintalapati B, Yin Y, Abello J, Solnica-Krezel L, Stratman A. CXCR3-CXCL11 signaling restricts angiogenesis and promotes pericyte recruitment. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grazioli A, Alves CS, Konstantopoilos K, Yang JT. Defective blood vessel development and pericyte/pvSMC distribution in alpha 4 integrin-deficient mouse embryos. Dev Biol 2006, 293, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando K, Fukuhara S, Izumi N, Nakajima H, Fukui H, Kelsh RN, Mochizuki N. Clarification of mural cell coverage of vascular endothelial cells by live imaging of zebrafish. Development 2016, 143, 1328. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padget RL, Mohite SS, Hoog TG, Justis BS, Green BE, Udan RS. Hemodynamic force is required for vascular smooth muscle cell recruitment to blood vessels during mouse embryonic development. Mech Dev 2019, 156, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinha S, Iyer S, Granata A. Embryonic origins of human vascular smooth muscle cells: implications for in vitro modeling and clinical application. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014, 71, 2271–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander BE, Zhao H, Astrof S. SMAD4, a critical regulator of cardiac neural crest fate and vascular smooth muscle development. Dev Dyn 2024, 253, 119–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yokoyama U, Ichikawa Y, Minamisawa S, Ishikawa Y. Pathology and molecular mechanisms of coarctation of the aorta and its association with the ductus arteriosus. J Physiol Sci 2017, 67, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinning C, Zengin E, Kozlik-Feldman R, Blakenberg S, Rickers C, von Kodolitsch Y, Girdauskas E. Bicuspid aortic valve and aortic coarctation in congenital heart disease. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther 2018, 8, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).